A Bibliometric Analysis of Collective Bargaining: The Future of Labour Relations after the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Results

3.1. Results Obtained

3.1.1. Web of Sciences Core Collection

3.1.2. Scopus

4. Analysis of Results

4.1. Analysis of Scientific Performance: Results by Citations Received

4.2. Scientific Mapping: Maps of Bibliometric Results

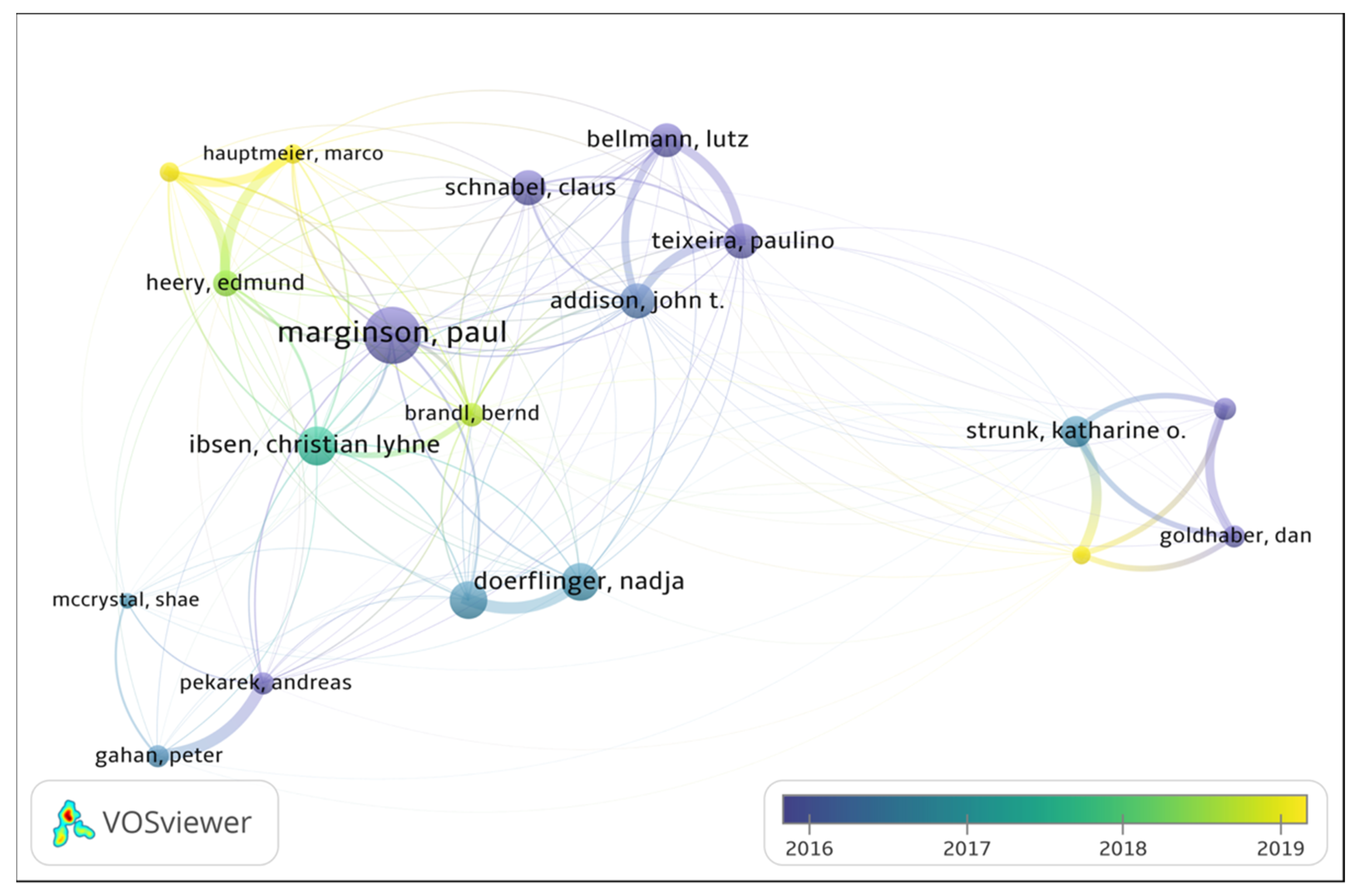

4.2.1. Bibliographic Coupling Analysis by Authors

4.2.2. Bibliographic Coupling Analysis by Documents

4.2.3. Co-Word Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. On Researchers

5.2. On the Most Cited Publications

5.3. On Keywords

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Acedo, Francisco Jose, Carmen Barroso, Cristobal Casanueva, and José Luis Galán. 2006. Co-authorship in management and organizational studies: An empirical and network analysis. Journal of Management Studies 43: 957–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, Daron, and Pascual Restrepo. 2020. Robots and jobs: Evidence from US labor markets. Journal of Political Economy 128: 2188–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, Antonis, Antonios Garas, Marina-Selini Katsaiti, and Athanasios Lapatinas. 2021. Economic complexity and jobs: An empirical analysis. Economics of Innovation and New Technology 32: 25–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addison, John T. 2016. Collective bargaining systems and macroeconomic and microeconomic flexibility: The quest for appropriate institutional forms in advanced economies. Iza Journal of Labor Policy 5: 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addison, John T., Paulino Teixeira, André Pahnke, and Lutz Bellmann. 2017. The demise of a model? The state of collective bargaining and worker representation in Germany. Economic and Industrial Democracy 38: 193–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agus, Arawati, and Rajni Selvaraj. 2020. The mediating role of employee commitment in the relationship between quality of work life and the intention to stay. Employee Relations: The International Journal 42: 1231–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aidt, Toke, and Zafiris Tzannatos. 2002. Unions and Collective Bargaining: Economic Effects in a Global Environment. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Aidt, Toke, and Zafiris Tzannatos. 2008. Trade unions, collective bargaining and macroeconomic performance: A review. Industrial Relations Journal 39: 258–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlRyalat, Saif Aldeen S., Lna W. Malkawi, and Shaher M. Momani. 2019. Comparing Bibliometric Analysis Using PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science Databases. Jove-Journal of Visualized Experiments. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Meaza, Izaskun, Naiara Pikatza-Gorrotxategi, and Rosa Maria Rio-Belver. 2020. Knowledge Sharing and Transfer in an Open Innovation Context: Mapping Scientific Evolution. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 6: 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alviz-Meza, Anibal, Manuel H. Vasquez-Coronado, Jorge G. Delgado-Caramutti, and Daniel J. Blanco-Victorio. 2022. Bibliometric analysis of fourth industrial revolution applied to heritage studies based on web of science and scopus databases from 2016 to 2021. Heritage Science 10: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amankwah-Amoah, Joseph, Zaheer Khan, Geoffrey Wood, and Gary Knight. 2021. COVID-19 and digitalization: The great acceleration. Journal of Business Research 136: 602–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anner, Mark, Matthew Fischer-Daly, and Michael Maffie. 2021. Fissured Employment and Network Bargaining: Emerging Employment Relations Dynamics in a Contingent World of Work. Ilr Review 74: 689–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelbaum, Eileen, and Ronald Schettkat. 1990. Labor Market Adjustments to Structural Change and Technological Progress. New York: Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Baylos Grau, Antonio. 2020. Post-COVID 19 Collective Bargaining Challenges for the Year That Is almost Beginning. Available online: https://cutt.ly/ANfvtzV (accessed on 26 October 2022).

