1. Introduction

In recent decades, the microfinance sector has undergone a profound structural transformation, evolving from institutions supported by international cooperation and aid funds to organisations focused on financial self-sufficiency, economic viability and commercial sustainability (

Bettoni et al., 2023;

Montgomery & Weiss, 2011;

Ledgerwood et al., 2020). This transition, which began at the end of the 20th century (

Morduch, 1999), has intensified in recent years in a global context characterised by a reduction in bilateral and multilateral assistance, which fell by around 16% in Latin America between 2018 and 2019 alone (

OECD, 2021).

Thus, the new financial reality of microfinance institutions (MFIs) is conditioned by multiple factors that threaten their long-term viability and survival, which can be a barrier to the financial inclusion of vulnerable social groups. The disappearance of MFIs due to competition from commercial banks or the need to increase interest rates to contribute to their survival can seriously undermine access to credit for the most disadvantaged groups. Among these threats are, on the one hand, recent economic tensions that have led to a substantial decline in the informal economy—on the order of 81% in Africa and Latin America during periods of crisis (

IADB, 2020)—reducing donations and the flow of microcredit granted (

Wagner & Winkler, 2013), despite the fact that investment in microfinance continues to show attractive risk-adjusted performance (

Janda & Svárovská, 2010;

Dowla, 2006). On the other hand, increased competition from commercial banks entering the microfinance sector (downscaling strategy) has increased pressure on financial margins (

Trujillo & Navajas, 2016;

Banerjee et al., 2015).

Faced with these difficulties, contrary to the widespread belief that the financial sustainability of MFIs requires higher interest rates, empirical evidence indicates that their stability depends more on a prudent leverage structure and the efficient mobilisation of savings (

Hartarska & Nadolnyak, 2007). Recent studies show that a greater focus on profitability is associated with higher interest rates, but not necessarily with higher returns, given that this focus increases operating costs, one of the most decisive factors in the viability and sustainability of MFIs (

Roberts, 2013;

Cuéllar-Fernández et al., 2016).

In this context, the findings of the aforementioned previous research suggest that the current trend towards financial sustainability of MFIs requires the development of three key strategic areas in their management: (a) operational and technological efficiency; (b) reduction in default rates and credit losses; and (c) allocation of interest rates adjusted to individual risk (risk-based pricing) (

Guha & Chowdhury, 2013;

Hermes et al., 2011;

Ruthenberg & Landskroner, 2008).

For the development of these three strategic axes, some previous studies (

Durango et al., 2022;

M. P. Durango-Gutiérrez et al., 2023) propose the usefulness of calculating the probability of default for pricing using artificial intelligence statistical techniques, such as machine learning. In line with recent empirical evidence linking institutional efficiency to greater financial stability (

Kendo & Brou, 2025;

Moreno-Menéndez et al., 2025), in order to establish differentiated interest rates based on each borrower’s risk, it is essential to have a credit scoring model that quantifies the probability of default (PD). Thus, PD is the basis for estimating expected loss (EL) and regulatory capital (K), in accordance with the Basel III guidelines (

BCBS, 2017), constituting a pricing methodology associated with better control of microcredit risk (

Repullo & Suarez, 2004;

Ruthenberg & Landskroner, 2008).

On this basis, although previous studies have recognised the contribution of lowering risk-adjusted financial costs to promoting the financial inclusion of vulnerable groups (

Adusei, 2021;

Repullo & Suarez, 2004), previous research has not addressed how to adjust interest rates to the risk level of MFI borrowers, which could favour lower prices for those customers with lower risk levels, thereby promoting the financial inclusion of disadvantaged groups.

To this end, credit scoring models offer significant advantages to MFIs that adopt them, as they reduce credit analysis costs, speed up decision-making, optimise cash flow, improve the monitoring of existing operations and prioritise collection processes (

West, 2000;

Bekhet & Eletter, 2014;

Wang et al., 2020). Consequently, these models are financial management tools that improve institutional efficiency and reduce delinquency rates. In fact, empirical research in Bolivia and Colombia confirms that the application of credit-scoring models reduces operating costs (

Schreiner, 2004), demonstrating their potential as a sustainability mechanism for MFIs.

Along the same lines, pioneering studies (

Vogelgesang, 2003;

Dinh & Kleimeier, 2007;

Rayo et al., 2010) demonstrated that credit scoring models based on logistic regression or discriminant analysis improve traditional credit assessment and reduce operating costs in microfinance institutions (MFIs). Subsequent research (

Medina-Olivares et al., 2022;

Dorfleitner et al., 2017) shows that incorporating random effects and spatial dependencies increases predictive accuracy by capturing linear relationships that simultaneously affect borrowers in the same region.

However, the adoption of non-parametric and machine learning methods has significantly improved the ability to predict default.

Blanco et al. (

2013) and

Cubiles-De-La-Vega et al. (

2013) demonstrated that neural networks and advanced classification algorithms outperform linear models in accuracy and significantly reduce misclassification costs. Similarly,

Ampountolas et al. (

2021) found that ensemble models, such as Random Forest and XGBoost, offer superior performance in predicting credit risk, even when borrowers lack financial history.

Frolov et al. (

2024) apply gradient boosting and SHAP methods to identify the factors that characterise microcredit borrowers. Recent research in Africa and Asia also confirms that these algorithms consistently outperform logistic regressions by capturing non-linear relationships and interactive effects between socio-economic variables, increasing accuracy and reducing default rates (

Ruiz et al., 2017;

Dushimimana et al., 2020).

However, although previous literature has advanced in the development of models to estimate the probability of default in the microfinance industry, its findings continue to indicate the need to deepen their practical application in order to strengthen the financial sustainability of microfinance institutions (MFIs), which can contribute to the financial inclusion of vulnerable groups. It is therefore interesting to analyse the factors that determine the credit risk of MFI clients, both idiosyncratic, specific to each borrower, and systemic, derived from the macroeconomic and financial environment.

To this end, the standards of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) constitute the international reference framework for prudent financial risk management. In this regard, the Basel III regulations (

BCBS, 2017) represent a significant advance in the measurement of credit and solvency risk. They strengthen capital requirements, extend coverage against systemic risks and promote risk management that is more sensitive and proportional to the level of exposure assumed by financial institutions.

