Abstract

This paper analyzes the evolution of the main theories regarding the capital structure and the related impact on risk and corporate performance. The capital structure is a dynamic process that changes over time, depending on the variables that influence the overall evolution of the economy, a particular sector, or a company. It may also change depending on the company’s forecasts of its expected profitability, capital structure being, in fact, a risk–return compromise. This study contributes to the literature by investigating the drivers of capital structure of the firms from the Romanian market. For the econometric analysis, we applied multivariate fixed-effects regressions, as well as dynamic panel-data estimations (two-step system generalized method of moments, GMM) on a panel comprising the companies listed on the Bucharest Stock Exchange. The analyzed period, 2000–2016, covers a cycle with significant changes in the Romanian economy. Our results showed that leverage is positively correlated with the size of the company and the share price volatility. On the other hand, the debt structure has a different impact on corporate performance, whether this calculated on accounting measures or seen as market share price evolution.

Keywords:

capital structure; leverage; bankruptcy risk; corporate performance; fixed-effects regressions; two-step system GMM; emerging countries JEL Classification:

C23; G32

1. Introduction

Capital structure remains a challenge, even if many theorists have tried to explain the debt ratio variation across companies. Pioneering studies on capital structure based their hypotheses on perfect capital market conditions that lead to rather theoretical assumptions. Campbell and Rogers (2018) discussed about the Corporate Finance Trilemma that occurs since companies would like to decide on their debt, cash holdings, and equity payout policies at the same time, but firms cannot. Nevertheless, Ardalan (2018) proved that there prevails an optimal capital structure for the firm. However, for companies based in the major markets of United Kingdom, Germany, France, and PIIGS (Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece, and Spain) significant discrepancy was established in their capital structures between 2006 and 2016 (Campbell and Rogers 2018). As well, DeAngelo and Roll (2015) noticed for U.S. companies, capital structure stability is the exception, not the rule.

Since the 1950s, the debates on the capital structure have gained noteworthy interest, and the idea has appeared, of finding an optimal ratio between equity and debt that would minimize the capital cost and would maximize the companies’ value (Zeitun and Tian 2007). Durand (1952) was the pioneer of this research, and his assumption could be maintained up to the point where the high debt level would determine the shareholders and the creditors to seek for higher returns, due to the increase of the insolvency risk.

Subsequently, the approach known as the traditional thesis of capital structure relevance has been surpassed when Modigliani and Miller (1958) published their paper regarding the irrelevance of the capital structure decisions on companies’ value. Primarily, the theory was developed under perfect capital market conditions, but the review of the initial hypotheses and the acceptance of market imperfections led to various papers that attempt to explain the importance of the capital structure. Among the research directions could be highlighted the trade-off or the static equilibrium theory (Modigliani and Miller 1963), the irrelevance of capital structure theory (Miller 1976), the information asymmetry and the signal theory (Brealey et al. 1977), the theory of contracts (Jensen 1986; Jensen and Meckling 1976), the pecking order theory (Myers 1984; Myers and Majluf 1984), and market timing theory (Baker and Wurgler 2002).

We consider that many evolvements have been made regarding the ability of financial theory to explain the capital structure decisions, but there are noteworthy particularities that should be considered in the case of emerging countries. For instance, Romania, along with other countries from Eastern Europe, has passed through a long transitional period. As Delcoure (2007) affirmed, for Central and Eastern European (henceforth “CEE”) countries, progress has been made in terms of macroeconomic stabilization, price liberalization, state-owned enterprise privatization, direct subsidy reductions, financial market, commercial banking, and tax system effectiveness. Giannetti (2003) noticed that firms are highly indebted if the domestic stock markets are underdeveloped. According to Jõeveer (2013), about half of the variation in leverage allied to country factors is described by recognized macroeconomic and institutional features, whereas the rest is driven by unmeasurable institutional variances.

Starting from theory of irrelevancy (Modigliani and Miller 1958), we have examined the subsequent approaches that have progressively considered the market imperfections. As well, we have analyzed these concerns correlated with the value of the company, taxation, the threat of financial difficulties, the conflicts between the groups of interests in a company, and the phenomenon of information asymmetry.

Further, we aim to add this paper to the literature on the dynamics of the capital structure decisions, by analyzing the relationship between leverage, profitability, as well as risk, and a set of explanatory variables. For instance, Brendea (2014) examined the influence of profitability, growth opportunities, assets tangibility, company size, Herfindahl Index for ownership concentration, and the type of controlling shareholders on the ratio of total debt to total assets. Sumedrea (2015) explored the impact of return on equity, earnings per share, business growth, assets’ tangibility, tax policy, dividend policy, and company size on the total debt to total assets ratio. Vătavu (2015) investigated the drivers of firm profitability as measured by return on assets and return on equity, namely, capital structure indicators, assets tangibility, the ratio of tax to earnings before interest and tax, the ratio of standard deviation of earnings before interest and tax to total assets, current liquidity ratio, and the annual inflation rate.

First, different to previous papers that examined the listed companies in Romania (Brendea 2014; Sumedrea 2015; Vătavu 2015), the current paper examines the influence of capital structure on multiple variables, such as leverage, profitability, and risk. Secondly, our purpose is to extend the analyzed period in other studies accomplished on the Romanian economy, such as Brendea (2014)—which considered the period 2004–2011, Vătavu (2015)—which covered the period 2003–2010, and Sumedrea (2015)—that focused on the economic crisis and analyzed the period 2008–2011. Therefore, our approach covers an extended time frame, namely 2000–2016. During this period, the Romanian economy has passed through important transformations that have influenced almost every aspect, from political, regulatory, financial, and social components. In this regard, we will present in the third section of the current paper, brief facts regarding the capital market evolution and the banking and credit system development. We consider it important to mention that during this period, it was possible to identify all the stages of an economic cycle, but for an economy adapting to the capital market conditions, this is quite an ongoing process, rather than a strategic path correlated with the business cycle phases. The research question of current paper is formulated as follows:

Which are the main drivers of firm leverage, profitability, and risk for listed companies on the Bucharest Stock Exchange?

The remaining part of this paper is structured as follows. The second section underlines how the research focus regarding capital structure has evolved within literature, the mutual implications of the main research paths, and highlights the results of previous studies. The third section provides a short review on the particularities of developing countries, and outlines the evolution of the Romanian economic environment during the investigated period. The fourth section describes the research sample, along with selected variables, and the research methods. The fifth section reveals the descriptive statistics, correlation analysis, and the outcome of panel data regression estimations. The last section concludes the study.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Gradual Development of the Main Theories Regarding Capital Structure

The work of Modigliani and Miller (1958) (henceforth “MM”) and the previous theoretical contributions—among which should be mentioned Durand (1952); Guthmann and Dougall (1955)—have struggled with various inconsistencies. If the traditional thesis inconveniences stemmed from assuming the certainty of the market structure and interest rates, the MM criticisms are mainly caused by the indebtedness risk. Summarizing, MM’s initial theory stated that the value of a company could not be affected by amending the debt–capital ratio. Despite the rigidity of its assumptions, the model is useful to determine under which conditions the capital structure becomes irrelevant:

- there are no transaction costs on the capital market;

- it is possible to lend and borrow money at the risk-free interest rate;

- there are no bankruptcy costs;

- firms could issue only two types of securities: free interest risk bonds and common shares;

- all the companies are included in the same risk class;

- the cash flows are constant and perpetual;

- all the agents have the same information (there is no possibility of arbitration by sending market signals);

- the managers want to maximize shareholders value (there is no agency costs);

- the cash flows are not affected by the changes in the capital structure.

The absence of costs and arbitration possibility determined by the changes in the capital structure have generated the first hypothesis or Proposition 1, which states that the value of a company fully funded by equity is the same as the one funded both by equity and debt. Following this idea, the authors led to Proposition 2, which says, “the average capital cost of any company is completely independent of the capital structure, and it equals the return rate offered to shareholders by an unlevered firm of the same class” (Modigliani and Miller 1958). The model assumed that a higher level of indebtedness would transfer a higher risk on shareholders that will require a higher opportunity cost. Supporting these two ideas, we can notice that the premium risk is precisely the difference that keeps steady the capital cost. Agreeing also with the three hypotheses, namely lack of arbitrage opportunity, absence of transaction costs on the market debt, and existence of a risk-free interest rate in the market, Miller and Modigliani (1961) yield Proposition 3, sustaining that the dividend policy does not change the value of the company. Despite the restricting conditions, the model has an important predictive value, but ignoring taxation consequences is a concern too significant not to be considered.