- Bedoya Bedoya, Mº Rocio. 2014. Negociación colectiva. In Diccionario Internacional de Derecho del Trabajo y de la Seguridad Social. Edited by Antonio Baylos Grau, Candy Florencio Thomé and Rodrigo García Schwarz. Valencia: Tirant lo Blanch, pp. 1524–29. [Google Scholar]

- Béland, Louis-Philippe, Abel Brodeur, and Taylor Wright. 2020. The Short-Term Economic Consequences of Covid-19: Exposure to Disease, Remote Work and Government Response. IZA. Discussion Papers Serires 13159: 1–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, Richard N., ed. 2003. Bargaining for Competitiveness: Law, Research, and Case Studies. Kalamazoo: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research. [Google Scholar]

- Bourguignon, Remi, and Clotilde Coron. 2021. The micro-politics of collective bargaining: The case of gender equality. Human Relations 76: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandl, Bernd, and Barbara Bechter. 2019. The hybridization of national collective bargaining systems: The impact of the economic crisis on the transformation of collective bargaining in the European Union. Economic and Industrial Democracy 40: 469–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadus, Robert N. 1987. Toward a definition of “bibliometrics”. Scientometrics 12: 373–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodsky, Melvin M. 1994. Labor market flexibility: A changing international perspective. Monthly Labor Review 117: 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Bulfone, Fabio, and Alexandre Afonso. 2020. Business against markets: Employer resistance to collective bargaining liberalization during the eurozone crisis. Comparative Political Studies 53: 809–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgmann, Verity. 2016. Globalization and Labour in the Twenty-First Century. London: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Callon, Michel, Jean-Pierre Courtial, William A. Turner, and Serge Bauin. 1983. From translations to problematic networks: An introduction to co-word analysis. Social Science Information 22: 191–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camón Luis, Enric, and Dolors Celma. 2020. Circular Economy. A Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 12: 6381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, Debra L., and G. Steven McMillan. 2008. Identifying the “Invisible Colleges” of the Industrial & Labor Relations Review: A Bibliometric Approach. Ilr Review 62: 126–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Ho Fai, and Benno Torgler. 2020. Gender differences in performance of top cited scientists by field and country. Scientometrics 125: 2421–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chancel, Lucas, Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez, and Gabriel Zucman. 2022. World Inequality Report 2022. Available online: https://cutt.ly/LOiDLOU (accessed on 28 January 2022).

- Cobo, Manuel J., Antonio Gabriel López-Herrera, Enrique Herrera-Viedma, and Francisco Herrera. 2011. An approach for detecting, quantifying, and visualizing the evolution of a research field: A practical application to the Fuzzy Sets Theory field. Journal of Informetrics 5: 146–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, Ian, and Philip James. 2020. Trends in Collective Bargaining, Wage Stagnation and Income Inequality under Austerity. In Working in the Context of Austerity: Challenges and Struggles. Edited by Donna Baines and Ian Cunningham. Bristol: Bristol University Press, pp. 71–96. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Paul, and Mark Freedland. 1983. Kahn-Freund’s Labour and the Law, 3rd ed. London: Stevens. [Google Scholar]

- Doellgast, Virginia. 2012. Disintegrating Democracy at Work: Labor Unions and the Future of Good Jobs in the Service Economy. Ithaca: ILR Press. [Google Scholar]

- Donaghey, Jimmy, Juliane Reinecke, Christina Niforou, and Benn Lawson. 2014. From employment relations to consumption relations: Balancing labor governance in global supply chains. Human Resource Management 53: 229–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorigatti, Lisa, and Roberto Pedersini. 2021. Industrial relations and inequality: The many conditions of a crucial relationship. Transfer-European Review of Labour and Research 27: 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, John H., and Sarianna M. Lundan. 2008. Multinational Enterprises and the Global Economy, 2nd ed. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. [Google Scholar]

- Eaton, Adrienne, and Charles Heckscher. 2021. COVID’s Impacts on the Field of Labour and Employment Relations. Journal of Management Studies 58: 273–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, Fiona, Alan Geare, Maria Halhjem, Kate Reese, and Christian Thoresen. 2015. Well-being and performance: Measurement issues for HRM research. International Journal of Human Resource Management 26: 1983–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, Fiona, and Alan Geare. 2014. An employee-centred analysis: Professionals’ experiences and reactions to HRM. International Journal of Human Resource Management 25: 673–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egghe, Leo, and Ronald Rousseau. 1990. Introduction to Informetrics: Quantitative Methods in Library, Documentation and Information Science. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Escribano Gutiérrez, Juan. 2013. La negociación colectiva en España tras las reformas de 2010, 2011 y 2012. Revista Internacional y Comparada de Relaciones Laborales y Derecho del Empleo 1: 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. 2013. Industrial Relations in Europe 2012. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament. 2017. European Parliament Resolution of 4 July 2017 on Working Conditions and Precarious Employment (2016/2221(INI)). Bruxelles: European Parliament. [Google Scholar]