Thus, credit pricing and credit scoring models based on the Basel III Internal Ratings-Based (IRB) approach represent a solid methodological framework for credit risk management (

Repullo & Suarez, 2004;

Ruthenberg & Landskroner, 2008;

Gordy, 2003). This approach allows for more efficient capital allocation, greater risk sensitivity and interest rates adjusted to each borrower’s credit profile. However, these models have been developed and applied mainly in the traditional banking sector, while their implementation in microfinance institutions (MFIs) remains limited. This gap highlights the need to advance the adaptation and application of IRB systems in MFIs so that they can benefit from more accurate tools for risk assessment, capital requirement determination, and the financial sustainability of their credit operations.

With this in mind, the objective of this paper is to design a microcredit pricing model for MFIs that, based on the Internal Ratings-Based (IRB) approach, Basel III and the probability of default, allows interest rates to be set according to the risk of borrowers. This model aims to contribute to the financial inclusion of disadvantaged groups by improving the financial sustainability of MFIs, facilitating access to credit for these groups. To this end, we have selected a sample of 4550 microcredit transactions from an MFI in Guatemala to which we have applied a multilayer neural network (MLP) credit scoring model by analysing 26 influential variables (25 idiosyncratic and 4 systemic). To strengthen the consistency and usefulness of our proposal, we have compared the results of the newly designed model with those derived from parametric models, such as Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) and Logistic Regression (LR), in order to determine which of them offers a more accurate estimate of credit risk.

Although previous literature has made significant progress in estimating the probability of default and in the partial application of regulatory parameters in microfinance institutions, this study offers an incremental contribution by operationally integrating the entire PD–EL–UL–IRB cycle into a comprehensive risk-adjusted pricing system. We also compare the impact of different estimation approaches (LDA, LR, and MLP) on capital requirements, risk premium, and individualised interest rates, providing evidence of how these methodological differences can influence credit risk management in MFIs.

Furthermore, although MFIs are not formally regulated by Basel III, national supervisory authorities in emerging markets—such as the Superintendency of Banks of Guatemala—are progressively adopting prudential guidelines aligned with Basel III, especially with regard to credit risk in retail exposures. Therefore, this study adopts the IRB approach as a conceptual and methodological tool inspired by the principles of Basel III, with the aim of estimating economic capital and designing risk-adjusted pricing mechanisms tailored to the microfinance sector. Although MFIs are not regulated under Basel III, I this work we use these standards as a methodology, not as mandatory regulations.

2. Data and Variables

2.1. Sample Selection

A microcredit database belonging to a microfinance institution (MFI) based in Guatemala was used to carry out this study. The dataset contains financial and non-financial information on 4550 credit operations granted to microenterprises during the period 2019–2021. Of this total, 2182 loans are in default, while 2368 were successfully repaid. Following previous research (

M. P. Durango-Gutiérrez et al., 2023;

Blanco et al., 2013), we have organised the available information into four main blocks: (a) sociodemographic characteristics of the borrower; (b) financial and economic indicators of the microenterprise; (c) specific attributes of the loan granted; and (d) contextual variables linked to the macroeconomic environment.

The dataset is structured at the loan level, so that each transaction is recorded only once and delays in successive instalments do not generate duplicate observations. The temporary increase in arrears during the months of the pandemic partially explains this figure, without compromising the comparative validity of the estimated models, since they are all evaluated under the same conditions.

The choice of this MFI is particularly appropriate for several reasons. First, the selected MFI has reliable, consistent and transparent records on the payment behaviour of its clients, integrating both quantitative and qualitative aspects, in line with previous literature on microfinance (

P. Durango-Gutiérrez et al., 2024;

Blanco et al., 2013). Secondly, the three-year time horizon allows us to capture variations in the evolution of credit risk and analyse the dynamic effects of the explanatory variables, as proposed in previous research (

Shahriar & Garg, 2017;

Shahriar et al., 2016). Furthermore, the sample—selected at random—represents approximately 52% of the institution’s total business microcredit portfolio during the period analysed, which guarantees its representativeness and the statistical validity of the results obtained.

The choice of Guatemala as a case study is justified by its economic and social context, characterised by high levels of inequality and financial exclusion. According to the United Nations Development Programme (

UNDP, 2023), the country has a Human Development Index (HDI) of 0.627, classified as medium-low, and a poverty rate of over 55% of the population, with a particular incidence in rural areas and indigenous communities. In addition, the Gini coefficient, at around 0.48, reflects marked inequality in income distribution. In this environment, microfinance institutions play an essential role in the economic inclusion of vulnerable groups, facilitating access to productive credit for small entrepreneurs who do not have a banking history or traditional guarantees. Therefore, the Guatemalan case constitutes a representative and relevant scenario for analysing the efficiency of credit risk assessment models in emerging economies with low banking penetration.

The choice of the 2019–2021 period is based on three reasons. First, it covers a highly volatile environment such as that of the COVID-19 pandemic, which allows for the assessment of credit risk behaviour under conditions of macroeconomic stress. Secondly, given that some of the explanatory variables, especially those related to the macroeconomic environment, are linked to the total duration of the loan, it was necessary to select only credit operations that had already matured, thus ensuring the consistency and completeness of the database. Finally, as this was a study focused on the methodological design of analytical tools for risk management and adjusted pricing, a sufficiently robust database was required, with temporal representativeness and diversity in borrower profiles and market conditions.

Following the methodology proposed by

Hastie et al. (

2009) for model training and validation, the database was divided into two subsets: a training sample (75%) and a validation sample (25%). This partition was implemented using a 10-fold cross-validation technique, thus ensuring the robustness and predictive consistency of the estimated models.

The use of 10-fold cross-validation is particularly appropriate in this study, given the moderate sample size and the need to maximise the predictive power and generalisation of the model. This procedure reduces the bias derived from possible overfitting and makes efficient use of all the information available in the dataset. Furthermore, this methodology has been widely used in the empirical literature on credit scoring and default prediction models in the microfinance sector (

West, 2000;

M. P. Durango-Gutiérrez et al., 2023), establishing itself as a standard approach for assessing the stability and accuracy of models in financial contexts with high heterogeneity among borrowers.

