If You Aim Higher Than You Expect, You Could Reach Higher Than You Dream: Leadership and Employee Performance

Abstract

:1. Introduction

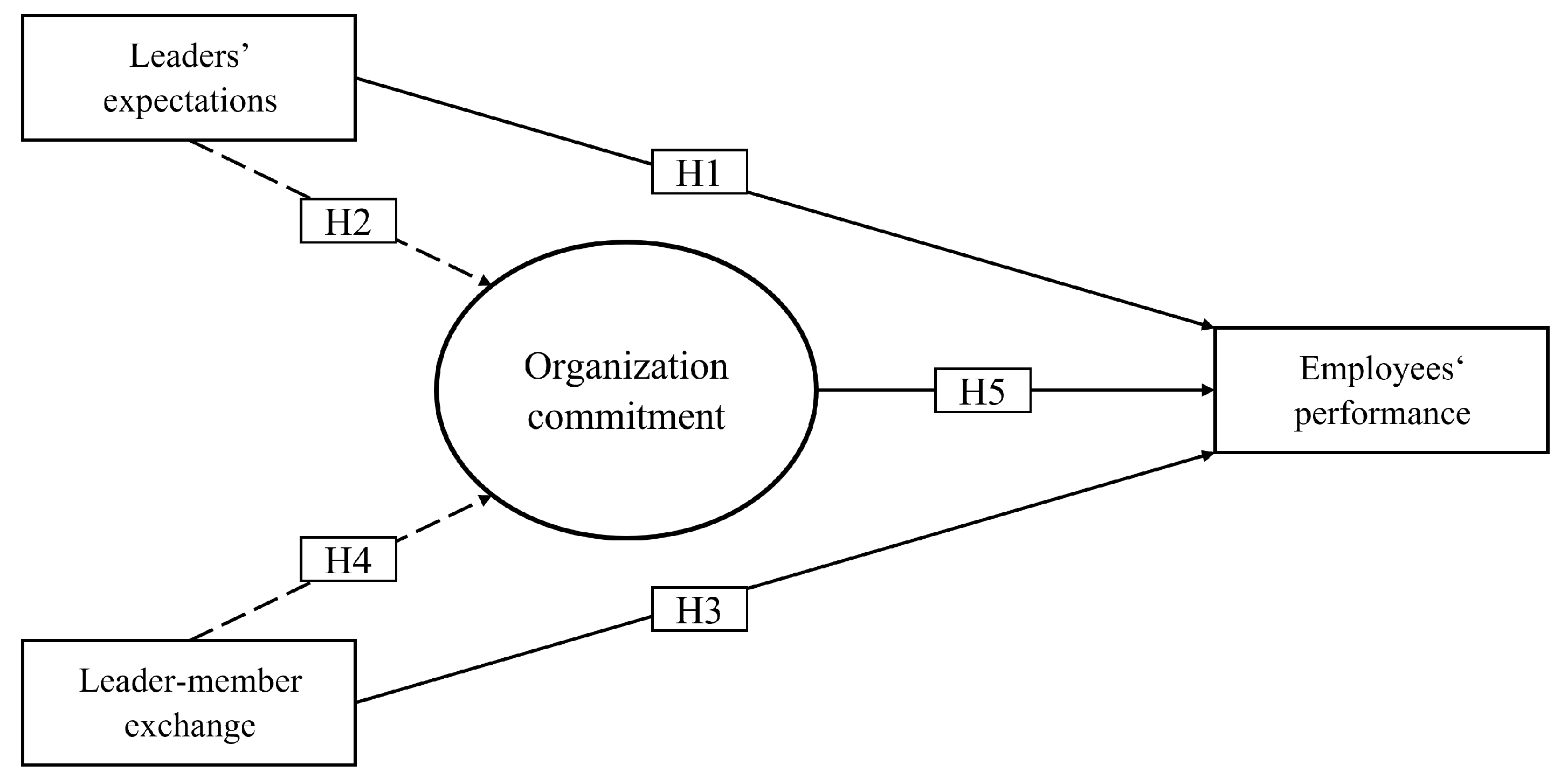

2. Literature Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Leader Expectations (Pygmalion Effect)

2.2. Leader-Member Exchange

2.3. Organizational Commitment and Employee Performance

3. Data and Methodology

- employee performance (EP), including five measures of the productivity level (related to high quality, excess, intention, intentions to perform task of work and high level of performance) similar to Shahzad et al. (2018),

- organizational commitment (OC), covering six items as in study by Meyer et al. (1993),

- leader’s expectations (LE), with three items adapted from Tierney and Farmer (2004) and

- leader-member exchange (LMX), covering seven items from Scandura and Schriesheim (1994).

