Sustainable Finance, Green Bonds and Financial Performance—A Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Q1: What research methods and analytical approaches have been used to investigate the relationship between green bond issuance, corporate financial performance, and cost of debt?

- Q2: What are the main findings, dominant trends, and gaps in the literature on the financial implications of green bonds?

- Q3: To what extent do existing studies reveal geographical or temporal differences in these outcomes, particularly between developed and emerging markets?

- Q4: What contextual factors—such as certification, disclosure quality, sector, or issuer type—have been identified as moderators influencing the relationship between green bond issuance and financial outcomes?

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Bonds and Capital Markets

2.2. Green Bonds: Concepts and Evolution

2.2.1. Definition and Taxonomies

2.2.2. Motivations for Issuing Green Bonds

2.2.3. Growth of the Green Bond Market and Key Issuers

2.2.4. Market Perceptions and ESG Integration

2.3. Green Bond Issuance and Firm-Level Impacts

2.4. Financial Performance: Concepts and Measurement

2.5. Cost of Debt and the Greenium Effect

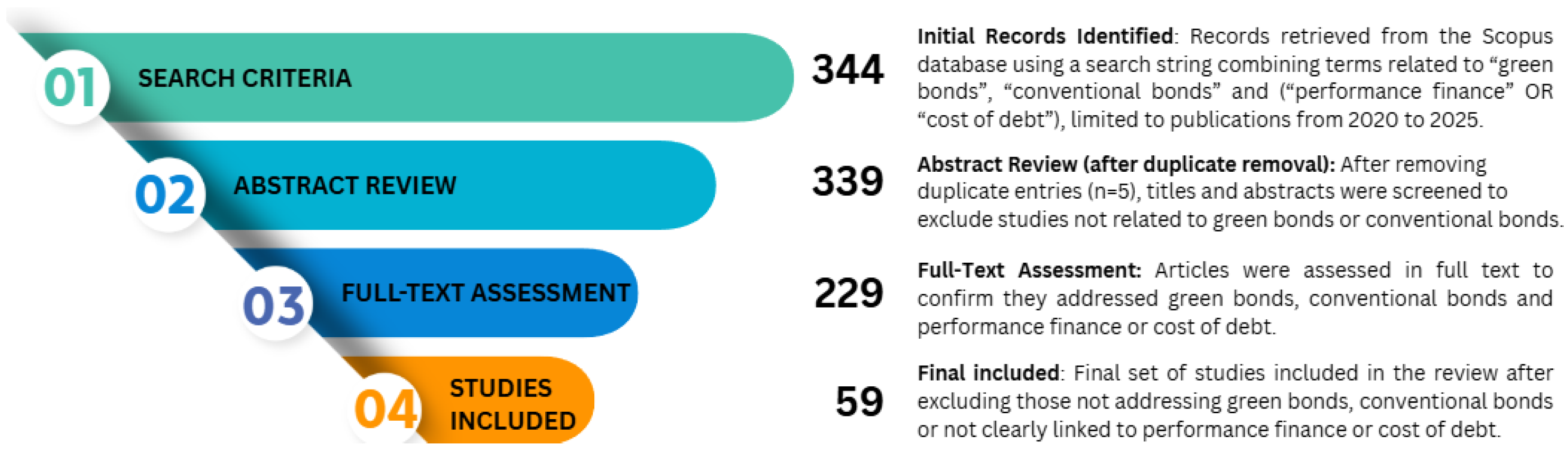

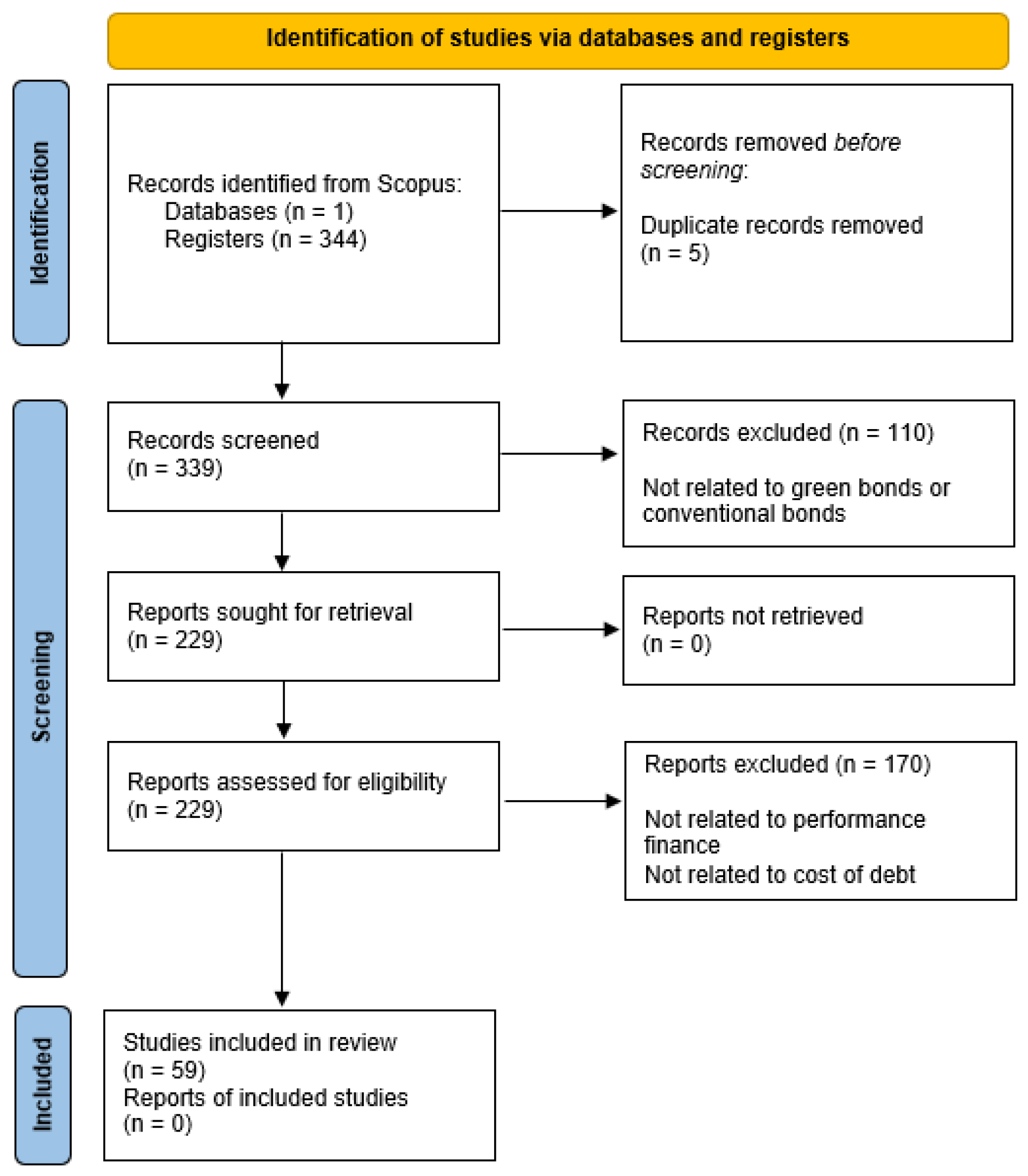

3. Materials & Methods

- Green bonds and financial performance: studies were included if they examined corporate issuers of green, sustainable, climate, or environmental bonds; measured financial performance outcomes such as return on assets (ROA), return on equity (ROE), EBITDA, profitability ratios, stock returns, or market valuation; included a comparison group of conventional bond issuers or non-issuers; employed empirical quantitative methods (experimental, quasi-experimental, or observational designs); relied on financial data from publicly traded companies or firms with accessible information; maintained a corporate-level focus rather than sovereign or municipal issuers; emphasized financial outcomes rather than exclusively environmental or social dimensions; and conducted firm-level analyses of financial performance rather than focusing solely on bond pricing or market-level indicators. Purely theoretical papers, descriptive reports, or opinion pieces were excluded.

- Green bonds and cost of debt (Greenium): studies were included if they examined corporate green bond issuers; incorporated a comparison group of non-issuers or conventional bond issuers; measured cost of debt outcomes such as bond pricing, yield spreads, Greenium, or green premium; employed empirical quantitative analysis; originated from peer-reviewed journals or reports from established financial organizations; explicitly measured financial metrics rather than exclusively environmental or social outcomes; provided firm-level analyses of financial impacts rather than market development or policy-level perspectives; and offered comparative analysis beyond single-firm or single-issuance case studies.