Furthermore, the period analysed (2019–2021) includes the disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, which significantly affected the credit behaviour of the microfinance sector throughout the region. However, the MFI studied did not apply automatic moratoriums or reclassify operations, so the definition of delinquency and the internal portfolio management policy remained constant. Likewise, the inclusion of macroeconomic variables (GDP growth, inflation, and unemployment) allows these systemic effects to be partially captured and mitigates their influence on the estimation of the probability of default.

2.2. The Dependent Variable

In accordance with previous empirical evidence in the field of microfinance (

P. Durango-Gutiérrez et al., 2024;

Blanco et al., 2013;

Rayo et al., 2010), the dependent variable used in the model is dichotomous. This variable takes the value 1 when the loan is 30 days or more past due on at least one of its repayments, the period after which the microfinance institution (MFI) incurs additional credit monitoring and management costs. Otherwise (no delay of 30 days or more), the variable takes the value 0. This criterion is widely used in microfinance due to the immediate impact that these delays have on liquidity and monitoring costs for MFIs.

Credit risk analysis is approached from the perspective of financial institutions, the main providers of credit and microcredit. The definition of default used in this study is in line with paragraph 90 of the Basel III regulatory framework (

BCBS, 2017) on past due exposures. According to this regulation, a loan is in default when at least one of the following conditions is met:

Default variable 1: . The financial institution considers it unlikely that the borrower will meet all of its credit obligations without resorting to measures such as the enforcement of collateral, if any.

Default variable 2: . The borrower is 30 days or more past due on a significant credit obligation to the institution.

Therefore, the dependent variable used in the model is dichotomous, taking the value 1 when the loan meets any of the above conditions, and 0 otherwise,

, as reflected in the following expression.

2.3. The Independent Variables

Table 1 summarises the independent variables analysed in our empirical study. Following previous research, these variables are grouped into four main categories: personal characteristics of the borrower, financial indicators of the microenterprise, microcredit attributes, and macroeconomic factors. In turn, the variables are classified into two broad dimensions: (a) idiosyncratic, linked to the individual profile of the client; and (b) systemic, associated with the general economic context in which the lending MFI operates. The choice of these types of variables is justified by the conclusions of previous research, whose findings show that variations in credit risk may be due both to the characteristics and behaviour of the borrower and to changes in the general socio-economic context (

Lara-Rubio et al., 2025;

V. Castro, 2013).

As previously stated (

Blanco-Oliver et al., 2016;

Irimia-Dieguez et al., 2015), idiosyncratic variables reflect the particular characteristics of the borrower and their credit transaction, and are divided into three subgroups: non-financial, financial and loan-specific. Among the most relevant are gender, marital status, length of time as a customer, previous credit history, and various accounting ratios of the microenterprise.

In addition, the geographical location of the customer is also a determining factor. Borrowers in urban areas tend to have greater repayment capacity than those in rural areas, so a negative sign is estimated for this variable (

Gutiérrez-Nieto et al., 2016;

Rayo et al., 2010). In terms of employment status, self-employed workers or entrepreneurs tend to present a lower credit risk, partly due to their familiarity with microfinance products (

P. Durango-Gutiérrez et al., 2024;

Newman et al., 2014).

With regard to age and economic sector, the literature does not offer definitive conclusions about the sign of their effect (

Blanco et al., 2013), although we consider these variables to be interesting because of their possible influence on the borrower’s cash flow generation to meet loan payments. For its part, educational level is usually negatively correlated with default risk, given that a higher level of education is associated with better financial practices (

Lin et al., 2017;

Elloumi & Kammoun, 2013).

The length of time the customer has been with the institution (Old) and the number of loans previously granted (Cred_Grant) reflect the strength of the relationship between the borrower and the MFI, so a negative effect on default is also expected (

Lara-Rubio et al., 2025). On the other hand, a history of rejected applications (Denied_Cred) or a high number of current loans (Current_Cred) tend to increase indebtedness and, therefore, credit risk (

Durango et al., 2022;

Blanco et al., 2013). Similarly, for variables that reflect previous payment delays (Delay, Delay_Av) or the proportion of unpaid instalments (Arrears), we expect positive signs, given the foreseeable continuation of the decline in cash flows by the borrower.

Additionally, as previous studies on the solvency of small businesses have concluded (

Navarro-Galera et al., 2024,

2025), financial ratios are key indicators of risk profile. A higher level of asset turnover (R1) or liquidity (R2) tends to reduce the probability of default, and a high amount of debt (R3, R4) increases it. Similarly, higher economic (ROA) or financial (ROE) profitability should be associated with lower credit risk.

In terms of loan characteristics, loans for the acquisition of fixed assets involve greater risk exposure than those for working capital, due to their longer recovery periods (

Mustapa et al., 2018). Therefore, a positive coefficient is expected for the purpose variable. It is also anticipated that a longer loan term, a higher amount or a higher interest rate will increase the probability of default (

M. P. Durango-Gutiérrez et al., 2023;

Vogelgesang, 2003).

Regarding the guarantees provided (Guarant) and the credit analyst’s assessment (Forecast), previous research suggests that both variables directly influence risk perception (

Maes & Reed, 2012;

Cubiles-De-La-Vega et al., 2013), with a positive sign expected in their coefficients.

On the other hand, following previous work (

Lara-Rubio et al., 2025;

J. A. M. Castro et al., 2022), the study of systemic variables is interesting because they incorporate the effect of the macroeconomic environment on credit behaviour. Macroeconomic variables (real GDP, inflation, unemployment and exchange rate) are incorporated in terms of annualised rates of change, but adjusted to the time horizon of each microcredit. For each transaction, the relevant change is calculated as:

where VM represents the macroeconomic variable considered, i the year the loan was granted, and j the duration of the loan. In this way, the macroeconomic indicator reflects the expected economic evolution during the effective exposure period of the loan, and not only in the year it was granted. Higher GDP growth is associated with a reduction in risk (negative sign), while increases in inflation, exchange rates or unemployment tend to raise default rates (positive signs). These variables are calculated as annual rates of change during the term of the loan. This methodology is appropriate in highly volatile contexts—such as 2020–2021 during the COVID-19 pandemic—and has been used in previous literature to reflect structural macroeconomic shocks in credit risk analysis.

3. Research Methodology

The methodological process of this study is carried out in three stages. First, traditional default prediction models (LDA and LR) are applied as a parametric reference. Next, a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) Artificial Neural Network is used to compare its performance with that of the classic models. Finally, the credit scoring results are integrated into a proprietary model based on the Basel III IRB approach, which allows risk-adjusted interest rates to be estimated and their effect on the financial sustainability of MFIs to be analysed.

