Abstract

Identifying instruments in polyphonic audio is challenging due to overlapping spectra and variations in timbre and playing styles. This task is central to music information retrieval, with applications in transcription, recommendation, and indexing. We propose a dual-branch Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) that processes Mel-spectrograms and binary pitch masks, fused through a cross-attention mechanism to emphasize pitch-salient regions. On the IRMAS dataset, the model achieves competitive performance with state-of-the-art methods, reaching a micro F1 of 0.64 and a macro F1 of 0.57 with only 0.878M parameters. Ablation studies and t-SNE analyses further highlight the benefits of cross-modal attention for robust predominant instrument recognition.

1. Introduction

One of the fundamental tasks in the field of Music Information Retrieval (MIR) is identifying the most prominent musical instruments from polyphonic audio. This task has significant implications for both academic research and practical applications. Since several instruments create overlapping spectral information in polyphonic recordings, it is intrinsically challenging to distinguish and isolate the dominant instrument playing at any given moment. For tasks like source separation, music tagging, intelligent music recommendation systems, automated music transcription, and audio-based content indexing, accurate identification of these predominant instruments is essential [1]. The current state of digital music collections, music education platforms, and real-time audio processing systems for broadcast or live performances makes these applications very pertinent.

The capability of leading instrument recognition to improve the semantic comprehension of intricate audio scenarios is one of its main benefits. Knowing the lead instrument, for instance, can assist music recommendation systems in effectively classifying genres or personalizing playlists to user preferences for particular timbres. Accurately identifying the lead instrument in computerized music transcription facilitates precise pitch and rhythm extraction, which is necessary for score creation.

Predominant instrument classification in polyphonic contexts is still a very difficult problem in spite of these benefits. The main challenge is the spectrum overlap between instruments, which makes it more difficult to tell them apart. Furthermore, a considerable degree of intra-class variance and inter-class similarity is introduced by the variety of playing styles, dynamic ranges, timbral expressions, and recording settings. Particularly in situations where there is little distinction between lead and background instruments, these elements add to problems with classification.

Handcrafted audio features like spectral roll-off, zero-crossing rates, and Mel-frequency cepstral coefficients (MFCCs) have been used in traditional machine learning algorithms to try to solve this problem. Although such features offer a concise depiction of the signal, they frequently fail to capture temporal connection and higher-level abstractions that are essential for determining the dominant source in a polyphonic mix. Because it can acquire discriminative characteristics from raw or altered audio representations, like Mel-spectrograms, deep learning and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) in particular, have become a potent substitute. These models achieve state-of-the-art results in related tasks such as music genre categorization, sound event detection, and speech recognition because they are excellent at identifying local patterns and hierarchical structures in audio data. Beyond audio, recent work has also shown that CNN-based AI pipelines can accurately classify complex sensor signals, highlighting the robustness and cross-domain effectiveness of deep learning for signal, image analysis classification, and pattern recognition [2].

We propose a dual-branch CNN framework that concurrently processes binary pitch masks produced from predominant pitch estimation and Mel-spectrograms in order to further improve recognition performance in polyphonic music. The model can selectively focus on pitch-salient areas of the audio by successfully fusing these complementary modalities through the application of a cross-attention mechanism. This architecture boosts generalization across variable-length inputs and a variety of musical contexts in addition to improving the model’s ability to isolate the dominant instrument. By bridging the gap between deep representation learning and pitch-aware preprocessing, our method seeks to improve the accuracy and robustness of predominant instrument recognition in polyphonic contexts.

2. Related Work

The task of identifying predominant instruments in polyphonic music has undergone significant evolution, with numerous methods proposed to address the complexity of overlapping spectral content in real-world recordings. Early studies, such as that by Kitahara et al. [3], emphasized the importance of combining diverse acoustic descriptors—including spectral, temporal, and modulation features—along with dimensionality reduction using principal component analysis (PCA), to improve classification outcomes. Fuhrmann et al. [4] advanced this approach by employing support vector machines (SVMs) trained on handcrafted features, whereas Bosch et al. [5] introduced source separation as a pre-processing strategy to isolate instrument components before classification.

Subsequent efforts explored various deep learning paradigms for modeling timbral characteristics more effectively. Han et al. [6] implemented a convolutional neural network (CNN) over mel-spectrogram inputs with temporal aggregation using sliding windows. This concept was refined by Pons et al. [7], who optimized the CNN architecture to better capture timbral nuances across time. Gururani et al. [1] incorporated temporal max-pooling in a deep neural network (DNN) to improve temporal feature abstraction, while Yu et al. [8] enhanced recognition through multitask learning with auxiliary outputs to improve model generalization across similar instrument classes.

