Understanding the Emergence of Rural Agrotourism: A Study of Influential Factors in Jambi Province, Indonesia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Locations

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Sample Village Profile

2.4.1. Tanjung Lanjut Village

2.4.2. Kuala Lagan Village

2.4.3. Renah Alai Village

2.4.4. Mekar Sari Village

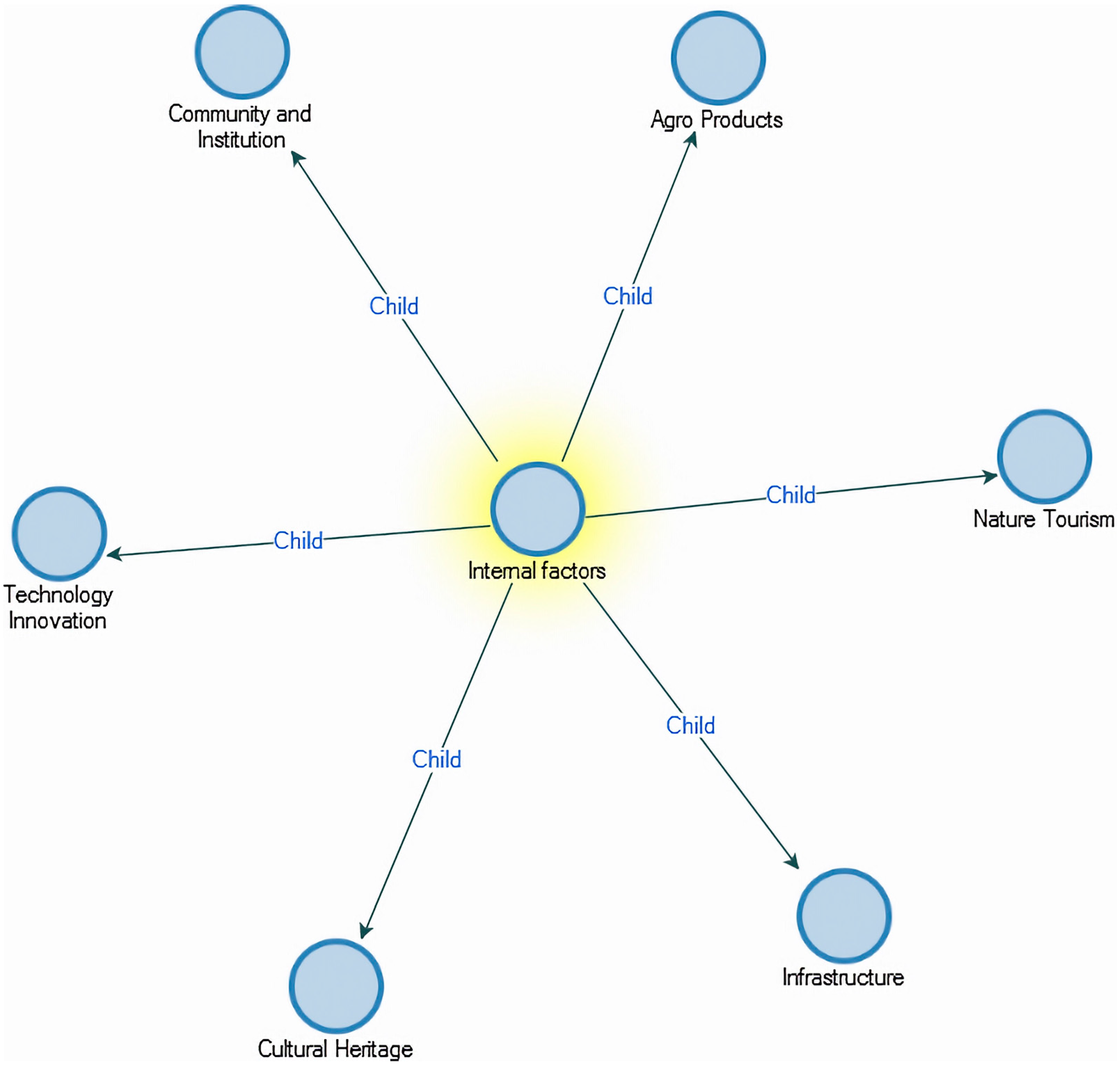

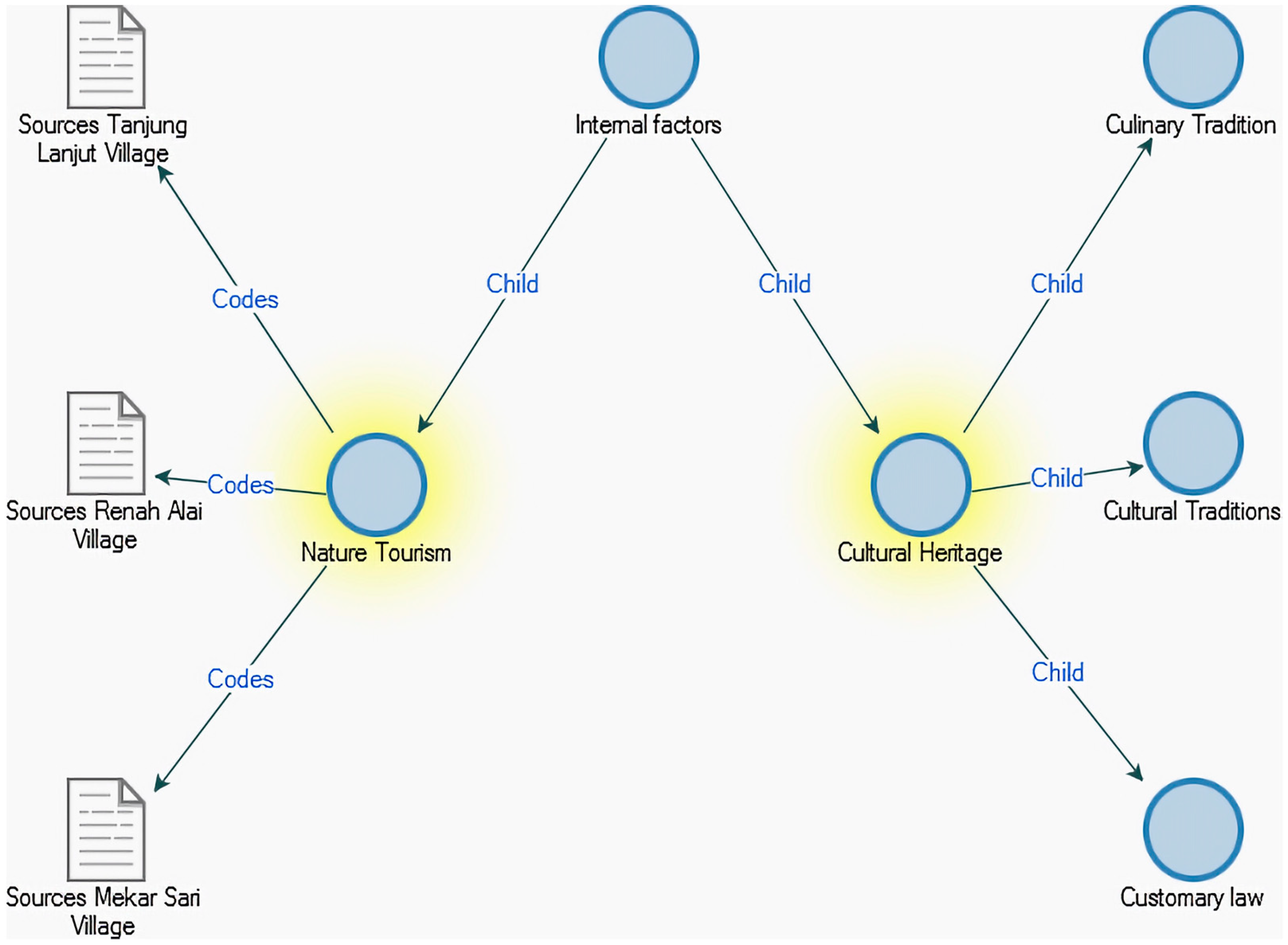

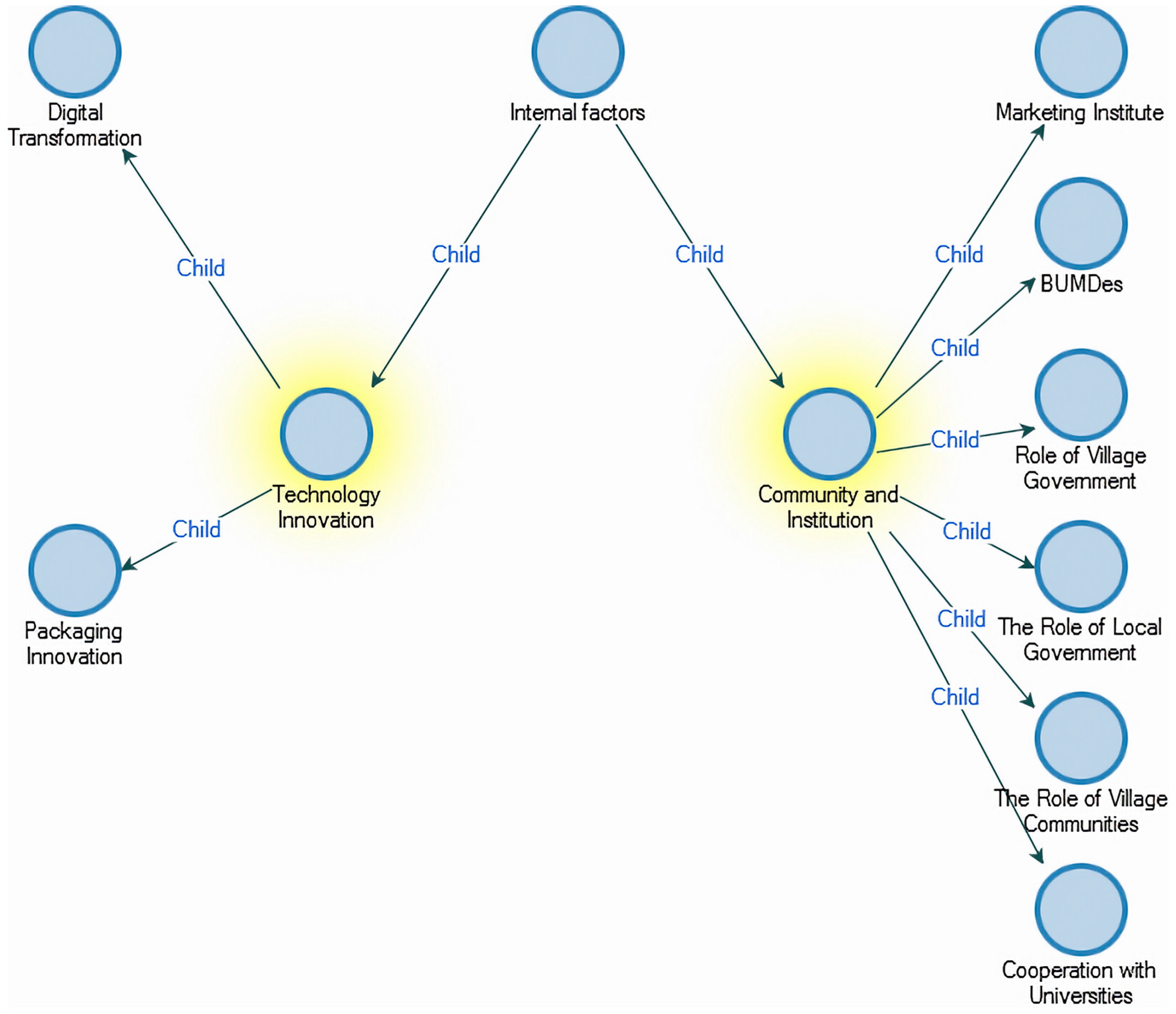

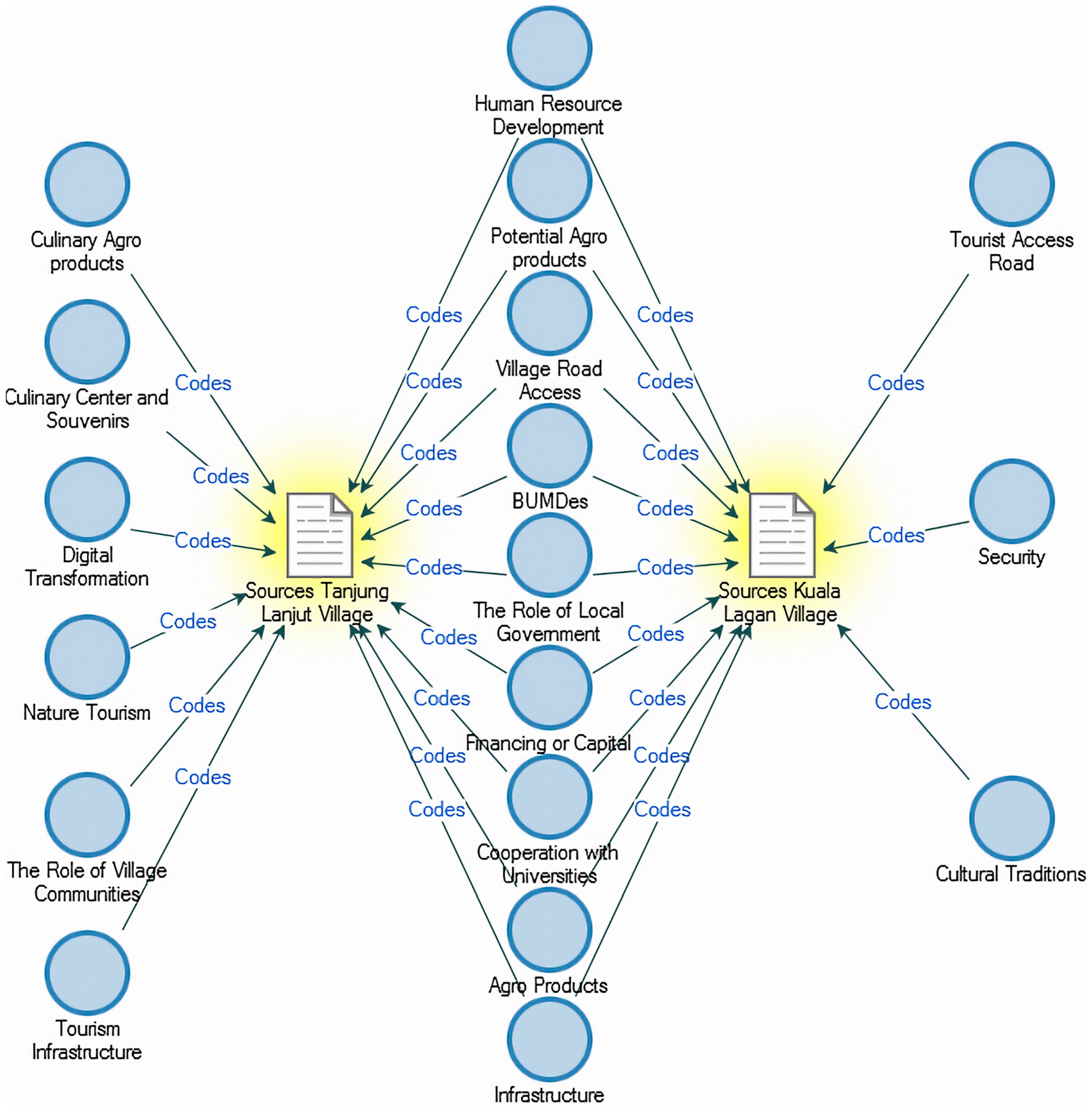

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agafonova, Tatiana, and Ludmila Spektor. 2023. Legal Aspects of Agrotourism Development in the Russian Federation. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 527–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agunggunanto, Edy Y., Fitri Arianti, Edi W. Kushartono, and Darwanto Darwanto. 2016. Pengembangan Desa Mandiri Melalui Pengelolaan Badan Usaha Milik Desa (BUMDES). Jurnal Dinamika Dan Bisnis 13: 67–81. [Google Scholar]