- Fay, Daniel L., and Adela Ghadimi. 2020. Collective Bargaining during Times of Crisis: Recommendations from the COVID-19 Pandemic. Public Administration Review 80: 815–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freyssinet, Jacques, and Hartmut Seifert. 2001. Pacts for employment and competitiveness in Europe. Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research 7: 616–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfield, Eugene. 1977. Introducing citation classics-human side of scientific reports. Current Contents 1: 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Garfield, Eugene. 1979. Citation Indexing—Its Theory and Application in Science, Technology, and Humanities. New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Garnero, Andrea. 2021. The impact of collective bargaining on employment and wage inequality: Evidence from a new taxonomy of bargaining systems. European Journal of Industrial Relations 27: 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gereffi, Gary, Anne Caroline Posthuma, and Arianna Rossi. 2021. Introduction: Disruptions in global value chains—Continuity or change for labour governance? International Labour Review 160: 501–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassner, Vera, and Maarten Keune. 2012. The crisis and social policy: The role of collective agreements. International Labour Review 151: 351–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassner, Vera, Maarten Keune, and Paul Marginson. 2011. Collective bargaining in a time of crisis: Developments in the private sector in Europe. Transfer-European Review of Labour and Research 17: 303–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, Michael E., and Julia E. Purvis. 1991. Journal Publication Records as a Measure of Research Performance in Industrial Relations. Ilr Review 45: 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, Maria J., and Andrew Booth. 2009. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J 26: 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, Ian, and Virginia Doellgast. 2017. Marketization, inequality, and institutional change: Toward a new framework for comparative employment relations. Journal of Industrial Relations 59: 192–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, David E. 2017. Human resource management and employee well-being: Towards a new analytic framework. Human Resource Management Journal 27: 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, Qinchang, Chengliang Liu, and Debin Du. 2019. Globalization of science and international scientific collaboration: A network perspective. Geoforum 105: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haipeter, Thomas, and Steffen Lehndorff. 2009. Dialogue Working Paper Nº. 3. Collective Bargaining on Employment. Geneva: International Labour Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Harborth, David, and Katharina Kumpers. 2021. Intelligence augmentation: Rethinking the future of work by leveraging human performance and abilities (Nov, 10.1007/s10055-021-00590-7, 2021). Virtual Reality 26: 1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayter, Susan. 2011a. Introduction. In The Role of Collective Bargaining in the Global Economy: Negotiating for Social Justice. Edited by Susan Hayter. Geneva: Edward Elgar and International Labour Office, p. x. 327p. [Google Scholar]

- Hayter, Susan. 2011b. The Role of Collective Bargaining in the Global Economy: Negotiating for Social Justice. Geneva: Edward Elgar and International Labour Office. [Google Scholar]

- Hayter, Susan, and Jelle Visser. 2018. The application and extension of collective agreements: Enhancing the inclusiveness of labour protection. In Collective Agrements: Extending Labour Protection. Edited by Susan Hayter and Jelle Visser. Geneva: International Labour Organization, pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hayter, Susan, and Jelle Visser. 2021. Making collective bargaining more inclusive: The role of extension. International Labour Review 160: 169–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, Jorge E. 2005. An index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102: 16569–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hope, David, and Angelo Martelli. 2019. The Transition to the Knowledge Economy, Labor Market Institutions, and Income Inequality in Advanced Democracies. World Politics 71: 236–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, M. Reza, Igor Martek, Edmundas Kazimieras Zavadskas, Ajibade A. Aibinu, Mehrdad Arashpour, and Nicholas Chileshe. 2018. Critical evaluation of off-site construction research: A Scientometric analysis. Automation in Construction 87: 235–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, Chris. 2021. Rethinking the Role of the State in Employment Relations for a Neoliberal Era. Ilr Review 74: 739–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyman, Richard. 2004. Whose (social) partnership? In Partnership and Modernisation in Employment Relations. Edited by Miguel Martinez Lucio and Mark Stuart. London: Routledge, pp. 251–65. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Ying, Jannik Schuehle, Alan L. Porter, and Jan Youtie. 2015. A systematic method to create search strategies for emerging technologies based on the Web of Science: Illustrated for ‘Big Data’. Scientometrics 105: 2005–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibsen, Christian Lyhne, and Maite Tapia. 2017. Trade union revitalisation: Where are we now? Where to next? Journal of Industrial Relations 59: 170–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ILO. 1998. ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work. Edited by IO. Geneva: Eighty-sixth Session of the International Labour Organization. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. 2016. Collective Bargaining. A Policy Guide. Geneve: International Labour Office. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. 2020. ILO Monitor: COVID-19 and the World of Work. 1st Edition. Available online: https://cutt.ly/NIgfTXB (accessed on 14 January 2022).

- Inanc, Hande, and Arne L. Kalleberg. 2022. Institutions, Labor Market Insecurity, and Well-Being in Europe. Social Sciences 11: 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, Fiona, and Julie Smith. 2021. Work-from-home during COVID-19: Accounting for the care economy to build back better. The Economic and Labour Relations Review 32: 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, BiHui, LiMing Liang, Ronald Rousseau, and Leo Egghe. 2007. The R- and AR-indices: Complementing the h-index. Chinese Science Bulletin 52: 855–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaine, Sarah, and Emmanuel Josserand. 2019. The organisation and experience of work in the gig economy. Journal of Industrial Relations 61: 479–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalleberg, Arne L. 2000. Nonstandard Employment Relations: Part-time, Temporary and Contract Work. Annual Review of Sociology 26: 341–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataria, Aakanksha, Satish Kumar, Riya Sureka, and Bindu Gupta. 2020. Forty years of Employee Relations—The International Journal: A bibliometric overview. Employee Relations: The International Journal 42: 1205–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, Maxwell Mirton. 1963. Bibliographic coupling between scientific papers. American Documentation 14: 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keune, Maarten. 2021. Inequality between capital and labour and among wage-earners: The role of collective bargaining and trade unions. Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research 27: 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Haemi, Jinyoung Im, and Yeon Ho Shin. 2021. The impact of transformational leadership and commitment to change on restaurant employees’ quality of work life during a crisis. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 48: 322–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koçer, Rüya Gökhan, and Susan Hayter. 2011. Comparative Study of Labour Relations in African Countries. Amsterdam: Amsterdam Institute for Advanced Labour Studies, University of Amsterdam. [Google Scholar]

- Kosch, Oskar, and Marek Szarucki. 2020. Transatlantic Affiliations of Scientific Collaboration in Strategic Management: A Quarter-Century of Bibliometric Evidence. Journal of Business Economics and Management 21: 627–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krugman, Paul R. 1999. The Return of Depression Economics, 1st ed. New York: W.W. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Kwiek, Marek, and Wojciech Roszka. 2020. Gender Disparities in International Research Collaboration: A Study of 25,000 University Professors. Journal of Economic Surveys 35: 1344–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, Melissa, Hayley MacGregor, Ian Scoones, and Annie Wilkinson. 2021. Post-pandemic transformations: How and why COVID-19 requires us to rethink development. World Development 138: 105233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Sangheon, Dorothea Schmidt-Klau, and Sher Verick. 2020. The Labour Market Impacts of the COVID-19: A Global Perspective. The Indian Journal of Labour Economics 63: 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liukkunen, Ulla. 2019. The Role of Collective Bargaining in Labour Law Regimes: A Global Approach. In Collective Bargaining in Labour Law Regimes: A Global Perspective. Edited by Ulla Liukkunen. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer International Publishing, pp. 1–64. [Google Scholar]

