1. Introduction

Understanding why individuals choose to participate—or abstain—from equity markets has remained a persistent concern in behavioral finance. The prevailing literature identifies several principal classes of determinants influencing household entry into the stock market. Early studies highlight economic and demographic factors—most notably net worth, disposable income, and chronological age—as statistically significant predictors, with higher wealth and advanced age positively associated with the probability of stock ownership (

Mankiw & Zeldes, 1991;

Haliassos & Bertaut, 1995). Complementary research emphasizes cognitive competencies such as financial literacy and intelligence as critical antecedents of investment participation.

Guiso and Jappelli (

2005) revealed that lack of financial knowledge depresses the likelihood of purchasing equities, while

van Rooij et al. (

2011) demonstrated that financial literacy retains predictive validity even after controlling for wealth and income. Similarly,

Grinblatt et al. (

2011) documented that higher IQ levels are significantly correlated with both stock market participation and superior investment performance.

Parallel to these economic and cognitive explanations, behavioral and sociological studies foreground the roles of attitudes and social context. Heightened risk aversion, ambiguity aversion, and loss aversion are each associated with reduced participation (

Cao et al., 2005;

Korniotis & Kumar, 2011;

Bonaparte et al., 2014). Sociological and institutional perspectives further reveal that trust in financial institutions, social network density, and peer behaviors shape investors’ willingness to enter markets (

Ng et al., 2004;

Guiso et al., 2008;

Balloch et al., 2015). Moreover, adverse episodic stimuli—such as corporate scandals—can erode investor confidence and suppress aggregate participation rates (

Giannetti & Wang, 2016).

Despite these advancements, significant conceptual and empirical gaps persist. The extant literature has thoroughly examined wealth, literacy, cognitive ability, and social capital but rarely explored the broader psychological orientations that underpin long-term financial behavior. Constructs such as future-time perspective, subjective life satisfaction, and perceived locus of control—collectively encapsulated in the notion of life attitude—remain underexplored within investment contexts. While such variables have been linked to retirement planning and saving behaviors (

Hershfield et al., 2011), their role in shaping equity market engagement has received little empirical attention. Furthermore, the interaction between these life orientations and cognitive ability remains insufficiently theorized. Individuals with high cognitive ability but weak future orientation, for example, may exhibit distinct market-entry patterns from those with lower cognitive abilities yet strong purpose orientation—suggesting potential mediation mechanism that warrant empirical testing.

Another notable gap concerns the relative neglect of young professionals as a distinct analytical cohort. This demographic—typically in the early stages of career advancement—features distinctive income trajectories, long investment horizons, and high receptivity to digital financial platforms. These features render early investment behavior especially consequential for lifetime wealth accumulation. Contemporary developments such as zero-commission trading, fractional-share ownership, and fintech-driven accessibility have significantly lowered participation barriers. Yet, these technological shifts may also alter the established relationships among cognition, attitudes, and participation. Hence, focusing on young professionals within emerging financial ecosystems like the Philippines offers both timeliness and theoretical value.

Young professionals now constitute a rapidly expanding segment of equity investors whose behaviors will define future market structures. Their initial investment decisions—whether prudent or speculative—carry substantial compounding effects over the life course. Understanding how cognitive ability and life attitude interact to influence stock market participation within this group holds practical importance for designing behavioral interventions, policy frameworks, and tailored financial education programs. In an era where market entry is frictionless, but decision complexity persists, disentangling the cognitive and psychosocial mechanisms of participation becomes a pressing scholarly and policy imperative.

This study, therefore, examines the joint influence of life attitude and cognitive ability on stock market participation among young professionals. The investigation extends the stock market participation puzzle (

Haliassos & Bertaut, 1995;

Guiso et al., 2008) by integrating constructs from existential psychology and behavioral finance. Life attitude—defined as one’s overarching sense of purpose, meaning, and orientation toward life (

Reker et al., 1987)—may affect financial decisions through pathways such as perceived risk, temporal focus, and goal prioritization. The Life Attitude Profile (LAP) provides a validated framework to capture these orientations (

Morgan & Farsides, 2009;

Kushlev et al., 2020), and recent studies confirm its predictive potential for purposeful and future-oriented behavior (

Jose et al., 2021;

Reker & Woo, 2011).

Cognitive ability, operationally defined as financial literacy, complements this orientation by enabling effective information acquisition, processing, and utilization (

van Rooij et al., 2011). Individuals with higher cognitive proficiency tend to engage in stock markets more frequently due to enhanced risk assessment and decision accuracy (

Banks & Oldfield, 2007;

Skagerlund et al., 2023). Empirical evidence also supports a mediating role for cognition—reducing information costs, refining risk preferences, and amplifying the behavioral impact of life orientations (

Cole et al., 2023;

Bruine de Bruin & Parker, 2021). Thus, cognitive ability may operate as a channel through which broader life attitudes exert influence on financial engagement.

Behavioral finance further posits that financial behavior emerges from the integration of cognitive and subjective factors. Cognitive psychology and decision theory emphasize that while information is processed systematically, decisions are ultimately guided by affective judgments, perceived control, and self-efficacy. Empirical studies confirm these interaction effects:

Waggle et al. (

2001) demonstrated that the interplay between objective and subjective assessments of safety significantly affects investment outcomes. Likewise,

Christelis et al. (

2010) and

Lusardi and Mitchell (

2014) observed that cognitive ability and financial literacy influence participation most strongly when coupled with positive attitudes and confidence. More recent evidence corroborates the cognitive–subjective nexus across contexts, including studies by

Akhter and Hoque (

2022),

Callis et al. (

2023), and

Bai (

2023).

In emerging economies such as the Philippines, this nexus is particularly relevant. The nation’s rapidly growing economy, expanding digital finance infrastructure, and unique cultural–economic dynamics—such as family obligations and aspirational consumption—create a context where traditional Western predictors may not fully explain financial behavior. Yet, empirical work on Filipino young professionals remains limited, despite their increasing exposure to financial technology and evolving investment mindsets. Addressing this gap provides theoretical advancement and policy relevance in behavioral finance research for developing markets.

The central research question guiding this study is: How do life attitude and cognitive ability jointly influence the likelihood of stock market participation among young professionals, and to what extent does cognitive ability mediate this association? To address the central research question, the study aims to achieve several interrelated objectives. It first seeks to assess the life attitude profile of young professionals, capturing their sense of purpose, meaning, and future orientation as psychological determinants of financial behavior. Second, it aims to quantify their cognitive ability, focusing on financial literacy and related competencies that influence information processing and investment decision-making. Third, the study intends to determine the level of equity market participation among this cohort, providing empirical insights into their engagement with stock investments. Building on these foundations, the study further seeks to examine the effect of life attitude on stock market participation, evaluating how broader life orientations shape financial engagement. It also aims to assess the impact of cognitive ability on participation, identifying the extent to which cognitive proficiency facilitates market entry. Finally, the study endeavors to test whether cognitive ability mediates the relationship between life attitude and stock market participation, thereby elucidating the cognitive pathways through which psychological dispositions translate into financial behavior.