4. Results

4.1. Pilot Test

4.2. Data Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Atitumpong, Atitumpong, and Yuosre F. Badir. 2018. Leader-member exchange, learning orientation and innovative work behavior. Journal of Workplace Learning 30: 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, Hakan. 2020. Market orientation and product innovation: The mediating role of technological capability. European Journal of Innovation Management 24: 1233–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, Monica Y., Paul Condon, Jourdan Cruz, Jolie Baumann Wormwood, and David Desteno. 2012. Gratitude: Prompting behaviours that build relationships. Cognition & Emotion 26: 2–13. [Google Scholar]

- Bordia, Prashant, Simon Lloyd D. Restubog, Sarbari Bordia, and Robert L. Tang. 2010. Breach begets breach: Trickle-down effects of psychological contract breach on customer service. Journal of Management 36: 1578–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordia, Prashant, Simon Lloyd D. Restubog, Sarbari Bordia, and Robert L. Tang. 2017. Effects of resource availability on social exchange relationships: The case of employee psychological contract obligations. Journal of Management 43: 1447–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockner, Joel. 1988. The effects of work layoffs on survivors: Research, theory, and practice. Research in Organizational Behavior 10: 213–55. [Google Scholar]

- Cascio, Wayne F. 2003. Managing Human Resources: Productivity, Quality of Work Life, Profits, 6th ed. New York: Irwin & McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Jie. 2011. A Case Study of the “Pygmalion Effect”: Teacher Expectations and Student Achievement. International Education Studies 4: 198–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cole, Michael S., William S. Schaninger Jr., and Stanley G. Harris. 2002. The workplace social exchange network: A multilevel, conceptual examination. Group & Organization Management 27: 142–67. [Google Scholar]

- De Jong, Jeroen P.J., Sharon K. Parker, Sander Wennekers, and C. Wu. 2011. Corporate entrepreneurship at the individual level: Measurement and determinants. EIM Research Reports. Zoetermeer: EIM 11: 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Dhamija, Pavitra, Shivam Gupta, and Surajit Bag. 2019. Measuring of job satisfaction: The use of quality of work life factors. Benchmarking: An International Journal 26: 871–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Jinyun, Chenwei Li, Yue Xu, and Chia-huei Wu. 2017. Transformational leadership and employee voice behavior: A Pygmalion mechanism. Journal of Organizational Behavior 38: 650–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eden, Dov. 1984. Self-fulfilling prophecy as a management tool: Harnessing Pygmalion. Academy of management Review 9: 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, Robert M. 1976. Social exchange theory. Annual Review of Sociology 2: 335–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farh, Crystal IC, Klodiana Lanaj, and Remus Ilies. 2017. Resource-based contingencies of when team–member exchange helps member performance in teams. Academy of Management Journal 60: 1117–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrukh, Muhammad, Jason Wai Chow Lee, and Imran Ahmed Shahzad. 2019. Intrapreneurial behavior in higher education institutes of Pakistan: The role of leadership styles and psychological empowerment. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education 11: 273–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrukh, Muhammad, Wei Ying Chong, Shaheen Mansori, and Sara Ravan Ramzani. 2017. Intrapreneurial behaviour: The role of organizational commitment. World Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development 13: 243–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, Alena, Barbara Flunger, Benjamin Nagengast, Kathrin Jonkmann, and Ulrich Trautwein. 2015. Pygmalion effects in the classroom: Teacher expectancy effects on students’ math achievement. Contemporary Educational Psychology 41: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, Donald G., and Jon L. Pierce. 1998. Self-esteem and self-efficacy within the organizational context: An empirical examination. Group & Organization Management 23: 48–70. [Google Scholar]

- Goddard, Robert W. 1985. The Pygmalion effect. Personnel Journal 64: 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Graen, George B. 1976. Role-making processes within complex organizations. In Handbook of Industrial And Organizational Psychology. Edited by Marvin D. Dunnette. Chicago: Rand McNally, pp. 1201–45. [Google Scholar]