- López-Andreu, Martí. 2019a. Employment institutions under liberalization pressures: Analysing the effects of regulatory change on collective bargaining in Spain. British Journal of Industrial Relations 57: 328–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Andreu, Martí. 2019b. Neoliberal trends in collective bargaining and employment regulation in Spain, Italy and the UK: From institutional forms to institutional outcomes. European Journal of Industrial Relations 25: 309–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucio, Miguel Martinez, and Mark Stuart. 2005. ‘Partnership’ and new industrial relations in a risk society:an age of shotgun weddings and marriages of convenience? Work, Employment and Society 19: 797–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddi, Abdelghani, and Yves Gingras. 2021. Gender Diversity in Research Teams and Citation Impact in Economics and Management. Journal of Economic Surveys 35: 1381–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makridis, Christos A., and Joo Hun Han. 2021. Future of work and employee empowerment and satisfaction: Evidence from a decade of technological change. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 173: 121162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyika, James, Michael Chui, Mehdi Miremadi, Jacques Bughin, Katy George, Paul Willmott, and Martin Dewhurst. 2017. A Future that Works: Automation, Employment, and Productivity. Available online: https://cutt.ly/6OWUOaw (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Marenco, Matteo, and Timo Seidl. 2021. The discursive construction of digitalization: A comparative analysis of national discourses on the digital future of work. European Political Science Review 13: 391–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marginson, Paul, and Keith Sisson. 1998. European collective bargaining: A virtual prospect? Journal of Common Market Studies 36: 505–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marginson, Paul, and Manuela Galetto. 2014. Engaging with flexibility and security: Rediscovering the role of collective bargaining. Economic and Industrial Democracy 37: 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Martin, Alberto, Enrique Orduna-Malea, and Emilio Delgado Lopez-Cozar. 2018. Coverage of highly-cited documents in Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus: A multidisciplinary comparison. Scientometrics 116: 2175–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, Miguel Angel, Manuel Herrera, Enrique Contreras, Antonio Ruíz, and Enrique Herrera-Viedma. 2014. Characterizing highly cited papers in Social Work through H-Classics. Scientometrics 102: 1713–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, Miguel Angel, Manuel Herrera, Javier López-Gijón, and Enrique Herrera-Viedma. 2013. H-Classics: Characterizing the concept of citation classics through H-index. Scientometrics 98: 1971–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, G. Steven, and Debra L. Casey. 2010. Paradigm shifts in industrial relations: A bibliometric and social network approach. In Advances in Industrial and Labor Relations. Edited by David Lewin, Bruce E. Kaufman and Paul J. Gollan. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited, Volume 17, pp. 207–55. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, Rebecca, Yun Shen, and Lan Snell. 2021. The future of work: A systematic literature review. Accounting and Finance 62: 2667–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongeon, Philippe, and Adele Paul-Hus. 2016. The journal coverage of Web of Science and Scopus: A comparative analysis. Scientometrics 106: 213–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munduate, Lourdes, Martin Euwema, and Patricia Elgoibar. 2012. Ten Steps for Empowering Employee Representatives in the New European Industrial Relations. Madrid: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Müller-Jentsch, Walther. 2004. Theoretical approaches to industrial relations. In Theoretical Perspectives on Work and the Employment Relationship. Edited by Bruce Kaufman. Champaign: Industrial Relations Research Association, pp. 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Nadler, David A., and Edward E. Lawler. 1983. Quality of work life: Perspectives and directions. Organizational Dynamics 11: 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Matthew A., Anthony Naranjo, Ann E. Schlotzhauer, Mindy K. Shoss, Nika Kartvelishvili, Matthew Bartek, Kenneth Ingraham, Alexis Rodriguez, Sara Kira Schneider, Lauren Silverlieb-Seltzer, and et al. 2021. Has the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the future of work or changed its course? Implications for research and practice. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 10199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicola, Maria, Zaid Alsafi, Catrin Sohrabi, Ahmed Kerwan, Ahmed Al-Jabir, Christos Iosifidis, Maliha Agha, and Riaz Agha. 2020. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): A review. International Journal of Surgery 78: 185–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 1999. Implementing the OECD Jobs Strategy: Assessing Performance and Policy. Paris: OECD. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. 2018. Good Jobs for All in a Changing World of Work: The OECD Jobs Strategy. Paris: OECD. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. 2019. Negotiating Our Way Up: Collective Bargaining in a Changing World of Work. Paris: OECD Publising. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega Lozano, Pompeyo Gabriel. 2022. Collective bargaining, legitimation and consultation periods in the negotiating process: Problems of interpretation. Revista General del Derecho del Trabajo y de la Seguridad Social 61: 188–237. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford Economics, and Society for Human Resources Management. 2021. The Future of Work Arrives Early. How HR Leaders Are Leveraging the Lessons of Disruption. Available online: https://cutt.ly/COvzYM1 (accessed on 1 February 2022).

- Palomino, Juan C., Juan G. Rodríguez, and Raquel Sebastian. 2020. Wage inequality and poverty effects of lockdown and social distancing in Europe. European Economic Review 129: 103564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panimbang, Ismail Fahmi. 2017. Resistance on the Continent of Labour: Strategies and Initiatives of Labour Organizing in Asia. Hong Kong: Asia Monitor Resource Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Peetz, David. 2019. The Realities and Futures of Work. Acton: ANU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Perianes-Rodriguez, Antonio, Ludo Waltman, and Nees Jan van Eck. 2016. Constructing bibliometric networks: A comparison between full and fractional counting. Journal of Informetrics 10: 1178–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piketty, Thomas. 2015. The Economics of Inequality. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pollack, Julien, and Daniel Adler. 2015. Emergent trends and passing fads in project management research: A scientometric analysis of changes in the field. International Journal of Project Management 33: 236–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouliakas, Konstantinos, and Jiri Branka. 2020. EU Jobs at Highest Risk of COVID-19 Social Distancing: Is the Pandemic Exacerbating the Labour Market Divide? Working Paper No 1; Luxembourg: CEDEFOP.

