Abstract

Women entrepreneurs in rural Ecuador face significant obstacles, including limited access to education, financial services, and business networks. Despite their vital role in the economy, gender inequalities hinder their success. This study protocol aims to evaluate the impact of a tailored business training program designed to empower rural women entrepreneurs and promote sustainable economic development. Aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of Quality Education (Goal 4), Gender Equality (Goal 5), and Decent Work and Economic Growth (Goal 8), the program will assess improvements in women’s agency, confidence, and business performance. Key results include a 54% increase in perceived self-efficacy and a 200% increase in locus of control observed in the pre-pilot phase, indicating enhanced decision-making capacities and program effectiveness. Expected improvements in business performance will be measured by sales figures and financial growth, with anticipated positive impacts on SDG 8. The program will also track participation rates, with high enrollment and completion rates contributing to SDG 4. Additionally, financial stability and the number of engaged suppliers will be monitored, supporting SDG 8. By incorporating additional structural interventions, the study will offer insights into enhancing the empowerment of rural women entrepreneurs, creating a holistic impact that fosters both individual and community development.

1. Introduction

Ecuador is one of the countries with the highest number of micro-, small-, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) globally (Adom et al. 2018). According to the Superintendence of Companies, Securities, and Insurance, MSMEs constitute 95% of Ecuador’s business sector (Arráiz 2018), generating approximately 46% of the country’s formal employment between 2013 and 2017. This underscores their crucial role in sustainable economic growth, aligning with SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth). However, a significant challenge persists: an alarming failure rate of eight out of ten enterprises within their first three years (Adom et al. 2018). This highlights the urgent need for comprehensive support mechanisms, including professional guidance, training, access to financing, and technological resources (Baessler and Schwarzer 1996; Asian Development Bank Institute 2021).

Among the diverse entrepreneurial landscape, women in underdeveloped countries, including Ecuador, emerge as a vital force, often driven by necessity and contributing substantially to their families and communities (Banco Central del Ecuador 2023). Despite their critical role, gender disparities continue to exacerbate the challenges women face compared to their male counterparts globally (Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo 2021). Research indicates that working women invest 90% of their salary back into their families and communities, in contrast to 35% for men (Banco Central del Ecuador 2023). However, gender inequality means that women’s business performances are often more constrained than those of men worldwide.

The promotion of gender equality and women’s empowerment is essential for socioeconomic progress, contributing to SDGs 1 (No Poverty), 5 (Gender Equality), and 10 (Reducing Inequalities). Empowering women involves enhancing their authority and influence across various life domains, including agriculture. Women’s involvement in agriculture, which comprises half of the agricultural workforce, has significant implications for land use, crop productivity, household income, and resource management. Their participation helps in adapting to climate change and improving economic returns by mitigating climate impacts (Bandura 1995; Bandura 1977; Bandura 2006; Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo 2021).

This study focuses on evaluating the impact of entrepreneurship training on women in rural Ecuador, aiming to address gender inequality and support sustainable development. Our research question is as follows: How does a tailored business training program affect the agency, confidence, and business performance of rural women entrepreneurs in Ecuador?

The objective of this study is to assess the effectiveness of a tailored business training program in enhancing women’s entrepreneurial skills, promoting gender equality (SDG 5) and fostering economic growth (SDG 8). The study will compare outcomes between trained women entrepreneurs and a control group that will not receive any intervention. The control group will provide initial and final data to observe its natural performance and progress without any support, which will help isolate the specific effects of the training program on the trained group.

The paper is structured as follows: First, we provide a concise review of the theoretical background shaping our research. Next, we outline our methodology and incorporate findings from a pre-pilot study to support the large-scale protocol. Following this, we present the expected results, offering an interpretation relevant to our research questions. Finally, we conclude by providing practical recommendations based on our analysis. This framework aims to effectively evaluate and support the entrepreneurial landscape for women in Ecuador.

2. Theoretical Background

The literature has identified, based on studies conducted and field experience (Asian Development Bank Institute 2021; Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo 2021), that education and training in support of women entrepreneurs is a priority when it comes to promoting the economic and social development of a country, aligning with SDG 4 (Quality Education). Primarily, rural women, as one of the groups that suffer disproportionately from poverty, require support (Bandura 1995; Beattie et al. 2011).

One prominent theory relevant to women entrepreneurship is Social Feminist Theory, which posits that gender differences in entrepreneurial behavior stem from societal structures and norms rather than inherent traits. This theory highlights the impact of socialization and cultural expectations on women’s entrepreneurial activities and decisions (Bandura 2006). For example, women’s participation in agricultural activities significantly impacts responsible farm production, in line with SDG 2 (Zero Hunger) and SDG 13 (Climate Action). Farms where women are involved in farming are 33.5% more likely to be classified as highly responsible producers compared to those where only men are involved. Thus, women’s empowerment is indispensable for responsible and sustainable agricultural practices (Bandura 1977).

Self-Efficacy Theory, developed by Albert Bandura, underscores the importance of the belief in one’s ability to succeed. Self-efficacy positively influences entrepreneurial intentions, and improvements in female entrepreneurial intentions exceed those of men, supporting SDG 5 (Gender Equality) and SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) (Bandura 2006).

Human Capital Theory is also vital, emphasizing the role of education and training in enhancing individuals’ skills and knowledge, thereby improving their economic outcomes. Entrepreneurship education (EE) is crucial in this regard, as it significantly influences women’s entrepreneurial intentions by increasing their knowledge, skills, and confidence, thereby empowering them to become entrepreneurs (Blood and Wolfe 1960; Bandura 2006). Studies have shown that EE is more effective at improving women’s human capital than men’s, thereby increasing the likelihood that women will engage in entrepreneurial activities. Although men’s perception of the entrepreneurial environment may be more crucial, entrepreneurship education has a more pronounced effect on improving female self-efficacy, enabling women to overcome the barriers of low self-efficacy and increasing their likelihood of entrepreneurial participation and success (Blood and Wolfe 1960; Bandura 2006).

There are notable differences in the risk tolerance and behavioral control between genders. For example, without entrepreneurship education, male university students may show more entrepreneurial intentions than females due to their greater capacity for innovation and entrepreneurial control. However, after receiving entrepreneurship education, females improve their attitudes and risk-taking abilities, resulting in a more significant improvement in their entrepreneurial intentions compared to males (Bandura 2006). According to research conducted in the United Kingdom, the gender of entrepreneurs influences the goals of entrepreneurial ventures. Women tend to prioritize social and environmental enterprises over traditional projects. Similarly, female entrepreneurship often goes beyond economic value generation, emphasizing sustainability and social benefits to the community (Bors and Stokes 1998). Our specific area is women’s entrepreneurship in rural areas, which represents an even more challenging task. To a greater extent, they face the macho culture of the area. In addition, they must divide their time and resources between business and family functions. Other disadvantages are the limited access to basic services and telecommunications and the low quality of education and health services, which align with SDGs 3 (Good Health and Well-Being), 4 (Quality Education), and 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure) (Bandura 1995).

Empowerment is defined as the process by which women gain power and control over their own lives and decisions, increasing their capacity to act effectively in the economic, social, and political spheres. Education and training in entrepreneurship are crucial to women’s empowerment, as they improve women’s self-confidence and skills, enabling them to overcome barriers and actively participate in the economy (Bandura 1977).

