The Trade Growth under the EU–SADC Economic Partnership Agreement: An Empirical Assessment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. A Brief Literature Review

3. Empirical Specification

3.1. Intensive Margin: Difference-in-Differences (DID) Analysis

3.2. Extensive Margin: A Probit Analysis

4. Data Sources and Descriptives

5. Discussion of Results

6. Conclusions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The EPA entered into force provisionally on 10 October 2016 and Mozambique has been applying it provisionally since 4 February 2018. |

References

- Álvarez, Roberto, and Ricardo A. López. 2008. Trade Liberalization and Industry Dynamics: A Difference in Difference Approach. Working Papers Central Bank of Chile 470. San Diego: Central Bank of Chile. [Google Scholar]

- Amiti, Mary, Mi Dai, Robert C. Feenstra, and John Romalis. 2020. How did China’s WTO entry affect U.S. prices? Journal of International Economics 126: 103339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, James E., and Eric van Wincoop. 2003. Gravity with gravitas: A solution to the border puzzle. American Economic Review 93: 170–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashenfelter, Orley, and David Card. 1985. Using the Longitudinal Structure of Earnings to Estimate the Effect of Training Programs. In The Review of Economics and Statistics. Cambridge: MIT Press, vol. 67, pp. 648–60. [Google Scholar]

- Augier, Patricia, Michael Gasiorek, and Gonzalo Varela. 2007. Determinants of Productivity in Morocco—The Role of Trade? CARIS Working Papers 02. Brighton: Centre for the Analysis of Regional Integration at Sussex, University of Sussex. [Google Scholar]

- Bigsten, Arne, and Mulu Gebreeyesus. 2009. Firm Productivity and Exports: Evidence from Ethiopian Manufacturing. Journal of Development Studies 45: 1594–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigsten, Arne, and Mans Söderbom. 2010. African Firms in the Global Economy. Review of Market Integration 2: 229–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bombarda, Pamela, and Elisa Gamberoni. 2013. Firm heterogeneity, rules of origin and rules of cumulation. International Economic Review 54: 307–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouët, Antoine, David Laborde Debucquet, and Fousseini Traoré. 2021. MIRAGRODEP Dual-Dual (MIRAGRODEP-DD) with an Application to the EU-Southern African Development Community (SADC) Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA), IFPRI AGRODEP Technical Note 0021. Available online: https://www.ifpri.org/series/agrodep-technical-note (accessed on 2 October 2022).

- Brenton, Paul, and Miriam Manchin. 2003. Making EU trade agreements work: The role of rules of origin. The World Economy 26: 755–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau, Jean-Christophe, Raja Chakir, and Jacques Gallezot. 2007. The utilisation of trade preference for developing countries in the agri-food sector. Journal of Agricultural Economics 58: 175–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, Rodolfo G., Jacopo Timini, and Elena Vidal Muñoz. 2021. Structural Gravity and Trade Agreements: Does the Measurement of Domestic Trade Matter? Documentos de Trabajo. N.º 2117. Madrid: BANCO DE ESPAÑA. [Google Scholar]

- Cernat, Lucien, Daphne Gerard, Oscar Guinea, and Lorenzo Isella. 2018. Consumer Benefits from EU Trade Liberalisation: How Much Did We Save Since the Uruguay Round? DG TRADE Chief Economist Notes 2018-1. Brussels: Directorate General for Trade, European Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Cerqua, Augusto, Pierluigi Montalbano, and Zhansaya Temerbulatova. 2021. A Decade of Eurasian Integration: An Ex-Post Non-Parametric Assessment of the Eurasian Economic Union. Working Papers 1/21. Rome: Sapienza University of Rome, DISS. [Google Scholar]

