Abstract

Corporate finance research focuses on C corps (CCs) neglecting pass-throughs (PTs). We answer this neglect by examining PT outputs for the categories of debt choice, valuation, and leverage gain. In the process, we expand on the nongrowth PT research and supplement the recent CC research on the same outputs. Before the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) became effective in January 2018, PTs had an after-tax valuation advantage over CCs. Under TCJA, we demonstrate this advantage has been reverse. This suggests that, ceteris paribus, a typical PT can now find it advantageous to switch to the CC ownership form. More importantly, we show that nongrowth firm values are comparable to growth firm values unless we assume a rise in growth consistent with projections under TCJA where tax rates are lower. We demonstrate this projected growth increase is the key to make businesses more profitable. Additionally, we show PTs achieve optimal debt-to-firm value ratios (ODVs) well below those for CCs; PTs generally attain slightly higher quality credit ratings at their ODVs compared to CCs; and, PTs have lower leverage gains outputs (in the form of the maximum gain to leverage and the percentage increase in unlevered firm value) compared to CCs.

JEL Classification:

C02; G32; G35; K20; O43

1. Introduction

Compared to C corp (CC) research, the study of the pass-through (PT) ownership form is a neglected area, given that taxation models focus on the corporate debt tax shield for CCs. For example, Henrekson and Sanandaji (2011) state that the literature on firm taxation has not sufficiently considered the taxation of owner-managed firms. The latter firms are characterized by the sole proprietorship ownership type, which is the largest ownership type among PT types. The purpose of this study is to overcome this neglect through a detailed examination of PT outputs for the three categories of debt choice, valuation, and leverage gain. In this study, we compare these categories of outputs for PT with those for CCs. This comparison is particularly important given the changes in tax laws caused by the Tax Cuts and Job Acts (TCJA) that was passed by the US congress on 22 December 2017, where most changes became effective on 1 January 2018. TCJA altered tax rates and brackets in a manner that favors CCs more than PTs. In response to this tax legislation, this study’s first major goal is to examine the decision as to whether PT managers should switch to the CC ownership form. Since a reason for TCJA was to increase growth, this study’s second major goal is to test the influence of projected increases in growth on the two for-profit business forms of PTs and CCs.

To achieve our major goals, we explore the following research questions. What can we say about PT outputs for the three categories of debt choice, valuation, and leverage gain for two tax environments, namely, pre-TCJA and TCJA? What can we disclose about these PT outputs for conditions of nongrowth and growth within the two tax environments? What can we tell a typical PT manager about its optimal credit rating (OCR) and how this rating might change when favorable tax laws are enacted causing greater business growth to occur? How do the findings of our PT tests compare to the findings of the same CC tests and what does this comparison tell us about the most profitable ownership form? Answering these questions are crucial for managers who are charged with determining the capital structure mix that maximizes firm value, choosing the best ownership form, and understanding the impact of lower taxes on growth.

To answer our research questions, this paper uses the Capital Structure Model (CSM) that was recently extended by Hull (2019) to incorporate PT equations within a framework that formerly only addressed CCs. By using the CSM, we avoid measurement problems found in agency models (Jensen and Meckling 1976; Jensen 1986) and pecking order models (Myers 1977; Myers and Majluf 1984). We also circumvent inherent problems in the tax-based models of Modigliani and Miller (1963), Miller (1977) that fail to fully incorporate the costs of borrowing as factors influencing the gain to leverage (GL). The CSM formulations for GL include borrowing costs that increase with debt and allow for identification of the maximum GL (max GL) and thus the maximum firm value (max VL), since max VL equals max GL plus unlevered equity value.

The CSM is also chosen because, in examining the current state of the corporate finance field, we find it contains the only equation that ties together the debt-equity and plowback-payout decisions. The CSM does through its innovation of the levered equity growth rate (gL), which is a function of interest payments and earnings retained for growth. This innovation allows us to test different historical and future projected annual growth rates for the same target credit rating. In this paper, we test three annual growth rates. First, we test a historical sustainable growth rate of gL = 3.12%, which is consistent with the annual compounded growth in real US GDP for the 70 years prior to TCJA with GDP data supplied by the US Bureau of Economic Analysis (2020). This usage assumes GDP is a result of the growth in businesses and, in particular, in the risk-taking residual equity ownership of businesses. Second, we test gL = 3.90%, which is consistent with the Tax Policy Center, TPC, (2018) that cites sources predicting that TCJA, on average, will increase GDP by about 0.8%. Thus, and as also pointed out by Hull (2019), a gL of 3.90% is consistent with a growth rate of 3.12% increasing by about 0.8%. Third, we test gL = 4.50%, which represents the two growth projections given by TPC that are at the high end. In regard to these two high end projections, TPC reports that the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates the effect of TCJA will be an increase of 0.7% per year in GDP for the next ten years, while the Tax Foundation Taxes and Growth model projects an increase of 2.1%. The average of these two rates is 1.4%. This suggests a rate of about 4.50% when 1.4% is added to the long-run growth in real US GDP of 3.12% that occurred prior to TCJA. While these are projections for only ten years due to possible termination of certain TCJA provisions (especially for PTs), our tests assume permanency in these provisions. Unlike other key provisions, the drop to a flat corporate tax rate of 0.21 caused by TCJA (where the former maximum tax rate for CCs had been 0.35) is not set to expire.

Besides the growth rates just described, our tests rely on government, market, and financial data. In terms of the latter, Damodaran (2020) most recently supplies credit spreads (based on credit ratings) matched to interest coverage ratios for the year 2019. As shown by Hull (2020), Damodaran’s data is useful for computing costs of borrowings associated with debt choices. Because our main tests use spreads for 2019, the results for these tests are subject to time-dependence, since spreads can change from year to year. Thus, we also report (when relevant) results from robust tests using spreads for 2017 and 2018. Due to disagreement about effective tax rates found in the literature, our robust tests also include conducting tests focusing on lower effective tax rates. Given the above, we now describe our major findings in terms of the outputs for the three categories of debt choice, valuation, and gain to leverage where these outputs are best viewed as those for a typical or average business.

First, in terms of debt choice outputs, we find similar optimal debt-to-firm ratios (ODVs) for all PT tests, namely, pre-TCJA, TCJA, growth, and nongrowth. ODVs for PTs have a narrow range from 0.2226 to 0.2499 with an average of 0.2377. This contrasts with a higher CC range from 0.4132 to 0.4609 with an average of 0.4416. However, robust tests indicate the ODV gap is narrower than what we report from our main tests. ODVs for PTs occur at a debt choice that generates a Moody’s credit rating of A3, which is an upper medium investment grade rating. The lone exception is the 4.50% growth rate test where the rating is Baa2, which is a lower medium IG rating. The larger ODV outputs for CCs lead to a rating of Baa2 for all tests, which is a slightly lower quality than typically found for PTs. Robust tests verify our credit rating findings but can produce occasional disagreements with our main tests. We conclude:

ODVs for PTs are smaller than CCs and typically come with a slightly higher quality rating.

Second, in terms of firm valuation outputs (where all firm values are after-tax values), we find the following. Whereas higher firm values are expected under TCJA with lower taxes, we show the precise valuation differences when compared to pre-TCJA firm values. To illustrate this preciseness, consider the pre-TCJA and TCJA max VL outputs when growth is 3.12%. For each $1,000,000 in before-tax cash flows, we find max VL for a PT is $10.390 M (M = million) for the pre-TCJA test and $10.758M for the TCJA test. For CCs, max VL is $9.476 M for the pre-TCJA test and $11.413M for the TCJA test. Whereas the increase in max VL for PTs is only 3.54% due to TCJA, the increase for CCs is 20.44%, which reflects the more favorable tax treatment for CCs under TCJA. When we compare pre-TCJA nongrowth max VL and growth max VL using a growth rate of 3.12%, we find that the PT growth max VL is slightly greater. In contrast, the pre-TCJA nongrowth max VL for CCs is comfortably larger than its pre-TCJA growth max VL. The latter outcome occurs because high CC tax rates in the pre-TCJA environment made internal growth unaffordable for a typical CC as internal funds (retained earnings) faced a high pre-TCJA corporate tax rate. When we repeat this comparison using the lower tax rates under TCJA for CCs, we now find the growth max VL is greater than the nongrowth max VL. When we test greater growth rates of 3.90% or 4.50% that are projected to occur under TCJA, we find the growth max VL outputs for both PTs and CCs are now much greater than those for nongrowth. We show that the average pre-TCJA max VL from all PT tests is $10.380 M, which is greater than the average of $9.754 M found for CCs. However, under TCJA, we find this advantage for PTs is reversed, as the average max VL of $11.802 M for CCs is greater than that of $11.163 M for PTs. This advantage slightly rises if we repeat our tests and use spreads for either 2017 or 2018 but lessens if we test lower effective tax rates. We conclude:

CC firm valuation increases by much more than PTs under TCJA with one reason being that the relative lower tax rates under TCJA for CCs makes growth more affordable for CCs compared to PTs. This increase makes switching from a PT to a CC profitable under TCJA. If growth increases as projected under TCJA, PTs and CCs will both profit substantially.

