Abstract

This study provides an empirical analysis of the two macroprudential instruments, namely the reserve option mechanism and the interest rate corridor, employed by the Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. A nine-variable structural vector autoregressive model for Turkey is estimated with Bayesian techniques utilising data from October 2010 to May 2018. A set of timing, zero and sign restrictions are imposed to identify the reserve requirement and the interest rate shocks through the bank lending channel. The results reveal that the new policy frame is efficient in curbing the volatility in the exchange rates and in improving the current account balance. While the reserve requirements seem to be more effective on the current account and partly on the exchange rate, the interest rate fares better in controlling the price level.

1. Introduction

Emerging countries have enjoyed ample capital flows from industrialised countries through financial globalisation since the 1980s so much so that international financial integration was regarded as a touchstone in the development of emerging countries (Obstfeld 2004). With deepening financial linkages, capital flows to emerging countries have increased even more so during the last two decades. However, financial globalisation is not a rose without the prick. Research documents that financial integration it increased the volatility of capital flows and the vulnerability of small open economies to financial crises (Grosse 2004; Martin and Rey 2006; Lane 2013). The Mexican crisis in 1994, the Asian Crisis in 1997, the Russian Crisis in 1998, the Argentine crisis in 2001 and the Turkish crises in 1994 and 2001 are among the notable financial crises resulting from volatile capital flows (Mishkin 1999, 2001). It would not be an overstatement to assert that financial crises in emerging countries resulting from volatile capital flows are rampant in the history of financial globalisation (Mendoza 2006).

Financial crises have occurred almost periodically in recent decades but the global financial crisis of 2008 exhibits a turning point in the central banking practises of both advanced and emerging countries. In order to promote spending, pioneered mainly by the Fed and the ECB, the policy rate was lowered almost to zero and the balance sheet size of central banks grew incrementally in advanced economies as a consequence of quantitative easing (IMF 2013a, 2013b, 2013c). Capital flows from advanced countries to emerging economies increased substantially, being mostly short-term and volatile in nature, due to the policy uncertainties in advanced countries at the time (Basci and Kara 2011).

Large and volatile capital flows, if not managed accordingly, trigger excessive credit growth and increase the risk of financial instability. Concentrated solely on inflation stabilisation and armed with the conventional interest rate tool, the ordinary response of the central banks of raising interest rates does not stop the credit boom but rather attracts more capital. As a response, the domestic currency appreciates, the improved balance sheet of borrowers promotes further expansion in credits, the current account balance deteriorates and, in turn, macroeconomic instability worsens (Calvo 1998; Mendoza and Terrones 2008; Bruno and Shin 2013, 2014). In this regard, the reserve requirements made a flash return to the stage as a macroprudential tool in order to tighten credit conditions without attracting more capital, especially in emerging economies, such as Brazil, Croatia, Russia and Turkey (Lim et al. 2011).

After being hit heavily by the crisis and experiencing a 15 percent contraction in 2009, the Turkish economy experienced a dramatic increase in capital flows in the following years, owing to quick economic recovery and strong domestic demand (Kara 2012). Not surprisingly, the outcome was an expansion in domestic credit, an excessively appreciated currency and a deteriorated current account.

Amid increasing macro financial concerns towards the end of 2010, the CBRT announced a change in its policy stance and mentioned the use of alternative policy instruments for the first time. First, it stopped paying remuneration for the required reserves and started to use the reserve requirement ratio actively to contain the risk of credit growth. Later, it designed the Reserve Option Mechanism (ROM) (Alper et al. 2012) aimed at stabilising the exchange rates. Second, the CBRT announced the one-week repo as the main policy instrument for funding, while the overnight borrowing and lending rates functioned as the lower and upper bound of the interest rate corridor (Basci and Kara 2011; Kara 2015). The interest rate corridor was mainly aimed at controlling the short-term speculative capital flows.

The operational framework of the two new policy tools is summarised below. The ROM allows banks to hold a certain fraction of their Turkish lira reserve requirements in foreign currency or, as implemented later, in gold. During periods of excessive capital inflow, banks can increase their use of ROM and hold foreign currency in place of TL reserve requirements up to a certain threshold. On the other hand, they are allowed to decrease the use of ROM during the capital outflow periods. So, the ROM is a market-friendly mechanism which helps to stabilise the volatility in the exchange rates. The other novel tool, the interest rate corridor, works principally by creating an uncertainty zone between the lending (upper bound) and the borrowing (lower bound) rates of the central banks. Reducing the lower limit of the corridor during the capital inflow periods discourages the foreign capital, while increasing the limit during the capital outflow periods holds its surge. Therefore, the corridor maintains the smoothing of foreign capital flow. The main incentive of the CBRT in employing these additional tools was to increase the resistance of the economy against volatile capital flows, therefore containing the credit growth and maintaining the external balance (Kara 2012; Oduncu et al. 2013; Aysan et al. 2014).

In this study, we provide some empirical evidence on whether the new policy mix, in particular the reserve option mechanism (ROM), has been successful in containing the key macroeconomic variables such as domestic credit conditions, the external balance, the exchange rate and domestic inflation and in promoting macroeconomic activity. Turkey constitutes a splendid example for this study: first, it is one of the hardest hit countries by the crisis. Second, it devised the monetary policy and started to implement two novel monetary policy tools right after the crisis. Third, it has a long history of homogeneous monetary policy practice since 2000 (beginning of inflation targeting regime). The homogeneous monetary policy period is important for empirical research because the reserve requirements would have different effects if the central bank had different targets other than interest rates (Glocker and Towbin 2015).

The outline of the study is as follows: Section 2 reviews the related literature. Section 3 introduces the data and the methodology. In Section 4, we present our main empirical findings including impulse response functions and forecast error variance decompositions. Section 5 discusses the results and Section 6 concludes.

2. Literature Review

The global financial crisis sparked by the subprime mortgage crisis in the US resulted in quantitative easing (QE) in many large economies. Interest rates in several countries approached the Zero Lower Bound (ZLB), which drove central banks to consider macroprudential policies (Kahou and Lehar 2017; Mester 2017). Papadamou et al. (2020) provide a recent review of the literature that burgeoned in this time period.

Quantitative easing policies by advanced economies constitute the bulk of this literature. The reader is referred to Martin and Milas (2012) for an early and Thornton (2017) for a more recent review. The spill-over effects on emerging countries have also received significant attention as many emerging economies experienced financial instability due to large and volatile capital flows as a direct consequence of QE in advanced economies. Bhattarai et al. (2021) show that QE policies have increased capital flows to emerging countries and especially to the Fragile Five group which Turkey belongs to. Belke and Fahrholz (2018) and Bartkiewicz (2018) review the empirical literature on the spill-over effects on QE policies on emerging economies. Turkey was one of the recipients of large capital inflows and responded by initiating a new monetary policy framework utilising macroprudential instruments. However, according to Lombardi and Siklos (2016), Turkey did not present a strong capacity to deploy macroprudential policies.