- Cipollina, Maria, and Luca Salvatici. 2010. The trade impact of European Union agricultural preferences. Journal of Economic Policy Reform 13: 87–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipollina, Maria, and Luca Salvatici. 2019. The Trade Impact of EU Tariff Margins: An Empirical Assessment. Social Sciences 8: 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clausing, Kimberly A. 2001. Trade Creation and Trade Diversion in the Canada-United States Free Trade Agreement. Canadian Journal of Economics 34: 677–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Loecker, Jan, Pinelopi K. Goldberg, Amit K. Khandelwal, and Nina Pavcnik. 2016. Process, Mark-ups, and Trade Reform. Econometrica 84: 445–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Melo, Jaime, and Julie Regolo. 2014. The African Economic Partnership Agreements with the EU: Reflections inspired by the case of the East African Community. Journal of African Trade 1: 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debaere, Peter, and Mostashari Shalah. 2010. Do Tariffs Matter for the Extensive Margin of International Trade? An Empirical Analysis. Journal of International Economics 81: 163–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decaluwe, Bernard, David Laborde, Helene Maisonnave, and V. Robichaud. 2008. Regional CGE Modeling for West Africa: An EPA Study. Report for the EC and ECOWAS secretariats. Paris: ITAQA Sarl, vol. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Fally, Thibault. 2015. Structural Gravity and Fixed Effects. Journal of International Economics 97: 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feenstra, Robert C. 1994. New product varieties and the measurement of international prices. American Economic Review 84: 157–77. [Google Scholar]

- Feenstra, Robert C. 2010. Measuring the gains from trade under monopolistic competition. Canadian Journal of Economics 43: 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feenstra, Robert C., and Hiau Looi Kee. 2008. Export variety and country productivity: Estimating the monopolistic competition model with endogenous productivity. Journal of International Economics 74: 500–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felbermayr, Gabriel J., and Wilhelm Kohler. 2006. Exploring the Intensive and Extensive Margins of World Trade. Review of World Economics/Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv 142: 642–74. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40441114 (accessed on 30 September 2022). [CrossRef]

- Fontagne, Lionel, Cristina Mitaritonna, and David Laborde. 2011. An impact study of the EU ACP Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs) in the six ACP regions. Journal of African Economies 20: 179–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Frazer, Garth, and Johannes Van Biesebroeck. 2010. Trade growth under the African Growth and Opportunity Act. The Review of Economics and Statistics 92: 128–44. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25651394 (accessed on 3 September 2022). [CrossRef]

- Fredriksson, Anders, and Gustavo Magalhães de Oliveira. 2019. Impact evaluation using Difference-in-Differences. RAUSP Management Journal 54: 519–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan, Swarnali A. 2016. The Impact of Trade Agreements: New Approach, New Insights. IMF Working Papers 2016/117. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Hinz, Julian, Amrei Stammann, and Joschka Wanner. 2019. Persistent Zeros: The Extensive Margin of Trade. Kiel Working Papers 2139. Kiel: Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW Kiel). [Google Scholar]

- Hummels, David, and Peter J. Klenow. 2005. The variety and quality of a nation’s exports. The American Economic Review 95: 704–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, Gunnar, and Arvind Subramanian. 2001. Dynamic Gains from Trade: Evidence from South Africa. IMF Staff Papers 48: 197–224. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4621665 (accessed on 13 October 2022).

- Keck, Alexander, and Roberta Piermartini. 2008. The impact of Economic Partnership Agreements in countries of the Southern African Development Community. Journal of African Economies 17: 85–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayda, Anna Maria, and Chad Steinberg. 2009. Do South-South Trade Agreements Increase Trade? Commodity-Level Evidence from Comesa. The Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue Canadienne d’Economique 42: 1361–89. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40389534 (accessed on 3 September 2022). [CrossRef]

- Osman, Rehab O. M. 2014. SADC trade with the European Union from a preferential to a reciprocal modality. South African Journal of Economics 83: 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paha, Johannes, Timon Sautter, and Reinhard Schumacher. 2021. Some Effects of EU Sugar Reforms on Development in Africa. Intereconomics 56: 288–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portugal-Perez, Alberto. 2008. The Costs of Rules of Origin in Apparel: African Preferential Exports to the United States and the European Union. Policy Issues in International Trade and Commodities Study Series 39; Geneva: UNCTAD. [Google Scholar]

