The Impact of Geographical Factors on the Banking Sector in El Salvador

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Geography and Financial Inclusion

2.2. Regional Economic Disparities and Banking Development

2.3. Natural Disasters and Banking Vulnerability

2.4. Urbanization and Financial Growth

2.5. El Salvador’s Banking Sector

- Banco Agrícola S.A.: Parent Company: Bancolombia S.A. (San Salvador, El Salvador) One of the largest banks in El Salvador, offering comprehensive financial services. As of 31 December 2023, Bancolombia reported a total equity of approximately COP 35.5 trillion (around USD 9.5 billion). The bank’s capital is divided into common shares, with Grupo de Inversiones Suramericana and the Colombian government among its major shareholders (Bancolombia S.A., 2023)

- Banco Cuscatlán de El Salvador, S.A.: Parent Company: Grupo Terra (San Salvador, El Salvador). Provides a wide range of banking services to private and corporate clients. Grupo Terra is a diversified conglomerate with investments in energy, real estate, and financial services. Specific capital details for its banking operations are not publicly disclosed.

- Banco Davivienda Salvadoreño, S.A.: A subsidiary of Colombia’s Davivienda, offering personal and corporate banking services. As of 31 December 2023, Banco Davivienda reported a total equity of approximately COP 15.2 trillion (around USD 4.1 billion). The bank’s capital comprises common shares, primarily held by Grupo Bolívar (San Salvador, El Salvador), a Colombian conglomerate (Banco Davivienda, 2023).

- Banco de América Central (BAC): Parent Company: BAC Credomatic (San Salvador, El Salvador), owned by Grupo Aval (Colombia). Offers various financial products and services. Grupo Aval, as of 31 December 2023, reported a total equity of approximately COP 30 trillion (around USD 8 billion). BAC Credomatic operates as a subsidiary within this structure, with capital allocated across its Central American operations (Banco de America Central, 2023).

- Banco G&T Continental El Salvador, S.A.: Parent company: Banco G&T Continental (San Salvador, El Salvador). Provides a range of banking services to individuals and businesses. As of 31 December 2023, Banco G&T Continental reported a total equity of approximately GTQ 7.5 billion (around USD 970 million). The bank’s capital is divided into common shares held by various private investors (Banco G&T Continental, 2023).

- Banco Promerica, S.A.: Parent Company: Promerica Financial Corporation (San Salvador, El Salvador). Offers financial services, including savings and checking accounts, loans, and credit cards. Promerica Financial Corporation operates across nine countries in Latin America. As of 31 December 2023, it reported a consolidated total equity of approximately USD 1.2 billion. The capital is distributed among its subsidiaries, including Banco Promerica in El Salvador (Banco Promerica, 2023).

- Banco Azul de El Salvador: A newer bank that began operations in 2015, providing various banking services. Established with the ownership of several Salvadorian investors in 2015, specific capital structure details are not publicly disclosed or readily available, the webpage was blocked for international access, and data was unattainable.

- Banco ProCredit: Parent company: ProCredit Holding AG & Co. KGaA (San Salvador, El Salvador). Focuses on providing financial services to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and individuals. As of 31 December 2023, ProCredit Holding reported a total equity of approximately EUR 700 million (around USD 800 million). The capital is distributed among its network of banks in developing countries, including Banco ProCredit in El Salvador (Banco ProCredit, 2023).

- Banco Industrial El Salvador, S.A.: Parent company: Banco Industrial (San Salvador, El Salvador). Offers a range of banking services to private and corporate clients. As of 31 December 2023, Banco Industrial reported a total equity of approximately GTQ 10 billion (around USD 1.3 billion). The bank’s capital is divided into common shares held by private investors and corporate entities (Banco Industrial El Salvador, 2023).

- Citibank, N.A. Sucursal El Salvador: Parent company: Citibank, N.A. (San Salvador, El Salvador). Provides corporate and investment banking services. As of 31 December 2023, Citibank, N.A. reported a total equity of approximately USD 150 billion. The bank’s capital comprises common shares held by public investors, with Citigroup Inc. as the holding company (Citibank, 2023).

- Scotiabank El Salvador, S.A.: Parent company: The Bank of Nova Scotia (San Salvador, El Salvador). Formerly a subsidiary of Canada’s Scotiabank, the bank’s operations in El Salvador were sold to Imperia Intercontinental Inc., the main shareholder of Banco Cuscatlán, in 2020. As of 31 October 2023, Scotiabank reported a total equity of approximately CAD 70 billion. The bank’s capital comprises common shares, preferred shares, and other equity instruments held by public investors (Scotiabank, 2020).

- Banco Azteca El Salvador: Parent company: Grupo Elektra (Mexico City, Mexico). Providing consumer banking services. As of 31 December 2023, Grupo Elektra reported a total equity of approximately MXN 100 billion (around USD 5 billion). Banco Azteca operates as a subsidiary within this structure, with capital allocated across its operations in Mexico and Central America (Banco Azteca, 2023).

- Banco Atlántida El Salvador: Parent company: Banco Atlantida (San Salvador, El Salvador). Offering various banking services. As of 31 December 2023, Banco Atlántida reported a total equity of approximately HNL 15 billion (around USD 600 million). The bank’s capital is divided into common shares held by private investors and corporate entities (Banco Atlantida El Salvador, 2023).

- 14.

- Banco Hipotecario de El Salvador: Specializes in mortgage financing and offers other banking services. The state-owned bank was established in 1935, focusing on providing financial services to various economic sectors, including small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). As of 31 December 2023, Banco Hipotecario reported a total equity of approximately USD 150 million. The bank’s capital is divided into common shares held entirely by the Salvadoran government (Banco Hipotecario, 2023).

- 15.

