Do Aid for Trade Flows Help Reduce the Shadow Economy in Recipient Countries?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Discussion on the Effect of AfT Flows on the Informal Economy

3. Model Specification

4. Brief Data Analysis

5. Econometric Approach

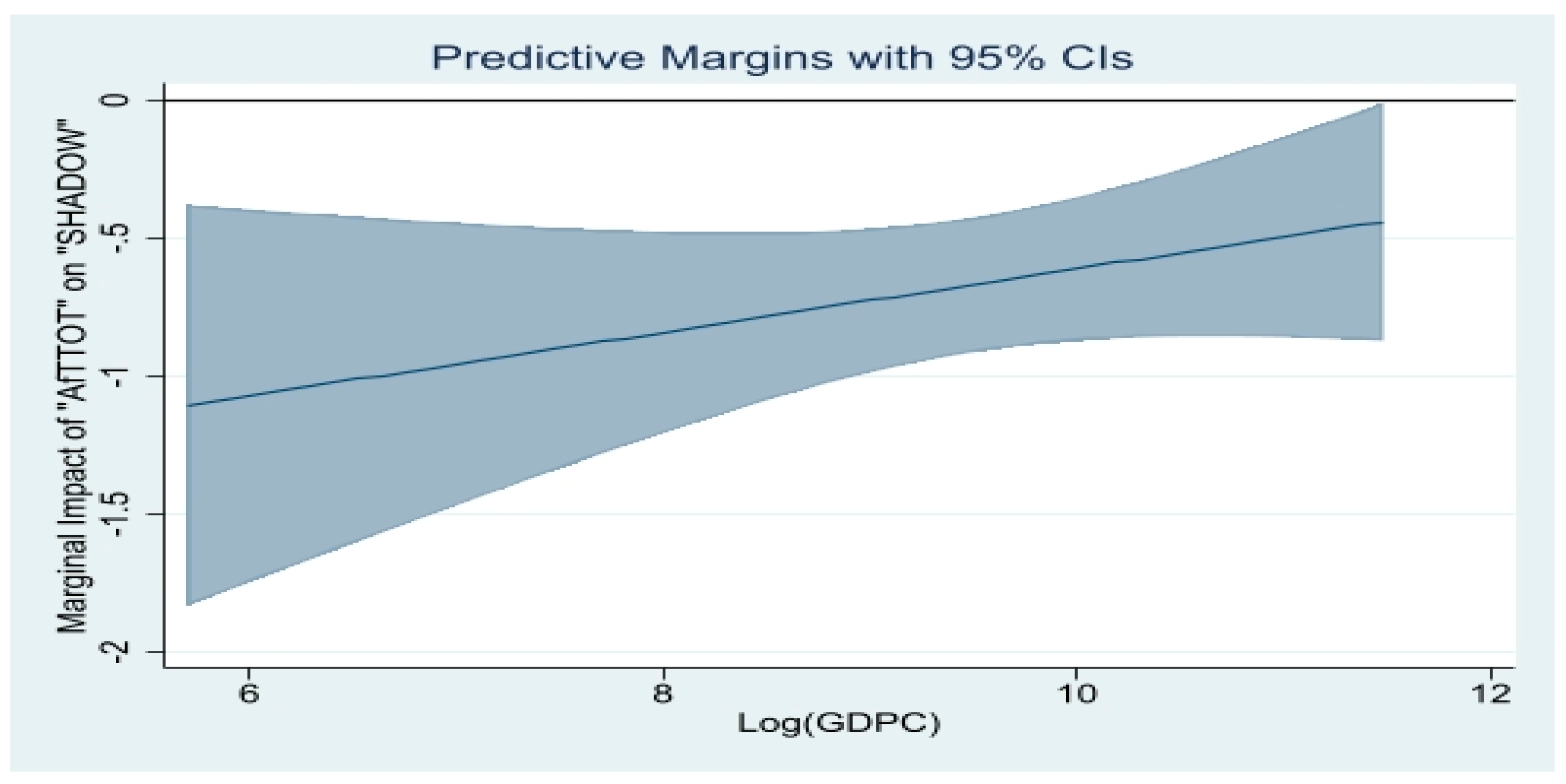

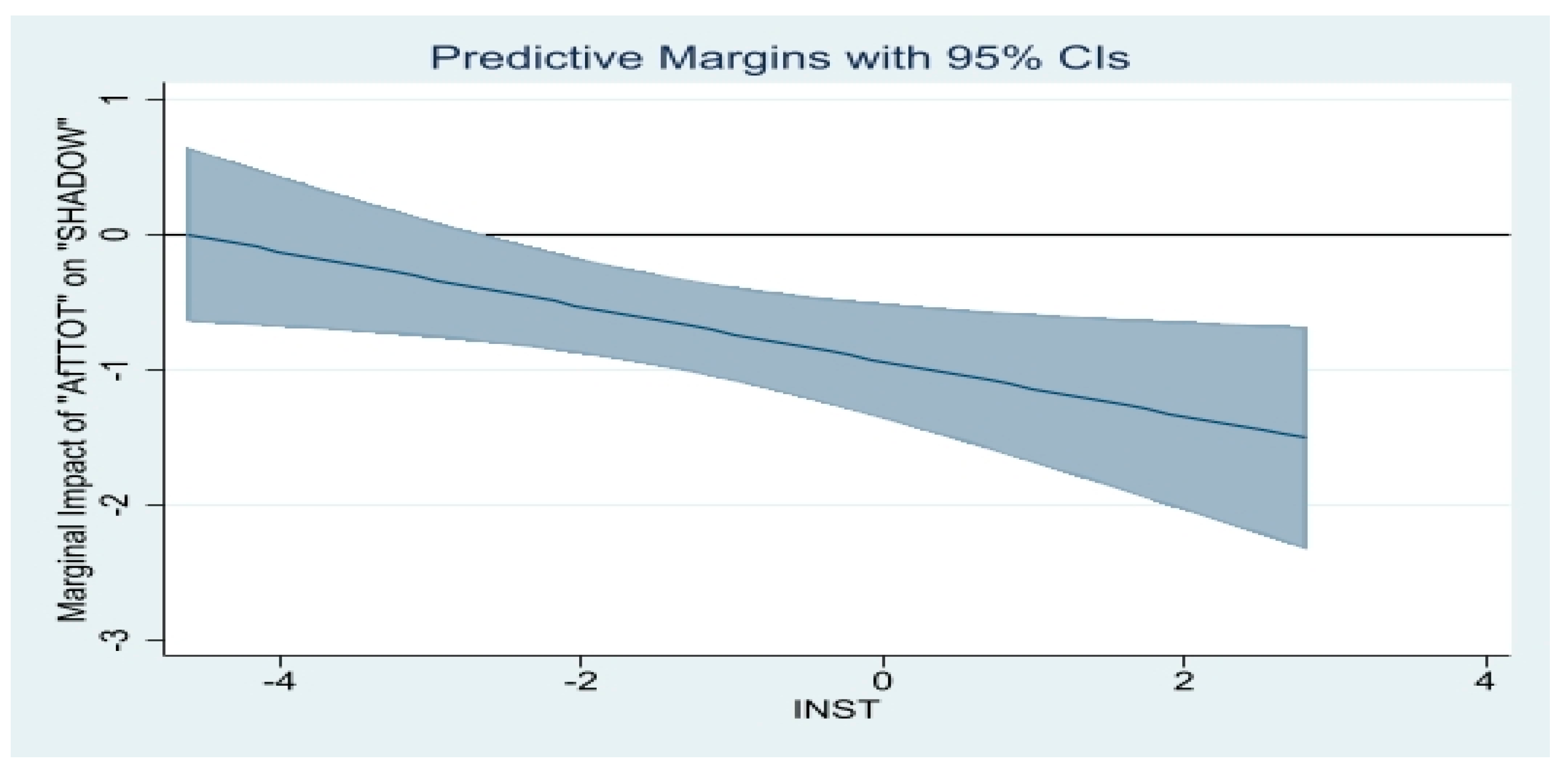

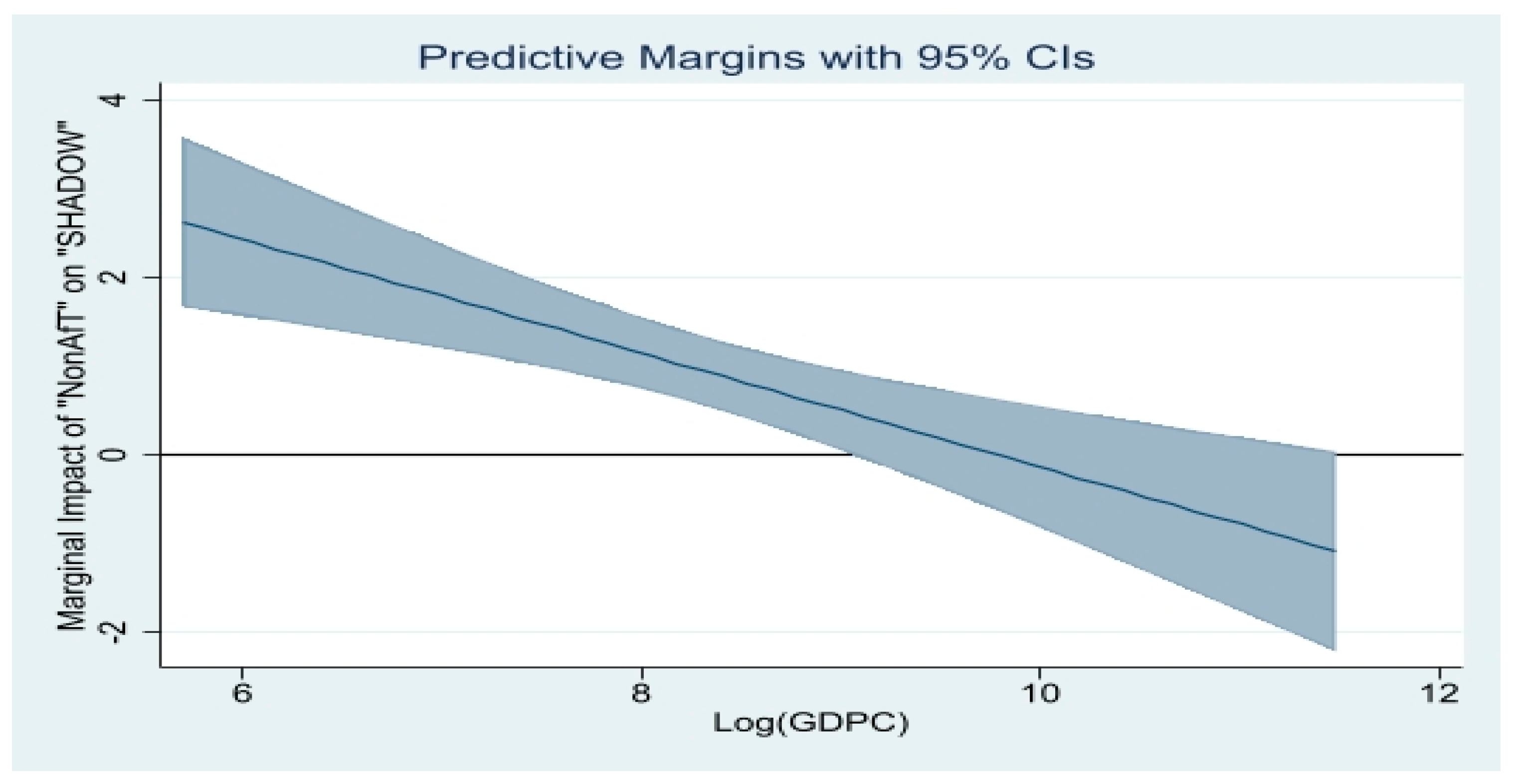

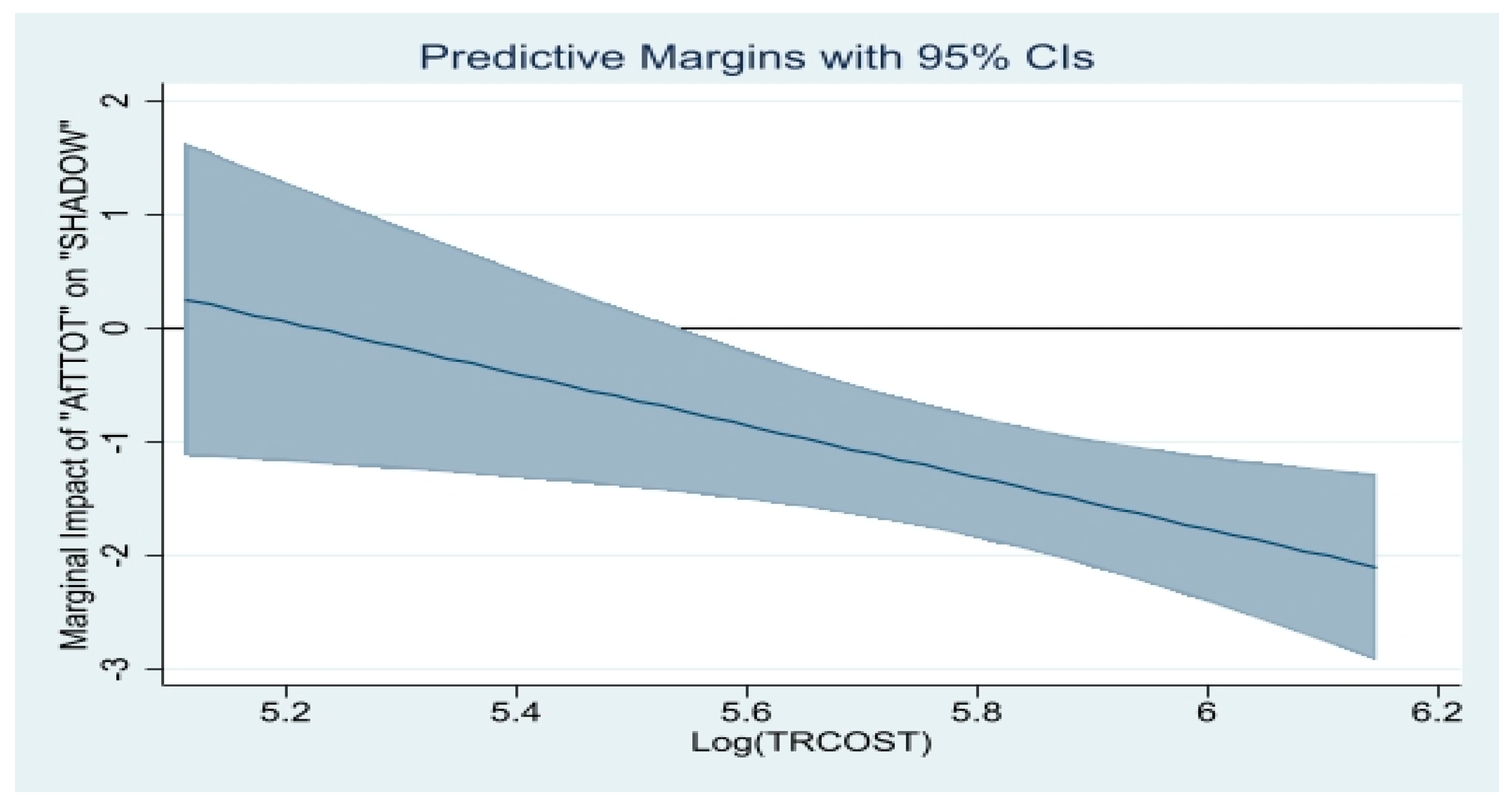

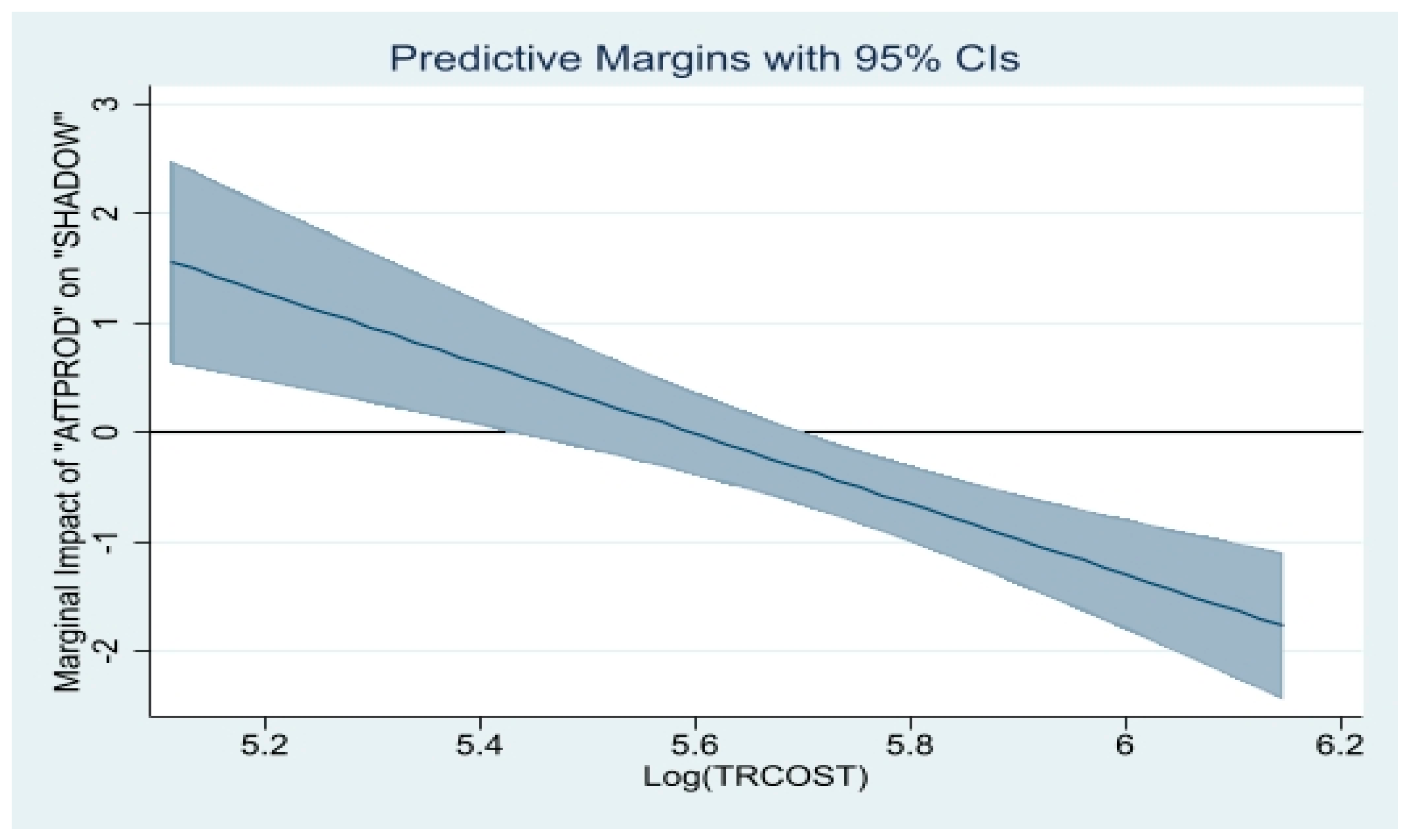

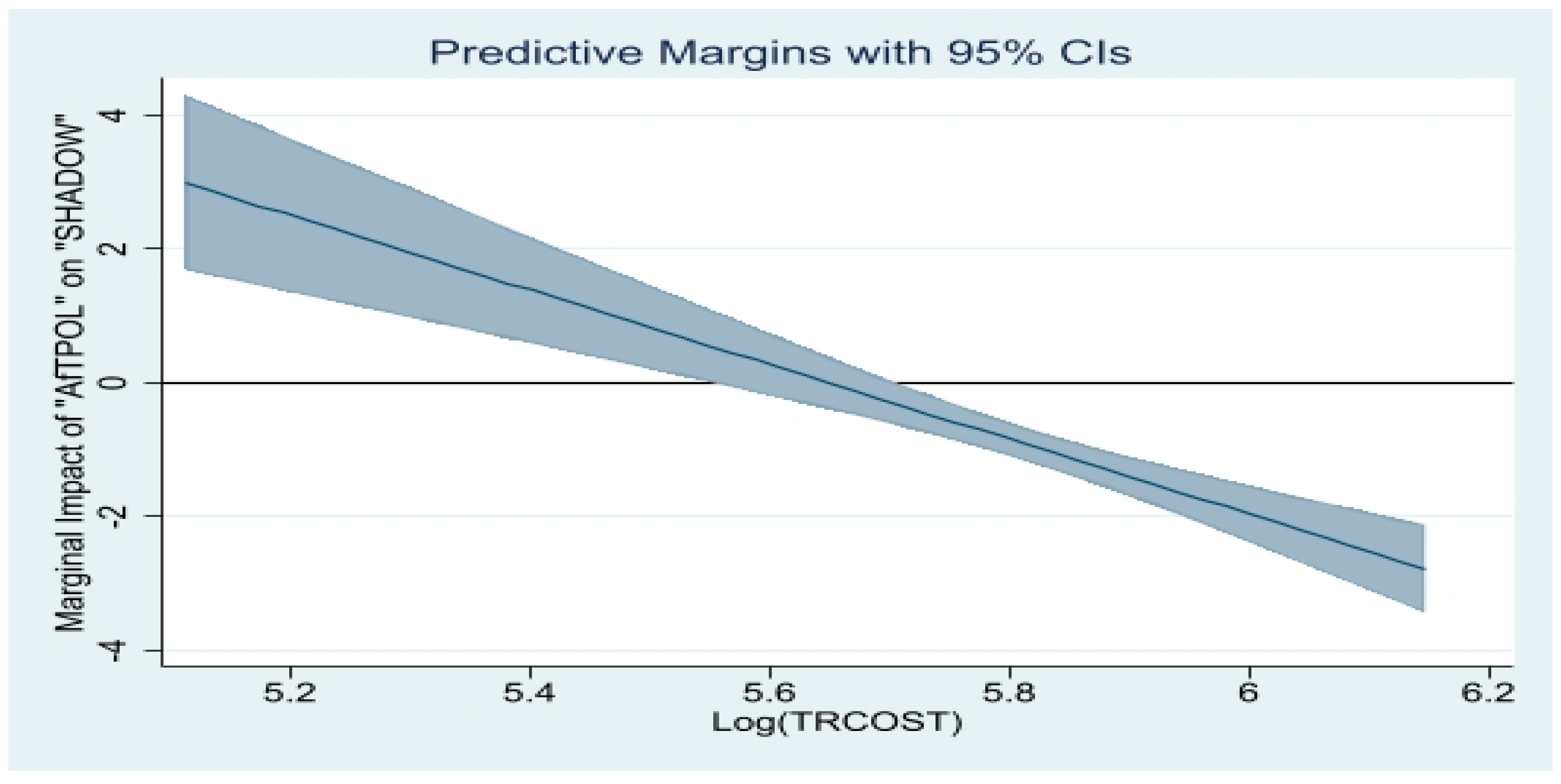

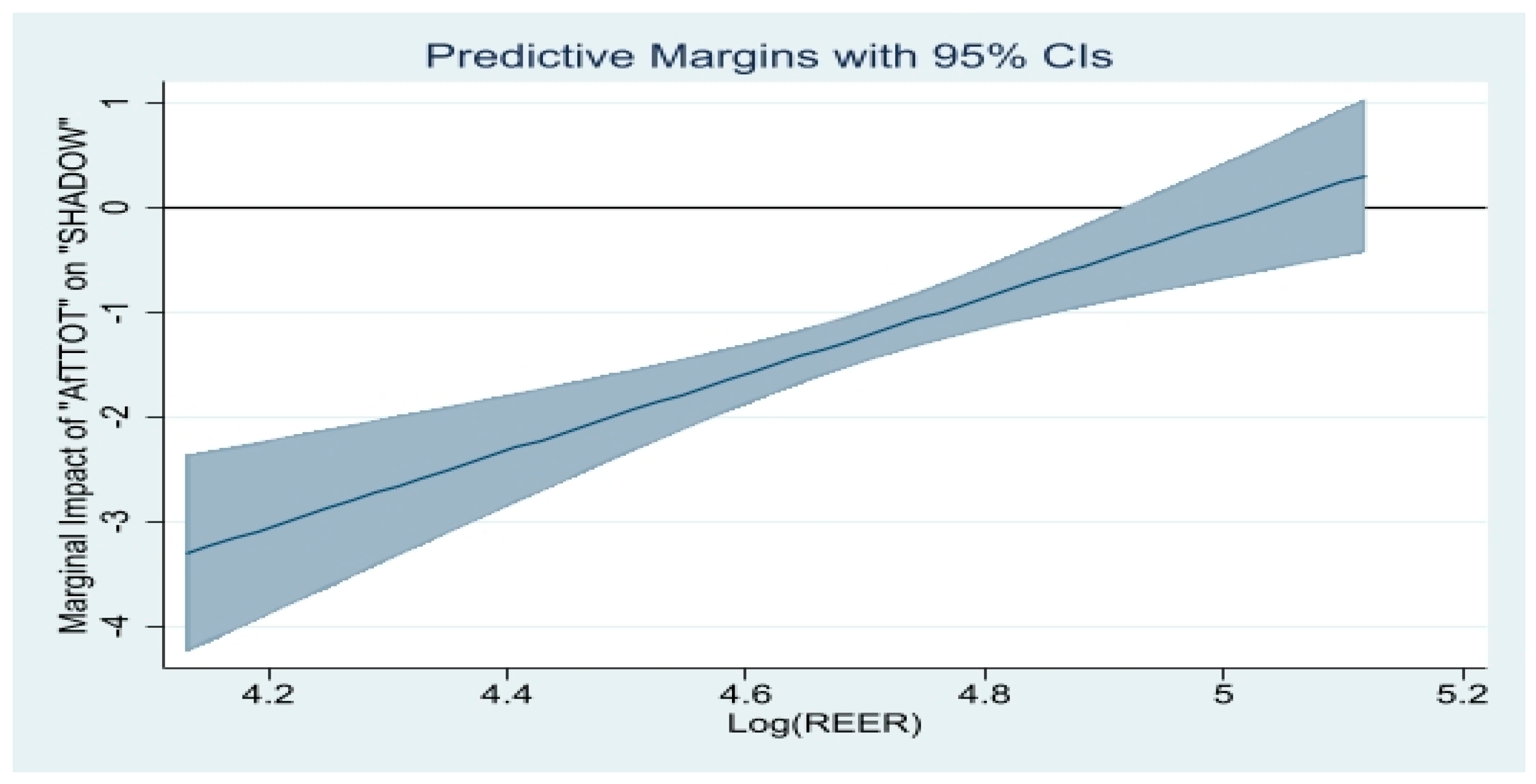

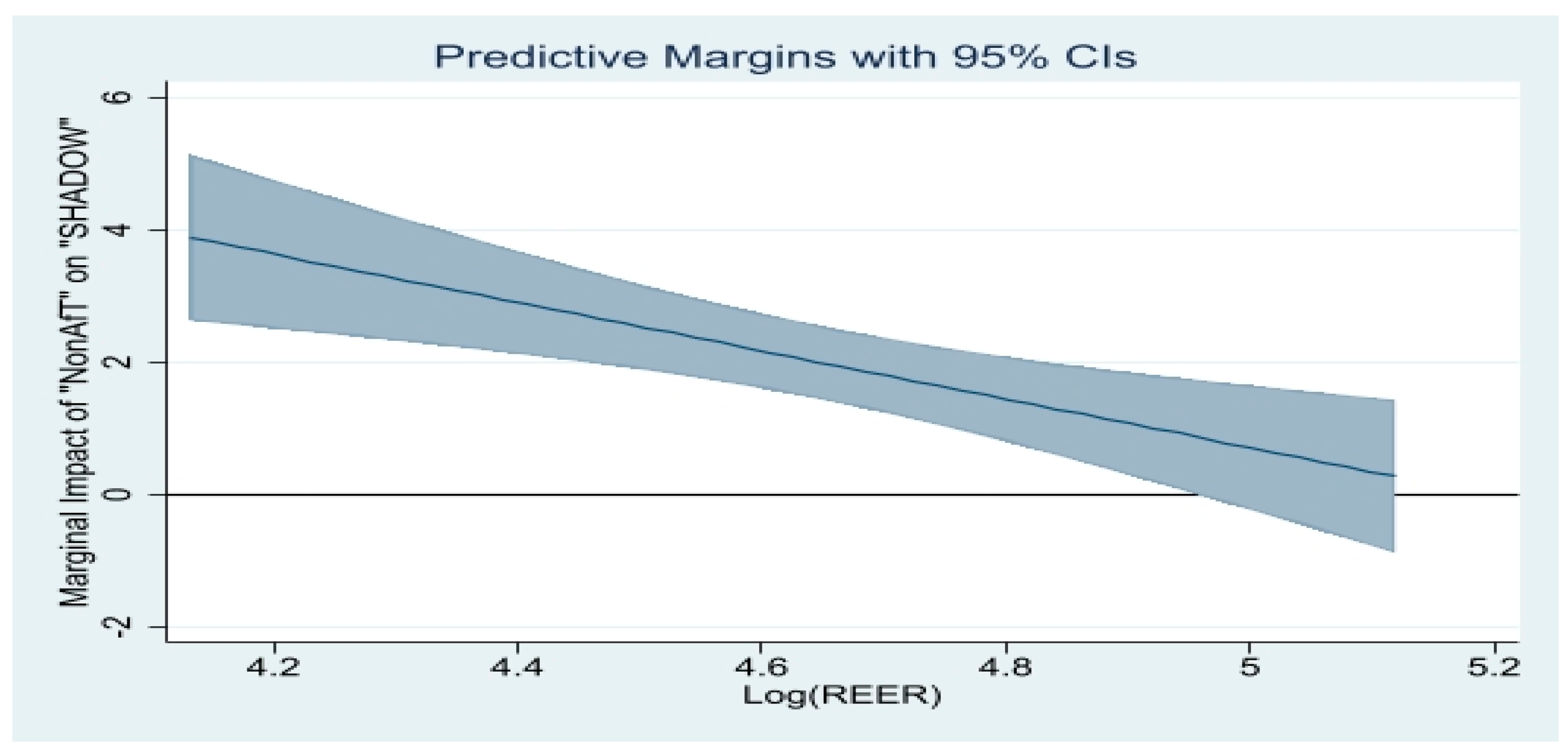

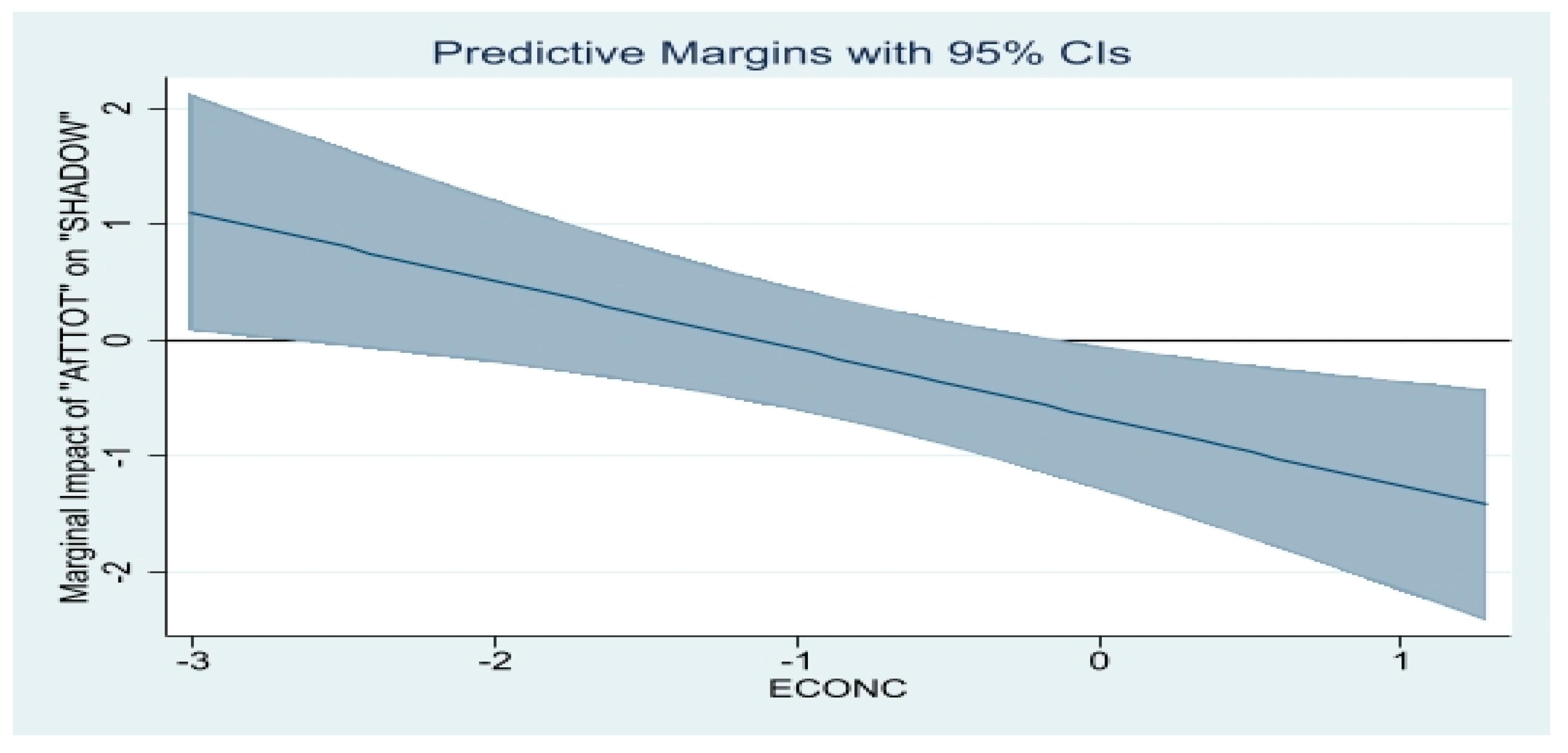

6. Interpretation of Empirical Results

| Variables | SHADOW | SHADOW | SHADOW | SHADOW |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Log(AfTTOT)t−1 | −1.201 *** | |||

| (0.371) | ||||

