3. Literature Review

Resilience, in the context of ESG and Internal Audit, is defined as an organization’s ability to adapt to shocks, maintain critical operations, and sustain stakeholder trust while navigating regulatory, environmental, and market disruptions (

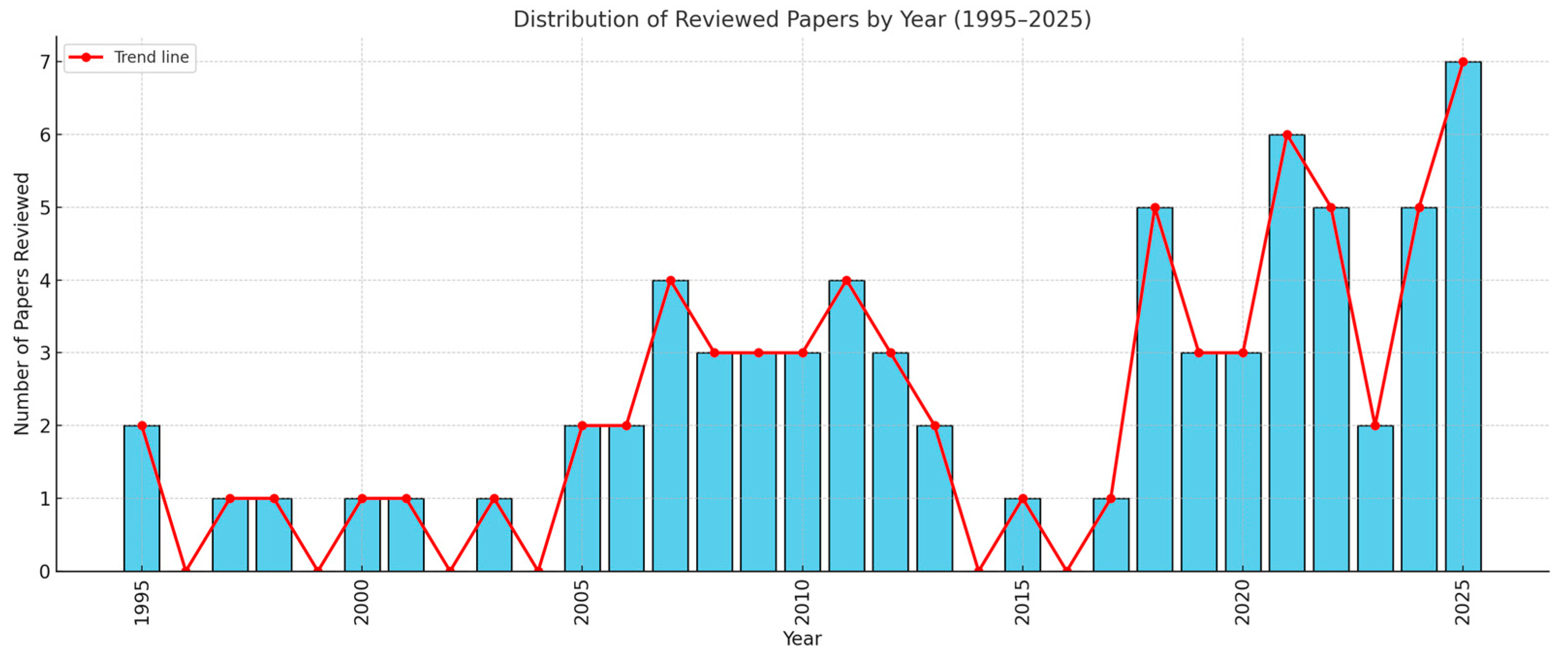

Wang et al., 2023). Internal Audit contributes to resilience by identifying emerging ESG-related risks, ensuring robust controls and verifying that sustainability initiatives translate into long-term value creation. A review of academic papers is presented in the following chapter to demonstrate whether environmentally, socially, and politically responsible practices add value for investors and companies alike. Over a long period of time, ESG factors are directly correlated both with a company’s financial performance and risk profile.

To determine ESG performance, two concepts need to be intersected and interacted with: Corporate responsibility (CR) and sustainable and responsible investment (SRI). According to

Freeman and Dmytriyev (

2017), corporate social responsibility is defined as voluntary actions by businesses to improve their social and environmental performance. Intangible assets created by CR are linked to a company’s long-term performance, which are boosted by operational and reputational benefits.

By investing in the CR process, a company creates a form of an intangible asset, which relates to the long-term performance of operations and reputation. The operational benefits because of the company’s internal business activities (i.e., cost reduction, operating efficiency, and productivity) are likely to be relatively uncertain about their future success and slowly to materialize. At the same time, all CR is a potential source of positive attitudes (e.g., reputational benefits) towards a company, which indirectly affect future earnings through a positive image related to an increase in sales, a lower cost of capital, acquisition and retention of skillful employees, and willingness to pay higher prices or to buy/hold the stock of a company.

Corporate responsibility (CR) is thus implemented through the application of stakeholder theory, which delineates the parties holding interests in a corporation and attempts to align their concerns with the company’s profit-oriented objective. In general terms, these corporate stakeholders include customers, suppliers, shareholders, employees, communities, special interest groups, NGOs, and regulators. The contemporary understanding of CR has evolved into three main dimensions of stakeholder engagement: environmental, social, and governance (ESG). For instance, enhancing employee contentment can positively impact employee retention, motivation, and foster innovation in terms of new products, patents, and agreements. This, in turn, can yield lasting performance improvements that benefit shareholders (

Edmans, 2011).