- Banco de Fomento Agropecuario: El Salvador’s second state-owned bank was established in 1973 and focuses on agricultural development financing. As of 31 December 2023, Banco de Fomento Agropecuario reported a total equity of approximately USD 100 million. The bank’s capital is fully owned by the Salvadoran government (Banco de Fomento Agropecuario, 2023).

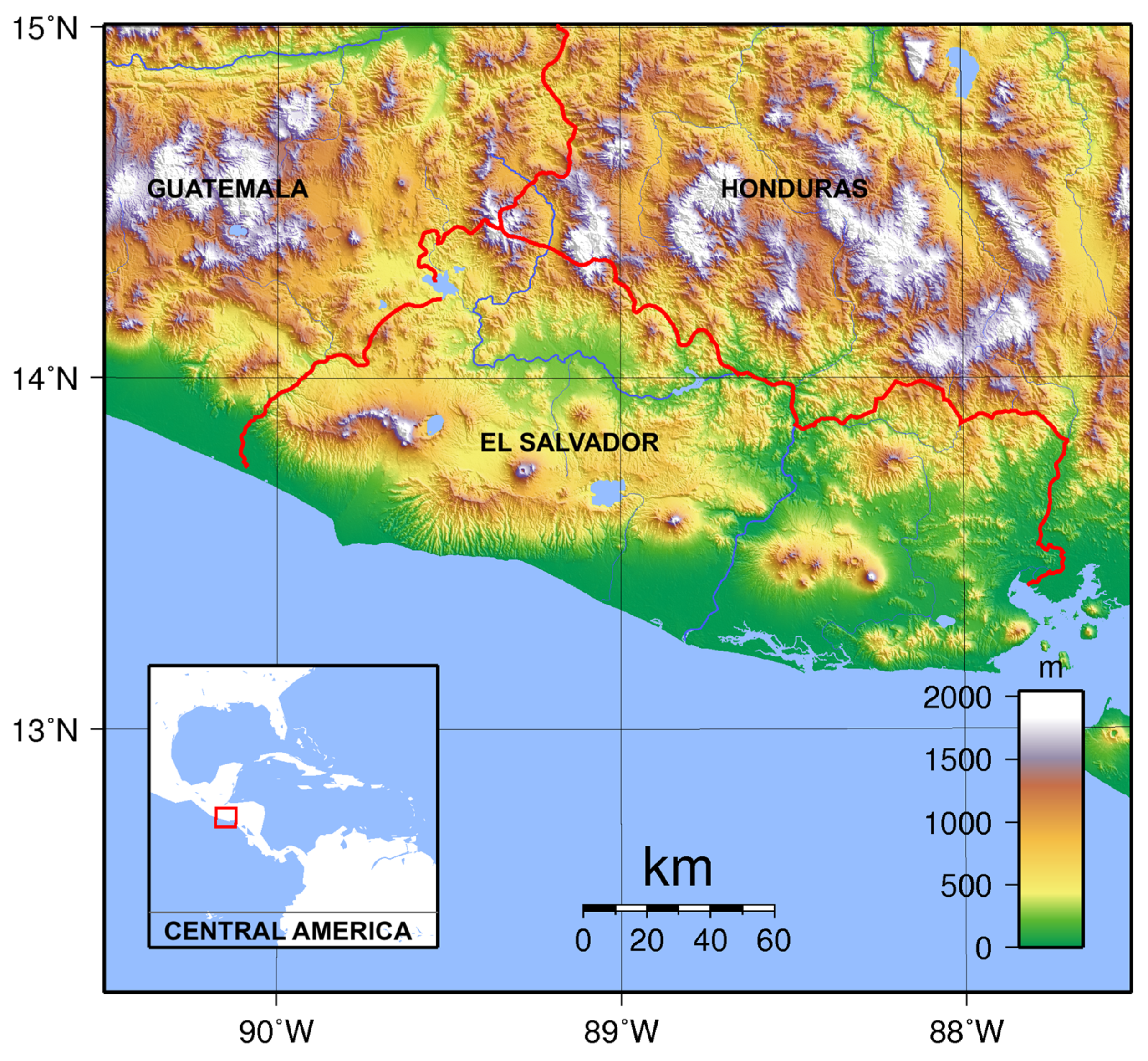

2.6. Geographical Overview of El Salvador

2.6.1. Topography, Soils and Waterbodies

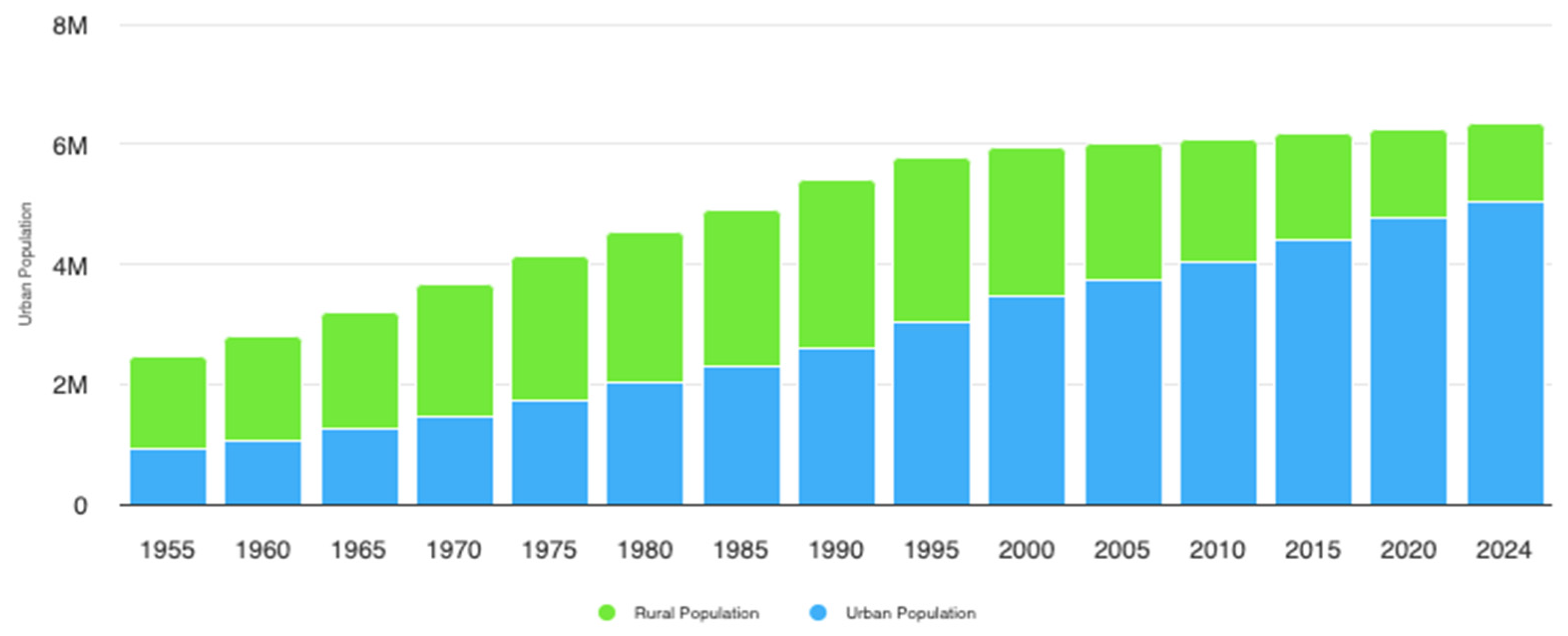

