Quantile Connectedness Between Stock Market Development and Macroeconomic Factors for Emerging African Economies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Theoretical Literature Review

2.2. Empirical Literature Review

2.3. Hypothesis Development

- Economic growth

- Inflation rate

- Exchange rate

- Interest rate

- Money supply

3. Data and Research Methodology

3.1. Data and Descriptive Statistics Summary

3.2. Research Methodology

- The total directional connectedness with respect to others2:

- The total directional connectedness originating from others3:

- The overall net total directional connectedness captures the difference between the total directional connectedness to others and from others4:NETi (H) = (H) − (H)

- The computation of the overall Total Connectedness Index (TCI), which evaluates the degree of interconnectedness within the network. A higher value of TCI signifies increased market risk, while a lower value indicates the opposite:

4. Empirical Results

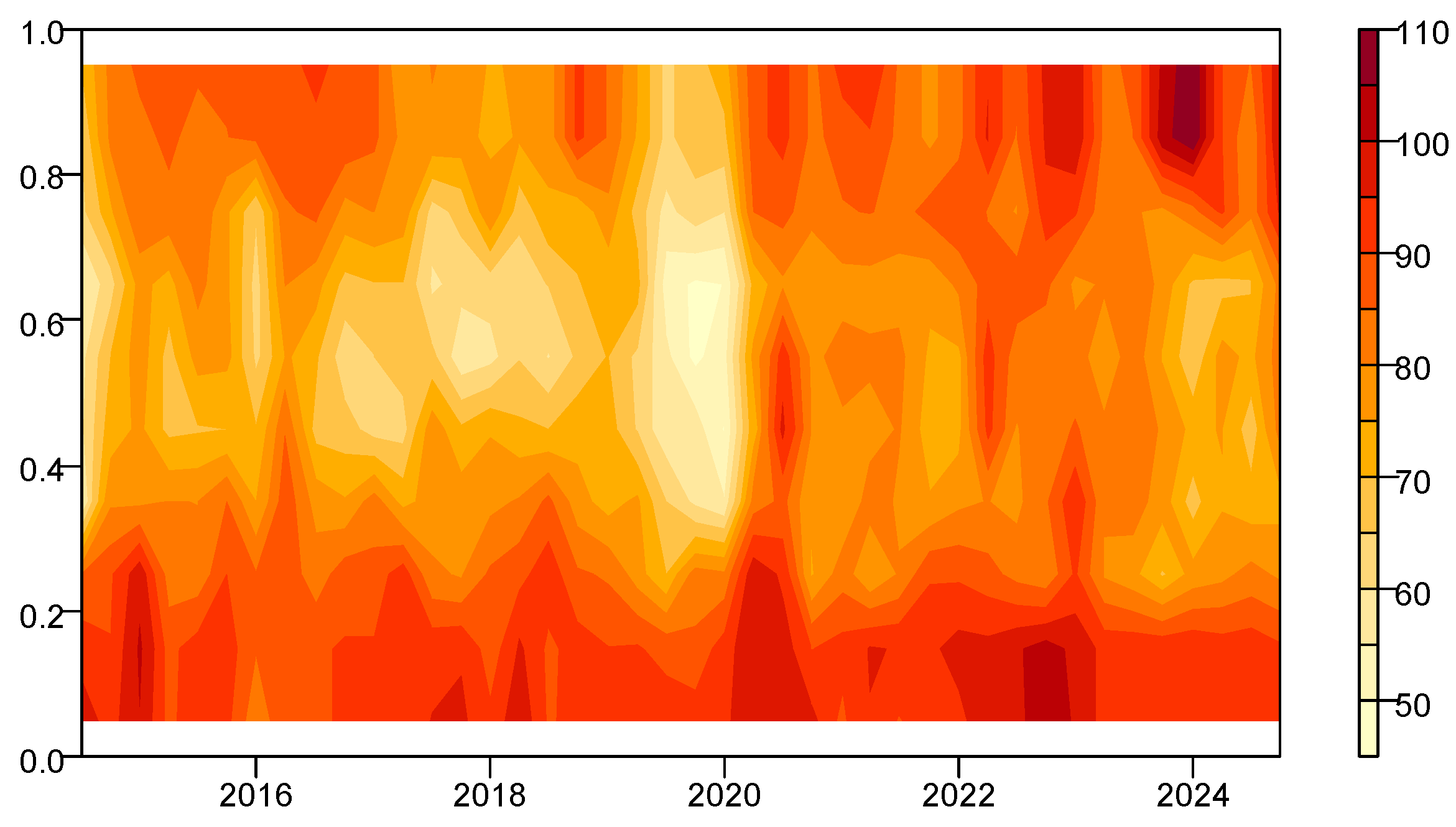

4.1. Empirical Results for Morocco

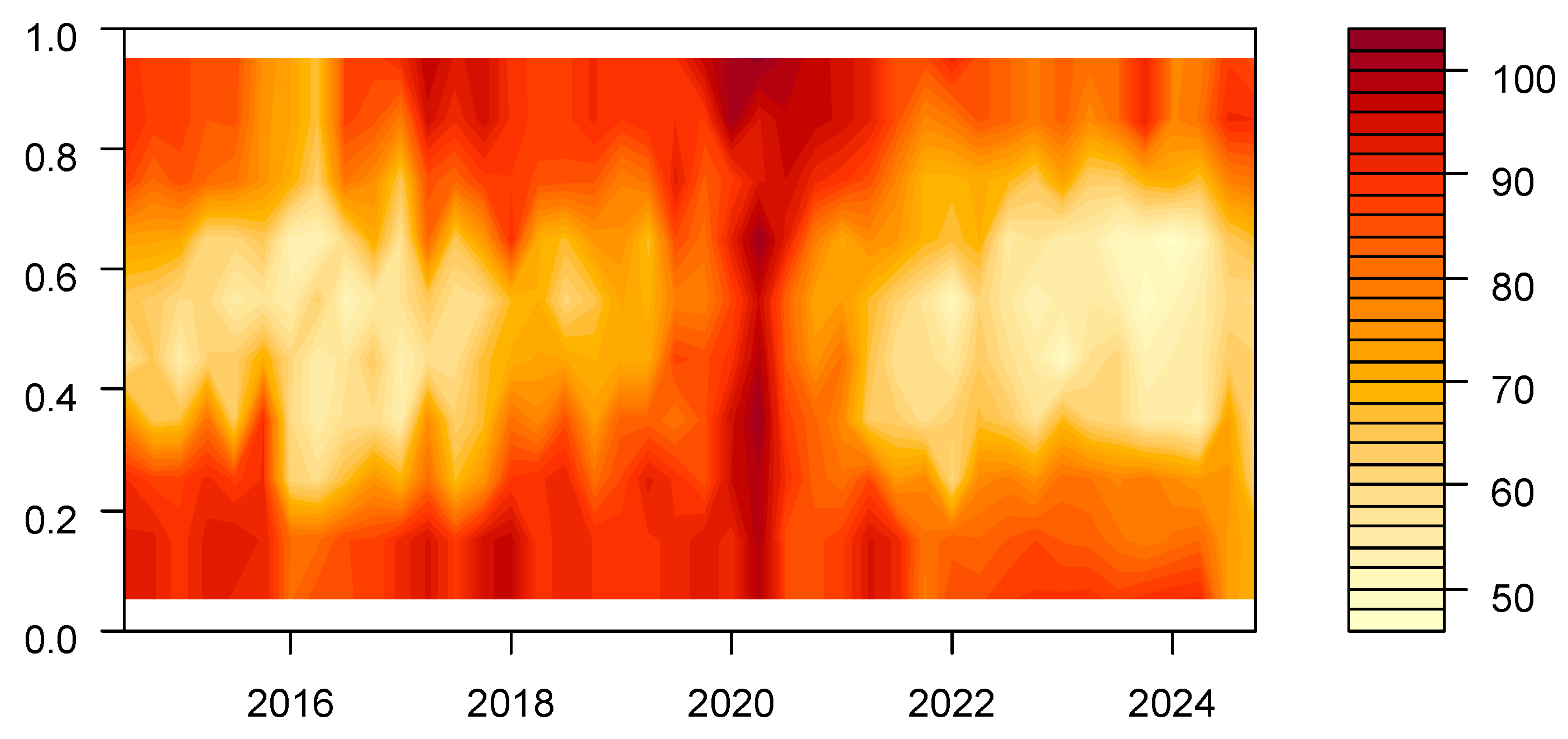

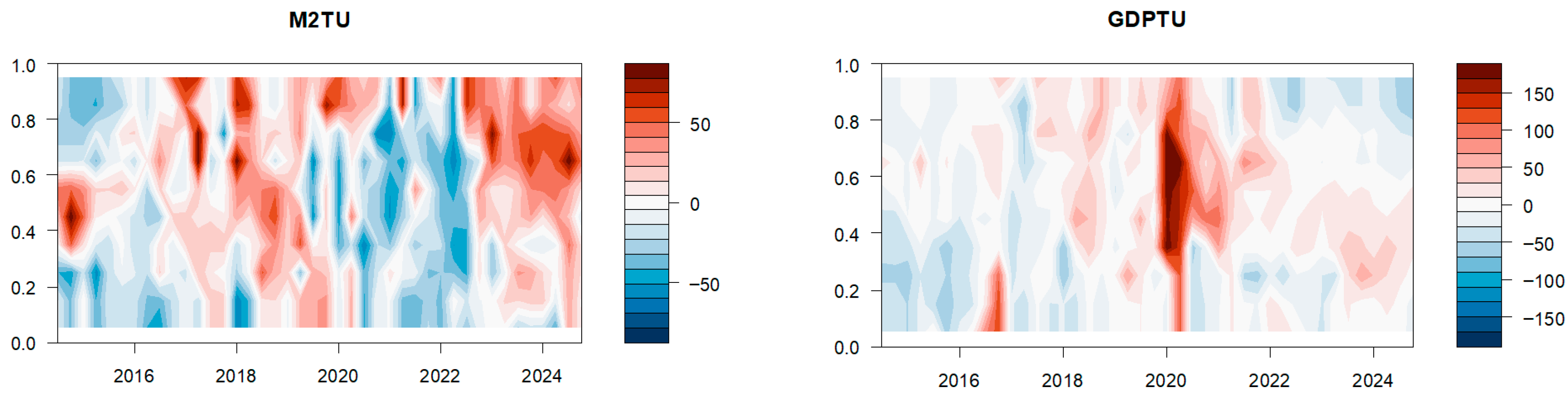

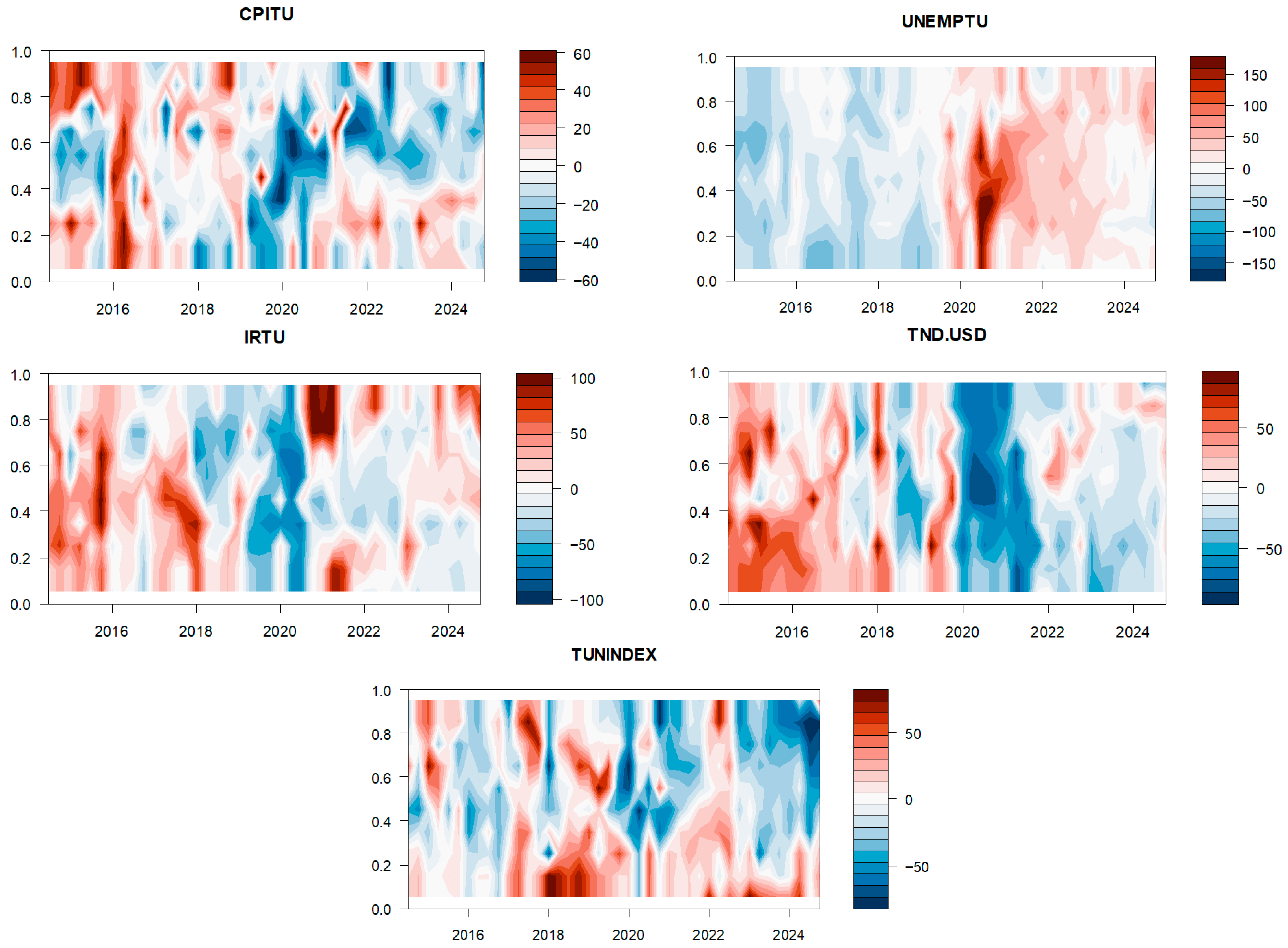

4.2. Empirical Results for Tunisia

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| APT | Arbitrage Pricing Theory |

| ARDL | AutoRegressive Distributed Lag |

| EMH | Efficient Market Hypothesis |

| EPU | Economic Policy Uncertainty |

| FDI | foreign direct investment |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| GFEVD | Generalized Forecast Error Variance Decomposition |

| GMM | Generalized Method of Moments |