Embedded within the scope of corporate social responsibility is the concept of corporate governance. Academic research often gauges its effectiveness as a gauge for the extent of shareholders’ rights, ensuring that board members and executives prioritize the long-term interests of shareholders (

Gompers et al., 2003). An illustration of this is seen through the promotion of independent decision-making processes carried out by a capable, diversified, and autonomous board. Additionally, it involves aligning board of directors’ compensation with both individual and company financial targets and key performance indicators, while also establishing vital board committees.

Khaw et al. (

2024) emphasize further that governance mechanisms, especially board diversity and strong governance approaches, are decisive in the ESG outcomes. This corresponds directly with Internal Audit in its assurance and advisory roles within the governance ecosystem, providing Internal Audit as a mechanism for resilience and credible ESG integration.

All in all, the implication of the CR framework is that the ESG elements, considered as separate intangible factors, could influence an anticipated future earnings stream of a company and a risk landscape on that company. This view validates the essence of extra-financial performance in setting the stage for impacts on stock prices, which is actually the semblance of the valuation theory.

Methodologically, innovative approaches such as entropy-weighted TOPSIS have recently been applied to assess ESG contributions to organizational performance, offering replicable insights into how governance and environmental factors generate measurable value (

Zournatzidou et al., 2025).

Khaw et al. (

2024) identify seven clusters of factors—digital transformation, financial strategies, governance approaches, board diversity, organizational excellence, sustainability focus, and risk management—as key determinants of ESG performance. This highlights the complex, multifaceted nature of ESG and provides additional reason to pursue targeted research, like this study which examines how Internal Audit contributes to sustainability, resilience, and value generation.

Socially Responsible Investment (SRI) refers to an investment strategy that integrates Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) factors with financial goals during the decision-making process (

Renneboog et al., 2008). Within the SRI stock market, a common classification distinguishes between a values-driven segment and a profit-seeking segment, characterized by specific investment screens employed in portfolio construction (

Derwall et al., 2005). The values-driven segment typically involves investors adhering to ethical criteria unrelated to a company’s future earnings.

Hong and Kacperczyk (

2009), observed that values-driven SRI strategies tend to render controversial stocks (those associated with industries such as alcohol, tobacco, gambling, military, firearms, etc.) cheaper while offering higher expected returns. This phenomenon introduces market inefficiencies when these ‘sin stocks are traded at prices below their fundamental values. Notably, they identified superior abnormal risk-adjusted returns as compensation for the additional market risk associated with high litigation risk.

Recent research has shed light on the profit-seeking segment of the SRI stock market, where investors incorporate ESG considerations into fundamental valuations to pursue traditional financial objectives. This approach involves positive screens favoring stocks with high ESG scores for portfolio construction.

Derwall et al. (

2005), found that portfolios comprising high-ranked, eco-efficient stocks deliver higher abnormal risk-adjusted re-turns due to short-term market mispricing, specifically an underestimation of ESG factors (market inefficiency). Consistent with this,

Greenwald (

2010) and

Borgers et al. (

2013) demonstrated that ESG stocks more frequently surpass earnings estimates and analyst forecasts.

Furthermore,

Derwall et al. (

2011) argued that this market inefficiency diminishes as the market becomes aware of the impact of ESG factors on expected future cash flows. Tests of errors in the expectations hypothesis revealed that abnormal risk-adjusted returns associated with strong employee relations decrease as the evaluation horizon lengthens, reflecting investors’ improved understanding of future earnings expectations.

Bebchuk et al. (

2013) introduced the concept of the learning and disappearing effects of governance on abnormal returns, showing that good governance ceases to be associated with abnormal returns once it becomes fully priced into stock values. Both the learning hypothesis and errors in the expectations hypothesis align with the traditional efficient market view, which posits that stock prices fully incorporate all publicly available information, including ESG data.

In 2012, the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) reported nearly 1100 global signatories overseeing over $32 trillion in assets under management, all of whom have policies addressing ESG considerations in their investments. Notably, mainstream investors constitute a substantial majority of PRI signatories, accounting for 73 percent. With the growing prominence of the UN PRI and its focus on ESG integration, there is a heightened need for a profound understanding of the material impact of ESG factors on corporate financial performance, which is becoming increasingly important for both investors and companies.

In summary, the SRI concept suggests that the preference for stocks with high ESG ratings among investors is driven by a wealth-maximizing effect arising from the positive influence of ESG actions on future earnings, as well as the optimistic market expectations shaped by both institutional and individual investors, transcending mere financial re-turns. Abnormal trading profits related to ESG are expected to persist until market participants fully comprehend the disparities in financial returns between ESG leaders and laggards and incorporate this knowledge into fundamental valuations.

Building on the above literature linking ESG to corporate value, Internal Audit (IA) is discussed in the literature as a pivotal governance mechanism for embedding sustainability into strategy, risk management, and reporting. In line with stakeholder and governance perspectives, IA’s involvement is articulated through three integrated pillars that support ESG implementation, assurance, and resilience. The term sustainability can be translated into a very familiar financial term: going concern. In finance, going concerns the ability of an organization or corporation to survive for the foreseeable future. In this context, however, it refers to the ability to continue operating for years to come.

