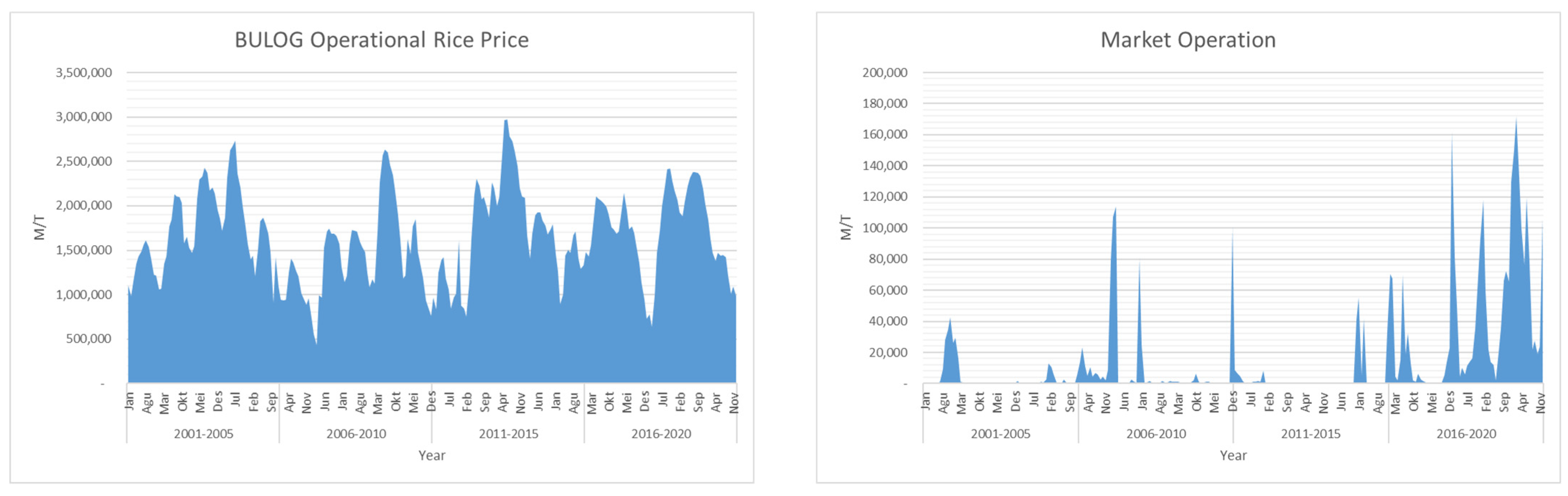

4.1. The Influence of BULOG’s Market Share on Consumer-Level Rice Prices

On the basis of the results of the stationarity test (unit root test) in

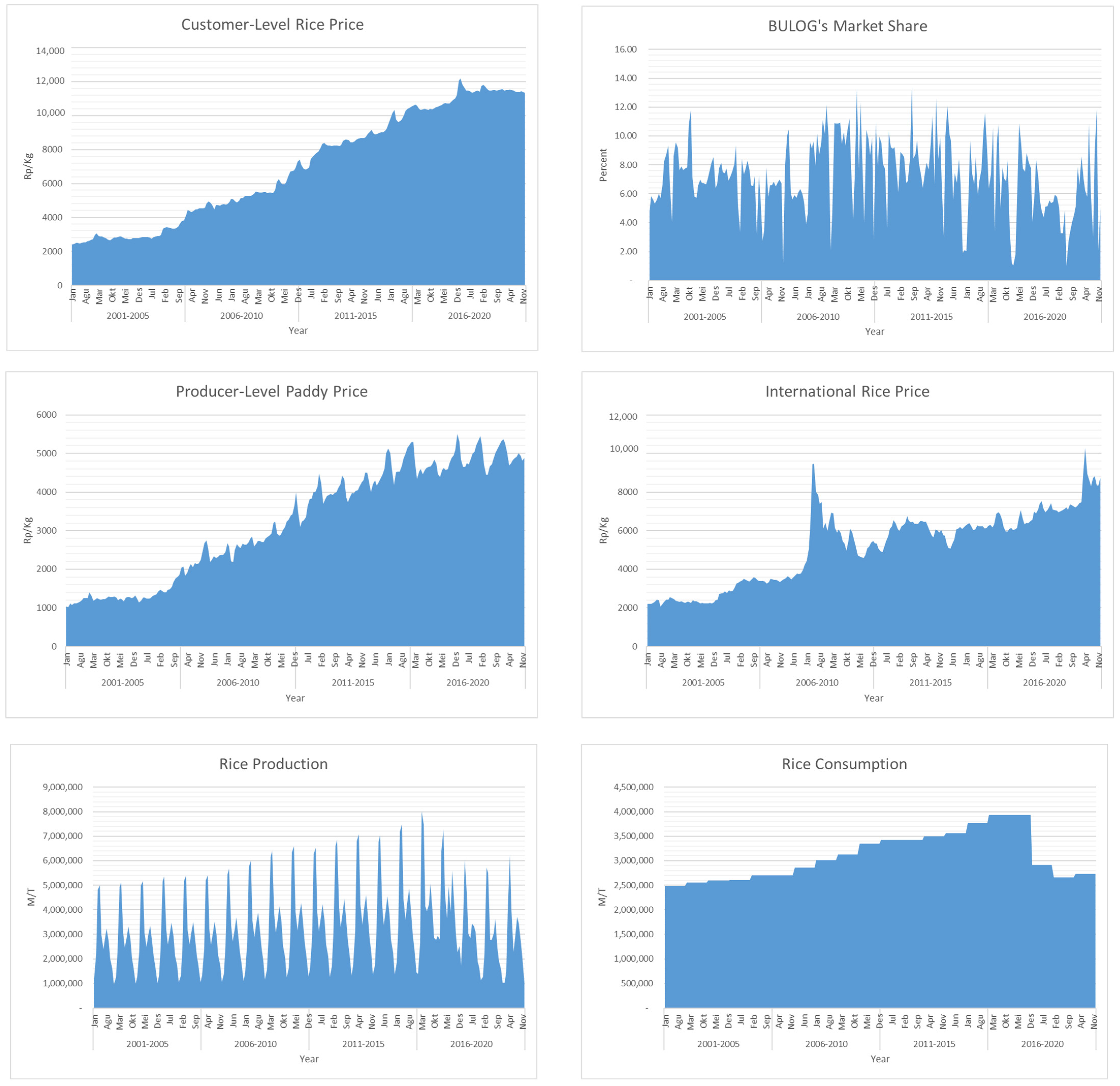

Table 2, it can be concluded that the data on consumer-level rice price (CRP), BULOG’s market share (BMS), producer-level paddy price (PPP), international rice price (IRP), rice production (PROD), rice consumption (CONS), BULOG’s operational rice stock (STOCK), dummy highest retail price (DHRP), and dummy continuous