Abstract

The inseparability of the production and consumption of services without quality control makes it difficult to fully meet the diverse needs of customers. Despite a company’s continuous efforts to satisfy customers with perceived quality aimed at service success, if the customers’ expectations are not met, the customers will not be satisfied. This study empirically analyzed the effects of customer tolerance and relationship commitment as psychological variables on the relationship between customer participation and repurchase intentions. According to the results of the analysis, relationship benefits, which are a motivation factor for customer participation, had significant effects on customer participation. In addition, customer participation showed significant effects on customer tolerance and relationship commitment. Furthermore, both customer participation and tolerance had significant effects on repurchase intentions; however, relationship commitment was found to have no significant effect on repurchase intentions. The results of this study indicate that customer tolerance formed through customer participation behavior improves customers’ satisfaction with perceived service quality thanks to the shared sense of responsibility that makes customers tolerate a failure of the final service after the service encounter process, thereby increasing repurchase intentions, which prevents the consumptive expenses invested into to recovering services after the company’s service failure. As such, the results of this study provide meaningful implications for sustainable management.

1. Introduction

External environmental factors such as the corona virus pandemic have fueled the acceleration of non-face-to-face consumption. Despite such a market environment, many consumers have responded only to the personalized and customized marketing that they are already accustomed to. This has led to an increased burden for companies trying to win the hearts of new customers. In this respect, the service industry—where production and consumption occur simultaneously—has struggled to satisfy the needs and expectations of individual consumers and encourage them to become repeat customers. At the end of the 20th century, the service-dominant logic emerged, which states that services are a broad concept that includes products and that all economic activities are a part of the service economy (Vargo and Lusch 2004; Greer et al. 2016). This logic has led to the notion that the service industry no longer plays an ancillary role of supporting the creation of the value of products, and that marketing is integrated through services (Lee and Lee 2014). Therefore, companies invest heavily to induce service success; however, service failure can never be avoided entirely (Kaltcheva et al. 2013; Hart et al. 1990). The inseparability of production and consumption is an essential characteristic of the service industry, one that makes controlling quality in advance of consumption difficult (Hess et al. 2003). The inseparability of service requires various levels of customer participation in the service production process (Hepp 2006; Bitner et al. 1997; Hubbert 1995), and negative emotions or behavior against service failure are reinforced or alleviated depending on the degree of customer participation behavior (Kaltcheva et al. 2013; Bitner et al. 1997; Hubbert 1995; Bowen and Jones 1986; Larsson and Bowen 1989; Bendapudi and Leone 2003). Previous studies on recovery from service failure indicated that, although it was clear that service failure causes negative emotions in consumers, many customers hesitated to switch to other service companies even after experiencing service failure (Kim 2012).

Is there some way to prevent service failures in advance; some way to get customers to tolerate unmet expectations in the process of service development at a time in which service production and consumption occur simultaneously? A previous study (Yagil and Luria 2016) indicated that, in interactions between service providers and customers, forgiving consumers made conscious decisions to pay attention to the positive aspects of the interaction rather than focusing on the negative aspects of the experience, and showed a positive relationship orientation towards trying to do the best for each other’s experiences regardless of the service performance (Yagil and Luria 2016). In addition, the relevant study indicated that forgiving customers showed signs of taking some responsibility for the consequences of the failure or defending against such failures in the future (Yagil and Luria 2016). In addition, According to a study by Lawler (2001), when a customer is faced with a service exchange, the customer has the desire to control the service outcome by himself, and strives for good results together with the service provider. In other words, the perceived shared responsibility of the customer increases. This means that, when customers participate in the service exchange, their consciousness and will to control the service result by themselves appear, and they strive for the desired result together with service providers. That is, customers’ perception of their own control over the service results is enhanced so that the customers’ belief in a shared sense of responsibility is also enhanced (Berry et al. 1988; Seo et al. 2010). As such, service performance appears depending on the success or failure of the service in the interactive relationship between service production and consumption. Therefore, studies on customer emotions that can prevent service failure in advance can be very important (Kim et al. 2022). The appraisal theory of emotion argues that people’s emotional responses can appear differently depending on how they evaluate and interpret incoming information about events (Lazarus 1991). That is, even if consumers experience similar service dissatisfaction, the magnitude and direction of their unfavorable emotions such as regret or switching intentions may vary depending on the individuals’ disposition and the level of situational context (Kim 2012; Meichenbaum and Deffenbacher 1988). Therefore, this study will examine the effects of relationship commitment and customer tolerance on the relationship between customer participation and repurchase intentions, with a view to identifying the effects of the psychological mechanism on the process of interaction between customers and service providers.

In this research, customer forgiveness, a psychological variable similar to customer tolerance, was studied as a variable in the dimension of service recovery related to service failure after service results in previous studies. However, in some studies, it was defined as a multidimensional concept including customer tolerance (Yagil and Luria 2016; Lv et al. 2021). The variable customer tolerance in this study is a psychological variable in the service process and is different from customer forgiveness; however, it is difficult to argue that customer tolerance and customer forgiveness are completely unrelated in that, through the service process, customers’ satisfaction or dissatisfaction with perceived quality resulting from met expectations and discrepancies from expectations leads to the final success or failure of service. Therefore, this study aims to examine the relationship between the relational benefit, which is a motivating factor for customer participation, and the influence of customer participation behavior. Also, in the context of interaction according to customer participation behavior, this study aims to examine the relationship between the effect of customer participation on customer tolerance and relationship commitment, and the effect of customer tolerance and relationship commitment on repurchase intention.

The investigation of the influencing relationships among customer participation behavior, customer tolerance, and relationship commitment is thought to provide important implications that will enable companies to realize sustainable management by minimizing companies’ need to recover service, because the interaction between service providers and customers through customer participation behavior plays a role in offsetting the discrepancies in service results, thereby reducing eventual service failure.