Reserve requirements are one of the macroprudential instruments utilised by the monetary authority of Turkey as well as of other advanced or emerging countries. Curdia and Woodford (2011), for instance, study the contribution of reserve remuneration under the zero lower bound. Kashyap and Stein (2012) analyse the role of reserve requirements in search of an optimal monetary policy and its use as a financial stability tool. Both studies are on advanced economies and suggest that the reserve requirement has re-emerged as a financial stability tool in the post crisis period. Studies on emerging countries mostly focus on the behaviour of the banking sector, such as the impact of reserve requirements on the banking spreads and the credit growth (Herrera et al. 2011; Glocker and Towbin 2012; Tovar et al. 2012; Armas et al. 2014) and are lacking in the effects on other aggregate or external factors, such as GDP, unemployment, current account, or inflation. Alternatively, Glocker and Towbin (2015) provide a broadly-based analysis of reserve requirements and investigate the joint dynamics of the basic macroeconomic variables, which also motivates our study. Lubis et al. (2021) also investigate the effect of reserve requirements as a macroprudential instrument on macroeconomic variables of the Indonesian economy but employ a different methodology.

Reserve requirements as a macroprudential instrument in Turkey has also received the attention of scholars, especially in the first couple of years of the implementation of the new policy mix. The most notable examples are as follows: Alper et al. (2014) focus on the interaction between reserve requirements and the bank lending behaviour. Aslaner et al. (2015) and Oduncu et al. (2013) analyse the reserve requirement policy in Turkey by the reserve option mechanism (ROM) and both follow a partial equilibrium approach. Other papers explain the effectiveness of reserve requirements as a macroprudential tool. Among them, Sahin et al. (2015) emphasise the supportive effect of the ROM in controlling the capital flow and emphasise the complementary effect of reserve requirements in reducing the capital flows. Değerli and Fendoğlu (2015) prove its stabilising role on the excessive movements of the exchange rate. In a more recent study, Binici et al. (2019) employ reserve requirements as an additional variable in order to explain the private bank’s lending and borrowing behaviour rates during the QE period and underline the significance of reserve requirements on commercial loan and deposit rates.

Like the literature on emerging markets, the literature on Turkey has almost entirely focused on the effect of reserve requirements, as a macroprudential instrument, on the banking sector and short-term financial indicators. Varlık and Berument (2016) include industrial production and imports in their VAR and this constitutes an exception. However, the sample covers the period from January 1992 until May 2013 which cannot be characterised as a period of homogeneous monetary policy practice. Moreover, it only covers the initial period of macroprudential policy practice. Varlık and Berument (2017) investigate the effect of different monetary policy rates on economic performance including the upper and lower bounds of the interest rate corridor, which constitutes another exception. Our study is a contribution to this literature and complements it in two important ways. First, it is a contribution to the impact of macroprudential policy on the macroeconomy and not only on the banking or financial sector. In this sense, we contribute to the literature on macroprudential policy in emerging markets as well. Second, we analyse the entire period when the macroprudential mix was in place rather than focusing on the initial years and study both macroprudential instruments.

3. Data and Methodology

Macroeconomic variables usually have a contemporaneous relationship between endogenous variables, so the vector auto-regression (VAR) estimation in reduced form is incapable of revealing how the endogenous variables affect each other as the reduced form residuals are not orthogonal. The seminal work of Sims (1980) introduced the structural vector autoregressive (SVAR) framework to capture interdependencies between endogenous variables. Nevertheless, the SVAR model cannot be estimated directly because of the feedback effects from contemporaneous variables. The reduced-form VAR, on the other hand, contains predetermined time series and can be estimated. So, it is possible to start with a reduced-form model and retrieve the structural parameters and shocks by imposing identifying restrictions on the parameters in the coefficient and residual covariance matrices.

In order to estimate the model we used a Bayesian methodology. We imposed a set of timing, zero and sign restrictions in a nine-variable structural vector auto-regression (SVAR) system to identify the reserve requirement and the interest rate shocks. We followed the method introduced by Arias et al. (2014) by using the notation borrowed from Dieppe et al. (2016). We started by writing the reduced form of the estimated model as:

where, , , …, ) is an vector of endogenous variables, is an m × 1 vector of exogenous variables (constant terms, time trends, exogenous data series), is a reduced-form error term with variance covariance matrix , p is the lag length, , , …… are n × n coefficient matrices and is an n × m coefficient matrix.

Next, we specified the model in structural form.

is a vector of structural innovations with variance covariance matrix . For notational purpose define and pre-multiply both sides of Equation (2) by :

The one step ahead prediction error is where we looked to understand how structural shocks are transmitted through the economy. The method used to decompose into economically meaningful forms in order to understand this transmission mechanism deserves special attention. Equation (5) represents as a linear combination of orthonormal structural shocks = ., where suppose E() = In and is the impact matrix of each structural shock. In this representation serves as a structural matrix and helps to recover structural innovations from the reduced-form VAR residuals. In other words, the matrix shows the immediate response of endogenous variables to one standard error innovation in . The only restriction on the matrix comes from the form of the variance-covariance matrix:

This equation gives us as many as n(n − 1)/2 degrees of freedom in specifying matrix (given n2 elements of to identify, and n(n + 1)/2 restrictions from Σ, there remains n(n − 1)/2 restrictions to identify matrix). Since the current restrictions on matrix were not enough to identify the shocks to , we needed further restrictions on . As discussed in detail in Section 3.2, in order to identify the reserve requirement and the interest rate shocks, we applied a combination of sign and zero restrictions as proposed in Uhlig (2005) and followed the algorithm as presented in Arias et al. (2014).

3.1. Data

The CBRT started to employ macroprudential instruments in the last quarter of 2010 when the aftershock of the financial crisis started to come ashore in Turkey. Following an intense implementation of this multi-tooled monetary policy, as the global economic outlook started to normalise, the country announced its roadmap to simplify the monetary policy implementation in August 2015 (CBRT 2015). The main incentive of this simplification was to form a more predictable monetary policy to improve the expectations of the economic agents. As of May 2018, the CBRT completed the simplification period and the interest rate corridor was abolished. Moreover, the active use of the ROM has been diminished gradually, and the CBRT declared that it will end its usage in 20221 (CBRT 2018).

