Transport and Application Layer Protocols for IoT: Comprehensive Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Context

2.1. Quick Taxonomy

2.2. Physical and Link Layer: Choices and Trade-Offs

2.2.1. Short-Range, Low-Power (Home/Building/Personal-Area)

2.2.2. Long-Range, Low-Rate (LPWAN)

2.2.3. Wi-Fi and 5G

2.3. Network and Adaptation: IP for Constrained Devices

2.4. Transport and Application Protocols—The Most Important Layer for Interoperability

2.4.1. MQTT (Message Queuing Telemetry Transport)

2.4.2. CoAP (Constrained Application Protocol)

2.4.3. MQTT-SN (MQTT for Sensor Networks)

2.4.4. OPC UA

2.5. Security: Practical Stack and Pitfalls

2.6. Practical Deployment Considerations and Performance Trade-Offs

2.6.1. Message Size and Fragmentation

2.6.2. Latency vs. Battery Life

2.6.3. Reliability and QoS Levels

2.6.4. Scalability and Multi-Tenant Cloud Integration

2.6.5. Interoperability

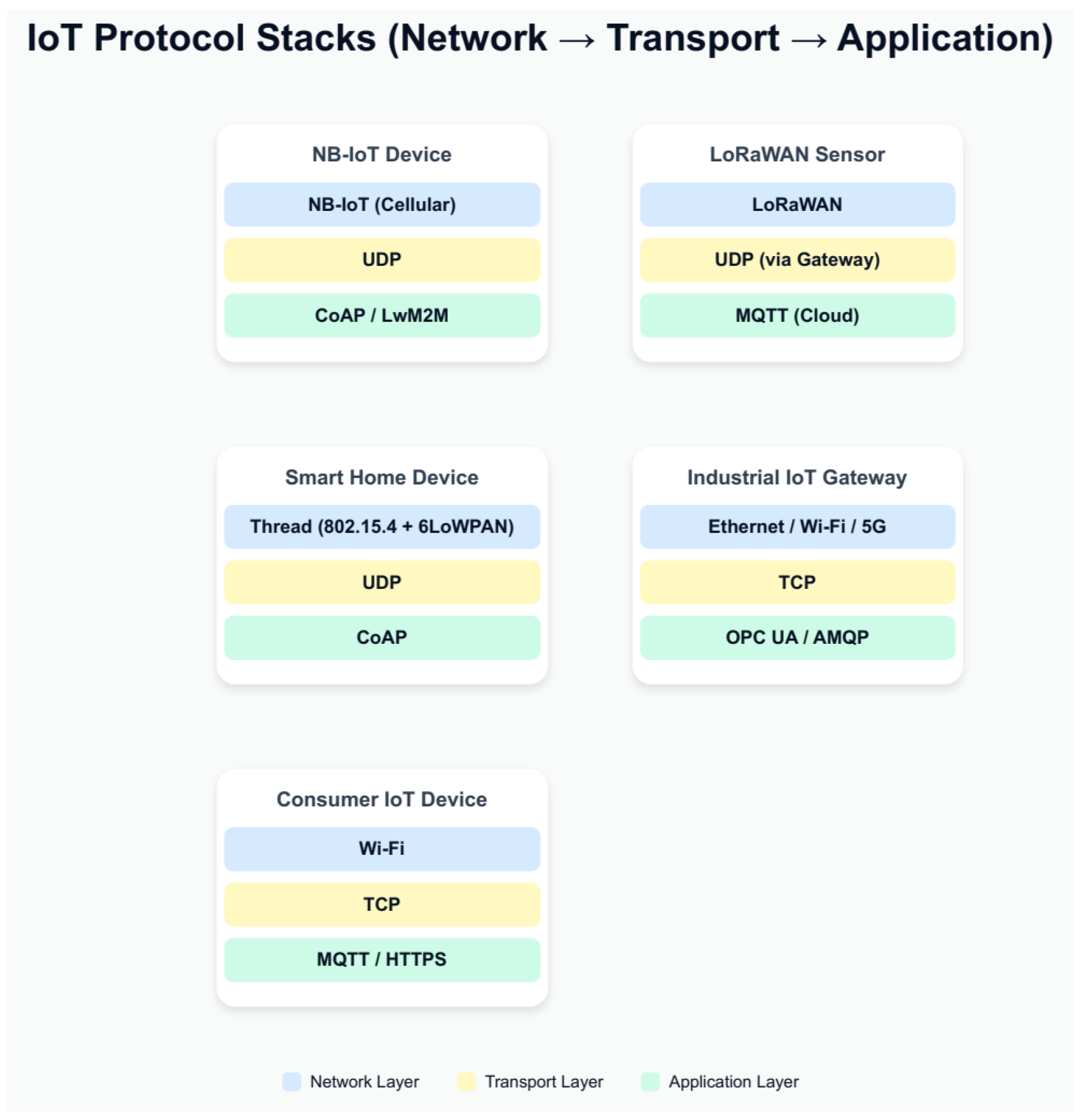

2.7. Typical Stacks and Recommended Choices (By Use Case)

2.7.1. Battery-Powered Sensors in a Wide Area (e.g., Agriculture, Asset Monitoring)

2.7.2. Home/Building Automation (Many Nodes, Mesh, IP)

2.7.3. Industrial IoT (Low Latency, Rich Models)

2.7.4. Smartphones/Consumer Devices Interacting with Cloud

2.8. Management, Provisioning, and Lifecycle

2.9. Interoperability and Gateways (Practical Notes)

2.10. Implementation and Testing Tools (Short List)

2.11. Key Standards and Readings (Authoritative Sources)—The Five Most Load-Bearing References I Used

2.12. Common Mistakes and Pitfalls

- Relying on default/unprotected devices or hardcoded passwords.