| MENA | Middle East and North Africa |

| MPT | Modern Portfolio Theory |

| MS | money supply |

| QVAR | Quantile Vector Autoregression |

| TCI | Total Connectedness Index |

| VAR | Vector Auto-Regression |

| VECM | Vector Error Correction Model |

| 1 | M2 is a standard measure of money supply widely used in macroeconomic and financial studies, particularly in emerging markets, and, unlike broader aggregates such as M3 or M4, it is consistently available on a quarterly basis from the IMF and World Bank for both Morocco and Tunisia, ensuring comparability over our study period. |

| 2 | It assesses how much an impact in series i influences all other series j. |

| 3 | It quantifies the level of impact on series i caused by shocks in all other series j. |

| 4 | This disparity can be interpreted as the net impact of series i on the predefined network. |

| 5 | All variables are transformed to first differences to ensure stationarity. This specification models connectedness in growth rates, emphasizing short- to medium-term shock transmission rather than long-run co-movements, which aligns with the focus on financial market risk and tail events. |

References

- Abbass, K., Sharif, A., Song, H., Ali, M. T., Khan, F., & Amin, N. (2022). Do geopolitical oil price risk, global macroeconomic fundamentals relate Islamic and conventional stock market? Empirical evidence from QARDL approach. Resources Policy, 77, 102730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abugri, B. A. (2008). Empirical relationship between macroeconomic volatility and stock returns: Evidence from Latin American markets. International Review of Financial Analysis, 