Abstract

Using microdata from Statistics Canada’s Labour Force Survey (LFS) and Population Census, this paper explores how spatial characteristics are correlated with temporary employment outcomes for Canada’s immigrant population. Results from ordinary least square regression models suggest that census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations (CMAs/CAs) characterized by a high share of racialized immigrants, immigrants in low-income, young, aged immigrants, unemployed immigrants, and immigrants employed in health and service occupations were positively associated with an increase in temporary employment for immigrants. Furthermore, findings from principal component regression models revealed that a combination of spatial characteristics, namely CMAs/CAs characterized by both a high share of unemployed immigrants and immigrants in poverty, had a greater likelihood of immigrants being employed temporarily. The significance of this study lies in the spatial conceptualization of temporary employment for immigrants that could better inform spatially targeted employment policies, especially in the wake of the structural shift in the nature of work brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic.

1. Introduction

Canada’s labour market has undergone a series of shifts since the second post world war era (Vosko 2011). One trend that reflects this is the growth of non-standard employment, including temporary employment that is characterized by labour market insecurity (compared with full-time, permanent employment) (Statistics Canada 2019; Vosko 2003). During the past 20 years, temporary employment outpaced permanent employment (Statistics Canada 2019). Data from Statistics Canada’s Labour Force Survey (LFS) further reveals that in 1998 there were 1.4 million workers (11.8%) employed temporarily compared with 2.1 million (13.3%) in 2018 (Statistics Canada 2019). Comparatively, across OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) economies, the share of workers employed temporarily in Canada was slightly lower than that of the OECD average in 2021 (12.4% vs. 12.8%, respectively) (OECD 2021).

Within the broader framework of precarious employment studies, several authors have conceptualized non-standard employment in differing ways (Krahn 1995; Polivka 1996; Vosko et al. 2003). Krahn’s (1995) definition of non-standard employment encompasses a range of employment forms that deviate from the Standard Employment Relationship (SER) model (i.e., full-time permanent employment). These forms of employment include temporary employment, part-time employment, self-employment, and employment in multiple jobs (Krahn 1995). Other studies, namely Vosko et al. (2003) and Polivka (1996), adopt a more restricted definition of non-standard employment. Vosko et al. (2003) include temporary and part-time employment and exclude self-employment and employment in multiple jobs, whilst Polivka (1996) excludes part-time employment and only includes temporary employment. Polivka’s (1996) inclusion of temporary employment is based on the notion that temporary work arrangements lack attachment between workers and employers. This is not the case for most part-time work arrangements. In this paper, we conceptually focus on temporary employment based on Polivka’s (1996) restricted definition as a considerable share of workers who are employed temporarily lack some form of attachment with their employers. Typically, temporary employment arrangements are equated with less employment security, lower wages, fewer benefits, less possibility of unionization, and chances of upward mobility (relative to permanent full-time employment) (Statistics Canada 2019; Vosko et al. 2003).

Concerning the relationship between temporary employment and social locations, women, immigrants, and racialized populations have been noted to be disproportionately employed in temporary wage work and other insecure forms of employment compared with their respective counterparts (Ali et al. 2020; Ali and Newbold 2021a, 2021b; Fuller and Vosko 2008). Fuller and Vosko (2008, p. 33) argue that temporary employment in Canada has been tied to gender, race, and immigration statuses of populations when they write, “patterns of economic restructuring are often shaped by prevailing gendered and racialized divisions and the spread of temporary employment in Canada in the 1990s echoed such historic tendencies insofar as it was promoted among women and recent immigrants in particular”. As such, we focus on immigrants as the study’s main population unit of analysis, since the demographic composition of this group appears likely to shape temporary employment outcomes in Canada (Ali and Newbold 2020; Fuller and Vosko 2008).

On another note, the spatial dimension of temporary employment by social groups (specifically immigrants) is an imperative focus for both national and comparative research that has received less attention in the literature (MacDonald 2009). MacDonald (2009, p. 211) broadly underscores the importance of spatially aware conceptualizations in the study of precarious employment when stating that “precariousness is created not just by specific job characteristics but by the spatial contexts in which such work occurs. Precarious employment affects individuals in particular locations and is shaped by spatial dynamics”. More so, “the spatial dimension is part of the dynamic that creates and maintains precarious employment and determines its distribution”.

Despite the dearth of studies examining the intersections of migration, space and temporary employment in Canada, some advancements in the literature have been made. This includes studies theorizing spatial arrangements of broader labour market outcomes (see MacDonald 2009; Taylor et al. 2019). Other studies, including Ali and Newbold (2021a) and Jacquemond and Breau (2015), investigated the spatial dimensions of precarious employment (including temporary employment) but did not consider immigrants as the main population unit of analysis.

In this article, we examine how temporary employment for immigrant populations in Canada is correlated with a range of spatial characteristics. In doing so, we capture the salience of how temporary wage work for immigrants is spatially constituted. By and large, the findings of this paper can have significant implications for policy and planning by informing place-based policies that negate negative employment outcomes for immigrants.

2. Literature Review

Numerous studies situated within the Canadian context have established that immigrants (relative to their Canadian-born counterparts) are more likely to be employed in temporary wage work that is characterized by a high degree of insecurity, low pay, little to no benefits, and, in some cases, does not appropriate with their education credentials (Ali and Newbold 2020; Hira-Friesen 2018; Noack and Vosko 2011; Vosko et al. 2003). Racialized immigrants are also disproportionately overrepresented in temporary employment types such as seasonal, contract, casual, and other forms of non-standard employment (Ali and Newbold 2021a; Lamb et al. 2021; Stecy-Hildebrandt et al. 2019). The non-recognition of foreign credentials, lack of local experience, discrimination, and language and cultural differences (that make networking difficult) has significantly impacted the ability of racialized immigrants to access the Canadian labour market with ease (Teelucksingh and Galabuzi 2007).

