Financing Constraints and High-Quality Development of Chinese Listed Firms: Mechanisms of Investment Efficiency and Contingent Factors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Financing Constraints and High-Quality Development

2.2. Financing Constraints and Investment Efficiency

2.3. Financial Constraints, Investment Efficiency and Firms’ High-Quality Development

2.4. Brief Review

3. Mechanism Analysis, Hypotheses and Research Design

3.1. Mechanism Analysis and Hypotheses

3.1.1. Financing Constraints, Investment Efficiency, and High-Quality Development

3.1.2. Moderating Role of Managerial Effectiveness

3.2. Research Design

3.2.1. Variable Selection

3.2.2. Model Specification

4. Empirical Analysis

4.1. Data Sources and Processing

- (1)

- Exclusion of ST and *ST Companies: These companies, facing the threat of delisting, are likely to have abnormal financial data, which could affect the empirical results.

- (2)

- Exclusion of Financial Firms: Financial institutions have unique business models and financing channels compared to other industries, making them unsuitable for this analysis.

- (3)

- Exclusion of Incomplete Data Samples: Samples with discontinuous data or missing values are excluded to ensure data integrity.

4.2. Descriptive Statistics

4.3. Correlation Analysis

4.4. Benchmark Regression

4.5. Endogeneity Test

4.6. Robustness

5. Analysis of Mediating and Moderating Effects

5.1. Heterogeneity Test

5.2. Mediating Effects

5.3. Moderating Effect

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Recommendations

6.3. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anagnostopoulou, S. C., & Malikov, K. T. (2024). The real consequences of classification shifting: Evidence from the efficiency of corporate investment. European Accounting Review, 33(4), 1549–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, D., & Meza, F. (2009). Total factor productivity and labor reallocation: The case of the Korean 1997 crisis. The BE Journal of Macroeconomics, 9(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cai, F., & Lu, Y. (2016). Take-off, persistence and sustainability: The demographic factor in Chinese growth. Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies, 3(2), 203–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y., & Cao, G. (2025). Institutional openness and firm’s green innovation: Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment in China. Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-C., & Tang, H.-W. (2021). Corporate cash holdings and total factor productivity—A global analysis. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance, 55, 101316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Yang, S., & Li, Q. (2022). How does the development of digital financial inclusion affect the total factor productivity of listed companies? Evidence from China. Finance Research Letters, 47, 102956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, P. K., & Nagaraj, P. (2014). Productivity and firm size in India. Small Business Economics, 42(4), 891–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerjian, P., Lev, B., & McVay, S. (2012). Quantifying managerial ability: A new measure and validity tests. Management Science, 58(7), 1229–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhawan, R. (2001). Firm size and productivity differential: Theory and evidence from a panel of US firms. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 44(3), 269–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Y., & Zhao, J. (2024). The impact of supply chain finance on the investment efficiency of publicly listed companies in China based on sustainable development. Sustainability, 16(18), 8234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farre-Mensa, J., & Ljungqvist, A. (2016). Do measures of financial constraints measure financial constraints? The Review of Financial Studies, 29(2), 271–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glawe, L., & Wagner, H. (2020). China in the middle-income trap? China Economic Review, 60, 101264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.-T., & Klenow, P. J. (2009). Misallocation and manufacturing TFP in China and India. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124(4), 1403–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. N., & Zingales, L. (1997). Do investment-cash flow sensitivities provide useful measures of financing constraints? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(1), 169–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. (2022). Analysis on the relationship between financing constraints and research and development from the perspective of the location of top management network. Discrete Dynamics in Nature and Society, 2022(1), 8690801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Wei, R., & Guo, Y. (2022). How can the financing constraints of smes be eased in China?—Effect analysis, heterogeneity test and mechanism identification based on digital inclusive finance. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 10, 949164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y., & Zhang, C. (2024). Digital transformation and total factor productivity of enterprises: Evidence from China. Economic Change and Restructuring, 57(1), 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J. (2019). Be creative for the state: Creative workers in Chinese state-owned cultural enterprises. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 22(1), 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-L., & Lin, Y.-M. (2018). Do mispricing and financial constraints matter for investment decisions? Applied Economics, 50(54), 5877–5892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maietta, O. W., & Sena, V. (2010). Financial constraints and technical efficiency: Some empirical evidence for Italian producers’ cooperatives. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 81(1), 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollisi, V., & Rovigatti, G. (2017). Theory and practice of TFP estimation: The control function approach using Stata (CEIS Research Paper 399). Tor Vergata University, CEIS. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/rtv/ceisrp/399.html (accessed on 17 November 2024).

