Modeling the Determinants of Stock Market Investment Intention and Behavior Among Studying Adults: Evidence from University Students Using PLS-SEM

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Foundation

2.2. Research Hypotheses

2.2.1. Digital Skills

2.2.2. Financial Competence

2.2.3. Risk Tolerance

2.2.4. Economic Well-Being

2.2.5. Collective Decision-Making

2.2.6. Overconfidence Bias

2.2.7. Social Interaction

2.2.8. Individuals’ Stock Market Investment Intentions

2.2.9. The Indirect Influence via Stock Market Investment Intention

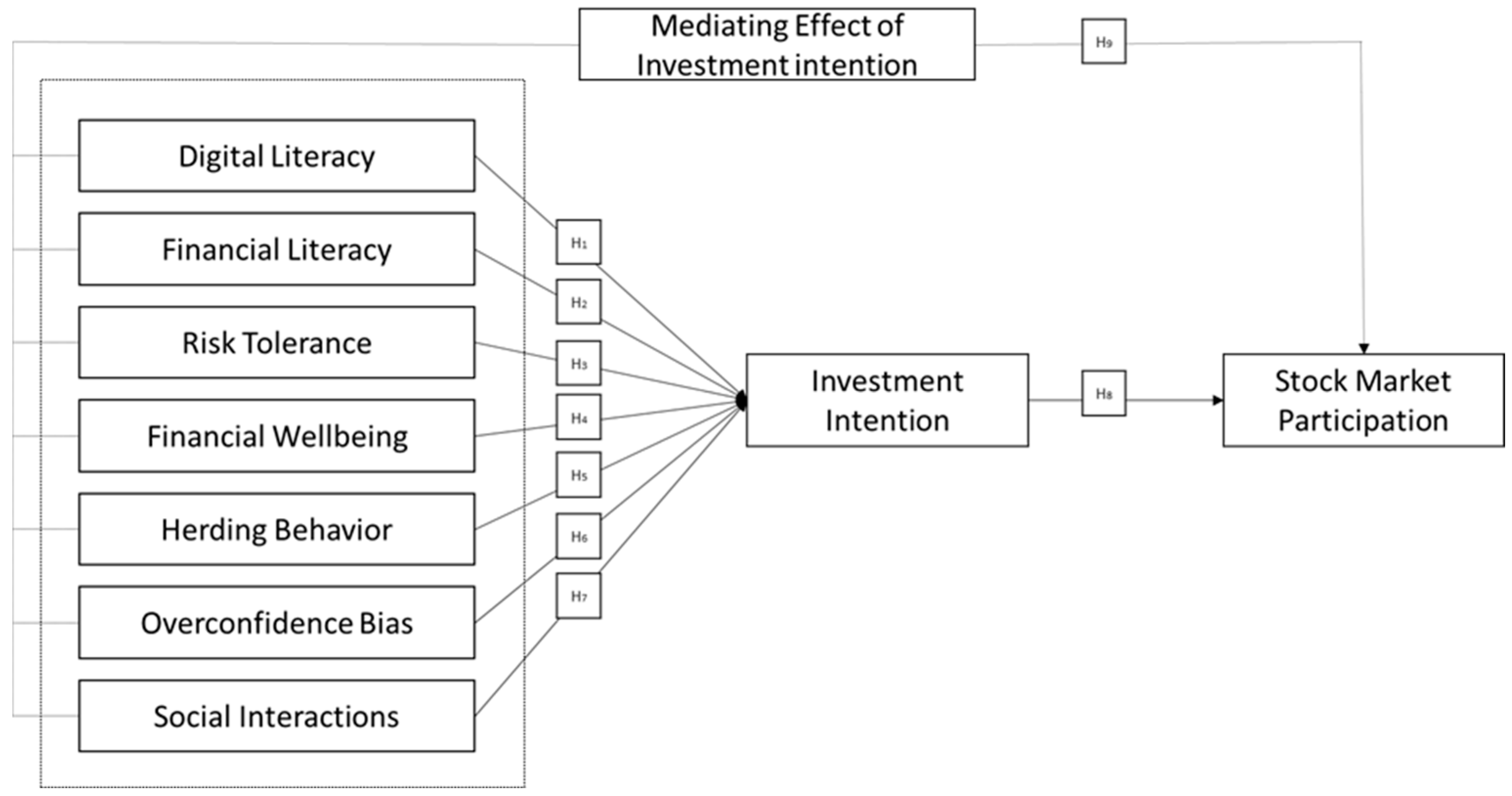

3. Research Framework

3.1. Target Population and Sample Selection

3.2. Variable Measurement

3.3. Normality Assumption

3.4. Data Processing and Analysis

4. Data Interpretation

4.1. Participant Characteristics

4.2. Reliability and Validity

4.3. Structural Model Results

4.4. Mediating Effects

4.5. Cross-Group Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Theory and Practical Implications

7. Limitations and Future Research

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| INFE | International Network on Financial Education |

