Abstract

Financial literacy is a key competence for responsible decision-making and entrepreneurial readiness. This study looks at how Generation Z’s entrepreneurial participation is impacted by objective, subjective, and calibrated FL. The alignment of perceived and actual knowledge or calibration is highlighted as an understudied factor that influences entrepreneurial behaviour. A mixed-methods approach was applied, combining a survey of 403 Slovak students with structured interviews with secondary school and university teachers. Quantitative analysis used Chi-square tests, Cramer’s V, sign schemes, and MLR. Qualitative interviews provided contextual insights into educational gaps and perceived barriers to entrepreneurship. The findings confirm that a higher financial literacy is positively related to entrepreneurial interest. Objective literacy has a slightly greater predictive value than self-assessed literacy, while calibration emerged as the strongest predictor: realistically, financially literate individuals displayed the highest entrepreneurial engagement, whereas both over- and underestimation of financial knowledge reduced it. Interviews highlighted insufficient financial education, limited practical experience, and fear of risk as major obstacles. By combining three aspects of financial literacy with business goals and offering fresh data from Slovakia, this study makes a contribution to the literature. In similar situations, it makes suggestions for enhancing financial education to support Generation Z’s entrepreneurial potential.

1. Introduction

A key indicator of a person’s capacity to make wise financial decisions is their level of financial literacy. Financial literacy includes practical skills, confidence, and competence in using financial instruments and services, as well as in making financial decisions, in addition to knowledge and comprehension of financial ideas and hazards (Mustafa et al., 2025).

These skills can be divided into four dimensions of so-called digital literacy (Youngjoo et al., 2023). It has been demonstrated that more financial literacy benefits society’s general socio-economic development in addition to people’s personal financial well-being (Bansal & Kaur, 2024; Hong Shan et al., 2023). In addition, it influences the attitude towards financial risk, and thus, the way individuals make economic decisions (Chen et al., 2023).

At the same time, it appears that one’s level of financial literacy is influenced by a range of socio-economic and demographic factors, with demonstrable differences also being observed between genders. Several studies also point out that Generation Z (people born approximately between 1997 and 2012) achieves a lower-than-expected level of financial literacy (Hong Shan et al., 2023), which may have negative consequences for their ability to effectively manage finances and make strategic decisions, for example, in connection with entrepreneurship.

In the context of a dynamically changing economic environment, the development of digital financial instruments and the growing need for independent economic application, we consider the study of young people’s financial literacy and its relationship to entrepreneurial interest to be extremely relevant. Financial literacy is increasingly associated not only with quality of life but also with entrepreneurial competencies, which are currently key to the development of a creative and innovative business environment. The aim of the paper is to examine the connections between various aspects of financial literacy, including its subjective perception, objectively verified level and ability of realistic self-assessment (calibration), and entrepreneurial ambitions of young people from Generation Z. The paper seeks to identify to what extent these dimensions of financial literacy influence the decision to enter entrepreneurship and what role they play as motivational or inhibitory factors in the process of forming entrepreneurial interest. At the same time, the research seeks to contribute to a better understanding of how the entrepreneurial potential of young people can be supported in a changing economic and technological environment through the targeted development of financial competencies. The focus of our study is also supported by the results of the overlay visualisation shown in Figure 1. We decided to create an overlay visualisation of the issue focused on the area of financial literacy and entrepreneurial intention.

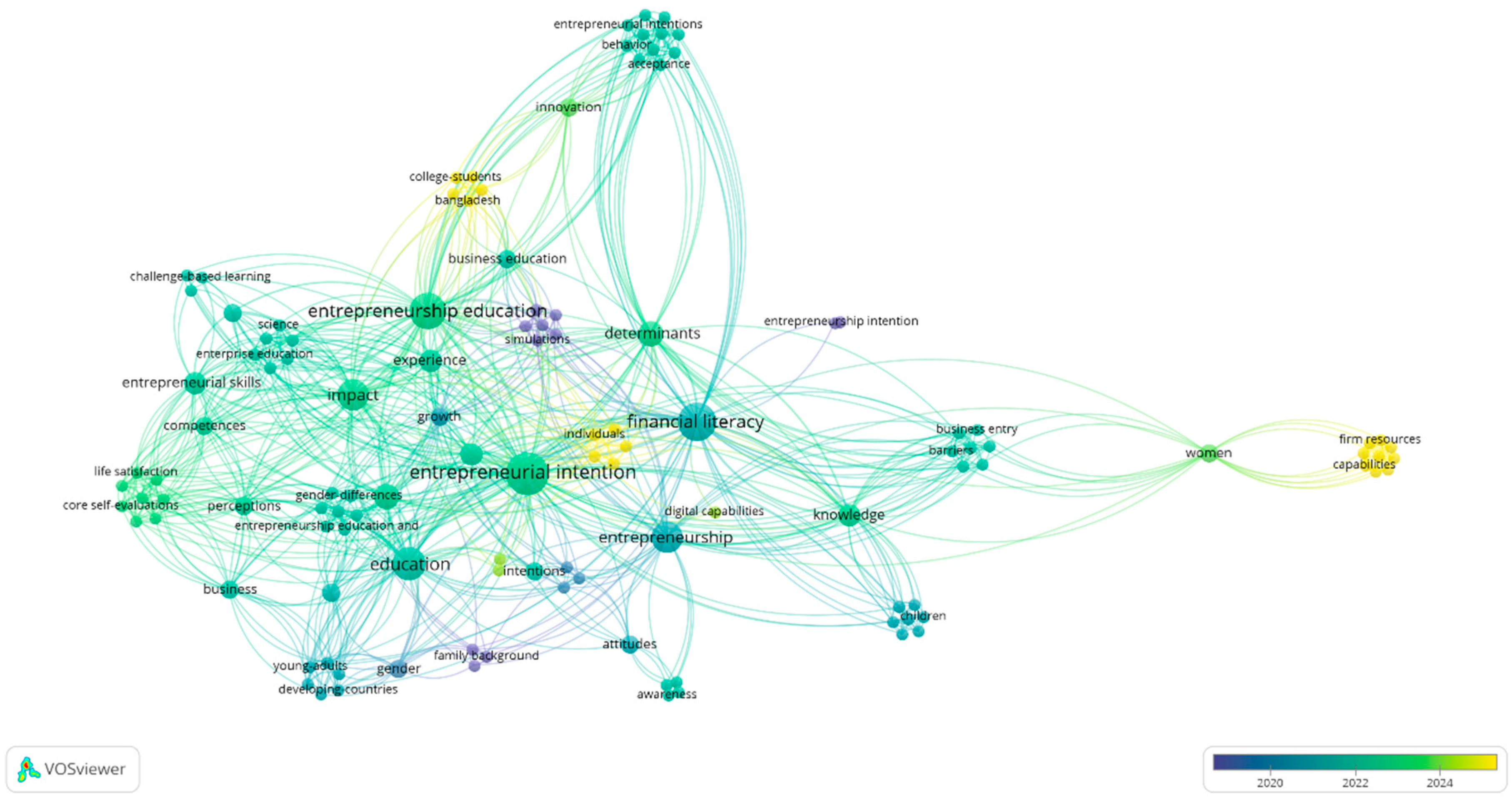

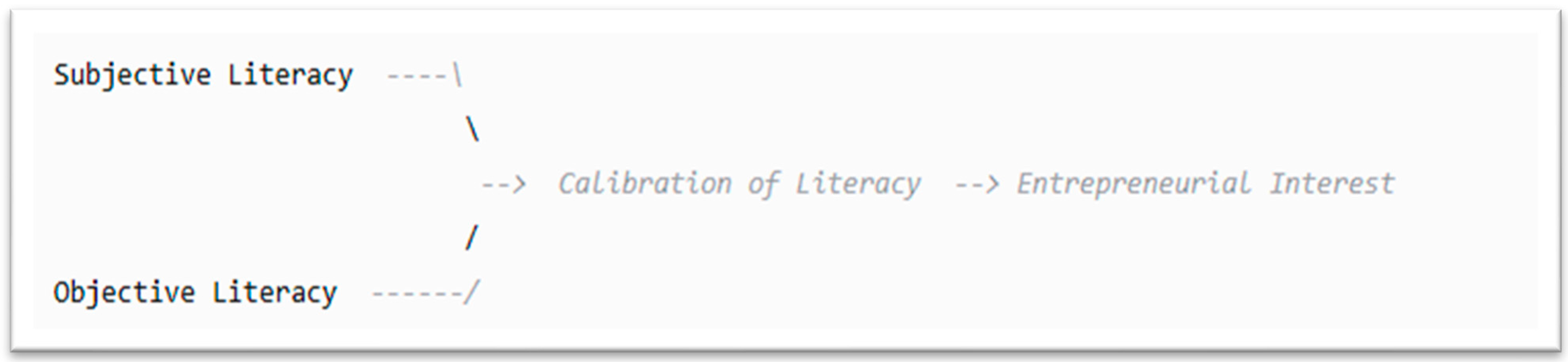

Figure 1.

Overlay visualisation of FL and EI. Source: Own processing (2025).

Although this work primarily examines entrepreneurial interest, not entrepreneurial intention, several studies confirm that financial literacy plays an important role in the early stages of entrepreneurial thinking (Romadhon & Mulyadi, 2025; Guo et al., 2024; Kang et al., 2024; Xu & Jiang, 2024; R. Li & Qian, 2020). It is therefore justified to include studies on “entrepreneurial intention” as a theoretical framework for examining the relationship between financial literacy and entrepreneurial interest. Using the WoS database, 18 articles were identified based on the keywords “financial literacy” and “entrepreneurial intention,” covering the period from 2018 to the present. The topics can be categorised into three areas: declining (blue), stable core (teal), and emerging (yellow–green).

