Abstract

(1) Background: The survival and growth of startups in their early stages are negatively impacted by the lack of financial sustainability and scarce resources that entrepreneurs face during the first 5 years. This is known as the Valley of Death (VoD). This study seeks to identify key factors that influence the financial sustainability of startups during the VoD, which demands a significant amount of funding and government support. (2) Methods: A quantitative methodology was employed, based on a worldwide literature review that pointed out the variables of the object of study; the information collection process was conducted through a questionnaire applied to 352 entrepreneurs in an innovative ecosystem. This study empirically applies a structural equation model to determine the relationship between constructs. (3) Results: A comprehensive analysis of the results indicates that indicators such as positive sales performance, sufficient financial solvency to meet short- and long-term commitments, accurate pricing policies, and access to government and banking support are the primary factors affecting the sustainability of startups in the early stages. (4) Originality: This study provides original and relevant insights into the indicators that affect the financial sustainability of startups during the VoD and offers interesting insights for governments, institutions, and entrepreneurs to foster innovative ecosystems; it also contributes to the extant literature on early-stage entrepreneurial failures.

1. Introduction

Financial sustainability is crucial for early-stage companies to overcome the VoD, which is defined as the first five years of operation of startups, in which they are more vulnerable and tend to fail. The VoD in the field of entrepreneurship, is a period of high risk that implies that the company must take advantage of its cash flow through the operations and benefits obtained from marketing its products or services, without resorting to external resources, for the company to be sustainable (Dean et al., 2022). According to Lefebvre et al. (2022), entrepreneurs must make bold decisions during the early stages of the startup, when they are more susceptible to failure, often due to lack of financial literacy. Despite multiple risk capital efforts and aid provided by public and private entities in entrepreneurship ecosystems to overcome this period, it is essential that the startups obtain profits that generate cash flow that allows them to finance their operation (Teichmann et al., 2024), being the absence of liquidity is the main cause of failure (80%) during the first five years of existence (Kannampuzha & Hockerts, 2019).

Failure in entrepreneurship directly affects the social and economic development of the territories (Torres-Granadillo, 2017). In Latin America, it has a high impact since high failure rates of entrepreneurship occur mainly in the first years of existence; thus, they do not overcome the VoD (Laverde et al., 2019). Proof of this is that in Mexico, 80% of small and medium-sized enterprises fail in the first 5 years due to factors related to risk investment, liquidity, pricing policies, and government and banking support (Kannampuzha & Hockerts, 2019). In Brazil, 46% of the startups fail in the first 3 years (Ferreira et al., 2012), and in Ecuador, 75% of the startups fail in the first 5 years (Coronel & Ortega, 2019). Even outside Latin America, for example in the United States, 78% of the startups fail in the first 3 years (Ferreira et al., 2012), and worldwide, 75% of the startups fail in the first 5 years (Llamas Fernández & Fernández Rodríguez, 2018).

The sustainability of benefits achieved by a company is the basis for being able to face the scenarios of volatility and uncertainty, which strengthens its financial stability and continuity (Zournatzidou et al., 2025). Therefore, strategic managers are faced with a continuous challenge of allocating the limited resources of the company in an increasing pressure environment (Brammer & Pavelin, 2016). However, the high failure rates of early-stage startups are mainly caused by the lack of ability to cover their operational expenses by generating income in a period in which they are more vulnerable due to the lack of financial resources. Thus, they hinder their financial solvency as a result of the absence of liquidity, the inability to raise risk investment, the absence of a pricing policy, and the lack of government and banking support (Sandoval-Gómez et al., 2023).

This paper aims to analyze the influence of financial solvency (FS); venture capital (VC); public policy and banking (PB); and pricing policies (PP) on the financial sustainability of startups during the VoD. It leads us to the following research question: How do the factors FS, VC, PB, and PP influence the financial sustainability of startups during the VoD? From a social point of view, this information helps entrepreneurs to endure over time through financial sustainability, thus generating a positive impact on the social and economic development of the territories and promoting the economy through small and medium-sized enterprises, as well as the entrepreneurial spirit.

This article is structured in six sections, as follows: first, it presents the context of the VoD, with the significant factors that affect startups’ financial sustainability during this period. Subsequent sessions include the following topics: Section 2 discusses the theoretical background of the variables involved in the disciplines of study; Section 3 describes the research method that consists of two stages: one dedicated to the analysis of the literature, and the other dedicated to the statistical analysis of the data; Section 4 presents the results of the methodological approach; Section 5 discusses the research report and presents some theoretical and practical implications; and Section 6 presents the conclusions and limitations of the study, as well as some important ideas, and gives suggestions on future research streams.

2. Literature Review

In recent decades, the term “sustainability” has been studied considering two important aspects and reference dimensions, i.e., time and scope (Guenther et al., 2016). According to Dragu (2019), the concept of sustainable development is defined as a continuous action over time, through which organizations, both public and private, must ensure that the needs of present generations are met without jeopardizing the ability to meet future needs. At the economic level, the term sustainability has been associated with corporate social responsibility (CSR) practices, which organizations carry out specifically in the economic aspect, which is part of the social and environmental triad that makes up the concept.

Under an economic or instrumental logic, companies seek to maximise profits. Therefore, researchers must find a positive empirical relationship between social and financial outcomes to legitimise CSR activities and economically justify socially responsible measures within the company (Vasi, 2015). In the long term, the most successful companies will be those capable of being socially responsible, while achieving good economic results (Parmar et al., 2010). Other research streams highlight the importance of financial sustainability and its relationship with environmental impact and social responsibility in financial decision-making (Santos et al., 2024). In this sense, the requirements of the world and the social sensitivity of the environment constitute a way of adding value to the company so that financial results become the incentive for inclusive management (Fernández-Gago & Martínez-Campillo, 2008; Tsoutsoura, 2004). Other studies argue that there is a positive relationship between CSR and financial results, since social results have a direct impact on the increase in the economic value of the company on the market (Brammer & Pavelin, 2016; Saeednia & Shafeiha, 2012).

