1. Introduction

In mid-2018, ING, the largest bank in The Netherlands, announced that it would be incorporating specific climate change criteria in its lending decisions. ING will structure its €600+ billion loan portfolio to meet the Paris Agreement’s two-degree goal. This means that future loans will be made based on how well borrowers’ operations and investments are structured to meet the Paris Agreement target. Companies that are making investments that progress reducing climate impacts will get financed. Meanwhile, those that aren’t making progress won’t get financed (or perhaps they’ll be forced to pay a higher interest rate).

This approach is innovative because it is forcing companies, including both ING’s customers and ING itself, to internalize externalities. ING’s strategic shift will force ING to change its operations and, in theory, will force large corporate borrowers to change their operations and investment behavior, too. Perhaps we’ve reached a point where companies, and the financial institutions that fund their investments, are recognizing that what had previously been long-term risks not worth accounting for in financial models have now become short-term risks that will have measurable effects on short-term cash flows. ING certainly seems to believe that we’ve reached this point.

ING is a private, for-profit company, listed on both the Amsterdam and New York Stock Exchanges. Its investors have short-term expectations, just like those of the companies ING lends to. This shift in ING’s lending strategy will impact ING’s cash flows and profitability, both in the short-term and the long-term. Presumably, ING is only making this shift because it believes it will have a positive effect on profitability, as it believes that the long-term benefits associated with lending based on climate change criteria will be greater than the short-term costs it may incur in doing so. As with all investments, only time will tell.

This study may provide some guidance. The purpose of this research is to analyze the effects that banks’ investments in corporate social responsibility (CSR) have on bank performance. In general, I find that banks’ investments in CSR have a positive impact on financial performance, measured in terms of both accounting performance and stock market value. Banks with better CSR performance have better financial performance. That is, ING’s new strategic shift towards basing its lending activities to how the loan contributes to the Paris Agreement goals should create financial value for ING.

However, this story has some critical context: not all CSR investments are the same. Banks make many different types of CSR-related investments, from donating to charities or sponsoring a local marathon to strategically shifting their loan portfolio to align with the Paris Agreement goals. In theory, these investments should have different impacts. Investors and other stakeholders are sophisticated enough to determine which investments may be focused on short-term image enhancement (or greenwashing) and which may be focused on long-term value creation. To determine this, I distinguish between internal CSR and external CSR. This distinction is generally based on which constituents are most directly affected by the CSR initiatives. As explained by

Hawn and Ioannou (

2015), internal CSR is aimed at achieving change within the organization, whereas external CSR is “aimed at gaining organizational endorsement by external constituents” that is more long-term focused. These classifications are an extension of stakeholder theory that considers different firm audiences: internal audiences, such as employees and owners, and external audiences, such as customers, suppliers, and government.

Banks represent an important sector to study within this framework for a couple reasons. First, as the ING example above shows, banks have the power to influence which companies get financed and what conditions may be tied to that financing. Thus, companies may be required to satisfy different constituents to improve their financing opportunities. Second, banks are for-profit companies, too. Banks also have internal and external constituents who get to influence the strategies the banks are employing and the investments the banks are making. Thus, separating bank CSR activities into internally focused and externally focused may provide some evidence on how different constituents value bank CSR activities.

Banks are also an important sector to study because of how different their business cycles are to those of traditional industrial or technology firms. For Apple and Caterpillar, their business and product life cycles last for months or years. For banks, their business life cycle may be significantly impacted by the bank’s next loan or next trade. Short-term actions can have a much more meaningful impact on the long-term performance of banks relative to traditional industrial firm. Thus, in addition to studying the impact on bank performance, I also consider how internal and external CSR activities influence bank risk.

Since the 2007–2010 financial crisis in the U.S. and Europe, substantial academic research has focused on the role that financial institutions played in that crisis, looking to establish what financial institutions should have done differently leading up to the crisis. Much of this work has focused on investment quality, corporate governance, executive compensation, and risk-taking. However, if banks were irresponsible with their operating and strategic activities, were they also irresponsible with other aspects of the firm?

One way to evaluate this is to consider a bank’s CSR environment. If bad investments, weak corporate governance, misaligned executive compensation and excessive risk-taking at financial institutions were the immediate causes of the crisis, it may have been because the banks’ CSR environments were sufficiently weak or misguided to allow these issues to be so problematic. CSR embodies many facets of an organization, including employee relations, diversity, human rights activities, harmful products, as well as corporate governance and compensation policies. These investments become part of a firm’s culture. They are shaped by the firm’s strategies, operations, and leadership. However, how these CSR investments affect bank performance and broader firm characteristics presents an open question. This study addresses this issue directly, looking at both bank performance and through several measures of CSR.