Appendix A

| Key Constructs | Items Description |

|---|---|

| Digital Competencies | Adapted from Choi et al. (2023) |

| Tolerance for risk | Investing in the stock market feels like a risky choice |

| I’m worried about losing money because of how unpredictable the stock market is | |

| I’d rather put my money into stocks than keep it in a bank account | |

| I view investment risks as opportunities | |

| I see myself as someone willing to take high risks | |

| Financial stability | I’m actively working to secure my financial future |

| I’m currently falling behind with my finances | |

| My financial situation dictates how I live my life | |

| I’m just barely managing financially | |

| I’m concerned that my current savings or future savings won’t be enough | |

| Behavioral herding | The amount I invest often depends on what others (like my broker or a financial consultant) think |

| I feel confident in the accuracy of my investment choices | |

| I trust information about investments that comes from my friends | |

| I trust information about investments that comes from my colleagues | |

| I trust information about investments that comes from my relatives | |

| Investor overconfidence | I trust my own judgment when it comes to evaluating the securities prices in my investment portfolio |

| My past profitable investments were mostly thanks to my unique investment skills | |

| I’m good at predicting future stock prices | |

| I feel capable of evaluating securities prices in my investment portfolio on my own. | |

| I believe my market knowledge and skills enable me to beat the market | |

| Social influence | I maintain close social relationships with my friends who are also investors |

| I spend a lot of time interacting with my friends who are investors. | |

| I communicate frequently with my friends who are investors | |

| I’m very active in conversations related to investing | |

| I genuinely enjoy discussing investments with other people (investors) | |

| The intention behind stock investments | I plan to invest in the stock market frequently |

| I will encourage my friends and family to invest in the stock market | |

| I intend to invest in the stock market in the near future | |

| I believe the Stock Exchange is an appealing investment channel | |

| Direct involvement in the stock market | My investment portfolio is diversified across various asset classes (e.g., stocks, bonds, cash, real estate) |

| I invest in stocks that I am confident will grow significantly in the future | |

| I prioritize investing in stocks that promise quick profits | |

| I frequently buy and sell stocks/shares | |

| I manage my portfolio primarily for maximum gross return, rather than focusing on tax or cost efficiency. |

| Financial Knowledge | Answer |

|---|---|

| Imagine that five brothers were given 10 million soums as a gift. If the brothers divide the money equally, how much will each of them receive? | Open answer |

| Now imagine brothers have to wait a year to get their share. What they can buy today in a year | more the same amount fewer goods I don’t know |

| Let’s say you deposit $100 into a foreign currency savings account with a guaranteed interest rate of 5% per annum. No additional deposits or withdrawals will be made from the account. How much money will be in your account at the end of the first year after the interest is paid? | Open answer |

| And how much will be in this account in five years? | over $110 Exactly $110 Less than $110 Cannot be determined from the given information |

| Investments with high returns have high risk | True False |

| High inflation means a rapid rise in the cost of living | True False I don’t know |

| The more diversified your savings, the lower the risk of losing all your money | True False I don’t know |

| Financial relations | |

| I prefer to spend money rather than save it for a long time! | Completely agree Partially agree Completely disagree |

| I live for today and don’t think about tomorrow (I believe it will be good on its own!) | Completely agree Partially agree Completely disagree |

| Financial actions | |

| Who makes decisions about financial expenses in your family? | Myself I make financial decisions after consulting with my family members. These decisions are made by individuals outside of your family. I don’t know |

| I carefully monitor my financial affairs (income and expenses) | Never Rarely Often Always I don’t know |

| What savings instruments have you used in the last 12 months? | In national currency at home in cash In foreign currency in cash I bought livestock I received agricultural products during the season (wheat, feed, etc.) I kept it in national currency in a bank deposit I kept it in foreign currency in a bank deposit. I bought bonds I bought cryptocurrency I participated in a local informal savings game (local informal savings game) I bought stocks I participated in various gambling games (X-bet, online casinos) I bought a car I bought a house I invested in my acquaintance’s business I engaged in online trading activities. Other _______ I haven’t saved money |