The topics on decline, addressed until 2020, defined basic concepts such as FL and its possible impacts on entrepreneurship, or defined early behavioural models were addressed. These areas form the inseparable foundations of the issue, but research has gradually moved to the area of entrepreneurial behaviour. In the stable core (teal clusters), they represent the creation of a strong connection between the triangle of concepts: entrepreneurial intention, FL (financial literacy), and entrepreneurship education. In the period from 2021 to 2023, the authors were primarily interested in the impact of FI on EI and, at the same time, the impact of entrepreneurship education on the aforementioned factors. The most current issues discussed include gender-specific entrepreneurship, behavioural determinants, and geographical–contextual studies. In simple terms, current research focuses on the analysis of specific resources and abilities of female entrepreneurs, behavioural mechanisms as an intermediate stage between FI and EI, or the attempt to generalise models outside the Western context. Ultimately, research in the area under study has moved from basic concepts through connections to entrepreneurship education to gender, regional, or behavioural specifications.

Research on the relationship between financial literacy (FL) and entrepreneurship has undergone a notable evolution over the past two decades. Early studies, dominant until 2020, were primarily concerned with defining basic concepts—such as FL and its potential impacts on entrepreneurial activity—or with constructing initial behavioural models. These works established essential foundations but offered only a limited understanding of how FL translates into entrepreneurial behaviour.

Subsequent research has progressively moved towards more applied perspectives, emphasising entrepreneurial intentions (EI) and their linkages with both FL and entrepreneurship education. Between 2021 and 2023, a considerable body of research examined how financial literacy influences entrepreneurial intentions and how entrepreneurship education mediates these effects. Emerging themes have since included gender-specific entrepreneurship, behavioural determinants, and cross-cultural analyses, with scholars increasingly focusing on mechanisms such as self-confidence, decision-making biases, or the influence of socio-cultural context.

Despite these advances, several critical gaps remain insufficiently addressed. First, most existing studies conceptualise financial literacy either as an objective measure of knowledge or as a set of technical skills, while underestimating the importance of subjective self-assessment and calibration between perceived and actual competence. This neglects the psychological dimension of FL and its behavioural consequences, particularly in the context of entrepreneurship. Second, although the relationship between FL and EI is now well-established, the mediating mechanisms remain underexplored. In particular, little is known about how the alignment—or misalignment—between subjective and objective literacy shapes entrepreneurial interest and decision-making. Third, current research is largely dominated by Western or global datasets, while Central and Eastern Europe remains underrepresented despite the specific structural, cultural, and educational conditions that influence the youth’s entrepreneurial behaviour in this region.

The aim of this study is to determine to what extent financial knowledge, the ability to realistically self-assess, and the overall attitude towards finances influence the decision to engage in entrepreneurship. The uniqueness of this work lies precisely in this combination of factors. The analyses conducted in Slovakia yield results that are significant not only in the national context but, due to structural and cultural similarities, are also highly relevant for the V4 countries. Slovakia, as a small open economy, can serve as a model case for other EU member states as well as for candidate countries, as it highlights the factors shaping the entrepreneurial behaviour of the young generation.

This research, therefore, addresses a critical gap in the literature on the link between financial literacy and entrepreneurial potential, while at the same time providing findings with direct implications for the development of educational programmes and policies that foster sustainable development. Methodologically, this study responds to the identified gaps by combining three dimensions of financial literacy—objective knowledge, subjective self-assessment, and calibration—to examine their joint impact on entrepreneurial interest among Generation Z students in Slovakia. By integrating cognitive, metacognitive, and attitudinal aspects of FL, the analysis moves beyond traditional conceptualizations and highlights the role of the Dunning–Kruger effect as a key explanatory mechanism in youth decision-making.

The mixed-methods design, which combines survey data from 403 students with qualitative interviews with teachers, provides both breadth and depth of insight. This dual perspective makes it possible not only to identify statistical relationships but also to contextualise them within the realities of the educational system.

The contribution of this work is threefold. Theoretically, it offers an expanded conceptualization of FL as a multi-dimensional construct linked to critical thinking, metacognition, and entrepreneurial aspirations, thereby enriching academic debates on the intersection between financial competence and entrepreneurship. Empirically, it provides novel evidence from Slovakia, a small open economy whose structural and cultural features render it representative for Visegrad countries and comparable EU or candidate states. Practically, it proposes a replicable educational module—Financial Literacy with Elements of Entrepreneurship—that combines traditional instruction with digital tools, gamification, and AI-driven feedback to foster both financial competence and entrepreneurial readiness.

Ultimately, this study advances knowledge by demonstrating that calibrated financial literacy, rather than knowledge alone, is a significant predictor of entrepreneurial interest. In doing so, it not only addresses an underexplored dimension of the FL–EI nexus but also provides a systematic framework for educational interventions that can be adapted across national contexts.

2. Theoretical Framework

Although there are several definitions of financial literacy, generally speaking, it can be defined as the capacity to apply financial information to make wise financial decisions and mould appropriate financial behaviour (Hong Shan et al., 2023). Its main goal is to achieve financial stability and overall well-being (Ho & Lee, 2020). The level of financial literacy significantly affects the quality and effectiveness of individual financial planning (Rapina et al., 2023).

In today’s world, financial literacy is becoming an integral part of everyday life. It includes the ability to effectively manage finances, understand basic economic indicators, and plan for the financial future (Gignac et al., 2023). Digital financial literacy, which is crucial for both utilising the advantages of digital financial services and identifying the risks connected to contemporary technology, is becoming more and more important as a result of technological advancement and digitalization (Koskelainen et al., 2023).

Financial literacy plays a fundamental role in many aspects of life. A higher level of these skills is directly related to an individual’s ability to cope with unexpected expenses and income shortfalls (Hasler et al., 2023). People with a higher financial literacy choose different management strategies than those with lower literacy—they have an overview of their income and expenses and can manage them effectively (Gamst-Klaussen et al., 2019). Financial literacy positively affects the quality of life, contributes to reducing unemployment and currency instability, and supports the development of economic culture in society (Sconti, 2024). It also has an impact on purchasing decisions and consumer behaviour (Kadoya et al., 2021).

Several studies also address gender differences in financial literacy. Findings suggest that men tend to have a higher financial literacy than women, who are more cautious, less confident in dealing with financial issues, and have a lower level of knowledge in this area (Gudjonsson et al., 2022).

Generation Z faces several challenges. Many of its members lack the necessary experiences, knowledge, and habits that could contribute to their financial literacy. They are more vulnerable to finances compared to previous generations. Research suggests that this generation is characterised by a lack of basic financial knowledge and an increase in debt (Zhu, 2021). The importance of financial education cannot be underestimated. Without quality financial education, young people are not prepared to make sound financial decisions (Ang et al., 2022; P. Kovács et al., 2021).

Generation Z’s debt is increasing, putting them at risk of financial instability that negatively affects not only their economic situation but also their family and psychological well-being—stress and anxiety are common consequences of poor financial health (Cyfert et al., 2021). Given the rising cost of living and inflation, it is essential to know and understand these factors, as they contribute to financial discomfort (P. Kovács et al., 2021).

In any situation, it is important to make wise financial decisions and manage your funds efficiently. Poor personal financial management, such as excessive borrowing or insufficient planning, can lead to serious financial problems, especially for people with low incomes (Kadoya et al., 2021). Differences in the level of financial literacy are of interest to policymakers and educational institutions, which are trying to develop targeted financial education programmes and thus mitigate existing inequalities in society (Bialowolski et al., 2022).

H1.

Subjective financial literacy has an impact on entrepreneurial interest. There is a statistically significant relationship between whether respondents consider themselves financially literate and their interest in entrepreneurship.

Financial literacy is an important factor influencing an individual’s readiness to enter the entrepreneurial environment. Its importance lies in the fact that it provides individuals with the ability to effectively manage their assets and finances (Ahmad et al., 2019). This type of literacy not only shapes personal financial behaviour but also influences decision-making in entrepreneurial activities (Akca et al., 2018). For a business to be successful and effective, it is essential for an entrepreneur to be able to manage finances rationally and practically, because only in this way is it possible to make the right business decisions (Hasan et al., 2024).

Financial literacy serves as a fulcrum for entrepreneurs, as it provides them with the knowledge and skills necessary for qualified decision-making in various areas of business. The ability to understand financial information, analyse data, and assess risks significantly enhances the ability of entrepreneurs to manage challenges and seize opportunities (Thomas & Subhashree, 2020). Research shows that individuals with higher levels of financial literacy have a greater potential to succeed in business. This literacy supports business performance by facilitating the implementation of strategic decisions and streamlining the budgeting process (Z. Li et al., 2019).

In addition, financial literacy contributes to reducing financial vulnerability, which is also true in the entrepreneurial environment. An entrepreneur who has sufficient financial skills is able to create quality financial plans and make appropriate decisions (Chhatwani & Mishra, 2021; Struckell et al., 2022). Financial literacy provides young entrepreneurs with the opportunity to thoroughly assess risks and identify potential financial threats and uncertainties. Thanks to this knowledge, they can implement risk mitigation strategies, such as insurance instruments, emergency plans, or the diversification of investment portfolios. Such a proactive approach to risk management is based on financial literacy and leads to more resilient and adaptive business strategies (Liu et al., 2020).