Using data from the KLD Research & Analytics (KLD) database from 1998–2016, this study shows that banks with stronger CSR environments have better financial performance and higher valuation, measured by return on assets and by Tobin’s Q, respectively (the KLD database is now known as MSCI ESG STATS, and I refer to it throughout this manuscript to be consistent with prior literature and because it was known as KLD throughout the majority of my sample period). Further, banks with stronger CSR environments also have less risk, measured by both Z-score and whether the bank received funding under the U.S. Treasury’s Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) in 2008–2009. In both the analyses related to bank performance and to bank risk, the benefits of CSR investments are driven by the banks’ external investments, focused on those stakeholders who are external to the bank (customers, borrowers, society) rather than those who are internal to the bank (employees, directors). This suggests that not all types of CSR initiatives have the same impact at banks and that these differences are realized in their financial results.

What are the implications of these findings? Even though it may seem like banks’ primary activities have only indirect effects on traditional CSR issues, such as product and environmental, investing in CSR both directly and indirectly has significant benefits for banks. These results show that the type of CSR that banks engage in matters. Investing in non-core CSR activities focused on internal stakeholders, that can possibly easily be reversed (akin to greenwashing), is not as beneficial as focusing on external stakeholders and core CSR activities that have direct effects on operations, such as community engagement, respect for customers and human rights activities.

The remainder of this paper proceeds as follows. A literature review and development of the key hypotheses are presented in the next section. The data and research design are presented in

Section 3. The empirical analysis and key findings are presented in

Section 4. Further, a summary of conclusions and key implications is presented in the final section.

2. Literature Review & Hypothesis Development

What makes financial institutions special? Why study their activities independently? Financial institutions are unique in many ways, from the retail services they provide to their role in enabling economic activity for corporations. They are also unique in how they have changed over the last few decades. In 1980, the finance sector accounted for approximately 4% of U.S. gross domestic product (GDP). By 2005, the finance sector accounted for nearly 8% of the U.S. GDP (

Philippon 2007), where it has remained through 2016. Most of this growth came from traditional depository institutions and commercial banks (

Philippon 2007). However, this growth also came from deregulation (e.g., The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act of 1999) and the subsequent innovation by financial institutions that led to securities such as collateralized debt obligations and credit default swaps. Initially, these innovative products were intended to help firms hedge balance sheet exposures or to diversify portfolio holdings. By the early 2000s, however, these products had become ways for banks’ proprietary trading departments to increase profits through speculation. Ultimately, this growth and innovation contributed to the financial crisis of 2007–2008, when many institutions had to be rescued by the U.S. government, trillions of dollars of wealth were lost, and the overall U.S. economy sank into a deep recession. Because the finance sector had become so important to the U.S. economy, and because problems within the finance sector can impact so many other aspects of the economy, studying the factors that can impact the finance sector is of critical importance.

The financial crisis, and any underperformance in financial institutions in general, can be seen as a failure of corporate governance.

Shleifer and Vishny (

1997) define corporate governance as that set of mechanisms the enable firms to provide a return on capital to the suppliers of capital. If the corporate governance environments were not optimally designed to benefit the institutions’ stakeholders, a logical extension is to ask if other aspects of the institutions’ corporate environments were properly designed. What about their corporate social responsibility (CSR) structures?

Carroll (

1979) defines CSR as encompassing the legal, ethical, economic, and other discretionary responsibilities that institutions have to society. When applied to individual firms, this is consistent with

Freeman’s (

1984) notion of stakeholder theory, which suggests that firms have a responsibility to a number of different interest groups, including employees, customers, suppliers, and society at large, in addition to stockholders. Given this, different firms may have different objectives and standards for performance, depending on who their stakeholders are. These different stakeholders should force firms to provide the greatest possible return to the specific capital that they have provided. Since this will include returns to shareholders, focusing on financial performance of firms, which is the most readily measurable source of returns, should provide the best proxy for the firm’s overall performance.

A considerable amount of research has studied the relationship between CSR and firm performance. In general, the empirical results show a positive relationship between CSR and firm performance; see

Griffin and Mahon (

1997) for a survey of the pre-2000s research. More recently,

Orlitzky et al. (

2003) perform a meta-analysis of CSR and performance studies and show this positive relationship.