Later on, Modigliani and Miller (1963) showed that if taxation is taken into account, debt becomes beneficial for companies because interest deduction reduces the taxes. In the authors’ opinion, raising the leverage implies transferring, to shareholders, the tax deductions, a fact that leads to maximizing the level of indebtedness. The approach proposed by MM was highly debated, and we will further discuss some of the most typical points of view.

Stiglitz (1969) considered that the main critical point of MM’s analysis was to suppose that the bonds issued by firms and individuals have zero default risk. It has been stated that the risk is different depending on the type of the firm, and is influenced by the collateral provided and the market conditions. Likewise, it is pointed out that if debt would not lead to bankruptcy costs, firms would choose to raise as much debt as possible (Stiglitz 1974). Nevertheless, the conclusion of the study is that there are bankruptcy costs, both direct and indirect, and the relationship is directly correlated with indebtedness, and so is the cost of borrowing.

Fama (1978) pointed out that the studies previously published were based on the following premises: perfect capital markets, equal access for the companies to different markets, and common expectations on all the markets. In the end, the author affirmed that the distribution of dividends affects the firm’s financial decisions.

Bradley et al. (1984) argued that the irrelevance of the dividend policy outlined by MM does not imply stable market conditions, but requires the capital market efficiency.

Wald (1999) contended the market imperfections and how the studies that emerged after MM have reached different conclusions other than MM, such as the agency, bankruptcy, and information asymmetry costs.

Briefly, the studies that have researched the limitations of MM’s theory have highlighted that the capital markets are not perfect, and indebtedness lowers the tax burden, but there are also bankruptcy costs that limit the tax benefits. Indebtedness also mitigates the conflicts between managers, creditors, and shareholders, and the lack of available information between different agents on the market. MM themselves, in 1963, have improved the original version where they were underestimated the tax benefits that a company may have from using indebtedness, and this time they were stating that the optimal capital structure is achieved at the maximum level of indebtedness a company can sustain (Modigliani and Miller 1963). This assumption will also draw criticism for the reason that a high level of debt also entails high bankruptcy costs. Despite its limitations, MM’s work is important, as it have paved the way for further contributions to the financial economy, stating the cornerstone on understanding the prominence of the financial decisions on the company’s value.

Afterward, Miller (1976) focused on bankruptcy costs, and noted that beyond the corporate perspective, for the persons involved, the balance between tax benefits and bankruptcy costs is actually very hard to find. At the same time, the author noted that in a balanced market, the shareholders attempts to benefit from tax advantages would generate a progressive increase of the tax rates in order to restore the balance.

Establishing the capital structure involves, in fact, a series of agreements between the interest groups of a firm, each party aiming to maximize its benefit. For managers, this could mean increasing their control, while the shareholders pursue increased value of the company. This creates the so-called agency cost (Ross 1977) that determined seeing the capital structure through the conflicts between shareholders, managers, and creditors. For instance, Abor (2007) argued that agency issues may determine firms to follow very high debt strategy, hence resulting in poorer performance. The conflicts of interest between shareholders and managers arise particularly when the company’s management has the power to use the free cash flow to achieve personal benefits at the expense of the shareholders. On this issue, Stulz (1990); Harris and Raviv (1990); Zwiebel (1996) argued that debt is a way to reduce conflicts, since the repayments of the debt determine managers to be more conservative and more cautious with excessive investments. In another context, Majumdar and Chhibber (1999) argued that the role of debt as a monitoring channel to increase firm performance is not substantial. In addition, Jensen (1986) noted that leverage is a manner to diminish the management monitoring cost. Thus, reducing the free cash flow will limit the management opportunities to make significant expenditures in their own interest. Secondly, the conflicts between shareholders and creditors create the so-called idea of asset substitution that occurs by transferring the welfare from creditors to shareholders, when the last ones decide to contract new debts affecting the initial creditors (dilution of rights). Also, between these stakeholders may arise the underinvestment issue—giving up projects with positive net present value that would benefit the creditors, but would prejudice the shareholders, or the issue of requiring higher interest rates when specialized assets are purchased because of the higher risk assumed by creditors (Myers 2001).

Most of the models regarding capital structure start from the assumption that debt ratio is a static decision. However, in the real economy, firms adjust the debt level depending on the changes of firm value. Goldstein et al. (2001) noted that although creditors are protected by contractual agreements, in fact, the firms have the option to contract new credits without extinguishing the existing debt. In case of bankruptcy, all creditors usually receive the same percentage of indemnity, regardless of when the debt was granted. Obviously, such debt is riskier than the ones described by the traditional patterns of capital structure and most of the bond price models, where the bankruptcy costs are assumed to remain constant over time. Hall et al. (2000) reported for U.K. small and medium sized enterprises, a positive link between long-term debt and asset structure, but a negative relation between company size and age; further short-term debt appeared to be negatively related to profitability, asset structure, size and age, whereas it was positively linked with growth.

With regards to the information asymmetry, we can state that the information represents a set of data that can be observed by different agents who may have a contractual relationship. Information asymmetry means that some of the agents do not have access to the information, generating three possible issues: the moral hazard, the adverse selection, and possibility to use market signalization. Identifying the sectors and the companies that have good performances becomes, therefore, more challenging, for the reason that some agents may make flawed decisions based on the limited information they have. For some authors, the size of the company is therefore a relevant factor. It is considered that large firms have a lower risk of asymmetry, whereas accessing information about these companies is easier, and their visibility in the capital markets is higher.

Frank and Goyal (2009) grouped the theories on capital structure into two categories, correlated with the market imperfections:

- the bankruptcy costs issue: trade-off theory (henceforth “TOT”);

- the agency cost and information asymmetry issue: pecking order theory (henceforth “POT”) and market timing theory (henceforth “MTT”).

The trade-off theory shows the importance of limiting indebtedness because of the directly proportional increase of costs determined by the risk of experiencing financial difficulties that counterbalances the tax benefits. The bankruptcy costs consist of direct costs generated by accounting and legal expenses caused by bankruptcy or reorganization, as well as indirect costs represented by lost opportunities because of poor management, such as suppliers and customers’ loss of confidence. This theory implies an optimal ratio between indebtedness and equity, which maximize the company’s value, being considered as the point where the benefits and costs of indebtedness are in balance (Shyam-Sunder and Myers 1999). However, keeping this balance is seen from different standpoints. Thus, Jensen (1994) considered that the balance remains static, and its adjustment is done immediately and cost-free. In contradiction, the dynamic approach requires an expensive process of permanent rebalancing. For this reason, several authors believe that companies are rather trying to keep leverage within a certain range (Kane et al. 1984). The main factors explaining the trade-off theory are the bankruptcy costs (Cook and Tang 2010; Fama and French 2002), the taxes (Miller and Scholes 1978), the agency costs (Fama and French 2002), and the costs of financial adjustments (Antoniou et al. 2008). Among recent studies supporting this theory we can mention Hovakimian (2006); Faulkender et al. (2012); Kayhan and Titman (2007). Although the trade-off theory treats debt as a factor that could favor the firms, still no explanation has been given with regards to the survival of many high performance firms that do not use indebtedness. In addition, an unanswered question is why, in the countries that have reduced taxes or a tax system that cuts the tax advantage determined advantage debt, the firms still have a high leverage.