- Akpinar, Nevin, Ilkden Talay, Coşkun Ceylan, and Sultan Gündüz. 2005. Rural women and agrotourism in the context of sustainable rural development: A case study from Turkey. Environment, Development and Sustainability 6: 473–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altassan, Abdulrahman. 2023. Sustainability of Heritage Villages through Eco-Tourism Investment (Case Study: Al-Khabra Village, Saudi Arabia). Sustainability 15: 7172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andayani, S. Ayu, Sri Umyati, Dinar, George M. Tampubolon, Agus Y. Ismail, Umar Dani, Dadan R. Nugraha, and Arjon Turnip. 2022. Prediction model for agro-tourism development using adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system method. Open Agriculture 7: 644–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anita, Reni. 2017. Tipologi Modal Sosial Dalam Pengembangan Kampung Ekologi Batu into Green Kelurahan Temas Kota Batu. Ph.D. thesis, Universitas Brawijaya, Malang, Indonesia. [Google Scholar]

- Anshari, Khairullah. 2018. Indonesia’s Village Fiscal Transfers (Dana Desa) Policy: The Effect On Local Authority And Resident Participation. Jurnal Studi Pemerintahan 9: 619–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anugraheni, Devi N. N., and Sri E. Astutiningsih. 2021. Analisis Strategi Pengembangan Pariwisata Pada Masa Pandemi COVID-19 di Agro Belimbing Moyoketen Tulungagung. AL IQTISHADIYAH Jurnal Ekonomi Syariah Dan Hukum Ekonomi Syariah 7: 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhar, Sharifah N. F. S., Siti N. M. Khanafi, Mohd S. Hassan, and Suzyrman Sibly. 2020. Agrotourism in Malaysia: A Study of its Prospects Among Youth in Pekan Nanas, Pontian. Review of Tourism Research 18: 168–85. [Google Scholar]