Deckop et al. (

2006) provide a summary of much of the CSR-firm performance literature and also show a generally positive relationship between CSR quality and firm performance.

Shen and Chang (

2009) show that firms with strong CSR environments do not perform worse, and generally perform better, than firms with weak CSR environments across a variety of financial metrics. Using data compiled by KLD Research & Analytics, Inc. (KLD), Boston, MA, USA,

Anderson and Myers (

2007) find that investors are no worse off basing their investment decisions on CSR-related criteria that are consistent with their social beliefs.

El Ghoul et al. (

2011) find that firms with stronger CSR have lower costs of equity, lower firm risk, and higher overall valuation.

Cheng et al. (

2014) similarly show that firms with better CSR have lower overall capital constraints, indirectly leading to more opportunities for investment and higher valuations. Moreover,

Ferrell et al. (

2016) show that better governed firms invest more in CSR, and that investing in CSR increases firm value.

Other CSR studies have focused on more specific questions.

Barnea and Rubin (

2010) study the relationship between CSR investment and firm characteristics. They find that insiders are likely to over-invest in CSR initiatives when the personal benefits are high and the personal costs are low; this could be seen as a form of green-washing, or focusing on the style of CSR investment and not the substance. This over-investment is beneficial to the individuals but not to the firms.

Chahine et al. (

2019) find that CEOs with more centralized networks can use CSR as a means to entrench themselves at the expense of overall firm value, suggesting that more holistic and inclusive corporate governance structures are critical for increasing the effectiveness of CSR investments. This is further supported by the findings of

Ferrell et al. (

2016) that well governed firms enjoy less wasteful CSR, lower agency costs, and higher firm value through their CSR investments.

The previously mentioned work, however, has not studied the relationship between CSR and financial performance at banks. CSR at banks might be substantially different than CSR at non-bank enterprises, for many reasons. Banks’ products are paper (loans and investments), as opposed to physical products that may have positive or negative CSR attributes—such as clothing made with organic cotton, operations that use 50% less water than competitors, or above-average greenhouse gas emissions. Such observable metrics do not exist at banks. Banks’ CSR investments are largely determined by their operational practices—such as diversity of employees, profit-sharing programs, or transparency initiatives—and by the practices employed by their customers and clients. As such, many of their CSR investments are more indirect than they might be a non-bank enterprises. The example of ING at the beginning of this paper highlight this distinction; what makes the ING initiative so unique is that it is explicitly incorporating CSR-filters into its operations (its lending). ING’s products only have a CSR impact through ING’s customers and what they ultimately invest in with their ING-provided loans. This linkage makes CSR much different at banking institutions than it is at non-bank enterprises.

Thus, it is imperative that we learn more about how banks do invest in CSR and what the implications of such investments are. However, only a few studies have even touched the issue. In one of the few studies to consider CSR at financial institutions,

Ahmed et al. (

2012) show a positive, although insignificant, relationship between operating performance and CSR for a very small sample of banks in Bangladesh.

Wu and Shen (

2013) find that strategic choice is the primary motivation for banks to invest in CSR, as opposed to either altruism or greenwashing; their study of 162 banks across 22 countries shows that higher CSR leads to higher financial performance during 2003–2009.

Goss and Roberts (

2011) look at the interest rates banks charge their clients; they find that clients with greater CSR concerns ultimately pay 7–18 basis points more than clients without CSR concerns, suggesting that banks should be able to influence non-bank behaviors. However, in this area, clearly more needs to be done. Altogether, most of this prior research suggests a positive relationship between CSR and firm performance; given that most of this work has focused on U.S.-based firms, it should have relevance to the sample of U.S.-based banks in this study.

Recently,

Hawn and Ioannou (

2015) formed the basis for the distinction between internal and external CSR. They show that investing in CSR is not just about the money spent or the specific activities chosen, but impact is about employing an integrated CSR strategy that focuses on both internal and external constituencies. They show that a large CSR gap arises where the (absolute value of the) difference between internal and external CSR investments is due to the company not having an integrated and/or mission-driven CSR strategy. Thus, when the CSR gap is large, there can be inconsistent and haphazard implementation of CSR investments. The result is abnormally poor performance: they show that firms with a larger CSR gap are valued less than firms with a smaller CSR gap. I apply this theory to financial institutions in the current study: the efficacy of a bank’s CSR strategy should be a function of the bank’s commitment to the strategy and how well that strategy is integrated into the bank’s overall strategic and operational decisions. Thus, for banks, just as for all firms in the

Hawn and Ioannou (

2015) study, a larger CSR gap should be indicative of a less refined and integrated CSR strategy.

