Abstract

This study investigated bank-specific and macroeconomic determinants of bank profitability in Azerbaijan, an oil-dependent economy in transition. A huge drop in oil prices, a significant devaluation of the national currency, and the financial distress were the main motivations of the study. We applied Panel Generalized Method of Moments to the data in the framework of dynamic model of the bank profitability. It was found that bank size, capital, and loans, as well as economic cycle, inflation expectation, and oil prices were positively related to the profitability, whereas deposits, liquidity risk, and exchange rate devaluation were negatively associated with it. We further found that the bank profitability demonstrated moderate persistence and ignoring the country-specific features could lead to bias and poor performance in estimations. The conclusions of this research would aid in setting banking policies towards increasing profitability. This may be supplemented by ensuring strong research departments within the banks tasked with analyzing and forecasting the main macroeconomic indicators. The novel features of the study include utilizing recent economic trends, accounting for country-specific features, and for the first time, examining the effects of the economic cycle on the bank profitability in Azerbaijan. In addition, the study featured proper addressing time series properties of the panel data, and performances of robustness checks for consistency of results.

Keywords:

bank profitability; bank-specific determinants; macroeconomic determinants; panel unit root test; generalized method of moments; panel analysis; an oil-dependent economy; Azerbaijan JEL Classification:

C1; C32; E44; G21

1. Introduction

Financial intermediaries such as banks, investment companies, mutual funds, credit unions, and insurance companies play a vital role in turning the wheels of economic growth, and their sustainability is an integral component of macroeconomic stability. Despite a recent trend of financial disintermediation and growth in market-based finance, the share of the banking sector in the financial system has increased, reinforcing the role of the financial system elements in the economy. The history of world financial crises has attested that the impact of financial development and banks’ intervention on economic stability and growth is acute; and the process of devising and implementing reforms is more complicated than expected.

Since the banking sector is characterized by profit-seeking economic agents, profits are always sought despite the concurrent economic health. As such, profits act as a buffer to withstand the impacts of an economic slowdown, and the more profitable a sector is the more resilient it will be to negative shocks. The resilience of the banking sector is even more crucial in transitional economies that are continuously restructuring their legal and macroeconomic environment to comply with the international policies introduced by the World Bank (WB) and International Monetary Fund (IMF). This resiliency translates into a stronger financial system.

In fact, a sustainable and well-functioning banking system is crucial to resist negative shocks and financial distress, particularly in the case of commodity dependent economies. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Azerbaijan underwent a profound economic transition, which was characterized by a severe economic recession, further aggravated by military aggression and political traumas up until 1995. During the macroeconomic recovery of 1996–2002, the country experienced stable economic growth and lower rates of inflation. The growing efficiency of the Azerbaijani commercial banks in 2003–2008 was accompanied by significant economic growth in the same period. Azerbaijani commercial banks demonstrated a satisfactory level of profitability despite the financial distress in the region up until the recent economic and financial turmoil. There were positive macroeconomic dynamics in 2011–2014: the number of profitable banks in Azerbaijan increased from 30 to 35 and their net profit constituted 370.5 million Manat by the end of 2014. Following substantial GDP growth over the last decade, tumbling oil prices in 2015 had a major bearing on Azerbaijan’s growth prospects. During an economic contraction by 3.8% in 2016 (the first negative growth in two decades), the national currency depreciated by a further 13.4%, following almost 100% devaluation of the national currency vis-à-vis USD in 2015.1 The financial sector of the country has particularly suffered from the decline in oil prices and subsequent rounds of devaluations. The Central Bank of Azerbaijan increased the charter capital requirement for commercial banks from 10 million Manat to 50 million Manat in 2015 (CBAR SB 2015). Banks’ profits were primarily affected by increases in loan loss provisioning and exchange rate movements of Manat, which resulted in a loss of 345 million Manat in 2015. The high level of non-performing loans, limited trust in the national currency, and an inadequate capital ratio have increased the vulnerability of the financial sector (see Ibrahimov 2016 inter alia). In 2016, the number of non-performing loans surged to 21% from 12%. The ratio of loans to the deposit portfolio of Azerbaijan’s banking sector increased to 138.2 points at the average, which is considerably higher than the acceptable global benchmark range of 80–90 points (CBAR SB 2018).

Therefore, 2016 and 2017 witnessed a number of strategic reforms in Azerbaijan, aimed at stabilizing the financial sector and creating a basis for private-sector-led economic growth. A promising step towards alleviating the uncertainty in the banking sector and sanitizing the sector was the establishment of the Financial Market Supervisor Authority (FIMSA) in early 2016.2 FIMSA has taken resolute steps to consolidate the financial sector by revoking the licenses of 11 unhealthy banks, while recapitalizing remaining banks and preparing the ground for the privatization of the International Bank of Azerbaijan in 2018. By the end of 2017, the number of banks in Azerbaijan decreased from 45 (in 2015) to 30. The closure of several other banks is not excluded in 2018, driven by poor asset quality and foreign exchange risks. Moreover, as outlined by the Strategic Roadmap for the development of financial services, additional infrastructure is being established to solve liquidity and capitalization issues of the financial institutions. In this framework, the International Bank of Azerbaijan, Bank Respublika, Xalq Bank, Kapital Bank, PASHA Bank, Rabitebank, Unibank, and Ziraat Bank Azerbaijan created a Credit Bureau that will contain more information on borrowers (utilizing databases of banks, insurance and leasing companies) than the Centralized Credit Registry.3

Following the loss of 1.7 billion Manat in 2016 (of which 1.3 billion Manat are losses from the International Bank of Azerbaijan), the Azerbaijani banking sector restored its profitability in 2017. The aggregate capitalization of banks has grown from 1.9 billion to 3.1 billion Manat. Yet the dollarization, one of the main culprits of the financial distress, remained high: 74.6% of deposits have been in foreign currency as of 1 September 2017.

Considering the recent financial distress and macroeconomic challenges in the country, especially caused by the huge drop in oil prices and the devaluation of the national currency as well as the importance of the banking system in the government’s ongoing effort to diversify the economy, it is essential to investigate the factors affecting the banking sector. Thus, the objective of this study is to examine the impacts of the bank-specific and macroeconomic indicators on the bank profitability in Azerbaijan.

To this end, by taking the availability and quality of the bank-specific data into consideration, we selected 22 banks, including the 10 largest banks4, in Azerbaijan over the quarterly period of 2012Q1–2017Q1 to conduct an empirical analysis. Note that the shares of the selected banks in total in terms of assets, equities, loans, and deposits were 93%, 88%, 92%, and 95%, respectively, in the first quarter of 2017.5 We adopted a dynamic model following the theoretical framework in the bank profitability literature and estimated it using Panel Generalized Method of Moments (PGMM). We found that bank size, capital, and loans as bank-specific variables together with economic cycle, inflation, and oil prices as macroeconomic indicators have statistically significant positive effects on the banks’ profit. However, liquidity risk and exchange rate devaluation are negatively related to the profitability. Moreover, it was found that the profitability exhibited moderate persistence and, thus, the banking sector is quite competitive. We did further robustness tests and revealed that deposits did not increase the banks’ profitability and country-specific features should not be ignored in the empirical analysis.

We think that the conclusions and policy recommendations derived from this study would be useful for bank-level decision-makers: they can consider bank-specific variables that positively and negatively affect profitability. Furthermore, we support establishing competitive research departments to analyze and forecast key macroeconomic indicators accurately.

