Economic Policy Uncertainty, Energy and Sustainable Cryptocurrencies: Investigating Dynamic Connectedness during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Related Studies

3. Methodology

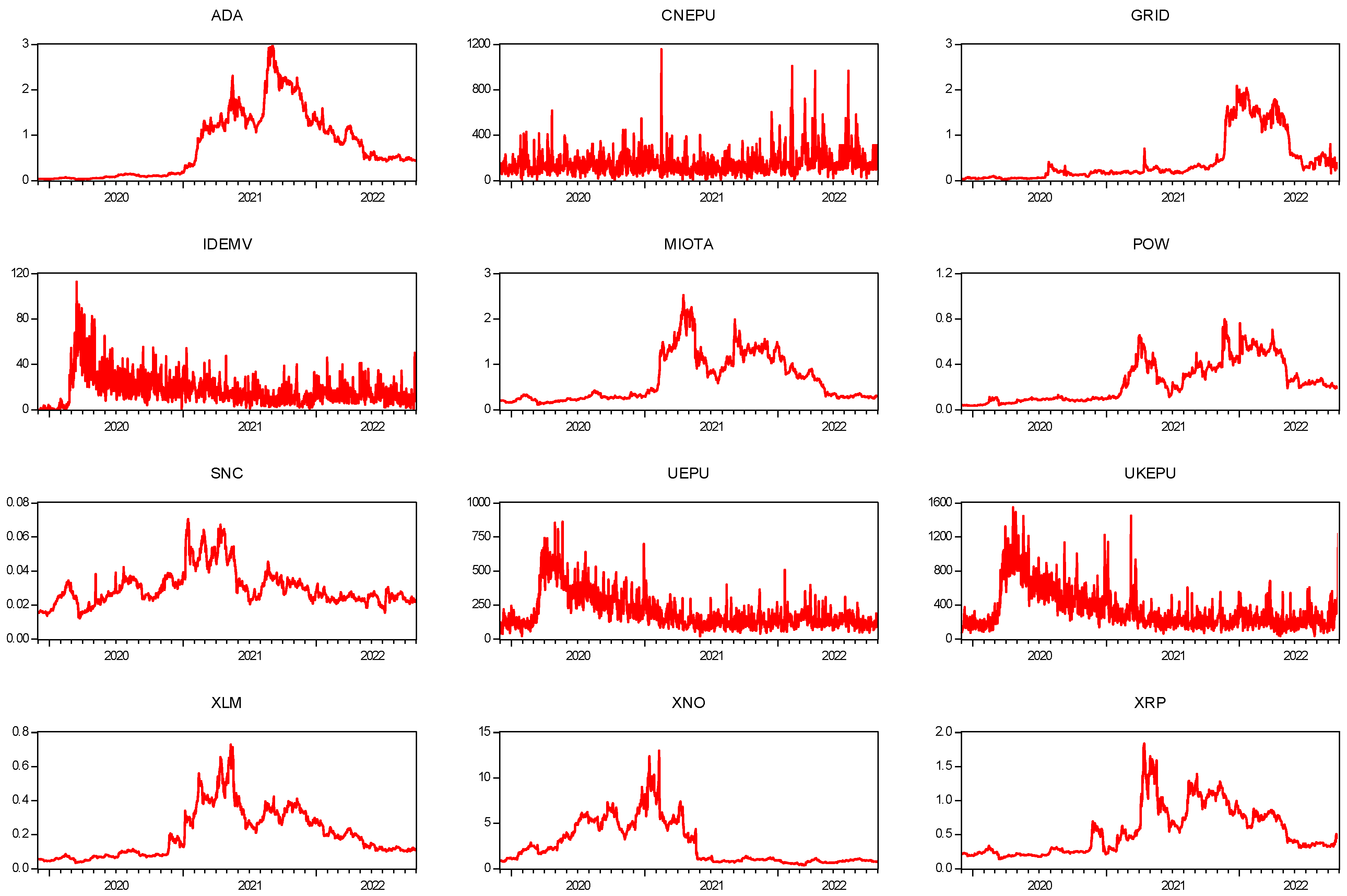

3.1. Data

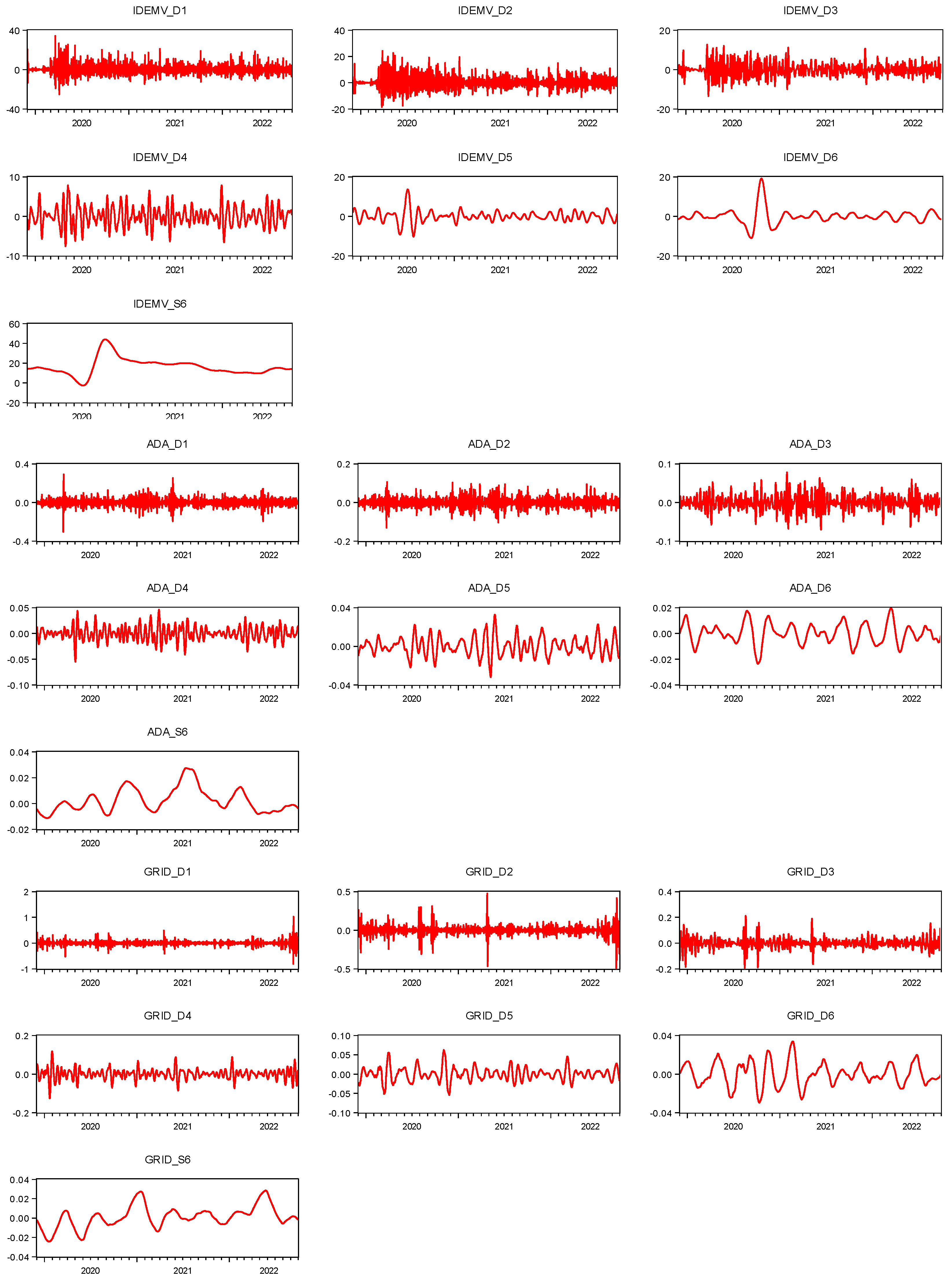

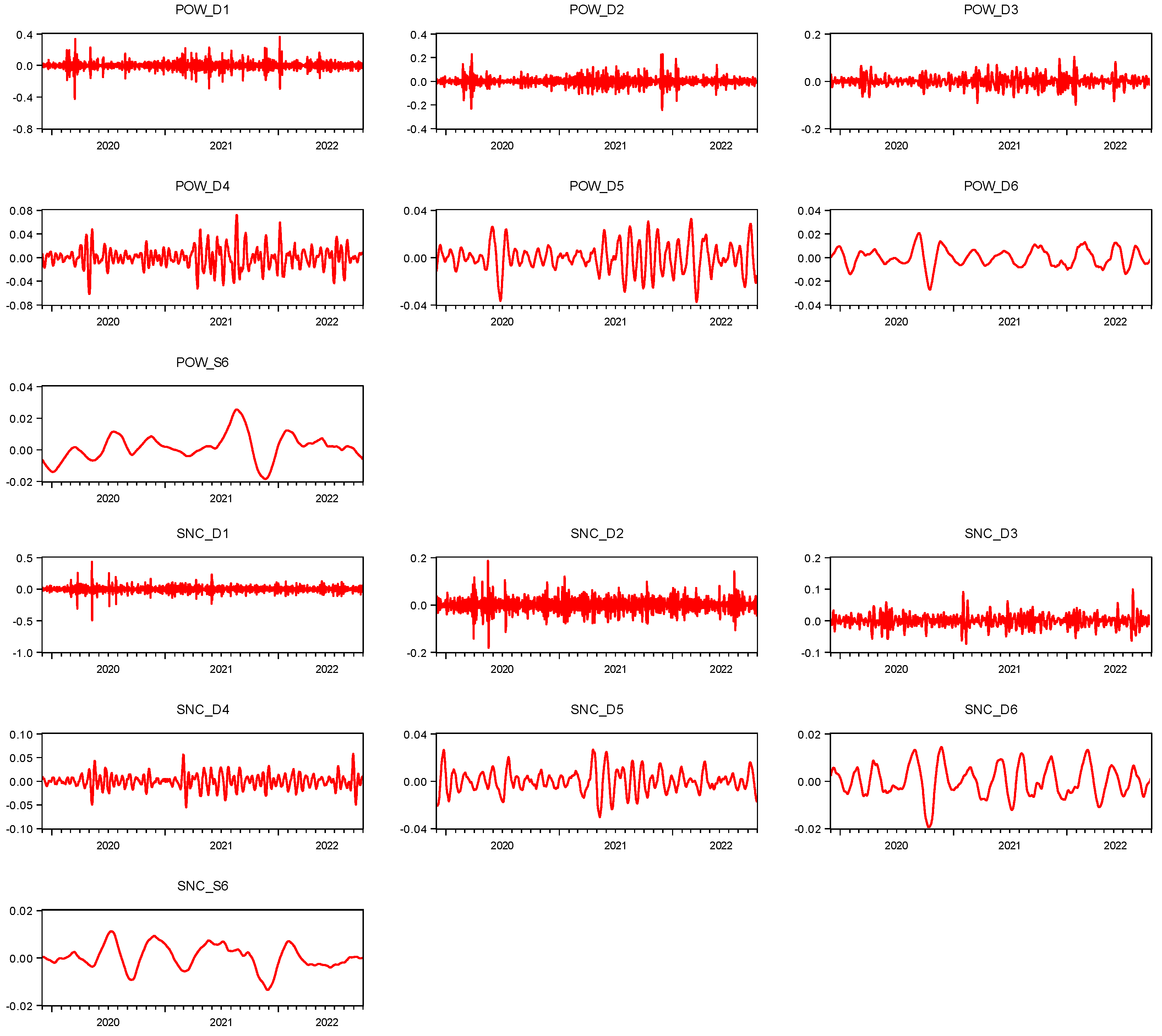

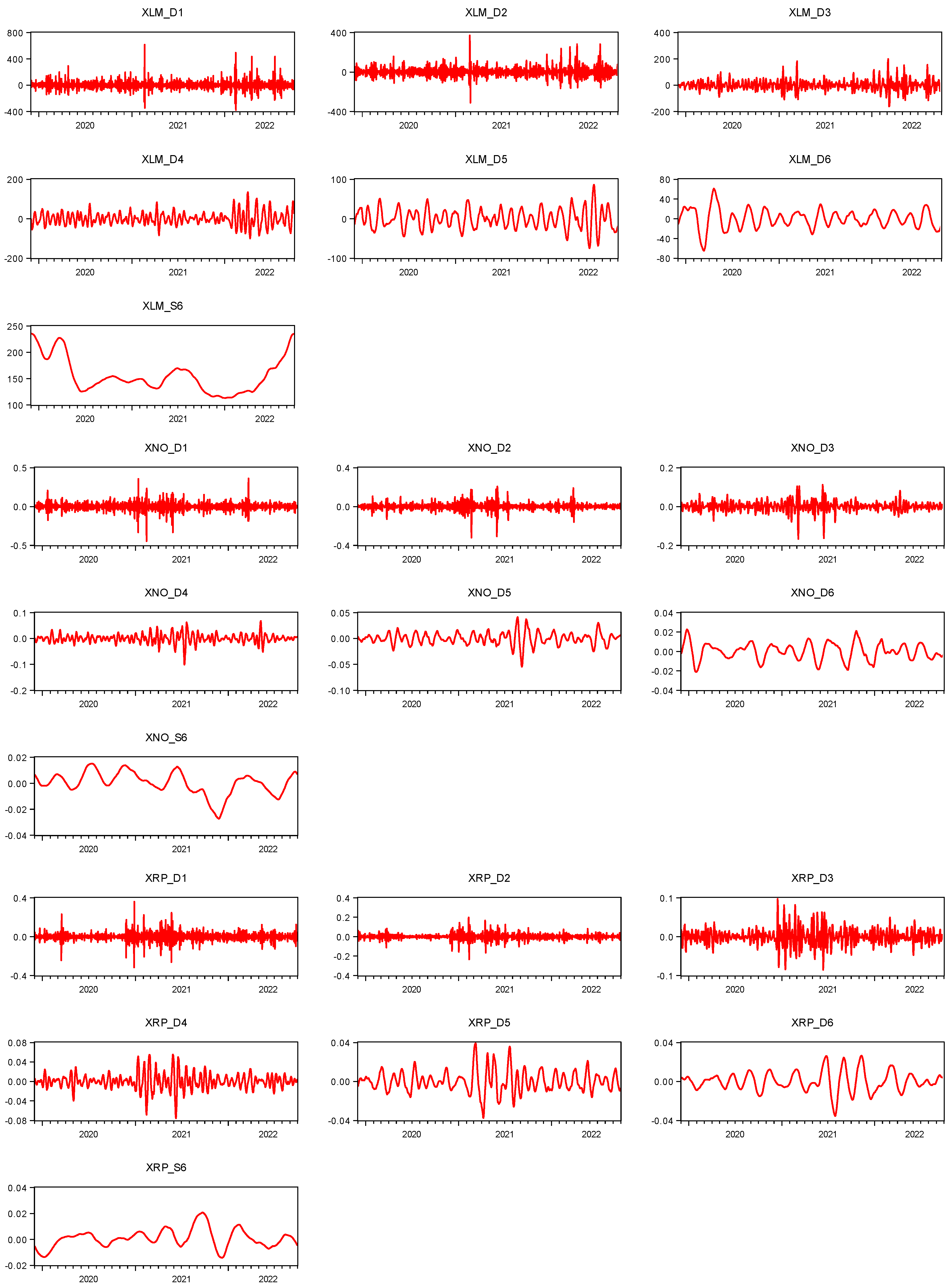

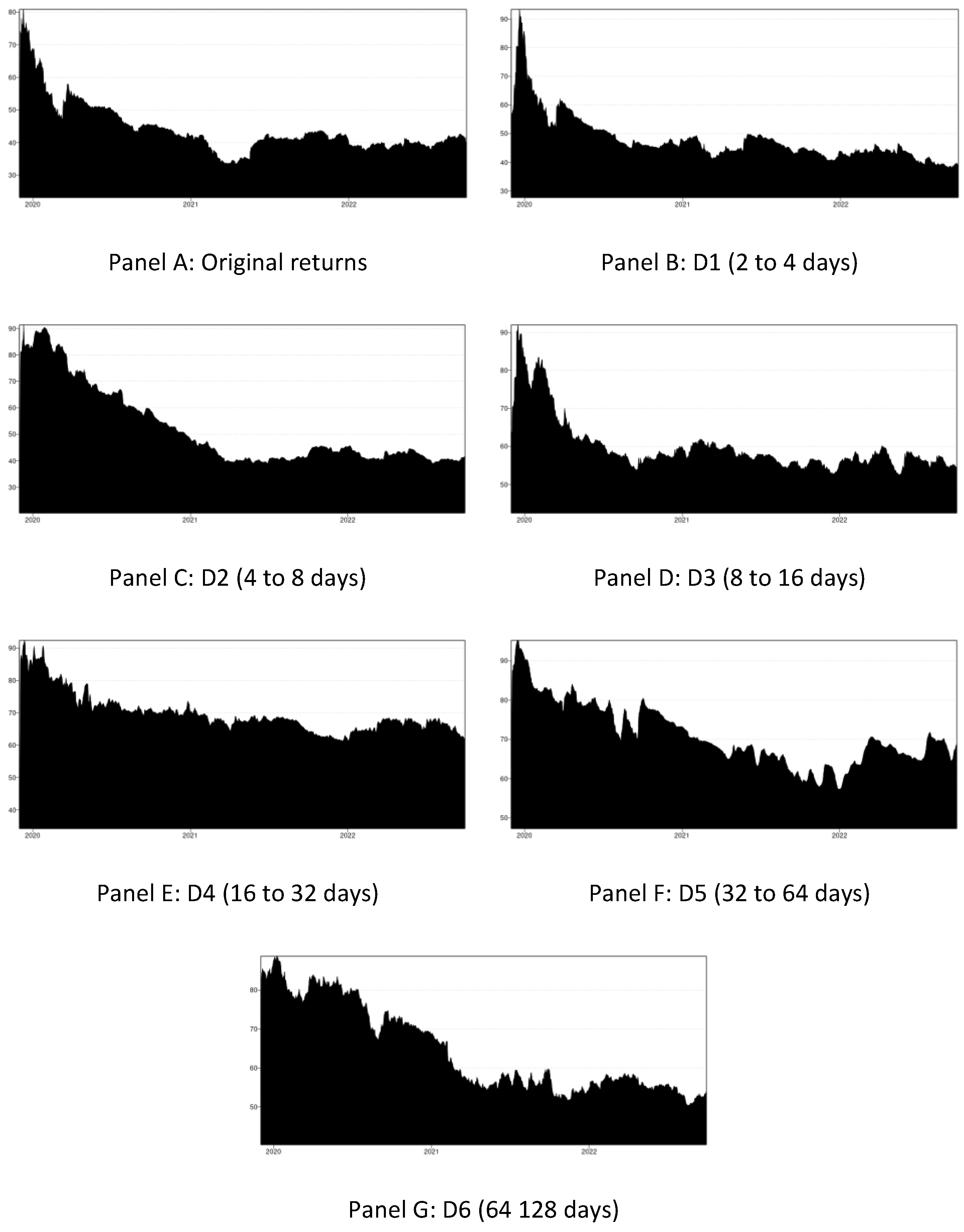

3.2. Maximum Overlap Discrete Wavelet Transform Method

3.3. TVP-VAR Approach

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Summary Statistics

4.2. Evidence from TVP-VAR Approach

5. Conclusions and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Adekoya, Oluwasegun, and Johnson Oliyide. 2021. How COVID-19 drives connectedness among commodity and financial markets: Evidence from TVP-VAR and causality-in-quantiles techniques. Resources Policy 70: 101898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ah Mand, Abdollah. 2021. Cryptocurrency Returns and Cryptocurrency Uncertainty: A Time-Frequency Analysis. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3950087 (accessed on 25 October 2022).