The effectiveness of pre-processing strategies has also been explored in recent literature. Gomez et al. [9] demonstrated that integrating source separation and transfer learning substantially boosts classification accuracy, especially in low-data regimes. Additionally, Soraghan et al. [10] utilized the Hilbert-Huang Transform (HHT) in conjunction with CNNs to extract informative time-frequency features. Kratimenos et al. [11] trained VGG-style CNNs on augmented versions of the IRMAS dataset to mitigate class imbalance and enhance model robustness. In a similar direction, Lekshmi et al. [12] employed both mel-spectrogram and phase-based modgdgram representations, using WaveGAN for audio data augmentation. Their extended work explored multiple transformer variants and ensemble strategies with different time-frequency inputs such as mel-spectrograms, tempograms, and modgdgrams [13]. These efforts have collectively demonstrated that both feature engineering and deep learning can be leveraged for improved recognition accuracy.

Nevertheless, several challenges persist. Many state-of-the-art (SOTA) models depend on frame-level predictions and subsequent aggregation, as seen in [6,7], which introduces additional computational cost and latency. Deep neural network-based approaches [10,11] often lack flexibility when handling audio sequences of varying lengths. Furthermore, methods incorporating explicit source separation [5,9] improve performance at the cost of added preprocessing and model complexity. Despite these advancements, existing methods often depend on frame-wise predictions with sliding window aggregation [6,7], which increases computational load and introduces latency during inference. Deep neural architectures [10,11] typically exhibit high complexity and limited adaptability to variable-length audio sequences. Moreover, performance-enhancing pre-processing steps such as source separation [5,9] come at the cost of additional computation and system design complexity. Recent studies have also highlighted how CNN-based architectures may exhibit strong dataset dependency, affecting their generalization across diverse data domains [14].

To overcome these challenges, we propose a dual-branch hybrid architecture that integrates a Mel-spectrogram-based CNN and a binary mask-based CNN, fused via a cross-attention mechanism. The mel branch captures spectral-temporal dynamics through double convolutional blocks, while the binary mask branch emphasizes pitch-focused regions, aiding in discriminating overlapping instruments. The cross-attention module facilitates fine-grained interaction between both feature spaces, enabling the model to attend to instrument-specific timbral cues more effectively. Huang & Xie et al. [15] proposed a CNN–GRU fusion model for acoustic scene classification that harnesses cross-attention to integrate temporal and spectral features. Lee et al. [16] present a Cross Attention Network (CAN) for multimodal speech emotion recognition. Their model aligns audio and text features and fuses them through cross-attention, significantly improving emotion detection accuracy.

3. System Description

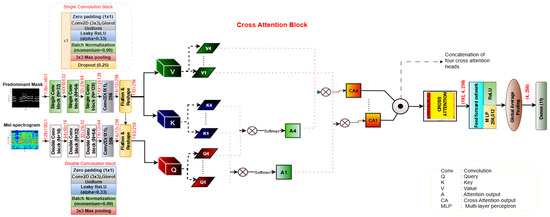

The block diagram of the proposed method of predominant instrument recognition is illustrated in Figure 1. The proposed model employs a dual-branch CNN architecture that separately encodes mel-spectrogram and predominant pitch mask inputs through dedicated convolutional pipelines. The mel-spectrogram branch consists of a series of double convolutional blocks, while the mask branch uses single convolutional blocks to extract robust pitch-specific features. Both branches generate flattened feature maps which serve as the Query (Q), Key (K), and Value (V) inputs to a four-head cross-attention module. The attention mechanism enables the model to fuse modality-specific features dynamically, enhancing inter-modal dependencies. The concatenated outputs from all heads are processed through a feed-forward MLP, followed by global average pooling and a final dense layer for 11-class instrument classification. This design enables the model to leverage complementary spectral and pitch cues for improved recognition in polyphonic audio. The detailed steps are explained in the subsections below.

Figure 1.

Block diagram of the proposed method of predominant instrument recognition using cross-attention.

3.1. Dataset and Preprocessing

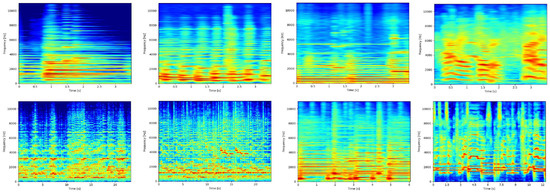

This study utilizes the IRMAS (Instrument Recognition in Musical Audio Signals) dataset [4,5], a well-established benchmark for evaluating automatic recognition systems for musical instruments in polyphonic environments. The dataset includes a total of 6705 training samples, each comprising a 3-s musical excerpt, and 2874 test samples that range in length from 5 to 20 s. These audio clips represent 11 pitched instrument categories cello, clarinet, flute, acoustic guitar, electric guitar, organ, piano, saxophone, trumpet, violin, and singing voice as shown in Table 1. Sample Mel-spectrogram illustrations for selected instrument classes are included in Figure 2 to demonstrate typical spectral patterns observed in the IRMAS dataset.

Table 1.

Summary of the musical instruments used in this study along with their abbreviations and the number of labeled training and testing audio samples.

Figure 2.

Sample Mel-spectrogram illustrations of acousticguitar, flute, organandvoice audiofiles from trainingset (upper pane) and corresponding audiofiles from testset (lower pane).

