The Relationship between Financial Literacy Misestimation and Misplacement from the Perspective of Inverse Differential Information and Stock Market Participation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature and Hypotheses

2.1. Overconfidence in Social Comparisons

2.2. Inverse Differential Information Hypothesis

2.3. Correlation between Misestimation and Misplacement and Stock Market Participation

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Definitions of Measurement Variables

3.3. Methods

4. Results

4.1. Basic Statistics

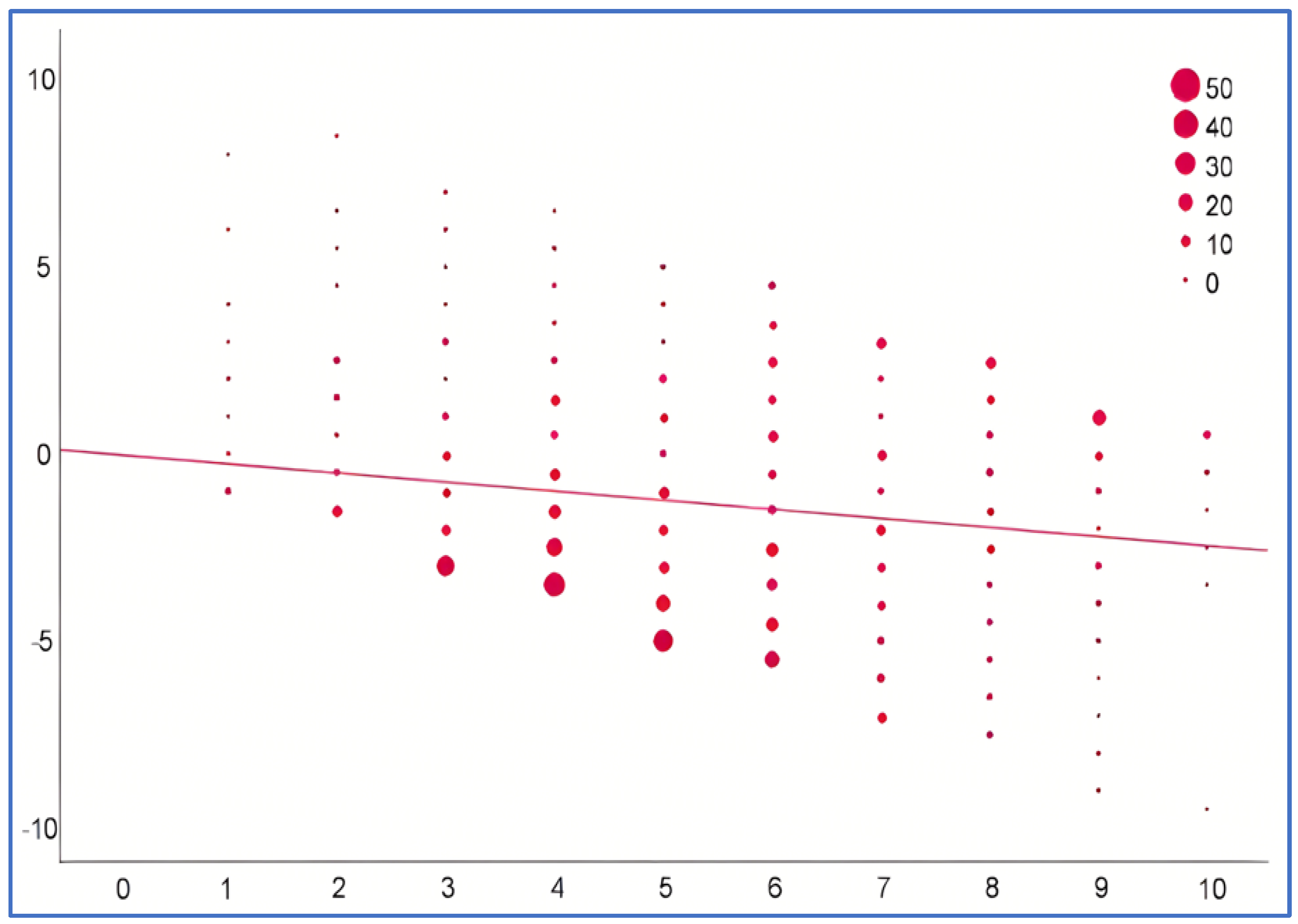

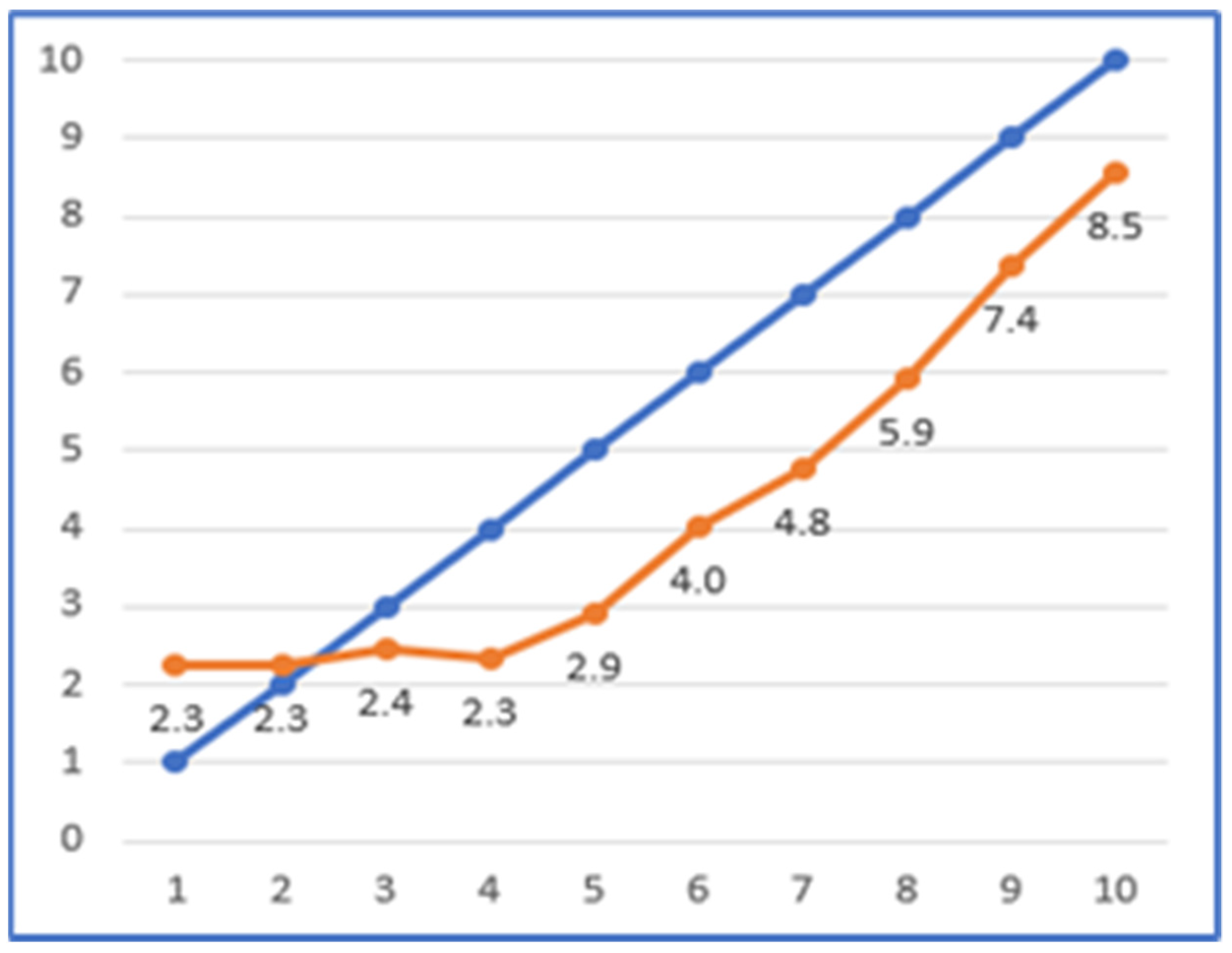

4.2. Test of Hypothesis 1

4.3. Test of Hypothesis 2

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | See Gerber et al. (2018) for a discussion of social comparison when an individual intentionally selects his or her own comparison target. |

| 2 | Although numerical representations of probabilities are generally considered to be accurate, free of misunderstanding, and capable of calculating expectations, some people find verbal representations of probabilities more natural and others find numerical representations of probabilities to be rejected or awkward (Wallsten et al. 1993a, 1993b). Wallsten et al. (1993b) concluded that a limited number of verbal and numerical representations of probability correspond well to each other as long as both ends of the probability representation are accurate, and that neither is superior to the other. In this paper, the two extremes “I don’t know at all”, and “definitely certainly” correspond to the probability values of 1/4 and 1, respectively. |