We believe that our study contributes to the scarce literature on the Azerbaijani banking profitability in several ways. First, this is one of very few studies investigating bank profitability in Azerbaijan. We are aware of only four studies and three of them are dissertations. Second, in the empirical analysis we accounted for oil-dependency of the economy, a fact, which was ignored by the three studies and incompletely addressed in the fourth one. Third, to the best of our knowledge, this study first time examined the effects of the economic cycle on the bank profitability in Azerbaijan. Fourth, the study accounted for the recent economic and financial turmoil (decline of oil prices and the exchange rate devaluation). Fifth, it specified a proper modelling of banking profitability by addressing econometric estimation issues, such as unit root properties of the variables. Finally, we performed two types of robustness tests to ensure that the estimated coefficients are adequately representing bank profitability relationship and thereby increasing the confidence in the subsequent policy recommendations.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 describes the characteristics of the macroeconomy and banking sector in Azerbaijan, while Section 3 reviews the bank profitability studies. Section 4 discusses the determinants of bank profitability. The gathered data, selected model, and applied econometric methods are described in Section 5. We discuss the empirical results, including robustness tests, in Section 6, while Section 7 presents conclusions and policy suggestions.

2. Characteristics of the Macroeconomy and Banking Sector in Azerbaijan

In this section, we will briefly outline the main characteristics of the banking sector and macroeconomic environment of Azerbaijan, an oil-dependent country in transition, which differentiates it from other similar economies. Oil revenues play a major role in the development of the entire economy, including the banking sector. The banking sector grew significantly, alongside other sectors, when the economy experienced an oil boom due to higher oil prices during the pre-2008 crisis period. The banking sector crashed following the oil prices declined significantly since the second half of 2014. This shows that the oil sector and particularly the oil prices have certain implications for the banking sector.

The oil-related activities in the economy are heavily determined by international factors, such as oil prices. In other words, developments and business cycles in the oil sector are determined exogenously. This brings up another characteristic of Azerbaijan, which is that economic activities or economic cycles should be better represented by the non-oil sector rather than total GDP as the oil sector behaves exogenously. For example, Hasanov and Huseynov (2013), among others, considered the use of non-oil GDP instead of the total in their bank-related research. This also holds true when it comes to measuring the impact of economic cycles or activities on the bank profitability.

Thus, the above-mentioned two characteristics originate as a result of being an oil-dependent and should be taken into consideration separately in the empirical analysis.

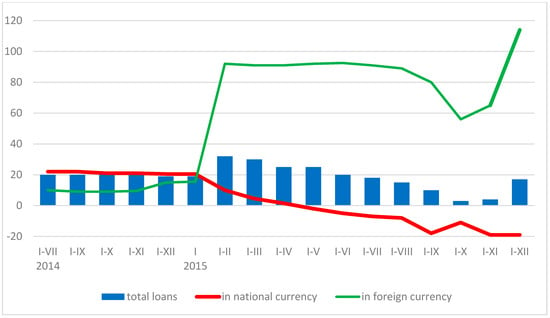

Another important consideration of the macroeconomic environment for the bank profitability is the exchange rate. Azerbaijan, like other oil-dependent transitional economies such as Russia and Kazakhstan, followed the fixed exchange rate regime to prevent the local currency from appreciation over a long period until the oil prices crashed in 2015. One U.S. dollar was equal to 0.78 Manat on average during the pre-2015 period. A strong and appreciating national currency brought confidence and prosperity to the economy, including the banking sector both domestically and internationally.6 However, since it was very costly for the government to keep the fixed exchange rate when oil prices dropped sharply, the decision was to switch to the floating exchange rate regime. The Azerbaijani government devaluated the Manat against the U.S. dollar twice in 2015, which resulted in a significant value loss. First, it was implemented in February, when the Manat was devaluated by 34%, and then in December, when the devaluation was 17%. The Manat lost further value against the U.S. dollar in 2016 and the exchange rate was 1.8 in the first quarter of 2017 (the end of our sample), meaning that the Manat depreciated more than two times. Among other negative consequences, this huge devaluation also hurt the banking sector. Sahminan (2004) and Sahminan (2008), inter alia, discuss how and in which ways the devaluation of a national currency leads to failure of banks regardless of their sizes and profit margins. In fact, the number of banks was reduced from 45 in 2015 to 30 in 2017. The devaluation negatively impacted the banking sector in the following ways in Azerbaijan: (a) it directly increased the interest payment for loans that the Azeri banks borrowed in U.S. dollar and Euro from international financial institutions and foreign banks; (b) the loans that they provided in U.S. dollars became very costly for customers to pay back and, thus, very risky; (c) depreciation of the Manat led to a deposit run as the banks’ customers lost their confidence in the banking system. The first devaluation of the Manat in February 2015, had a dramatically negative impact on the compositions of deposits and loans and consequently the banks’ profitability. The Figure 1 demonstrates how Azerbaijani banks became sensitive to the exchange rate issue.

Figure 1.

Growth rates of loans, %. Source: Reproduced from CBAR SB (2015).

As for the sector related characteristics of the banks, the following points should be discussed.

The main sources of banks’ funds (including their investment and loans) were not the deposits, which banks attracted from the customers, but the debts that they borrowed from the foreign banks and international financial institutions, such as the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the International Financial Cooperation, and German financial institutions.7 According to the Central Bank’s report, foreign debt and its ratio to assets have been increasing significantly since 2012 (CBAR 2015). Additionally, the share of deposits in total liabilities decreased, while foreign liabilities increased since 2012.8 According to the Statistical Bulletin of the Central Bank of Azerbaijan, deposits constituted only 49.9% of total liabilities of the banks in 2015 (CBAR SB 2015). Banks attracted deposits because it is one of the services that they usually should fulfill. This can be easily observed if one looks at the loan and deposit rates over time. There is a large gap between the two with loans being much higher than deposits. For example, the interest rate on loans offered by commercial banks ranged from 16% to 34%, while the deposit rate dropped to 8% in 2013 (e.g., see Bayramov 2014). The loan rate was high because there was a high demand for loans from the households and the private sector. The deposit rate was quite low because, again, the banks in Azerbaijan do not considered deposits as a main source of loans. We can also observe it by looking at the ratio of credits to deposits for Azerbaijani banks, which has been higher than 140% since 2012.9 Thus, it is expected that loans were positively associated with banks’ profitability, but it is hard to say the same thing for deposits. One might even expect a negative relationship as deposits are considered banks’ liabilities and they have to pay interest against them to deposit holders.

3. Literature Survey

Determinants of banking sector profitability can be traced to the pioneering studies by Short (1979), Bourke (1989), and Molyneux and Thornton (1992) on European banks. Since then, a number of studies have explored banking profitability in developed and developing economies. Some studies examined bank performance measures in a group of transition economies, e.g., Drakos (2003), Roman and Sargu (2015), Fries and Taci (2002), Haselmann and Wachtel (2007), and Capraru and Ihnatov (2014). However, none of them included Azerbaijan in their panel set. In this regard, studies investigating banks’ profitability in Azerbaijan, a net oil exporter in transition, are very limited. Yet, identifying profitability factors in commercial banks and their contribution to economic growth becomes a turning point for natural-resource dependent economies attempting to diversify their economic activities. To the best of our knowledge, there have only been four studies analyzing bank profitability in Azerbaijan using bank-specific and macroeconomic indicators. Three of them are dissertations; only one is a peer-reviewed journal article. This in itself shows that the gap in this area is quite large. What follows is a constructive review of these four studies.

Seferli (2010) examined the effects of macroeconomic factors on the performance of the banking sector in Azerbaijan over the period 2003–2008, using data from 29 commercial banks. He applied an unbalanced panel with individual random effect to the 109 data points. The dependent variable was bank performance and the independent variables were GDP and inflation. We acknowledge that this is one of the pioneer studies examining bank performance in Azerbaijan. The author found the negative impacts of GDP and inflation to be statistically insignificant and significant, respectively. He did not provide explanations for why GDP and inflation have negative effects on bank performance. Finding a negative effect of GDP on banks’ performance was not consistent with the literature, as the author himself noted. This issue, alongside other findings of the study might be associated with some shortcomings. First, the author did not check the non-stationarity properties of the employed variables but the Azerbaijani GDP seemed to be non-stationary over time, as Figure 15 in Seferli (2010) illustrated. If the other variables are non-stationary too, a cointegration analysis should be conducted first. Then, an error correction model or simple regression should be estimated depending on whether there is a cointegrated relationship among the variables. Second, we think that the estimated specification suffered from the omitted variable bias problem. Specifically, bank performance is not only influenced by macroeconomic indicators but bank-specific indicators as well, such as bank capital, assets, and credit risk, which may play significant roles in determining profitability. However, the study only considered the bank performance as a function of GDP and inflation. Third, the bank profitability literature shows a dynamic relationship between bank performance and profitability. In other words, the past value of a bank’s performance usually has a significant impact on its present value. In this regard, one should estimate a dynamic specification of bank performance rather than a static one.