2. Theoretical Background and Study Hypotheses

2.1. Relationship Benefits and Customer Participation

Gwinner et al. (1998) defined relationship benefits from the customer’s viewpoint as ‘benefits obtained by customers through their long-term perspective beyond the core service performance’. In addition, they said that, through the formation of relationships with companies used by customers, customers can reduce various purchasing risks, enjoy benefits following socialization, and expect benefits following personalization. Berry et al. (1988) stated that the relationship benefits of both companies and customers are essential for the continuation of the relationship between companies and customers because, when both obtain benefits, not only can the relationship be maintained but, also, the quality of the relationship can be improved. In addition, Gwinner et al. (1998) defined relationship benefits as four different benefits: economic, social, psychological, and individuation benefits. They defined social benefits as intimacy, consideration, friendship, personal recognition, and social support between customers and companies, and psychological benefits as feelings such as comfort and safety experienced by customers as they form relationships with service providers. They defined economic benefits as benefits such as price incentives presenting discounts and low prices and the reduction in information search time at the decision-making stage, as well customized benefits such as preferential treatment, special services, and special treatment, etc. (Gwinner et al. 1998). In this study, among the various sub-dimensional factors of relationship benefits mentioned above, using the sub-variables of relationship benefits excluding customized benefits, the effects of relationship benefits on customer participation will be examined. The reason for this is that this study did not separately control the strength and duration of the relationship between service customers and service providers in investigating the influencing relationship between customer participation and relationship benefits in the service encounter situations of beauty salon users. Therefore, this study will verify the significant effects of social benefits, psychological benefits, and economic benefits, which are three subdimensions of relationship benefits, on customer participation excluding customized benefits defined as preferential treatment and special service benefits.

Solomon et al. (1985), who are researchers of the concept of customer participation, defined customer participation as the degree of effort and interest exerted by consumers mentally and physically in cases where consumer participation is indispensable in the process of production and delivery of services (Han et al. 2004). In addition, in a study conducted by Cermak et al. (1994), customer participation was approached with a concept of involvement according to how much time and effort the person invested in the service delivery process, and, in a study conducted by Kellogg et al. (1997), customer participation was studied from the viewpoint of service quality cost to create the excellent service results expected by the consumer himself/herself. In a study conducted by Rodie and Kleine (2000), consumer participation in the process of service delivery and production was multidimensionally approached instead of through a single dimension and presented as physical, emotional, and mental information inputs (Choi et al. 2020). In this study, customer participation behavior will be defined and studied as inputs of essential and active efforts for expected service results as a form of essential participation indispensable for service production and consumption. Relationship benefits, which are dealt with as a core predisposing factor of customer perspectives in relationship marketing studies, can be said to be an important driver for customers to form and maintain relationships. That is, the reason why service providers and the customer form and maintain a relationship should be that such a relationship is judged to be beneficial to both and, if benefits are not created between them, such a relationship could hardly be maintained (Seo et al. 2010). Therefore, relationship benefits further improve customer participation behaviors in the service delivery and production process, and, ultimately, the improved customer participation behaviors facilitate interaction with service providers in encounter situations (Seo et al. 2010). A study conducted by Dwyer et al. (1987) in the same vein indicated that relationship benefits make customers more actively participate in their interactions with service providers in service encounter situations and that these behaviors become important causes of improvement of the quality of mutual relationships. Therefore, this study presents the following hypotheses to identify the significant effects of social benefits, psychological benefits, and economic benefits, which are sub-factors of relationship benefits, as predisposing factors of customer participation.

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Social benefits will have a positive (+) effect on customer participation behavior.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Psychological benefits will have a positive (+) effect on customer participation behavior.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Economic benefits will have a positive (+) effect on customer participation behavior.

2.2. Customer Participation and Customer Tolerance

Keh and Teo (2001) defined customer tolerance as a ‘customer’s will to tolerate or endure situations where the service has not been delivered as expected at the service encounter’, and stated that customer tolerance of service failure is a core variable that can enhance the performance of a company. The biggest factor of service switching in the service industry can be said to be the failure of core services (Keaveney 1995). The simultaneity of production and consumption, which is an inseparable characteristic of services, should be viewed as making perfectly satisfying the diversified and advanced service needs of customers. In the same vein, due to the service characteristics resulting from service inseparability, services cannot always be successful at the time when the services are provided, and it has been seen that service failure can be induced at any time by elements of companies that cannot be controlled (Bitner et al. 1990; Smith et al. 1999; Tax et al. 1998). Therefore, customer forgiveness has been studied as an important psychological variable in numerous studies on service recovery after service failure. As a result, rather than a study of psychological variables of approaches to service recovery in the consequential aspect after a service failure, this study is intended to empirically analyze customer tolerance as a psychological variable in the process of customer participation through the process of interaction between service providers and service customers (Kim et al. 2022). The reason for setting the variable in this study as a variable of consumer tolerance, not customer forgiveness, is that customer forgiveness is a variable in the recovery perspective (Kim 2012) for the expression of failure of customers who have experienced service failure. In addition, in this study, it is because customer tolerance was placed in the role of psychological variables as a preventive point of view for potential service failures that do not live up to expectations in the service process. In addition, the reason why we focus on customer tolerance rather than customer forgiveness in this study is that recovery from service failure can only give companies an opportunity to recover service when the customer who has experienced service failure does not remain silent and expresses service failure (Yen et al. 2004). For consumers who remain silent even after experiencing service failure, the company does not have an opportunity to recover service, resulting in a loss that can create service conversion customers. In a study by Koc et al. (2017), which examined the effect of customer participation on service failure perception, it was also found that customers who participated in service contact showed a softer and milder response to failure.