According to the UNESCO definition and the Risk in Focus 2022 report—published by the ECIIA—the Sustainability challenge can also be divided into three major concepts (

Instituut van Internal Auditors, 2022):

The sustainability of the environment:

An organization’s ESG performance is determined by criteria such as sustainability, responsibility, or ethics. Environmental, Social, and Corporate Governance is the abbreviation for ESG. A company’s ESG performance can be evaluated using ESG indicators through its investment philosophy and evaluation criteria. Decisions are made based on traditional financial information as well as non-financial indicators such as environmental, social, and corporate governance.

E stands for Environment, which refers to indicators related to natural environments and ecological cycles.

S stands for Social Responsibility’, which refers to indicators related to society’s rights, benefits and interests reflected by external leaders, employees, customers, shareholders and communities.

G stands for Governance indicators, which pertain to corporate governance. A focus is placed on the structure of corporate governance, market transactions, intellectual property, and other aspects of corporate compliance management for project in-vestment companies.

This review goes beyond summarizing existing works by synthesizing how Internal Audit acts as a bridge between ESG implementation and organizational resilience. Specifically, it highlights IA’s unique role in risk mitigation, governance assurance, and combating practices such as greenwashing areas often overlooked in prior reviews.

This view is reinforced by

Martiny et al. (

2024), who find that the determinants of environmental, social and governance performance are not homogeneous. Their review shows that while governance factors are often shaped by internal firm-level structures, environmental and social dimensions are strongly influenced by external regulatory and stakeholder pressures. This distinction validates the need for internal audit functions to tailor their assurance and advisory roles differently across the three ESG dimensions.

Sustainability and organizational life have evolved over time. Sustainability in organizations is typically defined by the impact they have on their environment. Organizations that are sustainable—especially businesses—focus on assessing and improving their operational impact, thereby addressing society’s most pressing concerns: climate change and pollution, depletion of natural resources, inequality in the economy, societal injustices, etc. (

Fedele, 2021). Despite some commentator’s cynicism that such efforts are more aimed at influencing an organization’s image among stakeholders than the substantive impact of sustainability change measures, there has now been a shift in favor of substance over form (

Instituut van Internal Auditors, 2022).

Environmental sustainability is a challenge that organizations are adapting to at different stages, and the IA functions they require will reflect those differences. Deloitte’s report in 2022 shows that some businesses are already much ahead of their competitors. According to Deloitte’s survey of CxO Sustainability leaders in 2022, 19 percent of the respondents are implementing at least four or five of the following ‘needle-moving’ actions (

Deloitte, 2022):

Developing products or services that are climate-friendly;

Specifying sustainability criteria for suppliers and business partners;

Making facilities more climate resilient by updating or relocating them;

Including climate considerations in lobbying and political donations;

Incorporating sustainability performance into senior leader compensation.

While many businesses recognize their role in contributing positively to sustainability, they are not always able to articulate that role in terms that their shareholders will find persuasive and acceptable as reasons to continue investing. Using IA from many angles—strategic, operational, and investment—can help management find the business case for addressing ESG risks and opportunities.

Further recent evidence shows that while ESG engagement reduces systematic risk, it also improves value outcomes of broader corporate actions such as diversification, thus addressing the core issue of resilience within the organization (

De la Fuente et al., 2025).

Beyond ensuring compliance with regulations and fulfilling legal obligations, IA professionals can support their organizations meet the sustainability challenge. Obtaining the knowledge and becoming positioned as sustainability IA experts requires both time and effort. Internal auditors must now be retrained and rebranded to focus on sustainability risks along with the traditional issues of financial, operational, and compliance risks. Therefore, IA individuals can engage in deeper conversations with their stakeholders and better understand their sustainability and environmental agendas. There may be some practitioners who are less well equipped to steer a professional dialog around such issues as they act in the best interest of their employer organizations, but there is still room for all to build meaningful relationships with stakeholders.

It is the role of IA to both catalyze and investigate how organizations are living up to their sustainability promises as a profession according to

Fedele (

2021).

Having high-level connections and perspectives, yet the ability to perform very detailed work too, is precisely the expertise that can help to ensure the strategic aspects of sustainability planning are dealt with at an operational level.

IA is uniquely connected to both executive and non-executive directors. The internal auditor’s independence and impartiality, along with their commitment to assurance, ensure that reports regarding sustainability compliance and results are accurate and honest. Internal audit experts can enhance organizational performance by providing consultancy services that add meaningful value.

Recent evidence shows that, when firms face negative ESG media coverage, they respond by raising the quality of sustainability assurance to repair legitimacy. Moreover, effective boards (more independent, active, with non-duality) amplify this response, indicating a complementary role between governance and assurance in legitimacy recovery. These findings reinforce IA’s positioning within the broader three-line model: IA’s readiness reviews and control testing underpin credible assurance responses to ESG crises (

García-Meca et al., 2024).

The IA philosophy of being systematic, methodical and disciplined is also vital to having comprehensive and multidisciplinary approaches to assessing the management and control of the strategic goals on sustainability.

Recent evidence from the European energy sector further underscores that the internal audit department reporting structure strongly influences ESG-driven performance outcomes, with governance emerging as the most significant driver among ESG dimensions (

Zournatzidou et al., 2025).

Environmental sustainability will be a challenging journey for many organizations. In the next three to five years, it is anticipated that certain classes of businesses may require up to 25 percent of IA time to address matters of ESG reporting and related compliance matters (

Audit, 2021). The importance of data, risk, and control will become more apparent for all organizations as they pursue environmental sustainability—and ESG reporting more generally (

Audit, 2021). Internal Audit can—and must—play a role in the organization’s ESG development process as a result of this increasing importance and the need for a substantiated and controlled approach.