Third, with regard to leverage gain outputs, we find the following. First, PTs have lower maximum gain to leverage (max GL) values compared to CCs. Second, PTs also have lower values for the maximum percentage increase in unlevered equity (max %∆EU). Third, whereas PTs have lower values for the net benefit from leverage (NB) for the two pre-TCJA and nongrowth TCJA tests, we find that PT have greater NB values for the three TCJA growth tests, indicating that PTs add more value per dollar of new debt for TCJA growth tests. The values for leverage gain outputs can change as annual spread data changes. Robust tests using spreads for 2018 and lower tax rates generate lower values. The lower values for max %∆EU are consistent with empirical research. We conclude:

While the superiority of PT compared to CCs depends on the leverage gain output being analyzed, CCs generally perform much better in the category of leverage gain outputs indicating greater gains from leverage compared to PTs.

The remainder of this paper is as follows. In Section 2, we overview the literature related to ownership form, financing, and the effective tax rates. Section 3 presents our research methodology used to produce outputs. This methodology is a trade-off model called the Capital Structure Model (CSM). Section 4 provides the procedure to get credit spreads, ratings, and costs of borrowing matched to debt-to-firm value ratios (DVs); gives the procedure to determine optimal outputs; presents introductory variables and computations used by the CSM; and, offers PT applications of the CSM that showcase outputs at ODV for nongrowth and growth tests under TCJA. Section 5 provides figures that display GL and VL results for PTs when plotted against respective DVs and credit ratings. Section 6 gives results pertaining to optimal outputs for PTs and CCs, provides policy implications, and suggests possibilities for future research. Section 7 offers a summary.

2. Literature Review

This section provides a review of for-profit ownership forms, equity and debt financing, and effective (average) tax rates used in this study.

2.1. Ownership Forms

A sole proprietorship is the most common business type for the pass-through (PT) ownership form. Other types include partnership (general or limited), limited liability company and S corp. While most PTs are small, they can also be large, global enterprises. Prior to the Tax Cuts and Job Acts (TCJA) that took effect in January 2018, PTs were viewed as having, on average, an after-tax valuation advantage over C corps (CCs). This valuation advantage was reflected in the choice of ownership form. For example, as noted by Hodge (2014), CCs had shrunk in number since the 1980s while PTs had tripled so that they outnumbered CCs by about 18 to 1. However, with the large drop in the corporate tax rate from the maximum rate of 0.35 to a flat rate of 0.21 under TCJA, the continuance of the forty-year trend of increasing the proportion of the PT ownership form is in jeopardy.

Since TCJA, much has been written on PT switching its ownership form to a CC. For example, Robert (2019) writes about the advantage of an LLC switching to a CC, while Houston (2019) discusses the advantage of an S corp converting to a CC. Regardless of the PT type considering conversion to a CC, Grant Thorton International Ltd. (2019) notes that a crucial PT consideration for converting to a CC under TCJA is how much taxes will be paid on corporate earnings and equity dividends compared to what the PT pays in taxes at its personal level. In regard to this consideration, this study offers insight on the conversion of the PT ownership form to the CC form by computing after-tax firm valuation for pre-TCJA and TCJA tax environments.

Another factor in conversion to a CC is that PT owners get a temporary twenty percent standard tax deduction on income under $315,000, if married filing jointly, or $157,500 for all other filing statuses. Even for PTs that earn below these limits, there are restrictions on who qualifies and questions as to if this deduction will last past 2024. Finally, as noted by numerous tax service companies, switching ownership forms is often more than just saving taxes. However, as suggested by Grant Thorton International Ltd. (2019), the savings on taxes will arguably be the paramount factor for most PTs that are considering switching to a CC.

2.2. Financing Forms

Pass-throughs, like all for-profit businesses, rely on the two basic financing forms: equity and debt. Compared to CCs, PT financing manifests differences. One area of difference involves the legal treatment. For example, consider partnerships where the Tax Foundation (2019) reports that they account for 55.3% of PT net income. Dantzler (2017) notes that the distinction between equity and debt financing within the partnership framework is often blurred because there is much less law in the PT world for partnerships compared to CCs. Dantzler’s observations suggest that, at least for PTs that are partnerships, computing PT leverage ratios can be a difficult undertaking. However, there is also a difficulty in computing leverage ratios for CCs that use preferred stock as a form of financing. The difficulty lies in the fact that preferred stock is a hybrid security with both equity and debt features. While preferred stock is classified as equity, its dividend payment is recognized, like interest payment, as a highly prioritized payment.

Another area of difference involves the investor clienteles that inhabit different for-profit ownership forms. For example, unlike many CCs that issue equity shares involving thousands of individuals and institutional investors, PTs often rely on a small number of investors (partners or venture capitalists) as their most common source of equity funding. Although some question the wisdom of government participation (Florida and Smith 1993), venture capitalists can also include government entities. Smaller PTs (like the sole proprietorship type) can get debt financing by simply using a credit card or, like all businesses, acquiring some form of trade credit. Like CCs, larger PTs can take on debt by issuing notes, bonds, and other obligations. As noted by Hull and Price (2015), while large CCs can float large bond issues and undertake a variety of large short-term borrowings, PT debt financing often includes regional and national mezzanine borrowings that permit the issuance of unsecured and subordinated notes at high interest rates. Hull (2019) writes that PTs can also borrow from individuals, banks, savings and loans, credit unions, commercial finance companies, and Small Business Administration (SBA) guaranteed loans where the latter have methods of encouraging bank and non-bank lenders to make long-term loans to PTs. Compared to CC debt, PT debt is less likely to be assigned a credit rating by a major credit rating company.

Arguments can be offered that debt is less valuable for PTs compared to CCs. For example, PTs are more likely to be smaller owner-managed enterprises where the owner and manager functions are joined. This situation avoids principal-agent conflicts between owners and managers found in larger entities where many managers are not primary owners and so have interests that are different from the residual equity owners (Jensen and Meckling 1976). This means debt can be more valuable to equity owners in larger firms (most often CCs) because interest payments limit the available cash flows that can be wasted by self-serving managers (Jensen 1986). In addition, PTs are less likely to raise equity funds with negative signaling as accompanies large public offerings of equity where the company is suspected of issuing overvalued securities (Masulis 1983; Asquith and Mullins 1986). Thus, negative signaling for large public equity issues (mostly by CCs) can serve to make debt more valuable by issuing debt to avoid the negative signaling from an equity issuance. In conclusion, we can find arguments that suggest CCs should have higher leverage ratios compared to PTs. As will be seen, these arguments are consistent with this study’s findings.

PTs, like CCs, are subject to market conditions so that tests can be conducted base on different market risk scenarios affecting cost of financing. While this paper does not look at different market risk scenarios like prior PT research (Hull and Price 2015), we do implicitly assume there are risk classes of PTs that are similar to CCs. In particular, the tests we conduct assume that PTs and CCs have a risk class resembling the market as the optimal leverage ratio occurs near the market beta of one for all of our tests. This risk class generates the same costs of borrowings for equity and debt financing for both PTs and CCs. These borrowing costs are tied to credit spreads and ratings but achievable at different leverage ratios based on the firm’s size classification (as described in Section 4.1). With the same costs of borrowings matched to the same credit ratings, differences in our PT and CC outputs revolve around discrepancies in leverage ratios (based on size) and dissimilarities in tax rates (based on the ownership form).

2.3. Effective Tax Rates

We now describe what we mean by an effective tax and then discuss the assignment of tax rates used in our tests.

2.3.1. Effective Tax Rate Described

For a PT owner, who is an individual income tax filer, the average tax rate is total personal taxes paid divided by taxable income. An average personal tax rate can also be defined in terms of taxes paid divided by variables other than taxable income. Such variables include gross income (GI), adjusted gross income (AGI), or modified AGI (MAGI). The latter three variables represent amounts larger than taxable income. Thus, an average personal tax rate defined in in terms of these three variables will be lower and so a researcher must be aware of the differences when reviewing sources to ensure consistency in estimating an average personal tax rate.

