The Ownership Structure, and the Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Disclosure, Firm Value and Firm Performance: The Audit Committee as Moderating Variable

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Foreign Ownership and Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Disclosure

2.2. Public Ownership and Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Disclosure

2.3. State Ownership and Environmental, Social, and Governance Disclosure

2.4. Family Ownership and Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Disclosure

2.5. Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Disclosure and Firm Value

2.6. Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Disclosure and Firm Performance

2.7. Audit Committee Moderation of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Disclosure, Firm Value, and Firm Performance

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample Selection and Data Source

3.2. The Measurement of Variables

3.3. Method of Analysis

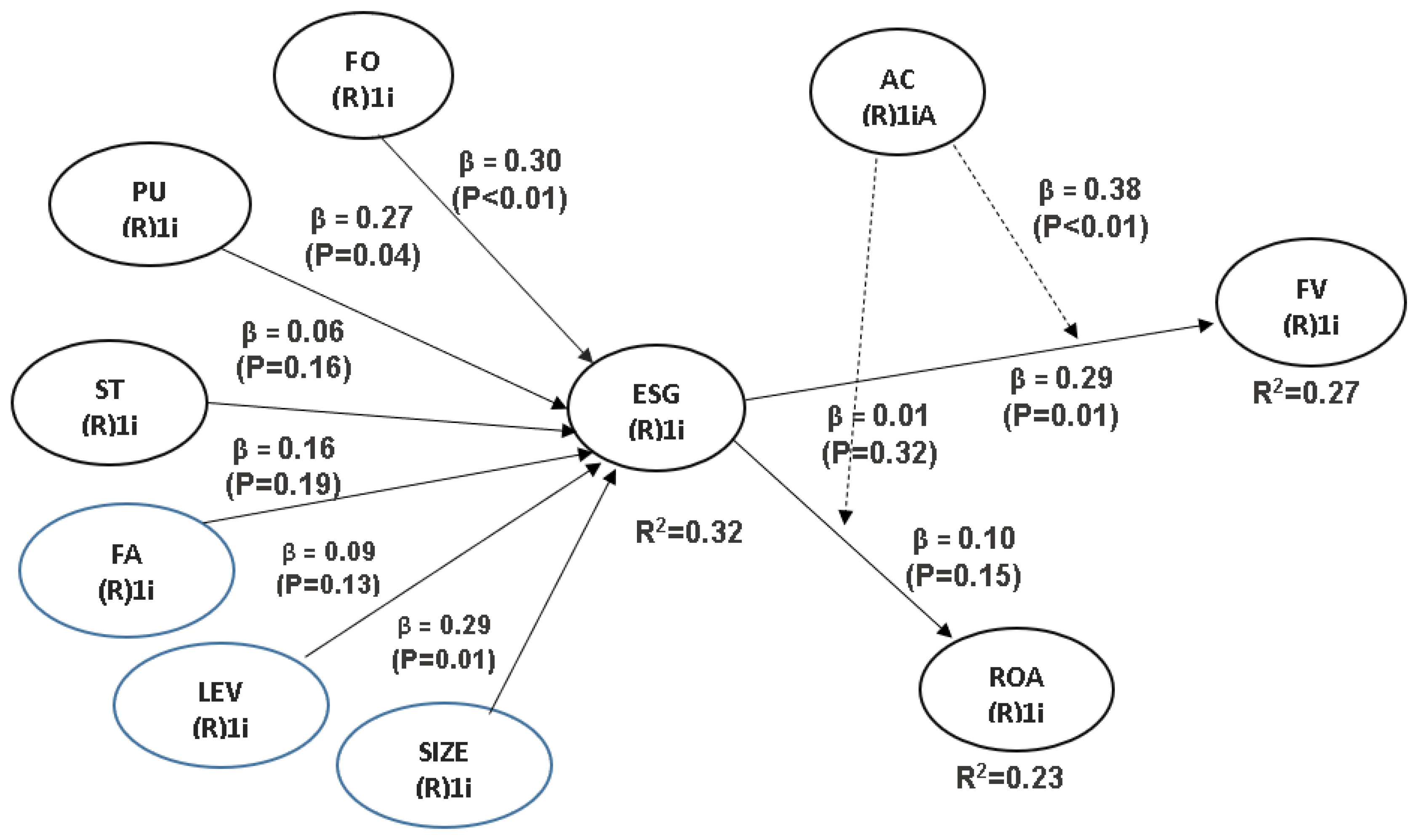

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Results

4.2. Discussion

5. Conclusions

5.1. Practical Implication

5.2. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aboud, Ahmed, and Ahmed Diab. 2018. The Impact of Social, Environmental and Corporate Governance Disclosures on Firm Value: Evidence from Egypt. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies 8: 442–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Qa’dan, Mohammad Bassam, and Mishiel Said Suwaidan. 2019. Board composition, ownership structure and corporate social responsibility disclosure: The case of Jordan. Social Responsibility Journal 15: 28–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Raja Adzrin Raja, Amirul Azri Ayob, Saunah Zainon, and Agung Nur Probohudono. 2021. The Influence of Environmental, Social and Governance Reporting on Firm Value: Malaysian Evidence. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences 11: 1058–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alareeni, Bahaaeddin Ahmed, and Allam Hamdan. 2020. ESG Impact on Performance of US S&P 500-Listed Firms. Corporate Governance 20: 1409–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Amosh, Hamzeh, and Saleh F. A. Khatib. 2021. Ownership Structure and Environmental, Social and Governance Performance Disclosure: The Moderating Role of the Board Independence. Journal of Business and Socio-Economic Development, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albawwat, Ala Hussein, and Mohamad Yazis Ali basah. 2015. Corporate Governance and Voluntary Disclosure of Interim Financial Reporting in Jordan. Journal of Public Administration and Governance 5: 100–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Al-Janadi, Yaseen, Rashidah Abdul Rahman, and Abdulsamad Alazzani. 2016. Does Government Ownership Affect Corporate Governance and Corporate Disclosure?: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Managerial Auditing Journal 31: 871–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aman, Hiroyuki, and Pascal Nguyen. 2013. Does Good Governance Matter to Debtholders? Evidence from the Credit Ratings of Japanese Firms. Research in International Business and Finance 29: 14–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amidjaya, Prihatnolo Gandhi, and Ari Kuncara Widagdo. 2020. Sustainability Reporting in Indonesian Listed Banks: Do Corporate Governance, Ownership Structure and Digital Banking Matter? Journal of Applied Accounting Research 21: 231–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aouadi, Amal, and Sylvain Marsat. 2018. Do ESG Controversies Matter for Firm Value? Evidence from International Data. Journal of Business Ethics 151: 1027–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appuhami, Ranjith, and Shamim Tashakor. 2017. The Impact of Audit Committee Characteristics on CSR Disclosure: An Analysis of Australian Firms. Australian Accounting Review 27: 400–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athari, Seyed Alireza, and Mahboubeh Bahreini. 2021. The Impact of External Governance and Regulatory Settings on the Profitability of Islamic Banks: Evidence from Arab Markets. International Journal of Finance and Economics 26: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athari, Seyed Alireza. 2021. Domestic Political Risk, Global Economic Policy Uncertainty, and Banks’ Profitability: Evidence from Ukrainian Banks. Post-Communist Economies 33: 458–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atif, Muhammad, Benjamin Liu, and Sivathaasan Nadarajah. 