17(2), 396–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adoms, F. U., Yua, H., Okaro, C. S., & Ogbonna, K. S. (2020). Capital market and economic development: A comparative study of three Sub-Saharan African emerging economies. American Journal of Industrial and Business Management, 10(5), 963–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, A., & Reimers, M. (2022). Does the introduction of stock exchange markets boost economic growth in African countries? Journal of Comparative Economics, 50(2), 627–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S. (2008). Aggregate economic variables and stock markets in India. International Research Journal of Finance and Economics, 14, 141–164. [Google Scholar]

- Akanbi, A. (2025). Macroeconomic factors and stock market performance based on new evidence: A case study from Nigeria. Asian Journal of Economics, Business and Accounting, 25(2), 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akash, C., Prashant, D., & Mohammed, J. N. (2023). Macroeconomic determinants of stock market development: A systematic literature review. Jurnal Multidisiplin Madani, 3(8), 1800–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Awad, M., & Harb, N. (2005). Financial development and economic growth in the Middle East. Applied Financial Economics, 15(15), 1041–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jafari, M. K., Salameh, R. M., & Habbash, M. R. (2011). Investigating the relationship between stock market returns and macroeconomic variables: Evidence from developed and emerging markets. International Research Journal of Finance and Economics, 79, 6–30. [Google Scholar]

