Review of Family Business Definitions: Cluster Approach and Implications of Heterogeneous Application for Family Business Research

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Objective and Research Questions

Which existing definitions have family business researchers mainly applied in their studies to date and how can these definitional approaches be clustered?

Why have family business researchers not found a consensus on a single, commonly accepted definition which can be applied in family business studies?

3. Literature Review

“A company is considered a family business when it has been closely identified with at least two generations of a family and when this link has had a mutual influence on company policy and on the interests and objectives of the family.”[17] (p. 94)

“[...] the definition of a family business must be based on what researchers understand to be the differences between the family and nonfamily businesses.”[28] (p. 557)

“Our search confirmed this [a lack of consensus as to how to operationalize family involvement; author’s note] as we identified over thirty definitions of family involvement across included studies. These articles used between one and eight criteria to determine the family involvement of a firm.”[29] (p. 8)

4. Methods

4.1. Selection of Journals and Articles

4.2. Development of Clusters for Analytical Approach

5. Clustering Approach

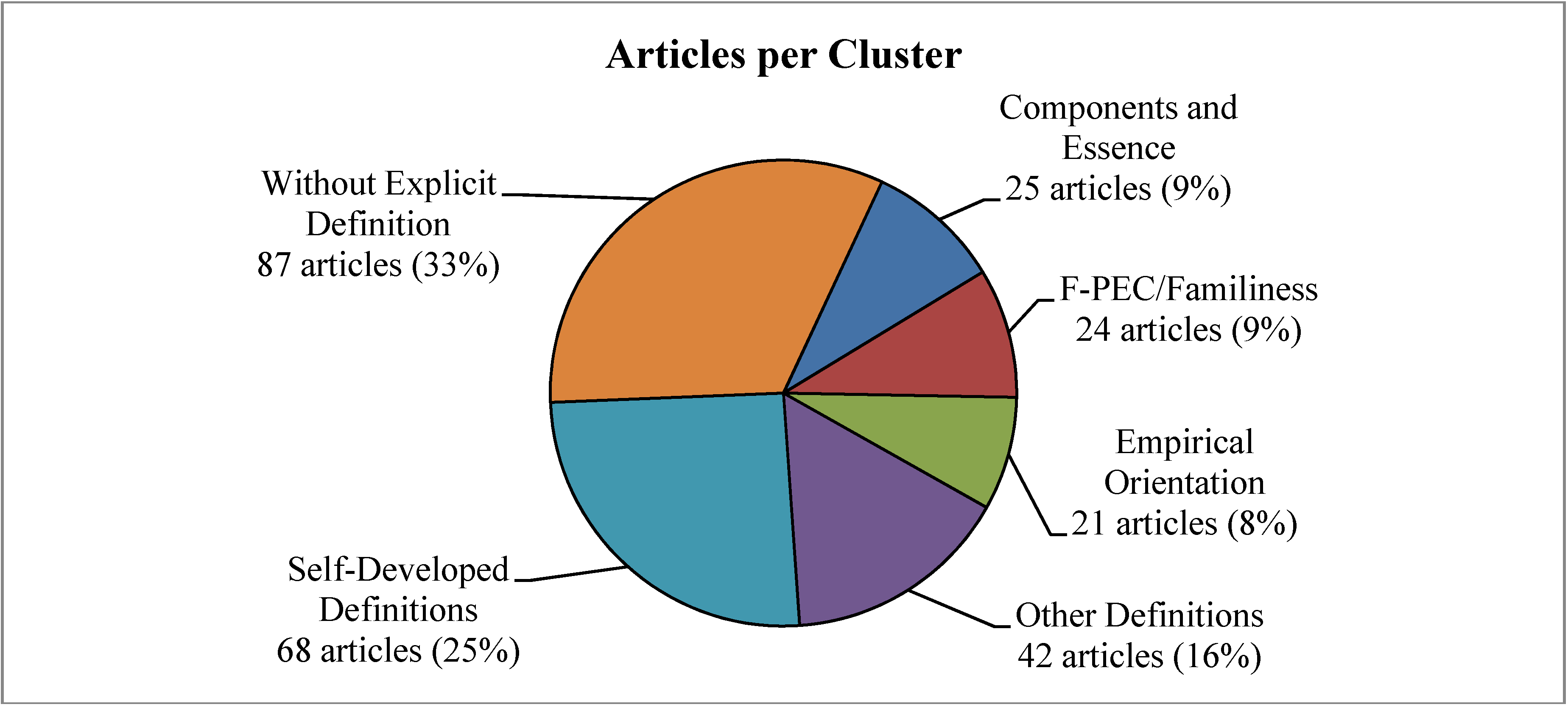

5.1. Cluster 1: Components of Involvement Approach and Essence Approach

“…a business governed and/or managed with the intention to shape and pursue the vision of the business held by a dominant coalition controlled by members of the same family or a small number of families in a manner that is potentially sustainable across generations of the family or families.”[33] (p. 25)

“We call these human processes the ‘politics of value determination’ in family firms. This concept is entirely consistent with the two concepts of transgenerational intentionality and the familial coalition’s vision that was used by Chua et al. (1999) to develop a theoretical definition of family firms and the systems perspective proposed by Habbershon et al. 2003 [37].”[36] (p. 470)

5.2. Cluster 2: F-PEC Scale/Familiness

5.3. Cluster 3: Definitions with Empirical Orientation

5.4. Cluster 4: Application of other Definitions

5.5. Cluster 5: Self-Developed Definitional Approaches

“[…] attempts to define a family firm or to delineate between the performance requirements of so-called family firms and nonfamily firms have left family business leaders confused at best.”[37] (p. 452)