2022. The Effect of Corporate Environmental, Social and Governance Disclosure on Cash Holdings: Life-Cycle Perspective. Business Strategy and the Environment 31: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, Bello Usman, and Usman Aliyu Baba. 2021. The Effect of Ownership Structure on Social and Environmental Reporting in Nigeria: The Moderating Role of Intellectual Capital Disclosure. Journal of Global Responsibility 12: 210–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, Seong Mi, Md. Abdul Kaium Masud, and Jong Dae Kim. 2018. A Cross-Country Investigation of Corporate Governance and Corporate Sustainability Disclosure: A Signaling Theory Perspective. Sustainability 10: 2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamahros, Hasan Mohamad, Abdulsalam Alquhaif, Ameen Qasem, Wan Nordin Wan-hussin, Murad Thomran, Shaker Al-Duais, Siti Norwahida Shukeri, and Hytham M. A. Khojally. 2022. Corporate Governance Mechanisms and ESG Reporting: Evidence from the Saudi Stock Market. Sustainability 14: 6202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beloskar, Ved Dilip, and S. V. D. Nageswara Rao. 2022. Did ESG Save the Day? Evidence From India During the COVID-19 Crisis. In Asia-Pacific Financial Markets. Bombay: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biçer, Ali Altuğ, and Imad Mohamed Feneir. 2019. The Impact of Audit Committee Characteristics on Environmental and Social Disclosures. International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science 8: 111–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulhaga, Mounia, Abdelfettah Bouri, Ahmed A Elamer, and Bassam A Ibrahim. 2022. Environmental, Social and Governance Ratings and Firm Performance: The Moderating Role of Internal Control Quality. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 29: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouslah, Kais, Lawrence Kryzanowski, and Bouchra M Zali. 2013. The Impact of the Dimensions of Social Performance on Firm Risk. Journal of Banking and Finance 37: 1258–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brogi, Marina, and Valentina Lagasio. 2018. Environmental, Social, and Governance and Company Profitability: Are Financial Intermediaries Different? Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 26: 576–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buallay, Amina. 2019. Between Cost and Value: Investigating the Effects of Sustainability Reporting on a Firm’s Performance. Journal of Applied Accounting Research 20: 481–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporale, Guglielmo Maria, Luis Gil-Alana, Alex Plastun, and Inna Makarenko. 2022. Persistence in ESG and Conventional Stock Market Indices. Journal of Economics and Finance 46: 678–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlos, W. Chad, and Ben W. Lewis. 2018. Strategic Silence: Withholding Certification Status as a Hypocrisy Avoidance Tactic. Administrative Science Quarterly 63: 130–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Ling Foon, Bany Ariffin An, and Annual Bin Md Nasir. 2019. Does the Method of Corporate Diversification Matter to Firm’s Performance? Asia-Pacific Contemporary Finance and Development 26: 207–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, Yogesh, and Surya B. Kumar. 2018. Do Investors Value the Nonfinancial Disclosure in Emerging Markets? Emerging Markets Review 37: 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Zhongfei, and Guanxia Xie. 2022. ESG Disclosure and Financial Performance: Moderating Role of ESG Investors. International Review of Financial Analysis 83: 102291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daugaard, Dan, and Ashley Ding. 2022. Global Drivers for ESG Performance: The Body of Knowledge. Sustainability 14: 2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deegan, Craig. 2013. Financial Accounting Theory. Sydney: Mc Graw Hill Book Company. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Masi, Sara, Agnieszka Słomka-Gołębiowska, Claudio Becagli, and Andrea Paci. 2021. Toward Sustainable Corporate Behavior: The Effect of the Critical Mass of Female Directors on Environmental, Social, and Governance Disclosure. Business Strategy and the Environment 30: 1865–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicuonzo, Grazia, Francesca Donofrio, Simona Ranaldo, and Vittorio Dell Atti. 2022. The Effect of Innovation on Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Practices. Meditari Accountancy Research 30: 1191–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djaddang, Syahril, Darmansyah Darmansyah, Ronny Bagus Witjaksono, and Imam Ghozali. 2017. The Effects of Environmental Awareness and Corporate Social Responsibility on Earnings Quality: Testing the Moderating Role of Audit Committee. International Journal of Economic Perspectives 11: 100–11. [Google Scholar]

