Benchmarking Jordan’s Trade Role: A Comparative Analysis of Logistics Infrastructure, Geopolitical Position, and Regional Integration

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Trade Infrastructure and Logistics Performance

2.2. Trade Facilitation and Institutional Processes

2.3. Port Governance and Performance

2.4. Review of Geopolitical Stability and Institutional Factors

2.5. Regional Trade Integration and Network Connectivity

2.6. Theoretical and Analytical Frameworks

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Data Sources

3.3. Analytical Framework

3.3.1. Comparative Descriptive Analysis

3.3.2. Benchmarking and Composite Index Construction

- Trade Facilitation Capabilities (Trade-F):

- Port Competitiveness & Governance (Port-C):

- 4.

- Geopolitical Stability & Institutional Resilience (Geo-Stab):

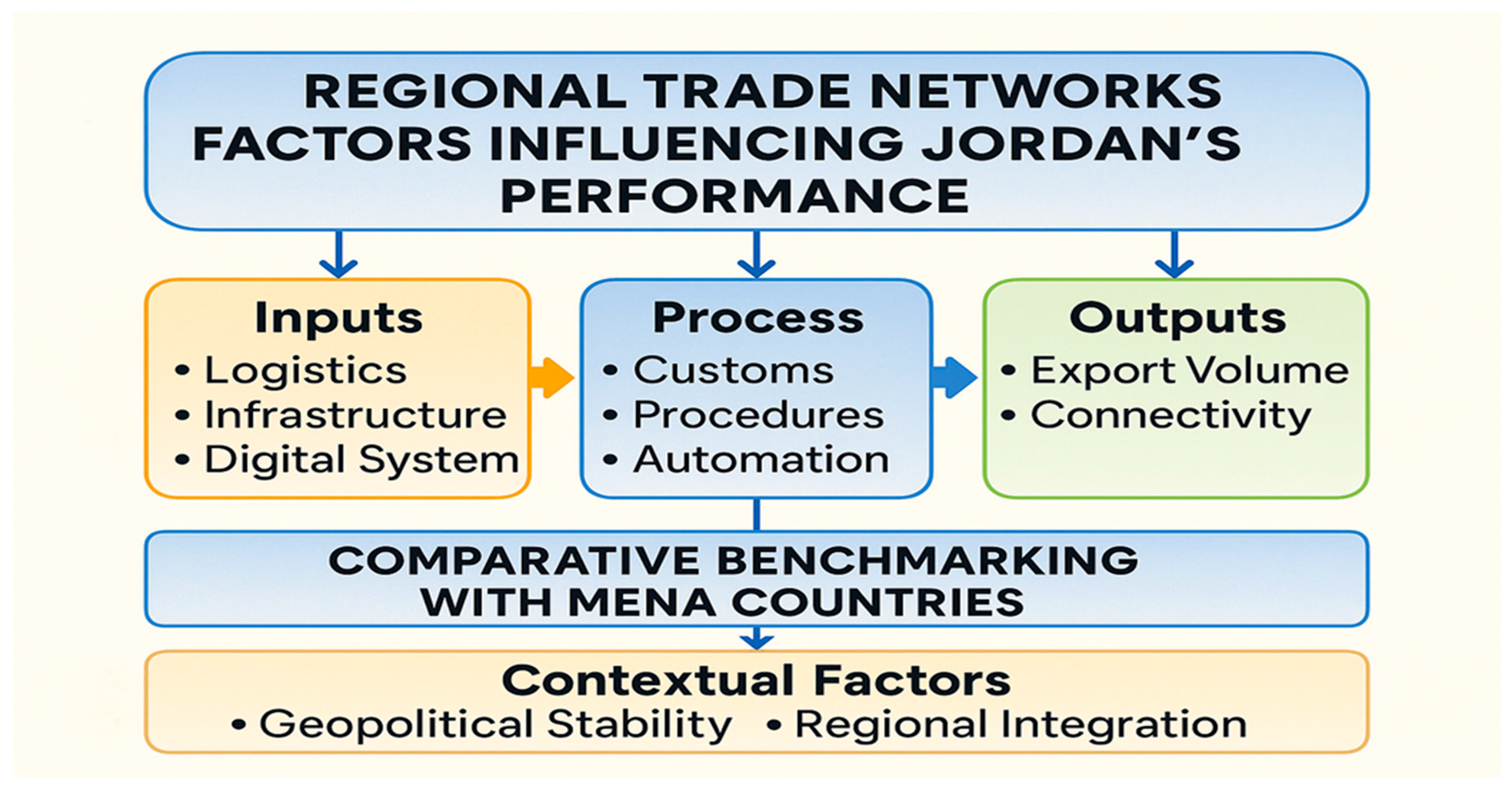

3.3.3. IPO Framework Application

- Inputs: Infrastructure capacity, port systems, Trade-F mechanisms.