The pecking order theory (Myers 1984; Myers and Majluf 1984) is based on the assumption that investors know they could confront an information asymmetry issue, for example, the managers’ attempt to issue risky securities when they are overvalued. At the same time, managers know that shareholders will try to limit this risk, and this could lead to the inability to finance certain profitable investments through the capital market. Briefly, the pecking order theory argues that if external sources are more expensive than the internal ones, and if attracting capital is more expensive than debt, the capital structure will be affected only if the internal funds are unsatisfactory. For Myers and Majluf (1984), the firms that use external funding sources also may face the adverse selection issue that followed the information asymmetry. The adverse selection reflects the market’s failure to individually evaluate each company. The companies are instead ranked according with the sector they belong, and thus companies with cost-effective and high-quality projects can be underestimated, while unsuccessful projects can be overestimated. This model shows that the financial structure of a firm is driven by the needs for financing new investments, and not by the existence of an optimal debt level, choosing debt only when internal resources are scarce. However, the transaction costs support the ranking of financing options in the order presumed by the pecking order theory. Hence, firms will pursue the growth or decrease of indebtedness when the forecasted investments exceed or fall below the internal resources (Fama and French 2002). Kayhan and Titman (2007) stated that the leverage is higher when financial deficit, understood as the difference between financing needs and internal financing sources, is higher. In other words, seen in terms of indebtedness, the leverage is lower when the firms are profitable (Fama and French 2002), and seen in terms of profitability, it is higher when the firms have more investment opportunities (Antoniou et al. 2008). In a more complex analysis, balancing these costs can lead the companies with high investment opportunities to maintain a lower level of leverage in order to preserve a certain financing capacity (Kayhan and Titman 2007), and avoid being in the situation of giving up some valuable investments or issuing risky securities (Fama and French 2005). However, Kayhan and Titman (2007) noted that also those who have no future investment opportunities could maintain a low indebtedness because they tend to capitalize their present results.

The companies that face increased cash flow volatility also tend to be less leveraged, in order to diminish the possibility of having to issue risky securities or losing investment opportunities when their own resources are low, a fact that explains also why dividend distribution is negatively correlated with indebtedness. On the other hand, the cash flow volatility is associated with the restriction of the leverage capacity, which makes Lemmon and Zender (2010) consider that by controlling the cash flow volatility, the pecking order theory could adequately explain the financing decisions.

The pecking order theory now has great acceptance, and many companies are not aiming to find the optimal combination of debt and equity, but rather trying to finance their new projects through internal resources, because of the fear of market aversions or because the available information does not provide certainty (Frank and Goyal 2009). In fact, the authors have analyzed the characteristics of the companies when they choose the form of financing the new investments, taking the two theories as benchmarks, with the objective of validating the arguments of each one.

The market timing theory assumes that there is no optimal capital structure, financial decisions are changing over time (Baker and Wurgler 2002), and the evolution of capital structure must be seen as the result of the historical funding decisions. MTT suggests that companies will decide to issue new shares depending on the market conditions, and this change will have influence in the coming years, because debt adjustment is not itself a goal (Hovakimian 2006). Less indebted companies are generally those who have accumulated funds when they have been overestimated, and implicitly, very indebted firms are those who have attracted external funds when their assessments were detrimental (Baker and Wurgler 2002). At the same time, these circumstances can be noticed when a rise in the price of shares is forecasted, wherein firms will attract capital, or if a decrease is expected, then they will choose indebtedness (Kayhan and Titman 2007). This suggests a negative relationship between the company’s assessment of the capital market and the level of indebtedness (Hovakimian 2006). This way, the decisions managers take depend on the variations of shares price and debt cost, and at the same time, these decisions and the fluctuations of the capital markets have a long-term effect on the financial structure (Baker and Wurgler 2002).

For an enhanced comprehension, Table 1 presents some drivers of indebtedness and their impact as these are indicated by the three capital structure theories.

Table 1.

Drivers of the capital structure and their effect according to the main theories.

Further, Table 2 provides a short review of the literature on capital structure.

Table 2.

Brief review of literature on capital structure.

2.2. The Effects of Macroeconomic Instability on Capital Structure

Bernanke and Gertler (1995) started from the idea that, at least in the short term, the monetary policy has a significant effect on the economy. Thus, the authors noted that if there is a tightening of monetary policy in a period of about four months, there will be a drop in gross domestic product (henceforth “GDP”), and then a price fall within a year. What draws attention is that the monetary policy has a stronger impact on short-term interest rates, and it is expected that the strongest impact would be on short-term asset acquisition, however, the fastest effect of the policy monetary policy is on real estate investments. This finding is odd, as investments in durable goods should be more sensitive to long-term interest rates. The same study shows that long-term investments seem not to be seriously affected by the monetary policy.

Bo and Lensin (2005) grouped the companies in terms of liquidity and leverage, and noted that companies with low liquidity have greater leverage and a higher reported sales/assets ratio. When the under- or over-indebtedness criterion was considered, it was noted that over-indebted firms are up to three times more sensitive to macroeconomic instability. When the macroeconomic conditions are uncertain, companies become more cautious and borrow less.

Baum et al. (2009) noted that while in Germany, a country based on the banking system, profitability is influenced by the maturity of debt, in the case of the United States, this correlation is no longer maintained. The result led the authors to assert that financial environment plays an important role in companies’ capital structure decisions and on their subsequent consequences.

Baum et al. (2017) asserted that the leverage evolution follows a “mean reverting” process, but the speed to adapt at this process depends on company-specific factors (difficulty of financing, firm evaluation on the capital market, company size, profitability, and leverage), on the countries’ macroeconomic conditions, and last but not least, on certain omitted factors which may have a significant impact. In terms of macroeconomic conditions, like Cook and Tang (2010); Drobetz and Wanzenried (2006); de Haas and Peeters (2006); Baum et al. (2017) also noticed the importance of the real GDP growth. Risk is considered an important component that has a different influence on the adjustment speed of the leverage according to its current level, and identifies two main sources of risk, respectively, the macroeconomic factors and the specific characteristics of the firms (Cook and Tang 2010). The impact of the risk on the leverage adjustment speed was explored by Cook and Tang (2010) through classifying the financial status of the companies in financial surplus or deficit, and the current leverage as above or below the target level. Thus, the firms whose leverage level is above the target will adjust, more quickly, their capital structure when macroeconomic risk is high and firm risk is low. This is motivated by companies trying to protect themselves against any financial constraints. On the contrary, firms whose indebtedness level is lower than the target and have good results would not primarily seek to adjust leverage, but rather, to maintain the level. On the other hand, companies facing financial deficits and whose indebtedness level is below the target will try to adjust their capital structure when the macroeconomic and company risks are relatively low. In the above-mentioned study, leverage is calculated using accounting indicators, the motivation being that unlike the market size indicators, the accounting measures are not influenced by the market value of capital that can undergo significant changes, even if the level of indebtedness does not change.

Furthermore, several features of the business cycle dynamics of the capital structure have been explored in the literature. For instance, Jermann and Quadrini (2012) analyzed the cyclicality of equity and debt over the business cycle by means of a model in which financial frictions affect corporate borrowing constraints, and argued that shocks are important for macroeconomic fluctuations. Azariadis et al. (2016) found for the U.S. economy between 1981–2012, that unsecured debt is strongly procyclical, with some tendency to lead GDP, while secured debt is acyclical. According to Drobetz et al. (2015), companies amend more slowly in the course of downturns, whilst the business cycle effect on adjustment speed is most noticeable for financially strained firms in market-based nations. As well, Zeitun et al. (2017) revealed that the speed of adjustment to the optimal capital structure is, on average, slower after the crisis, due to the lack of debt financing supply. Thereby, Seo and Chung (2017) argued the adjusting capital structure is so pricy that firms do not instantly react to capital-structure shocks. Devos et al. (2017) asserted that the speed of adjustment towards the optimal debt ratio of the firm is about 10–13% lower when a firm has covenants, related to companies that do not have covenants. For a sample of 1594 Indian manufacturing firms over 1998–2011, Bandyopadhyay and Barua (2016) laid down that macroeconomic cycle significantly impacts corporate financing decisions and performance.

Likewise, Al-Zoubi et al. (2018) brings important contribution to previous research, showing that companies’ decisions regarding capital structure determine a persistent and cyclical evolution of leverage. Indebtedness cyclicity depends on the business cycle, whereby the duration is calculated between two moments of economic peaks or troughs, and it includes four stages: expansion, peak, contraction, and trough. The study was conducted on the U.S. market, with the database including the period 1975–2016. During this period, the authors have identified six business cycles and five financial crises. The main conclusion was that capital structure is cyclical and persistent. The principal divergence with the three theories—trade-off, pecking order, and market timing—is that the leverage does not follow a mean reverting process, explained by a growing leverage when profitability is high, and leverage contraction when the earnings are reducing, but it follows a cyclical process like the business cycle.