- Alloul, F., & Ferrouhi, E. M. (2024). Macroeconomic indicators and stock market returns: A comparative analysis. International Journal of Revenue Management, 14(4), 333–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, T., Greenwood-Nimmo, M., & Shin, Y. (2022). Quantile connectedness: Modeling tail behavior in the topology of financial networks. Management Science, 68(4), 2401–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anser, M. K., Khan, M. A., Zaman, K., Nassani, A. A., Askar, S. E., Abro, M. M. Q., & Kabbani, A. (2021). Financial development during COVID-19 pandemic: The role of coronavirus testing and functional labs. Financial Innovation, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attari, M. I. J., & Javed, A. Y. (2013). Inflation, Economic growth and government expenditure of Pakistan: 1980-2010. Procedia Economics and Finance, 5, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayunku, P. E., & Etale, L. M. (2015). Determinants of stock market development in Nigeria: A cointegration approach. Advances in Research, 3(4), 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcilar, M., Elsayed, A. H., & Hammoudeh, S. (2023). Financial connectedness and risk transmission among MENA countries: Evidence from connectedness network and clustering analysis. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 82, 101656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, C. (2024). Attractiveness of African stock markets for foreign investors: An analytical perspective. Journal of Securities Operations & Custody, 16(4), 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bencivenga, V. R., & Smith, B. D. (1991). Financial intermediation and endogenous growth. The Review of Economic Studies, 58(2), 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bencivenga, V. R., Smith, B. D., & Starr, R. M. (1996). Equity markets, transaction costs, and capital accumulation: An illustration. The World Bank Economic Review, 10(2), 241–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Naceur, S., & Ghazouani, S. (2007). Stock markets, banks, and economic growth: Empirical evidence from the MENA region. Research in International Business and Finance, 21(2), 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, B., & Mukherjee, J. (2006). Indian stock price movement and the Macroeconomic context—A time series analysis. Journal of International Business and Economics, 5, 167–181. [Google Scholar]

- Bhute, A. (2022). Financial analytics for interlinking stock market and macroeconomic performance—Post financial crisis 2008. Model Assisted Statistics and Applications, 17(4), 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, F., Jensen, M. C., & Scholes, M. (1972). The capital asset pricing model: Some empirical tests. In M. C. Jensen (Ed.), Studies in the theory of capital markets (pp. 79–121). Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Bonga, W. G., Ozili, P. K., & Choga, I. (2025). Stock market development determinants in Africa: A review of literature. International Journal of Economics, Finance and Management Sciences, 13(2), 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouri, E., Demirer, R., Gupta, R., & Nel, J. (2021). COVID-19 pandemic and investor herding in international stock markets. Risks, 9(9), 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, J. H., & Smith, B. D. (1998). The evolution of debt and equity markets in economic development. Economic Theory, 12(3), 519–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceylan, I. E., & Ceylan, F. (2023). Symmetric and asymmetric effects of exchange rate changes on stock prices in fragile five economies: Analysis of the global crisis and pandemic period. The Journal of Economic Integration, 38(4), 646–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charfeddine, L., & Khediri, K. B. (2016). Financial development and environmental quality in UAE: Cointegration with structural breaks. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 55, 1322–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatziantoniou, I., Gabauer, D., & Stenfors, A. (2021). Interest rate swaps and the transmission mechanism of monetary policy: A quantile connectedness approach. Economics Letters, 204, 109891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavleishvili, S., & Manganelli, S. (2024). Forecasting and stress testing with quantile vector autoregression. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 39(1), 66–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, T. H. N., Balli, F., Balli, H. O., Gabauer, D., & Nguyen, T. T. H. (2024). Sectoral uncertainty spillovers in emerging markets: A quantile time–frequency connectedness approach. International Review of Economics & Finance, 93(Part B), 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dave, H., & Akongwale, S. (2024). Understanding the determinants of the development of the green bond market in South Africa. South African Journal of Business Management, 55(1), a4065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Levine, R. (1996). Stock market development and financial intermediaries: Stylized facts. The World Bank Economic Review, 10(2), 291–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diebold, F. X., & Yilmaz, K. (2012). Better to give than to receive: Predictive directional measurement of volatility spillovers. International Journal of Forecasting, 28(1), 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diebold, F. X., & Yilmaz, K. (2014). On the network topology of variance decompositions: Measuring the connectedness of financial firms. Journal of Econometrics, 182(1), 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Distia, M. (2023). The interplay between financial markets and economic growth. Advances in Economics & Financial Studies, 1(3), 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drama, B. G. H. (2025). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic and oil price shock on BRVM-C stock market. Journal of Finance and Economics, 13(1), 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Nader, H. M., & Alraimony, A. D. (2013). The macroeconomic determinants of stock market development in Jordan. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 5(6), 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Oubani, A. (2024). Quantile connectedness between social network sentiment and sustainability index volatility: Evidence from the Moroccan financial market. Economics and Business Review, 10(3), 163–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engle, R. F., Ghysels, E., & Sohn, B. (2013). Stock market volatility and macroeconomic fundamentals. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 95(3), 776–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabozzi, F. J., Focardi, S., Ponta, L., Rivoire, M., & Mazza, D. (2022). The economic theory of qualitative green growth. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 61, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagbemi, F., & Ajibike, J. O. (2022). West African emerging economies: Comparative insights on Ghana’s and Nigeria’s stock market development. American Journal of Economics and Business Administration, 14(1), 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E. F. (1970). Efficient capital markets: A review of theory and empirical work. The Journal of Finance, 25(2), 383–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E. F. (1981). Stock returns, real activity, inflation, and money. The American Economic Review, 71(4), 545–565. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, M., & Schwartz, A. J. (1963). Money and business cycles. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 45(1), 32–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabauer, D., & Stenfors, A. (2024). Quantile-on-quantile connectedness measures: Evidence from the US treasury yield curve. Finance Research Letters, 60, 104852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabhane, D., & Radhakrishnan, G. V. (2025). Exploring the interdependence of financial markets and economic growth: A global perspective. European Economic Letters (EEL), 15(1), 987–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavin, M. (1989). The stock market and exchange rate dynamics. Journal of International Money and Finance, 8(2), 181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geske, R., & Roll, R. (1983). The fiscal and monetary linkage between stock returns and inflation. The Journal of Finance, 38(1), 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z., Chen, Y., Zhang, H., & Chen, F. (2024). Tail risk connectedness in the Carbon-Finance nexus: Evidence from a quantile spillover approach in China. Finance Research Letters, 67(Part B), 105803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, J., & Jovanovic, B. (1990). Financial development, growth, and the distribution of income. The Journal of Political Economy, 98(5), 1076–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, J., & Smith, B. D. (1997). Financial markets in development, and the development of financial markets. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 21(1), 145–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A., & Nasir, Z. M. (2008). Macroeconomic factors and equity prices: An empirical investigation by using ARDL approach. The Pakistan Development Review, 47(4), 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, J. R. (1935). Annual survey of economic theory: The theory of monopoly. Econometrica, 3(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirota, S. (2023). Money supply, opinion dispersion, and stock prices. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 212, 1286–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humpe, A., McMillan, D. G., & Schöttl, A. (2025). Macroeconomic determinants of the stock market: A comparative study of Anglosphere and BRICS. Finance Research Letters, 75, 106869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igwilo, J. I., & Sibindi, A. B. (2021). ICT adoption and stock market development in Africa: An application of the panel ARDL bounds testing procedure. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 14(12), 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issahaku, H., Ustarz, Y., & Domanban, P. B. (2013). Macroeconomic variables and stock market returns in Ghana: Any causal link? Asian Economic and Financial Review, 3(8), 1044–1062. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, X., Chang, B. H., Han, C., & Uddin, M. A. (2025). The tail connectedness among conventional, religious, and sustainable investments: An empirical evidence from neural network quantile regression approach. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 30(2), 1124–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamasa, K., Owusu, L., & Nkansah Asante, G. (2023). Stock market growth in Ghana: Do financial sector reforms matter? Cogent Business & Management, 10(1), 2180843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayani, U., Ullah, M., Aysan, A. F., Nazir, S., & Frempong, J. (2024). Quantile connectedness among digital assets, traditional assets, and renewable energy prices during extreme economic crisis. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 208, 123635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keswani, S., Puri, V., & Jha, R. (2024). Relationship among macroeconomic factors and stock prices: Cointegration approach from the Indian stock market. Cogent Economics & Finance, 12(1), 2355017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R. G., & Levine, R. (1993). Finance and growth: Schumpeter might be right. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 108(3), 717–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korsah, D., & Mensah, L. (2024). Geopolitical risk, economic policy uncertainty, financial stress and stock returns nexus: Evidence from African stock markets. Journal of Capital Markets Studies, 8(1), 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A., Parihar, M., Bansal, S., Chavan, S., Kotadia, S., & Shankar, S. (2022). Computing causality between Macro-economic Indicators and Indian financial markets. In A. M. A. Musleh Al-Sartawi (Ed.), Artificial intelligence for sustainable finance and sustainable technology (Proceedings of ICGER 2021): Lecture notes in networks and systems (vol. 238, pp. 112–121). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtoglu, B., & Durusu-Ciftci, D. (2024). Identifying the nexus between financial stability and economic growth: The role of stability indicators. Journal of Financial Economic Policy, 16(2), 226–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laichena, K. E., & Obwogi, T. N. (2015). Effects of macroeconomic variables on stock returns in the East African Community stock exchange market. International Journal of Education and Research, 3(10), 305–320. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, R., & Zervos, S. (1998). Stock markets, banks, and economic growth. The American Economic Review, 88(3), 537–558. [Google Scholar]