Classification and Coding

4. Results

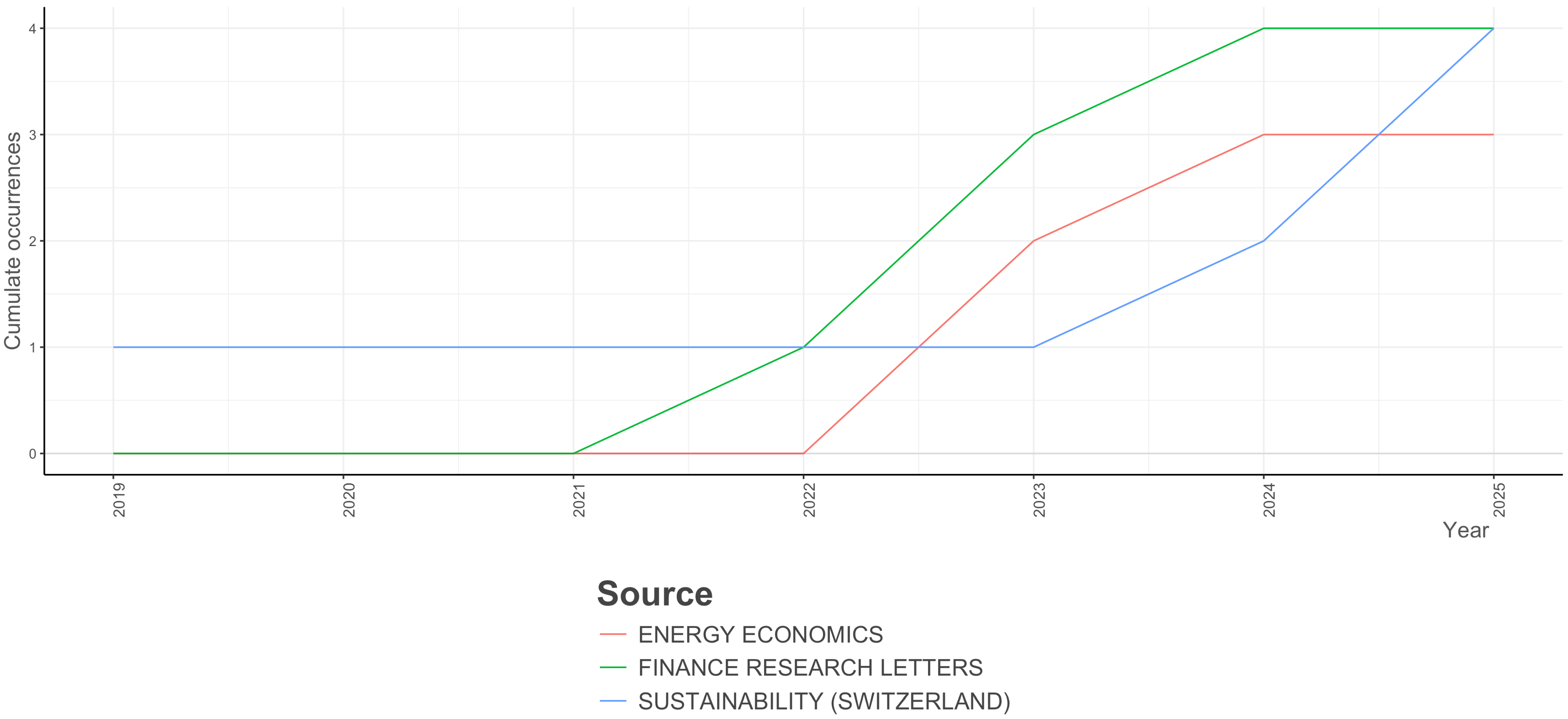

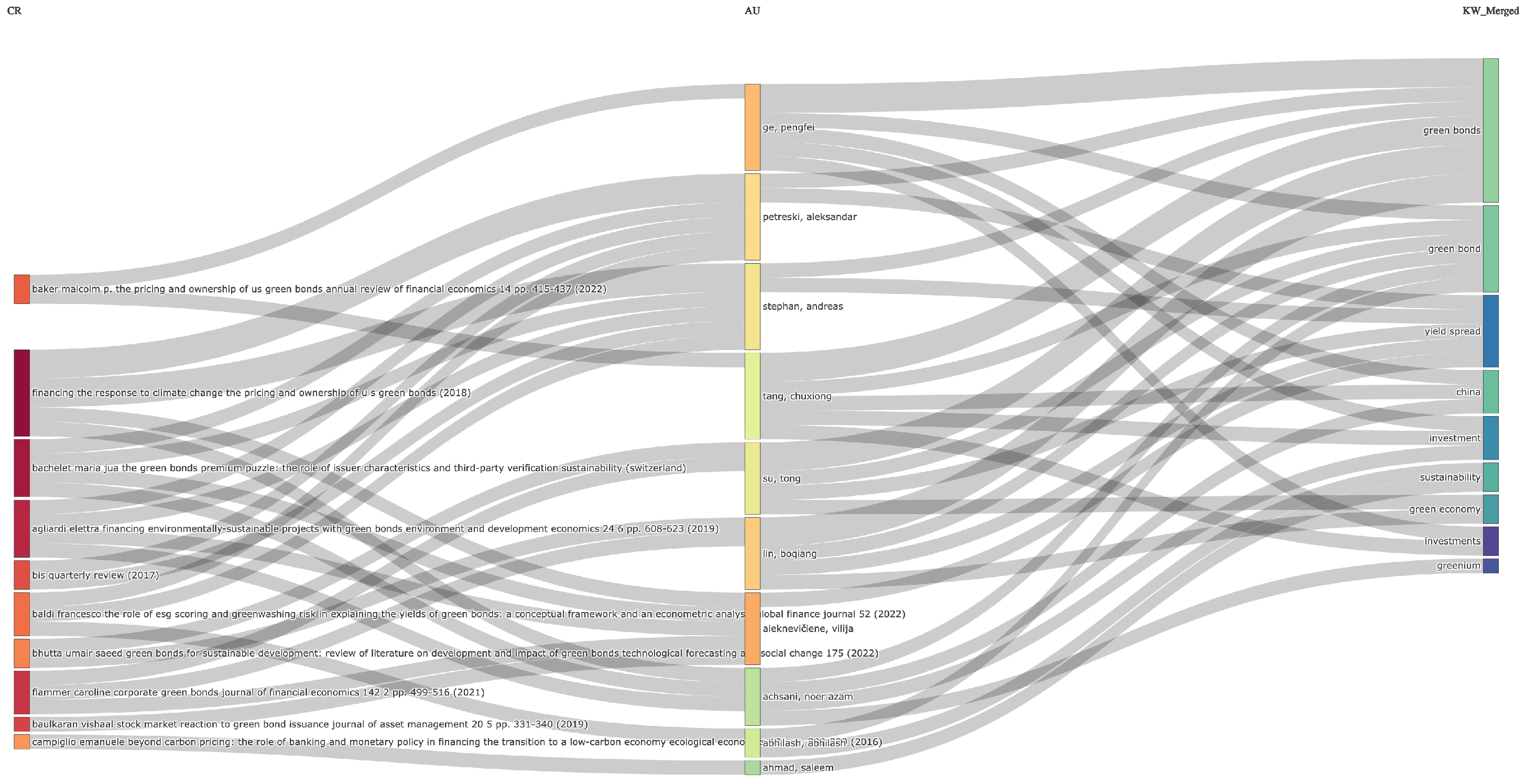

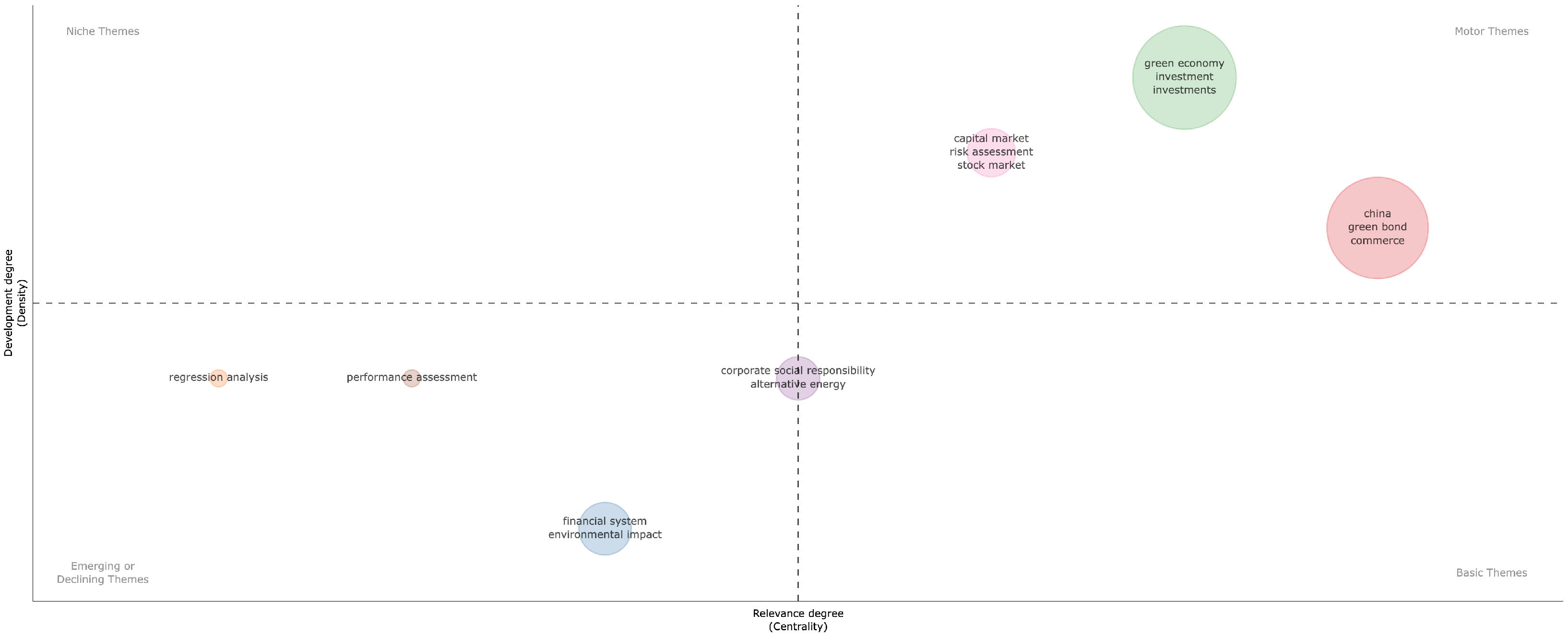

4.1. General Characteristics of the Studies

4.2. Classification of Articles

5. Discussion

5.1. Green Bonds and Finance Performance

5.2. Green Bonds and Cost of Debt “Greenium”

5.3. Green Bonds and Short and Long-Term Financial Outcomes

5.4. Green Bonds and Developed and Emerging Markets Effects

6. Conclusions

Research Gaps and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AR | Abnormal Return |

| CAAR | Cumulative Average Abnormal Return |

| CAR | Cumulative Abnormal Return |

| CSMAR | China Stock Market & Accounting Research (database) |

| DID | Difference-in-Differences |

| EBITDA | Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization |

| ESG | Environmental, Social, and Governance |

| EU | European Union |

| EU GBS | EU Green Bond Standard |

| GBP | Green Bond Principles |

| GMM | Generalized Method of Moments |

| ICMA | International Capital Markets Association |

| LSEG | London Stock Exchange Group |

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PSM | Propensity Score Matching |

| ROA | Return on Assets |

| ROE | Return on Equity |

| S&P | Standard & Poor’s (e.g., S&P Capital IQ) |

| SEC | U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission |

| Wind | Wind Financial Database (China) |

| Z-SPREAD | Zero-volatility spread |

Appendix A. Search Queries (Verbatim)