A plethora of studies in the literature has depicted the broader labour market disadvantage faced by immigrants relative to their Canadian-born counterparts (Agyekum 2016; Ali and Newbold 2020; Bauder 2003a, 2003b; Reitz 2007). They include low returns for immigrants’ foreign educational credentials (Aydede and Dar 2017; Ferrer and Riddell 2004; Reitz 2007), a decline in immigrant entry earnings across cohorts (Green and Worswick 2012; Picot et al. 2016), and deskilling in the Canadian labour market, i.e., the mismatch between education and skills (Creese and Wiebe 2012; Ertorer et al. 2022; Wilkinson et al. 2016; Man 2004). As it pertains to the trends in temporary employment for Canada’s immigrant population, Noack and Vosko (2011) find that recent immigrants have a higher likelihood of being employed in temporary work than their Canadian-born counterparts. Key findings in their study also revealed that one in ten employees is a recent immigrant (9.8%), yet recent immigrants make up 15.9% of temporary, part-time employees. Other studies examining the social stratification of the Canadian labour market by race and immigration establish that racialized immigrants encounter high levels of unemployment, underemployment, and lower income levels than their non-racialized immigrant counterparts (Akbar 2019; Agyekum et al. 2021; Mensah and Williams 2022). In accordance with these findings, this study hypothesizes the following: CMA/CAs characterized by high shares of racialized immigrants are associated with a greater likelihood of immigrants being employed temporarily (hypothesis 1) and CMA/CAs characterized by high shares of low-income increases the likelihood of immigrants working in temporary settings (hypothesis 2).

Some studies have offered a series of explanations as to why immigrants in Canada are relegated to insecure non-standard employment arrangements. Bauder (2001, 2003a, 2003b) and Creese and Wiebe (2012) assert that the devaluation of immigrant labour into non-standard work arrangements is associated with the workings of cultural capital in society. Creese and Wiebe (2012) argue that forms of cultural capital that are relevant to the integration of immigrants into the labour market include embodied cultural capital (immigrant accents and other local cultural competencies) and institutionalized cultural capital (immigrant academic credentials). Creese and Wiebe (2012) further maintain that the non-recognition of immigrants’ credentials by employers in conjunction with the absence of forms of embodied cultural capital (including accents, cultural knowledge, or work experience) contributes to their deskilling in the Canadian labour market (Creese and Wiebe 2012). Bauder (2003a) echoes Creese and Wiebe’s (2012) assertions by suggesting that the devaluation of immigrant labour could also be correlated in some way with one’s habitus in society. Bauder (2005) interrogates this further in his examination of the obstacles associated with workplace conventions and hiring practices (encountered by immigrants) in the context of Bourdieu’s theory of habitus. Bauder (2005) puts forth the argument that immigrants may be unfamiliar with the norms and conventions of the hiring processes in the Canadian marketplace or unable to judge employers’ expectations. As such, some studies have shown that immigrants are apt to use temporary employment agencies as a stepping-stone to negate the challenges of matching to domestic market rules (Fuller and Stecy-Hildebrandt 2015), while others have shown no evidence of a stepping-stone effect (Hveem 2013).

From a policy lens, reducing labour market inequalities for immigrants is a key policy priority for the Canadian government, with both language training and acceptance of foreign credentials being specific priorities (Agyekum 2020; Tamtik 2017; Trilokekar and El Masri 2017). The need for a focus on the promotion of equity in labour market participation has been recognized and it is on the agenda in several policy areas beyond that of health, including social justice, social inclusion, education, etc. (Li et al. 2017; Mahomed 2020). In Canada, several policy responses have been put forth, among others, legislative responses such as equal opportunity and employment equity; workplace-based initiatives such as inclusive workplace and diversity management, and broader public policy instruments including education, training, and job creation (Abella 2014; McGowan and Ng 2016). However, the potential for spatially targeted (place-based) policies in negating negative labour market outcomes in Canada has not been well documented in the literature. As such, the adoption of a spatial lens in this study has the potential to inform spatially disaggregated employment policies geared towards reducing labour market inequality for immigrants.

From the literature we have established the growing trend of temporary employment in Canada, the channels facilitating this growth, and the populations at risk of being employed in this type of wage work. Nevertheless, the examination of how spatial characteristics are correlated with temporary employment outcomes for immigrants has received less attention. MacDonald (2009) affirms that there is a need for more empirical and conceptual studies to explore how spatial conceptualization can be considered in the study of labour market insecurity. MacDonald (2009) proclaims that non-standard work arrangements are essentially created by the spatial contexts in which such work occurs and shaped by spatial dynamics (and not only by job-specific characteristics). Within the literature, the few studies that pay attention to the spatial dimensions of non-standard employment do not focus on immigrants as the population unit of analysis. Ali and Newbold’s (2021a) study situated in Canada, for instance, finds that the labour market (prevalence in low income) and size characteristics of Canada’s census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations (CMAs/CAs) were positively associated with temporary employment. Their study further confirms that temporary employment outcomes in Canada have an inherent spatial dimension (Ali and Newbold 2021a). Other studies beyond the Canadian context indicate that non-standard forms of employment are inevitably shaped by a suite of spatial factors. Jacquemond and Breau’s (2015) study, for example, finds that regions in France with a high percentage of populations employed in the secondary sector of the economy were associated with a higher likelihood of temporary employment. Similar findings are expected in the current study, as we expect CMA/CAs characterized by a high share of immigrants employed in service occupations (within the secondary sector) to be positively associated with an increase in temporary employment for immigrants (hypothesis 3). Analysis of other economic variables in their study further shows that regions in France with high unemployment rates were also associated with a greater likelihood of temporary employment (Jacquemond and Breau 2015). This finding is supported by other studies that establish regions with high proportions of non-standard employment are likely to have high unemployment rates, lower rates of unionization, and lower average wages (Ali and Newbold 2021a; Çitçi and Begen 2019; MacDonald 2009; Ruokonen and Makisalo 2018). Following these findings, we hypothesize that CMA/CAs characterized by a high share of unemployed immigrants are positively associated with an increase in temporary employment for immigrants (hypothesis 4). We further hypothesize that CMAs/CAs characterized by both a high share of unemployed immigrants and immigrants in poverty will have a greater likelihood of immigrants being employed temporarily (hypothesis 5).

