Abstract

The purpose of this meta-analytical review of experimental studies was to examine the effects of financial literacy and financial behavior on financial well-being. This research was conducted by a master’s in library and information science (MLIS)-trained Information Specialist using the PICO framework. Of the 3089 publications identified, 415 studies were assessed for eligibility, and 9 articles met the inclusion criteria. The meta-analytical review of the selected studies was performed using a two-level model of the MAJOR module for JAMOVI 2020. The potential effect size of the intervention studies was 0.75, indicating the heterogeneity between groups in terms of financial literacy, which rejected the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative hypothesis. The theoretical and practical implications, strengths and limitations, and possibilities for future research were also addressed in this meta-analysis.

1. Introduction

As economies worldwide have dramatically slowed into recession, financial well-being has become a new focus of research attention (). There has also been an increasing amount of financial research on satisfaction, happiness, and cognitive well-being (; ). Financial well-being is widely recognized as a crucial factor driving financial security (), yet its definition varies among different disciplines. The scientific community usually defines financial well-being as a construct with an objective and a subjective side (; ). According to (), the objective side is the total amount of material resources, while the subjective side is self-reported evaluation.

Financial well-being is a comprehensive construct of financial literacy, which affects financial behavior (). However, a clear and unequivocal measure continues to be missing from the literature, in which financial literacy is associated with financial behavior that aims to achieve financial well-being (; ; ). Financial well-being has been theorized as the difference between literacy and behavior, which is defined as a unified, trait-like construct (; ). We argue that even if these three constructs overlap, they do not coincide. This incongruency between studies can be measured using different financial literacy (), financial behavioral changes (), and financial well-being analyses ().

Many studies have been ongoing to investigate the impacts of financial literacy and behavior on financial well-being (; ; ; ; ; ; ). Several studies have been conducted to overcome measures, but some studies have been devoted to analyzing the effects of these interventions using systematic and scientific approaches. Instead, different components have been used to examine the effects of financial satisfaction (; ), subjective financial well-being (), and financial intention () on financial well-being. To explore this significant gap, not only financial well-being and its specific characteristics but also financial literacy and behavior have to be identified and defined (; ; ; ; ; ).

While the conceptualizations of financial literacy and financial behavior, in contrast to financial well-being, are not yet standardized constructs (; ; ; ; ; ), some studies (; ; ) have adopted an integrated approach using both financial behavior and well-being measures. () and () found that financial literacy has a positive effect on financial well-being. Similarly, (), (), and () illustrated that financial literacy positively affects financial behavior.

(), (), (), and () examined intervention studies on reducing financial constraints to promote financial well-being. After reviewing, the investigators found limited data regarding the effects of financial literacy and financial behavior on financial well-being; this suggested that there is a continuing need to examine a range of interventions. A meta-analytical review of intervention studies conducted in financial settings criticized the prior research for lacking internal validity and therefore practical relevance to financial well-being (; ; ; ). Thus, we commenced this meta-analysis to review all published evidence systematically and to quantify the effects of financial literacy and financial behavior on financial well-being.

Research Questions

This meta-analytical review of experimental studies attempts to fill the theoretical gaps regarding the effects of financial literacy and financial behavior on financial well-being. To conduct this meta-analysis, we address the following three constructs: (i) financial literacy, (ii) financial behavior, and (iii) financial well-being. Two research questions are posed, which form the logical foundation of the meta-analysis under scrutiny:

Research question 1: What are the characteristics of financial literacy and financial behavior that affect financial well-being? What heterogeneity can be observed between groups?

Research question 2: Do financial literacy and financial behavior have different effects on financial well-being? What variables explain this heterogeneity in the fixed-effects model?

To answer these questions, we conduct a meta-analytical review of experimental studies that examine the effects of moderators that may explain the variability in effect sizes for these variables. The fixed-effects model is calculated as a weighted average, where the weight assigned to each study is the inverse of that study’s variance. The results offer implications for research and provide insight into the relative effectiveness of the different interventions by focusing on their design characteristics in terms of content and application.

2. Theoretical Lens

2.1. Financial Literacy

The financial literacy concept, introduced by (), is defined as incorporating potential financial knowledge, financial budgeting, financial investment, and financial decision-making. Originally, () developed financial literacy by focusing on financial decision-making, financial skills, financial security, financial strategy, and financial planning. According to () and (), financial literacy can be categorized as financial services, financial products, and financial choices. Previous studies of financial literacy have classified it as managing money, financial self-efficacy, financial numeracy, and financial needs (). Furthermore, some scholars have conceptualized financial literacy as being associated with financial education, financial competency, financial preferences, financial abilities, and financial markets ().

Recently, (), (), and () examined the effects of financial importance, financial capability, and financial outcomes on financial literacy. In addition, researchers have operationalized the positive effects of financial goals, expense management, debt management, risk management, communication skills, and financial resilience on financial literacy (; ; ; ). In the same vein, (), (), (), and () hypothesized that financial numeracy, financial self-efficacy, financial understanding, and financial instrumental support directly affect financial literacy. Therefore, to answer the research questions, our meta-analytical review examines the effects of financial capability, financial numeracy, financial instrumental support, financial education, financial importance, communication skills, and financial planning on financial literacy.

2.2. Financial Behavior

The term “financial behavior” is defined in terms of cognitive psychology (i.e., how people think; in particular, they put too much weight on recent experience) (). Some studies identified that financial behavior is associated with behavioral nudges, financial awareness, saving patterns, and financial habits (; ; ; ). Originally, () developed the financial behavior of self-control, in relation to financial saving, financial spending, financial buying, and financial investing. Similarly, () clarified that financial behavior is connected with logical thinking, rational behavior, organized behavior, and control behavior. We define financial behavior as individual self-control, problem-solving, and decisions on financial management.

The theoretical foundation of financial behavior () is conceptualized as the application of psychology to finance, including social interactions, financial outcomes, and self-acceptation. Previous studies on financial behavior have tended to focus on financial practice, behavioral lifestyle, and rational choices (; ). Likewise, () and () constructed financial behavior as consisting of financial decision-making behavior, cognitive financial behavior, and risk diversification behavior. In our meta-analytical review, we examine the effects of financial practice, financial awareness, financial acceptance, financial readiness, problem-solving and decision-making, and personal financial management on financial behavior.

