Abstract

The oil and gas trade is one of the main ways to promote regional economic development by improving the effectiveness of resource allocation. While regional energy cooperation could lead to growth in the energy trade, blind investment will reduce effective yields. Kazakhstan and China maintain a stable oil and gas trade, but resource exports to China are not growing as expected. The aim of this research is to analyze the competitiveness and complementarity of Kazakhstan and China in the oil and gas trade, as well as the main factors affecting the oil and gas trade between Kazakhstan and China. By creating a linear regression equation to analyze the gravity model of the oil and gas trade between Kazakhstan and China, it was revealed that a 1% growth of the gross domestic product in both countries would lead to a 1.471% increase in the oil and gas trade. However, an increase in oil and gas production in Kazakhstan will not contribute to the expansion of the oil and gas trade with China. Kazakhstan and China could improve their oil and gas trade by strengthening financial cooperation, improving energy efficiency, increasing investment in infrastructure such as oil refineries and pipelines, and developing new oil and gas fields in Kazakhstan.

Keywords:

energy cooperation; competitiveness; complementarity; trade combination; oil; gas; Kazakhstan; China 1. Introduction

With technological developments and advances in transportation, the oil and gas trade has progressed from regional to global. Countries can receive oil and gas products by railway, pipeline, and marine transportation. The expansion of trade networks does not equate to the fully guaranteed security of energy supplies, which in recent years have suffered from a number of crises caused by intense international conflicts, with oil and gas prices soaring. The outbreak of the Russian–Ukrainian conflict in 2022 and the Red Sea crisis in 2023 caused the international crude oil price to rise to over USD 100 per barrel and the natural gas price in the European market (Dutch TTF) to increase to about USD 109 per MMBtu (World Bank 2024). It can be seen that more serious geopolitical conflicts could cause major disruptions to important international trade routes and lead to higher commodity prices.

In contrast to extensive globalized cooperation, regional trade achieves shared economic growth and sustainable economic development through cooperative exploration and integration of regional resources. Today, regional cooperation has been applied in various fields such as transportation, energy, infrastructure, trade, and investment. One example is the contribution of the ‘One Belt and One Road’ (OBOR) Initiative to the development of the regional economy. Under the OBOR Initiative, the construction of the China–Laos railway, the Myanmar–China railway, and the China–Kyrgyzstan–Uzbekistan highway has facilitated regional transportation, the construction of the Kazakhstan–China oil pipeline, the Central Asia–China gas pipeline system, and the gas pipeline ‘Power of Siberia’ has ensured the security of energy supply, and the investment in renewable energy projects has promoted the development of the abundant natural resources of Central Asian and Southeast Asian countries.

Kazakhstan is not only a neighboring country of China but also an important partner in regional cooperation among the Central Asian countries. China and Kazakhstan established diplomatic relations in 1992, and they announced the development of a comprehensive strategic partnership in 2011. Since the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and Kazakhstan, these two countries have maintained good political trust and trade cooperation. In 2013, the President of the People’s Republic of China, Xi Jinping, first proposed the initiative to jointly build the ‘Silk Road Economic Belt’ in Kazakhstan. The introduction of this initiative demonstrated the increased opportunities for Kazakhstan’s development as a bridge between the Eurasian continents in the process of building ‘One Belt and One Road’. The new economic policy ‘Bright Road’ proposed by Kazakhstan in 2014 has strong complementarities with the OBOR Initiative in terms of infrastructure, investment and trade, industry and transport, cultural exchanges, etc. The Minister of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, Wang Yi, once commented that Kazakhstan is an authoritative strategic partner of China in the region. Bilateral trade turnover between China and Kazakhstan increased from USD 28.59 billion in 2013 to USD 41 billion in 2023, with the total volume of bilateral trade continuously expanding (the Administration of Customs of the PRC). According to the Bureau of National Statistics of Kazakhstan, China overtook Russia as Kazakhstan’s largest importer in 2023. The main Chinese goods imported by Kazakhstan are passenger cars, footwear, car bodies, and telephone sets. The main commodities exported from Kazakhstan to China are copper ores, uranium, wheat, crude oil, natural gas, etc. (Bureau of National Statistics of Republic of Kazakhstan 2024). From the above analysis, the conclusion can be drawn that future regional cooperation between the two countries will strengthen the energy, logistics, and infrastructure industries.

Kazakhstan is one of the world’s largest producers of fossil resources, with about 30 billion barrels of crude oil and 2.7 trillion cubic meters of natural gas reserves (BP 2020). Energy cooperation between China and Kazakhstan began in 1997 and has expanded to include the upstream, midstream, and downstream sectors of the oil and gas industry, for example, the first investment project of the China National Petroleum Cooperation (CNPC) in Kazakhstan JSC ‘CNPC-Aktobemunaygas’, the exploration of Karachaganak oilfield, the modernization of Shymkent Refinery, and the operation of oil and gas pipelines, etc. Oil trade between China and Kazakhstan began with the completion of the ‘Kazakhstan-China oil pipeline’ in 2006, which is China’s first direct oil import pipeline allowing oil imports from Central Asia. With the largest gas pipeline system in Central Asia, the ‘Central Asia-China gas pipeline’, Kazakhstan is not only the most important transit country but also a gas exporter to China.