2.6.2. Urbanization

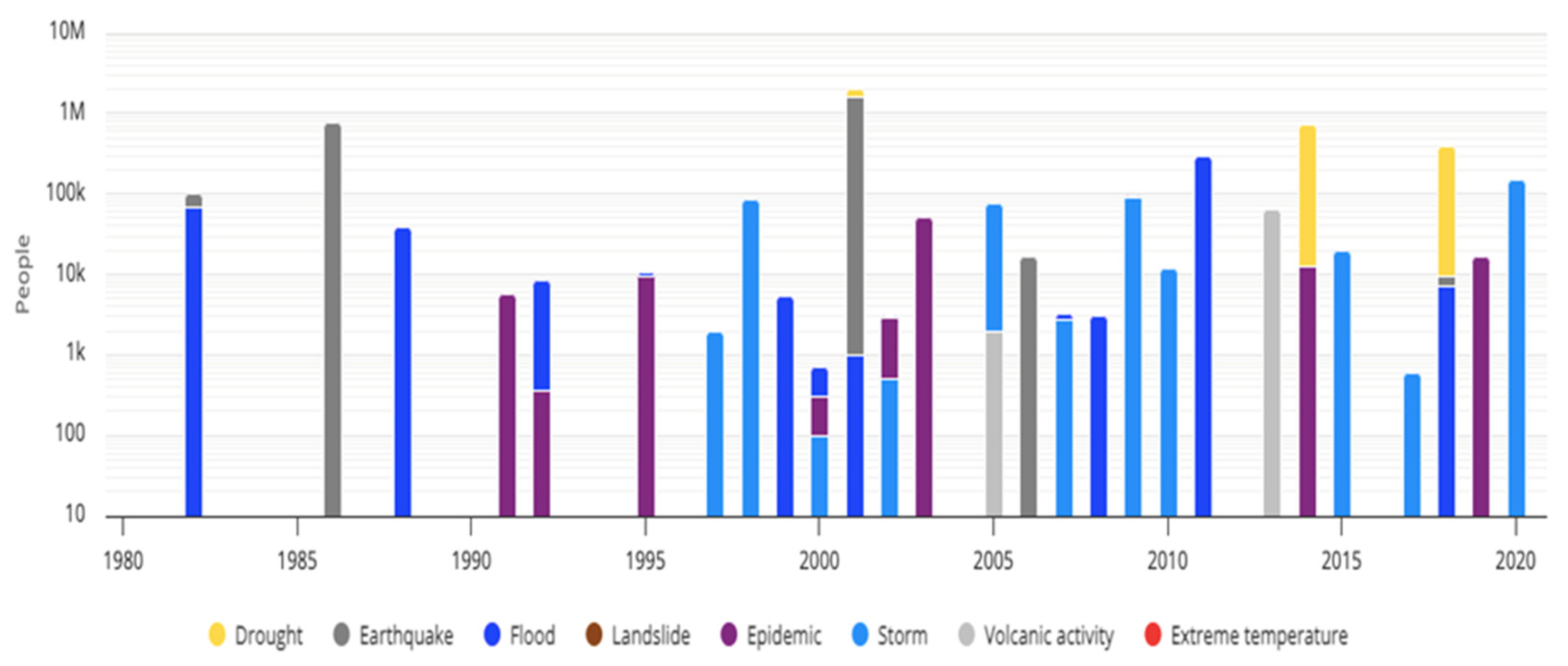

2.6.3. Natural Disaster Vulnerability

3. Methodology

- The three most popular male first names were Jose (545,311); Juan (140,959); Carlos (122,815).

- The three most popular female first names were Maria (565,457); Ana (224,666); Rosa (134,638).

- Combined with the six most popular surnames in El Salvador, including Hernandez (246,359); Lopez (143,989); Rodriguez (109,131); Perez (105,669); Martinez (191,223); and Garcia (133,801).