- Pulignano, Valeria, Miguel Martinez Lucio, and Michael Whittall. 2012. Systems of representation in Europe: Variety around a social model. In Ten Steps for Empowering Employee Representatives in the New European Industrial Relations. Edited by Lourdes Munduate, Martin Euwema and Patricia Elgoibar. Madrid: McGraw-Hill, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ravenscroft, James, Maria Liakata, Amanda Clare, and Daniel Duma. 2017. Measuring scientific impact beyond academia: An assessment of existing impact metrics and proposed improvements. PLoS ONE 12: e0173152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodgers, Gerry, Eddy Lee, Lee Swepston, and Jasmien van Daele. 2009. The International Labour Organization and the Quest for Social Justice, 1919–2009. Geneva: International Labour Office. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, Benjamin I. 2013. The unbundled union: Politics without collective bargaining. Yale LJ 123: 148. [Google Scholar]

- Salmerón-Manzano, Esther, and Francisco Manzano-Agugliaro. 2017. Worldwide Scientific Production Indexed by Scopus on Labour Relations. Publications 5: 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoni de Sio, Filippo, Txai Almeida, and Jeroen van den Hoven. 2021. The future of work: Freedom, justice and capital in the age of artificial intelligence. Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisson, Keith, and Antonio Martín Artiles. 2000. Handling Restructuring. Collective Agreements on Employment and Competitiveness. Luxembourg: European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions. [Google Scholar]

- Soares, Sergei, and Janine Berg. 2021. Transitions in the labour market under COVID-19: Who endures, who doesn’t and the implications for inequality. International Labour Review 161: 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todoli-Signes, Adrian. 2019. Algorithms, artificial intelligence and automated decisions concerning workers and the risks of discrimination: The necessary collective governance of data protection. Transfer-European Review of Labour and Research 25: 465–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todoli-Signes, Adrian. 2021. Regulación del Trabajo y Política Económica. De cómo los Derechos Laborales Mejoran la Economía. Navarra: Aranzadi. [Google Scholar]

- Troth, Ashlea C., and David E. Guest. 2019. The case for psychology in human resource management research. Human Resource Management Journal 30: 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzannatos, Zafiris, and Toke Aidt. 2006. Unions and microeconomic performance: A look at what matters for economists (and employers). International Labour Review 145: 257–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Üsdiken, Behlül, and Yorgo Pasadeos. 1995. Organizational Analysis in North America and Europe: A Comparison of Co-citation Networks. Organization Studies 16: 503–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valizade, Danat, Chidiebere Ogbonnaya, Olga Tregaskis, and Chris Forde. 2016. A mutual gains perspective on workplace partnership: Employee outcomes and the mediating role of the employment relations climate. Human Resource Management Journal 26: 351–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Beurden, Jeske, Marc Van Veldhoven, and Karina Van de Voorde. 2022. A needs-supplies fit perspective on employee perceptions of HR practices and their relationship with employee outcomes. Human Resource Management Journal 32: 928–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, Nees Jan, and Ludo Waltman. 2010. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 84: 523–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaughan-Whitehead, Daniel, and Rosalia Vazquez-Alvarez. 2018. Curbing inequalities in Europe: The impact of industrial relations and labour policies. In Reducing Inequalities in Europe: How Industrial Relations and Labour Policies Can Close the Gap. Edited by Daniel Vaughan-Whitehead. London: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 1–67. [Google Scholar]

- Vernon, Guy, and Mark Rogers. 2013. Where Do Unions Add Value? Predominant Organizing Principle, Union Strength and Manufacturing Productivity Growth in the OECD. British Journal of Industrial Relations 51: 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, Jelle. 2016. What happened to collective bargaining during the great recession? Iza Journal of Labor Policy 5: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, Rick, and Wolfgang H. Güttel. 2012. The Dynamic Capability View in Strategic Management: A Bibliometric Review. International Journal of Management Reviews 15: 426–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, Richard E., and Robert B. McKersie. 1991. A Behavioral Theory of Labor Negotiations: An Analysis of a Social Interaction System. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Windmuller, John P., Willen Albeda, Lars-Gunnar Albage, Roger Blanpain, Guy Caire, Donald E. Cullen, Braham Dabscheck, Harry Fjallstrom, Friedrich Furstenberg, Gino Giugni, and et al. 1987. Collective Bargaining in Industrialised Market Economies: A Reappraisal. Geneva: International Labour Office. [Google Scholar]

- World Economic Forum. 2020. The Future of Jobs. Report 2020. Available online: https://cutt.ly/YOmXvXa (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Wright, Chris F., Alex J. Wood, Jonathan Trevor, Colm McLaughlin, Wei Huang, Brian Harney, Torsten Geelan, Barry Colfer, Cheng Chang, and William Brown. 2019. Towards a new web of rules: An international review of institutional experimentation to strengthen employment protections. Employee Relations: The International Journal 41: 313–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupic, Ivan, and Tomaž Čater. 2014. Bibliometric Methods in Management and Organization. Organizational Research Methods 18: 429–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Areas | Benefits |

|---|---|

| Quality of employment | By improving wages, access to social benefits, defining aspects related to health and safety at work, and improving work organisation in terms of work–life balance. |

| Equality | It favours equal opportunities between women and men in terms of salaries, job promotion, facilitating the reconciliation of work and family life, and putting a stop to situations of harassment and sexual violence against women. |

| Training | It makes it possible to reconcile the training needs of workers with the development of the professional skills required by companies. |

| Labour relations | It makes it possible to advance labour rights for workers, facilitate worker participation, and improve the working climate through conflict resolution scenarios. It also makes it possible to adapt labour legislation to the conditions of each company. |

| Firm performance | It can make it possible to adjust companies’ production to market demand. It has a positive influence on the job performance of workers by improving well-being at work and reducing job insecurity. |

| Macroeconomy | It makes it possible to reduce levels of social inequality through the distribution of wealth. It can facilitate the adaptation of companies to changes in the economic and industrial environments. It makes it possible to define public policies aimed at favouring the dynamism of the labour market. |

| Database | Types of Research | Search Fields | Search Phrase | Period | Index | Type of Document | Total Documents |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WoS-CC | Basic search | TS = Topic (title, summary, author’s keywords, and keywords plus) | “Collective bargaining” | 2012–2021 | SCI-EXPANDED; SSCI; ESCI; BKCI-SSH; BKCI-S | Scientific papers Book chapter Bibliographic reviews Books | 1.676 |

| Scopus | Document search | TITLE-ABS-KEY (Article title, Abstract, Keywords) | “Collective bargaining” | 2012–2021 | Scientific papers Book chapter Bibliographic reviews Books | 1.971 |

| Year | Number of Records | % | Variation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 153 | 9.1% | - |