- Al-Thaqeb, Saud, and Barrak Algharabali. 2019. Economic policy uncertainty: A literature review. The Journal of Economic Asymmetries 20: e00133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Yahyaee, Khamis, Mobeen Rehman, Walid Mensi, and Idries Al-Jarrah. 2019. Can uncertainty indices predict Bitcoin prices? A revisited analysis using partial and multivariate wavelet approaches. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance 49: 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonakakis, Nikolaos, Ioannis Chatziantoniou, and David Gabauer. 2020. Refined Measures of Dynamic Connectedness based on Time-Varying Parameter Vector Autoregressions. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 13: 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Scott, Nicholas Bloom, and Steven Davis. 2016. Measuring economic policy uncertainty. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 131: 1593–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouri, Elie, and Rangan Gupta. 2021. Predicting Bitcoin returns: Comparing the roles of newspaper-and internet search-based measures of uncertainty. Finance Research Letters 38: 101398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouri, Elie, Oguzhan Cepni, David Gabauer, and Rangan Gupta. 2021. Return connectedness across asset classes around the COVID-19 outbreak. International Review of Financial Analysis 73: 101646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Tiejun, Chi Lau, Sadaf Cheema, and Chun Koo. 2021. Economic policy uncertainty in China and bitcoin returns: Evidence from the COVID-19 period. Frontiers in Public Health 9: 651051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Hui-Pei, and Kuang-Chueh Yen. 2020. The relationship between the economic policy uncertainty and the cryptocurrency market. Finance Research Letters 35: 101308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Jinxin, Mark Goh, and Huiwen Zou. 2021. Information spillovers and dynamic dependence between China’s energy and regional CET markets with portfolio implications: New evidence from multi-scale analysis. Journal of Cleaner Production 289: 125625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, Ender, Giray Gozgor, Chi Lau, and Samuel A. Vigne. 2018. Does economic policy uncertainty predict the Bitcoin returns? An empirical investigation. Finance Research Letters 26: 145–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diebold, Francis, and Kamil Yilmaz. 2009. Measuring financial asset return and volatility spillovers, with application to global equity markets. The Economic Journal 119: 158–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diebold, Francis, and Kamil Yilmaz. 2012. Better to give than to receive: Predictive directional measurement of volatility spillovers. International Journal of Forecasting 28: 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diebold, Francis, and Kamil Yilmaz. 2014. On the network topology of variance decompositions: Measuring the connectedness of financial firms. Journal of Econometrics 182: 119–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Libing, Honghai Yu, and Lei Li. 2017. The effect of economic policy uncertainty on the long-term correlation between US stock and bond markets. Economic Modelling 66: 139–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Libing, Elie Bouri, Rangan Gupta, and David Roubaud. 2019. Does global economic uncertainty matter for the volatility and hedging effectiveness of Bitcoin? International Review of Financial Analysis 61: 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foglia, Matteo, and Peng-Fei Dai. 2021. “Ubiquitous uncertainties”: Spillovers across economic policy uncertainty and cryptocurrency uncertainty indices. Journal of Asian Business and Economic Studies 29: 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallersdörfer, Ulrich, Lena Klaaßen, and Christian Stoll. 2020. Energy consumption of cryptocurrencies beyond bitcoin. Joule 4: 1843–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulzar, Saqib, Ghulam Mujtaba Kayani, Hui Xiaofen, Usman Ayub, and Amir Rafique. 2019. Financial cointegration and spillover effect of global financial crisis: A study of emerging Asian financial markets. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja 32: 187–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, Inzamam Ul, and Elie Bouri. 2022. Sustainable versus Conventional Cryptocurrencies in the Face of Cryptocurrency Uncertainty Indices: An Analysis across Time and Scales. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 15: 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, Inzamam Ul, Apichit Maneengam, Supat Chupradit, and Chunhui Huo. 2022a. Are green bonds and sustainable cryptocurrencies truly sustainable? Evidence from a wavelet coherence analysis. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja 36: 807–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, Inzamam Ul, Paulo Ferreira, Apichit Maneengam, and Worakamol Wisetsri. 2022b. Rare Earth Market, Electric Vehicles and Future Mobility Index: A Time-Frequency Analysis with Portfolio Implications. Risks 10: 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, Nhan, Anh Dao, and Dat Nguyen. 2021a. Openness, economic uncertainty, government responses, and international financial market performance during the coronavirus pandemic. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance 31: 100536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huynh, Nhan, Dat Nguyen, and Anh Dao. 2021b. Sectoral performance and the government interventions during COVID-19 pandemic: Australian evidence. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 14: 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Yonghong, Lanxin Wu, G. Tian, and He Nie. 2021. Do cryptocurrencies hedge against EPU and the equity market volatility during COVID-19?—New evidence from quantile coherency analysis. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money 72: 101324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, Javed, and Mohammad Hassan. 2022. Asymmetric connectedness between cryptocurrency environment attention index and green assets. The Journal of Economic Asymmetries 25: e00240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaömer, Yunus. 2022. The time-varying correlation between cryptocurrency policy uncertainty and cryptocurrency returns. Studies in Economics and Finance 39: 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, Sitara, and Muhammad Naeem. 2021. Clean Energy, Australian Electricity Markets, and Information Transmission. Energy Research Letters 3: 29973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, Sitara, and Muhammad Naeem. 2022. Do global factors drive the interconnectedness among green, Islamic and conventional financial markets? International Journal of Managerial Finance 18: 639–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, Sitara, Muhammad Naeem, Nawazish Mirza, and Jessica Paule-Vianez. 2022. Quantifying the hedge and safe-haven properties of bond markets for cryptocurrency indices. The Journal of Risk Finance 23: 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalfaoui, Rabeh, Mohamed Boutahar, and Heni Boubaker. 2015. Analyzing volatility spillovers and hedging between oil and stock markets: Evidence from wavelet analysis. Energy Economics 49: 540–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koumba, Ur, Calvin Mudzingiri, and Jules Mba. 2020. Does uncertainty predict cryptocurrency returns? A copula-based approach. Macroeconomics and Finance in Emerging Market Economies 13: 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Zheng-Zheng, Chi-Wei Su, and Meng Zhu. 2022. How Does Uncertainty Affect Volatility Correlation between Financial Assets? Evidence from Bitcoin, Stock and Gold. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 58: 2682–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucey, Brian, Samuel Vigne, Larisa Yarovaya, and Yizhi Wang. 2022. The cryptocurrency uncertainty index. Finance Research Letters 45: 102147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghyereh, Aktham, Basel Awartani, and Hussein Abdoh. 2019. The co-movement between oil and clean energy stocks: A wavelet-based analysis of horizon associations. Energy 169: 895–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokni, Khaled, Ahdi Ajmi, Elie Bouri, and Xuan Vo. 2020. Economic policy uncertainty and the Bitcoin-US stock nexus. Journal of Multinational Financial Management 57: 100656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokni, Khaled, Manel Youssef, and Ahdi Ajmi. 2022. COVID-19 pandemic and economic policy uncertainty: The first test on the hedging and safe haven properties of cryptocurrencies. Research in International Business and Finance 60: 101573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadamou, Stephanos, Nikolaos Kyriazis, and Panayiotis Tzeremes. 2021. Non-linear causal linkages of EPU and gold with major cryptocurrencies during bull and bear markets. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance 56: 101343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percival, Donald, and Andrew Walden. 2000. Wavelet Methods for Time Series Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, Linh, Sitara Karim, Muhammad Naeem, and Cheng Long. 2022. A tale of two tails among carbon prices, green and non-green cryptocurrencies. International Review of Financial Analysis 82: 102139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primiceri, Giorgio. 2005. Time varying structural vector autoregressions and monetary policy. The Review of Economic Studies 72: 821–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Boru, and Brian Lucey. 2022a. A clean, green haven?—Examining the relationship between clean energy, clean and dirty cryptocurrencies. Energy Economics 109: 105951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Boru, and Brian Lucey. 2022b. Do clean and dirty cryptocurrency markets herd differently? Finance Research Letters 47: 102795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubbaniy, Ghulame, Ali Khalid, and Aristeidis Samitas. 2021. Are cryptos safe-haven assets during covid-19? Evidence from wavelet coherence analysis. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 57: 1741–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, Imlak. 2020. Policy uncertainty and Bitcoin returns. Borsa Istanbul Review 20: 257–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, Quang Thien, Nhan Huynh, and Nhu An Huynh. 2022. Trading-off between being contaminated or stimulated: Are emerging countries doing good jobs in hosting foreign resources? Journal of Cleaner Production 379: 134649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Gang-Jin, Chi Xie, Danyan Wen, and Longfen Zhao. 2019. When Bitcoin meets economic policy uncertainty (EPU): Measuring risk spillover effect from EPU to Bitcoin. Finance Research Letters 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Pengfei, Xiao Li, Dehua Shen, and Wei Zhang. 2020. How does economic policy uncertainty affect the bitcoin market? Research in International Business and Finance 53: 101234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Yizhi, Brian Lucey, Samuel Vigne, and Larisa Yarovaya. 2022. An index of cryptocurrency environmental attention (ICEA). China Finance Review International 12: 378–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Wansah, Aviral Tiwari, Giray Gozgor, and Huang Leping. 2021. Does economic policy uncertainty affect cryptocurrency markets? Evidence from Twitter-based uncertainty measures. Research in International Business and Finance 58: 101478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Xiong, Yuxiang Bian, and Dehua Shen. 2018. The time-varying correlation between policy uncertainty and stock returns: Evidence from China. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications 499: 413–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, Kuang-Chieh, and Hui-Pei Cheng. 2021. Economic policy uncertainty and cryptocurrency volatility. Finance Research Letters 38: 101428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, Imran, Yasir Riaz, and John Goodell. 2022. Energy cryptocurrencies: Assessing connectedness with other asset classes. Finance Research Letters, 103389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Wen, and Yu-Dong Wang. 2022. On the time-varying correlations between oil-, gold-, and stock markets: The heterogeneous roles of policy uncertainty in the US and China. Petroleum Science 19: 1420–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Huiming, Yiwen Chen, Yinghua Ren, Zhanming Xing, and Liya Hau. 2022. Time-frequency causality and dependence structure between crude oil, EPU and Chinese industry stock: Evidence from multiscale quantile perspectives. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance 61: 101698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Panel A: Descriptive statistics (Original data) | ||||||||