H2.

Objective financial literacy has an impact on interest in entrepreneurship. There is a statistically significant relationship between whether respondents are financially literate and their interest in entrepreneurship.

Financially literate entrepreneurs are also able to thoroughly evaluate investment opportunities, which is essential for estimating investment returns, understanding the associated risks, and making decisions in line with the financial goals of the company. The ability to navigate the complexity of investment decision-making is evidence of the impact of financial literacy on business practice. Research on the relationship between financial literacy and decision-making processes of young entrepreneurs shows a close link between knowledge and effective decision-making (Thomas & Subhashree, 2020). Financial literacy thus enables businesses to make informed decisions in all areas—from strategic direction and resource allocation to risk assessment, cash flow management, and investment. The results point to the need to develop financial literacy among young entrepreneurs as a key tool to improve their decision-making competencies (Luo et al., 2021).

Conversely, students with insufficient financial literacy who plan to enter entrepreneurship often lack basic financial management skills, which can pose a serious barrier to their entrepreneurial activities (Hasan et al., 2024). Entrepreneurship and financial education are interconnected areas that significantly affect the entrepreneurial readiness of Generation Z. Research results show that entrepreneurship education has a positive impact not only on the level of professional knowledge and skills of students but also on their overall readiness to enter the entrepreneurial environment and on the intention to start a business. At the same time, it contributes to increasing their financial literacy (Hasan et al., 2024; Rakićević et al., 2022; Rodriguez & Lieber, 2020).

Given the above facts, it can be stated that entrepreneurship education and financial literacy play a key role in developing Generation Z’s financial management skills, increasing their competitiveness and economic security. For this reason, it is necessary to intensify efforts to improve the availability and quality of entrepreneurship and financial education, which creates the conditions for the effective use of their potential (Hasan et al., 2024).

Comparative analyses show that although members of Generation Z prefer stability and have a low tolerance for uncertainty, they are also characterised by a more pronounced entrepreneurial mindset and a higher level of interest in a business environment orientated towards clearly defined goals compared to previous generations. The sustainable development of organisations, as well as the entire society, is therefore currently largely conditioned by the ability to effectively develop and use the entrepreneurial potential of Generation Z (Dreyer & Stojanová, 2023).

As part of research focused on the relationship between students’ entrepreneurial interest and available forms of financing for start-ups, it was found that Generation Z considers EU funds to be the most attractive source of financing, which points to the importance of strategic support from public institutions (Zamfirache et al., 2023).

To successfully start and sustain a business, Gen Z must have strong financial literacy. Lack of financial literacy is a significant barrier to entrepreneurship because it impairs their ability to plan, raise resources, and prevent business failure. Financial literacy provides Gen Z with the necessary skills to overcome financial challenges, thereby improving their entrepreneurial readiness and intention to start a business (Rachapaettayakom & Sopanik, 2023; Hasan et al., 2024; Kang et al., 2024).

Financial literacy is positively related to Gen Z’s entrepreneurial intention. Higher financial literacy leads to greater confidence in managing finances, which increases the desire to start a business. Quantitative data suggests that financial literacy has a strong positive impact on entrepreneurial propensity (Jasin et al., 2023; Kang et al., 2024).

Based on theoretical assumptions and findings, we set three hypotheses for our research. We were interested in the relationship between subjective and subsequently objectively determined levels of financial literacy. While most studies focus on actual financial literacy, others emphasise the importance of self-knowledge. Generation Z often overestimate or underestimate their financial talents, and this discrepancy can damage their entrepreneurial confidence and judgement. Those who appropriately assess their financial literacy (calibrated) are in a better position to apply their knowledge in entrepreneurial situations. Excessive or insufficient self-confidence can lead to either excessive risk-taking or missed opportunities (Rachapaettayakom & Sopanik, 2023; Hasan et al., 2024; Riepe et al., 2022).

H3.

Calibration of financial literacy has an impact on interest in entrepreneurship. There is a statistically significant relationship between how respondents estimate their level of financial literacy and what it actually is and their interest in entrepreneurship.

3. Materials and Methods

The research focused on the financial literacy of Generation Z and its impact on their entrepreneurial ambitions and was carried out through a questionnaire survey, which is an effective tool for collecting quantitative data. The obtained data were analysed using statistical methods to verify the hypotheses based on theoretical foundations. To test the dependencies between variables, we applied the Chi-square test of independence, Cramer’s V as a measure of the intensity of the relationship, the sign scheme, and a multinomial logistic regression.

The quantitative research was supplemented by a qualitative component in the form of structured interviews, which provided a deeper context for the attitudes of Generation Z towards financial education and entrepreneurship. At the same time, the perspectives of representatives of educational institutions were also included in the survey, which allowed us to obtain a more comprehensive view of the issue.

3.1. Data Collection

The questionnaire survey was conducted between January and May 2025. We determined the minimum sample according to relationship (1). We used data from the Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic. There is no consensus in the literature on the range of years when people belonging to Generation Z were born. For example, Jayatissa (2023) defined them as people born after 1995. Weber (2024) wrote about the years 1995–2012, Nicholas (2020) about the years 1996–2010, and Goldring and Azab (2021) about the years 1997–2012. We included people born between 1999 and 2009 in Generation Z. We decided on the range of years 1999–2009 due to the lack of uniformity in the scientific community. Although the age range we chose (1999–2009) guarantees a consistent emphasis on people who are currently between the ages of 16 and 26—the late teenage to early adult stage—it also restricts the comparability of our results with those of other research conducted around the world. Generation Z is defined more broadly in many international contexts (e.g., 1995–2012).

Our sample might, therefore, underrepresent older Gen Z cohorts that are already more financially active (e.g., managing loans, mortgages, or independent finances). Although internal consistency is improved by this more focused approach, it should be considered when compared with datasets that include older age groups or different generational brackets. Therefore, they were chosen as boundary years that fall within the intervals of all the authors mentioned. To estimate the number of members of this generation in Slovakia in 2024, we used demographic data on the population of Slovakia. According to data from the Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic and demographic assumptions, the total population of Slovakia in 2024 was approximately 5.4 million. Generation Z would thus represent approximately 20% of this population. Based on these data, we can assume that Generation Z could include around 1.1 million people in 2024. We set the minimum sample size at 386 respondents according to the following formula:

where n—sample size; za—critical value of the standardised normal distribution; p—proportion of occurrence of the monitored character; e—permissible error rate; and N—the size of the base file.

The questionnaire survey was designed specifically for members of Generation Z, i.e., young people aged 16 to 26. The tool was designed as an electronic questionnaire distributed via the Google Forms platform, which enabled efficient and flexible data collection while ensuring a wide reach within the target population. The questionnaire was anonymous, which minimised the risk of response bias and increased the likelihood of authentic responses. Respondents were made aware of the goal of the study prior to their completion. Following the conclusion of data collection, the replies were exported and subjected to additional processing within the Microsoft Excel software environment. The questionnaire consisted mainly of closed and semi-closed questions with multiple-choice options and was systematically divided into five thematic units. The first part focused on the respondents’ demographic characteristics (age, gender, region of residence, and highest level of education) as well as their current employment situation (student, full-time or part-time employee, entrepreneur, unemployed, on parental leave, or disability pension recipient). This data served to create a comprehensive profile of the respondents in terms of their socio-economic background.

The subjective evaluation of financial literacy was the focus of the second section. It evaluated respondents’ personal financial literacy as well as the general financial literacy of the Slovak population. The third part focused on the objective verification of financial knowledge through a knowledge test that covered basic concepts from the areas of the pension system, insurance, loans, and investments. The results of this test made it possible to identify differences between the subjective perception and the real level of financial literacy of the respondents.

The fourth section focused on assessing the quality and accessibility of financial education within the formal school system. Respondents expressed their views on the current state and the need to increase the intensity of financial literacy education. The final, fifth part of the questionnaire examined the respondents’ entrepreneurial ambitions and attitudes towards entrepreneurship. This section also verified basic knowledge in the field of entrepreneurial activity.

3.2. Data Analysis

The Chi-square test of independence will be used to confirm the hypotheses. This test is suitable for examining the relationship of dependence between two categorical variables. In the case of the existence of a dependence between the level of financial literacy and the investigated characteristic of the respondents, we quantify the strength of the dependence using the Cramer’s V coefficient.

A statistical technique for figuring out whether two category variables have a significant relationship is the Chi-square test of independence (McHugh, 2013). In this test, the frequency of various combinations of the categories is summarised by creating a contingency table. The alternative hypothesis for this test suggests that there is an association between the two variables, whereas the null hypothesis asserts that they are independent. The Chi-square test compares the observed frequencies with the anticipated frequencies for every cell in the contingency table. The test statistic is computed using the following formula:

where the expected frequency in the i-th row and j-th column of the contingency table is Eij, and the observed frequency in the i-th row and j-th column is Oij (Franke et al., 2012). The following formula determines the anticipated frequency Eij for every cell assuming that the variables are independent:

where n is the grand total of all frequencies in the contingency table, ni is the total of observed frequencies in the i-th row, and nj is the total of observed frequencies in the j-th column. With degrees of freedom determined as (r − 1)·(c − 1), where r and c are the number of rows and columns in the table, respectively, the test statistic χ2 has a Chi-square distribution (Franke et al., 2012). The test’s outcome and significance are ascertained using the p-value obtained from the Chi-square distribution. If the p-value is smaller than the selected significance level, it indicates that there is a statistically significant relationship between the variables, and the null hypothesis is thus rejected.