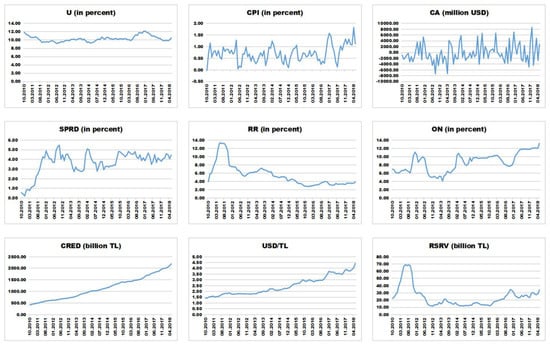

We used monthly data from October 2010 to May 2018, in which both instruments were actively used, in order to capture not only the effect of each policy instrument on the economy but also to analyse the interaction between them. While the time span does not seem to be very long, the period contains adequate data to judge the effectiveness of the new policy approach with Bayesian methodology. Besides, given our sample size, we formulated a SVAR model that could capture the effects of the reserve requirement policy shocks and the interest rate shocks with a minimum number of variables. The endogenous variables include unemployment (U), the consumer price index (CPI), the current account (CA), the spread between deposit and the lending rates (SPRD), the bank credits (CRED), the bank reserves (RSRV) and the exchange rate (USD) and two variables that are directly related to the new macro-prudential policy mix: a measure for the reserve requirement policy (RR) and the overnight interest rate (ON)2. The lag length was chosen as one based on the following standard tests for choice of lag length: Likelihood Ratio test (LR), the Final Prediction Error (FPE), Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Hannan-Quinn Information Criterion (HQ) and Schwarz Information Criterion (SC). At this lag length, the null hypothesis of no autocorrelation could not be rejected by the Lagrange Multiplier (LM) test. Based on the outcome of the seasonality tests3, the consumer price index, the current account and the real credit were seasonally adjusted with the Tramo/Seats method.

We included the volatility index (VIX), the Industrial Production Index for the European Union (IP), the commodity price index (CP) and the US Federal Funds rate (FED) as exogenous variables to capture the external effects on a small open economy, Turkey. The exogenous variables were entered into the model with two lags and the vector of exogenous variables also included a time trend as a deterministic variable.

We tested the stationarity of our variables and provided the unit root test results as Supplementary Materials. We conducted in total six unit root tests: Augmented Dickey Fuller (ADF) unit root test with an intercept and with or without a trend term, Phillips-Perron (PP) unit root test with an intercept and with or without a trend term and the Kwiatkowski–Phillips–Schmidt–Shin (KPSS) unit root test with an intercept and with or without a trend term. All six unit root tests unanimously found that CPI, domestic credit (CRED), reserves (RSRV), exchange rate (USD) and federal funds rate (FED) are nonstationary. The results of the rest of the variables were mixed. Even though the analysis employed nontionary macroeconomic data, we used all variables in levels as recommended in Sims (1980) and Sims et al. (1990), discussed in Enders (2010, p. 303). Fanchon and Wendel (1992), Christiano et al. (1999), Uhlig (2005) and Binatli and Sohrabji (2019) are examples of VARs with nonstationary macroeconomic variables in levels. Carriero et al. (2015) further analysed Bayesian VARs with possibly nonstationary macroeconomic variables in levels along the lines of Sims (1980) and concluded that modelling choices lead to very small losses in forecasting power, thus making BVARs a versatile econometric tool.

3.2. Identification of Structural Shocks

The main question here was how to formulate a reliable identification scheme. There are several methods of identification in the VAR literature. The recursive approach (Cholesky ordering) imposes short run restrictions on model parameters and assumes that the central bank does not influence the fast-moving variables in the short run (as implemented by Fatas and Mihov (2001) and Tovar et al. (2012)). The sign restriction approach imposes restrictions on impulse response functions (as in Mountford and Uhlig (2009) and Glocker and Towbin (2015)), whereas the narrative approach imposes restrictions on the structural parameters in line with the key historical events so as to ensure that the structural shocks represent those episodes (Federico et al. 2012; Antolín-Díaz and Rubio-Ramírez 2018; Rojas et al. 2020).

In our identification scheme, we imposed timing, zero and sign restrictions on impulse response functions to identify the reserve requirement shock and the interest rate shock. We followed economic theory and used exact identification, which resulted in more accurate impulse response functions and a unique D matrix for a given parameter estimate.

A positive reserve requirement shock will trigger an increase in bank reserves and in reserve requirements. The theory behind this reaction is that the central bank needs to increase the nominal reserves in order to compensate for the upward pressure of reserve requirements on the policy rate.

A positive interest rate shock on the other hand reflects an increase in prices and a reduction in bank reserves. The implementation of an interest rate rise is executed by withdrawing money, which results in lower reserves. We further propose that the price level responds negatively in the second period to eliminate the price puzzle (Sims 1992; Christiano and Eichenbaum 1992).4

In order to identify the two policy shocks of the CBRT, we followed Glocker and Towbin (2015) and defined a block of slow-moving variables which responded to policy shocks with delay. This block of slow-moving variables included unemployment, the price level and the current account. The fast-moving variables on the other hand responded to shocks within a month and included the nominal exchange rate, total credit, bank reserves and the spread. The timing (or zero) restrictions were imposed on the slow-moving variables for one month and the sign restrictions were imposed on the fast-moving variables for three months. Where there was not a consensus on the response of the variables, the response was left unrestricted and an agnostic approach was accepted; the impulse responses were determined by the estimated model. The identification restrictions are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Identification restrictions.

In order to impose the zero, timing and sign restrictions, we exploited the BEAR toolbox (Dieppe et al. 2016), which followed the same algorithm as presented in Arias et al. (2014). In Bayesian framework D is regarded as a random variable, like parameters of the VAR system. Therefore, the algorithm drew the impact matrix D from the posterior distribution of structural parameters conditional on zero restrictions and applied the QR decomposition D = QR. Each column of the Q matrix was selected recursively by standard normal distribution on Rn. The recursive selection of Q matrix proved that it was selected from a uniform distribution of the posterior of structural parameters conditional on zero restrictions. If the sign restrictions were satisfied the draw was kept. The procedure proceeded until the required number of draws was obtained. In our study, the algorithm worked until 1000 accepted draws were obtained.

