Abstract

This paper analyses the issue of the dynamics of the TARGET2 system balances during the sovereign debt crisis, when some countries registered a decisive inflow of the central bank liquidity and others showed an outflow. The dynamics in the TARGET2 are here explained as being due to a fall in the level of confidence in the capacity of the Economic and Monetary Union to survive, rather than to disparities in the level of competitiveness among countries of the Eurozone. This crisis of confidence has to be considered as the consequence of the implicit refusal of the European institutions to create a mechanism working as lender of last resort for the euro area member States; indeed, only when the ECB took this responsibility by launching the Outright Monetary Transactions clear signs of improvement were observed in the sovereign debt crisis.

JEL Classification:

E42; E52; E58; E62; F32; F34; F36

1. Introduction

This paper analyses the evolution of TARGET2 1 balances during the sovereign debt crisis in the Euro area. Our investigation stresses that the TARGET2 dynamics can be considered a direct consequence of specific political choices made by European institutions, rather than linked to competitiveness disparities across Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) member States. More specifically, they appear to be related to a certain reluctance of European institutions in setting up a “lender of last resort” mechanism in order to provide those member States in need with financial support. TARGET2 system is the infrastructure that allows the settling of payments related to financial institution transactions and to the monetary policy operations within the EMU. This system, essentially, allows for the central bank liquidity to circulate among national central banks of the Euro area, and registers the inflow and outflow of the central bank liquidity for each of these countries. 2

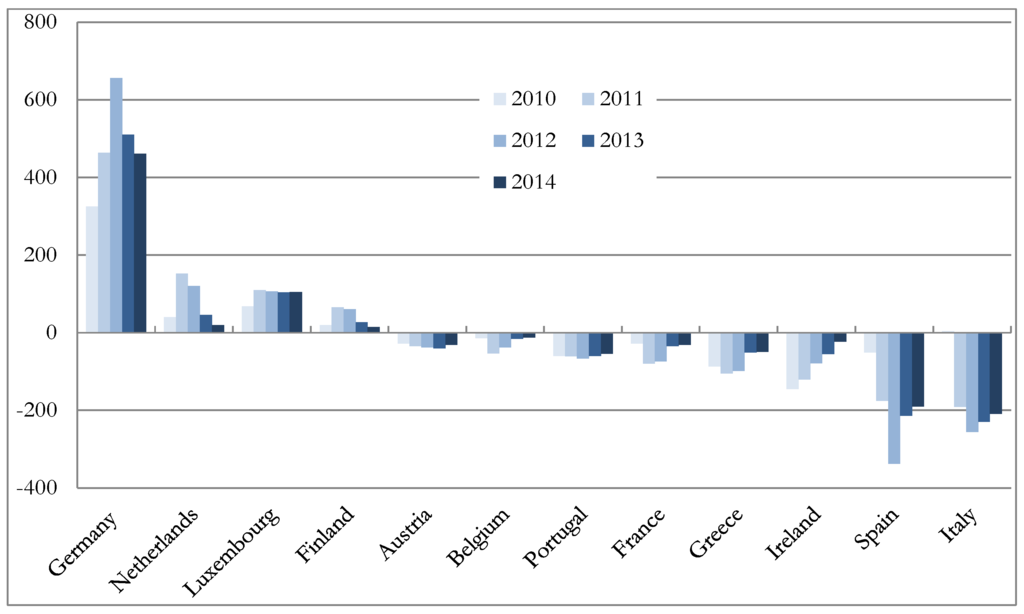

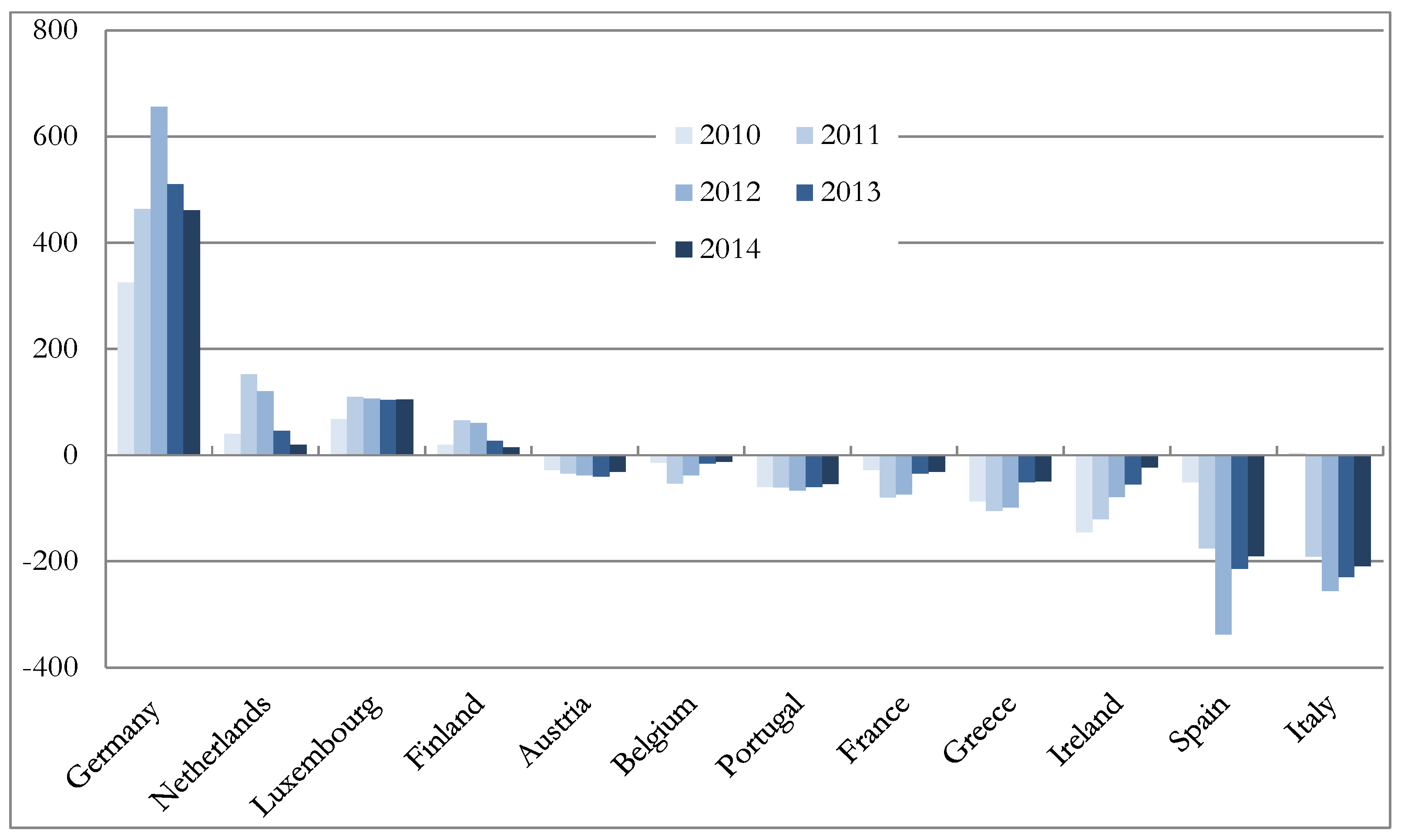

TARGET2 balances values were negligible until August 2007, when some member States started observing substantial central bank liquidity inflow while some others experienced decisive outflow. In this paper, countries showing cumulated claims in the TARGET2 balances at the end of 2012 will be identified as core countries, within which a prominent position is occupied by Germany for the absolute size of its balance; while countries showing cumulated liabilities will be identified as peripheral countries, among which there are Greece, Ireland, Portugal and Spain, countries under financial support programmes promoted by European institutions, and Italy (Figure 1). 3

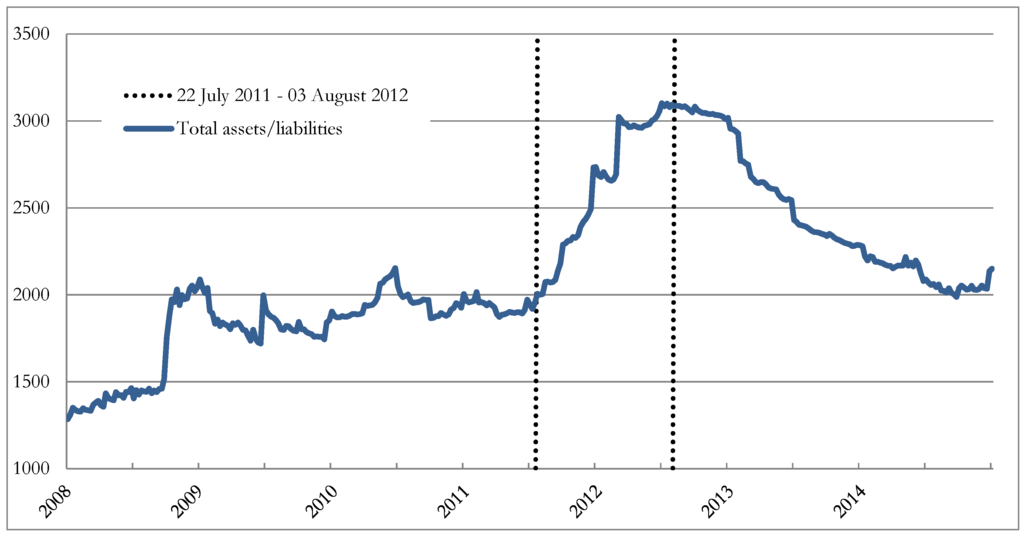

Figure 1.

TARGET2 balances towards the Eurosystem, EMU-12 member States (Euro billion, yearly, end of the period). Source: Elaboration on the “Institute of Empirical Economic Research—Osnabrück University” dataset (accessed on 25 June 2015, http://www.eurocrisismonitor.com/).

Figure 1.

TARGET2 balances towards the Eurosystem, EMU-12 member States (Euro billion, yearly, end of the period). Source: Elaboration on the “Institute of Empirical Economic Research—Osnabrück University” dataset (accessed on 25 June 2015, http://www.eurocrisismonitor.com/).

The determinants of the TARGET2 balances were extensively explored in the literature, and two main positions emerged.

The first, to which we refer as the core interpretation argued that the TARGET2 balances reflected the disparities in the level of competitiveness across the EMU member States (Sinn and Wollmershäuser [3,4,5], see also Cesaratto [6]). More specifically, while in the core countries, a sustainable fiscal policy was coupled with structural reforms aimed at increasing the degree of competitiveness both in the labour and in the goods markets, the peripheral countries limited their action to support domestic demand: the private component through a reckless credit policy and the public component through an unsustainable fiscal policy. As a result, a gap in levels of competitiveness between the two groups of countries has been growing, with the core countries accumulating surpluses in the current account of the Balance of Payments (BoP) and the peripheral countries accumulating deficits. Until 2007, capital flows from the core countries financed the BoP deficits in the peripheral countries; with the incoming of the crisis, an increase in the country risk due to a re-evaluation of the economic fundamentals in the peripheral countries negatively affected the access to financial markets both for their governments and financial institutions, causing a capital flow reversal toward the core countries. The non-standard measures of monetary policy implemented by the European Central Bank (ECB) delayed the essential prices adjustment, in particular that of the wage rate and of the interest rate, and continued to feed the deficit of the public sector budget and of the BoP current account. Ultimately, TARGET2 imbalances reflected the outflow from the peripheral countries of those financial resources provided to the bank sector through the non-standard monetary policy measures. 4 As far as the economic policy recommendations are concerned, the “core interpretation” suggests two main routes: austerity policies and structural reforms. The first one consists of a restrictive fiscal and monetary policy: the resulting economic slowdown would have promoted an increase in the level of competitiveness of peripheral countries by determining a wage rate contraction, while the rise in the interest rate connected with the restrictive monetary policy would have supported the access to financial markets by encouraging the inflow of financial capital from abroad. The second one consists of an industrial policy aimed to raise the degree of competitiveness in service and good markets and the degree of flexibility in the labour market; therefore, also in the long run, the level of competitiveness of peripheral countries would have been strengthened through the adoption of the structural reforms.