Table 3 shows a brief review of previous papers that examined the adjustment speed of capital structure.

Table 3.

Brief review of literature on capital structure adjustment speed.

2.3. The Mystery of Zero Leveraged Companies

Strebulaev and Yang (2013) noted that in 2000, 14% of the U.S. large listed companies had 0 debt in the capital structure, including both short- and long-term debt. Moreover, between 1962 and 2009, on average 10.2% of companies did not register debt in the capital structure. Furthermore, they noted that nearly one third of the companies with zero debt, pay dividends. They conducted a comparative analysis between each unlevered firm and related firms from the same field, and concluded that the size, age, and industry are not the drivers of zero-debt policy. At the same time, the findings highlighted that these firms have a higher level of liquidity, are more profitable, and pay more taxes and dividends. All these considerations led the authors to support Graham (2000) conclusion, according to which many profitable firms are under-levered. Among the factors that lead to a conservative leverage policy or even to zero leverage phenomenon, was noted the disagreement between the management choice and the shareholders option and the type of company. Other determinants of deleveraging are the high confidence of the management in its own strengths and experience with financial crises (Graham and Narasimhan 2004; Malmendier et al. 2011).

Furthermore, Strebulaev and Yang (2013) have noticed that for a substantial number of firms, cash plays a more important role than debt. Companies zero leverage (henceforth “ZL”) and almost zero leverage (henceforth “AZL”) do not use external financing through equity instead of debt financing, but they use less overall external financing. The same study notes that while interest expense can be defined as a monotonically increasing function in relation to leverage, dividends and buyback expenses decrease monotonically by leverage. Therefore, choosing to pay dividends, ZL and AZL companies signal that they are not facing financial constraints. Otherwise, it would not choose to attract debt and would keep the profit. A remarkable conclusion of the study shows that while the stability of the capital structure is not a frequent occurrence, however, stability is much higher when a low level of leverage is adopted, the persistence of zero or close to leverage firms explaining most of this stability.

Table 4 displays a brief review of previous papers that explored the zero leverage companies.

Table 4.

Brief review of literature on zero leverage companies.

3. Specific Figures for Developing Countries—Grounds for Romania’s Case

Romania, almost regardless of the issues studied, is generally referred to as emerging country (Hall et al. 2014; Procházka and Pelák 2015). This determines the interest in understanding what an emerging country means. In this short quest, we try to present the peculiarities of the emerging states, characteristics that can be both opportunities and risks for the companies that operate in these markets. The emerging country notion is associated with the International Finance Corporation (henceforth “IFC”) and apparently, was used for the first time in 1981 during the approach to create a mutual investment fund for developing countries. The word is rather vague, and includes the countries classified as “underdeveloped”, “less developed”, or “poor”. In fact, Mobius (2015) stated that 80% of the world’s population lives in an “emerging” country, and over the past 20 years, the GDP of these countries has increased by over 500%. The World Bank defined emerging economies by gross national income (henceforth “GNI”) per capita (computed using the “Atlas” method) (World Bank n.d.), but there is currently no list of these states. However, Modern Index Strategy Indexes (henceforth “MSCI”) provided a classification (MSCI 2017).

Khanna and Palepu (2010) started from a surprising approach, that differences must be made between developed and developing countries and individually between each state. Countries such as Brazil, China, and India have had, in the last decades, a higher economic growth than the developed countries. The cheap and educated labor force has attracted many companies in these countries. However, many managers believe that these countries still entail high risk. Among the causes identified are included the uncertainty and predisposition to financial crises, bureaucracy, corruption, the risk of receivables non-collection, the problems in finding qualified personnel and logistic issues in goods distribution, and the difficulty of properly evaluate the investment opportunities. Beim and Calomiris (2001) stated that in emerging countries, governments fail to provide the basic institutional fundamentals, such as availability of public information, currency stability, and banking supervision and regulatory system. The banking system is characterized by low bank assets, the corporate sector loans are also reduced and sensitive to macroeconomic conditions, which causes higher capital costs (Jacque 2001). In addition, Billmeier and Massa (2009) argued that high inflation rates are theoretically associated with small and low-efficiency capital markets.

Beim and Calomiris (2001) noticed that the preference for bank debt financing against the capital market is a form of diminishing the informational asymmetry, despite the fact that banks prefer to grant short-term loans, and often, loans based on collateral.

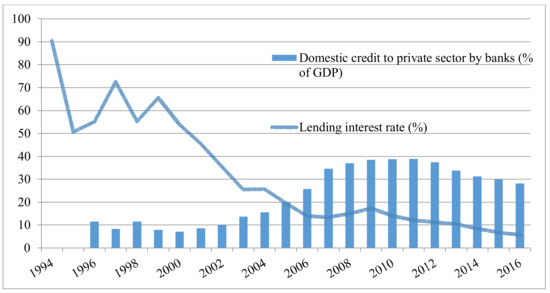

In Figure 1, we point out how Romania identifies with some of previously presented features. At the same time, it is important to mention the progress made in terms of capital market development, the harmonization with the European legislation, especially after 2007 when Romania became a member of the European Union (henceforth “EU”), and the convergence with the international accounting standards.

Figure 1.

Financial resources provided to the private sector and interest rates evolution. Source: Authors’ own processing using World Bank data.

In terms of GDP growth, inflation, interest rates and, last but not least, the credit volume provided to corporate sector, we acknowledge a significant evolution. Besides, the steady decrease of inflation and credit interest rates after 1998 led to an increase in the volume of corporate loans.

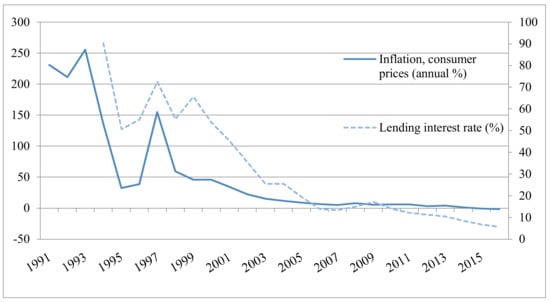

Further, from Figure 2, we admit that the years 1991–1993 meant the collapse of the national currency, a hyperinflationary period that lasted more than a decade.

Figure 2.

Inflation vs lending interest rate. Source: Authors’ own processing using World Bank data.

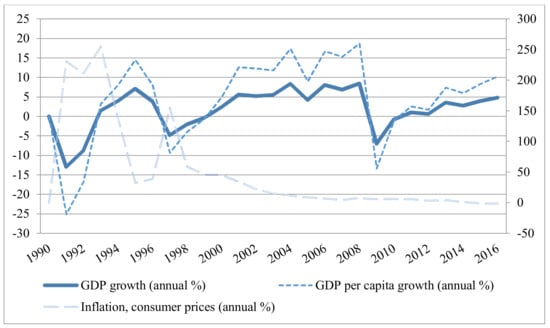

Regarding the evolution of the gross domestic product, we can see from Figure 3 an oscillating evolution. The beginning of the first decade is marked by a fall in GDP, followed by an up and down period, with many difficulties in the 1997–1999 period, that has led many economists to talk about a lost decade. It was only after 2000 that economic growth recovered, following an upward trend until 2008, when GDP reached the highest historic value in real terms by then, namely 139.7 billion euros (204.3 billion USD), although globally, 2008 was a year of crisis.

Figure 3.

GDP and inflation evolution. Source: Authors’ own processing using World Bank data.

From a “technical” point of view, Romania entered the crisis in 2009, a year marked by a sharp shrinkage in GDP (118.3 billion euros, 164.3 billion USD). In the following year, the situation did not improve, and it was not until 2013 that the value obtained in 2008 was exceeded.

With regards to the evolution of the Bucharest Stock Exchange, we have synthesized, in the Appendix, some information for 2000–2016 that plots an overview in terms of volumes and number of participants during this period. These indicators are highlighting the limitations of a small market, but also offer the opportunity to test how the main theories are apply to the Romanian market in a very challenging period. We consider that our results could explore the implications between leverage, risk, and performance on the Romanian market, may be supportive in terms of academic research, and also could have a practical utility for investors.

4. Data and Methods

In this section, we will present the sample and variables employed for this analysis. Also in the second subsection, the econometric models will be described.