- Murphree, M., & Breznitz, D. (2025). China, global value chains, and the middle-income trap. Business and Politics, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S. C., & Majluf, N. S. (1984). Corporate financing and investment decisions when firms have information that investors do not have. Journal of Financial Economics, 13(2), 187–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panousi, V., & Papanikolaou, D. (2012). Investment, idiosyncratic risk, and ownership. The Journal of Finance, 67(3), 1113–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X. (2014). Uncertainty, equity incentives, and inefficient investment. Accounting Research, 3, 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Quan, Y., Yu, X., & Xu, W. (2021). The Yangtze River Delta integration and regional development of marine economy: Conference report. Marine Policy, 127, 104420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, S. (2006). Over-investment of free cash flow. Review of Accounting Studies, 11(2), 159–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.-C. (2017). Total factor productivity or labor productivity? Firm heterogeneity and location choice of multinationals. International Review of Economics & Finance, 49, 499–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaban, S., & Shavit, T. (2024). The agency Problem of the modern era—The conflict between shareholders’ and managers’ motives to invest in happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 25(7), 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uras, B. R. (2014). Corporate financial structure, misallocation and total factor productivity. Journal of Banking & Finance, 39, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C., Liu, F., & Wang, Y. (2023). Emergy-based comparative analysis of an ecological economy in the Yangtze River Delta. Environmental Engineering Research, 28(1), 210325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Wang, M., & Wu, H. (2024). Geopolitical risk and corporate cash Holdings in China: Precautionary motive and agency problem perspectives. International Review of Financial Analysis, 93, 103235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Chen, C. R., & Huang, Y. S. (2014). Economic policy uncertainty and corporate investment: Evidence from China. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 26, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., & Kong, Q. (2019). Financial constraints, institutions, and firm productivity: Evidence from China. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 55(11), 2652–2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, J. M. (2009). On estimating firm-level production functions using proxy variables to control for unobservables. Economics Letters, 104(3), 112–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B., Zhang, Y., Shen, Y., & Han, J. (2018). Productivity, financial constraints and outward foreign direct investment: Firm-level evidence. China Economic Review, 47, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J., & Zhao, Z. (2025). Study on impact of managerial effectiveness and digitalization on green total factor productivity of enterprises: Sample of listed heavy-polluting enterprises in China. Sustainability, 17(15), 6700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L., & Zhou, Q. (2021). Leverage constraints and corporate financing decisions. Accounting & Finance, 61(4), 5199–5230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z., Zhao, Z., Shao, S., & Yang, L. (2023). Carbon regulation and enterprise investment: Evidence from China. Energy Economics, 128, 107160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K., Zhang, X., Xiong, L., & Rao, B. (2024). The stabilizing effect of government guarantees in real economy investment: Evidence from China. International Review of Economics & Finance, 91, 219–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Name | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| WRDG | Total Factor Productivity (TFP) | Calculated through Wooldridge’s method |

| MrEst | Calculated through Blundell’s method | |

| KZ | Financing Constraints | Calculated through Hadlock’s method |

| ME | Managerial Effectiveness | Measured through the DE-Tobit method by Demerjian |