The second position, which we called the peripheral interpretation, argued that the TARGET2 balances reflected the high strains in the financial markets, mainly attributable to a lower confidence in the ability of the European institutions to face the sovereign debt crisis (Panico and Purificato [7], ECB [8,9,10], De Grauwe and Ji [11], Deutsche Bundesbank [12], Lavoie [13]). What has been observed was a sort of overshooting in sovereign bonds’ yields of the peripheral countries: regardless of the economic fundamentals and the alleged divergence in the level of competitiveness between EMU member States, financial markets incorporated in the price system and, in particular, in sovereign bonds’ yields, the expectation of a return for the peripheral countries to the respective national currencies with a corresponding devaluation. The fear that the euro and EMU could be just one step away from the collapse was real, since Mario Draghi, the President of the ECB, on 26 July 2012 considered it worth declaring: “When people talk about the fragility of the euro and the increasing fragility of the euro, and perhaps the crisis of the euro, very often non-euro area member states or leaders, underestimate the amount of political capital that is being invested in the euro. And so we view this, and I do not think we are unbiased observers, we think the euro is irreversible” (ECB [14]). Confirming this position a couple of weeks later, the ECB [15] (p. 5) stressed: “Exceptionally high risk premia are observed in government bond prices in several countries and financial fragmentation hinders the effective working of monetary policy. Risk premia that are related to fears of the reversibility of the euro are unacceptable, and they need to be addressed in a fundamental manner. The euro is irreversible”. At the beginning, the crisis arose in sovereign bond markets and it spread subsequently to the interbank market: investors started short-selling their peripheral government bonds, by determining an increase in interest rates and a decrease in prices; after that, peripheral credit institutions were precluded from accessing the interbank market, namely, loans previously granted by other financial institutions were rejected in order to avoid risks of potential losses arising from their exposure to sovereign securities; therefore, the TARGET2 balances can be considered as reflecting the central bank liquidity outflow related to the financial turmoil in sovereign bond markets and the interbank market. As far as the economic policy suggestions are concerned, the peripheral interpretation strongly defends the ECB monetary policy choices; indeed, the non-standard measures allowed the banking sector of the peripheral countries to face with the central bank liquidity outflow and to avoid that a liquidity crisis moved towards a solvency crisis. 5

The core and peripheral interpretation hold differing views with respect to both the determinants of TARGET2 imbalances and the economic policy recommendations; therefore, the analysis of the TARGET2 balances is directly relevant to identify an appropriate economic policy to face the sovereign debt crisis in the EMU.

As for the empirical perspective, the literature did not express a unique position on the determinants of TARGET2 balances. The statistical analysis by Cecioni and Ferrero [18] showed a correlation between TARGET2 imbalances and BoP financial account imbalances, where the latter stemmed from the reallocation of financial assets, as carried out by financial institutions, towards the core countries; otherwise, current account deficits did not provide any explanation for the growing in TARGET2 imbalances, albeit a certain correlation between TARGET2 and current account balances only emerged for Greece in the period preceding the sovereign debt crisis. 6 The econometric analysis by De Grauwe and Ji [11] highlighted the negative and significant impact of the peripheral government bonds’ yields on the TARGET2 imbalances, with the first variable taken as an indicator of the crisis of confidence in the capacity of European institutions to survive; moreover, the authors also showed the cumulated values of the BoP current account deficits not to be correlated with TARGET2 balances. Nevertheless, it is worth stressing that these findings should not be interpreted as a causal link in which the yields are the determinant and the TARGET2 balances the effect: it is also reasonable to think of the increase in sovereign bonds’ yields as a result of the central bank liquidity outflow, that is, of the TARGET2 balances. According to Auer [19], the econometric analysis shows how the evolution of TARGET2 imbalances and of the BoP current account imbalances are not correlated until August 2007, while a strong correlation emerged successively; the author stressed that this result should be interpreted with caution as it simply implies that, during the financial crisis, the current account deficits were increasingly funded through the non-standard monetary policy measures, rather than through private capital inflows. Regarding the reasons behind this, no evidence is provided to support either a re-evaluation of the risk connected to disparities in the level of competitiveness among countries or a confidence crisis in the capacity of the EMU to survive; therefore, the empirical analysis does not appear decisive in settling the question of what affects the TARGET2 balances. As argued in Sinn and Wollmershäuser [4], the persistent deficits in BoP current account accumulated before the crisis have favoured the growing of financial liabilities towards foreign creditors, so that the correlation between TARGET2 balances and financial account balance observed during the sovereign debt crisis could simply reflect the decision of the foreign creditors to short-sell the financial assets hold in the peripheral countries due to an increase in the country risk following the worsening of the economic fundamental. At the same time, the financial resources provided through the non-standard monetary policy measures created the possibility for the peripheral countries to honour the debts incurred in previous years (Merler and Pisany-Ferry [20]).

This paper aims to provide some elements that contribute to shed light on the dynamics of the TARGET2 balances. First, before the financial crisis, the peripheral countries presented various degree of heterogeneity when compared trough different macro indicators of internal and external performance. Within a rather complex picture emerges that some peripheral countries showed soundness in fiscal policies, respecting the Maastricht criteria, as in the cases of Ireland and Spain; some others especially Ireland, as well as Italy, did not present competitiveness challenges, as it is reflected by the positive value of their trade balance. The International Investment Positions (IIPs), however negative, in the case of Spain and Italy, were compensated by a balanced distribution of the sovereign debt between residents and non-residents that limited their external exposure, whereas the government bond shares remaining in the hand of the Irish and the Greek residents were extremely small. Second, a relevant portion of the central bank liquidity outflow from the peripheral countries occurred when the European institutions took some specific policy decisions, and not when disparities in the levels of competitiveness of individual countries emerged: these decisions resulted in the implicit refusal to establish a mechanism which would have acted as lender of last resort in favour of the governments of the peripheral countries. This process led to a severe deterioration in the expectations regarding the solvency of the EMU member States as well as the risk linked to their possible partial or total default; as a result, the fall in the confidence in the ability of EMU to survive induced severe strains on the financial markets. Third, as argued in the literature, fiscal consolidation and real depreciation tend to destabilize an economic system when it is in a negative conjuncture and it is coupled with a monetary policy ineffective in reducing the rate of interest: this logical framework is exactly the one experienced by the peripheral countries. Thus, in deciding and implementing its monetary policy, the ECB held its legitimate and unavoidable role of lender of last resort in order to avoid a liquidity crisis for the credit institutions, while the lack of a European institution that took on the same responsibility toward the member States resulted in the escalation of the debt crisis. The sovereign debt crisis in the Eurozone showed signs of reversal only when the ECB satisfied the inevitable need to implicitly assume, so far credibly and under specific conditions, the role of lender of last resort for the EMU member States.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 briefly defines the features of a lender of last resort and how the ECB decides and implements the monetary policy; moreover, it describes the working mechanism of the TARGET2 system and illustrates the economical meaning of its balances. Section 3 offers an outline of the different dimensions of macroeconomic heterogeneity across the peripheral countries between 1999 and 2000 and reads the dynamic of the TARGET balances in the light of some key political decision adopted by European institutions. Section 4 stresses the legitimacy of the ECB’s monetary policy choices as pertaining to its role of lender of last resort for the credit institutions, and it points out how the economic context in the peripheral countries justified the need of a lender of last resort also in favour of EMU member States. Section 5 summarizes some conclusions.

2. The ECB as a Lender of Last Resort and the Potential Reflections in the TARGET2 System

The first consolidated theory for successful lending of last resort operations were described by Bagehot in 1873. Left unchanged, the core principles illustrated by the author, over time, the design of the lender of the last resort role evolved according to the necessities of the financial and economic system. A general definition of lender of last resort can call on one or more institutions which provide unlimited liquidity assistance to other institutions when an uncommon demand of liquidity arises and when other mechanisms are not able to face with the status quo. The intervention of a lender of last resort aims to ensure the stability in financial markets, to avoid the outbreak of liquidity crisis and to prevent them to turn into solvency crisis.

The definition of lender of last resort encompasses several aspects among which the most prominent are: (a) identifying the lender institution; (b) determining the scale and the timing of the liquidity supply; (c) identifying the borrower institutions; (d) fixing the conditions of the lending procedure. The role of lender of last resort can be broader or narrower according to the interpretation given to the last two points. Following this scheme, in principle, the role of lender of last resort can be played by different actors such as national central banks, international organizations, ad hoc institutions, or institutions bearing other responsibilities as well (Buiter and Rahbari [21]). In the case of a central bank, this role can be performed along with the ones of ensuring the price and the economic stability. Further to this, the lender of last resort needs to be willing to use all the resources at its disposal, and it has to be recognized as such by the market establishing a solid reputation. The liquidity required to face the credit demand has to be immediate and unlimited. As far as the borrower institution is concerned, it can be either a financial institution, a government or both. Whether the government can be included or not among the potential receivers of the emergency liquidity depends on the interpretation given to the concepts of illiquidity and insolvency, whose frontier can be blurry in some cases (De Grauwe [22] (p. 528)). Further to this, it is possible to set ex ante and ex post conditions against which the potential borrower can actually obtain the liquidity needed. 7

The European System of Central Banks (ESBC), that includes the ECB and the national central banks of European Union member States, has the principal aim of guaranteeing the price stability. In this view it defines and implements the monetary policy. The ESBC is directed by the ECB’s decision-making bodies, namely, the Governing Council and the Executive Board. The ECB function is to assure that the tasks assigned to the ESBC are carried out either by its own activities or by those of the national central banks. 8 Referring to these latter, the article 12, first paragraph, of the Statute of the ESCB and of the ECB states: “(…) The Executive Board shall implement monetary policy in accordance with the guidelines and decisions laid down by the Governing Council. In doing so the Executive Board shall give the necessary instructions to national central banks. (…) To the extent deemed possible and appropriate (…) the ECB shall have recourse to the national central banks to carry out operations which form part of the tasks of the ESCB”. Therefore, the ECB, as the decision-making body of the ESBC, decides and implements the monetary policy with the operational support of the national central banks of the EMU member States. These latter, together with the ECB, constitutes the Eurosystem. 9

A wide part of the literature, Buiter and Rahbari [21], De Grauwe [22], Hu [24], Micossi [25], recognizes the ECB as acting in the role of lender of last resort during the sovereign debt crisis, although is debated the precise moment this role was acquired, which were the instruments used to carry it out and whether the ECB was acting alone or in liaison with other institutions; in our view, the monetary policy decided and implemented by the ECB stems from its legitimate and unavoidable role of lender of last resort for credit institutions to avoid liquidity crisis.

The TARGET2 system is a settlement infrastructure that allows the smooth regulation of those payments linked to financial institutions transactions and monetary policy operations implemented by the Eurosystem, including those that can be attributable to the role of lender of last resort carried out by the ECB. This infrastructure connects all the Eurosystem members, with the ECB that acts as a clearing house for the national central banks in the countries that adopted the euro; payments are regulated through claims and liabilities recorded in the national central banks and imputable to the national financial institutions. The transactions among financial institutions belonging to different countries are necessarily associated with cross-country central bank liquidity transfer; otherwise, monetary policy operations are not related to cross-country central bank liquidity transfer because they are implemented by the national central banks and their domestic financial institutions. As a result, the TARGET2 balance, namely, the net position of each national central bank towards the ECB, gives an indication on the geographical redistribution of the central bank liquidity compared to the original distribution set up by the monetary policy operations.

The following example describes the working mechanism of the TARGET2 system. Suppose that a national central bank of country A makes a payment to a central bank of country B; the national central banks operate on behalf of financial institutions located in the two countries that, in turns, operate on the request of their customers. In this case, the current account of the financial institution of country A, held at the national central bank of country A, is debited, while the current account of the financial institution of country B, held at the national central bank of country B, is credited. At the end of the accounting day, unless the liquidity outflow (inflow) is compensated by an opposite transaction of the same amount involving whatever actor of the market, excluding directly the ECB, the national central bank’s balance sheet of country A (country B) is accounted as having a TARGET liability (claim) towards the ECB (see Table 1). 10 Summing up, regardless of the reasons of this occurrence, the lack of liquidity flows of the same amount but of the opposite sign—among the countries connected to the TARGET2 system via their national banks—generates TARGET2 imbalances.

Table 1.

TARGET2 system and accounting balances.

| Financial Institution—Country A | National Central Bank—Country A | ||

| Assets | Liabilities | Assets | Liabilities |

| −Δ debits financial institution B | +Δ loans financial institution A | −Δ deposits financial institution A | |

| −Δ deposits National central bank A | +Δ loans National central bank A | +Δ liabilities TARGET2 ECB | |

| European Central Bank | |||

| Assets | Liabilities | ||

| +Δ claims TARGET2 National central bank A | +Δ liabilities TARGET2 National central bank B | ||

| National Central Bank—Country B | Financial Institution—Country B | ||

| Assets | Liabilities | Assets | Liabilities |

| −Δ loans financial institution B | +Δ deposits financial institution B | −Δ credits financial institution A | |

| +Δ claim TARGET2 ECB | +Δ deposits National central bank B | −Δ loans National central bank B | |

The TARGET2 entries (claims and liabilities) trace how the central bank liquidity moves across EMU member States. When the TARGET2 balance against the ECB, defined as the difference between claim and liabilities as accounted in the balance sheet of a national central bank, is zero this means that central bank liquidity inflow and outflow balance out perfectly, whereas being the balance positive or negative this would indicate, respectively, an inflow or an outflow of central bank liquidity. In brief, TARGET2 balances define how the geographical distribution of the central bank liquidity changes with respect to the original one as it is determined by the monetary policy operations implemented by the Eurosystem.

To the extent that national credit institutions can withstand an outflow of central bank liquidity by using the standard measures of monetary policy, TARGET2 imbalances only describe the ordinary working of a monetary union; otherwise, when the Eurosystem is forced to implement non-standard measures in order to support credit institutions, TARGET2 imbalances could indicate an increasing risk of a liquidity crisis for countries experiencing an outflow of central bank liquidity.