Regarding sustainable business management, responsibilities faced by managers to guarantee the financial growth of firms are broad, although it has been shown that there is a positive correlation between CSR and future growth. This article is in line with the research conducted by Gleißner et al. (2022), who argue that to achieve sustainability goals managers must fulfil a wide range of functions, such as marketing, logistics, human management, and productivity, while taking actions that guarantee financial sustainability to ensure long-term financial security. According to Bedoya et al. (2025), firms that perform best in sales and finances through sustainable growth in CSR manage to improve their internal processes and create value in competitive environments.

Barnes and Croker (2013) definitively state that CSR refers to the influence that companies have on communities, individuals, and the environment. Companies must behave positively in social matters, respecting the law and going beyond their own benefits. However, financial sustainability in the context of CSR is addressed solely from the economic perspective that the income-generating company must fulfil. However, financial sustainability from the point of view of CSR, to achieve the purpose of this article, is only developed from the economic vision that the income generation company must fulfil. Studies conducted by Lu and Taylor (2016) through research on 198 companies have shown that financial sustainability can be addressed not as a dimension of CSR but as a variable dependent on CSR activities. Nevertheless, in their work, Klibi et al. (2024) do not consider financial sustainability as an indicator of CSR. Instead, they argue that CSR practices have enabled the company to generate value.

Despite multiple conceptualizations, in this research field it is not possible to have a single definition of financial sustainability. It has also been associated with economic sustainability. Therefore, based on the studies of Gleißner et al. (2022), microfinance, local governments, and health care institutions have been associated under this perspective (Birch et al., 2015; Rodriguez Bolivar et al., 2016; Tehulu, 2013). Authors such as Zabolotnyy and Wasilewski (2019) consider financial sustainability from value dimensions measured by net profit/net equity, total assets/current assets, price/book value and income/total assets, and continuity is measured by current assets/current assets. The above indicates that the literature on financial sustainability lacks generalized concepts in a basic theory and rather has focused on a series of financial measurement indicators.

Financial solvency, risk capital, public and banking policies, and price policy proposed by different authors are presented below as relevant concepts subject of this research.

2.1. Financial Solvency

The first months of operation of startups, which correspond to the initial stage of commercialization of the products or services, entail high risk for their financial sustainability, thus exposing them to failure during the first five years of operation due to the lack of financial solvency at times where cash flows are negative, which is common at startups’ early stages (Lefebvre et al., 2022; Teichmann et al., 2024; Valdivieso et al., 2024). This is sometimes due to the lack of profitability of the business model (Laverde et al., 2019), which directly affects the cash flow of the company (Alunni, 2020; Ellwood et al., 2022; Tanoira et al., 2020; Teichmann et al., 2024). Teichmann et al. (2024) posit that the primary cause of the failure of startups is the absence of liquidity, owing to insufficient income to sustain operational activities, stressing that no company can afford to sell little and have low income; this is lethal at early stages when the company is most vulnerable to failure. From this conceptualization, a set of hypotheses were formulated according to the research question and objective:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Solvency positively affects the financial sustainability of companies during the VoD.

2.2. Venture Capital

One of the main causes of failure for early-stage startups, which in turn leads to the absence of financial solvency, is the lack of risk investment (Bonnin Roca & O’Sullivan, 2022; Bosma et al., 2021; Ellwood et al., 2022; Nemet et al., 2018). Alunni (2020) states that risk investment in startups is vital to avoid early-stage failure. Lefebvre et al. (2022) indicate that the lack of capacity of startups to attract risk investment is one of the main causes of failure at early stages, although there are risk investment funds, usually resources are not sufficient to overcome the initial stages when startups should be sustained on their own (Kannampuzha & Hockerts, 2019). However, it should be considered that in general, the initial resources of startups are the product of the entrepreneurs, their families, and close friends’ savings (Valdivieso et al., 2024). Nemet et al. (2018) argue that great technological advances sometimes do not prevail due to the lack of strength in risk investment, in addition to the need for big investors, mainly due to the uncertainty generated by innovative processes (Ellwood et al., 2022). It leads to risk investors being reluctant to make investments during the early stages of companies (Bonini et al., 2018). Therefore, another hypothesis that arises within the model of this study can be stated as follows:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Start-up capital positively affects the financial sustainability of companies during the VoD.

2.3. Public Policy and Banking

Despite the interest of governments in incentives for public and banking policies aimed at supporting startups, these efforts are still insufficient (Ellwood et al., 2022), as shown by the high failure rates that startups still have during their first five years of operation, corresponding to 75% worldwide (Llamas Fernández & Fernández Rodríguez, 2018). Bosma et al. (2021) establish that the lack of financial sustainability of startups is related to the high tax burdens they must assume. Mukherjee (2024) emphasizes the importance of creating public and banking policies that facilitate the durability of businesses through strategies aimed at reducing taxes and regulating banking policies, articulated to policies to promote economic development. Following the model, it is possible to formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Public and banking policies positively affect the financial sustainability of companies during the VoD.

2.4. Pricing Policies

Having a clear and effective pricing policy is key to achieve the financial sustainability of companies (Banerjee et al., 2024; Kou et al., 2024) because it avoids the financial limitations that lead to the failure of early-stage startups (Zhang & Oki, 2023). Hu et al. (2022) indicate that the price of products or services has a direct impact on the financial sustainability of companies, affecting operating income and cash flow, which are sensitive for startups. Therefore, in order for companies to implement a pricing policy that leads to financial sustainability, Sabine (2019) recommends that it is based on an external price reference, that is, the identification of similar products or services, or that it is priced according to the value generated for the client. This, in turn, would achieve the sufficiency of income and the affordability of the products or services (Van Den Berg, 2015). Consequently, the present research proposes that pricing policies affect financial strategy, given their impact on cash flows and their impact on the financial sustainability of early-stage startups, as argued in the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Pricing policies positively affect the financial sustainability of companies during the VoD.

Several authors propose financial solvency, risk capital, public and banking policies, and pricing policies as factors that affect the financial sustainability of startups during the VoD. Table 1 presents the factors affecting startups’ financial sustainability and justifies the conceptual framework by relating the reference authors who have carried out academic and empirical studies.

Table 1.

Conceptual framework summary of the financial sustainability factors affecting startups.

