Abstract

In an era where crowdfunding in Portugal is garnering increased public attention, exemplified by notable campaigns like the recent funding of the nurses’ strike, we explore its potential as an alternative financial source to traditional banking. Through a comprehensive case study, we delve into pertinent issues, encompassing European legislation, market dynamics, and a survey disseminated to representatives of the four prominent Portuguese crowdfunding platforms. Comprising forty-one questions across four categories, the survey extracts insights on platform details, company/project information, investor perspectives, and the financing process, along with an evaluation of platform advantages/disadvantages vis-à-vis traditional banking. Despite heightened visibility, crowdfunding remains relatively unfamiliar to the broader public, yet it diverges from banking not as a substitute but as a complementary financial mechanism. Emphasizing accessibility, process agility, and reduced bureaucracy, crowdfunding serves as a means of swiftly gaining recognition for a company or project while tapping into a broad audience. Rather than competition, it offers supplementary support, facilitating the identification and validation of investment opportunities and concepts. Moreover, it streamlines subsequent interactions with banks and investors, enhancing confidence in a project’s viability. In essence, crowdfunding emerges not as an alternative but a strategic complement, enriching the financial landscape with its unique attributes.

1. Introduction

This article focuses on the subject of crowdfunding and its potential relationship with traditional bank financing in the Portuguese context. Crowdfunding draws inspiration from concepts such as microfinance (Morduck 1999) and crowdsourcing (Poetz and Schreier 2012), but it represents its own category concerning resource mobilization, facilitated by a growing number of online platforms dedicated to the topic.

Like in any emerging field, popular and academic conceptions of crowdfunding are in a state of ongoing evolution. Schwienbacher and Larralde (2010) define crowdfunding as “an open invitation, essentially over the Internet, to raise financial resources, either in the form of donation or in exchange for some form of reward, in order to support initiatives for specific purposes”.

Crowdfunding represents an alternative form of financing compared to traditional bank loans. Bouncken et al. (2015), in their conceptual thinking, state that it is open to the participation of everyone, whether private individuals or economic actors. This financing is facilitated through digital platforms based on web 2.0 and is increasingly garnering scientific attention.

Based on the correlation with certain gaps identified in the literature that are extrapolated to the present study, it is evident that the lack of public awareness about crowdfunding platforms is one of the identified challenges, corroborated by various studies highlighting the public’s lack of knowledge about crowdfunding and its associated platforms (Mollick 2014; Belleflamme et al. 2014). This scenario suggests that the lack of campaign promotion may be just a symptom of a broader issue related to the scarcity of knowledge about crowdfunding in general.

Another significant challenge lies in the obstacles posed by insufficient marketing efforts toward attracting investors and promoters, as indicated by previous studies (Ordanini et al. 2011; Belleflamme et al. 2014). This limitation is directly linked to the analysis conducted in this study, emphasizing the need for innovative approaches to promote crowdfunding campaigns and increase their visibility.

Furthermore, there is a gap in the understanding of the preferences and behaviors of crowdfunding investors (Agrawal et al. 2015; Hornuf and Schwienbacher 2018). This lack of understanding suggests that a deeper knowledge of investors could guide more precise and effective marketing strategies, contributing to the success of campaigns.

The main objective is to identify the possible differences between the conventional bank financing model and the innovative crowdfunding system. For this purpose, efforts will be made to gather relevant insights from crowdfunding platforms in Portugal, as they are the main drivers of this type of collaborative financing in the Portuguese context, which is currently still underexplored. It is a form of fundraising that has recently emerged in Portugal, active only since 2011 (Ferreira 2014), and this fact alone highlights the scientific relevance of this article, making it important to explore this construct.

One of the first studies within the Portuguese context that aimed to test and verify the determinants of the amounts raised on the most relevant crowdfunding platform in Portugal, PPL, was conducted by Mourão and Costa (2015). In this study, 247 successful projects were analyzed, and the researchers concluded that recent years have shown lower values in relation to the total amount raised per project. A longer campaign duration, as well as a greater number of investors, tends to increase the total amount raised. It is particularly interesting to note that there are no statistically significant dimensions for ‘value per investor’.

Bessa (2015) developed a study that analyzes crowdfunding, seeking to demonstrate that it is a viable source of funding for Portuguese startups. As the main conclusion, the researcher presents crowdfunding as a viable financing alternative for Portuguese startups and highlights that the most relevant success factors for a crowdfunding campaign are the preparation and organization of the campaign on the platform, the choice of platform itself, and the network of contacts (social networks) and interaction with the investor community.

However, this article is also highly relevant from a social perspective. According to Trabulo (2017), a significant portion of the Portuguese population is unfamiliar with crowdfunding and may be overlooking a valuable investment and financing tool, especially in a scenario where access to bank credit is becoming increasingly challenging. By exploring specific data from Portugal, we can not only assess the effectiveness of crowdfunding as a viable financing alternative but also identify cultural, economic, and regulatory factors that shape this practice.

Throughout this study, we question whether crowdfunding presents itself as a viable alternative to banks or whether it establishes other types of relationships, seeking to understand the rationale behind these dynamics.

Despite the global existence of numerous crowdfunding platforms, including giants such as Kickstarter and Indiegogo, we focused our attention on the Portuguese context. We carried out a comprehensive survey on four prominent national platforms: “goparity”, “raize”, “esolidar”, and “ppl”. All these platforms participated actively, contributing valuable information. Our survey was structured on the basis of the objectives outlined for this study.

We begin by reviewing the main literature on the emergence and implementation of crowdfunding as a financing strategy. We then outline the research objectives and methodology. The results are analyzed in detail in five subchapters, each corresponding to a specific group of questions: information about the platform, information about the companies/projects, information about investors, the financing process, and the advantages and disadvantages of the platform versus bank relationship.

Since the fundamental purpose of this article is to assess whether the concept of crowdfunding has effectively developed and been validated in Portugal as an alternative to the traditional financial system, represented by banks, the crucial conclusion of this study focuses on the perceptions of the managers/founders of the platforms, which are analyzed as to whether or not crowdfunding is a legitimate alternative to traditional bank financing.