| ABSINV | Degree of Inefficient Investment | Degree of inefficient investment measured using Richardson’s method |

| ZScore | Financial Distress | Calculated using Edward’s method |

| growth | Revenue Growth Rate | (Current period’s total operating revenue—Last year’s total operating revenue)/Last year’s total operating revenue |

| cash | Cash Flow | Net operating cash flow/Total assets |

| stock | Equity Concentration | ln(Shareholding proportion of the controlling shareholder) |

| indro | Proportion of Independent Directors | Number of independent directors/Total number of board members |

| dual | Duality of CEO and Chairman | Dummy variable for whether the chairman and CEO are the same person (1 if yes, 0 if no) |

| organ | Institutional Ownership Ratio | Proportion of shares held by institutional Investors in the listed company (%) |

| age | Firm Age | Years since the firm’s establishment |

| Variable | N | SD | Mean | Min | p50 | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WRDG | 35,404 | 0.6143768 | 3.042223 | 1.239892 | 3.032217 | 4.8106 |

| MrEst | 35,404 | 0.6105293 | 2.525631 | 0.7288052 | 2.518295 | 4.278914 |

| KZ | 35,404 | 2.447005 | 1.387525 | −6.624826 | 1.622986 | 7.54728 |

| ME | 33,715 | 0.2474179 | −0.0158838 | −0.9237927 | 0 | 0.7929062 |

| ABSINV | 28,285 | 0.052932 | 0.043116 | 0.000525 | 0.026629 | 0.328065 |

| ZScore | 35,404 | 5.659845 | 4.728312 | −1.035653 | 2.985295 | 36.49113 |

| growth | 35,404 | 0.4879556 | 0.1818652 | −0.643399 | 0.106404 | 3.317019 |

| stock | 35,404 | 0.4583701 | 3.505749 | 2.128232 | 3.55934 | 4.317355 |

| indro | 35,404 | 0.0533835 | 0.3736158 | 0.3 | 0.3333 | 0.5714 |

| dual | 35,404 | 0.4398782 | 0.2622764 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| age | 35,404 | 7.191605 | 10.25571 | 0.1068493 | 9.321918 | 26.41918 |

| size | 35,404 | 1.311315 | 22.01696 | 19.30672 | 21.8449 | 26.04762 |

| WRDG | KZ | ABSINV | Growth | Stock | Indro | Dual | Age | Size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WRDG | 1 | ||||||||

| KZ | −0.015 *** | 1 | |||||||

| ABSINV | −0.108 *** | −0.046 *** | 1 | ||||||

| growth | 0.144 *** | −0.053 *** | 0.164 *** | 1 | |||||

| stock | 0.105 *** | −0.181 *** | −0.033 *** | 0.032 *** | 1 | ||||

| indro | −0.019 *** | −0.002 | 0.017 *** | −0.003 | 0.034 *** | 1 | |||

| dual | −0.045 *** | −0.138 *** | 0.049 *** | 0.008 | −0.013 ** | 0.107 *** | 1 | ||

| age | 0.013 ** | 0.353 *** | −0.106 *** | −0.045 *** | −0.191 *** | −0.017 *** | −0.230 *** | 1 | |

| size | 0.140 *** | 0.069 *** | −0.120 *** | 0.036 *** | 0.133 *** | 0.016 *** | −0.161 *** | 0.346 *** | 1 |

| Variable | VIF | 1/VIF |

|---|---|---|

| KZ | 1.29 | 0.7734 |

| age | 1.29 | 0.7761 |

| size | 1.17 | 0.8543 |

| dual | 1.09 | 0.9143 |

| stock | 1.09 | 0.9171 |

| indro | 1.01 | 0.9862 |

| growth | 1.00 | 0.9951 |

| Mean VIF | 1.14 |

| Linear Relationship | Non-Linear Relationship | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| WRDG | WRDG | WRDG | WRDG | |