market operation (DCMO) are stationary at level, but all variables are not stationary on first difference because the probability value of unit root test on first difference < 0.05, so the data are eligible to use ARDL analysis (

Pesaran and Shin 2012).

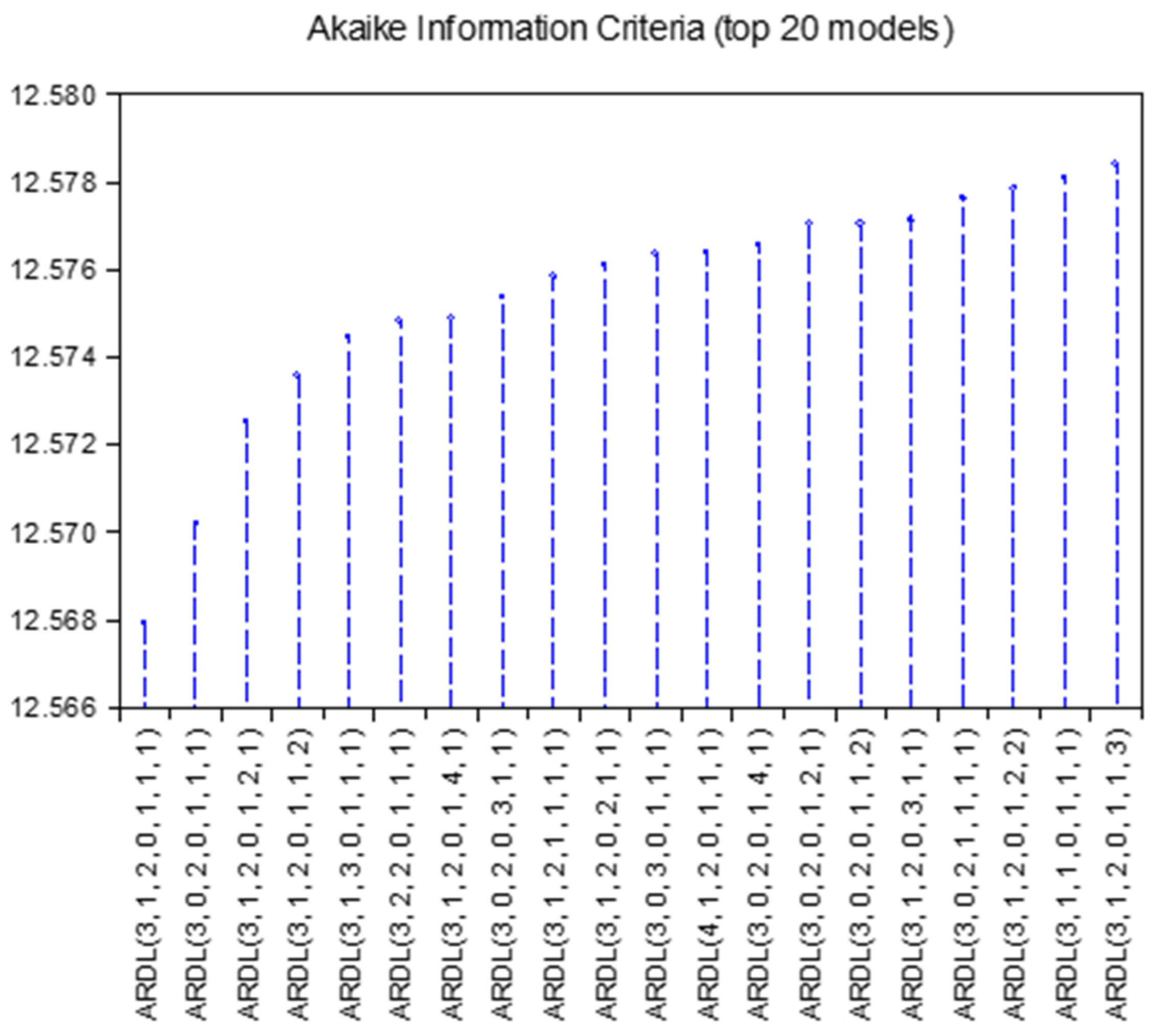

The ARDL analysis results in

Table 3 show that the R-squared model is 99.49%, with the F-test showing a Prob value of 0.0000 < 0.05 so that together the research variables are proven to significantly affect the consumer-level rice price (CRP).