2.3. Financial Well-Being

Originally, the term “financial well-being” was defined as “how satisfied individuals feel with their finances” (; ). According to (), financial well-being refers to when a person can fully meet ongoing financial obligations while feeling secure with the freedom of financial choice. The key concepts of financial well-being are categorized as both objective and subjective well-being in various studies (; ; ). The first construct is based on objective financial well-being, as aspects of individual needs (good health, materials, etc.). The second construct views subjective financial well-being as the preference satisfaction of individual wants (responses, thoughts, and feelings). () reconceptualized financial well-being as a threefold concept: desired satisfaction with financial freedom, perceived satisfaction with financial freedom, and ability to achieve satisfaction with financial freedom.

Researchers usually theorize financial well-being as comprising quality of life, wealth accumulation, subjective happiness, and life satisfaction (; ; ). Some studies have constructed financial well-being in terms of mental well-being (), cognitive well-being (), psychological well-being (), financial satisfaction (), and subjective happiness (). Research has shown that financial resilience, emotional well-being, and subjective well-being have positive effects on financial well-being (; ; ; ). In our meta-analytical review, we examine the effects of mental financial well-being, coping financial well-being, psychological well-being, emotional financial well-being, financial satisfaction, cognitive financial well-being, subjective happiness, and subjective financial well-being on financial well-being.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

This design utilizes a meta-analytical review that integrates the results of intervention studies (). The design provides insights into quasi-experimental studies with intervention outcomes, using the fixed-effects model. It begins by identifying the effect size, which shows a significant heterogeneity in the common metric. We chose to conduct a meta-analytical review of intervention designs as this can address the within-group effect size, the degree of heterogeneity, and observable heterogeneity. () suggested that a review of intervention studies should focus directly on the outcomes and standardization, using a scale-free statistical effect size model to analyze studies with a fixed-effects model.

This meta-analytical review of intervention studies was conducted using the PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome) framework () to develop our research/practice question: “What interventions can financial researchers use to examine the effects of financial literacy and financial behavior on financial well-being?”. This question’s purpose was to reveal what the meta-analytical review found in general, related to the effects of financial well-being using an intervention approach. In the meta-analysis process, we systematically coded each intervention study, including the mean effect size, the variance in the effect sizes, operationalization of the dependent variables, type of sample, treatment variant, and other measures ().

3.2. Search Strategy

A Master’s in Library and Information Science (MLIS)-trained Information Specialist helped to develop the search terms and conducted the academic literature searches, through a search of the Web of Knowledge, Scopus, ScienceDirect, SAGE Journals, Emerald Insight, Wiley Online Library, Taylor & Francis Online, and Oxford databases, from December 2014 to December 2024. Two filters in this search for intervention studies were used, involving combinations of search strategies. In the first filter, the search terms “experiment”, “controlled”, “manipulated”, “evaluation”, and “intervention” were used; the second filter employed “financial literacy”, “financial behavior”, and “financial well-being”.

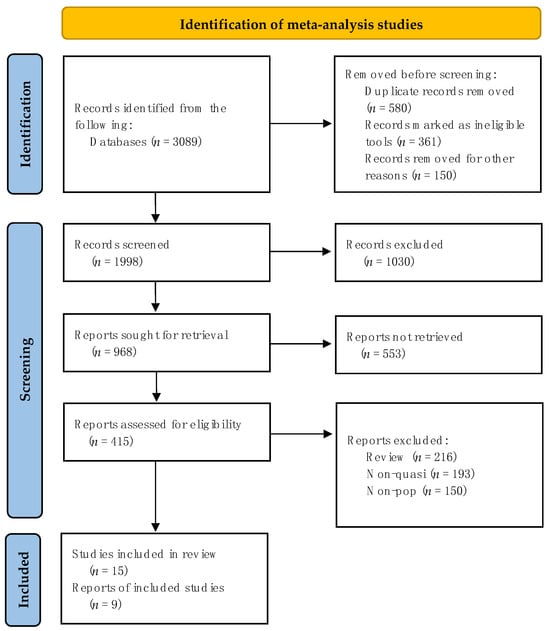

There were three inclusion criteria for the meta-analytical review of intervention studies. First, the included studies were experimental research with a treatment group versus a control group. Second, the intervention studies had significantly different results for variables between groups. Third, the included studies measured the observable variables of financial literacy, financial behavior, and financial well-being. Figure 1 depicts the search strategy for this meta-analytical review ().

Figure 1.

Search strategy.

3.3. Classification and Selection

This paper’s three authors contributed to all steps of classification, selection, and coding. In the first round of selection, we initially identified the titles and abstracts of all publications; these were screened to exclude all publications that did not meet the inclusion criteria (see Table 1). In order to be included in this meta-analysis, studies had to employ an intervention to reduce financial well-being for a non-clinical population. Of the 3089 studies screened, 415 eligible primary articles remained. In the second round, the full-text articles from the initial review were read. We retained only publications that included financial literacy, financial behavior, and financial well-being measures before and after the intervention, as well as those reporting means, standard deviations, and sample sizes. In the third round, 15 studies were selected to be included in the meta-analysis, containing nine effect sizes pertaining to an experimental or quasi-experimental design in the treatment and control groups (see Figure 1). Information on follow-up effects was also gathered, in order to establish whether effects remained stable after the study. The studies included 12 with post-test follow-up effect sizes, of which 9 contained a comparison with a control group.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the meta-analysis.

3.4. Construct Variable Coding

In the following stage, variables were coded for each study: independent variables, dependent variables, sample sizes, and statistical tests. A total of nine effect sizes and significance levels were included in the meta-analytical review of intervention studies. Three types of variables were selected: financial literacy, financial behavior, and financial well-being (see the second table in Section 4.1). All variables were measured under the category of effects: study level, effect size, and variance. The treatment group (sample size, mean, and standard deviation), control group (sample size, mean, and standard deviation), and variance in the studies were assessed. Intercoder reliability was 10%, indicating a reasonable average (k = 0.82 across all variables).