2.1. Global and Regional Statistics

Globally, women account for approximately 37% of all entrepreneurship-related activities. Despite this, they face a higher rate of business failure due to their lack of access to finance and business networks, resulting in an unfavorable environment that limits the growth potential and sustainability of women-led businesses (Carvajal-Álava and Hidalgo-Molona 2019).

At the global level, the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report 2022 provides additional insight into the state of gender equity. The global gender gap has closed to 68.1%, which represents significant progress. However, the long-term projection indicates that it will take 132 years to completely close this gap. This statistic highlights the persistence of deep and structural inequalities that affect women in various spheres, mainly economic (Castillo 2020).

There is an alarming disparity in access to finance, which not only limits the growth of women-led businesses but also undervalues their innovative potential. In addition, women tend to receive smaller loans with less favorable terms than men, which further restricts their ability to scale their businesses (Chen et al. 2001).

In Latin America, the landscape of female entrepreneurship presents both advances and challenges, such as the large gender inequalities in entrepreneurship in the region. Women hold only 15% of management positions and own only 14% of companies. In addition, only one in ten companies has a woman as a senior manager. Factors that influence gender equity are the presence of women in leadership positions, the level of training of the workforce, the use of advanced technologies, and a favorable business culture. IDB President Mauricio Claver-Carone stresses the importance of investing in female leadership to foster sustainable economic and social growth in Latin America and the Caribbean (Cruz-Sandoval et al. 2023).

Women predominate in soft areas such as communication and public relations, while in hard areas, such as foreign trade, they represent less than 35% of employees. There is a higher proportion of women in low positions (36%) than in high positions (25%), and only 35% of the workforce using advanced technologies is composed of women (Cruz-Sandoval et al. 2023).

A UNESCO report reveals that, although the female literacy rate in Latin America is high (93%), inequalities persist in access to secondary and tertiary education, especially among rural women (UNESCO 2020). This educational gap limits development and economic empowerment opportunities for these women (Deci and Ryan 1985).

In Asia, women also face socioeconomic constraints that affect their participation in entrepreneurship. In countries such as India and Bangladesh, microcredit programs have been effective at increasing female participation in entrepreneurship by as much as 20% (Deng and Wang 2023).

These programs provide start-up capital and business training, enabling more women to start and manage their own businesses. However, in many parts of Asia, rural women still face significant barriers to accessing education. Initiatives in countries such as China and Vietnam, which have implemented vocational training programs for rural women, have proven successful at improving their skills and employment opportunities. These programs not only improve women’s ability to generate income, but they also contribute to poverty reduction and local economic development (Donald et al. 2017).

2.2. Ecuadorian Context

In Ecuador, a report on women in the Ecuadorian labor market by the INEC reveals that in December 2022, the adequate or full employment rate was 28.8% for women, compared to 41.1% for men. The underemployment rate for women was 17.9%, while for men it was 20.4%. Moreover, the median labor income for employed women was USD 300.5, considerably lower than the USD 400.7 for men. In addition, women worked an average of 31 h per week, compared to 37 h worked by men. These figures show significant differences in various aspects of employment between men and women in Ecuador (Earley et al. 1987).

According to the Banco Central del Ecuador, only 35% of rural women in Ecuador have access to formal financial services. This limited access to formal financing restricts their ability to invest in their businesses, which, in turn, affects their growth and sustainability. The availability of accessible and equitable financial services is crucial to foster female entrepreneurship and improve the economic conditions of rural women (Farnworth et al. 2024).

With respect to gender inequality in Ecuador, it is evident in multiple aspects of economic and social life. According to the World Economic Forum, Ecuador ranks 94th out of 153 countries in the Global Gender Gap Index 2022. This position reflects persistent disparities in terms of access to opportunities and resources between men and women. The urgent need to implement policies and programs that promote gender equality is clear, with the goal of creating a more inclusive and equitable environment for all women in Ecuador (Carvajal-Álava and Hidalgo-Molona 2019).

Despite global advances in gender equity and female entrepreneurship, women continue to face significant challenges, such as a lack of access to finance and business networks, which limit the growth and sustainability of their businesses. In the Ecuadorian context, these barriers are even more pronounced, evidenced by disparities in employment, access to financial services, and the persistent gender gap. Addressing these inequalities through inclusive policies and targeted support programs will not only boost the economic development of rural women but will also contribute to the sustainable and equitable growth of the region as a whole. To provide empirical support and better substantiate our study protocol, we conducted a pre-pilot study, which is explained in Section 3.2.

2.3. Hypothesis

Based on a previous analysis, our hypothesis is as follows: “Tailored business training for rural women entrepreneurs in Ecuador will positively impact their agency, confidence, and business performance”.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Setting

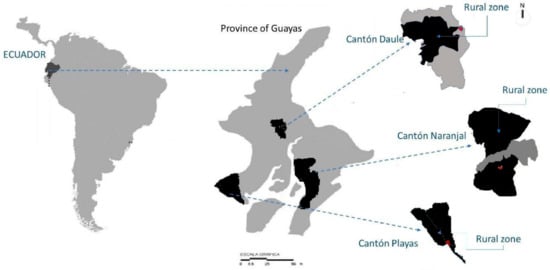

This study will be carried out in the province of Guayas-Ecuador, delimiting three strategically located cantons of the province (Daule, Naranjal, and Playas), with particular socioeconomic characteristics (Figure 1). Sectors of each canton are selected as focal points for a women’s entrepreneurship training and empowerment project, which are intrinsically linked to their geographic locations and economic activities. The choice of these sectors is not only strategic because of their geographic location and economic activities, but it also aligns with SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) by promoting entrepreneurial opportunities in various sectors, such as agriculture, fisheries, and trade.

Figure 1.

Locations of study sites.

The canton of Daule facilitates the crucial connection between the rural cantons and the capital of the province of Guayas, Santiago de Guayaquil. Its positioning corresponds to an expansion zone for the economic growth of the province. The Playas canton is especially important for being the last coastal area of the province of Guayas, with its diverse economic activities that include agriculture, fishing, livestock, commerce, and tourism. Finally, the canton of Naranjal presents an integral panorama for agricultural and tourism business development in the rural sector, offering promising opportunities for business growth.

According to a report by the National Institute of Statistics and Census (INEC), in the urban areas of the region, there are six activities that are notorious as a source of employment for women: wholesale and retail trade, school teaching, domestic activities, work in the manufacturing industry, and human health care. It is relevant that in rural areas, women are excluded from agro-productive activities and only dedicate themselves to housework, which is why a large percentage of women migrate to urban centers (Fertő and Bojnec 2024).

By conducting exploratory fieldwork on women’s entrepreneurial activities, we identified commercial and service sectors that favor the economy of working and entrepreneurial women in the rural areas of Daule, Playas, and Naranjal. Based on previous work (Burns et al. 2016; Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo 2021; Financial Institutions Group 2021) and considering the potential of the region and our experience in training professionals, businessmen, and entrepreneurs, we propose a participatory dual training program. This program aims to support women entrepreneurs and owners of microenterprises in the sectors of Daule, Playas, and Naranjal, helping them to generate employment and achieve sustainable success.

In 2022, the population of the canton of Daule was 222,446 inhabitants, of which 27% resided in rural areas. According to the INEC, 50.03% of the population is male and 49.97% is female. The distribution by sex in rural areas is 50.1% female and 49.9% male (Fertő and Bojnec 2024). Household representatives in the rural sector are 64.7% male and 35.3% female. Daule is known as the “rice capital of Ecuador” for its important rice production. It is part of the Guayaquil metropolitan area, and its economic, social, and commercial activities are closely linked to Guayaquil. Daule’s main activities include agricultural production, centered mainly on rice, and commerce.