Appendix B. Data and Software Environment

Appendix C. Screening Checklist and Inter-Rater Protocol

Appendix D. Coding Notes (Compact Data Dictionary)

References

- Abhilash, A., Shenoy, S., & Shetty, D. (2024). Factors influencing green bond yield: Evidence from Asia and Latin American countries. Environmental Economics, 15(1), 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agliardi, E., & Agliardi, R. (2019). Financing environmentally-sustainable projects with green bonds. Environment and Development Economics, 24, 608–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S., & Mokhchy, J. (2023). Corporate social responsibilities, sustainable investment, and the future of green bond market: Evidence from renewable energy projects in Morocco. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30(6), 15186–15197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleknevičiene, V., Kazilionienė, A., & Bendoraitytė, A. (2025). Does the green bond premium exist in the secondary market? Evidence from Nordic countries. Equilibrium. Quarterly Journal of Economics and Economic Policy, 20(1), 327–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleknevičiene, V., & Vilutytė, R. (2024). Short-term stock market reaction to the announcement of green bond issue: Evidence from Nordic countries. Green Finance, 6(4), 728–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arhinful, R., Obeng, H., Mensah, L., & Mensah, C. (2025). Signaling sustainability: The impact of sustainable finance on dividend policy among firms listed on the London stock exchange. Business Strategy and the Environment, 34, 8001–8019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, M., & Cuccurullo, C. (2017). bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. Journal of Informetrics, 11(4), 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aswani, J., & Rajgopal, S. (2022). Rethinking the value and emission implications of green bonds. SSRN Working Paper. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydoğmuş, M., Gülay, G., & Ergun, K. (2022). Impact of ESG performance on firm value and profitability. Borsa Istanbul Review, 22, S119–S127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badía, G., Cortez, M., & Silva, F. (2024). Do investors benefit from investing in stocks of green bond issuers? Economics Letters, 242, 111859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M., Bergstresser, D., Serafeim, G., & Wurgler, J. (2022). The pricing and ownership of US green bonds. Annual Review of Financial Economics, 14, 415–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldi, F., & Pandimiglio, A. (2022). The role of ESG scoring and greenwashing risk in explaining the yields of green bonds: A conceptual framework and an econometric analysis. Global Finance Journal, 52, 100711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballester, L., González-Urteaga, A., & Shen, L. (2024). Green bond issuance and credit Risk: International evidence. Journal of International Financial Markets Institutions and Money, 94, 102013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracking, S., Borie, M., Sim, G. J., & Temple, T. (2023). Turning investments green in bond markets: Qualification, devices and morality. Economy and Society, 52, 626–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremus, F., Schuetze, F., & Zaklan, A. (2021). The impact of ECB corporate sector purchases on European green bonds. SSRN Working Paper. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X., Jin, C., & Ma, W. (2021). Motivation of Chinese commercial banks to issue green bonds: Financing costs or regulatory arbitrage? China Economic Review, 66, 101582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caramichael, J., & Rapp, A. C. (2022). The green corporate bond issuance premium. SSRN Working Paper. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, S., Demirtas, G., & Isaksson, M. (2015). Corporate bonds, bondholders and corporate governance. (OECD Corporate Governance Working Papers 16). OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadegani, A., Salehi, H., Yunus, M., Farhadi, H., Fooladi, M., Farhadi, M., & Ale Ebrahim, N. (2013). A comparison between two main academic literature collections: Web of science and scopus databases. Asian Social Science, 9(5), 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K., & Liao, V. (2025). Sustainability commitment, environmental achievement, and green bond premium. Journal of Environmental Management, 392, 126875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K., Feng, Y., Liu, W., Lu, N., & Li, S. (2021). The impacts of liquidity measures and credit rating on corporate bond yield spreads: Evidence from China’s green bond market. Applied Economics Letters, 28(17), 1824062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, C., & Choi, J. (2020). Green bonds: A survey. Journal of Derivatives and Quantitative Studies, 28, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioli, V., Colonna, L. A., Giannozzi, A., & Roggi, O. (2021). Corporate green bond and stock price reaction. International Journal of Business and Management, 16, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damodaran, A. (2011). Applied corporate finance. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Deschryver, P., & de Mariz, F. (2020). What future for the green bond market? How can policymakers, companies, and investors unlock the potential of the green bond market? Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 13, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine, A., & McCollum, M. (2022). Advancing energy efficiency through green bond policy: Multifamily green mortgage backed securities issuance. Journal of Cleaner Production, 345, 131019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H., Zhang, L., & Zheng, H. (2024). Green bonds: Fueling green innovation or just a fad? Energy Economics, 135, 107660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorfleitner, G., Utz, S., & Zhang, R. (2022). The pricing of green bonds: External reviews and the shades of green. Review of Managerial Science, 16(3), 797–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutordoir, M., Li, S., & Quariguasi Frota Neto, J. (2024). Issuer motivations for corporate green bond offerings. British Journal of Management, 35(2), 952–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, R., Xiong, X., Li, Y., & Gao, Y. (2023). Do green bonds affect stock returns and corporate environmental performance? Evidence from China. Economics Letters, 232, 111322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fandella, P., & Cociancich, V. (2024). Uncovering the greenium: Investigating the yield spread between green and conventional bonds. Investment Management and Financial Innovations, 21(2), 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, F., Si, D., & Hu, D. (2023). Green bond spread effect of unconventional monetary policy: Evidence from China. Economic Analysis and Policy, 80, 398–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammer, C. (2020). Green bonds: Effectiveness and implications for public policy. The University of Chicago Press Journal, 1, 95–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, H. (2025). Green bond policy and corporate ESG performance. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences, 156, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, P., Yue, W., Tang, C., & Zhu, R. (2024). How does the issuance of green bonds impact stock price crash risk: An analysis utilizing the NCSKEW and DUVOL. Journal of Environmental Management, 367, 121999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianfrate, G., & Peri, M. (2019). The green advantage: Exploring the convenience of issuing green bonds. Journal of Cleaner Production, 219, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, D. (2023). Do green bond issuers suffer from financial constraints? Applied Economics Letters, 30(14), 2083559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grishunin, S., Bukreeva, A., Suloeva, S., & Burova, E. (2023). Analysis of yields and their determinants in the european corporate green bond market. Risks, 11(1), 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, C., Partridge, C., & Tripathy, A. (2020). What’s in a greenium: An analysis of pricing methodologies and discourse in the green bond market. SSRN Working Paper. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3684927 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Hoang, T.-H.-V., Berrou, R., & Pham, L. (2022). The impact of green bond issuance on firms’ financial and ESG performance: Does the proportion of green bonds matter? SSRN Working Paper. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, N., Nguyen, V., Hong, Q., Duc, M., Hien, H., Yen, N., & Mai, V. (2025). Impact of COP26 and COP27 events on investor attention and investor yield to green bonds. Sustainability, 17(4), 1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X., Zhong, A., & Cao, Y. (2022). Greenium in the Chinese corporate bond market. Emerging Markets Review, 53, 100946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X., Zhu, B., Lin, R., Li, X., Zeng, L., & Zhou, S. (2024). How does greenness translate into greenium? Evidence from China’s green bonds. Energy Economics, 133, 107511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C., Dekker, D., & Christopoulos, D. (2023). Rethinking greenium: A quadratic function of yield spread. Finance Research Letters, 54, 103710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X., Tang, C., Liu, Y., & Ge, P. (2025). Greening or greenwashing? Corporate green bonds and stock pricing efficiency in China. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 16(3), 874–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M., Jaweed, M., Murtaza, M., & Ali, M. (2025). Green bonds and sustainable investment strategies: Evaluating risk-return profiles, market growth, and the role of climate-conscious portfolios in sustainable finance. Advance Journal of Econometrics and Finance, 3, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, T. L. D., Ridder, N., & Wang, M. (2022). Beyond the shades: The impact of credit rating and greenness on the green bond premium. SSRN Working Paper. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, S., Park, D., & Tian, S. (2023). The price of frequent issuance: The value of information in the green bond market. Economic Change and Restructuring, 56(5), 3041–3063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indriastuty, D. E., Pujianto, & Widiantoro, A. (2020). Policy direction and regulation of green bonds in Indonesia. Journal of Law, Policy and Globalization, 101, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, C. J. C. (2013). Environmental training in organisations: From a literature review to a framework for future research. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 74, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K., Chen, Z., & Chen, F. (2022). Green creates value: Evidence from China. Journal of Asian Economics, 78, 101425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J., & Zhang, J. (2023). The stock performance of green bond issuers during COVID-19 pandemic: The case of China. Asia-Pacific Financial Markets, 30(1), 211–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junior, M. L., & Godinho Filho, M. (2010). Variations of the kanban system: Literature review and classification. International Journal of Production Economics, 125(1), 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kant, A. (2021). Practical vitality of green bonds and economic benefits. Review of Business and Economics Studies, 9, 62–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapraun, J., Latino, C., Scheins, C., & Schlag, C. (2019). (In)-credibly green: Which bonds trade at a green bond premium? SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurram, M., Xie, W., Mirza, S., & Tong, H. (2023). Green bonds issuance, innovation performance, and corporate value: Empirical evidence from China. Heliyon, 9(4), e14895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H., & Ahn, H. (2022). Is there a greenium in Korean bond markets?: An empirical analysis of bond secondary-market trading data*. Korean Journal of Financial Studies, 51(4), 383–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodiyatt, S., Biju, A., Jacob, M., & Reddy, K. (2024). Does green bond issuance enhance market return of equity shares in the Indian stock market?