3.5. Outcome Measures

The meta-analytical review of intervention studies examined financial literacy (), financial behavior (), and financial well-being (). Therefore, all included studies evaluated interventions by assessing different populations, demographics, and sample sizes. Additionally, and especially if several components of financial literacy, financial behavior, and financial well-being are trained, it is interesting to see how people improve in applying the treated strategies. Most of the selected studies did not only report results on financial literacy but also on the effects of financial well-being. Thus, three outcome categories were operationally defined for this meta-analytical review: (i) financial literacy, (ii) financial behavior, and (i) financial well-being. Based on the meta-analysis of (), we grouped outcome measures into these three categories that were again sub-divided into several sub-categories, as can be seen in the second and third tables in Section 4.1.

3.6. Interventions

In the included studies, researchers investigated the effects of variables on individuals’ financial literacy, financial behavior, and financial well-being, as can be seen in the second table in Section 4.1. Interventions involved the experimenter manipulating the financial program through role playing, scripts, assessments, and other methods. The targets for intervention included participants’ sex, education, financial literacy, financial behavior, and financial well-being (; ; ; ; ). There was some variability in the length of interventions in the treatment and control groups across the included studies, which were conducted on a weekly basis and/or lasted half an hour.

3.7. Validity Assessment

The three authors evaluated each selected study’s quality independently. The inter-rater agreement rate was 90% in three rounds: identification, screening, and included studies. The eligibility criteria used for quality assessment were based on the methodological index for non-randomized studies (MINORS) score (). Each study was scored from 0 (“poor” quality) to 2 (“good” quality) according to the following criteria: (0) “Was the study described as double blind?”, (1) “Was the method of randomization described in the paper and appropriate?”, and (2) “Was the method of blinding described and appropriate?”. The answer “yes” was given one point, and zero points were given for “no”. The studies scored a maximum of two points if all questions were answered “yes”, as can be seen in the table in Section 4.4.

3.8. Statistical Analyses

The meta-analytical review of intervention studies was performed using the MAJOR module for JAMOVI 2020 (). The JAMOVI program is the Graphical User Interface (GUI) version of R and MAJOR, a commonly used package for metafor (). All data analyses were performed using the Q-test and statistic, where a value of >50% was considered to represent substantial statistical heterogeneity (). The first step of the intervention effect involved obtaining the variation between the treatment and control groups across studies. The mean SR and SD were estimated based on the provided median and IOR; a p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant, and their 95% confidence intervals were obtained.

The second step involved computing the effect size and sample size values of the included variables. All sample sizes were categorized as the number of continuous values per variable, the number of dominants, and the number of subordinates. The heterogeneity of variables was evaluated using the Z, p-value, 95% CI, and tau-square. In the study analyses, mean, SE, SD, and values of 0%, 25%, and 50% indicated no, low, and high heterogeneity (). In the final step, we hypothesized the effects that the variables might have on the heterogeneity/inconsistency of the null and alternative hypotheses.

4. Results

4.1. Summary Effects

The summary effects of the Downs and Black criteria for modifying the score of 27 items of the nine included studies are presented in Table 2. The Downs and Black score ranges in the reported studies were given the following quality levels for the meta-analytical review of the experimental studies (): excellent (26–28), good (20–25), fair (15–19), and poor (≤14) (). The overall included studies showed an uncorrected effect size of 0.65 and corrected effect size of 0.75, with an SD of 0.83 and a 95% CI of [0.89, 2.34]. Table 3 and Table 4 present the included studies’ characteristics and three sets of variables.

Table 2.

Quality assessment criteria of included studies.

Table 3.

Characteristics of intervention studies.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics at the estimate level.

4.2. Intervention Effects

Prior to reporting on each of the intervention studies, the results showed the positive effects of financial literacy and financial behavior on financial well-being. We estimated the mean of the distribution of effects of financial literacy (d = 0.553, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.485, 0.622]) and financial behavior (d = −0.615, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−0.706, −0.525]) on financial well-being (d = −0.103, p < 0.002). To analyze the robustness results, we investigated the treatment and control groups, which showed a positive effect of financial literacy and financial behavior on financial well-being (d = −0.055, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−0.058, −0.052]). Table 5 and Table 6 present the meta-analytical review of the experimental studies across the nine articles and 22 studied variables.

Table 5.

Intervention effect studies.

Table 6.

Interventional effect variables.

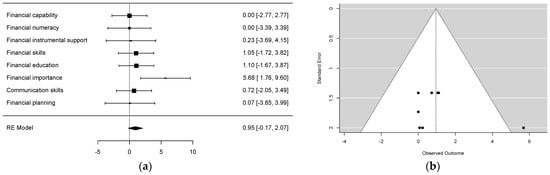

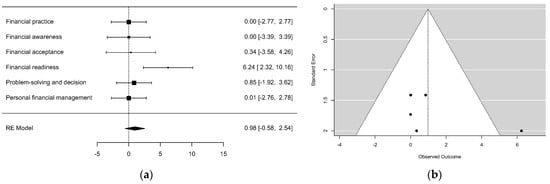

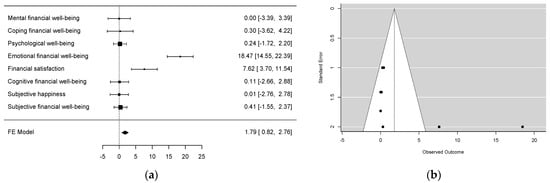

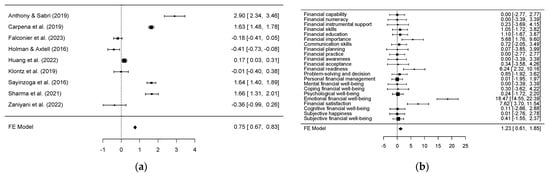

4.3. Fixed-Effects Model

In the first step, this meta-analytical review was performed using the fixed-effects model of the single-variable studies included, as can be seen in Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4. The tests demonstrated that heterogeneity in the estimates of financial literacy was present (k = 8, Tau = 0.002, Q = 6.711, = 60.29%, = 1.000, df = 7.000, p < 0.095, 95% CI [−0.166, 2.066]). The model showed the heterogeneity of financial behavior (k = 6, Tau = 1.076, Q = 8.279, = 70.68%, = 1.443, df = 5.000, p < 0.218, 95% CI [−0.579, 2.541]). The meta-analytical review of elevated financial well-being allowed us to obtain the heterogeneity (k = 8, Tau = 0.000, Q = 86.978, = 91.95%, = 12.425, df = 7.000, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.820, 2.760]). Figure 2 presents forest plots and funnel plots for each variable of the included studies.