3.1. Estimation of the Probability of Default

3.1.1. Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA)

Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) is one of the most widely used classical methodologies in the field of default prediction in credit and microcredit portfolios. The technique is based on two fundamental assumptions: (i) that the populations to be classified follow a multivariate normal distribution, with different vector means (μ

1, μ

2) and (ii) that both share a common covariance matrix Σ. In this context, for a p-dimensional vector, the classification criterion consists of assigning the observation to class 2 if the following is true:

where

and

represent the prior probabilities of belonging to each class, usually estimated from the proportions of the training sample (

Johnson & Wichern, 1998). Under these conditions, LDA minimises the classification error rate, resulting in optimality in Bayesian terms.

The linear discriminant can also be expressed as a linear combination of predictors:

where D is the discriminant score, β

0 the independent term, and β

j the coefficients associated with each explanatory variable. The decision rule is formulated by comparing the value of D against a probabilistic threshold p

c, which can be determined using K-fold cross-validation (

Hastie et al., 2009).

In practical terms, for empirical applications in microfinance, a prior variable selection process that optimises discriminant capacity is recommended. Tools such as Wilks’ lambda criterion allow the marginal contribution of each predictor to be evaluated, including only those that significantly reduce group heterogeneity (

Weihs et al., 2005).

Despite its simplicity and the advantage of being an interpretable model, LDA has limitations when the assumptions of multivariate normality and homoscedasticity of the covariance matrix are not met. In such cases, the natural extension is Quadratic Discriminant Analysis (QDA), where different covariance matrices are allowed for each group. However, empirical studies have shown that, even under slight deviations from the classical assumptions, LDA can maintain competitive performance in credit scoring tasks (

Hand & Henley, 1997;

Baesens et al., 2003).

3.1.2. Binary Logistic Regression Model

The logistic regression (LR) model is a standard tool for predicting binary events, such as default in credit portfolios. For a set of p explanatory variables, x

1, …, x

p, which may include both continuous predictors and dummy variables, the logistic link function models the conditional probability of default as follows:

where β

0 is the independent term and β

j are the coefficients that quantify the marginal effect of each predictor. The model parameters are estimated using maximum likelihood, employing iterative weighted least squares algorithms (

Venables & Ripley, 2002).

Inference about the significance of the overall model and each variable can be made through likelihood ratio tests, Wald statistics or score tests. In addition, logistic regression offers interpretability through odds ratios, which allow the magnitude of the effect of each risk factor on the probability of default to be assessed (

Hosmer et al., 2013).

To select the relevant variables, it is common to use stepwise procedures based on information criteria, such as the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) (

Akaike, 1998). In our case, the stepwise procedure was implemented on the initial logistic model, retaining those covariates with the greatest predictive power.

The classification rule requires setting a decision threshold

pc. Following a K-fold cross-validation strategy, multiple values of p

c were explored, selecting the one that minimises classification error. This procedure is essential, as different cut-off points imply assuming different a priori probabilities in the classification (

Hastie et al., 2009).

Although logistic regression is optimal under certain assumptions (multivariate normality and homoscedasticity in the predictors), its flexibility allows it to maintain good performance in more general contexts, provided that the sample size is sufficient. In fact, it can incorporate non-linear transformations or interactions, thus capturing more complex relationships between explanatory variables and credit risk (

Greene, 2018;

Baesens et al., 2003).

3.1.3. Artificial Neural Network Model

Artificial neural networks (ANNs) are a flexible, non-parametric approach that has demonstrated remarkable performance in predicting events in the financial sphere, including the risk of default in credit portfolios. Unlike classical linear models, ANNs can capture non-linear and highly interactive relationships between explanatory variables.

In particular, the multilayer perceptron (MLP) model is one of the most widely used in credit scoring applications. The standard structure consists of an input layer with p neurons (as many as predictors), one or more hidden layers, and an output layer. In this regard, for an individual i, the probability of default is expressed as:

where σ (⋅) corresponds to the sigmoid activation function, and W(l) and b(l) are the weights and biases associated with the layer l.

To ensure the model’s reproducibility, a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) neural network was implemented with the following technical configuration: one hidden layer comprising 6 neurons with ReLU activation, followed by an output layer with sigmoid activation.

The network was trained using the backpropagation algorithm in conjunction with the Adam optimiser, with a learning rate of 0.001. Binary cross-entropy was used as the loss function:

where y

i is the actual label and

is the estimated probability.

ANNs require the selection of fundamental hyperparameters, such as the number of hidden layers, the number of neurons per layer, the learning rate, and the regularisation method. Recent studies have highlighted that incorporating techniques such as dropout or batch normalisation improves predictive power and reduces overfitting in financial data environments (

Srivastava et al., 2014;

Ioffe & Szegedy, 2015). To mitigate overfitting, a 20% dropout regularisation was applied, and training was limited to a maximum of 200 epochs. The batch size was set to 64 observations.

Additionally, model interpretability was enhanced through SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) analysis, which enabled the assessment of each predictor’s marginal contribution to the estimated probability of default, thereby improving transparency in the behaviour of the non-linear model.

Although ANNs sacrifice interpretability compared to models such as logistic regression, their ability to model non-linearities makes them valuable tools in credit risk assessment. In fact, recent literature has shown that, in microfinance contexts, neural models consistently outperform linear methodologies in terms of discrimination metrics such as AUC-ROC (

Lessmann et al., 2015).

3.1.4. Model Evaluation Measures

The Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC) is one of the most widely used metrics for evaluating the discriminative power of classification models. However, the literature recognises that this measure alone does not fully reflect the overall predictive power of the default risk model, as it must be complemented by a priori probabilities and the costs associated with classification errors (

West, 2000;

Lessmann et al., 2015).

In practice, the costs of type I and type II errors are not equivalent. A Type I error occurs when a solvent customer is mistakenly classified as delinquent, while a Type II error corresponds to the opposite case, i.e., when a borrower with a high risk of default is identified as a good payer. Generally, the economic impact of a Type II error is significantly higher, as it involves direct financial losses resulting from loan default.

According to

West (

2000), the ratio between the costs of type I and type II errors is usually close to 1:5, which justifies paying special attention to minimising the second type of error in the design and evaluation of default prediction models.