A study conducted by Lv et al. (2021) indicated that customer tolerance means positive communication with service providers and refraining from negative responses beyond passive acceptance or forgiveness of service failures. Therefore, interaction with employees through customer participation behaviors led to employees’ efforts for customers resulting in the formation of positive emotions of customers, which led to outcome variables such as customer satisfaction, service quality, etc. (Bendapudi and Leone 2003; Han et al. 2004; Yen et al. 2004; Koc et al. 2017; Park 2007; Ahn and Seo 2009). Therefore, it is understood that customer participation behaviors play a major role in the formation of positive emotions of customers by causing sympathetic interaction (Seo et al. 2010). Therefore, based on previous studies indicating that the interaction between the service provider and the customer through participation behavior is recognized as mutual effort for the successful exchange of services, and that the service customer perceives the shared sense of responsibility for service success which causes customer tolerance, this study established the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Customer participation will have a positive (+) effect on customer tolerance.

2.3. Customer Participation and Relationship Commitment

Allen and Meyer (1990) developed and evaluated a scale of constructs in which relationship commitment is divided into emotional commitment, continuous commitment, and normative commitment (Seo et al. 2010; Allen and Meyer 1990). To explain the foregoing in detail, first, emotional commitment means a psychological attachment based on a preference for the organization and refers to a strong and positive attitude toward the organization interaction (Seo et al. 2010; Mowday et al. 1982). In this regard, Allen and Meyer (1990) emphasized the importance of emotional commitment, arguing that sensible orientation toward the organization should be understood as emotional commitment and emotional commitment should be viewed as an emotional bond to the relationship (Seo et al. 2010; Allen and Meyer 1990). Second, continuous commitment refers to cases where a person has a continuous emotional attachment to a group due to his/her economic and social status (Allen and Meyer 1990; Gruen et al. 2000). That is, continuous commitment is a psychological reinforcing action in customers to justify their participation by emphasizing the strengths of the organization or group and explains the tendency of members of an organization or group to remain in the organization considering the conversion cost. In addition, the continuous commitment in the behavioral dimension was explained as a feeling of restraint due to the sunk cost invested (Seo et al. 2010). Third, normative commitment can be explained as psychological attachment based on the obligation to continue the relationship (Hackett et al. 1994).

Among the various constituent dimensions of relationship commitment as written above, this study intends to use the constructs of emotional commitment, focusing on the emotional dimension, as constructs in this study. The reason for this is that the purpose of this study is to check the effect relationship of customer participation behavior on relationship commitment through the interaction of the service contact situation between service providers and service customers, and then to examine the significant effect of relationship commitment on repurchase intention. Therefore, we conducted this study by limiting it to the emotional dimension most closely related to the psychological variables of this study. Previous studies demonstrated that customer participation behaviors significantly affect relationship commitment (Seo et al. 2010; Ahn and Seo 2009; Ahn et al. 2013; Ahn 2014). In the study conducted by Seo et al. (2010), the study conducted by Gilliland and Bello (2002) was cited as an example to argue that customer relationship-specific investments have positive effects on customer commitment, and relationship commitment occurs according to the conversion cost following customers’ effort for relationships as a content of such relationship-specific investments. That is, since customers’ various efforts in the process of interaction, such as customer participation behaviors, can be understood as a sort of investment concept, the more the investments as such are made, the further the customer commitment to maintain the relationship is enhanced. Also, in a structural study of customer participation and relationship commitment, customer participation was found to have a significantly positive (+) effect on emotional commitment, and a study on the role of long-term relationships of customer participation in the interaction process derived results which indicate that customer participation has significant positive effects on customer commitment (Ahn et al. 2013; Ahn and Oh 2020). Therefore, the following hypothesis is presented based on previous studies.

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Customer participation will have a positive (+) effect on relationship commitment.

2.4. Customer Participation and Repurchase Intention

Repurchase intentions in service situations were defined as the possibility for customers to repeatedly use the service provider in the future (Kim and Oh 2002). In addition, Engel and Blackwell (1982) stated that intention, as a general concept, includes individuals’ predicted or planned future behaviors, and is the probability for beliefs and attitudes to be converted into behaviors (Kim et al. 2022; Engel and Blackwell 1982). Furthermore, repurchase intention is recognized as a very important concept for marketers because it can be used as a substitute for actual purchasing behaviors and is directly related to future purchases (Maxham 2001). Cermak et al. (1994) mentioned that customer involvement is a leading variable affecting repurchase intention, argued that customer participation behavior will affect repurchase intentions by pointing out that customer participation behaviors are a construct very similar to customer involvement, and proved that there is a strong causal relationship between customer participation behaviors and customers’ repurchase intentions through empirical studies (Kim et al. 2022; Cermak et al. 1994). Therefore, based on the previous studies, this study presented the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

Customer participation will have a positive (+) effect on repurchase intention.