Figure 2.

Financial literacy: (a) forest plot; (b) funnel plot.

Figure 3.

Financial behavior: (a) forest plot; (b) funnel plot.

Figure 4.

Financial well-being: (a) forest plot; (b) funnel plot.

In the second step, the fixed-effects model illustrated the overall positive effects of financial literacy, financial behavior, and financial well-being. The results showed an intervention within groups ranging from −0.405 to 2.900, which estimates positive effects (56%). The estimated standardized mean difference of the fixed-effects model (θ = 0.752, 95% CI [0.674, 0.830]) on the model outcomes (Z = 3.90, p < 0.001) was identified. According to the Q-test, the effect outcomes of heterogeneity (Q = 104.50, = 79.91%, p < 0.001) had values larger than ±2.7729, with the funnel plot showing that p < 0.001 and a ranking correlation test result of p = 0.410.

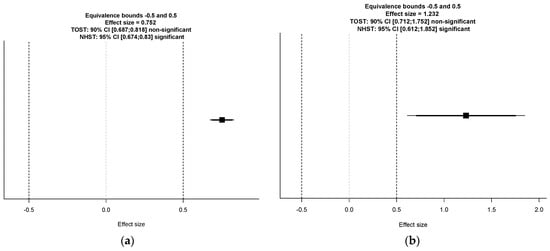

In the third step, the fixed-effects model was used to assess the three included study variables (k = 22, SE = 0.316, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.699, 2.006]), as can be seen in Figure 5 and Figure 6. The heterogeneity of the within-group intervention ( = 80.06%, = 5.157, df = 20.000, Q = 103.147, p < 0.001) in the pooled-effect model displayed fit statistics of maximum-likelihood (log = −82.434, d = 104.504, AIC = 166.868, BIC = 167.959) and restricted maximum-likelihood (log = −81.121, d = 162.242, AIC = 164.242, BIC = 165.287). The two enabled the one-sided testing equivalence of financial literacy, financial behavior, and financial well-being (Z = 5.476, p < 0.001, CI [0.990, 2.314]). The mean effect is about 1.36 (k = 22) = 4.485, p < 0.001; from the results, we reject the null hypothesis but cannot accept the alternative hypothesis.

Figure 5.

Forest plot: (a) included studies (; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ); (b) included variables.

Figure 6.

Equivalence test plot: (a) effect size of included studies; (b) effect size of variables in included studies.

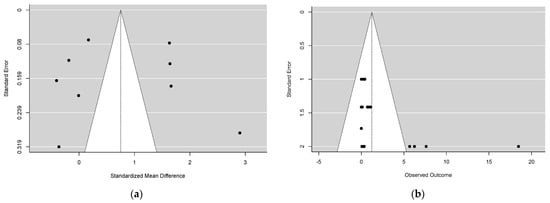

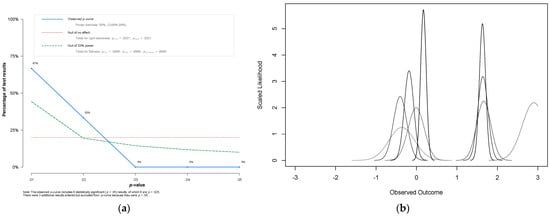

In the fourth step, a funnel plot was used to represent the positive effect of the included studies and variables, which fell symmetrically into a funnel shape, as can be seen in Figure 7 and Figure 8. The model results revealed the standardized mean difference (N = 311.000, v = 0.256, r = 5.139, p < 0.001). The model estimated the power of excess significance (θ = 0.366, min = 0.717, = 0.704, m = 0.942, p = 0.972). The observed p-curve test was performed on the p-uniform (t-test = −1.736, p-value = 0.959) of the fixed-effects model (p-uniform = 1.650, Z = −2.862, p-value = 0.000, 95% CI [0.229, 2.481]). The equivalence test result was significant (Z = −3.080, = 0.05, p = 0.001); this rejects the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative hypothesis.

Figure 7.

Funnel plot of included studies: (a) standardized mean difference in included studies; (b) observed outcome of variable in included studies.

Figure 8.

(a) Observed p-curve of included studies; (b) observed outcomes of included studies.

4.4. Risk of Bias Within Studies

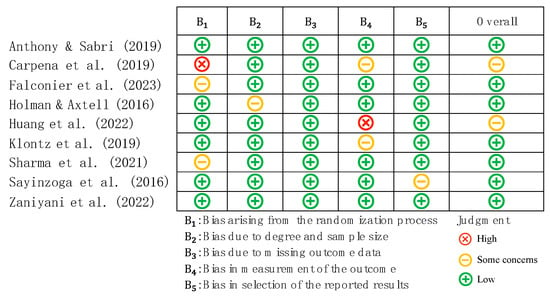

This meta-analytical review assessed the risk of bias in the included studies regarding financial literacy, financial behavior, and financial well-being. The single arm included studies (k = 9) that were assessed using the methodological index for non-randomized studies (MINORS) score (). Each included criterion’s MINORS score ranged from 0 to 2, with a higher score showing a lower risk of bias, as can be seen in Table 7. The included non-comparative studies had a maximum score of 16, while the included comparative studies had a maximum score of 18. Studies with a MINORS score ranging from 10 to 18 points were considered acceptable for this meta-analysis. Table 6 depicts a quality assessment of the nine included studies. Figure 9 presents a risk-of-bias assessment of the included trials.

Table 7.

Quality assessment of included studies.

Figure 9.