- Lintner, J. (1965). The valuation of risk assets and the selection of risky investments in stock portfolios and capital budgets. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 47(1), 13–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, G.-D., Marcelin, I., Bassène, T., & Lo, A. (2024). Connectedness and risk spillovers among sub-saharan Africa and MENA equity markets. Emerging Markets Review, 63, 101193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensi, W., Vo, X. V., & Kang, S. H. (2023). Quantile spillovers and connectedness analysis between oil and African stock markets. Economic Analysis and Policy, 78, 60–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, A., Effah, N. A. A., Joel, T. N., & Nkwantabisa, A. O. (2021). Stock market development, financial deepening and economic growth in Africa. Journal of Financial Risk Management, 10(1), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlambo, C. (2022). The impact of international portfolio investment on economic growth: The case of selected African states. International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science, 11(10), 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, H. M. (1993). Causality of interest rate, exchange rate and stock prices at stock market open and close in Hong Kong. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 10, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molefhi, K. (2021). The impact of macroeconomic variables on capital market development in Botswana’s economy. African Journal of Economic Review, 9(2), 204–222. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, T. K., & Naka, A. (1995). Dynamic relations between macroeconomic variables and the Japanese stock market: An application of a vector error correction model. The Journal of Financial Research, 18(2), 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muradoglu, G., Taskin, F., & Bigan, I. (2000). Causality between Stock Returns and Macroeconomic Variables in Emerging Markets. Russian & East European Finance and Trade, 36(6), 33–53. [Google Scholar]

- Neaime, S., & Gaysset, I. (2018). Financial inclusion and stability in MENA: Evidence from poverty and inequality. Finance Research Letters, 24, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obstfeld, M. (1994). Risk-Taking, Global Diversification, and Growth. The American Economic Review, 84(5), 1310–1329. [Google Scholar]