- Duque-Grisales, Eduardo, and Javier Aguilera-Caracuel. 2019. Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Scores and Financial Performance of Multilatinas: Moderating Effects of Geographic International Diversification and Financial Slack. Journal of Business Ethics 168: 315–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrell, Allen, Hao Liang, and Luc Renneboog. 2016. Socially Responsible Firms. Journal of Financial Economics 122: 585–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R. 1983. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Advances in Strategic Management, 31–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R. Edward. 1984. Stakeholder Theory of Modern Corporation. Boston: Pittman. [Google Scholar]

- Fuente, Gabriel de la, Margarita Ortiz, and Pilar Velasco. 2022. The Value of a Firm’s Engagement in ESG Practices: Are We Looking at the Right Side? Long Range Planning 55: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannopoulos, George, Renate Victoria Kihle Fagernes, Mahmoud Elmarzouky, and Kazi Abul Bashar Muhammad Afzal Hossain. 2022. The ESG Disclosure and the Financial Performance of Norwegian Listed Firms. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 15: 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GRI. 2013. G4 Sustainability Reporting Guidelines. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/standards/g4/Pages/default.aspx/ (accessed on 20 August 2022).

- Guo, Mingyuan, and Chendi Zheng. 2021. Foreign Ownership and Corporate Social Responsibility: Evidence from China. Sustainability 13: 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph F, G Tomas M Huli, Cristian Ringle, and Marko Sarstedt. 2016. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). New York: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph F., Jeffrey J. Risher, Marko Sarstedt, and Christian M. Ringle. 2019. When to Use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review 31: 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanifa, Mohamed Hisham, and Hafiz-Majdi Ab. Rashid. 2005. The Determinants of Voluntary Disclosures in Malaysia: The Case of Internet Financial. Unitar E-Journal 2: 22–42. [Google Scholar]

- Harjoto, Maretno A., and Hoje Jo. 2011. Corporate Governance and CSR Nexus. Journal of Business Ethics 100: 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, Arshad, Khaled Hussainey, and Doaa Aly. 2022. Determinants of Sustainability Reporting Decision: Evidence from Pakistan. Journal of Sustainable Finance and Investment 12: 214–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Feng, Hanyu Du, and Bo Yu. 2022. Corporate ESG Performance and Manager Misconduct: Evidence from China. International Review of Financial Analysis 82: 102201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, Michael C., and William H. Meckling. 1976. Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure. Journal of Financial Economics 3: 305–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Arifur, Mohammad Badrul Muttakin, and Javed Siddiqui. 2012. Corporate Governance and Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosures: Evidence from an Emerging Economy. Journal Business Ethics 110: 207–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khlif, Hichem, Kamran Ahmed, and Mohsen Souissi. 2016. Ownership Structure and Voluntary Disclosure: A Synthesis of Empirical Studies. Australian Journal of Management 42: 376–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Woo Sung, Kunsu Park, and Sang Hoon Lee. 2018. Corporate Social Responsibility, Ownership Structure, and Firm Value: Evidence from Korea. Sustainability 10: 2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Yongtae, Haidan Li, and Siqi Li. 2014. Corporate Social Responsibility and Stock Price Crash Risk. Journal of Banking & Finance 43: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, Klaus. 2018. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology. London: Sage Publications. Available online: http://www.uk.sagepub.com/textbooks/Book234903 (accessed on 22 August 2022).