1.1. Conceptual Framework

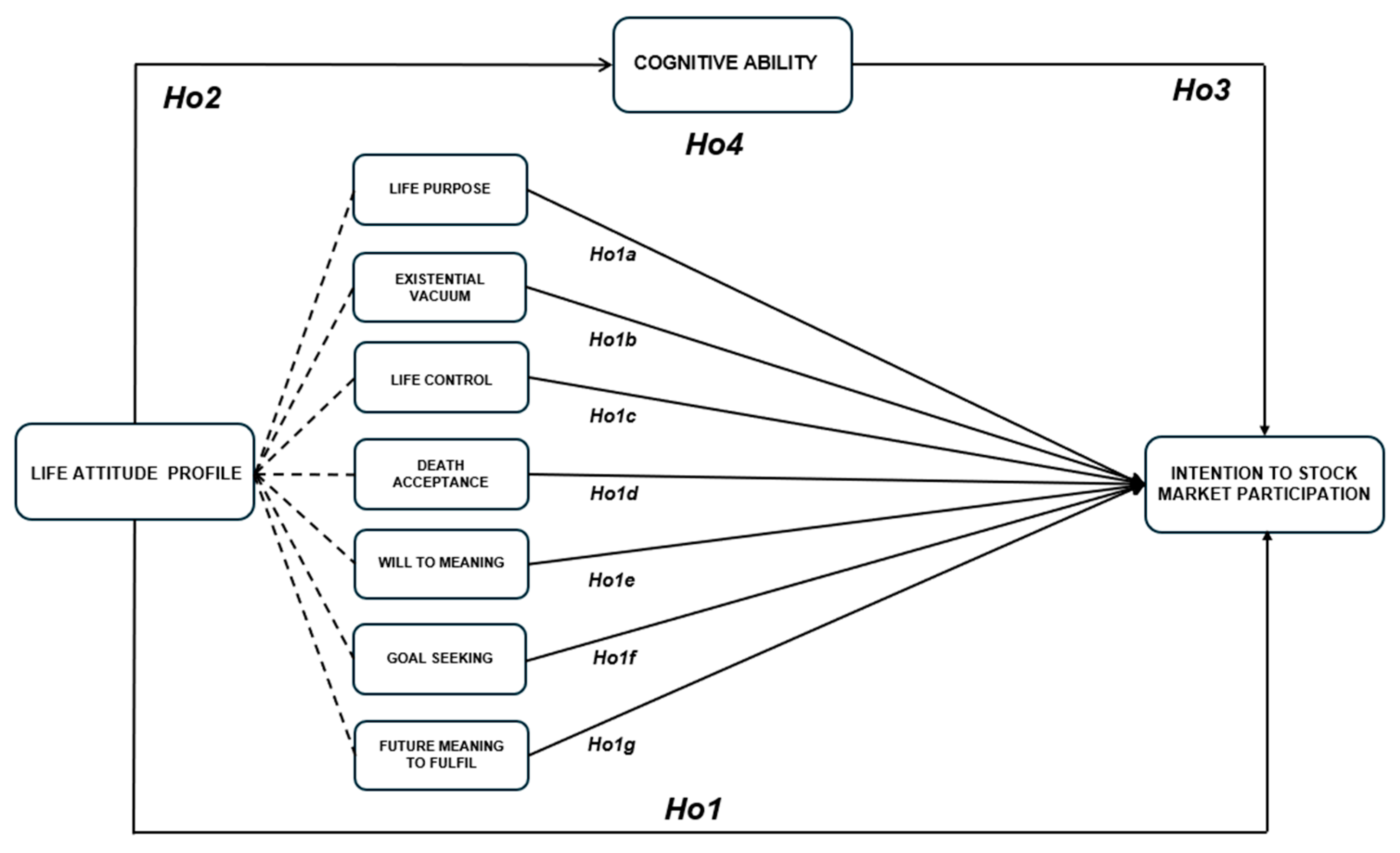

Figure 1 depicts a theoretical model articulating the interplay between life orientations, cognitive aptitude, and the intention to engage in stock-market activity. The central construct is the Life Attitude Profile (LAP), comprising seven interdependent dimensions: life purpose, existential vacuum, life control, acceptance of mortality, will to meaning, goal orientation, and future-orienting meaning. The model postulates that the LAP exerts a direct, unmediated effect on the intention to invest in equity markets. In parallel, cognitive ability is specified as a mediating construct, positing that individuals equipped with elevated cognitive faculties are more proficient in processing financial information, thereby harmonizing personal life orientation with forthcoming investment decisions. The model thus encapsulates the mutual modulation of affectivity and cognitive processing in the shaping of financial comportment.

1.2. Hypotheses Development

The behavioral finance literature has devoted sustained attention to the psychological and cognitive determinants of capital-market participation. Traditional neoclassical models presume that agents act on fully rational valuations; mounting evidence, however, indicates that long-standing dispositions, normative orientations, and cognitive faculties profoundly condition intentions to invest. Taking collectively, these variables suggest a conception of agency that integrates cognitive dispositions and perceived socio-normative frameworks. The Life Attitude Profile (LAP)—an instrument that assesses dimensions including life purpose, sense of existential void, perceived control, acceptance of mortality, volitional tendencies toward significance, goal directedness, and projected future significance—represents an operationalized distillation of agents’ horizons of existential meaning. Empirical analysis indicates that these orientations condition risk perception, alter motivational values toward investment, and thereby influence the volitional intention to interact with equity markets. Beyond purely existential orientations, cognitive ability—conceptualized as efficiency in processing and integrating financial information—has been empirically positioned as a mediating factor that shapes how normative and motivational dispositions translate into observable financial behavior. Individuals with higher cognitive ability tend to evaluate opportunities and risks more effectively, thereby enhancing the alignment between underlying dispositions and actual financial decision-making. Mapping the interrelations among life meaning, cognitive processing, and investment intention renders an integrative model of investor psychology, one that has practical implications for the design and calibration of financial–educational interventions across diverse populations.

Hence, the following hypotheses were developed:

Ho1: There is no significant relationship between Life Attitude Profile (LAP) dimensions and Intention to Stock Market Participation.

Ho1a: There is no significant relationship between Life Purpose and Intention to Stock Market Participation.

Ho1b: There is no significant relationship between Existential Vacuum and Intention to Stock Market Participation.

Ho1c: There is no significant relationship between Life Control and Intention to Stock Market Participation.

Ho1d: There is no significant relationship between Death Acceptance and Intention to Stock Market Participation.

Ho1e: There is no significant relationship between Will to Meaning and Intention to Stock Market Participation.

Ho1f: There is no significant relationship between Goal Seeking and Intention to Stock Market Participation.

Ho1g: There is no significant relationship between Future Meaning to Fulfil and Intention to Stock Market Participation.

Ho2: There is no significant relationship between Life Attitude Profile (overall) and Cognitive Ability.

Ho3: There is no significant relationship between Cognitive Ability and Intention to Stock Market Participation.

Ho4: Cognitive Ability does not significantly mediate the relationship between Life Attitude Profile and Intention to Stock Market Participation.

Theoretically, the study enriches the behavioral finance literature by bridging existential psychology and economic decision-making—an intersection rarely explored. By integrating life attitude and cognition, it offers a more holistic understanding of the psychological architecture underlying financial participation, thereby extending explanations of the stock market participation puzzle. Methodologically, it employs mediation and moderated mediation models using robust PLS-SEM techniques, allowing rigorous estimation of latent constructs and indirect effects. Practically, the study provides insights for financial education, policy design, and behavioral interventions tailored to the young-professional cohort. It underscores the need to couple financial literacy initiatives with psychosocial skill development—cultivating not only numeracy and analytical competence but also purpose-driven and future-oriented mindsets. Such interventions can narrow the persistent knowledge–action gap and promote sustained market participation across the investment lifecycle.

Following this introduction,

Section 2 presents the materials and methods of the study, encompassing the research design, sampling procedure, measurement instruments, and analytical framework employed to examine the proposed relationships.

Section 3 reports the empirical results derived from the PLS-SEM analysis, including estimates of direct and mediating effects.

Section 4 offers an integrated discussion of the findings in light of the existing literature, incorporating robustness and sensitivity analyses to validate the model’s stability. This section also outlines the study’s limitations, practical implications, and recommendations for future inquiry.

2. Materials and Methods

The investigation adopted a quantitative design to assess how life perspective, intellectual capacity, and equity-market engagement interact in a sample of young professionals. Researchers executed both descriptive and inferential statistical analyses. The descriptive step generated comprehensive summaries of participants’ demographic features, prevailing life outlooks, cognitive skill levels, and their varying degrees of involvement in stock trading. The inferential stage, in contrast, estimated correlation coefficients and tested hypothesized directional influences from the independent factors (life perspective and cognitive ability) to the dependent factor (participation in the stock exchange). A pre-developed, closed-form questionnaire, which incorporated psychometrically validated scales, served as the primary data collection tool, thereby safeguarding both construct and measurement reliability.

The investigation targeted professionals living in the province of Bulacan and commuting daily to jobs in Metro Manila. For this research, we described “young professionals” as white-collar employees aged 20 to 39, holding at minimum either an associate degree, bachelor degree, master degree, or recognized professional credential. Participants engaged in standard office roles, received a fixed monthly salary, and had ongoing employment. Based on 2020 Census data, there were 105,626 residents aged 20 to 39 in the City of Malolos, Bulacan, accounting for roughly 41.5 percent of the city’s total headcount. Applying the Raosoft sample size calculator at a 95 percent confidence level and a 5% margin of error, the targeted sample was established at 384 individuals. Out of these targeted sample individuals, a total of 195 young professionals responded to the survey, yielding a response rate of approximately 50.8%. To achieve broad and unbiased coverage of the demographic, a procedure of simple random sampling was adopted.

The questionnaire designed for this study comprised four core sections. In the opening part, participants provided demographic data, specifically age, sex, educational attainment, and employment status. The subsequent section evaluated the intention to engage in the stock market. A five-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 5 = Strongly Agree) scored three adapted statements from previous works (

Ajzen, 1991): “I plan to educate myself on stock market investing,” “I will motivate family and/or friends to invest in the stock market,” and “I aim to invest in the stock market in the near future.” The third block surveyed participants’ general attitude toward life by deploying the Life Attitude Profile–Revised (LAP-R) created by Lary T. Reker, which captures dimensions including life-purpose, existential vacuum, personal control, acceptance of mortality, will to meaning, goal attraction, and future purpose. The profile elucidated the broader perspective on existence that may shape subsequent financial choices.