For preprocessing, each audio file is loaded at a fixed sampling rate of 44.1 kHz using the librosa Ver. 0.11.0 Python library. This sampling rate ensures that essential acoustic and harmonic cues are retained, which are critical for both pitch tracking and timbre-based classification. The IRMAS dataset is organized into class-specific folders, labeled from “0” to “10,” with each folder corresponding to a specific instrument class. This structure supports consistent labeling and efficient traversal during batch processing.

Each audio file undergoes a structured preprocessing routine. The extracted features include the Mel-spectrogram, a binary pitch-based mask, and a masked spectrogram. These features, along with the corresponding ground truth class label, are serialized and stored as .pt (PyTorch tensor) files. The use of serialized tensors not only optimizes storage but also accelerates data loading during training. These .pt files are saved in separate folders per class, enabling straightforward retrieval and robust data handling.

3.2. Feature Extraction

To capture both the spectral distribution and melodic focus of the input audio, two complementary features are extracted: the Mel-spectrogram and a binary time-frequency mask derived from pitch information. These representations provide distinct yet synergistic perspectives of the musical signal.

3.2.1. Mel-Spectrogram

The Mel-spectrogram is a time-frequency representation that aligns with the human auditory scale, making it highly suitable for audio classification tasks. The audio waveform is transformed into a time-frequency representation by applying the Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT) with a window length of 50 ms and a hop length of 10 ms. At a sampling rate of 44.1 kHz, these settings correspond to 2205 samples per window and 441 samples between consecutive windows. For a 3-second audio segment, this configuration produces around 100 time frames. Subsequently, the linear-frequency spectrogram obtained from the STFT is converted into a Mel-spectrogram using 128 Mel filter banks. This conversion results in a Mel-spectrogram with dimensions 128 × 100 × 1, which better reflects human perceptual sensitivity to loudness variations. This representation captures rich harmonic and temporal patterns, facilitating the learning of pitch-related and timbral features by the model. It serves as the main input to the spectral analysis branch of the network, supporting the learning of spatially localized and hierarchically abstracted features.

3.2.2. Binary Pitch-Based Mask

In parallel with spectral extraction, we compute a binary mask to highlight regions of the spectrogram associated with the predominant pitch. This mask is generated using the pyin algorithm from the librosa package, which estimates the fundamental frequency (F0) of the audio signal frame-by-frame within the pitch range of approximately 65 Hz (C2) to 2093 Hz (C7).

For each time frame where a voiced pitch is detected, the corresponding Mel bin is identified and marked as active (value 1), while all other bins are assigned a value of 0. This produces a sparse, binary time-frequency map that emphasizes harmonic content associated with the dominant melodic line, effectively reducing the influence of background instruments and noise.

To enhance the robustness of the model against pitch estimation errors and over-sensitivity to perfect F0 detection, controlled Gaussian noise is added to the binary mask during training. This augmentation encourages the network to generalize better by learning invariant representations even when the pitch-based mask contains minor inaccuracies from the pyin algorithm.

3.2.3. Predominant Spectrogram Generation

To focus on pitch-relevant spectral regions, an element-wise multiplication is performed between the binary mask and the Mel-spectrogram in the dB domain. This operation yields a masked spectrogram that selectively retains energy in regions tied to the estimated predominant pitch. By emphasizing musically salient structures, this representation allows the network to focus on tonally dominant features during training.

3.2.4. Feature Packaging

Each processed sample is saved in a structured .pt file containing four components:

- mel: the full Mel-spectrogram in dB scale, stored as a tensor of shape

- mask: the binary mask aligned with the Mel-spectrogram, stored as a tensor of shape

- pred_spec: the masked (predominant) spectrogram obtained by element-wise multiplication of mel and mask, with shape

- label: the ground truth instrument class label, stored as an integer scalar

These tensor files enable modular use of individual features and support experiments involving single-modality, multi-modality, or attention-driven fusion strategies. The .pt format also ensures efficient I/O during training, allowing the system to scale effectively to large datasets.

4. Methodology

This section describes the process for creating binary masks from the most important pitch information, extracting pertinent audio features, and designing a dual-branch convolutional neural network (CNN) architecture with cross-attention fusion for the categorization of musical instruments.

4.1. Feature Extraction and Data Presentation

The main resource used for model evaluation and training is the IRMAS dataset. A short-time Fourier transform (STFT) with a frame size of 50 ms and a hop size of 10 ms is used to process each 3-s audio sample. After that, the linear spectrogram is converted to the decibel (dB) scale and then utilizing 128 Mel-frequency bins to convert it to the Mel scale.

Each sample is saved as a structured .pt file. This file includes the Mel-spectrogram, a binary mask indicating predominant pitch regions, the element-wise product of the spectrogram and the mask (representing the predominant spectral regions), and the corresponding ground truth label. All tensor components are formatted as , representing one input channel, 128 frequency bins, and 100 temporal frames.