The prior selection is another important stage of the Bayesian VAR analysis. Since the literature lacks adequate previous study using Bayesian techniques to analyse the reserve requirement and the interest rate policy in Turkey, there are no ready-to-use priors to rely on. Therefore, we employed the analysis for Minnesota prior, Normal-Wishart prior and Independent Normal-Wishart prior, which are the benchmark priors in Bayesian VAR. The analysis presented in this study is based on the Minnesota prior which assumes that each variable follows a random walk and thus is appropriate for our sample with nonstationary variables.5

4. Empirical Findings

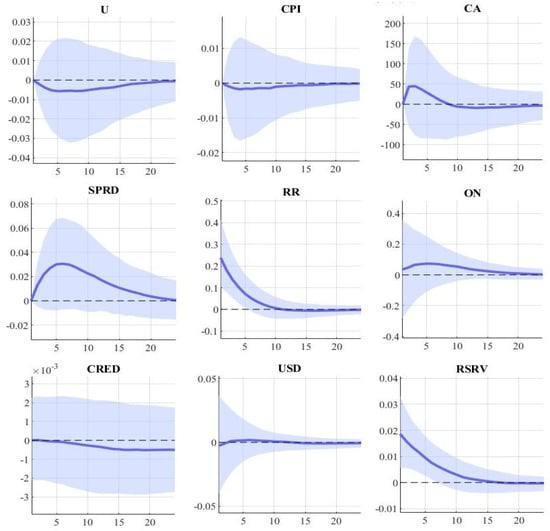

We display the impulse response functions iterated by using the identification scheme given in Table 1. Each response function displays the response of the given variable to a one standard deviation in the relevant shock. The solid blue line shows the median responses and the shadowed area around the line is 16% and 84% quantiles. Therefore, the shadowed area corresponds to a 68 percent credibility interval of the response.6

Impulse response functions to a reserve requirement shock are presented in Figure 1. The responses are largely in line with the literature and with the expectations from new policy tools implemented by the CBRT. With respect to the credit market, the spread rises for about seven months and the response stays positive for more than a year after a reserve requirement shock, which is a reasonable response considering the implicit tax effect7. Domestic credit is slow to respond initially but eventually declines sluggishly after about eight months and remains so for two years. Alper et al. (2014) also noted that domestic credit remained stable in the initial months of the monetary tightening cycle. The response of domestic credit is slow and limited but persistent.

Figure 1.

Responses to the reserve requirement shock.

The exchange rate shows a fractional decline as an immediate response and wanders around the zero axis over the scope. We observe a distinct improvement in the current account which lasts for nearly one year.

The price level shows an insignificant downward response while the unemployment rate decreases slightly over a period of more than one year. The decline in the unemployment rate, although theoretically unexpected, reflects the dynamics of the Turkish economy in the period under study.

The increase in the reserves shows that the reduction in the bank reserves following an increase in the reserve requirement is compensated by the central bank but the increase in the policy rate further reveals that it performed only partially.

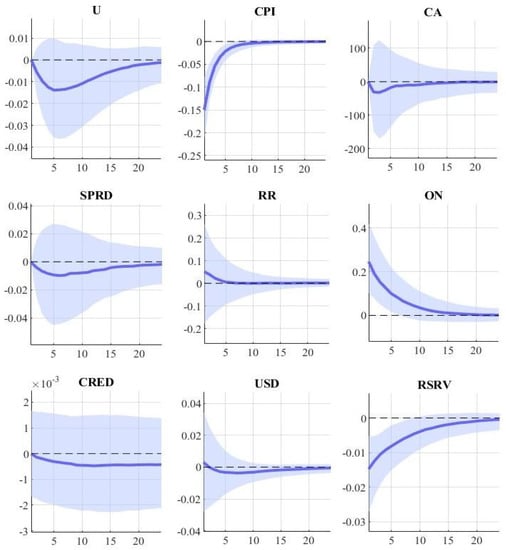

Impulse response functions to an interest rate shock are presented in Figure 2. The responses are again consistent with the literature. We will compare our results with those of Glocker and Towbin (2015) for Brazil, since this is the most comparable analysis to ours given the methodology and the range of variables studied. In response to an increase in the overnight interest rate, which is the interest rate around which the corridor is constructed, the price level falls significantly, which shows that the identification scheme overcomes the price puzzle. A trough is reached after three months and this level is maintained for almost a year. In Glocker and Towbin’s (2015) analysis of Brazil, the price response to an interest rate shock is similar but lasts much longer: a trough is reached after a year and it takes another 18 months to die out.

Figure 2.

Responses to the interest rate shock.

Regarding the external variables, the nominal exchange rate appreciates only infinitesimally and then navigates around the zero axis. The response in Brazil is an initial appreciation of 5% and the currency does not depreciate back to its initial level for almost a year. The interest rate shock in Turkey does not help increase the value of the currency but only helps maintain it. The current account turns back to its balance after a slight deterioration for about one year, which is again an expected reaction. In comparison to Brazil, we again note that the response is faster and shorter lived. Surprisingly, the unemployment rate does not increase after a tightening of the monetary policy. This response of the unemployment rate is in line with our expectations since Turkish economy displayed a strong recovery after a short depression in 20098 due to strong domestic and external demand.

The credit market shows an expected response so that the credit shrinks after the contractionary effect of the increase in the policy rate. The spread declines as the overnight rate increases which can be explained by the findings of Binici et al. (2019). They show that the overnight rate has an asymmetric effect on loan rates, affecting corporate loan rates more strongly than consumer loan rates.

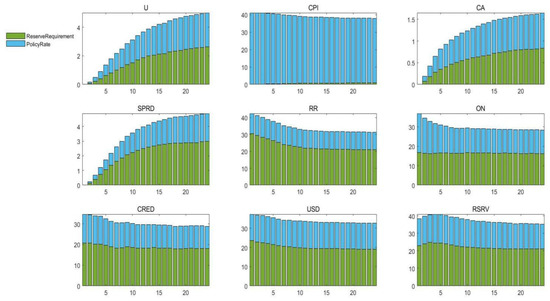

Figure 3 shows the forecast error variance decomposition for the reserve requirement and the interest rate shocks, depicting what proportion of the variance in the variables is explained by each shock. In other words, the forecast error variance decomposition represents the importance of the intended shock on the variables and reveals the transmission mechanism of these policy tools.

Figure 3.

Forecast error variance decomposition.

After 24 months, both the reserve requirement and the interest rate shocks no longer have a significant effect on the variations in unemployment and the current account, about 2% and 1% respectively. Most of the variation in the consumer price index is explained by interest rate shock, which is to be expected from a contractionary monetary policy. The effect of the reserve requirement shock on the spread is surprisingly lower than what the theory predicts, about 3% over the two year horizon. This result may be attributed to indirect effects of other macroeconomic variables on the spread other than the reserve requirement shock. The main incentive in employing the two monetary policy tools was to contain credit growth and the volatility in the exchange rate. The results reveal that expectations are realised. The variations in domestic credits and the exchange rate are explained by the reserve requirement and the interest rate shocks to a large degree.

To further investigate the robustness of our findings, we use the weighted average funding cost as the interest rate (WAFC), the headline consumer price index (CPI) and the producers price index (PPI) instead of CPI-D. The responses to both shocks are robust to the use of these alternative measures. These results are not presented here but they are provided as Supplementary Materials.