5.6. Cluster 6: Without Explicit Definition

6. Evaluation and Discussion of Results

6.1. Results over All 267 Articles

6.2. Results with Focus on Individual Clusters

6.3. Summary of Findings with Respect to Definitional Heterogeneity

“[…] a consensus definition may not represent a pertinent research goal because, by nature, FBs are contingent on the institutional legal context, which differs from country to country.”[66] (p. 316)

“Although the field recognizes that different types of families exist, not much has been done to determine which differences really matter […] Do not assume that what was a problem for one family business will be so in another [...].”[74] (p. 18)

7. Conclusions

7.1. Summary

7.2. Contribution to Theory and Practice

“[…] some studies likely included firms in their ‘family firm’ sample that would not have been included in other studies’ samples and this mixing of ‘apples and oranges’ might account for the ambiguous findings.”[56] (p. 254)

7.3. Limitations

7.4. Recommendations and Implications for Future Research

Appendix A

| Definitional Cluster | In… | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | Aggregate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Journal Articles | absolutes | 25 | 24 | 21 | 42 | 68 | 87 | 267 |

| % | 9.36% | 8.99% | 7.87% | 15.73% | 25.47% | 32.58% | 100.00% | |

| Year | absolutes | 25 | 24 | 21 | 42 | 68 | 87 | 267 |

| % | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | |

| until 2000 | absolutes | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 11 | 18 | 33 |

| % | 4.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 7.14% | 16.18% | 20.69% | 12.36% | |

| 2001–2005 | absolutes | 4 | 7 | 2 | 7 | 14 | 25 | 59 |

| % | 16.00% | 29.17% | 9.52% | 16.67% | 20.59% | 28.74% | 22.10% | |

| 2006–2010 | absolutes | 12 | 12 | 11 | 23 | 33 | 28 | 119 |

| % | 48.00% | 50.00% | 52.38% | 54.76% | 48.53% | 32.18% | 44.57% | |

| from 2011 | absolutes | 8 | 5 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 16 | 56 |

| % | 32.00% | 20.83% | 38.10% | 21.43% | 14.71% | 18.39% | 20.97% | |

| Journal | absolutes | 25 | 24 | 21 | 42 | 68 | 87 | 267 |

| % | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | |

| ETP | absolutes | 8 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 10 | 25 |

| % | 32.00% | 16.67% | 0.00% | 2.38% | 2.94% | 11.49% | 9.36% | |

| FBR | absolutes | 5 | 5 | 0 | 18 | 29 | 31 | 88 |

| % | 20.00% | 20.83% | 0.00% | 42.86% | 42.65% | 35.63% | 32.96% | |

| JSBM | absolutes | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 11 |

| % | 8.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 4.76% | 4.41% | 4.60% | 4.12% | |

| JBR | absolutes | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 12 |

| % | 8.00% | 0.00% | 4.76% | 2.38% | 2.94% | 6.90% | 4.49% | |

| JBV | absolutes | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 10 |

| % | 4.00% | 8.33% | 0.00% | 2.38% | 4.41% | 3.45% | 3.75% | |

| JFBS | absolutes | 4 | 7 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 24 |