- Okorie, I. E., Akpanta, A. C., Ohakwe, J., Chikezie, D. C., Onyemachi, C. U., & Ugwu, M. C. (2021). Modeling the relationships across nigeria inflation, exchange rate, and stock market returns and further analysis. Annals of Data Science, 8(2), 295–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongo, N. B. E., Mamadou, A. T., Atangana, Z. C. C., & Djam’Angai, L. (2024). What drives financial market growth in Africa? International Review of Financial Analysis, 91, 102990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osamwonyi, I. O., & Evbayiro-Osagie, E. I. (2012). The relationship between macroeconomic variables and stock market index in Nigeria. Journal of Economics, 3(1), 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, B., Panda, A. K., & Panda, P. (2023). Macroeconomic response to BRICS countries stock markets using panel VAR. Asia-Pacific Financial Markets, 30, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, H. T. (1980). Financial development and economic growth in underdeveloped countries. In Money and monetary policy in less developed countries, A survey of issues and evidence (pp. 37–54). Pergamon. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, H. H., & Shin, Y. (1998). Generalized impulse response analysis in linear multivariate models. Economics Letters, 58(1), 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J. (1979). The generalization of the general theory and other essays. Palgrave Macmillan London. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S. A. (1976). The arbitrage theory of capital asset pricing. Journal of Economic Theory, 13(3), 341–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, J. A. (2021). The theory of economic development. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Shahbaz, M., Rehman, I. U., & Afza, T. (2016). Macroeconomic determinants of stock market capitalization in an emerging market: Fresh evidence from cointegration with unknown structural breaks. Macroeconomics and Finance in Emerging Market Economies, 9(1), 75–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamalime, J. M., & Yohane, R. (2024). Breaking through limits: Exploring factors hampering growth in Zambia’s capital markets-Lusaka Securities Exchange perspective. International Journal of Learning and Development, 14(2), 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, A., Aloui, C., & Yarovaya, L. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic, oil prices, stock market, geopolitical risk and policy uncertainty nexus in the US economy: Fresh evidence from the wavelet-based approach. International Review of Financial Analysis, 70, 101496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, W. F. (1964). Capital asset prices: A theory of market equilibrium under conditions of risk. The Journal of Finance, 19(3), 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, F., Xiong, H., & Ji, M. (2025). Quantile connectedness between China’s new energy market and other key financial markets. Applied Economics, 57(26), 3525–3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiller, R. J. (1988). Portfolio insurance and other investor fashions as factors in the October 1987 stock market crash. NBER Macroeconomics Annual, 3, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solow, R. M. (1956). A contribution to the theory of economic growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 70(1), 65–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X., & He, J. (2024). Quantile connectedness among fintech, carbon future, and energy markets: Implications for hedging and investment strategies. Energy Economics, 139, 107904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A. K., Dam, M. M., Altıntaş, H., & Bekun, F. V. (2025). The dynamic connectedness between oil price shocks and emerging market economies stock markets: Evidence from new approaches. Energy Economics, 141, 108101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhunmwangho, M. (2022). Determinants of stock market volatility in Africa. African Journal of Economic Review, 10(2), 136–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S., Ullah, A., & Zaman, M. (2024). Nexus of governance, macroeconomic conditions, and financial stability of banks: A comparison of developed and emerging countries. Financial Innovation, 10(1), 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H., Qamruzzaman, M., & Kor, S. (2023). Nexus between green investment, fiscal policy, environmental tax, energy price, natural resources, and clean energy—A step towards sustainable development by fostering clean energy inclusion. Sustainability, 15(18), 13591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaya, O., Adenikinju, O., & Olayinka, H. A. (2024). African stock markets’ connectedness: Quantile VAR approach. Modern Finance, 2(1), 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yulfajar, A., Noor, G. M., & Putranto, R. S. (2025). The impact of financial market instability on economic growth and long-term investment. Advances in Economics & Financial Studies, 3(1), 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusoff, W. F. W., & Guima, I. J. (2015). Stock market development of Middle East and North Africa (MENA) Region. International Journal of Business and Economics Research, 4(3), 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, A., Gwadabe, M., & Ukashatu, A. Y. (2025). Key macroeconomic variables and stock market development in Nigeria: Evidence from Granger Causality Test. Journal of Accounting and Finance Research, 3(2), 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Methodology | Sample | Empirical Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmed (2008) | ARDL bounds testing approach | India | Bidirectional causality is detected between stock market development and GDP in the long-term. |

| Osamwonyi and Evbayiro-Osagie (2012) | ARDL bounds testing approach | Nigeria | Money supply and aggregate industrial production positively and significantly affect stock return, while exchange and inflation rates negatively affect stock return in the Nigerian stock exchange market. |

| El-Nader and Alraimony (2013) | VECM and variance decomposition | Jordan | Stock market development is positively affected by credit to the private sector, gross capital formation, money supply, total value traded and consumer price index. |

| Ayunku and Etale (2015) | Multiple regression model | Nigeria | High inflation and savings rate have a negative impact on the stock market development. |

| Laichena and Obwogi (2015) | Panel data | Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania | Strong association is detected between stock market development and the macroeconomic variables (interest rates, currency exchange rates, GDP, and inflation). |

| Shahbaz et al. (2016) | Vector Error Correction Model (VECM) approach | Pakistan | Inflation, economic growth, foreign direct investment (FDI), and financial development have a positive impact on the stock market development, while trade openness has a negative impact on the stock market development. |

| Ceylan and Ceylan (2023) | Panel ARDL | India, Indonesia, Brazil, South Africa, and Turkey | Exchange rate changes have both short- and long-term asymmetric and symmetric effects, pre- and post-crises. |

| Kamasa et al. (2023) | ARDL Cointegration approach | Ghana | Money supply and inflation rate have a negative impact on the stock market development, while FDI and interest rate have a positive impact on the stock market development. |

| Dang et al. (2024) | Quantile and time-frequency connectedness approaches | Emerging markets | The findings reveal: High total connectedness; large long-term spillovers; and consumer cyclicals strongest transmitter. |

| El Oubani (2024) | Quantile and frequency connectedness approaches | Morocco | The existence of a significant impact of market conditions on the spillovers between sentiment and ESG volatility. |

| Gong et al. (2024) | Quantile connectedness approach | China | The results indicate an asymmetric tail dependence and strong spillovers under extreme quantiles. |

| Kayani et al. (2024) | Quantile connectedness and TVP-VAR methodologies | Digital and traditional financial assets | Digital assets manifest heightened volatility in contrast to traditional and energy indices. The gaming industry, specifically focusing on Non-Fungible Tokens (NFT), presents itself as the most fitting asset for portfolio inclusion. This assertion gains credence from its comparatively lower degree of connectedness with other underlying assets. |

| Lo et al. (2024) | Quantile connectedness approach | Sub-Saharan Africa & MENA equity markets | Findings detect higher spillovers in extreme quantiles and heterogeneous network structure. |

| Ongo et al. (2024) | Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) System | 41 African countries | Stock market growth is positively and significantly affected by GDP, FDI, domestic credit to private sector, interest rate, natural resource rents, and information and communication technology. |