- Ignoring MTU/payload limits (LoRaWAN and IEEE 802.15.4) [20]

- Using TCP everywhere on extremely constrained radios (connection setup leads to rapid battery depletion).

- Designing for the “lab” radio environment, not the reality (penetration, multi-path, duty cycle limits).

3. Transport and Application Protocols

3.1. MQTT and MQTT-SN

3.1.1. Overview for MQTT and MQTT-SN

3.1.2. Communication Model for MQTT and MQTT-SN

3.1.3. Transport Layer for MQTT and MQTT-SN

3.1.4. Quality of Service (QoS)

3.1.5. Security for MQTT and MQTT-SN

3.1.6. Strengths for MQTT and MQTT-SN

- Low message overhead and minimal protocol complexity.

- Efficient for battery-powered devices and networks with variable connectivity.

- Scalable from small home deployments to enterprise-grade IoT platforms.

- Supports asynchronous and decoupled communication, making it ideal for distributed telemetry and event-driven architectures.

3.1.7. Limitations for MQTT and MQTT-SN

- MQTT relies on a broker, creating a single point of failure unless high-availability brokers are deployed.

- Not inherently RESTful; integration with web services may require adapters or bridges.

- QoS 2 may be too heavy for highly constrained networks or ultra-low-power devices.

3.1.8. Typical Use Cases for MQTT and MQTT-SN

- Telemetry reporting for sensors and actuators.

- Smart home ecosystems where multiple devices share real-time status.

- Industrial IoT for data aggregation and monitoring.

- Cloud IoT platforms where scalable, many-to-many messaging is required.

3.2. CoAP

3.2.1. Overview for CoAP

3.2.2. Transport Layer for CoAP

3.2.3. Reliability and Messaging

3.2.4. Extensions and Features

3.2.5. Security for CoAP

3.2.6. Strengths for CoAP

- Extremely lightweight, suitable for constrained devices and low-power networks.

- RESTful model allows easy integration with existing web infrastructure.

- Supports asynchronous notifications, multicast, and proxying.

- Flexible security options with DTLS and OSCORE.

3.2.7. Limitations for CoAP

- Less suited for many-to-many communication without additional observe subscriptions.

- Relies on UDP, which may be blocked or restricted in some networks.

- Requires more complex logic for retransmissions and duplicate detection compared to TCP-based protocols.

3.2.8. Typical Use Cases for CoAP

- Sensor and actuator networks in home or industrial IoT.

- IPv6-based networks, especially 6LoWPAN and Thread deployments.

- Energy-efficient monitoring systems, where low bandwidth and power consumption are critical.

- RESTful IoT APIs for direct device control or data collection.

- This section highlights CoAP as the ideal protocol for constrained, RESTful IoT applications, contrasting with MQTT’s publish/subscribe model.

- Provides a detailed technical analysis of MQTT, CoAP, and others, specifically dedicated to application-level protocols [36].

3.3. LwM2M (Lightweight M2M)

3.3.1. Overview for LwM2M

3.3.2. Transport Layer for LwM2M

3.3.3. Features and Functionality

3.3.4. Security for LwM2M

3.3.5. Strengths for LwM2M

- Standardized object and resource model ensures interoperability across vendors and devices.

- Combines telemetry and device management in a single protocol, reducing implementation complexity.

- Efficient for constrained networks and devices with limited power and memory.

- Supports secure provisioning and firmware updates, enabling scalable IoT deployments.

3.3.6. Limitations for LwM2M

- Slightly more complex than CoAP alone, requiring device models to be implemented correctly.

- Performance may be impacted in extremely low-power or high-latency networks due to security and management overhead.

- Less suited for many-to-many pub/sub communication without additional brokers or gateways.

3.3.7. Typical Use Cases for LwM2M

- Large-scale cellular IoT deployments with NB-IoT or LTE-M.

- Remote device provisioning, configuration, and monitoring for smart meters, wearables, and industrial sensors.

- Secure firmware update management for devices deployed in the field for years.

- Any IoT scenario requiring both telemetry and lifecycle management.

- This section establishes LwM2M as the preferred protocol for managing constrained IoT devices at scale, building on CoAP while adding standardized device lifecycle capabilities.

3.4. AMQP (Advanced Message Queuing Protocol)

3.4.1. Overview for AMQP

3.4.2. Transport Layer for AMQP

3.4.3. Communication Model for AMQP

3.4.4. Security for AMQP

3.4.5. Strengths for AMQP

- Reliable and robust: Guarantees delivery, order, and transactions.

- Enterprise integration: Bridges IoT devices with IT systems, enterprise message buses, and industrial platforms.

- Flexible routing: Supports direct messaging, publish/subscribe, and complex routing topologies.

- Scalable: Suitable for high-throughput environments with multiple producers and consumers.

3.4.6. Limitations for AMQP

- Resource-intensive: Higher memory and processing requirements compared to lightweight protocols like MQTT or CoAP.

- Not ideal for constrained devices: TCP overhead and broker complexity make it unsuitable for very low-power or ultra-constrained IoT devices.

- Deployment complexity: Requires configuration of brokers and routing logic.

3.4.7. Typical Use Cases for AMQP

- Industrial IoT systems for monitoring and control, where message reliability is critical.

- Enterprise IoT deployments integrating sensors, actuators, and business applications.

- Scenarios requiring complex routing, guaranteed delivery, or transactional messaging, such as supply chain tracking and asset management.

- This section positions AMQP as a robust, enterprise-focused protocol, suitable for industrial IoT and large-scale deployments requiring high reliability and complex messaging patterns.