- Ricardo, David. 1951. On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation (John Murray, London). In The Works and Correspondence of David Ricardo. Edited by P. Sraffa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, vol. 1. First published 1817. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrik, Dani. 1992. The Limits of Trade Policy Reform in Developing Countries. The Journal of Economic Perspectives 6: 87–105. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2138375 (accessed on 30 August 2022). [CrossRef]

- Rodrik, Dani. 2018. What Do Trade Agreements Really Do? Journal of Economic Perspectives 32: 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romalis, John. 2007. NAFTA’s and CUSFTA’s Impact on International Trade. The Review of Economics and Statistics 89: 416–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos Silva, João M. C., and Silvana Tenreyro. 2006. The log of gravity. Review of Economics and Statistics 88: 641–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos Silva, João M. C., and Silvana Tenreyro. 2011. Further simulation evidence on the performance of the Poisson pseudo-maximum likelihood estimator. Economics Letters 112: 220–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoppola, Margherita, Valentina Raimondi, and Alessandro Olper. 2018. The impact of EU trade preferences on the extensive and intensive margins of agricultural and food products. In Agricultural Economics. Milwaukee: International Association of Agricultural Economists, vol. 49, pp. 251–63. [Google Scholar]

- Stender, Frederik, Axel Berger, Clara Brandi, and Jakob Schwab. 2021. The Trade Effects of the Economic Partnership Agreements between the European Union and the African, Caribbean and Pacific Group of States: Early Empirical Insights from Panel Data. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 59: 1495–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sytsma, Tobias. 2021. Rules of origin and trade preference utilization among least developed countries. Contemporary Economic Policy 39: 701–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Biesebroeck, Johannes, Yingting Yi, and Elena Zaurino. 2022. Trade liberalisation and the extensive margin of differentiated goods: Evidence from China. The World Economy 45: 2724–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolcock, Stephen. 2019. The role of the European Union in the international trade and investment order. In LSE Research Online Documents on Economics 102821. London: London School of Economics and Political Science, LSE Library. [Google Scholar]

| Status | Trade Effect | Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Post-Treatment | Pre-Treatment | ||

| Treated | α + β + γ + δ | α + β | γ + δ |

| Control | α + γ | α | γ |

| Difference-in-differences | δ | ||

| Total Sample | 2012–2015 | 2016–2019 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Mean | Max | Min | Mean | Max | |

| Trade (Ml) | 0 | 5.999 | 132,369 | 0 | 5.776 | 71,752 |

| MFN duty (%) | 0 | 4.41 | 74.90 | 0 | 4.34 | 74.90 |

| Preferential applied tariff (%) | 0 | 0.38 | 52.4 | 0 | 0.16 | 52.4 |

| No. of obs. with positive trade (No. of all obs.) | 813,190 (1,588,144) | 899,778 (1,588,144) | ||||