Nuriyeva (2014) investigated the profitability of 15 commercial banks in Azerbaijan over the period 2006–2012. The author measured the bank profitability using three main indicators, namely the return on assets, return on equity, and net interest margin, which commonly used in the literature. As for explanatory variables, the author used bank-specific and macroeconomic indicators. For bank-specific variables, she employed capital adequacy, asset quality, management quality, earning ability, bank liquidity, and bank size. As a macroeconomic variable, she used per capita GDP only. She employed a fixed-effects panel model. The author found that all the above-mentioned bank-specific variables had statistically significant positive effects on the return on assets with the exceptions of management quality and earning ability. For the former the impact was negative and statistically significant, while for the latter, the influence was also negative but not statistically significant. Moreover, she found that the GDP effect was negative and statistically significant. It has to be mentioned that this study is one of very few studies exploring the impact of bank-specific and macroeconomic indicators on bank profitability in Azerbaijan. Additionally, we appreciate that the author did an enormous amount of work investigating the impacts of a number of bank-specific and macroeconomic indicators on three different measures of banks’ profitability. Alongside all these merits, we have some concerns about the study. First, the study did not provide an explanation of why it expected and estimated a negative impact of GDP on bank profitability in Azerbaijan, which is counterintuitive to common sense in the literature. We think that this finding was associated with some issues in the analysis. For example, the study found that the natural logarithmic expression of GDP is stationary, i.e., integrated order of zero, I(0), but the literature usually finds that the integration order of GDP is one, I(1) or the variable is trend-stationary. Second, the empirical studies usually use growth rates or the cyclic component of GDP rather than its level because the level of GDP is I(1), i.e., a non-stationary process. Third, we could not find explanation for the finding, i.e., why and how the GDP influences the banks’ profitability in a negative way. Lastly, the study estimated a static panel model, whereas the existing literature argues that bank profitability demonstrates persistence over time and, hence, a dynamic specification should be considered in the empirical estimations.

Ibrahimov (2016) explored the impacts of bank-specific and macroeconomic variables on the profitability of 41 banks over 2012–2015. The results from the static panel model estimations showed that bank size and bank capital both had a positive influence on the return on assets, whereas liquidity risk was negatively associated with it. As macroeconomic variables, exchange rate devaluation and oil prices exerted negative and positive effects on profitability, respectively. It is noteworthy that this is only the study investigating the impact of exchange rate as well as oil prices on the bank profitability in Azerbaijan. However, one should consider the results of this study with some caution. For example, the study did not perform a unit root test and usually variables such as oil prices and exchange rate are non-stationary over time. Second, the study only estimated static models of bank profitability. However, recent studies show that bank profitability persists over time as discussed above. The study did not consider any macroeconomic variable to measure the impact of economic activity or business cycles on the profits of the banks.

One of the most recent and comprehensive studies directed at transition countries of the former USSR was conducted by Djalilov and Piesse (2016) for the period of 2000–2013 using unbalanced data from 275 banks of 16 countries including Azerbaijan. They used capital, credit risk, cost, bank size, squared sum of bank market share (HHI), and lagged value of return on assets as bank-specific variables. GDP growth and inflation, their lagged values, government spending, and fiscal and monetary freedom were considered macroeconomic indicators. The study estimated specifications of different combinations of the above-mentioned variables employing Arellano and Bover (1995) type and random-effect type Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) estimators. The study found that the lagged value of return on assets, capital, bank size, and HHI had statistically significant positive impacts on the banks’ profitability while the credit risk exerted a negative effect. Regarding macroeconomic variables, government spending and fiscal and monetary freedom, as well as their squared terms, were found to be all negative and statistically significant, while GDP growth and inflation were both positive but statistically insignificant. We should mention that, compared to the first three studies, this research employed the correct specifications by including the lagged value of the return on assets and a relevant estimator, i.e., GMM, in the analysis. Our only the concern about this study, that might undermine robustness of its findings, is the conclusions from the unit root exercise. Interestingly, and opposite to other empirical studies, the study found that bank size, which was a natural logarithm of total assets, is a stationary variable. The same concern might also be true for government spending, fiscal freedom, and monetary freedom, which usually drift over time.

Alongside the study-specific shortcomings discussed above, we would also like to mention some missing points of the earlier studies, which are common for all of them. First, none of the earlier studies, in which the Azerbaijani banks were considered have accounted for country-specific features, except Ibrahimov (2016), who did it partially. That is, the country is not only characterized by being in transition, but also being an oil-dependent. Therefore, non-oil economic activity should be taken as a measure of economic activity or business cycle, while the impact of the oil sector should be accounted for separately. Second, none of the earlier studies, except Ibrahimov (2016), included the exchange rate in their analyses, which is one of the key macroeconomic indicators for the Azerbaijani economy, including the banking sector. Third, earlier studies did not conduct a robustness check to ensure that their findings are robust to different considerations, which is very important component of making proper policy recommendations.

We address all the above-mentioned common and study-specific shortcomings of the earlier research in our study. Hence, we hope that our research contributes to the existing literature considerably.

4. Determinants of Bank Profitability

Bank performance can be measured by return on assets (ROA) and/or the return on equity (ROE). In the literature, depending on the research question, either the former or the latter or both measures can be considered. Demirguc-Kunt and Huizinga (1998), Athanasoglou et al. (2008), Flamini et al. (2009), Bashir (2003), Sastrosuwito and Suzuki (2011), and Davydenko (2010) discuss how one can prefer ROA to ROE as the latter disregards risks associated with high leverage and financial leverage. Additionally, Rivard and Thomas (1997) suggest that a high-equity multiplier does not distort ROA and, hence, appears to be a better measure to represent the ability of the firm to generate returns on their portfolio assets. Therefore, many studies, including those for transition economies, select ROA as the measure of profitability (Demirguc-Kunt and Huizinga 1998; Athanasoglou et al. 2008, 2006; Dietrich and Wanzenried 2011; Djalilov and Piesse 2016; Nuriyeva 2014; Ibrahimov 2016; Curak et al. 2012; Petria et al. 2015; Capraru and Ihnatov 2014; Davydenko 2010). Thus, we select ROA as a measure of bank profitability, which is our dependent variable in the empirical estimations.

4.1. Bank-Specific Determinants

Capital. A strong capital structure is one of the major variables providing additional strength to foster profitability as well as withstanding financial instabilities. In this regard, a number of studies, including those for transition economies, found a positive impact of bank capitalization on profitability (Berger 1995; Athanasoglou et al. 2008; Demirguc-Kunt and Huizinga 1998; Petria et al. 2015; Nuriyeva 2014; Djalilov and Piesse 2016; Capraru and Ihnatov 2014; Fries and Taci 2002).

Size.Athanasoglou et al. (2008) discuss how, generally, it has been proven that the profitability effects of a growing bank size are expected to be positive. Conventional knowledge dictates that financially leveraged banks are more profitable as their size increases, but more susceptible at the same time due to risks resulting from debt markets. Hence, there is no consistency in the empirical evidence from previous studies analyzing the impact on profitability. Nuriyeva (2014), Djalilov and Piesse (2016), and Petria et al. (2015) found a positive impact of bank size on its profitability for transition economies including Azerbaijan. Most of the bank profitability studies use total assets to proxy bank size, following seminal papers such as Demirguc-Kunt and Huizinga (1998) and Athanasoglou et al. (2006, 2008). We follow the same approach.

