Abstract

Recent studies indicate that lending portfoliocomposition in Islamic banks is concentrated towardsdebt-based lending portfolio; however, the ideal lending portfoliocomposition in Islamic banks should be an equity-based lending portfolio. This article explores the effects of the internal governance factors on lending portfolio compositionofIslamic banks in the GCC Region. The internal governance factors investigated are board of directors’ characteristics (size and independence), Shariah supervisory board attributes (size and cross-membership), and ownership structure (family and government). The generalized least squares (GLS) method is used to examine the relationship between the study variables. The results indicate that two characteristics of the board of directors, size and independence, and two attributes of the Shariah supervisory board, Shariah board size and Shariah board cross-membership, have significant effects on lending portfolio composition of Islamic banks in the GCC Region. However, the rest of the internal governance factors have no effects on lending portfolio composition of Islamic banks in the GCC Region. These significant results add new contributions to the literature in the area of internal corporate governance of Islamic banks. The article concludes with suggestions for regulators and policy makers in the GCC Region with regard to the ideal characteristics of the board of directors and the optimal attributes of the Shariah supervisory board in Islamic banks as well as directions for future studies in this area of research.

JEL Classification:

G11; G21; G32; G34; G39

1. Introduction

The lending practices in general and the lending portfolio compositionof Islamic banks in specific have been the focus of research and investigation for the last few years (Asutay 2012; Cebeci 2012; Farooq 2015; Hanif 2016). The lending instruments in Islamic banks are classified into equity-based lending instruments and debt-based lending instruments. The equity-based lending instruments in Islamic banks, which are also known as profit-loss-sharing (PLS) Islamic financing contracts, include Mudarabah (trustee partnership contract) and Musharakah (joined venture contract) (Ahmed 2014; Ismal 2010; Abdul-Rahman et al. 2019),whereas the debt-based lending instruments in Islamic banks include Murabahah “mark up sale”, Ijarah “leasing contract”, Istisna “manufacturing sale contract”, and Salam “deferred delivery sale contract” (Ahmed 2014; Obaidullah 2005; Ismal 2010; Abdul-Rahman et al. 2019).

In Islamic banks, there is a severe use of debt-based lending instruments over equity-based lending instruments; on average, more than 95% of the lending tools are debt-based lending such as “Murabahah”, while less than 5% of the lending tools are equity-based lending, “Mudarabah and Musharakah” (Suzuki and Sohrab Uddin 2016). The excessive use of debt-based lending might lead to harmful implications on the social and economic condition of the Muslim countries, similar to that faced in the Western countries using the conventional banking systems (Farooq 2015). Moreover, because the current composition of the lending portfoliosin Islamic banks is based mostly on debt-based lending instruments (which are a short-term credit) and not on the equity-based lending instruments (which are a long-term credit), Islamic banks have only a short-term effect on the economic growth of Islamic countries (Hachicha and Ben Amar 2015).

Although the issue of insensitive utilization of debt-based lending instruments over equity-based lending instruments in Islamic banks has been under research for many years, most of the research in this area is theoretical in nature (Asutay 2012; Cebeci 2012; Farooq 2015). Moreover, the reasons behind this imbalanced lending portfolio composition in Islamic banks have not been sufficiently studied. This research gap in the area of Islamic banking and finance field is the primary motivation for the current study.

This study investigates the internal governance factors of Islamic banks in the GCC Region specifically: the board of directors’ characteristics, Shariah supervisory board attributes, and ownership structure, given that they are major internal factors in decision making within Islamic banks (Asutay 2012; Mollah and Zaman 2015). The boards of directors’ characteristics in banks are very important in the internal governance structure because they are accountable for the control and the governance of the bank including the formulation of bank strategy (De Haan and Vlahu 2016; John et al. 2016). The key board characteristics investigated in this study are: board size and board independence. The Shariah Supervisory Board (SSB) represents a major part of the Islamic banks’ governance structure (IFSB 2006), consisting of what is called “Supra Authority” (Choudhury and Hoque 2006). Accordingly, the governance structure in Islamic banks is a “multi-layer governance structure”, while the governance structure in conventional banks is a “single-layer governance structure” (Mollah and Zaman 2015; Adams and Mehran 2003). The Shariah board attributes examined in this study are Shariah board size and Shariah board cross-membership. The ownership structure of banks is a very significant factor in strategy choices, especially when it comes to lending practices and lending portfolio composition of banks (Liu et al. 2011). Moreover, ownership structure is a dominant facet in shaping the various governance systems around the world (Aguilera and Crespi-Cladera 2016). This study investigates two ownership structures in Islamic banks: family ownership and government ownership.