In the Playas canton, the rural commune called Engabao is selected, with a population of 10,612 inhabitants. According to data published by the INEC, the gender distribution in the rural area is 50.2% female and 49.8% male. Household representatives in the rural sector are composed of 69.9% men and 30.1% women (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos Estadísticas Laborales 2023). The Engabao commune is located along the coastline, approximately 15 km from the cantonal capital of the Playas canton and 110 km from Guayaquil. The main economic activities of Engabao are fishing and tourism. This area is well known among surfers for its beautiful beach. Despite this, the community lacks infrastructure and training opportunities to take full advantage of its tourism potential (Financial Institutions Group 2021).

For its part, the population of the canton Naranjal in 2022 was 83,691 inhabitants, of which 53% resided in rural areas. According to the INEC, 50.1% of the population is male and 49.9% is female. The distribution by sex in rural areas is 48.9% female and 51.1% male. Household representatives in the rural sector are 69.4% men and 30.6% women (Fertő and Bojnec 2024). In Naranjal, the predominant activity is agriculture, with important crops, such as cocoa, tobacco, sugar cane, rice, coffee, bananas, and a variety of fruits. In addition to agriculture, other cantonal activities of economic importance are fishing, livestock, and commerce. Although tourism is gaining importance, its full potential has not yet been exploited in the region.

This research project, approved by Clinica Kennedy’s IRB (CK-CEISH-2022-006), complies with ethical standards, and informed consent will be obtained from all subjects (it was also obtained for the pre-pilot mentioned before).

3.2. Pre-Pilot Study

3.2.1. Pre-Pilot Study Participant Characteristics

In the pre-pilot phase of our research conducted during the last quarter of 2023, we engaged with a total of 16 participants, evenly divided with 8 individuals in the treatment group and another 8 in the control group. This balanced distribution allowed for an initial comparison of the intervention’s impact on the selected psychological and behavioral variables.

The women participating in the treatment group exhibit a range of educational backgrounds and business experiences (see Table 1 and Table 2). Moreover, there is variation in the time and personnel dedication to their businesses (see Table 3). For the control group, we selected women with similar characteristics to those in the treatment group to ensure comparability. The control group will remain without any intervention. By providing initial and final data, their natural performance and progress can be observed without assistance, allowing us to isolate the specific impact of the training program on the participants who receive it. Unlike other training programs, a nominal fee was charged for the training. This small investment appeared to foster a greater commitment among the participants, who showed a higher level of interest in completing the course.

Table 1.

Personal information.

Table 2.

Knowledge and practice.

Table 3.

Business performance.

3.2.2. Pre-Pilot Study Variables

In the pre-pilot phase, a small subset of variables was used out of the entire set planned for the full study. These variables included aspects of motivational autonomy, such as autonomous, controlling, and impersonal. Measures related to the Clarity of Objectives and various facets of locus of control—general, interpersonal, performance, and political—were also included. Additionally, perceived self-efficacy was assessed to gauge its baseline levels and initial responses to the intervention. These variables were selected to provide preliminary insights and guide the development of the full study.

3.2.3. Pre-Pilot Study Analysis

Due to data collection limitations, the analysis was confined to the computation of means for the selected variables. No further inferential statistical methods were applied at this stage. This approach provided an initial descriptive overview of the data and facilitated the identification of trends within the treatment and control groups.

3.2.4. Pre-Pilot Table Explanation and Calculations

Table 4 starts with “Treatment_t0” and “Treatment_t1”, showing the treatment group’s mean scores before and after the intervention. “Control_t0” indicates the control group’s mean scores at the beginning of the study, with no follow-up data collected. “Treatment_Change” captures the mean score difference for the treatment group from the start to the end of the study.

Table 4.

Results.

“Difference between Treatment and Control at t0” measures the initial score difference between the groups. “Treatment_Percentage_Change” quantifies the treatment group’s score evolution from t0 to t1 as a percentage. “Treatment_t1_vs_Control_t0” reflects the difference between the treatment group at t1 and the control group at t0, assuming the control group remained unchanged (as we had the limitation that we could not collect information for the control group at t1).

The “Percentage Change from Treatment t1 to Control t0” translates the above difference into a percentage. “E_Y_given_X1” and “E_Y_given_X0” represent the expected outcomes for the treatment group at t1 and the control group at t0, respectively. These are used to calculate the “Average Treatment Effect”, showing the net effect of the intervention. Lastly, “ATE_Percentage” gives the Average Treatment Effect as a percentage relative to the control group’s initial scores.

3.2.5. Pre-Pilot Results

For “Autonomous”, a modest improvement was observed, with the Average Treatment Effect (ATE) indicating an increase of 9.9%. The intervention seemed to have a slightly smaller positive effect on “Controlling”, with an ATE of 5.1%. The “Impersonal” category was the only one to exhibit a negative outcome, with a −20.8% change, suggesting the intervention may have led to a decrease in impersonal feelings. Significant increases were noted in “Locus of Control—General” and “Perceived Self-Efficacy”, with ATEs of 200.0% and 54.0%, respectively. These large gains highlight the treatment’s strong influence on enhancing participants’ general sense of control and self-efficacy. Conversely, “Locus of Control—Interpersonal” showed a negative effect, with a −25.0% ATE, indicating a decline in participants’ perceived interpersonal control post-treatment. Finally, “Locus of Control—Performance” and “Locus of Control—Political” both showed positive outcomes, with ATEs of 8.3% and 32.8%, respectively, suggesting that the treatment improved the participants’ perceived control over their performance and political influence.

3.2.6. Pre-Pilot Discussion

- The treatment demonstrated notable effectiveness in enhancing participants’ sense of autonomy and control, particularly evidenced by significant improvements in general locus of control and self-efficacy. The treatment group experienced substantial increases of 200% and 54%, respectively, in these areas. These findings suggest that the intervention successfully bolstered participants’ overall sense of control over their lives and their confidence in their abilities;

- Moreover, the intervention positively impacted participants’ perceived control over their performance and political realms, with Average Treatment Effects (ATEs) of 8.3% and 32.8%, respectively. These results indicate that the treatment helped participants feel more empowered in their professional and political environments, which could lead to increased engagement and assertiveness in these areas;

- However, the intervention had mixed effects on other dimensions. The modest improvement in the “Autonomous” category (ATE of 9.9%) shows that while participants felt more autonomous, the effect was relatively small. Additionally, the treatment had a smaller positive effect on “Controlling” (ATE of 5.1%), suggesting only a slight reduction in controlling behaviors;

- A concerning outcome was the decrease in the “Impersonal” category, with an ATE of −20.8%. This suggests that the intervention might have inadvertently increased participants’ impersonal feelings, which could indicate a distancing effect or a decline in personal engagement. This aspect requires further investigation to understand the underlying causes and to adjust the intervention to mitigate such negative outcomes;

- The decline in “Locus of Control—Interpersonal” (ATE of −25.0%) is another area that warrants further exploration. This negative effect suggests that participants felt less in control of their interpersonal relationships post-treatment. Understanding the factors contributing to this decline is crucial for refining the intervention to better support interpersonal dynamics;

- Overall, the treatment appears effective at enhancing several key areas of personal and social control. The significant improvements in general locus of control and self-efficacy highlight the intervention’s potential to empower women and foster greater personal and professional agency. However, the mixed results in other areas underscore the need for further refinement and targeted adjustments to ensure a more balanced and comprehensive impact across all measured dimensions;

- Future research should focus on addressing the identified weaknesses, particularly in the areas of interpersonal control and impersonal feelings. Additional qualitative data could provide deeper insights into participants’ experiences and the nuanced effects of the intervention. Moreover, expanding the sample size and incorporating a more diverse participant pool in the full study will help validate these preliminary findings and enhance the generalizability of the results.