- Processes: Customs procedures, Digital-TA levels, inter-agency cooperation.

- Outputs: Export volumes, trade diversification, and regional connectivity.

3.4. Interpretation Strategy

- Translating technical data: SWOT helps convert quantitative benchmarking results into policy-relevant insights, making it accessible to policymakers, practitioners, and development agencies (Das Neves Marques et al., 2022; Mazur, 2023).

- Complementing the IPO framework, which models the instrumental dynamics of systems, while SWOT sorts outcomes into eponymous “strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats,” offering a cohesive grasp of the strategic position of Jordan (Bilgin, 2023; Hausmann et al., 2020; Liu, 2024).

4. Results

4.1. Logistics Infrastructure Performance

- The UAE leads, with a composite score of 0.95, demonstrating exceptional performance in customs, infrastructure, and shipment reliability.

- Saudi Arabia ranks second, with 0.85, driven by sustained investment in transport and logistics under Vision 2030.

- Jordan scores 0.65, reflecting moderate performance. Key weaknesses are observed in timeliness and tracking and tracing, suggesting areas for system upgrades and technology deployment.

- Egypt and Lebanon follow with 0.75 and 0.55, respectively, the latter hindered by severe political and financial crises.

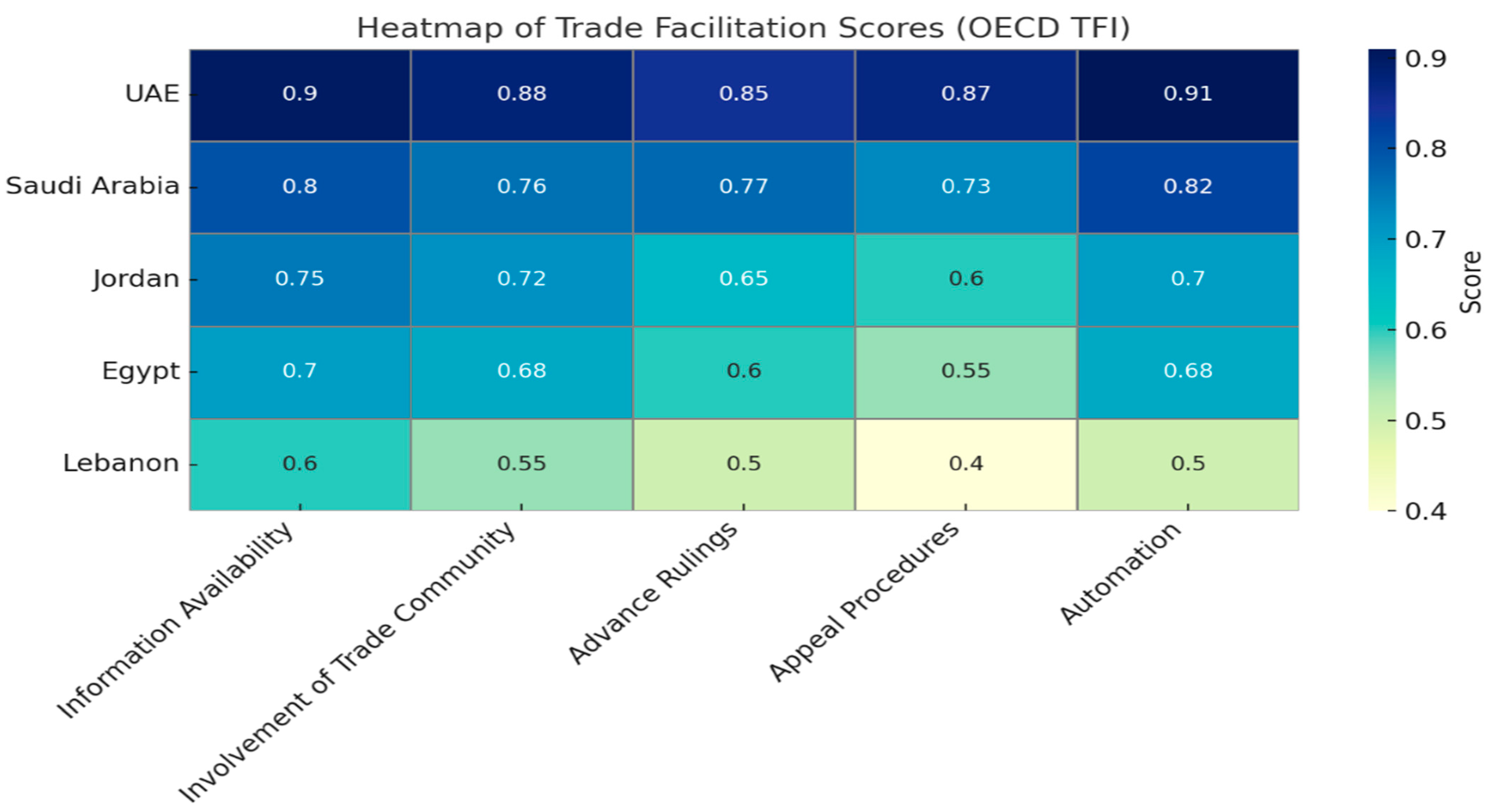

4.2. Trade Facilitation Capabilities

- The UAE again leads with 0.90, attributed to its seamless digital customs platforms and business-friendly trade policies.

- Jordan achieves 0.70, ranking third. While it performs well in information availability and border cooperation, it is significantly behind in appeal procedures and advance rulings.

- Saudi Arabia ranks similarly at 0.75, while Egypt and Lebanon lag due to low automation and lack of institutional clarity.

4.3. Port Competitiveness and Governance

- The UAE and Saudi Arabia achieve high scores (0.90 and 0.80, respectively), with successful public–private governance models and advanced port management systems.

- Jordan scores 0.65, reflecting a public governance model and limited Digital-TA (score of 0.4). Operational efficiency at Aqaba port remains moderate but below regional expectations.