4.2. Dual-Branch CNN Architecture with Cross-Attention Fusion

To jointly exploit spectral and pitch information, we design a dual-branch CNN architecture where two independent encoders process the Mel-spectrogram and the corresponding binary pitch mask. The resulting latent features are then fused through a cross-attention module that promotes interaction between the two modalities. This module enables bidirectional information flow, allowing the spectral branch to refine its representation using pitch cues and vice versa, while maintaining linear computational complexity [17].

In contrast to self-attention, which models contextual relations within a single feature domain, the proposed cross-attention mechanism focuses on capturing inter-modal dependencies. It allows one feature stream to act as a query and attend selectively to the most informative components of the other (key–value pair), thereby enhancing feature complementarity. Unlike typical multimodal attention approaches that depend on concatenation or co-attention strategies, our fusion method dynamically emphasizes pitch-relevant spectral regions and attenuates redundant or noisy patterns. This selective information exchange strengthens the model’s ability to distinguish instruments with overlapping harmonic structures, leading to more robust recognition in polyphonic conditions.

4.2.1. Mel-Spectrogram CNN Branch

The Mel-spectrogram branch is constructed using a sequence of three double convolution blocks. Each double convolution block consists of zero-padding to preserve spatial dimensions, followed by a convolutional layer activated with Leaky ReLU (). Leaky ReLU ensures that non-active neurons during training still maintain a small gradient, preventing dead neuron issues. Batch normalization is applied after each activation to normalize the feature maps, promoting stable and accelerated convergence. A second convolutional layer with identical activation and normalization follows, culminating in a max-pooling operation to progressively reduce spatial resolution while increasing the receptive field. The network uses a filter progression of 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256 to extract increasingly abstract spectral representations.

4.2.2. Cross-Attention Fusion

After feature extraction from both branches, the resulting tensors are projected into a unified 512-dimensional feature space using convolutional layers. The projected tensors are then reshaped into sequences, with the Mel-spectrogram features serving as queries and the binary mask features as keys and values. A multi-head attention mechanism with four heads is applied to capture contextual dependencies between spectral and pitch-based representations.

Mathematically, let and denote the feature embeddings from the Mel-spectrogram and binary mask branches, respectively. The cross-attention process is defined as [17]:

where , , and are learnable projection matrices. The attention weights are computed as:

and the fused representation is obtained by:

This operation enables the spectral features to focus on pitch-salient regions, reinforcing inter-modal dependencies and improving discriminative learning. The attention-enhanced output from all four heads is concatenated and passed through a feed-forward network with ReLU activation, followed by global average pooling to obtain a compact, modality-fused representation. This vector is then forwarded to the classification layer for instrument prediction.

4.2.3. Classification Head

The final representation is passed through a fully connected classification head. It consists of a linear layer projecting from 512 to 1024 dimensions, followed by ReLU activation and dropout with a rate of 0.5. A final linear layer maps the features to 11 output classes corresponding to the instrument categories. The model summary of the proposed architecture is shown in Table 2. This hierarchical processing pipeline allows the model to dynamically prioritize salient pitch-informed spectral regions, improving robustness and accuracy in instrument classification.

Table 2.

Detailed Layer-wise Architecture of Cross-Attention Model.

5. Performance Evaluation

We employed the IRMAS dataset, which comprises 1305 polyphonic audio samples annotated with a single predominant instrument label across 11 pitched classes as shown in Table 2. To validate model performance and reduce overfitting, 20% of the training data was reserved for validation. For a more realistic evaluation, we used the polyphonic test set consisting of 2874 audio clips with variable durations ranging from 5 to 20 s.

5.1. Training Strategy

The models are trained and evaluated in a uniform setting to ensure a fair comparison between the proposed dual-branch cross-attention network and the baseline variants. Each audio instance is saved as a .pt file that includes the Mel-spectrogram, the binary pitch mask (), and the corresponding instrument label. The dataset is divided into an 80:20 split for training and validation.

All experiments are run for 100 epochs with a batch size of 16, using categorical cross-entropy as the loss function. Adam with a learning rate of is adopted as the main optimizer, as it consistently showed stable behaviour during training. Other optimizers such as SGD, RMSProp, RAdam, and Lookahead were also tested, but they did not offer noticeable improvements as expected. The entire training pipeline is executed on Google Colab with GPU support (CUDA), which helps reduce computation time and enables multiple experimental runs.

5.2. Experimental Configuration and Evaluation Protocol

Performance is evaluated using precision, recall, and F1-scores with both micro and macro averaging. Micro-averaged metrics aggregate across all classes, while macro-averaging assigns equal weight to each class, addressing class imbalance.

The experimental framework compares four configurations: (1) MelCNN-only (spectrogram input), (2) MaskCNN-only (binary mask input), (3) Mel + Mask CNN with direct concatenation (no attention), and (4) the proposed cross-attention fusion model.