Liquidity risk. According to the theory, an increased exposure to credit or liquidity risk results in decreased profitability and, thus, there is a consensus on the negative effect of the risk on the bank profitability (Athanasoglou et al. 2008 inter alia). This arises when an asset or a loan becomes irrecoverable in the case of outright default or delay in the servicing of the loan. Several influential studies, including those on transition economies, have found a negative association between the credit or liquidity risk and profitability (Athanasoglou et al. 2006, 2008; Djalilov and Piesse 2016; Petria et al. 2015; Capraru and Ihnatov 2014; Roman and Sargu 2015; Davydenko 2010) and conclude that increased exposure to credit risk is generally associated with diminishing bank earnings.

Loans. A higher loans to assets ratio is expected to affect profitability positively unless the bank takes on an unacceptable level of risk. A positive impact is expected as interest from loans is one of the main sources of a bank’s profit. Athanasoglou et al. (2008), Davydenko (2010), and Bashir (2003) find a positive effect of loans on profitability.

Deposits. On the one hand, deposits can become one of the main sources of banks’ funds that they invest to generate income. In this regard, deposits are positively related to bank profitability. On the other hand, deposits are liabilities for banks and, hence, a higher level of deposits may imply more payments for the deposit holders and thus less profit for the bank. Apparently, the effect of deposits on bank profitability is ambiguous and heavily depends on the bank and macroeconomic characteristics of the country considered. For example, Davydenko (2010) found a negative effect of deposits on bank profitability in Ukraine, one of the transition economies. The same was also found by Demirguc-Kunt and Huizinga 1998) and Alper and Anbar (2011), while Sun et al. (2017) found a positive relationship.

4.2. Macroeconomic Determinants

The main macroeconomic variables that the bank profitability literature usually considers are measures of economic activity, price level, interest rate, and exchange rate. This list should be shortened or lengthened depending on the characteristics of the country or country group selected for analysis. In this regard, we employ the following macroeconomic variables in this research.

Cyclical output. Economic activity, which is measured by the growth rate or cyclical component of GDP, is believed to influence bank profitability positively (Athanasoglou et al. 2006, 2008; Dietrich and Wanzenried 2011; Flamini et al. 2009; Goddard et al. 2004; Trujillo-Ponce 2013; Davydenko 2010). As Athanasoglou et al. (2008) discuss, the bank profitability literature has not concentrated specifically on analyzing the impact of cyclical components of output, a proxy for business cycle, on profitability. Consequently, there are very limited studies, constituting a huge gap in the literature. Hence, we use cyclical components of output in this research, following Athanasoglou et al. (2008). Demand for loans and other bank services increases during cyclical upswings and decreases during downswings. We think that the cyclical component is better than the growth rate as the former reflects both upswings and downswings. Our main economic activity measure in this research is the cyclical non-oil GDP because of the country-specific features discussed above. At the same time, we will use the cyclical component of the total GDP for a robustness check.

Inflation expectation. A considerable number of studies argue that the extent to which inflation affects bank profitability depends on whether it is anticipated or not (Perry 1992; Flamini et al. 2009; Li 2007). A positive impact of inflation on bank profitability can be explained in two ways. First, if inflation is anticipated, then banks’ management can adjust their interest rates properly in the sense that their profit will be higher than what they will lose from the increase in costs caused by the inflation. The second way is asymmetric information about inflation expectation. This is more likely the case in transition economies including Azerbaijan. The banks’ management has more channels through which to learn about what the expected inflation would be than the banks’ customers do. This asymmetric knowledge situation means the management is in a better situation and benefits from the coming inflation. Thus, Demirguc-Kunt and Huizinga (1998) and Molyneux and Thornton (1992) found that inflation has a significantly positive impact on profitability due to the additional profits extracted from the asymmetric information. Also, Djalilov and Piesse (2016), Petria et al. (2015), Capraru and Ihnatov (2014), Athanasoglou et al. (2006), and Munteanu (2012) found positive impacts of inflation on bank profitability for European countries, where a number of transition economies are included. On the contrary, Seferli (2010), Fires and Taci (2002), Munteanu (2012), and Davydenko (2010) conclude that, with rising inflation, bank profitability declines.

Change in exchange rate. This is the change in the Manat price of U.S. dollars, meaning that an increase is a depreciation of the Manat. We believe that this is one of the macroeconomic indicators that influence the bank sector in Azerbaijan, for the reasons we discussed in Section 1 and Section 2. Also, some earlier studies on transition economies considered the variable in their analyses. Ibrahimov (2016) and Bayramov (2014) found that the devaluation of the Manat had a significantly negative influence on the profitability of Azerbaijani banks. On the contrary, Davydenko (2010) concludes that the depreciation of hryvna increases the profitability of the Ukraine banks.

Change in oil price. It is worthless to argue that oil price dynamics are crucial for oil-exporting countries. It takes on more importance if an oil exporter is a price taker rather than a price setter in international oil markets like Azerbaijan. As discussed above, an increase in the oil price has positive implications for the entire economy, including its banking sector. Ibrahimov (2016) also finds a statistically significant positive effect of the oil price on the profitability of Azerbaijani banks.

Table 1 summarizes the variables we selected for our bank profitability analysis.

Table 1.

Variables used in the empirical analysis.

5. Data, Model, and Econometric Methodology

5.1. Data

Our bank-specific data, i.e., net profit, total assets, total equity, total loans, total deposits, and short-term funding, came from 22 Azerbaijani banks over the quarterly period from the first quarter of 2012 to the first quarter of 2017. Note that the number of banks and time period are considered based on data availability and quality issues. Our panel covers the following banks: Pasha Bank, RabitaBank, Bank of Baku, Expressbank, Demirbank, Accessbank, ASB Bank, Muganbank, Nikoil Bank, VTB bank Azerbaycan, Bank BTB, Atabank, Xalq Bank, AG Bank, NBC Bank, Bank Respublika, Kapital Bank, Bank Avrasiya, Azer Turk Bank, Unibank, Bank Silk Way, and Turanbank.10 As discussed in Section 1, the selected banks represent a significant portion of the banks in Azerbaijan, in terms of number, i.e., 22 out of 31, as well as their shares in total bank indicators. Hence, we believe that our selected sample is a better representation of the banking sector in Azerbaijan. The data are mainly gathered from the web page of the Azerbaijani banks (www.banco.az). This web page brings together all the main indicators of the banks on a quarterly basis.11

Regarding macroeconomic variables, we collected them over the quarterly period of the first quarter of 2012 to the first quarter of 2017, being consistent with the bank-specific variables. Total and non-oil GDP values, seasonably non-adjusted million Manats at 2005 prices, are taken from the State Statistical Committee of Azerbaijan Republic (SSCAR 2018). 12 We collected Consumer Price Index and Manat/USD exchange rate from the statistical bulletins of the Central Bank (CBAR SB 2018). The former is rebased to the year of 2005. Oil price is the U.S. dollar price per barrel of the Brent crude spot and we retrieved it from the United States Energy Information Administration (US EIA 2018).

5.2. Model

There is a consensus in the literature that bank profitability persists over time (for example, see Athanasoglou et al. 2008; Garcia-Herrero et al. 2009; Dietrich and Wanzenried 2011). Therefore, a proper model to estimate the impacts of bank-specific and macroeconomic variables on the bank profitability is one that includes the lagged value of the dependent variable. It is noteworthy that many studies on transition economies, including those on Azerbaijan, ignored this point (e.g., see Seferli 2010; Nuriyeva 2014; Ibrahimov 2016; Drakos 2003; Petria et al. 2015; Capraru and Ihnatov 2014; Athanasoglou et al. 2006). In this regard, we use a proper specification in the empirical analysis and, hence, we believe that our estimation results represent the dependence of bank profitability on its drivers in Azerbaijan more adequately than those of earlier studies. Thus, we can express our model as follows:

where is the profitability of bank i at time t and is one period lagged profitability; c is a constant term; indicates the speed of adjustment to equilibrium path; and are the vectors of bank-specific and macroeconomic variables; is the disturbance, which contains the unobserved bank-specific effect and the idiosyncratic error, where independent of ; and are the coeffcieints to be econometrically estimated; i = 1, 2, 3, …, N and t = 1, 2, 3, …, T.