Risk-of-bias assessment (; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ).

5. Discussion

5.1. Discussion of Results

The purpose of this meta-analytic review of experimental studies was to estimate the effects of financial literacy and financial behavior on financial well-being. Of these studies, nine studies and 22 variables were examined using a meta-analytic two-level model of the intervention effect and a fixed-effects model. From the intervention effect, we determined the mean of the model distribution (Q = 104.50, = 79.91%, p < 0.001), which demonstrates a positive significant difference within the group. The heterogeneity of the fixed-effects model shows positive significance (k = 22, SE = 0.316, = 80.06%, = 5.157, df = 20.000, Q = 103.1471, p < 0.001, 95%CI [0.990, 2.314]), thus rejecting the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative hypothesis. This result corroborates the effects of financial literacy and financial behavior on financial well-being that were found in previous studies (; ; ; ).

The results of the fixed-effects model showed a positive effect of financial literacy (financial capability, financial numeracy, financial instrumental support, financial skills, financial education, financial importance, communication skills, and financial planning). Closely linked to this meta-analytical review is the type of positive effect, indicating that financial literacy is associated with financial knowledge, numeracy, capability, and skills (; ; ; ). Recent results regarding financial literacy (; ; ) showed positive effects on financial planning, performance, and human capital. This result is unique in identifying financial literacy’s effects on financial technology, inclusion, and instrumental support (; ; ).

The results of the fixed-effects model illustrated the positive effects of financial behavior (financial practice, financial awareness, financial acceptance, financial readiness, problem-solving and decision-making, and personal financial management). Previous studies on financial behavior (; ) have indicated positive effects on the locus of control, financial constraints, and financial risk. These results are consistent with those of four previous meta-analyses (; ; ; ), which found positive effects of financial behavior on financial readiness, awareness, practice, and self-efficacy. According to previous meta-analyses, financial behavior has a positive effect on financial acceptance, self-management, and self-control (; ; ).

Based on the fixed-effects model, the results showed positive effects of financial well-being (mental financial well-being, coping financial well-being, psychological well-being, emotional financial well-being, financial satisfaction, cognitive financial well-being, subjective happiness, and subjective financial well-being). Furthermore, both () and this meta-analytical review demonstrate that financial well-being affects psychological well-being, subjective financial well-being, and financial satisfaction. Various studies, though with a larger scope (; ; ; ), found that financial well-being has a positive effect on cognitive financial well-being and coping financial well-being. Similarly, (), (), and () found positive effects of financial well-being on psychological well-being, emotional financial well-being, and social well-being. Similarly, () and () found that financial well-being has a positive effect on financial satisfaction, financial counseling, and financial happiness.

5.2. Theoretical and Practical Implications

This meta-analytical review of experimental studies has both theoretical and practical implications. The results provide theoretical support to current studies (; ; ; ) on the effects of financial literacy () and financial behavior () on financial well-being (). Previous scholars have theoretically studied these effects using a large-scale sample (; ), quantitative design (), qualitative methods (), a mixed-methods approach (), and systematic review (). Our meta-analyses fill the theoretical gaps regarding the effects of financial literacy and financial behavior on financial well-being by providing valid results obtained using a meta-analytical review of intervention studies.

Through practical research, this meta-analytical review confirms that heterogeneity undermines the significance of the overall results of intervention studies. The fixed-effects model showed the positive effects of the included studies; thus, the null hypothesis cannot be rejected in favor of the alternative. Building on the work of (), (), and (), we extended the practical implications regarding the effects of financial literacy (including aspects such as financial capability, financial numeracy, financial instrumental support, financial skills, financial education, financial importance, communication skills, and financial planning) and financial behavior (financial practice, financial awareness, financial acceptance, financial readiness, problem-solving and decision-making, and personal financial management) on financial well-being (mental financial well-being, coping financial well-being, psychological well-being, emotional financial well-being, financial satisfaction, cognitive financial well-being, subjective happiness, and subjective financial well-being).

5.3. Strengths, Limitations, and Future Research

This meta-analytical review presented a rigorous test of the effects of financial literacy and financial behavior on financial well-being (k = 22, = 80.06%, = 5.157, df = 20.000, Q = 103.147, p < 0.001), and the results reject the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative hypothesis. Although we discussed some of the advantages of meta-analysis, the selected studies, small sample size, and heterogeneity of the methods resulted in reasonable consistency across the included studies. The results of the meta-analyses can provide valuable insights, as they strengthened evidence-based practice regarding common treatment effects across all the included studies.

However, this meta-analytical review has some limitations. First, only nine studies were included for within-group comparison, resulting in a small intervention sample. The second limitation is that it measured only 22 variables, which may not be the traditional manner for testing convergent validity. The third limitation is that, as it analyzed only studies with treatment and control groups, there is still some leeway for subjectivity in the classification. The fourth limitation is that the interpretation of the results should be treated with caution as meta-analyses of experimental studies are known to exhibit biased, statistically significant results that reject the null hypothesis (). The final limitation is that, due to the exclusion of non-experimental research across different populations, the analysis might have overlooked valuable insights from qualitative studies; this potentially limits the comprehensiveness of the meta-analytical findings.

Future research could utilize a mixed-methods matrix (a qualitative study integrating the findings of a quantitative design) to ensure that the findings can be used as existing empirical evidence. Further, due to the instruments used to measure the variables of financial literacy, financial behavior, and financial well-being, other researchers should conduct grounded theory integrated with quasi-experimental research across cultures in order to make accurate assessments. Accordingly, the validity of financial literacy research, and thus the knowledge of the factors that affect financial well-being, can be improved.