3. The Determinants of the Dynamic of the TARGET2 Balances

The financial crisis, culminated with the collapse of the investment bank Lehman Brothers, resulted in a reduction of the GDP over the years 2008–2009, the following moderate economic recovery was soon interrupted. The transition between the financial crisis and the sovereign debt crisis started at the end of 2009 when serious doubt on the accuracy of the Greek fiscal account data emerged. When, in spring 2010, Greece turned for help to the European Union and the International Monetary Fund, the attention of international investors to sovereign risk in the Euro area intensified. Rapidly, the debt crisis extended, for different reasons, first to Ireland (November 2010) and then to Portugal (April 2011) asking for assistance facilities as well. A further escalation of the debt crisis occurred starting in July 2011 with the announcement of a plan for the restructuring of Greek sovereign debt. In this case, the crisis was not restricted to slight economies of Euro Area, but it also involved the economies of Italy and Spain, with their total GDP which amounted to 27.7 per cent of the Euro area GDP in 2011. The contagion was reflected in a rapid increase of the spreads between the sovereign bonds’ yield of the peripheral countries and of Germany.

In the remainder of this section, first of all, we describe the main features of peripheral economies at the beginning of the sovereign crisis; then, we analyse the dynamic of the TARGET balances in the light of some key political decision adopted by European institutions.

3.1. Macroeconomic Performance of the Peripheral Member States between the Adoption of the Euro and the Financial Crisis

Before the financial crisis, the peripheral countries presented various degree of heterogeneity when compared trough different macro indicators. With the aim of highlighting the complex picture developed between the adoption of the Euro 11 and 2007, we refer to several measures of internal and external performance, benchmarked against Germany. More specifically, the analysis of the real growth and of the value added by sector allows having a first insight on the economic performance, whereas the debt-to-GDP ratio, along with the government deficit/surplus-to-GDP ratio, indicates the degree of fiscal prudence of the different member States. A breakdown of the driving components of the current account shows that for some peripheral countries non-trade dynamic played a crucial role. Further insights are provided by the analysis of the net International Investment Positions (IIPs) that, although mirroring the current account balance, is driven as well by price and exchange rate variations. Finally, a combined investigation of the IIP, the debt-to-GDP ratio and the distribution of the sovereign debt between residents and non-residents gives a further measure of the degree of external exposure. All the data referred to in this section are collected in Appendix (Table A1).

In terms of growth performance, a glance at the average real GDP growth reveals all the peripheral countries experiencing a positive rate with an overall average of 3.5 per cent of GDP. Ireland enjoyed the highest growth average rate, 6.4 per cent, followed by Greece and Spain in the range of 4.0 per cent and by Portugal and Italy with 1.8 per cent and 1.5 per cent, respectively. Germany recorded an average real GDP growth rate of 1.6 per cent. More details derive from investigating the contribution to the total value added of the different sectors. 12 Ireland registered 27.0 per cent of the total in the industry sector followed by Germany and Italy with 26.0 and 21.0 per cent of the total, respectively. The construction sector saw Spain with more than 10.0 per cent of the total compared to Ireland, Greece and Portugal that reached between 7.0 and 8.0 percent. Wholesale and retail trade were particularly strong in Greece, Spain, Italy and Portugal. In all the three cases the per cent of the total always exceeded 20.0. In the real estate sector service Germany, Greece and Italy reached a similar level accounting for a portion of around 11.0 per cent of the total. For financial services, Ireland had the highest share of almost 9.0 per cent of the total.

As regard as fiscal position, Ireland and Spain showed prudence in managing the government balance (as shown by a surplus of 1.6 and 0.2 per cent of GDP, respectively) and outperformed Italy, Germany and Portugal that presented negative signs. 13 In 1999, Italy, with a debt-to-GDP ratio of 110.0 per cent, and Greece 14 were the countries not respecting the Maastricht criterion. Germany and Spain were slightly above the threshold, with 60.2 and 60.9 per cent of the GDP, respectively. Portugal and Ireland performed even better with a 51.0 and 47.0 per cent of the GDP, respectively. Over the period, in Ireland and in Spain the debt-to-GDP ratio reduced with an annual average of 7.8 and 6.5 per cent, respectively. In Italy, a moderate increase was registered. Portugal and Germany showed an increase in the ratio of 3.2 per cent and 0.8 per cent, respectively.

Over the same period, the Euro area maintained a roughly balanced current account with respect to the rest of the world, but, within the area sustained, imbalances emerged. In a monetary union, the increasing integration of financial markets can subsidize saving-investment imbalances and allows for an efficient allocation of capital, promoting, this way, the economic convergence of countries. On the other hand, the impossibility of using the exchange rate as a tool for correcting long-lasting saving-investment imbalances represents a relevant limit. To what extent the current account balances are of concern within a monetary union is still under careful scrutiny by the literature (Holinsky et al. [26]). On average over the period 1999–2007, all the peripheral member States faced a deficit in the current account of the BoP that ranged between 9.3 per cent of GDP in the case of Portugal to 0.5 per cent of GDP in the case of Italy. Conversely, Germany runs a current account surplus of 2.7 per cent of GDP. In determining the overall value of the current account balance, non-trade dynamics played an important role. In terms of composition of the current account balance, among peripheral member States, two groups can be distinguished. The first one includes Italy and Ireland where non-trade components of the current account were, in different scales, the main drivers of the overall current account deficit; more specifically, for Ireland the negative net income had the main role whereas in Italy both negative income and transfers counted. 15 The second one includes Greece, Spain and Portugal in which the trade components and non-trade components were both accountable for the overall current account deficit; as a subgroup, Greece and Portugal shared the evidence that positive value of net transfer and negative value of net income offset each other. The case of Ireland is illustrative in showing that the reason behind the small positive surplus of the current account did not concern its competitiveness sphere. Some favourable geographical characteristics, along with a low level of corporate income taxes, made Ireland an ideal location for receiving foreign direct investments, especially from multinational enterprises. A further decomposition of the net income, confirms that repatriation of the multinational profits was the main driver of the overall value of income: on average, the direct investment amounted to −17.0 per cent of the GDP (with dividends and distributed branch profits amounting to −11.0 per cent of GDP, reinvested earnings and undistributed branch profits amounting to −6.0 per cent and interest on debt amounting to 0.4 per cent); portfolio investments were almost balanced. In Italy, the worsening in the net income position was caused by the widening of the gap between the value of the Italian bonds held by non-residents and the value of foreign equities held by Italian residents. In the lack of data for the subcategories of transfers up to 2007 is not possible to disentangle the main drivers for this period as regards the overall level of transfers; however, it can be noticed that, starting in 2008, the contribution of the foreign worker’s remittances stays constant, whereas the current transfer by general government has an increasingly negative impact, mainly due to the Italy’s net contribution to the EU budget.

The countries that accumulated current account deficits (surpluses) registered as well negative (positive) IIPs. During the pre-crisis period, net IIPs displayed diverging trends across countries: particularly, Greece, Portugal and Spain registered a rapid deterioration. Although mirroring the development of the current account balance, net IIP development may differ significantly from the current account development because of the valuation effects linked to market prices, used for estimating financial assets and liabilities, and to exchange rate movements. In the period 2000–2007, all the peripheral countries displayed negative net IIPs ranging from −60.0 per cent of the GDP in Greece to −8.0 per cent in Ireland; Germany, on the contrary, displayed a positive 12.0 per cent of GDP. The decomposition of the changes in net IIPs shows that the main driver was, in all the cases with the exception of Germany, the valuation effect: −5.0 per cent of the GDP for Greece, −4.5 per cent for Ireland, −4.0 per cent for Spain and −3.2 per cent for Italy; in Germany the valuation effect was slightly positive. In turn the explanations behind the valuation effects can be different depending on the countries considered. In the case of Ireland, the dimension of the valuation effect can be attributed to the large gross asset and liability position: limited price changes cause large valuation variations. In Greece as well as in Spain, instead, the valuation effect was linked to price variations. In the case of Italy, which holds a relevant portion of assets in foreign currencies, the main driver of the deterioration of the net IIP was explained by the appreciation of the Euro compared to the US dollar.

An additional dimension of the heterogeneity among member States can be given by the joint analysis of the IIP, the government debt-to-GDP ratio and the distribution of the sovereign debt between resident and non-residents. High government debt-to-GDP ratios are of a major concern when held by non-residents; in this case, both the expenditure for servicing the debt increases and the tax revenue on interest shrinks, and this condition is aggravated when combined with negative net IIPs. It worth recalling that in terms of debt-to-GDP ratio and on average in the 1999–2007 period Italy and Greece were above 100.0 per cent, Germany and Portugal in the vicinity of 60.0 per cent, Spain at 48.0 per cent and Ireland at 31.0 per cent. As regard as the distribution of the sovereign bonds between resident and non-residents, in 1999, Greece, Spain and Italy, had a share of debt hold by residents in a range between 66.0 per cent (Greece) and 69.0 per cent (Spain), while Portugal and Ireland saw a share of 45.0 per cent. 16 In 2007, the picture completely changed with Greece and Portugal residents owing, respectively, 29.0 per cent and 24.0 per cent of the total sovereign debt and for Ireland the quota was only 10.0 per cent; the situation in Italy and Spain was more stable with a share of 50.0 per cent in both cases. These data cross-referenced with those of the external position give further hints about the vulnerability of a country: the position of Italy, for example, was not particularly challenging because of the limited negative IIP and the balanced share of debt between residents and non-residents.

The picture sketched so far shows that, in the period 1999–2007, among peripheral countries, some respected the Maastricht criterion of the debt-to-GDP ratio (as in the case of Ireland and Portugal) exhibiting, as well, prudency in fiscal policy (as in the of Ireland and Spain). Ireland and, to a lesser extent, Italy did not presented competitiveness challenges, as it is reflected by the positive value of their trade balance, whereas non-trade components are the main drivers of the negative net values of their current accounts. The net IIP in 1999 was extremely positive in Ireland and slightly negative in Italy. The situation deteriorated for all the peripheral member States that, to different extent, registered negative values in 2007. In the group, the worse fall in the IIP, in 2007, was registered by Ireland, whereas Italy’s loss was moderate. Furthermore, the IIPs, however negative, in the case of Spain and Italy, were compensated by a balanced distribution of the sovereign debt between residents and non-residents that limited their external exposure, whereas the government bonds remaining in the hand of Irish and Greek residents was extremely small.

3.2. Political Decisions and the TARGET2 Imbalances

Within the peripheral interpretation, TARGET2 imbalances reflected a decisive fall in the level of confidence towards the ability of European institutions to face with the sovereign debt crisis. In line with this position, it can be argued that the dynamic of TARGET2 imbalances was closely related to the pattern followed by European institutions in taking certain key political decisions. Indeed, the TARGET2 imbalances revealed a tendency of accumulating before and after those choices that proved decisive in influencing the perceptions of the level of cohesion shown by European institutions in facing the crisis.