The overall aim of this paper is to examine how spatial characteristics are correlated with temporary employment outcomes for Canada’s immigrant population within census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations (CMAs/CAs). The spatial unit of analysis in this paper is CMAs/Cas, as the paper focuses only on large, populated areas. The significance of this study lies in the empirical quantification of the broader spatial characteristics that are correlated with temporary labour market outcomes for immigrants in Canada, the findings of which could better inform decision-making when formulating spatially targeted labour market policies.

3. Methods

3.1. Data and Sample

Data used in this study were pooled from the 2016 microdata Labour Force Survey (LFS) and the 2016 Census of population survey conducted and compiled by Statistics Canada. The LFS provides monthly, nationwide estimates of the labour force status of Canada’s population. A suite of socio-economic, socio-demographic and geographic population characteristics supplements each sample. The target population of the LFS includes household residents who are 15 years of age or older. Exemptions include populations in aboriginal reserves, remote areas, institutions, and Canadian Forces bases. The Census, on the other hand, provides a detailed statistical portrait of Canada’s population by geographic region and demographic, social, and economic characteristics. This survey enumerates the entire Canadian population, consisting of Canadian citizens, landed immigrants and non-permanent residents and their families living in Canada. The Census also enumerates Canadian citizens and landed immigrants who are temporarily living outside Canada on census day. Both the LFS and the Census follow a cross-sectional survey design.

For the Census, one in four households (25%) received a long-form questionnaire (via systematic sampling, selected from the Census of Population dwelling list). All other households received a short-form census questionnaire, therefore, no sampling was done. The Census long-form covers the same target population as the short-form census, except for populations in institutional and non-institutional collective dwellings, Canadian Forces bases and Canadian citizens temporarily living abroad. Alternatively, the LFS sample size typically includes 100,000 individuals representing 56,000 households. This survey follows a rotating panel sample design, with data collected from the same subsample for six consecutive months, with each month consisting of six sub-samples. In any given month, the survey drops 1 sub-sample after completing its six months stay in the survey. A new sub-sample is then drawn to replace the dropped respondents. To ensure that the samples in the LFS do not overlap, January and July samples were focused on, thus ensuring that the two months are within separate rotating panels and have unique household identifications. The study sample used in this study was then restricted to include Canada’s population who are 25–64 years of age in both the Labour Force Survey (LFS) and the Census survey. Furthermore, the spatial unit of analysis was restricted to only include CMAs/CAs.

3.2. Method of Analysis

The analysis focused on the use of Ordinary least square (OLS) and principal component regression (PCR) models using SAS 9.4. OLS regression models are used to provide insights into the correlation of individual spatial characteristics on temporary employment for immigrants assuming the remaining explanatory variables are kept constant. The general equation for the OLS regression is given as follows:

where yk denotes the value of a continuous response variable for observation k, xik, (i = 1, 2, 3, … p, k = 1, 2, 3, … n) are the values of p explanatory variables for the same observation; and εk is the random error that is assumed to be normally distributed with zero mean and constant variance σ2.

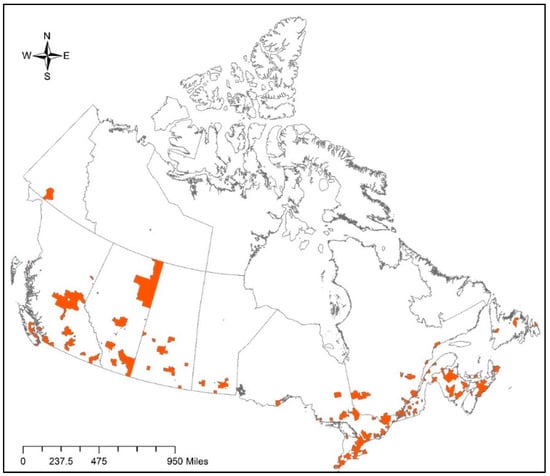

However, in ideal situations these (spatial) explanatory variables work concurrently, thus, a PCR is used to estimate the joint effects (interrelationships) among spatial characteristics for immigrant populations on temporary employment. PCR serves the same technique as a linear regression with the only difference being that PCR uses principal components as a predictor. The explanatory spatial characteristics used in the regression models are informed by both empirical and theoretical underpinnings in the literature (see Table 1). The percentage of immigrants employed in temporary employment (dependent variable) is calculated for each of the 83 CMA/CAs. Moreover, the percentage of immigrants that make up a specific spatial characteristic is also calculated for each of the 83 CMA/CAs (independent variable). Figure 1 shows a map of the CMA/CAs in Canada.

Table 1.

The rationale for explanatory variables.

Figure 1.

Census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations across Canada’s landscape.

All independent variables (except for geographic mobility status and EI beneficiaries) are defined for the immigrant population. While the LFS and Census lists a total of 152 CMA/CAs only 83 CMA/CAs met the disclosure requirements of Statistics Canada for the dependent variable. Further, due to disclosure limitations within smaller spatial scales, we were limited in examining the spatial effects of individual subclassifications of temporary employment (seasonal, contract and casual employment) for immigrants. As such, we combined all subtypes of temporary employment into one unified form of temporary employment and calculated the portion of immigrants in temporary employment for both dependent and independent variables. Both dependent and independent variables are continuous. Table 1 identifies and defines the dependent variable and provides a rationale for the various proposed independent variables. All explanatory variables in the final model had a Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) less than 10 indicating no presence of multicollinearity. Table 2 lists the abbreviation and description of all explanatory variables.