| Did your living expenses exceed your income in the last 12 months? | Yes/No |

| What measures did you take the last time this happened? | I withdrew money from the deposit I reduced expenses, spent less, postponed the planned expenses. Finding additional work I requested financial assistance from the government. I borrowed money from my family and friends I got a loan or salary advance from my employer I took out a loan by pledging my valuables. I used bank loans I got an online loan I missed payments Other________ |

| Which of the following financial services have you used? | Consumer credit Bank current account Bank transaction account Currency exchange Credit card Debit card (bank plastic card) Mortgage loan Internet, mobile banking Insurance policies Leasing services Investments in company shares Domestic and foreign money transfers Other services None |

| Item Number | Question |

|---|---|

| 5 | Save Internet documents, photos, or video files you find |

| 9 | Express my opinion of “like/dislike” on others’ posts |

| 10 | Comment on others’ posts |

| 13 | Take photos or videos using digital devices |

| 15 | Upload Internet posts using digital devices |

| 16 | Upload pictures or videos using digital devices |

| 17 | Convert document formats using digital devices |

| 22 | Change device passwords |

| 23 | Delete files stored on the device |

| 27 | Be aware of the mental side effects that can result from excessive device use |

| 28 | Independently troubleshoot issues related to device/app installation |

References

- Ahmad, M., & Shah, S. Z. A. (2020). Overconfidence heuristic-driven bias in investment decision-making and performance: Mediating effects of risk perception and moderating effects of financial literacy. Journal of Economic and Administrative Sciences, 38(1), 60–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I., & Driver, B. L. (1992). Application of the theory of planned behavior to leisure choice. Journal of Leisure Research, 24(3), 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, F., & Das, N. (2019). Predictors of investment intention in Indian stock markets: Extending the theory of planned behaviour. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 37(1), 97–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhter, T., & Hoque, M. E. (2022). Moderating effects of financial cognitive abilities and considerations on the attitude–intentions nexus of stock market participation. International Journal of Financial Studies, 10(1), 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Afeef, M. A., & Alsmadi, A. A. (2025). Digital empowerment: Unraveling the impact of digital literacy on financial mastery. Discover Sustainability, 6(1), 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristei, D., & Gallo, M. (2021). Financial knowledge, confidence, and sustainable financial behavior. Sustainability, 13(19), 10926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakar, S., & Yi, A. N. C. (2016). The impact of psychological factors on investors’ decision making in Malaysian stock market: A case of Klang Valley and Pahang. Procedia Economics and Finance, 35, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, Y. D. P., Nanda, S. S., Sharma, S., & Sahoo, T. R. (2022). Examining risk absorption capacity as a mediating factor in the relationship between cognition and neuroplasticity in investors in investment decision making. International Journal of Financial Studies, 10(1), 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benayad, K., & Aasri, M. R. (2023). Behavioral biases and investment decisions of SMEs managers: Empirical analysis within the Moroccan context. International Journal of Financial Studies, 11(4), 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, S. A., Lone, U. M., SivaKumar, A., & Krishna, U. G. (2025). Digital financial literacy and financial well-being–evidence from India. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 43(3), 522–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdan, S., Brmalj, N., & Mujačević, E. (2023). Impact of liquidity and investors sentiment on herd behavior in cryptocurrency market. International Journal of Financial Studies, 11(3), 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondia, R., Biswal, P. C., & Panda, A. (2019). The unspoken facets of buying by individual investors in Indian stock market. Review of Behavioral Finance, 11(3), 324–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepeda-Carrion, G., Cegarra-Navarro, J. G., & Cillo, V. (2019). Tips to use partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) in knowledge management. Journal of Knowledge Management, 23(1), 67–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J., Choi, S., Song, K., Baek, J., Kim, H., Choi, M., Kim, Y., Chu, S. H., & Shin, J. (2023). Everyday digital literacy questionnaire for older adults: Instrument development and validation study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 25, e51616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enescu, A. G., & Raileanu Szeles, M. (2024). Portfolio allocation, risk aversion, and digital literacy among the European elderly. Economics, 18(1), 20220072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A. G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, N., & Singh, S. (2018). Financial literacy among youth. International Journal of Social Economics, 45(1), 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grable, J. E., & Joo, S. H. (2004). Environmental and biopsychosocial factors associated with financial risk tolerance. Financial Counseling and Planning, 15(1), 73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2014). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson new international edition. Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N. P., & Ray, S. (2021). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using R: A workbook (p. 197). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M. T. I., Tan, S. H., & Chong, L. L. (2017). Active trading and retail investors in Malaysia. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 12(4), 708–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiril, K. O. S. S. E. V. (2020). OECD/INFE 2020 international survey of adult financial literacy. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Kock, N. (2015). Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. International Journal of e-Collaboration (IJEC), 11(4), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukacka, J., & Barunik, J. (2013). Behavioural breaks in the heterogeneous agent model: The impact of herding, overconfidence, and market sentiment. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications, 392(23), 5920–5938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S., & Goyal, N. (2015). Behavioural biases in investment decision making—A systematic literature review. Qualitative Research in Financial Markets, 7(1), 88–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. M., Lee, J., & Kim, K. T. (2020). Consumer financial well-being: Knowledge is not enough. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 41(2), 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. H., & Ma, W. (2024). The relationship between financial literacy misestimation and misplacement from the perspective of inverse differential information and stock market participation. International Journal of Financial Studies, 12(3), 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, P., & Guo, S. (2015). Social interaction, Internet access and stock market participation—An empirical study in China. Journal of Comparative Economics, 43(4), 883–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z., Wu, J., Li, H., & Galloway, B. (2024). Digital finance and stock market participation: The case of internet wealth management products in China. Economic Systems, 48(1), 101148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z., Azam, S. F., & Wang, L. (2023). Impact of financial literacy on household stock profit level in China. PLoS ONE, 18(12), e0296100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyngdoh, S. W., Das, S., & Das, T. (2025). Investment intentions and influential factors among university students. Choices, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, M. A., Qamar, M. A. J., Nazir, M. S., Ahmad, I., Timoshin, A., & Shehzad, K. (2020). How investors attitudes shape stock market participation in the presence of financial self-efficacy. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 553351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owen, M. A. (2020). Stock market development and economic growth: Empirical evidence from an institutional impaired economy. International Journal of Financial Research, 11(5), 496–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pak, O., & Mahmood, M. (2015). Impact of personality on risk tolerance and investment decisions: A study on potential investors of Kazakhstan. International Journal of Commerce and Management, 25(4), 370–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, D. X., & Lai, F. (2012). Using partial least squares in operations management research: A practical guideline and summary of past research. Journal of Operations Management, 30(6), 467–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P.H., H., & Uchil, R. (2020). Impact of investor sentiment on decision-making in Indian stock market: An empirical analysis. Journal of Advances in Management Research, 17(1), 66–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, M., Hussain, R., Mehboob, I., & Arshad, M. (2019). Impact of herding behavior and overconfidence bias on investors’ decision-making in Pakistan. Accounting, 5(2), 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., & Straub, D. W. (2012). Editor’s comments: A critical look at the use of PLS-SEM in” MIS Quarterly”. MIS Quarterly, 36, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, A., & Afaf, G. (2016). A comparison between psychological and economic factors affecting individual investor’s decision-making behavior. Cogent Business & Management, 3(1), 1232907. [Google Scholar]

- Shehata, S. M., Abdeljawad, A. M., Mazouz, L. A., Aldossary, L. Y. K., Alsaeed, M. Y., & Noureldin Sayed, M. (2021). The moderating role of perceived risks in the relationship between financial knowledge and the intention to invest in the Saudi Arabian stock market. International Journal of Financial Studies, 9(1), 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivaramakrishnan, S., Srivastava, M., & Rastogi, A. (2017). Attitudinal factors, financial literacy, and stock market participation. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 35(5), 818–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyrou, S. (2013). Herding in financial markets: A review of the literature. Review of Behavioral Finance, 5(2), 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulcanaza-Prieto, A. B., Cortez-Ordoñez, A., Rivera, J., & Lee, C. W. (2025). Is digital literacy a moderator variable in the relationship between financial literacy, financial inclusion, and financial well-being in the ecuadorian context? Sustainability, 17(6), 2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q., Liu, C., & Lan, S. (2023). Digital literacy and financial market participation of middle-aged and elderly adults in China. Economic and Political Studies, 11(4), 441–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W., Huang, V., Chen, X., Davison, R. M., & Hua, Z. (2018). Social value and online social shopping intention: The moderating role of experience. Information Technology & People, 31(3), 688–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J. J., & Porto, N. (2017). Financial education and financial satisfaction: Financial literacy, behavior, and capability as mediators. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 35(5), 805–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S., Yang, Z., Ali, S. T., Li, Y., & Cui, J. (2022). Does financial literacy affect household financial behavior? The role of limited attention. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 906153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M., Mamun, A. A., Mohiuddin, M., Al-Shami, S. S. A., & Zainol, N. R. (2021). Predicting stock market investment intention and behavior among Malaysian working adults using partial least squares structural equation modeling. Mathematics, 9(8), 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hypothesis No. | Hypothesis Statement | Expected Relationship |