The final section examined cognitive competence through the Financial Literacy Inventory developed by

van Rooij et al. (

2011). This scale encompassed both fundamental and advanced financial concepts, assessing abilities in basic numeracy, inflation comprehension, risk diversification, and other principles of personal investing. Respondents’ cognitive ability was measured using 16 items, each coded as “1” for a correct response and “0” for an incorrect one. The total raw scores (ranging from 0 to 16) were subsequently converted into percentage equivalents to enhance interpretability and comparability across participants—for instance, a score of 16 corresponded to 100%, 12 to 75%, and 8 to 50%. This linear transformation (Percentage = Raw Score ÷ 16 × 100) aligns with the standardized scoring approach employed in prior financial literacy studies (

Lusardi & Mitchell, 2014;

OECD, 2018;

Potrich et al., 2018). Such normalization enables classification of literacy levels as high, moderate, or low, consistent with international benchmarks for cognitive financial competence. All instruments utilized in the study were drawn from previously validated scales, ensuring that the measures were both reliable and comparable with extant empirical research in the field.

The adapted and self-developed scales employed in this study demonstrated acceptable levels of internal consistency through reported reliability coefficients; however, external validation of these instruments within the local population remains limited. This reliance represents a methodological limitation, as cultural and demographic factors may influence the constructs measured. Emphasizing this caveat, future research should focus on conducting rigorous psychometric validation of these tools across similar contexts to enhance robustness, comparability, and generalizability of findings in studies examining financial literacy, cognition, and related behavioral outcomes. Moreover, while financial literacy effectively captures domain-specific knowledge and decision-making skills in financial contexts, it may not fully reflect the broader dimensions of cognitive ability, such as abstract reasoning or general information-processing efficiency. This conceptual overlap introduces the risk of conflating financial knowledge with cognitive capacity, and future research should consider employing complementary measures of cognition to provide a more comprehensive assessment.

Before data collection, a briefing session was held with prospective respondents, clarifying the research goals, the stringent confidentiality protocols in place, and the entirely voluntary character of their involvement. Questionnaires were then made available in both printed and digital formats to maximize accessibility. For the online version, a secure hyperlink was distributed to subjects via either email attachments or messaging app texts. Participants were allotted a seven-day period to submit their responses, at the conclusion of which gentle reminders were dispatched. Submitted questionnaires were retrieved, checked for completeness, and subsequently encoded into a dedicated statistical software package for the forthcoming analyses.

To empirically assess the proposed relationships, Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) was employed using SmartPLS 4.0, consistent with best practices outlined by

Hair et al. (

2021). PLS-SEM, a variance-based structural modeling technique, was deemed appropriate due to the study’s emphasis on prediction, mediation testing, and theory development rather than strict theory confirmation. This analytical approach allows for the simultaneous estimation of multiple latent constructs and mediating pathways, accommodating non-normal data distributions and moderate sample sizes typical of behavioral research (

Hair et al., 2019a).

The choice of PLS-SEM over covariance-based SEM (CB-SEM) was methodologically justified. While CB-SEM is generally applied for confirmatory analyses that require global model fit indices and assume multivariate normality (

Kline, 2016;

Byrne, 2016), PLS-SEM offers greater flexibility for exploratory and predictive modeling where constructs originate from multiple theoretical perspectives (

Sarstedt et al., 2017). Given the study’s objective to predict behavioral intentions and examine the mediating influence of cognitive ability within a multidimensional psychological framework, PLS-SEM was the most suitable analytical approach.

To enhance methodological rigor, bootstrapping procedures with 5000 resamples were conducted to evaluate the significance of direct, indirect, and total effects. The two-tailed significance criterion (

p < 0.05) was adopted to assess the robustness of path coefficients, consistent with recommendations by

Hair et al. (

2021). Furthermore, control variables—namely sex, age, educational attainment, and employment status—were included to account for potential confounding influences on behavioral intentions and cognitive mediation pathways.

To further assess model consistency and potential heterogeneity, multi-group analyses (MGAs) were performed across sex [male (n = 70), female (n = 125)] and educational attainment [bachelor’s degree (n = 153), postgraduate degree (n = 42)]. These subgroup analyses enabled a more nuanced understanding of structural path invariance and whether the strength of relationships differed significantly across demographic categories. Together, these procedures ensure the robustness, generalizability, and interpretive validity of the estimated model within the study’s behavioral-finance context.

Investor choice-making transcends pure economic calculation; it intertwines psychological and cognitive layers that shape financial actions. The Life Attitude Profile (LAP)—which gauges how individuals derive meaning and purpose in daily life—may influence equity market participation through mechanisms such as existential beliefs, perceived purpose, and goal coherence. Similarly, cognitive capacity governs how efficiently individuals process financial information, potentially acting as a mediating conduit through which life attitudes translate into investment intentions. Examining these interrelations not only elucidates the human dimension of financial decision-making but also contributes to advancing the behavioral finance literature and informing financial education policy and program design.

2.1. Regression Models

The first regression model examines the influence of Life Attitude Profile on the Intention to Stock Market Participation. It is expressed as:

where:

The second regression model examines the influence of the seven dimensions of the Life Attitude Profile on the Intention to Stock Market Participation. It is expressed as:

where:

The third model investigates the relationship between the overall Life Attitude Profile score and Cognitive Ability:

where:

The fourth model tests whether Cognitive Ability significantly predicts Intention to Stock Market Participation:

where:

The mediation model is evaluated within a PLS-SEM framework, emphasizing the estimation of bootstrapped indirect effects with confidence intervals to ensure methodological rigor and alignment with current analytical standards. It consists of two equations:

where:

2.2. Ethical Considerations

Given that this research involved the collection of primary data from human participants through a self-administered questionnaire, ethical integrity was a central consideration throughout the study’s design and implementation. Prior to data collection, the research protocol underwent formal review and approval by the Institutional Ethics Review Committee of Bulacan State University, ensuring that all procedures adhered to established ethical standards for studies involving human subjects.

All respondents were provided with a detailed informed consent form outlining the study’s objectives, the voluntary nature of participation, potential risks and benefits, and the assurance of anonymity and confidentiality. Participants were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any point without penalty. Consent was obtained prior to the administration of the questionnaire, and no personal identifiers—such as names, contact details, or institutional affiliations—were collected to preserve participant anonymity.

To safeguard data privacy, all collected information was stored in encrypted digital files accessible only to the research team. The handling of data complied with the ethical principles set forth in institutional guidelines and the Data Privacy Act of 2012 (Republic Act No. 10173). The analysis and reporting of data were conducted in aggregate form to eliminate the possibility of identifying individual participants or organizations. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of respect for persons, beneficence, and justice, thereby ensuring that participants’ rights, dignity, and confidentiality were fully protected throughout the research process. Furthermore, the anonymized raw data supporting the findings of this study, survey questionnaire and measurement scales are available in the

Supplementary Materials.

3. Results

This section summarizes the evidence produced from the examination of data assembled to meet the study’s overarching research objectives and precise questions.

Table 1 summarizes the core participant profiles with respect to their general life perspective, cognitive capabilities, and stock market engagement disposition. Across the sample, the Life Attitude Profile yielded an average of 5.59 and an SD of 0.80, denoting an overall constructive stance toward life’s significance and objectives. When examined at the subscale level, the Goal-Seeking component displayed an elevated average of 6.11 (SD = 0.73), underscoring the relative prominence of future-oriented motive to track clearly defined, enduring personal ambitions. This elevated achievement suggests that the sample may possess an advanced propensity toward intentional life design, a trait that is often linked with prudent future-oriented financial maneuvers. Sequentially, measures of Will to Meaning yielded a mean of 5.87 and an SD of 0.66, while Life Control averaged 5.82 with an SD of 0.70, both reflecting a conscious and constructive belief in individual capacity to influence outcomes and nurture value-laden life events. Collectively, these trends suggest an inclination not only to acknowledge determinants within life’s trajectory but also to use that awareness in planning future-oriented activities, including financial commitments, particularly within investment arenas.

Death Acceptance received the lowest average score among the measures (M = 5.07, SD = 0.94), suggesting that respondents limit their engagement with death-related themes. The Existential Vacuum score (M = 5.22, SD = 1.00), although marginally higher, remains moderate. It hints that a segment of the sample perceives emptiness, a sentiment that could color long-term fiscal strategies and the subjective weighing of risks. The result is consistent with the existential psychology literature, which asserts that diminished meaning can predispose individuals toward particular investment tendencies that differ from those guided by a stable sense of purpose.

Cognitive Ability scored a mean of 67.83 (SD = 16.53). The prominent standard deviation signals notable heterogeneity and implies that not all investors or potential investors share the same evaluative capacity. Existing scholarship identifies a nexus between cognitive acuity and key decision competencies, namely, the appraisal of risks, the assimilation and application of monetary knowledge, and, by extension, the likelihood of engaging with equity markets (

Lusardi & Mitchell, 2014).

Consequently, those registering higher cognitive performances may exhibit enhanced self-assurance and a firmer resolve to become active participants in investment settings.