| % | 16.00% | 29.17% | 4.76% | 9.52% | 5.88% | 4.60% | 8.99% | |

| Others | absolutes | 3 | 6 | 19 | 15 | 25 | 29 | 97 |

| % | 12.00% | 25.00% | 90.48% | 35.71% | 36.76% | 33.33% | 36.33% | |

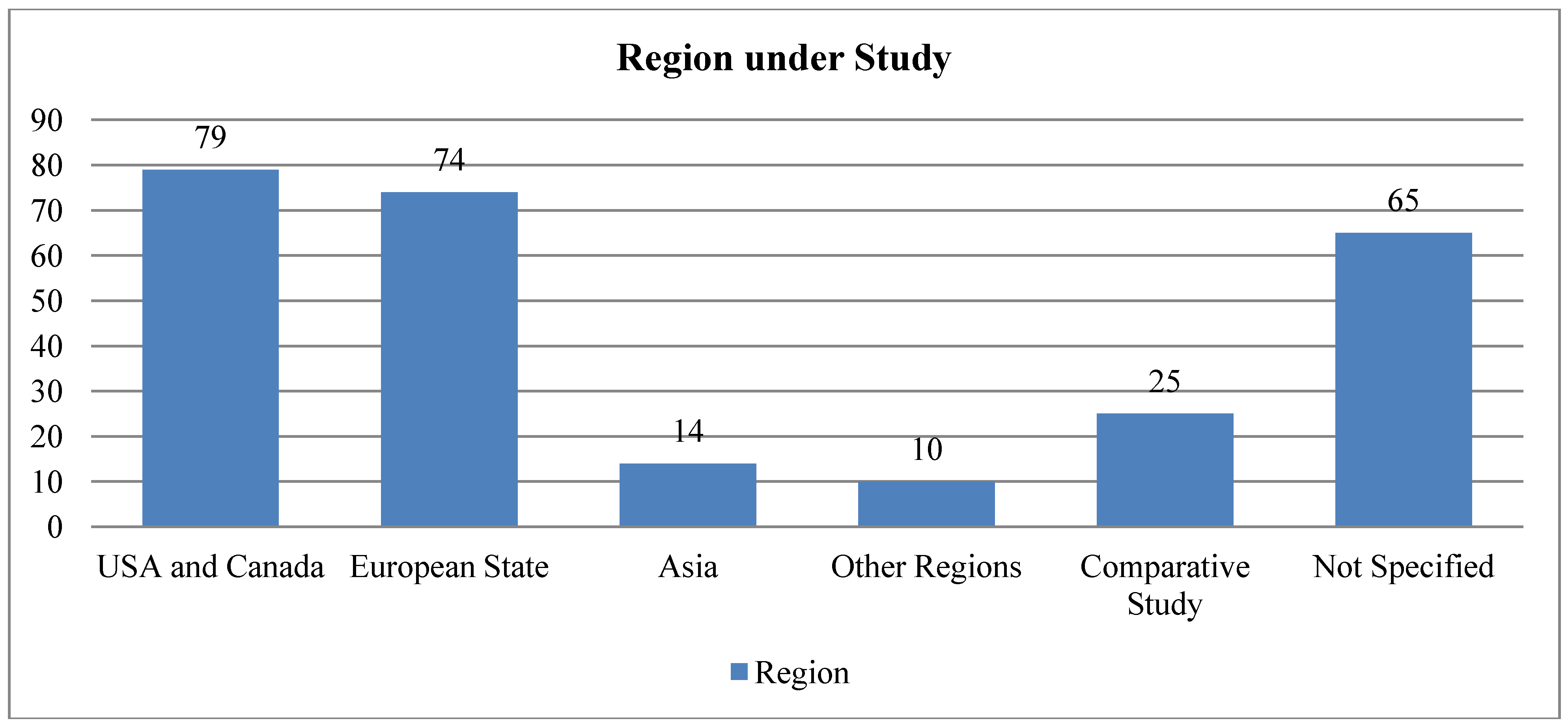

| Region | absolutes | 25 | 24 | 21 | 42 | 68 | 87 | 267 |

| % | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | |

| USA and Canada | absolutes | 14 | 3 | 16 | 11 | 15 | 20 | 79 |

| % | 56.00% | 12.50% | 76.19% | 26.19% | 22.06% | 22.99% | 29.59% | |

| European State | absolutes | 3 | 6 | 3 | 14 | 29 | 19 | 74 |

| % | 12.00% | 25.00% | 14.29% | 33.33% | 42.65% | 21.84% | 27.72% | |

| Asia | absolutes | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 14 |

| % | 8.00% | 0.00% | 9.52% | 9.52% | 4.41% | 3.45% | 5.24% | |

| Other Regions | absolutes | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 10 |

| % | 0.00% | 4.17% | 0.00% | 2.38% | 5.88% | 4.60% | 3.75% | |

| Comparative Study | absolutes | 0 | 2 | 0 | 8 | 6 | 9 | 25 |

| % | 0.00% | 8.33% | 0.00% | 19.05% | 8.82% | 10.34% | 9.36% | |

| Not Specified | absolutes | 6 | 12 | 0 | 4 | 11 | 32 | 65 |

| % | 24.00% | 50.00% | 0.00% | 9.52% | 16.18% | 36.78% | 24.34% | |

| Type | absolutes | 25 | 24 | 21 | 42 | 68 | 87 | 267 |

| % | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | |

| Theoretical/Conceptual Approach (incl. Reviews) | absolutes | 9 | 12 | 0 | 5 | 15 | 35 | 76 |