| KZ2 | −0.00341 *** | −0.00337 *** | ||

| [0.0004] | [0.0004] | |||

| KZ | −0.0128 *** | −0.00716 *** | −0.00944 *** | −0.00410 ** |

| [0.0023] | [0.0022] | [0.0020] | [0.0020] | |

| controls | no | yes | no | yes |

| firm | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| year | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| _cons | 3.091 *** | 3.311 *** | 3.123 *** | 3.527 *** |

| [0.0131] | [0.3005] | [0.0142] | [0.2975] | |

| N | 35,404 | 35,404 | 35,404 | 35,404 |

| adj. R2 | 0.0177 | 0.1028 | 0.0238 | 0.1087 |

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |

|---|---|---|

| Interval | −6.624826 | 7.54728 |

| Slope | 0.0357425 | −0.0609133 |

| t-value | 6.381119 | −8.013561 |

| p > t | 9.75 × 10−11 | 7.16 × 10−16 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KZ | WRDG | KZ | KZ2 | WRDG | KZ | KZ2 | WRDG | |

| KZ2 | −0.0406 * | −0.0173 *** | ||||||

| [0.0224] | [0.0054] | |||||||

| KZ | −0.0139 *** | 0.142 * | 0.0493 *** | |||||

| [0.0037] | [0.0744] | [0.0101] | ||||||

| IV1 | 0.292 *** | 0.255 *** | 0.8816 *** | 0.255 *** | −0.2011 *** | |||

| [0.0045] | [0.0059] | [0.0306] | [0.0059] | [0.0340] | ||||

| IV2 | 0.144 *** | 0.3857 *** | 0.144 *** | 0.5085 *** | ||||

| [0.0076] | [0.0390] | [0.0076] | [0.0433] | |||||

| Cragg-Donald Wald F statistic | 3680.685 *** | 17.744 *** | 53.747 *** | |||||

| Cragg-Donald Wald F statistic | 4232.088 | 13.872 | 26.952 | |||||

| Stock-Yogo weak ID test critical values (10%) | 16.38 | 7.03 | 7.03 | |||||

| controls | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| firm | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| year | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| N | 31,737 | 18,266 | 18,266 | |||||

| adj. R-sq | −0.0186 | −0.0306 | 0.1301 | |||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MrEst | MrEst | MrEst | MrEst | WRDG | WRDG | |

| KZ | −0.0119 *** | −0.00468 ** | −0.00863 *** | −0.00129 | ||

| [0.0023] | [0.0023] | [0.0020] | [0.0021] | |||

| KZ2 | −0.00338 *** | −0.00342 *** | ||||

| [0.0004] | [0.0004] | |||||

| KZ_ortho2 | −0.0344 *** | |||||

| [0.0042] | ||||||

| KZ_ortho1 | −0.0134 ** | −0.0165 *** | ||||

| [0.0055] | [0.0056] | |||||

| controls | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| firm | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| year | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| _cons | 2.598 *** | 2.891 *** | 2.629 *** | 3.047 *** | 3.340 *** | 3.468 *** |