2.5. Customer Tolerance and Repurchase Intention

Behaviors resulting from customer tolerance include not only not conducting any action of revenge toward the other party, but also behaving favorably with good feelings toward the other party (Enright et al. 1992; McCullough et al. 1997). There have been few previous studies conducted thus far that investigated the direct effect of customer tolerance on repurchase intentions. Therefore, this study is intended to examine the relationship between customer tolerance and repurchase intentions by identifying the relationship between perceived quality and behavioral intentions through the case of previous studies on repurchase intentions according to service quality perception. According to the service theory developed by the Nordic school of service marketing (NSSM) in Europe, service quality is directly related to the behavioral intentions of customers (Gronroos 1990). Researchers suggest that perceived quality is similar to attitudes. Gotlieb et al. (1994) used the theoretical concept developed by Lazarus (1991) and Bagozzi (1992) to present the relationships among perceived quality, satisfaction, and behavior intentions (Lazarus 1991; Gotlieb et al. 1994; Bagozzi 1992; Yi and Gong 2005). Also, Lazarus (1991) suggested a general framework of evaluation → emotional response → response, and Bagozzi (1992) applied this framework to explain attitudes and behavior intentions (Lazarus 1991; Bagozzi 1992). In addition, Bagozzi (1992) proposed the concept of performance and need units, said that individuals participate in activities such as service purchases due to their desire to achieve a certain performance, and suggested that, when the evaluation of activities in such situations is perceived as indicating that the planned performance was achieved, then “need-performance fulfillment” exists and emotional responses such as satisfaction follow in this case (Bagozzi 1992; Yi and Gong 2005). He explained that, therefore, the emotional responses as such induce favorable behavior intentions such as repurchase intentions to improve and maintain satisfaction levels (Yi and Gong 2005). Consistently with the rationale as such, many researchers indicate a relationship between service quality perception and repurchase intentions, and a positive (+) relationship between service quality perception and customer satisfaction. In addition, Zeithaml et al. (2002) argued that a positive perception of service quality generates favorable word-of-mouth toward service companies and influences customer behavior intentions in the form of increased purchase volumes (Zeithaml et al. 2002). In addition, in a recent study examining the effects of customer tolerance on the relationship between customer participation and repurchase intentions, it was identified that customer tolerance had a significant positive effect on repurchase intentions (Kim et al. 2022). Based on the background of this study, the hypothesis as follows is presented because it was judged that customer tolerance, induced by the formation of a shared sense of responsibility for service success through interaction between service providers and customers in service encounter situations following customer participation, has significant effects on repurchase intentions.

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

Customer tolerance will have a positive (+) effect on repurchase intentions.

2.6. Relationship Commitment and Repurchase Intention

In a study conducted by Kim and Cho (2007), which is a previous study of repurchase intentions through relationship commitment, emotional commitment was shown to have a significant effect on repurchase intentions, and, in a study conducted by Hong et al. (2008), relationship commitment was shown to have a significant effect on repurchase intentions. In addition, in a study that examined the effect of relationship commitment on customer loyalty, which is a relational outcome variable of relationship commitment, relationship commitment was found to have significant effects on customer loyalty (Seo et al. 2010). This is consistent with the content of a study conducted by Palmatier et al. (2006) on relationship marketing, which was conducted over many years, arguing that the role of relationship commitment was identified as a relational parameter to explain loyalty and continued use intentions. Therefore, based on the contents of the mentioned studies, the following hypothesis is presented.

Hypothesis 8 (H8).

Relationship commitment will have a positive (+) effect on repurchase intentions.

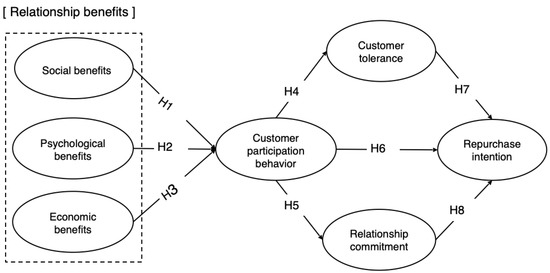

The study model established in this study based on the above study hypotheses is presented as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Study model.

3. Study Method

3.1. Collection of Samples and Selection of Service Types

Samples were collected through a questionnaire survey to verify the hypotheses of this study, and the questionnaire items for the questionnaire survey were developed based on previous studies on related variables. Before conducting the main questionnaire survey using the developed items, 50 copies of the preliminary questionnaire were distributed in June 2022 to conduct a pilot test. Afterwards, for this survey, a total of 430 online questionnaires were distributed throughout Korea for one month from 1 July 2022, and 402 copies were collected. Of the 402 collected copies, 401 valid questionnaires were used for analysis, excluding one insincere copy. As for the demographic characteristics of the sample, the 50–59 age group accounted for the largest proportion, and the male–female ratio was slightly higher for females (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of samples (n = 401).

Beauty salons in the service industry were selected as a type of service to be surveyed. The reason for this is that, based on previous studies, this study attempted to select a service type in which service results can vary with the degree to which the services pursued by consumers are accurately identified to satisfy consumers, rather than a service type in which successful services are produced only depending on the professional competence of the service provider (Bitner et al. 1997; Kelley et al. 1990; Mills and Morris 1986; Hsieh and Chang 2004). That is, beauty salons were selected because, in the case of beauty salons, customers’ provision of information and customer expectations for the perceived quality of service results can affect the evaluation of service results, and service customers stay in the physical service space for relatively long periods of time so that customer participation behaviors can be elicited through sufficient interaction between the service provider and service customers (Kim et al. 2022).

3.2. Operational Definition of Variables

In this study, a total of seven variables were used, and the measurement items for measuring individual variables were composed into Likert 5-point scales based on previous studies. Relationship benefits, a leading variable in this study, were defined as the benefits received by customers in forming a relationship with a service provider. To measure this concept, the measurement items of Gwinner et al. (1998) and Kim and Seo (2006) were used. Social benefits appear as a result of the formation of a relationship and refer to benefits attained through friendly relationships between customers and service providers in the process of delivery of core services. Psychological benefits refer to feeling psychologically comfortable by using service providers, and economic benefits were defined as feeling monetary cost savings and time cost savings. Customer participation behaviors were defined as the essential and active effort and input of customers in the service delivery and production processes and were measured with a total of nine items centered on three dimensions, communicability, associability, and adaptability, used in studies conducted by Rodie and Kleine (2000), Yoon et al. (2005), and Seo et al. (2010). Customer tolerance was defined as customers’ will to tolerate or endure situations where services were not delivered as expected at the service encounter based on studies conducted by Keh and Teo (2001) and Kim and Cho (2011), and three items were revised to fit this study and used in measurement. Customer tolerance, in this study, is a tolerant attitude based on interaction with service providers, and supposes that customers are given a shared sense of responsibility by accepting additional proposals from service providers. Relationship commitment was defined as the efforts of the parties in a relationship to maintain their relationship with each other and was measured with five items: attachment, friendliness, the degree of closeness of the relationship, the personal meaning of the relationship, and regarding the other party like oneself (Seo et al. 2010; Allen and Meyer 1990). In addition, repurchase intention was measured using the scale used by Zeithaml et al. (1996), Headley and Miller (1993), and Han et al. (2004), with revisions to fit this study such as whether or not the beauty salon was reused.