For a CC, the average corporate tax rate is corporate taxes paid divided by taxable income where the accounting term, earnings before tax (EBT), is commonly used for a CC’s taxable income. The federal corporate tax rate under TCJA is a flat rate of 0.21 (the pre-TCJA maximum was 0.35). Besides corporate taxes, CC owners pay personal taxes on debt income and equity distributions where the latter is EBT minus corporate taxes. Debt income comes in the form of interest (where more interest leads to a lower EBT) and capital gains for debt owners that are subject to taxation at the PT or personal federal tax rate with a TCJA maximum of 0.37 (the pre-TCJA maximum was 0.396). However, if debt is held more than one year, capital gains are subject to federal tax rates of 0, 0.15, and 0.2 with a 0.038 investment tax added if MAGI exceeds certain thresholds. Equity distributions are dividends and capital gains. Qualified dividends (which are stocks held at least 60 days) are subject to the same federal tax treatment as capital gains for equity and debt. Otherwise, dividends for CCs are taxed like PT personal business income with the TCJA maximum of 0.37. In conclusion, the total taxes paid by CCs can differ from PTs because CC earnings are taxed twice, albeit almost always at lower maximum tax rates at both the corporate and personal levels compared to PTs that are taxed only once on its taxable income.

In keeping with common usage, this paper refers to an average tax rate as an effective tax rate where, for our purposes, the effective tax rate includes only federal income taxes thus ignoring other taxes paid that a for-profit business often incurs such as state, city, county, sales, property, unemployment, social security, and Medicare. Inclusion of other taxes paid lead to a higher effective tax rate. Unless a flat federal tax rate is operative, the use of a marginal federal tax rate will also lead to a higher tax rate as income climbs until it reaches the maximum statutory rate. This is because a marginal tax rate reflects the dollars of taxes paid at the highest statutory rate after all prior dollars were taxed at lower rates. Thus, unlike the use of GI, AGI, or MAGI that lead to a lower tax rate, the addition of other taxes paid or the use of a marginal tax rate will lead to higher tax rates.

2.3.2. Effective Tax Rates for Main Tests

For our tests, we allowed tax rates to change in their predicted direction given by Hull (2014) for increasing P choices where a P choice refers to the proportion of unlevered equity (EU) retired with debt (D). Hull argues the corporate tax rate (TC) and the personal equity tax rate (TE) decrease with greater debt-for-equity transactions while personal debt tax rates increase. While Hull’s original arguments were for a CC, they are applicable to PTs since TE for PTs moves in the same direction as both TC and TE for CCs. However, TE for PTs is more akin to TC for CCs as both are business tax rates on net income, whereas the TE for CCs is the rate on equity payouts in the form of dividends and capital gains. For our tests, we used a 0.03 change in tax rates for each of the fifteen increasing P choices where each P choice corresponds to one of the fifteen Moody’s ratings used by Damodaran (2020). As described below, the use of 0.03 in conjunction with the setting of unlevered tax rates achieved effective levered tax rates that we expected to occur at the optimal debt-to-firm value ratio (ODV).

From federal data supplied by the Tax Policy Center (2016) on the distribution of PT business income for 2016 (where the maximum TE is 0.396), an effective TE for a pre-TCJA tax environment can be estimated at of 0.32. However, earlier sources (SBA 2009; National Federation of Independent Business 2013) suggest an effective TE that would be below 0.32 with variations based on the pre-TCJA years examined. Given this information, we selected an effective TE of 0.30 at ODV for pre-TCJA tests. Given this pre-TCJA estimate, a TCJA approximation for an effective TE at ODV would be about 0.28 due to the slight fall in personal tax rates caused by TCJA. Because we begin with an unlevered firm and allow tax rates to change when debt increases as described by Hull (2014), our pre-TCJA tests start with an unlevered TE of 0.35. This starting point enables us to achieve as an effective levered TE that is near 0.30 at ODV for pre-TCJA tests. For TCJA tests, we started with an unlevered tax rate of 0.33 to attain an effective levered TE that approaches 0.28 at ODV.

The Tax Foundation (2014)reveals the effective TC ranges from about 0.24 to 0.34 for a ten-year pre-TCJA period from 2001 through 2010. This suggests an effective TC of about 0.29 for the pre-TCJA tax environment. To achieve this rate, we set an unlevered TC at its maximum statutory rate of 0.35. The maximum corporate tax rate (TC) under TCJA is 0.21, which is also its minimum since 0.21 is a flat rate. Given that the estimated effective TC of 0.29 is 0.06 under the pre-TCJA maximum TC of 0.35, a value with the same drop of 0.06 in a TCJA environment would be 0.21 − 0.06 = 0.15. However, a proportional fall would be (0.29/0.35)0.21 = 0.174. Considering that TC is a flat rate under TCJA and tax credits and deductions may be more difficult to attain under TCJA, we considered an effective TC near 0.18 at ODV to be more reasonable and could be achieved with an unlevered TC of 0.21. As noted by Hull (2020) for his CC study under TCJA, an effective TC of 0.18 is consistent with the estimate of 0.18 given by the Penn Wharton Budget Model (2017) under TCJA. As described next, our tax rates on debt and CC equity income under TCJA were also consistent with Hull (2020).

Interest distributions for debt owner are taxed at the personal debt tax rate (TD) for both PTs and CCs where TD has a pre-TCJA maximum of 0.396 and a TCJA maximum of 0.37. If debt is held longer than three years, any capital gains is taxed at a lower capital gains rate where the typical maximum TD is 0.2. However, as noted by Hull (2020), wealthier investors often avoid paying taxes on for-profit debt by investing in nontaxable bonds because the taxable equivalent yield is higher. Given the above, we set TD at 0.22 as a reasonable effective tax rate for a typical PT or CC debt owner under a pre-TCJA tax environment. Under TCJA, we expect a slightly smaller TD and so set an effective TD at 0.21 as does Hull (2020). Unlike TC and TE that fall with leverage, TD rises with leverage. Thus, to achieves effective TD values near 0.22 and 0.21 at ODV, we set unlevered TD values at 0.19 and 0.18, respectively, for pre-TCJA and TCJA tests.

Unlike PTs, most CCs have many investors who buy and sell public shares and receive dividends and capital gains. These investors are subject to different personal tax laws on equity income than PT owners. For CC investors who buy equity and receive qualified dividends and capital gains, the maximum TE is typically only 0.2 and not the much higher personal statutory maximum for PTs. As mentioned by Hull (2020), investors have the ability to defer capital gains so that, through charitable contributions and inheritance, TE can be zero. For this reason, we advocate an effective personal tax rate (TE) on dividends and capital gains of about 0.14 for CC owners. To achieve an effective TE near 0.14 at ODV, the unlevered TE is set at 0.165. This rate holds for both pre-TCJA and TCJA tax environments since TCJA did not change the tax rates governing dividends and capital gains on equity.

2.3.3. Effective Tax Rates for Robust Tests

The above estimates used for our main tests, can be subject to error due to the variations that occur in estimates of tax rates. These estimates can weight tax provisions differently. For example, suppose we assign significant weight to the tax provision where PTs can receive a 0.20 reduction in taxes paid until at least 2024. Whereas this deduction helps smaller PTs who qualify, the bulk of taxes are paid by larger PTs who earn too much to qualify. Thus, the impact of this deduction on the effective TE may be small. Regardless, if such a provision is an important factor, then our estimate of TE for PTs is too high. In addition, PTs can buy shares in publicly traded companies or achieve capital gains on assets. If so, they pay taxes on qualified dividends and capital gains at the typical maximum TE of 0.2. Besides the above arguments for a lower effective tax rate for PTs, Hull and Price (2015) cite studies suggesting lower effective tax rates for both PTs and CCs. In light of the above factoids, we tested a set of lower effective tax rates on business income for PTs and CCs. Below we describe these effective tax rates.

To overcome potential inflation of TE, we performed robust tests where we seek a levered TE that is about 0.04 below that of our main PT tests. Similarly, we sought a levered TC that, on average, is about 0.04 below our main CC tests. To achieve the PT goal, we set the unlevered TE so it is 0.05 below that of our main PT tests. This serves to yield effective TE values for PTs near 0.26 and 0.24 for our respectively pre-TCJA and TCJA tests and thus 0.04 below the corresponding values of 0.30 and 0.28 for our main PT tests. Just like TE, disagreements can also be found for TC, as it also can vary from year to year with values often lower than what we use in our main tests. In response, our robust tests, that use a lower TE for PTs, also utilized a lower TC for CCs. While we lowered unlevered TE by the same amount (namely, 0.05) for both pre-TCJA and TCJA tests for PTs, such is not the case for CCs where the TCJA fall for TC is much greater than found for TE. Thus, we found it more appropriate to lower the unlevered TC for pre-TCJA tests by 0.07 and the unlevered TC for TCJA tests by only 0.03. The average of these values of 0.07 and 0.03 is 0.05. This average is like the PT tests where the unlevered TE is set 0.05 below for all of our main tests. Setting the unlevered TC (as just described) yields effective levered TC values at ODV that are 0.23 and 0.15 for respective pre-TCJA and TCJA tests. These levered TC values are about 0.06 and 0.02 below those for respective pre-TCJA and TCJA tests with an average of 0.04.

