1. Introduction

E-commerce and FinTech are currently booming in China. The growing consumer market is accompanied by internet finance, by which consumers can easily borrow money from financial institutions through online platforms. As a result, the growing risks of the financial institutions are of concern to the government and regulatory bodies. Consequently, the securitization market in China has grown rapidly in recent years. Securitization in China has experienced a great increase since 2014, and it is now the second-largest securitization market in the world (

Hogan Lovells 2019). The main reason for this rapid growth is the simultaneous release by the China Banking Regulatory Commission (CBRC) and the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) of documents to implement a reform that replaced the approval system for asset securitization with a filing system (

Tang et al. 2017). Due to financial disintermediation and the need for central banks to establish interest rate corridors, commercial banks are increasingly enriching their asset allocation choices, which also influence the investment in securities (

Huang et al. 2019). In 2019, the total volume of ABS issued in China reached USD340 billion, marking a 16.69% increase compared with 2018. The total outstanding volume of ABS by the end of 2019 stood at USD566 billion, a 27% increase compared with 2018 (

Phua 2020). The remarkable growth of securitization in China is similar to that in the United States before the global financial crisis of 2007–2009. The securitization market in the United States also experienced rapid growth before the global financial crisis from 2007 to 2009. Many commentators cite the remarkable growth of securitization in the United States as a major contributor to the ensuing crisis. Part of the argument is that securitization creates an additional layer of information asymmetry in the origination of a loan, which results in adverse selection, moral hazard problems, and thus higher default rates. China’s securitization market, as mentioned, has also experienced remarkable development. The question of whether securitization affects the financial stability in China has yet to be answered and is a growing concern for authorities. The answer might depend on the standard of information transparency, and a high degree of information transparency will always benefit an authority’s monitoring activities and help to protect investors.

One of the effective ways to improve the standard of information transparency is to apply FinTech and emerging technologies in the securitization market against the background of the digital transformation of banking. Due to the new digital giants in China—Alibaba and Tencent—and the COVID-19 pandemic, traditional Chinese banks have tended to increase their focus and efforts on digital transformation. For example, some of these traditional banks have leveraged FinTech and emerging technologies, such as machine learning, artificial intelligence, big data, cloud computing, and blockchain, to shape their operating model enterprise-wide. Machine learning and artificial intelligence have had a strong impact on credit risk management, which can be used to deal with the problems of information asymmetry (

Mhlanga 2021). According to

Deloitte’s (

2018b) report, cloud computing, big data, artificial intelligence, and blockchain technology entered the stage of comprehensive application in the banking industry in 2018, and “FinTech”, “Inclusive Finance”, and “Asset Management” have become key words in many banks’ annual reports. FinTech and emerging technologies have also been applied in the securitization market to enhance its standard of information transparency. More specifically, all loan data can be placed on a blockchain. Those loan data thus become immutable and are time-stamped on a verifiable audit trail (

Structured Finance Industry Group & Chamber of Digital Commerce 2017). Blockchain technology could be used to automatically share and analyze data in line with regulatory requirements; underlying loans, for example, could be easily and automatically matched against the securitization’s proposed structure, thus making compliance easier (

Sindle et al. 2017).