| 2013 | 154 | 9.2% | 0.7% |

| 2014 | 154 | 9.2% | 0.0% |

| 2015 | 172 | 10.3% | 11.7% |

| 2016 | 150 | 8.9% | −12.8% |

| 2017 | 138 | 8.2% | −8.0% |

| 2018 | 179 | 10.7% | 29.7% |

| 2019 | 225 | 13.4% | 25.7% |

| 2020 | 187 | 11.2% | −16.9% |

| 2021 | 164 | 9.8% | −12.3% |

| TOTAL | 1676 | 100.0% |

| Documents Type | Number of Records |

|---|---|

| Article | 1633 |

| Book chapter | 91 |

| Book reviews | 36 |

| Books | 2 |

| # | Authors | Pub. Year | Title | Content | Journal | Cited |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Breman, Jan Van der Linden, Marcel | 2014 | Informalizing the Economy: The Return of the Social Question at a Global Level | Evolution and future development of the concept of collective bargaining based on a new interpretation of the working-class concept. | Development and Change | 99 |

| 2 | Marginson, Paul | 2015 | Coordinated bargaining in Europe: From incremental corrosion to frontal assault? | The way in which collective bargaining, as an institution regulating industrial relations, has been shaped in Europe towards a more decentralised approach to the detriment of multi-employer agreements. | European Journal of Industrial Relations | 91 |

| 3 | Chan, Chris King-Chi Hui, Elaine Sio-Ieng | 2014 | The Development of Collective Bargaining in China: From Collective Bargaining by Riot to Party State-led Wage Bargaining | To examine the effect of labour strikes on the development of collective bargaining in China. | China Quarterly | 91 |

| 4 | Donaghey, Jimmy Reinecke, Juliane Niforou, Christina Lawson, Benn | 2014 | From employment relations to consumption relations: balancing labor governance in global supply chains | This article proposes an analytical framework conceptualizing the interface of employment relations and consumption relations within global supply chains, identifying four regimes of labour governance: governance gaps, collective bargaining, standards markets, and complementary regimes. | Human resource management | 70 |

| 5 | Ibsen, Christian Lyhne Tapia, Maite | 2017 | Trade union revitalisation: Where are we now? Where to next? | This article reviews and evaluates research on the role of trade unions in labour markets and society, the current decline in trade unions and trade union revitalisation. | Journal of Industrial Relations | 67 |

| 6 | Miles, Sandra Jeanquart Mangold, W. Glynn | 2014 | Employee voice: Untapped resource or social media time bomb? | Worker participation in the enterprise and as part of this collective bargaining can be targeted and managed for strategic advantage when organisations provide the right organisational context together with appropriate mechanisms for employees. | Business Horizons | 65 |

| 7 | Visser, Jelle | 2016 | What happened to collective bargaining during the great recession? | How this relates to changes in bargaining coverage, multi-employer and multi-level bargaining, rules on extension and opening clauses are the subject of this paper, which surveys developments in 38 OECD and EU countries. | IZA Journal of Labor Policy | 60 |

| 8 | Noelke, Andreas | 2016 | Economic causes of the Eurozone crisis: the analytical contribution of Comparative Capitalism | The article discusses Comparative Capitalism scholarship’s role in the Eurozone crisis, highlighting four main mechanisms: lack of coordinated wage bargaining, specialization in price-sensitive goods, weak innovation systems in Southern economies, temporary masking by increased public and private indebtedness, and systemic causes due to the construction of a common currency for heterogeneous economies. | Socio-Economic Review | 56 |

| 9 | Egels-Zanden, Niklas Merk, Jeroen | 2014 | Private Regulation and Trade Union Rights: Why Codes of Conduct Have Limited Impact on Trade Union Rights | The study analyses how corporate codes of conduct have influenced labour rights such as freedom of association and collective bargaining. | Journal of Business Ethics | 55 |

| 10 | Friedman, Eli Kuruvilla, Sarosh | 2015 | Experimentation and decentralization in China’s labor relations | The article discusses the legislative changes taking place in China to reform the regulatory framework for industrial relations and collective bargaining, making it adopt a more decentralised approach. | Human Relations | 54 |

| Position | Author | Documents Published | H-Index | Sex | University | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Addison, John T. | 11 | 32 | Man | University of South Carolina | United States |

| Marginson, Paul | 23 | Man | University of Warwick | England | ||

| 2 | Heery, Edmund | 10 | 11 | Man | Cardiff University | Wales |

| Teixeira, Paulino | 12 | Man | University of Coimbra | Portugal | ||

| 3 | Bellmann, Lutz | 9 | 13 | Man | University of Erlangen | Germany |

| McCrystal, Shae | 6 | Woman | University of Sydney | Australia | ||

| Pulignano, Valeria | 14 | Woman | KU Leuven | Belgic | ||

| 4 | Brandl, Bernd | 8 | 13 | Man | Durham University | England |

| Hauptmeier, Marco | 11 | Man | Cardiff University | Wales | ||

| Ibsen, Christian Lyhne | 11 | Man | University of Copenhagen | Denmark | ||

| Marianno, Bradley D. | 6 | Man | University of Nevada | United States | ||

| Strunk, Katharine O. | 1 | Woman | Michigan State University | United States | ||

| 5 | Bray, Mark | 7 | 9 | Man | RMIT University | Australia |

| Doerflinger, Nadja | 8 | Woman | KU Leuven | Belgic | ||

| Gahan, Peter | 12 | Man | University of Melbourne | Australia | ||

| Gooberman, Leon | 5 | Man | Cardiff University | Wales | ||

| Ilsøe, Anna | 8 | Woman | Lund University | Denmark | ||

| Pekarek, Andreas | 8 | Man | University of Melbourne | Australia | ||

| Schnabel, Claus | 4 | Man | University of Erlangen | Germany |

| Position | Journal | #TD | IF 2020 | IF 5 Years | BQ | Publisher |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Revista General de Derecho del Trabajo y de la Seguridad Social | 63 | – | – | – | Iustel |

| 2 | European Journal of Industrial Relations | 55 | 2.553 | 2.754 | Q2 | Sage |

| 3 | Journal of Industrial Relations | 55 | 2.079 | 2.259 | Q3 | Sage |

| 4 | Transfer, The European Review of Labour and Research | 54 | 1.370 | 2.886 | Q3 | Sage |

| 5 | Economic and Industrial Democracy | 48 | 2.947 | 2.810 | Q2 | Sage |

| 6 | British Journal of Industrial Relations | 44 | 3.323 | 3.443 | Q2 | Wiley |