The Internal Audit activity must evaluate and contribute to the improvement of the organization’s governance, risk management and controls processes using a systematic, disciplined, and risk-based approach. In order for internal audit to be credible and valuable, auditors should be proactive, provide new insights, and take into account how their evaluations will impact future outcomes (

IIA, 2017).

The importance of acquiring the knowledge to position IA professionals as experts in the field—particularly related to governance, risk management, and internal control—but also covering emerging regulations and sector-specific policies—cannot be overstated. As a Sustainability Business Partner, IA uses that knowledge to help the business transition and address risks (

Draaijer, 2012). It is the goal of the business and IA to align their sustainability strategy with near market demands as well as more distant stakeholder demands, like those of financiers and regulators. Investing in sustainability will not always return a profit in the short- and even medium-term, but they will lay the foundation for continued operations and add value as investors view intangible assets (

Draaijer, 2012). Besides challenging the organization’s strategic position, IA must also assess if the organization has the right KPIs and risk measures in place, as well as challenge how business processes actually work in reality. Measurement and reward mechanisms should reflect the incentives for adhering to recommended ways of working effectively. ESG data accuracy is at the core of these critical measurements (

Draaijer, 2012).

Involving IA early in the planning and design phases enables the evolution of data, information and technology landscapes to be fit for sustainability change to be achieved much more accurately than when IA is not involved. After the strategy, business model, technology, output data, and information challenges are addressed, IA continues to play a role in making sure sustainability is integrated into its charter, audit universe, risk assessment, and audit plans, to spot subtle exceptions and nuances that may undermine the good work of sustainability efforts (

Draaijer, 2012).

Many organizations will find themselves on a path to sustainability maturity, moving from conformance to performance to greater value creation—perhaps starting by satisfying the basics, then moving on to being a more mature, innovative or leading organization. Interventions and reporting requirements from IA will evolve along that journey, which means a different team make-up along the way. Organizations need IA to perform a variety of functions, from identifying gaps between strategy and execution to living up to sustainability expectations on a daily basis. The Internal Audit will be able to enhance its standing and credibility within the organization even further by leading thought leadership on a new topic, emphasizing the connection between strategy, risk management, and controlled processes, and riding the momentum of sustainability. A drive toward sustainability provides an opportunity for the organization and society to gain more value.

On a practical level, we see that IA’s role can develop through three integrated pillars, from knowledge to business partnering to full sustainability integration within IA activity.

To improve IA’s capability, knowledge, and expertise, the team must, as part of its continuing professional development, seek to understand the data, technology, and culture surrounding sustainability, and assess where improvements are needed (

Draaijer, 2012).

Staying up to date on sustainability-related regulations and requirements is essential. By researching and reviewing regulations, training periodically, incentivizing the team to attend courses, and reaching out to the broader internal audit community, first- and second-line internal auditors, and external experts, this can be accomplished.

Often, IA needs to challenge the business on aligning its sustainability strategy and process-level activities, including risk management. It is clear that this requires a deep understanding of the company’s sustainability mission, strategy, performance, and poli-cies on risk management. Managing organizational risks requires the Internal Audit team to work closely with first-line staff (those responsible for risk management) and second-line staff (those responsible for risk management and compliance). The IA team will be able to assess how they are integrating sustainability into their operations, and make the best use of all functions’ skills and expertise by engaging with the first and second lines. Sustainability risk management can even be used as a flagship opportunity for IA to align the three lines of control.

The Sustainability Business Partner role requires comprehensive engagement at all levels of the organization. As a result of such business partnering, the control environment will be more robust, the reporting will be more relevant, and the outputs will be more reliable, since it will be matched to market expectations and regulatory requirements (

Fedele, 2021), including those required for external audits.

Because of the nature of the function, the IA is unique in its ability to deal with both executive and non-executive directors and offer independent views into governance, risk management, and control processes of an organization. To effectively identify and reduce risks while establishing improvements, the team needs to participate early in the strategy formulation process at the top level to maximize their influence.

After marshaling the knowledge and positioning the IA unit as the Sustainability Busi-ness Partner, the next step is to ensure that all internal audit activities consider sustainability. Organizational sustainability needs and ambitions should be reflected in the audit charter and audit universe, and sustainability risks should be incorporated into the audit plan’s risk assessment, which must address sustainability within the governance, risk management, and operational risk domains (

Fedele, 2021).

In other words, to find the right balance between incorporating the topic in regular operational audits, perform thematic activities and consulting engagements (e.g., on the field of setting up the sustainability risk management framework of an external audit readiness assessment). The internal audit plan itself should be dynamic, to ensure a continuous process of adaptation as the sustainability agenda evolves and the company’s response changes accordingly.

These three pillars work alongside each other. Continually investing in sustainability and ESG knowledge-building qualifies IA to live up to its partnering role by delivering IA activity in an integrated way, staying ahead of changes to legislation, and anticipating on how such changes will impact the company’s strategy and culture. Likewise, as an organization matures, its IA function will adapt to reflect that maturity.

As the Sustainability Partner requires both knowledge being built up in pillar one, and the insights gained through execution of the internal audit program that is set up in the third pillar, linking the information gained from different angles and connecting this to the company’s forward looking sustainability strategy and objectives will help the In-ternal Audit department fulfill its mission to provide meaningful advice and insight, in order to show its organizational value and becoming a catalyst for change.