| M | SD | Skew. | Kurt. | JB | Prob. | ADF | Obs. | |

| CNEPU | 155.2620 | 110.1860 | 3.0840 | 20.4490 | 14,770.9500 | 0.0000 | −26.7720 | 1035 |

| UKEPU | 340.9980 | 239.1110 | 1.7060 | 6.2180 | 948.6390 | 0.0000 | −12.0300 | 1035 |

| USEPU | 196.4830 | 133.6060 | 1.7170 | 6.1290 | 930.8360 | 0.0000 | −11.2390 | 1035 |

| IDEMV | 16.3420 | 13.1670 | 2.0660 | 10.2690 | 3014.9220 | 0.0000 | −15.8360 | 1035 |

| ADA | 0.0020 | 0.0600 | −0.3830 | 10.0720 | 2182.2890 | 0.0000 | −26.7720 | 1035 |

| MIOTA | 0.0000 | 0.0650 | −0.8510 | 13.1330 | 4553.0520 | 0.0000 | −12.030 | 1035 |

| XLM | 0.0010 | 0.0590 | 0.6120 | 17.4090 | 9018.2740 | 0.0000 | −11.2390 | 1035 |

| XNO | 0.0000 | 0.0750 | −1.4040 | 23.9060 | 19,187.9800 | 0.0000 | −15.8360 | 1035 |

| XRP | 0.0010 | 0.0640 | −0.1710 | 17.2390 | 8748.0520 | 0.0000 | −14.5541 | 1035 |

| GRID | 0.0010 | 0.1340 | −0.1630 | 21.3500 | 14,525.6100 | 0.0000 | −29.8821 | 1035 |

| POW | 0.0020 | 0.0760 | −0.0190 | 18.1780 | 9934.9530 | 0.0000 | −12.9171 | 1035 |

| SNC | 0.0000 | 0.0670 | −0.0720 | 17.4840 | 9048.4440 | 0.0000 | 23.2812 | 1035 |

| Panel B: Descriptive statistics of D1 (2 to 4 days) | ||||||||

| M | SD | Skew. | Kurt. | JB | Prob. | ADF | Obs. | |

| ADA.D1 | 0.0000 | 0.0440 | 0.0700 | 8.5780 | 1342.7030 | 0.0000 | −29.4492 | 1035 |

| CNEPU.D1 | 0.0000 | 70.1520 | 1.3270 | 16.0230 | 7618.3180 | 0.0000 | −13.2330 | 1035 |

| GRID.D1 | 0.0000 | 0.1010 | 0.5120 | 20.5090 | 13,266.4500 | 0.0000 | −12.3629 | 1035 |

| IDEMV.D1 | 0.0000 | 5.6050 | 0.9590 | 7.2120 | 923.7150 | 0.0000 | −17.4196 | 1035 |

| MIOTA.D1 | 0.0000 | 0.0480 | −0.2190 | 9.7040 | 1946.4830 | 0.0000 | −29.4492 | 1035 |

| POW.D1 | 0.0000 | 0.0550 | −0.0140 | 12.4460 | 3847.7960 | 0.0000 | −13.2330 | 1035 |

| SNC.D1 | 0.0000 | 0.0520 | −0.4090 | 19.0450 | 11,131.7500 | 0.0000 | −12.3629 | 1035 |

| UKEPU.D1 | 0.0000 | 82.1900 | 0.8060 | 8.6860 | 1506.4220 | 0.0000 | −17.4196 | 1035 |

| USEPU.D1 | 0.0000 | 42.7660 | 0.8620 | 7.1400 | 867.3040 | 0.0000 | −16.0095 | 1035 |

| XLM.D1 | 0.0000 | 70.1520 | 1.3270 | 16.0230 | 7618.3180 | 0.0000 | −32.8703 | 1035 |

| XNO.D1 | 0.0000 | 0.0540 | −0.4020 | 14.4600 | 5691.8620 | 0.0000 | −14.2088 | 1035 |

| XRP.D1 | 0.0000 | 0.0460 | 0.1030 | 13.3670 | 4637.0130 | 0.0000 | 25.6093 | 1035 |

| Panel C: Descriptive statistics of D2 (4 to 8 days) | ||||||||

| M | SD | Skew. | Kurt. | JB | Prob. | ADF | Obs. | |

| ADA.D2 | 0.0000 | 0.0280 | 0.0710 | 4.6100 | 112.6090 | 0.0000 | −32.3941 | 1035 |

| CNEPU.D2 | 0.0000 | 51.5500 | 0.7220 | 9.5640 | 1947.8710 | 0.0000 | −14.5563 | 1035 |

| GRID.D2 | 0.0000 | 0.0690 | −0.1270 | 15.2150 | 6437.3630 | 0.0000 | −13.5992 | 1035 |

| IDEMV.D2 | 0.0000 | 5.2250 | 0.6520 | 4.9590 | 238.9820 | 0.0000 | −19.1616 | 1035 |

| MIOTA.D2 | 0.0000 | 0.0310 | −0.1260 | 6.5520 | 546.8900 | 0.0000 | −32.3941 | 1035 |

| POW.D2 | 0.0000 | 0.0400 | 0.0110 | 10.4360 | 2384.7470 | 0.0000 | −14.5563 | 1035 |

| SNC.D2 | 0.0000 | 0.0320 | 0.0420 | 6.6630 | 578.8200 | 0.0000 | −13.5992 | 1035 |

| UKEPU.D2 | 0.0000 | 69.0410 | 0.6710 | 6.7170 | 673.6270 | 0.0000 | −19.1616 | 1035 |

| USEPU.D2 | 0.0000 | 36.4110 | 0.4520 | 5.0450 | 215.5060 | 0.0000 | −17.6105 | 1035 |

| XLM.D2 | 0.0000 | 51.5500 | 0.7220 | 9.5640 | 1947.8710 | 0.0000 | −36.1573 | 1035 |

| XNO.D2 | 0.0000 | 0.0380 | −0.6420 | 15.9670 | 7322.7660 | 0.0000 | −15.6297 | 1035 |

| XRP.D2 | 0.0000 | 0.0320 | −0.0550 | 11.5610 | 3161.2370 | 0.0000 | 28.1703 | 1035 |

| Panel D: Descriptive statistics of D3 (8 to 16 days) | ||||||||

| M | SD | Skew. | Kurt. | JB | Prob. | ADF | Obs. | |

| ADA.D3 | 0.0000 | 0.0200 | −0.0050 | 4.0790 | 50.2510 | 0.0000 | −35.6335 | 1035 |

| CNEPU.D3 | 0.0000 | 38.2350 | 0.5000 | 6.2650 | 502.8990 | 0.0000 | −16.0119 | 1035 |

| GRID.D3 | 0.0000 | 0.0410 | 0.1000 | 7.5040 | 876.6810 | 0.0000 | −14.9591 | 1035 |

| IDEMV.D3 | 0.0000 | 3.4260 | 0.2440 | 4.1820 | 70.5470 | 0.0000 | −21.0777 | 1035 |

| MIOTA.D3 | 0.0000 | 0.0210 | 0.0720 | 5.3750 | 244.0840 | 0.0000 | −35.6335 | 1035 |

| POW.D3 | 0.0000 | 0.0240 | 0.0000 | 4.9870 | 170.3290 | 0.0000 | −16.0119 | 1035 |

| SNC.D3 | 0.0000 | 0.0190 | 0.2360 | 5.3950 | 257.0310 | 0.0000 | −14.9591 | 1035 |

| UKEPU.D3 | 0.0000 | 52.3780 | 0.3790 | 6.8730 | 671.6150 | 0.0000 | −21.0777 | 1035 |

| USEPU.D3 | 0.0000 | 28.5890 | 0.1380 | 4.0920 | 54.7430 | 0.0000 | −19.3715 | 1035 |

| XLM.D3 | 0.0000 | 38.2350 | 0.5000 | 6.2650 | 502.8990 | 0.0000 | −39.7731 | 1035 |

| XNO.D3 | 0.0000 | 0.0250 | −0.6020 | 9.8640 | 2094.2210 | 0.0000 | −17.1927 | 1035 |

| XRP.D3 | 0.0000 | 0.0200 | 0.1080 | 5.9760 | 383.8930 | 0.0000 | 30.9873 | 1035 |

| Panel E: Descriptive statistics of D4 (16 to 32 days) | ||||||||

| M | SD | Skew. | Kurt. | JB | Prob. | ADF | Obs. | |

| ADA.D4 | 0.0000 | 0.0140 | −0.0580 | 3.9300 | 37.8890 | 0.0000 | −39.1969 | 1035 |

| CNEPU.D4 | 0.0000 | 32.4780 | 0.4440 | 4.2620 | 102.7110 | 0.0000 | −17.6131 | 1035 |

| GRID.D4 | 0.0000 | 0.0270 | −0.0940 | 5.8560 | 353.3490 | 0.0000 | −16.4550 | 1035 |

| IDEMV.D4 | 0.0000 | 2.5440 | 0.1400 | 3.2750 | 6.6410 | 0.0360 | −23.1855 | 1035 |

| MIOTA.D4 | 0.0000 | 0.0160 | 0.1340 | 4.6480 | 120.2100 | 0.0000 | −39.1969 | 1035 |

| POW.D4 | 0.0000 | 0.0170 | 0.0810 | 4.9000 | 156.8720 | 0.0000 | −17.6131 | 1035 |

| SNC.D4 | 0.0000 | 0.0140 | −0.0310 | 4.7100 | 126.2750 | 0.0000 | −16.4550 | 1035 |

| UKEPU.D4 | 0.0000 | 41.7260 | 0.4060 | 4.4650 | 120.8910 | 0.0000 | −23.1855 | 1035 |

| USEPU.D4 | 0.0000 | 23.6930 | 0.3200 | 4.6310 | 132.2880 | 0.0000 | −21.3087 | 1035 |

| XLM.D4 | 0.0000 | 32.4780 | 0.4440 | 4.2620 | 102.7110 | 0.0000 | −43.7504 | 1035 |

| XNO.D4 | 0.0000 | 0.0170 | −0.3760 | 7.4700 | 885.8810 | 0.0000 | −18.9119 | 1035 |

| XRP.D4 | 0.0000 | 0.0160 | −0.0190 | 6.2760 | 462.9490 | 0.0000 | 34.0860 | 1035 |