The Chi-square test of independence is a powerful and widely used statistical tool. Anyway, it relies on several assumptions to ensure valid test results. Firstly, both the variables must be categorical, that means data for the test must be in the form of counts or frequencies of categories, not percentages or continuous data. Secondly, the observations should be independent, meaning that each observation can only contribute to one cell in the contingency table. Thirdly, the theoretical (expected) frequency in each cell of the contingency table should be at least 5 to ensure the accuracy of the Chi-square approximation of the test statistics. The last assumption is particularly important in larger contingency tables, where smaller expected frequencies can lead to inaccuracies in the test statistic (McHugh, 2013).

If the test found a relationship between the variables, we will measure the degree of that relationship using a Cramer’s V coefficient. This coefficient, which comes from the Chi-square statistic, represents the most widely used indicator of the relationship between two nominal variables. Its values should fall between 0 and 1, where 1 denotes a perfect association and 0 denotes no association at all. The formula for calculating Cramer’s V is the following (Blazek et al., 2023):

Subsequently, for a more detailed examination of the relationships between the level of financial literacy and interest in entrepreneurship, we used the so-called sign scheme. It is employed when we want to determine which particular groups of independent variables are dependent on one another. The use of this approach is only warranted if the Chi-square test has shown that there is a statistically significant relationship between the factors being examined. The quantification of the residual between the theoretical and empirical frequencies is the same notion that underpins both techniques. The sign scheme employs the residuals themselves to determine the largest positive and negative differences across combinations of categories of both qualitative variables, whereas the Chi-square test uses the squares of these residuals to obtain the value of the test criterion. The sign scheme’s name comes from the fact that the residual’s sign type indicates the deviation’s direction. The signs of differences are indicated in the calculation by signs that indicate the direction of the detected dependence. If the empirical frequency does not differ significantly from the expected one, this residual is marked with the sign “o”. The symbol “+” denotes a positive residual or a greater empirical frequency than the theoretical frequency. The notation “-” denotes a negative residual or a lower empirical frequency than the anticipated theoretical frequency. A one to three sign marking, which also denotes statistical significance, is used to emphasise the magnitude of the difference. The statistical significance of the residual is represented by one sign at the 95% level, two signs at the 99% level, and three signs at the 99.9% level (Rehak & Rehakova, 1978; Fajcikova et al., 2018).

For the same or a related purpose, such as correspondence analysis, the sign system is employed. Its straightforward applicability, especially in the case of dichotomous variables, is a benefit over this approach. Some software, like IBM SPSS Statistic 27 Statistics, does not allow the use of correspondence analysis if one of the variables is dichotomous. A nominal dependent variable is predicted from one or more independent variables using a multinomial logistic regression. Because it permits a dependent variable with more than two categories, it is frequently seen as an extension of binomial logistic regression. Like other regression techniques, a multinomial logistic regression can predict the dependent variable using nominal and/or continuous independent variables, as well as their interactions (Anderson & Rutkowski, 2008; Wen et al., 2023).

A multinomial logistic regression (MLR) model was used to test the effect of financial literacy calibration on entrepreneurial interest. Financial literacy calibration was found to be a combination of subjective and objective financial literacy factors. If literacy was high in both FL types, the respondent was assigned the variable realistically financially literate. If the subjective assessment was high but the objective assessment was low, the calibration was assigned the value of over calibrated. If subjective financial literacy was low but objectively high, it was under calibrated. The last variable created was realistically financially illiterate if both objective and subjective financial literacy were low. This model is suitable in situations where the dependent variable has more than two categories that are nominally distinct (without natural order). Let yij represent whether the result of category j (where j = 1, …, J) for observation i (where i = 1, …, N) is present (yij = 1) or absent (yij = 0). The set of predictor variables for the ith respondent is shown by the vector xi. The reference output category J is indicated. The multinomial logistic model then predicts the probability of category j as follows:

For reference category J, the following applies:

where aj is category j’s intercept; βj is the vector of coefficients for the predictors of category j. The estimation of the parameters aj and βj is performed using the maximum likelihood method using the following log likelihood function (de Jong et al., 2019):

In addition to testing the significance of the coefficients, we also assessed the overall performance of the multinomial logistic model using Nagelkerke’s R2 indicator, which represents the amount of explained variability in the dependent variable. This pseudo-coefficient of determination takes values from 0 (no explained variability) to 1 (fully explained variability) (Nagelkerke, 1991):

where the likelihood functions for the entire model and the intercept-only model are denoted by L(entire) and L(Null), respectively. SPSS frequently uses this indicator as a standard output for MLR models (Smith & McKenna, 2013).

The McFadden Pseudo R-squared statistic (Smith & McKenna, 2013) is also used to demonstrate the goodness of fit of the model. The formula is given as follows:

The odds ratio is expressed by Cox and Snell, which also shows how much the whole model has improved over the intercept model (the smaller the ratio, the better the improvement) (Cox & Snell, 1989).

In this investigation, we selected a significance level of 0.05 for all hypothesis testing. An IBM SPSS Statistics is used for statistical hypothesis testing and other analysis. As a complement to the quantitative survey, we also implemented a qualitative data collection method in the form of structured interviews. Although structured interviews have a higher predictive validity than other methods, they are not always used (Baumgartner et al., 2024). A structured interview is a research technique in which the researcher asks all respondents the same set of pre-prepared questions in the same order and format. This approach ensures the consistency of responses and allows for their systematic comparison across individual respondents, while also providing space to capture in-depth context and individual experiences (Gardner et al., 2022). A total of seven structured interviews were conducted as part of the qualitative research—five with university representatives and two with secondary school representatives. When selecting respondents, we purposefully considered the diversity of professional focus of individual institutions, while schools with both economic and non-economic profiles were represented. In this way, we tried to capture a wide range of perspectives on the issue of financial literacy and entrepreneurship education and thereby contribute to a holistic understanding of the research topic from the perspective of educational institutions.

3.3. Reliability and Validity

Since the subjective financial literacy factor is a one-item scale, it is not possible to perform a reliability analysis. The objective financial literacy factor consists of 8 items. In this case, a reliability analysis was performed. Based on the results, it can be seen that Cronbach’s Alpha reached a value of 0.799 (Table 1), while in scientific publications, various authors state a lower limit in the range of 0.6 to 0.8 to ensure reliability.

Table 1.

Reliability statistics.

Based on the professional literature and discussions with specialists in the fields of education and finance, the questionnaire’s content validity was guaranteed. Key components of financial literacy, including insurance, interest rates, pension pillars, and savings, were the focus of the questions. To make sure the respondents understood the items as the researcher intended, they were examined for clarity and unambiguity.

Through an open data processing process, we were able to guarantee fundamental norms of reliability in the qualitative portion of the study, which involved organised interviews with educators. The interviews were recorded in an MS Word text document and manually analysed, despite the fact that we did not employ any specialised coding software (such as NVivo or Atlas.ti). Following many readings, the responses from the participants were categorised thematically according to recurrent patterns of meaning. The coding was open-ended; after identifying important themes, the researchers categorised them into higher levels that aligned with the study’s goals. Data saturation was reached when the coding framework stabilised following the sixth interview.

4. Results

This part of the paper is dedicated to the presentation of the results obtained through quantitative and qualitative research methods. Within the quantitative analysis, we focus on the interpretation of the outputs resulting from the questionnaire survey and from the statistical processing of the data, with special attention paid to the analysis of the mutual relationships between the selected variables. For this purpose, appropriate statistical tools were applied, which made it possible to identify significant connections and verify the established hypotheses. The presented results also include findings from the qualitative part of the survey, carried out through structured interviews. These complement the quantitative data with contextual information that helps to gain a deeper understanding of the issue under study. By combining both approaches, we strive for an integral interpretation of the data which considers both the statistical significance of the relationships between the variables and the qualitative aspects reflecting the experiences and attitudes of the respondents.

4.1. Results Based on the Analysis of the Questionnaire Survey

The survey results confirmed the successful distribution of the questionnaire among the target group, which was Generation Z in the age range of 16 to 26 years (Table 2). Persons outside this category were automatically redirected to the end of the questionnaire after completing the demographic part and did not participate in the main part of the survey. This procedure ensured that only relevant answers from members of the target group were included in the analytical part of the research. The resulting number of valid respondents was 403 people. The sample consisted mainly of young adults aged 23 to 26, with a balanced gender representation. The regional distribution of respondents was even, with the highest number of participants from the Žilina region. The majority had a secondary education with a high school diploma and student status, which indicates that many are still in the study phase or at the beginning of their working careers. Based on the data from the first part of the questionnaire, we processed clear information about the sample of respondents:

Table 2.

Demographic data.