This study focuses on Islamic banks in the GCC Region given the fact that the GCC Region is a leading Islamic banking hub in the world. The GCC Region’s share of international Islamic banking assets is 34% and contributed nearly 70% of the expansion of the Islamic banking industry globally in the last decade (Ernst & Young 2016). Moreover, the GCC Region is home for the biggest five Islamic banks in the World exceeding USD $30 billion in total shareholders’ equity as stated in the World Islamic Banking Competitiveness Report by Ernst & Young (2016). In Table 1 below shows the significance of the GCC Region and the concentration of Islamic finance assets by World Regions in the year 2018.

Table 1.

The concentration of Islamic finance assets by world regions in the year 2018.

Based on the above introduction, this study looks into the effects of the internal governance factors of Islamic banks, namely: the board of directors’ characteristics, Shariah supervisory board attributes, and ownership structure on lending portfolio composition of Islamic banks in the GCC Region. The results of the study indicate that two characteristics of the board of directors, size and independence, and two attributes of the Shariah supervisory board, Shariah board size and Shariah board cross-membership, have significant effects on lending portfolio composition of Islamic banks in the GCC Region. These significant empirical results fill the gap in the literature in the area of internal governance factors and lending portfolio composition of Islamic banks since most of the research in this area is conceptual research (Asutay 2012; Cebeci 2012; Farooq 2015). Furthermore, these results enclose propositions for regulators and policy makers in the GCC Region with regard to the ideal characteristics of the board of directors and the optimal attributes of the Shariah supervisory board in terms of their effects on the lending portfolio composition of Islamic banks in the GCC Region.

The rest of this article is organized in the following order: literature review and hypothesis development, methodology, results and discussion, and, finally, conclusion.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

This section presents a brief literature review and development of the hypotheses related to the study. This section includes five subsections: the lending portfolio composition of banks, board of directors’ characteristics, Shariah supervisory boards’ attributes, ownership structure, and the control variable of the study.

2.1. The Lending Portfolio Composition of Banks

According to Markowitz (1952), a portfolio is a collection of assets, whereas a bank’s lending portfolio is the bank’s loan portfolio which can be either a diversified or concentrated lending portfolio (Rossi et al. 2009). A diversified bank lending portfolio is a portfolio that has a mixture of credit types or income sources such as: interest, fees, and trading (DeYoung and Roland 2001; Stiroh and Rumble 2006), or a diverse geographical reach (Deng et al. 2007), ordifferent assets in varied economic sectors (Rossi et al. 2009). In Islamic banks, a diversified bank lending portfolio is a portfolio that includes a balanced combination of lending instruments, equity-based lending instruments, and debt-based lending instruments, as well as lending to various economic sectors (Asutay 2012; Cebeci 2012; Farooq 2015). The lending portfolio composition of Islamic banks in this study is proxied by the diversification and concentration of the lending portfolio offered by Islamic banks. The diversification level of the lending portfolio offered in Islamic banks is measured using the Adjusted Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (ADSTHHI) (Abuzayed et al. 2018; Bustaman et al. 2017; Elsas et al. 2010; Stiroh and Rumble 2006). The Adjusted Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (ADSTHHI) values range from 0.0 to 0.5; the higher the (ADSTHHI) value, the more diversified the Islamic bank lending portfolio composition. On the other hand, the lower the (ADSTHHI) value, the more concentrated the lending portfolio in Islamic banks is (Abuzayed et al. 2018). The Adjusted Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (ADSTHHI) will be calculated using the following formula:

2.2. The Board of Directors’ Characteristics

The board of directors is a major component in the governance of banks, as it is considered to be the foundation stone of the internal governance structure in banks. The key board characteristics that are included in this study are board size and board independence.