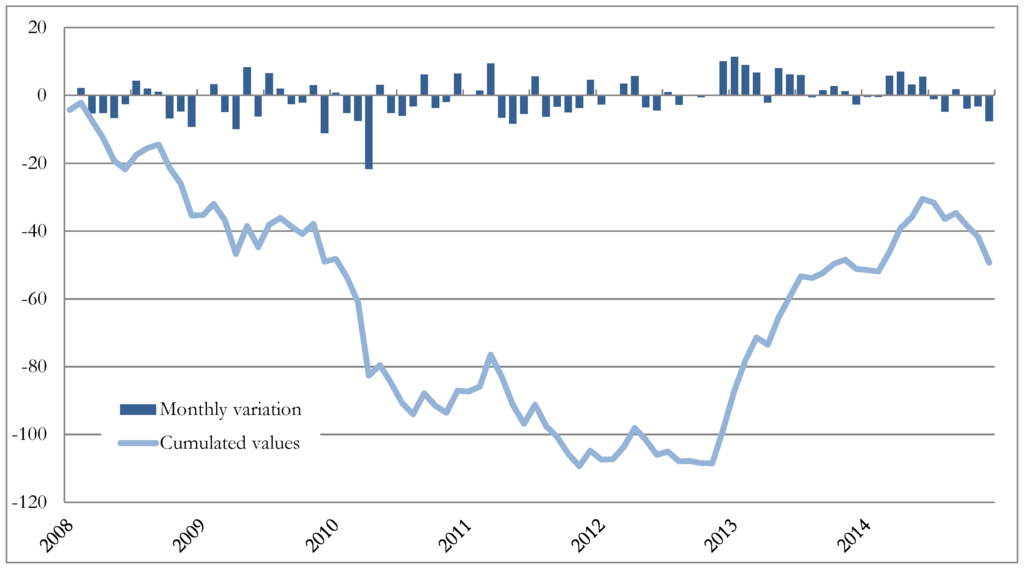

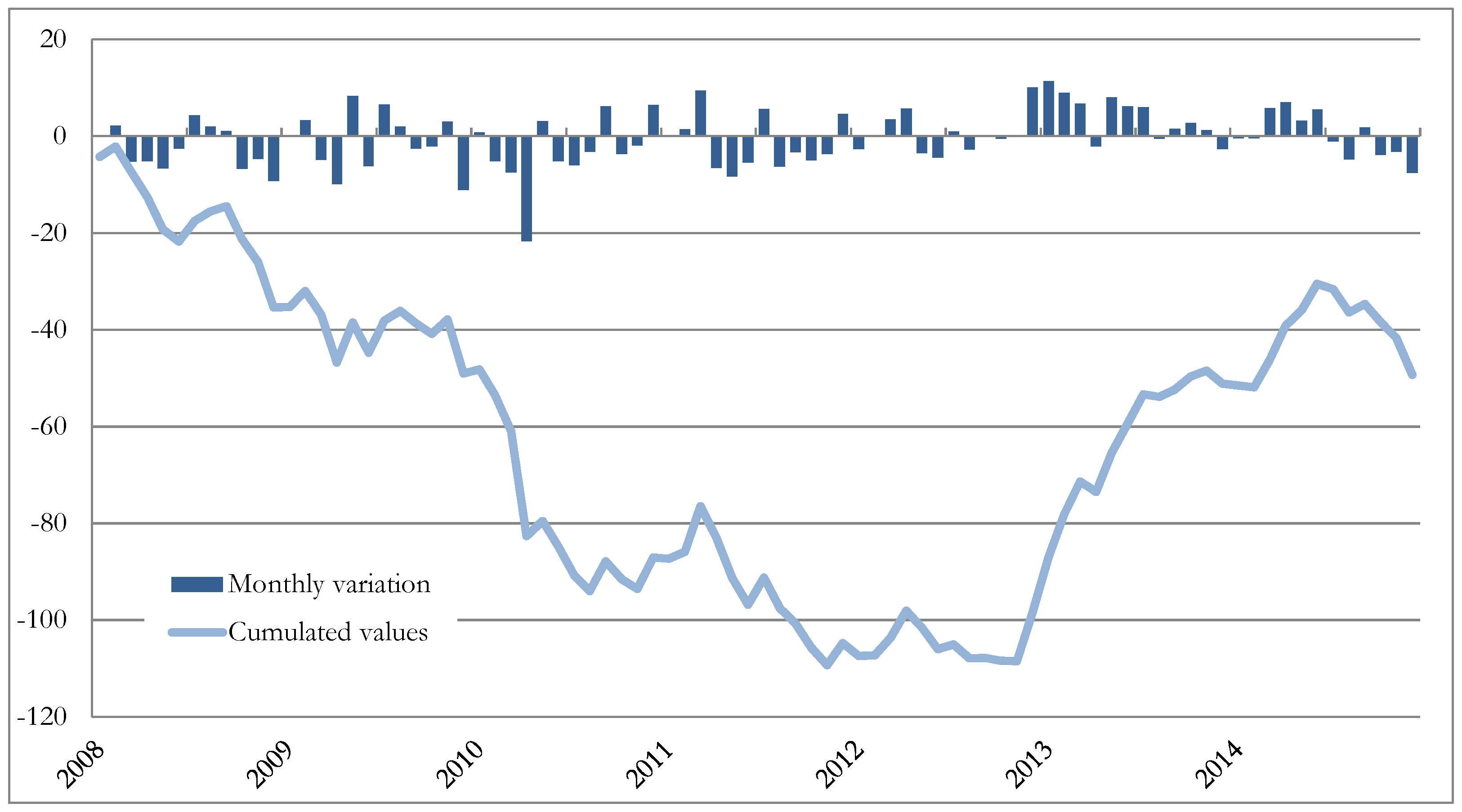

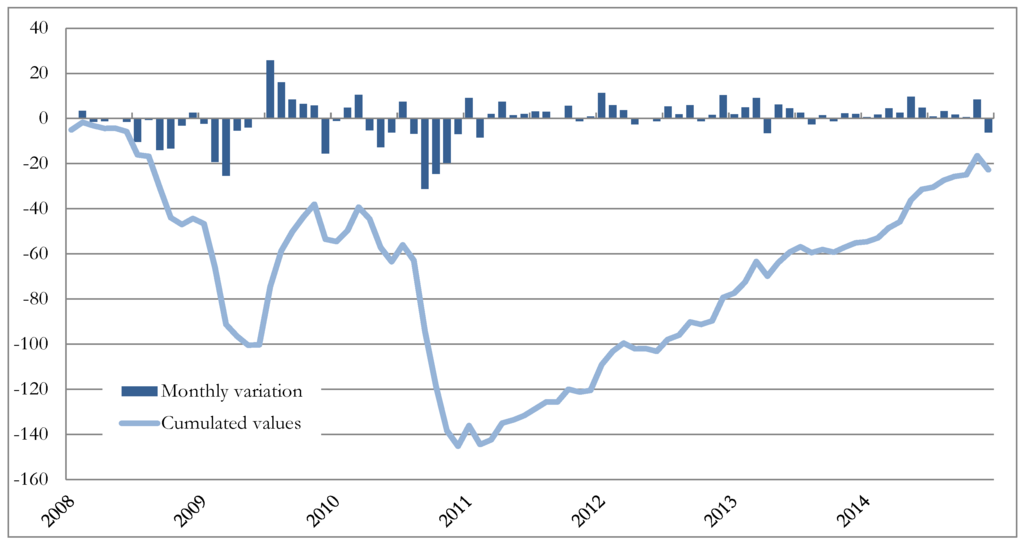

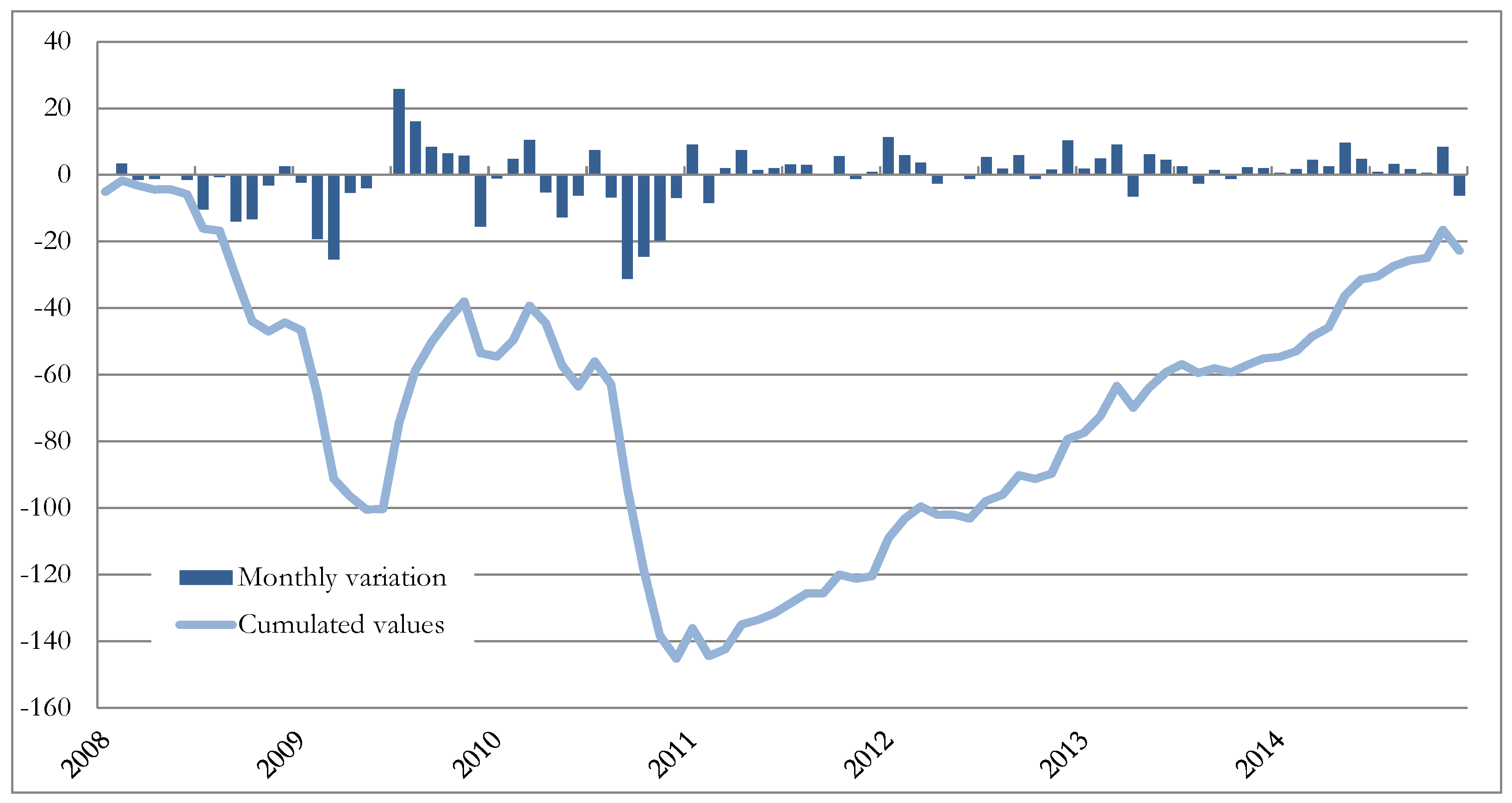

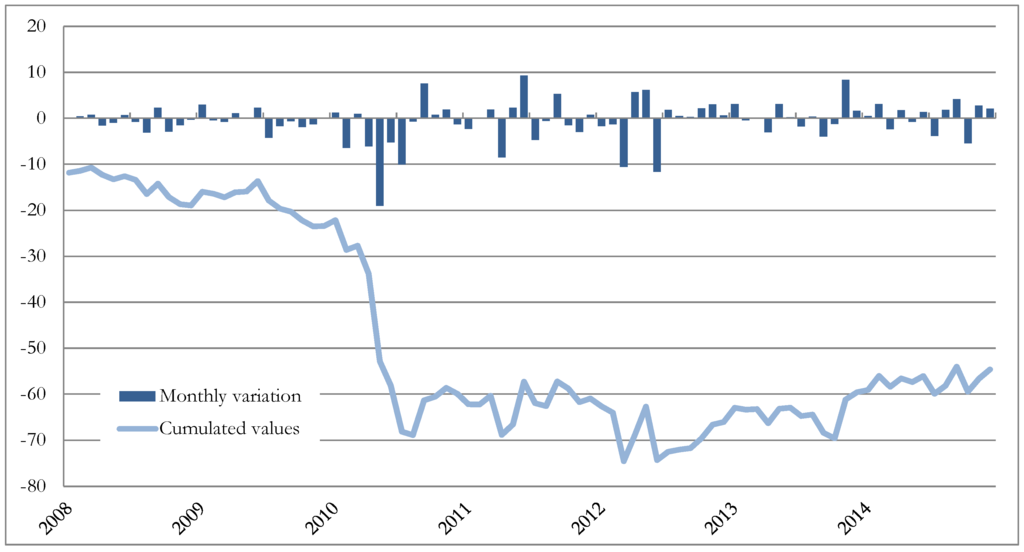

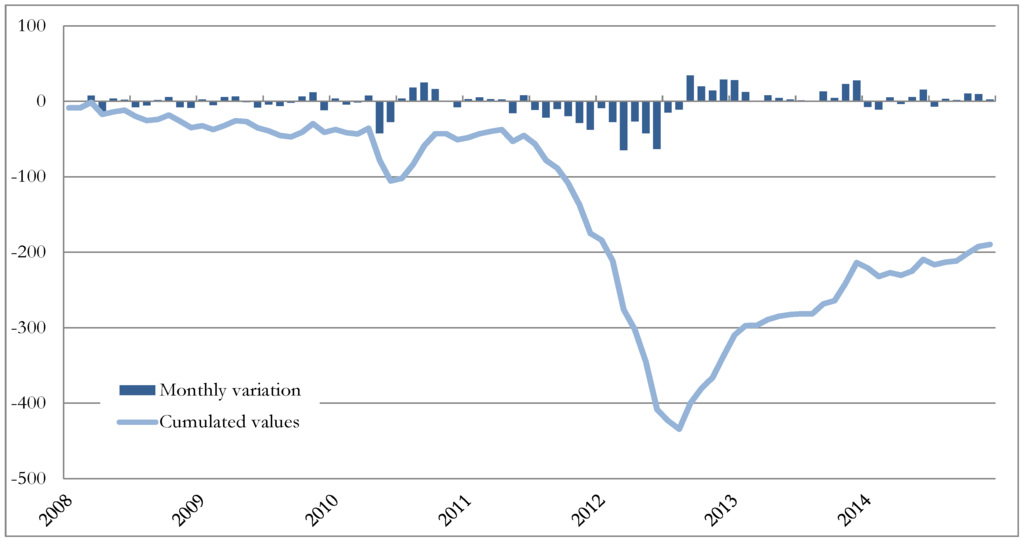

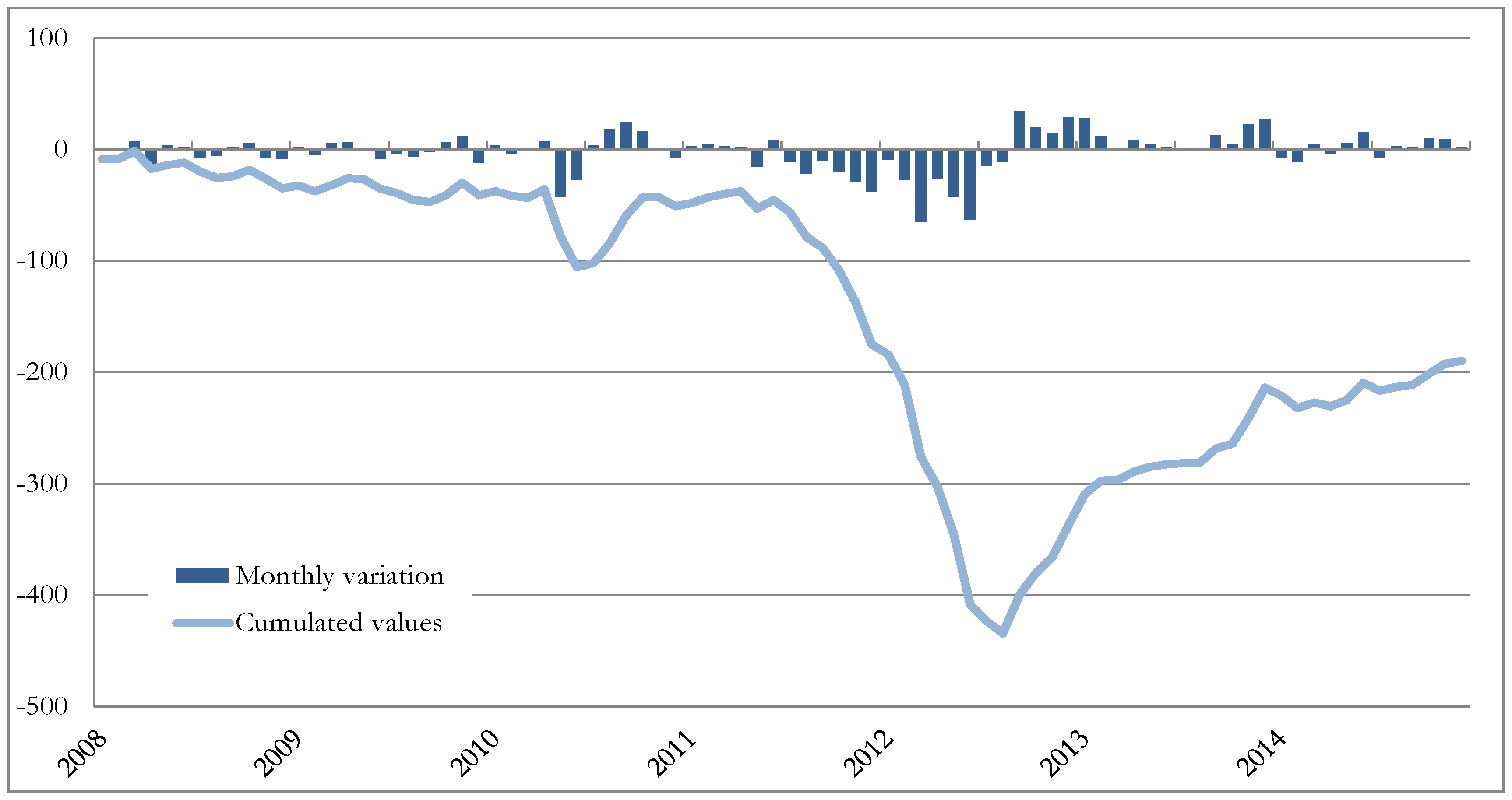

In Greece and Ireland, the TARGET2 liabilities accumulated rapidly in the months preceding the request for financial support to European institutions and the launch of the economic and financial adjustment programmes, in May and December of 2010, respectively. In Greece, which registered its maximum of cumulated liabilities in November 2011, amounting to 109.3 billion euro, the 38.1 per cent of the total amount was accumulated between November 2009 and April 2010 (Figure 2). Ireland’s total TARGET2 liabilities reached their peak at 145.2 billion euro in December 2010 and 56.7 per cent of this amount was accumulated from August 2010 to November 2010 (Figure 3). In Portugal, 47.1 percent of the maximum liabilities of 74.5 billion euro (March 2012) was accumulated between April and July 2010, one year before the request for financial support (Figure 4).

The outflow of financial resources from these countries could be considered as a result of the uncertainty about the sustainability of public finances, albeit the reasons for the uncertainty differed across countries: in Greece, the size of the public sector budget deficit, hidden thanks to accounting artifices; in Ireland, the magnitude of the financial support the government guaranteed to the banking sector; in Portugal, the extension of the public sector overloaded by inefficient companies. Nevertheless, it can also be argued that financial markets were plagued primarily by the doubts about the ability of European institutions to be sufficiently cohesive in planning and deciding for an effective stabilizing economic policy; indeed, in Greece and Portugal, the TARGET2 liabilities did not begin to reduce when the adjustment programmes were launched. 17