3.3. Participant Characteristics

Women entrepreneurs are selected with very similar characteristics, such as follows: one year in business with varying degrees of observed financial management practices; a demonstrated capacity for growth in the business; a resident in the sector under study; voluntary participation after learning the objectives and strategies of the project; age between 18 and 60; completion of the initial survey; possession of the required literacy and basic computer skills. The sample will be randomly divided into two groups based on their previous business and academic experience to ensure an equal distribution of academic levels: an experimental group that will receive the tailored business training program called “Mujer 360”, and a control group that will not. This criterion makes it possible to compare the results between the two groups (with and without training) before and after the training (Table 5).

Table 5.

Personal information request.

It also examines the variability in the amount of time spent on running their businesses (Table 6). Overall, the study aims to capture a rich spectrum of entrepreneurial perspectives and practices among rural women in the specified regions, regardless of their business performance prior to training. In addition, some participants lack formal accounting records or do not differentiate between personal and business expenses, while others demonstrate meticulous financial management; however, the absence or quality of accounting records will not be a reason for exclusion from the study.

Table 6.

Knowledge and practices.

3.4. Study Procedures

A quasi-experimental design was used to investigate the impact of a comprehensive training program on rural entrepreneurship for women. The training time of the program is 50 h, taken over a period of three months, and it is distributed as follows: A total of 19 h correspond to interactive virtual sessions led by instructors in a hands-on manner. The remaining 31 h are devoted to autonomous learning (self-paced), offering virtual support to those who require it. University teaching professionals and research members of the NGO EQLab1 are responsible for the academic content of the program and for delivering the “Mujer 360” training.

To determine the impact of the training, questionnaires are used to measure the social and financial performances of the women. The variables associated with social performance are agency, confidence, and self-confidence. From the financial approach, accounting variables such as sales and profits, improvements in business performance, and financial management practices are considered (Table 7).

Table 7.

Business and financial performance.

3.4.1. “Mujer 360” Training

Under the name “Mujer 360”, the Semi-Presential Entrepreneurial Training and Business Empowerment Program trains 150 women entrepreneurs from the rural regions of Daule, Naranjal, and Engabao in Ecuador. Among the objectives is to provide participants with a solid foundation in entrepreneurship and business development, promoting personal, administrative, accounting, and digital skills through dual training (an educational model designed to combine classroom teaching with the economic management of a business). In addition, an intervention protocol is implemented to achieve business success, developing strategies and profitable practices that improve the rational use of available resources in the enterprise. During and after its development, how the training strategies influence the productivity and social performance of the trainees is evaluated.

According to the Institute for Women and Equal Opportunities in Spain (García 1984), to develop the cognitive abilities and intellectual capacities of rural women entrepreneurs with basic education, the following eleven aspects are recommended for inclusion in their training: self-assessment and perception; digital literacy and technology use; basic business skills; financial education; critical thinking and problem solving; leadership and self-confidence; communication skills; innovation and creativity; time management and productivity; sector-specific knowledge; and associativity and teamwork. It is also emphasized that this training should be adapted to the rural context and the specific needs of the women, using practical and participatory methodologies. Continuous support and mentorship are also recommended to reinforce the learning and application of these skills in their enterprises.

In the case of Mujer 360, we focus on the following seven areas:

- Digital literacy and technology use: training rural women in the use of new Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) is fundamental, as it will enable them to access more opportunities and resources;

- Basic business skills: providing training in business management, including topics such as basic accounting, planning, marketing, and sales;

- Critical thinking and problem solving: developing the capacity for analysis, decision making, and creative problem solving is essential for business success;

- Leadership and self-confidence: empowering women and building their self-confidence through workshops and activities that enhance their leadership skills;

- Financial education: offering knowledge on budgeting, saving, investment, and access to financing;

- Communication skills: improving oral and written expression, as well as negotiation and networking skills;

- Time management and productivity: teaching techniques to optimize time use, considering the need to balance household responsibilities with entrepreneurship;

- Associativity and teamwork: encouraging collaboration and networking with other entrepreneurs to strengthen their initiatives.

3.4.2. Recruitment and Assignment to Groups

The participants of the “Mujer 360” training program and the control group are selected in several stages:

- (a)

- Community outreach: information sessions will be held at local community centers and markets and through radio announcements to inform potential participants about the training program;

- (b)

- Screening of candidates: interested women will be screened for eligibility to ensure that they meet the following criteria:

- Age between 18 and 60 years old;

- Residing in Daule, Engabao, or Naranjal;

- Owner of a micro-, small-, or medium-sized business that has been in operation for at least one year;

- Basic reading, writing, and computer skills;

- (c)

- Informed consent: Eligible participants will receive detailed information about the study, including its purpose, procedures, and potential risks and benefits. Those who agree to participate will sign an informed consent form. Once screening is completed, participants will be randomly assigned to either the control group or the intervention group to ensure an unbiased comparison of the effects of the training program. The assignment process will include the following steps:

- Randomization: participants will be randomly assigned to two groups using a computer-generated random assignment list: (i) intervention group: participants in this group will receive the “Mujer 360” training program; (ii) control group: participants in this group will not receive any training during the study period but will be offered training after the study is completed;

- Baseline data collection: Prior to the start of the training, baseline data will be collected from all participants. This will include demographic information, business performance metrics, and self-assessments of agency, confidence, and self-confidence using the MSLQ;

- (d)

- Monitoring and follow-up: Throughout the study, both groups are regularly monitored using periodic follow-up forms to collect ongoing data. The impact of the training strategies on the trainees’ productivity and social performance is evaluated both during and after the study.

3.4.3. Personal Development Indicators

Once the study groups are assigned, we will begin by conducting surveys to measure personal development indicators before and after our “Mujer 360” training. Our indicators include the women’s agency, confidence, and self-confidence variables:

Women’s Agency

Women’s agency refers to the decision-making capacity of their businesses or households. The individual may not actually act or create underlying change in power relations, but they can, through direct decision-making processes or indirect means, move away from routine behaviors and attempt to change their environment or their outcomes. Women’s agency is understood as the “capacity to define one’s own goals and act accordingly” (GEM 2023). This is derived from Sen’s (1985) capabilities approach, which defines “freedom of agency” as the freedom to achieve whatever the individual, as a responsible agent, decides she should achieve. To meet the challenges of current measurement, a unified, multidisciplinary conceptualization is proposed, which includes three crucial elements of agency (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2020): (a) capacity to establish goals, (b) capacity to achieve goals, and (c) capacity to act on goals (Table 8).

Table 8.

Women’s agency.

In Table 4, the Spanish questionnaires used in other studies to measure each of the instruments related to the variable “Women’s Agency” were prioritized. However, when a Spanish questionnaire was not found, it was translated from English following a process that ensures that the essence of the original questionnaire is preserved. Table 4 details the critical measures and dimensions of women’s agency, including the ability to set goals, the ability to achieve goals (“sense of agency”), and the ability to act on goals. For each dimension, the instruments used are provided, both in their original English and adapted Spanish versions, along with the corresponding references to authors and years of publication.