References

- Agarwal, Sumit, John C. Driscoll, and David Laibson. 2009. The Age of Reason: Financial Decisions over the Life-Cycle with Implications for Regulation. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2: 51–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alicke, Mark D. 1985. Global Self-Evaluation as Determined by the Desirability and Controllability of Trait Adjectives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 49: 1621–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alicke, Mark D., and Constantine Sedikides. 2009. Self-Enhancement and Self-Protection: What They Are and What They Do. European Review of Social Psychology 20: 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allgood, Sam, and William B. Walstad. 2015. The Effects of Perceived and Actual Financial Literacy on Financial Behaviors. Economic Inquiry 54: 675–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Anders, Forest Baker, and David T. Robinson. 2017. Precautionary Savings, Retirement Planning and Misperceptions of Financial Literacy. Journal of Financial Economics 126: 383–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Cameron, Michael W. Kraus, Adam D. Galinsky, and Dacher Keltner. 2012. The Local-ladder Effect: Social Status and Subjective Well-being. Psychological Science 23: 764–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkes, Hal A., Caryn Christensen, Cheryl Lai, and Catherine Blumer. 1987. Two Methods of Reducing Overconfidence. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 39: 133–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrondel, Luc. 2018. Financial Literacy and Asset Behavior: Poor Education and Zero for Conduct? Comparative Economic Studies 60: 144–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, Adele, Flore-Anne Messy, Lila Rabinivich, and Joanne Yoong. 2015. Financial Education for Long-Term Savings and Investments: Review of Research and Literature. OECD Working Papers on Finance, Insurance and Private Pensions. Paris: OECD. [Google Scholar]

- Balcetis, Emily, and David Dunning. 2013. Considering the Situation: Why People are Better Social Psychologists than Self-psychologists. Self and Identity 12: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvet, Laurent E., John Y. Campbell, and Paolo Sodini. 2009. Measuring the Financial Sophistication of Households. American Economic Review 99: 393–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, John Y. 2006. Household Finance, NBER Working Paper 12149. Oxford: National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, John R., and Paul D. Windschitl. 2004. Biases in Social Comparative Judgments: The Role of Nonmotivated Factors in Above-Average and Comparative-Optimism Effects. Psychological Bulletin 130: 813–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Bingzheng, and Ze Chen. 2023. Financial Literacy Confidence and Retirement Planning: Evidence from China. Risks 11: 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Claudia E. 1981. Person Categories and Social Perception: Testing Some Boundaries of the Processing Effects of Prior Knowledge. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 40: 441–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crusius, Jan, Katja Corcoran, and Thomas Mussweiler. 2022. Social Comparison: A Review of Theory, Research, and Applications. In Theories in Social Psychology, 2nd ed. Edited by Derek Chadee. Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons Ltd., chp. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Cwynar, Andrej, Wiktor Cwynar, Wiktor Patena, and Welcome Sibanda. 2020. Young Adults’ Financial Literacy and Overconfidence Bias in Debt Markets. International Journal of Business Performance Management 21: 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deaves, Richard, Erik Lüders, and Guo Ying Luo. 2009. An Experimental Test of the Impact of Overconfidence and Gender on Trading Activity. Review of Finance 13: 555–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, Ward. 1968. Conservatism in Human Information Processing. In Formal Representation of Human Judgment. Edited by Benjamin Kleinmuntz. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 17–52. [Google Scholar]

- Engeler, Isabelle, and Gerald Häubl. 2020. Miscalibration in Predicting One’s Performance: Disentangling Misplacement and Misestimation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 120: 940–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epley, Nicholas, and David Dunning. 2001. Feeling “Holier than Thou”: Are Self-Serving Assessments produced by Errors in Self-or Social Prediction? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 79: 861–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epley, Nicholas, and David Dunning. 2006. The Mixed Blessing of Self-Knowledge in Behavioral Prediction: Enhanced Discrimination but Exacerbated Bias. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 32: 641–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erev, Ido, Thomas S. Wallsten, and David V. Budescu. 1994. Simultaneous Over- and Underconfidence: The Role of Error in Judgment Processes. Psychological Review 101: 519–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festinger, Leon. 1954. A Theory of Social Comparison Process. Human Relations 7: 117–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festinger, Leon. 1957. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fiedler, Klaus, and Christian Unkelbach. 2014. Regressive Judgment: Implications of a Universal Property of the Empirical World. Current Directions in Psychological Science 23: 361–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishhoff, Baruch, Wändi Bruine de Bruin, Andrew M. Parker, Susan G. Milstein, and Bonnie L. Halpern-Felsher. 2010. Adolescents’ Perceived Risk of Dying. Journal of Adolescent Health 46: 265–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, Jonathan P., Ladd Wheeler, and Jerry Suls. 2018. A Social Comparison Theory Meta-Analysis 60+ Years On. Psychological Bulletin 144: 177–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, Markus, and Martin Weber. 2007. Overconfidence and Trading Volume. Geneva Risk and Insurance Review 32: 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goethals, George R., David M. Messick, and Scott T. Allison. 1991. The Uniqueness Bias: Studies of Constructive Social Comparison. In Social Comparison: Contemporary Theory and Research. Edited by Jerry Suls and Thomas Ashby Wils. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 149–76. [Google Scholar]