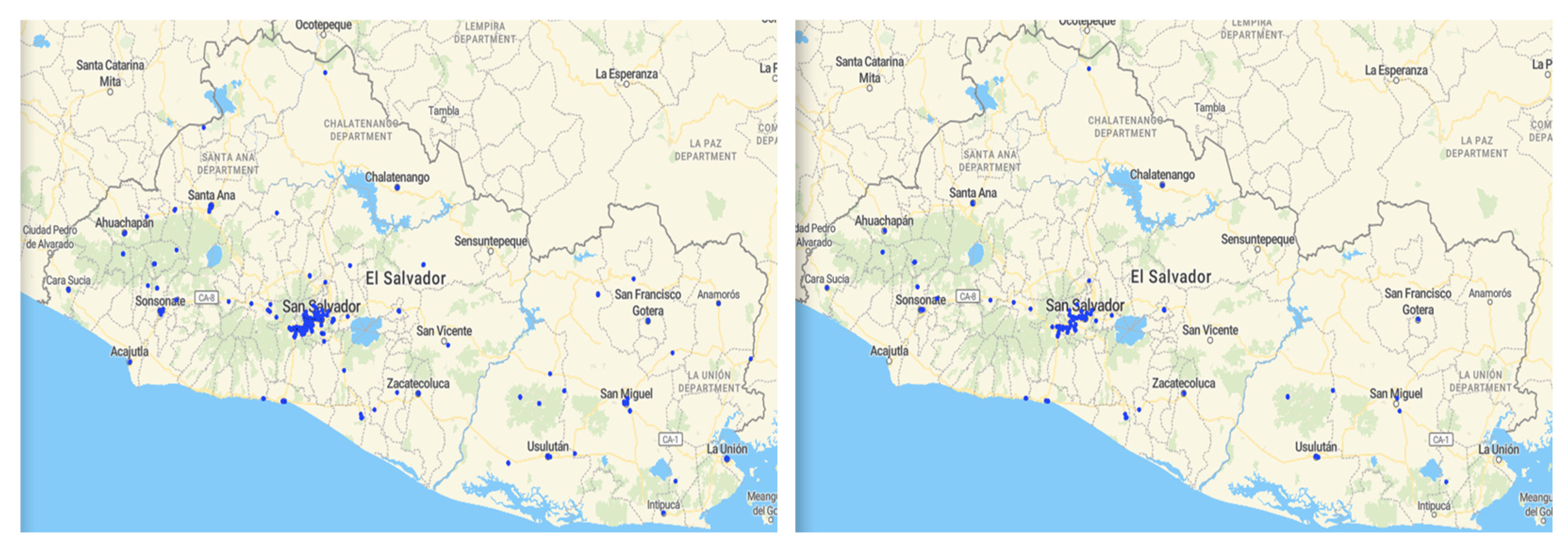

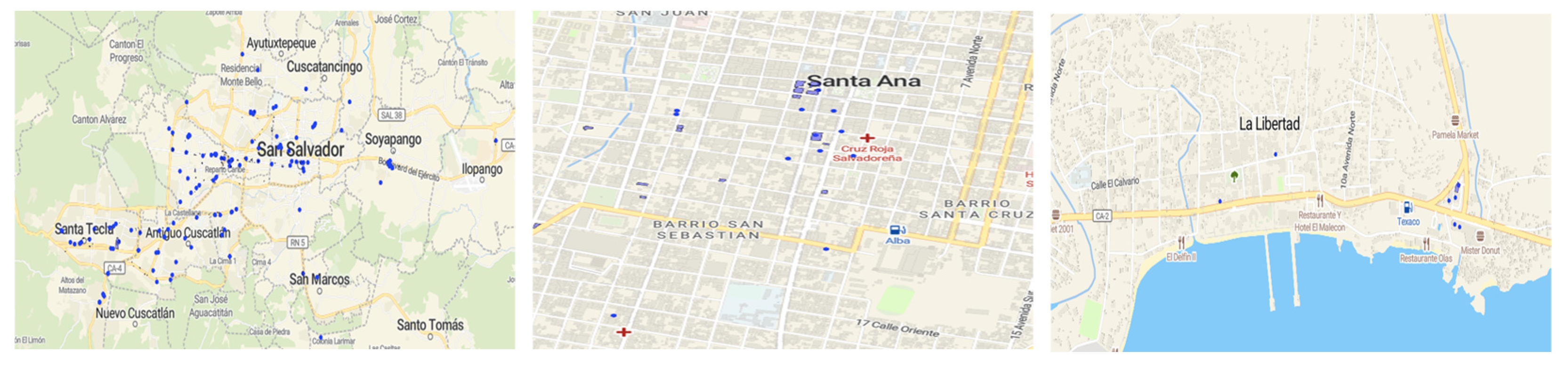

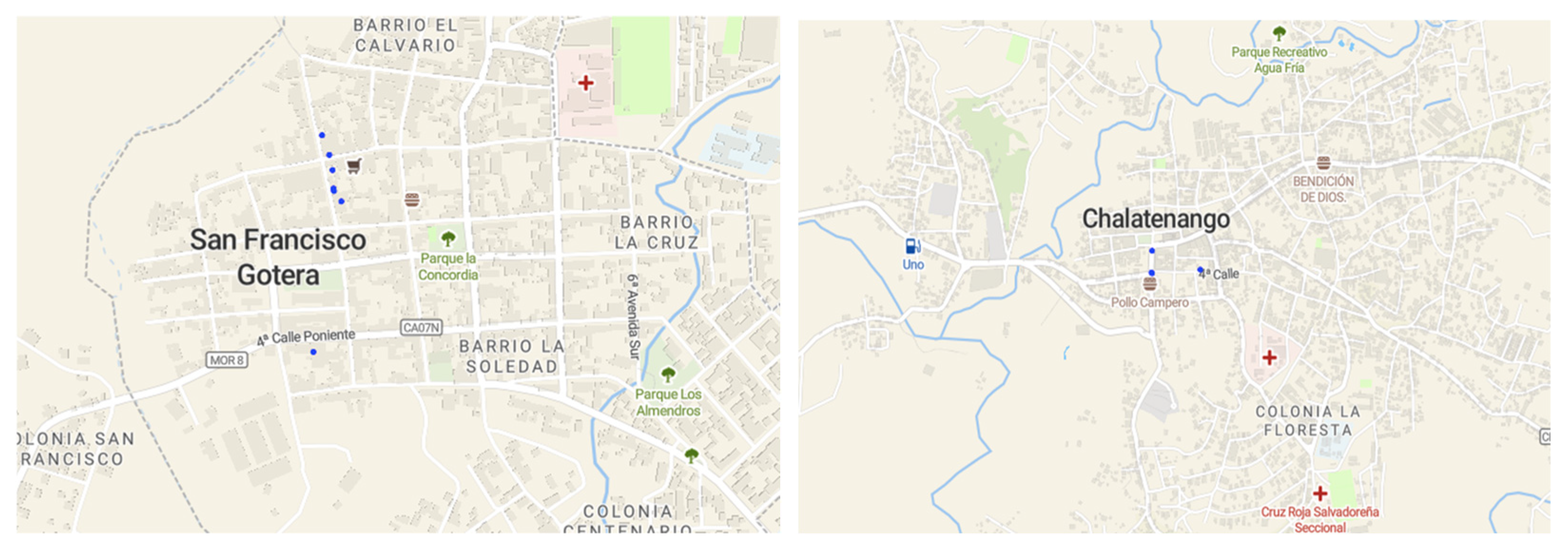

- Geographical location (e.g., urban centers with high population density such as San Salvador, Santa Ana and La Libertad) and lesser populated rural regions (e.g., Morazan, San Francisco Gotera, and Chalatenango).

- Professional affiliation (e.g., commercial banks, regulatory institutions, and financial technology providers or job specificity).

- User status and experience (e.g., current clients of formal banks vs. informal system users).

- Experience with financial services in disaster-prone or infrastructure-deficient regions.

- Where do you live? (Geographical location, infrastructural/logistical challenges, and disaster risk exposure).

- What is your occupation? (Professional affiliation, risk management practices, and banking system engagement).

- Do you have a bank account? (User status and barriers to formal financial participation).

- What is your experience with banking in general, and have you ever experienced issues with access to financial transactions? (Experience, perceptions of digital banking, and access barriers during and after disasters).