| % | 36.00% | 50.00% | 0.00% | 11.90% | 22.06% | 40.23% | 28.46% | |

| Empirical Approach | absolutes | 16 | 12 | 21 | 37 | 53 | 52 | 191 |

| % | 64.00% | 50.00% | 100.00% | 88.10% | 77.94% | 59.77% | 71.54% | |

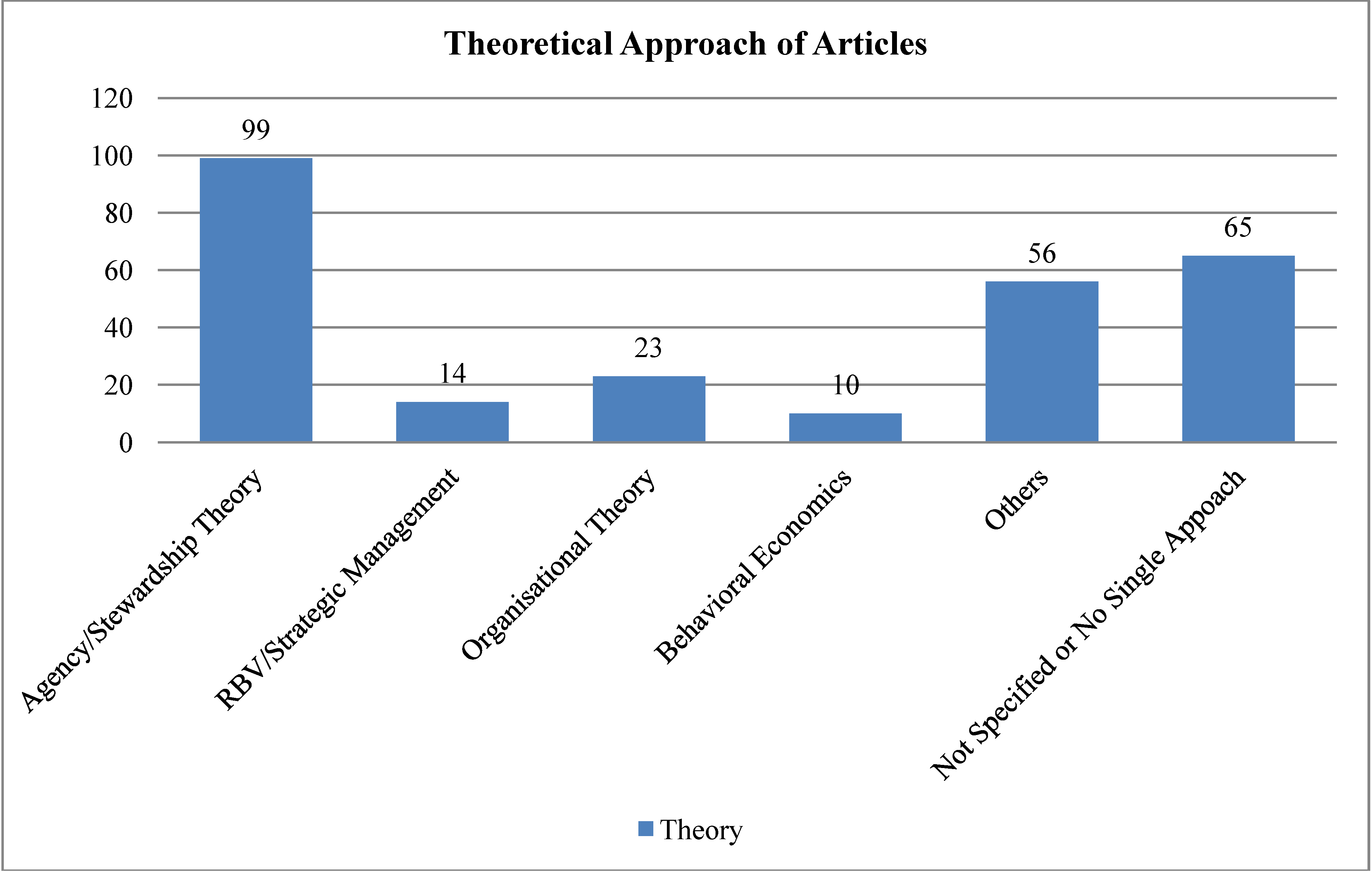

| Theory | absolutes | 25 | 24 | 21 | 42 | 68 | 87 | 267 |

| % | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | |

| Agency/Stewardship Theory | absolutes | 8 | 3 | 15 | 19 | 27 | 27 | 99 |

| % | 32.00% | 12.50% | 71.43% | 45.24% | 39.71% | 31.03% | 37.08% | |

| RBV/Strategic Management | absolutes | 4 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 14 |

| % | 16.00% | 20.83% | 0.00% | 4.76% | 2.94% | 1.15% | 5.24% | |

| Organizational Theory | absolutes | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 23 |

| % | 16.00% | 12.50% | 14.29% | 7.14% | 7.35% | 5.75% | 8.61% | |

| Behavioral Economics | absolutes | 2 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 10 |

| % | 8.00% | 8.33% | 0.00% | 7.14% | 2.94% | 1.15% | 3.75% | |

| Others | absolutes | 4 | 8 | 1 | 7 | 17 | 19 | 56 |

| % | 16.00% | 33.33% | 4.76% | 16.67% | 25.00% | 21.84% | 20.97% | |

| Not Specified or No Single Approach | absolutes | 3 | 3 | 2 | 8 | 15 | 34 | 65 |