- Egypt and Lebanon score 0.60 and 0.50, respectively.

4.4. Geopolitical Stability and Institutional Resilience

- The UAE again leads with 0.92, reflecting strong institutions and internal cohesion.

- Jordan ranks second after the UAE, scoring 0.80, underscoring its relative stability amid a volatile region. This stability is a strategic asset for trade and investment.

- Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Lebanon score 0.70, 0.55, and 0.40, respectively, with Lebanon exhibiting high fragility and political gridlock.

4.5. Composite Benchmarking Summary

4.6. Trade Volume and Export Structure

5. Discussion

5.1. IPO Framework Analysis

5.1.1. Inputs: Infrastructure, Systems, and Stability

5.1.2. Processes: Trade-F and Port Governance

5.1.3. Outputs: Trade Competitiveness and Network Connectivity

5.2. SWOT Analysis of Jordan’s Trade Position

5.3. Triangulation of Data, the Literature, and Performance

5.4. Policy Contributions

5.5. Policy Recommendations

5.6. Limitations and Future Directions

5.7. Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASEZA | Aqaba Special Economic Zone |

| Digital-TA | Digital technology adoption |

| FFP-FSI | Fund for Peace Fragile States Index |

| GAFTA | Greater Arab Free Trade Area |

| Geo-Stab | Geopolitical stability |

| IEP-GPI | Institute for Economics & Peace Global Peace Index |

| IMEC | India–Middle East–Europe Economic Corridor |

| Log-Inf | Logistics infrastructure |

| M-IPO | Modified Input–Process–Output Framework |

| NTFC | National Trade Facilitation Committee |

| OECD-TFIs | OECD Trade Facilitation Indicators |

| Port-C | Port competitiveness |

| SWOT | Strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats |

| Trade-F | Trade facilitation |

| UN Comtrade | UN Commodity Trade Statistics Database |

| UN Comtrade-TVR | UN Comtrade Trade Volume Records, 2022–2023 |

| UNCTAD-PPS | UN Conference on Trade and Development Port Performance Scorecard |

| World Bank-LPI | World Bank Logistics Performance Index |

Appendix A. Raw Indicator Values (Unscaled)