|---|---|---|

| H1 | Digital Literacy positively influences Investment Intention. | Positive |

| H2 | Financial Literacy positively influences Investment Intention. | Positive |

| H3 | Risk Tolerance positively influences Investment Intention. | Positive |

| H4 | Financial Wellbeing positively influences Investment Intention. | Positive |

| H5 | Herding Behavior positively influences Investment Intention. | Positive |

| H6 | Overconfidence Bias positively influences Investment Intention. | Positive |

| H7 | Social Interactions positively influence Investment Intention. | Positive |

| H8 | Investment Intention positively influences Stock Market Participation. | Positive |

| H9 | Investment intention serves as a mediating factor, channeling the influence of all independent variables on stock market participation. | Mediating |

| n | % | n | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | Gender | ||||

| Andijan region | 5 | 1.4 | Female | 220 | 59.6 |

| Bukhara region | 8 | 2.2 | Male | 149 | 40.4 |

| Fergana region | 12 | 3.3 | Total | 369 | 100.0 |

| Jizzakh region | 45 | 12.2 | |||

| Kashkadarya region | 13 | 3.5 | Age group | ||

| Khorazm region | 10 | 2.7 | 17 to 27 | 353 | 95.6 |

| Namangan region | 3 | 0.8 | 28 to 37 | 13 | 3.5 |

| Navoi region | 5 | 1.4 | 38 to 47 | 3 | 0.8 |

| Republic of Karakalpakistan | 5 | 1.4 | Total | 369 | 100.0 |

| Samarkand region | 11 | 3.0 | |||

| Surkhandarya region | 1 | 0.3 | Financial literacy | ||

| Syrdarya region | 226 | 61.3 | Not Financially Literate | 328 | 89.0 |

| Tashkent city | 3 | 0.8 | Financially Literate | 41 | 11.0 |

| Tashkent region | 22 | 6.0 | Total | 369 | 100.0 |

| Total | 369 | 100.0 | |||

| Affilation | |||||

| Gulistan State Pedagogical Institute | 78 | 21.1 | |||

| Gulistan state university | 264 | 71.5 | |||

| National University of Uzbekistan | 10 | 2.7 | |||

| Yangiyer University of Chemical Technologies | 17 | 4.6 | |||

| Total | 369 | 100.0 |

| Variables | No. Items | Mean | SD | CA | CR | DG rho | AVE | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT | 5 | 3.010 | 1.303 | 0.839 | 0.885 | 0.862 | 0.606 | 2.070 |

| FW | 5 | 2.968 | 1.287 | 0.686 | 0.790 | 0.669 | 0.432 | 1.694 |

| DL | 19 | 3.654 | 1.372 | 0.969 | 0.971 | 0.977 | 0.642 | 3.347 |

| OB | 5 | 2.989 | 1.288 | 0.923 | 0.942 | 0.925 | 0.764 | 2.975 |

| HB | 5 | 2.864 | 1.204 | 0.872 | 0.908 | 0.874 | 0.664 | 2.483 |

| SI | 5 | 3.133 | 1.250 | 0.912 | 0.934 | 0.915 | 0.740 | 2.831 |

| INT | 4 | 2.492 | 1.289 | 0.862 | 0.906 | 0.868 | 0.708 | 2.575 |

| SMP | 5 | 2.360 | 1.305 | 0.878 | 0.911 | 0.889 | 0.674 | 2.272 |

| RT | 5 | 3.010 | 1.303 | 0.839 | 0.885 | 0.862 | 0.606 | 2.070 |

| DL | FW | HB | INT | OB | RT | SI | SMP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DL | 0.801 | |||||||