- Baranova, Alla, and Svetlana Kegeyan. 2019. Agrotourism as an element of the development of a green economy in a resort area. E3S Web of Conferences 91: 08006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, Carla, and Patience M. Mshenga. 2008. The Role of the Firm and Owner Characteristics on the Performance of Agritourism Farms. Sociologia Ruralis 48: 166–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckmann, Markus, Michael Garkisch, and Anica Zeyen. 2021. Together we are strong? A systematic literature review on how SMEs use relation-based collaboration to operate in rural areas. Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship 35: 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BPS. 2022a. Kecamatan Jangkat Dalam Angka 2022. Kabupaten Merangin: BPS Kabupaten Merangin. Available online: https://meranginkab.bps.go.id/publication/2022/09/26/1298e7087e270a45398da5ab/kecamatan-jangkat-dalam-angka-2022.html (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- BPS. 2022b. Kecamatan Kayu Aro Dalam Angka 2022. Kabupaten Merangin: BPS Kabupaten Kerinci. Available online: https://kerincikab.bps.go.id/publication/2022/09/26/d9b96589f275a1a3b73a3a8f/kecamatan-kayu-aro-dalam-angka-2022.html (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- BPS. 2022c. Kecamatan Kuala Jambi Dalam Angka 2022. Kabupaten Merangin: BPS Kabupaten Tanjung Jabung Timur. Available online: https://tanjabtimkab.bps.go.id/publication/2022/09/26/572a7db36f76603f8d051c65/kecamatan-kuala-jambi-dalam-angka-2022.html (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- BPS. 2022d. Kecamatan Sekernan Dalam Angka 2022. Kabupaten Merangin: BPS Kabupaten Muaro Jambi. Available online: https://muarojambikab.bps.go.id/publication/2022/09/26/1f3d8d475c8bfb01efe06047/kecamatan-sekernan-dalam-angka-2022.html (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- BPS. 2022e. Posisi Cadangan Devisa (Juta US$) 2020–2022. Available online: https://www.bps.go.id/indicator/13/1091/1/posisi-cadangan-devisa.html (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- Buhr, Walter. 2003. What is infrastructure? In Volkswirtschaftliche Diskussionsbeitrage. No. 107–03. Available online: https://www.wiwi.uni-siegen.de/vwl/repec/sie/papers/107-03.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- Burki, Muhammad A. K., Umar Burki, and Usama Najam. 2021. Environmental degradation and poverty: A bibliometric review. Regional Sustainability 2: 324–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busby, Graham, and Samantha Rendle. 2000. The transition from tourism on farms to farm tourism. Tourism Management 21: 635–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çavusoglu, Sinan, Bülent Demirag, Eddy Jusuf, and Ardi Gunardi. 2020. The Effect of Attitudes toward Green Behaviors on Green Image, Green Customer Satisfaction and Green Customer Loyalty. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites 33: 1513–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzitheodoridis, Fotios, and Achilleas Kontogeorgos. 2020. Exploring of a Small-Scale Tourism Product under Economic Instability: The Case of a Greek Rural Border Area. Economies 8: 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Zheng, and Bicheng Diao. 2022. Regional planning of modern agricultural tourism base based on rural culture. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica Section B: Soil and Plant Science 72: 415–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheteni, Priviledge, and Ikechukwu Umejesi. 2023. Evaluating the sustainability of agritourism in the wild coast region of South Africa. Cogent Economics and Finance 11: 2163542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćirić, Miloš, Dragan Tešanović, Bojana K. Pivarski, Ivana Ćirić, Maja Banjac, Goran Radivojević, Biljana Grubor, Predrag Tošić, Olivera Simović, and Stefan Šmugović. 2021. Analyses of the Attitudes of Agricultural Holdings on the Development of Agritourism and the Impacts on the Economy, Society and Environment of Serbia. Sustainability 13: 13729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayan, Muzaki A., and Maheni I. Sari. 2022. Potensi Agrowisata Berbasis Masyarakat. National Multidisciplinary Sciences 1: 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demkova, Michaela, Santosh Sharma, Prabuddh K. Mishra, Dilli R. Dahal, Aneta Pachura, Grigore V. Herman, Katarina Kostilnikova, Jana Kolesarova, and Kvetoslava Matlovicova. 2022. Potential For Sustainable Development of Rural Communities By Community-Based Ecotourism A Case Study of Rural Village Pastanga, Sikkim Himalaya, India. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites 43: 964–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Andreu, Margarita. 2017. Heritage Values and the Public. Journal of Community Archaeology and Heritage 4: 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos-Santos, Maria J. P. L. 2020. Value Addition of Agricultural Production to Meet the Sustainable Development Goals. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 953–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evgrafova, Lyudmila. V, and Aida Z. Ismailova. 2021. Analysis of tourist potential for agrotourism development in the Kostroma region. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 677: 022047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fafurida, Fafurida, Yunastiti Purwaningsih, Mulyanto Mulyanto, and Suryanto Suryanto. 2023. Tourism Village Development: Measuring the Effectiveness of the Success of Village Development. Economies 11: 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faganel, Armand. 2011. Developing Sustainable Agrotourism in Central and East European Countries. Academica Turistica-Tourism and Innovation Journal 4: 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, Martin, Eva Hagsten, and Xiang Lin. 2022. Importance of land characteristics for resilience of domestic tourism demand. Tourism Recreation Research, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajdošík, Tomáš, Zuzana Gajdošíková, and Stražanová Romana. 2018. Residents Perception of Sustainable Tourism Destination Development—A Destination Governance Issue. Global Business Finance Review 23: 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampiccoli, Andrea, and Janet H. Kalis. 2012. Tourism, Food, and Culture: Community-Based Tourism, Local Food, and Community Development in Mpondoland. Culture, Agriculture, Food and Environment 34: 101–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampiccoli, Andrea, Oliver Mtapuria, and Sean Jugmohan. 2020. Community-based tourism and animals: Theorising the relationship. Cogent Social Sciences 6: 1778965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, David R., and Suman K. Chaudhary. 2017. Eco-Tourism dimensions and directions in India: An empirical study of Andhra Pradesh. Journal of Commerce and Management Thought 8: 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunarta, I Ketut, and Fuad D. Hanggara. 2018. Development of agrotourism business model as an effort to increase the potency of tourism village(case study: Punten Village, Batu City). MATEC Web of Conferences 204: 03006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemkhani, Zolfani S., Maedeh Sedaghat, Reza Maknoon, and Edmundas K. Zavadskas. 2015. Sustainable tourism: A comprehensive literature review on frameworks and applications. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja 28: 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Hong, Shuxin Wang, Shouheng Tuo, and Jiankuo Du. 2022. Analysis of the Effect of Rural Tourism in Promoting Farmers’ Income and Its Influencing Factors–Based on Survey Data from Hanzhong in Southern Shaanxi. Sustainability 14: 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- High, Chris, Mark Pelling, and Gustáv Nemes. 2005. Understanding informal institutions: Networks and communities in rural development. Transition in Agriculture, Agricultural Economics in Transition II. Available online: http://oro.open.ac.uk/2683/ (accessed on 12 April 2021).

- Holtorf, Cornelius. 2018. Embracing change: How cultural resilience is increased through cultural heritage. World Archaeology 50: 639–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrymak, Oleh Y., Myroslava V. Vovk, and Olena V. Kindrat. 2019. Agrotourism as one of the ways to develop entrepreneurship in rural areas. Scientific Messenger of LNU of Veterinary Medicine and Biotechnologies 21: 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Beiming, Furong He, and Lingshan Hu. 2022. Community Empowerment Under Powerful Government: A Sustainable Tourism Development Path for Cultural Heritage Sites. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Yunfeng, Zhipeng Zhang, Junsheng Fei, and Xiang Chen. 2023. Optimization Strategies of Commercial Layout of Traditional Villages Based on Space Syntax and Space Resistance Model: A Case Study of Anhui Longchuan Village in China. Buildings 13: 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indonesia. 2014. Undang-Undang Republik Indonesia No. 6 Tahun 2014 Tentang Desa. Available online: https://peraturan.bpk.go.id/Home/Details/38582/uu-no-6-tahun-2014 (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- Jaunis, Orryel, Andy R. Mojiol, and Julius Kodoh. 2022. Agrotourism in Malaysia: A Review on Concept, Development, Challenges and Benefits. Transactions on Science and Technology 9: 77–85. Available online: https://tost.unise.org/pdfs/vol9/no2/ToST-9x2x77-85xRA.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- Jin, Chenghua, Misuzu Takao, and Masahiro Yabuta. 2022. Impact of Japan’s local community power on green tourism. Asia-Pacific Journal of Regional Science 6: 571–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junaidi, Junaidi, Amril Amril, and Riski Hernando. 2022. Economic coping strategies and food security in poor rural households. Agricultural and Resource Economics: International Scientific E-Journal 8: 30–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junaidi, Junaidi, Yulmardi Yulmardi, and Hardiani Hardiani. 2020. Food crops-based and horticulture-based villages potential as growth center villages in Jambi Province, Indonesia. Journal of Critical Reviews 7: 514–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachniewska, Magdalena A. 2015. Tourism development as a determinant of quality of life in rural areas. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes 7: 500–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharishvili, Eter, Tamar Lazariashvili, and La Natsvlishvili. 2019. Agro tourism for economic development of related sectors and sustainable well-being (case of Georgia). Paper presented at 6th Business Systems Laboratory International Symposium, Pavia, Italy, January 21–23. [Google Scholar]