If the value of ranges from 0 and 1, this indicates that the profit persists over time, but it will eventually go back to its normal (average) level. The bank sector is more or less competitive if the value is close to 0 and 1, respectively.

5.3. Econometric Methodology

In the empirical analysis, we will proceed as follows. First, we will check the stationarity of our variables using unit root tests. If the variables, and especially our dependent variable (ROA), are found to be non-stationary, then we will use a cointegration test as a next step to see whether the variables are cointegrated. If they are cointegrated, then we first estimate the long-run relationship and then the short-run dynamics among them. If our variables, particularly ROA, are stationary, then we will estimate Equation (1), i.e., the dynamic model. Table 2 summarizes the first and second generations of the panel methods that we can potentially employ in the empirical analysis.

Table 2.

Panel methods.

We would like to discuss the test for the unit root a bit more as it is one of the important issues for the time series properties of the panel data (Campbell and Perron 1991). It is noteworthy that only very few bank profitability studies checked the stationarity of their variables. We think this is an important step because the non-stationarity of variables might yield spurious estimation results, as indicated in the cointegration and unit root theories (for example, see the discussion in Engle and Granger 1987). The studies that checked the stationarity of variables only employed Maddala and Wu (1999)’s Fisher-type test. However, we will use different types of panel unit root tests for robustness. Precisely speaking, in addition to Maddala and Wu (1999) test, which is an individual unit root test assuming heterogeneity, we will employ Levin et al. (2002) test, which is a common unit root test assuming homogeneity. Moreover, we will use Pesaran (2007), which is also an individual unit root test assuming heterogeneity and accounts for the cross-sectional dependency that might be exhibited in our data.

Note again that if we conclude that our variables, especially ROA, are stationary, we will estimate Equation (1), which is a dynamic model as it includes the lagged value of the dependent variable. Therefore, the Least Squares estimation method produces inconsistent and biased estimates (see Baltagi 2001, inter alia). Another issue in estimating bank profitability using Equation (1) is endogeneity. One can argue that some variables in the right-hand side of Equation (1) are endogenous. For example, Garcia-Herrero et al. (2009) and Dietrich and Wanzenried (2011), inter alia, note that more profitable banks can increase their equity and size, which in turn will increase profitability. This feedback loop might also be true for profitability, loans, and deposits. The third issue in estimating Equation (1) is whether fixed effect or random effect should be selected for individuals, i.e., banks. In order to address all the above-mentioned issues, we employ Panel GMM (see Arellano and Bond 1991; Blundell and Bond 1998 for example), following Garcia-Herrero et al. (2009), Dietrich and Wanzenried (2011), Athanasoglou et al. (2008), Djalilov and Piesse (2016), Davydenko (2010), and Curak et al. (2012).

6. Empirical Results

Table 3 presents some descriptive statistics of our bank-specific and macroeconomic variables.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics.

The bank-specific variables are ratios, except for bank size, and the macroeconomic variables are either changes, growth rates, or deviation from the trend line, as documented in Table 1. Therefore, it is less likely that they are trending over time. In this regard, one should not expect that the trend is a part of the data generation process for them and, hence, we would not include it in the unit root testing. Nonetheless, we also perform unit root tests in the case of trends alongside the other two options, which are individual intercept only and no intercept and no trend.

Although we perform all three test options for robustness, one of the options can be preferred based on the mean value of a variable at hand given in Table 3. In this regard, the Individual Intercept and No Trend options would be more relevant for BS, BC, LRISK, ROTLTA, ROTDTA, INF and OILPD as their mean values are not close to zero. Likewise, the No Intercept and No Trend options would be preferable for ROA, CGDPN, CGDP and ERD as their mean values are very close to zero. This approach should be considered in making a final decision on the integration order of a given variable, i.e., whether it is stationary or not. Note, however, that in some circumstances making a decision is more difficult and requires further investigation to extract more information. Such information can be derived from a careful and detailed inspection of the graphical illustrations and unit root test results of a given variable across the banks as well as common sense consideration about the integration order of the bank specific and macroeconomic variables in the literature.

The panel unit root test results are reported in Table 4.

Table 4.

Panel unit root test results.

For BS, ROTLTA, BC, LRISK, ROTDTA, INF, and OILPD, following the discussion above, we prefer the test results from the option Individual Intercept and No Trend. We notice that at least two of the three tests’ results are in favor of the stationarity of the variables, apart for the first two variables. We further inspect the time series and unit root test results of BS and ROTLTA for each of the 22 banks. Graphics illustrate that BS variable is upward trending for 18 out of 22 banks, meaning that it contains either a stochastic or a deterministic trend. The deterministic trend is significant in nine banks’ BS unit root test equations, while for another nine banks it is not significant. For all of them, the null hypothesis of unit root cannot be rejected. For four banks’ BS, we can reject the null hypothesis. Our conclusion on panel BS is that it can be considered a non-stationary variable, but this is ambiguous. As for ROTLTA, we briefly note that the same type of inspections and an additional panel Fisher-Phillips Perron test show that it can be considered integrated order of zero that is a stationary variable. Moreover, all three tests’ results for the variable in panel C support this consideration.

For ROA, CGDPN, CGDP, and ERD, it can be straightforwardly concluded that they are stationary following the discussion above, i.e., preferring the test results from the option of No Individual Intercept and No Trend.

Thus, our conclusion for the unit root properties of the variables is that all of them are stationary, except BS, which is ambiguous.13 Athanasoglou et al. (2008), inter alia, note that if the dependent variable is stationary, bank size variable can still be included in Equation (1) although it is non-stationary. Thus, our research decision for BS is that we keep it in the estimations if it is statistically significant, i.e., if it contributes to the explanation of ROA, our dependent variable.

We estimate Equation (1) following the instructions provided by the references in Section 5.3. Table 5 documents the estimation results.

Table 5.

GMM estimation results.

As can be seen in the table, all the bank-specific and macroeconomic variables in the estimated specification are statistically significant. Additionally, their coefficients have the expected signs. Moreover, the coefficient on the one-period lagged ROA is in the expected range, as discussed in Section 5.2. Furthermore, the post-estimation tests show that over-identification restriction is valid; there is no auto-correlation in the second order of the residuals and they are normally distributed at the 5% significance level. Based on these, we can conclude that the estimated model is well behaved and can be used for discussions and policy recommendations.

What follows is a discussion of the results obtained. According to the estimated coefficient on the one-period lagged ROA, the profitability of the bank sector in Azerbaijan persists in moderate magnitude as the coefficient is closer to zero than unity. This implies that departures from a perfectly competitive market structure is little meaning that the bank sector in Azerbaijan can be considered fairly competitive. We think that the finding is supported by the realities of the Azerbaijani bank sector in the sense that there are 31 banks operating in the country. This number is fairly large and indicates that the sector is quite competitive. Looking at the neighbor countries who have a similar land area and characteristics: Georgia, Armenia, and Turkmenistan had 17, 17, and 11 banks, respectively, in the first quarter of 2017. Moreover, it is noteworthy that the CBAR reports state that the banking system is quite competitive and there are too many banks in Azerbaijan compared to other similar economies (CBAR AR 2018). Comparing our findings with those obtained by the earlier research, three out of four studies investigating bank profitability in Azerbaijan did not include the lagged value of profitability in their estimation, as we discussed in Section 3. Consequently, we can only compare our findings with those of Djalilov and Piesse (2016). Their GMM-based estimation is around 0.68, which is higher than ours. There are a number of reasons for this difference. First, their estimated coefficient is not only representative of Azerbaijani banks, but representative of banks from eight transition economies, namely Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Moldova, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan. Second, we could not find information about how many and which Azerbaijani banks they considered in their research. Third, their data are annual and cover the period 2000–2013, while our data are quarterly and span 2012Q1–2017Q1. Fourth, there are some concerns about their econometrics, such as the unit root, as we discussed in the Literature Review section. Regarding findings for other transition economies, Davydenko (2010) found it 0.25 for Ukraine, Curak et al. (2012) found it to be 0.047 for Macedonia.