Finally, we present this study’s limitations and avenues for future research, as well as its contributions to theory and practice.

2. Literature Review

Crowdfunding, an innovation in the financing paradigm, has deep historical roots, going back to the remarkable “Irish Loan Fund“ of the 19th century. This fund consisted of microcredit societies that, remarkably, provided loans to around 20 percent of Irish families (Hollis and Sweetman 1996).

Its evolutionary trajectory includes significant milestones, such as the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty in New York, which was funded by a campaign launched by Joseph Pulitzer. In the Portuguese context, a similar initiative was enacted after the death of its prime minister in the crash of an aircraft on 4 December 1980. The newspaper “O Dia” adopted a crowdfunding model to finance the construction of a statue in Praça do Areeiro, Lisbon, now known as Praça Francisco Sá Carneiro, (Catarino 2018).

The modern environment, characterized by technological advances and the ease of real-time communication, has catalyzed the creation of virtual spaces that promote innovative forms of collaboration, such as social networks and crowdsourcing.

At the same time, the difficulties faced in the financing market, exacerbated by the 2008 financial crisis, gave rise to new financing tools. The restriction of credit, which is particularly damaging for start-ups and small and medium-sized businesses, has fueled the development of these innovative alternatives.

In the context of historically low interest rates, saving through bank deposits has become discouraged. This has provoked small investors to explore the capital market, where crowdfunding has emerged as a particularly attractive option, offering a more accessible and collaborative approach to financing projects.

The crowdfunding modalities include donation, rewards, “equity—capital”, and loans, each with distinct characteristics (Alegre and Moleskis 2019; Böckel et al. 2021; Qalby et al. 2020).

Coakley and Lazos (2021) analyzed the role and nature of equity crowdfunding as an innovative source of entrepreneurial financing for startups and unlisted ventures. They view equity crowdfunding as part of the fintech revolution and, more specifically, as a multi-stakeholder marketplace that provides indirect network externalities to participating groups such as the public and, increasingly, traditional entrepreneurial finance providers like venture capitalists.

Martins Pereira (2017) emphasizes the popularity of these tools, especially for companies that have difficulty accessing traditional sources of finance. It is important to note that the Crowdfunding Regulation only applies to equity and loan or debt crowdfunding (Martins Pereira 2017).

Crowdfunding has thus emerged as an alternative source of funding, allowing funds to be raised via online platforms. This financial innovation is particularly utilized in times of crisis, as evidenced after the financial crisis of 2008 (Catarino 2018).

Thus, the ease of mobilizing pools of contributions, convening large online audiences, is the result of the convergence of the internet, technological progress, and dedicated platforms. In this paradigm, each individual contributes modest amounts, in contrast to the dependence on “large sums from small groups of sophisticated investors” (Shneor et al. 2020, p. 1).

This phenomenon has recently boosted the emergence of crowdfunding platforms, fueled by the evolution of Internet technology, which has enabled easy and direct communication (Kallio and Vuola 2020, p. 109).

However, a number of similar initiatives have developed, helping to refine what we know today as crowdfunding.

In 2013, António Costa (the current Prime Minister of Portugal) innovated by adopting crowdfunding as the financing model for his campaign for the Lisbon City Council. The choice of PPL, the same platform used by nurses to promote and manage the general strikes they organized, provided a fast and transparent way of raising funds, marking the first political campaign in Portugal to adopt collaborative financing.

In this national context of dynamics and initiatives based on crowdfunding, we also have the example of the startup Volup, specializing in the delivery of meals from luxury restaurants, which launched an equity-crowdfunding campaign this year, reaching half a million euros in the first 24 h and quickly surpassing EUR 600 thousand.

Mora-Cruz and Palos-Sanchez (2023) concluded in their research that there has been a considerable increase in the number of studies on crowdfunding platforms. According to these researchers, these various platforms offer significant opportunities for entrepreneurs to obtain alternative financing and for investors to diversify their investment portfolios. For them, crowdfunding platforms have emerged as a disruptive means of raising initial capital, simplifying the interaction between entrepreneurs and investors. They conclude by stating that despite the growing interest in this area, the literature still lacks comprehensiveness.

More recently, in October 2023, the Portuguese Journal “Jornal de Negócios” announced that the US company F2o Sports from Silicon Valley would be launching a new platform, introducing the concept of “fans to owners”, which will enable fans to become owners of a European football club through crowdfunding campaigns. The initiative will allow anyone to acquire shares in the clubs of their choice and actively participate in the management of the teams. Operating under the SEC’s “Regulation Crowdfunding”, according to the company, “it ensures transparency and regulatory compliance in the process”.

This evolutionary process of crowdfunding has culminated in the need for regulation at both the national and international levels, with the European Union standing out as an organization committed to establishing the rules and frameworks that are essential for the effective management of this practice.

3. Portuguese Context

3.1. Regulations

In their early stages, crowdfunding platforms emerged in a completely unregulated environment, implying the imperative need for regulation to safeguard their participants. In this regard, the European Union (EU), through Regulation 2020/1503 of the European Parliament, established guidelines for European crowdfunding service providers, recognizing the growing importance of this modality as an established form of “alternative” financing for start-ups and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). These companies often rely on modest amounts of money, whether in the form of investments or loans. This scenario involves three main actors: the project promoter, the investors, and an intermediary organization, represented by a crowdfunding service provider that connects promoters and investors via an online platform ((EU)_2020/1503 2020a, p. L 347/1).

This regulation aims to provide legal support that would enable startups to raise modest amounts of money, allowing the validation of business ideas through easy access to a broad investor base. Some Member States have introduced specific national schemes for crowdfunding, keeping these services predominantly at the national level. However, this limited approach disadvantages entities operating in smaller national markets, depriving them of access to crowdfunding services ((EU)_2020/1503 2020a, p. L 347/2). The EU has therefore established a legal regime to promote cross-border crowdfunding throughout the European Union.