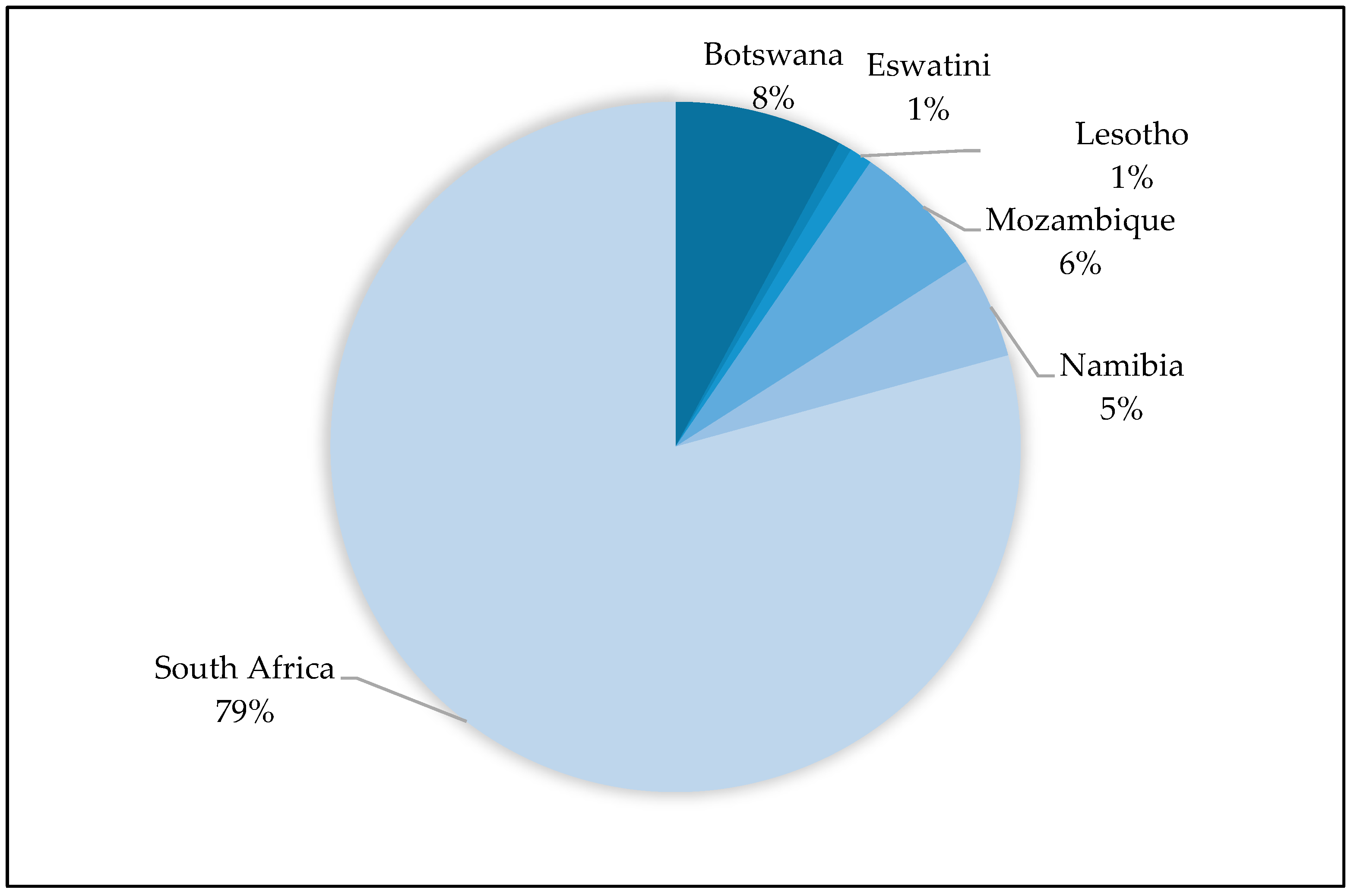

| SADC EPA countries | ||||||

| Trade (Ml) | 0 | 2.946 | 4324 | 0 | 3.102 | 4269 |

| MFN duty (%) | 0 | 4.34 | 74.9 | 0 | 4.27 | 74.90 |

| Preferential applied tariff (%) | 0 | 0.07 | 25.9 | 0 | 0.05 | 29.44 |

| No. of obs. with positive trade (No. of all obs.) | 18,221 (36,724) | 21,095 (39,674) | ||||

| RoW | ||||||

| Trade (Ml) | 0 | 6.071 | 132,369 | 0 | 5.846 | 71,752 |

| MFN duty (%) | 0 | 4.41 | 74.90 | 0 | 4.35 | 74.90 |

| Preferential applied tariff (%) | 0 | 0.39 | 74.90 | 0 | 0.16 | 52.40 |

| No. of obs. with positive trade (No. of all obs.) | 794,969 (1,551,420) | 878,683 (1,548,470) | ||||

| Countries | 2012–2015 | 2016–2019 |

|---|---|---|

| SADC EPA countries | 98 | 99 |

| RoW | 88 | 89 |

| Share of Tariff Lines (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| 2012–2015 | 2016–2019 | |

| Free trade (MFN duty = 0) | 22 | 24 |

| Preferential duty-free | 77 | 75 |

| Tariffs under 5% | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| Tariffs between 5% and 10% | 0.4 | 0.2 |