4.1. Sample and Variables Presentation

Our database for this analysis includes non-financial companies listed on the Bucharest Stock Exchange (henceforth “(BSE n.d.)”), the analyzed period being 2000–2016. The annual observations were collected through Thomson Reuters Eikon platform. The study included 51 companies, but only 35 of these have been listed throughout the entire period. The last companies included have been listed in 2007—one company, and two companies in 2008. We have considered this option because as can be seen in the Appendix, in this period, important changes have occurred. Thereby, in 2001, 52 companies were delisted from BSE. Many of those companies had low liquidity and reduced traded value, and some of them have not registered any transactions. Nevertheless, this situation shows the relatively low interest for the capital market in the Romanian economic environment. After 2001, the number and value of transactions has constantly increased until the year 2007. In 2008, the capital market from Romania began to experience the international chaos from the stock exchanges that will lean to an important diminution of liquidity.

As regard the variables employed in this analysis, the calculation method is presented in Table 5. For each variable we have checked the outliers and applied winsorizing data procedure, by trimming the observations at the 5th and 95th percentiles, similar to Ahn and Denis (2004); Chen and Chen (2012); Kirch and Terra (2012); Li et al. (2009). This approach has been used in order to remove extreme observations and to limit the results’ unrepresentativeness.

Table 5.

Variables employed in the empirical investigation.

Handoo and Sharma (2014) revealed factors such as profitability, growth, asset tangibility, size, cost of debt, tax rate, and debt serving capacity influence the leverage structure. Based on Hovakimian et al. (2004); Rajan and Zingales (1995), we include company size as the natural logarithm of total assets (Cook and Tang 2010), since large companies may show high target leverage inasmuch as they are disposed to register less volatile cash flows and are less expected to become financially distressed. Asset tangibility was considered because Titman and Wessels (1988); Hovakimian et al. (2004) noticed that companies with a high share of tangible assets that can be collateralized are likely to show relatively small bankruptcy costs and high target debt ratios. As regards growth opportunities, Dang et al. (2012) asserted that low-growth firms do not depend on external financing as much as high-growth firms, and reveal fewer severe asymmetric facts and agency issues. Likewise, Dang et al. (2012) claimed that firms with high profitability benefit from financial flexibility, whereas firms with low profitability have limited internal funds and show financial instability and internal pressure. With respect to depreciation, Öztekin and Flannery (2012) mentioned that firms with more depreciation expenses have less need for the interest deductions. Therewith, DeAngelo and Masulis (1980) argued that non-debt tax shields act as a replacement for the tax advantages of debt, thus, firms with high non-debt tax shields should have less debt. Liquidity was selected since Öztekin and Flannery (2012) noted that firms that have more liquid assets can use them as another internal source of funds instead of debt, leading to lower optimal debt equity ratio.

4.2. The Econometric Models Presentation

The econometric models have been estimated using multivariate regressions, respectively, the ordinary least squares (henceforth “OLS”) method with fixed effects, similar to Kieschnick and Moussawi (2018); Cooper and Lambertides (2018); Buvanendra et al. (2017); Le and Phan (2017); Oino and Ukaegbu (2015); Vithessonthi and Tongurai (2015a, 2015b). The analysis has been performed using the software SPSS Statistics 23 and Stata 13.

where β0 = the constant, xi,t = the vector of explanatory variables, μit = ϕt + εit, ϕt = the unnoticed time specific effect that in a certain period of time affects in the same way all the objects, but that varies in time; εit = the error term, independent and identically distributed, of mean 0 and variance σ2; i = 1, …, 51, t = 2000, …, 2016.

LEVi,t = β0 + β1xi,t + μit

RISKi,t = β0 + β1xi,t + μit

ROAi,t = β0 + β1xi,t + μit

However, Zhang and Liu (2017) noticed that the issue that arises when exploring the drivers of leverage is the potential endogeneity of the explanatory variables, and revealed the reversed causality problem, alongside omitted variables problem. Hence, in order to handle the endogeneity issue, we will employ a dynamic panel data approach (Bandyopadhyay and Barua 2016). Following Öztekin and Flannery (2012); González (2013); Brendea (2014); Dang et al. (2014); Getzmann et al. (2014); Buvanendra et al. (2017); Ghose (2017); Mai et al. (2017); Coldbeck and Ozkan (2018), we will employ the two-step system generalized method of moments (henceforth “GMM”) estimation technique proposed by Arellano and Bond (1991); Arellano and Bover (1995); Blundell and Bond (1998). According to González (2013), GMM models are intended to deal “autoregressive properties in the dependent variable and control for the endogeneity of the explanatory variables and unobserved firm-specific characteristics”. The system GMM estimator employs the levels equation (for instance Equation (1)) to achieve a system of two equations, respectively, the levels e Equation (1) and the first difference of Equation (1) (Brendea 2014), as follows:

where the instruments for Equation (1) are the lagged differences (such as LEVi,t−2 − LEVi,t−3, …, LEVi,1 − LEVi,0) and the instruments for Equation (4) are the lagged levels (such as LEVi,t−2, …, LEVi,0). Like Chen and Guariglia (2013), all the regressors in our equations are considered as endogenous and instrument them using their lagged levels in the differenced equation, and their lagged differences in the levels equation. The validity of the instruments will be checked via the Hansen statistics. A similar approach is employed also for Equations (2) and (3), as below:

LEVi,t − LEVi,t−1 = (αt − αt−1) + (γ + 1)(LEVi,t−1 − LEVi,t−2) + β1(xi,t − xi,t−1) + μit − μit−1

RISKi,t − RISKi,t−1 = (αt − αt−1) + (γ + 1)(RISKi,t−1 − RISKi,t−2) + β1(xi,t − xi,t−1) + μit − μit−1

ROAi,t − ROAi,t−1 = (αt − αt−1) + (γ + 1)(ROAi,t−1 − ROAi,t−2) + β1(xi,t − xi,t−1) + μit − μit−1

We will perform the econometric analysis aiming to investigate several factors selected from earlier studies (Cook and Tang 2010; Dang et al. 2012; DeAngelo and Masulis 1980; Hovakimian et al. 2004; Öztekin and Flannery 2012; Rajan and Zingales 1995; Titman and Wessels 1988) acknowledged as having an impact on leverage, corporate performance, and risk. In this manner, we do not intend to examine a particular hypothesis, but rather explain some relations in an economic setting from Romania, as compared to other studies.

5. Research Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations Analysis

Table 6 summarizes the main descriptive statistics of the variables employed in this research. The average leverage level of this sample is 42% and the median is 37%. Standard deviation for leverage is smaller than the mean, which could suggest a low volatility. Also, in terms of indebtedness, it should be noted that the average long-term debt ratio was only 6%, while the short-term debt registered a maximum rate of 76%. Through the sample, an average 27% of the companies had a debt level below 30%, and the same percentage had a leverage level of over 70%. Hence, selected companies are likely to have a higher risk.

Table 6.

Descriptive statistics.

The share of fixed assets in the asset structure is on average 57%. In terms of return, the mean value is low, for instance, about 3%, and the maximum value is 16%, but the sample also comprises companies that reported losses. The effective average tax rate is 20%. It should be mentioned that until 2004, Romania had a system of proportional taxation of profit, applied with a different basis of calculation, depending on the classification of the economic agents as small or large taxpayers. The overall rate in the 2000–2004 period was 25%, but some categories of taxpayers, such as those earning income from agriculture or earnings acquired from exports benefited from a lower tax rate. Starting with 2005, the flat tax rate of 16% applies. In addition, we see an average of 1.48 QRATIO, CURRATIO 2.13, while the average of variable CASH is 5%.

Table 7 shows the correlation matrix of the selected variables. The correlation matrix reflecting the Pearson correlation coefficients draws to our attention that there are high correlations between some of the variables. This was an important factor in the selection of the variables included in the models, so that variables with a high correlation coefficient would not be simultaneously employed.

Table 7.

Correlation matrix.