- Grošelj, Matej, Matej Černe, Sandra Penger, and Barbara Grah. 2020. Authentic and transformational leadership and innovative work behaviour: the moderating role of psychological empowerment. European Journal of Innovation Management 24: 677–06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph F., Jeffrey J. Risher, Marko Sarstedt, and Christian M. Ringle. 2019. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review 31: 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph F., Marko Sarstedt, Christian M. Ringle, and Siegfried P. Gudergan. 2017. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling. Thousand Oak: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Huynh, Tan, Minh Hon Duong, Thuy Thanh Phan, Tu Van Do, Truc Thi Thanh Do, and Khai The Nguyen. 2019. Team dynamics, leadership, and employee proactivity of Vietnamese firms. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 5: 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johanson, George A., and Gordon P. Brooks. 2010. Initial scale development: sample size for pilot studies. Educational and Psychological Measurement 70: 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jolliffe, Ian T., and Jorge Cadima. 2016. Principal component analysis: A review and recent developments. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 374: 20150202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joo, Baek-Kyoo, and Taejo Lim. 2009. The effects of organizational learning culture, perceived job complexity, and proactive personality on organizational commitment and intrinsic motivation. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies 16: 48–60. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, Henry F. 1974. An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika 39: 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. Riaz, ia-ud-Din, Jam F. Ahmed, and Ramay M. Ismail. 2010. The impacts of organizational commitment on employee job performance. European Journal of Social Sciences 15: 292–98. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Muhammad Mumtaz, Muhammad Shujaat Mubarik, and Tahir Islam. 2020. Leading the innovation: Role of trust and job crafting as sequential mediators relating servant leadership and innovative work behavior. European Journal of Innovation Management 24: 1547–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Naveed Ahmad. 2022. To Win in the Market Place You Must First Win in the Workplace: An Empirical Evidence from Banking Sector. Ph.D. thesis, BTU Cottbus-Senftenberg, Brandenburg, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Kierein, Nicole M., and Michael A. Gold. 2000. Pygmalion in work organizations: A meta-analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior 21: 913–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlowski, Steve W., and Mary L. Doherty. 1989. Integration of climate and leadership: Examination of a neglected issue. Journal of Applied Psychology 74: 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, Dora C., and Robert C. Liden. 2008. Antecedents of coworker trust: Leaders’ blessings. Journal of Applied Psychology 93: 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenka, Usha, and Minisha Gupta. 2019. An empirical investigation of innovation process in Indian pharmaceutical companies. European Journal of Innovation Management 23: 500–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likert, Rensis. 1967. The Human Organization: Its Management and Values. New York: McGraw Hill Higher Education. [Google Scholar]

- Livingston, J. Sterling. 1969. Pygmalion in management. Harvard Business Review 47: 81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra, Naresh K., Sung S. Kim, and Ashutosh Patil. 2006. Common method variance in IS research: A comparison of alternative approaches and a reanalysis of past research. Management Science 52: 1865–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, John P., Natalie J. Allen, and Catherine A. Smith. 1993. Commitment to organizations and occupations: Extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. Journal of Applied Psychology 78: 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossholder, Kevin W., Arthur G. Bedeian, and Achilles A. Armenakis. 1981. Role perceptions, satisfaction, and performance: Moderating effects of self-esteem and organizational level. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance 28: 224–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumford, Michael D., Ginamarie MScott, Blaine Gaddis, and Jill MStrange. 2002. Leading creative people: Orchestrating expertise and relationships. The Leadership Quarterly 13: 705–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmah, Mirhamida, and Dinda Fatmah. 2018. Organizational culture and intrapreneurship employee of the impact on work discipline of employees in brangkal offset. Jurnal Ilmu Manajemen Dan Bisnis 10: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmond, Matthew R., Michael D. Mumford, and Richard Teach. 1993. Putting creativity to work: Effects of leader behavior on subordinate creativity. Organizational Behavior And Human Decision Processes 55: 120–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigtering, J. P. Coen, and Utz Weitzel. 2013. Work context and employee behaviour as antecedents for intrapreneurship. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 9: 337–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scandura, Terri A., and Chester A. Schriesheim. 1994. Leader-member exchange and supervisor career mentoring as complementary constructs in leadership research. Academy of Management Journal 37: 1588–602. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, Susanne G., and Reginald A. Bruce. 1994. Determinants of innovative behavior: A path model of individual innovation in the workplace. Academy of Management Journal 37: 580–607. [Google Scholar]