3.5. XMPP (Extensible Messaging and Presence Protocol)

3.5.1. Overview for XMPP

3.5.2. Transport Layer for XMPP

3.5.3. Communication Model for XMPP

3.5.4. Security for XMPP

3.5.5. Strengths for XMPP

- Highly extensible, allowing custom features without protocol redesign.

- Supports presence, notifications, and structured messaging, useful for interactive IoT applications.

- A decentralized server network allows distributed deployments and federation.

- Mature ecosystem with libraries and tools for many platforms.

3.5.6. Limitations for XMPP

- XML verbosity increases bandwidth usage, making it less efficient for constrained networks.

- Long-lived TCP connections can be challenging for battery-powered devices.

- Higher memory and CPU requirements compared to lightweight protocols.

- Not ideal for extremely low-power or low-bandwidth IoT deployments.

3.5.7. Typical Use Cases for XMPP

- Smart home ecosystems where devices need to report presence and status.

- Interactive IoT applications requiring real-time notifications.

- Federated IoT networks where extensibility and interoperability are key.

- Scenarios where structured messaging, flexibility, and extensibility outweigh bandwidth efficiency concerns.

3.6. WebSockets

3.6.1. Overview for WebSockets

3.6.2. Transport Layer for WebSockets

3.6.3. Communication Model for WebSockets

3.6.4. Security for WebSockets

3.6.5. Strengths for WebSockets

- Enables real-time, low-latency communication between IoT devices and web/cloud applications.

- Persistent connection reduces overhead compared to repeated HTTP requests.

- Works seamlessly with existing web technologies and platforms.

- Supports both text and binary messaging.

3.6.6. Limitations for WebSockets

- TCP connection required: May not be ideal for extremely constrained or low-power devices.

- No native QoS or message reliability guarantees: Must be implemented at the application layer.

- Persistent connections may impact server scalability if many devices are connected simultaneously.

3.6.7. Typical Use Cases for WebSockets

- Streaming telemetry from IoT devices to web dashboards.

- Real-time control of smart home or industrial devices via web interfaces.

- Bridging IoT protocols (MQTT, CoAP) to cloud or web applications.

- Mobile applications that require instant updates from IoT networks.

3.7. HTTP/HTTPS

3.7.1. Overview for HTTP/HTTPS

3.7.2. Transport Layer for HTTP/HTTPS

3.7.3. Communication Model for HTTP/HTTPS

3.7.4. Security for HTTP/HTTPS

3.7.5. Strengths for HTTP/HTTPS

- Universally supported by web servers, cloud platforms, and IoT gateways.

- Simplifies integration with REST APIs, dashboards, and enterprise systems.

- Mature ecosystem with libraries, tools, and standards.

- Supports rich metadata, content negotiation, and web-friendly formats like JSON.

3.7.6. Limitations for HTTP/HTTPS

- Verbose headers and text-based format result in higher bandwidth usage.

- The stateless request/response model is less efficient for frequent or real-time messaging.

- Less suitable for battery-powered, low-bandwidth, or highly constrained devices.

- Requires TCP, which may not be ideal for some low-power networks.

3.7.7. Typical Use Cases for HTTP/HTTPS

- Cloud-connected devices with adequate resources (Wi-Fi appliances, gateways, edge devices).

- RESTful APIs for device telemetry, configuration, and control.

- Integration with web dashboards, cloud analytics platforms, and enterprise applications.

- Firmware and software update delivery for capable devices.

3.8. OPC UA (Open Platform Communications Unified Architecture)

3.8.1. Overview for OPC UA

3.8.2. Transport Layer for OPC UA

3.8.3. Communication Model for OPC UA

3.8.4. Security for OPC UA

3.8.5. Strengths for OPC UA

- Semantic interoperability: Standardized data models allow integration across vendors and systems.

- Flexible communication: Supports client-server and pub/sub patterns.

- Robust security: Comprehensive authentication, encryption, and authorization mechanisms.

- Industrial readiness: Suitable for mission-critical automation, control systems, and IIoT networks.

3.8.6. Limitations for OPC UA

- Higher resource requirements compared to lightweight IoT protocols.

- Implementation complexity can be significant, requiring specialized development tools.

- Less suitable for low-power, constrained devices typical in consumer IoT applications.

3.8.7. Typical Use Cases for OPC UA

- Industrial IoT deployments in manufacturing, energy, and process control.

- Integration of sensors, machines, and SCADA systems.

- Real-time monitoring and control in factory automation.

- Bridging IT and OT systems in Industry 4.0 initiatives.