5.2. Empirical Output

Table 8 shows the empirical results related to the first econometric model. The outcome acquired in the case of Romania concerning the company size is consistent with the trade-off theory and other previous studies that showed a positive correlation between firm size and leverage (Brendea 2014; Frank and Goyal 2009; Sumedrea 2015), but only in the case of fixed-effects estimations. This state could be explained by the lower risk of bankruptcy and the decrease of information asymmetry (Rajan and Zingales 1995), the lower cash flow volatility (Ghosh 2007), or the increasing possibility to negotiate the credit agreements (Frank and Goyal 2009). According to trade-off dynamic theory, there is a negative correlation between leverage and profitability (Strebulaev 2007). The same connection has been achieved by Booth et al. (2001) which showed that in emerging economies, there is a negative relationship between indebtedness and profitability, but in our sample, this link is not statistically significant, contrary to Handoo and Sharma (2014). On the other hand, the share price volatility (RISK) determines a positive link with the indebtedness level, which can be primarily seen as a tendency of leverage to adjust to the change of market value. At the same time, this indicator could also be powerful for the signal theory point of view, but we consider that on the Romanian market, this hypothesis should be cautiously considered, because of the reduced liquidity of the capital market. Moreover, even if system GMM outcomes reveal a poor relation between leverage and taxation, most of the estimations provide support for a lack of connection between leverage and the effective tax rate, contrary to Devereux et al. (2018); Oino and Ukaegbu (2015); Öztekin and Flannery (2012). This situation could be explained by the low profitability rate in the case of listed companies in Romania, but could be also the consequence of inefficient fiscal management. Besides, cash ratio is negatively related to leverage, only in case of fixed effects approach, in line with Öztekin and Flannery (2012) and Vătavu (2015).

Table 8.

Econometric results—dependent variable LEV.

Further, Table 9 points out the econometric outcomes of the second empirical model. As regards ROA, it should be noted that a negative association has been acquired both with short-term and long-term debt ratio (only in case of fixed-effects estimations), as well as with the dummy variable that assesses the companies that could face financial constraints (only in case of fixed-effects estimations), alike Abor (2007); Le and Phan (2017); Majumdar and Chhibber (1999); Zeitun and Tian (2007). Hence, the results support the pecking order theory, as in previous studies on Romania (Brendea 2014; Sumedrea 2015; Vătavu 2015), and agree with the view of Fama and French (2002), which assumed that perceived in terms of indebtedness, the leverage is lower for profitable companies. Also, Strebulaev and Yang (2013) argued that profitable companies are under-levered. Moreover, the outcome has to be documented with the fact that there is a mixed association between performance and liquidity ratios, consistent with Vătavu (2015). Further, in case of fixed-effects estimations, the coefficient of depreciation is positive, contrary to DeAngelo and Masulis (1980).

Table 9.

Econometric results—dependent variable ROA.

Table 10 highlights the results of the third econometric model. Regarding the share price volatility, we acknowledge that company size is an important factor that negatively influences risk, similar to Bessler et al. (2013); Brendea (2014); Dang (2013). However, similar to Brendea (2014); Dang et al. (2014); Ghose (2017), profitability is negatively related with risk (only in case of fixed-effects estimations), consistent with the reason of pecking order theory that firms with higher profitability use lower levels of debt. Therewith, more profitable firms employ a smaller amount of debt for the purpose that they can use their existing internal financing resources (Myers and Majluf 1984). Jõeveer (2013) asserted that firms from transition countries face large issues of asymmetric information and are less likely to turn to outside sources of finance, even if the investment opportunities exceed the internal funds. Besides, volatility is positively correlated with leverage, as well as with variables that quantify the debt structure, namely the short-term and the long-term debt ratio, but the associations are not confirmed in case of system GMM estimations.

Table 10.

Econometric results—dependent variable RISK.

6. Concluding Remarks

The current study discussed, in the first instance, the development of the fundamental theories regarding the capital structure, the commonalities, and differences between the approaches. Therewith, we also considered specific facets of the emerging countries and the macroeconomic factors that influence the progress of the companies. Thereby, we have outlined the Romanian economic context during the period 2000–2016, and we have analyzed the evolution of GDP, inflation, interest rates, and corporate credit loans. As well, we have pointed out some side considerations concerning the development of the Romanian capital market after 2000. Besides, different to previous papers on Romania which explored exclusively the drivers of capital structure (Brendea 2014; Sumedrea 2015) or firm profitability (Vătavu 2015), the current paper investigated the drivers of firm leverage, profitability, and risk related to the companies listed on the Bucharest Stock Exchange. Therewith, an extended period was considered, namely 2000–2016. By estimating panel data fixed-effects regressions, alongside system generalized method of moments framework, the empirical outcomes provide support for the trade-off theory since a positive link occurred between firm size and leverage, as in previous studies on Romania (Brendea 2014; Sumedrea 2015). As well, the pecking order theory was supported inasmuch as firm profitability appeared to be negatively related with short-term and long-term debt ratio, along with the dummy variable developed according to the leverage level, like in prior research on transition countries (Abor 2007; Le and Phan 2017; Majumdar and Chhibber 1999; Zeitun and Tian 2007).

The limitations of current study arise from the fact that macroeconomic measures were not considered within the econometric estimations. Therefore, as a future research avenue, our aim is to cover variables such as gross domestic product growth rate or inflation rate, and examine their influence on firms’ capital structure decisions.

Author Contributions

These authors contributed equally to this work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Evolution of the Bucharest Stock Exchange, within 2000–2016.

Table A1.

Evolution of the Bucharest Stock Exchange, within 2000–2016.

| Year | Trading Sessions | Trades | Volume | Value | Average Daily Turnover | Market Capitalization | Companies with Listed Shares | Number of Intermediaries |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 251 | 496,887 | 1,806,587,265 | 93,244,168 | 371,491 | 450,512,639 | 114 | 120 |

| 2001 | 247 | 357,577 | 2,277,454,017 | 148,544,839 | 601,396 | 1,361,079,746 | 65 | 110 |

| 2002 | 247 | 689,184 | 4,085,123,289 | 222,426,577 | 900,512 | 2,646,438,376 | 65 | 75 |

| 2003 | 241 | 440,084 | 4,106,381,895 | 268,641,352 | 1,114,694 | 2,991,017,082 | 62 | 73 |

| 2004 | 253 | 644,839 | 13,007,587,776 | 598,072,158 | 2,363,922 | 8,818,832,158 | 60 | 67 |

| 2005 | 247 | 1,159,060 | 16,934,865,957 | 2,152,052,960 | 8,712,765 | 15,311,354,558 | 64 | 70 |

| 2006 | 248 | 1,444,398 | 13,677,505,261 | 2,801,708,288 | 11,297,211 | 21,414,911,687 | 58 | 73 |

| 2007 | 250 | 1,544,891 | 14,234,962,355 | 4,152,436,338 | 16,609,745 | 24,600,746,687 | 59 | 73 |

| 2008 | 250 | 1,341,297 | 12,847,992,164 | 1,895,443,665 | 7,581,775 | 11,629,766,297 | 68 | 76 |

| 2009 | 250 | 1,314,526 | 14,431,359,301 | 1,203,801,128 | 4,815,205 | 19,052,654,442 | 69 | 71 |

| 2010 | 255 | 889,486 | 13,339,282,639 | 1,338,291,678 | 5,248,203 | 23,892,208,164 | 74 | 65 |

| 2011 | 255 | 900,114 | 16,623,747,907 | 2,349,040,633 | 9,211,924 | 16,385,906,510 | 79 | 61 |

| 2012 | 250 | 647,974 | 12,533,192,975 | 1,674,196,588 | 6,696,786 | 22,063,368,089 | 79 | 54 |

| 2013 | 251 | 636,405 | 13,087,904,925 | 2,543,568,507 | 10,133,739 | 29,980,444,693 | 83 | 43 |

| 2014 | 250 | 787,753 | 11,615,242,311 | 2,930,761,698 | 11,723,047 | 28,986,515,068 | 83 | 40 |

| 2015 | 251 | 685,248 | 6,696,750,556 | 1,981,066,772 | 7,892,696 | 32,240,802,464 | 84 | 38 |

| 2016 | 254 | 653,27 | 11,048,103,360 | 2,060,742,861 | 8,113,161 | 32,271,860,627 | 86 | 38 |

Source: Authors’ own processing using data from the Bucharest Stock Exchange http://www.bvb.ro/TradingAndStatistics/Statistics/GeneralStatistics.