The

t-test to examine the effect of the variable on the consumer-level rice price (CRP) shows that the influential variables with the coefficient signs following the hypothesis are the consumer-level rice price (CRP) itself at lags 1, 2, and 3; BULOG’s market share (BMS) at lag 0; producer-level paddy price (PPP) at lags 0 and 1; rice production (PROD) at lag 1; rice consumption (CONS) at lags 0 and 1; and BULOG stock at lags 0 and 1. While international rice price (IRP) does not affect consumer-level rice prices, the highest retail price (DHRP) policy has no effect on the formation of consumer-level rice prices (compared with when there is no highest retail price policy). Likewise, the continuous market operation (DCMO) policy has no effect on the formation of consumer-level rice prices (compared with the non-continuous market operation policy). The ARDL model formed is ARDL (3, 1, 2, 0, 1, 1, 1) according to the optimal lag selected on the basis of the Akaike Information Criteria in

Figure 6.

Furthermore, the Cointegration Test is conducted to see if there is a long-term relationship between research variables using the Bound Test. On the basis of the test results in

Table 4, it is concluded that there is a long-term relationship between research variables because the value of the obtained F statistic (7.8811) is greater than the upper bound.

Furthermore, the results of the analysis of the long-term effect in

Table 5 show that the independent variables that affect the consumer-level rice prices (CRP) in the long run are BULOG’s market share (BMS), producer-level paddy price (PPP), and rice consumption (CONS), while the variables of international rice prices (IRP), rice production (PROD), BULOG’s operational stock (STOCK), continuous market operation (compared with the non-continuous market operation policy), and highest retail price (compared with when there is no highest retail price policy), have no effect on consumer-level rice prices in the long-term.

The results of the Breusch–Godfrey Autocorrelation Test in

Table 6 show that the Prob.F value is 0.7064 > 0.05, which means that the H

0 hypothesis test is accepted; thus, there is no autocorrelation among research variables.

The results of the ARCH Heteroscedasticity Test in

Table 7 show that the Prob.F value is 0.1397 > 0.05, which means that the H

0 hypothesis test indicates that there is no heteroscedasticity among research variables.

The Ramsey RESET Stability Test results in

Table 8 show that the Prob t-Statistic value is 0.1390 > 0.05 and the Prob F-statistic value is 0.1390 > 0.05, which means that the hypothesis test H

0 is accepted, namely that the model formed is stable to be used.