| Log(AfTINFRA)t−1 | −0.644 *** | |||

| (0.187) | ||||

| Log(AfTPROD)t−1 | −1.135 ** | |||

| (0.521) | ||||

| Log(AfTPOL)t−1 | −0.339 * | |||

| (0.192) | ||||

| Log(NonAfT)t−1 | 1.382 *** | 1.324 *** | 1.402 *** | 1.687 *** |

| (0.298) | (0.192) | (0.235) | (0.442) | |

| Log(GDPC)t−1 | −0.411 | −0.368 | −0.441 | −0.0953 |

| (0.648) | (0.616) | (0.678) | (0.417) | |

| FINDEVt−1 | −0.0436 * | −0.0551 *** | −0.0559 ** | −0.111 *** |

| (0.0221) | (0.0206) | (0.0246) | (0.0286) | |

| TAXBURDt−1 | −0.0577 * | −0.0535 * | −0.0627 * | −0.0720 |

| (0.0310) | (0.0293) | (0.0332) | (0.0453) | |

| INSTt−1 | 3.229 *** | 3.111 *** | 2.942 *** | 1.559 *** |

| (0.897) | (0.841) | (0.818) | (0.528) | |

| Constant | 38.28 *** | 28.53 *** | 36.60 *** | 14.56 *** |

| (10.05) | (8.581) | (12.75) | (2.430) | |

| Observations–Countries | 311–106 | 310–106 | 311–106 | 298–104 |