Table 2.

Abbreviation and description of variables.

4. Results

4.1. Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) Regression Results

Table 3 presents the results of the OLS regression model examining the effects of individual spatial (CMA/CA) characteristics and temporary employment outcomes for immigrants. Overall, the fit of the model was statistically significant (p < 0.0001). The coefficient of determination (r-square) further suggests that the model explained 95.4% of the total variation in temporary employment.

Table 3.

OLS regression model exploring the relationship between spatial (CMA/CA) characteristics and temporary employment outcomes among immigrant populations.

With respect to socio-demographic spatial characteristics, we found that CMA/CAs characterized by an older share of immigrants (35–44 and 45–54 years of age) were significant and simultaneously negatively associated with temporary employment for immigrants. On the other hand, CMA/CAs with a higher share of young immigrants (25–34 years of age) were significantly positively associated with an increase in temporary employment for immigrants (β = 0.01, p = 0.0033). Further examination of the immigrant population by race showed that CMA/CAs that are characterized by a high portion of racialized immigrants were positively associated with an increase in immigrants employed temporarily (β = 0.02, p = 0.0635). This result however did not hold for the immigrant variable as a whole i.e., racialized and non-racialized (β = −0.04, p = 0.0086). On mobility status, our results showed that an increase in the share of migrants within CMA/CAs was positively associated with immigrants employed temporarily (β = 0.05, p = 0.0003). This was also the case for CMA/CAs with a high share of non-migrants, but to a lesser degree (β = 0.03, p = 0.0005).

Moving to socio-economic spatial characteristics, the results in Table 3 reveal an insignificant positive association between the deviation of the mean wage for immigrant workers from the minimum wage within CMA/CAs and immigrants employed temporarily (β = 0.02, p = 0.1877). Concurrently, an increase in the share of CMA/CAs with a high portion of immigrants in low income resulted in a higher likelihood of temporary work for immigrants, holding other factors constant (β = 0.14, p = 0.0423). Likewise, CMA/CAs characterized by high unemployment rates for both immigrants and racialized immigrants had coefficients that were positive and highly significant in estimation for temporary employment for immigrants. (β = 0.10, p = 0.0375 and β = 0.40; p = 0.0220, respectively).

Concerning occupation, we find several mixed results. Specifically, CMA/CAs characterized by a larger portion of immigrants employed in specific occupations, namely the natural and applied sciences had a significant positive relationship with temporary work held by immigrants (β = 0.17, p = 0.0211). Counter to this, we found a significant negative relationship between immigrants employed in temporary work and the share of immigrants within CMA/CAs employed in the following occupations: business, finance, and administration occupations, education, law, and social, community and government services, occupations in manufacturing and utilities. On the other hand, CMA/CAs characterized by a high share of immigrants employed in the health, sales and services occupations were positively associated with temporary employment for immigrants, although their relationship to temporary employment occupied by immigrants was insignificant. Finally, CMA/CAs with a high share of populations receiving employment insurance were found to be negatively associated with temporary work for immigrants (β = −0.06, p = 0.0285).

4.2. Principal Component Regression (PCR) Results

We now turn to the PCA (Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6) and PCR analyses (Table 7) that model the interrelationships (joint effects) among spatial characteristics for immigrant populations on temporary employment. Table 4 presents 1. the initial component eigenvalues, 2. the percent of variance accounted for, and 3. the cumulative variance accounted for in the PCA analysis. We can see that in the initial extraction process, the PCA retains as many components as the individual indicators (explanatory variables in this case). While the first principal component explains 18.47% of the variation with the maximum variance (eigenvalue of 4.62). The second principal component explains 15.29% of the variation with the maximum amount of the remaining variance of 3.8215. Continuing in this sequential order, we observe that the first 8 PCs explain about 81.22% of the total variation, while the last seventeen principal components explain the remaining 18.78% of the variance in the data set.

Table 4.

Eigenvalues for the correlation matrix.

Table 5.

Rotated factor pattern.

Table 6.

Component variances due to VR rotation (Squared Component Loading).

Table 7.

PCR exploring the joint effects among spatial (CMA/CA) characteristics on temporary employment for immigrants.

The first eight components (explaining 81.22% of the total variation) are retained following Cattell’s (1966), and Kaiser’s (1960) selection criteria. Cattell (1966) proposes the use of a graphical “scree plot” to be used to determine the optimal number of components to retain. The basic idea behind the scree plot involves plotting the eigenvalues with their order of magnitude and finding a point where the line joining the eigenvalues smoothly decreases and flattens out (point of inflection) to the right of the plot. After examining the “scree plot’ only eight components were retained for the analysis. One of the shortcomings of the “scree plot” method is that the ‘levelling off’ of eigenvalues on the Scree plot is subjective. As such for validation purposes, we used Kaiser’s (1960) criterion, which stipulates that only components with an eigenvalue of 1.0 or more are retained. Using this criterion, we similarly retained only 8 components.

Table 5 presents the PCA analysis using varimax rotation to assess how the spatial (CMA/CA) characteristics clustered in each component. Table 6 further shows the total variance explained due to the varimax rotation. The eight retained components cumulatively explain 81.22% of the total variance in the data. The labels of the principal components in the PCR regression are further labelled in accordance with variables that highly loaded in each respective component (see Table 5 below).