- Grežo, Matúš. 2021. Overconfidence and Financial Decision-making: A Meta-analysis. Review of Behavioral Finance 13: 276–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadar, Liat, Sanjay Sood, and Craig R. Fox. 2013. Subjective Knowledge in Consumer Financial Decisions. Journal of Marketing Research 50: 303–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakmiller, Karl L. 1966. Threat as a Determinant of Downward Comparison. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology Supplement 1: 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haliassos, Michael, and Carol C. Bertaut. 1995. Why do So Few Hold Stocks? Economic Journal 105: 1110–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helzer, Erik G., and David Dunning. 2012. Why and When Peer Prediction Is Superior to Self-Prediction: The Weight Given to Future Aspiration Versus Past Achievement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 103: 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Harrison, Jeffrey D. Kubik, and Jeremy C. Stein. 2004. Social Interaction and Stock-Market Participation. Journal of Finance 59: 137–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huttenlocher, Janellen, Larry V. Hedges, and Susan Duncan. 1991. Categories and Particulars: Prototype Effects in Estimating Spatial Location. Psychological Review 98: 352–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingelbrecht, Koen, and Mariachiara Tedde. 2024. Overconfidence, Financial Literacy, and Excessive Trading. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 219: 152–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IOSCO, and OECD. 2018. The Application of Behavioural Insights to Financial Literacy and Investor Education Programmes and Initiatives. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/finance-and-investment/the-application-of-behavioural-insights-to-financial-literacy-and-investor-education-programmes-and-initiatives_0b5f985d-en (accessed on 9 June 2024).

- Karki, Uttam, Vaneet Bhatia, and Dheeraj Sharma. 2024. A Systematic Literature Review on Overconfidence and Related Biases Influencing Investment Decision Making. Economic and Business Review 26: 130–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaustia, Markku, Andrew Conlin, and Niilo Luotonen. 2023. What Drives Stock Market Participation? The Role of Institutional, Traditional, and Behavioral Factors. Journal of Banking and Finance 148: 106743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klar, Yechiel, and Eilath E. Giladi. 1999. Are Most People Happier than Their Peers, or Are They Just Happy? Personality and Social Psychology 25: 585–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, Maec M. 2016. Financial Literacy, Confidence and Financial Seeking. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 131: 198–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, Joachim, and Ross A. Mueller. 2002. Unskilled, Unaware, or Both? The Better-than-average Heuristic and Statistical Regression Predict Errors in Estimates of Own Performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 82: 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruger, Justin. 1999. Lake Wobegen Be Gone! The “Below-Average Effect” and the Egocentric Nature of Comparative Ability Judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 77: 221–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, Justin, and Jeremy Burrus. 2004. Egocentrism and Focalism in Unrealistic Optimism (and Pessimism). Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 40: 332–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunda, Ziva. 1990. The Case of Motivated Reasoning. Psychological Bulletin 108: 480–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrick, Richard P., Katherine A. Burson, and Jack B. Soll. 2007. Social Comparison and Confidence: When Thinking You’re Better than Average Predicts Overconfidence (and When It Does Not). Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 102: 76–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, David R. 2018. The Perils of Overconfidence: Why Many Consumers Fail to Seek Advice When They Really Should. Journal of Financial Service Marketing 23: 104–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, Sarah, Baruch Fishhoff, and Lawrence D. Phillips. 1982. Calibration of Probabilities: The State of the Art to 1980. In Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases. Edited by Daniel Kahneman, Paul Slovic and Amos Tversky. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 306–34. [Google Scholar]