Table 2, below, is a table of the operational definitions of variables that summarized their contents.

Table 2.

Operational definitions of variables.

4. Analysis Results

4.1. Verification of Reliability and Validity

To verify the reliability and validity of the constructs and measurement tools in this study, the reliability and validity were analyzed using SPSS 22.0 and AMOS 22.0 statistical programs. As a result of verification of the internal consistency of the constructs (see Table 3), the reliability was secured, as the Cronbach’s α coefficients were 0.714 to 0.880, which were at least 0.7. The validity was verified with principal component analysis (PCA) and orthogonal rotation (varimax) as factor analyses, and, according to the results, all the factor loadings were at least 0.4 and seven factors accounted for 70.764% of the total explanatory variance, meaning that the validity of the constructs was secured. Thereafter, confirmatory factor analyses of latent variables were conducted and, according to the results, the fitness indexes of the measurement models were shown to be x2 = 713.500 (df = 254, p = 0.000), CFI = 0.929, GFI = 0.868, NFI = 0.894, and RMR = 0.054, RMSEA = 0.067, which were above or close to the acceptance level; therefore, the fitness was judged to be good in general. In addition, the conceptual reliability (C.R.) values of the measurement variables constituting the constructs were all at least 0.7, and the average variance extracted (AVE) values were all at least 0.5; therefore, construct validity and convergent validity were secured.

Table 3.

Confirmatory factor analysis.

In addition, the smallest value among the average variance extracted (AVE) values for individual constructs (economic benefits = 0.513) was shown to be smaller than the largest value (ρ(psychological benefits and customer participation)2 = 0.446) of all square values (ρ2) of the correlation coefficients between concepts, meaning that the discriminant validity of all constructs was secured. See Table 4.

Table 4.

Matrix of correlations between constructs.

4.2. Study Model’s Goodness of Fit

To verify the hypotheses of this study, the structural model was analyzed using AMOS 22.0. The goodness of fit indexes of the structural model were (x2 = 776.058, df = 263, p = 0.000), CFI = 0.920, GFI = 0.852, NFI = 0.885, and RMR = 0.061, which were identified to be acceptable. In addition, the default model (x2 = 356.867 df = 111) that does not include customer tolerance and relationship commitment and the model that includes customer tolerance and relationship commitment were compared and analyzed to compare the chi-squares and degrees of freedom of the two models, and, as a result, it was confirmed that the model including customer tolerance and relationship commitment had better explanatory power [x2 difference = 419.191(df = 152) > 124.34(df = 10)].

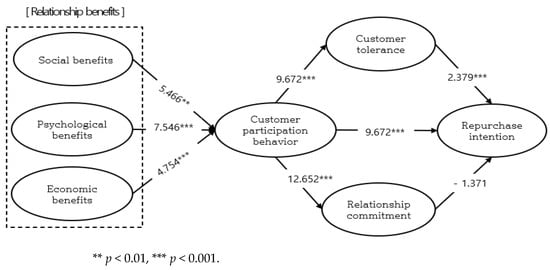

4.3. Verification of Study Hypotheses

To verify the study hypotheses, the hypotheses were verified through path analysis, and the results are as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Results of verification of hypotheses.

Therefore, the results of analysis of the structural model in this study are as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Results of verification of the study model.

5. Discussion

The purpose of this study is to empirically analyze the relationship between customer tolerance and relationship commitment as a mediating role of psychological variables between customer participation and repurchase intention. The study results demonstrated in this study can be summarized as follows.

First, it was identified that social benefits, psychological benefits, and economic benefits, which are leading variables of customer participation behaviors, directly affect customer participation behavior. This is consistent with a previous study conducted by Dwyer et al. (1987), which indicates that relationship benefits make customers participate more actively in the process of interaction with service providers in service encounter situations and such behavior becomes an important factor to improve the quality of the relationship. Notably, psychological benefits were found to have statistically significantly greater effects on customer participation than social benefits and economic benefits. The results, as such, can be viewed to be consistent with the result of this study, indicating that customer satisfaction is affected more by psychological elements than cognitive elements (Kim et al. 2022).

Second, customer participation had a positive (+) effect on customer tolerance. Service failure means that service provision is discrepant from customer expectations (He and Harris 2014; Newton et al. 2018). Customer participation, which is an interaction between service providers and customers in the service encounter before the customer perceives the quality of the service result as failure, causes customers to experience greater satisfaction due to empirical elements than due to rational elements that require human judgment (Gassin 1995). Therefore, customer participation instills a tolerant psychology, as evidenced by the study results indicating that attitudes and behavior appear due to psychological elements rather than cognitive elements (Kim 2014).

Third, Customer participation had a positive (+) effect on relationship commitment; however, there was no mediating effect of relationship commitment on the relationship between customer participation and repurchase intention.

Fourth, customer tolerance showed a positive (+) effect on repurchase intentions. This is the core influencing relationship that this study was intended to elucidate, and customer participation behavior through interaction between service providers and customers in service encounters lead to mutual sympathy about and bearing of the responsibilities for service results, causing customers to show tolerant attitudes toward service providers and results, through which repurchase intentions increase (Kim et al. 2022).

Fifth, relationship commitment did not have any significant effect on repurchase intentions. This result is consistent with a recent study that elucidated the influencing relationship between customer commitment and repurchase intentions from the viewpoint of relationship quality and is proof that relationship commitment can hardly have a significant effect on repurchase in situations of low frequencies of contact with service providers and short periods of relationships according to the characteristics of individual customers by situation, leading to the recognition of the importance of customer tolerance rather than relationship commitment in terms of the outcomes of repurchase intentions through customer participation (Antwi 2021). That is, the effects of customer participation on repurchase intention are more clearly explained through customer tolerance than relationship commitment.