4. Results and Analysis

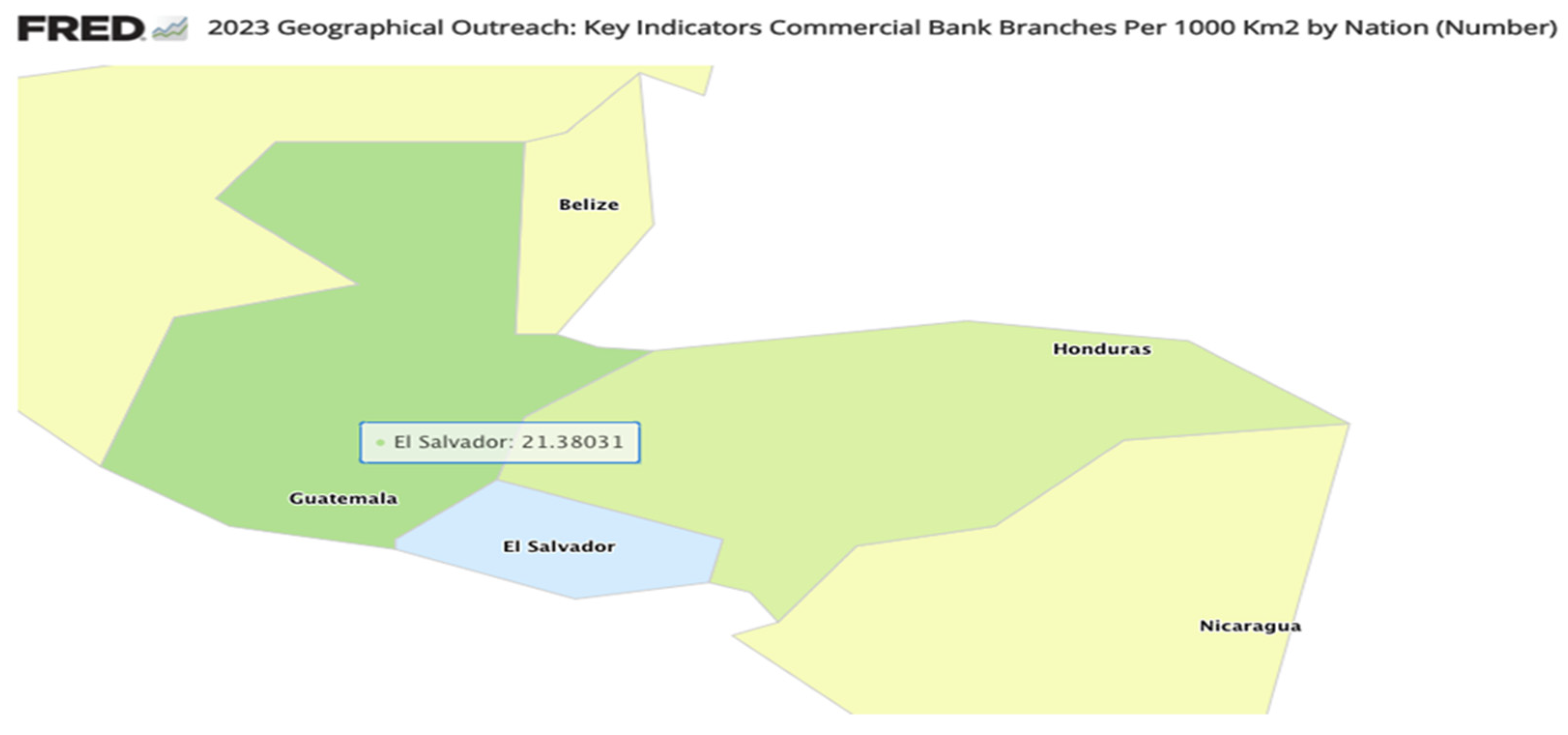

4.1. Geographical Distribution of Banking Services

4.2. Challenges in Rural Banking

4.3. Impact of Natural Disasters

4.4. Urbanization and Financial Services

5. Discussion

5.1. Financial Exclusion in Rural Areas

5.2. Natural Disaster Risk Management

5.3. Urbanization and Informal Finance

6. Conclusions

6.1. Geographical Disparities and Financial Exclusion

6.2. Impact of Natural Disasters on the Banking Sector

6.3. Urbanization and Informal Finance

6.4. Towards a More Inclusive and Resilient Banking System

6.5. Final Reflections

6.6. Limitations

6.7. Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alessandrini, P., Croci, M., & Zazzaro, A. (2005). The geography of banking power: The role of functional distance. Banca Nazionale del Lavoro Quarterly Review, 58(235), 129–167. [Google Scholar]

- Anzoategui, D., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Martinez Peria, M. S. (2014). Remittances and financial inclusion: Evidence from El Salvador. World Development, 54, 338–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ATM Travel Guide. (2024). ATMs in El Salvador. Available online: https://www.atmtravelguide.com/atms-in-el-salvador/ (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- Balliester Reis, T. (2020). Financial inclusion, poverty and income inequality in low and middle-income countries: A mixed-method investigation [Doctoral dissertation, University of Leeds]. [Google Scholar]

- Banco Atlantida El Salvador. (2023). Memoria anual 2023. Available online: https://www.bancoatlantida.com.sv/documentos/MemoriaAnualRE/Memoria-Anual-2023.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- Banco Azteca. (2023). Reportes financieros Banco Azteca financieros. Available online: https://www.grupoelektra.com.mx/es/banco-azteca-financieros (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- Banco Davivienda. (2023). Consolidated financial statements: For the year ended as of December 31st, 2023. Available online: https://ir.davivienda.com/estados-financieros/?tab=11#financial-info (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- Banco de America Central. (2023). Estados financieros al 31 de diciembre de 2023 y 2022. Available online: https://www.baccredomatic.com/sites/default/files/2024-02/sv-informe_anual_auditores-2023.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- Banco de Fomento Agropecuario. (2023). Informe de auditoría de estados financieros del 01 de enero al 31 de diciembre de 2023 y 2022. Available online: https://www.bfa.gob.sv/download/informe-de-auditoria-de-estados-financieros-del-01-de-enero-al-31-de-diciembre-de-2023-y-2022/ (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- Banco G&T Continental. (2023). Estado banco. Available online: https://assets.gtc.com.gt/uploads/b7f2172e-e15e-4f99-8ca4-b4477c62414b/original/Estado_de_Resultados_Diciembre_2023.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- Banco Hipotecario. (2023). Estado financiero publicación diciembre 2023. Available online: https://www.bancohipotecario.com.sv/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Estado-Financiero-Publicacion_Diciembre-2023-sin-firma.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- Banco Industrial El Salvador. (2023). Estados financieros. Available online: https://www.corporacionbi.com/sv/bancoindustrialsv/estados-financieros/ (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- Banco ProCredit. (2023). Financial reports. Available online: https://www.procredit-holding.com/investor-relations/reports-and-publications/financial-reports/ (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- Banco Promerica. (2023). Memoria anual 2023. Available online: https://www.bancopromerica.com/media/512667/memoria-institucional-2023.