Collectively, this prior literature motivates the first hypotheses regarding financial performance of banks:

Hypothesis 1. Banks with better CSR perform better than firms with weaker CSR.

Hypothesis 2. Banks with a smaller CSR Gap perform better than firms with a larger CSR Gap.

Scholtens (

2009) surveys CSR at more than 30 financial institutions from 2000–2005. He finds that CSR improved at these banks during this period. He shows that CSR is getting more important at banks, as they take on new CSR-focused perspectives, such as becoming involved in micro-lending, financing sustainable development, and performing environmental risk analyses before lending.

Nizam et al. (

2019) focus on the access to finance for banks and find a positive relationship between CSR and financial performance, driven by loan growth and management quality. This suggests that not only are banks engaged in diverse CSR activities, but that CSR issues are becoming more ingrained into the cultures of financial institutions.

A corollary of Hypothesis 1 is that the type of CSR that banks pursue matters. As mentioned above,

Barnea and Rubin (

2010) show that managers are likely to over-invest in CSR activities when the private benefits outweigh the private costs. They find that increasing expenditures on CSR may enhance their individual reputations as good citizens, but there are diminishing marginal returns to CSR such that additional expenditures decrease firm value.

Sigurthorsson (

2012) discusses the relationship between CSR and the collapse of the three largest banks in Iceland in 2008, where CSR was little more than public relations and philanthropy. As a result, the superficial nature of their efforts created a false sense of security and trust in the banks, which led to grossly irresponsible business practices (and ultimately to the failure of the banks). These studies suggest that not all types of CSR investment are created equal.

Hawn and Ioannou (

2015) formalize this idea by distinguishing between internal and external CSR investments and showing that firms with the most balanced and well-integrated CSR investments, as demonstrated by a smaller Gap between internal and external CSR investments, are the most valuable.

Since the financial crisis, many studies have tried to determine the role that risk played in the ultimate performance of banks.

Fahlenbrach and Stulz (

2011) find that the executive compensation and ownership structures at 100 U.S. financial institutions did not lead to those institutions taking excessive risks that may have led to inferior performance.

Gande and Kalpathy (

2017), however, do find that inappropriate compensation structures led to banks having too much risk; firms with the greatest pre-crisis risk-taking incentives borrowed the most from the U.S. Federal Reserve during 2008–2009.

Bhagat et al. (

2015) show that bank size was positively correlated with bank risk for a large sample of banks during the 2000s. More generally,

Houston et al. (

2010) show that banks with greater creditor rights have greater bank risk, while banks with greater information sharing have less risk, thus reducing the possibility of a financial crisis.

Jo and Na (

2012) study risk from a slightly different perspective: they look at risk for firms with controversial activities versus firms with fewer such activities and show that the strength of a firm’s CSR environment leads to greater risk reduction for the controversial firms.

Cai et al. (

2012) find that strong CSR environments are also associated with greater value enhancement for firms with controversial activities. While these two studies were not related to the banking industry, per se, they do show that CSR can affect different types of firms in different ways that might persist within a specific industry. Combining these two results shows that CSR can be important for different classes of firms and ultimately leads to what stakeholders care about most: reduced risk and increased value.

With respect to the financial crisis and bank CSR activities, most of the work has been on the ethical issues associated with the crisis.

Donaldson (

2011) discusses the notion of ‘paying for peril,’ or rewarding short and suffering long, and concludes that “business leaders must now push for new reward schemes that reflect long-term firm risk by paying over a longer term.”

Boddy (

2011) suggests that the financial crisis was probably caused by directors and executives who were focused on their own greed and self-serving at the expense of the long-term sustainability of the firm, consistent with

Donaldson’s (

2011) application of ‘paying for peril.’

Zeidan (

2012) finds that U.S. financial institutions that commit legal violations suffer large and significant negative stock market reactions due to these violations.

Bass et al. (

1997),

Sarre et al. (

2001),

Deckop et al. (

2006), and others find firms that improve their ethical and CSR standards beyond legal minimums have lower risks and stronger operating performance. This is evidence that stakeholders punish firms for operating in irresponsible ways and in ways that exposes the firm to excessive and unnecessary risks.