Therefore, this study intends to present the following implications based on the results of the empirical analysis mentioned above. First, among the theoretical implications, studies on mediator variables through customer participation thus far have derived a influencing relationship between customer participation and outcome variables using service quality, service value, relationship commitment, and emotional empathy as main parameters (Kim et al. 2022). This study can be viewed to have newly presented an academic study agenda termed customer tolerance through customer participation by enhancing the importance of customer participation by empirically investing the effect of the psychological variable customer tolerance following the interaction between service providers and service customers in service encounters through customer participation, which is an inseparable characteristic of the service industry. That is, previous studies on customer tolerance concentrated on customer tolerance as a psychological variable through customers’ citizen behaviors (behaviors outside the role); however, this study studied customer tolerance as a psychological variable in the process of customer participation (behavior within the role), which is essentially carried out instead of behaviors outside the role, thereby widening the breadth of studies on customer tolerance. Second, this study is quite meaningful in that it is not a study of psychological variables in the service recovery process after service result failure, but instead demonstrated significant effects of ‘customer tolerance,’ a major psychological mechanism expressed to defend service failure in the process of interaction between service providers and service customers during the service process. That is, this study presented the direction of marketing strategy planning through customer participation by substantiating previous studies which indicated that consumer behaviors are affected by psychological elements based on experience rather than cognitive elements despite the ever-changing consumer psychology. In addition, this study identified, through empirical study, the reason why companies’ limited resources should be focused on customer tolerance rather than being concentrated on relationship commitment, thereby expanding the potential of related studies hereafter.

As a practical implication, this study identified, through empirical studies, that the performance of service marketing through customer participation in the field of the service industry is still important in today’s market situations where non-contact consumption is becoming commonplace along with changes in the external environment. For example, service providers and marketing managers of small self-employed businesses in the service field, which is a field where the success or failure of service in the service industry is most realistically felt, should develop motivation factors for practically applicable customer participation behaviors to induce customer participation. This will create a shared sense of responsibility through the interaction between the service provider and the customer to make the psychology of the customer tolerant, thereby offsetting the customer’s dissatisfaction with the perceived service quality to derive the outcome of repurchase. In addition, service providers should be provided with specific manuals on customer participation behaviors, and quality mutual relationships should be induced through related training. In conclusion, by reducing unproductive competition for companies’ creation of new customers and intensively investing companies’ limited resources into customer participation that will enable customized interactions between service providers and individual customers, companies can induce customer tolerance for perceived service quality to secure loyal customers through continuous relationships with existing customers along with the favorable function of reducing the time and cost invested in the creation of new customers, and this can be an important cornerstone for the sustainable management of companies.

Despite the meaningful implication of customer tolerance through customer participation, this study has the following limitations. First, the results of the study of one field of beauty service, biased regionally, have limitations in generalization to the entire service industry. Second, in this study, the strength of the relationship between service customers and service providers—the frequency of contact with the service provider and the length of the relationship—was not controlled, which is a limitation of the study, since the strength of the relationship between service customers and service providers should be controlled because it can affect the difference in the interaction effect between existing and new customers. Third, customers’ satisfaction or dissatisfaction when customers’ expectations were met or unmet in the process of interaction between service providers and service customers was not concretely measured with a questionnaire. This implies the premise that customer expectations are always unmet and, in studies hereafter, customers with unmet expectations for perceived service quality should be selected. Fourth, the fact that the period of use of beauty salons according to the special situation where the use of beauty salon services was restricted due to the coronavirus pandemic was not included in the measurement through the questionnaire survey and, thus, can be cited as a limitation. Fifth, in the situation where academic studies on customer tolerance, a core psychological variable in this study, are insufficient, there is a lack of constructs that can clearly reveal the psychological mechanism by which service customers create customer tolerance through customer participation, which is another limitation of this study. In future studies, a scale for customer tolerance that can more clearly reveal the psychological mechanism of customer tolerance by overcoming these limitations should be developed and the effects of exogenous variables should be controlled. In addition, follow-up studies should consider the introduction of various forms of customer participation methods that combine AI-based virtual reality following the growth of the emergence of digital service environments.