5. Discussion

Our results are directly comparable to those of Glocker and Towbin (2015) for Brazil since both the methodologies and the range of variables studied are similar. Turkey and Brazil also share similarities regarding external risks. In Brazil, the response of the spread to a reserve requirement shock is almost identical. The response of domestic credit is immediate in contrast, but otherwise very similar, that is small in magnitude but persistent. So, in both Turkey and in Brazil, tightening lending conditions are observed after a positive reserve requirement shock. In Brazil, an improvement in the current account is observed accompanying a depreciation of the currency. In Turkey, the reserve policy which enables banks to keep reserves in foreign currency makes it possible to improve the current account without a change in the value of the currency.

A reserve requirement as a macroprudential tool is successful in stabilising the economy and reducing unemployment. Glocker and Towbin (2015) found that unemployment in the Brazilian economy responds differently to a reserve requirement shock. Monetary tightening increases unemployment in Brazil.

The response of the Turkish credit market is qualitatively identical to the response of the Brazilian credit market but there are important differences as well. The fall in the spread is corrected after 10 months in Brazil but it takes twice as long in Turkey. The responses of the Turkish economy generally mean a faster return to pre-shock levels irrespective of the type of shock, but the response of the spread seems to be an exception which may be explained by the asymmetric effect of the overnight rate on loan rates.

6. Conclusions

In this paper we utilised a Bayesian Structural Vector Autoregression (SVAR) model with sign and zero restrictions in order to analyse the capability of the new policy tools, namely the reserve option mechanism (ROM) and the interest rate corridor, of the Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey in restraining the harmful effects of the post-crisis period on the Turkish economy. The intended purpose of employing these tools was to control the exchange rate, the current account and limit credit growth to maintain the financial stability. The results reveal that the new policy frame is efficient in curbing the volatility in the exchange rates and in improving the current account balance. While the reserve requirements seem to be more effective on the current account and partly on the exchange rate, the interest rate is explicitly better in controlling the price level and credits. In this regard, the reserve option mechanism cannot be assumed as an alternative to the interest rate but rather functions as a supplementary instrument for achieving financial stability. Moreover, the results show that the new policy framework is efficient in curbing the adverse effects of volatile capital flows, at least during the period in which it is intensely implemented.

As discussed in the literature9, financial stability is a much broader concept than price stability, which necessitates the involvement of other regulatory authorities in policy making or restructuring the central banks to support financial stability. Therefore, at least in the Turkish case, we conclude that a comprehensive policy approach is needed to curb credit growth in order to maintain financial stability in periods of high capital inflow, which remains to be analysed in future work.

The policies implemented by the Turkish Central Bank in the aftermath of the global financial crisis represent a bold and novel policy framework that has had at least some of the intended consequences in periods when it was intensely used. The active use of this policy ended in May 2018. The Turkish economy exhibited negative growth in the last quarter of 2018 and the subsequent two quarters. The next year the COVID-19 pandemic wreaked havoc through the global economy as well as the Turkish economy. As the pandemic is considered to be over in many countries as well as in Turkey, the Turkish economy is experiencing much higher inflation than the rest of the world. The Turkish lira is very volatile and has depreciated by 60 percent between September 2021 and February 2022.10 Monetary policy could have an important role to play in stabilising the Turkish economy during these turbulent times.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/economies10040076/s1, Figure S1: Robustness Check (PPI-RR); Figure S2: Robustness Check (PPI-ON); Figure S3: Robustness Check (CPI-RR); Figure S4: Robustness Check (CPI-ON); Figure S5: Robustness Check (WAFC-RR); Figure S6: Robustness Check (WAFC-ON); Table S1: Unit Root Tests of Variables; Estimation Results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Ç. and A.O.B.; methodology, M.Ç. and A.O.B.; software, M.Ç.; validation, A.O.B.; formal analysis, M.Ç. and A.O.B..; investigation, M.Ç.; resources, M.Ç.; data curation, M.Ç. and A.O.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Ç.; writing—review and editing, A.O.B.; visualization, M.Ç.; supervision, A.O.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data used in this research can be accessed at: Oğuş Binatlı, Ayla; Çelik, Mahmut (2022), “Data to evaluate macroprudential instruments in Turkey”, Mendeley Data, V2, doi: 10.17632/wbxz9m74k6.2.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank three anonymous referees for insightful and constructive comments. All remaining errors and omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Details on Data

Table A1.

Data definitions and sources.

Table A1.

Data definitions and sources.

| Variable | Definition | Transformation | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| U | Unemployment, all persons (ages 15 and over). | Seasonally adjusted | TurkStat |

| CPI_D | CPI_D, excluding unprocessed food, alcoholic beverages and tobacco. | Seasonally adjusted | TurkStat |

| CA | Current account, balance of payments, million USD. | Seasonally adjusted, | CBRT |

| SPRD | The difference between the commercial loan rate (with less than three-months maturity) and the deposit rate (with maturities up to three months), averaged, monthly. | CBRT | |

| RR | Required Reserve Rates | We take the weighted average of the reserve requirements across maturities of liabilities subject to the reserve requirement and compute the cost-effective reserve requirement ratio during the implementation period of ROM. For a detailed explanation see (Alper et al. 2014). | CBRT |

| ON | BIST overnight rate, monthly-averaged. | After May 2010, the CBRT utilized both the overnight lending and the one-week repo auctions at varying amounts according to its policy stance and the BIST overnight rate fluctuated within the interest rate corridor (Küçük et al. 2016). So, in order to reflect the policy stance of the CBRT, we take the BIST overnight rate as the interest rate. | BIST |

| CRED | Claims on private sector. | Logged | CBRT |

| USD | USD/TRY exchange rate. | CBRT | |

| RSRV | Banking reserves. | Logged | CBRT |

| FED | The federal funds rate for US monetary policy | FED | |

| CP | Commodity price index | IMF | |

| VIX | The CBOE’s index of 1-month implied volatility of S&P 500 Index. | CBOE | |

| IP | Industrial Production for EU | CBP Netherlands |

Figure A1.

Endogenous variables used in the baseline model.

Table A2.

BVAR estimation results on selected macroeconomic variables.

Table A2.