References

- Abor, Joshua. 2007. Debt policy and performance of SMEs: Evidence from Ghanaian and South African firms. The Journal of Risk Finance 8: 364–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, Seoungpil, and David J. Denis. 2004. Internal capital markets and investment policy: Evidence from corporate spinoffs. Journal of Financial Economics 71: 489–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zoubi, Haitham A., Jennifer A. O’Sullivan, and Abdulaziz M. Alwathnani. 2018. Business cycles, financial cycles and capital structure. Annals of Finance 14: 105–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, Antonios, Yilmaz Guney, and Krishna Paudyal. 2008. The determinants of capital structure: Capital market-oriented versus bank-oriented institutions. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 43: 59–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardalan, Kavous. 2018. Capital structure theory: Reconsidered. Research in International Business and Finance 39: 696–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, Manuel, and Stephen Bond. 1991. Some Tests of Specification for Panel Data—Monte-Carlo Evidence and an Application to Employment Equations. Review of Economic Studies 58: 277–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, Manuel, and Olympia Bover. 1995. Another Look at the Instrumental Variable Estimation of Error-Components Models. Journal of Econometrics 68: 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azariadis, Costas, Leo Kaas, and Yi Wen. 2016. Self-Fulfilling Credit Cycles. Review of Economic Studies 83: 1364–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Malcolm, and Jeffrey Wurgler. 2002. Market timing and capital structure. Journal of Finance 57: 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, Arindam, and Nandita Malini Barua. 2016. Factors determining capital structure and corporate performance in India: Studying the business cycle effects. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance 61: 160–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, Christopher F., Andreas Stephan, and Oleksandr Talavera. 2009. The Effects of Uncertainty on the Leverage of Nonfinancial Firms. Economic Inquiry 47: 216–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, Christopher F., Mustafa Caglayan, and Abdul Rashid. 2017. Capital structure adjustments: Do macroeconomic and business risks matter? Empirical Economics 53: 1463–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beim, David, and Charles Calomiris. 2001. Emerging Financial Markets. New York: McGraw-Hill/Irwin. [Google Scholar]

- Bernanke, Ben S., and Mark Gertler. 1995. Inside the Black-Box—The Credit Channel of Monetary-Policy Transmission. Journal of Economic Perspectives 9: 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessler, Wolfgang, Wolfgang Drobetz, Rebekka Haller, and Iwan Meier. 2013. The international zero-leverage phenomenon. Journal of Corporate Finance 23: 196–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billmeier, Andreas, and Isabella Massa. 2009. What drives stock market development in emerging markets-institutions, remittances, or natural resources? Emerging Markets Review 10: 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, Richard, and Stephen Bond. 1998. Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics 87: 115–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, Hong, and Robert Lensin. 2005. Is the investment-uncertainty relationship nonlinear? An empirical analysis for the Netherlands. Economica 72: 307–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, Laurence, Varouj Aivazian, Asli Demirguc-Kunt, and Vojislav Maksimovic. 2001. Capital structures in developing countries. Journal of Finance 56: 87–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, Michael, Gregg A. Jarrell, and E. Kim. 1984. On the Existence of an Optimal Capital Structure—Theory and Evidence. Journal of Finance 39: 857–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brealey, Richard, Hayne E. Leland, and David H. Pyle. 1977. Informational Asymmetries, Financial Structure, and Financial Intermediation. The Journal of Finance 32: 371–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brendea, Gabriela. 2014. Financing Behavior of Romanian Listed Firms in Adjusting to the Target Capital Structure. Finance a Uver-Czech Journal of Economics and Finance 64: 312–29. [Google Scholar]

- Bucharest Stock Exchage. General Statistics. n.d. Available online: http://www.bvb.ro/TradingAndStatistics/Statistics/GeneralStatistics (accessed on 17 September 2017).

- Buvanendra, Shantharuby, P. Sridharan, and S. Thiyagarajan. 2017. Firm characteristics, corporate governance and capital structure adjustments: A comparative study of listed firms in Sri Lanka and India. Iimb Management Review 29: 245–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Gareth, and Meeghan Rogers. 2018. Capital structure volatility in Europe. International Review of Financial Analysis 55: 128–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Sheng-Syan, and I-Ju Chen. 2012. Corporate governance and capital allocations of diversified firms. Journal of Banking & Finance 36: 395–409. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Minjia, and Alessandra Guariglia. 2013. Internal financial constraints and firm productivity in China: Do liquidity and export behavior make a difference? Journal of Comparative Economics 41: 1123–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coldbeck, Beata, and Aydin Ozkan. 2018. Comparison of adjustment speeds in target research and development and capital investment: What did the financial crisis of 2007 change? Journal of Business Research 84: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, Douglas O., and Tian Tang. 2010. Macroeconomic conditions and capital structure adjustment speed. Journal of Corporate Finance 16: 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, Ian A., and Neophytos Lambertides. 2018. Large dividend increases and leverage. Journal of Corporate Finance 48: 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, Viet Anh. 2013. An empirical analysis of zero-leverage firms: New evidence from the UK. International Review of Financial Analysis 30: 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, Viet Anh, Minjoo Kim, and Yongcheol Shin. 2012. Asymmetric capital structure adjustments: New evidence from dynamic panel threshold models. Journal of Empirical Finance 19: 465–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, Viet Anh, Minjoo Kim, and Yongcheol Shin. 2014. Asymmetric adjustment toward optimal capital structure: Evidence from a crisis. International Review of Financial Analysis 33: 226–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Haas, Ralph, and Marga Peeters. 2006. The dynamic adjustment towards target capital structures of firms in transition economies. Economics of Transition 14: 133–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeAngelo, Harry, and Ronald W. Masulis. 1980. Optimal Capital Structure under Corporate and Personal Taxation. Journal of Financial Economics 8: 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeAngelo, Harry, and Richard Roll. 2015. How Stable Are Corporate Capital Structures? Journal of Finance 70: 373–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delcoure, Natalya. 2007. The determinants of capital structure in transitional economies. International Review of Economics & Finance 16: 400–15. [Google Scholar]

- Devereux, Michael P., Giorgia Maffini, and Jing Xing. 2018. Corporate tax incentives and capital structure: New evidence from UK firm-level tax returns. Journal of Banking & Finance 88: 250–66. [Google Scholar]

- Devos, Erik, Shofiqur Rahman, and Desmond Tsang. 2017. Debt covenants and the speed of capital structure adjustment. Journal of Corporate Finance 45: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drobetz, Wolfgang, and Gabrielle Wanzenried. 2006. What determines the speed of adjustment to the target capital structure? Applied Financial Economics 16: 941–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drobetz, Wolfgang, Dirk C. Schilling, and Henning Schröder. 2015. Heterogeneity in the Speed of Capital Structure Adjustment across Countries and over the Business Cycle. European Financial Management 21: 936–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, David. 1952. Costs of Debt and Equity Funds for Business: Trends and Problems of Measurement. Cambridge: NBER. [Google Scholar]

- Fama, Eugene F. 1978. Effects of a Firms Investment and Financing Decisions on Welfare of Its Security Holders. American Economic Review 68: 272–84. [Google Scholar]

- Fama, Eugene F., and Kenneth R. French. 2002. Testing trade-off and pecking order predictions about dividends and debt. Review of Financial Studies 15: 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, Eugene F., and Kenneth R. French. 2005. Financing decisions: Who issues stock? Journal of Financial Economics 76: 549–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulkender, Michael, Mark J. Flannery, Kristine Watson Hankins, and Jason M. Smith. 2012. Cash flows and leverage adjustments. Journal of Financial Economics 103: 632–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, Murray Z., and Vidhan K. Goyal. 2009. Capital Structure Decisions: Which Factors Are Reliably Important? Financial Management 38: 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getzmann, André, Sebastian Lang, and Klaus Spremann. 2014. Target Capital Structure and Adjustment Speed in Asia. Asia-Pacific Journal of Financial Studies 43: 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghose, Biswajit. 2017. Impact of Business Group Affiliation on Capital Structure Adjustment Speed: Evidence from Indian Manufacturing Sector. Emerging Economy Studies 3: 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghose, Biswajit, and Kailash Chandra Kabra. 2016. What determines firms’ zero-leverage policy in India? Managerial Finance 42: 1138–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, Saibal. 2007. Bank debt use and firm size: Indian evidence. Small Business Economics 29: 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannetti, Mariassunta. 2003. Do better institutions mitigate agency problems? Evidence from corporate finance choices. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 38: 185–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, Robert, Nengjiu Ju, and Hayne Leland. 2001. An EBIT-based model of dynamic capital structure. Journal of Business 74: 483–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, Víctor M. 2013. Leverage and corporate performance: International evidence. International Review of Economics & Finance 25: 169–84. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, John R. 2000. How big are the tax benefits of debt? Journal of Finance 55: 1901–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, John, and Krishnamoorthy Narasimhan. 2004. Corporate Survival and Managerial Experiences during the Great Depression. Cambridge: NBER. [Google Scholar]