It is important to account for the circumstances of the market, especially with regard to Brexit, which took around 80% of the European financial crowdfunding market outside the EU’s borders (Rodrigues Leal 2021, p. 99), and to consider the various market initiatives and the different types of financing associated with crowdfunding (regulated in Portugal by Law no. 102/2015 of 24 August—“Legal Regime for Collaborative Financing” (DL_102/2015 2015)).

In Portugal, the legal framework defines different crowdfunding models, including donation, reward, loan, and capital. In order to operate, crowdfunding platforms must obtain authorization from the Portuguese Securities Market Commission (CMVM), guaranteeing transparency, investor protection, and the prevention of illegal activities. This legal framework aims to promote the development of crowdfunding in Portugal, providing a safe and regulated environment for all parties involved.

It is crucial to focus on investment possibilities such as crowdlending or crowdinvesting. EU legislation has been drafted to address the various concerns related to these financial movements.

Significant contributions to analyzing regulatory intervention at the European level have been provided by the European Banking Authority (EBA/Op/2015/03) and the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA/2014/1378) (Rodrigues Leal 2021, p. 99). However, the different approaches of the Member States prevent some crowdfunding projects from circulating freely across borders, ensuring that crowdlending and crowdinvesting predominantly remain national issues (Zetzsche and Preiner 2018, p. 2).

Despite this, the EU has issued regulations stipulating that all crowdfunding platforms fall under one regulatory regime, allowing all member states to “use transferable securities, loans or comparable instruments to limited company shares to attract investors and raise up to €5 million per year through Crowdfunding” (Wenzlaff 2021, p. 9), as established by the “Regulation on European crowdfunding service providers for business” ((EU)_2020/1503 2020b) of the European Parliament and the Council of 7 October 2020), amending Regulation (EU) 2017/1129 and Directive (EU) 2019/1937.

These regulations establish uniform requirements for the provision of crowdfunding services, addressing the object, scope, supervisory requirements, rules of conduct, and protection of stakeholders. They apply to different crowdfunding services, promoting cross-border activities and allowing them to coexist with national crowdfunding regulations.

3.2. Crowdfunding Platforms in Portugal

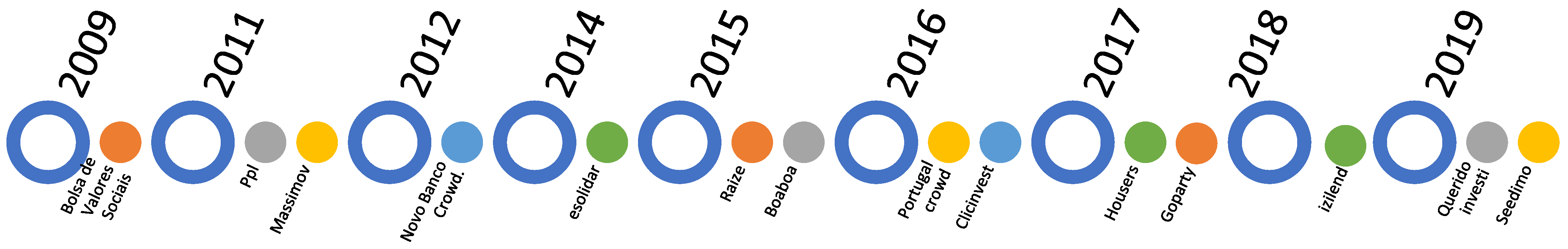

Figure 1 provides a brief contextualization of the evolution of crowdfunding platforms in Portugal.

Figure 1.

Evolutionary context of platforms in Portugal (source: own elaboration).

In 2009, we can say that the “embryo” of crowdfunding in Portugal emerged through the Social Stock Exchange, with the aim of connecting social entrepreneurship and education projects with social investors, in a partnership between Euronext Lisbon, the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, and the EDP Foundation. Since 2011, several platforms have emerged, contributing to the development of crowdfunding in Portugal, although some projects have not achieved their goals.

The Massimov platform, which was created in 2011 and closed in 2015, adopted the rewards model to promote entrepreneurship and social value. The same year, 2011, saw the launch of PPL, a rewards-based crowdfunding platform, which is still one of the most relevant crowdfunding platforms today and one of those that will be the subject of this study. In 2012, “Novo Banco Crowdfunding” focused on social initiatives and was shut down in December 2020 with the technical support of the PPL team.

After a restructuring in 2014, esolidar emerged, focusing on social causes, donations, and rewards. It is also one of the four platforms analyzed in this study.

Raize, another of the national reference platforms and an object of study in this research, presented in 2015, stood out as an online lending platform, competing directly with traditional banking, facilitating loans to micro and small businesses. Raize is considered the first collective loan exchange program in Portugal.

In 2016, the Portugal Crowd platform, focused on property loans, became inactive, as did Clicinvest, aimed at financing small and medium-sized enterprises. Housers, established in August 2017, broke new ground as the first pan-European property investment platform, offering international diversification. Izilend, started in mid-2018 and aimed at the collaborative financing of property projects, is currently inactive.

In 2018, “Goparity” emerged, a pioneer in environmental crowdfunding, promoting investments in line with the UN’s sustainable development goals. This is also one of the platforms selected for this study.

2019 saw the emergence of two loan crowdfunding platforms, namely, Queridoinvesti, focused on property projects, and Seedimo, connecting property developers and investors, although the latter is currently suspended/inactive.

The diverse panorama of these platforms shows the evolution and scope of crowdfunding in Portugal over time. We therefore focus this study on the following platforms due to their representativeness and scope: goparity, raize, esolidar, and ppl.

3.2.1. Goparity

The goparity platform, founded in 2017, stands out as a Portuguese impact investment platform. With a minimum funding amount of EUR twenty, it requires impactful projects to be aligned with at least one of the UN’s 17 sustainable development and clean energy goals. Since its creation, this platform has mobilized more than EUR 4 million in a total of 78 sustainable projects.