| Indicator (Year) | Jordan | UAE | Saudi Arabia | Egypt | Lebanon |

| LPI—Customs (2023) | 0.65 | 0.92 | 0.84 | 0.72 | 0.52 |

| LPI—Infrastructure (2023) | 0.68 | 0.94 | 0.83 | 0.74 | 0.55 |

| LPI—Tracking & Tracing (2023) | 0.63 | 0.95 | 0.85 | 0.71 | 0.53 |

| OECD-TFI—Automation (2025) | 0.70 | 0.91 | 0.82 | 0.68 | 0.50 |

| OECD-TFI—Appeal Procedures (2025) | 0.60 | 0.87 | 0.73 | 0.55 | 0.40 |

| UNCTAD PPS—Efficiency (2020–21) | 0.65 | 0.95 | 0.85 | 0.75 | 0.60 |

| UNCTAD PPS—Digital-TA (2020–21) | 0.40 | 0.90 | 0.70 | 0.60 | 0.45 |

| GPI (2024, lower = better) | 2.2 | 1.5 | 1.9 | 2.5 | 3.1 |

| FSI (2023, lower = better) | 70.1 | 35.2 | 55.3 | 82.7 | 95.8 |

| Note: Raw values as reported by World Bank (LPI), OECD (TFIs), UNCTAD (PPS), IEP (GPI), and FFP (FSI). | |||||

Appendix B. Winsorized and Normalized Values (0–1 Scale)

| Indicator | Jordan (Raw → Norm) | UAE (Raw → Norm) | Saudi (Raw → Norm) | Egypt (Raw → Norm) | Lebanon (Raw → Norm) |

| LPI—Customs | 0.65 → 0.65 | 0.92 → 0.95 | 0.84 → 0.84 | 0.72 → 0.72 | 0.52 → 0.52 |

| LPI—Infrastructure | 0.68 → 0.68 | 0.94 → 0.94 | 0.83 → 0.83 | 0.74 → 0.74 | 0.55 → 0.55 |

| OECD-TFI—Automation | 0.70 → 0.70 | 0.91 → 0.91 | 0.82 → 0.82 | 0.68 → 0.68 | 0.50 → 0.50 |

| UNCTAD PPS—Digital-TA | 0.40 → 0.40 | 0.90 → 0.90 | 0.70 → 0.70 | 0.60 → 0.60 | 0.45 → 0.45 |

| GPI (Inverse) | 2.2 → 0.85 | 1.5 → 0.98 | 1.9 → 0.90 | 2.5 → 0.80 | 3.1 → 0.60 |

| FSI (Inverse) | 70.1 → 0.65 | 35.2 → 0.95 | 55.3 → 0.78 | 82.7 → 0.55 | 95.8 → 0.40 |

| Note: Winsorized at the 1st/99th percentiles before normalization. Min–max normalization applied; inverse normalization for GPI and FSI. | |||||

Appendix C. Weighting Sensitivity Analysis

| Country | Equal Weights (Main) | PCA Weights | Entropy Weights |

| UAE | 0.92 (Rank 1) | 0.91 (Rank 1) | 0.93 (Rank 1) |

| Saudi Arabia | 0.78 (Rank 2) | 0.77 (Rank 2) | 0.79 (Rank 2) |

| Jordan | 0.70 (Rank 3) | 0.71 (Rank 3) | 0.69 (Rank 3) |

| Egypt | 0.65 (Rank 4) | 0.64 (Rank 4) | 0.66 (Rank 4) |

| Lebanon | 0.49 (Rank 5) | 0.48 (Rank 5) | 0.50 (Rank 5) |

| Note: Sensitivity analysis comparing equal weights, PCA-derived weights, entropy weights, and an additional robustness test excluding governance from the Port-C index. Rank ordering remains consistent across all methods, with Jordan’s Port-C score increasing slightly (+0.02) when governance is excluded, but overall benchmarking outcomes unchanged. | |||

References

- Alamoush, A. (2016). Challenges facing Aqaba port development. Middle East Transport Review, 5(3), 61–78. [Google Scholar]