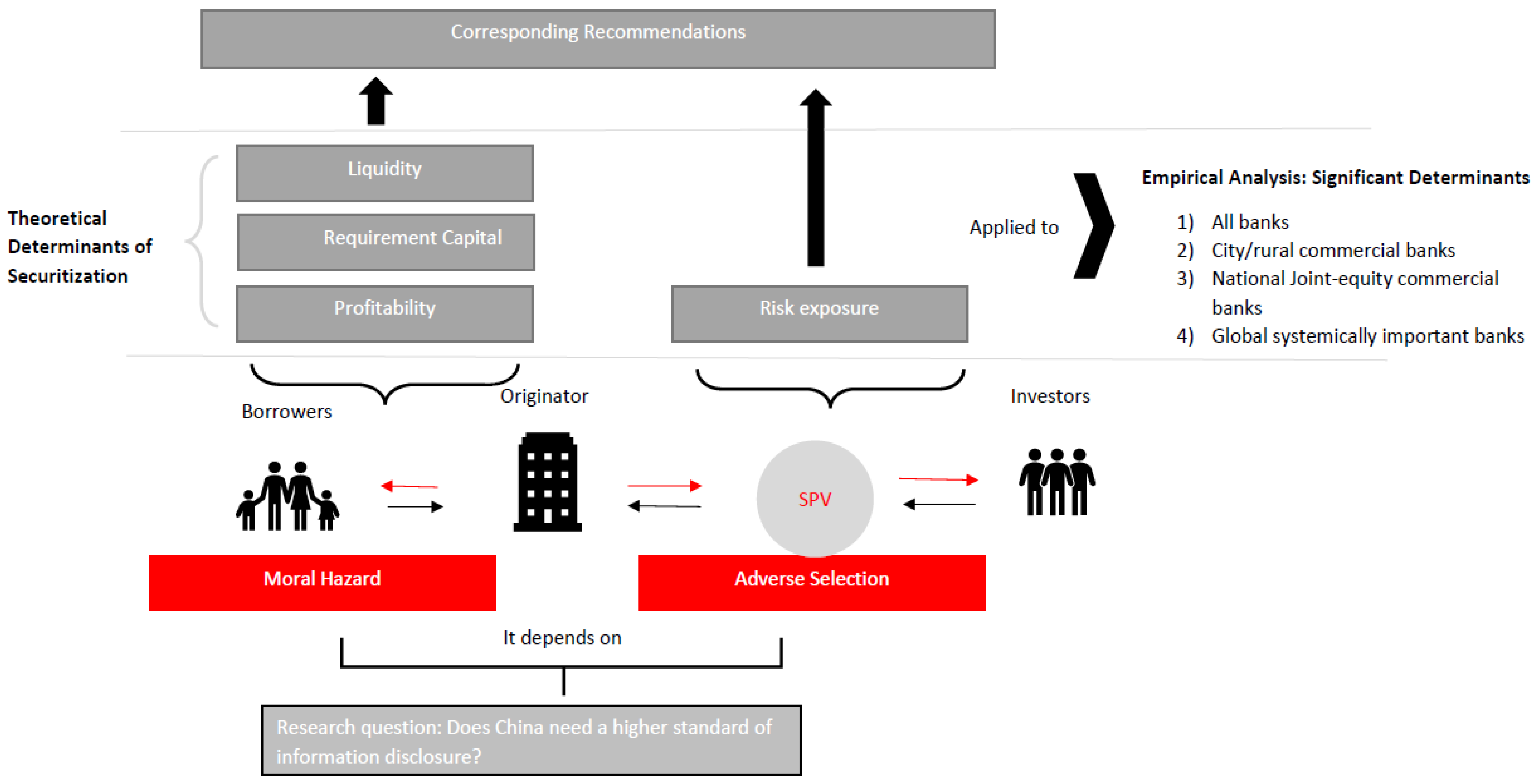

It is currently unclear whether the digital transformation of banking can reduce the impact of information asymmetry and whether information transparency regulations are sufficient for the supervision of securitization or the need to leverage FinTech and emerging technologies. Thus, this study aims to answer the following question: Does China need a higher standard of information disclosure to protect against its risks? To answer this research question, we examined the potential moral hazard and adverse selection problems in securitization and compared those problems in two periods. The first period is pre-2017Q4 and the second period is post-2017Q4. Post-2017Q4 represents the stage of FinTech’s comprehensive application in the banking industry.

The moral hazard and adverse selection problems can be tested by the motivations for the securitization of loans. More details and reasons can be found in

Section 2. The original research on the determinants of the securitization of loans emerged during the 1980s, when a strand of U.S. research studied loan sales, an instrument that is similar to loan securitization (

Giddy 1985;

Pavel 1986;

Pavel and Phillis 1987). Giddy found that capital requirement is an important determinant for loan sales.