- Shahzad, Imran Ahmed, Muhammad Farrukh, Nagina Kanwal, and Ali Sakib. 2018. Decision-making participation eulogizes probability of behavioral output; job satisfaction, and employee performance (evidence from professionals having low and high levels of perceived organizational support). World Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development 14: 321–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, Nupur, and Kailash B. L. Srivastava. 2013. Association of personality, work values and socio-cultural factors with intrapreneurial orientation. The Journal of Entrepreneurship 22: 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Charvert, and G. Meyer. 2009. The Good Perspective Theory for Commitment Organization. Athens: Ohio University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, Karoline, Mark A. Griffin, and Alannah E. Rafferty. 2009. Proactivity directed toward the team and organization: The role of leadership, commitment and role-breadth self-efficacy. British Journal of Management 20: 279–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Suliman, Abubakr MT. 2002. Is it really a mediating construct? The mediating role of organizational commitment in work climate-performance relationship. Journal of Management Development 21: 170–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surucu, Lutfi, and Harun Sesen. 2019. Entrepreneurial behaviors in the hospitality industry: Human resources management practices and leader member exchange role. Revista de Cercetare si Interventie Sociala 66: 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, Charlotte D., and Richard W. Woodman. 1989. Pygmalion goes to work: The effects of supervisor expectations in a retail setting. Journal of Applied Psychology 74: 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, Pamela, and Steven M. Farmer. 2004. The Pygmalion process and employee creativity. Journal of Management 30: 413–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, Pamela, Steven M. Farmer, and George B. Graen. 1999. An examination of leadership and employee creativity: The relevance of traits and relationships. Personnel Psychology 52: 591–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hemmen, Stefan, Claudia Alvarez, Marta Peris-Ortiz, and David Urbano. 2015. Leadership styles and innovative entrepreneurship: An international study. Cybernetics and Systems 46: 271–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, Fred O., John J. Lawler, and Bruce J. Avolio. 2007. Leadership, individual differences, and work-related attitudes: A cross-culture investigation. Applied Psychology 56: 212–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, Hyung Rok. 2018. Personality traits and intrapreneurship: The mediating effect of career adaptability. Career Development International 23: 145–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Items | Factor Loadings | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employee performance | EP1 | 0.898 | 0.949 | 0.788 |

| EP2 | 0.874 | |||

| EP3 | 0.884 | |||

| EP4 | 0.896 | |||

| EP5 | 0.886 | |||

| Organizational commitment | OC1 | 0.884 | 0.967 | 0.831 |

| OC2 | 0.927 | |||

| OC3 | 0.908 | |||

| OC4 | 0.910 | |||

| OC5 | 0.930 | |||

| OC6 | 0.910 | |||

| Leaders’ expectations | LE1 | 0.899 | 0.937 | 0.832 |

| LE2 | 0.912 | |||

| LE3 | 0.925 | |||

| Leader-member exchange | LMX1 | 0.826 | 0.942 | 0.700 |

| LMX2 | 0.851 | |||

| LMX3 | 0.890 | |||

| LMX4 | 0.885 | |||

| LMX5 | 0.854 | |||

| LMX6 | 0.764 | |||

| LMX7 | 0.871 |

| HTMT Ratio | EP | LMX | LE | OC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employee performance | ||||