3. Results

The results of the confirmatory factor analysis indicate an overall Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.96 for the financial solvency construct, risk capital CFI = 0.87, public and banking policies CFI = 0.91, pricing policies CFI = 0.88, and financial sustainability CFI = 0.95. The Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) indicator for the respective constructs was between TLI = 0.86 and TLI = 0.96, indicating an excellent model adjustment within the generally accepted limits in the literature (Hair et al., 2014). The factorial loads for the constructs were between 0.53 and 0.97, establishing a high significance of the items according to the variables in the survey questionnaire (Hair et al., 2019). The reliability analysis in all cases is α > 0.71 and ω > 0.83, which are very close to 1.00, indicating an excellent internal consistency of the indicators (see Table 2). For the convergent analysis, the average variance extracted (AVE) was greater than 0.50 in all cases, indicating an excellent adaptation of the observable variables to the latent construct. The discriminant validity was corroborated by heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratio, evidencing correlation values less than 0.85, i.e., an adequate measure of each construct (Hair et al., 2019; Henseler et al., 2015).

Table 2.

Reliability analysis and average variance extracted (AVE).

The validity of the structural model was exploratory to establish the relationships between the constructs according to the conceptual framework between financial sustainability correlated with financial solvency, risk capital, public policies, and pricing policies.

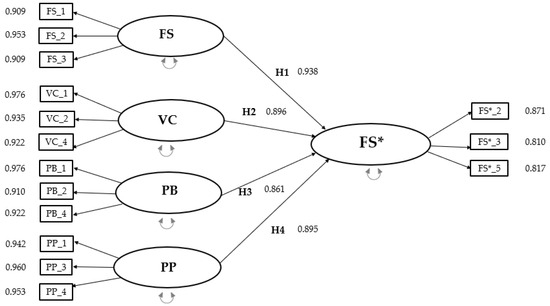

The analysis of the measurement model, based on the results obtained in the principal component analysis and CFA, using the structural equation model and after performing the backward linear regression, confirmed that all the constructs of financial sustainability (FS*) are correlated with the influence of financial solvency (FS); venture capital (VC); public policy and banking (PB); and pricing policy (PP) in each of their dimensions and are statistically significant. The results definitively revealed that all of them were correctly measured by the variables proposed according to the hypothesised model in H1, H2, H3, and H4 and empirically tested according to the theoretical model. Figure 1 shows the relationships between the latent constructs and the structural model variables from structural equation modelling, including factor loadings outputs. These results provide a clear and comprehensive understanding of the outputs between constructs according to the hypothesised model.

Figure 1.

Structural equation modelling (research model). Note: It is observed that financial sustainability (FS*) is associated with four factors as follows: financial solvency (FS); venture capital (VC); public policy and banking (PB); and pricing policies (PP).

Regarding the reliability to estimate the internal consistency of the constructs, to avoid bias in the statistical analysis, Cronbach’s Alpha (α) and McDonald’s Omega (ω) were calculated for the validity and reliability analysis. As shown in Table 2, variance values are appropriate to validate the convergence of the items since they are ≤0.56 in all cases (Hair et al., 2014).

The results confirm the reliability of the model since, in all cases, the values are close to 1, greatly exceeding the threshold of 0.50 (Hair et al., 2014). Then, convergent validity was analysed to ensure that the items congruently represented the construct. The results showed that, in all cases, the limit of 0.50 was exceeded (Henseler et al., 2015).

The discriminant validity, as determined by the heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratio, for the constructs resulted in all the indicators being below the threshold of 0.90 (Henseler et al., 2015) and the threshold of 0.85 proposed by other authors (Hair et al., 2019). In all cases, an appropriate correlation of the variables is validated by not exceeding the previously exposed limits, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Measurement model with discriminant validity.

The goodness-of-fit indicators were checked to analyse the differences between the data and the model. Thus, the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), with a predictive capacity of 0.93, exceeds the limit of 0.50 (Hair et al., 2014). The Root Mean Square error of Approximation (RMSEA) was 0.041, not exceeding the limit of 0.08 (Henseler et al., 2015) and corroborating the predictive capacity of the model. The Coefficient of Determination (R2) validated the predictive capacity of the model as shown in Table 4. The results indicate that the independent variables are explained by ≤60% with the changes in the financial sustainability variable. Finally, the effect size (f2) was 0.31, which indicates that the impact of the independent variables on the dependent ones is considerably high.

Table 4.

Coefficient of determination (R2).

Additionally, the four hypotheses of the model were verified. A regression coefficient of 0.85 was obtained, which is within the 0.81 and 0.98 confidence interval limits (Lowry & Gaskin, 2014). In addition, p = 0.01 (p ≤ 0.05) corroborates the accuracy of the measurement and verifies the hypothetical approach and its corresponding results, as illustrated in Table 5.

Table 5.

Overall hypotheses results.

Finally, hypotheses H1, H2, H3, and H4 were empirically corroborated according to the observed data of the proposed theoretical model, indicating that both principal components analysis and factorial loads analysis of the constructs for each dimension variable is explained by all the other variables. The interpretation of the data allows us to conclude that there is a positive correlation between all the constructs according to the hypothetical model, indicating a high degree of statistical significance.

4. Materials and Methods

To verify the incidence of financial solvency, risk capital, public and banking policies, and pricing policies that affect financial sustainability, a qualitative and quantitative mixed approach methodology was employed. In the qualitative phase, theoretical models were established from the literature review. In the quantitative phase, a confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to validate the instruments and subsequently analyse the data; this study estimated a first order model using structural equations modelling (SEM) under the Partial Least Square (PLS) method. We followed the recommendations of Hox and Bechger (2007), who indicate that SEM is a set of statistical models that allow establishing the relationships and effects between a set of variables that comprise dimensions or factors with multivariate techniques. Statistical analyses for the evaluation and global validation of the model were carried out using the goodness of fit tests as suggested by Nishii et al. (2008). A pilot test was conducted with an initial population of entrepreneurs to determine the validity and reliability of the instrument and make significant adjustments to ensure that the resulting information meets the objectives of the research through a test of representativeness of the instruments (n = 61).