| Panel F: Descriptive statistics of D5 (32 to 64 days) | ||||||||

| M | SD | Skew. | Kurt. | JB | Prob. | ADF | Obs. | |

| ADA.D5 | 0.0000 | 0.0100 | 0.1860 | 3.2850 | 9.4620 | 0.0090 | −39.5889 | 1035 |

| CNEPU.D5 | 0.0000 | 25.0480 | 0.0550 | 3.1880 | 2.0470 | 0.0590 | −17.7893 | 1035 |

| GRID.D5 | 0.0000 | 0.0170 | 0.2640 | 4.3790 | 94.0520 | 0.0000 | −16.6196 | 1035 |

| IDEMV.D5 | 0.0000 | 2.8530 | 0.5490 | 8.1990 | 1217.6600 | 0.0000 | −23.4173 | 1035 |

| MIOTA.D5 | 0.0000 | 0.0110 | 0.2810 | 4.9150 | 171.7250 | 0.0000 | −39.5889 | 1035 |

| POW.D5 | 0.0000 | 0.0120 | −0.1500 | 3.6190 | 20.4050 | 0.0000 | −17.7893 | 1035 |

| SNC.D5 | 0.0000 | 0.0090 | 0.0020 | 3.7460 | 24.0240 | 0.0000 | −16.6196 | 1035 |

| UKEPU.D5 | 0.0000 | 40.2270 | 0.5540 | 4.3690 | 133.9040 | 0.0000 | −23.4173 | 1035 |

| USEPU.D5 | 0.0000 | 21.0890 | 0.6510 | 7.2240 | 842.5880 | 0.0000 | −21.5217 | 1035 |

| XLM.D5 | 0.0000 | 25.0480 | 0.0550 | 3.1880 | 2.0470 | 0.0510 | −44.1879 | 1035 |

| XNO.D5 | 0.0000 | 0.0120 | −0.2490 | 5.4370 | 266.7420 | 0.0000 | −19.1010 | 1035 |

| XRP.D5 | 0.0000 | 0.0110 | 0.4170 | 4.5430 | 132.6840 | 0.0000 | 34.4269 | 1035 |

| Panel G: Descriptive statistics of D6 (64 to 128 days) | ||||||||

| M | SD | Skew. | Kurt. | JB | Prob. | ADF | Obs. | |

| ADA.D6 | 0.0000 | 0.0080 | −0.1520 | 3.1660 | 5.1540 | 0.0760 | −39.9847 | 1035 |

| GRID.D6 | 0.0000 | 0.0120 | 0.0900 | 2.8940 | 1.8930 | 0.0880 | −17.9671 | 1035 |

| IDEMV.D6 | 0.0000 | 3.7780 | 1.6250 | 11.7650 | 3768.2920 | 0.0000 | −16.7858 | 1035 |

| MIOTA.D6 | 0.0000 | 0.0070 | −0.0650 | 3.1270 | 1.4150 | 0.0930 | −23.6515 | 1035 |

| POW.D6 | 0.0000 | 0.0080 | −0.2310 | 3.6250 | 26.0700 | 0.0000 | −39.9847 | 1035 |

| SNC.D6 | 0.0000 | 0.0070 | −0.1230 | 3.0090 | 2.6250 | 0.0690 | −17.9671 | 1035 |

| UKEPU.D6 | 0.0000 | 56.2440 | 0.4910 | 5.1430 | 239.6660 | 0.0000 | −16.7858 | 1035 |

| USEPU.D6 | 0.0000 | 33.2920 | 0.3300 | 7.4570 | 875.2530 | 0.0000 | −23.6515 | 1035 |

| XLM.D6 | 0.0000 | 19.1440 | −0.1650 | 4.1250 | 59.3260 | 0.0000 | −21.7370 | 1035 |

| XNO.D6 | 0.0000 | 0.0090 | −0.1760 | 2.7970 | 7.1220 | 0.0280 | −44.6298 | 1035 |

| XRP.D6 | 0.0000 | 0.0100 | −0.0400 | 4.0180 | 44.9700 | 0.0000 | −19.2921 | 1035 |

| CNEPU.D6 | 0.0000 | 19.1440 | −0.1650 | 4.1250 | 59.3260 | 0.0000 | 34.7711 | 1035 |

| Panel A: Correlation Matrix (Original data) | ||||||||||||

| CNEPU | UKEPU | USEPU | IDEMV | ADA | MIOTA | XLM | XNO | XRP | GRID | POW | SNC | |

| CNEPU | 1 | |||||||||||

| UKEPU | −0.0145 | 1 | ||||||||||

| USEPU | 0.0122 | 0.7150 | 1 | |||||||||

| IDEMV | −0.0186 | 0.4967 | 0.4699 | 1 | ||||||||

| ADA | 0.0294 | 0.0809 | 0.0478 | 0.0034 | 1 | |||||||

| MIOTA | −0.0056 | 0.0281 | 0.0355 | −0.0291 | 0.7121 | 1 | ||||||

| XLM | 0.0129 | 0.0842 | 0.0501 | 0.0346 | 0.7523 | 0.7051 | 1 | |||||

| XNO | −0.0117 | 0.0225 | 0.0516 | 0.0127 | 0.0443 | 0.0338 | 0.0726 | 1 | ||||

| XRP | −0.0212 | 0.0120 | 0.0160 | 0.0119 | 0.5667 | 0.6183 | 0.7176 | 0.1232 | 1 | |||

| GRID | −0.0401 | 0.0103 | 0.0097 | −0.0143 | 0.0500 | 0.0263 | 0.0098 | 0.0087 | 0.0283 | 1 | ||

| POW | −0.0003 | 0.0246 | 0.0174 | −0.0278 | 0.4607 | 0.5529 | 0.4692 | −0.0201 | 0.4350 | 0.0046 | 1 | |

| SNC | 0.0075 | 0.0180 | 0.0126 | −0.0473 | 0.0255 | 0.0479 | 0.0009 | 0.0369 | 0.0224 | 0.1751 | −0.0141 | 1 |

| Panel B: Correlation Matrix of D1 (2 to 4 days) | ||||||||||||

| CNEPU.D1 | UKEPU.D1 | USEPU.D1 | IDEMV.D1 | ADA.D1 | MIOTA.D1 | XLM.D1 | XNO.D1 | XRP.D1 | GRID.D1 | POW.D1 | SNC.D1 | |

| CNEPU.D1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| UKEPU.D1 | −0.0665 | 1 | ||||||||||

| USEPU.D1 | −0.0363 | −0.0765 | 1 | |||||||||

| IDEMV.D1 | −0.0638 | −0.2423 | 0.0655 | 1 | ||||||||

| ADA.D1 | 0.0263 | 0.0344 | −0.0494 | −0.0015 | 1 | |||||||

| MIOTA.D1 | −0.0009 | −0.0345 | −0.0230 | −0.0038 | 0.7163 | 1 | ||||||

| XLM.D1 | 1.0000 | −0.0665 | −0.0363 | −0.0638 | 0.0263 | −0.0009 | 1 | |||||

| XNO.D1 | −0.0406 | −0.0273 | 0.0381 | 0.0112 | 0.0925 | 0.1261 | −0.0406 | 1 | ||||

| XRP.D1 | −0.0354 | −0.0552 | −0.0309 | 0.0233 | 0.5801 | 0.6313 | −0.0354 | 0.1752 | 1 | |||

| GRID.D1 | −0.0310 | 0.0180 | 0.0212 | −0.0495 | 0.0387 | 0.0367 | −0.0310 | −0.0117 | 0.0212 | 1 | ||

| POW.D1 | −0.0043 | −0.0407 | −0.0503 | −0.0009 | 0.4613 | 0.5146 | −0.0043 | 0.0515 | 0.4558 | 0.0143 | 1 | |

| SNC.D1 | 0.0276 | 0.0126 | −0.0554 | −0.0429 | 0.0316 | 0.0613 | 0.0276 | 0.0087 | 0.0119 | 0.1554 | −0.0283 | 1 |

| Panel C: Correlation Matrix of D2 (4 to 8 days) | ||||||||||||

| CNEPU.D2 | UKEPU.D2 | USEPU.D2 | IDEMV.D2 | ADA.D2 | MIOTA.D2 | XLM.D2 | XNO.D2 | XRP.D2 | GRID.D2 | POW.D2 | SNC.D2 | |

| CNEPU.D2 | 1 | |||||||||||

| UKEPU.D2 | 0.0088 | 1 | ||||||||||

| USEPU.D2 | 0.0693 | −0.2164 | 1 | |||||||||

| IDEMV.D2 | −0.0700 | 0.2066 | −0.3051 | 1 | ||||||||

| ADA.D2 | 0.0720 | 0.0086 | −0.0528 | −0.0227 | 1 | |||||||

| MIOTA.D2 | −0.0023 | −0.0510 | 0.0120 | −0.0908 | 0.6994 | 1 | ||||||

| XLM.D2 | 1.0000 | 0.0088 | 0.0693 | −0.0700 | 0.0720 | −0.0023 | 1 | |||||

| XNO.D2 | −0.0642 | −0.0519 | −0.0123 | 0.0221 | −0.0437 | −0.0892 | −0.0642 | 1 | ||||

| XRP.D2 | −0.0134 | −0.0354 | −0.0367 | 0.0206 | 0.5174 | 0.5594 | −0.0134 | 0.0772 | 1 | |||

| GRID.D2 | −0.0118 | 0.0371 | −0.0331 | 0.0747 | 0.0763 | 0.0006 | −0.0118 | 0.0177 | 0.0207 | 1 | ||

| POW.D2 | 0.0330 | −0.0244 | −0.0051 | −0.0494 | 0.4325 | 0.5644 | 0.0330 | −0.1551 | 0.3635 | 0.0065 | 1 | |

| SNC.D2 | −0.0263 | −0.0574 | 0.0467 | −0.0227 | −0.0140 | 0.0241 | −0.0263 | −0.0070 | 0.0096 | 0.1361 | 0.0153 | 1 |

| Panel D: Correlation Matrix of D3 (8 to 16 days) | ||||||||||||

| CNEPU.D3 | UKEPU.D3 | USEPU.D3 | IDEMV.D3 | ADA.D3 | MIOTA.D3 | XLM.D3 | XNO.D3 | XRP.D3 | GRID.D3 | POW.D3 | SNC.D3 | |