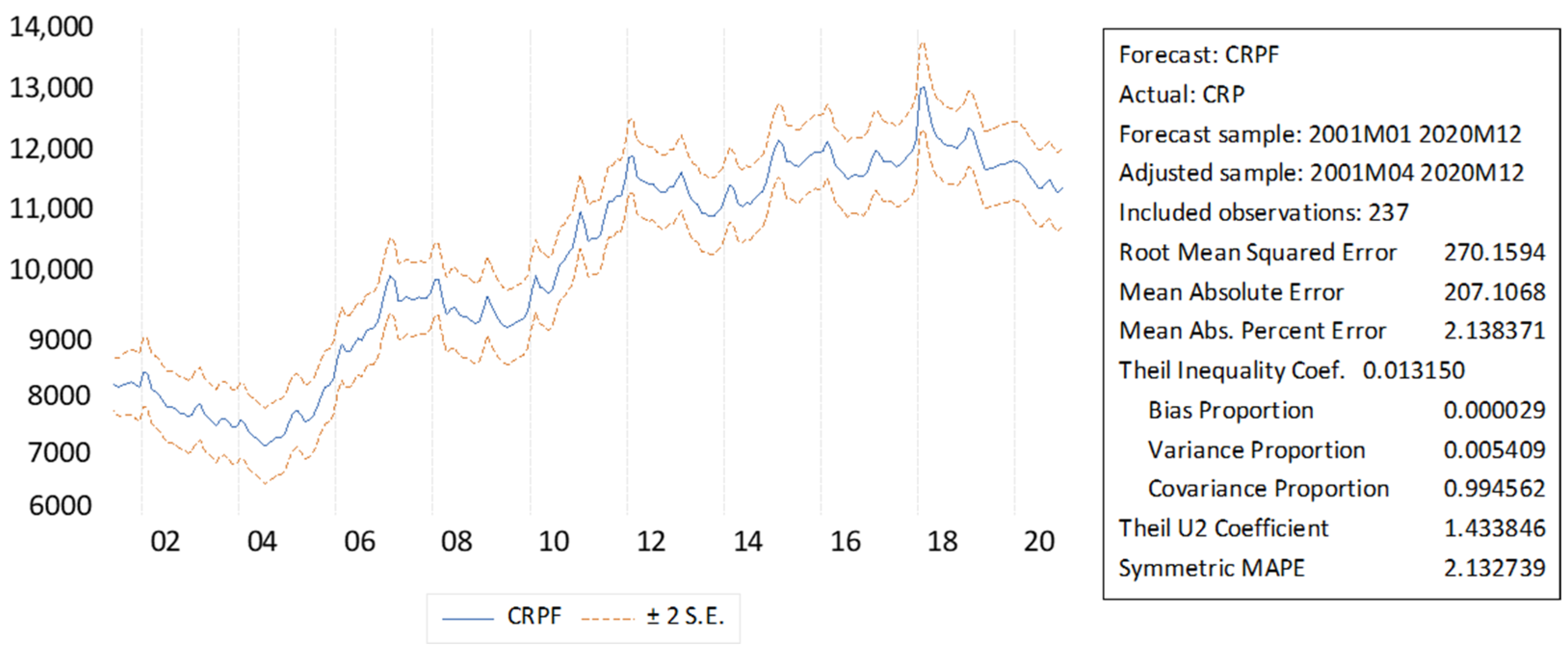

The results of the calculation of Mean Square Error (MSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) to examine the level of deviation of the forecast results in the model are shown in

Figure 7. The value of MSE = 270.15; MAE = 207.11; and MAPE = 2.14%. Because the MAPE value is less than 10%, the forecasting model category is very good.

On the basis of the analysis results, it is shown that the consumer-level rice price is influenced by the consumer-level rice price itself until the third time lag or the price of the previous three months. This result is in accordance with research from

Marjuki (

2009). The consumer-level rice price is also influenced by the amount of rice production and has a negative coefficient sign, meaning that the greater the production, the more the price will tend to fall. The same conclusion is reached by

Setiawati et al. (

2018), who analyzed the effect of production on rice prices along with the rupiah exchange rate variable.

The consumer-level rice price is also influenced by the amount of rice consumption and has a positive coefficient sign, meaning that the greater the consumption, the higher the price. On the contrary causality, according to

Bashir and Yuliana (

2019), the price of rice also affects rice consumption, along with the variables of labour, wages, wetland, and urban population.