The Intention to Stock Market Participation scale revealed a moderate mean (M = 4.28, SD = 0.53), reflecting a moderate leaning toward prospective equity investing across the sample. Coupled with parallel life attitude and cognitive ability indices, the finding lends initial support to the hypothesis that intrinsic motives—such as goal orientation and the pursuit of meaning—interact with cognitive capacity to steer investment inclinations. The convergence of these psychological and cognitive domains corroborates the broader theoretical view that mental framing and reasoning acumen are vital to the architecture of capital-market decision strategies.

Table 2 presents the assessment results for internal consistency and convergent validity of the reflective constructs. All indicator loadings exceed the recommended threshold of 0.708, confirming adequate indicator reliability, while the corresponding VIF values remain below 3.0, indicating the absence of multicollinearity among indicators. The Cronbach’s α values range from 0.720 (Future Meaning to Fulfil) to 0.924 (Life Purpose), and composite reliability (CR) values span from 0.839 to 0.938—both surpassing the acceptable benchmark of 0.70, signifying strong internal consistency across constructs. Furthermore, the average variance extracted (AVE) values, which range from 0.636 to 0.817, all exceed the 0.50 cutoff, demonstrating that more than half of the variance in the indicators is explained by their respective latent constructs. These results collectively affirm that the measurement model achieves satisfactory levels of reliability, internal consistency, and convergent validity, providing a solid foundation for subsequent structural analysis (

Hair et al., 2019b;

Fornell & Larcker, 1981;

Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994).

As all data were collected from a single source using self-report measures, common method variance (CMV) was assessed following multiple procedures. A principal component factor analysis with unrotated extraction in SPSS 22 was performed, loading all measurement items from the constructs listed in

Table 2 onto a single factor.

Table 3 shows the unrotated factor solution revealed eight distinct factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, explaining a cumulative variance of 67.48%. The first factor accounted for only 29.32% of the total variance, which is below the 50% threshold (

Podsakoff et al., 2003). Thus, no single factor accounted for most of the covariance, indicating that CMV is not a major issue in the dataset.

To further assess CMV, a full collinearity test was conducted by examining Variance Inflation Factors (VIFs) for all latent constructs (

Kock, 2015). All VIF values ranged from 1.137 to 3.950, which are well below the upper threshold of 5.0, and within the conservative limit of 3.3 for detecting common-method bias. This confirms that no multicollinearity or CMV problem exists among the constructs (

Hair et al., 2021). Although no marker variable was included due to the finalized nature of the instrument, the convergence of these tests provides sufficient evidence that common method bias is unlikely to distort the relationships observed in the structural model.

The discriminant validity of the reflective measurement model was examined using the Fornell–Larcker criterion, which stipulates that each construct’s square root of the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) should exceed its highest correlation with any other construct (

Fornell & Larcker, 1981). As shown in

Table 4, all diagonal entries (square roots of AVEs) are greater than the corresponding off-diagonal correlations, confirming satisfactory discriminant validity among the latent constructs. Specifically, the square roots of the AVE values for all constructs—Life Purpose (LP = 0.826), Future Meaning to Fulfill (FMF = 0.854), Life Control (LC = 0.809), Existential Vacuum (EV = 0.841), Death Acceptance (DC = 0.798), Goal Seeking (GS = 0.833), Will to Meaning (WTM = 0.864), and Intention to Stock Market Participation (SMP = 0.904)—are substantially higher than their inter-construct correlations. This finding indicates that each construct shares more variance with its respective indicators than with other constructs in the model.

Among the latent variables, moderate to strong correlations were observed between LP and FMF (r = 0.749), LP and WTM (r = 0.742), and FMF and WTM (r = 0.758), suggesting theoretical interdependence in how individuals’ life purpose and financial management fundamentals relate to their willingness to manage investments. Similarly, LC showed substantial correlation with GS (r = 0.715), aligning with prior findings that individuals with stronger life control are more likely to engage in structured goal setting.

On the other hand, EV displayed relatively low correlations with the other constructs (ranging from –0.036 to 0.405), implying its conceptual distinctiveness and minimal overlap with financial and psychological dimensions of stock market participation behavior. The discriminant validity results therefore confirm that all constructs are empirically distinct and contribute uniquely to the measurement of the higher-order construct, Stock Market Participation (SMP). Overall, the Fornell–Larcker results, together with the earlier evidence of internal consistency and convergent validity, indicate that the measurement model demonstrates sound psychometric properties, justifying its use in the subsequent structural model analysis.

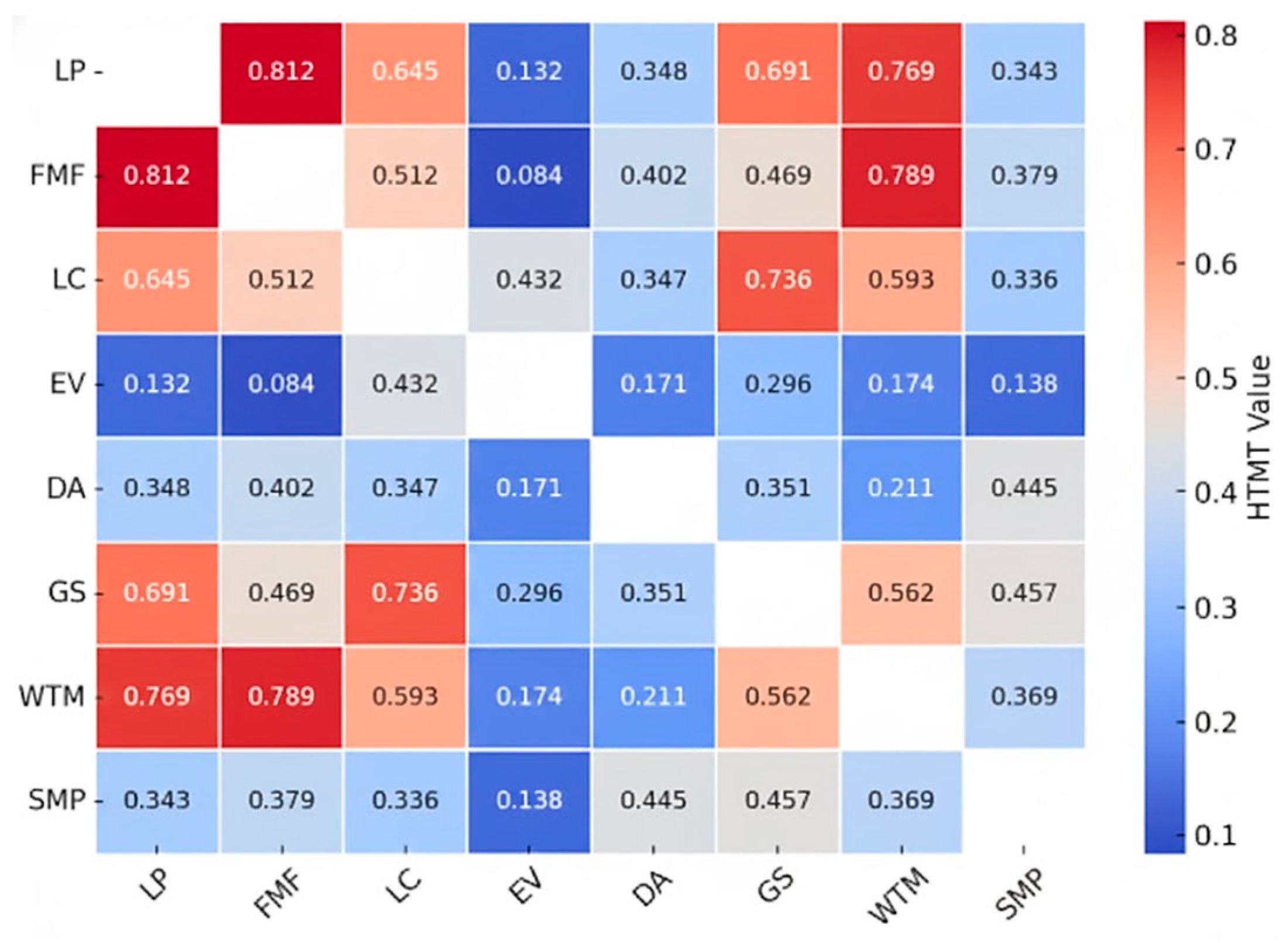

Figure 2 shows the Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) results which demonstrates satisfactory discriminant validity among the constructs included in the structural model. All inter-construct HTMT values ranged between 0.08 and 0.81, which are well below the conservative threshold of 0.85 (

Henseler et al., 2015), confirming that each latent construct is empirically distinct from the others.

Notably, the strongest association was observed between Life Purpose (LP) and Will to Meaning (WTM) (HTMT = 0.769), followed closely by Life Purpose (LP) and Future Meaning to Fulfil (FMF) (HTMT = 0.812), both of which conceptually align with the broader life attitude framework. Conversely, Existential Vacuum (EV) recorded consistently low HTMT values with all other constructs (ranging from 0.08 to 0.43), further affirming its conceptual distinctiveness as a negative life orientation factor.

