1. Introduction

The global pursuit of sustainable development has intensified amid escalating climate crises, persistent social inequalities, and evolving governance challenges. The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), established in 2015, provide a roadmap for integrating environmental, social, and governance principles into economic systems to foster inclusive and resilient societies (

Abdulkareem et al., 2025). Environmental, social, and governance readiness (ESGR), defined as a country’s capacity to implement sustainable practices across these dimensions, is a pivotal metric for assessing progress toward sustainability (

Alam et al., 2024;

Naseer & Bagh, 2024). Measured by the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative (ND-GAIN) country index’s readiness score, ESGR captures the economic, social, and governance capabilities essential for addressing global challenges. This study examines how financial inclusion (FIN), financial development (FDX), and technological innovation shape ESGR across low-income, lower-middle-income, and upper-middle-income countries from 2004 to 2020, offering novel insights into the interplay of financial and technological systems in sustainable development.

Sustainability disparities across income groups underscore the urgency of this research. High-income economies, with advanced financial and technological infrastructures, often exhibit higher ESGR, enabling investments in green technologies and social equity. Conversely, low-income and lower-middle-income countries face constraints such as limited financial access, underdeveloped markets, and inadequate technological capabilities, hindering their ability to address environmental and social challenges. Upper-middle-income countries, balancing rapid growth with sustainability, require integrated financial and technological strategies to scale ESG initiatives. Financial systems, serving as conduits for resource allocation and technological innovation, enabling efficient resource use, are pivotal in bridging these gaps. However, their combined impact on ESGR remains underexplored across diverse economic contexts.

Financial inclusion (FIN), defined as the accessibility of financial services to underserved populations, is a key driver of sustainable development (

Oanh, 2024). By enabling marginalised populations to access credit, savings, and insurance, FIN empowers communities to invest in education, healthcare, and environmentally friendly practices, directly contributing to the social and environmental pillars of ESGR (

Daud & Ahmad, 2023;

Suhrab et al., 2024;

Oanh & Dinh, 2024). For instance, microfinance in low-income countries enhances resilience to climate shocks, while digital banking in lower-middle-income countries expands access to rural communities (

Demirguc-Kunt et al., 2018;

Gallego-Losada et al., 2023). However, FIN’s impact varies across development stages: it fosters sustainability in less financially developed countries, but in more advanced systems, excessive credit may fuel energy-intensive consumption, undermining environmental goals (

Emara & El Said, 2021). This study examines these dynamics, exploring how FIN shapes ESGR across income groups.

Financial development, encompassing the depth, access, and efficiency of financial systems, influences sustainability by channelling capital towards productive uses. The IMF’s Financial Development Index (FDX) supports ESGR by facilitating investments in green bonds and renewable energy projects, particularly in upper-middle-income countries with sophisticated financial markets (

Sachs et al., 2019). Yet, in fossil fuel-dependent economies, FDX may exacerbate ecological degradation by enabling energy-intensive activities (

Huang et al., 2022). The interplay between FDX and ESGR, moderated by income levels and institutional factors, is a critical focus of this analysis, addressing gaps in prior studies that often overlook such heterogeneity (

Asongu & Odhiambo, 2020).

The theoretical framework integrates the environmental Kuznets curve (EKC) hypothesis, financial intermediation theory, and financial literacy theory. The EKC hypothesis posits an inverted U-shaped relationship between economic growth and environmental degradation, suggesting that financial systems can shift the curve by promoting green investments at higher income levels (

Grossman & Krueger, 1995). Financial intermediation theory (

Diamond, 1984) highlights FIN’s role in broadening access to capital, while financial literacy theory (

Ozili, 2022) underscores how informed financial decisions enhance sustainability. Further, institutional theory (

DiMaggio & Powell, 1983) complements these perspectives, emphasising the mediating role of regulatory quality and government effectiveness in shaping financial outcomes. By augmenting the EKC framework with FIN, FDX, and key control variables (GDP, URB, REQ, GOE), this study provides a robust lens for analysing sustainability drivers.

The focus on low-income, lower-middle-income, and upper-middle-income countries reflects their diverse economic, financial, and technological landscapes. Low-income countries, constrained by poverty and limited infrastructure, reveal FIN’s foundational role in early-stage sustainability. Lower-middle-income countries, undergoing rapid urbanisation, face trade-offs between growth and environmental preservation. Upper-middle-income countries, with advanced systems, highlight the scalability of ESG initiatives through technology-enabled finance. This stratification enables a nuanced analysis of context-specific dynamics, thus addressing a gap in aggregated analyses of developing economies (

Oanh, 2024).

This study’s significance lies in its academic and policy contributions. Academically, it extends the sustainable development literature by integrating financial systems and technological innovation into the EKC framework, using quantile regressions to uncover heterogeneous effects. Policy-wise, it advocates for technology-supported financial inclusion in low-income countries, green financing in upper-middle-income countries, and robust governance across all contexts, aligning with SDGs 8 (decent work and economic growth), 10 (reduced inequalities), and 13 (climate action). By linking finance, technology, and sustainability, the study addresses global challenges—including climate change, inequality, and governance deficits—offering a roadmap for resilient development.

The empirical approach employs a comprehensive set of econometric techniques, including panel and quantile regressions, to capture average and distributional effects. The analysis leverages data from diverse countries, drawing on established datasets for ESG readiness, financial inclusion, and financial development. Diagnostic tests, such as cointegration and unit root tests, ensure the robustness of the models, while tests for slope heterogeneity account for variations across income groups. The findings, presented through descriptive statistics, baseline regressions, and quantile regressions, reveal that financial inclusion and development positively influence ESG readiness, with effects varying by income level and ESG distribution. These results are visualised through figures that illustrate trends, relationships, and comparative outcomes, enhancing the interpretability of the findings.

The study also addresses pressing global challenges. Climate change, which disproportionately affects vulnerable populations, demands innovative financing mechanisms to support both adaptation and mitigation efforts. Social inequalities—exacerbated by limited access to financial services—require inclusive policies that empower marginalised communities. Governance failures, often rooted in weak regulatory systems, call for institutional reforms to promote accountability and transparency. By examining the role of financial inclusion and development in tackling these challenges, this study makes a timely contribution to the global sustainability agenda.

In conclusion, this paper investigates the relationship between financial inclusion, financial development, and ESG readiness across low-income, lower-middle-income, and upper-middle-income countries. It provides a comprehensive understanding of how financial systems can support sustainable development by integrating theoretical frameworks, rigorous econometric methods, and context-specific analyses. The findings highlight the transformative potential of financial inclusion and development, while underscoring the importance of economic resources, urbanisation, and governance quality.