According to the data obtained from this platform’s website, the following metrics stand out:

- ○

- Overall amount lent to sustainable projects—EUR 29,273,393;

- ○

- Reimbursed capital—EUR 11,980,855;

- ○

- Interest paid—EUR 1,601,580;

- ○

- Projects financed—322. Of these, 61 have already reached the maturity of their payment plan—EUR all investors have received the full amount of their invested capital and interest;

- ○

- Invested in the secondary market—EUR 1,063,841;

- ○

- Investors—12,240 in (December 2023).

We can observe in Table 1, presented below, the Goparity general indicators taken from the platform’s website.

Table 1.

Goparity general indicators.

Goparity presents itself as a platform that allows ease of access, registry, and financing. After opening an account, investors can invest in the various projects available, which cover areas such as sustainable energy, the blue economy, smart sustainable cities, rural development, and social entrepreneurship. Registered interest rates are around 4.9 percent per year, normally ranging between 4 and 6 percent, with an average duration of 5.1 years.

3.2.2. Raize

The Raize platform stands out as a medium/long-term financing option, offering free analyses and approval in just 48 h. Since its launch in 2015, Raize has channeled more than EUR 54 million into the economy, helping to support more than 15,000 jobs. With a focus on treasury and investment financing, this platform offers a 60-month term and monthly capital amortization. It has quickly established itself as one of the leading peer-to-peer crowdfunding platforms.

The interest rates imposed by Raize are dynamic, adjusting to the risk and term of operation. For companies with lower risk, rates start at a competitive 2.99%. This platform also stands out for financing younger companies with less than 2 years of activity, provided they demonstrate discipline, financial capacity, and growth potential.

According to information provided by the platform itself, Raize has a remarkable track record:

- ○

- It has 73,000 registered investors;

- ○

- It has analyzed 25,000 companies;

- ○

- There is an average of 11 years of activity for the companies financed;

- ○

- The average financial autonomy is 32.00%, indicating that 32.00% of the corresponding companies’ assets are financed with equity;

- ○

- It has realized 3072 SME loans;

- ○

- It has a realizable annual return of 6.51%;

- ○

- It has an accumulated realized return of 55.29%;

- ○

- It has been involved in transactions with the total of EUR 21,140,616;

- ○

- It has a total of 1,305,272 transactions, with an average time to sell a position (worth less than EUR 200) of less than one day.

In terms of profitability, the year 2022 demonstrated solid financial performance, accumulating a historical return of 59%, equivalent to an annual average of 5.63% after losses. Around 98% of Raize’s investors currently enjoy positive returns on their investment portfolios.

3.2.3. eSolidar

This platform, launched in 2014, stands out as an online marketplace that gives charities the opportunity to raise funds and reach new audiences through online shops, donations, and special auctions involving celebrities and brands. With 50,000 recorded users and the participation of 800 charities, this platform was selected in 2014 as one of the most outstanding digital initiatives for social good of the year, also receiving the “Best Business Potential 2014” award from the European Youth Awards.

In April 2015, it obtained EUR 500,000 of investment from Portugal Ventures to consolidate its business model in Portugal and expand operations to the UK. Currently, eSolidar is based at the Impact Hub in Kings Cross, London, and was recognized by Forbes in the “30 under 30 Europe” category for “Social Entrepreneurship in 2016”.

eSolidar stands out as one of the most popular platforms for raising funds to develop projects and support social causes. It claims to have lower costs and be a quick and easy option for publicization. The process of using this platform is simple, involving seven different stages:

- Register with eSolidar;

- Create your crowdfunding campaign;

- Wait for the eSolidar team to analyze your information;

- Your crowdfunding campaign is made available online;

- Payments;

- Rewards;

- Finalization of the crowdfunding campaign.

These steps are explained in detail on the platform’s website. It is important to note that in crowdfunding campaigns, it is possible to make donations by credit card, PayPal, and digital currencies. eSolidar also offers rewards, such as a notepad for donations of EUR 5 and a T-shirt for donations of EUR 10, with the platform’s service fee set at 5% plus a payment method fee of 3%, with 92% of the amount donated to a beneficiary NGO.

3.2.4. PPL

PPL is a crowdfunding platform in Portugal. The term PPL derives from “PPL Crowdfunding Portugal”, which stands for “People, Projects and Free”. This platform was created with the purpose of connecting innovative or creative projects with potential backers, allowing the community to financially support ideas they believe in.

PPL acts as an intermediary, offering an online space where entrepreneurs, artists, non-profit organizations, and others can present their projects and ask the community for financial contributions. This contribution can take various forms, such as donations, pre-purchases, or investments, depending on the type of crowdfunding chosen by the project promoter.

The corresponding projects cover a wide range of areas, ranging from culture, art, and technology to social and environmental causes. PPL provides a platform where project creators can share their ideas, goals, and financial needs, while supporters have the opportunity to become actively involved in the development of initiatives they find interesting or valuable.

The impact of the platform amounts to EUR 7,298,456 raised. The PPL community consists of 234,971 members, who have contributed to the funding of 1702 campaigns, achieving a success rate of 42%. In this process, 210,866 supporters actively participated, and among them, 30,823 contributed to more than one campaign.

PPL’s website offers a concise and accessible explanation of its operations, spanning from the conception of an idea to liaising with the community. This platform’s work covers two crucial areas:

- PPL Causes—Aimed at promoting charitable causes, support is transferred at the end of a period, regardless of whether or not the initial objective has been reached.

- PPL Crowdfunding—Aimed at any other type of project, this system operates on the “all or nothing” principle. If the goal is not reached, the support is returned, free of charge.

The most recent data from 2023, as shown in Table 2, demonstrates the various categories defined in PPL and the funds raised within each.

Table 2.

Raised funds arranged by category.

Initial supporters are often friends, family, and/or colleagues. As the campaign unfolds, it is common to see the involvement of strangers who believe in the ideas proposed or who are motivated by the rewards on offer. This process of broadening the support base contributes to the unique dynamics of crowdfunding on the PPL platform.