4. Discussion, Comparative Analysis, and Research Synthesis

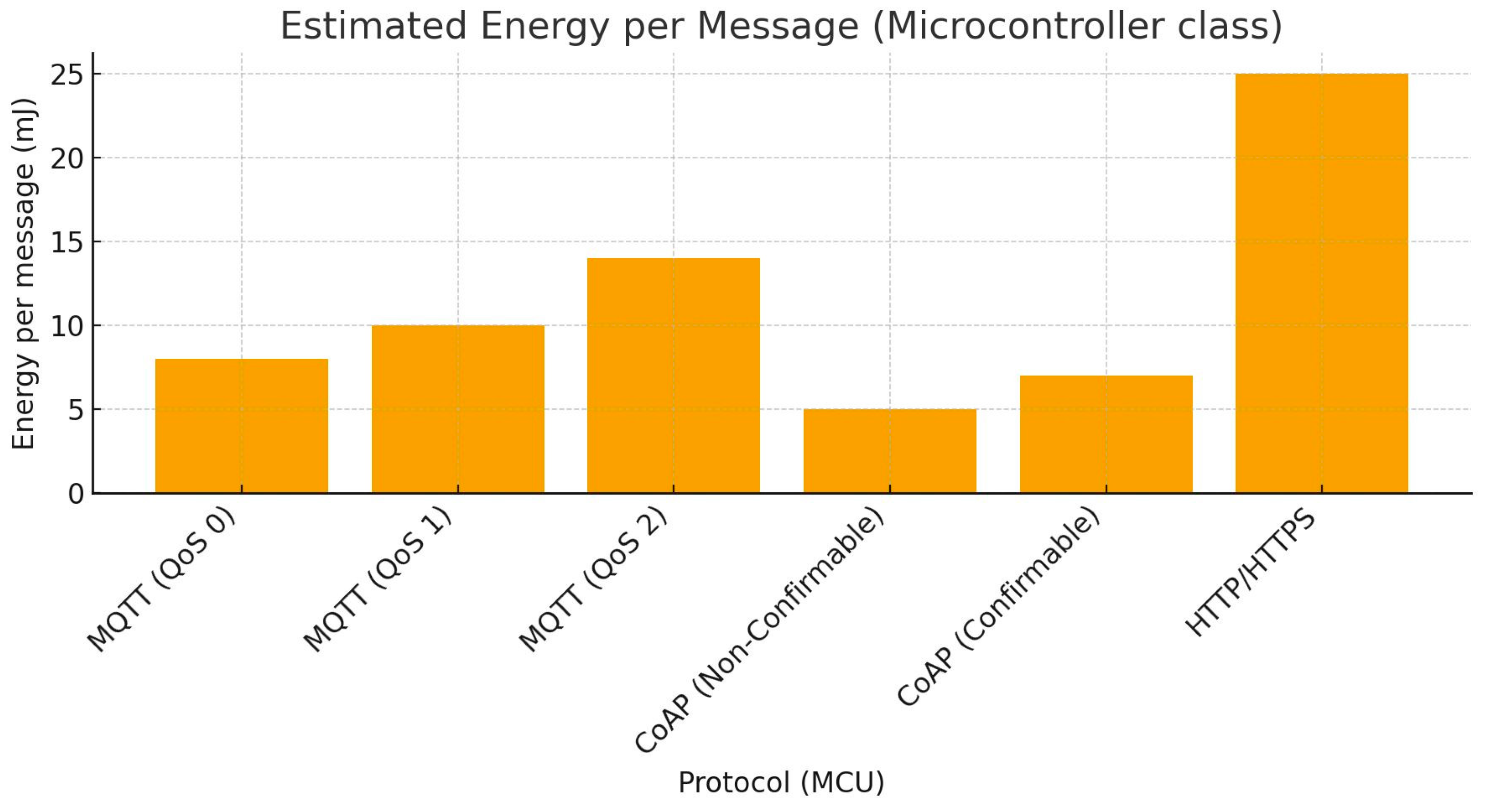

4.1. Performance and Energy Efficiency Trade-Offs

4.2. Security Overheads and Lightweight Solutions

4.3. Interoperability and the Gateway Problem

4.4. The Cloud–Edge Continuum

4.5. Recommendations for Practical Checklist Choosing Protocols

5. Practical Deployments of IoT Communication Protocols

5.1. MQTT in Operational IoT Systems

5.1.1. Smart Home/Consumer IoT

- Philips Hue Bridge (v1/v2) uses MQTT internally for sensor and switch updates.

- Amazon AWS IoT Core officially supports MQTT as its primary protocol.

- Google Cloud IoT Core (until shutdown in 2023) used MQTT as its recommended protocol.

5.1.2. Industrial and SCADA

- Siemens MindSphere uses MQTT for factory telemetry ingestion.

- Bosch IoT Suite uses MQTT for industrial sensors and machine data.

- ABB Ability™ platform uses MQTT for remote asset monitoring.

5.1.3. Automotive/Mobility

- Tesla (fleet telematics) uses MQTT-like lightweight pub/sub for vehicle status and OTA update coordination.

- Volkswagen Industrial Cloud uses MQTT for machine–cloud synchronization.

5.1.4. Telecom

- Vodafone IoT Platform supports MQTT for NB-IoT and LTE-M devices.

- Ericsson IoT Accelerator uses MQTT for device-cloud communication.

5.2. CoAP in Constrained and Low-Power Networks

5.2.1. Smart City Systems

- Street lighting systems (e.g., Philips CityTouch) use CoAP for low-power luminaire communication.

- Smart parking sensors in European pilot cities use CoAP because of NB-IoT/LwM2M compatibility.

5.2.2. Lightweight M2M (LwM2M)

- Quectel NB-IoT modules;

- u-blox NB-IoT devices;

- Huawei OceanConnect IoT Platform;

- ARM Pelion Device Management.

5.2.3. Home Automation

- OpenThread/Google Thread (Mesh networks used in Smart Home) use CoAP messages for commissioning and control.

- Matter (formerly CHIP) uses CoAP-based messaging for local-device commissioning.

5.2.4. Constrained Industrial Devices

- Smart meters in Germany’s Smart Metering Infrastructure (SMI) (partially) use CoAP for readings under low-power conditions.

5.3. HTTP/HTTPS in High-Payload and Cloud-Centric Applications

5.3.1. Consumer IoT

- Smart TVs (Samsung, LG)—all use REST APIs over HTTPS for cloud integration.

- Ring cameras, Nest devices, Wyze, Arlo → HTTPS for event uploads, images, and video control channels.

- IFTTT integrations heavily rely on HTTPS REST.

5.3.2. Industrial IoT

- Siemens SIMATIC systems

- Schneider Electric EcoStruxure

- REST-based APIs used for device management in industrial gateways.

5.3.3. Wearables

- Fitbit, Garmin, Apple HealthKit upload telemetry via HTTPS REST endpoints.