- Kumar, Kishore, Ranjita Kumari, Monomita Nandy, Mohd Sarim, and Rakesh Kumar. 2022. Do Ownership Structures and Governance Attributes Matter for Corporate Sustainability Reporting? An Examination in the Indian Context. Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal 33: 1077–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Praveen, and Mohammad Firoz. 2022. Does Accounting-Based Financial Performance Value Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Disclosures? A Detailed Note on a Corporate Sustainability Perspective. Australasian Accounting Business and Finance Journal 16: 41–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Jiandong, and Jianmei Zhao. 2019. How Housing Affects Stock Investment—An SEM Analysis. Economies 7: 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Yiwei, Mengfeng Gong, Xiu Ye Zhang, and Lenny Koh. 2018. The Impact of Environmental, Social, and Governance Disclosure on Firm Value: The Role of CEO Power. British Accounting Review 50: 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindenberg, Eric B., and Stephen A. Ross. 1981. Tobin’s q Ratio and Industrial Organization. The Journal of Business 54: 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Heying, and Chan Lyu. 2022. Can ESG Ratings Stimulate Corporate Green Innovation? Evidence from China. Sustainability 14: 12516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maama, Haruna, and Kingsley Opoku Appiah. 2019. Green Accounting Practices: Lesson from an Emerging Economy. Qualitative Research in Financial Markets 11: 456–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manita, Riadh, Maria Giuseppina Bruna, Rey Dang, and L’Hocine Houanti. 2018. Board Gender Diversity and ESG Disclosure: Evidence from the USA. Journal of Applied Accounting Research 19: 206–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masud, Md. Abdul Kaium, Mohammad Nurunnabi, and Seong Mi Bae. 2018. The Effects of Corporate Governance on Environmental Sustainability Reporting: Empirical Evidence from South Asian Countries. Asian Journal of Sustainability and Social Responsibility 3: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, Wan Masliza Wan, and Shaista Wasiuzzaman. 2021. Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Disclosure, Competitive Advantage and Performance of Firms in Malaysia. Cleaner Environmental Systems 2: 100015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monk, Ashby. 2009. Recasting the Sovereign Wealth Fund Debate: Trust, Legitimacy, and Governance. New Political Economy 14: 451–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, Richard D. 1987. Signalling, Agency Theory and Accounting Policy Choice. Accounting and Business Research 18: 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naser, Kamal, Ahmad Al Hussaini, Duha Al Kwari, and Rana Nuseibeh. 2006. Determinants of Corporate Social Disclosure in Developing Countries: The Case of Qatar. Advances in International Accounting 19: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikulin, Egor D., Marat V. Smirnov, Andrei A. Sviridov, and Olesya V. Bandalyuk. 2022. Audit Committee Composition and Earnings Management in a Specific Institutional Environment: The Case of Russia. Corporate Governance 22: 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugraheni, Peni, Arum Indrasari, and Noradiva Hamzah. 2022. The Impact of Ownership Structure on CSR Disclosure: Evidence from Indonesia. Journal of Accounting and Investment 23: 229–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dwyer, Brendan. 2003. Conceptions of Corporate Social Responsibility: The Nature of Managerial Capture. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 16: 523–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlopoulos, Athanasios, Chris Magnis, and George Emmanuel Iatridis. 2019. Integrated Reporting: An Accounting Disclosure Tool for High Quality Financial Reporting. Research in International Business and Finance 49: 13–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulino, Silvia Carnini, Mirella Ciaburri, Barbara Sveva Magnanelli, and Luigi Nasta. 2022. Does ESG Disclosure Influence Firm Performance? Sustainability 14: 7595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabaya, Abdullah Jihad, and Norman Mohd Saleh. 2021. The Moderating Effect of IR Framework Adoption on the Relationship between Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Disclosure and a Firm’s Competitive Advantage. Environment, Development and Sustainability 24: 2037–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, William, and Tatiana Rodionova. 