The rest of the paper Is structured as follows:

Section 2 reviews the relevant literature and theoretical frameworks;

Section 3 outlines the data and methodology;

Section 4 presents the results and discusses the findings in relation to existing studies; and

Section 5 concludes the paper.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data and Sample

This study employs a panel data framework to investigate the relationships among financial inclusion (FIN), financial development (FDX), and environmental, social, and governance (ESG) readiness across low-income, lower-middle-income, and upper-middle-income countries over the period from 2004 to 2020. The sample comprises the following countries.

Low-income countries: Burkina Faso, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Mali, Mozambique, Rwanda, and Uganda.

Lower-middle-income countries: Bangladesh, Bhutan, Bolivia, Cambodia, Cameroon, Egypt, Ghana, Honduras, India, Jordan, Kenya, Lao PDR, Lesotho, Morocco, Nepal, Nicaragua, Pakistan, Philippines, Senegal, Tajikistan, Tanzania, Tunisia, Vietnam, and Zambia.

Upper-middle-income countries: Argentina, Armenia, Brazil, China, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Georgia, Indonesia, Mexico, Mongolia, Peru, South Africa, Thailand, and Türkiye.

3.2. Study Variables

This study utilises a panel data framework to examine the relationship between financial inclusion (FIN), financial development (FDX), and ESG readiness across low-income, lower-middle-income, and upper-middle-income countries from 2004 to 2020. The model includes four control variables—gross domestic product (GDP), urbanisation (URB), regulatory quality (REQ), and government effectiveness (GOE)—to account for potential confounding factors affecting ESG readiness. This section outlines the dependent, independent, and control variables, detailing their definitions, measurement approaches, data sources, and theoretical significance.

3.2.1. Dependent Variable: ESG Readiness (ESGR)

In this study, ESG readiness is defined as a country’s capacity to attract investment and implement adaptation measures that strengthen resilience to climate change and other global challenges, encompassing environmental, social, and governance dimensions. It is measured using the readiness score from the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative (ND-GAIN) country index, which aggregates nine indicators across three key components: economic readiness (the ability to attract and utilise investment for adaptation), governance readiness (institutional capacity to support effective investment), and social readiness (including factors such as social inequality, education, and ICT infrastructure that facilitate adaptive actions). The original readiness score ranges from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating greater readiness; for interpretability, it is rescaled to a 0–100 scale, following established practices in climate adaptation research (

Alam et al., 2024;

Naseer & Bagh, 2024). The ND-GAIN readiness score is chosen for its comprehensive alignment with ESG principles and its suitability for cross-country sustainability assessments.

3.2.2. Independent Variables

Financial inclusion (FIN) refers to the accessibility and availability of financial services—such as banking, credit, and insurance—for individuals and businesses, especially within underserved populations. In this study, FIN is constructed as a composite index using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) based on six key indicators: (1) number of commercial bank branches per 1000 km

2, (2) number of ATMs per 1000 km

2, (3) total number of ATMs, (4) number of commercial bank branches per 100,000 adults, (5) outstanding loans from commercial banks (% of GDP), and (6) outstanding deposits at commercial banks (% of GDP). These indicators reflect both the physical infrastructure and the utilisation of financial services, offering a multidimensional perspective on financial inclusion. The resulting PCA-based index is standardised, with higher scores indicating greater financial inclusion. Data are sourced from the International Monetary Fund’s Financial Access Survey (FAS). This composite approach is supported by the literature emphasising that no single metric adequately captures the complexity of financial inclusion (

Oanh, 2024). Theoretically, enhanced financial inclusion is expected to promote ESG readiness by facilitating access to finance for sustainable investments, such as green technologies and social initiatives, consistent with financial inclusion theory (

Demirguc-Kunt et al., 2018).

Financial development (FDX) represents the depth, efficiency, and stability of a country’s financial system, including its banking sector, capital markets, and financial institutions. It is measured using the IMF’s financial development index, which aggregates indicators such as domestic credit to the private sector (% of GDP), stock market capitalisation, and banking sector efficiency. The index is scaled from 0 to 1, with higher values reflecting more advanced financial systems. Financial development is theorised to support ESG readiness by mobilising capital toward environmentally sustainable and socially responsible enterprises, aligning with the financial development hypothesis (

Sachs et al., 2019). This variable is particularly significant for upper-middle-income countries, where mature financial systems are better positioned to drive sustainability agendas.

3.2.3. Control Variables

To isolate the effects of financial inclusion (FIN) and financial development (FDX) on ESG readiness, the model incorporates four control variables that capture key economic, structural, and institutional determinants. GDP per capita (in constant 2015 US dollars) reflects the overall economic output and resource capacity of a country to support sustainability-related investments. This variable is sourced from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators (WDI).

Urbanisation represents the percentage of the population living in urban areas, also obtained from the WDI. It influences ESG readiness through its impact on infrastructure demands, environmental stress, and social dynamics. Regulatory quality is measured using the Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI), assessing a government’s ability to formulate and implement sound policies conducive to private sector development. Scores range from −2.5 (weak) to 2.5 (strong). Government effectiveness, also from the WGI, captures the quality of public services, policy implementation capacity, and institutional credibility. Like regulatory quality, its scores range from −2.5 to 2.5, with higher values indicating more effective governance.

3.3. Model Setting

3.3.1. Cross-Sectional Dependence

Panel data analysis assumes that error terms

are independent across cross-sectional units. However, studies highlight that cross-sectional dependence is common in panel datasets due to global economic interdependence or unobserved common factors. (

Chudik & Pesaran, 2015;

Sarafidis & Wansbeek, 2012). Ignoring such dependence can lead to inefficient estimators and unreliable results. To address this, we apply a series of cross-sectional dependence tests, including the Lagrange Multiplier (LM) test (

Breusch & Pagan, 1980), the Scaled LM test, the CD test (

Pesaran, 2021), and the Bias-Corrected Scaled LM test (

Baltagi et al., 2012). These diagnostics help validate the robustness of our econometric approach.

3.3.2. Stationarity Properties and Cointegration Tests

To assess the stationarity properties of the panel data, we employ the Cross-sectional Augmented Im-Pesaran-Shin (CIPS) unit root test developed by

Pesaran (

2007). Unlike first-generation tests, the CIPS test accounts for cross-sectional dependence, making it more suitable for balanced panel datasets. The test is derived from the Cross-sectional Augmented Dickey–Fuller (CADF) regression and provides reliable results under the presence of global interdependencies.

where

is the cross-sectional average of the variable at time t, and p denotes the lag order. The CIPS statistic is computed as the average of the CADF test statistics across all cross-sectional units.