Over time, PPL has contributed to the realization of a variety of projects in Portugal, providing a financing alternative to traditional options such as bank loans.

4. Methods

This paper is a qualitative, multiple-case study focusing on four Portuguese crowdfunding platforms (goparity, raize, esolidar, and ppl). The data for analysis were obtained through interviews with the managers of these four platforms. In this context, a series of semi-structured interviews were carried out, using a script that was open enough to allow the order of the questions to be changed. According to Yin (2005), one of the most representative sources of information in case studies is interviews. According to Stake (1995), it is through interviews that a researcher is able to discover the experiences of subjects. For Yin (2005), the spontaneity of interviews allows researchers to question the most important interviewees about the facts of a topic and to ask for their points of view on certain events. In this study, care was taken to encourage the interviewees to reveal their own interpretations. For Yin (2005), this condition is essential for the success of a case study.

The structure of the interview covered five thematic groups:

- Information about the platform;

- Information about the companies/projects;

- Investor information;

- Financing process;

- Advantages/disadvantages of the platform over traditional bank financing.

One of the most common qualitative approaches to data processing is called content analysis. According to Weber (1990) and Bardin (2006), content analysis procedures apply directly to the text or transcripts of communication and can employ both qualitative and quantitative operations. Thus, in this stage of the research, the content analysis technique was used. The aim of content analysis is therefore, according to Bardin (2006), to make inferences by working with traces and indices highlighted by more or less complex procedures.

5. Results

5.1. About the Platform

The first crowdfunding platform was launched in 2011, followed by three others in 2014, 2015, and 2017, with the last one seeing remarkable growth (100 percent) only in 2021.

Currently, among the best-known platforms (goparity, raize, esolidar, and ppl), one is located in the north and three are in the center of Portugal, including one initially based in Porto and later in Lisbon.

Regarding the crowdfunding model used by these platforms, we obtained answers that covered donation, rewards, and short receipts through loans, geared towards entrepreneurs. The last of these items focuses on attracting relatively small projects, many of which are in the arts and social fields, which require more modest funding.

All the platforms consider their actions useful and accessible, offering alternative forms of financing for impact projects. This approach helps to address the lack of financial literacy that perpetuates the gap between rich and poor, complementing and supporting the existing offerings.

Regarding the types of projects supported, the data show a predominance of projects with a social impact, followed by music and books. Citizenship and politics take second place with respect to statistics, with an emphasis on civic causes, which have proved extremely popular in crowdfunding. Cultural projects, boosting cash flow, investing in machinery, or business expansion are also among the categories funded.

When asked about the criteria for evaluating projects, the platforms mentioned an emphasis on social impact projects promoted by social economy organizations. In addition, analyzing risk, financial viability, and contribution to sustainable development is fundamental. Some platforms base their approval on analyzing each company individually when applying for funding, using accounting information. However, one of the interviewees highlighted additional criteria, such as the need for a presentation video and a well-founded proposal.

When it comes to filtering and decision making, there are a variety of approaches. The quality of a presentation, personal information, and the need for a presentation video are considered crucial criteria. This approach serves as an initial test with which to assess the promoter’s commitment. Projects considered to be of poor quality can jeopardize the reputation and credibility of crowdfunding, and therefore filtering is crucial.

As for the minimum and maximum amounts of funding, the answers vary. Some platforms impose no limits, while others set specific amounts, such as EUR 5, EUR 500, and EUR 5000. The maximum amounts, meanwhile, are subject to legal regulations or are set based on the company’s turnover, ensuring a balance between the available funding and the sustainability of a business.

As for the time limit for online projects, there is variation between the platforms. Two of them do not set any time limits, while two others set periods of between 20 and 60 days, with the possibility of extending for a further 15 days if they think the extension will have an impact on the campaign. Another platform sets a period of 30 days, keeping the funded projects on the site for consultation and updating them as they are implemented.

With regard to crowdfunding models, donations and loans are highlighted as the most beneficial for promoters, depending on a project’s objectives. Start-up projects often opt for reward crowdfunding, especially those in the creative, cultural, or solidarity fields.

The interviewees agree that all the models have advantages and disadvantages, emphasizing the autonomy and legitimacy offered by crowdfunding. This method allows for a transparent and democratic approach, with interest paid that contributes to investors’ portfolios.

As for the visibility of companies/projects, all the platforms agree that crowdfunding helps to increase visibility. By using technological tools and digital marketing, the platforms are able to promote fundraising campaigns quickly and globally. Active publicity on the part of the promoters is vital to the success of a campaign, creating a buzz around it.

The inclusion of cryptocurrencies as a financing option is mentioned, with one platform initially accepting their inclusion and another refusing it due to insufficient volume. The positive results and growth of the platforms over the years are highlighted, with some mentioning an active international presence.

When the subjects were asked about the Portuguese population’s awareness of crowdfunding, the answers obtained were divided. Half of them consider the population to be incompletely familiarized, attributing this to the need for greater financial literacy. The other half point out that there is already a reasonable degree of familiarity with the concept, especially after notable campaigns such as the nurses’ strike, which played a crucial role in publicizing crowdfunding across the country.

These results provide a comprehensive overview of the dynamics of crowdfunding platforms in Portugal, highlighting the diversity of models, types of projects funded, and evaluation criteria. The information gathered provides a solid basis for understanding the current crowdfunding scenario in Portugal.

5.2. About the Companies/Projects

In this section, eight questions were addressed, the first of which related to the main areas of activity of the companies/projects seeking funding or support. The answers reflect a significant degree of diversity: non-profit organizations are mentioned as the main focus; the presence of creative projects in the arts, social, civic, and music areas stands out; and sectors such as transport, construction, commerce, and catering are covered. One of the platforms presented the following Table 3 with the project categories.

Table 3.

Project categories.

A variety of companies are featured, ranging from those with several years of activity to start-ups and innovative projects with an emphasis on sustainable development.