In general, Kazakhstan is the first Central Asian country and participant in the ‘One Belt and One Road’ Initiative to engage in energy cooperation with China. Their bilateral trade is characterized by the consistency of economic objectives and the complementarity of resources. However, it should be recognized that the oil and gas trade between China and Kazakhstan still faces many risks. The risk factors are mainly focused on the volatility of international energy markets, complex investment policies, and domestic gas shortages.

The growing trend of regional cooperation, the concerns about energy security issues, and the questioning of the necessity of cooperation due to geopolitical conflicts prompted us to conduct a study of energy cooperation between Kazakhstan and China. The results of this study will help to understand the current competitiveness and complementarity of Kazakhstan and China in the oil and gas trade.

The structure of this paper consists of five sections. Section 2 provides a brief related review of the literature. Section 3 introduces the main research methodology. Section 4 describes the current status of the oil and gas trade between Kazakhstan and China and analyzes the competitiveness and complementarity of the oil and gas trade. Section 5 summarizes the results of the analysis and draws conclusions from the study, making recommendations for future energy cooperation between Kazakhstan and China.

2. Literature Review

Regional cooperation has been considered one of the most efficient forms of economic cooperation, and the oil and gas trade is a common method of regional cooperation. The issues of security of energy supply, energy efficiency, and import and export dependence related to the regional energy trade among developing countries have been discussed by many scholars.

On the one hand, some scholars have emphasized the role of regional cooperation in breaking down barriers to trade cooperation and promoting economic development, infrastructure construction, and energy supply, thus making regional cooperation increasingly important (Huang 2016; Sarker et al. 2018; Soyres et al. 2020). On the other hand, a number of scholars have questioned the mismatch of resources, trade dependence, potential excessive debt, and corruption problems arising from regional cooperation (Quazi 2014; Fazekas and Tóth 2018; Liu 2019; Wang et al. 2020). This set of issues is also closely linked to the development of energy cooperation programs. The study of these issues will enable a more accurate evaluation of the effectiveness, necessity, and sustainability of regional energy cooperation.

Due to increasing concerns about climate change, the growing energy demand, and deteriorating energy security, energy efficiency has become a focus of attention for governments in all countries. Harmonious development of the country’s economy requires an efficient energy supply, which is formed on the basis of complementary economic policies in the energy sector (Borodina et al. 2022). Otsuka A. and Goto M. concluded from the evaluation of the energy efficiency of the regional economy that agglomeration economies affect the level of energy efficiency of the regional economy (Otsuka and Goto 2015). Sarbassov Y., Kerimray A., et al., in their study indicated that the Kazakh energy system is less efficient than most other national energy systems and improving energy efficiency will contribute to Kazakhstan’s energy export potential and local environment protection (Sarbassov et al. 2013). Orynkanova Z., Baizholova R., et al., analyzed the factors related to the low energy efficiency and high energy intensity of Kazakhstan’s economy and suggested energy-saving measures to improve the energy efficiency indicators of Kazakhstan’s economy (Orynkanova et al. 2020). As the country with the highest increase in energy consumption, China must adopt environmental policies to improve energy efficiency in order to solve the increasingly contradictory relationship between energy supply and demand and serious environmental pollution (Li and Lin 2017; Wu et al. 2020). Kuzmynchuk N. and Kutsenko T. found that energy marketing made it possible to generalize the competitive advantages of market participants and use tools of fiscal regulation for introducing national energy-saving technologies based on sustainable development (Kuzmynchuk et al. 2024).

Another advantage of improving energy efficiency is the reduction of energy supply risks. Constantini V. and Gracceva F. found that the growing dependence on energy imports and insufficient diversification will increase the risk of a demand–supply imbalance, which will lead to the destabilization of exporting regions due to insufficient demand (Costantini et al. 2007). For oil-exporting countries, investing in renewable energy can release more oil and natural gas resources into export markets, which can improve economic efficiency and compensate for domestic energy consumption (Fattouh et al. 2019). The issue of energy security in the Chinese market is also related to dependence on imported resources and the uneven distribution of resources between the east and west regions (Li et al. 2020).

Many researchers agree that energy security has a huge impact on economic development and that a reduction in energy supply can lead to a slowdown in production and a downward trend in the economy (Ellabban et al. 2014; Balashov 2023). Based on this view, a number of scholars have emphasized that energy cooperation between Kazakhstan and China has brought more economic benefits to both countries. At the present stage, Kazakhstan’s economy is dependent on the export of natural resources (rare metals, oil, and natural gas) and cooperation with China can bring stable investment and advanced technology to the development of Kazakhstan’s industry (Kalyuzhnova and Lee 2014; Raimondi 2019; Özcan and Tutus 2022). Both the modernization project of Shymkent Refinery and the construction of oil and gas pipelines have made Kazakhstan more significant in the international energy market.