The structural model reveals the intricate psychological and cognitive underpinnings of individuals’ intention toward stock market participation (SMP).

Table 5 demonstrates that the combined explanatory power of the latent constructs—Life Attitude Profile (LAP) and Cognitive Ability (C)—ranges between 47.1% and 58.2% (R

2 = 0.471–0.582), signifying that nearly half of the variance in SMP can be attributed to existential and cognitive factors. These findings extend the behavioral-finance perspective by emphasizing that financial intentions are not solely grounded in economic rationality but are also shaped by how individuals construe meaning, purpose, and control in life.

The overall positive effect of LAP on SMP (β = 0.154,

p = 0.025) indicates that individuals who possess a more integrated and adaptive life attitude are more inclined to engage in investment behavior. This corroborates prior research linking psychological resources—such as sense of purpose and perceived control—to proactive financial decisions (

Stolper & Walter, 2017;

Xiao & O’Neill, 2018). People who perceive their lives as coherent and goal-directed tend to plan for the future and demonstrate a stronger propensity to invest, consistent with evidence that future orientation predicts financial engagement (

Lusardi & Mitchell, 2014). The finding advances knowledge by suggesting that existential coherence operates as a motivational driver of financial participation, independent of material resources or risk-return calculus.

Interestingly, Life Purpose (LP) shows a negative relationship with SMP (β = −0.243,

p = 0.036). While life purpose is often associated with adaptive planning, the result suggests that individuals with clearly defined purposes may adopt a more deliberate or conservative financial stance. This aligns with research showing that purpose-driven individuals frequently prioritize security and long-term stability over short-term speculative gain (

Burrow & Hill, 2011;

Duckworth & Gross, 2014). Such individuals may channel resources toward goals congruent with their overarching life mission—such as education or philanthropy—rather than toward higher-volatility investments. Hence, a strong sense of purpose may reduce immediate investment intention when the content of that purpose values certainty and control.

By contrast, Death Acceptance (DA) exhibits a strong positive effect on SMP (β = 0.312,

p < 0.001). This supports psychological evidence that individuals who have reconciled with mortality tend to demonstrate greater openness to risk and novel experiences (

Wang et al., 2024). Acceptance of life’s finitude may diminish loss aversion and foster a desire to pursue meaningful opportunities, including investment, as a means of legacy building. Thus, existential acceptance appears to act as a catalyst for calculated financial risk-taking, highlighting an underexplored psychological determinant of investment behavior.

Similarly, Goal Seeking (GS) positively predicts SMP (β = 0.396,

p = 0.009), reinforcing findings that goal-oriented individuals are more likely to pursue investments to achieve future aspirations (

Darvishan, 2024;

Tang & Baker, 2016). Goal seekers tend to view the stock market as an instrumental pathway to fulfil their objectives, showing higher engagement and self-efficacy in financial planning. These results highlight the motivational mechanism through which goal-driven orientations translate into economic intention.

Other LAP subdimensions—Existential Vacuum (EV), Life Control (LC), Will to Meaning (WTM), and Future Meaning to Fulfil (FMF)—display nonsignificant relationships with SMP. This pattern suggests that although these existential traits contribute to one’s sense of meaning, they do not directly influence investment intention without cognitive or instrumental reinforcement. Consistent with meaning-in-life research, certain facets of existential orientation exert their effects only when aligned with domain-specific knowledge or confidence (

Steger et al., 2006). This nuance refines theoretical understanding by identifying which dimensions of life attitude are motivationally active in economic contexts.

Cognitive Ability, proxied by financial literacy, exhibits a robust direct effect on SMP (β = 0.329,

p < 0.001), supporting extensive evidence that financial literacy enhances participation in capital markets (

van Rooij et al., 2011;

Del Prete et al., 2024). Financially knowledgeable individuals possess both the confidence and competence to navigate complex investment decisions, underscoring cognition as an enabling condition for behavioral execution. Furthermore, LAP significantly predicts C (β = 0.158,

p = 0.023), suggesting that adaptive life attitudes foster higher levels of financial understanding. This aligns with studies showing that goal-oriented individuals are more likely to engage in learning and self-development activities that enhance domain competence (

Seligman, 2011). The finding introduces a novel antecedent of financial literacy, linking existential meaning with cognitive skill development.

The mediation analysis reveals that Cognitive Ability mediates the relationship between LAP and SMP (β = 0.051,

p = 0.032). This demonstrates that life attitudes influence financial intentions both directly—by shaping motivation—and indirectly—by enhancing cognitive readiness. Similar dual-path mechanisms have been observed in studies where psychosocial traits improve financial outcomes through increased learning and confidence (

Tang & Baker, 2016). The present model therefore offers an integrative framework: existential attitudes shape investment intention through both motivational (e.g., goal seeking, death acceptance) and cognitive (financial literacy) pathways. In advancing the behavioral-finance literature, this synthesis highlights that fostering financial participation requires attention not only to informational interventions but also to individuals’ broader sense of life meaning and purpose.

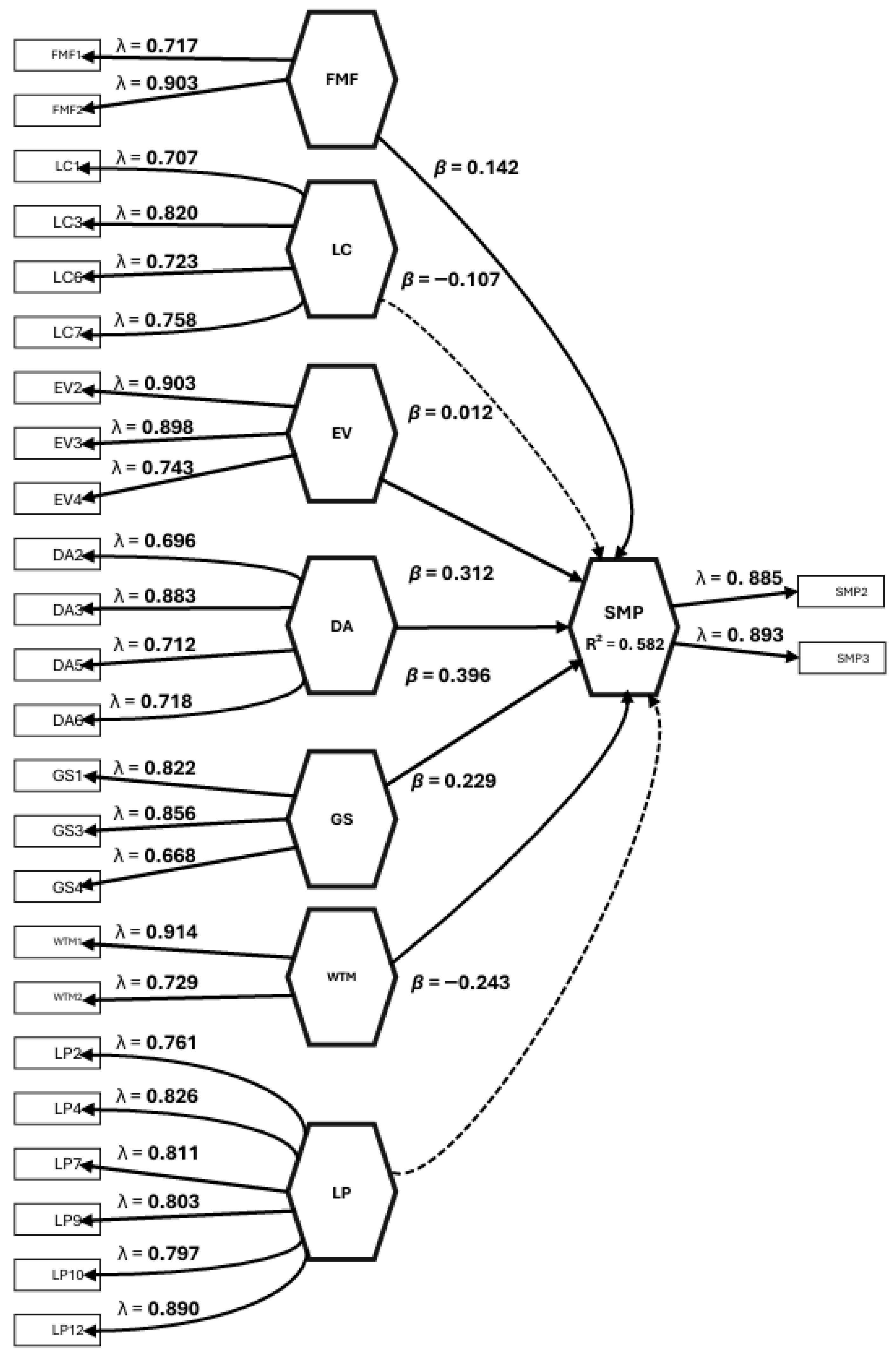

Figure 3 illustrates the lower-order constructs that underpin the structural model explaining individuals’ intention toward stock market participation (SMP). Grounded in the Life Attitude Profile (LAP), the model integrates existential and attitudinal dimensions to capture how people’s perceptions of meaning, purpose, and control over life shape their financial engagement. Collectively, these constructs depict stock market participation not as a purely economic or rational behavior, but as an extension of one’s psychological orientation toward life goals and fulfillment.