Pavel and Phillis (

1987) proved that securitization provides a means of reducing a bank’s credit risks. After the global financial crisis of 2007–2009, research in this area resurfaced. The starting research was on the determinants of European banks’ engagement in loan securitization (

Bannier and Hänsel 2008). They examined firm-specific and macroeconomic factors that drive financial institutions’ decisions to engage in loan securitization transactions. Bank size, credit risk, liquidity, and performance are the four main factors of load securitization transactions in European banks. Two similar papers then reported an empirical study on Italy and Spanish loan securitization markets, respectively (

Affinito and Tagliaferri 2010;

Cardone-Riportella et al. 2010). The result of the study from

Affinito and Tagliaferri (

2010) is similar to that of Bannier and Hänsel. However,

Cardone-Riportella et al. (

2010) claimed that liquidity and performance are the only two decisive factors in securitization. Credit risk is not the main determinant.

Acharya et al. (

2013) also found that risk exposure failed to promote increased securitization growth, which means that banks were securiting without transferring the risk to investors. Recently, the topic on the determinants of loan securitization in European banks was studied again (

Farruggio and Uhde 2015), and the determinants of loan securitization in the pre-financial crisis and the post-financial crisis were compared. The determinants of loan securitization changed remarkably over the pre-crisis and crisis periods.

In accordance with these recent journals, (1) the first contribution of this paper is to study the determinants that drive securitization in the Chinese banking section. Markets in different regions and countries reflect the varying outcomes of securitization determinants. The determinants of securitization in China might be quite distinct from previous research. This paper compares the determinants in different types of bank, and how securitization in these various types of banks are affected by the determinants. (2) Additionally, this study proposes and explains why the four determinants mentioned above can be used to examine the problems of information asymmetry in securitization. Specifically, a securitization determinant study reflects not only the motivation of securitization in the banking section, but also the financial stability. Financial stability is influenced by information asymmetry. Information asymmetry is reflected by moral hazards and adverse selection. Moral hazards and adverse selection are tested by the four determinants. After examining how these four determinants are related to the moral hazard and adverse selection problems in securitization, we can then assess whether current information transparent standards are sufficient for securitization development in China. (3) Finally, this study investigates the effect of FinTech in China’s banking sector by comparing the change in securitization determinants in the two periods.

Summarizing our results, we find that the risk exposure is the most significant determinant, followed by liquidity and profitability before the comprehensive FinTech application in China. After that, risk exposure is still the motivation of securities issuance, but there is no evidence that liquidity and performance can promote loan securitization transactions. Capital requirement could be the motivation for securities issuance in commercial banks. Additionally, by comparing the outcomes of the determinants at two stages, this study finds that the application of FinTech can reduce information asymmetry in the securitization market dramatically, especially for moral hazards. However, we still cannot fully reject the influence of banks’ incentives on risk transfers to outside investors after a comprehensive FinTech application. Therefore, the answer to the research question is that China still requires a higher standard of information disclosure to protect against its risks. The remainder of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 provides the theoretical background and summarizes earlier empirical evidence on securitization determinants, followed by the theories of adverse selection and moral hazards. In

Section 2.3, we will explain how those securitization’s determinants are linked to adverse selection and moral hazards. Subsequently,

Section 3 presents the empirical methodology, a data description, and variable definitions and empirical models. Empirical results are presented in

Section 4, where both univariate analysis and multivariate analysis are given. According to the empirical results,

Section 5 will discuss the findings and link them to the adverse selection and moral hazard problems.

Section 6 will provide corresponding recommendations.

Section 7 concludes.