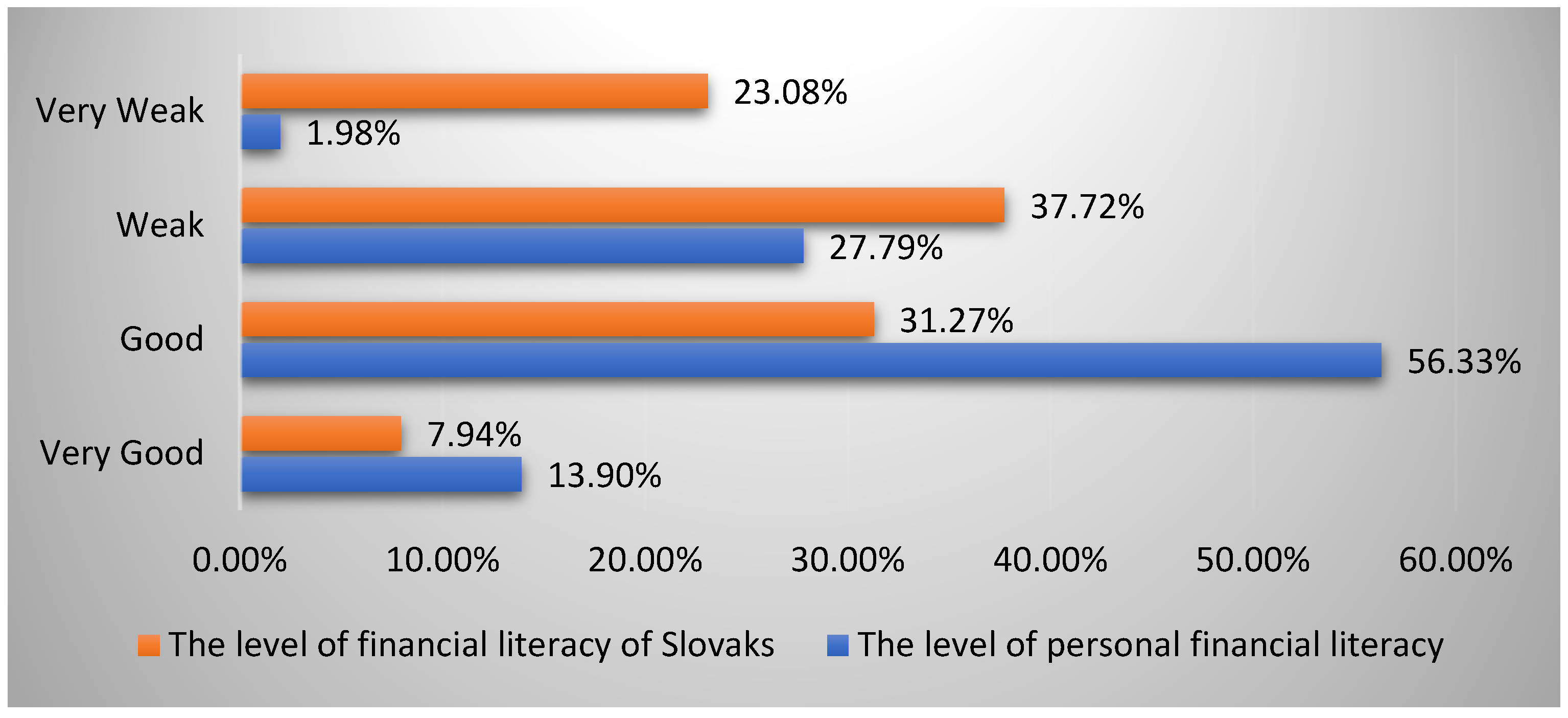

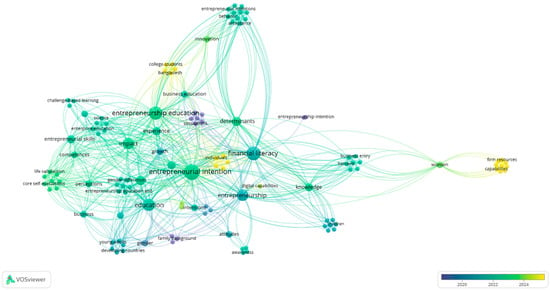

The Section 2 of the survey asked about respondents’ subjective self-evaluations of their financial literacy and personal money management practices, as well as how the Slovak Republic’s population was seen to be financially literate. The aim of this part was to identify how young people assess their own financial knowledge and skills, what financial habits they have adopted, and how they react to various financial situations. At the same time, we focused on their opinion on the general level of financial literacy in the Slovak population. The results of this part of the research are visualised in Figure 2. Based on the data obtained, it can be stated that most respondents primarily assess their financial literacy as good, while they see the financial literacy of Slovaks as weak.

Figure 2.

Self-assessment versus perception of the financial literacy of Slovaks. Source: Own processing (2025).

The most frequently reported monthly income of respondents ranged from EUR 701 to 1483 (27.5%), indicating a more stable financial background. Other significant groups represented incomes of EUR 301 to 500 (22.1%) and EUR 501 to 700 (20.3%), typical of young people with combined incomes. Lower incomes of up to EUR 300 (10.2%) and below EUR 100 (2.2%) indicate more significant financial dependence, while 9.4% of respondents earn more than EUR 1483, probably due to stable employment or business. When there is a lack of funds, respondents most often reduce expenses and save for essential items (37.2%). More than a quarter (26.6%) try to increase their income by working part-time or taking on additional activities. On the contrary, 20.8% solve the situation with a loan or credit card, which may pose the risk of debt. A total of 14.4% of respondents receive financial assistance from loved ones. As for the distribution of income, the largest part is directed towards current consumption, where 54.3% of respondents spend 40–60% of their income, with 50% most often mentioned (19.8%). As many as 18% spend almost all their income on consumption, which indicates a low level of savings. Approximately 12.3% of respondents allocate less than 30% of their income to consumption. Savings are the second most important category—27.5% save 20% of their income, 19.1% to 50%, while 5.2% do not save at all. Investing is not widespread, with 59.6% of respondents not investing, while 35% invest at least 10% of their income. A total of 46% of respondents do not pay attention to insurance, while 44.7% allocate 10–20% of their income to insurance. Loan repayment is the least represented; 69% of respondents are without instalments and only 17.8% repay 10–30% of their income.

The third part of the questionnaire, aimed at objectively assessing the level of financial literacy of respondents, was designed to verify the level of basic and slightly advanced knowledge in the field of financial literacy. Each question contained a clearly defined correct answer, thus ensuring the objectivity of the assessment in advance. The results of the knowledge part of the questionnaire showed that the financial literacy of young respondents is at the average to slightly below average level. They demonstrated stronger knowledge in topics such as interest rates and APR, but significant shortcomings appeared in investing, the pension system, and insurance products. Poor understanding of basic concepts or the difference between saving and investing indicates a limited understanding of the basic principles of financial decision-making.

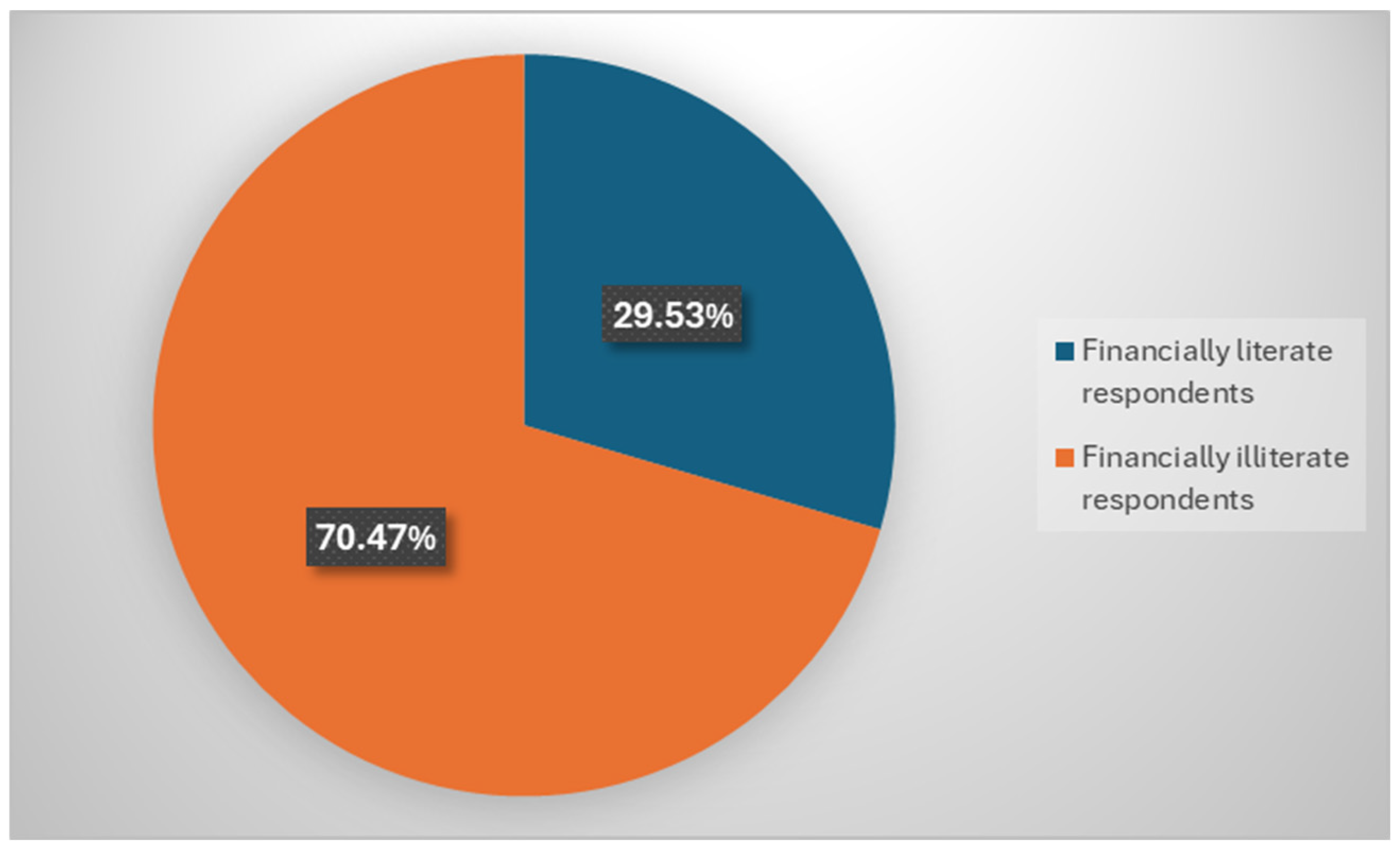

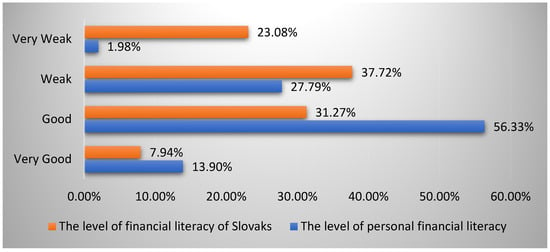

Although respondents rated their level positively, objective results indicate several fundamental shortcomings. Based on the results from this part of the questionnaire, we determined the classification of respondents in two categories—financially literate (five to eight correct answers) and financially illiterate (zero to four correct answers). The results are presented in the following graph:

The main objective of such an analysis was to determine whether the share of financially literate individuals reaches or exceeds the 75% threshold, which would signal a favourable level of financial literacy in the population. Out of a total of 403 respondents, 119 individuals (29.5%) were identified as financially literate based on the established criteria, as they answered at least six of the eight test questions correctly. On the contrary, most respondents—284 individuals (70.5%)—did not reach the required level and were classified as financially illiterate (Figure 3). These results point to a significantly low level of financial literacy among young people who are currently entering or have recently entered the labour market and are confronted with the need to independently decide on their income, expenses, savings, or liabilities. Given the growing impact of digitalization and the dynamic development of financial technologies, to which this age group is most exposed, it is essential that they have an adequate financial knowledge and competencies. The results also signal the need for systematic and targeted financial education in this population—primarily within the formal education system at the secondary and higher education levels, as well as through flexible forms of non-formal education, including online platforms aimed at developing practical skills and abilities in the field of personal finance.

Figure 3.

Respondents from the perspective of financial literacy. Source: Own processing (2025).

The fourth part of the survey focused on assessing the quality of financial education in various forms of education. Financial education in primary and secondary schools was rated as insufficient by 66.5% and 70% of respondents, respectively. Higher education in the field of finance was perceived as at least of average quality by 35.5%, while 40% considered it insufficient. Online courses were identified as a sufficient resource by only 19% of respondents; similarly, approximately 40% engage in self-education. A significant majority of respondents consider financial education in schools to be insufficient—as many as 80.1% support its strengthening. A total of 47.9% of respondents have not yet completed a financial course or training; 23.1% have completed training within a school, and 29% have received private education or self-education.

The Section 5 of the questionnaire examined the interest of Generation Z in entrepreneurship and the factors that support or limit it. Entrepreneurship is perceived as an important element of economic growth, but young people perceive the business environment in Slovakia as challenging due to bureaucracy and legislative obstacles. According to 36.2% of respondents, entrepreneurship in Slovakia is generally good but accompanied by administrative and tax obstacles. Another 36% consider entrepreneurship to be challenging due to the high tax burden and problems with financing, while 12.2% assess it as very difficult, mainly due to insufficient state support. Only 11.4% of respondents perceive the business environment as very favourable. Approximately 16.1% of respondents who plan to start a business soon expressed interest in entrepreneurship, and 27% expressed interest in learning more. The majority (37.2%) have a moderate interest, while 15.4% are not particularly interested in entrepreneurship, and 4.2% are not interested at all. Overall, 53.1% of respondents express at least some degree of interest in entrepreneurship but need more information and support. The main motivational factors for entrepreneurship among respondents who expressed interest included the flexibility in working hours and working methods (44.2%), financial independence (41.4%), and the possibility of self-realisation (35.7%). Only 14.9% perceived entrepreneurship to solve a specific problem in the market. The most common barriers to entry into entrepreneurship included concerns about risks and instability (40.4%), lack of capital (39.7%), insufficient knowledge or experience (36%), and fear of failure (32%). These factors show that, although the interest in entrepreneurship is relatively high, young people often face significant obstacles that hinder their entrepreneurial activities.

When it comes to preferred forms of financing, most respondents prefer their own resources (51.6%), which indicates a desire for independence and control over entrepreneurship. Bank loans or loans were preferred by 41.7% of respondents, help from family or friends by 25.3%, investment from an external investor by 22.6%, state subsidies or grants by 15.4%, and crowdfunding by only 5.7%. The results point to a relative lack of knowledge or low popularity of alternative forms of financing.

An analysis of the correct answers in the part aimed at verifying the respondents’ entrepreneurial knowledge allows a more detailed assessment of their level of readiness and understanding of key concepts and principles of entrepreneurship. The results show that 54.1% of respondents correctly identified the position of an entrepreneur in society, most often the ability to generate profit. The definition of a trade was recognised by 66.5% of the survey participants. The legal form of a limited liability company (L.L.C.) was correctly identified by 52.9% of the respondents. In the area of financial knowledge, 62.3% of the respondents were able to define their own financial resources and 69.2% demonstrated knowledge of the definition of external financial resources. The concept of free cash flow was correctly understood by 74.7% of respondents. These results indicate that, although most young people have basic knowledge in the field of entrepreneurship and finance, significant gaps persist that can negatively affect their readiness and ability to successfully implement themselves in a business environment.

Based on the results of the questionnaire survey, we subsequently moved on to the analysis of relationships using selected statistical methods. For the purposes of the paper, we divided the statistical analysis into three parts, each of which was linked to a specific hypothesis.

4.2. Data Analysis Using Selected Statistical Methods

We tested the effect of subjective financial literacy on interest in entrepreneurship in the first hypothesis. As can be seen in Table 3, the total number of responses was 403, with none of them being excluded from the statistical analysis due to error rates.

Table 3.

Case processing summary.

The contingency table of expected frequencies (Table 4) presents the theoretically predicted distribution of respondents into individual categories of financial literacy level and interest in entrepreneurship, assuming zero dependence between these variables. The values in the table serve as the basis for comparison with the observed frequencies and allow for the subsequent verification of the existence of a statistically significant connection between financial literacy and interest in entrepreneurship.

Table 4.

Contingency table of expected frequencies.

Assuming a high level of financial literacy, it would be expected that 84.5% of respondents would show a medium interest in entrepreneurship, 34.9% rather low, 61.4% rather high, 9.6% very low, and 36.6% very high interest. In the case of average financial literacy, the expected distribution of respondents would be as follows: 41.7 with an average interest in entrepreneurship, 30.3 with rather high interest, and 18.1 with very high interest. The contingency table (Table 4) of the expected frequencies shows that the conditions for reliable use of the Chi-square test of independence are not met in both conditions. To ensure the validity and reliability of the results, we adjusted the categories in variable financial literacy. The categories very weak and weak were merged into the category very weak to weak, since this is a link between the two categories with the lowest level of financial literacy.

The test value in Table 5 reached 22.893, with df = 8 and p-value 0.004, which is below the significance level α = 0.05. Thus, we reject the null hypothesis and confirm a statistically significant dependence between the variables. We further tested the contingency coefficient to assess the intensity of this dependence, which can be low to medium. The adjusted residuals are also important, which indicate the most pronounced manifestations of dependence in specific cells of the table. To assess the intensity of the relationship, we will use the same scale as in the first hypothesis.

Table 5.

Pearson Chi-square test of independence.

Because it is less than the bottom limit of moderately strong dependency, 0.3, the Cramer’s V coefficient, which is displayed in Table 6, obtained a value of 0.169, indicating a weak level of dependence between the variables. We are able to reject the null hypothesis and validate the statistical significance of the contingency coefficient because the p-value (approximate sig.) of 0.004 is less than the predetermined level α = 0.05. This demonstrates that there is a substantial and non-random reliance between the variables.

Table 6.

Systematic measures.

The conclusion of the analysis was extended by the output of the adjusted residuals, shown in Table 7, which help to identify specific cells in the contingency table where the most significant differences between the actual and expected number of respondents appeared. The residuals, or the corresponding signs, show the extent to which the observed values deviate from those that would occur if the variables were completely independent.

Table 7.

Sign scheme.

These results show specific patterns of behaviour, especially in the group with a lower to average literacy, which supports the existence of a statistically significant relationship between subjective financial literacy and interest in entrepreneurship. Although the strength of this relationship is weak, the trend suggests that perceived financial literacy can influence attitudes towards entrepreneurship, which is important in young people’s decision-making in this area. We then analysed the impact of objective financial literacy on interest in entrepreneurship through the second hypothesis.

Based on Table 8, it can be concluded that all measurements entering the Pearson Chi-square test were appropriate and none of the responses were excluded, which means that all 403 responses from the respondents participated in the test.

Table 8.

Case processing summary.

We can conclude that we accept the hypothesis H2 based on the Pearson Chi-square test results, which showed a value of 0.000, which was below the alpha significance level of 0.05. Interest in becoming an entrepreneur is influenced by objective financial literacy. There is a statistically significant correlation between respondents’ interest in entrepreneurship and their level of financial literacy. With df = 12, the test value in Table 9 came to 49.204. Since only 15% of the cells had an expected frequency lower than five and none of them were zero, it is also evident that the test’s requirements are met.

Table 9.