The surveys were applied to 352 entrepreneurs who responded to the surveys out of a total of 385 initially contacted. Entrepreneurs were selected from the entrepreneurship and innovation ecosystem of the city of Medellín according to the database provided by the government and accredited by the Chamber of Commerce of Medellín. As a factor of inclusion, the respondents must be the leaders of the startup and must own a business unit that has survived the VoD and was categorised according to the general rules categorisation government law number 590 of 2000 and Decree 957 of 2019. These laws, which are divided into three macro-sectors, manufacturing, services, and commerce, establish a new classification of the size of companies based on the single criterion of income from ordinary activities. In Colombia, these laws have defined the landscape of the size of companies adopted by the government. Companies in the primary sector, such as agriculture, were not part of the sample. Most participants (46%) were small enterprises with between 11 and 50 employees. This percentage was followed by medium-sized enterprises (31%) with between 51 and 150 employees. Then came micro enterprises (22%) with between 1 and 10 employees. The lowest percentage was for large enterprises (1%) with more than 200 employees. It should also be noted that 52% of the data correspond to service enterprises. This is followed by commercialisation companies (20%). The remaining percentage (28%) corresponds to the manufacturing sector. We also know that this study requires primary data. Three emails were sent to the correspondents requesting them to complete the Google Form questionnaire in accordance with the population to obtain a representative sample. Data was collected between March and August 2024. Data collection was strictly confidential and the information was used for academic purposes only.

The survey did not need personal names or names of institutions or other organizations to be completed. Respondents gave consent to provide their answers, acknowledging their voluntary participation, and their informed consent was considered performed once they accepted to complete the questionnaire. They were given the option to withdraw from the study at any time without any consequences. The survey was completed online with a Likert-type psychometric scale, within a range from 1 to 5. The measurement scale is as follows: totally disagree (1), disagree (2), neither agree nor disagree (3), agree (4), and totally agree (5). The questions of the survey were categorized according to the constructs, adapted to Latin America’s entrepreneurial context, validated by two experts in the field to verify the reliability of the survey instrument. The questionnaire preparation technique was based on a 21-question survey on financial sustainability, financial solvency, public and banking policies, and pricing policies according to the hypothesis model (Appendix A, Table A1). The selection of the survey instrument took into account the theoretical contributions for all the constructs included in the hypothetical model, which have been validated in recent research, in addition to the validation by two experts in the field and the pilot test carried out during the instrument validation phase (Kou et al., 2024; Lefebvre et al., 2022; Mukherjee, 2024; Valdivieso et al., 2024; Zournatzidou et al., 2025). This allowed us to examine a homogeneous set of variables which broadly correspond to the barriers and needs faced by firms in the region’s Innovation Ecosystem. Finally, structural equations modelling was conducted with the JASP software version 0.19.30. Once the data were analysed, atypical data were eliminated by assessing the coefficient of variation to observe repeated responses (VC < 0.25) and detect unanswered items.

5. Discussion

The objective of the present study was to analyse the most significant factors affecting the sustainability of new companies in the period known as the VoD in an ecosystem of entrepreneurship and innovation in Latin America. A structural equation model (SEM) was applied to analyse data obtained from surveys applied to 352 startups from different sectors under a quantitative approach and through a multiple case study. The methodological design aimed to find the best linear correlation between constructs from different categories of data to measure variables, and it was possible to define the statistical significance of each dimension in a set of factors defined for financial sustainability from the hypothesis model.

Research results indicate that the financial sustainability of new companies depends specifically on the income being satisfactory in the company’s financial statements due to sales during the first three years. This result agrees with Dean et al. (2022), who highlight the importance of having sales indicators resulting from commercial operations to flatten the cash flow during the VoD. Although there are some laws and government financial aid to help entrepreneurs from an early age, there are also some internal factors that require clear sales indicators that allow them to achieve the expected turnover according to the indicators set out in the financial plan. Therefore, it is necessary for the entrepreneur to know the market and the average profit margins. In this sense, the effectiveness of management and financial performance indicators, through strategic planning, are necessary to provide valuable information that helps decision-making (Wei & Nguyen, 2020). One way to ensure the stability and sustainability of new startups is to allocate funds to investment in growth activities, allocating a percentage of the annual investment budget to ensure the long-term financial sustainability of the company (Gleißner et al., 2022).

According to the startup owners, it is imperative to possess the financial solvency necessary to leverage operating activities and an adequate supply of resources to address both short- and long-term obligations, thereby averting failure during the VoD. These results corroborate the findings of Kallas and Parts (2021), who discovered that one of the reasons for the failure of new companies in the VoD is not the absence of risk capital, but that the lack of liquidity significantly affects the company’s ability to continue operating and leaves little chance of fulfilling short-term commitments with a tight budget. Therefore, new companies must make great efforts to have a positive cash flow that helps having the necessary liquidity to overcome periods of risk and market uncertainty (Teichmann et al., 2024). However, the key factor implies that leaders of the business units are willing to carry out long-term financial planning, especially in emerging economies where financial management systems are incipient, and most owners manage finances empirically.

The present study introduces an analysis of financial solvency during the early years of the VoD. We especially focus on identifying what factors affect the ability to obtain financial benefits after paying all obligations. These factors include creating mechanisms to alleviate interest rates on financial obligations that allow grace periods so as not to put too much pressure on debt service expenses and even have differential rates according to the risk of the sector that startups belong to. Making effective financial decisions when rates of return do not achieve positive cash flow due to lack of financial solvency is one of the great challenges and risks that entrepreneurs must face (Valdivieso et al., 2024). This study also indicates a high correlation between access to risk capital for initial investment with public and banking policies, highlighting the importance of having traditional banking and public banking with easily accessible resources for business growth. The government should provide entrepreneurs with initiatives that allow them to avoid incurring fines for non-compliance with current legislation, using specific mechanisms that provide relief from legal and fiscal requirements. Therefore, governments should support companies with public resources so they can have what they need for initial investments and access to risk capital (Bonnin Roca & O’Sullivan, 2022; Nemet et al., 2018). This agrees with the findings of Lefebvre et al. (2022), who affirm that not attracting risk capital to cover the needs of investment, operation, and financing is one of the main barriers that must be overcome in the face of possible failure at early stages. Despite traditional banking being strengthened by banking policies in emerging economies, government policies and private investment funds should lead to increased investor firms that leverage startups with high growth potential so that they can achieve continuous growth with venture capital from the first year. In addition, government and banking institutions are responsible for updating policies on tax payments and promoting free investment loans with grace periods, which help entrepreneurs reduce the burden of taxes and debt service in the early phases. This corroborates the conclusions of Belitski and Heron (2017), who argue that public institutions must finance and offer financial incentives to entrepreneurial activities to support and promote the impact of new companies, thus stimulating economic and social growth.