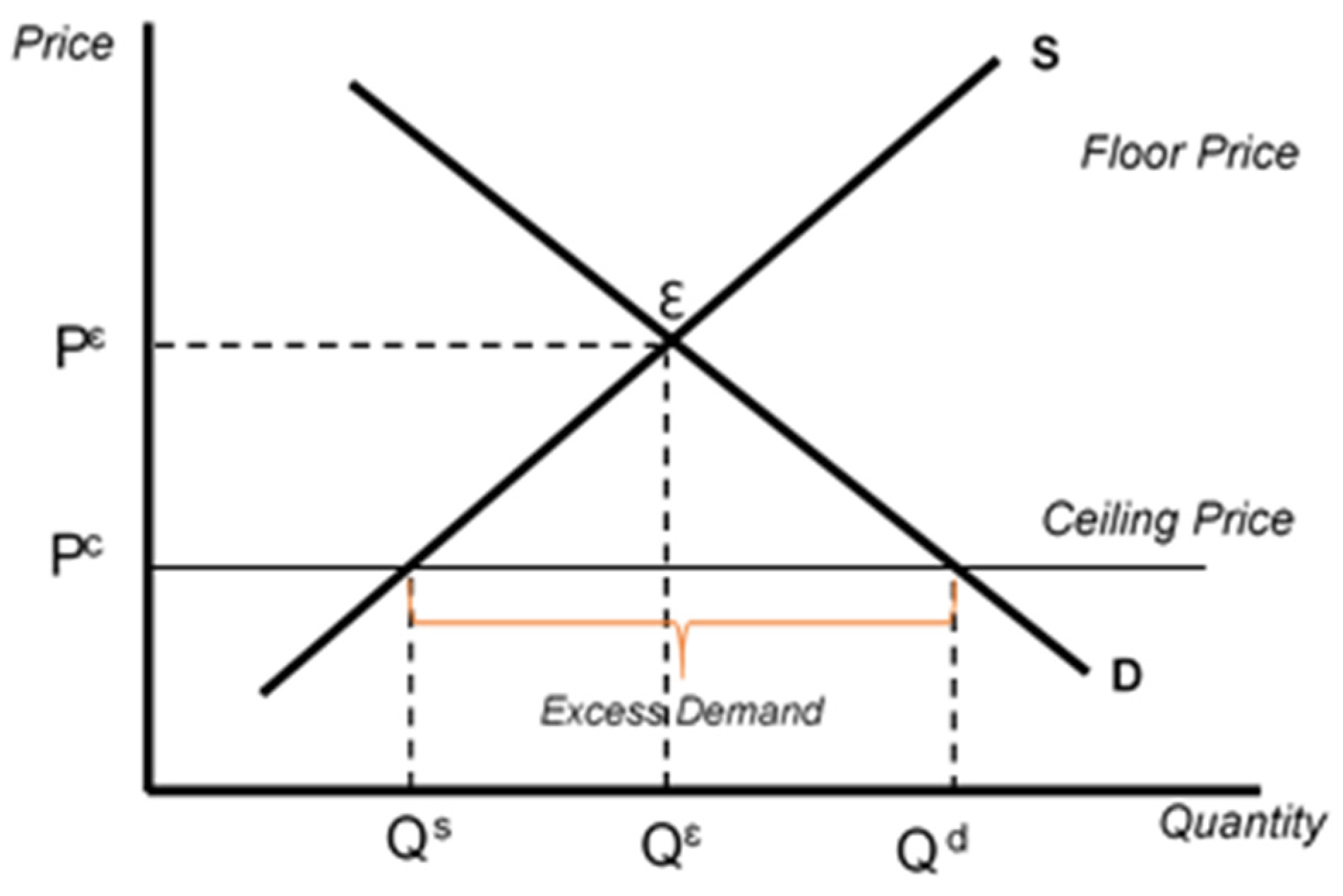

BULOG’s operational stock, which consists of government rice reserves (CBP) and commercial stocks, proved to have an effect in the same month and one month earlier on the formation of consumer-level rice prices and has a negative coefficient sign, meaning that the larger the stock controlled by BULOG, the lower the price. This confirms that the market still sees BULOG’s control of the rice stock as a sign of the market’s balance of supply and demand (2019). The larger the BULOG’s operational rice stock, the larger the excess supply in the market. The BULOG’s operational rice stock is also considered a measure of the government’s ability to intervene in the market, although in the long term, data analysis shows that BULOG’s operational rice stock does not affect consumer-level rice prices. Based on other research, such as that conducted by

Setyoaji et al. (

2014) on data in the East Java region, which is the largest rice-producing region in Indonesia, the impact of BULOG’s rice stock on rice prices is significant in both the short and long term.

The analysis results show that international rice prices do not affect consumer-level rice prices in Indonesia, both in the short and long term. Although Indonesia still imports rice from other countries several times, there are several reasons why international rice prices do not have a significant effect. First, rice import and export permits are only granted to BULOG and cannot be carried out freely by private companies, except for special rice such as aromatic rice, diabetics rice, etc. Second, imported rice is stored in BULOG warehouses as a buffer for the national stock and is issued only for certain special purposes so that the purchase price of imported rice does not directly affect the equilibrium of rice prices in the Indonesian market. Additionally, the third reason is that Indonesia is a country that received an award for self-sufficiency in rice from the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) several times, so most of the public’s consumption can be met through domestic production.

On the basis of the data from the last 20 years, it can be seen that rice imports in Indonesia in 2011 were as much as 2.2 million metric tons, or approximately 5.4% of the national rice demand. Meanwhile, in other years, the average import of rice was just under 100,000 metric tons (less than 0.25% of consumption needs). The imported rice is stored in BULOG warehouses throughout Indonesia as a national food reserve and released gradually up to 2–3 years later through food assistance programs and market operations so that it does not directly affect rice supply in the domestic market. From 2019 until now, Indonesia has never again imported medium-quality rice from abroad and can meet its needs from domestic production. Even during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, rice production in Indonesia was quite high, and there were no significant supply and demand shocks.

According to the research of

Sugiyanto and Hadiwigeno (

2012), the international rice market is integrated with the Indonesian rice market, which means that changes in rice prices abroad still affect rice prices in Indonesia. However, the effect of international rice prices is not significant when compared with the larger influence of other variables in this study. There is no significant difference between before and after the implementation of the highest retail price (HET) policy on the consumer-level of rice prices. However, according to

Fatimah (

2018), the highest retail price policy positively affects farmers’ exchange rates. Likewise, there is no significant difference in influence between the continuous market operation policy and the market operation model that was carried out previously. In many previous studies, the BULOG market operation program has had a significant effect on rice prices and inflation in Indonesia (

Proborini et al. 2018;

Rahmasuciana et al. 2016;

Resnia and Wirastuti 2009;

Sulandari 2008).