5.3.4. Automotive

- remote lock/unlock

- climate control

- telemetry upload

5.3.5. Cloud Platforms

- AWS IoT (Device Shadow)

- Azure IoT Hub (REST-based twin updates)

- Google Firebase IoT integrations

5.4. Summary: Matching Protocols to Deployment Constraints

- MQTT is selected for scalable telemetry, publish/subscribe workflows, and challenging cellular environments.

- CoAP is preferred for low-power, UDP-based, and mesh or NB-IoT deployments, where minimal overhead is essential.

- HTTP/HTTPS dominates systems with large data transfers, cloud integration, and stringent enterprise IT requirements.

5.5. Comparison: Why Each Protocol Was Chosen in Practice

5.5.1. MQTT Key Reasons

- Extremely low bandwidth usage

- Publish/subscribe model fits asynchronous telemetry

- Supports QoS levels (0,1,2)

- Works well on unreliable networks (cellular, NB-IoT, satellite)

- Very small client code footprint

Type of Systems Chosen by MQTT

- Telemetry-heavy

- Many-to-one aggregation

- Devices with intermittent connectivity

- Industrial gateways

Example Justification

5.5.2. CoAP Key Reasons

- Ultra-low overhead (4-byte header vs. 200–800 bytes for HTTP/TLS)

- Runs on UDP (faster, lower latency, smaller packets)

- Optimized for constrained devices (Class-0/Class-1 MCUs)

- Native support for multicast (unique among IoT protocols)

- Basis of LwM2M (standard for NB-IoT module management)

- Works over Thread and Matter ecosystems

Type of Systems Chosen by CoAP

- Battery-powered sensors

- Smart city nodes (lighting, parking, waste bins)

- Smart home mesh networks

- NB-IoT device management

- Commissioning and local control

Example Justification

5.5.3. HTTP/HTTPS Key Reasons

- Universally supported (browsers, cloud services, firewalls)

- Ideal for large payloads (images, JSON, firmware)

- Easy integration with REST APIs and OAuth2 authentication

- Required for many enterprise/industrial IT systems

- End-to-end encryption with TLS

Type of Systems Chosen by HTTP/HTTPS

- Video doorbells, cameras

- Wearables syncing to cloud

- Car OEM cloud platforms

- Industrial OPC UA over HTTPS

- Any application requiring large or structured data (JSON, video, images)

Example Justification

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fatma, H.; Sofiane, O. A review of application protocol enhancements for IoT. In Proceedings of the Fifteenth International Conference on Mobile Ubiquitous Computing, Systems, Services and Technologies (UBICOMM 2021), Barcelona, Spain, 7 October 2021; pp. 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Syed, A.; Sierra-Sosa, D.; Kumar, A.; Elmaghraby, A. Iot in smart cities: A survey of technologies, practices and challenges. Smart Cities 2021, 4, 429–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaleefah, R.M.; Abed, A.A.; Al-Shareeda, M.A. Empirical Evaluation of MQTT, CoAP and HTTP for Smart City IoT Applications. Int. J. Mechatron. Robot. Artif. Intell. 2025, 1, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Fuqaha, A.; Guizani, M.; Mohammadi, M.; Aledhari, M.; Ayyash, M. Internet of Things: A Survey on Enabling Technologies, Protocols, and Applications. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2015, 17, 2347–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubbi, J.; Buyya, R.; Marusic, S.; Palaniswami, M. Internet of Things (IoT): A Vision, Architectural Elements, and Future Directions. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2013, 29, 1645–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hmissi, F.; Ouni, S. A Survey on Application Layer Protocols for IoT Networks. Int. J. Adv. Telecommun. 2022, 15, 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Bormann, C.; Ersue, M.; Keranen, A. RFC 7228: Terminology for Constrained-Node Networks; IETF: Fremont, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- OASIS. MQTT Version 3.1.1. 2014. Available online: https://docs.oasis-open.org/mqtt/mqtt/v3.1.1/os/mqtt-v3.1.1-os.html (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- OASIS. MQTT Version 5.0. 2019. Available online: https://docs.oasis-open.org/mqtt/mqtt/v5.0/mqtt-v5.0.html (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- HiveMQ. MQTT-SN: What Is It and Why Does It Matter? Available online: https://www.hivemq.com/blog (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- IETF. RFC 7252: The Constrained Application Protocol (CoAP). 2014. Available online: https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc7252 (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- CoAP.space. CoAP Overview. Available online: https://coap.space/ (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Open Mobile Alliance. Lightweight Machine to Machine (LwM2M) Specifications. Available online: https://www.openmobilealliance.org/release/LightweightM2M/ (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- AVSystem. Lightweight M2M (LwM2M) Overview. Available online: https://avsystem.com/blog/iot/lightweight-m2m-lwm2m-overview (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- OASIS. AMQP 1.0 Core Specification. 2011. Available online: https://docs.oasis-open.org/amqp/core/v1.0/os/amqp-core-overview-v1.0-os.html (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- RabbitMQ. AMQP 0-9-1 Protocol Specification. Available online: https://www.rabbitmq.com/amqp-0-9-1-protocol.html (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- IETF. RFC 6120: Extensible Messaging and Presence Protocol (XMPP): Core. 2011. Available online: https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc6120 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Thangavel, D.; Ma, X.; Valera, A.; Tan, H.X.; Tan, C.K.Y. Performance Evaluation of MQTT and CoAP via a Common Middleware. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Ninth International Conference on Intelligent Sensors, Sensor Networks and Information Processing (ISSNIP), Singapore, 21–24 April 2014; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Luzuriaga, J.E.; Perez, M.; Boronat, P.; Cano, J.C.; Calafate, C.; Manzoni, P. A comparative evaluation of AMQP and MQTT protocols over unstable and mobile networks. In Proceedings of the 12th Annual IEEE Consumer Communications and Networking Conference (CCNC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 9–12 January 2015; pp. 931–936. [Google Scholar]