However, some studies contradict this view. Some experts have indicated that Kazakhstan should suspend gas exports and put all domestic gas into gasification reforms in eastern and northern Kazakhstan to meet the country’s plan for a low-carbon economy. A few researchers have argued that energy cooperation with Central Asian countries would cause economic losses due to political risks (Dong 2021). Tang B.J. stated that most of the oil and gas projects in Central Asian countries are occupied by European and Russian oil companies, making it difficult for China to receive a high return on its investment in the Central Asian energy market (Tang et al. 2023). For more literature reviews on the impact of energy cooperation on the regional economy and the major opportunities and challenges of energy cooperation with Central Asian countries, please refer to the following articles (Sorbello 2018; Smagulova 2021; Dong et al. 2020; Wang et al. 2023).

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Index of Comparative Advantage

Generally, the trade activities between two countries are analyzed using the theory of comparative advantage to explain the necessity of the trade activities. Some economists believe that an important part of the country’s economic growth is realized through the trade activities conducted through differences in comparative advantage (Matsuyama 1992; Lucas 1988). The Balassa index was introduced by Hungarian economist B. Balassa in 1965 to measure a country’s comparative advantage in a particular industry through its share of exports. In the field of research, the Balassa index is widely used in national economic reports published by international organizations (World Bank, United Union) and in the works of scholars from various countries (De Benedictis and Tamberi 2001; Siddique et al. 2020), with the aim of measuring the strengths of countries in international trade and investment.

The Balassa revealed comparative advantage (RCA) index is expressed as (De Benedictis and Tamberi 2001):

where:

- Xkj is the exports of product k by country j.

- Xj is the total exports of country j.

- Xkw is the total world exports of product k.

- Xw is the total world exports across all sectors.

If the RCA index of country j is greater than 1, it means that country j has a comparative advantage in commodity i. The relative advantages of the two countries in commodity i can also be visualized by comparing their RCA index results.

3.2. Index of Complementarity

Before analyzing the trade complementarity of two countries, the trade combination situation between them should be studied. The Trade Combination Degree (TCD) index is used to reflect the situation of bilateral trade. The TCD index allows us to understand the mutual dependence of the two countries. The TCD index is calculated as follows (Wang and Xu 2019):

where:

- Xab is the exports from country a to country b.

- Xa is the total exports of country a.

- Mb is the total imports of country b.

- Mw is the total imports of the world.

If the result of TCDab is greater than 1, it reflects the importance of country m in country n’s import market. Due to the asymmetry of trade, the TCDab is not always equal to the TCDba. After analyzing the degree of combination of bilateral trade, it is possible to conduct further study on specific export commodities and relative industries. It is commonly accepted that the trade of commodities between two countries is complementary if the commodity exports of country m coincide with the imports of country n. The Trade Complementary Index (TCI) was proposed by Australian economist P. Drysdale in his works. The formula of TCI is defined as follows (Drysdale 1969):

where:

- RCAkxa is the comparative advantage of country a by exports product k.

- RCAkmb is the comparative disadvantage of country b by imports product k.

3.3. The Gravity Model of Trade

The gravity model of trade represents the magnitude of bilateral trade between any two countries by analogy with the ‘gravity equation’. This concept was first applied to examine the effects of country size and location on international trade by the economists Walter and Peck (1954). The Dutch economist J. Tinbergen (1962) incorporated the concept into a model. The gravity model of trade can be expressed as follows:

where:

- GDPa and GDPb represents the gross domestic production for both countries a and b.

- Dab is the geographical distance between the two countries.

The original model considers only the value of domestic production and the effect of distance on bilateral trade. The natural logarithm of all relevant variables is used to estimate the trade gravity equation for a given commodity to obtain a log-linear equation. The linear equation can be calculated using ordinary least squares regression. The log linear equation of oil and gas trade can be written as follows:

where:

- β0 is a constant.

- OPa is the volume of crude oil production of country a.

- GPa is the volume of natural gas production of country a.

- ε is the error term (factors that may have an impact on trade).

The empirical analyses conducted are based on panel data. The variables analyzed are a country’s gross domestic production, export value, and import value, with data obtained from the World Bank database. Data about the oil production, gas production, and oil and gas export value are from a country’s Bureau of National Statistics and reports from international energy organizations (British Petroleum, International Energy Agency, etc.).

4. Analysis

Regional cooperation provides an important opportunity for many countries to address the issue of sustainable energy demand. In a stable geopolitical context, it is more efficient and safer to transport oil and gas through cross-border pipelines. Energy trade between China and Kazakhstan is mainly carried out through pipeline transport, which is analyzed below.

4.1. Status of the Oil and Gas Trade between China and Kazakhstan

China and Kazakhstan are mutual neighbors and important trading partners. In particular, the bilateral trade volume between the two countries has been growing in recent years. China is one of the world’s largest economies, and the trade between China and Kazakhstan has effectively led to regional economic development. In 2023, the total exports from Kazakhstan to China were USD 14,712.13 million, accounting for 0.43% of China’s total imports (Administration of Customs of the PRC). In the same period, the total imports to Kazakhstan from China were USD 16,757.53 million, accounting for 27.4% of Kazakhstan’s total imports. Resources such as crude oil, refined products, and natural gas accounted for the largest share of Kazakhstan’s total exports to China.