Besides robust tests that use lower effective tax rates, we performed robust tests that use spreads for 2017 and 2018. For these tests, we used the same tax rates described in Section 2.3.2 that are utilized for our main tests. Since these tests generate more results, for brevity’s sake, these results are only reported when relevant, especially if they produce differences from our main tests. The results for our lower effective tax rate tests are briefly summarized in Section 6.2.

3. Methodology

After discussing major capital structure models, this section identifies and describes the model best suited to represent the methodology that generates this study’s outputs for the three categories of debt choice, valuation, and leverage gain. Besides the methodology described in this section, we also use two procedures when illustrating the nongrowth and growth applications of the CSM in the next section. The first procedure matches costs of borrowings to debt choices (Section 4.1) and shows how key inputs for the CSM are obtained. The second procedure determines how we identify optimal outputs (Section 4.2) for nongrowth and growth tests.

3.1. Capital Structure Models

Trade-off capital structure models (Baxter 1967; Kraus and Litzenberger 1973; DeAngelo and Masulis 1980; Berk et al. 2010) argue that an interior ODV exists. Baxter was one of the first researchers to provide the major trade-off argument. At that time, the trade-off argument stated that, as leverage increases, negative effects from financial distress costs will eventually outweigh the positive effects from the debt tax shield. Since this formulation by Baxter, the trade-off argument has been modified to incorporate other leverage related effects such as those posited by agency theory (Jensen and Meckling 1976; Jensen 1986). While the mainline trade-off models focus on CCs, the Capital Structure Model (CSM) provides a trade-off framework that covers both CCs (Hull 2018) and PTs (Hull 2019).

Since Baxter (1967), the main innovation in capital structure models is arguably that given by developers of agency models. Agency models fall under the umbrella of trade-off models as agency theory offers a structure that leads to an ODV with or without taxes. Jensen and Meckling (1976) demonstrate how an ODV can result simply from principal-agent valuation effects. Subsequent agency theory researchers (Gay and Nam 1998; D’Melloa and Miranda 2010) describe two principal-agent problems, underinvesting and overinvesting, that are related to financing of projects where projects serve to advance the wealth of either debt ownership or equity ownership at the expense of the other ownership. Besides the conflicts between equity and debt owners, agency models address valuation effects when debt enters the capital structure. For example, consider an all-equity firm with an excess of cash flows that leads to managerial waste. Jensen (1986) argues that such an enterprise can add value by issuing debt because interest obligations serve to discipline the spending of managers so that fewer cash flows will be spent on suboptimal and wasteful undertakings. Additionally, agency models cover the conflicts between principle-agents in the form of owners-managers. These conflicts are prevalent in large companies as embodied by CCs where owners and managers often have interests that are not aligned. For small enterprises, as characterized by PTs, owners and managers are often the same person, thereby mitigating owners-managers conflicts.

Like agency models, pecking order models of financing (Donaldson 1961; Myers 1977; Myers and Majluf 1984) do not depend solely on taxes. For pecking order proponents, the top two preferences in financing are internal equity followed by debt. External equity is the last resort with a major reason being the large asymmetric information costs reflected in the negative signaling that accompanies new equity issues. The pecking order preferences in financing is consistent with forty years of historical data given by Damodaran (2014) where internal equity ranges from 58 percent to 83 percent of the total financing, debt ranges from 13 percent to 28 percent, and external equity ranges from 2 percent to 17 percent. While pecking order models are not considered within the umbrella of trade-off models, there is nothing inherent in these models to unequivocally rule out the possibility of an optimal mix of equity and debt.

Pecking order models do not address the high costs experienced by businesses when using internal equity in the form of retained earnings (RE). In contrast, the CSM addresses the cost of RE by arguing that RE can only be used after business taxes are paid on it. As alluded to earlier, business taxes are the personal taxes paid on taxable income for PTs and the corporate taxes paid on taxable income (EBT) for CCs. The CSM points out that RE is not only taxed before it can be used for growth but the subsequent cash flow that RE creates is further taxed at the same business level. This is like a double taxation if we contrast it with new (external) equity and debt issues that are not taxed before usage. However, new issues do create flotation costs, which are typically small compared to the costs of business level taxes on RE. If used for growth, then subsequent cash flows from the new issues will be taxed at the business level (like RE) but this is the only association it has with being taxed.

3.2. Identifying an Adequate Capital Structure Model

Researchers (Leland 1998; Graham and Harvey 2001; Graham and Leary 2011) suggest capital structure theory is imprecise, offers vague direction, and accounts for only part of the known behavior regarding debt choices. As noted by Hull (2019), the heart of this indictment suggests that searching for an adequate capital structure model presents difficulties. In our quest to identify an adequate model, we focus our search on a perpetuity model that computes outputs for the three categories debt choice, valuation, and leverage gain when an unlevered firm chooses among finite debt choices. We hold that knowing these outputs are necessary if managers are to make fully informed corporate governance decisions.

A starting point for our quest to find an adequate capital structure model is the perpetuity capital structure model of Modigliani and Miller (1963). The MM model offers a corporate tax-based equation for computing a company’s gain to leverage (GL). This model focuses on the corporate tax shield when debt is issued to retire unlevered equity. The MM model claims the gain to leverage (GL) is the corporate tax rate (TC) time debt (D). Thus, this model is aimed at CCs. While this model allows for a perpetuity debt tax shield of TC(D), its GL equation ignores financial distress costs such as captured by increasing costs of borrowing as more and more debt is issued. To illustrate, GL is firm value (VL) minus unlevered firm value (VU) and this definition for GL includes variables that have both the unlevered cost of equity and levered cost of equity, which are not found in the MM equation of GL = TC(D). The MM equation for CCs also says nothing about growth, implies that a company can issue unrestricted amounts of debt, and ignores personal taxes paid on distributions.

Extensions of MM include a role for personal taxes in capital structure modeling such as Miller (1977). The Miller model is GL = (1 − α)D where α captures the effects of personal and corporate taxes. However, like MM, the Miller model ignores financial distress effects, does not contain the costs of unlevered and levered equity, focuses on CCs, and can imply that a firm issues unlimited amounts of debt. In regard to the latter, the relation of α < 1 (which is the likely scenario for most ownership forms with reasonable leverage ratios) leads to the MM conclusion that firms attempt to issue unlimited amounts of debt. If α = 0, then GL = 0. If α > 1, then GL < 0. All of these outcomes for GL indicate that issuing debt does not produce an interior ODV. As such the Miller model does not reflect either conventional beliefs or observed managerial behavior such as managers targeting credit ratings (Kisgen 2009) to attain an interior ODV.

In contrast to the MM-Miller models, agency and pecking order models provide less direction on how to compute exact GL values as these models are not known for compact GL equations with measurable inputs. For example, how does one quantify all of the agency costs and benefits given by the agency theory literature? While a pecking order model is straightforward in terms of the order of financing preferences, it lacks comprehensive directives on how to measure the costs involved in the preferences for financing. For example, how do we accurately measure asymmetric information costs (which is a pecking order reason for not issuing external equity)? The pecking order model also does not address the cost of using internal equity (or retained earnings) for growth when compared to external equity where internal equity can only be used after it has been taxed. Whereas external equity is spared the potentially large costs associated with a maximum statutory business tax rate, it does experience equity issuance costs when issued for any purpose including growth. However, issuance costs represent a much smaller percentage of the proceeds from the issue compared to the tax rate paid by a typical business on retained earnings (RE) before it can be used for growth. In conclusion, agency and pecking order models do not offer formulations where all of its inputs are measurable inputs. It follows that these models are hard pressed to pinpoint preciseness in outputs for the three categories of debt choice, valuation and leverage gain where such preciseness is needed for correct capital structure decision-making.

As shown in the computations in the appendices, the CSM offers multi-component GL equations that are consistent with trade-off arguments. Of practical importance, the CSM’s components use measurable variables, as we illustrate in our appendices. Of further significance, the CSM’s components are equipped to handle positive and negative effects. This is because these components contain not only positive agency-tax effects but also negative agency-financial distress effects. At some point, as the debt level becomes too high, an overall net negative effect occurs so that the CSM equations generate concave relations between firm value and leverage. These concave relations, that are needed to create an interior ODV, are graphically shown in Section 5.