| FW | 0.485 | 0.657 | ||||||

| HB | 0.409 | 0.423 | 0.815 | |||||

| INT | 0.241 | 0.287 | 0.477 | 0.842 | ||||

| OB | 0.485 | 0.390 | 0.639 | 0.458 | 0.874 | |||

| RT | 0.517 | 0.441 | 0.361 | 0.455 | 0.418 | 0.779 | ||

| SI | 0.428 | 0.409 | 0.686 | 0.438 | 0.579 | 0.408 | 0.860 | |

| SMP | 0.221 | 0.232 | 0.460 | 0.615 | 0.424 | 0.360 | 0.496 | 0.821 |

| Code | DL | FW | HB | INT | OB | RT | SI | SMP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DL1 | 0.723 | 0.391 | 0.331 | 0.107 | 0.338 | 0.385 | 0.314 | 0.102 |

| DL11 | 0.787 | 0.385 | 0.303 | 0.157 | 0.381 | 0.409 | 0.332 | 0.122 |

| DL12 | 0.841 | 0.409 | 0.314 | 0.175 | 0.397 | 0.441 | 0.350 | 0.154 |

| DL14 | 0.851 | 0.435 | 0.327 | 0.099 | 0.392 | 0.457 | 0.317 | 0.118 |

| DL18 | 0.809 | 0.427 | 0.371 | 0.203 | 0.376 | 0.440 | 0.380 | 0.196 |

| DL19 | 0.734 | 0.325 | 0.277 | 0.201 | 0.372 | 0.311 | 0.311 | 0.203 |

| DL2 | 0.673 | 0.394 | 0.285 | 0.135 | 0.357 | 0.328 | 0.260 | 0.117 |

| DL20 | 0.778 | 0.308 | 0.328 | 0.257 | 0.451 | 0.371 | 0.358 | 0.231 |

| DL21 | 0.853 | 0.365 | 0.294 | 0.151 | 0.354 | 0.455 | 0.333 | 0.118 |

| DL24 | 0.864 | 0.397 | 0.325 | 0.192 | 0.357 | 0.451 | 0.364 | 0.196 |

| DL25 | 0.776 | 0.361 | 0.321 | 0.288 | 0.403 | 0.390 | 0.346 | 0.223 |

| DL26 | 0.855 | 0.405 | 0.338 | 0.194 | 0.418 | 0.441 | 0.342 | 0.162 |

| DL29 | 0.853 | 0.422 | 0.362 | 0.213 | 0.444 | 0.420 | 0.415 | 0.195 |

| DL3 | 0.674 | 0.410 | 0.308 | 0.189 | 0.378 | 0.399 | 0.292 | 0.203 |

| DL30 | 0.867 | 0.413 | 0.422 | 0.223 | 0.506 | 0.447 | 0.416 | 0.236 |

| DL4 | 0.846 | 0.421 | 0.344 | 0.144 | 0.353 | 0.473 | 0.348 | 0.168 |

| DL6 | 0.832 | 0.408 | 0.308 | 0.149 | 0.321 | 0.455 | 0.339 | 0.105 |

| DL7 | 0.761 | 0.346 | 0.298 | 0.180 | 0.337 | 0.396 | 0.295 | 0.151 |

| DL8 | 0.801 | 0.419 | 0.322 | 0.184 | 0.314 | 0.426 | 0.310 | 0.188 |

| FW1 | 0.579 | 0.596 | 0.443 | 0.238 | 0.447 | 0.476 | 0.460 | 0.234 |

| FW2 | 0.431 | 0.748 | 0.386 | 0.207 | 0.364 | 0.332 | 0.393 | 0.223 |

| FW3 | 0.112 | 0.599 | 0.124 | 0.154 | 0.114 | 0.136 | 0.094 | 0.050 |

| FW4 | 0.132 | 0.684 | 0.153 | 0.179 | 0.112 | 0.182 | 0.124 | 0.123 |

| FW5 | 0.137 | 0.646 | 0.135 | 0.111 | 0.073 | 0.193 | 0.097 | 0.031 |

| HB1 | 0.275 | 0.331 | 0.706 | 0.379 | 0.441 | 0.303 | 0.427 | 0.321 |

| HB2 | 0.455 | 0.360 | 0.778 | 0.440 | 0.647 | 0.402 | 0.586 | 0.435 |

| HB3 | 0.352 | 0.364 | 0.882 | 0.379 | 0.527 | 0.253 | 0.582 | 0.356 |

| HB4 | 0.307 | 0.345 | 0.862 | 0.381 | 0.491 | 0.272 | 0.590 | 0.363 |

| HB5 | 0.243 | 0.310 | 0.834 | 0.340 | 0.458 | 0.210 | 0.595 | 0.383 |

| INT1 | 0.077 | 0.178 | 0.363 | 0.770 | 0.321 | 0.267 | 0.336 | 0.521 |