The companies/projects are distributed geographically across Brazil and Portugal, with a concentration in the north, although it is thought that, in general, Portuguese companies/projects still have limited awareness of crowdfunding, depending on the area in which the platforms operate.

When asked about entrepreneurs’ feedback on crowdfunding, the answers suggest that this form of financing is perceived as a complement, not an alternative. The following points stand out:

- ○

- Crowdlending fills a gap and is an alternative to traditional forms of investment such as business angels or venture capital. The positive feedback is related to its ease of use, the agility of this process, and its ability to reach a wide audience.

- ○

- Entrepreneurs are enthusiastic because of crowdlending’s ease of use, the agility of the process, and its accessibility for a wide target audience through various means of payment, such as MB Way, credit card, PayPal, or bank transfer.

- ○

- A respondent believed that all the promoters are enthusiastic and satisfied with the alternative, highlighting this mode of funding as being flexible and less bureaucratic.

- ○

- Companies see this service as a complement to banking, not an alternative.

5.3. About Investors

The current composition of investors on crowdfunding platforms is predominantly private individuals, with only one platform opening up to institutional investors so far this year. Although there is no certainty as to the general awareness of the Portuguese regarding crowdfunding, it can be seen that even among those who are unfamiliar, those who use these platforms already have some level of awareness of the concept.

Investor Profile:

- ○

- The majority of investors are nationals, estimated at around 90 percent.

- ○

- Approximately 69,000 investors are registered for each campaign, with the average number of participants ranging from 2000 to 3000 investors.

- ○

- The general perception is that there is a male predominance among investors, although there are no specific statistics. One platform specifically pointed to a distribution of 82 percent men and 18 percent women.

Average Investment:

- ○

- The average amount invested in companies/projects is characterized as being volatile, with a general trend towards amounts between EUR 30 and 60. This range reflects the diversity of investors and the variability of campaigns.

The recent decision of one of the platforms to open up to institutional investors suggests a possible change in the dynamics of funders, while the predominance of national investors highlights local interest in these opportunities. The perception of investor awareness, even among those less familiar with it, indicates a growing awareness and understanding of crowdfunding as an investment method.

The predominant profile of male investors points to a potential area for growth and diversification within the investing public.

5.4. About the Financing Process

As far as the financing process is concerned, we observed various nuances in the entrepreneurs’ preference for modalities. The most recurrent option was to fund the treasury, indicating a need for capital to develop the projects. The significant number of projects funded highlights the significant impact of these crowdfunding platforms, ranging from 173 projects for a platform created in 2014 to around 3150 campaigns for a platform established in 2017.

Success and failure rates:

- ○

- Success rates vary, with one platform reporting a failure rate close to 42 percent, indicating the challenges inherent in the crowdfunding model.

- ○

- The issue of non-compliance with projects, especially in the delivery of rewards, was addressed. The lack of a formal control mechanism is compensated for by the self-regulation of supporters, who play an active role in monitoring and resolving problems.

Application and registration process:

- ○

- The application and registration process on the platforms is described as not being overly bureaucratic, prioritizing the quality and clarity of the projects.

- ○

- Some platforms offer personalized support in creating campaigns, focusing on the credibility of promoters. The deadline for making a campaign available can be quick; in some cases, it is 24 h after registration has been validated.

- ○

- The period between first contact and the campaign becoming available for funding lasts, on average, around a month. The processes of risk analysis, acceptance of the proposal, and formalization can vary from 5 to 10 days, depending on the platform.

Fees in the Process:

- ○

- The fees applied in the process also vary; for example, there is a 5% fee on the amount raised, a fee of 7.5% plus VAT, or a combination of a 1% “ongoing fee” and a 4% “set up fee—competitive”. The detailed explanations of the commission structure provide a clearer view of the financial implications for promoters.

Crowdfunding is emerging as a viable and effective alternative for financing projects, offering flexibility and rapid recognition. Its success rate reflects the challenges inherent in the model, but the community of supporters plays a vital role in regulation and oversight. The application process, while involving some analysis, is characterized by a personalized and not overly bureaucratic approach. The fees, although variable, are transparent and present an alternative to the traditional banking system. The overall perception is positive, with the platforms highlighting the growth and positive impact on the companies and projects financed.

5.5. Advantages/Disadvantages (Platform vs. Banking)

The crowdfunding platforms stand out because of their different characteristics, as evidenced by their responses. One of them accepts donations in cryptocurrencies, while another, compared to traditional banking, considers itself a “monopoly” because there is no donation- or reward-oriented crowdfunding platforms in Portugal.

Another company highlighted international competition, mentioning platforms such as Kickstarter, Indiegogo, and GoFundMe, but emphasizes the superiority of its platform, which is offered in Portuguese and English, using local payment methods such as “multibanco” reference or MB WAY. This approach is appreciated by the Portuguese, covering 80 percent of payments, unlike other platforms that only accept credit cards. Personalized support for campaigns and promoters is also an outstanding feature.

A third platform emphasized its role in collaborative financing in which invests are made most directly in the national economy, supporting companies, families, and especially micro and small businesses. This platform emphasized their agility and lower costs compared to NGOs that face difficulties with banks.

Most of the projects financed by crowdfunding, often cultural or social projects or small start-ups, address needs that traditional banking does not fulfil. The ability to innovate, produce prototypes, or launch small projects is facilitated by crowdfunding, which appeals to the philanthropic and consumerist spirit.

As for the limitations of the platforms compared to traditional banking, some say they have no limitations, while others emphasize the need for extensive publicity of crowdfunding campaigns, a challenging task.

The difficulties center on the community’s investment capacity, which varies between EUR 85 and 200 thousand per campaign. However, this scenario could evolve with the growth of a platform and an increase in investors. The current context of “negative interest rates” and state support due to the pandemic provide banks with unique conditions, such as non-repayable loans.

As for the satisfaction of the companies/projects financed by crowdfunding, the responses focus on the simplicity, speed, and cost-effectiveness of a service. A platform’s positive reputation is emphasized, with a high satisfaction rate among promoters.