| Within R2 | 0.0901 | 0.0811 | 0.0815 | 0.1024 |

| Variables | SHADOW | SHADOW | SHADOW | SHADOW | SHADOW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| SHADOWt−1 | 0.633 *** | 0.618 *** | 0.599 *** | 0.557 *** | 0.579 *** |

| (0.0360) | (0.0355) | (0.0358) | (0.0370) | (0.0312) | |

| Log(AfTTOT) | −0.731 *** | −1.762 ** | |||

| (0.197) | (0.880) | ||||

| Log(AfTINFRA) | −0.615 *** | ||||

| (0.155) | |||||

| Log(AfTPROD) | −0.373 ** | ||||

| (0.182) | |||||

| Log(AfTPOL) | −0.498 *** | ||||

| (0.156) | |||||

| [Log(AfTTOT)]*[Log(GDPC)] | 0.115 | ||||

| (0.0916) | |||||

| Log(NonAfT) | 1.357 *** | 1.372 *** | 1.191 *** | 1.440 *** | 0.959 *** |

| (0.207) | (0.290) | (0.334) | (0.312) | (0.187) | |

| FINDEV | −0.0347 ** | −0.00912 | −0.0170 | −0.0336 ** | −0.0452 *** |

| (0.0163) | (0.0148) | (0.0135) | (0.0134) | (0.0127) | |

| INST | 1.208 *** | 1.061 *** | 0.737 ** | 0.829 *** | 0.944 *** |

| (0.321) | (0.292) | (0.373) | (0.315) | (0.276) | |

| Log(GDPC) | −2.029 *** | −2.122 *** | −2.284 *** | −2.516 *** | −4.296 ** |

| (0.334) | (0.310) | (0.308) | (0.311) | (1.716) | |

| TAXBURD | 0.0151 | 0.0304 | 0.00144 | 0.0632 *** | 0.0620 ** |

| (0.0273) | (0.0258) | (0.0238) | (0.0231) | (0.0248) | |

| Observations–Countries | 276–106 | 275–105 | 276–106 | 269–104 | 276–106 |

| Number of Instruments | 61 | 61 | 61 | 61 | 69 |

| AR1 (p-Value) | 0.0235 | 0.0202 | 0.0256 | 0.0295 | 0.0233 |

| AR2 (p-Value) | 0.3154 | 0.4284 | 0.3039 | 0.6994 | 0.2722 |

| OID (p-Value) | 0.6933 | 0.7790 | 0.8419 | 0.5175 | 0.5138 |

| Variables | SHADOW | SHADOW |

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| SHADOWt−1 | 0.537 *** | 0.584 *** |