Furthermore, Internal Audit serves a growing role in guarding against greenwashing by ensuring that ESG disclosures are true and matured along with changing regulatory frameworks such as EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) and U. S. SEC climate disclosure rules. Internal Audit plays a crucial part in both meeting compliance requirements and supporting the confidence of stakeholders.

Studies suggest that the core aspects of internal auditing vary according to the situational environment. Integration in a high-risk, heavily regulated environment may come with greater compliance costs, with increased levels of scrutiny, and thus negatively impinge upon the short-term profitability of an entity (

Semenova & Hassel, 2016;

King & Lenox, 2001;

Heal, 2005;

Telle, 2006;

Cho & Patten, 2007).

By contrast, service and low-risk industries more readily convert partnering and knowledge-building into operating benefits and reputation gains. Geographic context also matters studies in developed markets often document stronger ESG–performance links than studies in some emerging markets (e.g.,

De Lucia et al., 2020 vs.

Garcia & Orsato, 2020;

Duque-Grisales & Aguilera-Caracuel, 2021). Finally, methodological choices (market-based metrics such as Tobin’s Q vs. accounting-based ROA/ROE) can lead to different inferences about timing and magnitude of value creation (

Semenova & Hassel, 2008).

By implementing ESG principles, companies can use resources more efficiently and innovate their businesses more effectively, resulting in higher profits and market value. According to the resource-based perspective and Porter hypothesis, environmental management contributes to a company’s competitiveness by improving its products and processes, which in turn also result in a dynamic increase in profits (

Porter & van der Linde, 1995) and (

Lundgren & Olsson, 2009). As a result of ESG investments, there are fewer explicit costs associated with them (such as penalties and taxes), according to stakeholder theory. Furthermore, ESG practices improve relationships with stakeholders, which lead to higher operating efficiency, higher employee productivity, a larger customer base, and a greater reputation among stakeholders. There is also a theory that stock prices, employee commitment, and consumer demand are influenced by ESG performance rather than the actual efforts (

Margolis et al., 2009). Value-creating schemes and CR contribute differently to operating performance, but positively to market value. Furthermore, companies with better corporate governance are highly rewarded by the markets based on their share-holder wealth.

However, recent research highlights critical limitations in ESG assurance practices.

Aobdia and Yoon (

2025) find that auditors often fail to integrate financially material ESG incidents into their evaluations of internal control over financial reporting (ICFR), which results in overly optimistic audit opinions and a higher likelihood of financial restatements. This evidence underscores persistent weaknesses in external ESG assurance and amplifies the relevance of internal audit in strengthening ESG-related risk monitoring and governance.

Since many studies compare return differentials between companies with high and low ESG scores or conventional companies, the relations have also been investigated based on the specific characteristics of leading ESG companies. As

Artiach et al. (

2010) found, ESG leaders are large, visible companies. The most profitable ESG companies have higher returns on equity (ROE) and greater growth potential (

Artiach et al., 2010). Companies with a substantial number of environmental and social policies that are highly sustainable are more likely to assign sustainability responsibility to their board of directors. In addition, executive compensation should be determined by ESG metrics, a formal stakeholder engagement process should be established, long-term orientation should be shown, and non-financial information should be measured and disclosed more frequently.

In terms of direct environmental impacts, environmental standards, levels of environmental performance, risk profiles, and stakeholder pressure, environmental differences are primarily determined by industry context. A high-risk or pollution-intensive industry, such as pulp and paper, utilities, energy, and mining, faces greater environmental demands and public pressure than a sector with low direct environmental risks, such as banking, software, or insurance (

King & Lenox, 2001;

Heal, 2005;

Telle, 2006;

Cho & Patten, 2007).

Cross-sectional differences extend beyond environmental risk intensity. In controversial industries and in loose cultures, firms are more likely to escalate assurance quality after ESG controversies, whereas in tight cultures the assurance response is weaker pointing to institutional context as a source of heterogeneity in observed ESG performance relations (

García-Meca et al., 2024).

Semenova and Hassel in their research papers in 2008 found that low-risk industries have lower market values, but higher environmental management scores and better operating performance than companies in high-risk industries. KLD, GES, and ASSET4 ratings indicate strong environmental performance in high-risk industries (

Semenova, 2010).

Ramiah et al. (

2013) found that environmental regulations lead to market uncertainty and changes in long-term systemic risk.

The impact of ESG on firm value and profitability has been documented in a number of studies. During the 1970s, researchers began searching for a link between corporate financial success and ESG standards. According to the researchers, about 90% of studies indicate that ESG impacts firm financial performance positively after reviewing 2200 papers. Based on a meta-analysis of 132 publications in reputable journals, 78% of papers showed a positive correlation between sustainability and financial performance (

Alshehhi et al., 2018).

There are a variety of variables that influence a company’s financial performance, including its performance on ESG issues (e.g., company size, market risk, and R & D investments). In addition to capturing the intangible value of the stock market beyond its book value, market-based measures, such as Tobin’s Q, also reflect the market’s perception of both potential and current profitability. Return on assets (ROA) and return on equity (ROE) are accounting-based measures that reflect a historical perspective and estimate the company’s financial performance. It is often considered beneficial to combine market- and accounting-based measures in these studies. In their article in 2008, Semenova and Hassel examined the relationship between environmental performance and financial performance. Further, environmental preparedness and performance are decomposed into two dimensions of company environmental opportunities. Market value (Tobin’s Q) and operating performance (ROA) are positively related to environmental preparedness and performance. According to the authors, adding an industry focus reveals that environmental preparedness brings benefits that go beyond incremental improvements in company performance. Operating and reputational benefits result from environmental performance of management. Based on the results of this study, environmental preparedness and performance may have different incremental effects on operating performance and market value.