2.2.1. Board Size

Board size is identified as the total number of directors in a board (Almutairi and Quttainah 2017; Bukair and Rahman 2015; Chen and Ling 2016; Pathan 2009). Board size is a very momentous characteristic of the board of directors of a bank. Notionally, there are two theories rationing the association linking the board size and the bank lending portfolio composition: the agency theory (Fama and Jensen 1983; Fama 1980; Jensen and Meckling 1976; Berle and Means 1932) and the resource dependence theory (Abdullah and Valentine 2009; Nicholson and Kiel 2007; Hillman and Dalziel 2003; Hillman et al. 2000). From the perspective of the agency theory and resources dependence theory, a larger board of directors leads to an increased board ability to supervise and advise the executive management (Jensen and Meckling 1976; Fama and Jensen 1983). Moreover, a larger board of directors will have varied work experiences and wider professional networks with the outside environment (Nicholson and Kiel 2007; Hillman et al. 2000). Accordingly, a number of studies have indicated that a bigger board of directors might positively affect the bank lending activities, and therefore lead to diversified bank lending portfolio composition (De Andres and Vallelado 2008; Coles et al. 2008; Anderson et al. 2004). On the contrary, other studies argue that smaller boards are more cohesive and effective (Kiel and Nicholson 2003). Nevertheless, smaller boards have more specific work experience that could negatively lead to more focused lending activities, and as a result, more concentrated bank lending portfolio composition (De Andres and Vallelado 2008; Coles et al. 2008; Anderson et al. 2004).

Following with the above review in relation to the board size of the board of directors and the lending portfolio composition, it is hypothesized that:

H1a:

There is a positive relationship between board size and lending portfolio composition in Islamic banks.

2.2.2. Board Independence

Board independence refers to any board of directors’ member that has no family or business links to the bank and is considered as a non-executive board member (Adams and Mehran 2009, 2012; Desender et al. 2013; Pathan 2009; Pathan and Skully 2010). Based on the agency theory, independent board members enhance the board’s ability to monitor and supervise executive managers’ performance (Fama and Jensen 1983). Moreover, based on the resource dependence theory, independent board members provide critical knowledge and experience to the board of directors (Nicholson and Kiel 2007; Hillman et al. 2000; Yeh et al. 2011).

In accordance with the agency theory and resource dependence theory, few studies assert that high level of board independence might positively result in diverse bank lending activities and a diversified bank lending portfolio (De Andres and Vallelado 2008; Mollah and Liljeblom 2016; Faleye and Krishnan 2017). Alternatively, a smaller number of studies suggest that low level of board independence could negatively lead to more focused lending activities and a more concentrated bank lending portfolio (Rashid et al. 2010; Pathan 2009; Pathan and Faff 2013).

Following with the above brief literature in reference to the board independence of the board of directors and the lending portfolio composition, it is hypothesized that:

H2a:

There is a positive relationship between board independence and lending portfolio composition in Islamic banks.

2.3. Shariah Supervisory Board Attributes

Shariah supervisory board attributes are a very significant factorin the internal governance system in Islamic banks. The major Sharia board attributes included in this studyare discussed in this section in the following order: Shariah board size and Shariah board cross-membership.

2.3.1. Shariah Board Size

Shariah board size is acknowledged as the number of Shariah intellectuals in the Shariah supervisory board in Islamic banks (Farag et al. 2018; Grassa 2016; Mollah and Zaman 2015; Nomran et al. 2018).

Shariah board size is a very key attribute in the Shariah supervisory board in Islamic banks. Based on the theoretical corporate governance literature, two theories might explain the association involving Shariah board size and Islamic banks’ lending portfolio composition: the agency theory (Jensen and Meckling 1976; Fama 1980; Fama and Jensen 1983) and the resource dependence theory (Abdullah and Valentine 2009; Nicholson and Kiel 2007). Concerning the agency theory and resource dependence theory, two viewpoints are related to this matter. The first one asserts that a larger board has higher capacity to supervise and counsel the bank’s executive management (De Andres and Vallelado 2008; Coles et al. 2008; Anderson et al. 2004), and provide more external resources to the bank (Nicholson and Kiel 2007; Abdullah and Valentine 2009). The second theory, conversely, contends that small boards are further organized and more effective boards (Kiel and Nicholson 2003). However, smaller boards provide limited access to the external environment (Nicholson and Kiel 2007; Abdullah and Valentine 2009).