- Aldweik, R., & Ghnaim, O. (2024). Jordan-centric cross-border tourism projects with Egypt and Saudi Arabia: An innovative regional tourism vision. International Journal of Economics, Business and Management Research, 8(8), 53–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Masri, K. (2021). Infrastructure gaps and trade connectivity in Jordan. World Infrastructure Reports, 14(2), 78–95. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, C., & Stevens, B. (2020). Digitalizing trade facilitation implementation: Opportunities and challenges for the Commonwealth. The Commonwealth, 160, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad-Warrad, T., & Al Tarawneh, M. A. (2020). The impact of Jordan free trade agreements on trade flows. International Journal of Business and Economics Research, 9(4), 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmeh, S. (2015). Transient global value chains and preferential trade agreements: Rules of origin in US trade agreements with Jordan and Egypt. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 8(3), 475–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y., & Wang, S. (Eds.). (2021). Trade and investment facilitation. In Spirit of the silk road: Chinese trade and investment throughout the Eurasian Corridor (pp. 103–144). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin, A., & Swoboda, M. (2023). Automated port operations: The future of port governance. In T. M. Johansson, D. Dalaklis, J. E. Fernández, A. Pastra, & M. Lennan (Eds.), Smart ports and robotic systems: Navigating the waves of techno-regulation and governance (pp. 149–165). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensassi, S., Márquez-Ramos, L., Martínez-Zarzoso, I., & Suárez-Burguet, C. (2014). Relationship between logistics infrastructure and trade: Evidence from Spanish regional exports. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 72, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, A., Shah, H., & Shetty, K. (2023). Impact of logistics performance index on international trade. International Research Journal of Modernization in Engineering Technology and Science, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgin, C. (2023). The concept of logistics performance in international trade framework: An empirical evaluation of logistics performance index. In Research anthology on macroeconomics and the achievement of global stability (pp. 345–369). IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldeirinha, V. R., Felício, J. A., Da Cunha, S. F., & Luz, L. M. D. (2018). The nexus between port governance and performance. Maritime Policy & Management, 45(7), 877–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das Neves Marques, B., Silva, M. S., Cutrim, S. S., Souza, A. L. R. D., Marques, E. F., & Araújo, M. L. V. (2022). Innovation management and port governance. International Journal for Innovation Education and Research, 10(1), 261–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieter, H. (2013). The drawbacks of preferential trade agreements in Asia. Economics, 7(1), 20130024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fund for Peace. (2023, June 14). Fragile states index 2023 annual report. FFP. Available online: https://fragilestatesindex.org/2023/06/14/fragile-states-index-2023-annual-report/ (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hamed, M. (2019). Customs reform and logistics performance in the Levant. Logistics and Development Journal, 11(1), 93–108. [Google Scholar]

- Hausmann, R., Espinoza, L., & Santos, M. (2020). The atlas of economic complexity: Mapping paths to prosperity (2nd ed.). Harvard Center for International Development. [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Economics & Peace (IEP). (2024). Global peace index 2024. IEP. Available online: https://www.economicsandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/GPI-2024-web.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Jafari, Y., Engemann, H., & Zimmermann, A. (2023). Food trade and regional trade agreements—A network perspective. Food Policy, 119, 102516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M., Mazur, R., & Al-Fayez, L. (2024). The India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor: Strategic opportunities for Jordan. International Trade Gateway Journal, 6(1), 24–39. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, R. (2020). South Asia: Multilateral trade agreements and untapped regional trade integration. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 26(2), 2891–2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, R., & Liu, Z. (2020). Port infrastructure connectivity, logistics performance and seaborne trade on economic growth: An empirical analysis on “21st-Century Maritime Silk Road”. Journal of Coastal Research, 106(sp1), 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. (2024). The role of logistics and infrastructure in promoting international trade. Journal of Education and Educational Research, 9(3), 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, S. A., & Ahmed, Y. Y. (2019). Saudi Arabia and UAE in the horn of Africa. Contemporary Arab Affairs, 12(3), 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí, L., & Puertas, R. (2017). The impact of logistics performance on international trade flows. Journal of Transport Economics and Policy, 51(2), 121–138. [Google Scholar]

- Mazur, R. (2023). Stability in motion: Jordan’s institutional resilience and economic transformation. Arab Governance Journal, 12(1), 18–35. [Google Scholar]