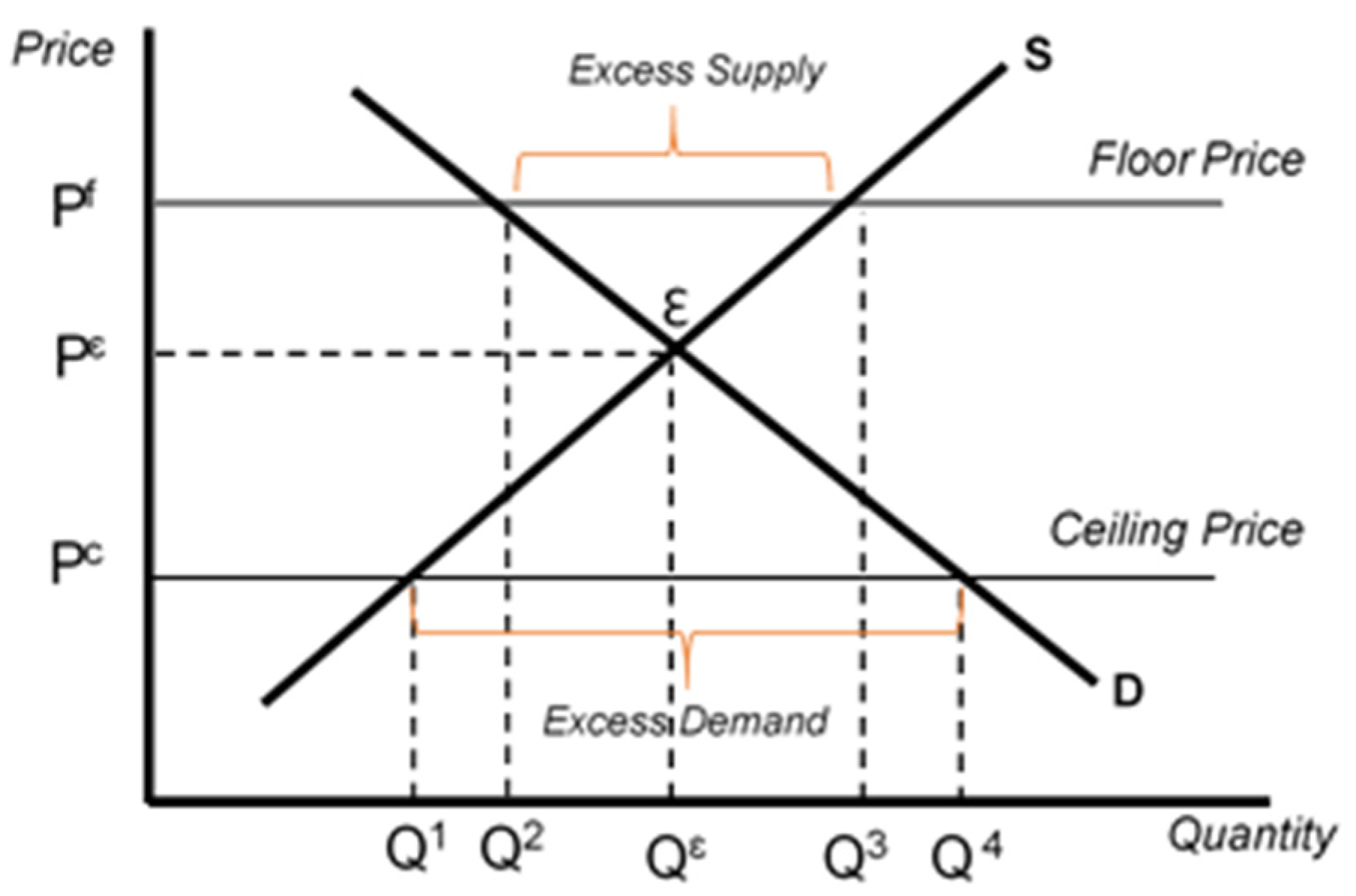

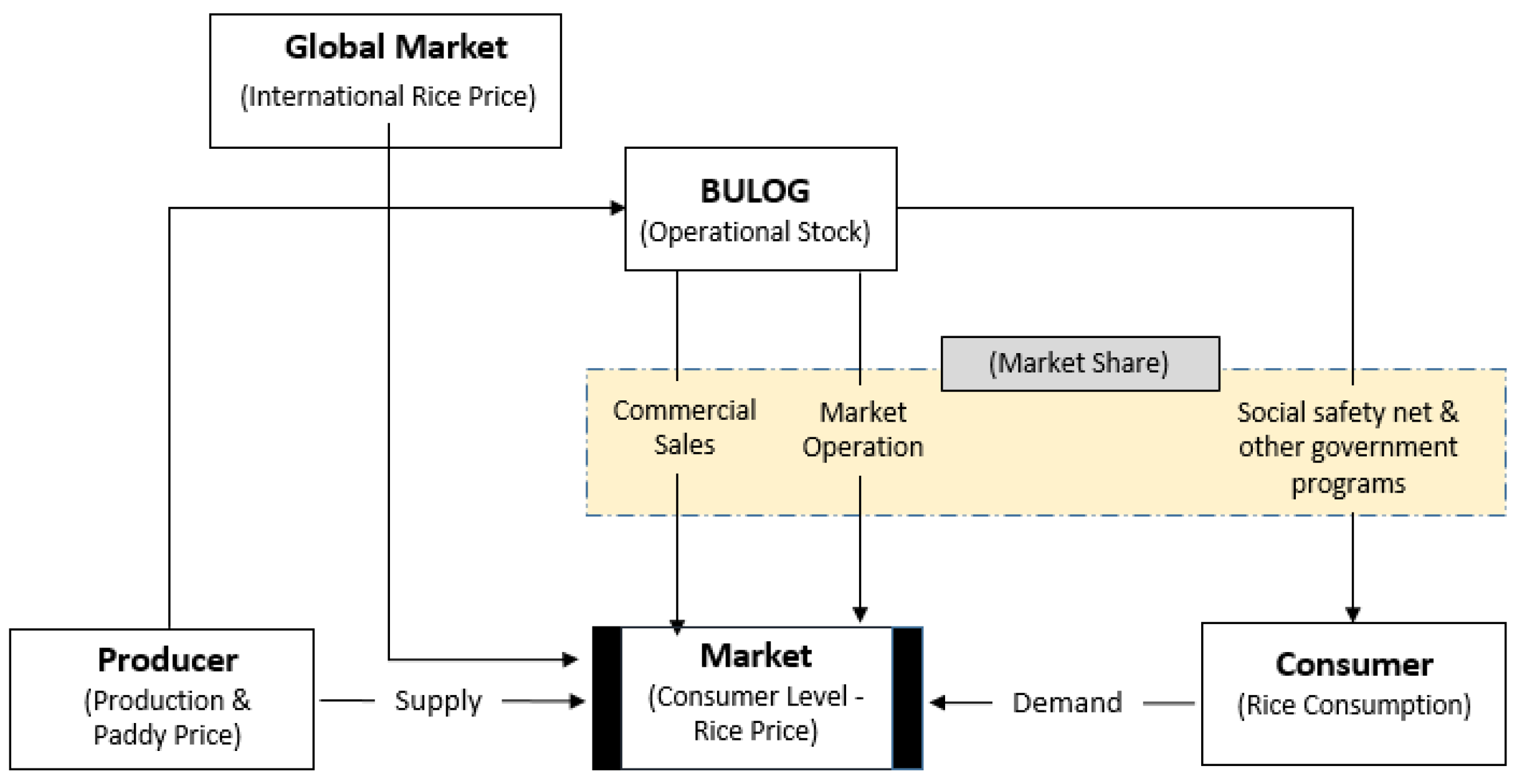

BULOG’s market share has been shown to have a negative effect on consumer-level rice prices in the same month and has a negative effect on consumer-level rice prices in the long run. This shows that BULOG’s operational activities, which are business and public assignments, have a negative effect on consumer-level rice prices, meaning that the larger BULOG’s market share, the more prices will tend to fall.

BULOG’s market share in this study is calculated from BULOG’s business volume, which consists of commercial sales and the realization of distribution of public assignments