The CIPS test results guide the assessment of variable integration levels, a prerequisite for cointegration analysis. Given the potential for cross-sectional dependence and varying integration orders, we employ second-generation cointegration tests to explore long-run relationships among ESG, FIN, FDX, and the control variables. Specifically, we use the tests proposed by

Kao (

1999),

Pedroni (

1999);

Pedroni (

2004), and

Westerlund (

2008), which are designed to handle cross-sectional dependence. These tests evaluate the null hypothesis of no cointegration against the alternative of cointegration, ensuring the validity of long-run analysis.

3.3.3. Regression Analysis

Following the diagnostic tests, the study estimates the model using a combination of Ordinary Least Squares (OLS), Fixed Effects (FE), and Method of Moments Quantile Regression (MMQR). OLS provides baseline estimates, while FE accounts for unobserved country-specific heterogeneity. MMQR, as introduced by

Machado and Santos (

2019), captures the heterogeneous effects of FIN and FDX across the conditional distribution of ESG readiness, offering insights into how financial variables influence countries at different levels of sustainability performance. This multi-method approach enhances the robustness and comprehensiveness of the findings, addressing both average effects and distributional dynamics. The baseline model is specified as follows:

where

represents ESG readiness for country I at time t,

and

denote financial inclusion and financial development, respectively, and

include GDP, urbanisation (URB), regulatory quality index (REQ), and government effectiveness (GOE). The term

is the error term.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

As presented in

Table 1, the descriptive statistics provide an overview of the variables across the sampled countries. ESG readiness exhibits varying levels across income groups. Upper-middle-income countries show higher mean values than low-income and lower-middle-income countries, reflecting greater institutional and resource capacities. FIN and FDX also demonstrate heterogeneity, with upper-middle-income countries reporting higher access to financial services and more developed financial systems. The control variables GDP, URB, REQ, and GOE further highlight structural differences, with low-income countries exhibiting lower urbanisation and governance quality.

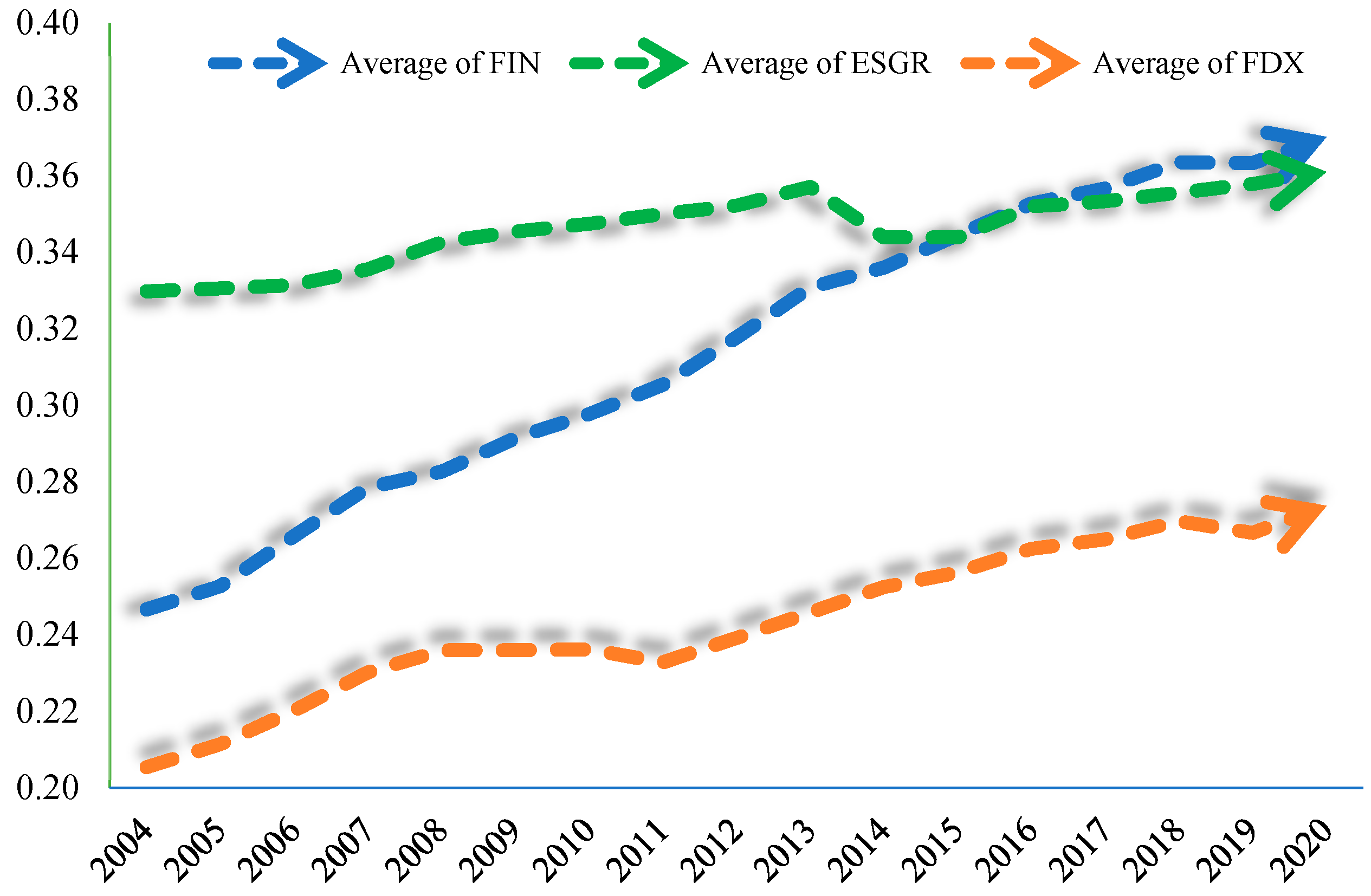

4.2. Trend Analysis

Figure 1 depicts time-series trends in ESGR, FIN, and FDX across low-income, lower-middle-income, and upper-middle-income countries. From 2004 to 2020, all three indices showed positive growth, with FIN demonstrating the strongest improvement from 0.25 to 0.37 (48% increase), followed by FDX rising from 0.205 to 0.274 (33.7% increase), while ESGR showed the most modest growth from 0.33 to 0.36 (9% increase). This consistent upward trend across all metrics suggests a global movement toward more inclusive and sustainable financial systems, with financial inclusion making particularly significant strides over this 16-year period.