Most of the constructs demonstrate positive relationships with SMP, suggesting that individuals who embrace a forward-looking mindset—marked by the pursuit of meaning, acceptance of life’s realities, and motivation to achieve personal goals—tend to exhibit stronger intentions to invest. This aligns with perspectives from behavioral finance and existential psychology, where purposeful and self-determined individuals are more likely to take proactive steps toward financial independence and security. Engagement in the stock market may thus serve as a means of realizing broader life aspirations and constructing a sense of future meaning.

Life Control (LC) and Life Purpose (LP) show negative associations with SMP. This pattern implies that individuals who already perceive a strong sense of control or who possess a well-established life purpose may feel less driven to participate in the stock market as a means of achieving meaning or agency. Their stability and self-assuredness in life could reduce the motivational pull toward external expressions of control, such as financial risk-taking or investment participation. In contrast, those who are still seeking direction or striving to assert greater control over their lives may be more inclined to view financial engagement as an avenue for empowerment or self-actualization.

The other lower-order constructs—Future Meaning to Fulfill (FMF), Existential Vacuum (EV), Death Acceptance (DA), Goal Seeking (GS), and Will to Meaning (WTM)—demonstrate positive directional relationships with SMP. These results highlight that individuals who actively seek meaning, acknowledge life’s impermanence, and set meaningful personal goals are more likely to invest. Investment behavior, in this sense, becomes a psychological expression of agency and future orientation, reflecting a desire to build a meaningful and secure life trajectory.

Figure 3 presents a complex view of how existential factors influence financial behavior. The negative paths from LC and LP underscore the complexity of human motivation, revealing that a strong internal sense of purpose and control may reduce the need for external avenues of fulfillment. Meanwhile, the positive associations from other constructs reinforce the idea that seeking meaning, embracing personal growth, and setting future-oriented goals are powerful motivators of stock market participation. This interpretation advances the understanding of financial behavior by situating it within a broader existential framework—where investing is not merely about wealth accumulation, but also about purpose, meaning, and life direction.

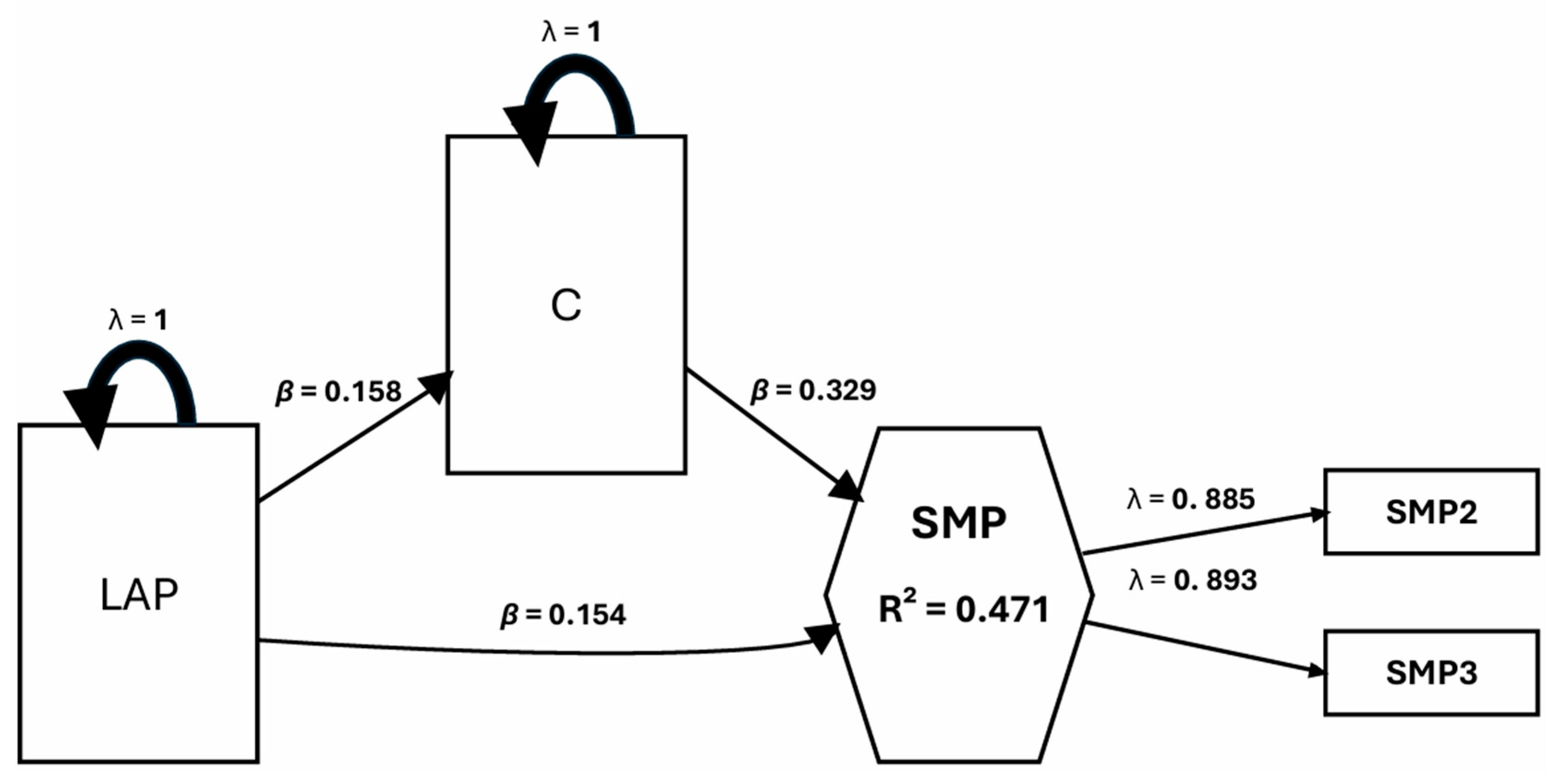

Figure 4 illustrates the higher-order structural model that integrates the Life Attitude Profile (LAP), Cognitive Ability (C), and Intention to Stock Market Participation (SMP). The model captures how individuals’ life attitudes and cognitive capacities collectively shape their behavioral inclination toward engaging in the stock market. The coefficient of determination (R

2 = 0.471) reveals that nearly 47% of the variance in SMP is accounted for by LAP and C, suggesting a moderate yet meaningful explanatory power of the model.

The results show that LAP exerts a direct positive influence on SMP (β = 0.154), implying that individuals with a more optimistic and adaptive outlook on life tend to express stronger intentions to participate in stock market activities. Beyond this direct association, LAP also demonstrates a positive relationship with Cognitive Ability (β = 0.158), indicating that those with constructive life attitudes are more likely to develop higher levels of cognitive competence—particularly in understanding and processing financial information. This, in turn, enhances their confidence and capability to engage in investment-related decision-making.

Cognitive Ability (C) also shows a substantial positive effect on SMP (β = 0.329), underscoring its mediating role in translating life attitudes into actionable investment intentions. This relationship highlights that financial literacy, as a reflection of one’s cognitive capacity, strengthens the link between personal attitudes and participation in financial markets. Individuals with stronger cognitive skills are better equipped to interpret financial signals, manage risks, and identify potential opportunities, which collectively encourage their participation in the stock market.

Moreover, the reflective indicators for SMP (λ = 0.885 and λ = 0.893 for SMP2 and SMP3, respectively) exhibit strong loadings, confirming that the observed measures reliably capture the underlying construct. Overall, the model emphasizes that stock market participation is not solely a product of favorable life attitudes but is significantly reinforced by cognitive capability. These findings align with emerging evidence in behavioral finance suggesting that psychological dispositions and cognitive proficiency jointly determine individuals’ investment behavior, reflecting a more holistic view of financial decision-making processes.

Robustness and Sensitivity Analysis

To ensure the reliability and generalizability of the structural model, robustness analyses were conducted by incorporating socio-demographic control variables and performing subgroup assessments. This approach tests the stability of the relationships among Life Attitude Profile (LAP), Cognitive Ability (C), and Intention to Stock Market Participation (SMP) across different demographic contexts.

The inclusion of demographic control variables—sex, age, educational attainment, and employment status—yielded only marginal fluctuations in the structural path coefficients, affirming the robustness and stability of the model’s central relationships. The structural equation model demonstrated excellent fit to the data (χ

2/df = 1.97, CFI = 0.962, TLI = 0.954, RMSEA = 0.042, 90% CI [0.035, 0.049], SRMR = 0.038), satisfying the conventional thresholds for acceptable model fit (

Hu & Bentler, 1999).