divided by the number of rice consumed. Distribution of public assignments consists of the realization of continuous market operation, distribution of food aid, and other government programs, whose sales prices contain government subsidies so that they are cheaper than market prices. Meanwhile, BULOG commercial rice is sold for a maximum price of the highest retail price (HET) set by the government.

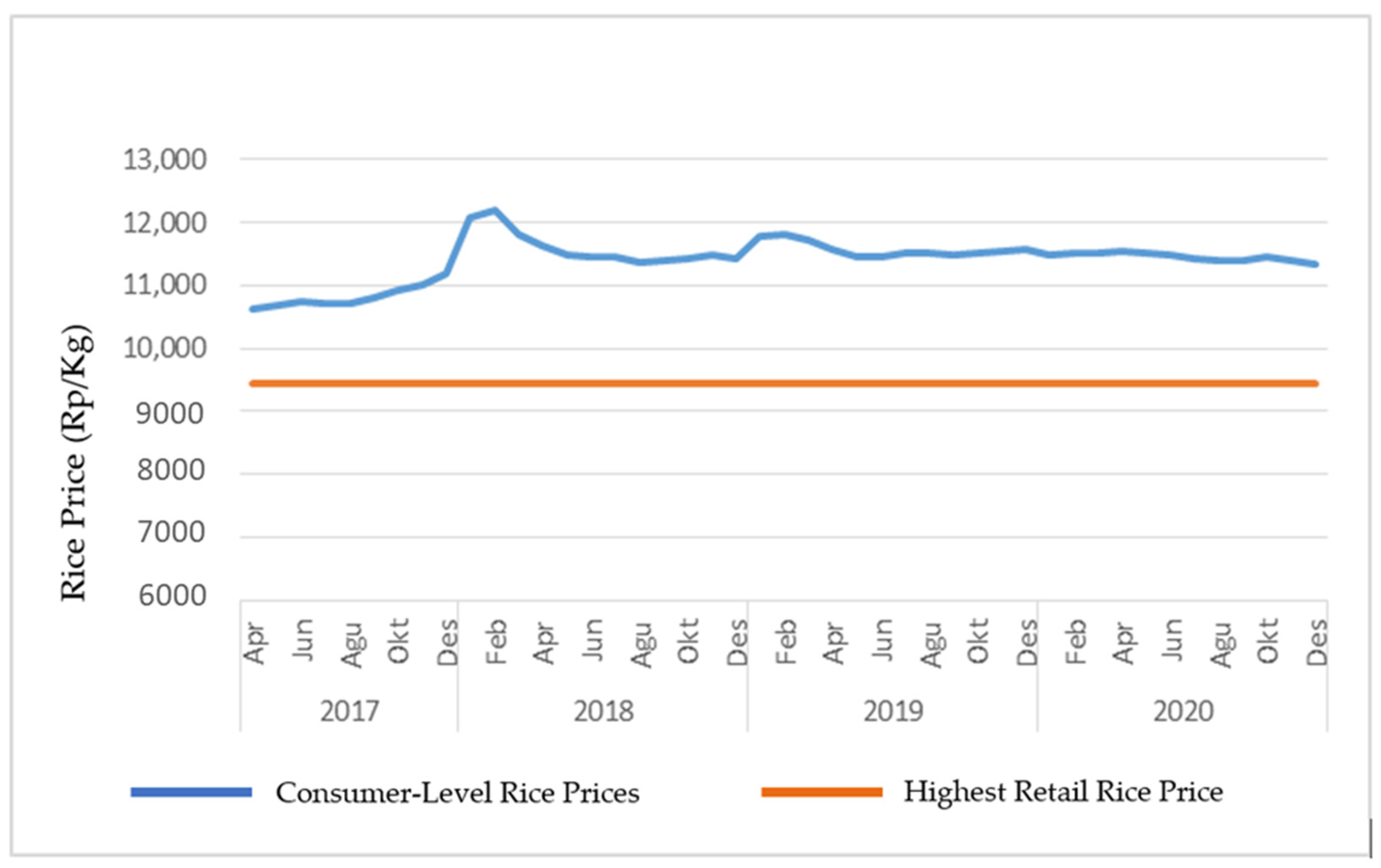

This is predicted to be the cause of the negative influence of the BULOG market share variable on consumer rice prices (the bigger the market share, the lower the rice price). This is relevant because, according to the data in