6. Conclusions

The conclusion of this study is as follows. First, it was identified that social benefits, psychological benefits, and economic benefits, which are leading variables of customer participation behaviors, directly affect customer participation behavior. Second, customer participation had a positive (+) effect on customer tolerance. Third, customer participation had a positive (+) effect on relationship commitment; however, there was no mediating effect of relationship commitment on the relationship between customer participation and repurchase intention. Fourth, customer tolerance showed a positive (+) effect on repurchase intentions. Fifth, relationship commitment did not have any significant effect on repurchase intentions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.-J.K.; methodology, S.-J.K.; validation, S.-J.K.; formal analysis, S.-J.K.; investigation, S.-J.K.; resources, S.-J.K.; data curation, S.-J.K.; writing—original draft preparation, S.-J.K.; writing—review and editing, S.-J.K.; visualization, S.-J.K.; supervision, S.-J.K. and B.-H.H.; project administration, S.-J.K. and B.-H.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ahn, Jinwoo. 2014. The relationship between customer participation behavior and civic behavior and commitment in the retail service industry. Marketing Management Research 19: 173–97. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, Jinwoo, and Hyungjun Oh. 2020. The relational role of customer engagement in the interaction process. Management and Information Research 39: 37–51. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, Jinwoo, and Moonsik Seo. 2009. The effect of customer participation on the interaction and emotional factors of service providers at service points: Focusing on the emotional theory of social exchange. Business Administration Research 38: 897–934. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, Jin-Woo, Myung-Hwan Cheon, and Han-Joo Kim. 2013. Structural study of customer participation and relationship commitment-Focused on hospital service. Management and Information Studies 32: 175–92. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, Natalic J., and John P. Meyer. 1990. The Measurement and Antecedents if Affective, Continuance and Normative Commitment to the Organization. Journal of Occupational Psychologies 63: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antwi, Samuel. 2021. I just like this e-Retailer”: Understanding online consumers repurchase intention from relationship quality perspective. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 61: 102–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, Richard P. 1992. The self-regulation of attitudes, intentions, and behavior. Social Psychology Quarterly 55: 178–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendapudi, Neeli, and Robert P. Leone. 2003. Psychological implications of customer participation in co-production. Journal of Marketing 67: 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, Leonard L., Anantharanthan Parasuraman, and Valarie A. Zeithaml. 1988. The service-quality puzzle. Business Horizons 31: 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitner, Mary Jo, Bernard H. Booms, and Mary Stanfield Tetreault. 1990. The Service Encounter: Diagnosing Favorable and Unfavorable Incidents. Journal of Marketing 54: 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitner, Mary Jo, William T. Faranda, Amy R. Hubbert, and Valarie A. Zeithaml. 1997. Customer contributions and roles in service delivery. International Journal of Service Industry Management 8: 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, David E., and Gareth R. Jones. 1986. Transaction cost analysis of service organization-customer exchange. Academy of Management Review 11: 428–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cermak, Dianne S. P., Karen Maru File, and Russ Alan Prince. 1994. Customer participation in service specification and delivery. Journal of Applied Business Research (JABR) 10: 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Woori, Park Jonghee, and Kim Doil. 2020. Effect of multidimensional benefits on consumer participation in service point of contact-Focused on service point of contact employee human service. Management and Information Research 39: 95–112. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, F. Robert, Paul H. Schurr, and Sejo Oh. 1987. Developing buyer-seller relationships. Journal of Marketing 51: 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, James F., and R. D. Blackwell. 1982. Retailing Crowding: Theoretical and Strategic Implication. Journal of Retailing 62: 346–63. [Google Scholar]

- Enright, Robert D., Elizabeth A. Gassin, and Ching-Ru Wu. 1992. Forgiveness: A developmental view. Journal of Moral Education 21: 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassin, Elizabeth A. 1995. Social Cognition and Forgiveness in Adolescents Romance: An Intervention Study. Unpublished Doctoral dissertation, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, USA. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/8bacbb48c6f7a89bd43cb994a2828268/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Gilliland, David I., and Daniel C. Bello. 2002. The Influence of Product Customization and Supplier Selection on Future Intentions: The Mediating Effects of Salesperson and Organizational Trust. Journal of Managerial Issues 13: 418–35. [Google Scholar]

- Gotlieb, Jerry B., Dhruv Grewal, and Stephen W. Brown. 1994. Consumer satisfaction and perceived quality: Complementary or divergent constructs? Journal of Applied Psychology 79: 875–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, Charles R., Robert F. Lusch, and Stephen L. Vargo. 2016. A service perspective. Organizational Dynamics 1: 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronroos, Christian. 1990. Service management: A management focus for service competition. International Journal of Service Industry Management 1: 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruen, Thomas W., John O. Summers, and Frank Acito. 2000. Relationship marketing activities, commitment, and membership behaviors in professional associations. Journal of Marketing 64: 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwinner, Kevin P., Dwayne D. Gremler, and Mary Jo Bitner. 1998. Relational benefits in services industries: The customer’s perspective. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 26: 101–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackett, Rick D., Petter Bycio, and Peter A. Hausdorf. 1994. Further Assessments of Meyer and Allen’s (1991) Three Component Model of Organizational Commitment. Journal of Applied Psychology 79: 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Sang-Rin, Jae-Won Yoo, and Tae-Sik Gong. 2004. The effect of customer participation behavior and civic behavior on service quality perception and repurchase intention: Focusing on non-profit university education services. Business Administration Research 33: 473–502. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, Christopher W., James L. Heskett, and W. Earl Sasser, Jr. 1990. The profitable art of service recovery. Harvard Business Review 68: 148–56. [Google Scholar]

- He, Hongwei, and Lloyd Harris. 2014. Moral disengagement of hotel guest negative WOM: Moral identity centrality, moral awareness, and anger. Annals of Tourism Research 45: 132–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headley, Dean E., and Stephen J. Miller. 1993. Measuring service quality and its relationship to future consumer behavior. Marketing Health Services 13: 32–41. [Google Scholar]

- Hepp, Martin. 2006. Semantic Web and semantic Web services: Father and son or indivisible twins? IEEE Internet Computing 10: 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, Ronald L., Jr., Shankar Ganesan, and Noreen M. Klein. 2003. Service failure and recovery: The impact of relationship factors on customer satisfaction. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 31: 127–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Byeong-Sook, Jin-Kwon Kwon, Seong-Hee Park, and In-Sun Baek. 2008. The effect of relationship benefits and relationship commitment in Internet shopping malls on word of mouth and repurchase intentions of cosmetic consumers. Journal of the Korean Society of Clothing and Textiles 32: 1202–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hsieh, An Tien, and En Ting Chang. 2004. The effect of consumer participation on price sensitivity. Journal of Consumer Affairs 38: 282–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbert, Amy Risch. 1995. Customer co-Creation of Service Outcomes: Effects of Locus of Causality Attributions. Ph.D. dissertation, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Kaltcheva, Velitchka D., Robert D. Winsor, and A. Parasuraman. 2013. Do customer relationships mitigate or amplify failure responses? Journal of Business Research 66: 525–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keaveney, Susan M. 1995. Customer switching behavior in service industries: An exploratory study. Journal of Marketing 59: 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keh, Hean Tat, and Chi Wei Teo. 2001. Retail customers as partial employees in service provision: A conceptual framework. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 29: 370–78. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, Scott W., James H. Donnelly, Jr., and Steven J. Skinner. 1990. Customer participation in service production and delivery. Journal of Retailing 66: 315–35. [Google Scholar]