5. Discussion

5.1. Discussion of Results

This paper investigates what drives bank securitization in China and compares determinants before and after 2017Q4. Generally, the paper shows that, before 2017Q4, a bank was more likely to issue securities if the bank’s credit risk exposure, its liquidity, and its performance were higher. A bank’s credit risk was still a main driver of securitization issuance volume. The regulatory capital arbitrage also influenced securitization decisions. However, the liquidity and performance were not determinants of securitization issuance after 2017Q4. Specifically, credit risk exposure was the most significant determinant compared to the other two. The main motivation of bank securitization could have been credit risk transfers, followed by increased liquidity and improved profitability. Interestingly, capital requirement—or, more precisely, (5) the total equities to total assets and (6) the tier one ratio—did not seem to influence banks’ securitization decisions very strongly before 2017Q4. However, these two variables were statistically significant with respect to securitization issuance after 2017Q4. Liquidity—or, more precisely, (1) net loans to deposits and short-term funding and (2) liquidity assets to deposits and short-term funding—did not seem to influence banks’ securitization decisions very strongly. (5) The cost-to-income ratio and (6) the return on assets also did not seem to influence banks’ securitization decisions strongly after 2017Q4.

The paper also shows that the four determinants in different types of banks display different propensities toward securitization activities in the two periods. To differentiate motivations of securitization between the varying types of banks, this paper looks particularly at the varying types of bank groups in more detail. Before 2017Q4, two types of bank group (the commercial bank group and the national commercial bank group) were used in the empirical models. The findings indicate that risk exposure was still the most important determinant, which is the case in all banks. The (3) loan loss reserves to total loans and (4) the impaired loans to total loans, measuring credit risk exposure, presented statistical significance in the group of commercial banks. Additionally, credit risk exposure affected bank securitization more obviously—the coefficients of (3) and (4) were much higher than those of the other determinants. The second important determinant that drives banks’ securitization was liquidity. (1) The net loans to deposits and short-term funding were statistically significant with respect to securitization transaction volumes, except in the group of national commercial banks. However, because the p-values and coefficients of the liquidity variables were lower than those of risk exposure, the liquidity determinant was not as important. The profitability determinant also drove securitization transactions in all commercial banks but was less important than the above two determinants, which is shown by the lower p-values of profitability. Consistent with the results of all banks, the capital requirement determinant was considered the least important determinant. It is only related to securitization issuance in the group of national commercial banks. After 2017Q4, the all-bank group and the national commercial bank group were the only two groups that issued their securities because of the risk exposure. However, the capital requirement determinant was found to be related to securitization issuance in the group of all banks.

Risk exposure is the most important determinant for bank securitization, by bank group analysis and by different types of bank analysis, for the whole period. Higher credit risks in a bank has motivates a larger part of an asset-securitized portfolio, and these securitized assets are more likely to be low-quality or impaired loans. This is because the bank is able to decrease stress costs and improve risk management when it removes these low-quality or impaired loans from the balance sheet via securitization transactions and shares those credit risks with investors. Thus, these findings are indicative that securitization is mainly used as a risk transfer. Liquidity was the second most important determinant before 2017Q4, but it was not the determinant after 2017Q4. The use of securitization is regarded as a mechanism in the search for liquidity and, therefore, as a source of additional financing. In this way, banks can newly acquire alternative funding resources and be less vulnerable to liquidity shock. The other important determinant is profitability. The first period indicates that securitization was used as a way to improve performance. Generally, that performance mainly came from intermediation profits via a specific design of securitization loans or by raising cash inflows to retire existing debts that could reduce interest expense. However, improving a bank’s performance via securitization issuance could be more difficult after 2017Q4. The capital requirement did not seem to influence banks’ securitization (except national commercial banks in the first period), but this changed after 2017Q4. It can be stated that regulatory capital arbitrage hampered by the regulatory scheme was difficult to apply in the securitization market, but that has changed in the last three years.

5.2. Determinants, Adverse Selection, and Moral Hazards in Chinese Banking

5.2.1. Adverse Selection

The risk exposure determinant, measuring the quality of loans, can be used to test adverse selection problems. These problems are mainly concerned with securitization transactions between the originator and investors. Generally, the originator has more and superior information about the underlying assets than investors. If a securitization transaction involves serious information asymmetry, where the investor is not clear about the underlying quality of an asset, the securitization originator can move low-quality loans into SPV and sell them to investors. Thus, the quality of underlying assets is key in studying adverse selection problems. If large amounts of low-quality underlying assets are moved from banks and sold to investors, investors are more likely to buy ‘lemons’ from an originator, resulting in adverse selection problems. Based on the background of banking in China as well as our regression results, this paper shows that the securitization transactions made in this setting are related to adverse selection problems for the following reasons.