Figure 8, the average consumer price of rice in Indonesia is still above the highest retail price, so large market penetration by BULOG at a price below or equal to highest retail price will be able to lower prices.

Based on this, it seems that efforts to control prices by increasing market share and making BUMN the market leader of the national strategic industry are relevant to be carried out as a complement to the price stabilization policy model through a stock management approach. The government can encourage BULOG to increase its market share by being more involved in the commercial rice industry so that at a certain point, with an adequate market share, BULOG can become the market leader. A business entity can be a price maker and influence and direct the market with its position as a market leader (

Kotler and Armstrong 2013).

4.2. Combination of Price Stabilization Policy

Stock management through a public policy approach still needs to be maintained following the mandate of the Indonesian Food Law. Given that Indonesia has the form of an archipelagic country and a high variation of nutrients, food production can only be carried out well in some areas, such as the islands of Java and NTB, as well as some areas on the islands of Sulawesi and Sumatra. The pattern of rice harvests, which are concentrated in certain months, and the limited storage infrastructure and capital strength of private business actors making efforts to maintain food availability over time, cannot be left entirely to the market mechanism. The government also needs to mitigate the risk of natural and non-natural disasters, as well as other important and urgent needs. Based on this, food policy in the form of stock management—keeping a certain number of stocks by the government, along with its derivative programs—is still very much needed (

Jamaludin 2022;

Saragih 2016;

Utomo 2020).

However, according to

Timmer (

2014), this stock management policy model requires a large budget and is often inefficient. Market operation policies as part of stock management are often considered less effective and distort the market. The results of research by

Firdaus et al. (

2019),

Aryani (

2021) concluded that market operation policies have a significant but not impactful effect because the coefficient of the analysis result does not follow the expected sign, whereas the coefficient of the analysis results shows a positive value, which means that the greater the market operation, the higher the price.

Government-purchasing price management policies often cannot be implemented properly because government purchasing prices are often lower than market prices, so BULOG cannot absorb farmers’ rice harvests, lacks stock, and would be ultimately forced to import. Thus, there is an assumption that BULOG has “lost competition” with private rice traders (

Arifin 2020). BULOG’s ability to manage rice stocks can influence market psychology and the actions of market traders.

Therefore, as a complement to the stock management through a public policy approach model and its derivative programs that still exist with all their current limitations, the government can facilitate and encourage BULOG to take a bigger share of the food industry market as a national strategic industry. This is following the constitution, which mandates state control in the national strategic sector, and is in accordance with the government’s mandate that BULOG is able to develop its role in the food industry, especially rice, to realize the ideals of national food security, including the realization of a stable rice market.

BULOG as a business entity in the food sector, can be facilitated and encouraged to continue to develop its business programs such as cultivation/on-farm, revitalizing rice processing infrastructure, modernizing storage warehouses, increasing transportation modes for distribution efficiency, developing retail networks, and implementing information technology on the basis of enterprise resource planning (ERP). With efficient industrial practices, SOEs can realize economies of scale and deliver quality products at competitive prices.

BULOG as a state-owned business entity, with its goodwill, can balance and prevent the speculative behaviour of market traders so that they can provide a fair price in the market. The strategy of branding and downstream agricultural products can increase added value, thereby increasing farmers’ standard of living. BULOG can foster agricultural corporatization, create rice estates/industrial-scale rice cultivation, foster farmers and farmer cooperatives on a business basis to maintain productivity and production quality, build product differentiation and value, produce quality rice for various market segments, and provide other value-added programs so that farmers get better economic benefits.

BULOG can encourage data digitization programs at the supply chain nodes of the rice industry, from cultivation, processing, storage, and distribution to retail trade (

Alfazah et al. 2019), so that in the future, rice stock data as a food policy consideration will no longer be limited to stocks owned by BULOG but also applies to all public stocks recorded in the system at all supply chain nodes controlled by BULOG.

Market intervention activities in the future will be much easier without opening an outlet in the market, which often brings crowds and is unsafe. Market operations can be carried out by changing the price tag in the point of sale (POS) system of BULOG retailers by including subsidies provided by the government in the form of discounts. This model is much more transparent and can be accounted for because it already uses an integrated IT system.

SOEs can also become the foundation of the state to access sources of food availability abroad, increase export opportunities, invest in cultivation with high-tech processing abroad, as well as other forms of control of global assets for the benefit of the state. SOEs can also offset the expansion of foreign business entities, which are currently very aggressive in financing business sectors in the food sector, by taking over shares of Indonesian food start-up companies.