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- Bancolombia S.A. (2023). Annual results. Available online: https://www.grupobancolombia.com/investor-relations/financial-information/annual-results (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- BBC. (2022, March 27). El Salvador: State of emergency after 62 gang killings in a day. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-60893048 (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- Beck, T., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Levine, R. (2007). Finance, inequality and the poor. Journal of Economic Growth, 12, 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T., & Martinez Peria, M. S. (2010). Foreign bank participation and outreach: Evidence from Mexico. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 19(1), 52–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E., Castaneda, F., Cloke, J., & Taylor, P. (2013). Towards financial geographies of the unbanked: International financial markets, ‘bancarizacion’ and access to financial services in Latin America. The Geographical Journal, 179(3), 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BTI. (2024). Country report 2024 El Salvador. [Bertelsmann stiftung’s transformation index]. Available online: https://bti-project.org/fileadmin/api/content/en/downloads/reports/country_report_2024_SLV.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- CIA. (2024). The world fact book—El Salvador. Available online: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/el-salvador/ (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- Citibank. (2023). Annual reports and proxy statements. Available online: https://www.citigroup.com/global/investors/annual-reports-and-proxy-statements (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- Claessens, S., & Leaven, L. (2004). What drives bank competition? Some international evidence. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 36(3), 563–583. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3838954 (accessed on 10 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, C. E., & Graham, D. H. (1992). Informal finance and financial market integration in El Salvador. Rural finance program—Department of agricultural economics and rural sociology, occasional paper No. 1933 (pp. 1–19). Available online: https://kb.osu.edu/items/9c231af3-5292-52ab-b30e-5fa44d1ec362 (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Culver, D., Alvarado, A., Contreras, E., & Clarke, R. (2024). Critics denounce their government as a dictatorship. But these people say they’ve never felt so free. CNN World. Available online: https://edition.cnn.com/2024/09/12/americas/el-salvador-returners-bukele-crackdown/index.html (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Guiso, L., Paola, S., & Zingales, L. (2004). Does local financial development matter? American Economic Review, 7563, 526–556. Available online: http://www.nber.org/papers/w7563 (accessed on 10 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- IFRC. (2023). El Salvador: Red Cross supports communities before, during and after disasters. Available online: https://www.ifrc.org/article/el-salvador-red-cross-supports-communities-during-and-after-disasters (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- IMF. (2019). IMF policy paper: Building resilience in developing countries vulnerable to large natural disasters (p. 55). IMF Publication. [Google Scholar]