| CNEPU.D3 | 1 | |||||||||||

| UKEPU.D3 | −0.0077 | 1 | ||||||||||

| USEPU.D3 | 0.0689 | 0.2153 | 1 | |||||||||

| IDEMV.D3 | −0.0302 | 0.2510 | −0.2141 | 1 | ||||||||

| ADA.D3 | 0.0023 | 0.0607 | −0.0403 | −0.0648 | 1 | |||||||

| MIOTA.D3 | −0.0307 | 0.0362 | −0.0460 | −0.0821 | 0.7110 | 1 | ||||||

| XLM.D3 | 1.0000 | −0.0077 | 0.0689 | −0.0302 | 0.0023 | −0.0307 | 1 | |||||

| XNO.D3 | 0.0364 | 0.0153 | 0.0844 | 0.0441 | −0.0815 | −0.1698 | 0.0364 | 1 | ||||

| XRP.D3 | −0.0425 | 0.0196 | −0.0193 | −0.0606 | 0.6126 | 0.6645 | −0.0425 | −0.0217 | 1 | |||

| GRID.D3 | −0.0577 | −0.0616 | −0.0840 | 0.1329 | 0.0546 | −0.0091 | −0.0577 | 0.0371 | −0.0106 | 1 | ||

| POW.D3 | −0.0570 | 0.0987 | 0.0334 | −0.0583 | 0.4948 | 0.6393 | −0.0570 | −0.1178 | 0.5094 | −0.0538 | 1 | |

| SNC.D3 | −0.0333 | −0.0273 | −0.0433 | −0.0552 | −0.0498 | −0.0225 | −0.0333 | 0.1122 | 0.0262 | 0.2389 | −0.0261 | 1 |

| Panel E: Correlation Matrix of D4 (16 to 32 days) | ||||||||||||

| CNEPU.D4 | UKEPU.D4 | USEPU.D4 | IDEMV.D4 | ADA.D4 | MIOTA.D4 | XLM.D4 | XNO.D4 | XRP.D4 | GRID.D4 | POW.D4 | SNC.D4 | |

| CNEPU.D4 | 1 | |||||||||||

| UKEPU.D4 | 0.0377 | 1 | ||||||||||

| USEPU.D4 | 0.0246 | 0.5767 | 1 | |||||||||

| IDEMV.D4 | 0.0573 | 0.4240 | 0.3213 | 1 | ||||||||

| ADA.D4 | −0.0257 | 0.1910 | 0.2215 | 0.1134 | 1 | |||||||

| MIOTA.D4 | −0.0479 | 0.0832 | 0.0837 | −0.0215 | 0.6842 | 1 | ||||||

| XLM.D4 | 1.0000 | 0.0377 | 0.0246 | 0.0573 | −0.0257 | −0.0479 | 1 | |||||

| XNO.D4 | 0.1715 | −0.0270 | −0.0220 | 0.1363 | 0.0478 | −0.0933 | 0.1715 | 1 | ||||

| XRP.D4 | 0.0515 | 0.1429 | 0.1177 | 0.2156 | 0.5977 | 0.6139 | 0.0515 | 0.0848 | 1 | |||

| GRID.D4 | −0.1291 | −0.1520 | −0.0707 | −0.1619 | −0.1811 | −0.0952 | −0.1291 | −0.0038 | −0.0228 | 1 | ||

| POW.D4 | 0.0161 | 0.1861 | 0.1796 | 0.0496 | 0.4447 | 0.6418 | 0.0161 | −0.0818 | 0.4472 | −0.2194 | 1 | |

| SNC.D4 | −0.0599 | −0.0032 | −0.0389 | −0.0987 | −0.1717 | −0.2078 | −0.0599 | 0.2532 | −0.0714 | 0.3751 | −0.3160 | 1 |

| Panel F: Correlation Matrix of D5 (32 to 64 days) | ||||||||||||

| CNEPU.D5 | UKEPU.D5 | USEPU.D5 | IDEMV.D5 | ADA.D5 | MIOTA.D5 | XLM.D5 | XNO.D5 | XRP.D5 | GRID.D5 | POW.D5 | SNC.D5 | |

| CNEPU.D5 | 1 | |||||||||||

| UKEPU.D5 | 0.2362 | 1 | ||||||||||

| USEPU.D5 | 0.1491 | 0.7446 | 1 | |||||||||

| IDEMV.D5 | 0.1037 | 0.3586 | 0.2483 | 1 | ||||||||

| ADA.D5 | 0.2004 | 0.3614 | 0.3775 | −0.0349 | 1 | |||||||

| MIOTA.D5 | 0.1455 | 0.2209 | 0.2542 | −0.0077 | 0.6688 | 1 | ||||||

| XLM.D5 | 1.0000 | 0.2362 | 0.1491 | 0.1037 | 0.2004 | 0.1455 | 1 | |||||

| XNO.D5 | −0.0399 | 0.1917 | 0.2314 | 0.0439 | 0.2103 | 0.1229 | −0.0399 | 1 | ||||

| XRP.D5 | 0.1377 | 0.2259 | 0.3021 | 0.0409 | 0.6273 | 0.6313 | 0.1377 | 0.2086 | 1 | |||

| GRID.D5 | −0.2158 | −0.0389 | 0.1027 | −0.3333 | 0.1395 | 0.0483 | −0.2158 | 0.1384 | 0.176 | 1 | ||

| POW.D5 | 0.0469 | 0.3454 | 0.3602 | −0.1501 | 0.5562 | 0.6174 | 0.0469 | 0.1403 | 0.4111 | 0.0791 | 1 | |

| SNC.D5 | 0.0358 | 0.2228 | 0.1838 | −0.2568 | 0.3663 | 0.2990 | 0.0358 | 0.0896 | 0.1881 | 0.3785 | 0.2425 | 1 |

| Panel G: Correlation Matrix of D6 (64 to 128 days) | ||||||||||||

| CNEPU.D6 | UKEPU.D6 | USEPU.D6 | IDEMV.D6 | ADA.D6 | MIOTA.D6 | XLM.D6 | XNO.D6 | XRP.D6 | GRID.D6 | POW.D6 | SNC.D6 | |

| CNEPU.D6 | 1 | |||||||||||

| UKEPU.D6 | 0.2430 | 1 | ||||||||||

| USEPU.D6 | 0.2069 | 0.8863 | 1 | |||||||||

| IDEMV.D6 | −0.0642 | 0.3183 | 0.2964 | 1 | ||||||||

| ADA.D6 | 0.1342 | 0.1510 | 0.3172 | −0.2643 | 1 | |||||||

| MIOTA.D6 | 0.1553 | 0.2226 | 0.4256 | −0.2364 | 0.7796 | 1 | ||||||

| XLM.D6 | 1.0000 | 0.2430 | 0.2069 | −0.0642 | 0.1342 | 0.1553 | 1 | |||||

| XNO.D6 | 0.0370 | 0.2293 | 0.1289 | −0.3077 | 0.0898 | 0.1526 | 0.0370 | 1 | ||||

| XRP.D6 | 0.0856 | 0.1270 | 0.2658 | −0.1230 | 0.5016 | 0.7188 | 0.0856 | 0.0993 | 1 | |||

| GRID.D6 | 0.2328 | 0.0628 | 0.2984 | −0.3565 | 0.5516 | 0.5557 | 0.2328 | 0.2601 | 0.4831 | 1 | ||

| POW.D6 | 0.1843 | 0.1970 | 0.1554 | −0.4575 | 0.4921 | 0.5083 | 0.1843 | 0.2345 | 0.4091 | 0.4882 | 1 | |

| SNC.D6 | 0.2735 | 0.3326 | 0.3623 | −0.2980 | 0.6015 | 0.5755 | 0.2735 | 0.1740 | 0.4137 | 0.5097 | 0.5622 | 1 |

| Panel A: Return Connectedness (Original data) | |||||||||||||

| CNEPU | UKEPU | USEPU | IDEMV | ADA | MIOTA | XLM | XNO | XRP | GRID | POW | SNC | FROM | |

| CNEPU | 88.320 | 4.300 | 3.000 | 2.030 | 0.350 | 0.220 | 0.250 | 0.290 | 0.450 | 0.340 | 0.200 | 0.250 | 11.680 |

| UKEPU | 1.270 | 53.530 | 17.830 | 24.020 | 0.430 | 0.410 | 0.350 | 0.490 | 0.360 | 0.510 | 0.250 | 0.530 | 46.470 |

| USEPU | 0.950 | 22.610 | 56.060 | 17.070 | 0.340 | 0.320 | 0.250 | 0.620 | 0.220 | 0.500 | 0.240 | 0.810 | 43.940 |

| IDEMV | 0.870 | 8.980 | 7.510 | 77.350 | 0.630 | 0.660 | 0.390 | 0.810 | 0.300 | 0.980 | 0.710 | 0.810 | 22.650 |

| ADA | 0.750 | 0.920 | 0.630 | 0.500 | 35.530 | 17.860 | 20.400 | 0.560 | 14.050 | 0.270 | 8.130 | 0.400 | 64.470 |

| MIOTA | 0.300 | 0.940 | 0.660 | 0.400 | 17.570 | 34.830 | 17.750 | 0.750 | 15.150 | 0.250 | 11.000 | 0.410 | 65.170 |

| XLM | 0.390 | 0.840 | 0.460 | 0.370 | 19.260 | 17.290 | 33.550 | 0.450 | 18.750 | 0.190 | 8.200 | 0.260 | 66.450 |

| XNO | 0.990 | 1.450 | 1.980 | 1.150 | 1.020 | 1.330 | 0.810 | 86.330 | 2.150 | 0.510 | 1.490 | 0.790 | 13.670 |

| XRP | 0.540 | 0.950 | 0.550 | 0.250 | 14.610 | 16.110 | 20.580 | 0.640 | 37.390 | 0.180 | 7.880 | 0.300 | 62.610 |

| GRID | 0.930 | 1.610 | 1.330 | 1.570 | 1.060 | 1.480 | 0.930 | 1.240 | 1.150 | 81.810 | 1.410 | 5.480 | 18.190 |

| POW | 0.600 | 0.710 | 0.700 | 0.540 | 10.820 | 15.170 | 11.480 | 0.500 | 9.960 | 0.260 | 48.460 | 0.800 | 51.540 |

| SNC | 0.730 | 1.750 | 2.160 | 1.510 | 0.870 | 1.330 | 0.970 | 0.550 | 0.760 | 6.030 | 1.450 | 81.890 | 18.110 |

| TO | 8.320 | 45.060 | 36.810 | 49.410 | 66.970 | 72.170 | 74.170 | 6.930 | 63.310 | 10.000 | 40.940 | 10.860 | 484.960 |