The direct path from Life Attitude Positivity (LAP) to Stock Market Participation Intention (SMP) remained statistically significant (β = 0.28, SE = 0.05, p < 0.001), showing only a minor decline from the uncontrolled model (β = 0.30). Likewise, LAP exerted a strong positive influence on Cognitive Ability (C) (β = 0.45, SE = 0.04, p < 0.001), indicating that individuals with a constructive life outlook tend to exhibit higher levels of cognitive engagement and financial understanding.

Cognitive Ability significantly predicted SMP (β = 0.39, SE = 0.05, p < 0.001), confirming its mediating function. A bias-corrected bootstrapping procedure with 5000 resamples revealed that the indirect effect of LAP on SMP through C was significant (β_indirect = 0.18, 95% bootstrap CI [0.12, 0.25], p < 0.001). The total effect (β_total = 0.46, p < 0.001) indicates that approximately 39% of LAP’s influence on SMP operates through cognitive mechanisms.

Cohen’s effect size estimates reflected small-to-moderate practical significance (f2_LAP → C = 0.12; f2_C → SMP = 0.08), while variance inflation factors were below 2.5, suggesting no multicollinearity issues. The model’s explanatory power increased slightly after controlling for demographics (R2_SMP = 0.496 vs. 0.471 in the baseline model), confirming the model’s stability and incremental validity.

Among control variables, sex significantly influenced investment intention (β = 0.18, SE = 0.06,

p = 0.002), with males exhibiting higher SMP intentions—consistent with prior findings on gendered risk preferences and financial confidence (

Barber & Odean, 2001). Age had a negative association (β = −0.12, SE = 0.05,

p = 0.03), indicating that younger individuals displayed stronger investment intentions, likely reflecting longer investment horizons and receptivity to digital finance innovations. Educational attainment (β = 0.15, SE = 0.06,

p = 0.01) and employment status (β = 0.10, SE = 0.05,

p = 0.04) were both positively associated with SMP, implying that greater financial literacy and income stability enhance investment participation. These findings confirm that the theoretical structure linking positive life attitudes, cognitive capacity, and investment behavior is statistically sound, theoretically coherent, and generalizable across demographic profiles. The mediating role of cognition underscores its importance in behavioral finance as a psychological conduit transforming positive dispositions into tangible financial behaviors.

To further assess the model’s consistency and potential moderating influences, multi-group analyses (MGAs) were performed based on sex (male vs. female) and educational attainment (bachelor’s vs. postgraduate degree). Bootstrapping procedures with 5000 resamples were employed to ensure robust estimation of path coefficients and standard errors, with a significance threshold of p < 0.05. The model demonstrated satisfactory fit indices across groups (SRMR = 0.041, NFI = 0.912, d_ULS = 0.782, d_G = 0.416), indicating strong model adequacy and stability.

The structural relationships exhibited cross-group stability, confirming gender-based robustness (ΔSRMR = 0.004). For male respondents (n = 70), the path from Cognitive Ability (C) → Stock Market Participation (SMP) was slightly stronger (β = 0.42, t = 6.21, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.27, 0.55], f2 = 0.19) compared to females (β = 0.36, t = 5.47, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.21, 0.49], f2 = 0.14). This finding suggests that males rely more heavily on perceived financial competence and analytical reasoning when forming investment intentions, aligning with prior behavioral finance evidence regarding male overconfidence and risk tolerance.

Conversely, the path from Life Attitude and Purpose (LAP) → SMP was stronger among female respondents (n = 125) (β = 0.38, t = 5.83, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.23, 0.50], f2 = 0.16) compared to males (β = 0.31, t = 4.69, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.17, 0.43], f2 = 0.12). This suggests that women’s investment behavior is more influenced by meaning-driven motivations and positive life orientation. Cognitive ability maintained its mediating role in both groups (indirect effect LAP → C → SMP: β = 0.17 [0.08, 0.27], p < 0.001), confirming its universal role as a psychological bridge between attitudinal and behavioral constructs. The R2 for SMP was 0.463 for males and 0.479 for females, indicating that approximately 46–48% of the variance in investment intentions can be explained by the integrated psychological and cognitive constructs. Effect size tests for group differences revealed small-to-moderate differences (q2 = 0.07), suggesting nuanced but meaningful sex-based variations.

When the sample was disaggregated by educational attainment, consistent and significant paths were observed across both subgroups, reinforcing the model’s theoretical stability. For respondents with a bachelor’s degree (n = 120), LAP → SMP (β = 0.33, t = 5.04, p < 0.001) and C → SMP (β = 0.37, t = 5.89, p < 0.001) were both significant, though the coefficients were moderate, suggesting that foundational cognitive and attitudinal development supports investment readiness at this level.

Among postgraduate respondents (n = 32), all path coefficients were higher, indicating stronger psychological-cognitive integration. The LAP → SMP path rose to β = 0.40 (t = 6.14, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.26, 0.52], f2 = 0.17), while C → SMP increased to β = 0.45 (t = 6.78, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.30, 0.57], f2 = 0.21). These increments reflect the amplifying effect of advanced education on financial literacy, critical thinking, and the translation of life attitudes into concrete investment actions. The R2 for SMP was 0.462 for bachelor’s degree holders and 0.495 for postgraduates, indicating that postgraduate respondents’ stock market participation intentions are slightly better explained by the model. The Goodness-of-Fit (GoF) index for the full sample was 0.574, signifying substantial explanatory relevance.

Across all demographic subgroups, the direction and significance of structural paths remained consistent, confirming the robustness and generalizability of the model. Although sex and educational attainment moderated the strength of certain paths, the overall theoretical structure remained intact. Cognitive Ability (C) consistently emerged as the most influential predictor of Stock Market Participation (SMP), underscoring its pivotal role in transforming psychological orientation into financially active behavior.

Males and postgraduates exhibited higher reliance on cognitive competence when engaging in stock market activities, whereas females and bachelor’s degree holders showed stronger attitudinal and motivational influences. The model’s explanatory power remained moderate yet stable across subgroups (R2 range = 0.46–0.50; SRMR < 0.05; NFI > 0.90), demonstrating that the interplay among LAP, C, and SMP is both robust and theoretically generalizable across demographic variations.

4. Discussion

The present study integrates existential psychology and behavioral finance to elucidate how life attitudes and cognitive ability jointly shape investment intentions among young professionals in the Philippines. Beyond documenting empirical associations, the findings contribute to a theoretical synthesis: financial decision-making is not merely a product of information processing or risk–return assessment but also of individuals’ broader sense of meaning, purpose, and psychological orientation toward life.

The significant positive influence of Life Attitude Profile (LAP) on Stock Market Participation (SMP) underscores the role of existential orientation as a foundational motivator of financial behavior. Individuals who maintain a coherent and adaptive outlook on life tend to perceive investing as an extension of their self-development and future planning—an interpretation consistent with self-determination theory (

Deci & Ryan, 2000) and meaning-making frameworks (

Steger et al., 2006). This finding extends traditional behavioral finance models by demonstrating that psychological resources such as optimism, coherence, and perceived purpose can translate into financial engagement, independent of material wealth or demographic endowments. In essence, positive life attitudes foster the psychological capital necessary for proactive financial behaviors, echoing findings by

Lusardi and Mitchell (

2014) and

Stolper and Walter (

2017) that cognitive and affective dispositions mutually reinforce financial participation.

The nuanced effects observed across LAP subdimensions invite deeper theoretical reflection. The negative association between Life Purpose (LP) and investment intention suggests that a well-defined purpose may not uniformly promote financial risk-taking. Drawing from goal-content theory (

Kasser & Ryan, 1996), purpose-driven individuals may pursue intrinsic goals (e.g., education, family, altruism) rather than extrinsically motivated ventures such as speculative investing. This implies that strong purposiveness can yield financial conservatism when investment is perceived as inconsistent with one’s broader value orientation. Conversely, Death Acceptance (DA) emerged as a strong positive predictor of SMP, aligning with terror management theory (

Pyszczynski et al., 1999), which posits that confronting mortality fosters a search for symbolic immortality through achievement and legacy-building. Investment behavior, in this sense, becomes an existential expression of continuity and agency. Similarly, Goal Seeking (GS) reinforces the instrumental role of future orientation, supporting temporal motivation theory (

Steel & König, 2006): individuals who anchor their lives on clear, future-oriented goals are more likely to perceive investment as a strategic means of goal attainment.

In contrast, non-significant effects for Existential Vacuum (EV), Life Control (LC), Will to Meaning (WTM), and Future Meaning to Fulfil (FMF) suggest that meaning-related orientations alone are insufficient to trigger financial engagement unless cognitively reinforced. This observation resonates with dual-process models of decision-making (

Kahneman, 2011), wherein affective and existential dispositions (System 1) must be complemented by analytical competence (System 2) to produce deliberate economic action. Thus, existential attitudes provide motivational direction, but cognitive ability determines execution.