*. Asia-Pacific Journal of Financial Studies, 53(3), 390–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, J. R., & Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33(1), 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansink, A. O., & Kapelko, M. (2025). Do sustainability-linked bonds pay lower interest rates? Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 32, 5337–5347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebelle, M., Lajili-Jarjir, S., & Sassi, S. (2020). Corporate green bond issuances: An international evidence. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 13(2), 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q., Zhang, K., & Wang, L. (2022). Where’s the green bond premium? Evidence from China. Finance Research Letters, 48, 102950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Yu, C., Shi, J., & Liu, Y. (2023). How does green bond issuance affect total factor productivity? Evidence from Chinese listed enterprises. Energy Economics, 123, 106755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, J., & Hou, X. (2024). Navigating geopolitical risks: Deciphering the greenium and market dynamics of green bonds in China. Sustainability, 16(15), 6354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenberger, A., Braga, J., & Semmler, W. (2022). Green bonds for the transition to a low-carbon economy. Econometrics, 10(1), 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loew, E., Endres, L., & Xu, Y. (2024, January 19). How ESG performance impacts a company’s profitability and financial performance (European Banking Institute Working Paper Series, No. 162). Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4700173 (accessed on 10 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Löffler, K., Petreski, A., & Stephan, A. (2021). Drivers of green bond issuance and new evidence on the “greenium”. Eurasian Economic Review, 11(1), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macaire, C., & Naef, A. (2023). Greening monetary policy: Evidence from the People’s Bank of China. Climate Policy, 23(1), 2013153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makpotche, M., Bouslah, K., & M’Zali, B. (2024). Long-run performance following corporate green bond issuance. Managerial Finance, 50(1), 140–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monk, A., & Perkins, R. (2020). What explains the emergence and diffusion of green bonds? Energy Policy, 145, 111641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, A., Cheng, M., Bangash, R., & Osinska, M. (2025). The impact of green bonds on firm cost of capital, and market stability: A global analysis. Studies in Economics and Finance. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, K. N. (2012). Corporate bond market in India: Current scope and future challenges. SSRN Electronic Journal. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nair, B. A. V., Reddy, K., Tan, Y., & Wallace, D. (2022). The effect of green bond issuance and ESG ratings on energy companies’ returns in China and Japan. SSRN Electronic Journal. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanayakkara, M., & Colombage, S. (2021). Does compliance with green bond principles bring any benefit to make G20’s ‘green economy plan’ a reality? Accounting and Finance, 61(3), 4257–4285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurvita, T., Achsani, N., Anggraeni, L., Malahayati, M., & Novianti, T. (2024). Exploring greenium and the determinants of green bond performance in Asia. Journal of Environmental Assessment Policy and Management, 26(4), 2450015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petreski, A., Schäfer, D., & Stephan, A. (2025). The reputation effect of repeated green-bond issuance and its impact on the cost of capital. Business Strategy and the Environment, 34(2), 2436–2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, M. C. P., & Cantarinha, A. I. G. (2024). Do green bonds issue statistically significant effect on the indebtedness’ European companies’ performance? Revista de Gestão Social e Ambiental, 18(10), e09499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polić, N., Kozarević, E., & Džafić, J. (2015). Development of corporate bond markets in emerging market countries: Empirical evidence from Bosnia and Herzegovina. International Business Research, 8(4), 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queen, I. (2016). Green bonds and climate change: State of the art or artful dodge? [Master’s thesis, Miami University]. Available online: https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2016MsT..........3Q (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Reboredo, J. C., & Ugolini, A. (2019). Price connectedness between green bond and financial markets. Economic Modelling, 88, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojon, C., Okupe, A., & McDowall, A. (2021). Utilization and development of systematic reviews in management research. International Journal of Management Reviews, 23(2), 191–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seuring, S. (2013). A review of modeling approaches for sustainable supply chain management. Decision Support Systems, 54(4), 1513–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, I. (2022). Environmental, social, and governance (esg) practice and firm performance: An international evidence. Journal of Business Economics and Management, 23, 218–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, D., & Montgomery, H. (2025). The financial benefits of going green: An analysis of bank performance and policy impact in China. Studies in Economics and Finance, 42(3), 553–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisodia, G., Joseph, A., & Dominic, J. (2022). Whether corporate green bonds act as armour during crises? Evidence from a natural experiment. International Journal of Managerial Finance, 18(4), 701–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnov, S. D. (2022). The efficiency of environmental project financing with green bonds in the energy sector: Evidence from EU countries. Journal of Corporate Finance Research, 16, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, T., & Lin, B. (2025). Modeling investor responses to green bond issuance: Multidimensional perspectives and evidence from China. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 72, 651–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, T., Shi, Y., & Lin, B. (2023). Label or lever? The role of reputable underwriters in Chinese green bond financing. Finance Research Letters, 53, 103612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramani, R. V. (2012). Fixed income securities—theory. In R. V. Subramani (Ed.), Accounting for investments: Fixed income securities and interest rate derivatives—A practitioner’s guide, Volume 2. Wiley. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghizadeh-Hesary, F., Yoshino, N., & Phoumin, H. (2021). Analyzing the characteristics of green bond markets to facilitate green finance in the Post-COVID-19 world. Sustainability, 13, 5719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X., Dong, H., Liu, Y., Su, X., & Li, Z. (2022). Green bonds and corporate performance: A potential way to achieve green recovery. Renewable Energy, 200, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y., Wang, B., Pan, N., & Li, Z. (2023). The impact of environmental information disclosure on the cost of green bond: Evidence from China. Energy Economics, 126, 107008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A., & Agarwal, R. (2020). A study of green bond market in india: A critical review (Vol. 804). IOP Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. (2023). An empirical study on the stock market reaction to corporate green bond issuance in China. Highlights in Business Economics and Management, 10, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Duan, L., & Zeng, H. (2023). Green bond financing, environmental regulation, and long-term value orientation: Evidence from Chinese-listed companies. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30(59), 123335–123350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P., & Lu, Z. (2024). The effect of collateral-based monetary policy on green finance: Evidence from China. Oeconomia Copernicana, 15(4), 1223–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicaksono, K. A. (2024). The impact of green bond issuance and ESG performance on firm profitability: Evidence from listed companies in China, South Korea and Thailand. Cakrawala Repositori IMWI, 6(6), 2604–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, B., & Jing, H. (2022). Research on the impact of green bond issuance on the stock price of listed companies. Kybernetes, 51(4), 1478–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X., Li, J., & Yin, D. (2023). How and why does green bond have lower issuance interest rate? Evidence from China. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 60(1), 2207702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H. (2021). Capital supply and financial risk of enterprises. In Proceedings of the 2021 6th international conference on social sciences and economic development (ICSSED 2021) (pp. 850–854). Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research. Atlantis Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeow, K., & Ng, S. (2021). The impact of green bonds on corporate environmental and financial performance. Managerial Finance, 47(10), 1486–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H., Burlacu, R., & Enjolras, G. (2024). Green bond issuances: A promising signal or a deceptive opportunity? Business & Society, 64(2), 218–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R., Li, Y., & Liu, Y. (2021). Green bond issuances and corporate cost of capital. SSRN Working Paper. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Li, Y., & Chen, X. (2024). Does green bond issuance affect stock price crash risk? Evidence from China. Finance Research Letters, 60, 104908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J., Jiang, Y., Cui, Y., & Shen, Y. (2023). Green bond issuance and corporate ESG performance: Steps toward green and low-carbon development. Research in International Business and Finance, 66, 102007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D., & Kythreotis, A. (2024). Why issue green bonds? Examining their dual impact on environmental protection and economic benefits. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X., & Cui, Y. (2019). Green bonds, corporate performance, and corporate social responsibility. Sustainability, 11, 6881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z., Tian, Y., Zhao, X., & Huang, H. (2025). Green washing, green bond issuance, and the pricing of carbon risk: Evidence from a-share listed companies. Sustainability, 17(11), 4788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Scopus |