Moreover, we expanded the research on the main factors that positively affect entrepreneurs in terms of pricing policies during the VoD. The pricing policy was considered in this study as the fourth dimension with high correlation with financial sustainability. The relationship between the application of policies to offer discounts to different segments of customers on financial results implies applying early discounts on sales prices. These discounts allowed business owners to differentiate rates, facilitating the sustainability of cash flow and strengthening the business model. Therefore, pricing policies eased the creation of long-term value for shareholders. These findings agree with the results of the study by S. Kimes and Anderson (2012), who indicated that discount practices favour the development and loyalty of customer segments by offering seasonal discounts in periods of poor financial stability. This favours the generation of additional income sources and strengthens financial sustainability (S. E. Kimes, 2009; S. Kimes & Anderson, 2012). However, to face periods of losses in scenarios of uncertainty, entrepreneurs must strengthen the field of knowledge in terms of the application of a clear and effective pricing policy that allows companies to offer satisfactory sale prices. Although entrepreneurs consider it important, there is still a need for more business strengthening programs from the educational sector and government development entities. In addition, it allows entrepreneurs to have financial scenario simulation tools to mitigate the risk and at least understand how prices affect the break-even point and profitability scenarios over time. Educational institutions should also create social support services for entrepreneurial initiatives, providing credit lines for seed capital to reduce the risk of insolvency and to access the necessary assets for entrepreneurs, which strengthens entrepreneurial behaviour (Barton et al., 2018). Therefore, entrepreneurship education provided by public and private institutions could contribute to entrepreneurship education by providing financial tools, including simulators that integrate theoretical concepts with real market trends in business marketing activities (Hsu & Pivec, 2021; Rudhumbu et al., 2020).

This study introduces a multidimensional construct in the field of financial sustainability of entrepreneurs during the VoD based on a theoretical framework. Our conclusions indicate that knowledge of financial management processes has a high impact on the durability of companies, beyond the VoD. Among other reasons, we argue that to be successful in the market, it is not only necessary to have a planning system that guarantees financial sustainability, but also financial management control indicators in all business processes. This result is consistent with the research of Markham et al. (2010), who state that the transition period of a project through the VoD involves not only financial resources but also experience and control systems during the launch process. However, in emerging economies, due to the lack of access to capital and a certain tendency to take limited risks, entrepreneurs start the business without having defined the structure, policies, functions, and responsibilities of financial management, which affects their stability and positioning and makes it difficult to overcome the VoD. We argue that there is a broad relationship between financial sustainability and entrepreneurial action in CSR practices, based on the idea that a company will improve its financial risk management and perform better if it manages its social impacts. Hence, companies that adopt proactive CSR strategies by anticipating or going beyond their legal obligations will benefit in the long run by gaining a competitive advantage in the marketplace (Knott & Wilson, 2024; Vasi, 2015). Our findings are consistent with studies by Zournatzidou et al. (2025), who argue that financial performance positively affects social performance: the more revenue CSR business initiatives generate, the more resources they are likely to invest in social practices. Therefore, companies that prioritize resources in social actions as a result of their profitability will significantly increase shareholder value. However, one of the main reasons for uncertainty about the relationship between CSR and financial performance is that social investments are made when there is a lot of slack. As a result, entrepreneurs face a trade-off between CSR and financial performance, where the actions taken may put the company at an economic disadvantage compared to other, less socially responsible companies. Entrepreneurs need to be aware that 21st century organisations need to increase their commitment to society. This is a way of adding value to the company in which financial results become an incentive to contribute value to stakeholders and generate shared value, and it makes it possible to generate competitive advantages based on the construction of a solid and lasting social fabric (Bedoya et al., 2025). The relationship between CSR and future growth therefore shows that business owners are constantly faced with the decision of how to allocate scarce resources in an increasingly competitive environment. The best long-term path forward means that the most successful new businesses will be those that are able to be socially responsible while achieving good economic performance through risk management strategies. This includes extending government support in the form of tax relief for entrepreneurs to make a financial profit on the net profit resulting from the accounting period. Fostering a close relationship between the entrepreneurship and innovation ecosystem and the public and private sectors may increase the number of companies that cross the VoD, thereby promoting economic and social development.

In summary, entrepreneurs face great challenges to implement strategies that help the financial sustainability of business units during the VoD. There are several common difficulties in entrepreneurship and innovation contexts; for instance, an owner’s high aversion to financial and market risks, which are common in Latin American countries; the lack of access to public programs and business strengthening policies to obtain financial education; and the collaboration between public and private financial institutions to offer soft loans to obtain risk capital with grace periods to alleviate debt service, as a result of financing activities and the purchase of assets of high strategic value. Despite multiple difficulties, it is necessary for new companies to adopt financial practices and policies that allow them to visualize the scenarios they face when creating business units, where it is imperative to promote the responsibility they have as entrepreneurs to guarantee financial sustainability, the creation of new jobs and, therefore, seek economic and social development.

6. Conclusions

The present research aims to analyse the most significant factors that influence the financial sustainability of startups when crossing the VoD. This study explores and analyses the variables that affect the continuity of startups related to their failure. It also includes some specific factors with the previous mapping of the current state of information and scientific understanding, with respect to the VoD, and how to overcome them. It was found that financial sustainability is a key aspect that determines the viability or failure of a startup company through different factors that have been divided into four main categories, with access to risk capital for initial investment being a critical fact of success. Likewise, statistical analysis showed that the financial solvency of emerging companies depends on significant factors related to public and banking policies, as well as to pricing policies to capture new customer segments that positively affect the financial sustainability of the startups, both at the beginning and in periods of growth.