| Tariffs between 10% and 25% | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| Tariffs over 25% | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Status | Average Annual Growth Rate (%) | Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2012–2015 | 2016–2019 | ||

| SADC EPA countries | 0.4 | 9 | 8.60 |

| RoW | 0.1 | 4 | 3.90 |

| Difference-in-Differences | 4.70 | ||

| Exporting Country | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

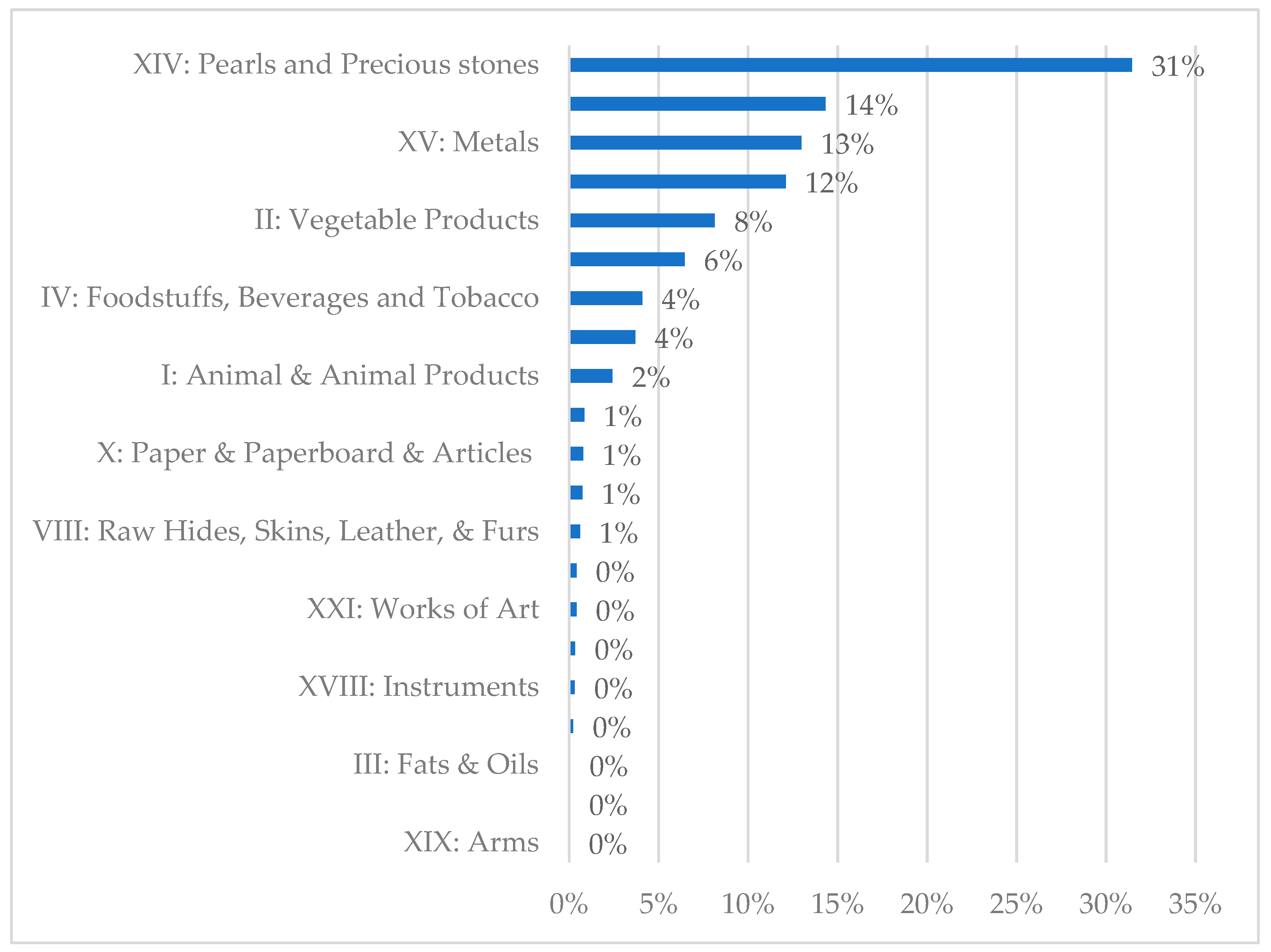

| All Exported Goods | Newly Traded Goods | Disappearing Goods | Continuously Traded Goods | |