| Period | 2019–2025 |

| Document type | Article; Review |

| Language | English |

| Fields | Titles, abstracts and keywords |

| Descriptors | (TITLE-ABS-KEY((“green bond*” OR “greenbond*” OR “conventional bond*” OR “vanilla bond*”) AND (“performance finance” OR “performance”)) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY((“green bond*” OR “greenbond*” OR “conventional bond*” OR “vanilla bond*”) AND (“cost of debt” OR “Greenium” OR “green premium”))) AND PUBYEAR > 2018 AND PUBYEAR < 2026 AND (LIMIT-TO(DOCTYPE, “ar”) OR LIMIT-TO(DOCTYPE, “re”)) |

| Rating | Meaning | Encryption |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Type of Study | A—Empirical; B—Theoretical; C—Systematic Review; D—Case Study |

| 2 | Type of Approach | A—Quantitative; B—Qualitative; C—Mixed |

| 3 | Main Research Topic | A—Green Bonds; B—Conventional Bonds; C—Financial Performance; D—Cost of Debt; E—Comparison with Conventional Bonds; F—Other |

| 4 | Analytical Method/Technique | A—Econometric/Regression; B—Propensity Score Matching; C—Difference-in-Differences; D—Panel Analysis; E—Event Study; F—Other |

| 5 | Data Source | A—Financial Statements; B—Annual Reports/reference forms; C—S&P Capital IQ/Refinitiv LSEG/Bloomberg; D—Other |

| 6 | Industry/Sector | A—All; B—Energy; C—High-Emission Industries (e.g., heavy industry); D—Financial Services; E—Infrastructure; F—Other |

| 7 | Country/Region | A—Global; B—Developed Markets; C—Emerging Markets; D—Europe; E—Latin America; F—Asia; G—Other |