| [0.0132] | [0.2101] | [0.0143] | [0.2102] | [0.2108] | [0.2108] | |

| N | 35,389 | 35,389 | 35,389 | 35,389 | 35,389 | 35,389 |

| adj. R-sq | 0.02 | 0.1054 | 0.026 | 0.1114 | 0.1059 | 0.1122 |

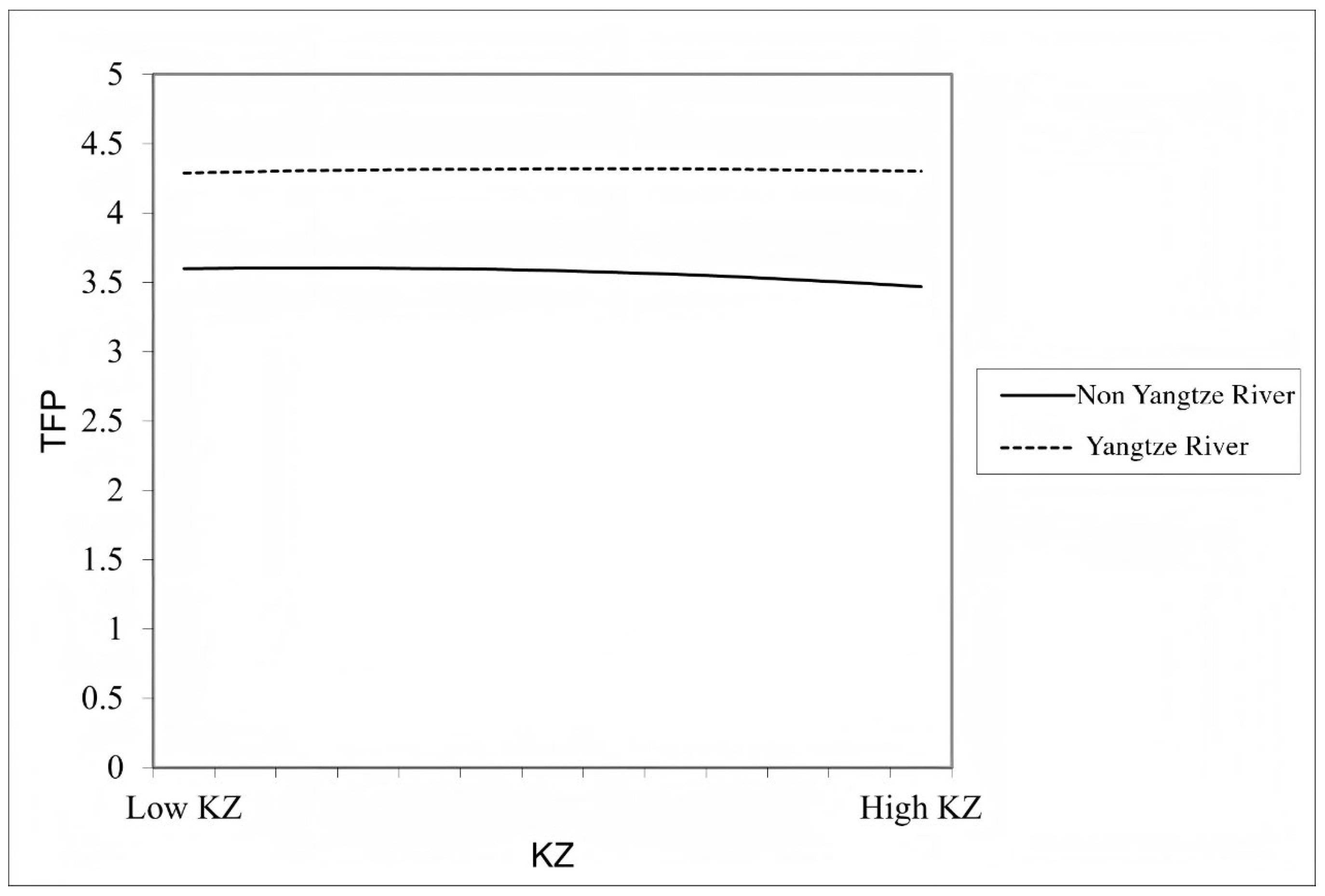

| Non Yangtze River Delta | Yangtze River Delta | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| WRDG | WRDG | WRDG | WRDG | |

| KZ2 | −0.00374 *** | −0.00171 ** | ||

| [0.0005] | [0.0007] | |||

| KZ | −0.0109 *** | −0.00707 *** | 0.00553 | 0.00624 * |

| [0.0026] | [0.0024] | [0.0036] | [0.0035] | |

| controls | no | yes | no | yes |

| firm | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| year | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| _cons | 3.348 *** | 3.601 *** | 4.244 *** | 4.313 *** |