This ablation study highlights the performance gains achieved through cross-modal attention. Additionally, we benchmark against the state-of-the-art Han model and traditional classifiers (DNN, SVM) trained on handcrafted features (MFCC-13, spectral centroid, bandwidth, RMS, roll-off, and chroma-STFT) extracted via librosa. This ensures a comprehensive comparison with both deep learning and classical approaches.

6. Results and Analysis

Table 3 presents a comparative performance analysis across different model architectures, including the baseline Han model, MelCNN-only, MaskCNN-only, and the proposed cross-attention framework. It is observed that the cross-attention model consistently achieves higher precision, recall, and F1-scores across most instrument classes. The micro and macro average F1-scores of 0.79 and 0.73, respectively, indicate that the model performs effectively across both balanced and imbalanced class distributions. Particularly, instruments such as the violin, electric guitar, and clarinet, which are often challenging due to overlapping frequencies, show marked improvements. For instance, the violin achieves an F1-score of 0.83 in the cross-attention model, a noticeable gain compared to 0.66 in the MelCNN configuration. This suggests that integrating pitch and spectral cues enables more reliable recognition in polyphonic contexts.

Table 3.

Precision (P), Recall (R), and F1 Score for All Experiments.

Furthermore, the cross-attention model shows improved generalization across low-sample-count classes, like saxophone and trumpet, where recall values improve without sacrificing accuracy. The cross-attention model enhances the saxophone recall from 0.60 in the baseline models to 0.70, which is particularly important for instruments that are prone to misclassification. The fusion process in the cross-attention setup works better for learning discriminative representations, even if the MelCNN and MaskCNN variants provide competitive outcomes separately, favoring either spectral or pitch-related characteristics. In a variety of acoustic settings, the overall performance improvements demonstrate the advantages of dynamic interaction across feature branches, which reduces ambiguities and promotes reliable instrument recognition.

6.1. t-SNE Visualization Analysis

To investigate the quality of learned feature representations, we utilize t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) to visualize the embeddings of two model variants—Cross-Attention and Concatenation—at training epochs 20, 40, 60, 80, 100, and 120. Each point corresponds to an input sample, and colors indicate the 11 instrument classes. The Cross-Attention Model progressively forms compact and well-separated clusters across epochs, especially for instruments like gac (acoustic guitar), pia (piano), and voi (voice), indicating improved intra-class cohesion and inter-class separability.

In contrast, the Concatenation Model Without Attention shows scattered and overlapping embeddings with minimal cluster structure throughout training. Instruments such as cel (cello), cla (clarinet), and tru (trumpet) remain poorly separated, even at later epochs. This is mainly because of less number of training files available for these classes. These observations highlight the advantage of cross-attention, which effectively fuses spectral and pitch information, enabling the model to learn more discriminative and semantically meaningful representations. The visual results, as depicted in Figure 3, support the superior clustering behavior of the attention-based model.

Figure 3.

t-SNE visualization of embeddings from Cross-Attention and Concatenation models at epochs 20, 40, 60, 80, 100, and 120. The cross-attention model shows more compact and separable clusters.

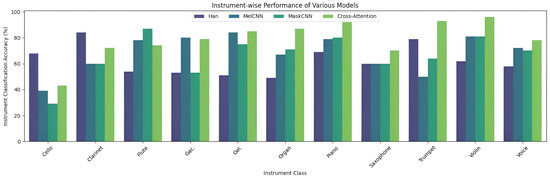

6.2. Instrument Wise Performance

The instrument-wise classification accuracy shown in Figure 4 highlights the relative strengths and weaknesses of the four evaluated models—Han, MelCNN, MaskCNN, and Cross-Attention. The Han model showed limited effectiveness across most instrument classes, particularly struggling with Cello and Saxophone due to overlapping frequency content and a smaller number of training samples. MelCNN improved upon this by leveraging timbral features from Mel-spectrograms, yet it still faced challenges with instruments that exhibit subtle pitch variations. MaskCNN, focusing on pitch-related masks, showed improved accuracy for instruments like Flute and Voice, which have clearer pitch contours. Among all, the Cross-Attention model consistently delivered the highest classification accuracy across nearly every instrument class. It effectively integrated both timbral and pitch-based cues, leading to better generalization for complex instruments such as Violin, Trumpet, and Organ. This confirms the advantage of the proposed cross-modal fusion strategy, especially in polyphonic environments where distinguishing between instruments is inherently difficult.

Figure 4.

Instrument-wise performance of various models.