| Su and He (2024) | Quantile connectedness approach | Three markets: Fintech, carbon futures, and energy markets | COVID-19 and Russia–Ukraine conflict enhance the connectedness of markets. Portfolio analysis reveals major differences between normal and extreme markets. Minimum connectedness and correlation portfolios have a greater cumulative return. |

| Yaya et al. (2024) | Quantile connectedness approach | Egypt, Kenya, Morocco, Nigeria, South Africa, and Tunisia | (i) In the bearish market phase, South African stock dominated the entire network, transmitting shocks to the remaining stocks, while Moroccan and Kenyan stocks played similar role mildly. (ii) In the bullish market phase, Nigerian stock dominated the market as a major net transmitter of shock supported by South African and Kenyan stock markets. (iii) The Egyptian and Tunis stock markets are net shock receivers in both the bear and bull market phases. (iv) At the median quantile value, stocks become less riskier and the Kenyan stock market becomes the most vulnerable while Nigerian, Egyptian, and South African stock markets are influenced by other stock markets when markets are calm. (v) African stocks are underperforming, interested portfolio managers will learn from the trading strategies to be adopted to maximize their returns. |

| Akanbi (2025) | ARDL Cointegration approach | Nigeria | Stock market performance in Nigeria was influenced positively by GDP growth, while inflation and interest rate spread negatively. |

| Humpe et al. (2025) | ARDL cointegration approach | BRICS and Anglosphere countries | Economic growth enhances stock market performance, while inflation adversely affects it. |

| Jin et al. (2025) | Neural-network quantile regression connectedness approach | conventional, religious, and sustainable investments | The findings indicate that Tail connectivity varies significantly across investment types, and sustainable investments less vulnerable. |

| Shi et al. (2025) | Quantile VAR connectedness approach | China | New energy is considered as net transmitter, while extreme shocks increase connectedness. |

| Yusuf et al. (2025) | VAR model | Nigeria | Bidirectional causality is detected between GDP, money supply, interest rate, trade openness, inflation exchange rate and stock market development. |

| CPIMAR | M2MAR | GDPMAR | ITMAR | MAD.USD | UNEMPMAR | MASINDEX | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 0.005 *** (0.000) | 0.017 *** (0.000) | 0.008 ** (0.028) | −0.003 (0.765) | 0.004 (0.323) | 0.007 (0.551) | 0.006 (0.438) |

| Variance | 0.000 *** | 0.000 *** | 0.001 *** | 0.005 *** | 0.001 *** | 0.008 *** | 0.004 *** |

| Skewness | 1.167 *** (0.001) | 0.898 *** (0.005) | −1.734 *** (0.000) | 0.658 ** (0.032) | −0.050 (0.863) | −0.215 (0.458) | −0.838 *** (0.008) |

| Kurtosis | 2.861 *** (0.003) | 3.830 *** (0.001) | 9.997 *** (0.000) | 8.697 *** (0.000) | −0.147 (0.907) | −0.382 (0.687) | 2.645 *** (0.004) |

| JB | 34.088 *** (0.000) | 44.730 *** (0.000) | 279.930 *** (0.000) | 193.432 *** (0.000) | 0.079 (0.961) | 0.828 (0.661) | 24.509 *** (0.000) |

| ERS | −2.954 *** (0.005) | −1.843 * (0.071) | −2.708 *** (0.009) | −2.926 *** (0.005) | −1.852 * (0.070) | −1.623 * (0.111) | −2.181 ** (0.034) |

| Q(20) | 17.432 ** (0.049) | 89.229 *** (0.000) | 12.741 (0.251) | 27.335 *** (0.001) | 13.776 (0.182) | 99.476 *** (0.000) | 12.600 (0.261) |

| Q2(20) | 13.569 (0.195) | 12.415 (0.275) | 9.592 (0.550) | 19.682 ** (0.020) | 9.178 (0.596) | 16.649 * (0.067) | 6.329 (0.879) |

| Kendall | CPIMAR | M2MAR | GDPMAR | ITMAR | MAD.USD | UNEMPMAR | MASINDEX |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPIMAR | 1.000 *** | 0.214 ** | −0.046 | 0.153 | 0.179 ** | −0.052 | −0.104 |

| M2MAR | 0.214 ** | 1.000 *** | 0.006 | 0.059 | 0.002 | −0.198 ** | −0.049 |

| GDPMAR | −0.046 | 0.006 | 1.000 *** | −0.143 | −0.086 | −0.158 | 0.040 |

| ITMAR | 0.153 | 0.059 | −0.143 | 1.000 *** | −0.014 | 0.022 | −0.100 |

| MAD.USD | 0.179 ** | 0.002 | −0.086 | −0.014 | 1.000 *** | 0.058 | −0.086 |

| UNEMPMAR | −0.052 | −0.198 ** | −0.158 | 0.022 | 0.058 | 1.000 *** | −0.008 |

| MASINDEX | −0.104 | −0.049 | 0.040 | −0.100 | −0.086 | −0.008 | 1.000 *** |

| CPIMAR | M2MAR | GDPMAR | ITMAR | MAD.USD | UNEMPMAR | MASINDEX | FROM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPIMAR | 39.24 | 13.07 | 9.20 | 7.63 | 13.40 | 9.51 | 7.95 | 60.76 |

| M2MAR | 8.88 | 42.72 | 11.53 | 6.96 | 9.11 | 10.38 | 10.42 | 57.28 |

| GDPMAR | 5.40 | 14.11 | 38.41 | 9.20 | 3.98 | 9.32 | 19.58 | 61.59 |

| ITMAR | 10.57 | 8.79 | 19.99 | 33.67 | 8.92 | 7.51 | 10.56 | 66.33 |

| MAD.USD | 8.44 | 13.35 | 10.48 | 9.51 | 38.47 | 7.38 | 12.36 | 61.53 |

| UNEMPMAR | 9.96 | 21.63 | 14.54 | 6.71 | 8.42 | 29.24 | 9.50 | 70.76 |

| MASINDEX | 6.87 | 10.67 | 16.03 | 6.11 | 7.08 | 9.42 | 43.83 | 56.17 |

| TO | 50.12 | 81.62 | 81.76 | 46.12 | 50.92 | 53.52 | 70.38 | 434.43 |

| Inc.Own | 89.35 | 124.33 | 120.17 | 79.79 | 89.39 | 82.77 | 114.20 | cTCI/TCI |