In the light of the agency theory and resource dependence theory, a number of studies have examined the effect of Shariah board size on lending portfolio composition of Islamic banks. Several studies argue that larger Shariah board size positively leads to more diversified bank lending portfolio composition (Alman 2012; Almutairi and Quttainah 2017; Farag et al. 2018). Nonetheless, some studies suggest that Shariah board size does not affect the bank lending portfolio composition (Mollah and Zaman 2015; Nomran et al. 2018).

Based on the above brief literature in reference to Shariah board size and lending portfolio composition, it is hypothesized that:

H3b:

There is a positive relationship between Shariah board size and lending portfolio composition in Islamic banks.

2.3.2. Shariah Board Cross-Membership

Shariah board cross-membership refers to Shariah board members occupying more than one Shariah board seat in several Islamic banks (Haniffa and Cooke 2002). Consistent with the resource dependence theory, the board’s function in a corporation is to supply resource to the corporation from the external environment (Hillman et al. 2009). Therefore, Shariah board members with cross-membership in other Islamic banks can pass imperative information about the industry and share knowledge with other board members in Islamic banks (Nomran et al. 2018; Grassa 2016).

Corresponding to the resource dependence theory, several studies have considered the relationship between Shariah board cross-membership and lending portfolio composition of Islamic banks. Some studies propose that high level of Shariah board cross-membership shows positive results and more diversified bank lending portfolio composition (Almutairi and Quttainah 2017; Grassa 2016; Nomran et al. 2018). However, only one study put forward that high level of Shariah board cross-membership leads to more concentrated bank lending portfolio composition (Alman 2012).

Following the above brief discussion with regard to Shariah board cross-membership and lending portfolio composition, it is hypothesized that:

H4b:

There is a positive relationship between Shariah board cross-membership and lending portfolio composition in Islamic banks.

2.4. Ownership Structure

Ownership structure is a significant aspect in determining various governance systems globally (Aguilera and Crespi-Cladera 2016). Furthermore, the ownership structure of a bank is a major characteristic that affects the strategic decisions of the bank (Liu et al. 2011), including the lending portfolio composition of banks. This section discusses the major forms of ownership structure in Islamic banks such as family ownership and government ownership.

2.4.1. Family Ownership

Family ownership is defined as the percentage of the bank’s shares owned by one family out of the total bank shares (Arouri et al. 2014; Rahman and Reja 2015).

A family-owned corporation condenses the agency problem involving the corporate owners and the corporate managers (Fama and Jensen 1983). Nonetheless, a clash of interest amid the family in control and minority shareholders occurs (Shleifer and Vishny 1997). Furthermore, a different form of clash of interest involving the controlling family and the bank creditors arises (Laeven and Levine 2009; Barry et al. 2011).

A small number of prior studies hint that family ownership could positively affect the leading portfolio composition of Islamic banks resulting in more diversified bank lending portfolios (Arouri et al. 2014; Zouari and Taktak 2014). On the other hand, other studies claim that family ownership might negatively affect the leading portfolio composition of banks resulting in more focused bank lending portfolios (Abdelsalam et al. 2017; Saghi-Zedek 2016; Saghi-Zedek and Tarazi 2016; Zeineb and Mensi 2018).

Following the above brief literature review in relation to family ownership and lending portfolio composition, it is hypothesized that:

H5c:

There is a negative relationship between family ownership and lending portfolio composition of Islamic banks.

2.4.2. Government Ownership

Government ownership or state ownership is recognized when any government entity owns a controlling stake in a bank (Arouri et al. 2014; Boubakri et al. 2018; Feng et al. 2004; Rahman and Reja 2015). Ownership of government in banks or state-owned banks is a global phenomenon, and the share of state ownership is different in developed countries than in developing countries (La Porta et al. 2002; Sapienza 2004). The government’s responsibility as a banking system regulator and monitor and bank owner at the same time causes an amplified agency problem between the bank managers and the bank shareholders (Caprio et al. 2007).