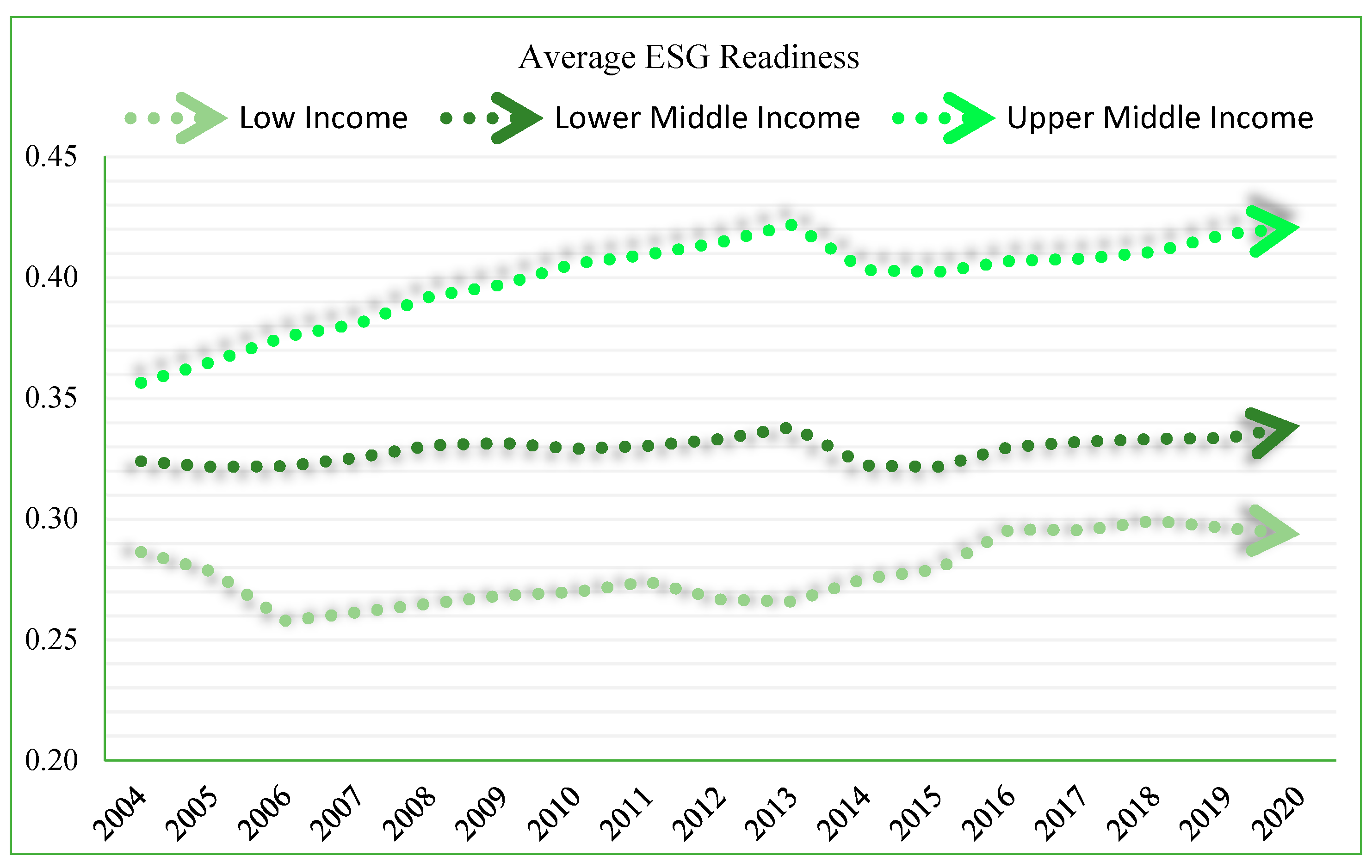

Figure 2 illustrates the ESG readiness across different income groups from 2004 to 2020, revealing persistent disparities. Upper-middle-income countries maintained the highest ESGR scores, improving from 0.356 to 0.421 (18.3% increase), while lower-middle-income countries showed minimal growth from 0.324 to 0.339 (4.6% increase), and low-income countries experienced the smallest improvement from 0.286 to 0.293 (2.4% increase). The widening gap between income groups suggests that wealthier nations are advancing their environmental, social, and governance frameworks more rapidly than their lower-income counterparts.