- Logg, Jennifer M., Uriel Haran, and Don A. Moore. 2018. Is Overconfidence a Motivated Bias? Experimental Evidence. Journal of Experimental Psychology 147: 1445–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, Annamaria, and Olivia S. Mitchell. 2007. Financial Literacy and Retirement Preparedness: Evidence and Implications for Financial Education Programs. CFS Working Paper Series, No. 2007/15; Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Lusardi, Annamaria, and Olivia S. Mitchell. 2014. The Economic Importance of Financial Literacy: Theory and Evidence. Journal of Economic Literature 52: 5–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabe, Paul A., and Stephen G. West. 1982. Validity of Self-Evaluation of Ability: A Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology 67: 280–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmendier, Ulrike, and Timothy Taylor. 2015. On the Verges of Overconfidence. Journal of Economic Perspectives 29: 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkle, Christoph. 2017. Financial Overconfidence over Time: Foresight, Hindsight, and Insight of Investors. Journal of Banking and Finance 84: 68–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, Bruce D. 1995. Natural and Quasi-Experiments in Economics. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics 13: 151–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Don A., and Deborah Small. 2007. Error and Bias in Comparative Judgment: On Being Both Better and Worse Than We Think We Are. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 92: 972–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Don A., and Paul J. Healy. 2008. The Trouble with Overconfidence. Psychological Review 115: 502–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oskamp, Stuart. 1962. The Relationship of Clinical Experience and Training Methods to Several Criteria of Clinical Prediction. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied 76: 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikulina, Elena, Luc Renneboog, and Phillippe N. Tobler. 2017. Overconfidence and Investment: An Experimental Approach. Journal of Corporate Finance 43: 175–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porto, Nilton, and Jing Jian Xiao. 2016. Financial Literacy Overconfidence and Financial Advice Seeking. Journal of Financial Service Professionals 70: 78–88. [Google Scholar]

- Pronin, Emily. 2008. How We See Ourselves and How We See Others. Science 320: 1177–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shadish, William R., Thomas D. Cook, and Donald T. Campbell. 2002. Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Generalized Causal Inference. Boston: Hough Mifflin Company. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, Dharmendra, Garima Malik, Prateek Jain, and Mahmoud Abouraia. 2024. A systematic review and research agenda on the causes and consequences of financial overconfidence. Cogent Economics and Finance 12: 2348543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolper, Oscar A., and Andreas Walter. 2017. Financial Literacy, Financial Advice, and Financial Behavior. Journal of Business Economics 87: 581–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suschen, Michael, Susanne Kollmann, Minou Seitz, Gunnar Mau, and Manuel Froitzheim. 2022. Financial Literacy of Adults in Germany FILSA Study Results. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 15: 488. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Shelley E., and Jonathan D. Brown. 1988. Illusion and Well-Being: A Social Psychological Perspective on Mental Health. Psychological Bulletin 103: 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Rooij, Maarten C. J., Annamaria Lusardi, and Rob J. M. Alessie. 2011. Financial Literacy and Stock Market Participation. Journal of Financial Economics 101: 449–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rooij, Maarten C. J., Annamaria Lusardi, and Rob J. M. Alessie. 2012. Financial Literacy, Retirement Planning and Household Wealth. Economic Journal 122: 449–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viscussi, W. K. 1990. Do Smokers Underestimate Risks? Journal of Political Economy 98: 1253–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vörös, Zósfia, Zoltán Szabó, Dániel Kehl, Olivér Béla Kovács, Tamás Papp, and Zoltán Schepp. 2021. The Forms of Financial Literacy Overconfidence and Their Role in Financial Well-being. International Journal of Consumer Studies 45: 1292–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallsten, Thomas S., David V. Budescu, and Rami Zwick. 1993a. Comparing the Calibration and Coherence of Numerical and Verbal Probability Judgments. Management Science 39: 176–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallsten, Thomas S., David V. Budescu, Rami Zwick, and Steven M. Kemp. 1993b. Preferences and Reasons for Communicating Probabilistic Information in Verbal or Numerical Terms. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society 31: 135–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, Neil D. 1980. Unrealistic Optimism about Future Life Events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 39: 806–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, Neil D., and Elizabeth Lachendro. 1982. Egocentrism as a Source of Unrealistic Optimism. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 8: 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Timothy D., and Elizabeth Dunn. 2004. Self-Knowledge: Its Limits, Value, and Potential Improvement. Annual Review of Psychology 55: 493–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windschitl, Paul D., Jason P. Rose, Michael T. Stalkfleet, and Andrew R. Smith. 2008. Are People Excessive or Judicious in Their Egocentrism? A Modeling Approach to Understanding Bias and Accuracy in People’s Optimism within Competitive Contexts. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 95: 253–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Xia, Tian, Zhengwei Wang, and Kunpeng Li. 2014. Financial Literacy Overconfidence and Stock Market Participation. Social Indicators Research 119: 1233–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Xiaolan, and Li Zhu. 2016. Ambiguity vs. Risk: An Experimental Study of Overconfidence, Gender, and Trading Activity. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance 9: 125–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, Tsung-Ming, and Yue Ling. 2022. Confidence in Financial Literacy, Stock Market Participation, and Retirement Planning. Journal of Family and Economic Issues 43: 169–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoong, Joanne. 2011. Financial Illiteracy and Stock Market Participation: Evidence from the RAND American Life Panel. In Financial Literacy: Implications for Retirement Security and the Financial Marketplace. Edited by Olivia S. Mitchell and Annamaria Lusardi. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 76–100. [Google Scholar]