| 8 | Performance Indicator/Key Variable | A—ROE; B—ROA; C—EBITDA; D—Stock Price; E—Cost of Debt; F—Credit Rating; G—ESG Rating; H—Multiples (e.g., A/B, C/E); I—Other |

| 9 | Comparison Scheme | A—Green Bond Issuers vs. Non-Issuers; B—Green Bonds vs. Conventional Bonds; C—Pre vs. Post-Issuance; D—Other |

| 10 | Bias Control/Robustness Technique | A—PSM; B—DID; C—Generalized Matching; D—Instrumental Variables; E—Placebo Tests; F—Other |

| Author | Study | Type | Research Topic | Technique | Data Source | Sector | Country/Region | Performance Indicator | Comparision Scheme | Bias Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Devine and McCollum (2022) | 1A | 2A | 3A,C,D | 4A | 5D | 6E | 7B | 8E,G | 9A | 10E,F |

| Grishunin et al. (2023) | 1A | 2A | 3A,D,E | 4A,D | 5C | 6C,D,F | 7D | 8E,F,G | 9B | 10F |

| Ahmad and Mokhchy (2023) | 1A | 2A | 3A,C | 4A | 5A,B,D | 6B,C | 7C | 8B,F,G | 9D | 10D,F |

| Lebelle et al. (2020) | 1A | 2A | 3A,C,E | 4A,E | 5C | 6A | 7A,B,C | 8B,D,F | 9C,D | 10F |

| Glavas (2023) | 1A | 2A | 3A,C | 4A,B | 5C | 6A | 7A | 8A,B,F,G | 9A,C | 10A,F |

| Fan et al. (2023) | 1A | 2A | 3A,C,F | 4A,E | 5D | 6A | 7C,F | 8D,G | 9B,D | 10F |

| Badía et al. (2024) | 1A | 2A | 3A,C,F | 4A,B | 5C | 6A | 7A | 8D,G | 9A,D | 10A,F |

| Nanayakkara and Colombage (2021) | 1A | 2A | 3A,D,F | 4A | 5C,D | 6A | 7B,C | 8E,G | 9D | 10F |

| Y. Zhang et al. (2024) | 1A | 2A | 3A,C,D,F | 4A,C | 5D | 6A,C | 7C,F | 8D,F,G | 9A,D | 10A,B,E,F |

| Kodiyatt et al. (2024) | 1A | 2A | 3A,C | 4A,E | 5C,D | 6B,D,E | 7C,F | 8D | 9C,D | 10F |

| Aleknevičiene et al. (2025) | 1A | 2A | 3A,D,E | 4A,B,F | 5C,D | 6A,D,F | 7D | 8E,F | 9B,D | 10F |

| Löffler et al. (2021) | 1A | 2A | 3A,D,E | 4A,B,F | 5C | 6C,D,E,F | 7A | 8E,F,G | 9B,C,D | 10A,F |

| Nurvita et al. (2024) | 1A | 2A | 3A,D,E | 4A,F | 5C,D | 6B,C,D,E,F | 7C,F | 8E,F,G | 9B,D | 10C,F |

| Abhilash et al. (2024) | 1A | 2A | 3A,D,F | 4A,F | 5C,D | 6B,C,D,E,F | 7C,E,F | 8E,F,G | 9D | 10F |

| H. Wang et al. (2023) | 1A | 2A | 3A,C,F | 4A,C,F | 5C,D | 6C,F | 7C,F | 8B,F,G | 9A,D | 10A,B,C,D,E,F |

| Flammer (2020) | 1A | 2A | 3A,C,D | 4A,E | 5C,D | 6A | 7A,B,C | 8D,E,F,G | 9B,C | 10A,E,F |

| Fang et al. (2023) | 1A | 2A | 3A,D,F | 4A,C,F | 5D | 6A,D,F | 7C,F | 8E,F,G | 9A,C,D | 10B,E,F |

| Tan et al. (2022) | 1A | 2A | 3A,C,F | 4A,C,F | 5C,D | 6C,F | 7C,F | 8A,B,F,G | 9A,D | 10B,E,F |

| Khurram et al. (2023) | 1A | 2A | 3A,C,F | 4A,C,F | 5D | 6B,C,F | 7C,F | 8A,B,F,G | 9A,C | 10B,E,F |

| X. Zhou and Cui (2019) | 1A | 2A | 3A,C,F | 4A,E,F | 5D | 6A,D,F | 7C,F | 8A,B,D,F,G | 9A,C,D | 10A,B,E,F |

| Jiang et al. (2022) | 1A | 2A | 3A,C,D,F | 4A,B,C,D,F | 5D | 6A | 7C,F | 8A,E,F,G | 9A,C | 10A,B,D,E,F |

| Lichtenberger et al. (2022) | 1A | 2A | 3A,C,D,E,F | 4A,F | 5C,D | 6B,D,F | 7B,D | 8E,G | 9B,D | 10F |

| Macaire and Naef (2023) | 1A | 2A | 3A,D,F | 4A,C,F | 5C | 6D | 7C,F | 8E,F,G | 9A,C | 10B,E,F |

| X. Huang et al. (2025) | 1A | 2A | 3A,C,F | 4A,C,E,F | 5D | 6A,C | 7C,F | 8B,D,F,G | 9A,C,D | 10A,B,E,F |

| Hu et al. (2022) | 1A | 2A | 3A,D,F | 4A,B,F | 5D | 6A,C,F | 7C,F | 8B,F | 9A,D | 10A,E,F |

| Zhu et al. (2025) | 1A | 2A | 3A,B,D,F | 4A,B,C,D,F | 5D | 6A,B | 7C,F | 8A,D,E,F,G | 9A,B,C,D | 10A,E,F |

| Xu et al. (2023) | 1A | 2A | 3A,D,E | 4A,B,F | 5D | 6A,C,E | 7C,F | 8E,F,G | 9B,D | 10A,F |

| Y. Li et al. (2023) | 1A | 2A | 3A,C,F | 4A,B,C,F | 5D | 6F | 7C,F | 8B,F,G | 9A,C,D | 10A,B,E,F |

| Hu et al. (2024) | 1A | 2A | 3A,D,F | 4A,D,F | 5D | 6A,B,C,E,F | 7C,F | 8E,F,G | 9D | 10D,F |

| P. Ge et al. (2024) | 1A | 2A | 3A,C,D,F | 4A,B,C,F | 5C,D | 6A,C | 7C,F | 8I | 9A,C,D | 10A,B,E,F |

| Hong et al. (2025) | 1A | 2A | 3A,C,D,E | 4A,E | 5C,D | 6A | 7A | 8D,E,G | 9B,C | 10F |