Figure 2.

TARGET2 balances towards the Eurosystem, Greece (Euro billion, monthly, end of the period). Source: Elaboration on the “Institute of Empirical Economic Research—Osnabrück University” dataset (accessed on 25 June 2015, http://www.eurocrisismonitor.com/).

Figure 2.

TARGET2 balances towards the Eurosystem, Greece (Euro billion, monthly, end of the period). Source: Elaboration on the “Institute of Empirical Economic Research—Osnabrück University” dataset (accessed on 25 June 2015, http://www.eurocrisismonitor.com/).

Figure 3.

TARGET2 balances towards the Eurosystem, Ireland (Euro billion, monthly, end of the period). Source: Elaboration on the “Institute of Empirical Economic Research—Osnabrück University” dataset (accessed on 25 June 2015, http://www.eurocrisismonitor.com/).

Figure 3.

TARGET2 balances towards the Eurosystem, Ireland (Euro billion, monthly, end of the period). Source: Elaboration on the “Institute of Empirical Economic Research—Osnabrück University” dataset (accessed on 25 June 2015, http://www.eurocrisismonitor.com/).

Figure 4.

TARGET2 balances towards the Eurosystem, Portugal (Euro billion, monthly, end of the period). Source: Elaboration on the “Institute of Empirical Economic Research—Osnabrück University” dataset (accessed on 25 June 2015, http://www.eurocrisismonitor.com/).

Figure 4.

TARGET2 balances towards the Eurosystem, Portugal (Euro billion, monthly, end of the period). Source: Elaboration on the “Institute of Empirical Economic Research—Osnabrück University” dataset (accessed on 25 June 2015, http://www.eurocrisismonitor.com/).