6. Concluding Remarks

Based on this meta-analytical review of intervention studies, we can conclude that financial literacy and financial behavior have a positive effect on financial well-being. In answering Research Question 1, we found a positive effect size of 0.75 for the studies, regarding homogeneity between groups (d = −0.055, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−0.058, −0.052]). For Research Question 2, the fixed-effects model showed a positive effect on within-group intervention (k = 22, Z = 5.476, = 80.06%, = 5.157, = 0.05, df = 20.000, Q = 103.147, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.990, 2.314]), which rejected the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative hypothesis. The estimated model illustrated the positive effect of excess significance (N = 311.000, v = 0.256, r = 5.139, θ = 0.366, min = 0.717, = 0.704, m = 0.942, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.229, 2.481]). Based on examining the studies’ quality, intervention type, fixed-effects model, and funnel plot, high-quality studies were assessed for the risk of bias within groups. The analyzed intervention studies focused on financial literacy, especially financial behavior; hence, this analysis brings together the highest-quality financial well-being evidence to ensure the replicability of the findings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.C., H.D. and C.S.; methodology, P.C., H.D. and C.S.; software, P.C., H.D. and C.S.; validation, P.C., H.D. and C.S.; formal analysis, P.C. and H.D.; writing—original draft preparation, P.C. and H.D.; writing—review and editing, P.C. and H.D.; visualization, P.C., H.D. and C.S.; supervision, H.D.; project administration, P.C.; funding acquisition, P.C. and H.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Human Research Ethics Committee of Srinakharinwirot University, based on the Declaration of Helsinki, Belmont Report, International Conference on Harmonization in Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP), International Guidelines for Human Research, and the relevant laws and regulations of Thailand, approved the execution of this research project (Protocol Code: SWUEC-672432).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aguirre, R. A. A., & Aguirre, A. A. A. (2024). Behavioral finance: Evolution from the classical theory and remarks. Journal of Economic Surveys, 38, 452–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahamed, F. T., Houqe, M. N., & van Zijl, T. (2023). Meta-analysis of the impact of financial constraints on firm performance. Accounting & Finance, 63, 1671–1707. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, M., & Shah, S. Z. A. (2020). Overconfidence heuristic-driven bias in investment decision-making and performance: Mediating effects of risk perception and moderating effects of financial literacy. Journal of Economic and Administrative Sciences, 38, 60–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M., & Wu, Q. (2022). Does herding behavior matter in investment management and perceived market efficiency? Evidence from an emerging market. Management Decision, 60, 2148–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anglim, J., Horwood, S., Smillie, L. D., Marrero, R. J., & Wood, J. K. (2020). Predicting psychological and subjective well-being from personality: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 146, 279–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anthony, R., & Sabri, M. F. (2019). The impact of a financial capability program on the financial well-being of medical practitioners. Management, 6, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bapat, D. (2020). Antecedents to responsible financial management behavior among young adults: Moderating role of financial risk tolerance. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 38, 1177–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrafrem, K., Västfjäll, D., & Tinghög, G. (2020). Financial well-being, COVID-19, & the financial better-than-average-effect. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, 28, 100410. [Google Scholar]

- Bashir, I., & Qureshi, I. H. (2023). A systematic literature review on personal financial well-being: The link to key Sustainable Development Goals 2030. FIIB Business Review, 12, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brüggen, E. C., Hogreve, J., Holmlund, M., Kabadayi, S., & Löfgren, M. (2017). Financial well-being: A conceptualization and research agenda. Journal of Business Research, 79, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callis, Z., Gerrans, P., Walker, D. L., & Gignac, G. E. (2023). The association between intelligence and financial literacy: A conceptual and meta-analytic review. Intelligence, 100, 101781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpena, F., Cole, S., Shapiro, J., & Zia, B. (2019). The ABCs of financial education: Experimental evidence on attitudes, behavior, & cognitive biases. Management Science, 65, 346–369. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, E. C., Schönbrodt, F. D., Gervais, W. M., & Hilgard, J. (2019). Correcting for bias in psychology: A comparison of meta-analytic methods. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 2, 115–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, D., Kumar, M., & Dayma, K. K. (2019). Income security, social comparisons and materialism: Determinants of subjective financial well-being among Indian adults. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 37, 1041–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cwynar, A. (2020). Financial literacy, behaviour and well-being of millennials in Poland compared to previous generations: The insights from three large-scale surveys. Review of Economic Perspectives, 20, 289–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ambrosio, C., Jäntti, M., & Lepinteur, A. (2020). Money and happiness: Income, wealth and subjective well-being. Social Indicators Research, 148, 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daovisan, H., & Chamaratana, T. (2020). Financing accumulation for start-up capital: Insights from a qualitative case study of women entrepreneurs in Lao PDR. Journal of Family Business Management, 10, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dare, S. E., van Dijk, W. W., van Dijk, E., van Dillen, L. F., Gallucci, M., & Simonse, O. (2023). How executive functioning and financial self-efficacy predict subjective financial well-being via positive financial behaviors. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 44, 232–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Almeida, F., Ferreira, M. B., Soro, J. C., & Silva, C. S. (2021). Attitudes toward money and control strategies of financial behavior: A comparison between overindebted and non-overindebted consumers. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 566594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Despard, M. (2023). Promoting staff financial well-being in human service organizations: The role of pay, benefits, & working conditions. Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance, 47, 404–421. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E., Scollon, C. N., & Lucas, R. E. (2003). The evolving concept of subjective well-being: The multifaceted nature of happiness. Advances in Cell Aging and Gerontology, 15, 187–219. [Google Scholar]