- (a)

- Capacity to establish goals or goal setting

The ability to define value-based goals has been studied in social determination theory, as well as in social psychology (and, more recently, in behavioral economics). While social determination theory has focused on determining whether an individual’s goals and actions are genuinely guided by their own values, the latter disciplines have explored individuals’ inclination and cognitive ability to define goals more broadly. Next, we reviewed the measurement tools used in these disciplines.

- i.

- Motivational autonomy

The most common measure of whether an individual’s actions are “self-regulated” is the Relative Autonomy Index (RAI) (Table 9). This is a direct measure of motivational autonomy, as proposed by (Lee et al. 1991). The measure is based on “self-determination theory” (SDT) in psychology and gauges an individual’s ability to act on what he or she values. It expresses the extent to which a woman faces coercive or internalized social pressure to undertake specific actions in a domain. This contribution addresses a key critique of current autonomy measures that focus on decision making or ignore women’s values.

Table 9.

Relative Autonomy Index (RAI) examples.

The questions were obtained from the self-determination theory (SDT) self-regulation questionnaire. These prompt individuals to rate each of the three possible motivations for their actions in a specific domain, ranging from “never true” (lowest score, 1) to “always true” (highest score, 4). The wording of the survey questions is presented in Table 10.

Table 10.

Structure of the Relative Autonomy Index.

The RAI is the weighted sum of an individual’s scores on the three subscales. The subscale weights are based on their position on the self-determination continuum: −2 for external motivation, −1 for introjected motivation, and +3 for autonomous motivation. Therefore, the RAI varies between −9 and 9. The structure of the RAI is presented in Table 6. Positive scores are interpreted as indicators of the individual’s motivation for their behavior in that a specific domain tends to be relatively autonomous, while negative scores indicate relatively controlled motivation;

- ii.

- Goal-setting ability

The ability to set goals also depends on the process of self-reflection and cognitive space to fully reflect on objectives and associated decisions. This skill was first studied within Locke’s goal-setting theory (1968) and has since been demonstrated to be important for task performance in various environments (Locke and Latham 2006). Goal-setting ability has been primarily studied and measured within industrial and organizational psychology using structured questionnaires and scales aimed at discovering how to enhance performance outcomes within a specific domain.

Locke and Latham’s 53-item Goal-Setting Questionnaire (GSQ), validated in (Hakstian and Cattell 1975), was the first among these tools and laid the groundwork for future adaptation (Table 11). It focuses on employees’ goal-setting strategies and determines the attributes of core goals that may hinder employee performance.

Table 11.

Goal-Setting Questionnaire example.

Although these types of questionnaires go beyond measuring the ability to set well-defined goals, scales from Goal-Setting Questionnaire adaptations, especially simplified versions developed within educational and sports psychology, could be useful for this purpose. For instance, the authors of (Maister et al. 2021) validated a scale that includes questions such as “How often have you set goals for what you want to achieve?” and “How often have you developed specific plans to help you reach your goals?” (ranked from 1 to 9, from “Never” to “very often”). Similarly, in (McCrimmon et al. 2018), the goal-setting scale asks questions such as “How would you characterize your own performance goals?” (ranked from 1—my goals are general (e.g., I “do my best”) to 5—my goals are specific (e.g., I make 20 sales calls)) and “How often do you set specific goals for [X]?” (ranked from 1 = never to 5 = very often);

- (b)

- Capacity to achieve objectives

In social science, the sense of agency has been conceptualized and subsequently measured in accordance with a framework that categorizes control constructs in terms of the interaction between agents, means, and goal-related outcomes (Mendoza-Lera et al. 2017). While the measures under review were not developed with the specific intention of measuring women’s agency, some studies employing them include an examination of gender differences. Furthermore, development programs that aim to empower women have begun to prioritize the sense of agency as a means of enhancing project outcomes. For instance, in a project that taught women in Kenya to market fuel-efficient stoves, researchers observed that incorporating a training component to bolster women’s sense of agency led to increased sales (Molina-Ycaza and Sánchez-Riofrío 2016). The construct utilized to capture the means–ends relationship is the “locus of control”, derived from Rotter’s social learning theory (Pajares 1996; Hernández and García 2008; Rotter 1982). An individual’s locus of control (LOC) is defined as the degree to which an individual believes that events are caused by their own behavior (internal locus of control) versus external factors (external locus of control). The most commonly utilized Locus of Control Scale is Rotter’s original 23-item scale (Hernández and García 2008), which was subsequently revised in (Raven et al. 1998) into an 11-item version (Table 12).

Table 12.

Internal–External (IE) Locus of Control Scale.

This scale has been shown to be effective across a range of disciplines due to its high internal validity. For instance, Heckman and colleagues employed it to assess its predictive capacity for various long-term success outcomes in children who had participated in early childhood education programs or formal education. The construct of control within the agent–means relationship has most often been measured through the concept of self-efficacy, which can be defined as the belief in one’s own abilities to act effectively toward a goal. This should be distinguished from outcome expectancies, which are evaluations of future outcomes based largely on perceived self-efficacy. The concept of self-efficacy was first introduced by Bandura (1977, 1995) and represents a central aspect of his social cognitive theory (López et al. 2006; Rodríguez and Sánchez-Riofrío 2017). In response to theories that focused on locus of control, Bandura observed that even if individuals believe that their behaviors or responses can influence outcomes, they will not attempt to exert control unless they also believe that they can produce the required responses. Two main concepts of self-efficacy, which give rise to two main methods of measurement, were originally proposed by Bandura. He defined self-efficacy as a context-specific judgment of one’s own capabilities. Accordingly, self-efficacy should be gauged by soliciting respondents’ perceptions of their capacity to execute particular actions (Table 13). To illustrate, when evaluating self-efficacy for self-regulated learning, students should be queried about specific actions, such as memorizing information presented in class and textbooks and organizing a distraction-free study space.

Table 13.

Example of Self-Efficacy Scale.

The other principal conceptualization of self-efficacy in the literature is that of a generalized personality trait, which is similar to the previous literature on LOC. Instruments developed to measure generalized self-efficacy assess individuals’ general confidence in their ability to succeed in tasks and situations without specifying the particular tasks or situations in question. This approach allows for the capture of individuals’ general beliefs regarding their personal resources.

The concept of generalized self-efficacy was initially operationalized using a 20-item scale Social learning theory (Rotter 1982). Since then, it has been employed in numerous research projects in developed countries, where it has typically demonstrated internal consistency, with alpha coefficients ranging from 0.75 to 0.90. You can see one example of statements in Table 14.

Table 14.

New General Self-Efficacy Scale example.

The choice of self-efficacy measurement tool depends on the research question. General constructs have been found to be useful in large-scale innovative field studies governed by a broad range of variables and a few specific hypotheses. An interesting example is a study by the authors of (INEC 2022), who found that generalized self-efficacy was the best individual predictor of overall adjustment for East Germans who migrated to the West when the Berlin Wall fell. However, when assessing the effects of a specific program, such as a new curriculum aimed at improving math grades, domain-specific measures of perceived self-efficacy are better predictors of outcomes than generalized measures. Furthermore, in the context of evaluating a program specifically aimed at improving self-efficacy in a particular domain (such as agriculture or entrepreneurship), it is recommended to use task- or activity-based self-efficacy measures (Sánchez-Riofrio et al. 2023).

- i.