- (1)

Writing off non-performing loans, asset management companies (AMCs), ‘debt-to-equity’ swaps, and non-performing loan (NPL) securitization are four main ways to tackle non-performing loans in China. They are allowed and supported in banks in China; however, the effects of those approaches in practice are questioned.

The traditional way to tackle non-performing loans is writing them off. This approach is widely used with lower non-performing loans, but it is at the expense of banks’ net profits and decreases the bank’s profitability.

AMCs are another way to tackle NPLs. They acquire distress debt from banks and then progressively restrict and repack those acquisitions in the flowing. The four major AMCs play a critical role in tackling NPLs (

Deloitte 2018a). Building on this, recent reforms allow AMCs, with 35 currently in operation, to take on bad debt. They also permit AMCs to sell bad debt to third-party investors rather than simply acting as warehouses for NPLs (

Foreign and Commonwealth Office 2017). However, there are signs that those corporations rely heavily on bank loans to finance their purchases in order to expand their scale; given the circular relationship with the banks, some local AMCs are simply perpetuating loans to zombie firms (

Foreign and Commonwealth Office 2017). The effects of AMCs are doubtful; those credit risks might be moved from balance sheets but essentially are not eliminated and could even increase risk exposure.

‘Debt-for-equity’ swaps were initiated by the State Council in 2016 to replace bad loans with an equity stake in the relevant companies, becoming another solution to China’s cooperation debts. In theory, debt-for-equity swaps could act as a relatively growth-friendly route to incorporate deleveraging that can decrease the problems of corporate debt problems (

Martin 2016). In other words, ‘debt-to-equity’ swaps aim to decrease high corporate leverage and lower debt risks directly, which could indirectly lower banks’ credit risks. However, in practice, ‘debt-to-equity’ swaps face implementation risks, because banks are compelled to swap bad loans for equity to keep failing ‘zombie’ companies alive (

Fitch 2016). In addition, the ‘debt-for-equity’ swap scheme is unlikely to reach a scale at which it addresses corporate sector leverage in a meaningful way, given the lack of investor interest and the capital constraints of banks (

Nolet and Wong 2017). If ‘debt-to-equity’ swaps cannot deal with high leverage and NPLs efficiently for corporations, then this approach indirectly fails to decrease NPLs in banks.

With the diversification of underlying assets in terms of securitization, non-performance loan securitization has become a new way to deal with NPLs. The mechanism is similar to loan securitization, but the underlying assets are replaced by non-performing assets. In this way, more investors participate in the market to help optimize non-performing assets and increase banks’ non-performance asset disposal (

KPMG 2017b). However, the high risks of these underlying assets could affect the confidence of investors. In order to overcome this issue (

Daniel et al. 2016), banks tend to retain large amounts of high risk tranches. Thus, the high cost of NPL securitization could make tackling credit risks difficult.

- (2)

The official data from CBRC and other financial institution estimations jointly indicate that credit risks in the banking context in China have been boosted in the past few years, and the financial system is on a dangerous trajectory. If the approaches of tackling non-performing loans are less efficient as discussed above, banks will be encouraged to transfer their risks via loan securitization directly.

Even though exposure to credit risks slowed down after 2016 (

KPMG 2017a), NPLs have increased extraordinarily in recent years with the slowdown of the Chinese economy. According to the information disclosed by the CBRC, the various loan balance of commercial banks’ asset portfolios was RMB 98.029 trillion at the end of 2017, representing an increase of RMB 11.121 trillion compared to the end of 2016. The NPL ratio is as high as 1.74% and has risen extraordinarily since 2012 (

DBS 2018). However, foreign institutions have estimated that the NPL ratio would be much higher than is indicated by the official data.