BVAR estimation results on selected macroeconomic variables.

| U | CPI | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient * | St.dev | Low. Bound | Upp. Bound | Coefficient * | St.dev | Low. Bound | Upp. Bound | |

| Ut−1 | 0.825 | 0.049 | 0.776 | 0.874 | 0.007 | 0.044 | −0.036 | 0.051 |

| CPIt−1 | −0.014 | 0.039 | −0.053 | 0.024 | 0.577 | 0.073 | 0.504 | 0.649 |

| CAt−1 | −0.000 | 0.000 | −0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.000 | 0.000 |

| SPRDt−1 | 0.009 | 0.022 | −0.013 | 0.031 | −0.001 | 0.026 | −0.027 | 0.024 |

| RRt−1 | −0.01 | 0.016 | −0.026 | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.018 | −0.017 | 0.019 |

| ONt−1 | −0.021 | 0.013 | −0.034 | −0.008 | −0.006 | 0.015 | −0.021 | 0.009 |

| CREDt−1 | 0.164 | 0.426 | −0.26 | 0.588 | −0.018 | 0.49 | −0.505 | 0.469 |

| USDt−1 | −0.116 | 0.132 | −0.247 | 0.015 | −0.008 | 0.155 | −0.162 | 0.146 |

| RSRVt−1 | 0.118 | 0.184 | −0.065 | 0.301 | 0.028 | 0.213 | −0.184 | 0.24 |

| Intercept | 0.711 | 2.493 | −1.768 | 3.191 | −0.265 | 2.896 | −3.145 | 2.615 |

| VIXt−1 | −0.001 | 0.007 | −0.008 | 0.005 | 0.004 | 0.008 | −0.004 | 0.011 |

| IPt−1 | −0.006 | 0.032 | −0.038 | 0.026 | 0.007 | 0.037 | −0.03 | 0.044 |

| FEDt−1 | −0.356 | 0.253 | −0.608 | −0.104 | 0.217 | 0.284 | −0.065 | 0.499 |

| CPt−1 | 0.004 | 0.009 | −0.005 | 0.012 | 0.023 | 0.01 | 0.013 | 0.033 |

| Trend | −0.024 | 0.032 | −0.056 | 0.008 | 0.009 | 0.036 | −0.027 | 0.045 |

| Trend2 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.000 | 0.000 | −0.000 | 0.000 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.863 | 0.287 |

* Coefficients are posterior estimates.

Table A3.

BVAR estimation results on selected financial variables.

Table A3.

BVAR estimation results on selected financial variables.

| SPRD | USD | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient * | St.dev | Low. Bound | Upp. Bound | Coefficient * | St.dev | Low. Bound | Upp. Bound | |

| Ut−1 | −0.114 | 0.069 | −0.183 | −0.045 | 0.005 | 0.012 | −0.007 | 0.016 |

| CPIt−1 | −0.010 | 0.071 | −0.081 | 0.061 | 0.007 | 0.012 | −0.005 | 0.020 |

| CAt−1 | −0.000 | 0.000 | −0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.000 | 0.000 |

| SPRDt−1 | 0.773 | 0.057 | 0.716 | 0.829 | −0.004 | 0.007 | −0.011 | 0.003 |

| RRt−1 | 0.018 | 0.029 | −0.010 | 0.047 | 0.002 | 0.005 | −0.003 | 0.007 |

| ONt−1 | 0.016 | 0.024 | −0.008 | 0.004 | −0.003 | 0.004 | −0.007 | 0.001 |

| CREDt−1 | −0.473 | 0.778 | −1.246 | 0.300 | −0.006 | 0.133 | −0.138 | 0.126 |

| USDt−1 | 0.323 | 0.242 | 0.082 | 0.564 | 0.816 | 0.060 | 0.757 | 0.875 |

| RSRVt−1 | 0.395 | 0.337 | 0.060 | 0.730 | 0.049 | 0.058 | −0.009 | 0.107 |

| Intercept | −0.892 | 4.560 | −5.427 | 3.642 | −0.09 | 0.784 | −0.870 | 0.689 |

| VIXt−1 | −0.007 | 0.012 | −0.019 | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.002 | −0.001 | 0.003 |

| IPt−1 | −0.058 | 0.059 | −0.116 | 0.000 | 0.011 | 0.010 | 0.001 | 0.021 |

| FEDt−1 | 0.143 | 0.455 | −0.310 | 0.596 | 0.031 | 0.076 | −0.045 | 0.107 |

| CPt−1 | 0.021 | 0.016 | 0.006 | 0.037 | −0.001 | 0.003 | −0.004 | 0.001 |

| Trend | 0.072 | 0.059 | 0.013 | 0.130 | −0.002 | 0.010 | −0.012 | 0.008 |

| Trend2 | −0.000 | 0.000 | −0.001 | −0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.000 | 0.000 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.834 | 0.99 |

* Coefficients are posterior estimates.

Notes

| 1. | See Monetary and Exchange Rate Policy of the CBRT (CBRT 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022). |

| 2. | See Appendix A, Table A1 for detailed information about definition and source of data. Figure A1 displays the time series plots of all the endogenous variables. |

| 3. | A battery of tests (both parametric and nonparametric) to detect seasonality, namely the test on autocorrelation on seasonal lags, the Friedman test, the Kruskal-Wallis test, the identification of seasonal peaks with the auto-regressive spectrum and Tukey periodogram and the test on regression with seasonal dummies were performed in JDemetra+ 2.2.3. |

| 4. | A surprise policy rate hike is followed by a consecutive increase in the inflation rate. |

| 5. | Using Normal-Wishart prior or Independent Normal-Wishart did not change the results significantly. The results are available upon request. |

| 6. | The upper and lower bounds here do not correspond to error bands. Credibility intervals render information about the distribution of impulse responses to a particular shock. |

| 7. | The increase in reserve requirements behaves like an implicit tax on the banking sector and widens the spread between deposit and the lending rates (Glocker and Towbin 2015). |

| 8. | Strong domestic and external demand helped the Turkish economy recover quickly. See Kara (2012) for the condition of the Turkish economy after 2008. |

| 9. | For alternative mechanisms see Özatay (2012), Ersel (2012), Basci and Kara (2011) and see BIS (2011), BoE (2011) for alternative objectives for the central banks. Bruno et al. (2017) show that macroprudential policies are more effective when they complement monetary policy tightening. |

| 10. | The average monthly TL/USD exchange rate retrieved on 18 March 2022 from the online database of the Central of Bank of the Republic of Turkey (https://evds2.tcmb.gov.tr/) (accessed on 18 March 2022) was 8.51 in September 2021 and 13.62 in February 2022. |

References

- Alper, Koray, Ali Hakan Kara, and Mehmet Yörükoğlu. 2012. Reserve Option Mechanism [Rezerv Opsiyonu Mekanizmasi]. Ekonomi Notları 2012–28. Ankara: Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey. [Google Scholar]

- Alper, Koray, Mahir Binici, Selva Demiralp, Hakan Kara, and Pinar Ozlu. 2014. Reserve Requirements, Liquidity Risk, and Credit Growth. In Koç University-TUSIAD Economic Research Forum Working Papers (No. 1416). Istanbul: Koc University-TUSIAD Economic Research Forum. Available online: https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:koc:wpaper:1416 (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Antolín-Díaz, Juan, and Juan F. Rubio-Ramírez. 2018. Narrative Sign Retrictions for SVARs. American Economic Review 108: 2802–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, Jonas. E., Juan F. Rubio-Ramirez, and Daniel F. Waggoner. 2014. Inference Based on SVARs Identified with Sign and Zero Restrictions: Theory and Applications; No. 1100, 1-72. Atlanta: Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta (US), Washington, DC: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US).