- Sense of agency

Finally, some studies have attempted to capture agent–goal relationships directly (sense of agency). The most popular measure is a rating scale to assess freedom of choice and control over one’s own life, prompting the respondent as follows in Table 15.

Table 15.

Example of question to assess freedom of choice.

Because of its brevity, this measure is increasingly used in household surveys in development contexts. It has also been included since its first edition in 1981 in the World Values Survey (WVS), which consists of nationally representative surveys conducted in nearly 100 countries. The WVS is the most comprehensive source of cross-national time-series data on human beliefs and values, and it is of particular interest for the analysis of gender differences in agency. This complements findings that have provided suggestive but not systematic evidence that women have a lower sense of agency than men.

In the fifth edition of the WVS, conducted between 2005 and 2009, another question was added that is conceptually closely related to locus of control: some people believe that individuals can determine their own destiny, while others believe that it is impossible to escape a predetermined fate. Using a scale where 1 means that everything in life is determined by fate and 10 means that people make their own destiny, respondents are asked to indicate which number is closer to their view. In summary, freedom of choice and scales that directly measure agent–object relationships are attractive options for researchers because of their brevity. However, researchers must be careful not to impose excessive cognitive loads on respondents for the sake of brevity;

- (c)

- Capacity to act on goals or goal-directed behavior

Questions for Decision Making within the Household

Women’s ability to act and make decisions on significant aspects of their lives is the third key dimension of agency. Most survey questions on this dimension of agency have focused on capturing decision-making roles within the household across different domains, such as family planning, employment, agriculture, health, consumption, and education. Questions about decision-making roles within the household were first employed in developed countries in the late 1950s and early 1960s. The authors of (Schmidt et al. 2024) introduced the first well-known decision-making module based on the Decision Power Index.

In this index (Table 16), respondents are asked to indicate “who has the final say” regarding eight family decisions, and the response alternatives are weighted from 5 (husband always) to 1 (wife always).

Table 16.

Decision Power Index.

This approach to measuring decision making has not changed or adapted much over time, and its use has increased, particularly in large-scale surveys in developing countries. It is based on the notion that the more decisions an individual makes, the more control she has over her own life (Schwarzer and Jerusalem 1995; Kabeer 1999). Although there is no universally accepted definition or measure for the Women’s Empowerment Index, it is widely accepted that empowerment involves a “process of change” that results from “the ability to make decisions” (Kabeer 1999). Kabeer’s conceptual framework for measuring women’s empowerment, developed in 1999, has laid the foundation for much of the work in this area and is often cited in related literature. The author’s framework consists of three interrelated dimensions: resources (antecedents), agency (process), and achievement (outcomes) (Schwarzer and Jerusalem 1995; Kabeer 1999).

Confidence

- (a)

- Trust

Trust can be defined as the degree of confidence, credibility, and complicity that can exist between two or more individuals. Among the different proposals to measure “trust”, in this research, the first option appears in the book The Trusted Advisor by Maister et al. (2021), where it is called the “trust equation” and where a practical way to define it is offered:

The authors suggest assigning a score from 1 to 10 to each of the four components of the formula, considering their conceptualization as follows:

- (a)

- Credibility: This is the realm of words. Your credibility is high when you have the authority to speak on a subject. For example, a renowned chef with three Michelin stars has credibility to talk about cooking, while someone who spends little time in the kitchen lacks it. Credibility is about actions (Do you follow through on your commitments?);

- (b)

- Intimacy: This refers to emotions. Although the term may be uncomfortable in a professional context, intimacy refers to the degree of openness and candor one can show when dealing with sensitive, hairy, or contentious issues. Without this intimacy, it is impossible to be open and to encourage others to be open to constructively addressing any issue, to get beyond the surface of difficult questions. Trusting someone always involves risk, and intimacy is the degree of assurance that you can trust someone with something without judgment or fear of betrayal;

- (c)

- Reliability is built over time and can be destroyed in a second, unlike credibility, which is more resilient;

- (d)

- Self-orientation: This is a deep motivation. While it is natural to seek some degree of self-interest at work, true leadership involves some degree of seeking what is best for others, the company, or the team. A high level of self-centeredness, where one focuses only on oneself, often leads to a breakdown in trust. This component is critical because it is covered by two unique inputs. High self-centeredness is not simply selfishness. While selfishness undoubtedly implies high self-centeredness, individuals with high self-centeredness may not be characterized by self-centeredness but tend to focus on themselves in their interactions with others.

Trust generates social capital, which, in turn, generates economic development (Shahbaz et al. 2023). This statement can be explained by the fact that a person who trusts is aware of the abilities, attitudes, and skills of the person he or she trusts. Therefore, they direct these elements in the best way to achieve a common goal, either by delegating functions or by working in homogeneous or heterogeneous teams, where each member does his or her best to achieve the goal. This initiates a chain of trust in which A trusts B and B trusts C and D, creating networks that contribute to economic development from small groups of family or friends that grow into diverse communities working for a more equitable society.

The research by (López et al. 2006) demonstrated a way to measure a qualitative variable, such as trust, in quantitative terms to find the relationship with the construction of social capital in the Faculty of Mines of the National University of Colombia (Shahbaz et al. 2023). The questions had closed response options (always, almost always, sometimes, almost never, never, with scores of 100%, 80%, 50%, 10%, and 0%, respectively). The surveys were conducted randomly in different physical spaces of the university (access areas, faculty bus stops, libraries, and university classrooms).

This information was used to calculate the confidence generated by each variable, which is the arithmetic sum of the percentages of each category of interest. Each group was given equal weight. Then, the average trust was calculated for actors such as peers, teachers, and institutional norms and by stratum. Next, the average trust for each stratum was calculated using the arithmetic mean. Finally, trust in the faculty was calculated using the weighted mean, taking into account the weight of each stratum (Table 17).

Table 17.

Variables explained.

In this case, no Spanish version of the work was found, so the questionnaire had to be translated from English to Spanish following a process that ensures that the essence of the original questionnaire is preserved. Table 13 outlines the variable and construct being studied, which is confidence. The measure used to assess confidence is “How trustworthy are you?”, and it is evaluated using the Trust Equation: T = (C + R + I)/S. The reference for the English version of the instrument is Maister et al. (2021).

Self-Confidence

Burns et al. (2016) compared two independently and substantially different measures of self-confidence: a self-report measure and a measure described as “online”. Online measures include confidence and accuracy judgments made after each element in a cognitive task (Shankar et al. 2015). Self-report and online measures have not been compared before, and it is unknown whether they capture the same self-confidence construct.

These measures were also compared with self-efficacy and personality to define self-confidence as an independent construct and to clarify the primary comparison. These results have implications for research in the area of self-confidence. Self-report and online measures cannot be used interchangeably; however, both measures have significant implications for improving academic performance. It is possible that the online confidence construct remains stable throughout life, and the observed overconfidence bias, especially in fluid capacity tasks in older adults, reflects a decline in fluid capacity over time.

- (a)

- Self-Report

The self-report measure of self-confidence was administered in a questionnaire format, asking the respondent to report their confidence levels in specific domains (e.g., social, academic) and overall. Self-reported confidence measures capture a general self-evaluation of confidence, requiring reflection on personal experiences and trends. Measures of this nature have been developed and validated mainly in student populations and used to assess confidence in domains related to academic performance.