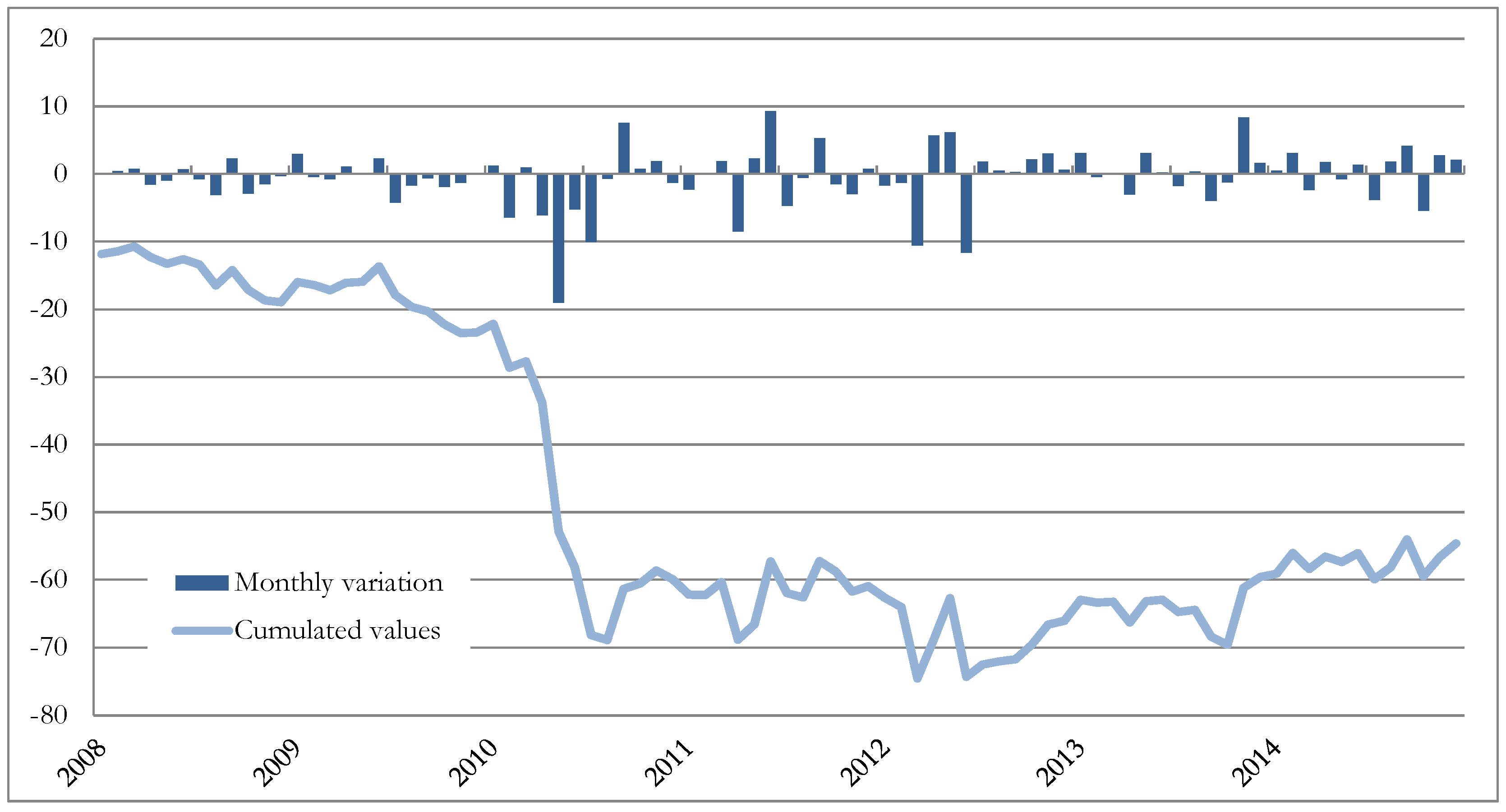

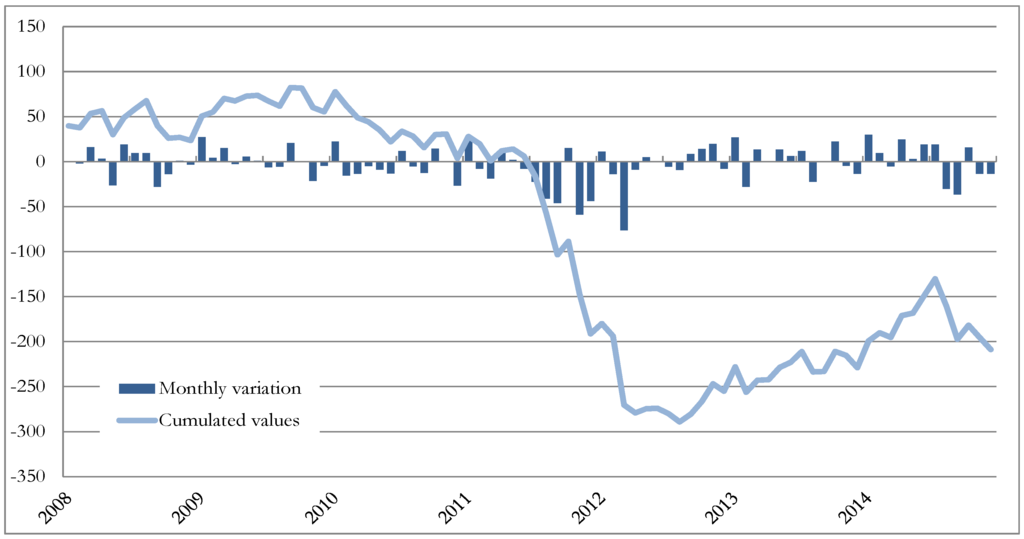

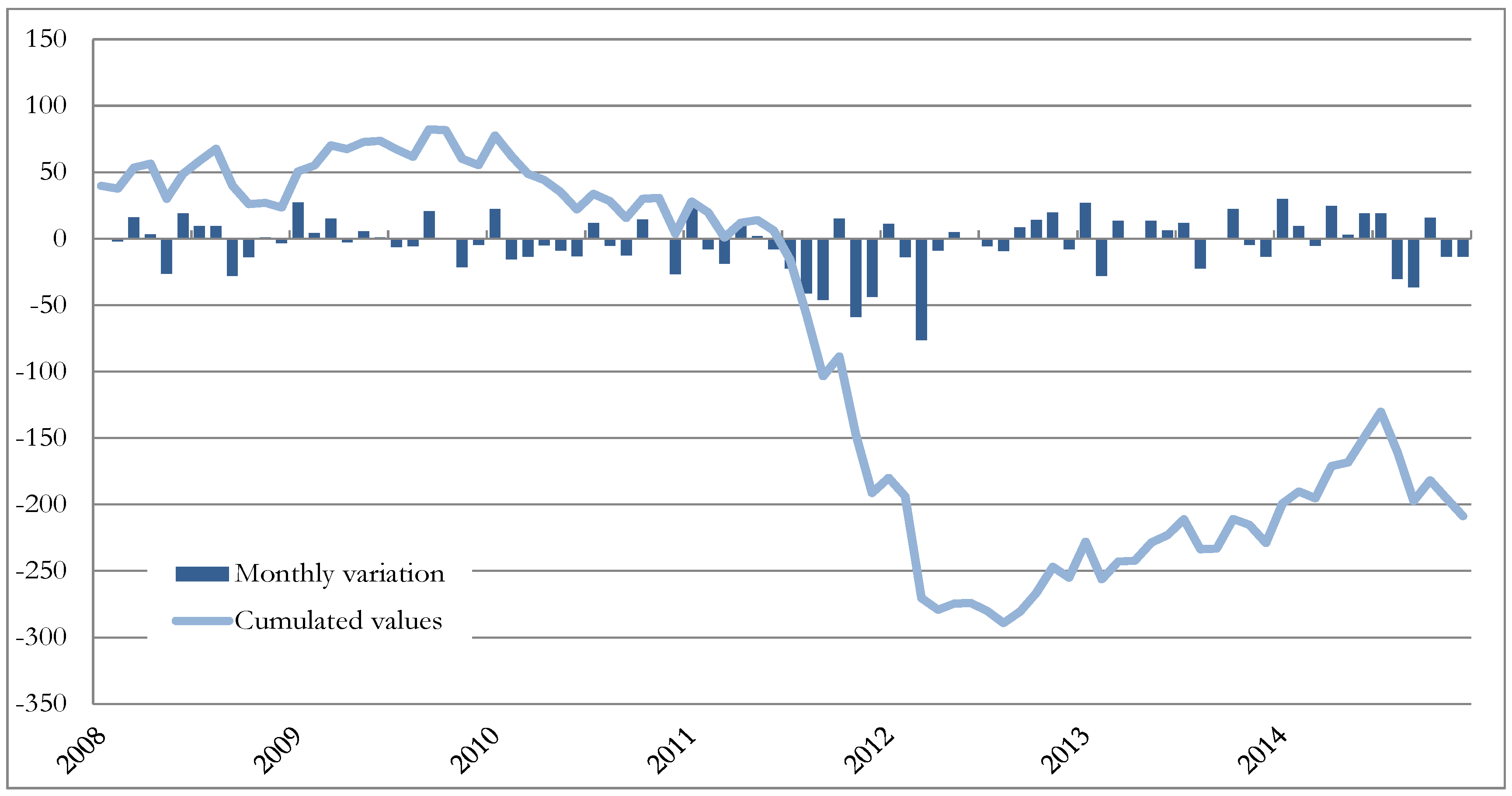

A close examination on how TARGET2 balances evolved in Italy and Spain further supports the view that financial markets were mainly plagued by the above-mentioned doubt regarding the ability of European institutions to face with the sovereign crisis. In both Italy and Spain, the surge in cumulated liabilities started in July 2011 and lasted until August 2012, when TARGET2 liabilities reached their peak with values of 289.3 and 434.4 billion euro, respectively. These values were substantially higher than those of other countries (Figure 5 and Figure 6). In Italy, the surge was more intense during the first seven months, while in Spain it occurred in the last seven months: in these periods, 61.5 per cent and 57.7 per cent of the peak value was accumulated, respectively; furthermore, in February 2012, a strong monthly increase of 76.3 billion euro in Italy and 64.6 billion in Spain was registered. Starting from August 2012, the cumulative TARGET2 liabilities decrease in both countries: in Italy the contraction was of 80.4 billion euro, with a cumulative value equal to 208.9 in December 2014; in Spain it was of 244.5 billion euro, with a cumulative value of 189.9 in December 2014. 18

The analysis just presented allows us to identify three key moments within the evolution of the TARGET2 balances: July 2011, February–March 2012 and July–September 2012. Each of them represents a block in the political and economic architecture that the European institutions have been designing in order to face with the sovereign debt crisis.

Figure 5.

TARGET2 balances towards the Eurosystem, Spain (Euro billion, monthly, end of the period). Source: Elaboration on the “Institute of Empirical Economic Research—Osnabrück University” dataset (accessed on 25 June 2015, http://www.eurocrisismonitor.com/).

Figure 5.

TARGET2 balances towards the Eurosystem, Spain (Euro billion, monthly, end of the period). Source: Elaboration on the “Institute of Empirical Economic Research—Osnabrück University” dataset (accessed on 25 June 2015, http://www.eurocrisismonitor.com/).

Figure 6.

TARGET2 balances towards the Eurosystem, Italy (Euro billion, monthly, end of the period). Source: Elaboration on the “Institute of Empirical Economic Research—Osnabrück University” dataset (accessed on 25 June 2015, http://www.eurocrisismonitor.com/).

Figure 6.

TARGET2 balances towards the Eurosystem, Italy (Euro billion, monthly, end of the period). Source: Elaboration on the “Institute of Empirical Economic Research—Osnabrück University” dataset (accessed on 25 June 2015, http://www.eurocrisismonitor.com/).

On July 21, 2011, the heads of State and Government of the Euro area and of the EU institutions expressed their support for the voluntary involvement of the private sector, and in particular of credit institutions, in the second financial and economic adjustment programme for Greece. The contribution of the private sector was estimated at a total amount of 106.0 billion euro for the period 2011–2019 (Council of the European Union [27]). In February 2012, the voluntary involvement of the private sector took the form of an official agreement: the Private Sector Involvement (PSI). Based on the PSI, private investors accepted to write off 53.5 per cent of the face value of the Greek government bonds they held. The above-mentioned declaration showed the inadequacy of the first adjustment programme to stabilize the Greek economy and, consequently, the impossibility for the Greek Government to honour its sovereign signature. Despite the voluntary nature of the agreement, indeed, its acceptance implied a partial Greek default. The same conclusion can be also reached by the fact that, within the same declaration, the heads of State and Government reiterated their commitment to honour the sovereign signature and stressed that the solution adopted for the case of Greece constituted an exception.

The then-president of the ECB, Jean Claude Trichet, during the press conferences held for the monthly meeting of the Governing Council regarding monetary policy, repeatedly warned about the possible consequences of a partial default by Greece. Such an event would have fuelled a considerable volatility in the financial markets rather than concur to stabilize the Greek economy (ECB [28,29]). A year later, the analysis conducted by the ECB confirmed the concerns of its former president. July 2011 represented a turning point for the sovereign debt crisis: tensions in the bond and interbank markets intensified resulting both in a decrease in the efficiency of the transmission mechanism of the monetary policy and in a reduction of the credit in favour of families and enterprises (ECB [30] (p. 59)).

On March 30, 2012, the Eurogroup 19 set the overall lending capacity of the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) 20 and the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) at 700.0 billion euro (Eurogroup [31]). This decision can be considered as the final step in the reforming process launched by the European institutions to prevent and manage instability situations of states within the EMU.

The first element of this process was indubitably represented by the treaty establishing the ESM, signed on February 2, 2012 by the EMU member States. The ESM is an intergovernmental institution with the task of managing financial support programmes in favour of the government of the Euro area countries; in order to finance these support programmes, this institution can issue debt instruments; with these characteristics, the ESM represents a permanent crisis resolution mechanism for the Euro area. The second element was the “Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance in the Economic and Monetary Union”, signed on March 2, 2012 by the Heads of State and Government of all European Union member States. 21 This Treaty, among other things, laid down that: (a) the structural budget deficit in public administration, adjusted for the business cycle, must not exceed 0.5 per cent of GDP expressed at market prices, with the obligation to incorporate this budget rule into the national legislation, preferably at the level of constitutional law (Article 3, paragraph one and two); (b) the contracting parties had to reduce by one twentieth per year their rate of general government debt-to-GDP ratio when it exceeded the reference value of 60.0 per cent (Article 4). The third element was the approval, in November 2011, by the European Parliament and the Council of the European Union, of the new regulations pertaining the procedures and sanctions aimed at preventing and correcting the macroeconomic imbalances, in general, and the excessive deficit of the structural budget of public administration, in particular. 22

The fiscal consolidation and the austerity policy have been the guiding principles of the whole process of reform. However, just when the European institutions accomplished this process, tensions in the financial markets showed a marked deterioration, as suggested by the evolution of the TARGET2 balances. 23 From our point of view, the reason for the renewed pressure lies in the fact that the markets evaluated the resources allocated through the EFSF and the ESM as insufficient: of the 700.0 billion euro allocated, roughly 188.4 were already committed to Greece, Ireland and Portugal, while, in March 2012, the public debt of Italy and Spain alone amounted to over 2560.0 billion euro, rendering any support to these countries problematic in case they had requested access to a program of financial support. Within the picture just described, the decision to set the total lending capacity of the EFSF and the ESM to 700.0 billion euro was not a credible reassurance for those who assumed that the EMU might not have survived the crisis. In this regard, it is worth noting that, in signing the Treaty which established the ESM, Euro area States reiterated that the assessment of lending capacity adapted to the needs would have to be carried out by March 2012 (Council of the European Union [32]). The fact that this assessment was not completed until the 30th of March suggests a certain reluctance by the various states to commit resources to financial aid programmes.

On August 2, 2012, during the press conference following the Governing Council meeting dedicated to monetary policy decisions, Mario Draghi, the President of the ECB, outlined the underlying principles of Outright Monetary Transactions (OMTs). The OMTs defined a new sovereign bond-buying programme designed to replace the Securities Market Program (SMP) 24 in force since May 10, 2010 (ECB [33]). Just a few days before, President Draghi (ECB [14]) claimed: “Within our mandate, the ECB is ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the euro. And believe me, it will be enough”.

On September 6, 2012 the technical aspects of the programme were further explained at the press conference (ECB [34]). The programme has been designed to eliminate price distortions in the sovereign bond market due to the non-acceptable hypothesis of a return to national currencies. This aim was pursued by setting up an unlimited buying capacity of one to three year bonds to be held upon maturity. Countries eligible for the OMTs, namely, the ones which can issue these bonds, should first have participated in a support programme through the EFSF or the ESM, and should have fulfilled the conditions required by these programmes. Furthermore, the ECB had full discretion for activating, continuing or discontinuing the programme for any specific country and, consistent with pursuing the price stability, sterilized any liquidity injected through the OMTs.

Compared with the SMP, the OMTs made, on the one hand, the conditionality principle more stringent, as only those countries that were able to effectively implement the interventions required by the financial support programme would have benefited from the ECB support on the secondary market. On the other hand, the OMTs created the preconditions for a more decisive and efficient ECB intervention, as only a recovery in price distortions should have represented a sufficient reason to stop purchasing bonds on the secondary market. By identifying the eligible countries and setting up an unlimited buying capacity, the OMTs solved the inconsistencies and ambiguities of the SMP, which did not clearly define these elements.

Through the introduction of the OMTs, the ECB recognised that the diligent implementation of austerity measures was not a sufficient condition to preserve the access to financial markets for countries under programme, and it ensured adequate liquidity in the secondary market of sovereign bonds: whatever negative impact the austerity measures implied for the economy, the ECB cleared away all doubts about a new partial default regarding an EMU country. A new “Greek case” would not have occurred. Formally, the ECB assumed the role of buyer of last resort in favour of sovereign bond holders, particularly credit institutions; however, in concrete terms, it assured the solvency of each EMU countries under programme, that is, it assumed the role of lender of last resort in favour of national governments. 25 As a result, albeit the OMTs were never implemented, the ECB succeeded in stabilizing the sovereign bonds’ price; since sovereign bonds are the main collateral used by credit institutions to access to the interbank market and refinancing operations of the Eurosystem, the banking sectors of all peripheral countries were able to satisfy their liquidity needs on better terms and the efficiency of the transmission mechanism of the monetary policy improved significantly.