| % | 12.00% | 12.50% | 9.52% | 19.05% | 22.06% | 39.08% | 24.34% | |

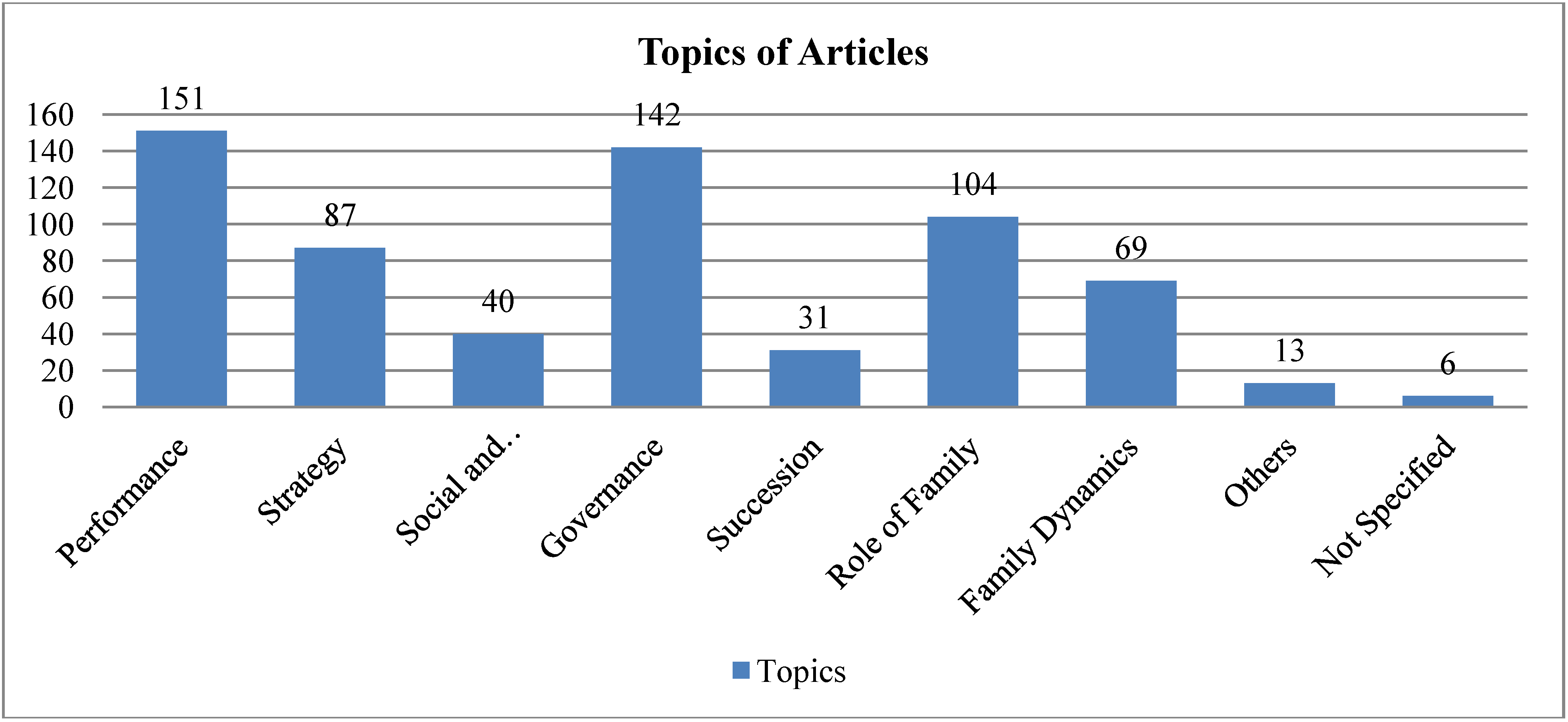

| Topic | absolutes | 65 | 69 | 45 | 102 | 171 | 191 | 643 |

| % | 260.00% | 287.50% | 214.29% | 242.86% | 251.47% | 219.54% | 240.82% | |

| Performance | absolutes | 17 | 17 | 15 | 27 | 41 | 34 | 151 |

| % | 68.00% | 70.83% | 71.43% | 64.29% | 60.29% | 39.08% | 56.55% | |

| Strategy | absolutes | 13 | 4 | 7 | 17 | 26 | 20 | 87 |

| % | 52.00% | 16.67% | 33.33% | 40.48% | 38.24% | 22.99% | 32.58% | |

| Social and Economic Impact | absolutes | 3 | 3 | 0 | 10 | 11 | 13 | 40 |

| % | 12.00% | 12.50% | 0.00% | 23.81% | 16.18% | 14.94% | 14.98% | |

| Governance | absolutes | 11 | 9 | 18 | 24 | 39 | 41 | 142 |

| % | 44.00% | 37.50% | 85.71% | 57.14% | 57.35% | 47.13% | 53.18% | |

| Succession | absolutes | 3 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 9 | 13 | 31 |

| % | 12.00% | 8.33% | 0.00% | 9.52% | 13.24% | 14.94% | 11.61% | |

| Role of Family | absolutes | 11 | 19 | 5 | 12 | 27 | 30 | 104 |

| % | 44.00% | 79.17% | 23.81% | 28.57% | 39.71% | 34.48% | 38.95% | |

| Family Dynamics | absolutes | 7 | 14 | 0 | 8 | 14 | 26 | 69 |

| % | 28.00% | 58.33% | 0.00% | 19.05% | 20.59% | 29.89% | 25.84% | |

| Others | absolutes | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 9 | 13 |

| % | 0.00% | 4.17% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 4.41% | 10.34% | 4.87% | |

| Not Specified | absolutes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 6 |

| % | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 1.47% | 5.75% | 2.25% | |

| Values of single clusters 1-6 larger than value for aggregate sample | ||||||||

Appendix B

| No. | Journal | No. of Articles | % of Sample | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Family Business Review | 88 | 32.96% | |

| 2 | Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice | 25 | 9.36% | |

| 3 | Journal of Family Business Strategy | 24 | 8.99% | |

| 4 | Journal of Business Research | 12 | 4.49% | |

| 5 | Journal of Small Business Management | 11 | 4.12% | |

| 6 | Journal of Business Venturing | 10 | 3.75% | |

| 7 | Journal of Management Studies | 7 | 2.62% | |

| 8 | Betriebswirtschaftliche Forschung und Praxis | 6 | 2.25% | |

| 9 | Entrepreneurship and Regional Development | 6 | 2.25% | |

| 10 | Journal of Family Business Management | 6 | 2.25% | |

| 11 | Academy of Management Journal | 5 | 1.87% | |

| 12 | Journal of Corporate Finance | 4 | 1.50% | |

| 13 | Journal of International Business Studies | 4 | 1.50% | |

| 14 | Journal of Accounting Research | 3 | 1.12% | |

| 15 | Journal of Banking and Finance | 3 | 1.12% | |

| 16 | Journal of Economic Perspectives | 3 | 1.12% | |

| 17 | Organization Science | 3 | 1.12% | |

| 18 | Review of Financial Studies | 3 | 1.12% | |

| 19 | Small Business Economics | 3 | 1.12% | |

| 20 | The Journal of Finance | 3 | 1.12% | |

| 21 | American Economic Review | 2 | 0.75% | |

| 22 | Asia Pacific Journal of Management | 2 | 0.75% | |

| 23 | Journal of Accounting and Economics | 2 | 0.75% | |

| 24 | Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis | 2 | 0.75% | |

| 25 | Journal of Financial Economics | 2 | 0.75% | |

| 26 | Journal of Management and Governance | 2 | 0.75% | |

| 27 | Managerial and Decision Economics | 2 | 0.75% | |

| 28 | Strategic Management Journal | 2 | 0.75% | |

| 29 | Zeitschrift für KMU und Entrepreneurship | 2 | 0.75% | |

| 30 | Academy of Management Review | 1 | 0.37% | |

| 31 | Accounting. Organizations and Society | 1 | 0.37% | |

| 32 | Administrative Science Quarterly | 1 | 0.37% | |

| 33 | Asia-Pacific Journal of Financial Studies | 1 | 0.37% | |

| 34 | Corporate Governance: An International Review | 1 | 0.37% | |

| 35 | European Finance Review | 1 | 0.37% | |

| 36 | European Financial Management | 1 | 0.37% | |

| 37 | European Management Review | 1 | 0.37% | |

| 38 | Financial Markets and Portfolio Management | 1 | 0.37% | |

| 39 | Finanz Betrieb | 1 | 0.37% | |

| 40 | International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business | 1 | 0.37% | |

| 41 | International Journal of Production Research | 1 | 0.37% | |

| 42 | Journal of Business Ethics | 1 | 0.37% | |

| 43 | Journal of Business Finance and Accounting | 1 | 0.37% | |

| 44 | Journal of Enterprising Culture | 1 | 0.37% | |

| 45 | Journal of International Financial Management and Accounting | 1 | 0.37% | |

| 46 | Journal of the European Economic Association | 1 | 0.37% | |

| 47 | Management and Accounting Research | 1 | 0.37% | |

| 48 | Review of Finance | 1 | 0.37% | |

| 49 | Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal | 1 | 0.37% | |

| Sum | 267 | 100.00% | ||

Conflicts of Interest

References 11

- G. Kayser, and F. Wallau. “Industrial family businesses in Germany-situation and future.” Fam. Bus. Rev. 15 (2002): 111–115. [Google Scholar]