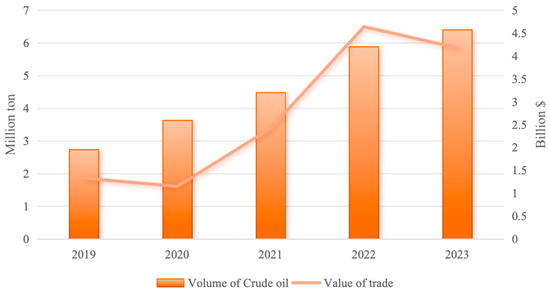

The rapid economic development of China has led to an increase in energy demand, which matches the structure of Kazakhstan’s economic structure, based on natural resource exports. According to the data published in the Blue Book of China’s Oil and Gas Industry Development Analysis and Outlook Report (2023–2024), China’s crude oil consumption grew rapidly to 756 million tons in 2023, with an oil import dependence of 72.9%. Natural gas consumption was 391.7 billion m3, with a gas import dependency of 42.3%. This report indicates that China’s oil and gas demand will continue to grow in 2024 (China Petroleum Enterprise Association 2024). Therefore, the purpose of energy trade between Kazakhstan and China is to diversify and ensure the stability of the oil supply. The construction of the Kazakhstan–China oil pipeline marked the beginning of energy cooperation between the two countries. Figure 1 shows the volume and value of the crude oil trade between Kazakhstan and China over the last five years.

Figure 1.

The volume and value of crude oil trade between Kazakhstan and China. (Source—compiled by authors according to the data of Bureau of National Statistics of Kazakhstan).

As can be seen in Figure 1, the oil trade between the two countries has maintained an upward trend through the world pandemic of 2020 and the geopolitical conflict of 2022. In 2023, China imported 6.41 million tons of crude oil from Kazakhstan, accounting for 1.14% of China’s total crude oil imports (Administration of Customs of the PRC). In China’s crude oil import market, Russia and Saudi Arabia account for the largest shares of the market, Kazakhstan has an insignificant market share but stable export volume.

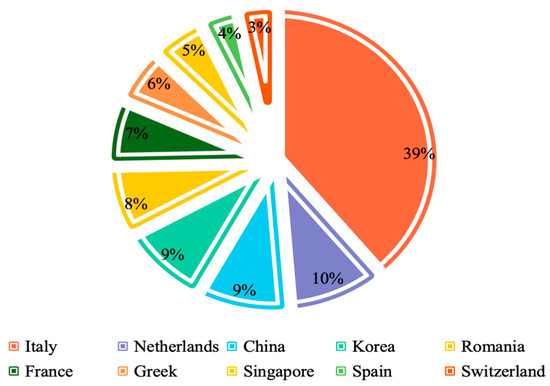

Crude oil production in Kazakhstan amounted to 90 million tons, including 70.6 million tons for exports in 2023 (Bureau of National Statistics of Republic of Kazakhstan 2024). In the structure of Kazakhstan’s oil exports, the share for European countries (Italy, Netherlands, and France) is greater than the share for Asian countries (China and Korea). Figure 2 presents the structure of Kazakhstan’s oil exports in 2023.

Figure 2.

The structure of Kazakhstan’s oil exports in 2023. (Source—compiled by authors according to the data of Bureau of National Statistics of Kazakhstan).

Figure 2 shows that China is an important oil trading partner for Kazakhstan. The continuous transportation of crude oil through the ‘Kazakhstan-China oil pipeline’ is an indication of the significance that Kazakhstan attaches to trade relations with China and the positive role that China plays in helping to diversify Kazakhstan’s oil exports.

It is worth noting that the assignment of Kazakhstan’s oil exports is related to the foreign operators involved in the development of oil fields in Kazakhstan. According to the annual report of the national oil and gas company of the Republic of Kazakhstan ‘KazMunayGas’, the Kazakhstan company ‘KazMunayGas’ has the largest share of oil production (34%), followed by Chevron Corporation (22%), ExxonMobil Corporation (12%), Eni S.p.A (9%), China National Petroleum Corporation (7.5%), and other operators (15.5%). Foreign oil companies have a greater share of oil production and a larger volume of crude oil is exported to Italy, the Netherlands, and other European countries.

From the above analysis, it can be concluded that Kazakhstan is a large crude oil producer and the oil trade between Kazakhstan and China is in accordance with the current trend of China’s energy demand. The energy cooperation between the two countries will continue to strengthen.

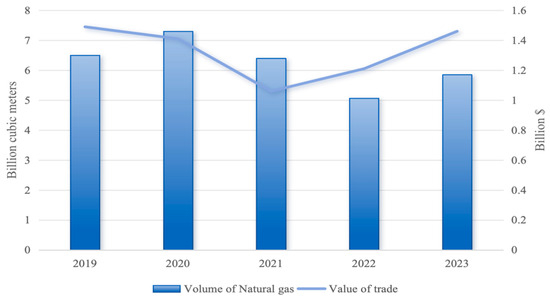

The natural gas trade between Kazakhstan and China started later than the oil trade. Central Asia’s gas export strategy was previously based on exporting to Russia and then to Europe. Natural gas cooperation between Central Asia and China began with Turkmenistan, and then Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan joined in to allow gas exports to China. The ‘Central Asia-China’ gas pipeline system consists of three parallel pipelines with a transportation capacity of 55 billion cubic meters (Bcm) per year. Kazakhstan only established gas trading relations with China in 2019, increasing gas exports to China via the ‘Central Asia-China’ gas pipeline to 10 billion m3 per year. Figure 3 illustrates the volume and value of natural gas trade between Kazakhstan and China over the last five years.