Using two different indicators of environmental performance, policy and management, and financial performance,

Semenova and Hassel (

2008) investigate the moderating effects of environmental risk within the industry. In this article, the authors argue that the industry factor is highly relevant for investors due to the differences in material risks associated with climate change, energy consumption, waste management, and environmental laws. The implementation of proactive environmental performance management in a high impact industry is costly and company-specific, whereas it is easy to emulate and less resource-demanding than implementing environmental performance policies, such as environmental reporting. According to the results, the form of the relationship between environmental policy and management and operating performance is influenced by environmental risk for the industry, but the degree of the relationship between environmental variables and market value is influenced by the risk factor.

Due to a negative relationship between environmental management and return on assets, environmental management is particularly costly in high-risk industries like oil and gas and utilities. There is a positive correlation between environmental policy and ROA in low-risk industries and a weaker correlation in high-risk industries. Tobin’s Q is a measure of the relationship between environmental policy and management and the market’s discount factor, leading to a lower market value in high-risk industries and a stronger effect in low-risk industries. According to the results, the impact of environmental policy and management on profitability and market value is related to the level of environmental industry risk, which masks the universal perspective.

In the Chinese market, strong ESG performance augments stock liquidity especially through reduction in firm-specific risk and in the reinforcement of stakeholder support, according to

Wang et al. (

2023). Their findings provide the most recent evidence that ESG not only increases firm valuation but also enhances market efficiency and therefore is directly relevant to the risk–return framework.

Both aggregated and sub-aggregated value relevance of environmental performance is supported by the Ohlson valuation model applied by

Semenova et al. (

2010). According to the results, social performance indicators are positively related to market value for communities and suppliers. It is concluded from this study that third party environmental and social performance ratings contain valuable information for investors. Intangibles such as environmental and social performance have a relatively weak impact on company value. In conclusion, this paper argues that integrating extra-financial value into traditional investment analysis improves long-term performance.

In terms of corporate governance indices,

Gompers et al. (

2003) and

Bebchuk et al. (

2013) find that good governance correlates with firm value (Tobin’s Q) as well as operating performance (ROA, sales growth, and net profit margin). The parameters on the governance indices have remained stable over the period 1990–2008, both in magnitude and statistical significance.

Taken together, results on governance and value are consistent with new evidence that board effectiveness and high-quality sustainability assurance act jointly to defend reputational capital under ESG scrutiny—an interface where IA’s advisory and assurance-readiness work is pivotal (

García-Meca et al., 2024).

The impact of ESG performance on firm risk is also expected to be considered as part of the valuation framework. Generally, lower risk factors lead to lower capital costs or shareholder returns. Due to this, investors can apply a lower rate of return or discount rate to expected future earnings, thus increasing market value. A high ESG performance company is likely to be perceived by investors as having a low level of risk associated with future litigation and/or abatement expenditures. Over the period 1992–2007,

El Ghoul et al. (

2011) examine the effect of CR performance ratings on the cost of capital. Evidence from implied cost of capital models indicates that lower equity capital costs are related to better CR performance. A significant correlation has been found between CR and capital costs in recent years (2000–2007) compared to 1991–1999, and CR categories such as employee relations, environmental performance, and product strategies are more significant in influencing a company’s capital costs.

Building on this,

Q. Li and Gu (

2025) provide more recent evidence from China, showing that green credit policies improve corporate performance through a chain mediation mechanism in which enhanced ESG scores reduce firms’ cost of debt capital. Their findings highlight how ESG can serve as a measurable link between sustainable financing tools and firm value creation, offering a clear pathway for assessing the added value of ESG initiatives.

Researchers have been looking at ESG standards and corporate financial success since the 1970s (

Friede et al., 2015). Having reviewed more than 2200 papers, the authors conclude that the research validates the rationale for investing in ESG and that about 90% of studies indicate a positive relationship between ESG and financial performance (

Friede et al., 2015).

A meta-analysis of 132 papers published in reputable journals reveals that 78% of them showed a positive correlation between sustainability and financial performance (

Alshehhi et al., 2018). In particular, by examining the interaction between ESG and diversification,

De la Fuente et al. (

2025) show that ESG can moderate the so-called ‘diversification discount,’ thereby providing measurable value creation effects that go beyond traditional financial indicators.

ESG increases firm value (Tobin’s Q) and profitability (Return on Assets-ROA) as shown by

Velte (

2017). The author also finds that governance affects financial performance in a significant way.

A study by

Yoon et al. (

2018) examined the correlation between ESG ratings and Korean market value. It has been shown that CSR initiatives have a positive and considerable effect on a firm’s market value, though its impact may vary based on its characteristics. In order to examine the relationship between ESG performance and energy market financial indicators,

Zhao et al. (

2018) review Chinese energy listed companies. They find that higher ESG performance increases financial performance. The ESG score affects financial success positively (

Dalal & Thaker, 2019), who examined 65 Indian enterprises from 2015 to 2017.