- J.J. Chrisman, J.H. Chua, and R.A. Litz. “Comparing the agency costs of family and non-family firms: Conceptual issues and exploratory evidence.” Entrep. Theory Pract. 28 (2004): 335–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Sharma, J.J. Chrisman, and K.E. Gersick. “25 years of family business review: Reflections on the past and perspectives for the future.” Fam. Bus. Rev. 25 (2012): 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Chittoor, and R. Das. “Professionalization of management and succession performance? A Vital Linkage.” Fam. Bus. Rev. 20 (2007): 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J.J. Chrisman, F.W. Kellermanns, K.C. Chan, and K. Liano. “Intellectual foundations of current research in family business: An identification and review of 25 influential articles.” Fam. Bus. Rev. 23 (2010): 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J.-F. Siebels, and D. zu Knyphausen-Aufsess. “A review of theory in family business research: The implications for corporate governance.” Int. J. Manag. Rev. 14 (2012): 280–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M.W. Rutherford, D.F. Kuratko, and D.T. Holt. “Examining the link between “familiness” and performance: Can the F-PEC untangle the family business theory jungle? ” Entrep. Theory Pract. 32 (2008): 1089–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Sacristán-Navarro, S. Gómez-Ansón, and L. Cabeza-García. “Large shareholders’ combinations in family firms: Prevalence and performance effects.” J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2 (2011): 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J.H. Astrachan, and T. Zellweger. “Performance of family firms: A literature review and guidance for future research.” ZfKE 56 (2008): 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- H. Frank, M. Lueger, L. Nosé, and D. Suchy. “The concept of “Familiness”.” J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 1 (2010): 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T.J. Pukall, and A. Calabro. “The internationalization of family firms: A critical review and integrative model.” Fam. Bus. Rev. 26 (2013): 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Mazzi. “Family business and financial performance: Current state of knowledge and future research challenges.” J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2 (2011): 166–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Bhattacherjee. Social Science Research: Principles, Methods, and Practices, 2nd ed. Tampa, Florida, FL, USA: Createspace, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- J.C. Dekker, N. Lybaert, T. Steijvers, B. Depaire, and R. Mercken. “Family firm types based on the professionalization construct: Exploratory research.” Fam. Bus. Rev. 26 (2013): 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Sharma. “An overview of the field of family business studies: Current status and directions for the future.” Fam. Bus. Rev. 17 (2004): 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R.G. Donnelley. “The family business.” Harv. Bus. Rev. 42 (1964): 93–105. [Google Scholar]

- R.K. Zachary. “The importance of the family system in family business.” J. Fam. Bus. Manag. 1 (2011): 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W.C. Handler. “Methodological issues and considerations in studying family businesses.” Fam. Bus. Rev. 2 (1989): 257–276. [Google Scholar]

- I. Lansberg, E.L. Perrow, and S. Rogolsky. “Editors’ notes.” Fam. Bus. Rev. 1 (1988): 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- A. Yu, G.T. Lumpkin, R.L. Sorenson, and K.H. Brigham. “The landscape of family business outcomes: A summary and numerical taxonomy of dependent variables.” Fam. Bus. Rev. 25 (2012): 33–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R.A. Litz. “The family business: Toward definitional clarity.” Fam. Bus. Rev. 8 (1995): 71–81. [Google Scholar]

- M.S. Wortman. “Theoretical foundations for family-owned business: A conceptual and research-based paradigm.” Fam. Bus. Rev. 7 (1994): 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- M.C. Shanker, and J.H. Astrachan. “Myths and realities: Family businesses’ contribution to the US economy-a framework for assessing family business statistics.” Fam. Bus. Rev. 9 (1996): 107–123. [Google Scholar]

- K.E. Gersick, J.A. Davis, M.M. Hampton, and I. Lansberg. Generation to Generation: Life Cycles of the Family Business. Boston, Massachusetts, MA, USA: Harvard Business School Press, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- R.A. Wall. “An empirical investigation of the production function of the family firm.” J. Small Bus. Manag. 36 (1998): 24–32. [Google Scholar]

- P. Westhead, and M. Cowling. “Family firm research: Need for a methodological rethink.” Entrep. Theory Pract. 22 (1998): 31–56. [Google Scholar]

- C.M. Daily, and M.J. Dollinger. “An empirical examination of ownership structure in family and professionally managed firms.” Fam. Bus. Rev. 5 (1992): 117–136. [Google Scholar]

- J.J. Chrisman, J.H. Chua, and P. Sharma. “Trends and directions in the development of a strategic management theory of the family firm.” Entrep. Theory Pract. 29 (2005): 555–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E.H. O’Boyle, J.M. Pollack, and M.W. Rutherford. “Exploring the relation between family involvement and firms’ financial performance: A meta-analysis of main and moderator effects.” J. Bus. Ventur. 27 (2012): 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Kraus, M. Filser, T. Götzen, and R. Harms. “Familienunternehmen—Zum State-of-the-Art der betriebswirtschaftlichen Forschung.” Betr. Forsch. Prax. 63 (2011): 587–605. [Google Scholar]

- P. Sharma, and M. Carney. “Value creation and performance in private family firms: Measurement and methodological issues.” Fam. Bus. Rev. 25 (2012): 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U. Schrader, and T. Hennig-Thurau. “VHB-JOURQUAL2: Method, results, and implications of the german academic association for business research’s journal ranking.” Bus. Res. 2 (2009): 180–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J.H. Chua, J.J. Chrisman, and P. Sharma. “Defining the family business by behavior.” Entrep. Theory Pract. 23 (1999): 19–39. [Google Scholar]

- M.K. Fiegener. “Locus of ownership and family involvement in small private firms.” J. Manag. Stud. 47 (2010): 296–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D.B. Audretsch, M. Hülsbeck, and E.E. Lehmann. “The benefits of family ownership, control and management on financial performance of firms.” Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1690963 (accessed on 27 April 2014).