- XMPP.org. XMPP Extensions. Available online: https://xmpp.org/extensions/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- WHATWG. WebSockets Standard. Available online: https://websockets.spec.whatwg.org/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Al-Fuqaha, A.; Khreishah, A.; Guibene, W.; Othman, J.B. An Overview of Existing Approaches and Challenges in Securing IoT. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Smart Grid Communications (SmartGridComm), Sydney, Australia, 6–9 November 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Fuqaha, A.; Khreishah, A. Securing IoT Communications: Challenges and Approaches. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Smart Grid Communications (SmartGridComm), Sydney, Australia, 6–9 November 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Goworko, M.; Wytrebowicz, J. A Secure Communication System for Constrained IoT Devices—Experiences and Recommendations. Sensors 2021, 21, 6906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IETF. RFC 6455: The WebSocket Protocol. 2011. Available online: https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc6455 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- IETF. RFC 2616: Hypertext Transfer Protocol—HTTP/1.1. 1999. Available online: https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc2616 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Cirani, S.; Picone, M.; Gonizzi, P.; Veltri, L.; Ferrari, G. IoT-OAS: An OAuth-Based Authorization Service Architecture for Secure Services in IoT Scenarios. IEEE Sens. J. 2014, 15, 1224–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloi, G.; Caliciuri, G.; Fortino, G.; Gravina, R.; Pace, P.; Russo, W.; Savaglio, C. A Mobile Multi-Technology Gateway to Enable IoT Interoperability. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE First International Conference on Internet of Things and Systems (ICIOTS), Tiraspol, Moldova, 5–7 July 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- AWS. The Difference Between HTTPS and HTTP. Available online: https://aws.amazon.com/compare/the-difference-between-https-and-http/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- OPC Foundation. OPC UA Specifications. Available online: https://reference.opcfoundation.org/ (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- EMQ. OPC UA Protocol Overview. Available online: https://www.emqx.com/en/blog/opc-ua-protocol (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Chacon, G.S.; Venegas, C.; Baca, M.; Rodriguez, I.; Marrone, L. Open middleware proposal for iot focused on industry 4.0. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 2nd Colombian Conference on Robotics and Automation (CCRA), Atlántico, Colombia, 3 November 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Nuratch, S. Applying the MQTT protocol on embedded system for smart sensors/actuators and iot applications. In Proceedings of the 2018 15th International Conference on Electrical Engineering/Electronics, Computer, Telecommunications and Information Technology, Chiang Rai, Thailand, 18–21 July 2018. no. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Esfahani, A.; Mantas, G.; Matischek, R.; Saghezchi, F.B.; Rodriguez, J.; Bicaku, A.; Maksuti, S.; Tauber, M.G.; Schmittner, C.; Bastos, J. A lightweight authentication mechanism for m2m communications in industrial iot environment. IEEE Internet Things J. 2017, 6, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Z.; Yang, S.; Yu, Y.; Vasilakos, A.V.; Mccann, J.A.; Leung, K.K. A survey on the ietf protocol suite for the internet of things: Standards, challenges, and opportunities. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 2013, 20, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagiannis, V.; Chatzimisios, P.; Vazquez-Gallego, F.; Alonso-Zarate, J. A Survey on application layer protocols for the internet of things. J. Comput. Netw. Commun. 2015, 2015, 295734. [Google Scholar]