- Zell, Ethan, and Zlatan Krizan. 2014. Do People Have Insight into Their Abilities? A Metasynthesis. Perspectives on Psychological Science 9: 111–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Min. | Max. | Average | Median | Mode | S. D. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actual Score | 1 | 10 | 5.55 | 6 | 6 | 2.09 |

| Predicted score | 0 | 10 | 3.92 | 3 | 0 | 3.34 |

| Misestimation | −10 | 8 | −1.63 | −2 | −3 | 2.98 |

| Actual Score Group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LTM | MDL | HTM | ||

| Comparison belief | WTA | 2.53, 1.87, −0.66 (0.75, 2.74, 2.80) | 5.32, 2.66, −2.66 (1.08, 2.80, 2.74) | 8.32, 4.43, −3.89 (0.53, 2.82, 2.93) |

| AVRG | 2.49, 2.30, −0.19 (0.63, 2.56, 2.63) | 5.44, 3.49, −1.95 (1.06, 3.02, 2.92) | 8.55, 6.44, −2.11 (0.66, 3.16, 3.07) | |

| BTA | 2.29, 4.11, 1.82 (0.85, 2.78, 1.97) | 5.61, 4.60, −1.00 (1.15, 3.08, 2.77) | 8.81, 8.63, −0.18 (0.74, 2.17, 2.06) | |

| Total | 2.48, 2.37, −0.12 (0.69, 2.69, 2.75) | 5.44, 3.46, −1.97 (1.08, 3.03, 2.90) | 8.58, 6.75, −1.84 (0.68, 3.17, 3.04) |

| Interaction | Misestimation | Misplacement | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | Median | S. D. | Mean | Mean | |

| LTM | 172 | −0.10 | −4 | 10.74 | −0.12 | 3.83 |

| MDL | 633 | −5.47 | −6 | 8.55 | −1.97 | 2.92 |

| HTM | 197 | −3.00 | −2 | 5.91 | −1.84 | 2.13 |

| Total | 1002 | −4.06 | −6 | 8.77 | −1.63 | 2.92 |

| Target (N) | Actual Score | Misestimation | Misplacement |

|---|---|---|---|

| LTM (172) | −0.22 ** | 0.99 ** | 0.18 * |

| MDL (633) | −0.06 | 0.97 ** | −0.02 |

| HTM (197) | 0.05 | 0.93 ** | 0.33 ** |

| Total (1002) | −0.11 ** | 0.95 ** | 0.07 * |

| N | Actual Score (A) | Pred. Score | Misestimation (M) | M/A | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strong overplacement | 17 | 2.29 (0.85) | 4.12 (2.78) | 1.82 (2.72) | 0.79 |

| Weak overplacement | 197 | 3.90 (1.80) | 3.34 (3.03) | −0.55 (2.72) | −0.14 |

| Exact placement | 512 | 5.58 (1.77) | 3.97 (3.41) | −1.62 (2.89) | −0.29 |

| Weak underplacement | 239 | 6.64 (1.84) | 4.21 (3.49) | −2.43 (2.88) | −0.36 |

| Strong underplacement | 37 | 8.32 (0.53) | 4.43 (2.82) | −3.89 (2.93) | −0.46 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | t | B | t | |