Table 7 below presents the results of the principal component regression examining the relationship between a combination of spatial (CMA/CAs) characteristics and temporary employment occupied by immigrants. Holding other factors constant, an increase in CMA/CAs with a high portion of unemployed immigrants and immigrants in low income significantly resulted in a higher level of temporary employment for immigrants (β = 2.20, p = 0.0001). The second principal component explained by CMA/CAs with a high portion of immigrants, populations receiving EI beneficiaries and immigrants employed in business, finance and administration occupations was negatively associated with temporary employment for immigrants (β = −0.61, p = 0.2339). This could be explained by the offset in the high loading in % employment insurance beneficiaries that includes persons who have been without work in off-season temporary jobs. Similarly, CMA/CAs with a high share of non-unionized immigrants and immigrants occupying manufacturing and trades occupations were (significantly) also negatively associated with temporary employment for immigrants (β = −0.87, p = 0.0907).

CMA/CAs that are characterized by a highly mobile population, immigrants in the arts occupation, and immigrants in low income were found to be positively associated with temporary employment for immigrants (β = 0.398, p = 0.4452). This positive association also held for CMA/CAs with a high portion of immigrants aged 25–44 and immigrants in natural and applied sciences and related occupations. We also found that CMA/CAs characterized by a high share of immigrants employed in the management and sales and service occupations to be statistically significant and positively associated with immigrants employed temporarily (β = 1.40, p = 0.0084). Conversely, an increase in CMA/CAs characterized by larger portions of non-unionized immigrants and immigrants occupying manufacturing and trades occupations, significantly decreased temporary employment outcomes for immigrants, holding other factors constant (β = −0.87, p = 0.090).

5. Discussion

This paper sought to understand how spatial characteristics are correlated with temporary employment outcomes for immigrants. We first examined the effects of individual spatial characteristics for immigrant populations on temporary employment assuming the remaining explanatory variables are kept constant. The results from Table 3 suggest that CMA/CAs characterized by a larger share of younger immigrants were positively associated with temporary employment for immigrants. This finding is corroborated by Ali and Newbold’s (2020) study that investigated the geographic variations of precarious employment outcomes between immigrant and Canadian-born populations. Their results showed that young immigrants (aged 25–34) are more likely to be employed in temporary wage work (compared with older immigrants). From the onset, most young immigrants face multiple difficulties in matching the Canadian labour market rules as new labour market entrants (Oreopoulos 2011) with foreign credentials and limited Canadian work experience (Gribble and McRae 2017; Noack and Vosko 2011).

Further stratification of the immigrant population, by race in Table 3, showed that CMA/CAs with a high share of racialized immigrants and racialized immigrants in low-income were both associated with a greater likelihood of temporary employment. These results support both hypotheses 1 and 2. Our findings are further corroborated by several studies that look beyond spatial effects to point to the growing racialization of poverty (within industrialized economies), with key findings indicating that racialized populations continue to encounter higher levels of unemployment, underemployment, and lower-income levels than their non-racialized counterparts (Agyekum 2020; Block et al. 2014; Liu 2019). Temporal data dating back from 1996–2001 also substantiate our findings as racialized and immigrant populations (compared to non-racialized groups) are found to not have fared well in their labour market positions as they are overrepresented precarious employment in low-wage occupations and continue to sustain a double-digit income gap despite contributing to a much higher rate of new entrants to the Canadian labour force (Teelucksingh and Galabuzi 2007).

From the results in Table 3, it is expected that CMA/CAs with a high share of immigrants (racialized and non-racialized) would be positively associated with temporary employment. However, our findings contradict this popular assumption. This may be due to offset by the large fraction of non-racialized immigrants who have a higher likelihood of employment in standard forms of employment (or less precarious non-standard employment) similar to their Canadian-born counterparts. This finding further reinforces the role of race in shaping temporary employment outcomes. Fuller and Vosko’s (2008) study echoes this sentiment by revealing that race and migration together increase the probability of employment in various types of temporary employment in Canada. Other studies within the Canadian context show similar findings when using earning differentials (between racialized and non-racialized groups) as an indicator of economic well-being (Pendakur and Pendakur 1998). Pendakur and Pendakur’s (1998) findings for instance report no substantial earning penalty among white immigrants from Northern and Central Europe, whilst racialized immigrants faced earning penalties ranging from 1% (Chinese immigrants) to 22.2 % (Black immigrants).

Turning again to Table 3, the results show that CMA/CAs characterized by a high share of immigrants employed in service occupations were positively associated with an increase in temporary employment for immigrants. This finding support hypothesis 3 and is corroborated by Ali and Newbold’s (2021a) study that showed a positive association between CMA/CAs characterized by high shares of sales and service occupations and temporary employment outcomes. Ali and Newbold’s (2021a) study, however, did not consider immigrants as the study’s main population unit of analysis. Other studies beyond the Canadian context including Jacquemond and Breau’s (2015) find that regions in France with a high percentage of populations employed in the secondary sector of the economy were associated with a higher likelihood of temporary employment. Taken together, this study together with Ali and Newbold’s (2021a) and Jacquemond and Breau’s (2015) studies affirm that temporary employment outcomes are inevitably shaped by the concentration of occupations within census metropolitan and agglomeration areas.

Findings on spatial characteristics such as the unemployment rate reveal that CMA/CAs with a high share of unemployed racialized immigrants (relative to the aggregate unemployed immigrant population) are significantly and greatly associated with temporary work for immigrants, further supporting hypothesis 4. Within the literature, It is insisted that regions with high unemployment rates are likely to have a high concentration of non-standard employment, an absolute shortage of jobs, lower rates of unionization and lower average wages (Ali and Newbold 2021a; Biegert 2017; MacDonald 2009). Previous research has also found that regions with a high share of temporary wage workers and unemployed populations experience periods of economic instability as workers are less likely to receive Employment Insurance (EI) benefits because of short employment durations and low hours worked (Biegert 2017). The individual effects in Table 3 are further reinforced when looking into joint effects in Table 7. These results support hypothesis 5 as we find that CMA/CAs with a high share of unemployed immigrants and immigrants with low income were significantly associated with immigrants employed temporarily.