Just as a smaller CSR gap is indicative of a greater commitment to CSR that leads to superior financial performance, the same logic can be applied to bank risk. A larger CSR gap can be the result of an inconsistent commitment to CSR investments. This inconsistency in CSR investments may be representative of the bank’s overall commitment to executing strategic and agendas. Consistent with

Hawn and Ioannou (

2015), a larger CSR gap would be consistent with greater firm volatility and risk due to this lack of commitment to an integrated CSR strategy.

This prior literature, in addition to the lack of research focused on the relationship between CSR and risk, motivate the second hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3. Banks with stronger CSR are less risky than banks with weaker CSR.

Hypothesis 4. Banks with a smaller CSR Gap are less risky than banks with a larger CSR Gap.

Prior research has used a variety of measures of risk as there is not an agreed upon ‘best’ proxy for risk.

Aebi et al. (

2012) consider the internal risk management structure of the bank;

Gande and Kalpathy (

2017) focus on needing financial assistance; and

Houston et al. (

2010) and

Bhagat et al. (

2015) focus on Z-Score, as a proxy for financial distress. This study considers bank risk from two perspectives. The first test of Hypotheses 3 and 4 consider the general risk-taking by banks and the potential for financial distress using a Z-Score. The second test of Hypotheses 3 and 4 considers the outcome of this potential risk-taking and financial distress by looking at whether the banks needed financial assistance from the U.S. Treasury through its Trouble Assets Relief Program (TARP) in 2008–2009.