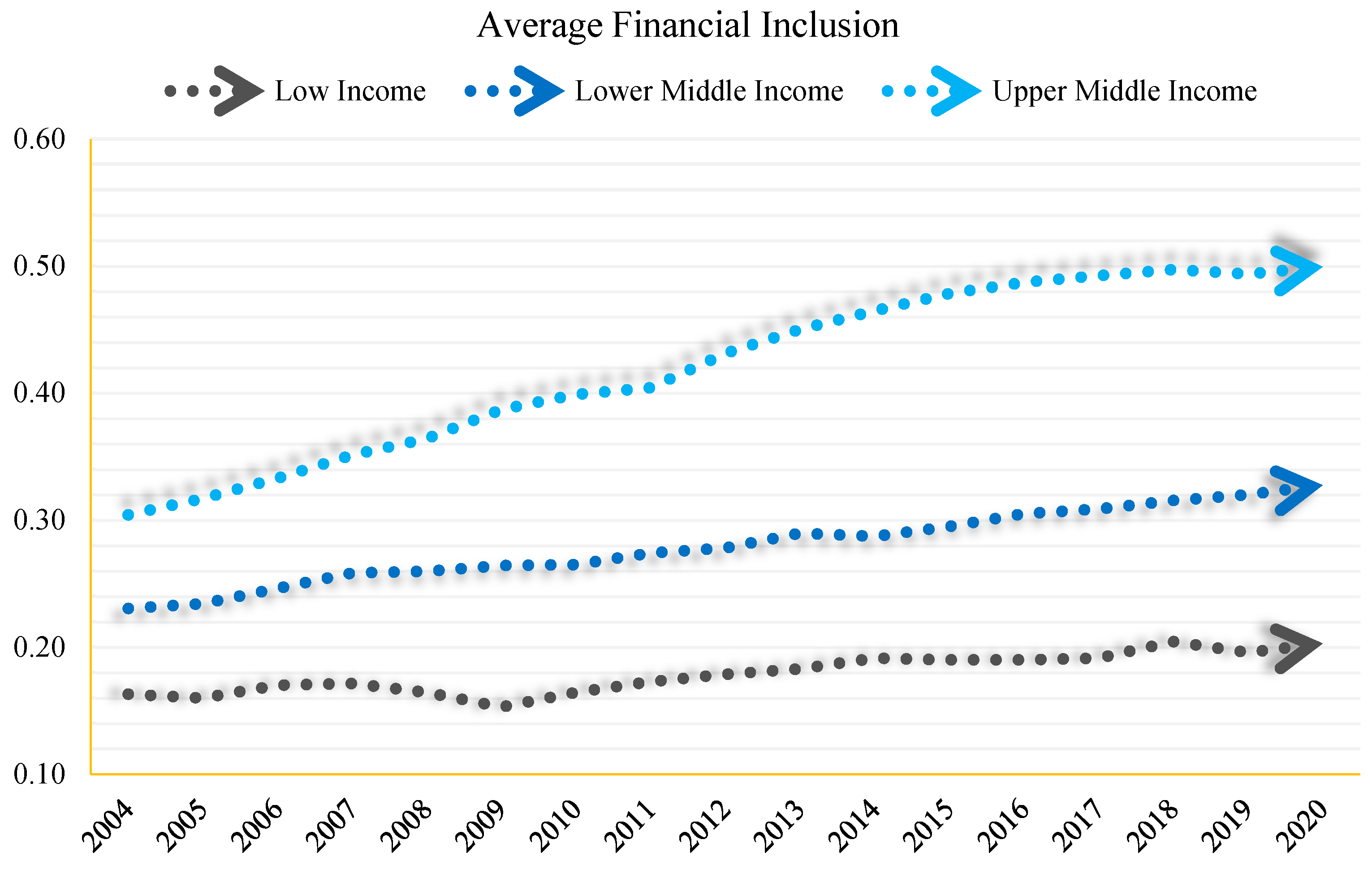

Financial inclusion varies significantly by income level as shown in

Figure 3, with all groups showing improvement from 2004 to 2020 but at markedly different rates. Upper-middle-income countries experienced the most dramatic increase in FII from 0.304 to 0.499 (64.1% increase), compared to lower-middle-income countries’ growth from 0.230 to 0.328 (42.6% increase) and low-income countries’ more modest improvement from 0.163 to 0.203 (24.5% increase). These trends indicate that while financial inclusion is improving globally, higher-income economies are advancing more rapidly, potentially creating a widening financial inclusion gap.

Figure 4 demonstrates the evolution of financial development across income groups from 2004 to 2020, highlighting significant inequalities. Upper-middle-income countries showed robust FDX growth from 0.27 to 0.40 (48.1% increase), while lower-middle-income and low-income countries experienced more modest improvements from 0.19 to 0.23 (21.1% increase) and 0.09 to 0.11 (22.2% increase), respectively. The persistent and widening gap between income groups suggests that financial markets and institutions are developing at significantly different rates, with wealthier nations enjoying more sophisticated and robust financial systems.

4.3. Diagnostic Tests

4.3.1. Pairwise Correlations

Table 2 reports the pairwise correlations among the variables. A positive and significant correlation is observed between ESGR and both FIN and FDX, suggesting that financial inclusion and development are associated with higher ESG readiness. The correlations between ESGR and the control variables (GDP, URB, REQ, and GOE) are also positive, indicating that economic growth, urbanisation, and governance quality may enhance sustainability outcomes. Notably, no evidence of multicollinearity is detected, as correlation coefficients remain below the critical threshold of 0.8 (

Kennedy, 2008).

4.3.2. Cointegration and Stationarity

Table 3 shows the cointegration test results, confirming a long-run relationship between ESGR, FIN, and FDX across all income groups. This finding supports the application of panel regression techniques.

The panel unit root tests (

Table 4) reveal that all variables become stationary after first differencing, confirming the suitability of the data for regression analysis. These findings align with established practices in panel data analysis within sustainability research (

Pedroni, 1999).

4.3.3. Slope Heterogeneity

The test for slope heterogeneity (

Table 5) reveals significant differences in the relationships across income groups. This heterogeneity justifies the use of quantile regression to capture varying effects at different levels of ESG readiness and supports the stratification of countries by income level, as suggested by (

Asongu & Odhiambo, 2020).

4.4. Baseline Regression Results

Table 6 presents the baseline panel regression results, analysing the effects of financial inclusion (FIN) and financial development (FDX) on ESG readiness, while controlling for GDP, URB, REQ, and GOE. The findings reveal that FIN and FDX exhibit positive and statistically significant coefficients across all income groups, indicating their pivotal roles as drivers of ESG readiness. These results provide empirical support for Hypothesis 1 and Hypothesis 2. Additionally, the control variables demonstrate significant influence. GDP positively affects ESG readiness, highlighting the critical role of economic resources in advancing sustainability initiatives. Similarly, REQ and GOE exhibit positive and statistically significant effects, emphasising the importance of institutional quality in facilitating ESG outcomes.

Several studies align with the positive impact of FIN and FDX on ESG readiness, particularly in the environmental dimension.

Oanh (

2024) and

Oanh and Dinh (

2024) demonstrate that access to financial services enables firms to invest in green technologies, thereby reducing their environmental footprint. Similarly,

Qin et al. (

2021) find that financial inclusion facilitates investments in sustainable technologies, enhancing environmental performance across various contexts. These findings support the positive coefficients of FIN and FDX in driving ESG readiness, particularly by enabling access to capital for environmentally focused initiatives. In contrast,

Zaidi et al. (

2021) present evidence that financial inclusion may increase economic activity that leads to higher CO2 emissions, particularly in developing economies, suggesting a potential trade-off where FIN supports economic growth but negatively impacts environmental sustainability.