- Mdanat, M. F., Al Hur, M., Bwaliez, O. M., Samawi, G. A., & Khasawneh, R. (2024). Drivers of port competitiveness among low-, upper-, and high-income countries. Sustainability, 16(24), 11198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moïsé, E., Orliac, T., & Minor, P. (2011). Trade facilitation indicators: The impact on trade costs (OECD Trade Policy Working Papers No. 118). OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munim, Z. H., & Schramm, H.-J. (2018). The impacts of port infrastructure and logistics performance on economic growth: The mediating role of seaborne trade. Journal of Shipping and Trade, 3(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochieng, C. S., & Musyoka, P. (2017). Enhancing Africa–India regional trade agreements: Issues and policy recommendations. In G. Odularu, & B. Adekunle (Eds.), Negotiating south-south regional trade agreements: Economic opportunities and policy directions for Africa (pp. 49–60). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2025). Trade facilitation indicators 2025. OECD. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/trade-facilitation-indicators_5k4bw6kg6ws2-en.html (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Özgüner, Z., & Köse, Z. (2025). Relationship between logistics performance, trade volume and economic growth. Iğdır Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, 38, 230–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, G. D., Magafas, L., Demertzis, K., & Antoniou, I. (2023). Analyzing global geopolitical stability in terms of world trade network analysis. Information, 14(8), 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raihan, A., Hasnat, M. A., Rahman, S. M., Ridwan, M., Rahman, M. M., Islam, M. T., Sarker, T., Dhar, B. K., & Bari, A. B. M. M. (2025). Recent advancements in alternative energies, technological innovations, and optimization strategies for seaport decarbonization. Innovation and Green Development, 4(3), 100252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segnana, G., Oweini, M., & Al-Khatib, A. (2024). Refugee inflows and infrastructure strain in Jordanian municipalities. Journal of Migration and Urban Policy, 8(1), 55–72. [Google Scholar]

- Sorescu, S., & Bollig, C. (2022). Trade facilitation reforms worldwide: State of play in 2022 (OECD Trade Policy Papers, No. 263). OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M., Li, J., & Kim, W. (2025). Port ship congestion and port-oriented cities air pollution: The role of machine learning models in transportation environmental governance. Transport Policy, 155, 103972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z., Park, K. S., Liu, Z., & Su, M. (2025). Key factors for non-polar use of the Northern Sea Route: A Korean point of view. Journal of Transport Geography, 124, 104183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsourapas, G. (2019). The politics of forced migration in Jordan: Between pressure and resilience. Refugee Studies Quarterly, 35(2), 123–140. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. (2023). Trade volume records, 2022–2023. UN Comtrade Database. Available online: https://data.un.org/data.aspx?d=ComTrade&f=_l1Code%3a1#ComTrade (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). (2021a). National trade facilitation committees as coordinators of trade facilitation reforms (PDF ed.). Transport and Trade Facilitation Series No. 14. United Nations. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). (2021b). Port performance scorecard 2020–2021. UNCTAD. Available online: https://tft.unctad.org/thematic-areas/port-management/port-performance-scorecard/ (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Verhoeven, P., & Vanoutrive, T. (2012). A quantitative analysis of European port governance. Maritime Economics & Logistics, 14(2), 178–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Li, X., & Su, M. (2025). Critical success factors for implementing digital human resources: Insights from the shipping sector. Ocean & Coastal Management 269, 107847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2023a). Connecting to compete 2023: Trade logistics in the global economy (7th ed.). Available online: http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099042123145531599/pdf/P17146804a6a570ac0a4f80895e320dda1e.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- World Bank. (2023b). Logistics performance index. Available online: https://lpi.worldbank.org/international/global (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Xu, L., & Chen, Y. (2025). Overview of sustainable maritime transport optimization and operations. Sustainability, 17(14), 6460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilli, J. C., & Freire, P. D. S. (2023). Conceptual models of port governance. Contribuciones a las Ciencias Sociales, 16(9), 17400–17420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name | Description | Reference | Conventional Citation | Citation Code |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “Fund for Peace Fragile States Index” | Measures political stability and institutional resilience. | Fund for Peace. (2023). Fragile States Index 2023: Annual report | Fund for Peace (2023) | FFP-FSI (2023) |

| “Institute for Economics & Peace Global Peace Index” | Measures political stability and institutional resilience | Institute for Economics & Peace. (2024). Global Peace Index 2024: Measuring peace in a complex world. https://www.economicsandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/GPI-2024-web.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2025) | Institute for Economics & Peace (IEP) (2024) | IEP-GPI (2024) |

| “OECD Trade Facilitation Indicators” | Measures automation, border cooperation, and procedural transparency. | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2025). Trade-F indicators. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/trade-facilitation-indicators_5k4bw6kg6ws2-en.html (accessed on 15 March 2025) | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2025) | OECD-TFIs (2025) |