- J.J. Chrisman, J.H. Chua, and R. Litz. “A unified systems perspective of family firm performance: An extension and integration.” J. Bus. Ventur. 18 (2003): 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T.G. Habbershon, M. Williams, and I.C. MacMillan. “A unified systems perspective of family firm performance.” J. Bus. Ventur. 18 (2003): 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Marchisio, P. Mazzola, S. Sciascia, M. Miles, and J.H. Astrachan. “Corporate venturing in family business: The effects on the family and its members.” Entrep. Reg. Dev. 22 (2010): 349–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G.T. Lumpkin, W. Martin, and M. Vaughn. “Family orientation: Individual-Level influences on family firm outcomes.” Fam. Bus. Rev. 21 (2008): 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D.G. Sirmon, J.-L. Arregle, M.A. Hitt, and J.W. Webb. “The role of family influence in firms’ strategic responses to threat of imitation.” Entrep. Theory Pract. 32 (2008): 979–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Basco, and M.J. Pérez Rodríguez. “Ideal types of family business management: Horizontal fit between family and business decisions and the relationship with family business performance.” J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2 (2011): 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G.T. Lumpkin, and K.H. Brigham. “Long-Term orientation and intertemporal choice in family firms.” Entrep. Theory Pract. 35 (2011): 1149–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L.M. Uhlaner. “The use of the guttman scale in development of a family orientation index for small-to-medium-sized firms.” Fam. Bus. Rev. 18 (2005): 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Å. Björnberg, and N. Nicholson. “The family climate scales? development of a new measure for use in family business research.” Fam. Bus. Rev. 20 (2007): 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J.H. Astrachan, S.B. Klein, and K.X. Smyrnios. “The F-PEC scale of family influence: A proposal for solving the family business definition problem.” Fam. Bus. Rev. 15 (2002): 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- T.G. Habbershon, and M.L. Williams. “A resource-based framework for assessing the strategic advantages of family firms.” Fam. Bus. Rev. 12 (1999): 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- S.M. Danes, J.T.-C. Loy, and K. Stafford. “Business planning practices of family-owned firms within a quality framework.” J. Small Bus. Manag. 46 (2008): 395–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S.B. Klein, J.H. Astrachan, and K.X. Smyrnios. “The F-PEC scale of family influence: Construction, validation, and further implication for theory.” Entrep. Theory Pract. 29 (2005): 321–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R.C. Anderson, and D.M. Reeb. “Founding-Family ownership and firm performance: Evidence from the S&P 500.” J. Financ. 58 (2003): 1301–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B. Villalonga, and R. Amit. “How do family ownership, control and management affect firm value? ” J. Financ. Econ. 80 (2006): 385–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y.-H. Nam, and J.I. Herbert. “Characteristics and key success factors in family business: The case of korean immigrant businesses in Metro-Atlanta.” Fam. Bus. Rev. 12 (1999): 341–352. [Google Scholar]

- D.L. McConaughy. “Family CEOs vs. nonfamily CEOs in the family-controlled firm: An examination of the level and sensitivity of pay to performance.” Fam. Bus. Rev. 13 (2000): 121–131. [Google Scholar]

- P.S. Davis, and P.D. Harveston. “Internationalization and organizational growth: The impact of internet usage and technology involvement among entrepreneurled family businesses.” Fam. Bus. Rev. 13 (2000): 107–120. [Google Scholar]

- S.M. Danes, K. Stafford, and J.T.-C. Loy. “Family business performance: The effects of gender and management.” J. Bus. Res. 60 (2007): 1058–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R.K.Z. Heck, and E.S. Trent. “The prevalence of family business from a household sample.” Fam. Bus. Rev. 12 (1999): 209–224. [Google Scholar]

- W.G. Dyer. “Examining the “family effect” on firm performance.” Fam. Bus. Rev. 19 (2006): 253–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Westhead, and C. Howorth. ““Types” of private family firms: An exploratory conceptual and empirical analysis.” Entrep. Reg. Dev. 19 (2007): 405–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. May, and A. Koeberle-Schmid. “Die drei dimensionen eines Familienunternehmens: Teil I.” Betr. Forsch. Prax. 63 (2011): 656–672. [Google Scholar]

- I.E. McCann, A.Y. Leon-Guerrero, and J.D. Haley Jr. “Strategic goals and practices of innovative family businesses.” J. Small Bus. Manag. 39 (2001): 50–59. [Google Scholar]

- S. King. “Organizational performance and conceptual capability: The relationship between organizational performance and successors’ capability in a family-owned firm.” Fam. Bus. Rev. 16 (2003): 173–182. [Google Scholar]

- S.M. Danes, M.A. Rueter, H.-K. Kwon, and W. Doherty. “Family FIRO model: An application to family business.” Fam. Bus. Rev. 15 (2002): 31–43. [Google Scholar]