Consequently, the expected cost of misclassification is calculated by considering the probability structure and costs associated with both populations (solvent and defaulting customers) using the following expression:

where

P(G) and P(B) represent the prior probabilities of borrowers with good and bad microcredit, respectively.

P21 and P12 indicate the probabilities of type I and type II errors.

C21 and C12 are the misclassification costs corresponding to each type of error.

The calculation of the expected classification cost requires estimating, for each prediction model, both the error probabilities and the associated costs. The most commonly used estimates for P21 and P12 correspond to the proportion of solvent customers classified as delinquent and the proportion of delinquent customers classified as solvent, respectively. These coefficients are specific and independent for each model, thus allowing for an accurate comparison of predictive performance between the different methodologies analysed.

3.2. Proposal for a New Internal Ratings-Based Model Under Basel III Regulations

The Basel III reform, promoted by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (

BCBS, 2017), has as its central objective that the capital requirements of financial institutions more accurately reflect the risk actually assumed. To this end, the regulatory framework provides for two alternative approaches to calculating regulatory capital for credit risk: (a) the Standardised Approach; (b) the Internal Ratings-Based Approach (IRB).

In the standardised approach, institutions assign fixed risk weights to credit exposures based on the nature of the asset and the credit rating assigned by external agencies. The capital requirement is determined by applying the capital adequacy ratio (8%) to risk-weighted assets (RWA):

where

: Total capital requirement under the standardised approach.

: Risk weight assigned to exposure i, according to its credit rating.

: Exposure at Default.

This method has the advantage of simplicity, although it suffers from low-risk sensitivity by assigning uniform weightings within the same asset category.

The IRB approach allows financial institutions to internally estimate the main risk parameters: probability of default (PD), loss given default (LGD) and exposure at default (EAD). The model calculates the maximum expected loss—Value-at-Risk (VaR)—with a confidence level of 99.9%, following

Gordy’s (

2003) asymptotic portfolio model:

’s correlation coefficient depends on the level of credit risk and is calculated as:

The resulting capital is converted into risk-weighted assets (RWAs) using:

where

K: Capital requirements.

PD: Probability of default, obtained from credit scoring.

ρ (PD): Correlation coefficient.

LGD: Loss Given Default. Loss percentage or severity at the moment of default.

EAD: Exposure at Default.

RWA: Risk-Weighted Assets. EL: Expected Loss.

G (0.999): Inverse of the Distribution Function Normally accumulated = −3.090.

G (PD): Inverse of the Distribution Function Normally accumulated in PD.

The IRB model thus allows for a more accurate measurement of risk and a more efficient allocation of capital. Its endogenous nature, based on internal parameters, makes it an effective tool for linking risk management with pricing and interest rates.

Although the IRB model from Basel III was originally developed for regulatory capital requirements—based on an unexpected loss quantile at the 99.9% percentile—in this study, we use it as a conceptual and methodological framework. The IRB approach is applied here not as a literal regulatory tool but as a risk-sensitive mechanism to illustrate how credit risk parameters (PD, LGD, EAD) can inform pricing structures within MFIs. This allows an analytical approximation of risk-adjusted interest rates, incorporating capital costs as a component of financial sustainability, while acknowledging that internal pricing practices in MFIs typically integrate broader cost and strategy considerations.