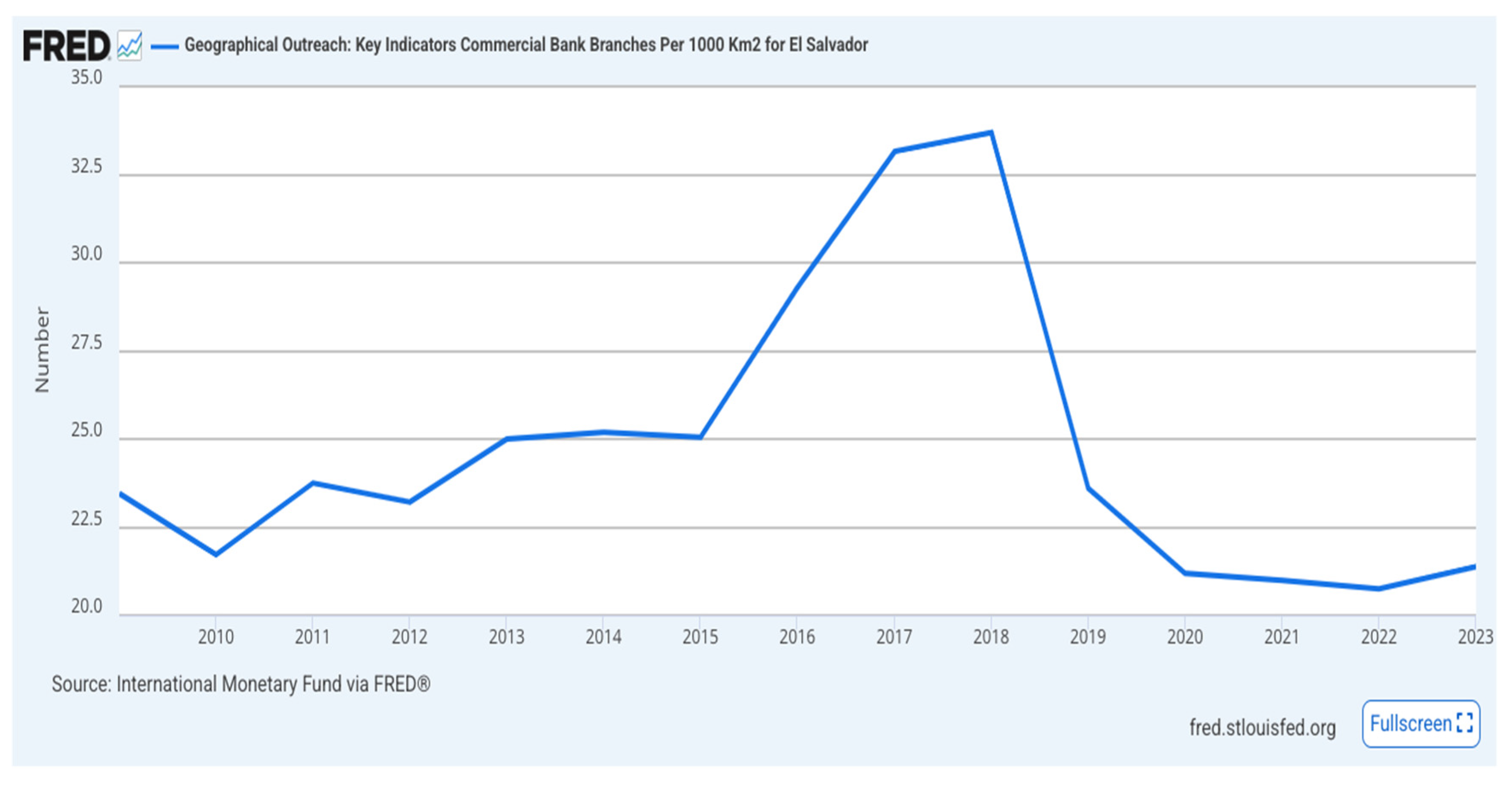

- IMF. (2024). Geographical outreach: Key indicators commercial bank branches per 1000 m2 for El Salvador. International Monetary Fund. Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Available online: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/SLVFCBODCKNUM (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- IOM. (2024). El Salvador Crisis Response Plan 2023–2025. International Organization for Migration. Available online: https://crisisresponse.iom.int/response/el-salvador-crisis-response-plan-2023-2025 (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Krogstrup, S., & Oman, W. (2019). Macroeconomic and financial policies for climate change mitigation: A review of the literature. Working paper of the international monetary fund. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2019/09/04/Macroeconomic-and-Financial-Policies-for-Climate-Change-Mitigation-A-Review-of-the-Literature-48612 (accessed on 3 December 2024).

- Levine, R. (2004). Finance and growth: Theory and evidence. In Handbook of economic growth (pp. 865–934). Working Paper 10766. Available online: http://nber.org/papers/w10766 (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- MAPOG. (2024). GIS data El Salvador. Available online: https://story.mapog.com/app/gisdata/el%20salvador/Financial:%20Bank (accessed on 3 December 2024).