Only some prior studies imply that higher level of government ownership in a bank positively affects lending practices and leads to diverse bank lending portfolio composition (Abdallah and Ismail 2017; Micco et al. 2007; Zouari and Taktak 2014). Conversely, one study concluded that government ownership has no effect on lending portfolio composition of banks (Arouri et al. 2014).

Following the above brief literature review in relation to government ownership and lending portfolio composition, it is hypothesized that:

H6c:

There is a positive relationship between government ownership and lending portfolio composition in Islamic banks.

To summarize, three groups of hypotheses are tested in this study: (A) Ha1–Ha2 board of directors’ characteristics, (B) H3b–H4b Shariah board attributes, and (C) Hc5–Hc6 Ownership Structure. Table 2 presents the hypotheses related to the study variables and the proposed sign and direction of each hypothesis.

Table 2.

Variables Description, Expected Direction, and Relevant Hypothesis.

2.5. The Control Variable

The control variable that is used in this study is bank size. Bank size is described as the size of the bank’s entire assets (Almutairi and Quttainah 2017; Nomran et al. 2018; Guermazi 2020).

The measurements of dependent, independent, and control variables of this research are listed in Table 3 below.

Table 3.

Summary of the study variables and measurements.

3. The Model and Descriptive Statistics

In this section is a brief discussion of the research framework, analysis method, regression model, variables measurements, the control variable, description of the study sample and data collection, and test of multicollinearity.

3.1. The Research Framework

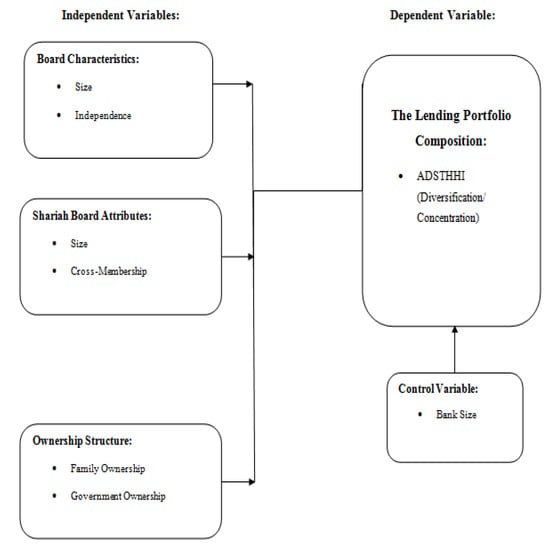

The research framework in this study consists of dependent, independent, and control variables. The dependent variable in this study is the lending portfolio composition in Islamic banks. The independent variables are classified into three clusters of variables. The first cluster is the characteristics of the board, which includes size and independence. The second cluster is Shariah board attributes namely size andcross-membership. The third cluster is the ownership structure that includesfamily and government. The control variable in this study is bank size. Figure 1 shows the study variables.

Figure 1.

Research Variables Framework.

3.2. Analysis Method and Model

The generalized least squares (GLS) method is used in this study to approximate the panel data regression models (Bozec and Laurin 2008; Bunge 2012; Gurbuz et al. 2010). The generalized least squares (GLS) can tackle heteroskedasticiy and autocorrelation problems (Gurbuz et al. 2010; Bozec and Laurin 2008). The Durbin–Watson (DW) test is used to examine autocorrelation. According to Gujarati et al. (2017), generalized least squares (GLS) is more appropriate to overcome these problems and gives much better results. In this study, the generalized least squares (GLS) is conducted by using the latest version of SPSS software for data analysis. The following multiple regression model is conducted in this study:

where:

LPCISB: The Lending Portfolio Composition in Islamic banks.

i: Bank

t: Time

α: Intercept

BSIZ: Board Size

BIND: Board Independence

SHBSIZ: Shariah Board Size

SHBCM: Shariah Board Cross-Membership

FAMOWN: Family Ownership

GOVOWN: Government Ownership

LNSIZE: Size of Bank

Ɛ: Random Error Term

Given that Islamic banks in the GCC Region function under very similar rules and regulations enforced by the Central Banks in the GCC Region (Shehata 2015), a control for country differences (country dummies) is not included in this study. Moreover, Islamic banks in the GCC Region were very stable in their operations including loan behavior and lending rates in the last decade (Ghosh 2016); hence, control for time effects (year dummies) is not included in this study.