- Kolawole, Oluwatoyin D., Wame L. Hambira, and Reniko Gondo. 2023. Agrotourism as peripheral and ultraperipheral community livelihoods diversification strategy: Insights from the Okavango Delta, Botswana. Journal of Arid Environments 212: 104960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubickova, Marketa, and Jeffrey M. Campbell. 2020. The role of government in agro-tourism development: A top-down bottom-up approach. Current Issues in Tourism 23: 587–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Suneel, and Shekhar Shekar. 2020. Technology and innovation: Changing concept of rural tourism—A systematic review. Open Geosciences 12: 737–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunáková, Lucia, Róbert Štefko, and Radovan Bačík. 2016. Evaluation of the landscape potential for recreation and tourism on the example of microregion Mincol (Slovakia). E-Review of Tourism Research 13: 335–54. [Google Scholar]

- Kusumastut, Ratih I., and Mukhzarudfa Mukhzarudfa. 2018. Jambi ecotourism development model: Reviewed from budget and performance commitment. CELSciTech towards Downstream and Commercialization of Research 3: 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- Lak, Azadeh, and Omid Khairabadi. 2022. Leveraging Agritourism in Rural Areas in Developing Countries: The Case of Iran. Frontiers in Sustainable Cities 4: 863385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Jung W., and Ahmad M. Syah. 2018. Economic and Environmental Impacts of Mass Tourism on Regional Tourism Destinations in Indonesia. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business 5: 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengkong, Meilany R., I Made Antara, and I Ketut S. Diarta. 2018. Pengembangan Agrowisata Berbasis Masyarakat Di Kelurahan Rurukan Dan Rurukan I Kecamatan Tomohon Timur Provinsi Sulawesi Utara. Jurnal Manajemen Agiribisnis 6: 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, Ee, and Siew H. C. Ong. 2018. Understanding the attributes that motivates tourists’ choice towards agritourism destination in Cameron. Qualitative and Quantitative Research Review 3: 39–60. [Google Scholar]