- Mbiti, I., & Weil, D. N. (2015). Mobile banking: The impact of M-Pesa in Kenya. African Successes, Volume III: Modernization and Development, 3, 247–293. Available online: http://www.nber.org/books/afri14-3 (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Morbiato, C. (2023). Detainees in El Salvador’s gang crackdown cite abuse during months in jail. The Associated Press. Available online: https://apnews.com/article/el-salvador-gangs-prison-nayib-bukele-a9e7cae418f5de74837bd666cdeabe98 (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Muth, T. (2022, April 3). One week under State of Exception gang crackdown. El Salvador Perspectives. Available online: https://www.elsalvadorperspectives.com/2022/04/one-week-under-state-of-exception-gang.html (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Ozili, P. K. (2018). Impact of digital finance on financial inclusion and stability. Borsa Istanbul Review, 18(4), 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Privacy Shield. (2024). El Salvador—U.S. banks and local correspondent banks. Available online: https://www.privacyshield.gov/ps/article?id=El-Salvador-US-Banks (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- Rastogi, S., & Ragabiruntha, E. (2018). Financial inclusion and socioeconomic development: Gaps and solutions. International Journal of Social Economics, 45(7), 1122–1140. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/a/eme/ijsepp/ijse-08-2017-0324.html (accessed on 4 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Relief Web. (2001). El Salvador—Earthquakes final fact sheet, fiscal year (FY) 2001. USAID. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/el-salvador/el-salvador-earthquakes-final-fact-sheet-fiscal-year-fy-2001 (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Sadalmelik. (2007). Topographic map of El Salvador. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:El_Salvador_Topography.png (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- Sahay, R., von Allmen, U. E., Lahreche, A., Khera, P., Ogawa, S., Bazarbash, M., & Beaton, K. (2020). The promise of fintech: Financial inclusion in the post COVID-19 era. IMF Departmental Papers. Fintech and COVID-19: Impact, challenges and policy priorities for Asia. Asian Development Bank Institute. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Departmental-Papers-Policy-Papers/Issues/2020/06/29/The-Promise-of-Fintech-Financial-Inclusion-in-the-Post-COVID-19-Era-48623 (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Scotiabank. (2020). Scotiabank completes sale of its operations in El Salvador to Imperia Intercontinental Inc. Available online: https://scotiabank.investorroom.com/index.php?item=3487&s=43 (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- Senyo, P. K., Osabutey, E. L. C., & Seny Kan, K. A. (2021). Pathways to improving financial inclusion through mobile money: A fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis. Information Technology & People, 34(7), 1997–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, C. (2024, February 5). ‘Coolest dictator’ to ‘philosopher king,’ Nayib Bukele’s path to reelection in El Salvador. The Associated Press. Available online: https://apnews.com/article/nayib-bukele-el-salvador-president-0ab3b1d63d3633c535b2cb9b60c56879 (accessed on 5 February 2024).

- Skidmore, M., & Toya, H. (2007). Economic development and the impacts of natural disasters. Economics Letters, 94(1), 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teperek, A. A. (Ed.). (2024a). Geomorphic features of the world’s smallest economies. In Economic development in the world’s smallest economies: How geography, demographics, and culture define economic activity (pp. 36–52). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Teperek, A. A. (Ed.). (2024b). The world’s smallest economies in the background of the world. In Economic development in the world’s smallest economies: How geography, demographics, and culture define economic activity (pp. 16–35). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Teperek, A. A. (Ed.). (2024c). Utilization of water resources in the world’s smallest economies. In Economic development in the world’s smallest economies: How geography, demographics, and culture define economic activity (pp. 1–15). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Vides de Andrade, A. R., de Palomo, A. L., & Martínez, L. C. (2002). Geographical exclusion in rural areas of El Salvador: Its impact on labor market outcomes. IDB Working Paper No. 151. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1814699 (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- World Bank. (2020). Risk > Historical hazards. Climate Knowledge Portal. Available online: https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/country/el-salvador/vulnerability (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- World Bank. (2024). El Salvador. Climate Change Knowledge Portal. Available online: https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/country/el-salvador (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Worldometers. (2024). El Salvador demographics. Worldometers. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/demographics/el-salvador-demographics/ (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Yang, T., & Zhang, X. (2022). FinTech adoption and financial inclusion: Evidence from household consumption in China. Journal of Banking and Finance, 145, 106668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Earthquake | Deaths | Injuries | People Affected | Homes Damaged | Houses Destroyed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January, 2001 | 844 | 4723 | 1,329,806 | 169,632 | 108,226 |

| February, 2001 | 315 | 3399 | 252,622 | 15,706 | 41,302 |

| Total | 1159 | 8122 | 1,582,428 | 185,338 | 149,528 |

| Regions | Branches | ATMs |

|---|---|---|

| Ahuachapan Department | 6 | 4 |

| Cabanas Department | 2 | 0 |

| Chalatenango Department | 2 | 2 |

| Cuscatlan Department | 1 | 3 |

| La Libertad Department | 37 | 29 |

| La Paz Department | 4 | 5 |

| La Union Department | 11 | 1 |

| Morazan Department | 7 | 2 |

| San Miguel Department | 11 | 2 |

| San Salvador Department | 61 | 45 |

| San Vincente Department | 1 | 0 |

| Santa Ana Department | 15 | 2 |

| Sonsonate Department | 8 | 12 |

| Usulutan Department | 12 | 9 |

| Total | 178 | 116 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lundvig Hansen, A.; Lima Santos, L. The Impact of Geographical Factors on the Banking Sector in El Salvador. Int. J. Financial Stud. 2025, 13, 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs13020110

Lundvig Hansen A, Lima Santos L. The Impact of Geographical Factors on the Banking Sector in El Salvador. International Journal of Financial Studies. 2025; 13(2):110. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs13020110

Chicago/Turabian StyleLundvig Hansen, Anders, and Luís Lima Santos. 2025. "The Impact of Geographical Factors on the Banking Sector in El Salvador" International Journal of Financial Studies 13, no. 2: 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs13020110

APA StyleLundvig Hansen, A., & Lima Santos, L. (2025). The Impact of Geographical Factors on the Banking Sector in El Salvador. International Journal of Financial Studies, 13(2), 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs13020110