Table 5 indicates that bank size, as measured by the natural logarithm of total assets, has a statistically significant and positive impact on the profitability. In other words, more assets lead to more profit in the Azerbaijani banking sector. One explanation for this positive relationship is the theory of economies of scale. This theory suggests that gains from economies of scale will decrease over time as the economy approaches a higher level of sophistication in terms of technology, innovation, and productivity. In this regard, if we look at the current situation of the Azerbaijani banks, they are still a long way from such sophistication (see the discussion in Ibrahimov 2016, inter alia). This means that there is a gain from the economies of scale for the banks. This finding implies that Azerbaijani banks do not want to increase their size by means of their profits; inversely, they use all their assets to make more profit. Regarding the findings of earlier studies on Azerbaijani banks, although these studies suffer from some specification/estimation issues, Nuriyeva (2014) found it to be 0.036 for 43 banks over 2006–2012, Ibrahimov (2016) estimated it at 0.185 for 41 banks over 2012–2015; and Djalilov and Piesse (2016) found the coefficient range to be 0.070–0.191 for banks from the eight transition economies over 2000–2013.

Bank capital, measured by total equity over total assets, appeared to have a positive and significant influence on the bank profitability, as we expected. We discussed in Section 4.1 how a strong capital provides additional strength to foster profitability as well as to resist financial instabilities. The finding shows that Azerbaijani banks have enough funds and equity capital to support business operations and make a profit as well as minimize expected bankruptcy costs. Another explanation for the positive effect is that when banks have enough capital they gain more credibility and appear to have better future prospects, which would foster their business and operations and, thus, profits. The positive relationship between bank capital and profitability also implies, among other things, that regulatory interventions by the Central Bank of Azerbaijan over 2012Q1–2017Q1 were successful in the sense that the capital levels of the bank allowed them to make a profit. Just to compare our estimated coefficients with those of earlier studies on the Azerbaijani banking sector: Nuriyeva (2014), Ibrahimov (2016) and Djalilov and Piesse (2016) estimated it being 0.193, 0.065, and around 1.2, respectively.

We find that loans, measured in total loans to total assets, have a statistically significant and positive relationship with bank profitability. This is expected and thus we think it does not need more explanation. More loans means more interest, which is one of the main sources of banks’ profit. The positive finding implies that non-performing loans in the Azerbaijani banking sector are not strong enough to lower the profitability. The earlier studies on Azerbaijani banks did not measure the profitability effects of total loans to total assets.

According to the estimation results in Table 5, liquidity risk, measured as a ratio of total loans to total deposits and short-term funding, exerts a negative and statistically significant effect on the profitability. This is also a theoretically expected relationship. We think that this finding is reasonable for Azerbaijani banks, as discussed in Section 2: the loans to deposits ratio is quite high, with a mean value of 1.9. This shows that (a) banks’ loans are not sufficiently supported by their deposits and (b) they use borrowed money, which is reloaded at a higher interest rate. The high ratio also implies that there can be a high risk embedded in the banks’ activity because they do not have enough liquidity to cover any unexpected fund requirements. These are the points, among others, through which high-liquidity risk can lower the profitability in the Azerbaijani banking sector. Regarding the findings of the earlier studies on Azerbaijan, only Ibrahimov (2016) used this ratio, and his estimated coefficient was −0.001.

Turning to the macroeconomic variables, all four variables have the expected signs and high statistical significance. We find that the bank profitability is pro-cyclical to the economic activity measured in the cyclical component of the non-oil GDP. This is quite reasonable finding and does not require a lot of explanation: the banks can provide more loans to and attract more deposits from the private sectors and households as well as expand their other services and operations during upswings. This is the opposite during downswings, such as the period of low oil prices that began in the second half of 2014. As to specific features of Azerbaijan, not only the private sector but also the households are very prone to bank loans (see CBAR statistical bulletins) even when they have sufficient income to materialize their projects. As mentioned above, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study investigating the bank profitability effects of the business cycle in Azerbaijan. Earlier studies used either GDP or GDP per capita or their growth rates. Seferli (2010) used total GDP and found its coefficient to be −0.001 and statistically insignificant. Although the author himself stated that his finding is not theoretically expected, he did not provide explanation for the finding. Nuriyeva (2014) also found a negative coefficient for GDP per capita, i.e., −0.006 but statistically significant. Like Seferli (2010), the study did not provide any explanation for the finding. Lastly, Djalilov and Piesse (2016) employed GDP growth rates and found mixed—that is, positive and negative—effects, but all statistically insignificant without any explanations.

According to Table 5, the inflation expectation is positively related to the bank profitability. This shows that the banks in Azerbaijan are able to manage the inflation expectation to increase their profits. It implies that banks increase their interest rates and the cost of other services more than just for offsetting the additional burden coming from inflation. When it comes to the question of how they accurately predict coming inflation, we do not think that it is a result of proper analysis and forecasting of inflation since they do not have well-established macroeconomic analysis departments to do this. As was discussed in Section 4.2, we think that this is a result of asymmetric information on inflation expectations. Precisely speaking, banks’ management have more personal channels to official agencies to learn about coming inflation rather than banks’ customers. Among the earlier studies, only Seferli (2010) and Djalilov and Piesse (2016) included inflation in their analysis. The former study found a statistically negative impact of inflation (−0.058), while the latter found that the influence of lagged inflation was unstable across their specifications.

As we anticipated, the expected changes in the Manat’s exchange rate have a negative impact on bank profitability. Changes in the exchange rate were almost zero until the first quarter of 2015. This stability was a continuation of an earlier tendency, starting in the early 2000s, as a result of a fixed exchange rate policy with the strong Manat (on average, 1 USD = 0.78 Manat). Both households and the private sector in Azerbaijan adapted to such a stable and strong Manat environment and made their decisions, including those related to banks, accounting for this. However, all of a sudden, the CBAR devaluated the Manat by by 34% in the first quarter of 2015, as discussed in Section 2. It was a big shock to the entire economy, including the banking sector. Additionally, it created uncertainty and then a lack of confidence in the national currency when the CBAR did the next round of devaluation in the fourth quarter of 2015, in which the Manat lost its value against the U.S. dollar by 17%. The Manat continued in its depreciation path, with 29% in the first quarter of 2016, then it appreciated by 5%, but depreciated again by 17% until the first quarter of 2017. The exchange rate was 0.78 in the first quarter of 2012, while it was 1.78 in the same quarter of 2017, meaning that the Manat lost its value more than twice during the period we consider in this research. Evidently, the entire economy was hurt hugely by the “great collapse” of the Manat. As for the banking sector, not only their profits but all the indicators were negatively influenced by this collapse. Turning to the earlier literature, only Ibrahimov (2016) included the exchange rate in his analysis of bank profitability. He found a negative effect of the Manat’s devaluation, with a coefficient of −0.056 over the period 2012–2015. Our finding of −0.477 is much bigger than his estimation. We think that this difference is reasonable as his research did not cover the aggressive devaluation of the Manat, which happened after 2015.

Lastly, we found that changes in oil prices had a positive and statistically significant impact on bank profitability. This finding is attributed to being an oil-dependent country and expected, as we discussed in Section 2. We do not think that the positive bank profitability effect of the oil prices need any explanation given the fact that the oil sector constitutes about half of the economy. Moreover, oil revenues constituted, on average, 70% of total budget revenues, half of Azerbaijani investments, and 30% of total GDP (TAXAZ 2015)14. Following the decline in oil prices since the second half of 2014, the government budget revenue decreased, and consequently, public expenditures were reduced significantly. As for earlier studies, none of them except Ibrahimov (2016) examined the impact of the oil sector (oil revenues, oil price, etc.) on the bank profitability. Ibrahimov (2016) estimated the effect of the oil prices on the bank profitability as being 0.001, while our coefficient is 0.002. We think that the difference between the estimated coefficients is related to the time period and number of banks selected, as well as some shortcomings in the empirical analysis of Ibrahimov (2016), such as not accounting for the non-stationarity of the variables and omitted variable bias as the lagged profitability was not included in the estimations.