5. Conclusions

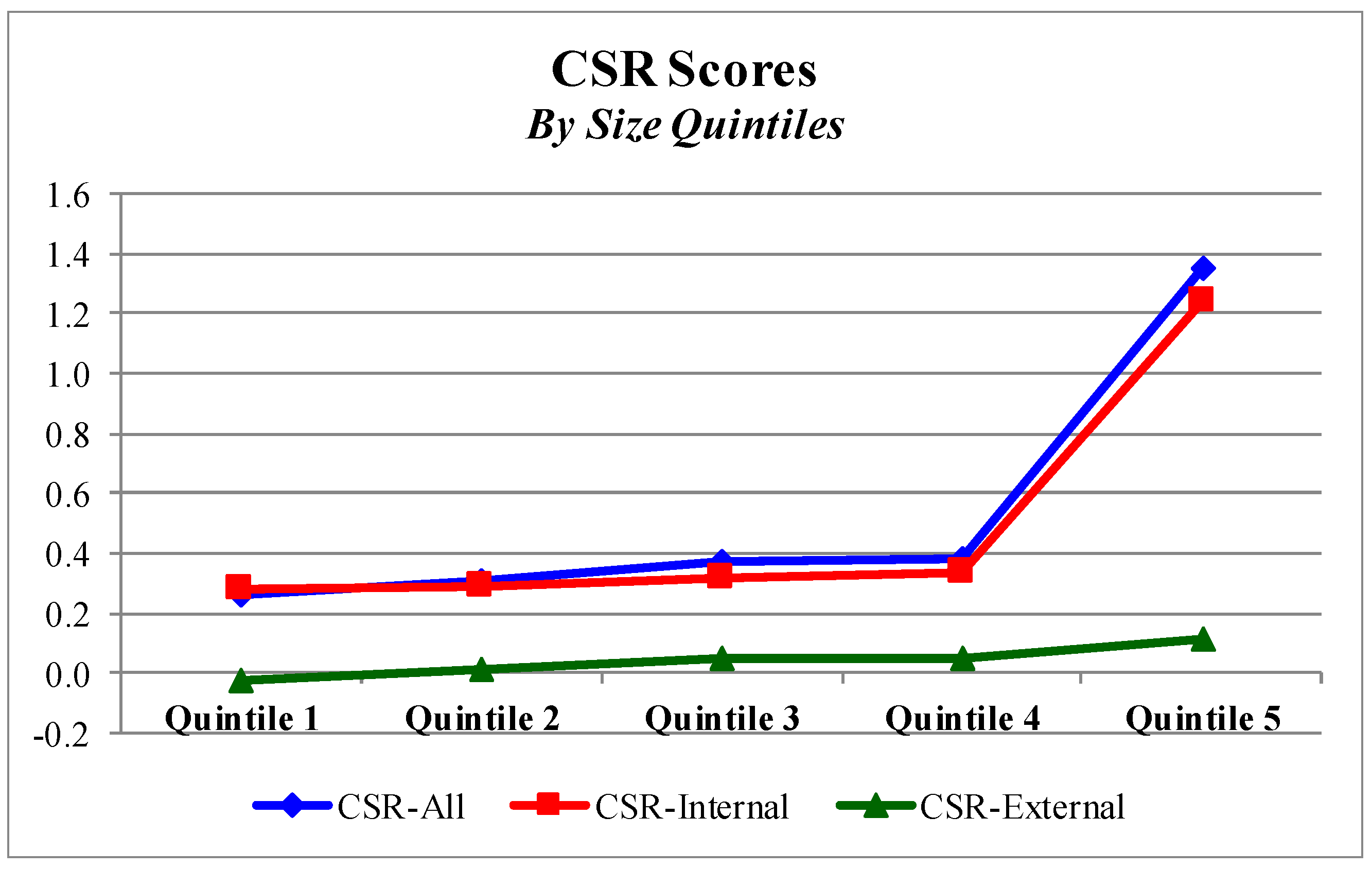

This study analyzed the relationship between CSR, financial performance, and risk-taking for a large sample of U.S. banks during 1998–2016. The results consistently show several key contributions. First, there is a positive relationship between total CSR and financial performance, measured with both operating performance and firm value. Second, it seems that the types of CSR activities the firm invests in do make a difference. A decomposition of the results shows that the superior performance and firm value are being driven by the bank’s CSR activities that are related to external stakeholders as opposed to internal stakeholders. Because banks’ external CSR investments are likely to be more focused on long-term effects, this is consistent with the notion that internal CSR investments—at banks especially—are similar to greenwashing. These two performance-related results were most significant for the largest firms and all results are robust to controls for endogeneity and bank size. Third, there is also a negative relationship between total CSR investments and external CSR investments and the amount of risk a bank is subject to. Further, the balance between internal and external CSR investments is also of critical importance: performance is better and risk is lower when there is a relatively small gap between a firm’s internal and external CSR investments. The implication is that the types of CSR investments that banks made mattered more than the amount of CSR investments. Finally, when we consider the relationship between CSR and an individual bank’s perceived systemic risk, banks with the weakest CSR structures were the most exposed to needing to be bailed out by the U.S. government.

It is important to note that, as with any empirical study, this work does have a number of limitations. First, measuring CSR and sustainability is inherently difficult. I have chosen to use the KLD ratings because they have been around the longest and have ratings to the largest number of banks in my sample. However, the KLD ratings are fundamentally different from ASSET4 used by

Hawn and Ioannou (

2015) and others.

Semenova and Hassel (

2014) show that the two ratings methodologies are highly correlated although they never fully converge. Further, just as with

Hawn and Ioannou (

2015), determining whether an issue is “internal” or “external” invariably requires some subjectivity. While I tried to follow their methodology as closely as possible, it is likely that there were some issues that were mis-classified. While this is both unavoidable and unfortunate, it should bias against finding the significant results that I do find. In addition, the sample in this study is limited to U.S. banks; whether or not the results and practical implications apply to other banking regimes is a matter for future research. Finally, it is always difficult to parse out managerial expectations in an empirical panel-data study such as this. It is possible that managers will alter their CSR investments based on how they perceive investor expectations; such expectations might make identification difficult in the empirical models which would bias the analytical results (see

Mackey et al. 2007). Further,

Schuler and Cording (

2006) discuss how “information intensity” of CSR activity might bias investors’ perspectives of the value of CSR investments for any firm. By using a financial statement-based measure of performance, this study might abstract away from undue influence of investor expectations on financial performance. Hence, I have tried to control for reverse causality and strict exogeneity with the endogeneity tests in

Section 4.3. However, it may be difficult to control for these concerns entirely in large-sample, panel-data studies. Future research might consider using clinical analysis of smaller samples or possibly event studies for additional perspectives on the relationships between CSR and financial performance over extended periods of time.

However, despite any limitations, the findings in this study do suggest that CSR does matter for banks, in terms of both individual firm performance and risk concerns. Banks would be well-advised to improve the CSR environments in meaningful ways, focusing on long-term investments that impact external stakeholders. However, ignoring internal stakeholders is a sign that the bank is not consistent or strategic with its CSR investments, so a bank would be well-advised to work for a balance between internal and external CSR investments. Banks do not appear to benefit by making superficial CSR investments that are not related to their core businesses. Greenwashing does not pay for them. Given the recent financial crisis and the notion of banks being systemically important, any improvements in the banks’ CSR environments that lead to stronger performance and less risk should lead to more positive sustainable economic impact.