| NET | −3.370 | −1.400 | −7.130 | 26.760 | 2.500 | 7.000 | 7.710 | −6.740 | 0.700 | −8.180 | −10.590 | −7.250 | TCI = 40.41 |

| Panel B: Return Connectedness (2 to 4 days) | |||||||||||||

| CNEPU.D1 | 47.310 | 0.870 | 0.530 | 1.410 | 0.340 | 0.350 | 47.310 | 0.590 | 0.240 | 0.440 | 0.250 | 0.340 | 52.690 |

| UKEPU.D1 | 1.350 | 68.990 | 8.400 | 14.120 | 0.930 | 0.450 | 1.350 | 0.930 | 0.750 | 1.600 | 0.480 | 0.660 | 31.010 |

| USEPU.D1 | 1.990 | 21.820 | 59.510 | 7.770 | 1.040 | 0.880 | 1.990 | 1.100 | 0.770 | 1.500 | 0.720 | 0.900 | 40.490 |

| IDEMV.D1 | 2.190 | 5.930 | 2.230 | 80.300 | 1.090 | 0.900 | 2.190 | 1.090 | 0.730 | 1.170 | 0.980 | 1.200 | 19.700 |

| ADA.D1 | 1.590 | 0.830 | 0.840 | 0.840 | 40.720 | 22.210 | 1.590 | 1.130 | 16.050 | 0.630 | 12.170 | 1.400 | 59.280 |

| MIOTA.D1 | 0.970 | 0.660 | 0.500 | 0.670 | 20.150 | 41.950 | 0.970 | 1.470 | 17.540 | 0.640 | 13.600 | 0.880 | 58.050 |

| XLM.D1 | 47.310 | 0.870 | 0.530 | 1.410 | 0.340 | 0.350 | 47.310 | 0.590 | 0.240 | 0.440 | 0.250 | 0.340 | 52.690 |

| XNO.D1 | 3.450 | 1.450 | 2.600 | 1.170 | 2.920 | 4.190 | 3.450 | 68.490 | 4.660 | 1.310 | 4.220 | 2.100 | 31.510 |

| XRP.D1 | 1.460 | 1.050 | 0.780 | 0.630 | 16.750 | 20.090 | 1.460 | 1.240 | 43.440 | 0.910 | 11.290 | 0.900 | 56.560 |

| GRID.D1 | 2.470 | 2.130 | 2.260 | 2.310 | 1.920 | 2.610 | 2.470 | 2.070 | 2.370 | 73.090 | 1.720 | 4.580 | 26.910 |

| POW.D1 | 1.790 | 0.790 | 1.180 | 1.300 | 11.220 | 15.720 | 1.790 | 1.150 | 10.650 | 0.640 | 52.680 | 1.120 | 47.320 |

| SNC.D1 | 2.200 | 1.360 | 3.120 | 1.870 | 2.650 | 3.030 | 2.200 | 1.690 | 1.570 | 7.210 | 2.460 | 70.640 | 29.360 |

| TO | 66.770 | 37.750 | 22.980 | 33.500 | 59.340 | 70.780 | 66.770 | 13.060 | 55.570 | 16.500 | 48.150 | 14.420 | 505.580 |

| NET | 14.080 | 6.730 | −17.510 | 13.800 | 0.060 | 12.720 | 14.080 | −18.450 | −1.000 | −10.410 | 0.820 | −14.940 | TCI = 42.13 |

| Panel C: Return Connectedness (4 to 8 days) | |||||||||||||

| CNEPU.D2 | 41.120 | 2.650 | 2.250 | 1.580 | 1.270 | 1.880 | 41.120 | 0.840 | 2.880 | 3.460 | 0.250 | 0.700 | 58.880 |

| UKEPU.D2 | 2.560 | 63.380 | 10.470 | 10.610 | 1.320 | 1.860 | 2.560 | 0.960 | 2.330 | 2.080 | 0.800 | 1.070 | 36.620 |

| USEPU.D2 | 2.390 | 17.900 | 57.140 | 6.380 | 1.400 | 2.860 | 2.390 | 1.020 | 2.560 | 3.920 | 0.980 | 1.060 | 42.860 |

| IDEMV.D2 | 2.220 | 10.300 | 7.640 | 60.970 | 1.540 | 3.000 | 2.220 | 1.050 | 3.490 | 4.830 | 1.480 | 1.250 | 39.030 |

| ADA.D2 | 2.470 | 2.110 | 2.200 | 2.200 | 41.160 | 19.760 | 2.470 | 1.560 | 13.510 | 2.990 | 8.360 | 1.200 | 58.840 |

| MIOTA.D2 | 2.130 | 1.900 | 2.970 | 2.430 | 17.840 | 36.210 | 2.130 | 1.520 | 15.700 | 5.630 | 10.200 | 1.330 | 63.790 |

| XLM.D2 | 41.120 | 2.650 | 2.250 | 1.580 | 1.270 | 1.880 | 41.120 | 0.840 | 2.880 | 3.460 | 0.250 | 0.700 | 58.880 |

| XNO.D2 | 3.150 | 2.930 | 3.040 | 2.640 | 2.170 | 3.790 | 3.150 | 66.670 | 3.130 | 3.920 | 2.890 | 2.530 | 33.330 |

| XRP.D2 | 3.060 | 2.650 | 2.910 | 2.700 | 13.970 | 17.630 | 3.060 | 0.830 | 41.240 | 5.990 | 5.030 | 0.920 | 58.760 |

| GRID.D2 | 4.040 | 2.610 | 4.130 | 3.440 | 1.780 | 6.320 | 4.040 | 1.210 | 6.510 | 61.810 | 0.990 | 3.120 | 38.190 |

| POW.D2 | 1.210 | 1.250 | 1.760 | 1.700 | 13.050 | 15.780 | 1.210 | 2.680 | 7.920 | 2.240 | 49.270 | 1.920 | 50.730 |

| SNC.D2 | 2.570 | 2.850 | 3.870 | 3.820 | 0.970 | 2.070 | 2.570 | 1.820 | 2.980 | 6.100 | 2.470 | 67.930 | 32.070 |

| TO | 66.930 | 49.800 | 43.490 | 39.070 | 56.570 | 76.840 | 66.930 | 14.330 | 63.890 | 44.600 | 33.690 | 15.810 | 571.960 |

| NET | 8.050 | 13.180 | 0.630 | 0.040 | −2.260 | 13.050 | 8.050 | −18.990 | 5.130 | 6.420 | −17.040 | −16.270 | TCI = 47.66 |

| Panel D: Return Connectedness (8 to 16 days) | |||||||||||||

| CNEPU.D3 | 42.440 | 1.200 | 0.990 | 1.530 | 0.550 | 1.200 | 42.440 | 2.590 | 1.100 | 1.070 | 1.420 | 3.470 | 57.560 |

| UKEPU.D3 | 2.320 | 54.630 | 7.770 | 15.970 | 2.690 | 3.590 | 2.320 | 2.530 | 1.440 | 2.120 | 1.950 | 2.680 | 45.370 |

| USEPU.D3 | 3.130 | 16.340 | 45.660 | 9.900 | 2.340 | 1.470 | 3.130 | 2.620 | 1.270 | 8.080 | 2.360 | 3.690 | 54.340 |

| IDEMV.D3 | 2.700 | 7.440 | 6.550 | 55.350 | 4.600 | 5.630 | 2.700 | 2.890 | 1.880 | 3.470 | 2.530 | 4.270 | 44.650 |

| ADA.D3 | 3.720 | 2.480 | 2.420 | 2.130 | 33.890 | 15.950 | 3.720 | 9.630 | 9.000 | 3.870 | 9.320 | 3.890 | 66.110 |

| MIOTA.D3 | 3.620 | 2.060 | 1.800 | 2.550 | 15.170 | 32.910 | 3.620 | 9.930 | 8.030 | 3.120 | 13.110 | 4.080 | 67.090 |

| XLM.D3 | 42.440 | 1.200 | 0.990 | 1.530 | 0.550 | 1.200 | 42.440 | 2.590 | 1.100 | 1.070 | 1.420 | 3.470 | 57.560 |

| XNO.D3 | 4.560 | 2.060 | 3.150 | 3.470 | 5.690 | 6.930 | 4.560 | 51.670 | 3.600 | 3.940 | 5.710 | 4.670 | 48.330 |

| XRP.D3 | 3.270 | 1.590 | 1.530 | 2.200 | 15.590 | 14.710 | 3.270 | 5.540 | 33.290 | 4.200 | 10.310 | 4.500 | 66.710 |

| GRID.D3 | 2.680 | 2.240 | 2.360 | 3.610 | 4.680 | 4.740 | 2.680 | 5.490 | 4.960 | 54.280 | 5.530 | 6.770 | 45.720 |

| POW.D3 | 2.830 | 1.460 | 1.400 | 2.720 | 12.030 | 15.140 | 2.830 | 6.900 | 8.000 | 3.150 | 39.400 | 4.130 | 60.600 |

| SNC.D3 | 2.800 | 2.800 | 2.530 | 3.780 | 3.870 | 5.020 | 2.800 | 7.210 | 2.570 | 5.650 | 5.350 | 55.620 | 44.380 |

| TO | 74.060 | 40.860 | 31.490 | 49.380 | 67.760 | 75.550 | 74.060 | 57.940 | 42.960 | 39.760 | 59.000 | 45.620 | 658.420 |

| NET | 16.490 | −4.510 | −22.840 | 4.730 | 1.650 | 8.460 | 16.490 | 9.600 | −23.750 | −5.960 | −1.600 | 1.240 | TCI = 54.87 |