| NET | −10.65 | 24.33 | 20.17 | −20.21 | −10.61 | −17.23 | 14.20 | 72.40/62.06 |

| NPT | 2.00 | 6.00 | 4.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| TND.USD | IRTU | UNEMPTU | CPITU | GDPTU | M2TU | TUNINDEX | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 0.032 *** (0.002) | 0.058 (0.112) | 15.927 *** (0.000) | 0.000 (0.802) | 0.003 (0.445) | 0.022 *** (0.000) | 0.013 * (0.086) |

| Variance | 0.006 *** | 0.079 *** | 1.452 *** | 0.000 *** | 0.001 *** | 0.000 *** | 0.003 *** |

| Skewness | 0.194 (0.503) | 0.454 (0.127) | 0.546 * (0.070) | 0.136 (0.638) | −1.756 *** (0.000) | −0.603 ** (0.048) | −0.186 (0.521) |

| Kurtosis | −0.578 (0.349) | 1.686 ** (0.023) | 0.564 (0.221) | −0.563 (0.372) | 22.281 *** | 0.735 (0.155) | 0.319 (0.368) |

| (0.000) | |||||||

| JB | 1.210 (0.546) | 9.170 *** (0.010) | 3.780 (0.151) | 0.978 (0.613) | 1271.954 *** (0.000) | 4.984 * (0.083) | 0.600 (0.741) |

| ERS | −1.786 * (0.080) | −2.882 *** (0.006) | −1.830 * (0.073) | −3.500 *** (0.001) | −4.093 *** (0.000) | −2.181 ** (0.034) | −3.183 *** (0.003) |

| Q(20) | 12.371 (0.279) | 52.484 *** (0.000) | 80.148 *** (0.000) | 84.028 *** (0.000) | 5.351 (0.940) | 19.144 ** (0.025) | 8.035 (0.721) |

| Q2(20) | 15.976 * (0.086) | 5.116 (0.951) | 81.192 *** (0.000) | 7.794 (0.747) | 16.338 * (0.075) | 39.294 *** (0.000) | 9.123 (0.602) |

| Kendall | TND.USD | IRTU | UNEMPTU | CPITU | GDPTU | M2TU | TUNINDEX |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TND.USD | 1.000 *** | 0.058 | −0.102 | 0.181 ** | 0.026 | 0.051 | 0.025 |

| IRTU | 0.058 | 1.000 *** | −0.241 ** | −0.055 | 0.019 | −0.120 | 0.069 |

| UNEMPTU | −0.102 | −0.241 ** | 1.000 *** | 0.021 | 0.136 | −0.137 | −0.096 |

| CPITU | 0.181 ** | −0.055 | 0.021 | 1.000 *** | 0.025 | 0.212 ** | 0.019 |

| GDPTU | 0.026 | 0.019 | 0.136 | 0.025 | 1.000 *** | −0.098 | −0.016 |

| M2TU | 0.051 | −0.120 | −0.137 | 0.212 ** | −0.098 | 1.000 *** | 0.147 |

| TUNINDEX | 0.025 | 0.069 | −0.096 | 0.019 | −0.016 | 0.147 | 1.000 *** |

| TND.USD | IRTU | UNEMPTU | CPITU | GDPTU | M2TU | TUNINDEX | FROM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TND.USD | 42.48 | 7.67 | 10.72 | 9.96 | 11.21 | 9.93 | 8.03 | 57.52 |

| IRTU | 7.58 | 48.69 | 11.20 | 4.16 | 11.05 | 7.43 | 9.88 | 51.31 |

| UNEMPTU | 8.13 | 15.29 | 45.70 | 5.20 | 13.68 | 7.52 | 4.48 | 54.30 |

| CPITU | 7.93 | 6.54 | 7.73 | 43.03 | 17.16 | 12.05 | 5.56 | 56.97 |

| GDPTU | 5.22 | 8.25 | 16.15 | 10.61 | 46.52 | 7.68 | 5.56 | 53.48 |

| M2TU | 9.55 | 9.21 | 7.27 | 8.18 | 9.55 | 49.77 | 6.48 | 50.23 |

| TUNINDEX | 9.06 | 9.20 | 9.59 | 7.55 | 11.99 | 12.40 | 40.21 | 59.79 |

| TO | 47.47 | 56.16 | 62.66 | 45.66 | 74.64 | 57.02 | 39.99 | 383.59 |

| Inc.Own | 89.95 | 104.85 | 108.36 | 88.70 | 121.16 | 106.78 | 80.20 | cTCI/TCI |

| NET | −10.05 | 4.85 | 8.36 | −11.30 | 21.16 | 6.78 | −19.80 | 63.93/54.80 |

| NPT | 1.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 2.00 | 5.00 | 4.00 | 1.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ben Salem, M.; Alsagr, N.; Belkhaoui, S.; Farhani, S. Quantile Connectedness Between Stock Market Development and Macroeconomic Factors for Emerging African Economies. Int. J. Financial Stud. 2025, 13, 224. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs13040224

Ben Salem M, Alsagr N, Belkhaoui S, Farhani S. Quantile Connectedness Between Stock Market Development and Macroeconomic Factors for Emerging African Economies. International Journal of Financial Studies. 2025; 13(4):224. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs13040224

Chicago/Turabian StyleBen Salem, Maroua, Naif Alsagr, Samir Belkhaoui, and Sahbi Farhani. 2025. "Quantile Connectedness Between Stock Market Development and Macroeconomic Factors for Emerging African Economies" International Journal of Financial Studies 13, no. 4: 224. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs13040224

APA StyleBen Salem, M., Alsagr, N., Belkhaoui, S., & Farhani, S. (2025). Quantile Connectedness Between Stock Market Development and Macroeconomic Factors for Emerging African Economies. International Journal of Financial Studies, 13(4), 224. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs13040224