| Constant | −1.615 | −12.800 *** | −1.680 | −4.895 *** |

| Strong overplacement | 0.688 | 4.885 *** | 0.604 | 4.352 *** |

| Weak overplacement | 0.265 | 4.436 *** | 0.223 | 3.658 *** |

| Weak underplacement | −0.410 | −3.665 *** | −0.365 | −3.277 ** |

| Strong underplacement | −2.277 | −4.684 *** | −1.939 | −3.958 *** |

| Actual score | −0.195 | −3.714 *** | ||

| Control variables | Not included | Included | ||

| Model Fit, Explanatory Power | F = 23.8 (p = 0.000), adj. R square = 0.083. | F = 15.8 (p = 0.000), adj. R square = 0.172. | ||

| Variable | Item | N | Ratio of Experience | S. D. | F(p) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| actual score group | LTM | 172 | 0.25 | 0.43 | 26.931(0.000) |

| MDL | 633 | 0.34 | 0.47 | ||

| HTM | 197 | 0.58 | 0.49 | ||

| placement group | overplacement | 276 | 0.40 | 0.49 | 1.251(0.287) |

| exact placement | 512 | 0.35 | 0.48 | ||

| underplacement | 214 | 0.40 | 0.49 | ||

| Sex | Male | 533 | 0.45 | 0.50 | 26.783(0.000) |

| Female | 469 | 0.29 | 0.45 | ||

| Age group | 20s | 506 | 0.21 | 0.41 | 31.718(0.000) |

| 30s | 184 | 0.54 | 0.50 | ||

| 40s | 138 | 0.50 | 0.50 | ||

| 50s | 123 | 0.55 | 0.50 | ||

| 60s or older | 51 | 0.59 | 0.50 | ||

| Marriage | Married | 382 | 0.54 | 0.499 | 80.958(0.000) |

| Unmarried | 620 | 0.27 | 0.444 | ||

| Household income level | Below median income | 317 | 0.25 | 0.435 | 19.773(0.000) |

| Around median income | 288 | 0.39 | 0.488 | ||

| Above median income | 349 | 0.50 | 0.501 | ||

| I do not know income | 48 | 0.15 | 0.357 | ||

| Stock participation of family member | Yes | 325 | 0.59 | 0.492 | 107.532(0.000) |

| No | 677 | 0.27 | 0.444 | ||

| Total | 1002 | 0.37 | 0.484 |

| Model 1a | Model 1b | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Wald | Exp(B) | B | Wald | Exp(B) | |

| Actual score | 0.281 | 34.728 | 1.324 *** | 0.280 | 34.473 | 1.323 *** |

| Misestimation | 0.108 | 15.989 | 1.114 *** | - | - | - |

| Overplacement | 0.231 | 10.251 | 1.260 ** | 0.234 | 10.466 | 1.264 ** |

| Underplacement | −0.234 | 1.404 | 0.791 | −0.339 | 2.987 | 0.712 † |

| Interaction | - | - | - | 0.034 | 14.581 | 1.035 *** |

| Sex (Male) | 0.448 | 7.593 | 1.565 ** | 0.459 | 7.995 | 1.582 ** |

| Marriage (Married) | 0.091 | 0.153 | 1.096 | 0.111 | 0.226 | 1.117 |

| Age group (30s) | 1.205 | 23.777 | 3.335 *** | 1.209 | 24.005 | 3.349 *** |

| Age group (40s) | 0.989 | 11.713 | 2.687 ** | 0.964 | 11.133 | 2.623 ** |

| Age group (50s) | 1.292 | 17.249 | 3.641 *** | 1.273 | 16.750 | 3.572 *** |

| Age group (60s or older) | 1.231 | 9.114 | 3.425 ** | 1.250 | 9.393 | 3.489 ** |

| Below median income | −0.600 | 8.537 | 0.549 ** | −0.602 | 8.581 | 0.548 ** |

| Above median income | 0.081 | 0.183 | 1.085 | 0.088 | 0.215 | 1.092 |

| I do not know income | −0.393 | 0.746 | 0.675 | −0.375 | 0.681 | 0.687 |

| Experience of family member | 1.231 | 99.018 | 3.424 *** | 1.237 | 56.499 | 3.445 *** |

| Constant | −3.219 | 110.857 | 0.062 *** | −3.019 | 100.020 | 0.039 *** |

| N, Explanatory Power | N = 1002. pseudo R square = 0.355. | N = 1002. pseudo R square = 0.295. | ||||

| Model 2a | Model 2b | Model 3a | Model 3b | Model 4a | Model 4b | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Exp(B) | B | Exp(B) | B | Exp(B) | B | Exp(B) | B | Exp(B) | B | Exp(B) | |