In this study, a two-part questionnaire was adapted to measure self-confidence using the Personal Evaluation Inventory (PEI) (Shrauger and Schohn 1995; Shao et al. 2023) and Trait Robustness Inventory of Self-Confidence (TROSCI) (Shrauger and Schohn 1995). The first part measures general self-confidence and was extracted from the six-item self-confidence subscale of the PEI. These items are scored on a 4-point Likert scale from (1) totally disagree to (4) totally agree. The reliability of the general PEI subscale is good, with a Cronbach’s α of 0.71 (Shao et al. 2023).

The second part measures the stability of confidence and consists of eight items extracted from the TROSCI, a scale originally developed to measure self-confidence stability in athletes but that has been adapted for the general adult population. These items are scored on a 9-point Likert scale ranging from (1) completely disagree to (9) completely agree. The reliability of the TROSCI is good, with a Cronbach’s α of 0.88 (Shrauger and Schohn 1995) (N = 268). The reason for using both the TROSCI and PEI is that the TROSCI measures the ability to maintain confidence, capturing the stability of self-confidence rather than general self-confidence, which is measured with the PEI (Table 18).

Table 18.

Variables explained.

In this case, as there were no available works in Spanish, the questionnaire had to be translated from English to Spanish (following a process that ensures that the essence of the original questionnaire is preserved).

Table 14 outlines variables and constructs related to self-confidence. Measures include the Personal Evaluation Inventory (PEI) and the Trait-Robustness of Self-Confidence Inventory (TROSCI). The PEI was developed by (Shrauger and Schohn 1995), while the TROSCI was developed by (Beattie et al. 2011). It is important to note that the Spanish versions of these instruments are not available, only the English versions (Shrauger and Schohn 1995);

- (b)

- Online

The online measure consisted of a post-task question asking the respondent to rate his or her level of confidence that the answer was correct. Online confidence is related to the metacognitive function that informs these types of judgments. Three measures of ability were used along with the confidence rating scales: two for fluid intelligence and one for crystallized intelligence. Each measure of fluid intelligence consists of only 12 items, while the measure of crystallized intelligence consists of 34 items.

The first measure of fluid intelligence is an abbreviated version of Raven’s Advanced Progressive Matrices (APMs) (Singh et al. 2024) and includes 12 items validated for brief use (Skinner 1996), with a Cronbach’s alpha reliability of 0.71. The second measure is the Comprehensive Abilities Battery-Induction (CAB-I), a test of inductive reasoning (Stout 1999). This 12-item measure asks participants to identify patterns in sets of letters and also has good reliability with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.75 (Stout 1999). The third measure is the Word Meanings (WMs) (Singh et al. 2024), which consists of 34 items in which participants select from six options the word that is closest in meaning to a presented target word. In all three tests, each item was followed by a discrete categorical numerical scale (i.e., an 11-point confidence scale ranging from 0 to 100%) on which participants indicated the degree of confidence that they had answered the question correctly.

Technically, confidence scales should range from 100/k to 100 (where k is the number of response options; for example, the APM has eight response options, the CAB-I has five, and WMs has six. In this format, the scale would start at the point corresponding to the probability of producing a correct answer by chance. However, to avoid confusion, a standard 0–100% scale was used, and the responses were adjusted so that any value less than 100/k was set to 100/k. From these three measures and their associated confidence indices, the following were determined: the percentage of correct items, the mean confidence indices, and a calibration score calculated as the difference between the mean confidence and the percentage of correct items.

Positive calibration scores indicated overconfidence. For incomplete data sets for these tasks, confidence and calibration scores were calculated as a function of the percentage of items attempted that were correct rather than the total number of items. Online confidence scores are reliable, with Cronbach’s alpha values ranging from 0.75 to 0.90 (i.e., positive calibration scores indicate overconfidence). In the case of incomplete data sets for these tasks, confidence and calibration scores were calculated based on the percentage correct of items attempted rather than the total number of items). Table 19 summarizes the personal development variables used in this study.

Table 19.

Variables explained.

3.4.4. Missing Data Measurement Alignment with SDGs

To measure the alignment of the “Mujer 360” training program with the Sustainable Development Goals, the study will focus on the following key indicators:

- SDG 4 (Quality Education): improvements in educational attainment and skill acquisition among participants;

- SDG 5 (Gender Equality): increases in women’s agency, confidence, and self-confidence;

- SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth): enhancements in business performance metrics, such as sales, profits, and employment levels;

- Data collection: data will be collected through questionnaires and interviews, assessing both quantitative and qualitative outcomes related to these SDGs.

3.4.5. Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis for this study will involve several steps to evaluate the impact of the “Mujer 360” training program on the intervention group compared to the control group. The analysis will be performed using Stata 18.0 statistical software. The following procedures will be applied:

- Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics will be calculated for all baseline characteristics to summarize the demographic and business-related variables of the participants. Means and standard deviations will be used for continuous variables, while frequencies and percentages will be used for categorical variables. This will help in understanding the initial comparability of the intervention and control groups;

- Baseline Comparisons

Baseline characteristics between the intervention and control groups will be compared using independent t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. This will ensure that there are no significant differences between the groups at the start of the study;

- Effect of the Intervention

The primary analysis will assess the impact of the “Mujer 360” training program on the key outcome variables: business performance, financial management practices, and personal development indicators (agency, confidence, and self-confidence). The following methods will be used:

- Paired t-tests: to compare the pre- and post-intervention scores within each group (intervention and control);

- Independent t-tests: to compare the post-intervention scores between the intervention and control groups;

- Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA): to compare the post-intervention outcomes between groups while controlling for baseline values;

- Longitudinal Analysis

To evaluate the changes over time, a repeated-measures ANOVA will be conducted. This will allow us to assess the effect of the training program at different time points (baseline, midterm, and final). The interaction between time and group (intervention vs. control) will be particularly important in determining the effectiveness of the intervention over the study period;

- Subgroup Analysis

Subgroup analyses will be performed to explore the differential impact of the training program based on key demographic variables such as age, education level, and type of business. This will help identify which subgroups benefit most from the intervention;

- Qualitative Data Analysis

Qualitative data from student interviews will be analyzed using thematic analysis. This involves coding the interview transcripts to identify common themes and patterns related to the participants’ experiences and their perceived impacts of the training program;

- Missing Data

The analysis will account for missing data using appropriate techniques, such as multiple imputation or maximum likelihood estimation, ensuring that the results are robust and unbiased.

4. Expected Results

Our program’s success will be assessed through four main dimensions, each aligning with specific Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). We expect to see significant improvements in women’s agency, confidence, and business performance before and after the Mujer 360 training. The pre-pilot results indicated a 54% increase in perceived self-efficacy, suggesting the program’s potential to empower women and enhance their decision-making capacities. This aligns directly with SDG 5 (Gender Equality), promoting women’s empowerment and enhancing their roles in society.

Participation will be tracked through the enrollment and completion rates of women in the program. High participation rates will indicate progress towards SDG 4 (Quality Education) by ensuring inclusive and equitable quality education and promoting lifelong learning opportunities for all. The pre-pilot outcomes, particularly the 200% increase in general locus of control, suggest that the program is likely to attract and retain participants effectively.

Business performance will be evaluated by examining sales figures of selected enterprises before and after program participation. Improved business performance will align with SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), demonstrating the program’s impact on fostering sustainable economic development. The pre-pilot showed improvements in perceived control over performance (ATE of 8.3%), suggesting that the program can positively impact business outcomes and empower women economically.