- Armas, Adrian, Paul Castillo, and Marco Vega. 2014. Inflation targeting and quantitative tightening: Effects of reserve requirements in Peru. Economia 15: 133–75. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24368352 (accessed on 17 March 2022).

- Aslaner, Oğuz, Uğur Çıplak, Hakan Kara, and Doruk Küçüksaraç. 2015. Reserve options mechanism: Does it work as an automatic stabilizer? Central Bank Review 15: 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Aysan, Ahmet Faruk, Salih Fendoglu, and Mustafa Kılınç. 2014. Managing short-term capital flows in new central banking: Unconventional monetary policy framework in Turkey. Eurasian Economic Review 4: 45–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bank for International Settlements (BIS). 2011. Central Bank Governance and Financial Stability. Report by Central Bank Governance Group. Basel: BIS. [Google Scholar]

- Bank of England (BoE). 2011. Instruments of Macroprudential Policy. Bank of England Discussion Paper. London: BoE. [Google Scholar]

- Bartkiewicz, Piotr. 2018. The Impact of Quantitative Easing on Emerging Markets: Literature Review. e-Finanse 14: 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basci, Erdem, and Hakan Kara. 2011. Financial Stability and Monetary Policy. Working Papers 1108, Research and Monetary Policy Department, Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey. Report. Ankara: Central Bank of Republic of Turkey. [Google Scholar]

- Belke, Ansgar, and Christian Fahrholz. 2018. Emerging and small open economies, unconventional monetary policy and exchange rates—A survey. International Economics and Economic Policy 15: 331–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, Saroj, Arpita Chatterjee, and Woong Yong Park. 2021. Effects of US quantitative easing on emerging market economies. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 122: 104031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binatli, Ayla Oğuş, and Niloufer Sohrabji. 2019. Monetary Policy Transmission in the Euro Zone. Athens Journal of Business & Economics 5: 79–92. [Google Scholar]

- Binici, Mahir, Hakan Kara, and Pınar Özlü. 2019. Monetary transmission with multiple policy rates: Evidence from Turkey. Applied Economics 51: 1869–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, Valentina, and Hyung Song Shin. 2013. Capital Flows, Cross-Border Banking and Global Liquidity (No. w19038); Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. [CrossRef]

- Bruno, Valentina, and Hyung Song Shin. 2014. Assessing macroprudential policies: Case of South Korea. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics 116: 128–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, Valentina, Ilhyock Shim, and Hyung Song Shin. 2017. Comparative assessment of macroprudential policies. Journal of Financial Stability 28: 183–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, Guillermo A. 1998. Capital flows and capital-market crises: The simple economics of sudden stops. Journal of Applied Economics 1: 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carriero, Andrea, Todd E. Clark, and Massimiliano Marcellino. 2015. Bayesian VARs: Specification choices and forecast accuracy. Journal of Applied Econometrics 30: 46–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CBRT. 2015. Road Map During The Normalization of Global Monetary Policies. Available online: https://www.tcmb.gov.tr/wps/wcm/connect/EN/TCMB+EN/Main+Menu/Announcements/Press+Releases/2015/CBRTRoadMap2015 (accessed on 15 June 2020).

- CBRT. 2018. Press Release on the Operational Framework of the Monetary Policy. Available online: https://www.tcmb.gov.tr/wps/wcm/connect/EN/TCMB+EN/Main+Menu/Announcements/Press+Releases/2018/ANO2018-21 (accessed on 15 June 2020).

- CBRT. 2019. Monetary and Exchange Rate Policy for 2019. Available online: https://www.tcmb.gov.tr/wps/wcm/connect/EN/TCMB+EN/Main+Menu/Publications/Monetary+and+Exchange+Rate+Policy+Texts (accessed on 7 December 2021).

- CBRT. 2020. Monetary and Exchange Rate Policy for 2020. Available online: https://www.tcmb.gov.tr/wps/wcm/connect/EN/TCMB+EN/Main+Menu/Publications/Monetary+and+Exchange+Rate+Policy+Texts (accessed on 7 December 2021).

- CBRT. 2021. Monetary and Exchange Rate Policy for 2021. Available online: https://www.tcmb.gov.tr/wps/wcm/connect/EN/TCMB+EN/Main+Menu/Publications/Monetary+and+Exchange+Rate+Policy+Texts (accessed on 7 December 2021).

- CBRT. 2022. Monetary and Exchange Rate Policy for 2022. Available online: https://www.tcmb.gov.tr/wps/wcm/connect/EN/TCMB+EN/Main+Menu/Publications/Monetary+and+Exchange+Rate+Policy+Texts (accessed on 7 December 2021).

- Christiano, Lawrence J., and Martin Eichenbaum. 1992. Liquidity effects and the monetary transmission mechanism. The American Economic Review 82: 346–53. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2117426 (accessed on 17 March 2022).

- Christiano, Lawrence J., Martin Eichenbaum, and Charles L. Evans. 1999. Monetary policy shocks: What have we learned and to what end? Handbook of Macroeconomics 1: 65–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curdia, Vasco, and Michael Woodford. 2011. The central-bank balance sheet as an instrument of monetary policy. Journal of Monetary Economics 58: 54–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Değerli, Ahmet, and Salih Fendoğlu. 2015. Reserve option mechanism as a stabilizing policy tool: Evidence from exchange rate expectations. International Review of Economics and Finance 35: 166–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieppe, Alistair, Björn van Roye, and Romain Legrand. 2016. The BEAR Toolbox. No. 1934. Frankfurt am Main: European Central Bank. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enders, Walter. 2010. Applied Econometric Time Series, 3rd ed. New York: Wiley, p. 303. [Google Scholar]

- Ersel, Hasan. 2012. Finansal istikrarın sağlanması için nasıl bir mekanizma tasarlanabilir? Iktisat Isletme ve Finans 27: 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanchon, Phillip, and Jeanne Wendel. 1992. Estimating VAR models under non-stationarity and cointegration: Alternative approaches for forecasting cattle prices. Applied Economics 24: 207–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatas, Antonio, and Ilian Mihov. 2001. The Effects of Fiscal Policy on Consumption and Employment: Theory and Evidence. CEPR Discussion Paper, No. 2760. London: Centre for Economic Policy Research. [Google Scholar]