4. The Need of a Lender of Last Resort

As seen in Section 2, the ECB decides and implements the monetary policy with the operational support of the national central banks of the EMU member States. Despite the clarity of the legislative provisions on how the responsibilities for taking and implementing the monetary policy decisions are allocated, some claims by Sinn and Wollmershäuser [5] (p. 478) seem to be ambiguous and misleading: “The base money flowing out of the GIIPS via international transactions was thus completely offset by the creation of new base money by the GIIPS NCBs. The central bank liquidity in the GIIPS, (…) consists of one component that arose from asset purchases, and another that resulted from net refinancing operations of the central banks with the commercial banks. However, in other Euro core countries, particularly Germany (…) there is in addition outside money that flowed in via the Target accounts. The central banks of these countries had to create this central bank money on behalf of the central banks of the GIIPS in order to fulfil their transfer orders”. From these statements it appears that the national central banks of the peripheral countries decide autonomously to create and transfer the central bank liquidity toward core countries in order to satisfy the necessities of their financial institutions. 26 On the contrary, national central banks actions essentially consist of legal obligations stemming from the measures of monetary policy decided and implemented by the ECB in its role of decision-making body of the ESBC. National central banks have to run the central bank liquidity transfer according to the requests made by credit institutions, as long as these institutions have the necessary resources and respect the necessary conditions, namely, in the context of the sovereign debt crisis, as long as the financial institutions can access the refinancing operations implemented by the Eurosystem. This is true even in the presence of the operations of Emergency Liquidity Assistance (ELA), which, while not having to be explicitly authorized by the Executive Board of the ECB, can be removed if some specific conditions arise (see Buiter et al. [35]). It can be noticed that the TARGET2 balances do not change when the Eurosystem implements refinancing operations because national central banks directly provide liquidity to their national credit institutions, they only change when these institutions use central bank liquidity for transnational payments. Thus, TARGET2 imbalances usually denote how the geographical distribution of the central bank liquidity differs compared to the original one as it is determined by refinancing operations, namely, they denote the ordinary working of a monetary union. Nevertheless, TARGET2 imbalances can also indicate that the Eurosystem is assuming the role of lender of last resort in favour of credit institutions when they reflect the implementation of the non-standard measures of monetary policy.

Given the impossibility for the national central banks to take autonomous decisions, the main discussion regards the choices the ECB took towards the financial institutions of the Euro area via the non-standard monetary policy measures. According to the core interpretation, in order to support peripheral countries, the ECB was keeping the rate of interest for the refinancing operations artificially low, by crowding out private investors that would have been available for lending financial resources at a higher interest rate. In turn, a higher interest rate should have forced a reduction in the production and in the price level; in particular, the wage rate would have decreased, giving to the peripheral countries the opportunity to gain competitiveness on international markets. These conclusions are based on the crucial hypothesis that the price system accurately reflects the economic fundamentals of each country.

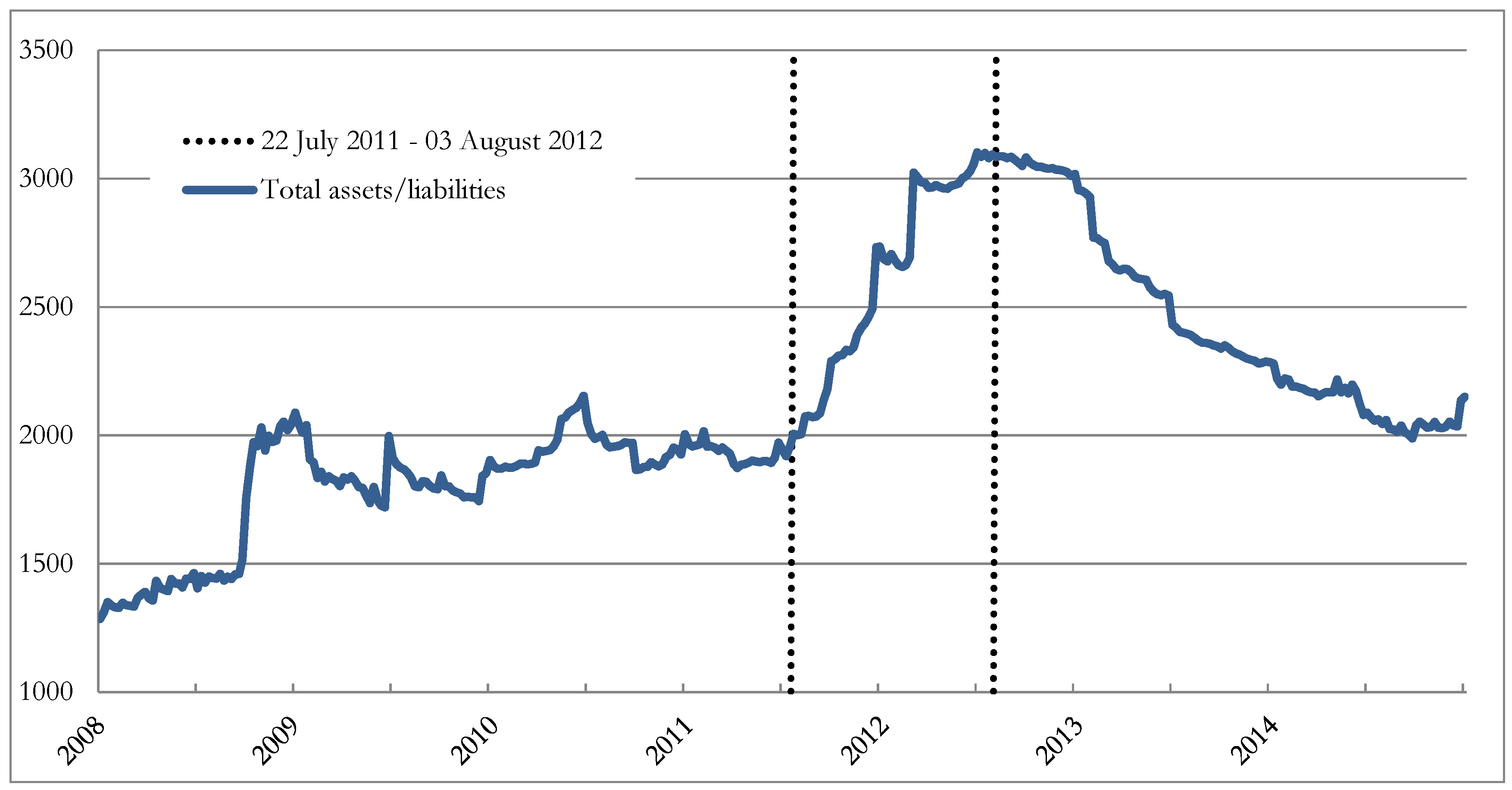

Nevertheless, it is more plausible to assume that the ECB’s strategy did not endorsed these conclusions, but it reflected the conviction that the price system was not adequately performing its role, as it is incorporating the politically unacceptable expectation of an EMU break up or, at least, of the return to the national currency of some EMU member States. The reading of the dynamics observed in TARGET2 balances, as described in the previous section, provides a clear support for this interpretation. The distortion recorded in the price system and its inability to depict the actual situation of the economic fundamentals, required, in the first place, the ECB to broadly interpret its role of lender of last resort in favour of credit institutions and, secondly, to threaten, so far so credible, to implicitly assume the same role for the benefit of the member States of the EMU. From the July 22, 2011 to August 3, 2012, the total assets of the Eurosystem increased by more than 1000.0 billion euro; in this period, the ECB undertook additional non-standard monetary policy measures, in particular, on the 21 December 2011 and 29 February 2012, two longer-term refinancing operations with a maturity of three years took place providing 1018.7 billion euro to the EMU banking sector. However, since August 2012, when the ECB implicitly assumed the role of lender of last resort in favour of the EMU member States by announcing the launch of the OMTs, the total assets began to decrease (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Consolidated financial statement of the Eurosystem (Euro billion, weekly, end of the period) Source: Elaboration on the ECB dataset (accessed on 27 June 2015, http://sdw.ecb.europa.eu/browse.do?node=bbn129).

Figure 7.

Consolidated financial statement of the Eurosystem (Euro billion, weekly, end of the period) Source: Elaboration on the ECB dataset (accessed on 27 June 2015, http://sdw.ecb.europa.eu/browse.do?node=bbn129).

In the light of these considerations, ascertaining who is responsible for paying back the TARGET2 claims accumulated by the central banks of the core countries becomes a mere theoretical exercise, which, although interesting, does nothing but fuelling concerns about the ability of the European institutions and, in particular of the EMU, to survive. The TARGET2 claims accumulated by the national central banks of the core countries on the ECB are related to the financial liabilities accumulated by these authorities with respect to their domestic financial institutions. In a symmetrical manner, the TARGET2 liabilities accumulated by the national central banks of peripheral countries to the ECB are related to the financial claims these authorities accumulated with respect to their domestic financial institutions. Therefore, the deposits accumulated by the institutions of the core countries are counterbalanced by the loans accumulated by the institutions of the peripheral countries. As far as the latter are granted, according to the set of rules laid down by the decision-making bodies of the ECB and in particular within a prudent policy management of the credit risk, it is not reasonable to create prospective scenarios based on insolvency of the ECB. In order to argue that the accumulated TARGET2 claims result into an increase in the credit risk borne by the core countries, it is necessary to prove that it is more risky to have the Eurosystem as a counterpart than any financial institution of the peripheral countries. In other words, one should prove that the lending policy of the Eurosystem is more risky than that one implemented by the institutions of the peripheral countries. 27 From our point of view the core interpretation takes implicitly this position without demonstrating it. 28

As already stressed, the action of the ECB was necessary because the price system was unable to reflect correctly the economic fundamentals, but it was also necessary because the austerity policy and the structural reform were not effective in stabilizing the economy of the countries mostly hit by the crisis. Blanchard and Leigh [37] found that a tighter planned fiscal consolidation is associated with a level of actual GDP lower that the expected one; according to the authors, this result could stem from a strong underestimation of the fiscal multiplier. A vast amount of literature supports this last conclusion; Auerbach and Gorodnichenko [38] show that the value of the multiplier tends to be higher during the recessions and lower during the expansions.

The theoretical analysis has identified several factors that could be held responsible for such a dynamic. A first explanation lies in a constant nominal rate of interest: in adopting a restrictive fiscal policy, the lower pressure on prices leads to a reduction in the nominal interest rate, stimulates the private components of the aggregate demand and mitigates the negative impact of the fiscal consolidation; however, when the nominal rate of interest is already close to zero such a mechanism cannot operate (Christiano et al. [39] and Eggertsson and Krugman [40]). Furthermore, if the adoption of a restrictive fiscal policy is coupled with a reduction in the private debt, the intensity of the recession might be such to generate a phenomenon of deflation and frustrates the efforts for stabilizing the debt made by the public administration through the fiscal consolidation and by the private sector (Eggertsson and Krugman [40]). A second explanation lies in the possible limited validity of the Ricardian equivalence: in adopting a restrictive fiscal policy, the lower expected tax burden can stimulate the private demand by limiting the negative impact of the fiscal consolidation; however, this mechanism would not operate at all if the economic agents are either characterized by a restricted time horizon or a rationed access to the credit market (Arestis [41]).

The combination of the above-mentioned elements suggests that a restrictive fiscal policy can be inappropriate, at least in the short run, to stabilize the economy, by promoting an increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio and a decrease in the inflation rate. 29 Thus, this policy appears to be highly unsuitable in the resolution of the sovereign debt crisis, especially when it is implemented in the absence of an institution acting as a lender of last resort for the benefit of the peripheral countries. The ECB took this kind of responsibility through the OMTs, following the consequence of the implicit refusal of the European institutions to create a mechanism working as lender of last resort for the Eurozone member States.

Nevertheless, the OMTs did not solve all troubles of the EMU; their introduction ensured financial markets against the risk of a new partial default regarding an EMU country but without determining a recovery in the economy. 30 Following the implementation of austerity measures, the main Euro area economies experienced a recession period and the inflation rate declined under the statutory target of the monetary policy. In January 2015, to face this situation the ECB Governing Council felt forced to launch an expanded Asset Purchase Programme that encompassed the Asset-Backed Securities Purchase Programme (ABSPP) along with the third Covered Bond Purchase Programme (CBPP3) 31 and included the purchase of sovereign bonds issued by Euro area central governments, agencies and European institutions. For the countries under programme the eligibility was conditional to the respective programmes criteria. The purchase started in March 2015 and will last, at least, until September 2016 for a monthly amount of 60.0 billion euro; hypothetical losses related to the purchases of sovereign bonds will be imputed for a 20.0 per cent to the ECB and for the remaining 80.0 per cent to the national central banks. The main reason leading the Governing Council to launch these additional programmes was that the liquidity injected into the economy through the previous non-standard measures was significantly lower than expected with the risk of triggering an intense deflationary process (ECB [44]). 32 The effect of the actions taken by the ECB is still significantly uncertain as they will be able to stimulate the demand for consumer goods and investment of households and firms only to the extent that credit institutions will be able to transform the greater liquidity available in credit to non-financial sector.