Of utmost importance, the CSM is unique in its capacity to tie together growth and leverage through its innovative development of unlevered and levered equity growth rates (gU and gL). The gU and gL equations for PTs with corresponding nongrowth and growth constraints was developed by Hull (2019), who also overviews the corresponding gU and gL equations for CCs. The gU and gL equations for CCs were first given by Hull (2010) with gL updated by Hull (2018) who added nongrowth and growth constraints for CCs. These constraints are violated when debt become too large. For example, with the plowback ratio (PBR) set (which implies the payout ratio with equity distributions is also set), it becomes more difficult for finite cash flows to cover interest payment as debt increases. With too much debt, this produces a situation where a firm is short of cash flows. Since debt owners have first claims, the firm does not have enough cash flows to meet its plowback and payout goals. As can be gleamed from comparing the nongrowth and growth outputs in later appendices, the growth constraint is violated at lower leverage ratios compared to the nongrowth constraint. This occurs because RE is zero with nongrowth and so more debt can be issued. Consequently, the growth constraint is also referred to as the retained earnings (RE) constraint as the CSM focuses on RE as the source of growth.

Given the above discussion, this study used the CSM to produce outputs for the three categories of debt choice, valuation, and leverage gain. As illustrated in this paper’s figures and appendices, the CSM is a trade-off model that includes costs of borrowing, allows for measurable inputs, and produces outputs that identify an interior ODV. In addition, the CSM can be applied to both PTs and CCs as shown in Section 6.

4. Pass-Through Variables, Procedures, Computations, and Applications

This section provides the procedure to get credit spreads, ratings, and costs of borrowing tied to debt choices; determines the optimal credit rating (OCR); introduces variables, procedures, and computations to get values for outputs; and, offers applications showcasing outputs at ODV.

4.1. Procedure to Match Credit Spreads, Ratings, and Costs of Borrowing to Debt-to-Firm Value Ratios

Table 1 contains the procedure used to get increasing costs of borrowing matched to the fifteen increasing P choices where a P choice refers to the proportion of unlevered firm value (EU) retired with debt (D). The increase in borrowing costs as leverage increases is a key to discovering the maximum firm value that identifies ODV. In this table, we follow the procedure given by Hull (2020) for his nongrowth and growth CC tests when using interest coverage ratios (ICRs), credit spreads, and Moody’s ratings as supplied by Damodaran (2019) for 2018. Table 1 provides value when using Hull’s procedure for a nongrowth pass-through (PT) test under TCJA using ICRs, spreads, and ratings supplied by Damodaran (2020) for 2019. The ICRs and credit ratings given by Damodaran do not change from 2018 to 2019 but the credit spreads (that are matched to the ICRs and ratings) do change. The same procedure described in Table 1 for a nongrowth PT test under TCJA is used to get costs of borrowing matched to P choices for all of this paper’s other tests (that include CC, growth, and pre-TCJA tests). The values presented and derived in Table 1 are needed when applying the CSM equations, as illustrated in the three appendices.

Table 1.

Costs of Borrowing.

As described in Table 1, ICRs are determinants of P choices and debt-to-firm value ratios (DVs) that are all matched to costs of borrowing. Because we used the same ICR values given by Damodaran (2020) for all PT tests (which are the small firm classification as described in Table 1), the interest payment (I) is identical for each P choice for all nongrowth and growth tests. As seen in the computation for I in Table 1, this is because tax rates and cash flows before taxes (CFBT) are the same for each P choice. Similarly (and as can be seen in Table 1), because costs of borrowing (like tax rates) are identical for each P choice, debt (D) is also same for each P choice for all PT nongrowth and growth tests. While I and D are identical for each P choice for PT growth and nongrowth tests, values for P choices and DVs are different for nongrowth and growth tests because they are a function of equity value and the growth equity value is different from the nongrowth equity value for each test. The latter difference is detailed in Appendix A, while illustrative computations for P choices and DVs (along with other variables) are detailed in Appendix B and Appendix C.

As noted in Table 1, we have a key assumption that involve PTs being identified with ICRs for a small firm classification and CCs being identified with a large firm classification. However, the data used by Damodaran (2020) for ICRs would not have firm values as small as sole proprietorships, except for rare cases that can occur for a sole proprietor that is unusually large in firm value. Thus, this study’s PT findings might be better visualized as consisting of larger PTs, as this would be more likely to be found in partnerships (general or limited), limited liability companies, and S corps. Additionally, it should be pointed out that both PTs and CCs consist mostly of small firms. However, most large firms are CCs and the larger CCs would dominate smaller CCs in terms of employees and revenues.

Finally, we should emphasize, as illustrated in Table 1, that costs of borrowing are based on credit spreads and so are matched to credit ratings. This is important because using spreads associated with ratings and ICRs to determine DVs is consistent with the research (Graham and Harvey 2001; Kisgen 2006) that suggests ratings rank higher than other factors in determining capital structure decision-making.

4.2. Procedures to Determine Optimal Outputs

This section describes our procedures to determine optimal outputs. These procedures include those for nongrowth, unrestricted growth, and restricted growth.

4.2.1. Procedure with No Growth

Determining ODV and the optimal credit rating (OCR) using the CSM’s nongrowth GL equation is an easy task as one and only one maximum firm value (max VL) was achieved, as illustrated later in Section 5. For nongrowth tests, the simple procedure involves examining all feasible VL outputs generated by the nongrowth GL equation and choosing the largest VL where VL = GL + unlevered firm value (EU). The largest value VL is referred to as the maximum VL (max VL) where max VL = max GL + EU. Thus, either max VL or max GL can identify all other optimal nongrowth outputs, including ODV and OCR where the nongrowth OCR for PTs is Moody’s A3 (for CCs, the nongrowth OCR is Moody’s Baa2). Optimal outputs for a nongrowth PT are computed in Appendix B where we can see in that the largest VL occurs at A3.

4.2.2. Procedure with Unrestricted Growth

Determining optimal outputs such as ODV and OCR using the CSM’s growth GL equation is not simple especially if we have many possible growth rates to test where each growth rate is represented in the CSM by the levered equity growth rates (gL). If we do not restrict gL, then we can find (through trial and error) the plowback ratio (PBR) that yields the largest VL. However, this procedure leads to extremely high gL values as VL increases and these gL values are unsustainable for long periods based on historical growth in US GDP. Thus, we cannot claim that the largest VL is max VL. Regardless, this unrestricted growth procedure is informative because as we initially began to increase the PBR and achieve high (but still sustainable) gL values, we found the largest VL consistently occurs at the same nongrowth OCR. As PBR and gL continue to increase, the largest VL will occur at a lower quality rating that is often just a notch below in quality from the nongrowth OCR. However, this lower quality rating can only be achieved with growth rates that are historically very difficult to sustain for long-run time frames. Thus, at least for this paper’s tests, we concluded that max VL for growth occurs at the same OCR, as found with our nongrowth test.

It should be noted that if we continue to increase PBR thereby achieving gL values that are even more unsustainable, we find that the growth constraint begins to set in at lower P choices or, equivalently, set in at higher quality ratings. Eventually, this limits the feasible P choices so that only high quality credit ratings become feasible and VL can fall with high ratings but for some tests can increase and even occur with growth rates that are not much greater than the long-run historical growth rate. This is because gL is a levered rate that increases with greater debt choices. This means that gL can fall as greater debt choices becomes unfeasible because of violation of the growth constraint. Thus, it becomes possible to find a larger VL at a higher quality rating with a gL that is historically sustainable. However, we know an average firm cannot attain higher quality ratings and so we have to question these outcomes, at least for a typical firm. It is during these tests with increasing growth (accompanied by violations of the CSM’s growth constraints) that computations become unstable for any credit rating that is accompanied by high levels of debt where the growth constraint can be violated. This instability also reflects the reality, as first noted by Hull (2010), that the GL equation requires an iterative procedure because gL and GL are interdependent.

If we continue to increase PBR, at some point only an unlevered firm value (EU) becomes feasible because the growth constraint is violated for every credit rating. When a levered firm becomes unlevered, then VL turns into EU and gL becomes an unlevered growth rate (gU) where interest (I) can no longer compete with RE for use of the operational cash flows. At this point, it is possible for EU to compete with the highest VL and do so while maintaining a growth rate that is not abnormally high. However, as PBR continues to increase for this unlevered situation, gU will increase along with a rising EU. Like the larger VL values with credit ratings of higher quality than the nongrowth OCR, the larger EU values can only be reached with a historically unsustainable growth rate that is unrealistically high, especially for a perpetuity model like the CSM.