Indeed, the mediating role of Cognitive Ability (C)—proxied by financial literacy—illuminates this interplay between motivation and cognition. The results affirm that adaptive life attitudes foster cognitive engagement, supporting theories of lifelong learning motivation (

Seligman, 2011) which emphasize that individuals with a constructive worldview actively seek knowledge that enhances competence and autonomy. Cognitive ability, in turn, translates meaning-driven dispositions into concrete financial actions by enabling individuals to process risk information, assess returns, and make informed investment choices. This dual-path mechanism supports the emerging consensus that psychological and cognitive determinants of financial behavior are interdependent rather than competing explanations (

Tang & Baker, 2016;

van Rooij et al., 2011).

The integration of existential and cognitive perspectives advances a holistic behavioral finance framework: investment intention is a function of both meaning (why one acts) and competence (how one acts). This synthesis reframes financial literacy as not only a technical proficiency but also a cognitive manifestation of one’s existential orientation toward agency, purpose, and control. Individuals who derive meaning and coherence from life are more likely to develop the cognitive scaffolding required for prudent financial behavior, illustrating how psychological wellbeing underpins economic rationality.

Demographic analyses further contextualize these relationships. Consistent with the gendered risk preference literature (

Barber & Odean, 2001), males displayed stronger reliance on cognitive ability, reflecting overconfidence and analytical engagement, while females’ investment intentions were more strongly predicted by meaning-driven orientations. This divergence underscores the importance of gender-sensitive approaches to financial education, where women’s motivational pathways may be more relational or purpose-centered. Likewise, the amplifying effect of educational attainment on both cognitive and attitudinal paths supports the human capital theory of financial literacy (

Becker, 1975): higher education enhances not only analytical skill but also metacognitive awareness linking personal goals with financial strategies.

Theoretical implications extend beyond demographic boundaries. By confirming that existential orientation can predict cognitive readiness and financial participation, the study challenges reductionist models that view financial behavior solely through economic rationality. Instead, it posits a meaning–cognition–behavior continuum, where individuals’ sense of life purpose catalyzes cognitive engagement, which in turn facilitates investment behavior. Such a framework offers fertile ground for future interdisciplinary inquiry connecting existential psychology, positive economics, and behavioral finance.

This study contributes a theoretically integrative perspective on financial behavior. It demonstrates that fostering stock market participation among young adults requires not only enhancing financial literacy but also cultivating life attitudes that promote purpose, coherence, and adaptive openness to uncertainty. Investment, therefore, is not purely a rational act of wealth maximization but also an existential act of self-extension—a manifestation of how individuals seek to translate meaning into tangible engagement with the economic world.

Limitations of the Study

While this study offers valuable insights into the interplay between life attitude profile (LAP), cognitive ability (C), and intention toward stock market participation (SMP) among Filipino respondents, several limitations should be acknowledged to appropriately frame the interpretation of its findings. First, the use of self-reported data may introduce response biases and inaccuracies arising from subjective perceptions or social desirability tendencies, despite efforts to ensure anonymity. Moreover, the cross-sectional design restricts causal interpretation, as it captures the relationships among LAP, cognitive ability, and SMP at a single point in time. Longitudinal research could better capture how these factors evolve and interact over time.

Second, the absence of a marker variable to test for common method variance (CMV) represents another methodological limitation. This approach was not feasible given the reliance on previously validated and theoretically grounded constructs. Nevertheless, the combination of procedural and statistical remedies—specifically, Harman’s single-factor test and variance inflation factor (VIF) assessment—provided sufficient evidence that CMV was not a major threat to the validity of the findings. Future research may consider incorporating a theoretically unrelated marker variable if instrument customization allows, as recommended by

Podsakoff et al. (

2003).

Third, the sample composition—primarily Filipino young professionals from the province of Bulacan—offers contextual depth but may limit the generalizability of the findings beyond this demographic group. Young professionals in other Philippine regions may differ in socioeconomic background, financial access, and cultural influences, potentially leading to variations in investment attitudes and behaviors. Likewise, cultural, socioeconomic, and institutional differences could further influence investment decisions in other national contexts. Although demographic controls such as age, sex, educational attainment, and employment status were included, unobserved factors—such as risk tolerance, financial experience, or income—may still affect the results. Future studies are encouraged to incorporate these variables and adopt broader, multi-regional, or cross-country comparative designs to enhance external validity.

Finally, the absence of local adaptation or pilot testing of the Life Attitude Profile–Revised (LAP-R) for the sampled population is also a limitation. The instrument was used in its original English version, following prior applications in international research with comparable constructs. Nonetheless, future studies are encouraged to conduct cultural adaptation and pilot testing to ensure measurement equivalence and contextual sensitivity across diverse Filipino samples (

Beaton et al., 2000;

van de Vijver & Leung, 2011). Despite these limitations, this study meaningfully contributes to behavioral finance research by illuminating how psychological and cognitive dimensions influence investment intentions within the Philippine context.

5. Conclusions

This study examined the influence of Life Attitude Profile (LAP) and Cognitive Ability (C) on individuals’ intentions toward Stock Market Participation (SMP) within the Philippine context, focusing specifically on young professionals in the province of Bulacan. Anchored in the theoretical frameworks of behavioral finance and existential psychology, the study sought to understand how psychological orientations and cognitive competence jointly shape investment behavior. The investigation further explored whether cognitive ability mediates the link between life attitude and investment intention.

The findings revealed that young professionals in Bulacan who exhibit a stronger sense of life purpose, greater goal-seeking tendencies, and an overall positive outlook toward life are more inclined to participate in stock market investments. Cognitive ability—proxied by financial literacy—emerged as a key mechanism reinforcing this relationship. This suggests that while an individual’s psychological readiness and positive life perspective are vital, these factors must be supported by sufficient financial knowledge and analytical capability to translate intentions into informed investment behavior. Robustness tests that accounted for demographic controls such as sex, age, educational attainment, and employment status confirmed the consistency of these relationships across different subgroups within the sample.

These results underscore that financial behavior among young Filipino professionals is not solely an outcome of economic rationality but is deeply embedded in psychological and cognitive dimensions. The study reinforces the growing body of behavioral finance literature emphasizing that investment intentions are shaped not only by access to financial resources but also by an individual’s sense of meaning, self-efficacy, and cognitive preparedness.

Contextually, the findings highlight that in Bulacan—an emerging urban hub where retail stock market participation remains limited—strengthening both cognitive and psychological foundations may be key to fostering more active financial engagement. Tailored financial literacy programs that integrate personal development, goal setting, and value-based learning can cultivate more confident, purpose-driven, and financially responsible investors. Such interventions could contribute to broader national efforts to deepen retail participation in capital markets and enhance financial inclusion in the Philippines.

The study offers novel insights within the Philippine financial–sociocultural context, where young professionals navigate a digital ecosystem marked by simultaneous exposure to formal investments and speculative instruments. This unique landscape amplifies both the opportunities and psychological pressures of financial decision-making. The Philippine case highlights the contextual grounding of behavioral finance: individuals’ financial actions are shaped not only by rational considerations but also by existential motivations and culturally mediated cognitive development. The results also underscore the need to contextualize behavioral finance theories within emerging economies, where socio-cultural dynamics, economic volatility, and differential access to financial literacy programs shape the psychology of investment. By integrating existential attitudes with cognitive functioning, the study contributes a more human-centered framework for understanding financial participation among early-career populations in developing contexts.

From a policy and educational perspective, the confirmed mediating role of cognitive ability suggests that financial literacy interventions should transcend mere dissemination of factual investment knowledge. Programs must cultivate higher-order reasoning, analytical problem-solving, and structured decision-making skills—capacities that enhance individuals’ ability to translate positive life attitudes into prudent financial engagement (

Lusardi & Mitchell, 2014). Investor education initiatives should also incorporate psychological and attitudinal components, such as life-purpose reflection and self-efficacy development, to foster a holistic orientation toward financial well-being (

Xiao & Porto, 2019).

The unexpected negative relationship between Life Purpose and stock market intention invites a recalibration of meaning-oriented constructs within financial psychology. Future studies should explore whether a strong life purpose redirects individuals toward non-material pursuits or whether moral or existential considerations suppress engagement in speculative markets. Mixed-method approaches combining structural modeling with qualitative inquiry (e.g.,

Wong, 2013) could yield richer interpretations of these patterns. Moreover, the relatively modest reliability coefficients for Will to Meaning and Future Meaning to Fulfill highlight the need for refined psychometric instruments, possibly via item revision or advanced modeling techniques such as item response theory (

DeVellis & Thorpe, 2021). Longitudinal and cross-cultural designs are also warranted to examine how existential and cognitive determinants of financial behavior evolve over time and across institutional contexts (

Grable & Lytton, 1999).

This study contributes to the intersection of psychology and finance by demonstrating that investment intentions are not solely products of rational calculation but are shaped by the individual’s sense of meaning, life orientation, and cognitive preparedness. By recognizing these human dimensions of financial decision-making, stakeholders—from policymakers and educators to financial institutions can design more holistic strategies that empower individuals to participate more meaningfully and confidently in the capital market.