| (0.0235) | (0.0281) | |

| Log(AfTTOT) | −0.937 *** | −0.559 *** |

| (0.218) | (0.178) | |

| Log(NonAfT) | 1.363 *** | 6.281 *** |

| (0.154) | (1.428) | |

| [Log(AfTTOT)]*[INST] | −0.203 ** | |

| (0.0892) | ||

| [Log(NonAfT)]*[Log(GDPC)] | −0.642 *** | |

| (0.170) | ||

| FINDEV | −0.0237 * | −0.0248 ** |

| (0.0139) | (0.0118) | |

| INST | 4.470 *** | 0.576 ** |

| (1.435) | (0.283) | |

| Log(GDPC) | −2.656 *** | 10.22 *** |

| (0.161) | (3.523) | |

| TAXBURD | 0.0301 | 0.0401 * |

| (0.0270) | (0.0207) | |

| Observations–Countries | 276–106 | 276–106 |

| Number of Instruments | 69 | 69 |

| AR1 (p-Value) | 0.0270 | 0.0137 |

| AR2 (p-Value) | 0.2170 | 0.2147 |

| OID (p-Value) | 0.9040 | 0.6528 |

| Variables | SHADOW | SHADOW | SHADOW | SHADOW | SHADOW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| SHADOWt−1 | 0.788 *** | 0.779 *** | 0.757 *** | 0.760 *** | 0.704 *** |

| (0.0363) | (0.0284) | (0.0271) | (0.0271) | (0.0226) | |

| Log(AfTTOT) | −1.533 *** | 11.90 ** | |||

| (0.306) | (5.422) | ||||

| Log(TRCOST) | 4.883 *** | 45.81 *** | 25.39 ** | 59.60 *** | 78.85 *** |

| (1.795) | (17.35) | (10.03) | (12.84) | (13.46) | |

| [Log(AfTTOT)]*[ Log(TRCOST)] | −2.279 ** | ||||

| (0.933) | |||||

| Log(AfTINFRA) | 5.768 * | ||||

| (3.214) | |||||

| [Log(AfTINFRA)]*[ Log(TRCOST)] | −1.161 ** | ||||

| (0.564) | |||||

| Log(AfTPROD) | 18.02 *** | ||||

| (4.099) | |||||

| [Log(AfTPROD)]*[ Log(TRCOST)] | −3.220 *** | ||||

| (0.715) | |||||

| Log(AfTPOL) | 31.53 *** | ||||

| (5.432) | |||||

| [Log(AfTPOL)]*[ Log(TRCOST)] | −5.580 *** | ||||

| (0.934) | |||||

| Log(NonAfT) | 1.915 *** | 1.907 *** | 1.351 *** | 1.156 *** | 1.770 *** |

| (0.436) | (0.372) | (0.417) | (0.286) | (0.372) | |

| FINDEV | −0.0448 *** | −0.0545 *** | −0.0477 *** | −0.0678 *** | −0.0490 *** |

| (0.0137) | (0.0109) | (0.00759) | (0.0127) | (0.0115) | |

| INST | 1.471 *** | 1.580 *** | 1.490 *** | 1.280 *** | 1.081 *** |

| (0.439) | (0.368) | (0.312) | (0.396) | (0.362) | |

| Log(GDPC) | −0.441 | −0.633 ** | −0.494 * | −0.585 ** | −1.045 *** |

| (0.331) | (0.278) | (0.280) | (0.252) | (0.284) | |

| TAXBURD | 0.0806 *** | 0.0521 ** | 0.0315 | 0.0514 ** | 0.0501 * |

| (0.0282) | (0.0261) | (0.0308) | (0.0219) | (0.0259) | |

| Observations–Countries | 251–96 | 251–96 | 250–95 | 251–96 | 245–94 |

| Number of Instruments | 54 | 60 | 61 | 61 | 61 |

| AR1 (p-Value) | 0.0215 | 0.0236 | 0.0183 | 0.0229 | 0.0224 |

| AR2 (p-Value) | 0.3005 | 0.2313 | 0.2862 | 0.1865 | 0.3734 |

| OID (p-Value) | 0.7368 | 0.5669 | 0.7373 | 0.5167 | 0.8248 |

| Variables | SHADOW | SHADOW |

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| SHADOWt−1 | 0.870 *** | 0.748 *** |

| (0.0296) | (0.0165) | |

| Log(AfTTOT) | −1.542 *** | −18.44 *** |

| (0.276) | (3.881) | |

| Log(REER) | 0.206 | 3.736 |

| (1.871) | (13.02) | |

| [Log(AfTTOT)]*[Log(REER)] | 3.662 *** | |

| (0.827) | ||

| [Log(NonAfT)]*[Log(REER)] | −3.654 *** | |

| (1.105) | ||

| Log(NonAfT) | 2.947 *** | 18.98 *** |

| (0.457) | (5.145) | |

| FINDEV | −0.0133 | −0.00733 |

| (0.0155) | (0.0115) | |

| INST | 1.425 *** | 0.487 ** |

| (0.329) | (0.229) | |

| Log(GDPC) | −1.117 *** | −1.849 *** |

| (0.328) | (0.238) | |

| TAXBURD | −0.0231 | 0.0374 * |

| (0.0278) | (0.0208) | |

| Observations–Countries | 267–102 | 267–102 |

| Number of Instruments | 54 | 64 |

| AR1 (p-Value) | 0.0437 | 0.0407 |

| AR2 (p-Value) | 0.6484 | 0.3907 |

| OID (p-Value) | 0.8190 | 0.5944 |

7. Further Analysis

8. Conclusions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variables | Definition | Source |

|---|---|---|

| SHADOW | This was the measure of the size of the shadow economy. It was computed by Medina and Schneider (2018) using the multiple indicators, multiple causes (MIMIC) method. The latter extracts covariance information from observable variables classified as causes or indicators of the latent shadow economy (see Schneider et al. 2010 for more details on this approach). | Data extracted from Medina and Schneider (2018) |

| AfTTOT, AfTINFRA, AfTPROD, AfTPOL | “AfTTOT” was the total real gross disbursements of total Aid for Trade. “AfTINFRA” was the real gross disbursements of Aid for Trade allocated to the buildup of economic infrastructure. “AfTPROD” was the real gross disbursements of Aid for Trade for building productive capacities. “AfTPOL” was the real gross disbursements of aid allocated for trade policies and regulation. All four AfT variables are expressed in constant 2019 prices in US dollars. | Author’s calculation based on data extracted from the OECD statistical database on development, in particular the OECD/DAC-CRS (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development/Donor Assistance Committee)-Credit Reporting System (CRS). The Aid for Trade data covered the following three main categories (the CRS codes are in brackets): Aid for Trade for Economic Infrastructure (“AfTINFRA”), which included transport and storage (210), communications (220), and energy generation and supply (230); Aid for Trade for Building Productive Capacity (“AfTPROD”), which included banking and financial services (240), business and other services (250), agriculture (311), forestry (312), fishing (313), industry (321), mineral resources and mining (322), and tourism (332); and Aid for Trade policy and regulations (“AfTPOL”), which included trade policy and regulations and trade-related adjustments (331). |

| NonAfT | This was the measure of the development aid allocated to other sectors in the economy than the trade sector. It was computed as the difference between the gross disbursements of total ODA and the gross disbursements of total Aid for Trade (both being expressed in constant 2019 prices in US dollars). | Author’s calculation based on data extracted from the OECD/DAC-CRS database. |

| TRCOST | This was the indicator of the average comprehensive (overall) trade costs calculated for a given country in a given year as the average of the bilateral overall trade costs on goods across all trading partners of that country. Data on bilateral overall trade costs were computed by Arvis et al. (2012, 2016) following the approach proposed by Novy (2013). Arvis et al. (2012, 2016) built on the definition of trade costs provided by Anderson and Van Wincoop (2004) and considered bilateral comprehensive trade costs as all costs involved in trading goods (agricultural and manufactured goods) internationally with another partner (i.e., bilaterally) relative to those involved in trading goods domestically (i.e., intranationally). Hence, the bilateral comprehensive trade costs indicator captured trade costs in its wider sense, including not only international transport costs and tariffs, but also the other trade costs components discussed in Anderson and Van Wincoop (2004), such as direct and indirect costs associated with differences in languages and currencies as well as cumbersome import or export procedures. Higher values of the indicator of average overall trade costs indicated an increase in the overall trade costs. Detailed information on the methodology used to compute the bilateral comprehensive trade costs can be found in the short explanatory note accessible online at: https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/d8files/Trade%20Cost%20Database%20-%20User%20note.pdf (data collected in July 2021) | Author’s calculation using the indicator of the overall trade costs developed using the ESCAP-World Bank Trade Cost Database. Accessible online at: https://www.unescap.org/resources/escap-world-bank-trade-cost-database. (data collected in July 2021) |

| REER | This was the measure of the real effective exchange rate (based on the consumer price index) computed using a nominal effective exchange rate based on 66 trading partners. An increase in the values of this index indicated an appreciation in the real effective exchange rate; i.e., an appreciation in the home currency against the basket of currencies of trading partners. | Bruegel datasets (see Darvas 2012a, 2012b). The datasets can be found online at: http://bruegel.org/publications/datasets/real-effective-exchange-rates-for-178-countries-a-new-database. (data collected in July 2021) |

| GDP | Gross domestic product (constant 2015 US dollars). | WDI |

| TAXBURD | This was the indicator of the tax burden. It was the average and marginal corporate and personal income taxation. Higher values of this indicator showed a greater burden of taxation; that is, higher average and marginal tax rates. | Data collected from the Heritage Foundation database (see Miller et al. 2021). |

| FINDEV | This was a proxy for financial development that was measured by the share of domestic credit to private sector by banks in the GDP (not expressed in percentage). | WDI |

| ECONC | This was the economic complexity index. It reflected the diversity and sophistication of a country’s export structure, and hence indicated the diversity and ubiquity of that country’s export structure. It was estimated using the data that connected countries to the products they exported and by applying the methodology in described in Hausmann and Hidalgo (2009). Higher values of this index reflected a greater economic complexity. | MIT’s Observatory of Economic Complexity (see https://oec.world/en/rankings/eci/hs6/hs96). (data collected in July 2021) |