Pearson Chi-square test of independence.

The value of the Cramer’s V coefficient (Table 10) reached the level of 0.202, which is less than the upper limit of the interval 0.3 for weak dependency, according to Table 8. However, it may also be said that the dependence’s strength is noteworthy.

Table 10.

Systematic Measures.

The results of the cross-tabulation and adjusted residuals (Table 11) showed a statistically significant relationship between objective financial literacy and interest in entrepreneurship. Individuals with a very good financial literacy showed a very high interest in entrepreneurship significantly more often than would be expected under the assumption of independence of the variables (adjusted residual = 3.7; p < 0.01). Conversely, individuals with a very poor financial literacy had a very low interest in entrepreneurship significantly more often (adjusted residual = 2.1). The highest deviation in the positive direction appeared among respondents with a good financial literacy and average interest in entrepreneurship (adjusted residual = 4.0), which indicates a possible latent potential in this group. Negative deviations (e.g., adjusted residual = −2.4 for low financial literacy and high entrepreneurial interest) indicate combinations that occur less frequently in the population than would be expected. These findings support the hypothesis that higher levels of financial literacy are associated with higher levels of entrepreneurial ambition. In practical terms, this means that increasing financial literacy can be an effective tool to promote entrepreneurship in the population.

Table 11.

Sign scheme.

It is possible to conclude from a comparison of the findings regarding the impact of subjective and objective financial literacy on interest in entrepreneurship that when looking at the impact of subjective financial literacy, when respondents evaluated financial literacy on their own, and objective financial literacy (by responding to eight questions about financial literacy), the influence was confirmed in both cases. When comparing Cramer’s V for subjective FL (0.169) and objective FL (0.202), we can state that, although in both cases there is a weak dependence, the objective measurement of financial literacy has a slightly higher predictive value in relation to entrepreneurial interest. This indicates a higher informative value of factual knowledge compared to self-assessment. Nonetheless, there were significant variations in the evaluation of financial literacy. Just 120 respondents, according to their self-assessment, had a poor or very poor financial literacy. However, according to the objective assessment, this number is as high as 284, which represents an increase of almost 140%, which is an increase of 40.7 percentage points. On the contrary, the number of financially literate respondents in the self-assessment decreased from 283 respondents to 119. This is a decrease in more than half of the respondents, while in terms of percentage points, it is a decrease of 40.7. We decided to also investigate the impact of objective financial literacy on interest in entrepreneurship due to the elimination of the Dunning–Kruger effect, i.e., that people generally tend to increase their qualifications and thus be less objective. Ultimately, it can be stated that only 94 respondents are realistically financially literate. On the contrary, 95 respondents were realistically financially illiterate. A total of 189 respondents overestimated their financial literacy, while only 25 respondents underestimated it. This confirmed the occurrence of the Dunning–Kruger effect in the research.

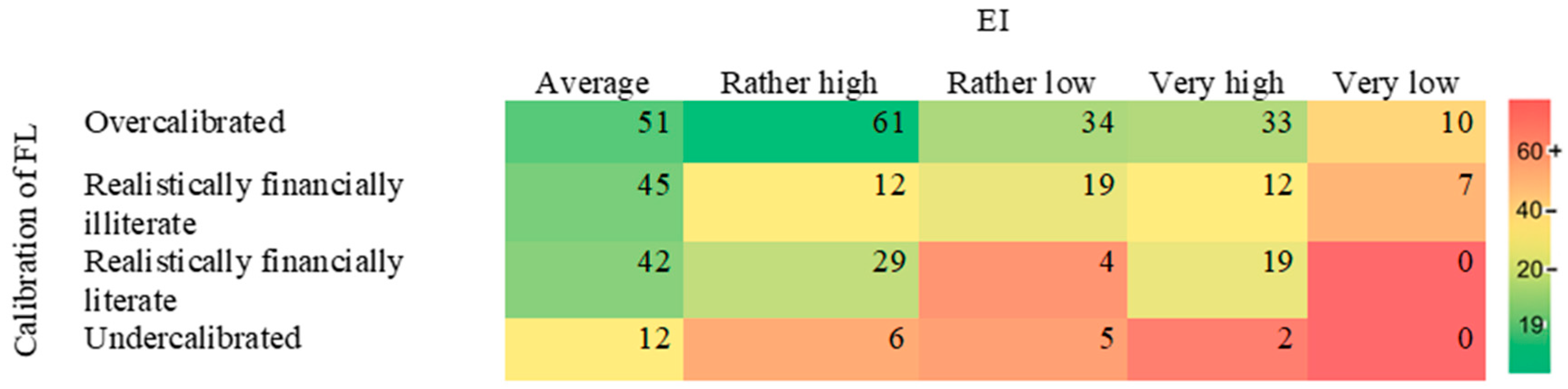

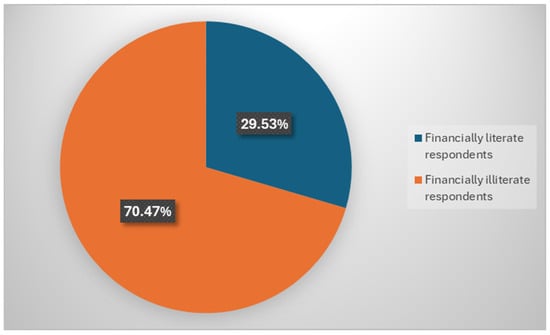

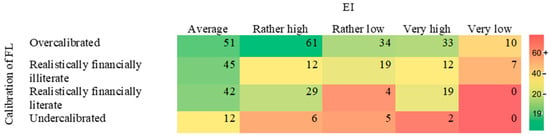

Based on the heatmap (Figure 4), which visualises the distribution of EI among groups according to financial literacy calibration, realistically financially literate individuals achieve the highest level of interest in entrepreneurship. On the contrary, groups with an incorrect calibration (especially over calibrated) show a discrepancy between high self-confidence and real knowledge, which can lead to the overestimation of their abilities. These respondents achieved a relatively high interest in entrepreneurship but without a knowledge base. The under calibrated group shows low interest despite having an above-average level of knowledge—supportive education aimed at increasing self-confidence could help here. Based on the above information, it is appropriate to expand the quantitative analysis by using a multinomial logistic regression. The goal is to verify whether the calibration of financial literacy significantly affects the level of interest in entrepreneurship among respondents. The original multinomial regression captured the singularity of the Hessian matrix, which indicates too few cases in some categories (Figure 4). Therefore, the dependent variable interest in entrepreneurship was divided into three levels—low, average, and high—and the model was re-estimated, which improved the stability and interpretability of the results. We did this because the conditions for performing the given analysis were met. Other conditions include the absence of multilinearity between the predictors. Since we only have one predictor, this relationship does not need to be verified. Also, there are no outliers between the variables, since respondents had the opportunity to choose specific options.

Figure 4.

Heatmap of calibration of FL and EI. Source: Own processing (2025).

The multinomial logistic regression with the dependent variable of entrepreneurial interest (low, medium, and high; reference = high) was significant compared to the intercept-only model, χ2(6) = 42.98, p < 0.001 (Table 12), indicating that the calibration of financial literacy significantly affects the level of entrepreneurial interest, which means that we accept hypothesis H3. The detailed effects of the individual calibration groups are presented in the Parameter Estimates table.

Table 12.

Model fitting information.

The pseudo R2 values (Table 13) show that the model explains between 5.1% (McFadden) and 11.5% (Nagelkerke) of the variability in entrepreneurial interest. Although these are relatively low proportions, they are in line with expectations in behavioural research, where outcome behaviour is often influenced by a number of internal and external factors. These results thus point to the existence of a weak but statistically significant calibration effect of financial literacy.

Table 13.

Pseudo R-Square coefficients.

The likelihood ratio test (Table 14) confirmed the statistically significant contribution of the variable “financial literacy calibration” to explain entrepreneurial interest (χ2 = 42.983; df = 6; and p < 0.001). This result supports the inclusion of calibration in the final model and confirms its importance as a predictor of the level of entrepreneurial interest.

Table 14.

Likelihood ratio test.

The variable calibration of financial literacy was included as a predictor (Table 15), divided into four groups: (1) over calibrated, (2) under calibrated, (3) realistically financially illiterate, and (4) realistically financially literate, which was the reference category in the model. The results show that all three analysed calibration groups show a statistically significantly lower probability of being classified in higher levels of interest in entrepreneurship (“Average” or “High”) compared to realistically financially literate individuals. When comparing the probability of being classified in the “Average” category versus the “Low” category, over calibrated respondents (B = −1.803; p = 0.002) have an 83.5% lower chance of being in this category than realistically literate respondents (Exp(B) = 0.165). The under calibrated (B = −2.204; p < 0.001) have an 89.0% lower probability (Exp(B) = 0.110) and the realistically financially illiterate (B = −1.476; p = 0.048) have a 77.1% lower chance (Exp(B) = 0.229). In the case of the “High” versus “Low” category, the effect is even more pronounced. Over calibrated respondents (B = −2.565; p < 0.001) have a 92.3% lower probability of being in the group with high entrepreneurial interest (Exp(B) = 0.077). In the under calibrated (B = −1.726; p = 0.002) group, this probability is lower by 82.2% (Exp(B) = 0.178) and in the realistically financially illiterate (B = −2.015; p = 0.009) group by 86.7% (Exp(B) = 0.133). It is noteworthy from the perspective of research interest that every difference discovered was statistically significant (p < 0.05), supporting the idea that the degree of interest in entrepreneurship is significantly influenced by the calibration of financial literacy. The results also indicate that over calibration—i.e., overestimation of one’s own financial abilities—is most associated with low entrepreneurial interest, which may be related to metacognitive limitations and a reduced ability to realistically evaluate one’s assumptions for entrepreneurship.