- Guthmann, Harry G., and Herbert E. Dougall. 1955. Corporate Financial Policy. New York: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Graham, Patrick Hutchinson, and Nicos Michaelas. 2000. Industry Effects on the Determinants of Unquoted SMEs’ Capital Structure. International Journal of the Economics of Business 7: 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, Thomas, Cesario Mateus, and Irina Bezhentseva Mateus. 2014. What determines cash holdings at privately held and publicly traded firms? Evidence from 20 emerging markets. International Review of Financial Analysis 33: 104–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handoo, Anshu, and Kapil Sharma. 2014. A study on determinants of capital structure in India. Iimb Management Review 26: 170–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, Milton, and Artur Raviv. 1990. Capital Structure and the Informational Role of Debt. Journal of Finance 45: 321–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovakimian, Armen. 2006. Are observed capital structures determined by equity market timing? Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 41: 221–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovakimian, Armen, Gayane Hovakimian, and Hassan Tehranian. 2004. Determinants of target capital structure: The case of dual debt and equity issues. Journal of Financial Economics 71: 517–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Zhen, Wanli Li, and Weiwei Gao. 2017. Why do firms choose zero-leverage policy? Evidence from China. Applied Economics 49: 2736–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacque, Laurent L. 2001. Inancial Innovations and the Dynamics of Emerging Capital Markets. Boston: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Jaisinghani, Dinesh, and Kakali Kanjilal. 2017. Non-linear dynamics of size, capital structure and profitability: Empirical evidence from Indian manufacturing sector. Asia Pacific Management Review 22: 159–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, Michael C. 1986. Agency Costs of Free Cash Flow, Corporate-Finance, and Takeovers. American Economic Review 76: 323–29. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, Michael C. 1994. Self Interest, Altruism, Incentives, and Agency Theory. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 7: 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, Michael C., and William H. Meckling. 1976. Theory of Firm—Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure. Journal of Financial Economics 3: 305–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jermann, Urban, and Vincenzo Quadrini. 2012. Macroeconomic Effects of Financial Shocks. American Economic Review 102: 238–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jõeveer, Karin. 2013. Firm, country and macroeconomic determinants of capital structure: Evidence from transition economies. Journal of Comparative Economics 41: 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, Alex, Alan J. Marcus, and Robert L. McDonald. 1984. How Big Is the Tax-Advantage to Debt. Journal of Finance 39: 841–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayhan, Ayla, and Sheridan Titman. 2007. Firms’ histories and their capital structures. Journal of Financial Economics 83: 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, Tarun, and Krishna G. Palepu. 2010. Winning in Emerging Markets: A Road Map for Strategy and Execution. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kieschnick, Robert, and Rabih Moussawi. 2018. Firm age, corporate governance, and capital structure choices. Journal of Corporate Finance 48: 597–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Hyun Jung, Pando Sohn, and Ji-Yong Seo. 2015. The capital structure adjustment through debt financing based on various macroeconomic conditions in Korean market. Investigacion Economica 74: 155–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirch, Guilherme, and Paulo Renato Soares Terra. 2012. Determinants of corporate debt maturity in South America: Do institutional quality and financial development matter? Journal of Corporate Finance 18: 980–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, Thi Phuong Vy, and Thi Bich Nguyet Phan. 2017. Capital structure and firm performance: Empirical evidence from a small transition country. Research in International Business and Finance 42: 710–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmon, Michael L., and Jaime F. Zender. 2010. Debt Capacity and Tests of Capital Structure Theories. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 45: 1161–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Kai, Heng Yue, and Longkai Zhao. 2009. Ownership, institutions, and capital structure: Evidence from China. Journal of Comparative Economics 37: 471–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, Yong, Lei Meng, and Zhiqiang Ye. 2017. Regional variation in the capital structure adjustment speed of listed firms: Evidence from China. Economic Modelling 64: 288–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, Sumit K., and Pradeep Chhibber. 1999. Capital structure and performance: Evidence from a transition economy on an aspect of corporate governance. Public Choice 98: 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmendier, Ulrike, Geoffrey Tate, and Jon Yan. 2011. Overconfidence and Early-Life Experiences: The Effect of Managerial Traits on Corporate Financial Policies. Journal of Finance 66: 1687–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Merton H. 1976. Debt and Taxes. The Journal of Finance 32: 261–75. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Merton H., and Franco Modigliani. 1961. Dividend policy, growth, and the valuation of shares. The Journal of Business 34: 411–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Merton H., and Myron S. Scholes. 1978. Dividends and Taxes. Journal of Financial Economics 6: 333–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobius, Mark. 2015. Emerging Markets: 30 Years of Growth. Available online: https://www.franklintempleton.ch/downloadsServlet?docid=i677yro7 (accessed on 17 September 2017).

- Modigliani, Franco, and Merton H. Miller. 1958. The Cost of Capital, Corporation Finance and the Theory of Investment. The American Economic Review 48: 261–97. [Google Scholar]

- Modigliani, Franco, and Merton H. Miller. 1963. Corporate Income Taxes and the Cost of Capital: A Correction. The American Economic Review 53: 433–43. [Google Scholar]

- MSCI. 2017. Global Indexes. Delivering the Modern Index Strategy. Available online: https://www.msci.com/indexes (accessed on 17 September 2017).

- Myers, Stewart C. 1984. The Capital Structure Puzzle. Journal of Finance 39: 575–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, Stewart C. 2001. Capital structure. Journal of Economic Perspectives 15: 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, Stewart C., and Nicholas S. Majluf. 1984. Corporate Financing and Investment Decisions When Firms Have Information That Investors Do Not Have. Journal of Financial Economics 13: 187–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oino, Isaiah, and Ben Ukaegbu. 2015. The impact of profitability on capital structure and speed of adjustment: An empirical examination of selected firms in Nigerian Stock Exchange. Research in International Business and Finance 35: 111–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztekin, Özde, and Mark J. Flannery. 2012. Institutional determinants of capital structure adjustment speeds. Journal of Financial Economics 103: 88–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procházka, David, and Jiří Pelák. 2015. The Development of Capital Markets of New EU Countries in the IFRS Era. Procedia Economics and Finance 25: 116–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, Raghuram G., and Luigi Zingales. 1995. What Do We Know About Capital Structure—Some Evidence from International Data. Journal of Finance 50: 1421–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, Stephen A. 1977. The Determination of Financial Structure: The Incentive-Signalling Approach. The Bell Journal of Economics 8: 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, Sung Won, and Hae Jin Chung. 2017. Capital structure and corporate reaction to negative stock return shocks. International Review of Economics & Finance 49: 292–312. [Google Scholar]

- Shyam-Sunder, Lakshmi, and Stewart C. Myers. 1999. Testing Static Trade-off against Pecking Order Models of Capital Structure. Journal of Financial Economics 51: 219–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. 1969. A re-examination of the Modigliani-Miller theorem. The American Economic Review 59: 784–93. [Google Scholar]

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. 1974. On the Irrelevance of Corporate Financial Policy. The American Economic Review 64: 851–66. [Google Scholar]

- Strebulaev, Ilya A. 2007. Do tests of capital structure theory mean what they say? Journal of Finance 62: 1747–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strebulaev, Ilya A., and Baozhong Yang. 2013. The mystery of zero-leverage firms. Journal of Financial Economics 109: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stulz, RenéM. 1990. Managerial Discretion and Optimal Financing Policies. Journal of Financial Economics 26: 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]