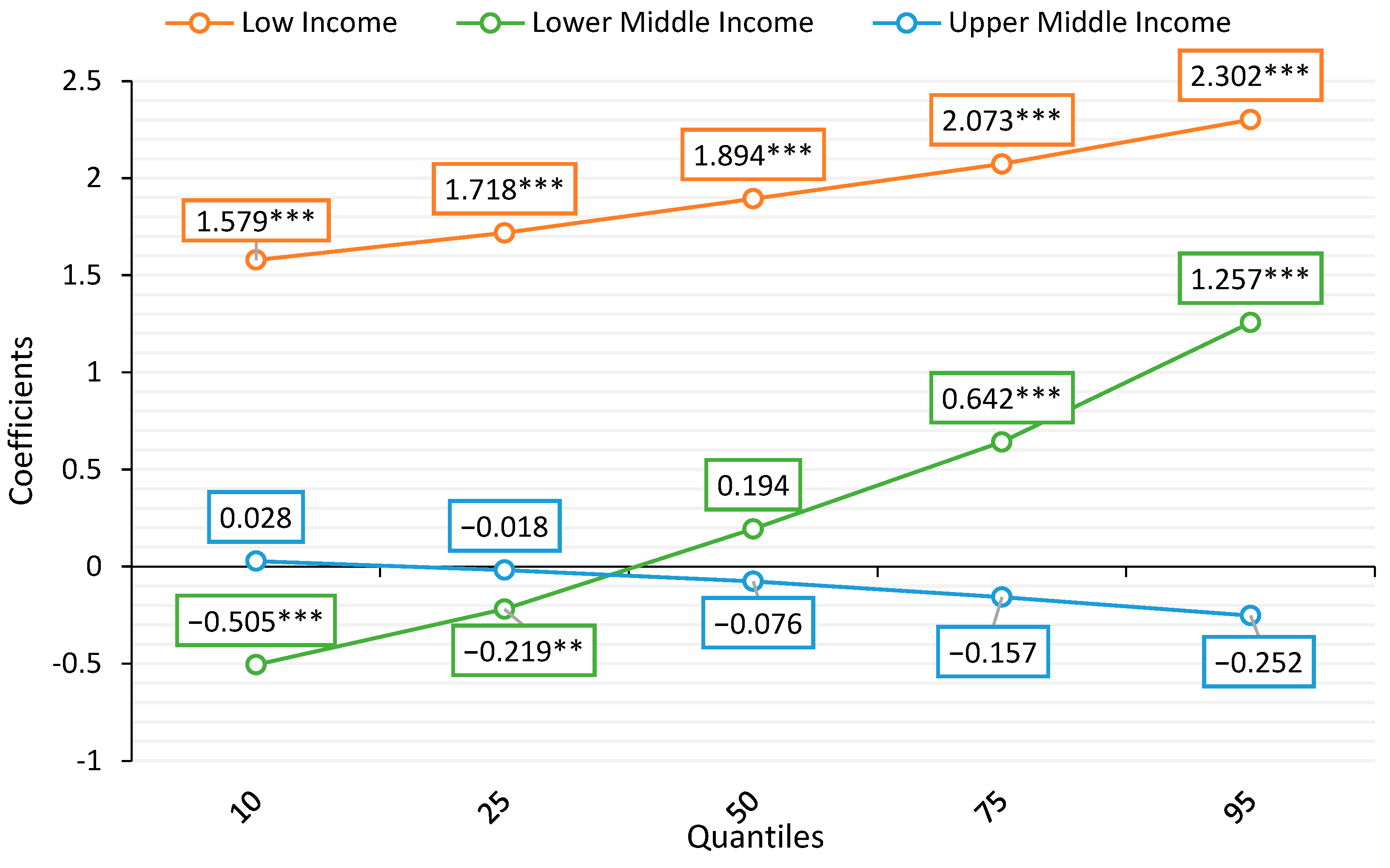

4.5. Quantile Regression Results

To explore the heterogeneous effects of FIN and FDX across the distribution of ESG readiness, quantile regression results are presented in

Table 7. FIN has a significant negative coefficient at lower quantiles (e.g., 10th and 25th), indicating that at the lowest quantile, increased financial inclusion is associated with a decrease in ESG readiness. This suggests that at lower levels of ESG readiness, financial inclusion may be less effective or even detrimental. Conversely, the effect of FIN is more pronounced at higher quantiles (e.g., 75th and 90th), indicating that financial inclusion benefits countries with already established ESG systems. FDX exhibits consistently positive and statistically significant effects across all quantiles, though the magnitude of the effect increases with the quantiles. Starting from a smaller effect at the 10th quantile (0.016, insignificant) and moving to a more pronounced effect by the 95th quantile (0.169 *** significant at 1% level). This pattern suggests that financial development universally supports ESG readiness, with its influence becoming stronger as performance improves.

4.6. Results Across Low-, Lower-Middle- and Upper-Middle-Income Countries

Table 8 presents the regression results examining the effects of financial inclusion (FIN) and financial development (FDX) on ESG readiness across three income groups: low-income, lower-middle-income, and upper-middle-income countries. These disaggregated results provide nuanced insights into how financial mechanisms influence ESG outcomes within varying economic contexts.

For low-income countries, FIN exhibits a highly significant and positive impact on ESG readiness. This finding suggests that even modest improvements in access to financial services can yield substantial benefits for environmental, social, and governance outcomes in resource-constrained settings. Similarly, the coefficient for FDX is also positive and statistically significant, indicating that financial system development strongly supports ESG initiatives by mobilising resources and enhancing institutional capacity.

In lower-middle-income countries, the effect of FIN on ESG readiness remains positive but is less pronounced compared to low-income countries. This implies that while financial inclusion continues to contribute to ESG improvements, its marginal impact diminishes as income levels rise. The coefficient for FDX in lower-middle-income countries remains positive and highly significant (0.100 ***), confirming the continued importance of financial development in advancing ESG readiness, though with a slightly reduced magnitude relative to the lowest-income group.

These findings underscore the differentiated roles of financial inclusion and development across income groups, highlighting the critical importance of tailored financial policies to promote ESG objectives in diverse economic contexts.

The FIN coefficient in upper-middle-income countries is negative but statistically insignificant. This suggests that in upper-middle-income countries, the relationship between financial inclusion and ESG readiness might be negligible or even slightly negative, indicating a potential saturation or different dynamics at play where basic financial inclusion is no longer a driving factor for ESG improvements. The FDX coefficient is 0.037 *, showing a positive yet modest impact. This implies that while financial development still supports ESG readiness, its influence is considerably less impactful in more economically developed contexts compared to lower-income groups.

Economic theories posit that financial markets and institutions play a critical role in facilitating economic growth by mobilising savings, allocating resources efficiently, and diversifying risks. These functions are pivotal in supporting ESG initiatives, as they provide the necessary capital and risk management to invest in sustainable projects. Financial inclusion is fundamentally linked to the concept of inclusive growth, which ensures that all segments of society benefit from economic growth. Theoretically, as more individuals and businesses access financial services (banking, loans, insurance), they can better manage risks and invest in opportunities that enhance sustainability. As societies modernise, they tend to adopt more sophisticated governance practices, which include better management of environmental and social issues. Financial development is a part of this modernisation process, enhancing the capacity of firms and governments to invest in ESG initiatives. In higher-income countries, modernisation includes the adoption of advanced technologies, which might explain the diminishing marginal returns of financial inclusion on ESG readiness; as these societies have already achieved higher levels of technological and financial maturity, the additional benefits of increased financial inclusion are less impactful.