The impact of the pandemic has resulted in positive change, driving social campaigns and attracting creative funders. Adaptability during the pandemic brought visibility to the platform, involving institutions such as the Portuguese League Against Cancer and Nestlé.

The year 2020 was marked by internal improvements, growth, and adaptation to online events. Although some promoters restructured payment plans due to frozen or postponed projects, the corresponding platforms did not face bankruptcy.

The presence of business angels and venture capital in crowdfunding is emphasized, complementing and validating projects. Transparency, ethics, and a democratic approach are fundamental, making crowdfunding a complementary mechanism that offers more flexibility and security in business financing.

The assessment of the relevance of crowdfunding as an alternative financial mechanism to banking varies between platforms. Some see it as an alternative, while others consider it a complement to traditional financing, not a direct competitor.

Crowdfunding is seen as a complementary and valuable force for financing projects, especially those that may not have easy access to traditional banking. Its advantages include flexibility, transparency, and a direct appeal to the public, while its limitations involve challenges in the community’s ability to invest and competition with the unique conditions offered by banks. Crowdfunding’s ability to adapt to scenarios such as the pandemic and its ethical and democratic nature are highlighted as factors contributing to its growing acceptance as a valid financial alternative.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

This study’s findings highlight the diversity of projects funded by crowdfunding platforms in Portugal, ranging from non-profit organizations to small start-ups, demonstrating the adaptability of these platforms across different sectors. The predominance of private investors, who are largely male, underscores the need to better understand the profile and motivations of funders.

Comparison with traditional banking emphasizes the effectiveness of crowdfunding as a complement, especially for NGOs and small projects facing challenges with regard to traditional banking institutions. The agility, simplicity, and transparency of the process emerge as distinctive factors, offering an attractive alternative for those seeking funding. Crowdfunding is perceived as a tool that fills gaps, providing ease of access, quick recognition, and, importantly, a wide reach within the target audience.

Regarding the central question of this study—whether crowdfunding is considered an alternative or complementary financial mechanism to traditional banking in Portugal—the results clearly suggest the complementary nature of crowdfunding. Platforms are not seen as a direct threat to banking but rather as an additional channel with which to identify investment opportunities, validate projects, and facilitate access to traditional financing.

Based on the correlation with identified gaps in the literature, one of the most prominent is the lack of public awareness about crowdfunding platforms. This gap is supported by various studies highlighting the general public’s lack of awareness of crowdfunding and its associated platforms (Mollick 2014; Belleflamme et al. 2014). This suggests that the lack of campaign awareness may be just a symptom of a broader issue related to the Portuguese population’s overall lack of knowledge about crowdfunding.

Challenges in marketing with regard to attracting investors and promoters are another relevant gap identified in various studies. The need for more effective marketing strategies to attract both promoters and investors is central (Ordanini et al. 2011; Belleflamme et al. 2014). This is directly related to the limitation identified in this study and highlights the importance of innovative approaches for promoting crowdfunding campaigns and increase their visibility.

Another gap identified by Agrawal et al. (2015) and Hornuf and Schwienbacher (2018) is the lack of understanding of investors’ preferences and behaviors. This gap suggests that a deeper understanding of investors could reveal more precise and effective marketing strategies, contributing to the success of campaigns.

Extrapolating information from these gaps, the limitations identified in this study have direct implications for its main objective of evaluating the role of crowdfunding in Portugal. Lack of public awareness and marketing challenges can affect crowdfunding platforms’ ability to attract both promoters and investors, thus compromising their potential complementarity with respect to traditional banking.

Moreover, the lack of understanding of investors’ preferences and behaviors underscores the importance of a more holistic approach to understanding crowdfunding in Portugal and adapting marketing strategies more precisely.

The correlation of these limitations with the gaps identified in the literature reinforces the need for further research to address these issues and further promote the development and enhancement of crowdfunding platforms in Portugal.

For future research, we suggest providing a deeper understanding of investors’ preferences and behaviors to adapt marketing strategies more precisely. Furthermore, long-term monitoring of funded campaigns can provide insights into the lasting impact of these projects on the economy. On the other hand, a future line of investigation can also be framed, namely, a study on entrepreneurs and companies that have obtained financing through crowdfunding, specifically peer-to-peer lending, as this mode most resembles and compares with traditional financing. The aim in this regard is to verify their thoughts on this type of financing, relevant issues, weaknesses, and strengths and, if possible, to ascertain, through direct comparison, whether they prefer crowdfunding to traditional financing.

This study significantly contributes to the understanding of the role of crowdfunding in Portugal. It provides clarity on existing crowdfunding models, the multiplicity and diversity of supported projects, and the context and presence of platforms in this process as a fundamental means of establishing connectivity between projects/companies and investors (the crowd). This allows for the demonstration of its positive impact on the economy, supporting micro and small businesses that likely would not obtain financing through traditional channels, thus promoting job creation.

In conclusion, this study significantly contributes to understanding crowdfunding in Portugal, highlighting its complementary role to traditional banking, according to the platforms interviewed in this study. Practical implications and future directions suggest a promising path for the development and enhancement of these platforms, further solidifying their position in Portugal’s financial landscape.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.T.; Methodology, B.T.; Software, M.O.; Validation, Z.S. and M.O.; Formal analysis, Z.S.; Investigation, B.T.; Resources, M.O.; Data curation, M.O.; Writing—original draft, B.T.; Writing—review & editing, B.T.; Visualization, M.O.; Supervision, Z.S. and M.O.; Funding acquisition, M.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

NECE-UBI, Research Centre for Business Sciences, Research Centre and this work are funded by FCT— Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, IP, project UIDB/04630/2020.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article, and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Agrawal, Ajay, Christian Catalini, and Avi Goldfarb. 2015. Crowdfunding: Geography, social networks, and the timing of investment decisions. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy 24: 253–74. [Google Scholar]