| “UN Comtrade Trade Volume Records, 2022–2023” | Provides data on export-import volumes and trade partners | United Nations Comtrade. (2023). Trade volume records, 2022–2023. https://comtrade.un.org/ (accessed on 15 March 2025) | United Nations (2023) | UN Comtrade-TVR (2023) |

| “UN Conference on Trade and Development Port Performance Scorecard” | Assesses port governance, operational efficiency, and Digital-TA. | United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. (2021). Port Performance Scorecard Newsletter (2020–2021). https://tft.unctad.org/thematic-areas/port-management/port-performance-scorecard/ (accessed on 15 March 2025) | United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) (2021b) | UNCTAD-PPS (2021b) |

| “World Bank Logistics Performance Index” | Evaluates dimensions such as customs, infrastructure, shipment tracking, and timeliness. | World Bank. (2023b). Logistics Performance Index. https://lpi.worldbank.org/international/global (accessed on 15 March 2025) | World Bank (2023b) | World Bank-LPI (2023) |

| Country | Customs | Infrastructure | International Shipments | Logistics Quality | Tracking & Tracing | Timeliness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UAE | 0.92 | 0.94 | 0.96 | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.97 |

| Saudi Arabia | 0.84 | 0.83 | 0.86 | 0.82 | 0.85 | 0.88 |

| Jordan | 0.65 | 0.68 | 0.66 | 0.64 | 0.63 | 0.67 |

| Egypt | 0.72 | 0.74 | 0.76 | 0.70 | 0.71 | 0.75 |

| Lebanon | 0.52 | 0.55 | 0.50 | 0.54 | 0.53 | 0.51 |

| Country | Information Availability | Involvement of Trade Community | Advance Rulings | Appeal Procedures | Automation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UAE | 0.9 | 0.88 | 0.85 | 0.87 | 0.91 |

| Saudi Arabia | 0.8 | 0.76 | 0.77 | 0.73 | 0.82 |

| Jordan | 0.75 | 0.72 | 0.65 | 0.6 | 0.7 |

| Egypt | 0.7 | 0.68 | 0.6 | 0.55 | 0.68 |

| Lebanon | 0.6 | 0.55 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| Country | Governance Type | Operational Efficiency | Digital-TA Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| UAE | Public–Private | 0.95 | 0.9 |

| Saudi Arabia | Public | 0.85 | 0.7 |

| Jordan | Public | 0.65 | 0.4 |

| Egypt | Public | 0.75 | 0.6 |

| Lebanon | Public | 0.6 | 0.45 |

| Country | Log-Inf | Trade-F | Port-C | Geo-Stab |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UAE | 0.95 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.92 |

| Saudi Arabia | 0.85 | 0.75 | 0.8 | 0.7 |

| Jordan | 0.65 | 0.7 | 0.65 | 0.8 |

| Egypt | 0.75 | 0.68 | 0.6 | 0.55 |

| Lebanon | 0.55 | 0.51 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| Export Destination | Export Volume (USD Millions) | Major Export Sectors |

|---|---|---|

| Iraq | 950 | Pharmaceuticals |

| Saudi Arabia | 850 | Fertilizers |

| UAE | 780 | Chemicals |

| Egypt | 610 | Food Products |

| Qatar | 470 | Machinery |

| Turkey | 400 | Textiles |

| USA | 350 | ICT Equipment |

| Dimension | Indicator Source | Jordan’s Score | Regional Comparison | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geo-Stab | FFP-FSI (2023), IEP-GPI (2024) | High stability | Higher than Egypt, Lebanon | Strategic strength |

| Trade-F | OECD-TFIs (2025) | Moderate (av. 0.70) | Lower in automation, appeals | Needs reform |

| Export market diversity | UN Comtrade-TVR (2023) | Top 5 markets >70% | High dependence on Iraq, Gulf states | Risk of overfocus |

| Trade network integration | UN Comtrade-TVR (2023), Network Diagram | Moderate density | Limited to regional partners | Expand needed |

| Port governance & operations | UNCTAD-PPS (2021) | Public; 0.65 efficiency | Less efficient, lower Digital-TA | Reform opportunity |

| Log-Inf | World Bank-LPI (2023) | 0.65 | Lower than UAE (0.94), KSA (0.83) | Needs improvement |