Additionally, the findings confirm that lack of resources in startup and growth periods of firms affect the availability of specialised human resources, and entrepreneurs tend to hire labour with technical skills; what firms require to compete in technological environments is staff with managerial skills and training in business planning during the critical VoD period (Ellwood et al., 2022; Nemet et al., 2018). As organisations move beyond the VoD, they need to have more decision-making power. Decision-making implies that managers need to understand that in periods of organisational evolution, organisations will become more complex (Schmitz & Ganesan, 2014). Considering the importance of more companies crossing the VOD because of its impact on economic growth and the generation of economic and social development, as well as on the prosperity of Latin American countries, it is essential that government and educational institutions carry out activities with entrepreneurs. In order to strengthen the growth of sustainable finance, it is crucial that micro and small business owners have the opportunity to exchange ideas on successful experience in business management, which enriches business education (Dewan & Singh, 2017).

6.1. Theoretical Implications

This document incorporates important social implications; from the research problem, this work aimed to demonstrate that companies are more vulnerable to failure due to the impact of public and banking policies, as well as financial management processes. To address this issue, both a methodological approach and a conceptual framework were used. However, it must be recognized that a company that does not achieve financial sustainability does not have the main resource to survive; therefore, the formulation and control of financial management indicators appear from the theoretical approach based on academic and empirical studies as one of the main aspects to be taken into account in financial sustainability and its correlation with the other constructs. At a theoretical level, we incorporate social responsibility with the concept of the VoD from the perspective of sustainability, which contributes to expanding knowledge in reference to the ethical and social responsibilities involved in the creation of new companies and their impact on stakeholders.

6.2. Practical Implications

This article provides key elements that help researchers, legislators, and entrepreneurs access up-to-date scientific information and knowledge that will promote their development and local socio-economic progress and provide them with the necessary elements for companies to survive over time and not fail in the VoD. The research on management reported in this document had the double objective of contributing to the theory of the processes of the VoD and deriving practical implications for financial management. In the current competitive environment, it is imperative to consider all aspects of the business creation process that affect the financial sustainability of firms. Although CSR is a subject under permanent study in terms of ‘sustainability’, which is specific to the actions of financial management, this research has shown that the impact of profits and the availability of sufficient funds to allocate to social development is purely discretionary and that there is a lack of norms and laws that regulate CSR in the scenarios of management practices.

The results of this study suggest several implications for business management in entrepreneurship during the VoD and reveal the main factors that influence the ability of a company to overcome obstacles. Entrepreneurs must assume the role of agents of change and promote innovative financial management practices. This is imperative because innovation is essential in business-oriented companies. This study also helps entrepreneurs understand how to consider the key factors to address financial sustainability management processes with the help of external agents, such as government policies, universities, and innovation ecosystems, through mentoring and financial education programs, to overcome barriers regarding concepts associated with the VoD.

6.3. Future Research and Limitations

This study recognizes some limitations related to the survey questionnaire, which was aimed at entrepreneurs from a specific business ecosystem and was based on a literature review. However, other important variables that were not considered according to the objective and the proposed hypothetical model may have been left out. Our research framework focuses on the VoD in a particular economy, but longitudinal and comparative studies between similar countries could be carried out to exchange ideas and enrich knowledge and prevent the failure of new companies. Future areas of research could address the VoD in business ecosystems other than emerging economies, focusing on issues such as the synergistic relationship between public–private and innovation models. Much of the existing research is related to the early stages in micro and small businesses, but new knowledge could be developed through longitudinal studies of the aspects that affect permanence and sustainability of medium-sized companies during the VoD.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.Z.-M. and J.C.-G.; methodology, E.R. and E.R.-G.; software, M.B.-V. and J.C.-G.; validation, M.B.-V. and J.C.-G.; formal analysis, M.B.-V. and J.C.-G.; investigation, M.B.-V. and J.C.-G.; resources, C.Z.-M. and J.C.-G.; data curation, M.B.-V. and C.Z.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, C.Z.-M. and M.B.-V. writing—review and editing, M.B.-V. and E.R.; visualization, C.Z.-M. and S.G.-B.; supervision, E.R.-G. and M.B.-V.; and project administration, J.C.-G. and S.G.-B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the protocol approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Tecnológico de Antioquia-Medellín according to Act ‘Number 01 of semester 2022-02’ of the ordinary meeting of ‘28 July 2022’ in Medellin Colombia, according to Article 11 of Resolution 8430 of the Ministry of Health of Colombia. Act 01 documents are protocol documents of the Dean’s Offices where the research is approved and are of a private nature, with reference to RESOLUTION Nº 8430 OF 1993 (4 October), which is a government document that establishes the scientific, technical, and administrative standards for health research and other dispositions’. CHAPTER 1. OF THE ETHICAL ASPECTS OF RESEARCH ON HUMAN BEINGS in ARTICLE 11 regulates research in different categories.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding Johnatan Castro-Gómez (johnatan.castro@tdea.edu.co).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Constructs and survey items.

Table A1.

Constructs and survey items.

| Construct | Question | Item Code |

|---|---|---|

| Financial sustainability | Satisfactory results were achieved in the sales levels of your startup during the first three years. | FS*_1 |

| Frequent long term financial planning is carried out. | FS*_2 | |

| Resources were earmarked for investment in growth activities by allocating a percentage of the company’s annual budget. | FS*_3 | |

| The company achieved satisfactory value creation indicators to add long-term shareholder value. | FS*_4 | |

| Timely decision making for investment, financing, and operating activities facilitated financial continuity and stability. | FS*_5 | |

| Financial solvency | The initial resources of your startup were sufficient to meet short- and long-term commitments. | FS_1 |

| The repurchase processes of its customers favoured financial solvency. | FS_2 | |

| During its first few years, it made a profit after paying all its obligations. | FS_3 | |

| The business achieved continuous growth from the first year onwards. | FS_4 | |

| Startup Capital | Access to capital for initial investment in their business was available. | VC_1 |

| Support was available from angel investors to support their business. | VC_2 | |

| Support was obtained from financial institutions to facilitate loans for the business. | VC_3 | |

| The terms of loans from banking institutions made it easier to obtain funds to start a business. | VC_4 | |

| Public policy and banking | Access to capital for initial investment in their business was available. | PB_1 |

| Support was available from angel investors to support their business. | PB_2 | |

| Support was obtained from financial institutions to facilitate loans for the business. | PB_3 | |

| The terms of loans from banking institutions made it easier to obtain funds to start a business. | PB_4 | |

| Pricing policies | Policies have been implemented to offer discounts to different customer segments. | PP_1 |

| The implementation of a clear and effective pricing policy enables companies to offer satisfactory selling prices. | PP_2 | |

| Advance selling prices achieved tariff differentiation, facilitating cash flow sustainability. | PP_3 | |

| Pricing policies facilitated the creation of long-term shareholder value. | PP_4 |