- Linnenluecke, Martina K., Andrew Griffiths, and Monika I. Winn. 2013. Firm and industry adaptation to climate change: A review of climate adaptation studies in the business and management field. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 4: 397–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madanaguli, Arun, Puneet Kaur, Alberto Mazzoleni, and Amandeep Dhir. 2022. The innovation ecosystem in rural tourism and hospitality—A systematic review of innovation in rural tourism. Journal of Knowledge Management 26: 1732–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkanthi, S. H. Pushpa, and Jayant K. Routry. 2011. Potential for agritourism development: Evedance from Sri Lanka. Journal of Agricultural Sciences 6: 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, Norsida, and Hafiza A. H. Aspany. 2020. Agrotourism Preferences Factors Among Urban Dwellers In Klang Valley Area. Malaysian Journal of Agricultural Economics 29: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manaf, Asnawi, Novia Purbasari, Maya Damayanti, Nanda Aprilia, and Winny Astuti. 2018. Community-Based Rural Tourism in Inter-Organizational Collaboration: How Does It Work Sustainably? Lessons Learned from Nglanggeran Tourism Village, Gunungkidul Regency, Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Sustainability 10: 2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansor, Norudin, Kartini M. Rashid, Zuraida Mohamad, and Zalinawati Abdullah. 2015. Agro tourism potential in Malaysia. International Academic Research Journal of Business and Technology 1: 37–44. Available online: https://www.pustaka-sarawak.com/eknowbase/attachments/1623476213.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- McGehee, Nancy G., and Kyungmi Kim. 2004. Motivation for Agri-Tourism Entrepreneurship. Journal of Travel Research 43: 161–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moise, George, Agatha Popescu, Iulian A. Bratu, Ion Răducuță, Bogdan G. Nistoreanu, and Mirela Stanciu. 2023. Can We Talk about Smart Tourist Villages in Mărginimea Sibiului, Romania? Sustainability 15: 7475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mura, Ladislav, and Aleksandr Ključnikov. 2018. Small Businesses in Rural Tourism and Agrotourism: Study from Slovakia. Economics and Sociology 11: 286–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtadho, Alfin, Andrea E. Pravitasari, Khursatul Munibah, and Ernan Rustiadi. 2020. Spatial Distribution Pattern of Village Development Index in Karawang Regency Using Spatial Autocorrelation Approach. Jurnal Pembangunan Wilayah dan Kota 16: 102–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nana, Lili A. 2020. Arah Pengembangan Potensi Agrowisata Untuk Penguatan Ekonomi Lokal Di Kampung Kuriman Panorama Baru Kota Bukittinggi. Ph.D. thesis, Universitas Andalas, West Sumatra, Indonesia. Available online: http://scholar.unand.ac.id/63669/ (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Nastiti, Amanda P., Luchman Hakim, and Soemarno Soemarno. 2019. Community Participation in Agro-tourism Development at Karangsari, Blitar, East Java. Journal of Environmental Engineering and Sustainable Technology 6: 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson, Norma P., Rita J. Black, and Stephen F. McCool. 2001. Agritourism: Motivations behind Farm/Ranch Business Diversification. Journal of Travel Research 40: 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeidat, Bushra, and Amani Hamadneh. 2022. Agritourism-A Sustainable Approach to the Development of Rural Settlements in Jordan: Al-Baqura Village as a Case Study. International Journal of Sustainable Development and Planning 17: 669–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohe, Yasuo, and Shinichi Kurihara. 2013. Evaluating the complementary relationship between local brand farm products and rural tourism: Evidence from Japan. Tourism Management 35: 278–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamungkas, Bambang A. 2019. Pelaksanaan Otonomi Desa Pasca Undang-Undang Nomor 6 Tahun 2014 Tentang Desa. Jurnal USM Law Review 2: 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, Marko D., Ivana Blešić, Aleksandra Vujko, and Tamara Gajić. 2017. The Role of Agritourism’s Impact on the Local Community in a Transitional Society: A Report From Serbia. Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences 2017: 146–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, Mark S. 2008. Stakeholder participation for environmental management: A literature review. Biological Conservation 141: 2417–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocharungsat, Pimrawee. 2008. Community-based tourism in Asia. In Building Community Capacity for Tourism Development. Houston: CABI, pp. 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, Geraldo. S., Clayton Campanhola, Isis Rodrigues, Rosa T. S. Frighetto, Pedro J. Valarini, and Luiz O. R. Filho. 2006. Environmental management of rural activities: Case studies on agrotourism and organic agriculture. Agricultura Em São Paulo 53: 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Roman, Michal, Monika Roman, and Piotr Prus. 2020. Innovations in agritourism: Evidence from a region in Poland. Sustainability 12: 4858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosalina, Putu D., Karine Dupre, and Ying Wang. 2021. Rural tourism: A systematic literature review on definitions and challenges. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 47: 134–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roslina, Roslina, Rita Nurmalina, Mukhamad Najib, and Yudha H. Asnawi. 2022. Government Policies on Agro-Tourism in Indonesia. WSEAS Transactions on Business and Economics 19: 141–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustiadi, Ernan, Andrea E. Pravitasari, Rista A. Priatama, Jane Singer, Junaidi Junaidi, Zugani Zulgani, and Rizqi I. Sholihah. 2023. Regional Development, Rural Transformation, and Land Use/Cover Changes in a Fast-Growing Oil Palm Region: The Case of Jambi Province, Indonesia. Land 12: 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustiadi, Ernan, Baba Barus, Laode S. Iman, Setyardi P. Mulya, Andrea E. Pravitasari, and Dedy Antony. 2018a. Land Use and Spatial Policy Conflicts in a Rich-Biodiversity Rain Forest Region: The Case of Jambi Province, Indonesia. Singapore: Springer Nature, pp. 277–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustiadi, Ernan, Sunsun Saefulhakim, Dyah R. Panuju, and Andrea E. Pravitasari. 2018b. Perencanaan dan Pengembangan Wilayah. Jakarta: Yayasan Pustaka Obor Indonesia. [Google Scholar]