| Leader-member exchange | 0.794 | |||

| Leaders’ expectations | 0.722 | 0.654 | ||

| Organizational commitment | 0.839 | 0.771 | 0.803 | |

| Fornell-Larcker Criterion | EP | LMX | LE | OC |

| Employee performance | 0.888 | |||

| Leader-member exchange | 0.741 | 0.837 | ||

| Leaders’ expectations | 0.662 | 0.597 | 0.912 | |

| Organizational commitment | 0.795 | 0.731 | 0.747 | 0.912 |

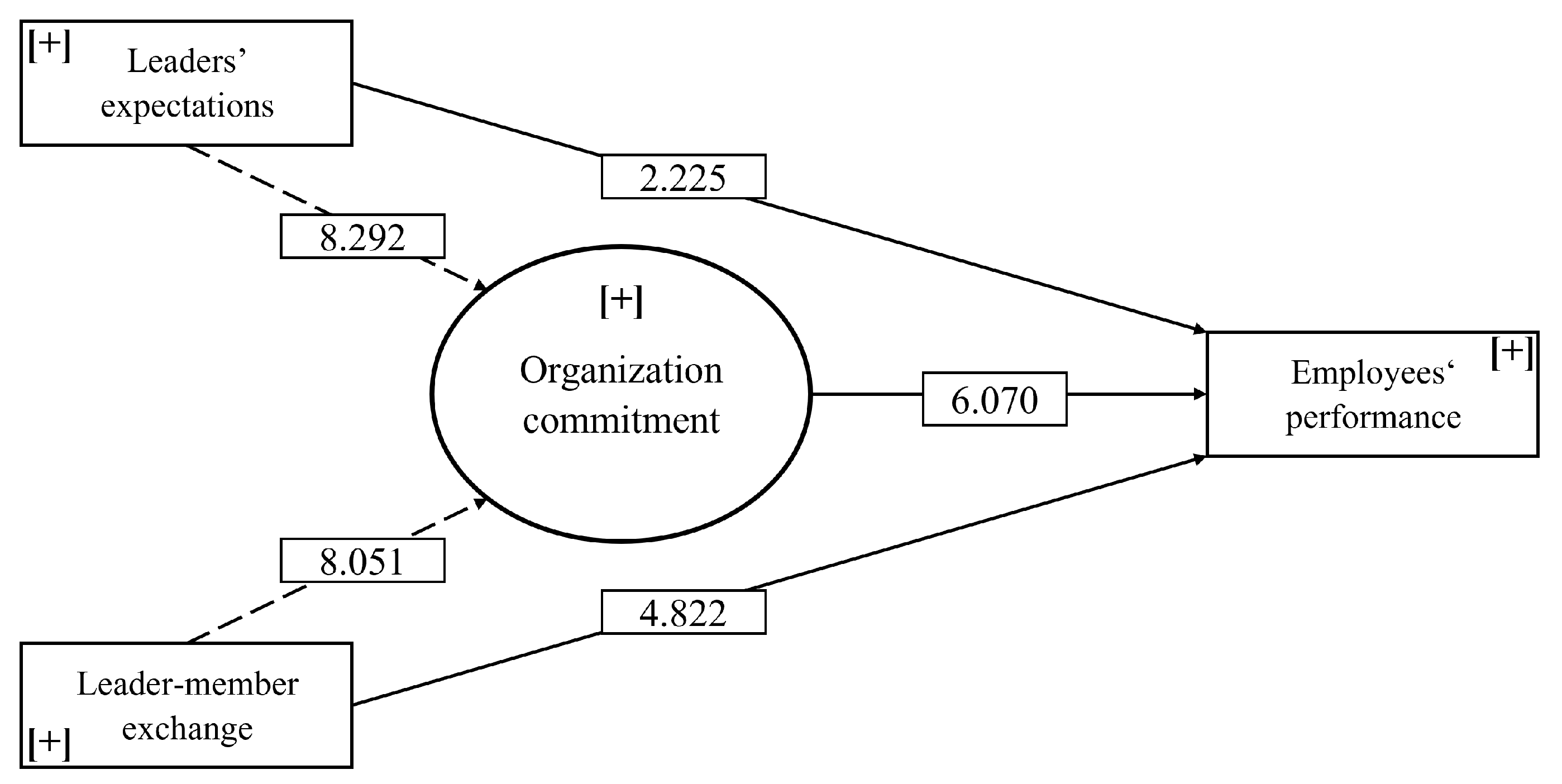

| Hypothesis | Mean | SD | T-Value | p-Value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LE >> EP | 0.115 | 0.052 | 2.225 | 0.027 | 0.338 | 0.546 |

| LE >> OC | 0.480 | 0.058 | 8.292 | 0.000 | 0.013 | 0.217 |

| LMX >> EP | 0.336 | 0.069 | 4.822 | 0.000 | 0.206 | 0.470 |

| LMX >> OC | 0.447 | 0.055 | 8.051 | 0.000 | 0.338 | 0.546 |

| OC >> EP | 0.464 | 0.077 | 6.070 | 0.000 | 0.309 | 0.602 |

| Organizational commitment mediation | ||||||

| LE >> OC >> EP | 0.223 | 0.050 | 4.490 | 0.000 | 0.135 | 0.325 |

| LMX >> OC >> EP | 0.226 | 0.040 | 5.185 | 0.000 | 0.132 | 0.287 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khan, N.A.; Michalk, S.; Sarachuk, K.; Javed, H.A. If You Aim Higher Than You Expect, You Could Reach Higher Than You Dream: Leadership and Employee Performance. Economies 2022, 10, 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies10060123

Khan NA, Michalk S, Sarachuk K, Javed HA. If You Aim Higher Than You Expect, You Could Reach Higher Than You Dream: Leadership and Employee Performance. Economies. 2022; 10(6):123. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies10060123

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhan, Naveed Ahmad, Silke Michalk, Kirill Sarachuk, and Hafiz Ali Javed. 2022. "If You Aim Higher Than You Expect, You Could Reach Higher Than You Dream: Leadership and Employee Performance" Economies 10, no. 6: 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies10060123

APA StyleKhan, N. A., Michalk, S., Sarachuk, K., & Javed, H. A. (2022). If You Aim Higher Than You Expect, You Could Reach Higher Than You Dream: Leadership and Employee Performance. Economies, 10(6), 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies10060123