4.2.3. Procedure with Restricted Growth

As just seen, there are complications that need to be overcome when using the growth CSM if growth is unrestricted. It is also impractical to perform a countless number of tests using a large number of different growth rates at varying DVs to determine max VL. We circumvented such complications and impracticalities by conducting tests where we restrict growth rates to a finite number of reasonable rates. For our first restricted growth test, we used the long-run sustainable growth rate of 3.12%, which was first described in Section 4.1. For this rate for both pre-TCJA and TCJA tests, we examined all feasible credit rating with gL = 3.12% to see which rating generates the greatest firm value. We can stop here for pre-TCJA tests but not for TCJA tests because a higher growth rate is projected under TCJA. For reasons given in Section 4.1, we used gL = 3.90% and gL = 4.50% for two additional growth tests under TCJA. As before, we then proceeded to test all feasible credit ratings in conjunction with these two growth rate before making a decision on max VL that identifies the growth OCR. We now describe the outcomes for the above tests.

Given the above, we proceeded to test gL = 3.12% for our first growth PT test under both pre-TCJA and TCJA. To get gL = 3.12% for each credit rating being tested, we set PBR through trial and error until gL = 3.12% occurs for a P choice that corresponds to the rating being tested. For both pre-TCJA and TCJA tests for PTs, we found that the nongrowth OCR of A3 is also the growth OCR. The optimal outputs for the 3.12% growth PT test under TCJA are computed in Appendix C. From this appendix, we can see that the largest VL occurs at A3. Thus, this largest VL is max VL and it identifies optimal outputs including A3 as the OCR.

For CCs, the nongrowth test and the growth test when gL = 3.12% (for both pre-TCJA and TCJA tests) produce two differences from PTs. First, the nongrowth tests for CCs under pre-TCJA and TCJA yield a lower medium grade rating of Moody’s Baa2 as the nongrowth OCR. Second, we can find higher VL values for ratings of higher quality than Baa2 when gL = 3.12% is tested. Thus, unlike PTs, we cannot confirm for CCs that the same OCR occurs for both nongrowth and growth of 3.12% for pre-TCJA and TCJA tests. However, evidence indicates we should be hesitant in claiming a typical CC can attain a rating greater than Baa2 while achieving gL = 3.12%. For example, as indicated by Morningstar (2019), high quality ratings are becoming rarer. Thus, when using a growth rate of 3.12%, we concluded that both a nongrowth and growth CC will typically achieve its OCR at a rating of Baa2. Even though we concluded that a typical growth CC will achieve its max VL at Baa2, we would also advocate that an above average CCs can attain higher quality ratings at gL = 3.12% and therefore have higher max VL values. Regardless, the increase in max VL is small even if we claim the higher max VL is achievable for some CCs. For example, for the TCJA test, we found only a 2.66% increase in max VL if a CC can attain an OCR of A3 with gL = 3.12% instead of an OCR of Baa2 with gL = 3.12%. While max VL only increases by 2.66% for this CC test, its ODV would falls by 19.22%. This indicates that our computations for ODVs can be sensitive to the OCR that is achieved.

We next tested gL = 3.90% and gL = 4.50% under a TCJA tax environment. As described previously, these two annual growth rates under TCJA are consistent with the sources cited by the Tax Policy Center (2018). An annual growth rate of 3.90% is also consistent with periods of 20 to 25 years that occur within the past 70 years. To find an average annual growth of 4.50% for a period longer than 10 years, we would have to go back 85 years and include years of extreme growth associated with the 10-year period from 1934 through 1943 where the average annual growth in GDP was 10.49%.

For our gL = 3.90% and gL = 4.50% tests, CC and PT results are like those just outlined for gL = 3.12% tests except for the PT test for gL = 4.50%. For this latter PT test, the nongrowth OCR of A3 is not attainable due to violation of the growth constraint at A3. To achieve gL = 4.50% for PTs, we had to drop the nongrowth OCR a notch from A3 to Baa2. For higher growth rate tests for both PTs and CCs, we can occasionally find greater VL values for credit ratings of higher quality than the nongrowth OCR. This is especially true for the gL = 3.90% test. For these situations (where greater VL values occur for credit ratings of higher quality), we once again concluded that the strongest firms can attain the same high growth with ratings of higher quality than the quality of the nongrowth OCR. For example, if a PT can achieve a higher quality rating of A2 with a growth rate of 3.90%, max VL can increase but by only 2.62%. However, we maintain that an average firm (which is what this study focuses on) is not likely to achieve an OCR of greater quality than the nongrowth OCR. To maintain the same high growth rate of 3.90% or 4.50% at a higher credit rating, PBR must increase more and more as the credit rating increases in quality and so more internal equity funds would be needed to maintain the same rate of growth. This could prove very difficult even in the short-run without the infusion of cash from a new external security issue that supplies funds for growth.

As a whole, we interpreted all of our tests as indicating a typical PT achieves a Moody’s A3 credit rating at ODV (with the exception of Baa2 for the gL = 4.50% tests) and a typical CC consistently attains a Moody’s credit rating of Baa2 at ODV. The lower credit rating for a CC, compared to a PT, is congruent with the notion that larger firms are less risky and investors would be willing to buy more debt even when lower quality ratings occur. As shown later in Section 6, we find this notion to be valid as the average ODV is 0.2377 for PT tests compared to 0.4132 for CC tests. As also shown later, some of our findings are subject to change when we tested spreads for 2017 and 2018 but not so much when we tested lower effective business tax rates for PTs and CCs.

4.3. Introductory Variables and Computations Used by Capital Structure Model (CSM)

Appendix A presents introductory CSM variables and their computations when a PT manager achieves a credit rating of Moody’s A3, which is the unambiguous OCR for nongrowth and growth tests when gL is 3.12%. The computations use the Capital Structure Model (CSM) of Hull (2019) for PTs with tax rates under TCJA. The computations featured in Appendix A are as follows.

First, Appendix A provides computations for two coefficients first derived by Hull (2014) for CCs to capture the effects of tax rates. Hull (2019) updates these coefficients so they apply to PTs. The first coefficient (α1) is the Miller (1977) alpha that was first derived by Farrar and Selwyn (1967) and updated by Hull to account for changes in tax rates as leverage changes. The second coefficient (α2) is the Hull alpha. Because the same tax rates occur with each P choice for all PT tests, values for α1 and α2 are the same for all PT tests and are respectively found in the 1st and 2nd components of the GL equations for PTs. The latter also holds for CC tests, albeit alpha values for CCs are different because they have slightly different formulas due to the extra layer of corporate taxes. Regardless, α1 and α2 values increase with leverage for both PT and CC tests. Appendix A computes α1 and α2 when the PT achieves its OCR at Moody’s A3 under TCJA. As seen in this appendix, these alpha values are α1 = 0.905586 and α2 = 1.069579. For a nongrowth GL equation, an increasing α1 makes the 1st component more positive while an increasing α2 makes the 2nd component more negative. For a growth GL equation, an increasing α1 makes the 1st component more positive but then reverses its effect, while an increasing α2 lessens its negative effect on the 2nd component and then makes this 2nd component more positive until the growth constraint is violated.

Second, when computing unlevered firm value (EU) under TCJA, Appendix A offers a PT nongrowth example and a PT growth example for gL = 3.12%. The starting point to compute EU is $1,000,000 in before-tax cash flow1. For the nongrowth example where PBR = 0 and the unlevered personal equity tax rate (TE1) = 0.33, the nongrowth EU was computed as $9,922,251. For the growth example where the optimal PBR is 0.3435 at ODV, the growth EU was shown to be $10,030,170 and thus growth adds $107,919. While our pre-TCJA test where TE1 = 0.35 is not shown in Appendix A, we obtained a nongrowth EU of $9,626,064 and a growth EU of $9,638,148 with a PBR of 0.3515 and so only $12,084 was now added from growth. Thus, an increase of TE1 from 0.33 to 0.35 made the difference in nongrowth EU and growth EU fall from $107,919 to $12,084. If we continued to increase TE1, then the nongrowth EU would become greater than a growth EU and value would be subtracted instead of added with growth. This reflects the fact that RE used for growth becomes more expensive as it is taxed at higher tax rates.