On this basis,

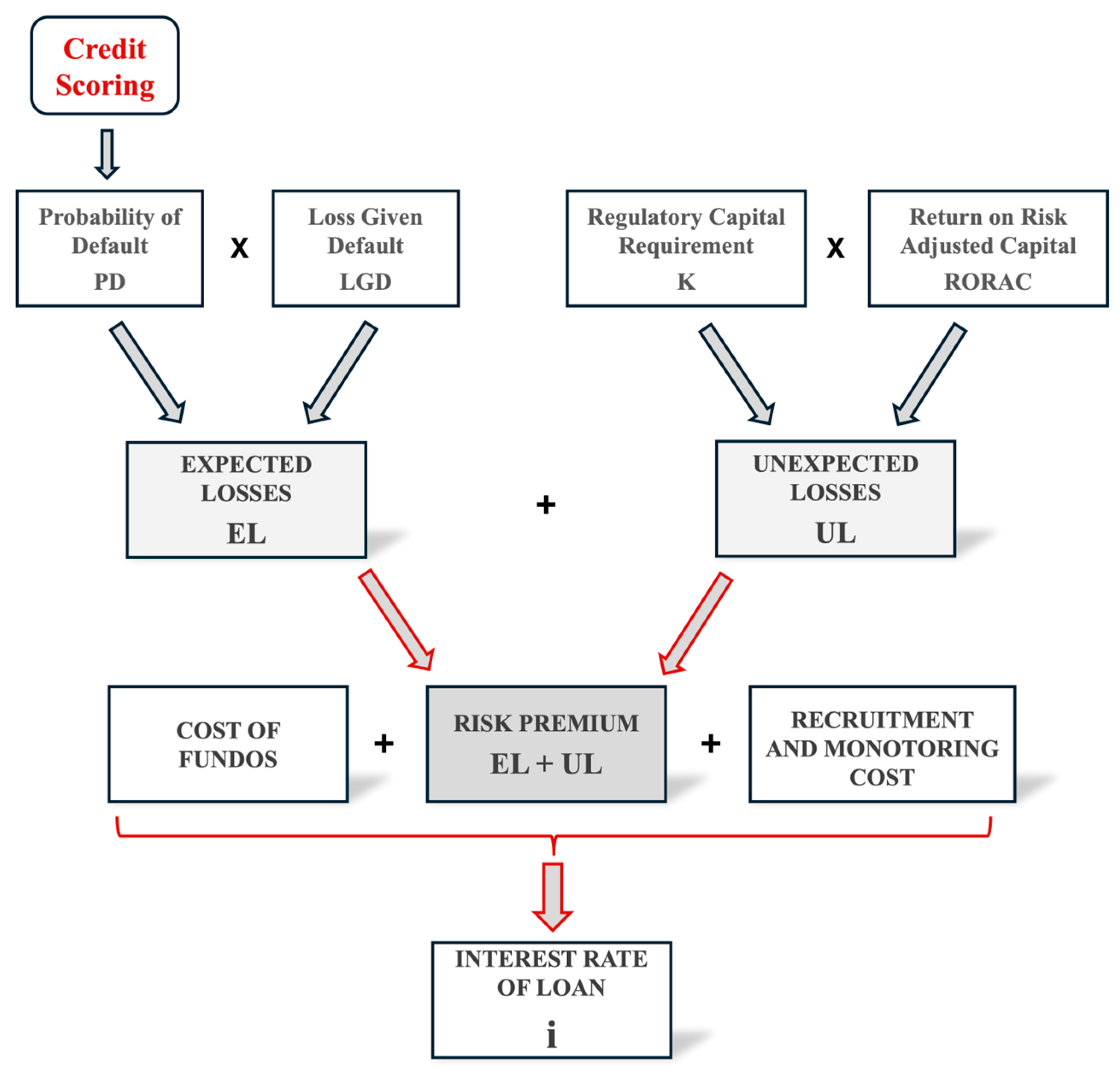

Figure 1 shows the methodological framework we have used to determine the risk-adjusted interest rate, which must be negotiated individually with each borrower, based on the objective of achieving a risk-adjusted return on capital (RORAC) that is optimal for the institution. The results of the credit scoring model are a key element in estimating the risk premium, directly affecting the configuration of the interest rate associated with each client’s RORAC and, consequently, the expected profitability of microfinance institutions in their credit operations.

In our proposed model, the probability of default (PD) directly influences the expected loss (EL), while its indirect effect is manifested in the unexpected loss (UL), as it affects the calculation of the regulatory capital (K) needed to absorb extreme risks. Together, these relationships determine the optimal pricing structure and financial sustainability of microfinance institutions.

Figure 1 presents the conceptual procedure we propose for determining the risk-adjusted interest rate applied to loans by microfinance institutions (MFIs). The scheme sequentially integrates the credit risk components derived from the credit scoring model, the regulatory parameters defined by Basel III, and the financial variables that influence expected profitability.

First, the probability of default (PD), estimated using statistical or artificial intelligence models, is used to calculate the expected loss (EL = PD × LGD × EAD). Subsequently, the unexpected loss (UL) is obtained as a function of the regulatory capital requirement (K), determined by the Internal Ratings-Based (IRB) approach.

The total risk premium (

Pr) is broken down into two elements: the premium associated with the expected loss (

PrEL) and the premium corresponding to the unexpected loss (

PrUL), according to the expression:

where

EL: Expected Loss (covered with the provision);

UL: Unexpected Loss (covered with the capital requirement);

K: Capital requirement;

r: Return on Risk-Adjusted Capital for the sector.

Based on these figures, the risk-adjusted interest rate (IR) is defined in such a way as to guarantee a risk-adjusted return on capital (RORAC) consistent with the entity’s profitability and sustainability objectives. The model incorporates financial income (FR), financial costs (FC), operating costs (OC), and tax rate (TR) in accordance with:

where

FR = Financial Revenue;

FC = Financial Cost;

OP = Operating Cost;

EL = Expected Loss;

IC = Income from Capital;

K = Capital Requirement;

TR = Tax Rate;

EAD = Exposure at Default;

IR: Interest Rate;

Rf: Risk-free rate of interest, such as interest arising from government bonds.

The model proposed under the Basel III IRB approach has advantages over traditional methodologies and models based solely on artificial intelligence. It integrates credit scoring results into capital regulation, allowing for a more efficient allocation of resources. In addition, it facilitates the setting of interest rates adjusted to individual risk and directly links risk management to profitability and financial sustainability, strengthening the competitiveness and social mission of MFIs.

4. Analysis of Results

This section presents the results obtained from the different estimation models. First, the results of the two parametric models (LDA and LR) are compared with the non-parametric model (MLP). Next, the statistical properties of the best-performing credit scoring models are described. Finally, the results derived from the IRB approach we propose are analysed, highlighting its implications for the financial management of MFIs.

In the best-performing model, the artificial neural network, the SHAP method identified the variables with the greatest positive influence on the probability of default as: (a) the level of indebtedness (R4), (b) the history of loan rejections, and (c) the credit analyst’s forecast. Conversely, the variables with the greatest risk-mitigating effect were: (a) the borrower’s length of time as an MFI customer, (b) return on assets, and (c) employment status.

To evaluate the performance of the classification models, the neural network model achieved a binary cross-entropy loss of 0.33 on the validation sample, indicating adequate predictive capacity consistent with expected values in highly heterogeneous binary classification contexts such as microcredit. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) was used as a measure of discriminative ability. In addition, following the proposed by

West (

2000), the expected misclassification cost (EMC) was considered as a complementary performance indicator.

Table 2 shows the AUC values, type I and II errors, and EMC for each model. Although the results are favourable for logistic regression (AUC = 91.99%), the Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) model performs best overall, achieving an AUC of 95.83%. Significant differences are observed between LDA and MLP, with a 14.92% improvement in terms of EMC in favour of the latter. Furthermore, in line with previous studies (

Ohlson, 1980;

Lee et al., 2002), the LR model outperforms LDA in all evaluation metrics.

Consequently, the results confirm, in agreement with

Ince and Aktan (

2009), that MLP models not only offer greater predictive power (higher AUC), but also lower misclassification costs compared to traditional parametric approaches (LR and LDA). Empirical evidence supports the theoretical superiority of MLP neural networks, attributed to their adaptive, non-linear and non-parametric learning properties, which are widely recognised in the literature. Therefore, our results support the recommendation that MFIs adopt MLP models to replace traditional regression-based methods, given that a marginal improvement of 1% in accuracy could translate into a substantial reduction in credit losses and potential savings of millions of dollars in large loan portfolios, in line with

West (

2000).

About the results of the model we propose (IRB approach), previous analyses show that the accuracy of the credit scoring model has a direct impact on MFI pricing policy. In this regard,

Table 3 and

Table 4 show the risk premium of the microcredit portfolio, broken down into expected loss (EL) and capital requirements (K), both for the Basel II standardised approach (

BCBS, 2006) and for the Basel III IRB approach (

BCBS, 2017), using default probabilities estimated using LDA, LR and MLP. The results show that the IRB approach based on MLP models provides significant benefits for MFIs, simultaneously reducing regulatory capital requirements and expected loss, compared to parametric models and the standardised Basel II approach (

BCBS, 2006).