- Dinesh, T. K., Shetty, A., Dhyani, V. S., Shwetha, T. S., & Dsouza, K. J. (2022). Effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions on well-being and work-related stress in the financial sector: A systematic review and meta-analysis protocol. Systematic Reviews, 11, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittmar, H., Bond, R., Hurst, M., & Kasser, T. (2014). The relationship between materialism and personal well-being: A meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 107, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterlin, R. A. (2001). Subjective well-being and economic analysis: A brief introduction. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 45, 225–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterlin, R. A. (2004). The economics of happiness. Daedalus, 133, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falconier, M. K., Kim, J., & Lachowicz, M. J. (2023). Together–A couples’ program integrating relationship and financial education: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 40, 333–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flather, M. D., Farkouh, M. E., Pogue, J. M., & Yusuf, S. (1997). Strengths and limitations of meta-analysis: Larger studies may be more reliable. Controlled Clinical Trials, 18, 568–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frandsen, T. F., Nielsen, M. F. B., Lindhardt, C. L., & Eriksen, M. B. (2020). Using the full PICO model as a search tool for systematic reviews resulted in lower recall for some PICO elements. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 127, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, J. (2020). Ability or opportunity to act: What shapes financial well-being? World Development, 128, 104843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, M. O. (2021). The effect of financial literacy and gender on retirement planning among young adults. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 39, 1068–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenn, N. M., Scott, L. A., Hokanson, T., Gustafson, K., Stoops, M. A., Day, B., & Nykiforuk, C. I. J. (2021). Community intervention strategies to reduce the impact of financial strain and promote financial well-being: A comprehensive rapid review. Global Health Promotion, 28, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Castro, T. B., & Tovilla-Zárate, C. A. (2014). Meta-analysis: A tool for clinical and experimental research in psychiatry. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 68, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, K., & Kumar, S. (2021). Financial literacy: A systematic review and bibliometric analysis. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 45, 80–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, K. (2018). MAJOR—Meta-analysis. Available online: https://github.com/kylehamilton/MAJOR#major-meta-analysis-jamovi-r (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Higgins, J. P. T., Thompson, S. G., Deeks, J. J., & Altman, D. G. (2003). Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilgert, M. A., Hogarth, J. M., & Beverly, S. G. (2003). Household financial management: The connection between knowledge and behavior. Federal Reserve Bulletin, 89, 309. [Google Scholar]

- Hirshleifer, D. (2015). Behavioral finance. Annual Review of Financial Economics, 7, 133–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, D., & Axtell, C. (2016). Can job redesign interventions influence a broad range of employee outcomes by changing multiple job characteristics? A quasi-experimental study. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 21, 284–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooper, P., Jutai, J. W., Strong, G., & Russell-Minda, E. (2008). Age-related macular degeneration and low-vision rehabilitation: A systematic review. Canadian Journal of Ophthalmology, 43, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J., Sherraden, M. S., Sherraden, M., & Johnson, L. (2022). Experimental effects of child development accounts on financial capability of young mothers. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 43, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huston, S. J. (2010). Measuring financial literacy. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 44, 296–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H., & Park, H. I. (2023). The relationships of financial literacy with both financial behavior and financial well-being: Meta-analyses based on the selective literature review. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 57, 222–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannello, P., Sorgente, A., Lanz, M., & Antonietti, A. (2021). Financial well-being and its relationship with subjective and psychological well-being among emerging adults: Testing the moderating effect of individual differences. Journal of Happiness Studies, 22, 1385–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingale, K. K., & Paluri, R. A. (2022). Financial literacy and financial behaviour: A bibliometric analysis. Review of Behavioral Finance, 14, 130–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, T., & Menkhoff, L. (2020). Financial education in schools: A meta-analysis of experimental studies. Economics of Education Review, 78, 101930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, T., & Menkhoff, L. (2022). Active learning improves financial education: Experimental evidence from Uganda. Journal of Development Economics, 157, 102870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G., & Singh, M. (2024). Pathways to individual financial well-being: Conceptual framework and future research agenda. FIIB Business Review, 13, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G., Singh, M., & Singh, S. (2021). Mapping the literature on financial well-being: A systematic literature review and bibliometric analysis. International Social Science Journal, 71, 217–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klontz, B. T., Zabek, F., Taylor, C., Bivens, A., Horwitz, E., Klontz, P. T., Tharp, D., & Lurtz, M. (2019). The sentimental savings study: Using financial psychology to increase personal savings. Journal of Financial Planning, 32, 44–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P., Pillai, R., Kumar, N., & Tabash, M. I. (2023). The interplay of skills, digital financial literacy, capability, & autonomy in financial decision making and well-being. Borsa Istanbul Review, 23, 169–183. [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey, M. W., & Wilson, D. B. (2001). The way in which intervention studies have “personality” and why it is important to meta-analysis. Evaluation & the Health Professions, 24, 236–254. [Google Scholar]

- Lone, U. M., & Bhat, S. A. (2024). Impact of financial literacy on financial well-being: A mediational role of financial self-efficacy. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 29, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lontchi, C. B., Yang, B., & Shuaib, K. M. (2023). Effect of financial technology on SMEs performance in Cameroon amid COVID-19 recovery: The mediating effect of financial literacy. Sustainability, 15, 2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2011). Financial literacy around the world: An overview. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 10, 497–508. [Google Scholar]

- Lusardi, A., & Streeter, J. L. (2023). Financial literacy and financial well-being: Evidence from the US. Journal of Financial Literacy and Wellbeing, 1, 169–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, A. C., & Kass-Hanna, J. (2021). A methodological overview to defining and measuring “digital” financial literacy. Financial Planning Review, 4, e1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahendru, M. (2021). Financial well-being for a sustainable society: A road less travelled. Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal, 16, 572–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahendru, M., Sharma, G. D., & Hawkins, M. (2022). Toward a new conceptualization of financial well-being. Journal of Public Affairs, 22, e2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, J., Kaiser, C., & Bach-Mortensen, A. M. (2022). A systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of cash transfers on subjective well-being and mental health in low-and middle-income countries. Nature Human Behaviour, 6, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M., Reichelstein, J., Salas, C., & Zia, B. (2015). Can you help someone become financially capable? A meta-analysis of the literature. The World Bank Research Observer, 30, 220–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutlu, Ü., & Özer, G. (2022). The moderator effect of financial literacy on the relationship between locus of control and financial behavior. Kybernetes, 51, 1114–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, A. P., & Banerjee, R. (2021). Consumer’s subjective financial well-being: A systematic review and research agenda. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 45, 750–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngamaba, K. H., Armitage, C., Panagioti, M., & Hodkinson, A. (2020). How closely related are financial satisfaction and subjective well-being? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 85, 101522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noctor, M., Stoney, S., & Stradling, R. (1992). Financial literacy: A discussion of concepts and competences of financial literacy and opportunities for its introduction into young people’s learning. National Foundation for Educational Research. [Google Scholar]