| PCI | This was the overall productive capacity index. It measured the level of productive capacities along three pillars: “the productive resources, entrepreneurial capabilities and production linkages which together determine the capacity of a country to produce goods and services and enable it to grow and develop” (UNCTAD 2006). It was computed as a geometric average of eight domains or categories; namely, information communication and technologies, structural change, natural capital, human capital, energy, transport, the private sector, and institutions. Each category index was obtained using the principal components extracted from the underlying indicators weighted by their capacity to explain the variance of the original data. The category indices were normalized into a 0–100 interval (see UNCTAD 2020). | United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) Statistics portal: https://unctadstat.unctad.org/wds/ReportFolders/reportFolders.aspx. (data collected in July 2021) |

| INST | This was the variable that captured the institutional quality. It was computed by extracting the first principal component (based on a factor analysis) of the following six indicators of governance: political stability and absence of violence/terrorism, regulatory quality, the rule of law, government effectiveness, voice and accountability, and corruption. Higher values of the index “INST” were associated with better governance and institutional quality, while lower values reflected worse governance and institutional quality. | Data on the components of “INST” variables were extracted from World Bank governance indicators developed by Kaufmann et al. (2010) and updated recently. See online at: https://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi. (data collected in July 2021) |

| Variable | Observations | Mean | Standard Deviation | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHADOW | 276 | 30.947 | 12.013 | 8.440 | 67.530 |

| AfTTOT | 276 | 198,000,000 | 349,000,000 | 62,612 | 2,910,000,000 |

| AfTINFRA | 275 | 111,000,000 | 209,000,000 | 43,272 | 2,070,000,000 |

| AfTPROD | 276 | 83,100,000 | 163,000,000 | 19,340 | 1,870,000,000 |

| AfTPOL | 271 | 3,823,256 | 7,748,847 | −29447 | 93,200,000 |

| NonAfT | 276 | 673,000,000 | 1,030,000,000 | 2,413,728 | 12,400,000,000 |

| TRCOST | 251 | 325.456 | 57.521 | 166.173 | 467.268 |

| REER | 267 | 107.016 | 14.004 | 62.274 | 167.126 |

| ECONC | 224 | −0.477 | 0.767 | −3.013 | 1.280 |

| PCI | 262 | 26.903 | 5.214 | 13.003 | 39.231 |

| FINDEV | 276 | 35.544 | 28.228 | 1.977 | 146.416 |

| INST | 276 | −0.993 | 1.583 | −4.614 | 2.967 |

| GDPC | 276 | 11,802.550 | 17,739.310 | 299.152 | 109,331.600 |

| TAXBURD | 276 | 76.974 | 11.626 | 39.633 | 99.900 |

| Full Sample | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Albania | Dominican Republic | Micronesia, Fed. Sts. | Tanzania |

| Algeria | Ecuador | Moldova | Thailand |

| Antigua and Barbuda | Egypt, Arab Rep. | Morocco | Tonga |

| Argentina | El Salvador | Mozambique | Trinidad and Tobago |

| Bangladesh | Equatorial Guinea | Namibia | Tunisia |

| Barbados | Eritrea | Nepal | Turkey |

| Belarus | Fiji | Nicaragua | Uganda |

| Belize | Georgia | Niger | Uruguay |

| Benin | Ghana | Nigeria | Uzbekistan |

| Bhutan | Grenada | North Macedonia | Vanuatu |

| Bolivia | Guatemala | Oman | West Bank and Gaza |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | Guinea-Bissau | Pakistan | Yemen, Rep. |

| Botswana | Guyana | Panama | Zambia |

| Brazil | Honduras | Papua New Guinea | |

| Burkina Faso | Indonesia | Paraguay | |

| Burundi | Iran, Islamic Rep. | Peru | |

| Cabo Verde | Iraq | Philippines | |

| Cambodia | Jamaica | Rwanda | |

| Cameroon | Kosovo | Samoa | |

| Central African Republic | Kyrgyz Republic | Saudi Arabia | |

| Chad | Lao PDR | Serbia | |

| Chile | Lebanon | Seychelles | |

| China | Lesotho | Solomon Islands | |

| Colombia | Liberia | South Africa | |

| Comoros | Libya | South Sudan | |

| Congo, Dem. Rep. | Malawi | St. Kitts and Nevis | |

| Congo, Rep. | Malaysia | St. Lucia | |

| Cote d’Ivoire | Mali | St. Vincent and the Grenadines | |

| Croatia | Mauritania | Sudan | |

| Djibouti | Mauritius | Syrian Arab Republic | |

| Dominica | Mexico | Tajikistan | |

| 1 | Afonso et al. (2020), however, reported evidence of no significant effect of the shadow economy on economic growth. |

| 2 | The United Nations defined the category of LDCs as countries in the world that are the poorest and most vulnerable to exogenous economic and environmental shocks. The list of LDCs and criteria used for the inclusion of a country in the LDC category and the graduation of a country from this category are available online at: https://www.un.org/ohrlls/content/least-developed-countries (accessed on 1 July 2022). |

| 3 | Hard infrastructure can include highways, railroads, ports, etc.; soft infrastructure refers to transparency, customs efficiency, and institutional reforms (Portugal-Perez and Wilson 2012, p. 1296). |

| 4 | This bias is referred to as the Nickell bias (Nickell 1981). |

| 5 | In the full sample, the values of the variable “INST” ranged between −4.6 and 2.97 (see Table A3). |

| 6 | Values of the variable representing the real per capita income in the full sample ranged from USD 299.15 to USD 109331.60 (see Table A3). |

| 7 | Values of the variable representing the overall trade costs in the full sample ranged from 166.2 to 467.3 (see Table A3). |

| 8 | Values of the variable capturing the real effective exchange rate range ranged between 62.3 and 167.1 (see Table A2). |

| 9 | The low ubiquity of products reflects a situation in which products that are exported cannot be easily reproduced by other countries because the production of such goods requires a set of exclusive capabilities. |

| 10 | Note that we could not include the trade costs indicator (or the economic sophistication indicator) here, given that AfT interventions affect economic sophistication (and ultimately the size of the shadow economy) through their effect on trade costs. |

| 11 | Over the full sample, the values of the indicator “ECONC” ranged from −3.01 to 1.28 (see Table A2). |

| 12 | Over the full sample, the values of the indicator “PCI” ranged from 13 to 39.2 (see Table A2). |

References

- Abeberese, Ama Baafra, and Mary Chen. 2022. Intranational trade costs, product scope and productivity: Evidence from India’s Golden Quadrilateral project. Journal of Development Economics 156: 102791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, Oscar, Pedro Cunha Neves, and Tiago Pinto. 2020. The non-observed economy and economic growth: A meta-analysis. Economic Systems 44: 100746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, Shilpa, Brian Giera, Dahyeon Jeong, Jonathan Robinson, and Alan Spearot. 2022. Market Access, Trade Costs, and Technology Adoption: Evidence from Northern Tanzania. Paper formally published in 2018 as Working Paper 25253, NBER, Cambridge, MA—and updated in 2022. Available online: https://people.ucsc.edu/~jmrtwo/market_access.pdf (accessed on 17 October 2022).

- Ali, Salamat, and Chris Milner. 2016. Narrow and Broad Perspectives on Trade Policy and Trade Costs: How to Facilitate Trade in Madagascar. The World Economy 39: 1917–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Alonso-Borrego, Cesar, and Manuel Arellano. 1999. Symmetrically normalized instrumental-variable estimation using panel data. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics 17: 36–49. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, James E., and Douglas Marcouiller. 2002. Insecurity and the pattern of trade: An empirical investigation. Review of Economics and Statistics 84: 342–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, James E., and Eric Van Wincoop. 2004. Trade Costs. Journal of Economic Literature 42: 691–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, Manuel, and Stephen Bond. 1991. Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Review of Economic Studies 58: 277–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsić, Milojko, Mihail Arandarenko, Branko Radulović, Saša Ranđelović, and Irena Janković. 2015. Causes of the Shadow Economy. In Formalizing the Shadow Economy in Serbia. Edited by Gorana Krstic and Friedrich Schneider. Contributions to Economics. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvis, Jean-François, Yann Duval, Ben Shepherd, and Chorthip Utoktham. 2012. Trade Costs in the Developing World: 1995–2010. ARTNeT Working Papers, No. 121/December 2012 (AWP No. 121). Bangkok: Asia-Pacific Research and Training Network on Trade, ESCAP. [Google Scholar]

- Arvis, Jean-Francois, Yann Duval, Ben Shepherd, Chorthip Utoktham, and Anasuya Raj. 2016. Trade Costs in the Developing World: 1996–2010. World Trade Review 15: 451–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkin, David, and Dave Donaldson. 2022. The role of trade in economic development. Chapter 1. In Handbook of International Economics. Edited by Gita Gopinath, Elhanan Helpman and Kenneth Rogoff. Amsterdam: Elsevier, vol. 5, pp. 1–59. [Google Scholar]