4.7. FIN Coefficients by Income Groups and Quantiles

Figure 5 provides the coefficients of FIN across different income groups (low-, lower-middle-, and upper-middle-income) at various quantiles (10, 25, 50, 75, 95). This graphical representation allows for a nuanced interpretation of how financial inclusion impacts different segments of economies based on their level of income and across varying degrees of performance metrics (as measured by quantiles).

In the low-income group, the coefficient of financial inclusion on ESG readiness increases significantly across quantiles. At the 10th quantile, the effect starts positively (1.579 ***), suggesting that even at lower performance levels, financial inclusion significantly benefits ESG readiness. This positive impact grows stronger with each quantile, culminating in a high of 2.302 *** at the 95th quantile. This pattern indicates that in low-income settings, as entities (like firms or economies) improve their performance or scale, the benefits derived from financial inclusion scale up substantially, possibly indicating that financial inclusion is crucial for all-around development in these economies.

In the lower-middle-income group, financial inclusion shows a mixed impact. Starting with a significant negative impact at the 10th quantile (−0.505 ***), it suggests that at lower performance levels, financial inclusion might be ineffective or misaligned with the needs of entities. The coefficient becomes less negative and loses significance at the 25th quantile (−0.219 **) and shifts to a non-significant positive impact by the 50th quantile. By the 75th quantile, the impact turns clearly positive and significant (0.642 ***), which strengthens further at the 95th quantile (1.257 ***). This suggests a turnaround point where beyond a certain level of performance, financial inclusion starts benefiting entities within lower-middle-income settings, possibly due to better integration of financial services with their operational and strategic frameworks.

For the upper-middle-income group, financial inclusion generally exhibits a non-significant and minimal impact across most quantiles. The coefficients range from slightly negative (−0.157) to slightly positive (0.194), but none are significant until the 75th quantile, where a modest positive, yet non-significant effect is noted. This pattern may indicate that in upper-middle-income environments, the baseline level of financial inclusion is already such that additional inclusion does not yield significant marginal benefits, or other factors may be more influential in driving ESG readiness.

The graph starkly illustrates how the effectiveness of financial inclusion as a tool for improving ESG readiness varies notably across different income groups and performance levels. For low-income countries, enhancing financial inclusion across the board appears beneficial. In contrast, for lower and upper-middle-income countries, targeted approaches might be necessary, focusing on improving financial inclusion where it is most effective, likely at higher quantiles where entities are better positioned to leverage such inclusion.

Figure 6 provides the coefficients of the FDX across different quantiles (10, 25, 50, 75, 95) for three different income groups: low-income, lower-middle-income, and upper-middle-income.

4.8. FDX Coefficients by Income Groups and Quantiles

The plot shows a positive trend in the impact of financial development on the dependent variable across quantiles in the low-income group. The coefficients increase from 0.594 at the 10th quantile to 1.028 at the 95th quantile, all significant at the *** level. This suggests that in low-income settings, enhancements in financial development are strongly correlated with improvements in ESG readiness, with the influence becoming stronger at higher performance levels.

The FDX coefficients in the lower-middle-income group show less consistency and are generally lower compared to the low-income group. The values start from 0.096 at the 10th quantile (significant at *), dip to 0.018 at the 25th quantile (not significant), and increase again to 0.084 at the 95th quantile. Financial development appears to have a varied but overall positive impact on ESG readiness in lower-middle-income economies. The fluctuating significance may indicate other intervening variables at different levels of development that moderate the effect of financial development.

In upper-middle-income FDX shows consistently moderate coefficients across quantiles, ranging from 0.005 at the 10th quantile (not significant) to 0.057 at the 75th quantile. The coefficient at the 95th quantile is 0.084. In upper-middle-income countries, financial development continues to positively impact the dependent variable, though the effect size is smaller than in lower-income groups. This may suggest a diminishing marginal benefit of financial development at higher income levels, possibly due to already established financial systems and infrastructures.

The visual depiction underscores a scaling effect of financial development across income groups, where the impact is most pronounced in low-income countries and tends to diminish in intensity as income levels rise. These results could be particularly insightful for policymakers and development strategists focusing on tailored financial policies. For instance, aggressively promoting financial development may yield significant gains in low-income regions while requiring more nuanced approaches in upper-middle-income settings where the existing financial infrastructure may need different kinds of enhancements. This observation supports theories suggesting that financial development can catalyse economic and social advancements, particularly where there is room for significant improvement. In more developed settings, the focus might shift towards optimising and innovating within existing frameworks rather than expanding access or capacity.