Fitch (

2017) estimated that the NPL ratio could be in a range from 15% to as much as 21%, equivalent to around 11–20% of China’s economy. The

IMF (

2016) estimated a similar ratio, i.e., a total debt at risk, based on individual firm level data on interest coverage ratios and liability ratios, at 15%.

The high NPLs result in increased stress costs and a threatened stability. However, securitization with ‘true sale’ transactions and the ‘bankruptcy-remoteness’ mechanism provide banks with credit risk transfer opportunities. Generally, because of the market mechanisms in securitization, such as lender reputation concerns, the lenders retain high-default-risk loans in their portfolio; while financial risks grow, lenders change dramatically and retain low-default-risk loans in their portfolios (

Agarwal et al. 2012). Thus, when banks are under pressure of high credit risks, they are more likely to share large amounts of low-quality loans via securitization.

It can be summarized that NPLs have increased dramatically in the past few years, but approaches tackling NPLs in practice are doubtful. With a rising risk exposure without efficient methods to tackle risk, high-risk exposure could motivate banks to transfer credit risks from balance sheets via loan securitization directly. In addition, our study indicates that risk exposure presents statistical significance in relation to securitization transaction volume. Higher credit risks in banks drive larger amounts of loan securitization. As mentioned previously, the quality of underlying assets is key to studying adverse selection problems. We conclude that banks tend to pack those low-quality assets from their portfolios and move to SPV to protect themselves against high credit risks. Once a large amount of low-quality or low-performance loans are packaged without efficient information disclosure, investors are more likely to buy low-quality securitizations. This will hurt investor protections and even drive the securitization market down. There are consequences of adverse selection in securitization.

5.2.2. Moral Hazards

In this paper, liquidity, profitability, and capital requirement determinants are used to study moral hazards in bank securitization. Moral hazards are mainly concerned with the relationship between borrowers and banks (originators) or the bank itself. They mainly show that banks use securitization to take on more risks. Specifically, once a bank’s risks are incurred by investors without enough information to supervise the bank’s operations, the bank will take more risks, which results in financial instability. We found, by comparing two periods’ securitization determinants, that moral hazards tended to decrease because these three determinants had a lower influence on securitization issuance. Before 2017Q4, liquidity contributed to serious moral hazard problems in securitization, while the profitability and capital requirement determinants presented a lower association to such problems. However, the capital requirement presented a greater association to moral hazard problems after 2017Q4.

Liquidity

Liquidity is considered an important determinant contributing to moral hazard. Moral hazards in securitization with regard to liquidity are mainly present in lax screening by lenders. Securitization is used to increase bank liquidity according to multiple variable analysis. Banks can acquire additional and sufficient liquidity through securitization. Sufficient liquidity generally encourages banks to offer a larger amount of loans to borrowers and pursue higher profitability. The supply of loans is increased, while the demand is unchanged, and lax screening by lenders can stimulate a higher demand for loans. Lax screening also increases a bank’s financial risks and results in the instability of the financial system, especially for so-called ‘too-big-to-fail’ financial institutions. Additionally, the regulatory scheme also encourages banks to provide more loans to support economic development. The regulatory authorities (China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission) released a regulatory scheme aiming to ease the higher amount of liquidity. The specific operation is the relaxation of their bad loans to a range of 120–150% from the current minimum of 150% (

WSY 2018). This move can help commercial banks improve their capability in guarding against liquidity risks, serve the real economy, and maintain the safe, stable operation of the banking system (

Xinghua 2018). Clearly, banks with the encouragement of a liquidity regulatory scheme lead to large amounts of liquidity from banks to support economic devolvement. This could result in lax screening to a certain degree. We conclude that, before 2017Q4, banks were able to acquire sufficient liquidity and encourage borrowers to take larger loans and that they were more likely to lax-screen borrowers and even offer loans to ineligible borrowers. Therefore, if authorities are not able to acquire enough information to supervise efficiently, lax screening would lose control.