Figure 3.

The volume and value of natural gas trade between Kazakhstan and China. (Source—compiled by authors according to the data of Bureau of National Statistics of Kazakhstan).

In 2023, Kazakhstan exported 5.8 billion m3 of natural gas worth USD 1.43 billion to China (Bureau of National Statistics of Republic of Kazakhstan 2024). In terms of gas exports over the last five years, Kazakhstan’s gas exports to China have not increased significantly, mainly due to the growing demand for gas in the domestic market. Since 2021, Kazakhstan has gradually stopped exporting natural gas to other countries except China.

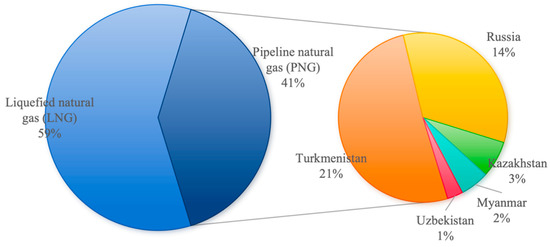

China is the largest consumer of natural gas in Asia. China’s natural gas consumption in 2023 was 394.5 billion m3, of which 235.3 Bcm was from domestic production and 165.6 Bcm was from imports. China’s natural gas imports include pipeline natural gas (PNG) and liquefied natural gas (LNG). PNG imports are mainly from Turkmenistan, Russia, Kazakhstan, and Myanmar. Most LNG deliveries from Australia, Russia, Qatar, and Malaysia. Figure 4 demonstrates China’s total natural gas imports and pipeline gas imports in 2023.

Figure 4.

China’s total natural gas imports and pipeline gas imports in 2023. (Source—compiled by authors according to the data of Administration of Customs of the PRC).

Figure 4 shows that gas imported from Kazakhstan accounts for 3% of China’s total gas imports. Although gas production in Kazakhstan is less than that in Russia and Turkmenistan, the natural gas trade between Kazakhstan and China will not be disrupted in the short term. Benefiting from the development of new gas fields, Kazakhstan signed a new three-year contract with China to continue exporting gas to China in 2023.

4.2. The Competitive Advantages of China and Kazakhstan in the Oil and Gas Sector

Based on the official data published by the World Bank, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), the Bureau of National Statistics of Kazakhstan, and the Administration of Customs of the PRC, the revealed comparative advantage (RCA) index for Kazakhstan and China in the oil and gas trade was calculated using Equation (1). Table 1 reflects the dynamics of the RCA in the past few years.

Table 1.

The RCA index of Kazakhstan and China in the oil and gas trade.

Table 1 defines that the RCA index of Kazakhstan’s oil and gas trade is greater than the RCA index of China in the same period. Kazakhstan’s rich oil and gas resources have a higher export strength in oil and gas resources. The RCA index of China’s oil and gas trade is less than 0.8, indicating that China has weak international competitiveness in the oil and gas trade.

4.3. Index of Complementary between China and Kazakhstan in the Oil and Gas Sector

Firstly, the Trade Combination Degree (TCD) index is calculated to understand the degree of mutual dependence between China and Kazakhstan. As the trade imports and exports of two countries are not equal, two scenarios for Kazakhstan as an exporter (TCDKC) and China as an exporter (TCDCK) are calculated separately. In order to visually compare the trade combination of China and Kazakhstan, the results of Russian and Italian trade data with Kazakhstan are used for comparison. Russia and Italy are larger trading partners for Kazakhstan and participants of the OBOR Initiative (Italy exited from the OBOR Initiative in 2023). The original data were retrieved from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank, the Bureau of National Statistics of Kazakhstan, Bank of Russia, Federal State Statistics Services, and the Administration of Customs of PRC. Using Equation (2), the results of the trade combination degree of these countries over the last few years are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

The TCD index between Kazakhstan, China, Russia, and Italy.

Table 2 reveals that the trade combination degree index of Kazakhstan and China is always greater than 1, which shows that Kazakhstan is an important trade partner with China as the trade between the two countries continues to grow. The higher value of TCDCK indicates that Kazakhstan’s import trade is becoming more connected with China. With the promotion of the OBOR Initiative, bilateral trade between China and Kazakhstan has become more frequent. Moreover, Russia and Kazakhstan have maintained close trade relations for a long time for historical and political reasons. Italy is the largest importer of Kazakhstan’s oil, and the trade between Italy and Kazakhstan is mainly based on raw material imports.

In order to understand the current situation and characteristics of the oil and gas trade involving Kazakhstan, the trade complementarities are calculated by using Equation (3). Since Kazakhstan’s gas exports to China began at the end of 2018, the calculation of the TCI index is based on data on the oil and gas trade between the two countries for the period from 2019 to 2023. The original data were obtained from the IMF, the International Energy Agency, the Energy Institute, etc. Table 3 illustrates the results of the Trade Complementary Index (TCI) between Kazakhstan and China in the oil and gas trade.