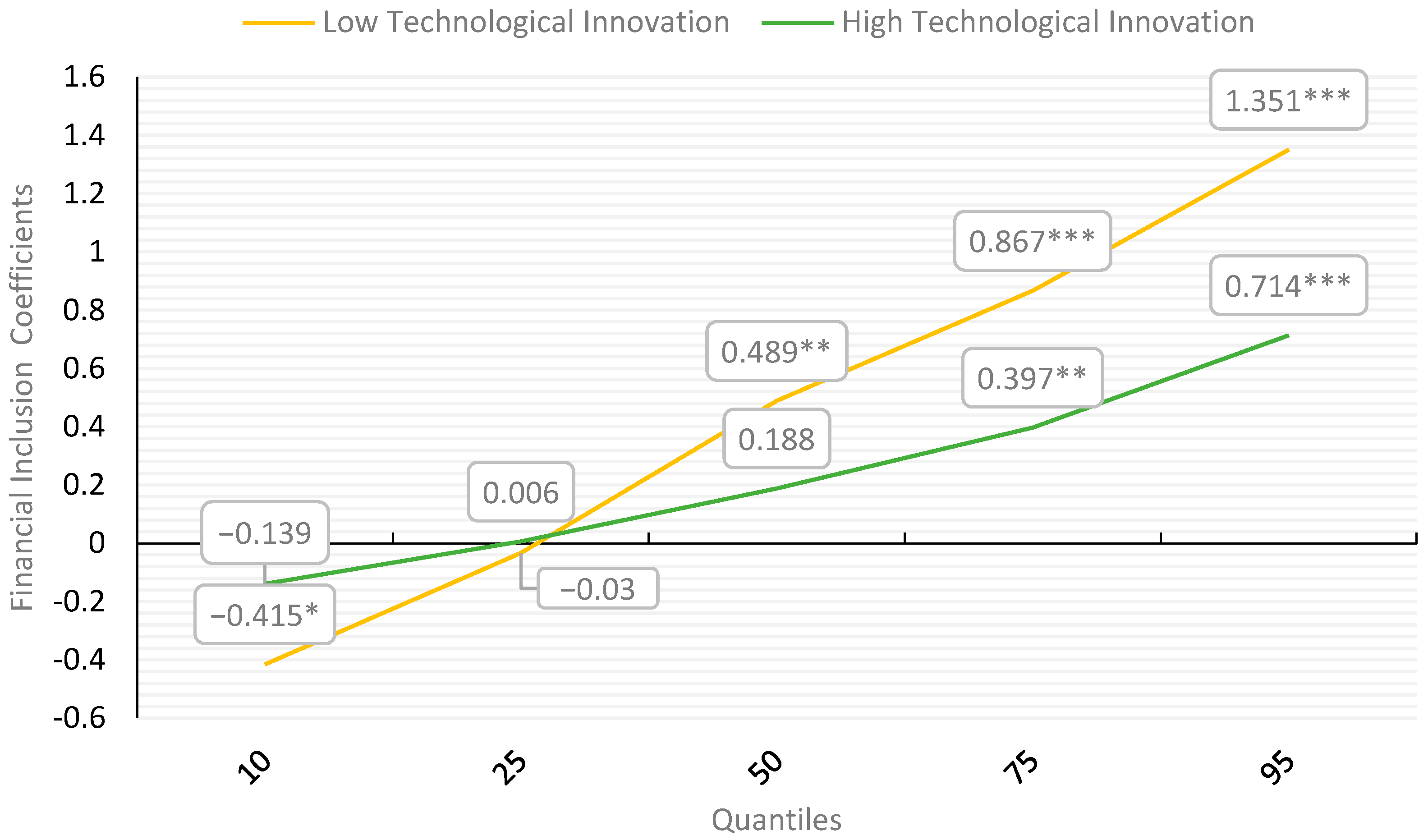

4.9. Role of Technological Innovation

In

Figure 7 the negative impact of FIN at the 10th quantile (−0.415 *) suggests that in contexts of low technological innovation, initial increases in financial inclusion might not contribute to or could even hinder ESG readiness. This could be due to inadequate technological infrastructure to leverage financial inclusivity effectively. The positive coefficients at higher quantiles (especially at 75th and 95th with significant levels) indicate that as ESG readiness improves, the benefits of financial inclusion become apparent. This shift could reflect a threshold beyond which financial inclusion starts to support or enhance ESG initiatives effectively. The insignificance at lower quantiles and significance at higher quantiles (75th and 95th) in high innovation settings implies that financial inclusion contributes to ESG readiness primarily at higher levels. In environments with high technological innovation, the infrastructure likely exists to harness the benefits of financial inclusion more effectively at advanced stages.

In

Figure 8 the increasing significance and coefficients of FDX from the 50th quantile onward indicate a robust positive influence on ESG readiness. This suggests that financial development plays a critical role in enhancing ESG readiness in less technologically advanced environments, potentially by providing better financial tools and resources that facilitate ESG activities. FDX shows a consistently positive and significant impact across all quantiles in high innovation contexts, reinforcing the notion that financial development supports ESG readiness. The technological backdrop here may allow for more efficient and effective utilisation of financial resources, enhancing their impact on ESG readiness from the ground up.

The variable impact of financial inclusion across different contexts underscores the importance of the underlying technological environment in determining how effectively financial tools and services contribute to ESG readiness. The results suggest that merely increasing financial inclusion is not sufficient; the technological and financial infrastructure must also be capable of supporting these efforts. Conversely, financial development consistently supports ESG readiness, particularly when paired with high technological capabilities, suggesting that investment in both finance and technology infrastructure is crucial for enhancing ESG outcomes.

5. Conclusions

This study examines the impact of FIN and FDX on ESG readiness across low-income, lower-middle-income, and upper-middle-income countries from 2004 to 2020. The study’s focus on these income groups reveals distinct dynamics between FIN’s foundational role in low-income countries, trade-offs between growth and environmental preservation in lower-middle-income countries, and the scalability of ESG initiatives in upper-middle-income countries. By employing advanced econometric techniques, including panel and quantile regressions, and leveraging robust datasets, the study addresses pressing global challenges like climate change, social inequalities, and governance failures, offering timely insights into innovative financing mechanisms and inclusive policies that advance the global sustainability agenda.

The findings confirm that FIN and FDX significantly enhance ESG readiness, with stronger effects in less financially developed countries. However, in upper-middle-income countries, increased energy-intensive consumption moderates these gains, underscoring the complex interplay between financial systems and sustainability. A key contribution of this study is its exploration of technological innovation’s moderating role. At lower quantiles, FIN exhibits a negative impact in low-innovation contexts, suggesting that inadequate technological infrastructure hinders FIN’s contribution to ESG readiness. Conversely, significant positive effects at higher quantiles in high-innovation settings indicate that robust technological capabilities amplify FIN’s benefits, enabling effective ESG initiatives. FDX, however, shows a consistently positive impact across all quantiles, highlighting its critical role in leveraging financial resources for sustainability. These findings extend the literature by integrating technological innovation into the EKC framework, revealing threshold effects that prior studies often overlook.

The study’s policy implications are profound for achieving the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly Goals 8 (economic growth), 10 (reduced inequalities), and 13 (climate action). In low-income countries, policymakers should prioritise financial inclusion through microfinance and digital platforms, coupled with investments in technological infrastructure to overcome initial barriers to ESG readiness. In upper-middle-income countries, redirecting credit toward green financing and renewable energy, supported by advanced technologies, can mitigate environmental trade-offs. Strengthening regulatory quality and government effectiveness is essential across all contexts to ensure financial and technological interventions align with sustainability objectives.

Limitations include the ND-GAIN readiness score’s aggregation, which may obscure sector-specific ESGR dynamics, and the PCA-based FIN index’s potential underrepresentation of emerging digital financial trends. The exclusion of high-income countries limits generalizability. Future research could disaggregate ESG components, incorporate digital financial inclusion metrics (e.g., mobile money), and extend the analysis to high-income countries. Investigating the interplay of technological innovation and renewable energy adoption could further clarify pathways to ESG readiness. Other limitations incude the study’s focus on group-level characteristics which may not fully capture country-specific variations, such as unique economic, political, or cultural factors influencing ESG readiness within each income group. In conclusion, this study underscores the pivotal role of financial inclusion and development in driving ESG readiness, moderated by technological innovation. By offering nuanced insights into context-specific dynamics, it provides a roadmap for harnessing financial and technological systems to advance global sustainability.