However, Chinese authorities, over the three years prior to the study period, asked banks to restrict the loan supply, especially property loans, to ward off an economic bubble. Banking regulators paid attention to the rebound of the proportion of property loans among their new loans (

Nasdaq 2021). Lax screening by lenders decreased under prudential supervision. We inferred that such regulators reduce moral hazards in securitization.

Profitability

Profitability is not associated with moral hazards in securitization, because profitability fails to drive securitization under our analysis. Even though profitability presents statistical significance in relation to securitization transaction volumes in the majority of banks, the correlation coefficient values are almost zero, which reveals that their effects are limited. This could be explained by that fact that securitization can increase liquidity, lower credit risks, and improve risk management, which can improve performance jointly but not directly. In addition, the tax standard of securitization in China is not mature enough, which is reflected by the lower tax incentives and limits the ways in which performance can be improved via securitization. Before the tax reform, securitization generated taxation problems that did not fully reflect the tax neutrality principle (

Liang 2015). The pilot program for replacing the business tax with a value-added tax (VAT) abolished the business tax in 2016. However, how the application of a VAT affects the securitization is still ambiguous, because it is not relevant to purely domestic securitization transactions (

Phua 2020). Therefore, we conclude that it is difficult for banks to improve their profitability via securitization transactions due to the tax issue and to take more risks. The profitability determinant cannot result in moral hazards in securitization transactions.

Capital Requirement

The capital requirement is not related to moral hazards either. The capital requirement presents no statistical significance in relation to securitizations, which means that most banks do not use loan securitization to save on regulatory capital. This is because the Basel II framework under the ‘standardized approach’ no longer allows for regulatory capital arbitrage. Basel III, which could further enhance the capital regulation, was scheduled to be introduced from 2013 to 2019 (

Financial Stability Board 2018). We consider regulatory capital arbitrage to be the main relation between regulatory authorities and banks. Those financial institutions seeking new opportunities of regulatory capital arbitrage might never come to an end, but it has become harder to continue with the maturity of regulations. Regulatory capital arbitrage is difficult to apply in loan securitization. Less regulatory capital could not result in moral hazard problems in securitization transactions before 2017Q4. However, banking regulators in China intensified capital rules in the three years prior to that; for example, banks that failed to comply with capital adequacy requirements by the end of 2010 in terms of the amount of capital they had to hold against their loans were punished, with limits on market access and so on (

McMahon 2009). Chinese regulators also drafted tougher capital rules for China’s too-big-to-fail banks, seeking to curb risks (

Bloomberg 2021). Regulatory capital arbitrage might have been applied in securitization transactions under the pressure of stricter capital requirements after 2017Q4.

7. Conclusions

In summary, by comparing two periods, FinTech applications in the banking industry could result in lower information asymmetry. However, moral hazard and adverse selection problems still affect the securitization market, which could affect financial stability. Thus, China needs a higher standard of information transparency.

The moral hazard and adverse selection problems were tested by studying the determinants of loan securitization in China’s banking sector. Specifically, risk exposure was the main determinant of securitization issues over the whole period, which means that the adverse selection problem might affect the securitization market. This result is similar to that of studies by

Minton et al. (

2004) and

Bannier and Hänsel (

2008). Liquidity and performance were considered to test moral hazards, and they were less statistically significant with respect to securitization issuance after 2017Q4. However, the capital requirement could be a main determinant of securitization. This conclusion is similar to that of studies by

Uzun and Webb (

2007) and

Ambrose et al. (

2005).

In order to protect against adverse selection and moral hazards, China needs a higher standard of information transparency. First, since adverse selection in securitization mainly affects risk transfer, information disclosure should focus more on the underlying assets to ensure that investors know what they are investing in and that they are willing to pay corresponding prices and bear the corresponding risks. The second recommendation regards moral hazards, which are mainly reflected in the capital requirement. Information disclosure should correspond more to regulatory capital arbitrage. The third is that a regulatory scheme of information disclosure should be diversified according to the varying types of bank. The last recommendation is to apply blockchain in securitization to further enhance their information transparency.