| INT2 | 0.138 | 0.222 | 0.361 | 0.826 | 0.340 | 0.309 | 0.335 | 0.474 |

| INT3 | 0.279 | 0.262 | 0.424 | 0.892 | 0.436 | 0.455 | 0.404 | 0.544 |

| INT4 | 0.292 | 0.295 | 0.448 | 0.872 | 0.432 | 0.479 | 0.394 | 0.529 |

| OB1 | 0.397 | 0.313 | 0.567 | 0.413 | 0.865 | 0.343 | 0.511 | 0.375 |

| OB2 | 0.401 | 0.320 | 0.512 | 0.352 | 0.885 | 0.352 | 0.481 | 0.326 |

| OB3 | 0.414 | 0.375 | 0.534 | 0.386 | 0.851 | 0.355 | 0.484 | 0.352 |

| OB4 | 0.423 | 0.350 | 0.588 | 0.428 | 0.906 | 0.384 | 0.513 | 0.389 |

| OB5 | 0.479 | 0.344 | 0.581 | 0.412 | 0.863 | 0.390 | 0.535 | 0.401 |

| RT1 | 0.325 | 0.303 | 0.294 | 0.314 | 0.380 | 0.730 | 0.324 | 0.221 |

| RT2 | 0.405 | 0.349 | 0.326 | 0.389 | 0.402 | 0.831 | 0.365 | 0.300 |

| RT3 | 0.454 | 0.358 | 0.314 | 0.450 | 0.333 | 0.821 | 0.349 | 0.372 |

| RT4 | 0.396 | 0.369 | 0.234 | 0.256 | 0.251 | 0.726 | 0.311 | 0.216 |

| RT5 | 0.426 | 0.348 | 0.218 | 0.311 | 0.241 | 0.780 | 0.224 | 0.248 |

| SI1 | 0.413 | 0.359 | 0.595 | 0.347 | 0.518 | 0.395 | 0.854 | 0.427 |

| SI2 | 0.323 | 0.344 | 0.593 | 0.382 | 0.469 | 0.324 | 0.865 | 0.428 |

| SI3 | 0.350 | 0.382 | 0.590 | 0.345 | 0.481 | 0.319 | 0.874 | 0.405 |

| SI4 | 0.386 | 0.352 | 0.592 | 0.418 | 0.521 | 0.360 | 0.869 | 0.455 |

| SI5 | 0.370 | 0.325 | 0.580 | 0.384 | 0.499 | 0.354 | 0.837 | 0.413 |

| SMP1 | 0.094 | 0.140 | 0.357 | 0.388 | 0.270 | 0.155 | 0.395 | 0.716 |

| SMP2 | 0.202 | 0.171 | 0.367 | 0.552 | 0.365 | 0.352 | 0.409 | 0.866 |

| SMP3 | 0.298 | 0.246 | 0.429 | 0.549 | 0.431 | 0.396 | 0.468 | 0.850 |

| SMP4 | 0.019 | 0.134 | 0.317 | 0.480 | 0.245 | 0.146 | 0.335 | 0.807 |

| SMP5 | 0.258 | 0.245 | 0.416 | 0.533 | 0.403 | 0.378 | 0.428 | 0.855 |

| Hypo | Beta | CI-Min | CI-Max | t | p | r2 | f2 | Q2 | Decision | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Determinants of Stock Market Investment Intention | ||||||||||

| H1 | DL → INT | −0.149 | −0.261 | −0.031 | 2.535 | 0.011 | 0.449 | 0.034 | 0.317 | Accept |

| H2 | FL → INT | −0.048 | −0.140 | 0.045 | 1.002 | 0.316 | 0.004 | Reject | ||

| H3 | RT → INT | 0.335 | 0.226 | 0.447 | 5.884 | 0.000 | 0.187 | Accept | ||

| H4 | FW → INT | 0.003 | −0.127 | 0.134 | 0.044 | 0.965 | 0.002 | Reject | ||

| H5 | HB → INT | 0.227 | 0.065 | 0.375 | 2.897 | 0.004 | 0.053 | Accept | ||

| H6 | OB → INT | 0.183 | 0.049 | 0.313 | 2.723 | 0.006 | 0.053 | Accept | ||

| H7 | SI → INT | 0.113 | −0.034 | 0.268 | 1.464 | 0.143 | 0.004 | Reject | ||

| Determinants of Stock Market Participation | ||||||||||

| H8 | INT → SMP | 0.615 | 0.532 | 0.692 | 15.040 | 0.000 | 0.490 | 0.961 | 0.240 | Accept |