- T.M. Zellweger, K.A. Eddleston, and F.W. Kellermanns. “Exploring the concept of familiness: Introducing family firm identity.” J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 1 (2010): 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C.C. Cruz, L.R. Gomez-Mejia, and M. Becerra. “Perceptions of benevolence and the design of agency contracts: CEO-TMT relationships in family firms.” Acad. Manag. J. 53 (2010): 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Hakim. Research Design: Successful Designs for Social and Economic Research, 2nd ed. London, UK; New York, NY, USA: Routledge, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- D.G. Sirmon, and M.A. Hitt. “Managing resources: linking unique resources, management, and wealth creation in family firms.” Entrep. Theory Pract. 27 (2003): 339–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Allouche, B. Amann, J. Jaussaud, and T. Kurashina. “The impact of family control on the performance and financial characteristics of family versus nonfamily businesses in Japan: A matched-pair investigation.” Fam. Bus. Rev. 21 (2008): 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Getz, and T. Petersen. “Identifying industry-specific barriers to inheritance in small family businesses.” Fam. Bus. Rev. 17 (2004): 259–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. Wennberg, J. Wiklund, K. Hellerstedt, and M. Nordqvist. “Implications of intra-family and external ownership transfer of family firms: Short-term and long-term performance differences.” Strateg. Entrep. J. 5 (2011): 352–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Carney. “Corporate governance and competitive advantage in family-controlled firms.” Entrep. Theory Pract. 29 (2005): 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O. Kowalewski, O. Talavera, and I. Stetsyuk. “Influence of family involvement in management and ownership on firm performance: Evidence from Poland.” Fam. Bus. Rev. 23 (2010): 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Birley. “Owner-Manager attitudes to family and business issues: A 16 country study.” Entrep. Theory Pract. 26 (2001): 63–76. [Google Scholar]

- D. Denison, C. Lief, and J.L. Ward. “Culture in family-owned enterprises: Recognizing and leveraging unique strengths.” Fam. Bus. Rev. 17 (2004): 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Bertrand, and A. Schoar. “The role of family in family firms.” J. Econ. Perspect. 20 (2006): 73–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Sharma, J.J. Chrisman, and J.H. Chua. “Strategic management of the family business: Past research and future challenges.” Fam. Bus. Rev. 10 (1997): 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- R. Basco, and M.J. Pérez Rodríguez. “Studying the family holistically: Evidence for integrated family and business systems.” Fam. Bus. Rev. 22 (2009): 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Goel, I. Jussila, and T. Ikäheimonen. “Governance in family firms: A review and research agenda.” In The SAGE Handbook of Family Business, 1st ed. Edited by L. Melin, M. Nordqvist and P. Sharma. London, UK: SAGE Publications Ltd., 2014, Chapter 12; pp. 226–248. [Google Scholar]

- M. Nordqvist, P. Sharma, and F. Chirico. “Family firm heterogeneity and governance: A configuration approach.” J. Small Bus. Manag. 52 (2014): 192–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A.R. Anderson, S.L. Jack, and S.D. Dodd. “The role of family members in entrepreneurial networks: Beyond the boundaries of the family firm.” Fam. Bus. Rev. 18 (2005): 135–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 1The terms “family business” and “family firm” are used synonymously throughout this article since subdividing this group of companies does not contribute to the research objective. It should be analysed how the object of investigation is generally defined in refereed articles and not on which individual aspects of the heterogeneous group of family companies single articles focus. This is a common procedure in family business research but have to be separated from “family-owned businesses/firms” since these terms only focus on a specific aspect of family businesses, i.e., ownership.

- 2Although an increasing amount of literature about the definition and understanding of the term “family” exists, this review does not intend to comprehensively discuss this aspect because previous research in the family business field has hardly addressed this issue. However, it should be referred to the literature from the field of family studies which is recommended to consider in future family business analyses.

- 3All researchers interested in getting the entire list of journal articles considered for the review are welcome to contact the author.

- 4A list covering all journals under review is provided in Table A2 in Appendix B.

- 5The cluster approach tries to depict a wide range of definitions, but does not raise a claim to completeness. Although, other definitional clusters can—if sufficiently justified—be applied, the author advocates for the use of this systematization in further studies in the interests of comparability.

- 6An overview about the distribution of articles among the individual clusters is given in Table A1 in Appendix A. Results for the overall distribution with respect to particular aspects are available on request. Interested academics are welcome to contact the author.

- 7The seven conceptualized types of family firms according to Westhead and Howorth are (1) cousin consortium family firms, (2) large open family firms, (3) entrenched average family firms, (4) multi-generational open family firms, (5) professional family firms, (6) average family firms and (7) multi-generational average family firms. These groups of family firms have been identified along three axes indicating the influence the family might have on the business, i.e., ownership, management and financial objectives (Westhead and Howorth 2007, [57]).

- 8While all values for individual clusters could be taken from the overview about the distribution of reviewed articles displayed in Table A1 (see Appendix A), additional figures on specific relationships have not been graphically illustrated in this study, but can be provided on request.

- 9Yu et al., 2012 [20] differentiate between seven topics: performance, strategy, social and economic impact, governance, succession, family business roles and family dynamics. Two further categories (other topics and not explicitly specified) has been added for this review since some articles did not fit into Yu et al. taxonomy.

- 10Since some studies address multiple topics, e.g., the influence of family members on governance choices and its effects on performance, some articles have been assigned to more than one topic.

- 11This list of references does not contain all journal articles considered for the analysis but rather only those directly or indirectly cited in this article. An overview about the bibliography of all 267 reviewed articles is available on request.

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Harms, H. Review of Family Business Definitions: Cluster Approach and Implications of Heterogeneous Application for Family Business Research. Int. J. Financial Stud. 2014, 2, 280-314. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs2030280

Harms H. Review of Family Business Definitions: Cluster Approach and Implications of Heterogeneous Application for Family Business Research. International Journal of Financial Studies. 2014; 2(3):280-314. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs2030280

Chicago/Turabian StyleHarms, Henrik. 2014. "Review of Family Business Definitions: Cluster Approach and Implications of Heterogeneous Application for Family Business Research" International Journal of Financial Studies 2, no. 3: 280-314. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs2030280

APA StyleHarms, H. (2014). Review of Family Business Definitions: Cluster Approach and Implications of Heterogeneous Application for Family Business Research. International Journal of Financial Studies, 2(3), 280-314. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs2030280