| Botswana | 740 | 39% | 30% | 31% |

| Eswatini | 1211 | 49% | 20% | 31% |

| Lesotho | 227 | 43% | 34% | 22% |

| Mozambique | 1475 | 14% | 51% | 36% |

| Namibia | 2425 | 51% | 9% | 40% |

| South Africa | 4549 | 14% | 6% | 79% |

| RoW | 5465 | 5% | 0% | 95% |

| PPML | |

|---|---|

| −0.90 *** | |

| (0.19) | |

| 0.24 *** | |

| (0.09) | |

| Constant | 13.67 *** |

| (0.00) | |

| Fixed effect | Country-product Country-year Product-year |

| N | 3,103,832 |

| pseudo R2 | 0.990 |

| PPML | ||

|---|---|---|

| −0.16 | (0.11) | |

| Botswana | 0.87 *** | (0.25) |

| Eswatini | −0.22 | (0.48) |

| Lesotho | −0.03 | (0.17) |

| Mozambique | −0.89 *** | (0.23) |

| Namibia | −0.39 * | (0.20) |

| South Africa | 0.29 *** | (0.10) |

| Constant | 13.67 *** | (0.00) |

| Fixed effect | Country-product Country-year Product-year | |

| N | 3,103,832 | |

| pseudo R2 | 0.990 | |

| PPML | ||

|---|---|---|

| −0.55 *** | (0.16) | |

| I: Animal & Animal Products | 0.21 ** | (0.09) |

| II: Vegetable Products | 0.11 | (0.08) |

| III: Fats & Oils | 0.14 | (0.19) |

| IV: Foodstuffs, Beverages and Tobacco | 0.03 | (0.09) |

| V: Mineral Products | 0.50 ** | (0.21) |

| VI: Chemicals & Allied Industries | 0.23 | (0.17) |

| VII: Plastics/Rubbers | 0.01 | (0.14) |

| VIII: Raw Hides, Skins, Leather, & Furs | 0.39 ** | (0.15) |

| IX: Wood & Articles of Wood | 0.41 *** | (0.14) |

| XI: Textiles | 0.05 | (0.10) |

| XII: Footwear/Headgear | 0.27 ** | (0.12) |

| XIII: Stone/Glass | 0.19 | (0.13) |

| XIV: Pearls and Precious stones | 0.24 | (0.16) |

| XV: Metals | −0.34 *** | (0.10) |

| XVI: Machineries | −0.30 *** | (0.11) |

| XVII:Transport | 0.79 *** | (0.15) |

| XVIII: Instruments | −0.03 | (0.14) |

| XX: Misc. Manufactured Articles | −1.10 *** | (0.28) |

| Constant | 13.67 *** | (0.00) |

| Fixed effect | Country-product Country-year Product-year | |

| N | 3,103,832 | |

| pseudo R2 | 0.990 | |

| Coeff. | Marginal Effect | Coeff. | Marginal Effect | Coeff. | Marginal Effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −0.01 | −0.00 | −0.03 * | −0.01 * | −0.03 | −0.01 | |

| (0.01) | (0.00) | (0.02) | (0.00) | (0.02) | (0.00) | |

| 0.06 *** | 0.01 *** | 0.05 *** | 0.01 *** | 0.05 *** | 0.01 *** | |

| (0.02) | (0.00) | (0.02) | (0.00) | (0.02) | (0.00) | |

| −0.28 *** | −0.05 *** | −0.15 *** | −0.03 *** | −0.15 *** | −0.03 *** | |

| (0.03) | (0.00) | (0.03) | (0.01) | (0.03) | (0.01) | |

| Constant | −6.02 *** | −5.59 | −5.50 | |||

| (0.00) | (4.00) | (4.01) | ||||

| Fixed effect | Year | Year Country | Year Country Sector | |||

| N | 2,773,212 | 2,773,212 | 2,773,212 | |||

| pseudo R2 | 0.067 | 0.093 | 0.094 |

| Coeff. | Marginal Effect | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| −0.08 *** | (0.01) | −0.03 *** | (0.00) | |