- Bacchetta, M., E. Ernst, and J. P. Bustamante. 2009. Globalization and Informal Jobs in Developing Countries. International Labor Organization and World Trade Organization. Geneva: WTO Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Bas, Maria, and Vanessa Strauss-Kahn. 2015. Input-trade liberalization, export prices and quality upgrading. Journal of International Economics 95: 250–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benziane, Yakoub, Siong Hook Law, Anitha Rosland, and Muhammad Daaniyall Abd Rahman. 2022. Aid for trade initiative 16 years on: Lessons learnt from the empirical literature and recommendations for future directions. Journal of International Trade Law and Policy 21: 79–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdiev, Aziz N., and James W. Saunoris. 2016. Financial development and the shadow economy: A panel VAR analysis. Economic Modelling 57: 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdiev, Aziz N., and James W. Saunoris. 2018. Does globalisation affect the shadow economy? The World Economy 41: 222–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdiev, Aziz N., Cullen Pasquesi-Hill, and James W. Saunoris. 2015. Exploring the dynamics of the shadow economy across US states. Applied Economics 47: 6136–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdiev, Aziz N., James W. Saunoris, and Friedrich Schneider. 2018a. Give me liberty, or I will produce underground: Effects of economic freedom on the shadow economy. Southern Economic Journal 85: 537–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdiev, Aziz N., James W. Saunoris, and Friedrich Schneider. 2020. Poverty and the shadow economy: The role of governmental institutions. The World Economy 43: 921–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdiev, Aziz N., Rajeev K. Goel, and James W. Saunoris. 2018b. Corruption and the shadow economy: One-way or two-way street? The World Economy 41: 3221–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, Andrew B., J. Bradford Jensen, and Peter K. Schott. 2006. Trade costs, firms and productivity. Journal of Monetary Economics 53: 917–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardini Papalia, Rosa, and Silvia Bertarelli. 2015. Trade Costs in Bilateral Trade Flows: Heterogeneity and Zeroes in Structural Gravity Models. The World Economy 38: 1744–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beverelli, Cosimo, Simon Neumueller, and Robert Teh. 2015. Export Diversification Effects of the WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement. World Development 76: 293–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birchler, Kassandra, and Katharina Michaelowa. 2016. Making aid work for education in developing countries: An analysis of aid effectiveness for primary education coverage and quality. International Journal of Educational Development 48: 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, Amit K., Mohammad Reza Farzanegan, and Marcel Thum. 2012. Pollution, shadow economy and corruption: Theory and evidence. Ecological Economics 75: 114–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, Richard, and Stephen Bond. 1998. Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics 87: 115–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, Stephen R. 2002. Dynamic panel data models: A guide to micro data methods and practice. Portuguese Economic Journal 1: 141–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhn, Andreas, and Mohammad Reza Farzanegan. 2013. Impact of education on the shadow economy: Institutions matter. Economics Bulletin 33: 2052–63. [Google Scholar]

- Busse, Matthias, Ruth Hoekstra, and Jens Königer. 2012. The impact of aid for trade facilitation on the costs of trading. Kyklos 65: 143–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cali, Massimiliano, and Dirk Willem Te Velde. 2011. Does Aid for Trade Really Improve Trade Performance? World Development 39: 725–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canh, Nguyen Phuc, and Su Dinh Thanh. 2020a. Financial development and the shadow economy: A multi-dimensional analysis. Economic Analysis and Policy 67: 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canh, Phuc Nguyen, and Su Dinh Thanh. 2020b. Exports and the shadow economy: Non-linear effects. The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development 29: 865–90. [Google Scholar]

- Canh, Phuc Nguyen, Christophe Schinckus, and Su Dinh Thanh. 2021. What are the drivers of shadow economy? A further evidence of economic integration and institutional quality. The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development 30: 47–67. [Google Scholar]

- Carmignani, Fabrizio. 2015. The Curse of Being Landlocked: Institutions Rather than Trade. The World Economy 38: 1594–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Natalie, and Luciana Juvenal. 2022. Markups, quality, and trade costs. Journal of International Economics 137: 103627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvas, Zsolt. 2012a. Real Effective Exchange Rates for 178 Countries: A New Database. Working Paper 2012/06. Belgium: Bruegel. [Google Scholar]

- Darvas, Zsolt. 2012b. Compositional Effects on Productivity, Labour cost and Export Adjustment. Policy Contribution 2012/11. Belgium: Bruegel. [Google Scholar]

- Deardorff, Alan V. 2014. Local comparative advantage: Trade costs and the pattern of trade. International Journal of Economic Theory 10: 9–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defever, Fabrice, Michele Imbruno, and Richard Kneller. 2020. Trade liberalization, input intermediaries and firm productivity: Evidence from China. Journal of International Economics 126: 103329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, Allen, and Ben Shepherd. 2011. Trade facilitation and export diversification. The World Economy 34: 101–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diakantoni, Antonia, Hubert Escaith, Michael Roberts, and Thomas Verbeet. 2017. Accumulating Trade Costs and Competitiveness in Global Value Chains. WTO Working Paper ERSD-2017-02. Geneva: World Trade Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Dixit, Avinash K., and Robert S. Pindyck. 1994. Investment under Uncertainty number 5474. In Economics Books. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dreher, Axel, and Friedrich Schneider. 2010. Corruption and the shadow economy: An empirical analysis. Public Choice 144: 215–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreher, Axel, Christos Kotsogiannis, and Steve McCorriston. 2009. How do institutions affect corruption and the shadow economy? International Tax and Public Finance 16: 773–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, John C., and Aart C. Kraay. 1998. Consistent Covariance Matrix Estimation with Spatially Dependent Panel Data. Review of Economics and Statistics 80: 549–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitrescu, Bogdan Andrei, Meral Kagitci, and Cosmin-Octavian Cepoi. 2022. Nonlinear effects of public debt on inflation. Does the size of the shadow economy matter? Finance Research Letters 46: 102255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eilat, Yair, and Clifford Zinnes. 2002. The Shadow Economy in Transition Countries: Friend or Foe? A Policy Perspective. World Development 30: 1233–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, Octavio, Olivier Lamotte, Ana Colovic, and Pierre-Xavier Meschi. 2022. Impact of sourcing from the informal economy on the export likelihood and performance of emerging economy firms. Industrial and Corporate Change 31: 610–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorini, Matteo, Marco Sanfilippo, and Asha Sundaram. 2021. Trade liberalization, roads and firm productivity. Journal of Development Economics 153: 102712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, Eric, Simon Johnson, Daniel Kaufmann, and Pablo Zoido-Lobaton. 2000. Dodging the grabbing hand: The determinants of unofficial activity in 69 countries. Journal of Public Economics 76: 459–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fugazza, Marco, and Norbert M. Fiess. 2010. Trade Liberalization and Informality: New Stylized Facts. Policy Issues in International Trade and Commodities. Study Series No. 43; Geneva: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. [Google Scholar]

- Gërxhani, Klarita, and Herman G. Van de Werfhorst. 2013. The effect of education on informal sector participation in a post-communist country. European Sociological Review 29: 464–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gërxhani, Klarita. 2004. The informal sector in developed and less developed countries: A literature survey. Public Choice 120: 267–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnangnon, Sèna Kimm. 2018. Aid for trade and trade policy in recipient countries. The International Trade Journal 32: 439–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnangnon, Sèna Kimm. 2019a. Aid for trade and export diversification in recipient-countries. The World Economy 42: 396–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnangnon, Sèna Kimm. 2019b. Does the Impact of Aid for Trade on Export Product Diversification depend on Structural economic policies in Recipient-Countries? Economic Issues 24: 59–87. [Google Scholar]

- Gnangnon, Sèna Kimm. 2019c. Aid for Trade and Employment in Developing Countries: An Empirical Evidence. Labour 33: 77–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnangnon, Sèna Kimm. 2020a. Aid for Trade and sectoral employment diversification in recipient-countries. Economic Change and Restructuring 53: 265–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnangnon, Sèna Kimm. 2020b. Aid for Trade Flows and Wage Inequality in the Manufacturing Sector of Recipient-Countries. Journal of Economic Integration 35: 643–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnangnon, Sèna Kimm. 2020c. Development Aid and Regulatory Policies in Recipient-Countries: Is there a Specific Effect of Aid for Trade? Economics Bulletin 40: 316–37. [Google Scholar]

- Gnangnon, Sèna Kimm. 2021a. Aid for Trade and Import Product Diversification: To What Extent Does Export Product Diversification Matter? Economic Issues 26: 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Gnangnon, Sèna Kimm. 2021b. Aid for Trade and services export diversification in recipient countries. Australian Economic Papers 60: 189–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnangnon, Sèna Kimm. 2022. Aid for Trade and the Real Exchange Rate. International Trade Journal 36: 264–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, Gene M., and Elhanan Helpman. 2015. Globalization and growth. American Economic Review 105: 100–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajilee, Massomeh, Donna Y. Stringer, and Linda A. Hayes. 2021. On the link between the shadow economy and stock market development: An asymmetry analysis. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance 80: 303–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallaert, Jean-Jacques, and Laura Munro. 2009. Binding Constraints to Trade Expansion: Aid for Trade Objectives and Diagnostics Tools. OECD Trade Policy Papers, No. 94. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Hallaert, Jean-Jacques. 2010. Increasing the Impact of Trade Expansion on Growth: Lessons from Trade Reforms for the Design of Aid for Trade. OECD Trade Policy Papers, No. 100. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, Dominik, Miguel R. Guevara, Cristian Jara-Figueroa, Manuel Aristarán, and César A. Hidalgo. 2017. Linking economic complexity, institutions and income inequality. World Development 93: 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausmann, Ricardo, César A. Hidalgo, Sebastián Bustos, Michele Coscia, and Alexander Simoes. 2014. The Atlas of Economic Complexity: Mapping Paths to Prosperity. Cambridge: Mit Press. [Google Scholar]