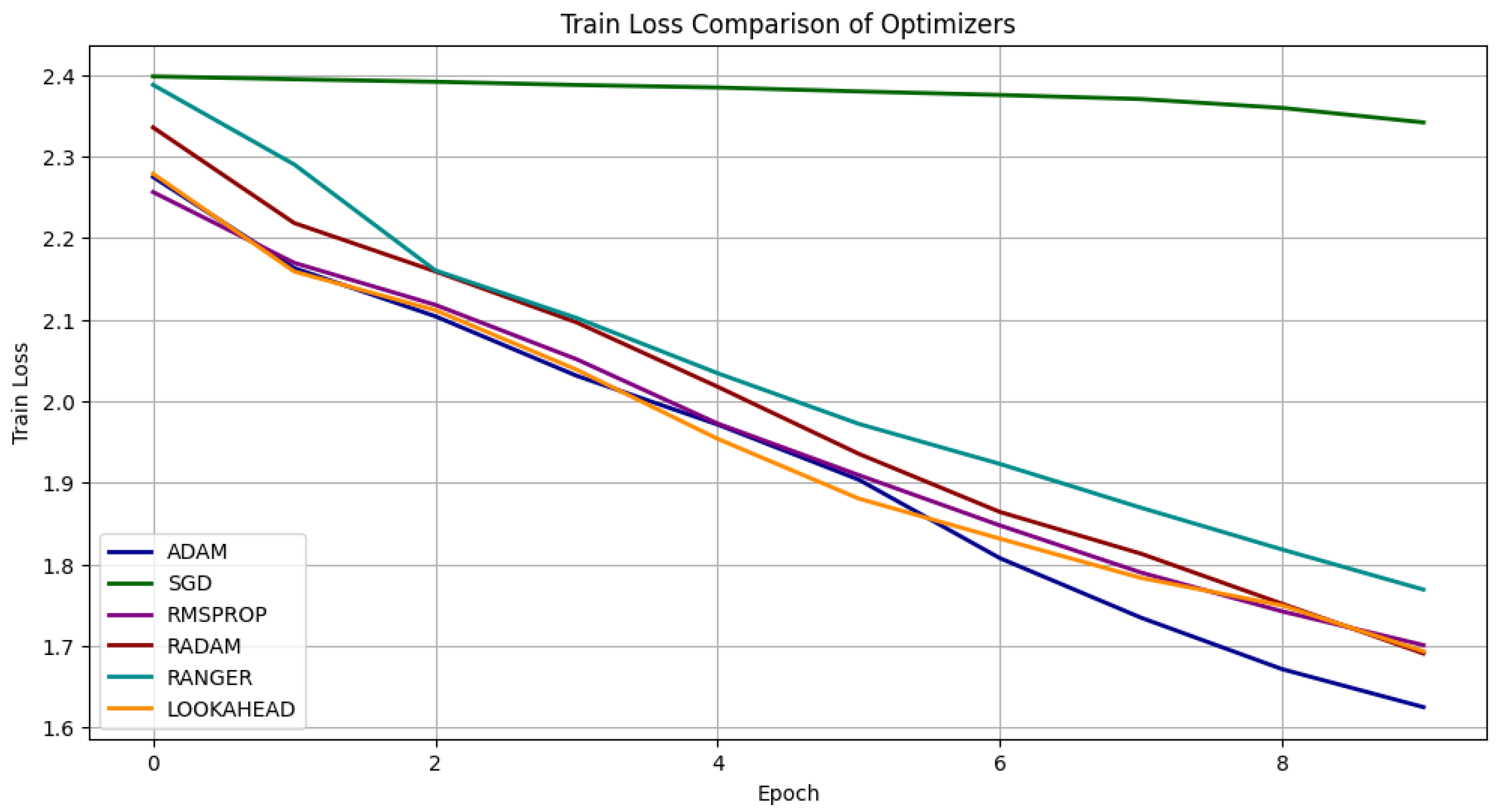

6.3. Optimizer Comparison

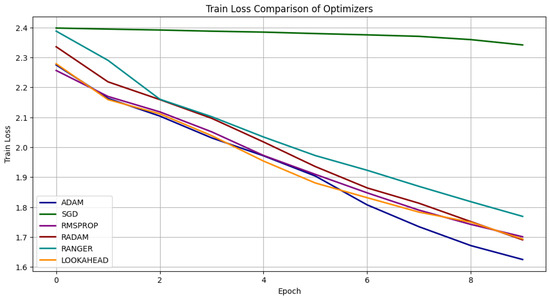

We compared six optimizers—Adam, SGD, RMSProp, RAdam, Ranger, and Lookahead—to examine their early convergence behavior, as shown in Figure 5. The loss curves over the first 10 epochs reveal that Adam provides the fastest and most stable reduction in loss, consistently reaching the lowest value. This reflects its effective combination of adaptive learning rates and momentum.

Figure 5.

Comparison of various optimizers.

SGD showed minimal improvement, indicating poor suitability for this task. RMSProp, RAdam, Ranger, and Lookahead exhibited moderate performance: Ranger initially decreased the loss quickly but plateaued early, while RAdam and Lookahead produced smoother curves but required more training to match Adam. Overall, Adam remains the most dependable choice for rapid and stable convergence within shorter training schedules.

6.4. Ablation Analysis

The ablation study provides valuable insights into the contributions of different components within the proposed architecture. As shown in Table 4, the MelCNN-only and MaskCNN-only models perform reasonably well individually, demonstrating that both spectral and pitch-based representations carry significant discriminative information. However, the relatively lower macro F1 score of the MaskCNN-only model suggests that it is less effective in distinguishing across a wide variety of classes compared to MelCNN. The simple concatenation of Mel and Mask features (Mel + Mask Concat) leads to a modest performance improvement over the individual branches, indicating some level of complementary information.