Table 15.

Likelihood ratio test.

4.3. Qualitative Data Analysis

The analytical part focused on the qualitative aspects of financial education and was carried out through structured interviews with teaching staff working in secondary schools and universities. Respondents were selected for their professional focus and direct participation in teaching subjects related to financial literacy and entrepreneurship. When selecting respondents, emphasis was placed on the diversity of institutions represented—the research included representatives of schools with both economic and non-economic focuses to capture diverse approaches and experiences in the field of financial education. The aim of this part of the analysis was to identify current challenges, needs, and opportunities for improving teaching aimed at developing financial literacy and entrepreneurial competencies from the perspective of educational institutions. The interviews focused on four main areas: the perception of the level of financial literacy of students, their interest in entrepreneurship, evaluation of the content and forms of teaching, as well as suggestions for streamlining and innovations in this area. The knowledge gained was subsequently analysed and categorised into five main thematic areas that summarise the most important findings of the qualitative research:

1. Status of financial education: All educators agreed that financial education is not sufficiently anchored in Slovak schools, especially in schools with a technical or general focus. Interest in financial topics: Students’ interest in financial topics depends on the practicality of the teaching. Practical topics (personal): The analytical part focused on the qualitative aspects of financial education and was carried out through structured interviews with teaching staff working in secondary schools and universities. Respondents were selected for their professional focus and direct participation in teaching subjects related to financial literacy and entrepreneurship. When selecting respondents, emphasis was placed on the diversity of institutions represented—the research included representatives of schools with both economic and non-economic focuses to capture diverse approaches and experiences in the field of financial education. The aim of this part of the analysis was to identify current challenges, needs, and opportunities for improving teaching aimed at developing financial literacy and entrepreneurial competencies from the perspective of educational institutions. The interviews thematically focused on four main areas: the perception of the level of financial literacy of students, their interest in entrepreneurship, evaluation of content and forms of teaching, as well as suggestions for streamlining and innovations in this area. The knowledge gained was subsequently analysed and categorised into five main thematic areas that summarise the most important findings of the qualitative research:

2. Interest in financial topics: Students’ interest in financial topics depends on the practicality of the teaching. Practical topics (personal budget, paycheque, and loans) are preferred over abstract concepts.

3. The connection between financial literacy and entrepreneurship: A positive correlation was confirmed between financial literacy and interest in entrepreneurship; it was most pronounced among students of economics.

4. Quality of teaching: Educators assess the teaching of financial literacy as not very practical and not considerate of the current needs of students. Topics such as investing, insurance, or digital finance are only minimally covered.

5. Changes needed: Most educators support the introduction of a separate subject of financial literacy or the integration of these topics into existing subjects. Systemic changes are considered necessary.

A survey of 403 members of Generation Z revealed that although most young people rated their financial literacy positively, objective testing confirmed a low level, with only 29.5% classified as financially literate. Comparing subjective and objective financial literacy showed that both are associated with entrepreneurial interest, but objective measures have a slightly higher predictive value.

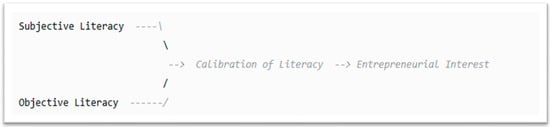

The next diagram (Figure 5) illustrates how subjective financial literacy (self-assessed knowledge) and objective financial literacy (measured knowledge) interact to produce calibrated financial literacy (alignment between self-assessment and actual competence). Calibrated literacy functions as a mediating factor that enhances the predictive power of financial literacy in relation to entrepreneurial interest. Students with both a high objective knowledge and accurate self-assessment demonstrate the strongest propensity for entrepreneurship, whereas miscalibration—particularly overestimation of one’s skills—may lead to suboptimal financial decision-making and lower entrepreneurial preparedness.

Figure 5.

Relationship between subjective, objective, and calibrated financial literacy and business interest. Source: Own processing (2025).

The analysis also confirmed the presence of the Dunning–Kruger effect, as the majority of respondents overestimated their financial abilities. Calibration of financial literacy proved to be a statistically significant predictor of entrepreneurial interest, with the lowest levels observed among respondents who overestimated their knowledge. Structured interviews further highlighted persistent shortcomings in financial education in Slovakia, strongly influenced by the type of educational institution. While schools with an economic focus integrate financial literacy more systematically, technical and humanities-oriented schools lack both qualified staff and sufficient curricular space. These structural disparities directly affect students’ entrepreneurial interest and preparedness. At the same time, students naturally engage with financial topics when taught through practical and interactive methods. Strengthening the connection between financial literacy and entrepreneurial competences therefore emerges as a key educational priority, essential for shaping the skills of the next generation and supporting sustainable economic development. Table 16 shows the summary results of the research.

Table 16.

Summary of research.

5. Discussion

The analysis of the survey results shows a significant discrepancy between the subjective and objective assessment of financial literacy of respondents belonging to Generation Z. Although most of the research participants perceived their own financial literacy as good, objective testing revealed that up to 70.5% of them did not reach the required level and were therefore classified as financially illiterate. This observed discrepancy confirms the presence of the Dunning–Kruger effect, whereby individuals with lower knowledge tend to overestimate their abilities, while those with a higher competence may underestimate their own skills. In the context of financial literacy, this means that individuals with weaker knowledge might feel overconfident when making financial decisions, increasing the risk of errors or impulsive choices. Addressing this effect in educational programmes can be achieved through a combination of theoretical instruction and practical exercises, including feedback and real-world examples. Particularly effective are self-assessment tests and simulations that highlight the gap between participants’ subjective evaluations and their objectively measured performance.

Such approaches can enhance metacognitive skills—the ability to recognise the limits of one’s knowledge—and thereby improve both the effectiveness of financial education and young people’s readiness for entrepreneurial and financial decision-making. In the context of financial decision-making, this phenomenon can have serious consequences (Xu & Jiang, 2024). The data obtained point to a relatively low level of financial knowledge of the younger generation, which, on the other hand, is currently exposed to increasingly complex and complicated financial products and technologies in the digital environment. The survey confirmed that more than 80% of respondents perceive financial education in schools as insufficient, with almost half of them not having completed any formal financial education. This result corresponds to the criticism directed at the current teaching of financial topics, which several authors describe as fragmented and impractical (Arthur, 2012; Chen et al., 2023). The current integration of financial education into general subjects, such as mathematics or civics, does not provide students with the relevant and applicable skills needed for real life.

A key recommendation based on the knowledge gained is, therefore, the implementation of a separate, mandatory subject, “Financial Education,” at least in secondary schools. The content structure should reflect the needs of the modern digital economy and include topics such as personal finance management, loans, savings, investing, digital financial instruments, and the basics of entrepreneurship, as well as digital security and applications of artificial intelligence in the financial sector—e.g., robo-advisors and predictive algorithms (Farah et al., 2023; Peláez-Sánchez et al., 2024). This need for the introduction of systematic and practically orientated financial education is also emphasised by Burchi et al. (2021), drawing attention to its potential to develop entrepreneurial skills at a pan-European level.

Additionally, the study’s findings support the notion that financial literacy and interest in entrepreneurship are related, directly confirming the findings of authors such as Xu and Jiang (2024) and Andriyani and Rochmatullah (2025). Higher objective and subjective financial literacy have been shown in numerous studies to have a favourable impact on entrepreneurial interest and intention, particularly among students and young adults. The capacity to handle funds, identify business possibilities, and make well-informed decisions are all critical components of entrepreneurship, and financial literacy improves these skills (Guo et al., 2024; Kang et al., 2024; Tambunan et al., 2023; R. Li & Qian, 2020). According to certain studies, financial literacy directly increases the interest and intention of people to start their own business (Guo et al., 2024; Kang et al., 2024; Xu & Jiang, 2024; Rapina et al., 2023). Other research shows that financial literacy indirectly increases entrepreneurial desire through mediators like self-efficacy or personal financial management, but they do not indicate a substantial direct effect (Nurjanah et al., 2024).

In a Chinese study by Xu and Jiang (2024), it was shown that the influence of financial literacy on entrepreneurial behaviour is enhanced by financial education. In the Indonesian context, Tambunan et al. (2023) confirmed that financial literacy and self-motivation have a positive impact on entrepreneurial intention by strengthening self-efficacy. In contrast, Alshebami and Al Marri (2022) did not find a direct relationship between financial literacy and entrepreneurial intention in their research in Saudi Arabia, which may point to cultural and systemic differences in educational approaches.

Higher levels of objective financial literacy—defined as actual knowledge and skills—are consistently linked to increased entrepreneurial interest, intention, and participation, according to several studies conducted across a range of demographics and circumstances. Advanced financial literacy increases the likelihood of starting a business, identifying chances for entrepreneurship, and performing better in entrepreneurial endeavours (Guo et al., 2024; R. Li & Qian, 2020; Burchi et al., 2021; Utami & Wahyuni, 2022).

Some studies point out that, even though the majority of research points to a positive correlation, financial literacy by itself might not always be a reliable indicator of entrepreneurial interest, particularly when contrasted with other variables like motivation or educational interventions (Effendi et al., 2023; Andriyani & Rochmatullah, 2025). But these are the exceptions, not the rule.