| [0.3554] | [0.3506] | [0.5286] | [0.5331] | |

| N | 25,703 | 25,703 | 9701 | 9701 |

| adj. R2 | 0.1052 | 0.1122 | 0.1211 | 0.1226 |

| Linear Relationship | Non-Linear Relationship | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| WRDG | ABSINV | WRDG | WRDG | ABSINV | WRDG | |

| ABSINV | −0.666 *** | −0.655 *** | ||||

| [0.0578] | [0.0575] | |||||

| KZ2 | −0.00337 *** | 0.000285 *** | −0.00249 *** | |||

| [0.0004] | [0.0001] | [0.0006] | ||||

| KZ | −0.00716 *** | −0.00185 *** | −0.0118 *** | −0.00410 ** | −0.00247 *** | −0.00630 ** |

| [0.0022] | [0.0003] | [0.0028] | [0.0020] | [0.0004] | [0.0028] | |

| controls | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| firm | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| year | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| _cons | 3.311 *** | 0.0334 | 3.772 *** | 3.527 *** | 0.0276 | 3.822 *** |

| [0.3005] | [0.0251] | [0.3445] | [0.2975] | [0.0251] | [0.3441] | |

| N | 35404 | 28285 | 28285 | 35404 | 28285 | 28285 |

| adj. R2 | 0.1028 | 0.0699 | 0.1253 | 0.1087 | 0.071 | 0.1272 |

| Linear Relationship | Non-Linear Relationship | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| WRDG | WRDG | WRDG | WRDG | |

| BC∗KZ2 | 0.00293 ** | |||

| [0.0012] | ||||

| ME∗KZ2 | 0.00615 *** | |||

| [0.0015] | ||||

| BC∗KZ | 0.0188 *** | 0.00203 | ||

| [0.0051] | [0.0042] | |||

| ME∗KZ | 0.0402 *** | 0.0124 ** | ||

| [0.0070] | [0.0063] | |||

| KZ2 | −0.00343 *** | −0.00574 *** | ||

| [0.0005] | [0.0011] | |||

| KZ | −0.00958 *** | −0.0228 *** | −0.00105 | −0.00421 |

| [0.0026] | [0.0052] | [0.0025] | [0.0044] | |

| BC | −0.0199 | −0.0164 | ||

| [0.0133] | [0.0143] | |||

| ME | 0.118 *** | 0.113 *** | ||

| [0.0156] | [0.0163] | |||

| controls | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| firm | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| year | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| _cons | 3.444 *** | 3.513 *** | 3.634 *** | 3.707 *** |

| [0.3259] | [0.3082] | [0.3228] | [0.3065] | |

| N | 33,164 | 33,164 | 33,164 | 33,164 |

| adj. R2 | 0.1252 | 0.1049 | 0.1312 | 0.1106 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yan, J.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, Y. Financing Constraints and High-Quality Development of Chinese Listed Firms: Mechanisms of Investment Efficiency and Contingent Factors. Int. J. Financial Stud. 2025, 13, 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs13030179

Yan J, Zhao Z, Liu Y. Financing Constraints and High-Quality Development of Chinese Listed Firms: Mechanisms of Investment Efficiency and Contingent Factors. International Journal of Financial Studies. 2025; 13(3):179. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs13030179

Chicago/Turabian StyleYan, Jun, Zexia Zhao, and Yan Liu. 2025. "Financing Constraints and High-Quality Development of Chinese Listed Firms: Mechanisms of Investment Efficiency and Contingent Factors" International Journal of Financial Studies 13, no. 3: 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs13030179

APA StyleYan, J., Zhao, Z., & Liu, Y. (2025). Financing Constraints and High-Quality Development of Chinese Listed Firms: Mechanisms of Investment Efficiency and Contingent Factors. International Journal of Financial Studies, 13(3), 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs13030179