Table 4.

Ablation Study: Micro and Macro F1 Scores of Different Model Variants.

With the highest micro and macro F1 scores, on the other hand, the suggested Cross-Attention model performs better, showing both good overall accuracy and balanced classification across all classes. The model gets to focus on the most instructive cues for every sample thanks to the attention mechanism, which permits dynamic feature weighting between modalities. The t-SNE plots, which show dense, well-separated clusters that imply more discriminative feature representations, lend further credence to this. The findings support the notion that intelligent feature fusion via attention is more important for efficient instrument categorization in polyphonic audio than static concatenation.

To further analyze the sensitivity of our model to pitch-mask quality, we conducted a controlled evaluation using two internally generated mask variants: (i) a noisy mask, produced directly from the raw pYIN output and therefore containing typical estimation errors such as octave jumps and spurious activations, and (ii) a clean mask, obtained by applying post-processing steps (median filtering, threshold smoothing, and removal of isolated activations) to reduce noise while preserving pitch-related structure. As shown in Table 5, the proposed model exhibits only a marginal performance increase when using the clean mask. This small difference demonstrates that the cross-attention module is inherently robust to pitch-tracking noise and does not rely on perfectly estimated masks to achieve strong performance.

Table 5.

Mask Quality Evaluation: Performance Comparison Using Noisy (pYIN) and Ground-Truth Masks.

6.5. Comparison with Existing Algorithms

Table 6 presents a comparative analysis of our proposed Cross-Attention model against several existing methods in the task of multiple predominant instrument recognition. Traditional approaches such as MTF-DNN [12] and MTF-SVM [18] show relatively low performance, with micro F1 scores of 0.32 and 0.25, respectively, highlighting the limitations of classical machine learning techniques in modeling complex polyphonic signals. Earlier deep learning models like those by Han [6] and Pons [7] improved the results to micro F1 scores of 0.60 and 0.59, respectively, demonstrating the effectiveness of CNNs in learning discriminative spectral patterns. Transformer-based architectures, such as ViT [13], Swin-T [13], further boosted performance, showcasing the benefit of compact attention-based models.

Table 6.

Comparison of Model s for Predominant Instrument Recognition.

The proposed Cross-Attention model outperforms most of the state-of-the-art models with a micro F1 score of 0.64 and a macro F1 of 0.57, despite having a relatively modest parameter count of 0.878M. and a 0.076, ms inference time. Compared to larger architectures such as Han et al. [6] and ViT [13], the model achieves superior Micro and Macro F1 scores while operating with fewer parameters and competitive latency. This indicates the model’s efficiency and its ability to effectively integrate spectral and pitch information using cross-modal attention. While transformer-based models benefit from global context, the proposed hybrid framework leverages localized feature extraction via CNNs and adaptive inter-modal fusion via cross-attention, yielding a robust and generalizable solution for instrument recognition in polyphonic music.

7. Conclusions and Future Work

In this study, we presented a dual-branch Convolutional Neural Network architecture enhanced with a cross-attention mechanism for predominant instrument recognition in polyphonic music. The proposed model effectively integrates Mel-spectrogram features and binary pitch-based masks, demonstrating improved discriminative capability through adaptive fusion of spectral and pitch-related information. Extensive experiments on the IRMAS dataset confirmed the superiority of our approach over several state-of-the-art models, both in terms of classification performance and parameter efficiency. The results were further validated using t-SNE visualizations and ablation studies, underscoring the advantages of cross-modal attention in enhancing instrument-wise feature separability.

In future work, we intend to enhance the current frame-level cross-attention fusion by incorporating temporal modeling so the network can better capture long-range musical structure. This will involve integrating Transformer blocks or recurrent layers on top of the existing architecture. We also plan to examine a bidirectional cross-attention mechanism, enabling both branches to exchange information instead of relying on the present one-way interaction. To reduce the impact of inaccuracies in the pYIN-derived pitch masks, we will explore uncertainty-aware masking strategies, including controlled perturbations and confidence-weighted attention. Beyond classification, the proposed framework can be adapted for broader MIR applications such as music transcription and source separation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.C.R., C.N. and C.R.; methodology, L.C.R. and C.N.; software, R.R.; investigation, L.C.R. and C.R.; resources, R.R.; data curation, R.R.; supervision, C.N. and C.R.; project administration, C.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

No participants were involved in this study. Hence, ethical approval, informed consent, and adherence to institutional or licensing regulations are not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available online https://www.upf.edu/web/mtg/irmas (accessed on 2 February 2019).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no potential conflict of interests.