Is there a way of knowing when the nongrowth EU will be greater than the growth EU? The answer lies in the discussion by Hull (2010, 2018) of the relation between taxes on retained earnings (RE) and PBR. Hull proves the nongrowth EU is greater than the growth EU when the cost of internal equity financing is greater than PBR. For Hull, the cost of using internal equity financing involves the business taxes paid on RE before it can be used to finance growth. As illustrated in the prior paragraph for the TCJA test, when the cost of unlevered TE1 is 0.33 and thus lower than PBR of 0.3435, an unlevered firm added $107,919 in value through growth. However, the nongrowth EU and growth EU were similar for a pre-TCJA environment with only $12,084 in value added when the cost of unlevered TE1 increases from 0.33 to 0.35 (with the PBR increasing from 0.3435 to 0.3515, which is about 3/8 as much of an increase compared to TE1). As will be seen later in Section 6 for the pre-TCJA tests for CCs, the nongrowth max VL of $10.032 M is greater than the growth max VL of $9.476 M when gL = 3.12%. This reflects the fact that the unlevered nongrowth EU is greater than the unlevered growth EU where RE is taxed at the pre-TCJA unlevered corporate tax rate (TE2) of 0.35, which is greater than the PBR of 0.3366. In conclusion, PBR must be greater than the business level tax rate on RE if growth to enhance nongrowth EU. If it cannot, then the nongrowth max VL is more likely to be greater than the growth max VL. This is why TCJA is important as expectations are that growth will increase beyond 3.12%, causing PBR to increase so that it will be greater than the unlevered tax rate (TE1 for PTs and TE2 for CCs) and make growth more affordable for firms.

4.4. Pass-Through Applications: Nongrowth and Growth under TCJA

We now provide nongrowth and growth applications for pass-throughs (PTs). These two applications serve as respective examples of this study’s four nongrowth and eight growth tests. Like Appendix A, these applications use tax rates for TCJA tests as covered in Section 2.3.

Appendix B reports a nongrowth pass-through (PT) application under TCJA using the PT nongrowth GL equation of Hull (2019). This appendix includes a table that reports values for variables for eleven of the sixteen P choices where the sixteen P choices consist of an unlevered P choice of zero and fifteen interior P choices corresponding to the fifteen interest coverage ratios (ICRs) with matching ratings and spreads supplied by Damodaran (2020) for the year 2019. The bold print column in the table in Appendix B with the OCR of A3 provides optimal values ranging from P = 0.2582 in the top row to ODV = 0.2409 in the bottom row.

As seen in the table accompanying Appendix B, negative GL values first occur when the nongrowth PT goes from a non-investment grade credit rating (Moody’s Ba1) to a lower quality non-investment rating (Moody’s Ba2). The next lower quality rating (Moody’s B1) is a highly speculative credit rating. An even lower quality rating of B2 is in the last column. While not shown in Appendix B, if we were to issue enough debt to achieve a Moody’s Caa rating (which is a rating that indicates extreme speculation bordering on default), the PT nongrowth constraint would be violated. This constraint is breeched at high debt levels when the firm no longer has the cash flows to cover interest (I) with part of the reason being lower (or even negative) GL values. Whereas positive GL values can provide funds to pay I, negative GL values lower funds that could otherwise be used to pay I.

In the bottom half of Appendix B, we show computations for optimal values for variables in the bold print column of the accompanying table where the PT attains a max VL of $10.633M (M = million) at its ODV of 0.2409. For example, the max %∆EU was computed as 7.16% at this ODV. This percentage of 7.16% indicates leverage adds, on average, 7.16 cents to unlevered firm value (EU) for every dollar of debt issued to retire EU when a nongrowth PT is at this ODV. The net benefit from leverage (NB) was computed as 27.74%, indicating that each dollar of debt, on average, adds 27.74 cents to GL when the PT is at its ODV. A greater value for NB indicates greater efficiency per dollar of debt issued.

Appendix C is like Appendix B but replaces a nongrowth PT with a growth PT using an annual growth rate of 3.12% under TCJA. As noted earlier, this rate was captured in the CSM by using a levered equity growth rate (gL) of 3.12%. This appendix uses the PT growth GL equation of Hull (2019). The growth OCR (achieved with a PBR of 0.3435), like the nongrowth OCR seen in Appendix B, has a Moody’s upper medium rating of A3. The bold print column of the table that accompanies Appendix C provides optimal values ranging from P = 0.2554 in the top row to ODV = 0.2381 in the bottom row. The last two columns are in gray-shade to signify that their values are unfeasible, as the growth constraint is violated once we achieve a Moody’s credit rating of B1, which is a highly speculative rating.

In the bottom half of Appendix C, we compute the optimal values found in the bold print column of the table that accompanies this appendix. To illustrate, the max %∆EU was computed as 7.25%, indicating the unlevered firm value increases by 7.25% when the optimal amount of debt is issued. This is a bit above the 7.16% achieved for the nongrowth situation. While we can note other differences in nongrowth versus growth values when comparing the accompanying tables in Appendix B and Appendix C, these differences are also small. For example, we found slightly larger values with growth for the outputs of max GL, max VL, and NB when compared to nongrowth values. The value for ODV of 0.2381 with growth was slightly lower than the ODV of 0.2409 for nongrowth. This slightly lower ODV is explained by the greater equity value for growth as the fifteen debt values are the same for either a nongrowth test or a growth test. They are the same because debt values are derived from interest coverage ratios (ICRs) and the same ICR values are used for all PT tests (as described in Section 4.1). Finally, while a growth rate of 3.12% does not produce noteworthy differences with nongrowth outputs, Section 6 will show that this is not the case for higher growth rates of 3.90% and 4.50%.

5. Pass-Through Results in Graphical Form

This section provides three PT figures. Somewhat similar figures for CCs can be found in Hull (2020). Figure 1 plots the gain to leverage (GL) and its two components against debt-to-firm value ratios (DVs) under TCJA when there is nongrowth. Figure 2 repeats Figure 1 but replaces the nongrowth values with growth values using the historical growth rate of 3.12%. Figure 3 plots firm value (VL) against credit ratings for the TCJA nongrowth test and the three TCJA growth tests. As first described in Section 1, these three growth tests involve growth rates of 3.12%, 3.90%, and 4.50%. Figure 3 only considers the feasible P choices for growth tests causing the three growth trajectories to have different plot points. Unfeasible choices are not possible due to violation of the growth constraint. Whereas growth trajectories only consider feasible points, the nongrowth trajectory is truncated in that all of its feasible points are not shown.

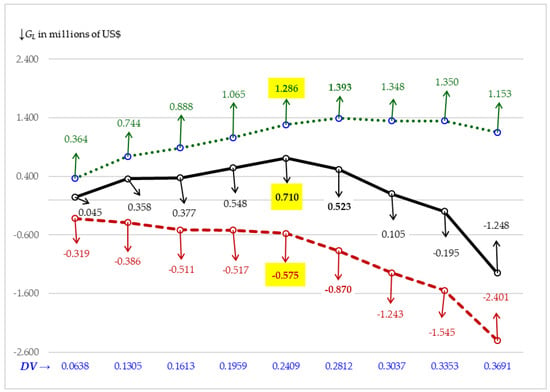

Figure 1.

Nongrowth Pass-Through Gain to Leverage (GL) Versus debt-to-firm value ratios (DVs) under Tax Cuts and Job Acts (TCJA) with gL of 0% and optimal credit rating (OCR) of A3. Gain to Leverage (GL), solid line; 1st Component, dotted line, and 2nd Component, dashed line.

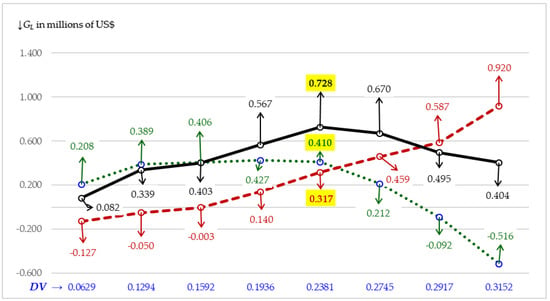

Figure 2.

Growth Pass-Through GL Versus DV under TCJA with gL of 3.12% and OCR of A3. Gain to Leverage (GL), solid line; 1st Component, dotted line, and 2nd Component, dashed line.

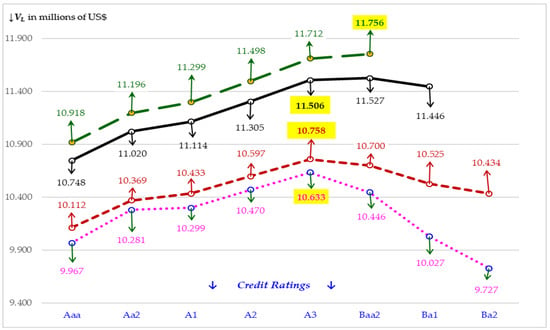

Figure 3.

Nongrowth firm value (VL) (dotted line), 3.12% Growth VL (smaller dashed line), 3.90% Growth VL (solid line), and 4.50% Growth VL (larger dashed line) Versus Moody’s Credit Ratings for Pass-Throughs under TCJA with OCR of A3 target except for top trajectory where OCR is Baa2.