Concerning geographic mobility, our findings are similarly reported to generalized findings in the literature as CMA/CA’s with a high share of migrants and non-migrants (Table 3) were significantly associated with immigrants employed temporarily. MacDonald (2009) and Walsh et al. (2014) argue that the maintenance of non-standard employment in poor/disadvantaged geographical regions is associated with labour immobility of workers that provide a captive labour force for non-standard employment. They further affirm that the immobility of workers may be related to residential patterns (in an urban context), or household gender dynamics. Migrants, as (somehow) expressed by patterns of geographic labour mobility, may also be a factor fuelling the labour supply of non-standard workers because of policies related to international migration, the housing market, social policies, unemployment insurance, and transportation (Walsh et al. 2014). The findings in Table 3 on geographic mobility are corroborated by the joint effects in Table 7 as an increase in CMA/CAs with a highly mobile population, immigrants in the arts occupation and immigrants in low-income were associated with an increased likelihood of temporary employment for immigrants.

6. Limitations and Policy Implications

One of the weaknesses encountered in this study was the incapacity to explore the effects of spatial characteristics for varied types of temporary employment held by immigrants (e.g., seasonal, contract and casual employment) due to data disclosure limitations, especially at the CMA/CA scale. As such, we treated temporary employment as homogeneous to meet the vetting requirements of Statistics Canada. We acknowledge that immigrants may experience different levels of insecurity within different types of temporary employment as highlighted by Fuller and Vosko (2008).

Beyond these limitations, the findings of this paper have significant policy implications, as they encourage policymakers to focus beyond job-specific characteristics or institutional contexts and consider the broader spatial attributes that influence immigrants’ temporary employment outcomes when formulating policies that negate employment inequality for immigrants. Such policies are imperative to revitalize the social and economic features of geographies that are associated with key spatial attributes that influence immigrant precarity. Such an undertaking is vital as the immigrant and racialized populations continue to be relegated to low-paying, non-standard jobs despite their contribution to Canada’s growing labour market. To put the aforementioned statement into perspective, census data shows that international migratory increases could account for more than 80% of Canada’s population growth beginning in 2031 (Statistics Canada 2018a). Furthermore by 2031, 47% of the second generation (the Canadian-born children of immigrants) will belong to a racialized group, nearly double the proportion of 24% in 2006 (Statistics Canada 2018b). Therefore, if racialized and immigrant populations continue to be relegated to non-standard forms of employment the Canadian economy will lose out and not reap the full potential benefits of these growing populations (Agyekum 2020; Block et al. 2014). This concern is further expressed by a report by the conference board of Canada that estimates underemployment costing immigrants up to $12.7 billion in lost wages (El-Assal and Fields 2017). As a direct consequence, the performance of the Canadian economy or the geographies where disadvantaged groups work and live could suffer through lower tax revenue, lost productivity, and reduced purchasing power for immigrants (El-Assal and Fields 2017).

7. Conclusions

This paper has demonstrated the degree to which spatial characteristics are correlated with temporary employment outcomes for Canada’s immigrant population. We have presented a suite of spatial characteristics that affect labour market demand for immigrants, such as the types of work available in tertiary occupations, geographic mobility, as well as those affecting labour market supply including unemployment rate, poverty (measured by low-income cut-offs), temporary income support, and racial/immigrant divides, were correlated with temporary work for immigrants. We further demonstrated the joint effects among macro-level spatial characteristics for immigrants and their association with immigrants employed temporarily. Specifically, we showed that a combination of spatial attributes, namely, high unemployment rates and poverty significantly resulted in an increase in temporary employment for immigrants. These findings add valuable empirical insights into the way temporary employment for immigrants is fashioned by macro-level spatial characteristics that ultimately influence the casual bases of the labour market demand and supply in non-standard employment settings.

Concerning future work, more studies adopting spatially aware conceptualizations of non-standard employment are needed. For instance, future studies could consider comparing the effects of peri-urban spatial characteristics on temporary work or any other form of non-standard work occupied by immigrants. We base this on spatial assimilation theories, which suggest that immigrants first settle in large metropolitan areas where of people from the same ethnic backgrounds reside. As they stay longer, they tend to move to the peri-urban or suburban areas. Finally, the interrogation of seasonal work occupied by immigrants in rural areas could be an area of interest for future work. Taken together, these proposed future works that are grounded in spatially aware conceptualizations are imperative in furthering our understanding of non-standard employment in Canada.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.A.; methodology W.A.; validation, W.A. and B.A.; formal analysis, W.A.; investigation, W.A.; writing—original draft preparation, W.A.; writing—review and editing, B.A., N.A.N., A.A. and S.C.; visualization, W.A. and B.A.; supervision, W.A.; project administration, W.A. and B.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Access to confidential microdata files used in this study was obtained through the Statistics Canada Research Data Centre (RDC) program. Interested researchers can contact the corresponding author for details on obtaining access to the confidential microdata files used in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abella, Justice Rosalie Silberman. 2014. Employment Equity in Canada: The Legacy of the Abella Report. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Agyekum, Boadi. 2016. Labour market perceptions and experiences among Ghanaian–Canadian second-generation youths in the Greater Toronto Area. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift–Norwegian Journal of Geography 70: 112–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyekum, Boadi. 2020. Neighbourhood characteristics and the labour market experience. Canadian Journal of Urban Research 29: 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Agyekum, Boadi, Pius Siakwah, and John Kwame Boateng. 2021. Immigration, education, sense of community and mental well-being: The case of visible minority immigrants in Canada. Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability 14: 222–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, Marshia. 2019. Examining the factors that affect the employment status of racialized immigrants: A study of Bangladeshi immigrants in Toronto, Canada. South Asian Diaspora 11: 67–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Waad K., and K. Bruce Newbold. 2020. Geographic variations in precarious employment outcomes between immigrant and Canadian-born populations. Papers in Regional Science 99: 1185–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Waad K., and K. Bruce Newbold. 2021a. The spatial dimensions of temporary employment in Canada. The Canadian Geographer 65: 215–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Waad K., and K. Bruce Newbold. 2021b. Gender, space, and precarious employment in Canada. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 112: 566–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Waad K., K. Bruce Newbold, and Suzanne E. Mills. 2020. The Geographies of Precarious Labour in Canada. Canadian Journal of Regional Science 43: 58–70. [Google Scholar]