Table 3.

The TCI index of Kazakhstan and China in the oil and gas trade.

The results of the TCIKC demonstrate that the oil trade between Kazakhstan and China is more complementary than the natural gas trade. The complementary advantages of the oil trade have tended to grow, while the complementarities of natural gas have shown a weaker tendency.

4.4. The Analysis of the Gravity Model of the Oil and Gas Trade

For a better understanding of the future potential of trade in oil and gas resources between Kazakhstan and China and its impact on the economy, a gravity analysis of the oil and gas trade is conducted on the basis of the linear regression Equation (6) and the relative official data.

TKC means the total value of oil and gas trade between Kazakhstan and China, according to data obtained from the Bureau of National Statistics. GDPK*GDPC means the GDP multiplication of Kazakhstan and China, based on relative data retrieved from the World Bank. OPK and GPK are the oil and gas output capacities of Kazakhstan, as published by BP World Energy Statistical Review. εKC represents the factors that may have an impact on trade between Kazakhstan and China. Considering that there are no factors such as political conflicts and trade frictions between Kazakhstan and China and they are not subject to international economic sanctions, it can be assumed that εKC = 0.

In order to determine the relationship between the variables more accurately, the official data from 2015 to 2023 were collected and the multiple covariances of the variables were analyzed using the software Stata to avoid regression bias due to the dependent variable; the results of the covariance test analysis are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

The results of covariance test analysis.

The result of VIF is less than 10, which indicates that there is no serious covariance in the regression model.

The regression estimates for each variable that were obtained using Stata are demonstrated in Table 5.

Table 5.

The results of regression estimates for each variable.

According to the regression results, the goodness-of-fit coefficient of the regression model is 0.9047, which indicates that the multiple regression equation has a good fit. Therefore, it is possible to derive the following regression model for the oil and gas trade between Kazakhstan and China:

The regression coefficient for the (GDPK*GDPC) of Kazakhstan and China is 1.4714, indicating that a 1% increase in the value of GDP in the two countries is associated with a 1.471% increase in the oil and gas trade. The growth of the national economy is driving increased demand for oil and gas resources in both countries. The national economy is the main factor affecting the oil and gas trade and energy cooperation between Kazakhstan and China.

The regression coefficient for the oil output of Kazakhstan (OPK) is −0.054, which means that with a 1% increase in the oil output from Kazakhstan, the total oil and gas trade between Kazakhstan and China will decline by 0.054%. There are two main factors contributing to the decline: firstly, the share of Chinese oil companies in Kazakhstan’s oil assignment is less than that of European companies, so the growth of oil output will lead to an increase in exports to Europe and a decrease in exports to China. Secondly, increased oil production in the oil fields of Kazakhstan is mainly achieved by reinjecting natural gas into the reservoir. A total of 31% of natural gas production will be reinjected to increase oil production, which leads to lower gas output.

The regression coefficient of the natural gas output of Kazakhstan (GPK) is −0.149, indicating that with a 1% increase in gas production from Kazakhstan, the total oil and gas trade between the two countries will decline by 0.149%. The major reason for the decline in trade is the growth in domestic demand for natural gas in Kazakhstan. According to the Ministry of Energy of Kazakhstan, gasification levels in Kazakhstan are set to reach 60%, with budgetary allocations of USD 164 million in 2023 (S&P Global 2023). Gas exports to China provide Kazakhstan with an important source of revenue to offset its financial losses on gas demands in the domestic market. In the long term, exports to China will be influenced by growing domestic demand.

5. Conclusions

Energy trade has a positive effect on regional economic development and the efficient allocation of resources in this region. The key to achieving successful regional cooperation is to analyze the trade competitiveness and complementarities between different countries.

Kazakhstan and China are important partners in regional cooperation, especially in the oil and gas trade. Kazakhstan is one of the world’s largest oil and gas producers, and the oil and gas sector is a major industry for economic development. This industry attracts significant foreign investment, and oil and gas exports bring more revenue to Kazakhstan. China is the fastest-growing country in terms of energy demand. In order to ensure energy security, China purchases large amounts of oil and gas resources from major exporting countries. With this supply and demand relationship, energy cooperation between the two countries is compatible with the current economic plans of Kazakhstan and China. To fully explore the potential and comparative advantages and realize the complementary advantages, the white paper on Building the Belt and Road Initiative emphasized the importance of supporting regional integration processes and achieving strategic alignment with Kazakhstan’s ‘Bright Road’ (The State Council of the People’s Republic of China 2023).

From the above analysis, we can draw some conclusions:

- (1)

- From the perspective of trade competitiveness, the oil and gas trade of Kazakhstan has more comparative advantages than China. Looking at the overall situation of trade between the two countries, both the trade combination degree of Kazakhstan to China and China to Kazakhstan are greater than 1, which means that the trade relationship remains at a high level. Regarding the trade complementarities, the oil trade has more complementarities than the gas trade; the result of gravity model analysis also supports this view.