Robustness Tests

In order to ensure that the obtained results reported in Table 5 are adequate representations of the bank profitability relationship and can be used for policy recommendations, we carry out a robustness analysis in this sub-section. We performed two types of robustness tests. The first is related to deposits (see our discussion in Section 2) while the second is about ignoring country-specific features.

We discussed some statistical evidence in Section 2 that led us to assume that the deposits may not be positively related to the profitability in the Azerbaijani banking sector. We econometrically test this assumption here. To do so, we estimate Equation (1) by including the ratio of total deposits to total assets, i.e., ROTDTA in it. At the same time, in order to avoid over-parameterization of the specification, and possible endogeneity and multicollinearity issues, we exclude ROTLTA from the specification. Table 6 presents the estimation results.

Table 6.

GMM estimation results with ROTDLA.

As the table presents, the estimated coefficients for ROTDTA and the remaining variables are statistically significant. Additionally, the post-estimation tests indicate that over-identification restriction is valid. Additionally, the residuals of the estimated specification are distributed normally at the 5% significance level and have no auto-correlation issue in the second order. These show that the estimated specification is well behaved. If we compare the signs and magnitudes of the estimated coefficients from the two specifications, reported in Table 5 and Table 6, it can be seen that they are almost the same. Thus, the main messages from the first robustness test are (a) the estimated coefficients of the basic specification, reported in Table 5, are robust to changes in the specifications; (b) it supports our discussion on deposits in Section 2, i.e., Table 6 reports a statistically significant and negative effect of the deposits to asset ratio on the profitability. Note that Davydenko (2010) also found a negative effect of deposits on the bank profitability in the case of Ukraine. Moreover, some seminal studies such as Demirguc-Kunt and Huizinga (1998) found the same.

We mentioned in Section 2 that the impacts of the oil and non-oil sectors on profitability should be considered separately as country-specific features. Now, here as our second robustness test, we check what the consequences would be if we ignored the country-specific features in the empirical estimations of the profitability. To this end, we exclude both the cyclical component of the non-oil GDP and the change in oil price, i.e., CGDPNt and OILPDt from Equation (1) and, instead, include the cyclical component of the total GDP. The estimation results are documented in Table 7.

Table 7.

GMM estimation results with CGDPN.

In Table 7, the magnitudes of the respective coefficients are small compared to those reported in Table 5. Additionally, the significance levels of both the bank-specific and macroeconomic variables decrease. Moreover, the estimated model does not perform well as it suffers from non-normality and auto-correlation as Table 7 reports. Thus, the main findings from the second robustness test are that ignoring country-specific features can lead to bias and statistical insignificance in the estimated coefficients as well as poor model performance.

Our overall conclusion from the robustness tests is that the basic model, reported in Table 5, is quite robust and, hence, we can use it to make conclusions and policy recommendations in the next section.

7. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

Recent financial distress, especially the drastic drop in oil prices and a significant depreciation of the Manat, made it important to investigate the factors affecting banks’ profitability in Azerbaijan. There were only four studies that examined this research topic. However, three of them have not included the above-mentioned issues in their analysis and the fourth addressed them but in an incomplete way. Therefore, there was a need for a research to properly investigate the effects of bank-specific and macroeconomic indicators, including the above-mentioned issues, on the bank profitability in Azerbaijan. To this end, we selected 22 Azerbaijani banks over the period of 2012Q1–2017Q1 based on data availability and quality. We applied a Panel Generalized Method of Moments to the data in the framework of a dynamic bank profitability model.

We concluded that the bank size, capital, and loans as well as the economic cycle, inflation expectation, and oil price increased the banks’ profitability. However, the liquidity risk and exchange rate devaluation lowered it. It was further concluded that the bank profitability in Azerbaijan exhibited moderate persistence, implying that departures from a perfectly competitive market structure were small and, hence, the banking sector is competitive. Robustness tests revealed that deposits were not positively associated with profitability and ignoring the country-specific features could lead to bias and poor performance. Our overall conclusion was that the bank profitability in Azerbaijan is shaped by both bank-specific and macroeconomic determinants.

We believe that the above conclusions and the related policy recommendations would be useful in the decision-making process for the banking sector. For example, the study can provide a clear outlook of bank profitability as a function of bank-specific and macroeconomic indicators. By knowing this, bank-level decision-makers can focus on capital, size, and loans to increase their profitability. At the same time, they should consider that bank profitability in Azerbaijan is sensitive to liquidity risk and therefore, any risk-related activities will disadvantage it. Bank-level policy-makers should also think about how they can manage deposits effectively to switch them from cost-generating to profit-generating activities. Regarding macroeconomic variables, bank-level decision-makers cannot manage them as these variables are beyond their control. However, they should be supportive and put more investment/effort into establishing strong research departments inside the banks to properly analyze and forecast the macroeconomic changes. This would allow them to better manage effects coming from the economic activity, expected inflation, and oil price changes as well as to set preventive measures to protect banks’ profits from further devaluation of the Manat.

Our study provided insights for a more recent time, which covers the oil prices drop and the Manat depreciation. Other novel features of our paper were that it accounted for country-specific features, examined the effects of the economic cycle on the profitability, properly addressed econometric issues such as unit root properties of the data, and performed robustness checks.

Author Contributions

N.B. gathered the data, while N.A.-M. processed the data and F.H. conducted the econometric analysis and interpretations. All the authors contributed to the write-up of the sections.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The views expressed in this study are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of their affiliated institutions. We are responsible for all error and omissions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alper, Deger, and Adem Anbar. 2011. Bank Specific and Macroeconomic Determinants of Commercial Bank Profitability: Empirical Evidence from Turkey. Business and Economic Research Journal 2: 139–52. [Google Scholar]

- Arellano, Manuel, and Stephen Bond. 1991. Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Review of Economic Studies 58: 277–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, Manuel, and Olympia Bover. 1995. Another look at the instrumental variable estimation of error-components models. Journal of Econometrics 68: 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasoglou, Panayiotis, Manthos Delis, and Christos Staikouras. 2006. Determinants of Bank Profitability in the South Eastern European Region. Working Papers 47. Athens: Bank of Greece. [Google Scholar]

- Athanasoglou, Panayiotis, Sophocles Brissimis, and Matthaios Delis. 2008. Bank-specific, Industry-specific and Macroeconomic Determinants of Bank Profitability. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money 18: 121–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltagi, Badi. 2001. Econometric Analysis of Panel Data, 2nd ed. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Bashir, Abdel-Hameed M. 2003. Determinants of Profitability in Islamic Banks: Some Evidence from the Middle East. Islamic Economic Studies 11: 32–57. [Google Scholar]

- Bayramov, Vugar. 2014. What Is Happining in the Banking Sector in Azerbaijan. Baku: Center for Economic & Social Development. Available online: http://cesd.az/new/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/CESD-Article_Banking_Sector_Azerbaijan.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2018).

- Berger, Allen N. 1995. The Relationship between Capital and Earnings in Banking. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 27: 432–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, Richard, and Stephen Bond. 1998. Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics 87: 115–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourke, Philip. 1989. Concentration and other Determinants of Bank Profitability in Europe, North America and Australia. Journal of Banking and Finance 13: 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, John. Y., and Pierre Perron. 1991. Pitfalls and opportunities: What macroeconomists should know about unit roots. In NBER Macroeconomics Annual. Edited by Olivier Jean Blanchard and Stanley Fischer. Cambridge: MIT Press, vol. 6, pp. 141–220. [Google Scholar]

- Capraru, Bogdan, and Iulian Ihnatov. 2014. Banks’ Profitability in Selected Central and Eastern European Countries. Procedia Economics and Finance 16: 587–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CBAR. 2015. The Central Bank of the Republic of Azerbaijan, Financial Stability Review. Available online: https://en.cbar.az/assets/3805/FSR_03.06.2015_final_son.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2018).