5.1. Gain to Leverage versus Debt-to-Firm Value Ratio

The trajectory in Figure 1 uses the PT nongrowth GL equation of Hull (2019) that is illustrated in Appendix B. This trajectory ends with DV = 0.3691, which corresponds to a Moody’s credit rating of B1. While not shown, the last feasible DV of 0.5201 corresponds to a rating of B3. As was seen in Section 4, the next rating below B3 in quality is Caa and this latter rating is where the nongrowth constraint is violated. The 1st component given by the top trajectory (dotted line) has an upward trend until the first downward bump occurs at DV = 0.3037. The bottom trajectory (dashed line), representing the 2nd component, is decreasing with the drop-off becoming steeper as more debt is issued. These trajectories are consistent with the notion that the 1st component captures the positive leverage effects from tax and agency benefits related to debt while the 2nd component capture the negative leverage effects from financial distress and agency costs.

The GL nongrowth trajectory (given by the solid line) of Figure 1 is concave in shape and peaks at the ODV of 0.2409 where the OCR is Moody’s A3 rating. There is asymmetry in the GL nongrowth trajectory where the fall off is greater after the maximum GL (max GL) of $0.710M (M = millions) is reached where $0.710M is per $1,000,000 in before-tax cash flows. GL first becomes negative for a rating of Ba2 with a DV of 0.3353, which is before it enters the highly speculative rating of B1 where DV = 0.3691. From here the negativity in GL continues as debt choices rise until the nongrowth constraint is violated, at which point all outputs are unattainable. As noted above, the last feasible DV (before the constraint violation occurs) is 0.5201, which corresponds to a Moody’s rating of B3. All ratings of lower quality than B3 are unfeasible and cannot support the debt choice associated with such a low quality rating.

Figure 2 repeats Figure 1 but replaces nongrowth with growth using the PT growth GL equation of Hull (2019). Results for this equation are illustrated in Appendix C. Figure 2 contains only feasible plot points because values after DV = 0.3152 are unattainable as the growth constraint is violated. A DV of 0.3152 corresponds to a Moody’s rating of Ba2, which is the second non-investment or speculative rating given by Damodaran (2020). The 1st component in Figure 2 has a trajectory (dotted line) that is concave in shape like the 1st component in Figure 1 except it has a greater drop-off after its peak is reached at DV = 0.1936. The 2nd component in Figure 2 has an upward trajectory (dashed line) that is concave upward but does not exhibit full concavity. This trajectory contrasts with the downward trajectory of the 2nd component in Figure 1. Regardless, this trajectory’s first three plot points are negative and its later positive plot points are offset by negative plot points in the trajectory for the 1st component.

Despite differences in the trajectories of the 2nd components in Figure 1 and Figure 2, the GL growth trajectory (solid line) in Figure 2 is concave in shape like the GL nongrowth trajectory in Figure 1. The GL growth trajectory peaks at the ODV of 0.2381 where max GL = $0.728 M. While not shown, similar trajectories for GL and its two components occur if we increased the annual growth rate to gL = 3.90% or gL = 4.50%. However, as will be seen in Figure 3, full concavity becomes more difficult to achieve as the growth rate continues to increase.

In summary form, Figure 2 is different from Figure 1 in four ways. First, a growth trajectory in Figure 2 stops at a lower DV compared to a nongrowth trajectory in Figure 1. This is because the growth constraint in Figure 2 sets in after DV reaches 0.3152 while the nongrowth constraint in Figure 1 occurs at a much higher DV. Although not shown in Figure 2, the violation occurs at DV = 0.6168 (as can be seen in Section 4). Second, the growth trajectory for the 1st component (dotted line) has an interior maximum at the DV of 0.1936 before the ODV of 0.2381 is reached. This differs from the nongrowth trajectory for the 1st component that is still rising at its ODV. Third, the growth trajectory for the 2nd component (dashed line) trends upward, while the nongrowth trajectory for the 2nd component trends downward. Fourth, a close comparison of Figure 1 and Figure 2 reveals that nongrowth GL values were similar to growth GL values until we reached the optimal P choices, at which point growth GL values became greater and continued to increase relative to nongrowth values until the growth constraint was violated.

5.2. Pass-Through Firm Value versus Credit Ratings

Figure 3 plots firm value (VL) versus credit ratings for the nongrowth PT tests under TCJA and three growth PT tests under TCJA. This figure differs from the prior two figures by replacing GL with VL along the vertical axis and DV with Moody credit ratings, as used by Damodaran (2020), along the horizontal axis. For Figure 3, we only include credit ratings up to Ba2. As seen in this figure, the two trajectories for the two greatest growth rates (3.90% and 4.15%) cannot reach this rating of Ba2, as the growth constraint is violated at quality ratings greater than Ba2. For the nongrowth PT trajectory (dotted line at bottom), violation of the nongrowth constraint occurs at the extremely speculative rating of Caa, which is well below Ba2 in quality as was shown in Section 4. For the growth trajectory (small dashed line) when gL = 3.12%, violation of the growth constraint first occurs with a rating of B1, which is a rating just below Ba2 in quality. For the growth trajectory (solid line) when gL = 3.90%, violation of the growth constraint occurs at a rating of Ba2 and so this trajectory ends at a rating of Ba1. For the growth trajectory (large dashed line at top) when gL = 4.50%, violation starts with Ba1 so the trajectory stops at Baa2. Given this pattern, we concluded that greater growth leads to violations at higher quality credit ratings.

For the dotted line trajectory representing the nongrowth test in Figure 3, we find max VL = $10.633 M at the OCR of A3. For the dashed line trajectory where gL = 3.12%, the plowback ratio (PBR) of 0.3435 yields gL = 3.12% for an OCR of A3 with max VL = $10.758 M. The latter max VL is a $0.125 M larger than the nongrowth max VL of $10.633 M in the dotted line trajectory. In percentage form, the increase is only 1.18%. The small difference of $0.125 M is not caused by the choice of credit ratings. For example (and as alluded to in our discussion in Section 4.2), if we set PBR so that gL = 3.12% for both lower and higher quality credit ratings, all VL values are lower than the growth max VL of $10.758 M that occurs at A3. Thus, a lower or higher quality credit rating does not necessarily lead to increased firm value, even when growth is the same. Thus, at least for this growth test, targeting the correct credit rating as OCR is important.

As just seen in the small increase of only 1.18% with growth of 3.12%, we inferred that a PT would have to achieve an annual growth rate greater than the historical long-run rate (for a seventy-year period) of 3.12% to make growth more profitable relative to a nongrowth. This inference holds as seen in the solid line trajectory where VL is $11.506 M when gL = 3.90% at a rating of A3 with a PBR of 0.3934. This VL of $1.506 M is an 8.22% increase over nongrowth max VL of $10.633 M. Furthermore, the VL of $11.506 M for gL = 3.90% is 6.95% greater than the max VL of $10.758 M when gL = 3.12%. However, this solid line trajectory reveals that the greatest VL is not $11.506 M that occurs at A3, but $11.527 M where the latter is attained at a rating of Baa2. Nevertheless, if the largest sustainable growth rate is 3.90%, we could not consider $11.527 M as the max VL because it is attained with gL = 4.33%. Thus, we concluded that $11.506 M is still the likely candidate for max VL if 3.90%. Below we explore this candidacy.

If we set PBR so that gL = 3.90% occurs for a lower quality rating of Baa2, we found VL = $11.056 M, which is below $11.506 M when gL = 3.90% for a rating of A3. If we set gL = 3.90% for a higher quality rating of A2, we found VL = $11.588 M, which is above $11.506 M when gL = 3.90% for a rating of A3. While this test yields a larger VL, other tests of higher quality ratings often yield either lower VL values or unfeasible outcomes where the latter occurs because higher quality ratings can lead to the growth constraint being violated. Regardless, if a PT manager can achieve growth of 3.90% at a higher quality rating, then greater firm value can result and determining max VL and OCR becomes a question as to what is the highest quality credit rating that can be attained by a PT when gL = 3.90%. Achieving a higher VL for a higher quality credit rating than A3 for gL = 3.90% differs from what we just saw for the lower growth rate of gL = 3.12% where achieving 3.12% for a higher quality rating than A3 did not increase max VL. Given the difficulty of attaining and maintaining higher quality credit ratings, we would argue that a typical PT has an OCR of A3 if it can attain gL = 3.90%. However, a stronger PT should be able to achieve an OCR of higher quality than A3 when gL = 3.90%, while a weaker PT would have to settle for an OCR of lower quality than A3.