References

- Alunni, A. (2020). La importancia de la inversión de riesgo corporativo para superar el valle de la muerte en la transferencia tecnológica universitaria. Revista de Fomento Social, 1(2020), 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A., Parikh, A., & Gupta, A. K. (2024). Theoretical underpinning of groundwater situation in India: Search for efficient policy mechanism. Purushartha—A Journal of Management, Ethics and Spirituality, 16, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, L. R., & Croker, N. (2013). The relevance of the ISO26000 social responsibility issues to the Hong Kong Construction Industry. Australasian Journal of Construction Economics and Building, 13(3), 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, M., Schaefer, R., & Canavati, S. (2018). To be or not to be a social entrepreneur: Motivational drivers amongst American business students. Entrepreneurial Business and Economics Review, 6(1), 9–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedoya, M., Román, E., Gutiérrez, S., Pérez, E., Zapata, C., Castro-Gómez, J., & Jaramillo, J. (2025). The impacts of corporate social responsibility on internal organizational processes to create shared value. Cogent Business & Management, 12(1), 2418420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belitski, M., & Heron, K. (2017). Expanding entrepreneurship education ecosystems. Journal of Management Development, 36(2), 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, S., Murphy, G. T., MacKenzie, A., & Cumming, J. (2015). In place of fear: Aligning health care planning with system objectives to achieve financial sustainability. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 20(2), 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonini, S., Capizzi, V., Valletta, M., & Zocchi, P. (2018). Angel network affiliation and business angels’ investment practices. Journal of Corporate Finance, 50, 592–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnin Roca, J., & O’Sullivan, E. (2022). The role of regulators in mitigating uncertainty within the Valley of Death. Technovation, 109, 102157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosma, N., Hill, S., Ionescu-Somers, A., Kelley, D., Guerrero, M., & Schott, T. (2021). Global entrepreneurship monitor 2020/2021 global report (211p). The Global Entrepreneurship Research Association, London Business School. [Google Scholar]

- Brammer, S. J., & Pavelin, S. (2016). Corporate reputation and corporate social responsibility. In A handbook of corporate governance and social responsibility (pp. 437–448). Taylor and Francis/Balkema. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butscher, S. A., Vidal, D., & Dimier, C. (2009). Managing hotels in the downturn: Smart revenue growth through pricing optimisation. Journal of Revenue and Pricing Management, 8, 405–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coronel, A., & Ortega, M. (2019). Perspectivas del emprendimiento en el Ecuador, sus dificultades y la informalidad. YACHANA, Revista Científica, 8(3), 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, T., Zhang, H., & Xiao, Y. (2022). The role of complexity in the Valley of Death and radical innovation performance. Technovation, 109, 102160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewan, J., & Singh, A. K. (2017). The configuration approach to entrepreneurship education: The case of an entrepreneurship course in a management program. In Entrepreneurship education: Experiments with curriculum, pedagogy and target groups (pp. 267–285). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragu, I. (2019). The evolution of corporate sustainability and corporate social responsibility towards the common goal of integrated reporting. In S. O. Idowu, & M. Del Baldo (Eds.), CSR, sustainability, ethics & governance. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellwood, P., Williams, C., & Egan, J. (2022). Crossing the valley of death: Five underlying innovation processes. Technovation, 109, 102162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Gago, R., & Martínez-Campillo, A. (2008). Naturaleza Estratégica de la Responsabilidad Social Empresarial. Journal of Globalization, Competitiveness & Governability/Revista de Globalización, Competitividad y Gobernabilidad/Revista de Globalização, Competitividade e Governabilidade, 2(2), 116–125. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, L. F. F., Oliva, F. L., dos Santos, S. A., e Grisi, C. C. H., & Lima, A. C. (2012). Análise quantitativa sobre a mortalidade precoce de micro e pequenas empresas da cidade de São Paulo. Gestão & Produção, 19(4), 811–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleißner, W., Günther, T., & Walkshäusl, C. (2022). Financial sustainability: Measurement and empirical evidence. Journal of Business Economics, 92(3), 467–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenther, E., Endrikat, J., & Guenther, T. W. (2016). Environmental management control systems: A conceptualization and a review of the empirical evidence. Journal of Cleaner Production, 136 (Part A), 147–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2019). Multivariate data analysis (8th ed., 832p). Learning EMEA. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & Kuppelwieser, V. G. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. European Business Review, 26(2), 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hox, J. J., & Bechger, T. M. (2007). An introduction to structural equation modeling. Family Science Review, 11, 354–373. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, J. L., & Pivec, M. (2021). Integration of sustainability awareness in entrepreneurship education. Sustainability, 13(9), 4934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X., Duan, J., & Li, R. (2022). Research on high-speed railway pricing and financial sustainability. Sustainability, 14(3), 1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallas, E., & Parts, E. (2021). From entrepreneurial intention to enterprise creation: The case of Estonia. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 13(5), 1192–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannampuzha, M., & Hockerts, K. (2019). Organizational social entrepreneurship: Scale development and validation. Social Enterprise Journal, 15(3), 290–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimes, S., & Anderson, C. (2012). Hotel revenue management in an economic downturn. In M. C. Sturman, J. B. Corgel, & R. Verma (Eds.), The cornell school of hotel administration on hospitality: Cutting edge thinking and practice (Chapter 26, pp. 405–416). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Kimes, S. E. (2009). Hotel revenue management in an economic downturn: Results of an international study. In Cornell Hospitality Report (Vol. 9). Cornell University, Center for Hospitality Research. Available online: https://ecommons.cornell.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/0cc54201-3cfd-4dbb-8c7d-6367059806a5/content (accessed on 4 July 2024).