2014. The Influence of Family Ownership on Corporate Social Responsibility: An International Analysis of Publicly Listed Companies. Corporate Governance: An International Review 23: 184–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudyanto, Astrid. 2017. State Ownership, Family Ownership, and Sustainability Report Quality: The Moderating Role of Board Effectiveness. GATR Accounting and Finance Review 2: 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, Neha, and Monica Singhania. 2019. Performance Relevance of Environmental and Social Disclosures: The Role of Foreign Ownership. Benchmarking: An International Journal 26: 1845–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjad, Aymen, Gabriel Eweje, and David Tappin. 2019. Managerial Perspectives on Drivers for and Barriers to Sustainable Supply Chain Management Implementation: Evidence from New Zealand. Business Strategy and the Environment 29: 592–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, Mahdi, Hossein Tarighi, and Malihe Rezanezhad. 2017. The Relationship between Board of Directors’ Structure and Company Ownership with Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure: Iranian Angle. Humanomics 33: 398–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvato, Carlo, and Leif Melin. 2008. Creating Value across Generations in Family-Controlled Businesses: The Role of Family Social Capital. Family Business Review 21: 259–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, Imlak. 2022. Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Practice and Firm Performance: An International Evidence. Journal of Business Economics and Management 23: 218–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Preeti, Priyanka Panday, and R. C. Dangwal. 2020. Determinants of Environmental, Social and Corporate Governance (ESG) Disclosure: A Study of Indian Companies. International Journal of Disclosure and Governance 17: 208–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, Norman T., Ganesh Vaidyanathan, Kenneth A. Fox, and Mark Klassen. 2022. Making the Invisible Visible: Overcoming Barriers to ESG Performance with an ESG Mindset. Business Horizons 65: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchman, Mark C. 1995. Approaches and Strategic Managing Legitimacy. Academy of Management Review 20: 571–610. Available online: https://journals.aom.org/doi/abs/10.5465/AMR.1995.9508080331 (accessed on 1 August 2022). [CrossRef]

- Tilling, Matthew V., and Carol A. Tilt. 2010. The Edge of Legitimacy: Voluntary Social and Environmental Reporting in Rothmans’ 1956-1999 Annual Reports. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 23: 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilas, Pablo, Laura Andreu, and José Luis Sarto. 2022. Cluster Analysis to Validate the Sustainability Label of Stock Indices: An Analysis of the Inclusion and Exclusion Processes in Terms of Size and ESG Ratings. Journal of Cleaner Production 330: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Fengyan, and Ziyuan Sun. 2022. Does the Environmental Regulation Intensity and ESG Performance Have a Substitution Effect on the Impact of Enterprise Green Innovation: Evidence from China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 8558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasiuzzaman, Shaista, Salihu Aramide Ibrahim, and Farahiyah Kawi. 2022. Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Disclosure and Fi Rm Performance: Does National Culture Matter? Meditari Accountancy Research 30: 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weston, Rebecca, and Paul A. Gore. 2006. A Brief Guide to Structural Equation Modeling. The Counseling Psychologist 34: 719–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Ellen Pei yi, and Bac Van Luu. 2021. International Variations in ESG Disclosure—Do Cross-Listed Companies Care More? International Review of Financial Analysis 75: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Ellen Pei yi, Christine Qian Guo, and Bac Van Luu. 2018. Environmental, Social and Governance Transparency and Firm Value. Business Strategy and the Environment 27: 987–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Jianzhuang, Muhammad Usman Khurram, and Lifeng Chen. 2022. Can Green Innovation Affect ESG Ratings and Financial Performance? Evidence from Chinese GEM Listed Companies. Sustainability 14: 8677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Measurement | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Foreign ownership | Percentage of foreign ownership of shares to the total number of issued shares. | (Al Amosh and Khatib 2021). |