| 7 | ILR Review | 39 | 4.543 | 4.415 | Q1 | Sage |

| 8 | Employee Relations | 34 | 2.248 | 3.091 | Q3 | Emerald |

| 9 | Industrial Relations Journal. | 33 | Q3 | Wiley | ||

| 10 | Labor History | 30 | 0.561 | 0.805 | Q4 | Taylor & Francis |

| Position | Research Areas | Documents Published |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Business economics | 1044 |

| 2 | Government law | 360 |

| 3 | Social sciences. Other topics | 102 |

| 4 | Sociology | 84 |

| 5 | History | 79 |

| 6 | Education educational research | 60 |

| 7 | Public administration | 46 |

| 8 | Area studies (studies by geographical areas or countries) | 38 |

| 9 | International relations | 25 |

| 10 | Development studies | 23 |

| Year | Number of Records | % | Variation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 201 | 10.2% | - |

| 2013 | 189 | 9.6% | −6.0% |

| 2014 | 189 | 9.6% | 0.0% |

| 2015 | 218 | 11.1% | 15.3% |

| 2016 | 176 | 8.9% | −19.3% |

| 2017 | 170 | 8.6% | −3.4% |

| 2018 | 211 | 10.7% | 24.1% |

| 2019 | 206 | 10.5% | −2.4% |

| 2020 | 195 | 9.9% | −5.3% |

| 2021 | 216 | 11.0% | 10.8% |

| TOTAL | 1971 | 100.0% |

| Documents Type | Number of Records |

|---|---|

| Article | 1457 |

| Book chapter | 295 |

| Reviews | 149 |

| Books | 70 |

| # | Authors | Pub. Year | Article | Content | Journal | Cited |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Deakin, Simon Wilkinson, Frank | 2012 | The Law of the Labour Market: Industrialization, Employment, and Legal Evolution | This book analyses the evolution of the labour market and the employment contract in Britain through a thorough investigation of the changes in its legal form during and since the industrial revolution. In particular, the book addresses the influence of collective bargaining and social legislation on the standardisation of such important aspects as the conceptualisation of the modern labour market today. In turn, the book analyses the ways in which current proposals for the employment model should be addressed in the face of intensifying technological and institutional change. | The Law of the Labour Market: Industrialization, Employment, and Legal Evolution | 152 |

| 2 | Elfström, Manfred Kuruvilla, Sarosh | 2014 | The changing nature of labor unrest in China | This study deals with the reforms that are taking place in the Chinese labor market because of workers’ protests and strikes. Especially how the general framework of collective bargaining is evolving in the Asian giant. | ILR Review | 95 |

| 3 | Breman, Jan van der Linden, Marcel | 2014 | Informalizing the economy: The return of the social question at a global level | Evolution and future development of the concept of collective bargaining based on a new interpretation of the working-class concept. | Development and Change | 89 |

| 4 | Vernon, Raymond | 2014 | The location of economic activity | This paper makes a particular analysis of multinational companies, pointing out that their most salient characteristics are their size and their decentralisation. Decentralisation can point not only to geographical location, but also to management policies and techniques. In this respect, there are various facets to the characteristics of collective bargaining in this type of enterprise. Thus, among other factors, this paper presents a comparative analysis of firms’ capacity to pay and their bargaining power. | Economic Analysis and Multinational Enterprise | 84 |

| 5 | Chan, Chris King Chi Hui, Elaine Sio Ieng | 2014 | The development of collective bargaining in China: From collective bargaining by riot to party state-led wage bargaining | To examine the effect of labour strikes on the development of collective bargaining in China. | China Quarterly | 84 |

| 6 | Marginson, Paul M. | 2015 | Coordinated bargaining in Europe: From incremental corrosion to frontal assault? | The way in which collective bargaining, as an institution regulating industrial relations, has been shaped in Europe towards a more decentralised approach to the detriment of multi-employer agreements. | European Journal of Industrial Relations | 78 |

| 7 | Donaghey, Jimmy Reinecke, Juliane Niforou, Christina Lawson, Benn | 2014 | From Employment Relations to Consumption Relations: Balancing Labor Governance in Global Supply Chains | This article proposes an analytical framework conceptualizing the interface of employment relations and consumption relations within global supply chains, identifying four regimes of labour governance: governance gaps, collective bargaining, standards markets, and complementary regimes. | Human Resource Management | 78 |

| 8 | Miles, Sandra Jeanquart Mangold, W. Glynn | 2014 | Employee voice: Untapped resource or social media time bomb? | Worker participation in the enterprise and as part of this collective bargaining can be targeted and managed for strategic advantage when organisations provide the right organisational context together with appropriate mechanisms for employees. | Business Horizons | 75 |

| 9 | Ibsen, Christian Lyhne Tapia, Maite | 2017 | Trade union revitalisation: Where are we now? Where to next? | This article reviews and evaluates research on the role of trade unions in labour markets and society, the current decline in trade unions and trade union revitalisation. | Journal of Industrial Relations | 72 |

| 10 | Doellgast, Virginia L. | 2012 | Disintegrating democracy at work: Labor unions and the future of good jobs in the service economy | This book discusses how moving from a manufacturing-based economy to a service economy must be accompanied by improvements in wages and good working conditions for service sector workers. But this transition depends on the existence of strong trade unions and all-encompassing collective bargaining institutions needed to give workers a voice in decisions affecting the design of their jobs and the distribution of productivity gains. | Disintegrating Democracy at Work: Labor Unions and the Future of Good Jobs in the Service Economy | 66 |

| Position | Authors | Documents Published | H-Index | Sex | University | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pulignano, Valeria | 12 | 17 | Woman | KU Leuven | Belgic |

| 2 | Addison, John T. | 11 | 26 | Man | University of South Carolina | United States |

| 3 | Schulten, Thorsten | 10 | 10 | Man | University of Tübingen | Germany |

| Teixeira, Paulino | 13 | Man | University of Coimbra | Portugal | ||

| 4 | Marginson, Paul | 9 | 26 | Man | University of Warwick | England |

| Bellmann, Lutz | 16 | Man | University of Erlangen | Germany | ||

| Ibsen, Christian Lyhne | 12 | Man | University of Copenhagen | Denmark | ||

| 5 | Forsyth, Anthony | 8 | 5 | Man | RMIT University | Australia |

| Heery, Edmund | 24 | Man | Cardiff University | Wales | ||

| Brandl, Bernd | 13 | Man | Durham University | England | ||

| Marianno, Bradley D. | 8 | Man | University of Nevada | United States | ||

| Gahan, Peter | 14 | Man | University of Melbourne | Australia | ||

| Bosch, Gerhard | 19 | Man | University of Duisburg-Essen | Germany | ||

| Glassner, Vera | 8 | Woman | Chamber of Labour | Austria | ||

| Keller, Berndt Karl | 10 | Man | University of Konstanz | Germany |

| Position | Journal | #TD | CiteScore 2020 | H-Index | BQ | Publisher |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | European Journal of Industrial Relations | 56 | 2.5 | 43 | Q1 | Sage |