- Alegre, Inés, and Melina Moleskis. 2019. Beyond Financial Motivations in Crowdfunding: A Systematic Literature Review of Donations and Rewards. International Society for Third-Sector Research 32: 276–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardin, Laurence. 2006. Content Analysis. Lisbon: Edições 70. [Google Scholar]

- Belleflamme, Paul, Thomas Lambert, and Armin Schwienbacher. 2014. Crowdfunding: Tapping the right crowd. Journal of Business Venturing 29: 585–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessa. 2015. Crowdfunding: Alternative Financing for Startups in Portugal. Master’s thesis, Higher Institute of Accounting and Administration of Porto, Porto, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Böckel, Alexa, Jacob Hörisch, and Isabell Tenner. 2021. A systematic literature review of crowdfunding and sustainability: Highlighting what really matters. Management Review Quarterly 71: 433–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouncken, Ricarda B., Malvine Komorek, and Sascha Kraus. 2015. Crowdfunding: The Current State Of Research. International Business & Economics Research Journal (IBER) 14: 407–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catarino, Luís Guilherme. 2018. Crowdfunding and Crowdinvestment: Back to the Future? CEDIPRE Online Publications—32. Coimbra. March 2017. Available online: http://www.cedipre.fd.uc.pt (accessed on 2 May 2022).

- Coakley, Jerry, and Aristogenis Lazos. 2021. New Developments in Equity Crowdfunding: A Review. Review of Corporate Finance 1: 341–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DL_102/2015. 2015, Legal Framework for Collaborative Financing. Issuer: Assembly of the Republic. Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/lei/102-2015-70086389 (accessed on 18 December 2023).

- (EU)_2020/1503. 2020a, Regulation (EU) 2020/1503 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 7 October 2020 on European Crowdfunding Service Providers for Business. Belgium: European Union.

- (EU)_2020/1503. 2020b, Regulation (EU) 2020/1503 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 7 October 2020 on European Crowdfunding Service Providers for Business, and Amending Regulation (EU) 2017/1129 and Directive (EU) 2019/1937 (Text with EEA Relevance). Belgium: European Union.

- Ferreira, A. 2014. Crowdfunding Has Reached Nearly 1.2 Million in Portugal, but Still Lags behind Europe. Available online: https://www.publico.pt/2014/07/07/economia/noticia/crowdfunding-ja-atingiu-quase-12-milhoes-em-portugal-mas-continua-aquem-da-europa-1661828 (accessed on 18 December 2023).

- Hollis, Aidan, and Arthur Sweetman. 1996. The Evolution of A Microcredit Institution: The Irish Loan Funds, 1720–1920. Working Papers ecpap-96-01. Toronto: University of Toronto, Department of Economics. [Google Scholar]

- Hornuf, Lars, and Armin Schwienbacher. 2018. Market mechanisms and funding dynamics in equity crowdfunding. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 42: 467–97. [Google Scholar]

- Kallio, Aki, and Lasse Vuola. 2020. History of Crowdfunding in the Context of Ever-Changing Modern Financial Markets. In Advances in Crowdfunding. Edited by Rotem Shneor, Liang Zhao and Bjørn-Tore Flåten. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins Pereira, Clara. 2017. A Brief Analysis of the New Portuguese Equity Crowdfunding Regime. Working Papers, Jean Monnet Chair. Barcelona: University of Barcelona. Oxford: University of Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Mollick, Ethan. 2014. The dynamics of crowdfunding: An exploratory study. Journal of Business Venturing 29: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Cruz, Alexandra, and Pedro R. Palos-Sanchez. 2023. Crowdfunding platforms: A systematic literature review and a bibliometric analysis. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 19: 1257–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morduck, Jonathan. 1999. The microfinance promise. Journal of Economic Literature 37: 1569–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourão, Paulo, and Catarina Costa. 2015. Investors or Givers? The Case of a Portuguese Crowdfunding Site. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing 373: 113–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordanini, Andrea, Lucia Miceli, Marta Pizzetti, and Anantharanthan Parasuraman. 2011. Crowdfunding: Transforming customers into investors through innovative service platforms. Journal of Service Management 22: 443–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poetz, Marion K., and Martin Schreier. 2012. The Value of Crowdsourcing: Can Users Really Compete with Professionals in Generating New Product Ideas? Journal of Product Innovation Management 29: 245–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qalby, N., Meika Syahbana Rusli, and Elisa Anggraeni. 2020. Analysis and design of crowdfunding investment system as financing alternative for patchouli production in Aceh. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 472: 012041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues Leal, Miguel. 2021. The New European Regime for Collaborative Financing Services (crowdfunding). Actualidad Jurídica Uría Menéndez 55: 95–113. [Google Scholar]

- Schwienbacher, Armin, and Benjamin Larralde. 2010. Crowdfunding of Small Entrepreneurial Ventures. In Handbook of Entrepreneurial Finance. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shneor, Rotem, Liang Zhao, and Bjørn-Tore Flåten. 2020. Introduction: From Fundamentals to Advances in Crowdfunding Research and Practice. In Advances in Crowdfunding. Edited by Rotem Shneor, Liang Zhao and Bjørn-Tore Flåten. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stake, Robert E. 1995. The Art of Case Study Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Trabulo, Rita. 2017. Crowdfunding—The Future of Investment Is Here. Available online: https://observador.pt/opiniao/crowdfunding-o-futuro-do-investimento-esta-aqui/ (accessed on 18 December 2023).

- Weber, Robert Philip. 1990. Basic Content Analysis, 2nd ed. Newbury Park: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Wenzlaff, K. 2021. The (Complete) Guide Book of Crowdfunding for SMEs. Current State of Crowdfunding in Europe. Belgium: EU. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Robert K. 2005. Case Study Planning and Methods, 3rd ed. São Paulo: Artmed. [Google Scholar]

- Zetzsche, Dirk, and Christina Preiner. 2018. Cross-Border Crowdfunding: Towards a Single Crowdlending and Crowdinvesting Market for Europe. European Business Organization Law Review 19: 217–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).