Abbreviations

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| IRMAS | Instrument Recognition Musical Audio Signal |

| tSNE | t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding |

| MIR | Music Information Retrieval |

| MFCC | Mel- Frequency Cepstral Coefficients |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| DNN | Deep Neural Network |

| HHT | Hilbert Huang Transform |

| WaveGAN | Wave Generative Adversarial Networks |

| STFT | Short-Time Fourier 167 Transform |

| ReLU | Rectified Linear Unit |

| SGD | Stochastic Gradient Descent |

| RMSProp | Root Mean Square Propagation |

| Adam | Adaptive Moment Estimation |

| RAdam | Rectified Adam |

| MTF | Music Texture Features |

References

- Gururani, S.; Summers, C.; Lerch, A. Instrument activity detection in polyphonic music using deep neural networks. In Proceedings of the 19th International Society for Music Information Retrieval Conference (ISMIR), Paris, France, 23–27 September 2018; pp. 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallakonda, A.; Yanamala, R.M.R.; Raj, R.D.A.; Napoli, C.; Randieri, C. DPIBP: Dining Philosophers Problem-Inspired Binary Patterns for Facial Expression Recognition. Technologies 2025, 13, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitahara, T.; Goto, M.; Komatani, K.; Ogata, T.; Okuno, H.G. Instrument Identification in Polyphonic Music: Feature Weighting to Minimize Influence of Sound Overlaps. EURASIP J. Appl. Signal Process. 2007, 2007, 155–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuhrmann, F.; Herrera, P. Polyphonic instrument recognition for exploring semantic similarities in music. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Digital Audio Effects (DAFx-10), Graz, Austria, 6–10 September 2010; Volume 14. pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch, J.J.; Janer, J.; Fuhrmann, F.; Herrera, P. A comparison of sound segregation techniques for predominant instrument recognition in musical audio signals. In Proceedings of the 13th International Society for Music Information Retrieval Conference (ISMIR), Porto, Portugal, 8–12 October 2012; pp. 552–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Kim, J.; Lee, K. Deep Convolutional Neural Networks for Predominant Instrument Recognition in Polyphonic Music. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 2017, 25, 208–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons, J.; Slizovskaia, O.; Gong, R.; Gómez, E.; Serra, X. Timbre analysis of music audio signals with convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the 25th European Signal Processing Conference (EUSIPCO), Kos, Greece, 28 August–2 September 2017; pp. 2744–2748. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, D.; Duan, H.; Fang, J.; Zeng, B. Predominant Instrument Recognition Based on Deep Neural Network With Auxiliary Classification. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 2020, 28, 852–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Cañón, J.; Abeßer, J.; Cano, E. Jazz Solo Instrument Classification with Convolutional Neural Networks, Source Separation, and Transfer Learning. In Proceedings of the International Society for Music Information Retrieval Conference (ISMIR), Paris, France, 23–27 September2018; pp. 577–584. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Wang, K.; Soraghan, J.; Ren, J. Fusion of Hilbert-Huang Transform and Deep Convolutional Neural Network for Predominant Musical Instruments Recognition. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Music, Sound, Art and Design, Seville, Spain, 15–17 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kratimenos, A.; Avramidis, K.; Garoufis, C.; Zlatintsi, A.; Maragos, P. Augmentation methods on monophonic audio for instrument classification in polyphonic music. In Proceedings of the 2020 28th European Signal Processing Conference (EUSIPCO), Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 18–21 January 2021; pp. 156–160. [Google Scholar]

- Reghunath, L.C.; Rajan, R. Multiple Predominant Instruments Recognition in Polyphonic Music Using Spectro/Modgd-gram Fusion. Circuits Syst. Signal Process. 2023, 42, 3464–3484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekshmi, C.R.; Rajan, R. Compact Convolutional Transformers for Multiple Predominant Instrument Recognition in Polyphonic Music. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Communication and Electronics Systems (ICCES), Coimbatore, India, 16–18 December 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Olmo, P.V.; Kuznetsov, O.; Frontoni, E.; Arnesano, M.; Napoli, C.; Randieri, C. Dataset Dependency in CNN-Based Copy-Move Forgery Detection: A Multi-Dataset Comparative Analysis. Mach. Learn. Knowl. Extr. 2025, 7, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Xie, Y.; Jiang, P. Local Time-Frequency Feature Fusion Using Cross-Attention for Acoustic Scene Classification. Symmetry 2024, 17, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.; Byun, S.; Jung, K. Multimodal speech emotion recognition using audio and text. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Spoken Language Technology Workshop (SLT), Athens, Greece, 18–21 December 2018; pp. 112–118. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.F.R.; Fan, Q.; Panda, R. Crossvit: Cross-attention multi-scale vision transformer for image classification. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 357–366. [Google Scholar]

- Racharla, K.; Kumar, V.; Chaudhari Bhushan, J.; Khairkar, A.; Paturu, H. Predominant Musical Instrument Classification Based on Spectral Features. In Proceedings of the 2020 7th International Conference on Signal Processing and Integrated Networks (SPIN), Noida, India, 27–28 February 2020; pp. 617–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.