| Dutordoir et al. (2024) | 1A | 2A | 3A,C,F | 4A,E | 5C,D | 6A | 7A,B,C | 8A,B,D,F,G | 9A,C,D | 10A,E,F |

| Kim and Ahn (2022) | 1A | 2A | 3A,D,E | 4A,B | 5D | 6D,F | 7C,F | 8E,F,I | 9B,D | 10A,E,F |

| Su et al. (2023) | 1A | 2A | 3A,D,F | 4A,B,D,F | 5D | 6A,C,F | 7C,F | 8F,I | 9D | 10A,D,F |

| Makpotche et al. (2024) | 1A | 2A | 3A,C,E | 4A,E | 5C,D | 6A | 7A,B,C | 8A,B,G | 9A,C,D | 10A,E,F |

| Su and Lin (2025) | 1A | 2A | 3A,C,F | 4A,D,E | 5D | 6A | 7C,F | 8D,I | 9C,D | 10F |

| Cao et al. (2021) | 1A | 2A | 3A,D,F | 4A,D,F | 5D | 6D | 7C,F | 8E,F,I | 9B,D | 10B,D,F |

| Lian and Hou (2024) | 1A | 2A | 3A,D,F | 4A,B,D | 5D | 6A,D | 7C,F | 8E,I | 9B,D | 10A,F |

| Xi and Jing (2022) | 1A | 2A | 3A,C,F | 4A,D,E | 5D | 6A,C,D | 7C,F | 8D,E,F,I | 9A,B,C,D | 10E,F |

| C. Huang et al. (2023) | 1A | 2A | 3A,D,F | 4A,B,F | 5C,D | 6A,D,F | 7A | 8E,F,G | 9B | 10A,F |

| Aleknevičiene and Vilutytė (2024) | 1A | 2A | 3A,C,F | 4A,E,F | 5C | 6A,C,D | 7B,D | 8A,D,F,G | 9C,D | 10F |

| Arhinful et al. (2025) | 1A | 2A | 3A,E,F | 4A,D | 5C | 6A | 7A,E | 8A,E,F,H | 9B,D | 10C,E,F |

| Chan and Liao (2025) | 1A | 2C | 3A,D,E,F | 4A,F | 5C,D | 6A | 7A | 8E,I | 9B | 10F |

| P. Wang and Lu (2024) | 1A | 2A | 3A,D,E,F | 4A,B,C,D,E,F | 5D | 6A | 7C,F | 8E,G | 9A,B,C | 10A,B,E,F |

| Sheng and Montgomery (2025) | 1A | 2A | 3A,C,D,E,F | 4A,B,C,D | 5D | 6D | 7C,F | 8A,B,E,I | 9A,B,C | 10A,B,F |

| Tang et al. (2023) | 1A | 2A | 3A,D,F | 4A,F | 5D | 6A,D | 7C,F | 8E,G | 9B,C,D | 10A,D,F |

| Yeow and Ng (2021) | 1A | 2A | 3A,C,E,F | 4A,B,C | 5B,D | 6A | 7A | 8B,I | 9A,C | 10A,B,F |

| Muhammad et al. (2025) | 1A | 2A | 3A,C,D,F | 4A,B,C,D | 5C | 6A | 7A | 8E,I | 9A,C | 10A,B,E,F |

| Chang et al. (2021) | 1A | 2A | 3A,D,E,F | 4A,D,F | 5D | 6A | 7C,F | 8E,G | 9B,D | 10F |

| Hyun et al. (2023) | 1A | 2A | 3A,D,F | 4A,F | 5C | 6A | 7A | 8E,I | 9D | 10F |

| Baker et al. (2022) | 1C | 2B | 3A,D,E,F | 4F | 5C,D | 6A,F | 7B | 8E,G | 9B,D | 10F |

| Petreski et al. (2025) | 1A | 2A | 3A,C,D,E,F | 4A,C,D,F | 5C | 6F | 7B,D | 8E,G | 9B,C,D | 10B,D,F |

| Baldi and Pandimiglio (2022) | 1A | 2A | 3A,D,E,F | 4A,F | 5C,D | 6A | 7A | 8E,G | 9B,D | 10F |

| Jin and Zhang (2023) | 1A | 2A | 3A,C,F | 4A,E | 5D | 6A,D | 7C,F | 8D | 9C,D | 10F |

| Dorfleitner et al. (2022) | 1A | 2A | 3A,D,E,F | 4A,D | 5C,D | 6A | 7A | 8E,I | 9B,D | 10F |

| Fandella and Cociancich (2024) | 1A | 2A | 3A,D,E,F | 4A,D,F | 5C | 6A,D | 7B,D | 8E,I | 9B | 10F |

| Q. Li et al. (2022) | 1A | 2A | 3A,D,E,F | 4A,B,F | 5D | 6A | 7C,F | 8E,I | 9B,D | 10A,F |

| Sisodia et al. (2022) | 1A | 2A | 3A,C,F | 4A,B,F | 5C,D | 6A | 7A | 8D,I | 9A,D | 10A,F |

| D. Zhou and Kythreotis (2024) | 1A | 2A | 3A,C,D,E,F | 4A,C,F | 5C | 6A | 7A | 8E,I | 9B,D | 10B,F |

| Year | Number of Articles |

|---|---|

| 2019 | 1 |

| 2020 | 1 |

| 2021 | 5 |

| 2022 | 12 |

| 2023 | 15 |

| 2024 | 15 |

| 2025 | 10 |

| Country/Region | Number of Articles |

|---|---|

| China | 25 |

| France | 3 |

| India | 3 |

| United States | 2 |

| Spain | 2 |

| United Kingdom | 2 |

| Canada | 2 |

| South Korea | 2 |

| Others | 18 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodrigues Loiola, R.; Kimura, H.; Melo Souza, L.d. Sustainable Finance, Green Bonds and Financial Performance—A Literature Review. Int. J. Financial Stud. 2025, 13, 233. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs13040233

Rodrigues Loiola R, Kimura H, Melo Souza Ld. Sustainable Finance, Green Bonds and Financial Performance—A Literature Review. International Journal of Financial Studies. 2025; 13(4):233. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs13040233

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodrigues Loiola, Roberto, Herbert Kimura, and Ludmila de Melo Souza. 2025. "Sustainable Finance, Green Bonds and Financial Performance—A Literature Review" International Journal of Financial Studies 13, no. 4: 233. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs13040233

APA StyleRodrigues Loiola, R., Kimura, H., & Melo Souza, L. d. (2025). Sustainable Finance, Green Bonds and Financial Performance—A Literature Review. International Journal of Financial Studies, 13(4), 233. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs13040233