These results underscore the practical relevance of model selection in risk-adjusted pricing strategies. For instance, the MLP-based approach, despite its non-parametric nature, offers a more adjusted risk segmentation, resulting in a more precise interest rate spread compared to traditional methods.

Table 4 shows that the MLP neural network model allows for a significant reduction in capital requirements compared to traditional parametric models (LDA and logistic regression). This reduction translates into a lower Value at Risk (VaR). This result can be explained by the greater discriminating power of the MLP model to capture non-linear patterns and complex relationships between predictor variables and the probability of default (PD). By estimating the actual probability of default more accurately, the model improves risk segmentation, which reduces the residual volatility of the loss and, therefore, the amount of capital required to cover extreme events. In other words, lower residual uncertainty allows institutions to allocate capital more efficiently, without oversizing it, resulting in a substantial improvement in the efficiency of risk-based pricing.

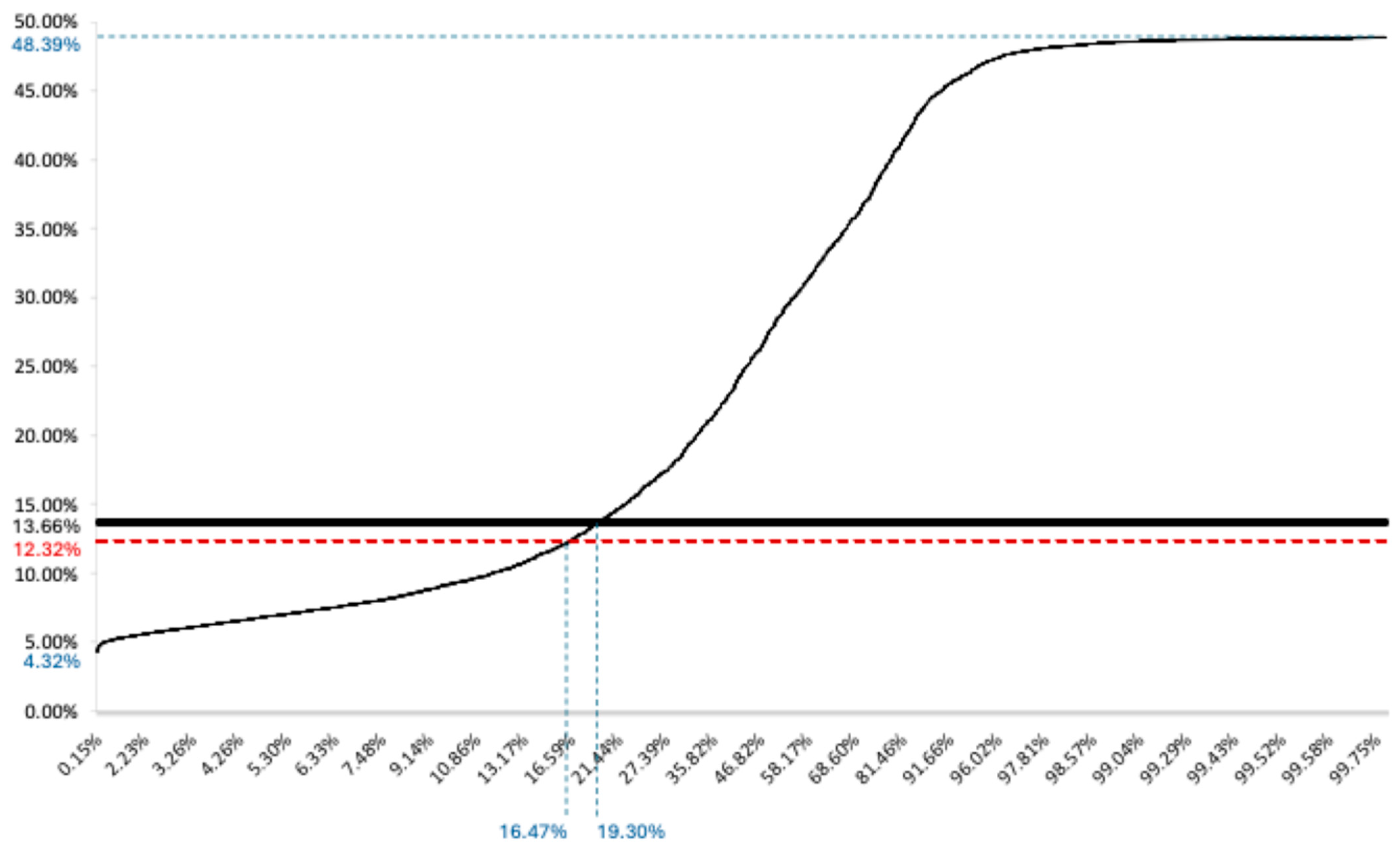

Finally, a simulation was carried out of the interest rate that the MFI should apply to its borrowers under the IRB-MLP and standardised approaches. The data used was constructed according to the following criteria: (1) a RORAC of 17.14% was considered, calculated as the average ROE of the MFI, using the financial indicators published in the statistics section of the Superintendency of Banks of Guatemala; (2) the individual interest rate for each microloan was determined so that the RORAC was equivalent to 17.14%; and (3) an average real annual interest rate of 12.32% was adopted, corresponding to the rate historically applied by the MFI during the period analysed.

The results of this simulation are presented in

Figure 2. It shows that the real annual interest rate applied by the MFI is associated with an average PD of 16.47%. Also, under the IRB-MLP approach, the interest rates applied by the MFI should vary between 4.32% and 48.89%, depending on the estimated probability of default (PD) for each customer. In contrast, the standardised approach would maintain a fixed interest rate of 13.66%, regardless of the borrower’s risk level.

These results reveal that the IRB-MLP approach allows for individualised credit pricing, adjusted to each client’s risk profile. Consequently, the IRB system is fairer for borrowers and more efficient for the institution, as it applies higher rates to customers with a high risk of default and lower rates to those with a better credit history. The intersection between the interest rate estimated using IRB and that derived from the standardised approach is at a PD of 19.30%. Therefore, all borrowers with a PD below 19.30% would benefit from a lower interest rate if the MFI applied the IRB approach instead of the standardised approach, and those borrowers with a PD below 16.47% would also benefit from an interest rate lower than the actual average interest rate of 12.30% observed at the institution.