- Kellogg, Deborah L., William E. Youngdahl, and David E. Bowen. 1997. On the Relationship Between Customer Participation and Satisfaction: Two Frameworks. International Journal of Service Management 8: 206–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Sanghee. 2012. Are all customers angry about the salesperson’s service failure?: The effect of customer attributions on the customer’s emotional and behavioral responses to the salesperson’s service failure. Marketing Research 27: 27–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Sanghee. 2014. Is service recovery done in the customer’s head? Is it done with the heart?: Comparison of the relative influence of fairness vs. authenticity. Business Administration Studies 43: 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Hyun-Kyung, and Hyun-JIN Cho. 2007. The effect of customer satisfaction and solidarity on repurchase intention-Focused on Internet shopping. Journal of Distribution Management 10: 81–102. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Kyung-Eun, and Seong-Do Cho. 2011. A study on the formation and role of relationship embedding in service employee and customer relationship. Marketing Research 26: 15–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Sang-Hyun, and Sang-Hyun Oh. 2002. Effect of customer value on customer satisfaction and repurchase intention. Management Research 17: 65–92. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, You-kyung, and Moon-Sik Seo. 2006. A study on the relationship between relational benefits and customer behavioral intentions in the service industry. Consumer Studies 17: 141–75. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Sujeong, Kim Kijoong, and Hyun Byunghwan. 2022. Does the relational benefit induce customer participation and thus tolerance towards service providers? Marketing Management Research 27: 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koc, Erdogan, Metin Ulukoy, Recep Kilic, Sedat Yumusak, and Reyhan Bahar. 2017. The influence of customer participation on service failure perceptions. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence 28: 390–404. [Google Scholar]

- Larsson, Rikard, and David E. Bowen. 1989. Organization and customer: Managing design and coordination of services. Academy of Management Review 14: 213–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawler, Edward J. 2001. An Affect Theory of Social Exchange. American Journal of Sociology 107: 321–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, Richard S. 1991. Emotion and Adaptation. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Yoon Jeong, and Chang Ro Lee. 2014. A comprehensive review of recent service marketing research and suggestions for future research. Marketing Research 29: 121–66. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, Xingyang, Yue Liu, Jingjing Luo, Yuqing Liu, and Chunxiao Li. 2021. Does a cute artificial intelligence assistant soften the blow? The impact of cuteness on customer tolerance of assistant service failure. Annals of Tourism Research 87: 103–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxham, James G., III. 2001. Service recovery’s influence on consumer satisfaction, positive word-of-mouth, and purchase intentions. Journal of Business Research 54: 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, Michael E., Everett L. Worthington, Jr., and Kenneth C. Rachal. 1997. Interpersonal forgiving in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 73: 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meichenbaum, Donald H., and Jerry L. Deffenbacher. 1988. Stress inoculation training. The Counseling Psychologist 16: 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, Peter K., and James H. Morris. 1986. Clients as “partial” employees of service organizations: Role development in client participation. Academy of Management Review 11: 726–35. [Google Scholar]

- Mowday, Richard T., Lyman W. Porter, and Richard M. Steers. 1982. Employee-Organization Linkages: The Psychology of Commitment, Absenteeism, and Turnover. New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Newton, Joshua D., Jimmy Wong, and Riza Casidy. 2018. Deck the halls with boughs of holly to soften evaluations of service failure. Journal of Service Research 21: 389–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmatier, Robert W., Rajiv P. Dant, Dhruv Grewal, and Kenneth R. Evans. 2006. Factors Influencing the Effectiveness of Relationship Marketing: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Marketing 70: 136–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Jong-Hee. 2007. The effect of perceived organizational citizenship behavior and customer participation in university education service on customer satisfaction and organizational identification. Marketing Management Research 12: 19–42. [Google Scholar]

- Rodie, Amy Risch, and Susan Schultz Kleine. 2000. Customer participation in services production and delivery. Handbook of Services Marketing and Management 33: 111–26. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, Moon-Sik, Jin-Woo Ahn, and Tae-Seok Roh. 2010. Customer participation in service contact point, its voluntary determinants and its influence on service quality: Focusing on self-determination theory. Consumption Culture Research 13: 61–93. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Amy K., Ruth N. Bolton, and Janet Wagner. 1999. A Model of Customer Satisfaction with Service encounters Involving failure and recovery. Journal of Marketing Research 36: 356–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, Michael R., Carol Surprenant, John A. Czepiel, and Evelyn G. Gutman. 1985. A role theory perspective on dyadic interactions: The service encounter. Journal of Marketing 49: 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tax, Stephen S., Stephen W. Brown, and Murali Chandrashekaran. 1998. Customer evaluations of Service complaint experiences: Implications for relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing 62: 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, Stephen L., and Robert F. Lusch. 2004. Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. Journal of Marketing 68: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagil, Dana, and Gil Luria. 2016. Customer forgiveness of unsatisfactory service: Manifestations and antecedents. Service Business 10: 557–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, HsiuJu Rebecca, Kevin P. Gwinner, and Wanru Su. 2004. The impact of customer participation and service expectation on Locus attributions following service failure. International Journal of Service Industry Management 15: 7–26. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, You Jae, and Tae Shik Gong. 2005. Effect of customer citizenship behavior and bad customer behavior on service quality perception, customer satisfaction and repurchase intention. Asia Marketing Journal 7: 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, Man-hee, Kim Jeong-Seop, and Kim Ji-Han. 2005. The effect of service customers’ personal values and service contact characteristics on customer participation behavior. Marketing Management Research 10: 139–63. [Google Scholar]

- Zeithaml, Valarie A., Arun Parasuraman, and Arvind Malhotra. 2002. Service quality delivery through web sites: A critical review of extant knowledge. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 30: 362–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, Valarie A., Leonard L. Berry, and Ananthanarayanan Parasuraman. 1996. The behavioral consequences of service quality. Journal of Marketing 60: 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).