- Ouachani, S., Belhassine, O., & Kammoun, A. (2021). Measuring financial literacy: A literature review. Managerial Finance, 47, 266–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pak, T. -Y., Fan, L., & Chatterjee, S. (2024). Financial socialization and financial well-being in early adulthood: The mediating role of financial capability. Family Relations, 73, 1664–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangestu, S., & Karnadi, E. B. (2020). The effects of financial literacy and materialism on the savings decision of generation Z Indonesians. Cogent Business & Management, 7, 1743618. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, C., She, P. -W., & Lin, M. -K. (2022). Financial literacy and portfolio diversity in China. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 43, 452–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, N. M., & Garman, E. T. (1992). Money as part of a measure of financial well-being. American Behavioral Scientist, 35, 820–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postmus, J. L., Hetling, A., & Hoge, G. L. (2015). Evaluating a financial education curriculum as an intervention to improve financial behaviors and financial well-being of survivors of domestic violence: Results from a longitudinal randomized controlled study. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 49, 250–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M., Isa, C. R., Masud, M. M., Sarker, M., & Chowdhury, N. T. (2021). The role of financial behaviour, financial literacy, and financial stress in explaining the financial well-being of B40 group in Malaysia. Future Business Journal, 7, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remund, D. L. (2010). Financial literacy explicated: The case for a clearer definition in an increasingly complex economy. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 44, 276–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabri, M. F., Anthony, M., Law, S. H., Rahim, H. A., Burhan, N. A. S., & Ithnin, M. (2024). Impact of financial behaviour on financial well-being: Evidence among young adults in Malaysia. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 29, 788–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajid, M., Mushtaq, R., Murtaza, G., Yahiaoui, D., & Pereira, V. (2024). Financial literacy, confidence and well-being: The mediating role of financial behavior. Journal of Business Research, 182, 114791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakuraya, A., Imamura, K., Watanabe, K., Asai, Y., Ando, E., Eguchi, H., Nishida, N., Kobayashi, Y., Arima, H., Iwanaga, M., Otsuka, Y., Sasaki, N., Inoue, A., Inoue, R., Tsuno, K., Hino, A., Shimazu, A., Tsutsumi, A., & Kawakami, N. (2020). What kind of intervention is effective for improving subjective well-being among workers? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 528656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salditt, M., Eckes, T., & Nestler, S. (2024). A tutorial introduction to heterogeneous treatment effect estimation with meta-learners. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 51, 650–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santini, F. D. O., Ladeira, W. J., Mette, F. M. B., & Ponchio, M. C. (2019). The antecedents and consequences of financial literacy: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 37, 1462–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayinzoga, A., Bulte, E. H., & Lensink, R. (2016). Financial literacy and financial behaviour: Experimental evidence from rural Rwanda. The Economic Journal, 126, 1571–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, A. C., Kamau, H. N., Grazioli, F., & Jones, S. K. (2022). Financial profitability of diversified farming systems: A global meta-analysis. Ecological Economics, 201, 107595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S., Arora, K., Chandrashekhar, Sinha, R. K., Akhtar, F., & Mehra, S. (2021). Evaluation of a training program for life skills education and financial literacy to community health workers in India: A quasi-experimental study. BMC Health Services Research, 21, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, L., Rasiah, R., Turner, J. J., Guptan, V., & Nia, H. S. (2022). Psychological beliefs and financial well-being among working adults: The mediating role of financial behaviour. International Journal of Social Economics, 49, 190–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shefrin, H. M., & Thaler, R. H. (1988). The behavioral life-cycle hypothesis. Economic Inquiry, 26, 609–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, S., Xiao, J. J., Barber, B. L., & Lyons, A. C. (2009). Pathways to life success: A conceptual model of financial well-being for young adults. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 30, 708–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slim, K., Nini, E., Forestier, D., Kwiatkowski, F., Panis, Y., & Chipponi, J. (2003). Methodological index for non-randomized studies (minors): Development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ Journal of Surgery, 73, 712–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, T. D. (2001). Wheat from chaff: Meta-analysis as quantitative literature review. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 15, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, T. D., & Doucouliagos, H. (2015). Neither fixed nor random: Weighted least squares meta-analysis. Statistics in Medicine, 34, 2116–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statman, M. (2014). Behavioral finance: Finance with normal people. Borsa Istanbul Review, 14, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strömbäck, C., Skagerlund, K., Västfjäll, D., & Tinghög, G. (2020). Subjective self-control but not objective measures of executive functions predicts financial behavior and well-being. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, 27, 100339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, M. S., Ahmed, A. D., & Richards, D. W. (2021). Financial literacy and financial well-being of Australian consumers: A moderated mediation model of impulsivity and financial capability. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 39, 1377–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A., & Gupta, V. (2021). Social capital theory, social exchange theory, social cognitive theory, financial literacy, & the role of knowledge sharing as a moderator in enhancing financial well-being: From bibliometric analysis to a conceptual framework model. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 664638. [Google Scholar]

- Utkarsh, A. P., Ashta, A., Spiegelman, E., & Sutan, A. (2020). Catch them young: Impact of financial socialization, financial literacy and attitude towards money on financial well-being of young adults. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 44, 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Nguyen, H., Ha, G. H., Nguyen, D. N., Doan, A. H., & Phan, H. T. (2022). Understanding financial literacy and associated factors among adult population in a low-middle income country. Heliyon, 8, e09638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viechtbauer, W. (2010). Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. Journal of Statistical Software, 36, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlaev, I., & Elliott, A. (2014). Financial well-being components. Social Indicators Research, 118, 1103–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vörös, Z., Szabó, Z., Kehl, D., Kovács, O. B., Papp, T., & Schepp, Z. (2021). The forms of financial literacy overconfidence and their role in financial well-being. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 45, 1292–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widyastuti, M., & Hermanto, Y. B. (2022). The effect of financial literacy and social media on micro capital through financial technology in the creative industry sector in East Java. Cogent Economics & Finance, 10, 2087647. [Google Scholar]

- Zaniyani, T. N., Taherinia, M., Dehkordi, D. J., & Givaki, E. (2022). The effectiveness of acceptance and commitment group financial therapy on financial literacy, personal financial management and mental accounting. International Journal of Finance & Managerial Accounting, 7, 227–239. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).