We recognise that the risk-adjusted IRB model can generate high rates for borrowers with a high risk of default. However, this tool can help MFIs to segment their portfolios more accurately and design solidarity or differential schemes that reduce the financial burden on borrowers with good credit behaviour. These conditions could promote environments of greater compliance, lower structural default rates and, ultimately, improve the efficiency of the microfinance system, without compromising its inclusive nature.

Although the study is based on data from a single MFI in Guatemala, the methodology proposed is highly replicable in other countries in Central America, South America and even Asia. These regional contexts share common structural characteristics that directly affect the probability of default, such as high levels of informal employment, limited access to bank credit, scarce availability of collateral, high dispersion of individual risk, and vulnerability to macroeconomic shocks. Therefore, the proposed methodological framework is particularly useful for risk managers operating in emerging environments with structurally similar conditions. In particular, our findings could be interesting to countries with a Human Development Index similar to that of Guatemala, which is 0.627 (

UNDP, 2023).

5. Conclusions

This research makes a novel contribution by integrating the full credit risk pricing cycle, PD, EL, UL, IRB capital and risk-based interest rates, into a coherent and operational framework. It combines traditional and machine learning-based PD estimates to derive capital requirements and personalised pricing, allowing for a direct application to real microfinance portfolios. Unlike prior literature, this approach enables a systematic comparison of parametric and non-parametric models under IRB logic and includes a full pricing simulation exercise that quantifies how model selection impacts financial sustainability in MFIs.

The empirical analysis of a sample of 4550 microcredit transactions, for which 26 influential variables (25 idiosyncratic and 4 systemic) were studied, has allowed us to design a pricing model for MFIs based on the Internal Ratings-Based (IRB) approach and the Basel III framework. The empirical results derived from our proposed model reveal that the IRB approach based on MLP models is very interesting and relevant for the financial management of MFIs because it simultaneously reduces capital requirements and expected loss.

This finding, which represents an advance over the results of applying parametric models and the Basel II standardised method, provides considerable benefits for MFI decision-making. The IRB system is fairer for borrowers and more efficient for MFIs, as it allows lower interest rates to be applied to borrowers with better credit histories. Thus, our results indicate that the application of the proposed IRB model can improve the supply of credit, sustainability, competitiveness and viability of MFIs by promoting operational efficiency and reducing default rates.

The IRB approach does not imply a uniform reduction in interest rates for all borrowers. As it is a risk-based pricing system, customers with a higher probability of default may face higher rates, while those with lower risk profiles benefit from significant reductions. This differentiation is inherent to risk-based pricing and does not contradict the social mission of MFIs: by improving financial sustainability and reducing losses, institutions can maintain their capacity to serve vulnerable groups. Furthermore, in many microfinance schemes, borrowers show gradual improvements in their credit behaviour thanks to financial learning processes and social cohesion dynamics. In these cases, a risk-adjusted pricing scheme acts as an incentive mechanism, allowing for reductions in the cost of credit when the level of risk decreases and facilitating the consolidation of more efficient and sustainable microenterprises. In short, our findings and results help each borrower to bear interest rates adjusted to their individual risk level, no more, thus promoting financial inclusion through financing opportunities.

Therefore, the results of applying the proposed model can contribute to the financial inclusion of the most disadvantaged groups for two reasons. First, setting interest rates adjusted to the borrower’s level of risk contributes to borrowers’ access to financing, especially those with better credit histories, preventing them from being charged interest rates above those posed by individual risk. Secondly, the application of the new model enables MFIs to improve their credit offerings, efficiency, competitiveness vis-à-vis commercial banks and viability, increasing their survival and, therefore, the chances of access to credit for the most disadvantaged potential customers.

More specifically, our results allow us to draw three main conclusions. First, the findings expand on previous empirical evidence and confirm that the multilayer perceptron (MLP) credit scoring model not only provides greater predictive accuracy but also generates lower expected misclassification costs than the classic parametric models of linear discriminant analysis (LDA) and logistic regression (LR) applied to the field of microcredit. These results reinforce the suitability of using MLP credit scoring models, as they enable MFIs to manage the credit risk of their portfolios with greater efficiency and technical rigour, reducing the cost of credit analysis and losses from defaulting borrowers, while streamlining decision-making and optimising payment recovery processes.

Secondly, our results show that implementing the IRB approach, using default probabilities estimated using the MLP model, generates the greatest benefits for the MFI analysed, both in terms of reducing capital requirements and improving risk-adjusted interest rates. Furthermore, a correct estimation of microcredit risk across the entire portfolio allows for a reduction in the interest rates applied under the standard and IRB approaches, compared to the rates currently in force at the MFI studied. These substantial reductions in interest rates not only strengthen the competitiveness and market share of MFIs, even in a sector with negative growth rates, but also promote financial inclusion and entrepreneurship by facilitating the creation of new micro-enterprises by people at the base of the socioeconomic pyramid. This effect generates positive externalities on economic and social development, both at the individual and national levels.

Finally, empirical evidence indicates that, as in traditional banking, the IRB approach applied to the microfinance sector is more risk-sensitive than the standardised approach. Specifically, borrowers with probabilities of default (PD) below 19.30% benefit from the application of the IRB approach, with interest rates ranging from 4.32% to 16.66%. On the other hand, customers with PDs above 19.30% will prefer the standardised approach, in which the interest rate remains fixed at 16.66%.

In short, from the point of view of MFI decision-making, our empirical findings reveal the interest and advantages of the IRR approach with default probabilities derived from MLP models. This approach offers the greatest benefits in terms of reduced credit losses, lower capital requirements and interest rates that are better adjusted to risk, thus establishing itself as a strategic tool for competitiveness vis-à-vis commercial banks, which can contribute to the financial inclusion of disadvantaged groups.

A significant limitation of this study is the absence of a sensitivity analysis to assess the model’s response to variations in macroeconomic conditions, such as episodes of high inflation or GDP contraction. This omission partially limits the proposed approach’s ability to capture dynamics under stress scenarios. Future research could address this limitation through ex ante simulations incorporating different macrofinancial assumptions.

Furthermore, in future research, we aim to extend our methodological approach by incorporating other sources of risk, such as operational or behavioural factors, which may also affect the pricing dynamics of microcredit portfolios. Incorporating them could enhance the analytical robustness of the model and improve its applicability across diverse financial systems.