- CBAR AR. 2018. The Central Bank of the Republic of Azerbaijan, Annual Reports. Available online: https://www.cbar.az/pages/publications-researches/annual-reports/ (accessed on 17 March 2018).

- CBAR SB. 2015. The Central Bank of the Republic of Azerbaijan, Statistic Bulletin. December. Available online: https://en.cbar.az/assets/4025/NEW_BULLETEN-12-2015_ENG_OK.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2018).

- CBAR SB. 2018. The Central Bank of the Republic of Azerbaijan, Statistic Bulletins. Available online: https://en.cbar.az/pages/publications-researches/statistic-bulletin/ (accessed on 17 March 2018).

- Curak, Marijana, Klime Poposki, and Sandra Pepur. 2012. Profitability Determinants of the Macedonian Banking Sector in Changing Environment. Procedia Economics and Finance 44: 406–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davydenko, Antonina. 2010. Determinants of Bank Profitability in Ukraine. Undergraduate Economic Review 7: 2. [Google Scholar]

- Demirguc-Kunt, Asli, and Harry Huizinga. 1998. Determinants of Commercial Bank Interest Margins and Profitability: Some International Evidence. The World Bank Economic Review 13: 379–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, Andreas, and Gabrielle Wanzenried. 2011. Determinants of bank profitability before and during the crisis: Evidence from Switzerland. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money 21: 307–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djalilov, Khurshid, and Jenifer Piesse. 2016. Determinants of bank profitability in transition countries: What matters most? Research in International Business and Finance 38: 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drakos, Kostas. 2003. Assessing the success of reform in transition banking 10 years later: An interest margins analysis. Journal of Policy Modeling 25: 309–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engle, Robert, and Clive W. J. Granger. 1987. Cointegration and Error-Correction: Representation, Estimation, and Testing. Econometrica 55: 251–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flamini, Valentina, Calvin McDonald, and Liliana Schumacher. 2009. The Determinants of Commercial Bank Profitability in Sub-Saharan Africa. IMF Working Paper No 09/15. Washington: International Monetary Fund (IMF). [Google Scholar]

- Fries, Steven, and Anita Taci. 2002. Banking Reform and Development in Transition Economies. London: European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Herrero, Alicia, Sergio Gavila, and Daniel Santabarbara. 2009. What explains the low Profitability of Chinese Banks? Journal of Banking and Finance 33: 2080–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddard, John, Phil Molyneux, and John Wilson. 2004. The Profitability of European Banks: A Cross-Sectional and Dynamic Panel Analysis. The Manchester School 72: 363–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanov, Fakhri, and Fariz Huseynov. 2013. Bank credits and non-oil economic growth: Evidence from Azerbaijan. International Review of Economics & Finance 27: 597–610. [Google Scholar]

- Haselmann, Rainer, and Paul Wachtel. 2007. Risk taking by banks in the transition countries. Comparative Economic Studies. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=990018 (accessed on 17 March 2018).

- Ibrahimov, Anar. 2016. The Impact of Devaluation and Oil Price on the Banking Sector of Azerbaijan. Master’s dissertation, Porto University, Porto, Portugal, July. Available online: https://sigarra.up.pt/fep/pt/pub_geral.show_file?pi_gdoc_id=779998 (accessed on 1 September 2018).

- Kao, Chihwa. 1999. Regression and residual-based tests for cointegration in panel data. Journal of Econometrics 90: 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, Andrew, Chien-Fu Lin, and Chia-Shang James Chu. 2002. Unit root tests in panel data: Asymptotic and finite-sample properties. Journal of Econometrics 108: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Yuqi. 2007. Determinants of Banks. Profitability and Its Implication on Risk Management Practices: Panel Evidence from the UK in the Period 1999–2006. Nottingham: The University of Nottingham. [Google Scholar]

- Maddala, Gangadharrao S., and Shaowen Wu. 1999. A comparative study of unit root tests with panel data and a new simple test. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 61: 631–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molyneux, Philip, and John Thornton. 1992. Determinants of European bank profitability: A note. Journal of Banking and Finance 16: 1173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, Ionica. 2012. Bank liquidity and its determinants in Romania. Procedia Economics and Finance 3: 993–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuriyeva, Zülfiyye. 2014. Factors Affecting the Profitability of Azerbaijan Banking System. Master’s dissertation, Eastern Mediterranean University, Gazimağusa, North Cyprus, Turkey, July. Available online: http://i-rep.emu.edu.tr:8080/xmlui/bitstream/handle/11129/1616/NuriyevaZulfiyye.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 17 March 2018).

- Pedroni, Peter. 1999. Critical values for cointegration tests in heterogeneous panels with multiple regressors. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 61: 653–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroni, Peter. 2004. Panel cointegration: Asymptotic and finite sample properties of pooled time series tests with an application to the PPP hypothesis. Econometirc Theory 20: 597–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, Philip. 1992. Do banks gain or lose from inflation. Journal of Retail Banking 14: 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Pesaran, M. Hashem. 2007. A simple panel unit root test in the presence of cross section dependence. Journal of Applied Econometrics 22: 265–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petria, Nicolae, Bogdan Capraru, and Iulian Ihnatov. 2015. Determinants of banks’ profitability: Evidence from EU 27 banking systems. Procedia Economics and Finance 20: 518–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivard, Richard J., and Christopher R. Thomas. 1997. The effect of interstate banking on large bank holding company profitability and risk. Journal of Economics and Business 49: 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, Angela, and Alina Camelia Sargu. 2015. The impact of bank-specific factors on the commercial banks liquidity: Empirical evidence from CEE countries. Procedia Economics and Finance 20: 571–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahminan, Sahminan. 2004. Balance-Sheet Effects of Exchange Rate Depreciation: Evidence from Individual Commercial Banks in Indonesia. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina. [Google Scholar]

- Sahminan, Sahminan. 2008. Effects of exchange rate depreciation on commercial bank failures in Indonesia. Journal of Financial Stability 3: 175–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sastrosuwito, Suminto, and Yasushi Suzuki. 2011. Post Crisis Indonesian Banking System Profitability: Bank-Specific, Industry-Specific, and Macroeconomic Determinants. Paper presented at the 2nd International Research Symposium in Service Management, Yogyakarta, Indonesia, July 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Seferli, Elmir. 2010. The Effect of Macroeconomic Factors on the Performance of Azerbaijan Banking System. Master’s dissertation, Dokuz Eylul University, İzmir, Turkey, June 29. Available online: http://acikerisim.deu.edu.tr/xmlui/bitstream/handle/12345/10837/261492.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 17 March 2018).

- Short, Brock. 1979. The Relation between Commercial Bank Profit Rates and Banking Concentration in Canada, Western Union, and Japan. Journal of Banking and Finance 3: 209–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SSCAR. 2018. State Statistical Committee of Azerbaijan Republic, System of National Accounts and Balance of Payments. Available online: https://www.stat.gov.az/source/system_nat_accounts/ (accessed on 17 March 2018).

- Sun, Poi Hun, Shamsher Mohamad, and Mohamed Ariff. 2017. Determinants driving bank performance: A comparison of two types of banks in the OIC. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal 42: 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TAXAZ. 2015. Tax System of the Republic of Azerbaijan, Special ed. Baku: Ministry of Taxes. [Google Scholar]

- Trujillo-Ponce, Antonio. 2013. What determines the profitability of banks? Evidence from Spain. Accounting and Finance 53: 561–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US EIA. 2018. United States Energy Information Administration. Available online: https://www.eia.gov/dnav/pet/pet_pri_spt_s1_m.htm (accessed on 17 March 2018).

- Westerlund, Joakim. 2007. Testing for Error Correction in Panel Data. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 69: 709–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 | |

| 4 | |