- Saadah, Maratun, Mohammad N. Sampoerno, Zuhri Triansyah, and Fransisko Chaniago. 2021. Pengembangan Pengelolaan Pariwisata oleh Badan Usaha Milik Desa di Jambi. KAMBOTI: Jurnal Sosial Dan Humaniora 1: 182–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraswati, Ety, Aleria I. Hatneny, and Andi N. Dewi. 2020. Implementasi Model Diamond Porter Dalam Membangun Keunggulan Bersaing Pada Kawasan Agrowisata Kebun Belimbing Ngringinrejo Bojonegoro. Jurnal Ilmu Manajemen (JIMMU) 4: 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, Brian, Kevin Sullivan, and Stephen Komar. 2012. Examining the Economic Benefits of Agritourism: The Case of New Jersey. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development 3: 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipatau, Jemmy A., Jabil Mapjabil, and Ubong Imang. 2020. Diversity Of Rural Tourism Products and Challenges of Rural Tourism Development in Kota Marudu, Sabah. Journal of Islamic, Social, Economics and Development 5: 51–61. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Hongmei, Chris Zhu, and Lawrence H. N. Fong. 2021. Exploring Residents’ Perceptions and Attitudes towards Sustainable Tourism Development in Traditional Villages: The Lens of Stakeholder Theory. Sustainability 13: 13032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srisomyong, Niorn, and Dorothea Meyer. 2015. Political economy of agritourism initiatives in Thailand. Journal of Rural Studies 41: 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strielkowski, Wadim. 2017. Promoting Tourism Destination through Film-Induced Tourism: The Case of Japan. Market-Tržište 29: 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymanska, Elzbieta. 2022. Problems of Tourist Mobility in Remote Areas of Natural Value—The Case of the Hajnowka Poviat in Poland and the Zaoneshye Region in Russia. Economies 10: 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabash, Mosab I., Suhaib Anagreh, Bilal H. Subhani, Mamdouh A. S. Al-Faryan, and Krzysztof Drachal. 2023. Tourism, Remittances, and Foreign Investment as Determinants of Economic Growth: Empirical Evidence from Selected Asian Economies. Economies 11: 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamburini, Giovanni, Riccardo Bommarco, Thomas C. Wanger, Claire Kremen, Marcel G. A. van der Heijden, Matt Liebman, and Sara Hallin. 2020. Agricultural diversification promotes multiple ecosystem services without compromising yield. Science Advances 6: eaba1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tew, Christine, and Carla Barbieri. 2012. The perceived benefits of agritourism: The provider’s perspective. Tourism Management 33: 215–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonny, Judiantono, and Wulan Putri. 2020. Determining priority infrastructure provision for supporting agrotourism development using AHP method. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 830: 022036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vengesayi, Sebastian, Felix T. Mavondo, and Yvette Reisinger. 2009. Tourism Destination Attractiveness: Attractions, Facilities, and People as Predictors. Tourism Analysis 14: 621–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vovk, Iryna, and Yuriy Vovk. 2017. Development of family leisure activities in the hotel and restaurant businesses: Psychological and pedagogical aspects of animation activity. Economics, Management and Sustainability 2: 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vysochan, Oleh, Natalia Stanasiuk, Mykhailo Honchar, Vasyl Hyk, Natalia Lytvynenko, and Olha Vysochan. 2022. Comparative Bibliometric Analysis of the Concepts of “Ecotourism” and “Agrotourism” in the Context of Sustainable Development Economy. Journal of Environmental Management and Tourism 13: 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahyuni, Rahma, and Syamsir Syamsir. 2021. Local Government’s Integrity and Strategy in Tourism Development Based on Creative Economy in Kerinci Regency. Paper presented at 1st Tidar International Conference on Advancing Local Wisdom towards Global Megatrends, TIC 2020, Magelang, Jawa Tengah, Indonesia, October 21–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widi, Shilvina. 2022. Pendapatan Devisa Pariwisata Indonesia Melejit Pada 2022. Available online: https://dataindonesia.id/sektor-riil/detail/pendapatan-devisa-pariwisata-indonesia-melejit-pada-2022 (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- Wilonoyudho, Saratri. 2017. Urbanization and Regional Imbalances in Indonesia. Indonesian Journal of Geography 49: 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Lishan, Changlin Ao, Baoqi Liu, and Zhenyu Cai. 2023. Ecotourism and sustainable development: A scientometric review of global research trends. Environment, Development and Sustainability 25: 2977–3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Li. 2012. Impacts and Challenges in Agritourism Development in Yunnan, China. Tourism Planning and Development 9: 369–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaitul, Zaitul, Desi Ilona, and Nova Novianti. 2022. Village-Based Tourism Performance: Tourist Satisfaction and Revisit Intention. Polish Journal of Sport and Tourism 29: 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhe, Xiaoye, and Yun Ai. 2020. Urban–Rural Relationship in the Flow of Factors. In Institutional Logics and Practice of the Evolution of Urban–Rural Relationships. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 111–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuriati, Lily, and Sri Mariya. 2020. Potensi Perkembangan Agrowisata Di Kabupaten Kerinci. Jurnal Buana 4: 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hierarchy | Tanjung Lanjut | Kuala Lagan | Renah Alai | Mekarsari | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nature tourism potential | Nature tourism potential | Nature tourism potential | Nature tourism potential | Nature tourism potential |

| 2 | Agro-products | Heritage | Heritage | Agro-products | Agro-products |

| 3 | Heritage | Agro-products | Agro-products | Heritage | Heritage |

| 4 | Community and Institution | Infrastructure | Infrastructure | Infrastructure | Infrastructure |

| 5 | Infrastructure | Community and Institution | Community and Institution | Community and Institution | Community and Institution |

| 6 | Technology Innovation | Technology Innovation | Technology Innovation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zulgani, Z.; Junaidi, J.; Hastuti, D.; Rustiadi, E.; Pravitasari, A.E.; Asfahani, F.R. Understanding the Emergence of Rural Agrotourism: A Study of Influential Factors in Jambi Province, Indonesia. Economies 2023, 11, 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies11070180

Zulgani Z, Junaidi J, Hastuti D, Rustiadi E, Pravitasari AE, Asfahani FR. Understanding the Emergence of Rural Agrotourism: A Study of Influential Factors in Jambi Province, Indonesia. Economies. 2023; 11(7):180. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies11070180

Chicago/Turabian StyleZulgani, Zulgani, Junaidi Junaidi, Dwi Hastuti, Ernan Rustiadi, Andrea Emma Pravitasari, and Fadwa Rhogib Asfahani. 2023. "Understanding the Emergence of Rural Agrotourism: A Study of Influential Factors in Jambi Province, Indonesia" Economies 11, no. 7: 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies11070180

APA StyleZulgani, Z., Junaidi, J., Hastuti, D., Rustiadi, E., Pravitasari, A. E., & Asfahani, F. R. (2023). Understanding the Emergence of Rural Agrotourism: A Study of Influential Factors in Jambi Province, Indonesia. Economies, 11(7), 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies11070180