| Associations | Beta | CI-Min | CI-Max | t | p | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DL → INT → SMP | −0.092 | −0.161 | −0.019 | 2.504 | 0.012 | Accept |

| FL → INT → SMP | −0.029 | −0.087 | 0.029 | 1.000 | 0.318 | Reject |

| RT → INT → SMP | 0.206 | 0.136 | 0.284 | 5.430 | 0.000 | Accept |

| FW → INT → SMP | 0.002 | −0.079 | 0.082 | 0.044 | 0.965 | Reject |

| HB → INT → SMP | 0.140 | 0.040 | 0.235 | 2.834 | 0.005 | Accept |

| OB → INT → SMP | 0.113 | 0.029 | 0.195 | 2.678 | 0.007 | Accept |

| SI → INT → SMP | 0.069 | −0.020 | 0.169 | 1.435 | 0.151 | Reject |

| Female | Male | Difference | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | p-Value | Beta | p-Value | Beta | p-Value | Decision | |

| DL → INT | −0.104 | 0.157 | −0.187 | 0.072 | 0.083 | 0.498 | No Difference |

| FL → INT | −0.126 | 0.032 | 0.010 | 0.905 | −0.135 | 0.174 | No Difference |

| RT → INT | 0.403 | 0.000 | 0.250 | 0.003 | 0.153 | 0.176 | No Difference |

| FW → INT | −0.094 | 0.217 | 0.085 | 0.398 | −0.179 | 0.159 | No Difference |

| HB → INT | 0.234 | 0.023 | 0.242 | 0.023 | −0.008 | 0.965 | No Difference |

| OB → INT | 0.188 | 0.036 | 0.225 | 0.056 | −0.037 | 0.802 | No Difference |

| SI → INT | 0.084 | 0.379 | 0.112 | 0.365 | −0.028 | 0.866 | No Difference |

| INT → SMP | 0.517 | 0.000 | 0.706 | 0.000 | −0.189 | 0.015 | Sig. Difference |

| Economics Fields | Non Economics Fields | Difference | |||||

| Beta | p-value | Beta | p-value | Beta | p-value | Decision | |

| DL → INT | −0.164 | 0.171 | −0.092 | 0.263 | −0.072 | 0.566 | No Difference |

| FL → INT | −0.054 | 0.412 | −0.122 | 0.101 | 0.068 | 0.490 | No Difference |

| RT → INT | 0.198 | 0.011 | 0.383 | 0.000 | −0.185 | 0.104 | No Difference |

| FW → INT | 0.044 | 0.589 | −0.006 | 0.942 | 0.050 | 0.665 | No Difference |

| HB → INT | 0.218 | 0.008 | 0.228 | 0.092 | −0.010 | 0.926 | No Difference |

| OB → INT | 0.335 | 0.000 | −0.057 | 0.617 | 0.392 | 0.009 | Sig. Difference |

| SI → INT | 0.016 | 0.860 | 0.322 | 0.008 | −0.306 | 0.044 | Sig. Difference |

| INT → SMP | 0.628 | 0.000 | 0.579 | 0.000 | 0.049 | 0.574 | No Difference |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Eshpulatov, D.; Berdiev, G.; Artemenkov, A. Modeling the Determinants of Stock Market Investment Intention and Behavior Among Studying Adults: Evidence from University Students Using PLS-SEM. Int. J. Financial Stud. 2025, 13, 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs13030138

Eshpulatov D, Berdiev G, Artemenkov A. Modeling the Determinants of Stock Market Investment Intention and Behavior Among Studying Adults: Evidence from University Students Using PLS-SEM. International Journal of Financial Studies. 2025; 13(3):138. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs13030138

Chicago/Turabian StyleEshpulatov, Dostonbek, Gayrat Berdiev, and Andrey Artemenkov. 2025. "Modeling the Determinants of Stock Market Investment Intention and Behavior Among Studying Adults: Evidence from University Students Using PLS-SEM" International Journal of Financial Studies 13, no. 3: 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs13030138

APA StyleEshpulatov, D., Berdiev, G., & Artemenkov, A. (2025). Modeling the Determinants of Stock Market Investment Intention and Behavior Among Studying Adults: Evidence from University Students Using PLS-SEM. International Journal of Financial Studies, 13(3), 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs13030138