| 2 | Journal of Industrial Relations | 55 | 3.5 | 29 | Q1 | Sage |

| 3 | Economic and Industrial Democracy | 52 | 3.4 | 40 | Q1 | Sage |

| Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research | 4.1 | 23 | Q1 | Sage | ||

| 4 | ILR Review | 39 | 5.6 | 78 | Q1 | Sage |

| 5 | Industrielle Beziehungen | 38 | 0.4 | 10 | Q2 | Verlag Barbara Budrich |

| 6 | British Journal of Industrial Relations | 37 | 3.8 | 70 | Q1 | Wiley |

| 7 | Employee Relations | 35 | 2.8 | 52 | Q2 | Emerald |

| 8 | Labor History | 29 | 0.3(1) | 20 | Q1 | Taylor & Francis |

| 9 | Lavoro e Diritto | 22 | 0.4 | 8 | Q3 | Il Mulino Publishing House |

| 10 | Trabajo y Derecho | 21 | 0.16 | 2 | Q4 | Wolters Kluwer |

| Position | Research Areas | Documents Published |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Social sciences | 963 |

| 2 | Business, management and accounting | 945 |

| 3 | Economics, econometrics and finance | 481 |

| 4 | Arts and humanities | 184 |

| 5 | Medicine | 98 |

| 6 | Environmental science | 38 |

| 7 | Nursing | 32 |

| 8 | Engineering | 31 |

| 9 | Psychology | 29 |

| 10 | Agricultural and biological sciences | 17 |

| Authors | Pub. Year | Article | Journal | Database Cited | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breman, Jan Van der Linden, Marcel | 2014 | Informalizing the Economy: The Return of the Social Question at a Global Level | Development and Change | WoS-CC | 99 |

| Scopus | 89 | ||||

| Chan, Chris King-Chi Hui, Elaine Sio-Ieng | 2014 | The Development of Collective Bargaining in China: From Collective Bargaining by Riot to Party State-led Wage Bargaining | China Quarterly | WoS-CC | 91 |

| Scopus | 84 | ||||

| Donaghey, Jimmy Reinecke, Juliane Niforou, Christina Lawson, Benn | 2014 | From employment relations to consumption relations: balancing labor governance in global supply chains | Human Resource Management | WoS-CC | 70 |

| Scopus | 78 | ||||

| Miles, Sandra Jeanquart Mangold, W. Glynn | 2014 | Employee voice: Untapped resource or social media time bomb? | Business Horizons | WoS-CC | 65 |

| Scopus | 75 | ||||

| Marginson, Paul | 2015 | Coordinated bargaining in Europe: From incremental corrosion to frontal assault? | European Journal of Industrial Relations | WoS-CC | 91 |

| Scopus | 78 | ||||

| Ibsen, Christian Lyhne Tapia, Maite | 2017 | Trade union revitalisation: Where are we now? Where to next? | Journal of Industrial Relations | WoS-CC | 67 |

| Scopus | 72 | ||||

| Authors | Sex | Affiliation | Country |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breman, Jan | Man | University of Amsterdam | Netherlands |

| van der Linden, Marcel | Man | University of Amsterdam | Netherlands |

| Marginson, Paul | Man | University of Warwick | United States |

| Chan, Chris King-Chi | Man | Chinese University of Hong Kong | Hong Kong |

| Hui, Elaine Sio-Ieng | Woman | Pennsylvania State University | United States |

| Donaghey, Jimmy | Man | University of South Australia | Australia |

| Reinecke, Juliane | Woman | King’s College London | United Kingdom |

| Niforou, Christina | Woman | University of Birmingham | United Kingdom |

| Lawson, Benn | Man | Cambridge Judge Business School | United Kingdom |

| Ibsen, Christian Lyhne | Man | Michigan State University | United States |

| Tapia, Maite | Woman | Michigan State University | United States |

| Miles, Sandra Jeanquart | Woman | Murray State University | United States |

| Mangold, W. Glynn | Man | Murray State University | United States |

| Title | Publisher | JCR Category | Scopus Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| European Journal of Industrial Relations | Sage | Industrial relations and labor | Business, Management and Accounting. Management of Technology and Innovation. Organizational Behavior and HRM. Strategy and Management. |

| Journal of Industrial Relations | Sage | Industrial relations and labor | Business and International Management. Industrial Relations. |

| Transfer, The European Review of Labour and Research | Sage | Industrial relations and labor | Industrial Relations. Organizational Behavior and HRM |

| Economic and Industrial Democracy | Sage | Industrial relations and labor | General Business, Management and Accounting. Organizational Behavior and HRM Strategy and Management. Management of Technology and Innovation. |

| British Journal of Industrial Relations | Wiley | Industrial relations and labor | General Business, Management and Accounting. Organizational Behavior and HRM Management of Technology and Innovation. |

| ILR Review | Sage | Industrial relations and labor | Organizational Behavior and HRM Strategy and Management. Management of Technology and Innovation. |

| Employee Relations | Emerald | Industrial relations and labor. Management. | Industrial Relations. Organizational Behavior and HRM |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rueda-López, R.; Muñoz-Doyague, M.F.; Aja-Valle, J.; Vázquez-García, M.J. A Bibliometric Analysis of Collective Bargaining: The Future of Labour Relations after the COVID-19 Pandemic. Economies 2023, 11, 275. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies11110275

Rueda-López R, Muñoz-Doyague MF, Aja-Valle J, Vázquez-García MJ. A Bibliometric Analysis of Collective Bargaining: The Future of Labour Relations after the COVID-19 Pandemic. Economies. 2023; 11(11):275. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies11110275

Chicago/Turabian StyleRueda-López, Ramón, María F. Muñoz-Doyague, Jaime Aja-Valle, and María J. Vázquez-García. 2023. "A Bibliometric Analysis of Collective Bargaining: The Future of Labour Relations after the COVID-19 Pandemic" Economies 11, no. 11: 275. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies11110275

APA StyleRueda-López, R., Muñoz-Doyague, M. F., Aja-Valle, J., & Vázquez-García, M. J. (2023). A Bibliometric Analysis of Collective Bargaining: The Future of Labour Relations after the COVID-19 Pandemic. Economies, 11(11), 275. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies11110275