- Federico, Pablo, Carlos A. Vegh, and Guillermo Vuletin. 2012. Effects and Role of Macroprudential Policy: Evidence from reserve requirements based on a narrative approach. Paper presented at the Understanding Macroprudential Regulation Workshop Organized by Norges Bank, Oslo, Norway, November 29, Volume 29, p. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Glocker, Christian, and Pascal Towbin. 2012. Reserve Requirements for Price and Financial Stability: When Are They Effective? International Journal of Central Banking 8: 65–114. Available online: https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:ijc:ijcjou:y:2012:q:1:a:4 (accessed on 17 March 2022). [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Glocker, Christian, and Pascal Towbin. 2015. Reserve requirements as a macroprudential instrument–Empirical evidence from Brazil. Journal of Macroeconomics 44: 158–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosse, R. 2004. The challenges of globalization for emerging market firms. Latin American Business Review 4: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, Hernando Vargas, Yanneth R. Betancourt, Carlos Varela, and Norberto Rodríguez. 2011. Effects of reserve requirements in an inflation targeting regime: The case of Colombia. In The Global Crisis And Financial Intermediation In Emerging Market Economies. Edited by Bank for International Settlements. BIS Papers Chapters. Basel: Bank for International Settlements, vol. 54, pp. 133–169. [Google Scholar]

- IMF. 2013a. Unconventional Monetary Policies—Recent Experience and Prospects. IMF Staff Report. Available online: http://www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2013/041813a.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- IMF. 2013b. Unconventional Monetary Policies—Recent Experience and Prospects—Background Paper. IMF Staff Report. Available online: http://www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2013/041813.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- IMF. 2013c. Global Impact and Challenges of Unconventional Monetary Policies. IMF Policy Paper. Available online: http://www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2013/090313.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Kahou, Mahdi Ebrahimi, and Alfred Lehar. 2017. Macroprudential policy: A review. Journal of Financial Stability 29: 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, Hakan. 2012. Monetary Policy in Turkey after the Global Crisis. Working Paper 12/17. Research and Monetary Policy Department Report. Ankara: Central Bank of Republic of Turkey. [Google Scholar]

- Kara, Hakan. 2015. Interest Rate Corridor and the Monetary Policy Stance [Faiz Koridoru ve Para Politikasi Durusu]. (No. 1513). Ankara: Research and Monetary Policy Department, Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kashyap, Anil K., and Jeremy C. Stein. 2012. The optimal conduct of monetary policy with interest on reserves. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 4: 266–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küçük, Hande, Pınar Özlü, Anıl Talaslı, Deren Ünalmış, and Canan Yüksel. 2016. Interest Rate Corridor, liquidity management, and the overnight spread. Contemporary Economic Policy 34: 746–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, Philip Richard. 2013. Financial globalisation and the crisis. Open Economies Review 24: 555–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Cheng Hoon, Alejo Costa, Francesco Columba, Piyabha Kongsamut, Akira Otani, Mustafa Saiyid, Torsten Wezel, and Xiaoyong Wu. 2011. Macroprudential Policy: What Instruments and How to Use Them? Lessons from Country Experiences. IMF Working Papers, 238. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, Domenico, and Pierre L. Siklos. 2016. Benchmarking macroprudential policies: An initial assessment. Journal of Financial Stability 27: 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubis, Alexander, Constantinos Alexiou, and Joseph G. Nellis. 2021. Monetary and macroprudential policies in the presence of external shocks: Evidence from an emerging economy. Journal of Economic Studies. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, Christopher, and Costas Milas. 2012. Quantitative easing: A sceptical survey. Oxford Review of Economic Policy 28: 750–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, Philippe, and Helene Rey. 2006. Globalization and emerging markets: With or without crash? American Economic Review 96: 1631–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, Enrique G. 2006. Lessons from the debt-deflation theory of sudden stops. American Economic Review 96: 411–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, Enrique G., and Marco E. Terrones. 2008. An Anatomy of Credit Booms: Evidence from Macro Aggregates and Micro Data; (No. w14049). Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. [CrossRef]

- Mester, Loretta J. 2017. The nexus of macroprudential supervision, monetary policy, and financial stability. Journal of Financial Stability 30: 177–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishkin, Frederic S. 1999. Lessons from the Asian crisis. Journal of International Money and Finance 18: 709–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishkin, Frederic S. 2001. Financial Policies and the Prevention of Financial Crises in Emerging Market Economics. (No. 2683). Washington, DC: World Bank Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Mountford, Andrew, and Harald Uhlig. 2009. What are the effects of fiscal policy shocks? Journal of Applied Econometrics 24: 960–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obstfeld, Maurice. 2004. Globalization, Macroeconomic Performance, and the Exchange Rates of Emerging Economies. (No. w10849). Cambridge: Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oduncu, Arif, Yasin Akçelik, and Ergun Ermisoglu. 2013. Reserve Options Mechanism and FX Volatility. Working Paper No: 13/03. Ankar: Research and Monetary Policy Department, Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Özatay, Fatih. 2012. Para politikasında yeni arayışlar. Iktisat Isletme ve Finans 27: 51–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadamou, Stephanos T., Costas Siriopoulos, and Nikolaos A. Kyriazis. 2020. A survey of empirical findings on unconventional central bank policies. Journal of Economic Studies 47: 1533–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, Diego, Vegh A. Carlos, and Vuletin Guillermo. 2020. The Macroeconomic Effects of Macroprudential Policy: Evidence From A Narrative Approach. NBER Working Papers, 27687. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Sahin, Afşin, Burak Dogan, and M. Hakan Berument. 2015. Effectiveness of the reserve option mechanism as a macroeconomic prudential tool: Evidence from Turkey. Applied Economics 47: 6075–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, Christopher A. 1980. Macroeconomics and reality. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society 48: 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, Christopher A. 1992. Interpreting the macroeconomic time series facts: The effects of monetary policy. European Economic Review 36: 975–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, Christopher A., James H. Stock, and Mark W. Watson. 1990. Inference in Linear Time Series Models with Some Unit Roots. Econometrica 58: 113–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, Daniel L. 2017. Effectiveness of QE: An assessment of event-study evidence. Journal of Macroeconomics 52: 56–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovar, Camilo Ernesto, Mercedes Garcia-Escribano, and Mercedes Vera Martin. 2012. Credit Growth and the Effectiveness of Reserve Requirements and Other Macroprudential Instruments in Latin America. IMF Working Papers, 142. Washington, DC: IMF. [Google Scholar]

- Uhlig, Harald. 2005. What are the Effects of Monetary Policy on Output? Results from an Agnostic Identification Procedure. Journal of Monetary Economics 52: 381–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varlık, Serdar, and M. Hakan Berument. 2016. Credit channel and capital flows: A macroprudential policy tool? Evidence from Turkey. Journal of Macroeconomics 16: 145–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Varlık, Serdar, and M. Hakan Berument. 2017. Multiple policy interest rates and economic performance in a multiple monetary-policy-tool environment. International Review of Economics & Finance 52: 107–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).