- Aydede, Yigit, and Atul Dar. 2017. Is the lower return to immigrants’ foreign schooling a postarrival problem in Canada? IZA Journal of Migration 6: 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauder, Harald. 2001. Culture in the Labor Market: Segmentation Theory and Perspectives of Place. Progress in Human Geography 25: 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauder, Harald. 2003a. “Brain Abuse”, or the Devaluation of Immigrant Labour in Canada. Antipode 35: 699–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauder, Harald. 2003b. Cultural Representations of Immigrant Workers by Service Providers and Employers. Journal of International Migration and Integration 4: 415–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauder, Harald. 2005. Habitus, Rules of the Labour Market and Employment Strategies of Immigrants in Vancouver, Canada. Social and Cultural Geography 6: 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biegert, Thomas. 2017. Welfare benefits and unemployment in affluent democracies: The moderating role of the institutional insider/outsider divide. American Sociological Review 82: 1037–64. [Google Scholar]

- Block, Sheila, Grace-Edward Galabuzi, and Alexandra Weiss. 2014. The Colour-Coded Labour Market by the Numbers. Toronto: The Wellesley Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Labour Congress. 2016. Diving without a Parachute: Young Canadians versus a Precarious Economy. Ottawa: Canadian Labour Congress. [Google Scholar]

- Cattell, Raymond B. 1966. The scree test for the number of factors. Multivariate Behavioral Research 1: 245–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çitçi, Sadettin Haluk, and Nazire Begen. 2019. Macroeconomic conditions at workforce entry and job satisfaction. International Journal of Manpower 40: 879–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creese, Gillian, and Brandy Wiebe. 2012. ‘Survival employment’: Gender and deskilling among African immigrants in Canada. International Migration 50: 56–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckelt, Marcus, and Guido Schmidt. 2014. Learning to be precarious—The transition of young people from school into precarious work in Germany. Journal for Critical Education Policy Studies (JCEPS) 12: 130. [Google Scholar]

- El-Assal, Kareem, and Daniel Fields. 2017. 450,000 Immigrants Annually? Integration Is Imperative to Growth. Ottawa: The Conference Board of Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Ertorer, Secil E., Jennifer Long, Melissa Fellin, and Victoria M. Esses. 2022. Immigrant perceptions of integration in the Canadian workplace. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal 41: 1091–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, Ana, and W. Craig Riddell. 2004. Education, Credentials and Immigrant Earnings. Vancouver: University of British Columbia, Department of Economics. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, Sylvia, and Leah F. Vosko. 2008. Temporary employment and social inequality in Canada: Exploring intersections of gender, race and immigration status. Social Indicators Research 88: 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, Sylvia, and Natasha Stecy-Hildebrandt. 2015. Career pathways for temporary workers: Exploring heterogeneous mobility dynamics with sequence analysis. Social Science Research 50: 76–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, David A., and Christopher Worswick. 2012. Immigrant earnings profiles in the presence of human capital investment: Measuring cohort and macro effects. Labour Economics 19: 241–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gribble, Cate, and Norah McRae. 2017. Creating a climate for global WIL: Barriers to participation and strategies for enhancing international students’ involvement in WIL in Canada and Australia. In Professional Learning in the Workplace for International Students. Cham: Springer, pp. 35–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hira-Friesen, Parvinder. 2018. Immigrants and precarious work in Canada: Trends, 2006–2012. Journal of International Migration and Integration 19: 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hveem, Joakim. 2013. Are temporary work agencies stepping stones into regular employment? IZA Journal of Migration 2: 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquemond, Marc, and Sébastien Breau. 2015. A spatial analysis of precarious forms of employment in France. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 106: 536–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonna, R. Jamil, and John Bellamy Foster. 2016. Marx’s theory of working-class precariousness: Its relevance today. Monthly Review 67: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, Henry F. 1960. The Application of Electronic Computers to Factor Analysis. Educational and Psychological Measurement 20: 141–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalleberg, Arne L., and Steven P. Vallas. 2018. Probing precarious work: Theory, research, and politics. Research in the Sociology of Work 31: 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Kapsalis, Constantine, and Pierre Tourigny. 2004. Duration of non-standard employment. Perspectives on Labour and Income (Statistics Canada, 75-001-XPE) 5: 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Krahn, Harvey. 1995. Non-standard work on the rise. Perspectives on Labour and Income 7: 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb, Danielle, Rupa Banerjee, and Anil Verma. 2021. Immigrant–non-immigrant wage differentials in Canada: A comparison between standard and non-standard jobs. International Migration 59: 113–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Ian W., Stephane Mahuteau, Alfred M. Dockery, and Pramod N. Junankar. 2017. Equity in higher education and graduate labour market outcomes in Australia. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 39: 625–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Jingzhou. 2019. The precarious nature of work in the context of Canadian immigration: An intersectional analysis. Canadian Ethnic Studies 51: 169–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, Martha. 2009. Spatial dimensions in gendered precariousness. In Gender and the Contours of Precarious Employment. Edited by Leah F. Vosko, Martha MacDonald and Iain Campbell. London: Routledge, pp. 211–25. [Google Scholar]

- Mahomed, Nisaar. 2020. Transforming education and training in the post-apartheid period: Revisiting the education, training and labour market axis. In The State, Education and Equity in Post-Apartheid South Africa. London: Routledge, pp. 105–38. [Google Scholar]