According to

Fatemi et al. (

2018), strong ESG activities and reporting contribute to firm value in US companies from 2006 to 2011. Based on their findings, reporting moderates valuation by reducing the impact of deficiencies and amplifying strengthening. ESG scores are also positively correlated with firm financial performance in some multi-country studies. A large sample of world-wide firms is examined by

Xie et al. (

2019).

They find a positive correlation between ESG initiatives and financial performance. From 2014 to 2018, Bhaskaranet al. (2020) assessed the impact of ESG on financial performance of 4887 firms using firm value (Tobin’s Q) and operational performance (ROE and ROA). Market value is increased by firms with high environmental, governance, and social performance.

Similarly,

De Lucia et al. (

2020) investigate a sample of 1038 public companies from 22 European countries from 2018 to 2019 and find a positive correlation between the ESG variables and the financial performance (ROE and ROA).

According to

Naeem et al. (

2022), financial performance is influenced by ESG performance in 1042 emerging companies from 2010 to 2019. Combined ESG scores and individual ESG scores positively and significantly affect firm value and profitability (Tobin’s Q). The study by

Chairani and Siregar (

2021) examines listed companies in Asia (Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand) between 2014 and 2018. A positive relationship exists between enterprise risk management (ERM) and firm value and profitability based on the findings that ESG increases the impact of ERM on firm value.

Recent large sample evidence also indicates that superior ESG performance translates into measurable financial benefits in debt markets.

Fiorillo et al. (

2025) show that high-ESG-rated issuers consistently face lower yield spreads (approximately 10 basis points less) in the corporate bond market, particularly due to environmental and social dimensions. This highlights that ESG activities create additional shareholder value not only through equity performance but also by reducing financing costs, thus offering a quantifiable and transparent channel for ESG-driven value creation.

Y. Li et al. (

2018) study 367 FTSE-listed companies between 2004 and 2013 to determine whether ESG reporting enhances firm value. The researchers find a strong correlation between stakeholder trust and accountability and firm value, indicating that the level of ESG reporting affects firm value positively.

Moreover,

Ahmad et al. (

2021) examine the effects of ESG on financial performance of 350 FTSE companies for the period 2002–2018 and find that overall ESG scores significantly and positively impact financial performance of companies, whereas individual ESG performances have mixed results. Sector-specific studies are also available.

Abdi et al. (

2021) examined the effect of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) information on firm value and profitability using 38 airlines between 2009 and 2019. As a result of investing in governance, companies increase their market-to-book ratio, and they become more efficient financially when they are involved in social and environmental matters.

In a study published in 2020, WoeiChyuan Wong analyzed the impact of environ-mental, social, and governance (ESG) certification on Malaysian companies. As a result of ESG certification, a firm’s cost of capital is reduced, while Tobin’s Q increases significantly. It is clear from these findings that corporate social responsibility disclosure by emerging and developing nations enhances value, while these findings are consistent with those in developed economies. Upon receiving an ESG rating, a company’s cost of capital reduces by 1.2%, and Tobin’s Q increases by 31.9%. These findings demonstrate how SRI and ESG agendas benefit stakeholders.

A recent meta-analysis by

Whelan et al. (

2021) from Rockefeller Asset Management and NYU Stern Center for Sustainable Business examined more than 1000 articles focusing on the link between ESG and financial performance published between 2015 and 2020.

There was a positive correlation between ESG and financial performance in the majority (58%) of the papers analyzed. Based on a large dataset of 1720 companies,

Aydoğmuş et al. (

2022), examined the impact of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) performance on firm value and profitability. A total of 14,043 firm-year observations are included in the final panel data. A coefficient of 0.008 and 0.049, respectively, showed a positive and highly significant association between ESG performance and firm value and profitability. As a result of this study, corporate managers will be able to justify mobilizing additional resources towards ESG initiatives.

Companies that invest in ESG incur additional costs, thereby reducing their profitability and market value. A classical profit-maximizing theory is violated by a reallocation of resources from a company’s investors to its stakeholders, which does not generate a positive future return to shareholders (

Artiach et al., 2010). This argument is generally credited to the ‘doing-good-but-not-well’ hypothesis, cost-concern scholars, and neoclassical economists (

Statman, 2009) and (

Waddock & Graves, 1997).

Some scholars argue that ESG investment has a negative impact on profitability or firm value. According to

Barnett (

2007), it is reasonable to predict investing in CSR will have negative impact on firm financial performance due to reallocation of funds to other stakeholders from shareholders.

Building on this strand of inconclusive evidence,

Candio (

2024) conducted a quantitative re-examination of the ESG–financial performance nexus across STOXX Europe 600 firms over a decade. The findings reveal considerable heterogeneity: while the environmental dimension was sometimes positively associated with market-based indicators such as share prices, it showed negative correlations with accounting measures like ROA. Additionally, the tendency towards corporate social responsibility, characterized by factors like board committees and external auditors, has had only a minor moderating effect on these relationships. These findings suggest that the observed relationships can vary greatly based on the methods used, the institutional environments, and the performance standards applied, which explains the apparent contradictions in earlier research.

We observe a number of country-based studies supporting negative relationship between ESG performance and firm value.

Brammer et al. (

2006) analyzes impact of corporate social performance of firms in UK using market returns and find that low social score firms perform better than the market.

Lundgren and Olsson (

2009) focus on bad news in the form of environmental incidents. In an international sample, the authors find that environmental incidents are generally associated with the loss of company value. For European companies, the loss is statistically significant, and the magnitude of the abnormal returns is of economic significance to both companies and investors. Earlier environmental event studies find a significant negative effect of pollution news released by the US EPA on stock prices (

Hamilton, 1995) and (

Khanna et al., 1998). The drop in stock price may indicate the direct future costs to improve environmental performance.