- (2)

- The growth of the national economy has a positive impact on promoting the oil and gas trade between Kazakhstan and China. Under the OBOR Initiative, trade relationships between participating countries have become more frequent and logistics and transportation have become more convenient. National economies are gradually returning to growth after the effects of the world pandemic. In particular, the resumption of production activities has driven China’s energy consumption, which has led to continued growth in energy demand. The high international oil and gas prices caused by geopolitical conflicts in 2022 have boosted Kazakhstan’s economic growth, which will help the country intensify the development of new oil and gas resources.

- (3)

- There are many potential risks associated with the oil and gas trade between China and Kazakhstan. In the case of the oil trade, China faces the problem of a lower share of oil production in Kazakhstan and lower than expected returns on investment. In terms of the natural gas trade, Kazakhstan has continued to reduce gas exports to China due to the rapid growth in domestic demand for natural gas. China faces the risk that Kazakhstan will stop exporting gas, while Kazakhstan faces the hard choice of abandoning highly profitable exports and supplying cheap gas to the domestic market.

In order to improve the oil and gas trade between Kazakhstan and China, some suggestions are proposed to strengthen their energy cooperation. Firstly, Kazakhstan and China should increase the strength of their economies by enhancing financial market cooperation. A high level of bilateral investment cooperation would be more beneficial for the oil and gas trade. Secondly, China could increase trade volumes by investing to help Kazakhstan in the modernization and construction of infrastructure such as oil refineries and gas processing plants and expanding the transportation capacity of oil and gas pipelines. Thirdly, Kazakhstan could get out of the current dilemma by attracting foreign investment to accelerate the development of new oil and gas fields. Kazakhstan could consider improving energy efficiency by increasing the share of renewable energy in the domestic market. As in the Strategy of Kazakhstan ‘Kazakhstan-2050’, the government of Kazakhstan announced a goal to increase the share of renewable energy to 50% in the energy sector of Kazakhstan by 2030 and suggested the use of renewable energy to support the development of the oil and gas industry. In this way, the export of oil and gas can be expanded without affecting domestic energy consumption, which will increase Kazakhstan’s competitiveness in the energy market.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.J.; Methodology, J.J.; Software, X.Z.; Formal analysis, B.D. and X.Z.; Data curation, A.T.M.; Writing—original draft, B.D.; Writing—review & editing, A.V.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Balashov, Mikhail. 2023. Analysis of key directions and proposals to minimize the economic impact of the global energy transition on large energy-intensive industrial consumers of electricity and capacity. Strategic Decisions and Risk Management 14: 164–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borodina, Oksana, Halyna Kryshtal, Mira Hakova, Tetiana Neboha, Piotr Olszak, and Victor Koval. 2022. A conceptual analytical model for the decentralized energy-efficiency management of the national economy. Energy Policy Journal 25: 5–22. [Google Scholar]

- BP. 2020. Statistical Review of World Energy. Available online: https://www.bp.com/content/dam/bp/business-sites/en/global/corporate/pdfs/energy-economics/statistical-review/bp-stats-review-2020-full-report.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2020).

- Bureau of National Statistics of Republic of Kazakhstan. 2024. Foreign trade turnover of the Republic of Kazakhstan (January–December 2023). Available online: https://stat.gov.kz/ru/industries/economy/foreign-market/publications/123068/ (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- China Petroleum Enterprise Association. 2024. Blue Book of China’s Oil and Gas Industry Development Analysis and Outlook Report (2023–2024). Beijing: China Petroleum Enterprise Association. [Google Scholar]

- Costantini, Valeria, Francesco Gracceva, Anil Markandya, and Giorgio Vicini. 2007. Security of energy supply: Comparing scenarios from a European perspective. Energy Policy 35: 210–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Benedictis, Luca, and Massino Tamberi. 2001. A Note on the Balassa Index of Revealed Comparative Advantage. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.289602 (accessed on 15 October 2001).

- Dong, Cong, Xiucheng Dong, and Congyu Zhao. 2020. Research on the Prospects of Oil and Gas cooperation between China and Central Asia under the background of “One Belt One Road”. Theory and Practice 2: 153–56. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Xu. 2021. Risk analysis and recommendations of oil and gas cooperation between China and Central Asia. World Petroleum Industry 28: 72–78. [Google Scholar]