| Actual score | 0.340 | 1.404 | 0.358 | 1.431 | 0.304 | 1.356 ** | 0.304 | 1.355 ** | 0.344 | 1.410 | 0.329 | 1.390 |

| Misestimation | 0.228 | 1.256 ** | - | - | 0.061 | 1.063 † | - | - | 0.181 | 1.198 ** | - | - |

| Overplacement | −0.042 | 0.986 | −0.074 | 0.976 | 1.037 | 2.821 *** | 1.060 | 2.888 *** | - | - | - | - |

| Underplacement | - | - | - | - | 0.054 | 1.056 | 0.007 | 1.077 | −0.773 | 0.462 † | −0.921 | 0.398 * |

| Interaction | - | - | 0.062 | 1.064 ** | - | - | 0.021 | 1.022 † | - | - | 0.075 | 1.078 * |

| Sex (Male) | 0.748 | 2.114 | 0.716 | 2.046 | 0.445 | 1.561 * | 0.441 | 1.554 * | 0.500 | 1.649 | 0.563 | 1.756 |

| Marriage (Married) | −0.184 | 0.832 | −0.194 | 0.824 | 0.013 | 1.013 | 0.024 | 1.025 | 0.477 | 1.611 | 0.515 | 1.674 |

| Age group (30s) | 1.328 | 3.772 † | 1.347 | 3.846 † | 1.283 | 3.608 *** | 1.274 | 3.576 *** | 1.146 | 3.146 * | 1.171 | 3.225 * |

| Age group (40s) | 0.417 | 1.518 | 0.413 | 1.511 | 1.006 | 2.734 ** | 0.991 | 2.694 ** | 1.222 | 3.395 † | 1.145 | 3.142 † |

| Age group (50s) | 1.378 | 3.966 † | 1.373 | 3.949 † | 1.532 | 4.627 *** | 1.518 | 4.561 *** | 0.736 | 2.088 | 0.671 | 1.956 |

| Age group (60s+) | 1.902 | 6.696 | 1.980 | 7.244 | 1.674 | 5.332 ** | 1.674 | 5.333 ** | 0.024 | 1.025 | 0.024 | 1.025 |

| Below med. income | −0.932 | 0.394 † | −0.915 | 0.400 † | −0.529 | 0.589 * | −0.533 | 0.587 * | −0.667 | 0.513 | −0.686 | 0.503 |

| Above med. income | −0.355 | 0.701 | −0.334 | 0.716 | 0.177 | 1.194 | 0.181 | 1.199 | −0.114 | 0.893 | −0.094 | 0.911 |

| I do not know income | −0.811 | 0.445 | −0.831 | 0.436 | −0.201 | 0.818 | −0.187 | 0.830 | −19.863 | 0.000 | −19.680 | 0.000 |

| Experience of family member | 2.182 | 8.867 *** | 2.192 | 8.597 *** | 1.197 | 3.310 *** | 1.200 | 3.300 *** | 0.710 | 2.034 † | 0.708 | 2.029 † |

| Constant | −3.000 | 0.050 ** | −3.049 | 0.047 ** | −3.627 | 0.027 *** | −3.616 | 0.027 *** | −3.070 | 0.046 | −2.991 | 0.050 |

| N, Explanatory power | N = 172, pseudo R square = 0.382. | N = 172, pseudo R square = 0.388. | N = 633, pseudo R square = 0.317. | N = 633, pseudo R square = 0.318. | N = 197, pseudo R square = 0.371. | N = 197, pseudo R square = 0.358. | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, Y.-H.; Ma, W. The Relationship between Financial Literacy Misestimation and Misplacement from the Perspective of Inverse Differential Information and Stock Market Participation. Int. J. Financial Stud. 2024, 12, 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs12030081

Lee Y-H, Ma W. The Relationship between Financial Literacy Misestimation and Misplacement from the Perspective of Inverse Differential Information and Stock Market Participation. International Journal of Financial Studies. 2024; 12(3):81. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs12030081

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Yun-Ho, and Weihua Ma. 2024. "The Relationship between Financial Literacy Misestimation and Misplacement from the Perspective of Inverse Differential Information and Stock Market Participation" International Journal of Financial Studies 12, no. 3: 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs12030081

APA StyleLee, Y.-H., & Ma, W. (2024). The Relationship between Financial Literacy Misestimation and Misplacement from the Perspective of Inverse Differential Information and Stock Market Participation. International Journal of Financial Studies, 12(3), 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs12030081