| Botswana | −0.29 *** | (0.04) | −0.10 *** | (0.01) |

| Eswatini | 0.07 ** | (0.03) | 0.02 *** | (0.01) |

| Lesotho | −0.17 *** | (0.06) | −0.06 *** | (0.02) |

| Mozambique | 0.08 ** | (0.03) | 0.02 ** | (0.01) |

| Namibia | 0.17 *** | (0.02) | 0.05 *** | (0.01) |

| South Africa | −0.07 *** | (0.02) | −0.02 *** | (0.01) |

| −0.13 *** | (0.03) | −0.04 *** | (0.01) | |

| Constant | −0.94 *** | (0.01) | ||

| Fixed effect | Year Country Sector | |||

| N | 3,169,728 | |||

| pseudo R2 | 0.154 | |||

| Coeff. | Marginal Effect | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| −0.08 *** | (0.01) | −0.02 *** | (0.00) | |

| I: Animal & Animal Products | 0.16 *** | (0.04) | 0.05 *** | (0.01) |

| II: Vegetable Products | 0.09 *** | (0.03) | 0.03 *** | (0.01) |

| III: Fats & Oils | −0.13 | (0.09) | −0.04 | (0.03) |

| IV: Foodstuffs, Beverages and Tobacco | 0.03 | (0.04) | 0.01 | (0.01) |

| V: Mineral Products | 0.36 *** | (0.10) | 0.12 *** | (0.03) |

| VI: Chemicals & Allied Industries | −0.00 | (0.02) | −0.00 | (0.01) |

| VII: Plastics/Rubbers | −0.00 | (0.03) | −0.00 | (0.01) |

| VIII: Raw Hides, Skins, Leather, & Furs | 0.05 | (0.06) | 0.02 | (0.02) |

| IX: Wood & Articles of Wood | −0.10 | (0.06) | −0.03 *** | (0.01) |

| XI: Textiles | −0.19 *** | (0.02) | −0.06 *** | (0.01) |

| XII: Footwear/Headgear | −0.07 | (0.06) | −0.02 | (0.02) |

| XIII: Stone/Glass | −0.06 | (0.04) | −0.02 | (0.01) |

| XIV: Pearls and Precious stones | 0.56 *** | (0.12) | 0.19 *** | (0.04) |

| XV: Metals | 0.21 *** | (0.03) | 0.07 *** | (0.01) |

| XVI: Machineries | 0.01 | (0.02) | 0.00 | (0.01) |

| XVII:Transport | 0.15 *** | (0.04) | 0.05 *** | (0.01) |

| XVIII: Instruments | −0.06 * | (0.04) | −0.02 * | (0.01) |

| XX: Misc. Manufactured Articles | −0.05 | (0.04) | −0.02 | (0.01) |

| −0.12 *** | (0.03) | −0.04 *** | (0.01) | |

| Constant | −0.94 *** | (0.01) | ||

| Fixed effect | Year Country Sector | |||

| N | 3,169,728 | |||

| pseudo R2 | 0.139 | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cipollina, M. The Trade Growth under the EU–SADC Economic Partnership Agreement: An Empirical Assessment. Economies 2022, 10, 302. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies10120302

Cipollina M. The Trade Growth under the EU–SADC Economic Partnership Agreement: An Empirical Assessment. Economies. 2022; 10(12):302. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies10120302

Chicago/Turabian StyleCipollina, Maria. 2022. "The Trade Growth under the EU–SADC Economic Partnership Agreement: An Empirical Assessment" Economies 10, no. 12: 302. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies10120302

APA StyleCipollina, M. (2022). The Trade Growth under the EU–SADC Economic Partnership Agreement: An Empirical Assessment. Economies, 10(12), 302. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies10120302