| Panel E: Return Connectedness (16 to 32 days) | |||||||||||||

| CNEPU.D4 | 40.360 | 2.240 | 4.400 | 2.960 | 1.620 | 1.550 | 40.360 | 1.450 | 0.990 | 1.930 | 0.780 | 1.370 | 59.640 |

| UKEPU.D4 | 5.910 | 46.850 | 11.680 | 12.560 | 2.090 | 0.780 | 5.910 | 2.650 | 3.370 | 5.060 | 1.540 | 1.590 | 53.150 |

| USEPU.D4 | 4.730 | 27.440 | 34.630 | 13.410 | 3.680 | 0.870 | 4.730 | 1.990 | 2.980 | 2.300 | 1.920 | 1.330 | 65.370 |

| IDEMV.D4 | 8.930 | 10.060 | 6.790 | 43.830 | 1.790 | 1.470 | 8.930 | 3.150 | 8.050 | 2.730 | 2.670 | 1.590 | 56.170 |

| ADA.D4 | 5.700 | 6.130 | 3.670 | 2.960 | 29.450 | 10.740 | 5.700 | 5.920 | 12.230 | 3.790 | 7.160 | 6.550 | 70.550 |

| MIOTA.D4 | 4.070 | 2.710 | 3.030 | 3.430 | 14.180 | 25.230 | 4.070 | 5.190 | 12.460 | 2.630 | 13.070 | 9.940 | 74.770 |

| XLM.D4 | 40.360 | 2.240 | 4.400 | 2.960 | 1.620 | 1.550 | 40.360 | 1.450 | 0.990 | 1.930 | 0.780 | 1.370 | 59.640 |

| XNO.D4 | 4.670 | 3.010 | 3.860 | 5.090 | 3.660 | 5.490 | 4.670 | 45.610 | 5.090 | 3.520 | 7.740 | 7.600 | 54.390 |

| XRP.D4 | 2.400 | 4.320 | 3.680 | 5.130 | 13.710 | 12.670 | 2.400 | 5.080 | 32.110 | 1.680 | 8.480 | 8.350 | 67.890 |

| GRID.D4 | 4.000 | 3.910 | 5.660 | 5.950 | 7.560 | 7.880 | 4.000 | 5.260 | 9.460 | 31.460 | 7.230 | 7.630 | 68.540 |

| POW.D4 | 3.990 | 4.250 | 3.500 | 3.720 | 6.250 | 12.290 | 3.990 | 8.030 | 9.120 | 4.280 | 29.640 | 10.950 | 70.360 |

| SNC.D4 | 6.000 | 5.440 | 4.920 | 3.760 | 10.010 | 4.620 | 6.000 | 8.120 | 5.730 | 3.540 | 7.750 | 34.100 | 65.900 |

| TO | 90.750 | 71.740 | 55.600 | 61.910 | 66.160 | 59.910 | 90.750 | 48.290 | 70.470 | 33.390 | 59.130 | 58.260 | 766.370 |

| NET | 31.110 | 18.590 | −9.770 | 5.750 | −4.390 | −14.860 | 31.110 | −6.100 | 2.580 | −35.150 | −11.220 | −7.640 | TCI = 63.86 |

| Panel F: Return Connectedness (32 to 64 days) | |||||||||||||

| CNEPU.D5 | 38.410 | 2.630 | 2.140 | 3.500 | 1.520 | 2.040 | 38.410 | 2.250 | 0.880 | 3.170 | 2.910 | 2.130 | 61.590 |

| UKEPU.D5 | 3.610 | 40.610 | 18.480 | 17.390 | 5.000 | 1.670 | 3.610 | 1.790 | 2.330 | 1.610 | 2.410 | 1.500 | 59.390 |

| USEPU.D5 | 2.680 | 25.040 | 36.250 | 13.280 | 4.730 | 1.940 | 2.680 | 2.050 | 3.670 | 1.850 | 2.870 | 2.970 | 63.750 |

| IDEMV.D5 | 3.680 | 11.820 | 10.200 | 46.550 | 2.800 | 2.810 | 3.680 | 4.380 | 2.000 | 5.560 | 3.330 | 3.200 | 53.450 |

| ADA.D5 | 4.540 | 6.910 | 7.690 | 3.230 | 29.070 | 11.240 | 4.540 | 4.640 | 15.390 | 3.290 | 6.380 | 3.070 | 70.930 |

| MIOTA.D5 | 2.630 | 4.610 | 4.860 | 3.570 | 14.660 | 30.730 | 2.630 | 3.920 | 14.030 | 1.440 | 11.870 | 5.050 | 69.270 |

| XLM.D5 | 38.410 | 2.630 | 2.140 | 3.500 | 1.520 | 2.040 | 38.410 | 2.250 | 0.880 | 3.170 | 2.910 | 2.130 | 61.590 |

| XNO.D5 | 3.240 | 6.400 | 6.830 | 6.870 | 3.200 | 4.110 | 3.240 | 46.390 | 6.110 | 3.260 | 6.810 | 3.540 | 53.610 |

| XRP.D5 | 2.810 | 5.570 | 8.390 | 3.360 | 15.910 | 9.860 | 2.810 | 3.820 | 32.300 | 5.720 | 6.480 | 2.970 | 67.700 |

| GRID.D5 | 4.780 | 4.850 | 10.080 | 8.870 | 4.350 | 6.120 | 4.780 | 4.080 | 6.690 | 32.060 | 5.470 | 7.890 | 67.940 |

| POW.D5 | 5.290 | 6.110 | 5.980 | 2.150 | 9.480 | 14.130 | 5.290 | 2.840 | 6.950 | 6.160 | 30.690 | 4.920 | 69.310 |

| SNC.D5 | 3.540 | 7.410 | 9.600 | 2.180 | 11.670 | 9.130 | 3.540 | 2.160 | 6.270 | 4.780 | 6.660 | 33.060 | 66.940 |

| TO | 75.210 | 83.980 | 86.390 | 67.900 | 74.830 | 65.100 | 75.210 | 34.180 | 65.190 | 40.030 | 58.090 | 39.350 | 765.470 |

| NET | 13.620 | 24.590 | 22.640 | 14.450 | 3.900 | −4.170 | 13.620 | −19.430 | −2.510 | −27.920 | −11.220 | −27.590 | TCI = 63.91 |

| Panel G: Return Connectedness (64 to 128 days) | |||||||||||||

| CNEPU.D6 | 33.110 | 4.200 | 4.090 | 4.020 | 2.950 | 2.140 | 33.110 | 2.140 | 1.990 | 3.140 | 2.800 | 6.320 | 66.890 |

| UKEPU.D6 | 3.380 | 42.430 | 27.290 | 9.800 | 1.440 | 2.160 | 3.380 | 2.270 | 1.290 | 2.010 | 0.820 | 3.720 | 57.570 |

| USEPU.D6 | 2.200 | 30.070 | 39.430 | 7.710 | 3.080 | 4.310 | 2.200 | 1.080 | 2.810 | 1.710 | 1.550 | 3.840 | 60.570 |

| IDEMV.D6 | 3.270 | 5.500 | 3.080 | 45.670 | 4.500 | 4.460 | 3.270 | 4.840 | 2.490 | 8.660 | 9.050 | 5.210 | 54.330 |

| ADA.D6 | 4.100 | 5.000 | 7.400 | 3.150 | 30.510 | 11.890 | 4.100 | 1.480 | 10.480 | 6.370 | 3.650 | 11.900 | 69.490 |

| MIOTA.D6 | 2.330 | 5.320 | 9.000 | 3.610 | 17.100 | 25.890 | 2.330 | 2.650 | 15.210 | 5.640 | 5.090 | 5.840 | 74.110 |

| XLM.D6 | 33.110 | 4.200 | 4.090 | 4.020 | 2.950 | 2.140 | 33.110 | 2.140 | 1.990 | 3.140 | 2.800 | 6.320 | 66.890 |

| XNO.D6 | 5.640 | 10.700 | 9.260 | 4.980 | 4.520 | 4.510 | 5.640 | 41.380 | 4.350 | 2.310 | 3.020 | 3.690 | 58.620 |

| XRP.D6 | 3.230 | 3.890 | 5.610 | 1.830 | 15.200 | 15.480 | 3.230 | 1.670 | 30.620 | 6.500 | 4.370 | 8.370 | 69.380 |

| GRID.D6 | 3.350 | 3.730 | 5.070 | 5.430 | 10.230 | 6.600 | 3.350 | 3.860 | 10.810 | 30.790 | 6.810 | 9.970 | 69.210 |

| POW.D6 | 2.520 | 4.840 | 6.580 | 5.160 | 8.720 | 12.630 | 2.520 | 2.920 | 9.180 | 6.250 | 32.490 | 6.200 | 67.510 |

| SNC.D6 | 5.450 | 7.540 | 7.690 | 5.580 | 10.460 | 6.060 | 5.450 | 3.080 | 5.690 | 5.290 | 4.520 | 33.190 | 66.810 |

| TO | 68.570 | 84.990 | 89.150 | 55.280 | 81.140 | 72.380 | 68.570 | 28.150 | 66.290 | 51.010 | 44.470 | 71.390 | 781.400 |

| NET | 1.680 | 27.420 | 28.580 | 0.950 | 11.650 | −1.730 | 1.680 | −30.470 | −3.090 | −18.200 | −23.050 | 4.570 | TCI = 65.12 |

| Volatility Transmitters | Volatility Recipients | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | CNEPU | UKEPU | USEPU | IDEMV | ADA | MIOTA | XLM | XNO | XRP | GRID | POW | SNC |

| Original Returns | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| D1:(2–4 days) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| D2:(4–8 days) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| D3:(8–16 days) | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| D4:(16–32 days) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| D5:(32–64 days) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| D6:(64–128 days) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Haq, I.U.; Ferreira, P.; Quintino, D.D.; Huynh, N.; Samantreeporn, S. Economic Policy Uncertainty, Energy and Sustainable Cryptocurrencies: Investigating Dynamic Connectedness during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Economies 2023, 11, 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies11030076

Haq IU, Ferreira P, Quintino DD, Huynh N, Samantreeporn S. Economic Policy Uncertainty, Energy and Sustainable Cryptocurrencies: Investigating Dynamic Connectedness during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Economies. 2023; 11(3):76. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies11030076

Chicago/Turabian StyleHaq, Inzamam Ul, Paulo Ferreira, Derick David Quintino, Nhan Huynh, and Saowanee Samantreeporn. 2023. "Economic Policy Uncertainty, Energy and Sustainable Cryptocurrencies: Investigating Dynamic Connectedness during the COVID-19 Pandemic" Economies 11, no. 3: 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies11030076

APA StyleHaq, I. U., Ferreira, P., Quintino, D. D., Huynh, N., & Samantreeporn, S. (2023). Economic Policy Uncertainty, Energy and Sustainable Cryptocurrencies: Investigating Dynamic Connectedness during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Economies, 11(3), 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies11030076