Semenova and Hassel (

2013) examine the asymmetry in the value relevance of environmental performance information, which is driven by company size and the environmental risk of the industry. The authors state that when large companies in regulated, high-risk industries push their environmental performance beyond average compliance, environmental management becomes costly, and the capital markets interpret such in-vestments as overinvestment with a potential to destroy short-term shareholder value. In low-risk industries, there is more room for voluntary environmental improvements at a lower cost. Market premium is positive and stronger for large companies in industries with low environmental risk than for large companies in medium-risk industries. A strong, negative relation between market value and environmental performance is shown for large companies in high-risk industries with tight environmental policies. The environmental performance of small companies is not value relevant for investors. The results of the study are supported by the fact that financial analysts follow more closely large than small companies and also companies in high-risk industries.

Landi and Sciarelli in 2019 focused on 54 listed Italian companies from 2007 to 2015 and report a negative relationship between their ESG scores and financial performance.

Folger-Laronde et al. (

2020) analyzes the link between ESG ratings and financial returns of ETFs (Exchange Traded Funds) during COVID-19 in Canada. They conclude that high ESG performance in ETFs does not ensure protection during severe downturn of the market.

Nollet et al. (

2016), used accounting and market metrics to investigate the connection between social and financial performance of S&P 500 companies from 2007 to 2011. They found evidence of negative relationships on linear models and positive relationship on non-linear models.

Marsat and Williams (

2011) report negative relationship between CSR rating and firm value using worldwide MSCI ESG ratings.

There are a few multi-country studies reporting negative relationships as well.

Duque-Grisales and Aguilera-Caracuel (

2021) examine 104 multinational firms in Latin America from 2011 to 2015. Their findings indicate negative relationship between ESG scores and financial performance of these firms.

Garcia and Orsato (

2020) compares emerging and developed countries through 2165 firms from 2007 to 2014. They reveal that in emerging markets the relationship between ESG scores and financial performance is negative. More recently,

Rojo-Suárez and Alonso-Conde (

2023) show that ESG policies implemented by eurozone firms have limited short-term effects but often reduce long-term value creation. This occurs mainly through higher discount rates, supporting the argument that ESG can introduce substitution effects that outweigh potential value gains over time.

According to a third group of researchers, ESG performance and financial return were mixed.

Han et al. (

2016) found no relationship between social and governance scores for Korean stock companies from 2008 to 2014, while there was a positive relationship between environmental and governance scores.

Using ESG scores,

Atan et al. (

2018) examined how company profitability, firm value, and cost of capital are affected by ESG scores. In terms of firm value or profitability, they find no evidence of a relationship. Using data from 2007 to 2017 from Turkish listed companies,

Saygili et al. (

2022) examine the effect of ESG performance on financial performance. According to their findings, environmental reporting negatively affects firm financial performance, stakeholder participation positively affects social dimension, and governance positively affects financial performance. ESG scores were examined by

Giannopoulos et al. (

2022) for Norwegian listed companies from 2010 to 2019. According to the results, ESG scores are positively correlated with firm value (Tobin’s Q) but negatively correlated with profitability (ROA). According to

Behl et al. (

2022), there is a mixed relationship between ESG reporting and the value of Indian energy sector firms. Using a multi-country study,

Lopez-de-Silanes et al. (

2019) find that ESG scores do not influence firm financial performance.

However, discrepancies in ESG performance relationships often stem from contextual and methodological differences.

Martiny et al. (

2024), through a comprehensive systematic review, highlights that much of the variation in findings can be traced to differences in industry contexts, country level regulations, and even the ESG rating agency employed. Their evidence suggests that without considering these determinants, results may appear inconsistent across studies, which underlines the importance of applying a critical analytical lens when interpreting ESG outcomes.

Nevertheless, the persistence of mixed evidence across industries, geographies, and methodologies has prompted scholars to search for integrative explanations. The recent work of

Cardillo and Basso (

2025) provides a valuable meta-synthesis, highlighting that the contradictory findings in ESG performance research can often be traced to contextual factors. Their study emphasizes that industry environmental risk, corporate governance quality, and regional regulatory maturity act as key moderators of the ESG financial performance relationship.

For example, ESG tends to generate stronger financial benefits in high-risk industries where stakeholder scrutiny is intense, and in regions with well-developed governance systems and reporting frameworks. By contrast, in low-risk industries or less mature regulatory contexts, the link may appear weaker or inconsistent. This perspective reinforces the need for a more nuanced understanding of ESG, suggesting that the value created depends not only on the practices themselves but also on the institutional and sectoral environments in which firms operate. Such insights directly support the objectives of this review, particularly in exploring how internal audit can help organizations interpret ESG outcomes and ensure that value creation claims are grounded in robust governance and resilience strategies.

Table 2 summarizes how the relationship between ESG and financial performance varies and how it is influenced by factors such as industry, location, research methods, time span, and governance standards. The framework indicates that instead of seeing the existing literature as conflicting, it should be regarded as dependent on different contextual factors. Discrepancies often stem from sector-specific risk profiles, institutional settings, and the type of performance metrics employed. The table distills these insights by linking observed ESG financial outcomes to their underlying drivers, supported by the studies reviewed, in the section.