3.3. Descriptive of the Study Sample and Data Collection

The data required for this article was mainly hand-collected from the Islamic banks’ annual reports. The study sample covers a ten-year period from 2010 to 2019. There are in total 24 Islamic banks listed in the stock exchanges in the GCC Region, and all of them are included in this study. Therefore, the study sample represents 100% of the listed Islamic banks in the financial markets in the GCC Region. The total number of the collected annual observations for the 10-year period in this article is 235 observations. Only five annual observations are missing due to unavailability of the annual reports of Islamic banks. Table 4 below presents the study sample description.

Table 4.

Descriptive of the Sample of the Study.

To detect any outliers in the study data, Mahalanobis distance test is conducted (Tabachnick and Fidell 2018). An analysis of the SPSS results comparing the Mahalanobis distance value of all observations in the data set to the chi-square critical value indicates that only one observation exceeds the critical value out of 235 total observations in the model. Since there is only one outlier observation detected in the data set, it is considered very minor representing a negligible outlier (Coakes and Steed 2009). Therefore, the outlier observation is retained in the data set due to its insignificant effect on the data analysis.

The results in Table 5 exemplify that the mean value of the Adjusted Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (ADSTHHI) is (0.11). This finding indicates that the lending portfolio composition of Islamic banks in the GCC Region is a concentrated portfolio towards debt-based lending instruments. This result is consistent with the past literature showing that the lending activities of Islamic banks in the GCC Region are very comparable to other Islamic banks around the world (Farooq 2015). The use of equity-based lending instruments such as Mudarabah and Musharakah is very limited in comparison to the use of debt-based lending instruments such as Murabahah and Ijarah (Asutay 2012; Cebeci 2012).

Table 5.

Descriptive Statistics of Variables.

3.4. Test of Multicollinearity

Statistically, a multicollinearity problem exists between the independent variables in the regression model if the correlation value exceeds 0.90 (Gujarati et al. 2017; Hair et al. 2018). The correlation matrix presented in Table 6 shows that all correlation values of the independent variables are below 0.90, which confirms that there is no problem of multicollinearity in the regression model.

Table 6.

Correlation Matrix.

4. Results and Discussion

The results of the multiple regression analysis for LPCISB modelare summarized in Table 7.

Table 7.

Multiple Regression Results.

As presented in Table 7, the multiple regression results for the LPCISB model indicates that F-statistics are significant at 0.01 significance level (F-statistics = 14.825, p < 0.000), which means that the model of this study is highly significant in explaining the variation in the lendingportfolio composition of Islamic banks in the GCC Region as measured by ADSTHHI. In addition, the multiple regression results in Table 7 shows that R2 and adjusted R2 values for the LPCISB model are 38.20% and 35.60%, respectively, which confirms a relationship between the independent variables and the dependent variable of this study. The adjusted R2 value of 35.60% indicates that the regression model of this study which consists of the independent variables, the characteristics of the board of directors (BSIZ, BIND), Shariah board attributes (SHBSIZ, SHBCM), and ownership structure (FAMOWN, GOVOWN), and the control variable (LNSIZE), explains 35.60% of the variation in the dependent variable, the Lending Portfolio Composition in Islamic banks (LPCISB) as measured by the Adjusted Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (ADSTHHI) in this study.

Three groups of hypotheses are tested in this study: (A) H1a-H2a board of directors’ characteristics, (B) H3b-H4b Shariah board attributes, and (C) H5c-H6c Ownership Structure.

Consistent with hypothesis (H1a), the results (β = 0.159, t = 2.163, p = 0.032) show that the board size is positively related to the lending portfolio composition of Islamic banks in the GCC Region measured by (ADSTHHI). This result is consistent with the agency theory and resource dependence theory implying that larger boards have superior capacity and wider range of work experiences to advice the bank’s executive management (De Andres and Vallelado 2008; Coles et al. 2008; Anderson et al. 2004), as a result leading to more diversified lending portfolio composition in Islamic banks. Therefore, it is concluded that hypothesis (H1a) is accepted.