- Man, Guida. 2004. Gender, work and migration: Deskilling Chinese immigrant women in Canada. In Women’s Studies International Forum. Oxford: Pergamon, vol. 27, pp. 135–48. [Google Scholar]

- McGowan, Rosemary A., and Eddy S. Ng. 2016. Employment equity in Canada: Making sense of employee discourses of misunderstanding, resistance, and support. Canadian Public Administration 59: 310–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, Joseph, and Christopher J. Williams. 2022. Socio-structural injustice, racism, and the COVID-19 pandemic: A precarious entanglement among Black immigrants in Canada. Studies in Social Justice 16: 123–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noack, Andrea M., and Leah F. Vosko. 2011. Insecurity by Workers’ Social Location and Context. In Precarious Jobs in Ontario: Mapping Dimensions of Labour Market Insecurity by Workers’ Social Location and Context. Toronto: Law Commission of Ontario. Available online: http://www.lco-cdo.org/en/vulnerable-workers-call-for-papers-noack-vosko (accessed on 3 January 2023).

- OECD. 2021. OECD Data: Temporary Employment. Available online: https://data.oecd.org/emp/temporary-employment.htm (accessed on 3 January 2023).

- Oreopoulos, Philip. 2011. Why do skilled immigrants struggle in the labor market? A field experiment with thirteen thousand resumes. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 3: 148–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peck, Jamie. 1996. Workplace: The Social Regulation of Labor Markets. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pendakur, Krishna, and Ravi Pendakur. 1998. The Colour of Money: Earnings Differentials Among Ethnic Groups in Canada. Canadian Journal of Economics 31: 518–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picot, Garnett, Feng Hou, and Hanqing Qiu. 2016. The human capital model of selection and immigrant economic outcomes. International Migration 54: 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piper, Nicola, and Matt Withers. 2018. Forced transnationalism and temporary labour migration: Implications for understanding migrant rights. Identities 25: 558–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polivka, Anne E. 1996. Contingent and alternative work arrangements, defined. Monthly Labor Review 119: 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Poverty and Employment Precarity in Southern Ontario (PEPSO). 2015. The Precarity Penalty: The Impact of Employment Precarity on Individuals, Households and Communities and What to Do about It. Available online: https://pepsouwt.files.wordpress.com/2012/12/precarity-penalty-report_final-hires_trimmed.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2023).

- Reitz, Jeffrey G. 2007. Immigrant Employment Success in Canada, Part II: Understanding the decline. Journal of International Migration and Integration 8: 37–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruokonen, Minna, and Jukka Makisalo. 2018. Middling-status profession, high-status work: Finnish translators’ status perceptions in the light of their backgrounds, working conditions and job satisfaction. Translation & Interpreting, The 10: 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. 2018a. Population Growth: Migratory Increase Overtakes Natural Increase. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-630-x/11-630-x2014001-eng.htm (accessed on 3 January 2023).

- Statistics Canada. 2018b. Ethnic Diversity and Immigration. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-402-x/2011000/chap/imm/imm-eng.htm (accessed on 3 January 2023).

- Statistics Canada. 2019. Temporary Employment in Canada. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/190514/dq190514b-eng.htm (accessed on 3 January 2023).

- Statistics Canada. 2021. Visible Minority of Person. Available online: https://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p3Var.pl?Function=DEC&Id=45152 (accessed on 3 January 2023).

- Stecy-Hildebrandt, Natasha, Sylvia Fuller, and Alisyn Burns. 2019. ‘Bad’jobs in a ‘Good’sector: Examining the employment outcomes of temporary work in the Canadian public sector. Work, Employment and Society 33: 560–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamtik, Merli. 2017. Who governs the internationalization of higher education? A comparative analysis of macro-regional policies in Canada and the European Union. Comparative and International Education 46: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Tiffany, Brianna Turgeon, Alison Buck, Katrina Bloch, and Jacob Church. 2019. Spatial Variation in U.S. Labor Markets and Workplace Gender Segregation: 1980–2005. Sociological Inquiry 89: 703–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teelucksingh, Cheryl, and Grace-Edward Galabuzi. 2007. Working Precariously: The Impact of Race and Immigrant Status on Employment Opportunities and Outcomes in CANADA. In Race and Racialization: Essential Readings. Edited by Tania Das Gupta, Carl E. James, Roger C. A. Maaka, Grace-Edward Galabuzi and Chris Andersen. Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press, pp. 202–8. [Google Scholar]

- Trilokekar, Roopa Desai, and Amira El Masri. 2017. The ‘[h] unt for new Canadians begins in the classroom’: The construction and contradictions of Canadian policy discourse on international education. Globalisation, Societies and Education 15: 666–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vosko, Leah F. 2003. Gender differentiation and the standard/non-standard employment distinction in Canada, 1945 to the Present. In Social Differentiation in Canada. Edited by Danielle Juteau. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 25–80. [Google Scholar]

- Vosko, Leah F. 2011. Precarious employment and the problem of SER-centrism in regulating for decent work. In Regulating for Decent Work. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 58–90. [Google Scholar]

- Vosko, Leah F., Nancy Zukewich, and Cynthia Cranford. 2003. Precarious jobs: A new typology of employment. Perspectives on Labour and Income 4: 16–26. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, Walsh, Leah F. Vosko, Martha MacDonald, Katherine Laxer, Sylvia Fuller, and Sandra Ignagni. 2014. Conceptual Guide to the Temporal and Spatial Dynamics Module. Available online: http://www.genderwork.ca/cpd/modules/temporal-spatial-dynamics/ (accessed on 3 January 2023).

- Wilkinson, Lori, Pallabi Bhattacharyya, Jill Bucklaschuk, Jack Shen, Iqbal A. Chowdhury, and Tamara Edkins. 2016. Understanding job status decline among newcomers to Canada. Canadian Ethnic Studies 48: 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).