5. Conclusions

This paper argues that the dynamics of the TARGET2 balances reveal important shortfalls in the European institutions’ choices when dealing with the sovereign debt crisis rather than a balance-of payment crisis due to competitiveness disparities across Eurozone member States. In particular, these shortfalls stem from the implicit refusal to set up a mechanism or an institution to serve as a lender of last resort.

To support this thesis, the following arguments have been made: (a) before the financial crisis, the peripheral countries presented various degree of heterogeneity when compared trough different macro indicators of internal and external performance; (b) a substantial outflow of central bank liquidity was observed in the peripheral countries in coincidence with specific policy decisions taken by the European institutions, involving a sharp deterioration of expectations about both the degree of solvency of countries belonging to the Euro area and the distribution of risks of a possible partial or total default; (c) the monetary policy decided and implemented by the ECB stemmed from its legitimate and unavoidable role of lender of last resort for credit institutions to avoid liquidity crisis; (d) austerity measures destabilized the economic system in the presence of strongly negative conjuncture and a monetary policy ineffective in reducing interest rates.

These elements drew a picture that suggested the need for the creation of either an institution or a mechanism that could play the role of lender of last resort for supporting the peripheral countries. Indeed, only when the ECB took this responsibility by launching the OMTs’ clear signs of improvement were observed in the sovereign debt crisis. The dynamics of the TARGET2 system balances were determined by obvious tensions in financial markets due to a crisis of confidence in the ability of the EMU to survive; nevertheless, this crisis of confidence was not the result of a historical accident but was a direct consequence of the implicit refusal of the European institutions to create a mechanism that would serve as a lender of last resort for EMU member States.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments and suggestions.

Author Contributions

Both authors have contributed equally to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix

Table A1.

Macro indicators of internal and external performance.

| Variable | 1. Real GDP Rate of Growth | 2. Value Added Industry | 3. Value Added Construction | 4. Value Added Trade | 5. Value Added Financial Services | 6. Value Added Real Estate |

| Member State/Time | Average 1999–2007 | Average 1999–2007 | Average 1999–2007 | Average 1999–2007 | Average 1999–2007 | Average 1999–2007 |

| Germany | 1.6 | 25.6 | 4.4 | 16.3 | 4.9 | 11.2 |

| Ireland | 6.4 | 26.7 | 8.3 | 16.5 | 8.7 | 7.0 |

| Greece | 4.0 | 13.6 | 7.7 | 25.9 | 4.4 | 11.7 |

| Spain | 3.9 | 19.5 | 10.9 | 23.2 | 4.8 | 7.1 |

| Italy | 1.5 | 21.1 | 5.4 | 21.1 | 5.0 | 11.3 |

| Portugal | 1.8 | 18.9 | 7.2 | 22.5 | 6.6 | 8.2 |

| Variable | 7. Deficit/Surplus-to-GDP-ratio | 8. Debt-to-GDP ratio | 9. Debt-to-GDP ratio | 10. Debt-to-GDP ratio | ||

| Member State/Time | Average 1999–2007 | 1999 | Average 1999–2007 | Average rate of change 1999–2007 | ||

| Germany | −2.2 | 60.2 | 62.4 | 0.8 | ||

| Ireland | 1.6 | 46.7 | 31.1 | −7.9 | ||

| Greece | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Spain | 0.2 | 60.9 | 48.2 | −6.1 | ||

| Italy | −2.9 | 109.6 | 102.9 | −1.2 | ||

| Portugal | −4.3 | 51.0 | 59.6 | 3.2 | ||

| Variable | 11. Net current account | 12. Net good and services | 13. Export | 14. Import | 15. Net income | 16. Net current transfers |

| Member State/Time | Average 1999–2007 | Average 1999–2007 | Average rate of change 1999–2007 | Average rate of change 1999–2007 | Average 1999–2007 | Average 1999–2007 |

| Germany | 2.7 | 3.7 | 5.8 | 5.0 | 0.3 | −1.3 |

| Ireland | −1.6 | 13.1 | −4.6 | −3.2 | −15.1 | 0.3 |

| Greece | −7.9 | −8.1 | 4.7 | 4.0 | −2.1 | 2.3 |

| Spain | −5.5 | −3.6 | −0.1 | 2.3 | −1.8 | −0.1 |

| Italy | −0.5 | 0.6 | 1.9 | 3.7 | −0.4 | −0.6 |

| Portugal | −9.3 | −8.9 | 1.2 | 1.0 | −2.5 | 2.1 |

| Variable | 17. Net direct investment | 18. Net dividends and distributed branch profits | 19. Net reinvesting earnings and undistributed branch profits | 20. Net income on debt (interest) | 21. Net portfolio investment | 22. Net current transfer general government |

| Member State/Time | Average 1999–2007 | Average 1999–2007 | Average 1999–2007 | Average 1999–2007 | Average 1999–2007 | Average 1999–2007 |

| Ireland | −17.1 | −11.3 | −6 | 0.4 | 0.9 | −0.6 |

| Variable | 23. Net IIP | 24. Net IIP | 25. Valuation effect | 26. Sovereign bond holding, resident | 27. Sovereign bond holding, resident | 28. Sovereign bond holding, resident |

| Member State/Time | 1999 | Average 1999–2007 | Average 1999–2007 | 1999 | 2007 | Average 1999–2007 |

| Germany | 4.4 | 12.3 | 0.3 | 65% | 53% | 60% |

| Ireland | 49.4 | −8.3 | −4.5 | 45% | 10% | 25% |

| Greece | −29.3 | −59.2 | −4.9 | 66% | 29% | 51% |

| Spain | −31.3 | −47.5 | −3.9 | 69% | 50% | 55% |

| Italy | −4.8 | −13.7 | −3.2 | 68% | 51% | 58% |

| Portugal | −31.2 | −57.6 | −0.9 | 46% | 24% | 32% |

Note: 1. Gross Domestic Product at 2010 reference level, annual percentage change, source: European Commission AMECO database (code OVGD); 2–6. Gross Value Added by industry breakdown, percentage of total, source: Eurostat (code nama_10_a10); 7. General Government deficit/surplus in percentage of GDP, source: Eurostat (code gov_10dd_edpt1) used for the macro imbalance procedure of the European Commission; 8–10. General Government gross debt consolidated in percentage of GDP, source: Eurostat (code tipso10) used for the macro imbalance procedure of the European Commission; 11–16. BOP current account and its main component towards the rest of the world, expressed in net terms (with the exception of import and exports) and in percentage of GDP, source: Eurostat (code bop_q_c); 17–22. BOP income and current transfers subcomponents towards the rest of the world, expressed in net terms and in percentage of GDP, source: Eurostat (code bop_q_c); 23–24. Net International Investment Position towards the rest of the world, expressed in percentage of GDP, source: Eurostat (code bop_ext_intpos); 25. Valuation effect of the changes (y-o-y) in net International Investment Position expressed as percentage of GDP, source: authors’ calculations on Eurostat data (code bop_ext_intpos); 26–28. Sovereign bond held by resident expressed as percentage of the total, source: “Bruegel dataset on sovereign bond holdings”. All the variables expressed as percentage of GDP are calculated on the basis of the GDP, source: Eurostat nama_10_gdp.

References

- European Central Bank (ECB). “The TARGET2 System.” In Target Annual Report 2011. Frankfurt, Germany: European Central Bank (ECB), 2012, pp. 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- P. Cour-Thimann. CESifo Forum Special Issue April 2013: Target Balances and the Crisis in the Euro Area. Munich, Germany: CESifo Forum, Center for Economic Studies and Ifo Institute (CESifo), 2013, Volume 14, pp. 5–50. [Google Scholar]

- H.-W. Sinn, and T. Wollmershäuser. Target Loans, Current Account Balances and Capital Flows: The ECB’s Rescue Facility. CESifo Working Paper No. 3500; Munich, Germany: Center for Economic Studies and Ifo Institute (CESifo), 2011. [Google Scholar]

- H.-W. Sinn, and T. Wollmershäuser. TARGET2 Balances and the German Financial Account in Light of the European Balance-of-Payment Crisis. CESifo Working Papers No. 4051; Munich, Germany: Center for Economic Studies and Ifo Institute (CESifo), 2012. [Google Scholar]

- H.-W. Sinn, and T. Wollmershäuser. “Target loans, current account balances and capital flows: The ECB’s rescue facility.” Int. Tax Public Financ. 19 (2012): 468–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Cesaratto. “Balance of Payments or Monetary Sovereignty? In Search of the EMU’s Original Sin—A Reply to Lavoie.” Int. J. Political Econ. 44 (2015): 142–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Panico, and F. Purificato. “Policy coordination, conflicting national interests and the European debt crisis.” Camb. J. Econ. 37 (2013): 585–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Central Bank (ECB). “TARGET2 balances of national central banks in the Euro area.” Mon. Bull. 10 (2011): 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- European Central Bank (ECB). “The TARGET2 balances of national central banks (NCBs).” In TARGET2 Annual Report 2011. Frankfurt, Germany: European Central Bank (ECB), 2012, pp. 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- European Central Bank (ECB). “TARGET Balances and Monetary Policy Operations.” Mon. Bull. 5 (2013): 103–114. [Google Scholar]

- P. De Grauwe, and Y. Ji. What Germany Should Fear Most Is Its Own Fear. An analysis of TARGET2 and Current Account Imbalances. CEPS Working Paper No. 386; London, UK: Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR), 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsche Bundesbank. “The dynamics of the Bundesbank’s TARGET2 balance.” Mon. Rep. 63 (2011): 34–35. [Google Scholar]

- M. Lavoie. “The Eurozone: Similarities to and Differences from Keynes’s Plan.” Int. J. Political Econ. 44 (2015): 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Central Bank (ECB). “Verbatim of the remarks made by Mario Draghi: Speech by Mario Draghi, President of the European Central Bank at the Global Investment Conference in London, 26 July 2012.” Available online: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2012/html/sp120726.en.html (accessed on 26 June 2015).

- European Central Bank (ECB). “Editorial.” Mon. Bull. 8 (2012): 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- U. Bindseil, and P.J. König. The Economics of TARGET2 Balances. SFB 649 Discussion Paper 2011-035; Frankfurt, Germany: European Central Bank (ECB), 2011. [Google Scholar]

- K. Whelan. “TARGET2 and central bank balance sheets.” Econ. Policy 29 (2014): 79–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Cecioni, and G. Ferrero. “Determinants of TARGET2 imbalances.” In Questioni di Economia e Finanza Banca d’Italia No. 136. Roma, Italy: Bank of Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- R.A. Auer. “What drives TARGET2 balances? Evidence from a panel analysis.” Econ. Policy 29 (2014): 139–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Merler, and J. Pisani-Ferry. “Sudden Stops in the Euro Area.” Available online: http://bruegel.org/wp-content/uploads/imported/publications/pc_2012_06.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2015).

- W.H. Buiter, and E. Rahbari. “The European Central Bank as Lender of Last Resort for Sovereigns in the Eurozone.” J. Common Mark. Stud. 50 (2012): 6–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. De Grauwe. “The European Central Bank as Lender of Last Resort in the Government Bond Markets.” CESifo Econ. Stud. 59 (2013): 520–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Central Bank (ECB). The Implementation of Monetary Policy in the Euro Area. General Documentation on Eurosystem Monetary Policy Instruments and Procedures, Overview on the Monetary Policy Framework. Frankfurt, Germany: European Central Bank (ECB), 2011, pp. 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- K. Hu. “The Institutional Innovation of the Lender of Last Resort Facility in the Eurozone.” J. Eur. Integr. 36 (2014): 627–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Micossi. “The Monetary Policy of the European Central Bank (2002–2015).” In CEPS Special Report. Brussel, Belgium: Centre for European Policy Studies, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- N. Holinski, C.J. Kool, and J. Muysken. “Persistent macroeconomic imbalances in the euro area: Causes and consequences.” Fed. Reserv. Bank St. Louis Rev. 94 (2012): 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Council of the European Union. “Statement by the Head of State or Government of the Euro Area and EU Institutions.” 21 July 2011. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/ec/123978.pdf (accessed on 27 June 2015).

- European Central Bank (ECB). “Introductory statement to the press conference (with Q&A).” 7 July 2011. Available online: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pressconf/2011/html/is110707.en.html (accessed on 27 June 2015).

- European Central Bank (ECB). “Introductory statement to the press conference (with Q&A).” 4 August 2011. Available online: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pressconf/2011/html/is110804.en.html (accessed on 27 June 2015).

- European Central Bank (ECB). “Monetary and fiscal policy interactions in a monetary union.” Mon. Bull. 6 (2012): 51–64. [Google Scholar]

- Eurogroup. “Statement of the Eurogroup.” 30 March 2012. Available online: http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/ecofin/129381.pdf (accessed on 27 June 2015).

- Council of the European Union. “Agreed lines of communication by Euro area Member States.” 30 January 2012. Available online: http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/ec/127633.pdf (accessed on 27 June 2015).

- European Central Bank (ECB). “Introductory statement to the press conference (with Q&A).” 2 August 2012. Available online: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pressconf/2012/html/is120802.en.html (accessed on 27 June 2015).