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

| - High Geo-Stab (IEP-GPI, 2024) (0.80) | - Weak Digital-TA in ports and trade systems (OECD-TFIs, 2025) (0.4) |

| Strategic location linking Asia–Europe–Africa | Moderate Log-Inf (World Bank-LPI, 2023) (0.65) |

| Institutional predictability and favorable perception by investors | Narrow export base and market concentration (UN Comtrade-TVR, 2023) |

| Performance parity with larger economies like Egypt in some indicators | Limited port governance flexibility and public-sector control (UNCTAD-PPS, 2021) |

| Opportunities | Threats |

| Leverage IMEC and GAFTA platforms for corridor integration | Regional instability affecting land and maritime routes |

| Digitize customs and port procedures to close gap with UAE/Saudi Arabia | Economic exposure to global commodity shocks |

| Attract regional logistics investment using stability as anchor | Domestic fiscal constraints may slow infrastructure modernization |

| Expand trade partnerships beyond traditional partners | Talent shortages in logistics and Trade-F sectors |

| Policy Area | Rationale | Recommended Actions | Regional Benchmark/Support |

|---|---|---|---|

| Digital customs & ports | Low Digital-TA score (0.4) limits efficiency and transparency. | Deploy paperless customs, port community systems, and cross-agency digital integration. | UAE’s Dubai Trade, Saudi Fasah platform |

| Port governance reform | Centralized model at Aqaba restricts performance and innovation. | Delegate autonomy, incentivize PPPs, and introduce performance-linked accountability. | UNCTAD Port Governance Toolkit |

| Log-Inf investment | Jordan’s score (0.65) reflects underinvestment in corridors and inland hubs. | Prioritize investment in border zone logistics, inland dry ports, and multimodal corridors (e.g., Al-Omari, Karameh). | Leverage financing from EBRD, USAID, World Bank |

| Institutional facilitation framework | Persistent gaps in appeal mechanisms and legal clarity hinder Trade-F. | Establish a legally empowered NTFC; embed transparency and automation in trade laws. | OECD-TFI, WTO TFA implementation frameworks |

| Export & market diversification | High dependency on limited markets and weak presence in value-added sectors. | Support ICT, pharma, agri-tech exports; negotiate digital trade corridors and regional agreements (GAFTA, IMEC). | Jordan’s political stability as a regional logistics asset |

| Human capital development | Future reforms require specialized talent in trade, logistics, and digital systems. | Launch national capacity-building initiatives with universities and logistics academies. | Aim to position Jordan as a logistics training hub in the Levant |

| Area of Extension | Description | Data Source | Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regression analysis | Quantify how World Bank-LPI, Digital-TA, and stability affect exports | UN Comtrade-TVR (2023), World Bank-LPI (2023) | OLS or panel regression |

| Time-series trend analysis | Track Jordan’s performance over time on key trade indicators | OECD-TFIs (2025), UN Comtrade-TVR (2023), World Bank-LPI (2023) | Line charts, growth trends |

| Diversification metrics | Assess concentration vs. diversity in trade partners and products | UN Comtrade-TVR (2023), Department of Statistics | Herfindahl Index, network maps |

| Policy impact evaluation | Analyze impacts of port or customs reforms post-implementation | Ministry of Transport, ASEZA, Customs Department | Difference-in-differences |

| Stakeholder interviews | Collect qualitative data from logistics operators, port staff, exporters | Field interviews, surveys | Thematic coding |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Samawi, G.A.; Bwaliez, O.M.; Mdanat, M.F. Benchmarking Jordan’s Trade Role: A Comparative Analysis of Logistics Infrastructure, Geopolitical Position, and Regional Integration. Economies 2025, 13, 282. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13100282

Samawi GA, Bwaliez OM, Mdanat MF. Benchmarking Jordan’s Trade Role: A Comparative Analysis of Logistics Infrastructure, Geopolitical Position, and Regional Integration. Economies. 2025; 13(10):282. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13100282

Chicago/Turabian StyleSamawi, Ghazi A., Omar M. Bwaliez, and Metri F. Mdanat. 2025. "Benchmarking Jordan’s Trade Role: A Comparative Analysis of Logistics Infrastructure, Geopolitical Position, and Regional Integration" Economies 13, no. 10: 282. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13100282

APA StyleSamawi, G. A., Bwaliez, O. M., & Mdanat, M. F. (2025). Benchmarking Jordan’s Trade Role: A Comparative Analysis of Logistics Infrastructure, Geopolitical Position, and Regional Integration. Economies, 13(10), 282. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13100282