- Drysdale, Peter. 1969. Japan, Australia, New Zealand: The Prospect for Western Pacific Economic Integration. Economic Record 45: 321–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellabban, Omar, Haitham Abu-Rub, and Frede Blaabjerg. 2014. Renewable energy resources: Current status, future prospects and their enabling technology. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 39: 748–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattouh, Bassam, Rahmatallah Poudineh, and Rob West. 2019. The rise of renewables and energy transition: What adaptation strategy exists for oil companies and oil-exporting countries? Energy Transit 3: 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazekas, Mihaly, and Bence Tóth. 2018. The extent and cost of corruption in transport infrastructure. New evidence from Europe. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 113: 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Yiping. 2016. Understanding China’s Belt & Road Initiative: Motivation, framework and assessment. China Economic Review 40: 314–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kalyuzhnova, Yelena, and Julian Lee. 2014. China and Kazakhstan’s Oil and Gas Partnership at the Start of the Twenty-First Century. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 50: 206–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kuzmynchuk, Nataliia, Tetiana Kutsenko, Serhii Aloshyn, and Oleksandra Terovanesova. 2024. Energy Marketing and Fiscal Regulations of competitive energy efficiency system. Economics Ecology Socium 8: 112–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Jian, Yuanqi She, Yang Gao, Mingpeng Li, Guiru Yang, and Yanjun Shi. 2020. Natural gas industry in China: Development situation and prospect. Natural Gas Industry B 7: 604–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Jianglong, and Boqiang Lin. 2017. Ecological total-factor energy efficiency of China’s heavy and light industries: Which performs better? Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 72: 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Junxia. 2019. Investments in the energy sector of Central Asia: Corruption risk and policy implications. Energy Policy 133: 110912. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, Robert E., Jr. 1988. On the mechanics of economic development. Journal of Monetary Economics 22: 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuyama, Kiminori. 1992. Agricultural productivity, comparative advantage, and economic growth. Journal of Economic Theory 58: 317–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orynkanova, Zhanar, Raissa Baizholova, and Aigul Zeinullina. 2020. Improving the Energy Efficiency of Kazakhstan’s Economy. Journal of Environmental Management and Tourism 11: 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otsuka, Akihiro, and Mika Goto. 2015. Estimation and determinants of energy efficiency in Japanese regional economies. Regional Science Policy & Practice 7: 89–102. [Google Scholar]

- Özcan, Merve Suna Özel, and Lütfi Tutus. 2022. China-Kazakhstan Energy Relations After the Cold War. Online Journal Mundo Asia Pacifico 11: 6–20. [Google Scholar]

- Quazi, Rahim. 2014. Corruption and Foreign Direct Investment in East Asia and South Asia: An Econometric Study. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues 4: 231–42. [Google Scholar]

- Raimondi, Pier Paolo. 2019. Central Asia Oil and Gas Industry—The External Powers’ Energy Interests in Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. FEEM Working Paper 6. Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/211165/1/ndl2019-006.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2019).

- Sarker, Md Nazirul, Hossin Md Altab, Xiaohua Yin, and Md Kamruzzaman Sarkar. 2018. One Belt and One Road Initiative of China: Implication for future of global development. Modern Economy 9: 623–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarbassov, Yerbol, Aiymgul Kerimray, Diyar Tokmurzin, GianCarlo Tosato, and Rocco De Miglio. 2013. Electricity and heating system in Kazakhstan: Exploring energy efficiency improvement paths. Energy Policy 60: 431–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smagulova, Sholpan. 2021. Diversification of the economy of Kazakhstan as a priority of industrial development in post-pandemic conditions. Bulletin of ‘Tuean University’, 120–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, Muhammad, Ahsan Anwar, and Muhammad Quddus. 2020. The impact of real effective exchange rate on revealed comparative advantage and trade balance of Pakistan. Economic Journal of Emerging Markets 12: 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyres, François, Alen Mulabdic, and Michele Ruta. 2020. Common transport infrastructure: A quantitative model and estimates from the Belt and Road Initiative. Journal of Development Economics 143: 102415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorbello, Paolo. 2018. Oil and Gas Political Economy in Central Asia: The International Perspective. The International Political Economy of Oil and Gas, 109–124. [Google Scholar]

- S&P Global. 2023. Kazakhstan’s National Energy Report 2023. Available online: https://kazenergyforum.com/wp-content/uploads/files/Kazakhstans-National-Energy-Report-2023.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2023).

- Tang, Baojun, Changjing Ji, and Yuxian Zheng. 2023. Risk assessment of oil and gas investment environment in countries along the Belt and Road Initiative. Petroleum Science 21: 1429–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinbergen, Jan. 1962. Shaping the World Economy. Suggestions for an International Economic Policy. Books. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/1765/16826 (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- The State Council of the People’s Republic of China. 2023. White Paper on Building the Belt and Road Initiative: Major Practice of Building a Community with a Shared Future for Humanity. Available online: http://www.scio.gov.cn/zfbps/zfbps_2279/202310/t20231010_773682.html (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Walter, Isard, and Merton J. Peck. 1954. Location Theory and International and Interregional Trade Theory. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 68: 97–114. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Chao, Ming K. Lim, and Xinyi Zheng. 2020. Railway and road infrastructure in the Belt and Road Initiative countries: Estimating the impact of transport infrastructure on economic growth. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 134: 288–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Shuangying, Yayao Hua, and Ping Wei. 2023. Analysis on the spatial pattern and evolution of China’s petroleum trade under the dual effect of international oil price and “Belt and Road” Framework. Petroleum Science 20: 3945–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Yehui, and Xiaoheng Xu. 2019. A study on the Complementarity of Merchandise Trade between China and CEEC. Paper Presented at the Fourth International Conference on Economic and Business Management (FEBM 2019), Sanya, China, October 19–21; pp. 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. 2024. Global Commodity Prices Level Off, Hurting Prospects for Lower Inflation. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2024/04/25/commodity-markets-outlook-april-2024-press-release (accessed on 25 April 2024).

- Wu, Haitao, Yu Hao, and Siyu Ren. 2020. How do environmental regulation and environmental decentralization affect green total factor energy efficiency: Evidence from China. Energy Economics 91: 104880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).