Financial growth will be assessed through the analysis of financial statements, indicating improvements and growth within the enterprises. Additionally, the number of suppliers engaged by the businesses before and after program participation will be monitored. These measures support SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) by highlighting the expansion and sustainability of women-led enterprises. The pre-pilot’s mixed results on interpersonal control (−25% ATE) and impersonal feelings (−20.8% ATE) will be addressed in the full study to ensure balanced growth across all dimensions.

Following methodologies similar to those outlined in previous studies (UNESCO 2020; UNESCO 2021), we plan to conduct two follow-up surveys to verify these four dimensions. The initial survey will occur before the training program, the second survey approximately 4–7 months post-program, and a final survey around 12–15 months later.

Participants may achieve access to employment opportunities or private contracts, while others might initiate or enhance their entrepreneurial ventures across various economic sectors. This multifaceted growth will significantly contribute to family livelihoods and women’s economic empowerment, aligning with SDG 5 (Gender Equality) and SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth).

Understanding and enhancing interpersonal skills, administrative and accounting management, and digital tool utilization are crucial for enterprise consolidation and success. The pre-pilot highlighted areas for improvement in interpersonal control, which we aim to address in the full study. These enhancements will be critical for fostering stronger, more sustainable business practices among participants.

To amplify the benefits of entrepreneurship for family economies, concerted efforts are needed from independent activists, governmental organizations, private entities, and others to provide sustained and comprehensive training across various trades beneficial in both the short and medium term. This approach supports SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals), encouraging collaboration among different sectors to achieve sustainable development.

Recent statistics reveal a 33% failure rate among enterprises over the past three years in Daule, with the primary reasons being inadequate training, the absence of a business plan, lack of financing, incorrect expense control, and the absence of a defined direction (Valdivia 2014). Addressing these issues through targeted training and support aligns with SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) and SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure).

Many entrepreneurs lack access to institutions providing appropriate training and support. Additionally, they lack awareness of the tools necessary for business sustainability and growth. Our motivation stems from recognizing the realities faced by women in the region and their constraints. Our objective is the organic growth of both the women and their businesses, contributing to SDG 5 (Gender Equality) and SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth).

The social and labor situation of beneficiaries in rural areas highlights several key areas: gradual improvement in basic services, transportation, and telecommunications; the effects of violence, the lack of better educational opportunities, and limited decision-making abilities due to poverty levels; and limited employment opportunities for women in Daule, Engabao, and Naranjal. These improvements align with SDG 4 (Quality Education), SDG 5 (Gender Equality), and SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure).

In Ecuador, only 50% of women in urban areas have bank accounts, while only 34% in rural areas do. Income in rural areas is often irregular and does not exceed USD 300 monthly. Female-led enterprises in the canton emerge due to the need for economic independence or to support their households, given the high rate of single mothers in rural areas (approximately 38.6%). These efforts support SDG 1 (No Poverty) and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities) by addressing financial inclusion and economic stability.

By addressing these aspects, our program aims to create a holistic impact, enhancing women’s lives and contributing to the Sustainable Development Goals (Valecha 1972) across multiple dimensions. By contributing to the development of women, we inherently foster the development of their communities, creating a ripple effect that promotes broader social and economic growth (Villamar 2020).

5. Conclusions

Ecuador plays a crucial role in the global landscape of MSMEs, with these enterprises constituting the backbone of its business ecosystem, representing 95% of the country’s entrepreneurial environment. This study explores the complex reality of female entrepreneurship in Ecuador’s rural areas, highlighting women as key contributors to economic sustenance. Despite their significant involvement in business activities, largely driven by necessity, women face a range of challenges from gender inequality to severe adversities in rural settings (World Economic Forum 2022). Addressing these challenges is crucial for achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) such as SDG 5 (Gender Equality) and SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth).

This study aims to unravel the essential connections between women’s entrepreneurship, societal progress, and economic rejuvenation, particularly in rural contexts. It underscores the importance of strategic vision, where education and training serve as foundational pillars supporting women entrepreneurs, catalyzing transformative impacts across economic and social realms within communities and extending nationwide (López et al. 2018). This approach aligns with SDG 4 (Quality Education), SDG 5 (Gender Equality), and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities). The research focuses on the Engabao, Daule, and Naranjal regions, identifying them as critical areas for examination due to their geographical role in connecting rural cantons with Guayaquil’s dynamic economic center.

Although training programs for rural women are available in Latin American countries, to the best of our knowledge, none effectively measures the training’s efficiency before and after, limiting the ability to refine and scale the program at a low cost. Existing education and training programs often fail in rural areas due to their generalized nature, which does not account for the specific needs of women or rural contexts. Additionally, in-person courses are impractical for rural women who have limited time and resources for transportation. These programs frequently lack success indicators and do not leverage new educational technologies to standardize content, minimize costs, and invest in program success. Moreover, they often overlook comprehensive approaches, neglecting psychological factors; many women struggle due to entrenched sexism and gender-based violence. Addressing these gaps is essential for achieving SDG 5 (Gender Equality) and SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure).

Limitations of our study include challenges in reaching and engaging rural women, logistical issues related to technology access and internet connectivity, and the need for cultural sensitivity in program design and delivery. The practical difficulties of implementing technology-based training in remote areas may affect the participation and effectiveness. Additionally, the diverse socio-cultural contexts of the regions studied necessitate tailored approaches that consider local customs and practices. These limitations suggest the need for careful consideration in program design and implementation to ensure broad accessibility and impact.

By integrating these strategies and aligning them with the Sustainable Development Goals, the “Mujer 360” program has the potential to empower rural women entrepreneurs, foster sustainable economic development, and drive positive social change in their communities and beyond. The pre-pilot study demonstrates the feasibility of the large-scale study proposed and underscores the program’s potential for significant impact. The social and labor situation of beneficiaries in rural areas highlights key areas for improvement: gradual enhancements in basic services, transportation, and telecommunications, which strengthen the rural–urban connection in Ecuador; the effects of violence, lack of educational opportunities, and limited decision-making abilities due to poverty on women; and the need to consolidate female-led businesses to provide more employment opportunities in Daule. These improvements contribute to SDGs 1 (No Poverty), 4 (Quality Education), and 5 (Gender Equality). Indicators of economic activity related to financial resource management show that only 50% of women in urban Ecuador have bank accounts, compared to 34% in rural areas. In rural areas, income is often irregular and does not exceed USD 300 monthly. Female-led enterprises in the canton emerge due to the need for economic independence or to support their households, given the high rate of single mothers in rural areas (approximately 38.6%). These efforts support SDGs 1 (No Poverty) and 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) by addressing financial inclusion and economic stability.

In summary, this study highlights the critical need for tailored, comprehensive training programs for rural women entrepreneurs in Ecuador. The “Mujer 360” program’s approach—integrating virtual learning, practical tools, and psychological support—addresses the existing gaps and offers a model for empowering women in challenging environments. The findings contribute significantly to the field by providing evidence of effective strategies for enhancing women’s entrepreneurial capabilities and advancing socioeconomic development. This research not only aligns with multiple SDGs but it also sets a precedent for future programs aimed at empowering women and fostering sustainable economic growth.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing, Formal Analysis, Project Administration: A.-M.S.-R. and J.V.-Á. Methodology, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Writing—Review & Editing: M.F.-H. Coordinator of the project, Design of the training methodology, Writing—Review & Editing: O.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research and the APC were funded by a seed grant from the Research Center at Universidad Espíritu Santo.

Institutional Review Board Statement