- Helble, Matthias, Catherine L. Mann, and John S. Wilson. 2012. Aid-for-trade facilitation. Review of World Economics 148: 357–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, César A., and Ricardo Hausmann. 2009. The building blocks of economic complexity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106: 10570–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoekman, Bernard, and Alessandro Nicita. 2010. Assessing the Doha round: Market access, transactions costs and aid for trade facilitation. Journal of International Trade & Economic Development 19: 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Hoekman, Bernard, and Alessandro Nicita. 2011. Trade policy, trade costs, and developing country trade. World Development 39: 2069–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Yuanhong, Min Jiang, Sheng Sun, and Yixin Dai. 2022. Does Trade Facilitation Promote Export Technological Sophistication? Evidence From the European Transition Countries. SAGE Open 12: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hühne, Philipp, Birgit Meyer, and Peter Nunnenkamp. 2014. Who Benefits from Aid for Trade? Comparing the Effects on Recipient versus Donor Exports. Journal of Development Studies 50: 1275–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishak, Phoebe W., and Mohammad Reza Farzanegan. 2020. The impact of declining oil rents on tax revenues: Does the shadow economy matter? Energy Economics 92: 104925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, Daniel, Aart Kraay, and Massimo Mastruzzi. 2010. The Worldwide Governance Indicators Methodology and Analytical Issues. World Bank Policy Research N° 5430 (WPS5430). Washington, DC: The World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Kelmanson, Mr Ben, Koralai Kirabaeva, Leandro Medina, MissBorislava Mircheva, and Jason Weiss. 2019. Explaining the Shadow Economy in Europe: Size, Causes and Policy Options. IMF Working Paper No. 2019/278. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Yu Ri. 2019. Does aid for trade diversify the export structure of recipient countries? The World Economy 42: 2684–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsadam, Andreas, Gudrun Østby, Siri Aas Rustad, Andreas Forø Tollefsen, and Henrik Urdal. 2018. Development aid and infant mortality. Micro-level evidence from Nigeria. World Development 105: 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loayza, Norman V. 2016. Informality in the process of development and growth. The Word Economy 39: 1856–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ly-My, Dung, Hyun-Hoon Lee, and Donghyun Park. 2021. Does aid for trade promote import diversification? The World Economy 44: 1740–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, Hassan, and Friedrich Schneider. 2016. Size and Development of the Shadow Economies of 157 Worldwide Countries: Updated and New Measures from 1999 to 2013. Journal of Global Economics 4: 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Mazhar, Ummad, and Juvaria Jafri. 2017. Can the shadow economy undermine the effect of political stability on inflation? empirical evidence. Journal of Applied Economics 20: 395–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, Leandro, and Mr Friedrich Schneider. 2018. Shadow Economies Around the World: What Did We Learn Over the Last 20 Years? IMF Working Paper, WP/18/17. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund (IMF). [Google Scholar]

- Melitz, Marc J. 2003. The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica 71: 1695–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, Chris R. 1996. On Natural and Policy-induced Sources of Protection and Trade Regime Bias. Review of World Economics 132: 740–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Terry, Anthony B. Kim, James M. Roberts, and Tyrrell Patrick. 2021. 2021 Index of Economic Freedom, Institute for Economic Freedom, The Heritage Foundation, Washington, DC. Available online: https://www.heritage.org/index/pdf/2021/book/index_2021.pdf (accessed on 17 October 2022).

- Mishra, Saurabh, Ishani Tewari, and Siavash Toosi. 2020. Economic complexity and the globalization of services. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 53: 267–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, Subhadip, and Rupa Chanda. 2021. Tariff liberalization and firm-level markups in Indian manufacturing. Economic Modelling 103: 105594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Canh Phuc. 2022. Does economic complexity matter for the shadow economy? Economic Analysis and Policy 73: 210–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickell, Stephen. 1981. Biases in Dynamic Models with Fixed Effects. Econometrica 49: 1417–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novy, Dennis. 2013. Gravity Redux: Measuring International Trade Costs with Panel Data. Economic Inquiry 51: 101–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD/WTO. 2007. Aid for Trade at a Glance 2007: 1st Global Review. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- OECD/WTO. 2015. Aid for Trade at a Glance 2015: Reducing Trade Costs for Inclusive, Sustainable Growth. Geneva: WTO. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD/WTO. 2019. Aid for Trade at a Glance 2019: Economic Diversification and Empowerment. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, Ngoc Thien Anh, and Nicholas Sim. 2020. Shipping cost and development of the landlocked developing countries: Panel evidence from the common correlated effects approach. The World Economy 43: 892–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porteous, Obie. 2020. Trade and agricultural technology adoption: Evidence from Africa. Journal of Development Economics 144: 102440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portugal-Perez, Alberto, and John S. Wilson. 2012. Export Performance and Trade Facilitation Reform: Hard and Soft Infrastructure. World Development 40: 1295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roodman, David M. 2009. A note on the theme of too many instruments. Oxford Bulletin of Economic and Statistics 71: 135–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadi, Mohamed. 2020. Remittance Inflows and Export Complexity: New Evidence from Developing and Emerging Countries. The Journal of Development Studies 56: 2266–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, Shrabani, Hamid Beladi, and Saibal Kar. 2021. Corruption control, shadow economy and income inequality: Evidence from Asia. Economic Systems 45: 100774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, Friedrich, and Dominik H. Enste. 2000. Shadow economies: Size, causes, and consequences. Journal of Economic Literature 38: 77–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, Friedrich, Andreas Buehn, and Claudio E. Montenegro. 2010. Shadow Economies All Over the World: New Estimates for 162 Countries from 1999 to 2007. Policy Research Working Paper 5356. Washington, DC: The World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, Friedrich. 2005. Shadow economies around the world: What do we really know? European Journal of Political Economy 21: 598–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, Friedrich. 2010. The influence of public institutions on the shadow economy: An empirical investigation for OECD countries. Review of Law and Economics 6: 441–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, Friedrich, and C. Williams. 2013. The Shadow Economy. London: The Institute of Economic Affairs, Edward Elgar. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, Tarlok. 2010. Does International Trade Cause Economic Growth? A Survey. The World Economy 33: 1517–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, Allan. 2014. Additive versus multiplicative trade costs and the gains from trade liberalizations. Canadian Journal of Economics 47: 1032–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, Bedassa, Bichaka Fayissa, and Elias Shukralla. 2021. Infrastructure, Trade Costs, and Aid for Trade: The Imperatives for African Economies. Journal of African Development 22: 38–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, Bedassa, Elias Shukralla, and Bichaka Fayissa. 2019. Institutional quality and the effectiveness of aid for trade. Applied Economics 51: 4233–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanzi, Vito. 1999. Uses and Abuses of Estimates of the Underground Economy. Economic Journal 109: 338–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNCTAD. 2006. The Least Developed Countries Report 2006: Developing Productive Capacities. New York and Geneva: United Nations Publication, Sales No. E.06.II.D.9. [Google Scholar]

- UNCTAD. 2020. The Least Developed Countries Report 2020: Productive Capacities for the New Decade. New York and Geneva: United Nations publication, Sales No. E.21.II.D.2. [Google Scholar]

- Vijil, Mariana, and Laurent Wagner. 2012. Does Aid for Trade Enhance Export Performance? Investigating on the Infrastructure Channel. World Economy 35: 838–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weldemicael, Ermias. 2014. Technology, Trade Costs and Export Sophistication. The World Economy 37: 14–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, John S., Catherine L. Mann, and Tsunehiro Otsuki. 2005. Assessing the benefits of trade facilitation: A global perspective. World Economy 28: 841–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Trade Organization (WTO). 2005. Ministerial Declaration on Doha Work Programme. Paper presented at the Sixth Session of Trade Ministers Conference (document, WT/MIN(05)/DEC), Hong Kong, China, December 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Yanase, Akihiko, and Masafumi Tsubuku. 2022. Trade costs and free trade agreements: Implications for tariff complementarity and welfare. International Review of Economics & Finance 78: 23–37. [Google Scholar]

- Younas, Zahid Irshad, Atiqa Qureshi, and Mamdouh Abdulaziz Saleh Al-Faryan. 2022. Financial inclusion, the shadow economy and economic growth in developing economies. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 62: 613–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | SHADOW | SHADOW | SHADOW | SHADOW |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| SHADOWt−1 | 0.720 *** | 0.811 *** | 0.650 *** | 0.752 *** |

| (0.0284) | (0.0294) | (0.0320) | (0.0246) | |

| Log(AfTTOT) | 0.181 | −0.150 | −0.668 ** | 2.299 *** |

| (0.245) | (0.144) | (0.317) | (0.744) | |

| ECONC | −2.706 *** | 9.776 ** | ||

| (0.720) | (3.937) | |||

| PCI | −0.180 *** | 1.769 *** | ||

| (0.0588) | (0.521) | |||

| [Log(AfTTOT)]*ECONC | −0.588 *** | |||

| (0.205) | ||||

| [Log(AfTTOT)]*PCI | −0.0961 *** | |||

| (0.0274) | ||||

| Log(NonAfT) | 0.678 | −0.203 | 0.997 ** | 0.655 |

| (0.471) | (0.239) | (0.409) | (0.410) | |

| FINDEV | −0.0221 | −0.0528 *** | ||

| (0.0150) | (0.0130) | |||

| INST | 0.178 | 0.425 | ||

| (0.430) | (0.497) | |||

| Log(GDPC) | −1.495 *** | −1.035 *** | −1.794 *** | −0.940 *** |

| (0.282) | (0.276) | (0.340) | (0.227) | |

| TAXBURD | 0.0588 *** | 0.107 *** | 0.0995 *** | 0.0714 *** |

| (0.0197) | (0.0243) | (0.0203) | (0.0251) | |

| Observations–Countries | 224–83 | 270–101 | 224–83 | 270–101 |

| Number of Instruments | 54 | 52 | 58 | 49 |

| AR1 (p-Value) | 0.0242 | 0.0335 | 0.0271 | 0.0385 |

| AR2 (p-Value) | 0.4779 | 0.6738 | 0.5750 | 0.5427 |

| OID (p-Value) | 0.5632 | 0.2481 | 0.3818 | 0.6720 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gnangnon, S.K. Do Aid for Trade Flows Help Reduce the Shadow Economy in Recipient Countries? Economies 2022, 10, 310. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies10120310

Gnangnon SK. Do Aid for Trade Flows Help Reduce the Shadow Economy in Recipient Countries? Economies. 2022; 10(12):310. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies10120310

Chicago/Turabian StyleGnangnon, Sèna Kimm. 2022. "Do Aid for Trade Flows Help Reduce the Shadow Economy in Recipient Countries?" Economies 10, no. 12: 310. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies10120310

APA StyleGnangnon, S. K. (2022). Do Aid for Trade Flows Help Reduce the Shadow Economy in Recipient Countries? Economies, 10(12), 310. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies10120310