- D’Ortona, C.; Tarchi, D.; Raffaelli, C. Open-source MQTT-based End-to-End IoT system for smart city. Scenar. J. Futur. 2022, 14, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagou, I.C.; Katsoulis, S.; Nannos, E.; Zantalis, F.; Koulouras, G. A comprehensive evaluation of IoT cloud platforms: A feature-driven review with a decision-making tool. Sensors 2025, 25, 5124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roccatello, E.; Pagano, A.; Levorato, N.; Rumor, M. State of the art in internet of things standards and protocols for precision agriculture with an approach to semantic interoperability. J. Netw. 2025, 5, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallabi, F.M.; Khater, H.M.; Tariq, A.; Hayajneh, M.; Shuaib, K.; Barka, E.S. Smart healthcare network management: A comprehensive review. Mathematics 2025, 13, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunkeler, U.; Truong, H. MQTT-S—A Publish/Subscribe Protocol for Wireless Sensor Networks. In Proceedings of the 2008 3rd International Conference on Communication Systems Software and Middleware and Workshops (COMSWARE’08), Bangalore, India, 6–10 January 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cirani, S.; Davoli, L.; Ferrari, G.; Léone, R.; Medagliani, P.; Picone, M.; Veltri, L. A Scalable and self-configuring architecture for service discovery in the Internet of Things. IEEE IoT J. 2014, 1, 508–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, R.; Thompson, M. The MQTT Protocol: A Technical Overview; IBM Device: Armonk, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Shelby, Z.; Hartke, K.; Bormann, C. The Constrained Application Protocol (CoAP). RFC 7252; IETF: Fremont, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hartke, K. Observing Resources in CoAP. RFC 7641; IETF: Fremont, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fielding, R.; Reschke, J. Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP/1.1). RFC 7231; IETF: Fremont, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla, E. The Transport Layer Security (TLS) Protocol Version 1.3. RFC 8446; IETF: Fremont, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ochoa, H.J.J.; Peña, R.; Mezquita, Y.L.; Gonzalez, E.; Camacho-Leon, S. Comparative analysis of power consumption between MQTT and HTTP protocols in an IoT platform designed and implemented for remote real-time monitoring of long-term cold chain transport operations. Sensors 2023, 23, 4896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauda, A.; Flauzac, O.; Nolot, F. A Survey on IoT Application Architectures. Sensors 2024, 24, 5320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayoub, I.; Balakrichenan, S.; Khawam, K.; Ampeau, B. DNS for IoT: A Survey. Sensors 2023, 23, 4473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jerzy, K.; Martyna, W.K.; Ilona, J.G.; Piotr, K.; Aleksandra, P.; Robert, W.; Teresa, S.-W. Energy Footprint and Reliability of IoT Communication Protocols for Remote Sensor Networks. Sensors 2025, 25, 6042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavriilidis, N.O.; Halkidis, S.T.; Petridou, S. Empirical Evaluation of TLS-Enhanced MQTT on IoT Devices for V2X Use Cases. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łeska, S.; Furtak, J. Procedures for Building a Secure Environment in IoT Networks Using the LoRa Interface. Sensors 2025, 25, 3881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, A.; Aldawghan, H.; Aljughaiman, A. A Review of the Authentication Techniques for Internet of Things Devices in Smart Cities: Opportunities, Challenges, and Future Directions. Sensors 2025, 25, 1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Turjman, F.; Abujubbeh, M. IoT-enabled smart grid via SM: An overview. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 96, 579–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ficili, I.; Giacobbe, M.; Tricomi, G.; Puliafito, A. From Sensors to Data Intelligence: Leveraging IoT, Cloud, and Edge Computing with AI. Sensors 2025, 25, 1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naik, N. Choice of Effective Messaging Protocols for IoT Systems: MQTT, CoAP, AMQP and HTTP. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Symposium on Systems Engineering (ISSE), Vienna, Austria, 11–13 October 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Dizdarević, J.; Carpio, F.; Jukan, A.; Masip-Bruin, X. A survey of communication protocols for internet of things and their challenges. Sensors 2019, 19, 948. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Masri, E.; Kalyanam, K.R.; Batts, J.; Kim, J.; Singh, S.; Vo, T.; Yan, C. Investigating Messaging Protocols for the Internet of Things (IoT). IEEE Access 2020, 8, 94880–94911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, U.; Juvekar, C.; Fuller, S.H.; Chandrakasan, A.P. EeDTLS: Energy-efficient datagram transport layer security for the internet of things. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Global Communications Conference, GLOBECOM 2017, Singapore, 4–8 December 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

| Protocol | Range/Connectivity | Throughput | Power Consumption | Topology/Architecture | Security Options | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MQTT | Wi-Fi, Ethernet, Cellular, LPWAN | Low–Moderate | Low (suitable for battery devices) | Publish/Subscribe (Broker-based) | TLS, username/password, OAuth2 | Telemetry, remote monitoring, cloud-integrated IoT |

| MQTT-SN | Zigbee, LoRaWAN, UDP-based networks | Low | Very Low | Publish/Subscribe (Broker-based) | DTLS, pre-shared keys | Constrained sensor networks and low-power devices |

| CoAP | 6LoWPAN, Thread, Wi-Fi, LPWAN | Low–Moderate | Very Low | Client/Server, optional Observe (pub/sub-like) | DTLS, OSCORE | Low-power sensor/actuator networks, RESTful APIs |

| LwM2M | NB-IoT, LTE-M, 6LoWPAN, Thread | Low–Moderate | Low | Client/Server, Object-oriented resource model | DTLS, OSCORE | Device management, provisioning, firmware updates |

| AMQP | Ethernet, Wi-Fi, Cellular | Moderate–High | Moderate | Broker-based, point-to-point, or pub/sub | TLS, SASL, role-based access control | Industrial IoT, enterprise integration, reliable messaging |

| XMPP | Ethernet, Wi-Fi, Cellular | Low–Moderate | Moderate | Client/Server, pub/sub extensions | TLS, SASL, access control | Real-time notifications, presence-aware IoT applications |

| WebSockets | Wi-Fi, Ethernet, Cellular | Moderate–High | Moderate | Full-duplex persistent connection | TLS, HTTP authentication | Real-time dashboards, mobile apps, and cloud IoT integration |

| HTTP/HTTPS | Wi-Fi, Ethernet, Cellular | Moderate–High | Moderate–High | Client/Server (Request/Response) | TLS, OAuth2, API keys, certificates | RESTful APIs, cloud integration, web dashboards |

| OPC UA | Ethernet, Wi-Fi, Industrial networks | Moderate–High | Moderate–High | Client/Server, pub/sub, object-oriented model | TLS, certificates, username/password, RBAC | Industrial automation, factory monitoring, IIoT networks |

| Protocol | Mode | Device Class | Latency (ms) | Throughput | Packet Loss (%) | Reliability | Notes/References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MQTT | QoS 0 | MCU | 50–70 | 120–150 msg/s | 2% | Moderate | Very lightweight [40] |

| MQTT | QoS 0 | Edge | 45–60 | 200 msg/s | 1.5% | High | Handles higher loads [40] |

| MQTT | QoS 1 | MCU | 65 | 100–130 msg/s | 1% | Very High | ACK adds overhead [41] |

| MQTT | QoS 1 | Edge | 60 | 180–200 msg/s | 0.8% | Very High | Minimal latency impact [41] |

| MQTT | QoS 2 | MCU | 90–110 | 80–120 msg/s | 0% | Highest | CPU-heavy for MCUs, QoS2 overhead [42] |

| MQTT | QoS 2 | Edge | 90 | 160 msg/s | 0% | Highest | Good for critical logs [42] |

| CoAP | Non-confirmable | MCU | 40 | 150–200 msg/s | 5% | Moderate | Best-effort mode [43] |