- Klibi, E., Damak, S., & Elwafi, O. (2024). The impact of sustainability assurance levels on market capitalization: The case of French firms. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knott, S., & Wilson, J. P. (2024). Core charitable purpose and voluntary CSR activities in charity organisations: Do they conflict? Social Responsibility Journal, 20(6), 1056–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, K., Dou, Y., & Arai, I. (2024). Analysis of the forces driving public hospitals’ operating costs using LMDI decomposetion: The case of Japan. Sustainability, 16(2), 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laverde, F., Osorio, F., Medina, L., Varela, R., Gomez, E., Parra, L. D., Matiz, F., Buelvas, P., Gomez, L., & Rueda, F. (2019). Estudio de la actividad emprendedora en Colombia. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, V., Certhoux, G., & Radu-Lefebvre, M. (2022). Sustaining trust to cross the Valley of Death: A retrospective study of business angels’ investment and reinvestment decisions. Technovation, 109, 102159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenssen, J. J., Dentchev, N. A., & Roger, L. (2014). Sustainability, risk management and governance: Towards an integrative approach. Corporate Governance, 14(5), 670–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llamas Fernández, F. J., & Fernández Rodríguez, J. C. (2018). Lean startup methodology: Development and application to develop entrepreneurship. Revista Escuela de Administración de Negocios, 84, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowry, P. B., & Gaskin, J. (2014). Partial least squares (PLS) structural equation modeling (SEM) for building and testing behavioral causal theory: When to choose it and how to use it. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 57(2), 123–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W., & Taylor, M. E. (2016). Which factors moderate the relationship between sustainability performance and financial performance? A meta-analysis study. Journal of International Accounting Research, 15(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markham, S. K., Ward, S. J., Aiman-Smith, L., & Kingon, A. I. (2010). The valley of death as context for role theory in product innovation. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 27(3), 402–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, U. (2024). Autism ashram. Emerald Emerging Markets Case Studies, 14(3), 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemet, G. F., Zipperer, V., & Kraus, M. (2018). The valley of death, the technology pork barrel, and public support for large demonstration projects. Energy Policy, 119(C), 154–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishii, L. H., Lepak, D. P., & Schneider, B. (2008). Employee attributions of the “Why” of HR practices: Their effects on employee attitudes and behaviors, and customer satisfaction. Personnel Psychology, 61(3), 503–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, B. L., Freeman, R. E., Harrison, J. S., Wicks, A. C., Purnell, L., & de Colle, S. (2010). Stakeholder theory: The state of the art. The Academy of Management Annals, 4(1), 403–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez Bolivar, M. P., Navarro Galera, A., Alcaide Munoz, L., & Lopez Subires, M. D. (2016). Risk factors and drivers of financial sustainability in local government: An empirical study. Local Government Studies, 42(1), 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudhumbu, N., du Plessis, E., & Maphosa, C. (2020). Challenges and opportunities for women entrepreneurs in Botswana: Revisiting the role of entrepreneurship education. Journal of International Education in Business, 13(2), 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabine, V. (2019). Assessment of external price referencing and alternative policies. Sustainability, 11(18), 5139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeednia, H., & Shafeiha, S. (2012). Investigation of the link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility from consumers’ view. International Journal of Economics and Business Modeling, 3(2), 177–182. [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval-Gómez, R. J., Álvarez-Cedillo, J. A., Castellanos-Sánchez, E. I., Álvarez-Sánchez, T., & Perez-García, R. (2023). Development of a technological innovation and social entrepreneurship training program to generate services in a Mexican public entity. Eastern-European Journal of Enterprise Technologies, 6(13), 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L. L., Gomes, C., Malheiros, C., Crespo, C., & Bento, C. (2024). Factors influencing hotel revenue management in times of crisis: Towards financial sustainability. International Journal of Financial Studies, 12(4), 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, C., & Ganesan, S. (2014). Managing customer and organizational complexity in sales organizations. Journal of Marketing, 78(6), 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanoira, B., Gerardo, F., Valencia, S., Alberto, R., Ponce, L., & Eugenia, M. (2020). Factores que afectan la experiencia de emprendimiento en estudiantes universitarios. Un estudio en una institución privada en Mérida, Yucatán, México. Nova Scientia, 12(24), 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehulu, T. A. (2013). Determinants of financial sustainability of microfinance institutions in East Africa. European Journal of Business and Management, 5(17), 152–158. [Google Scholar]

- Teichmann, F. M. J., Boticiu, S. R., & Sergi, B. S. (2024). Compliance concerns in sustainable finance: An analysis of peer-to-peer (P2P) lending platforms and sustainability. Journal of Financial Crime, 31(4), 993–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Granadillo, F. (2017). Trayectorias del emprendimiento hacia el desarrollo económico local. Revista Venezolana de Gerencia, 22(77), 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoutsoura, M. (2004). Corporate social responsibility and financial performance. University of California Berkley, Center for Responsible Business. Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/111799p2 (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Valdivieso, G. P., Salas-Tenesaca, E. E., & Paucar, I. (2024). Entre la necesidad y la oportunidad: Habilidades administrativas y financieras de las mujeres emprendedoras del sector popular y solidario en Ecuador. European Public & Social Innovation Review, 9, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Berg, C. (2015). Pricing municipal water and wastewater services in developing countries: Are utilities making progress toward sustainability? In A. Dinar, V. Pochat, & J. Albiac-Murillo (Eds.), Water pricing experiences and innovations (Vol. 9, pp. 164–166). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasi, I. B. (2015). Is greenness in the eye of the beholder? Corporate social responsibility frameworks and the environmental performance of US firms. In K. Tsutsui, & A. Lim (Eds.), Corporate Social Responsibility in a Globalizing World (Chapter 11, pp. 365–392). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z., & Nguyen, Q. T. K. (2020). Chinese service multinationals: The degree of internationalization and performance. Management International Review, 60(6), 869–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabolotnyy, S., & Wasilewski, M. (2019). The concept of financial sustainability measurement: A case of food companies from Northern Europe. Sustainability, 11(18), 5139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.-Y., & Oki, T. (2023). Water pricing reform for sustainable wáter resources management in China’s agricultural sector. Agricultural Water Management, 275, 108045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zournatzidou, G., Ragazou, K., Sklavos, G., & Sariannidis, N. (2025). Examining the impact of environmental, social, and corporate governance factors on long-term financial stability of the european financial institutions: Dynamic panel data models with fixed effects. International Journal of Financial Studies, 13(1), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).