| Family ownership | Percentage of family ownership of shares to the total number of issued shares. | (Al Amosh and Khatib 2021). |

| State ownership | Percentage of state ownership of shares to the total number of issued shares | (Al Amosh and Khatib 2021). |

| Public ownership | Percentage of public ownership of shares to the total number of issued shares | (Khan et al. 2012) |

| Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) disclosure | ESG score ranging from 0.1 to 100 | (GRI 2013) |

| Firm value | Tobin’s Q = (VMS + D)/TA Where: VMS = market value of all outstanding shares TA = company assets D = debt | (Lindenberg and Ross 1981) |

| Firm performance | ROA = EBIT/TA Where: ROA: return on assets EBIT: earnings before interest and tax TA: total assets | (Chan et al. 2019) |

| Audit committee | Number of people on the audit committee | (Nikulin et al. 2022) |

| Control variables | ||

| Size | Size = the natural logarithm (total assets) | (Aman and Nguyen 2013) |

| Leverage | Leverage = (long term borrowing + short term borrowing): total assets | (Aman and Nguyen 2013) |

| Variables | N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foreign ownership | 700 | 0.00 | 37.8 | 28.4 | 23.6 |

| Public ownership | 700 | 0.04 | 25.9 | 19.7 | 17.9 |

| State ownership | 700 | 0.00 | 68.2 | 13.9 | 8.7 |

| Family ownership | 700 | 0.00 | 45.3 | 16.5 | 9.3 |

| ESG | 700 | 8 | 72.8 | 39.2 | 14.5 |

| Audit committee | 700 | 2 | 4 | 3.4 | 2.3 |

| Variables | Cronbach’s Alpha | Rho A | Composite Reliability | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foreign ownership | 0.713 | 0.887 | 0.803 | 0.587 |

| Public ownership | 0.890 | 0,842 | 0.889 | 0.541 |

| State ownership | 0.846 | 0.924 | 0.863 | 0.617 |

| Family ownership | 0.789 | 0.873 | 0.876 | 0.500 |

| ESG | 0.823 | 0.801 | 0.815 | 0.589 |

| Audit committee | 0.831 | 0.899 | 0.885 | 0.625 |

| Hypotheses | Coefficient | p Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Foreign ownership → ESG | 0.30 | <0.01 | Accepted |

| Public ownership → ESG | 0.27 | 0.04 | Accepted |

| State ownership → ESG | 0.06 | 0.16 | Rejected |

| Family ownership → ESG | 0.16 | 0.19 | Rejected |

| ESG → firm value | 0.29 | 0.01 | Accepted |

| ESG → firm performance | 0.10 | 0.15 | Rejected |

| ESG → firm value → audit committee | 0.38 | <0.01 | Accepted |

| ESG → firm performance → audit committee | 0.01 | 0.32 | Rejected |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fuadah, L.L.; Mukhtaruddin, M.; Andriana, I.; Arisman, A. The Ownership Structure, and the Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Disclosure, Firm Value and Firm Performance: The Audit Committee as Moderating Variable. Economies 2022, 10, 314. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies10120314

Fuadah LL, Mukhtaruddin M, Andriana I, Arisman A. The Ownership Structure, and the Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Disclosure, Firm Value and Firm Performance: The Audit Committee as Moderating Variable. Economies. 2022; 10(12):314. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies10120314

Chicago/Turabian StyleFuadah, Luk Luk, Mukhtaruddin Mukhtaruddin, Isni Andriana, and Anton Arisman. 2022. "The Ownership Structure, and the Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Disclosure, Firm Value and Firm Performance: The Audit Committee as Moderating Variable" Economies 10, no. 12: 314. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies10120314

APA StyleFuadah, L. L., Mukhtaruddin, M., Andriana, I., & Arisman, A. (2022). The Ownership Structure, and the Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Disclosure, Firm Value and Firm Performance: The Audit Committee as Moderating Variable. Economies, 10(12), 314. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies10120314