| CoAP | Non-confirmable | Edge | 35–40 | 200–220 msg/s | 3% | Moderate | Efficient for telemetry [43] |

| CoAP | Confirmable | MCU | 60–80 | 100–130 msg/s | 2% | High | Based on retransmission logic [44,45] |

| CoAP | Confirmable | Edge | 50–65 | 140–160 msg/s | 1% | Very High | Still lightweight [44] |

| HTTP | HTTP/1.1 | MCU | 100–150 | 50–100 req/s | 0.5% | High | TCP overhead [46]; |

| HTTP | HTTP/1.1 | Edge | 90–120 | 100–150 req/s | 0.5% | High | Suitable for dashboards [46] |

| HTTPS | TLS-enabled | MCU | 200–250 | 40–80 req/s | 0% | Very High | TLS cost; TLS handshake expensive [47] |

| HTTPS | TLS-enabled | Edge | 180–210 | 80–120 req/s | 0% | Very High | Easily handled [47] |

| Protocol/Variant | Average Power (mW, Full System) | σ (mW) | Device Class | Relative to HTTP (%) | Energy Savings vs. HTTP (%) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HTTP/HTTPS | 670 | ±16 | NodeMCU (microcontroller) | 100% (baseline) | 0% | Verbose headers/connections; highest for request/response. |

| MQTT QoS 2 | 650–660 | ±20 | NodeMCU (microcontroller) | 97–98% | 2–3% | Estimated (QoS handshakes add ~5–8% vs. QoS 1); avoid in battery ops. |

| MQTT QoS 1 | 614 | ±22 | NodeMCU (microcontroller) | 92% | 8% | At least once; lowest MQTT draw in this workload (optimized ACKs). |

| MQTT QoS 0 | 630 | ±19 | NodeMCU (microcontroller) | 94% | 6% | Fire-and-forget; scalable but slightly higher than QoS 1 here. |

| CoAP CON (Confirmable) | 600–620 | ±18 | Z1 mote (microcontroller) | 90–93% | 7–10% | ACK equiv. to QoS 1; RESTful, good for edge. |

| CoAP NON (Non-Confirmable) | 590–610 | ±17 | Z1 mote (microcontroller) | 88–91% | 9–12% | Stateless UDP; top for loss-tolerant telemetry. |

| MQTT-SN (over UDP) | 550–580 | ±15 | Z1 mote (microcontroller) | 82–87% | 13–18% | Best overall; topic-ID efficiency for non-IP nets like LPWAN. |

| Protocol | Real-World Implementation/Product | Industry | Why This Protocol Was Chosen (Technical Reasoning) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MQTT | AWS IoT Core | Cloud IoT | Designed for millions of devices needing scalable pub/sub messaging; low overhead; supports QoS. |

| MQTT | Bosch IoT Suite | Industrial IoT | Efficient telemetry from machines; reliable delivery via QoS 1/2; async event model. |

| MQTT | Siemens MindSphere | Industrial automation | Low network load, good for PLC/SCADA integration and aggregated sensor streams. |

| MQTT | Tesla fleet telematics (internal) | Automotive | Lightweight binary protocol works well over mobile networks with unstable connectivity. |

| MQTT | Vodafone NB-IoT Device Platform | Telecom | NB-IoT requires minimal overhead and long battery life; MQTT fits constraints. |

| CoAP | Philips CityTouch smart street lighting | Smart City | UDP-based low latency; extremely low overhead (4-byte header); ideal for constrained nodes. |

| CoAP | OMA LwM2M (Quectel, u-blox NB-IoT modules) | Telecom/NB-IoT | CoAP enables device management, firmware updates, and resource access on small MCUs. |

| CoAP | Thread/Google Nest ecosystem | Smart Home Mesh | Mesh networks require tiny packets and fast local delivery; CoAP works over IEEE 802.15.4. |

| CoAP | Matter/CHIP (commissioning) | Smart Home | Secure onboarding + low power; CoAP + DTLS/OSCORE ideal for constrained device commissioning. |

| HTTP/HTTPS | Ring, Nest, Wyze cameras | Consumer IoT | HTTPS supports large payloads (images, video events) and integrates with web infrastructure. |

| HTTPS | BMW ConnectedDrive, Volvo OnCall | Automotive | REST APIs fit cloud services; HTTPS ensures end-to-end encryption and easy backend integration. |

| HTTPS | Fitbit, Garmin, Apple HealthKit | Wearables | Cloud synchronization uses RESTful APIs; HTTPS simplifies authentication (OAuth2). |

| HTTPS | OPC UA over HTTP(S) (Siemens, Schneider) | Industrial | HTTP(S) allows enterprise firewall traversal and integration with IT systems. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Petrescu, I.; Niculae, E.; Vulturescu, V.; Dimitrescu, A.; Ungureanu, L.M. Transport and Application Layer Protocols for IoT: Comprehensive Review. Technologies 2025, 13, 583. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies13120583

Petrescu I, Niculae E, Vulturescu V, Dimitrescu A, Ungureanu LM. Transport and Application Layer Protocols for IoT: Comprehensive Review. Technologies. 2025; 13(12):583. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies13120583

Chicago/Turabian StylePetrescu, Ionel, Elisabeta Niculae, Viorel Vulturescu, Andrei Dimitrescu, and Liviu Marian Ungureanu. 2025. "Transport and Application Layer Protocols for IoT: Comprehensive Review" Technologies 13, no. 12: 583. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies13120583

APA StylePetrescu, I., Niculae, E., Vulturescu, V., Dimitrescu, A., & Ungureanu, L. M. (2025). Transport and Application Layer Protocols for IoT: Comprehensive Review. Technologies, 13(12), 583. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies13120583