In line with hypothesis (H2a), the results (β = 0.170, t = 2.277, p = 0.024) confirm that the board independence is positively significantly associated with the lending portfolio composition of Islamic banks in the GCC Region measured by (ADSTHHI). Based on the resource dependence theory, independent board members provide significant knowledge and experience to the board of directors (Nicholson and Kiel 2007; Hillman et al. 2000), consequently resulting in more diversified lending portfolio composition in Islamic banks. Thus, it is concluded that hypothesis (H2a) is accepted.

Similar to hypothesis (H3b), the results (β = 0.130, t = 1.733, p = 0.085) show that Shariah board size has significant positive effect on the lending portfolio composition of Islamic banks in GCC region measured by (ADSTHHI). This result is in line with the agency theory and resource dependence theory (De Andres and Vallelado 2008; Coles et al. 2008; Anderson et al. 2004), accordingly leading to more diversified lending portfolio composition in Islamic banks. Hence, hypothesis (H3b) is accepted.

Similar to hypothesis (H4b), the results (β = 0.150, t = 2.073, p = 0.040) confirm that Shariah board cross-membership is positively significantly associated with the lending portfolio composition of Islamic banks in the GCC Region measured by (ADSTHHI). This result corresponds to the resource dependence theory (Abdullah and Valentine 2009; Nicholson and Kiel 2007; Hillman et al. 2000). Shariah board members with cross-membership in other Islamic banks can share industry knowledge with other board members in Islamic banks (Nomran et al. 2018; Grassa 2016), therefore leading to more diversified lending portfolio composition in Islamic banks. So, hypothesis (H4b) is accepted.

Inconsistent with hypothesis (H5c), the results (β = 0.060, t = 0.748, p = 0.455) indicate that family ownership has insignificant effect on the lending portfolio composition of Islamic banks in the GCC Region measured by (ADSTHHI). This result is in variation from the agency theory (Fama and Jensen 1983; Fama 1980), which describes the relationship between the family ownership and the bank lending portfolio composition. A plausible reason for the diverse result than hypothesized could be due to the fact that some Islamic banks in the GCC Region have no family ownership at all as it is shown in Table 5 that minimum family ownership level is 0.00%, therefore resulting in an insignificant effect on the lending portfolio composition of Islamic banks in the GCC Region. Consequently, (H5c) is rejected.

In disagreement with hypothesis (H6c), the results (β = 0.012, t = 0.164, p = 0.870) indicate that government ownership has insignificant effect on the lending portfolio composition of Islamic banks in GCC Region measured by (ADSTHHI). This multiple regression result is not in similarity to the agency theory (Fama and Jensen 1983; Fama 1980; Jensen and Meckling 1976), which explains the relationship between the government ownership and the bank lending portfolio composition. A rational clarification of the different result than hypothesized could be because in the GCC Region there are very limited number of Islamic banks that are completely state-owned (Arouri et al. 2014; Abdallah and Ismail 2017), which gives rationalization for the insignificant effect of government ownership on the bank lending portfolio composition of Islamic banks in the GCC Region. In consequence, hypothesis (H6c) is rejected.

5. Conclusions and Future Studies

This article aimed at exploring the effects of the internal governance factors on lending portfolio composition of Islamic banks in the GCC Region. The article examined the effects of the board of directors’ characteristics (size and independence), Shariah supervisory board attributes (size and cross-membership), and ownership structure (family and government) on the lending portfolio composition of Islamic banks in the GCC Region. The study sample included 235 yearly observations from 24 Islamic banks listed in the financial markets of the six member countries of the GCC Region for the 10-year period from 2010 to 2019. The generalized least squares (GLS) is used to analyze the multiple regression models.

To summarize the results of the study, in relation to the board of directors’ characteristics, the findings indicate that board size and board independence are significantly positively related to the lending portfolio composition of Islamic banks in the GCC Region, indicating that larger board size and higher board independence positively leads to more equity-based lending portfolio (musharakah and mudarabah) and more diversified lending portfolio composition of Islamic banks in the GCC Region. Regarding the Shariah supervisory board attributes, the finding indicates that Shariah board size and Shariah board cross-membership are positively related to the lending portfolio composition of Islamic banks in the GCC Region, suggesting that larger Shariah board size and higher Shariah board cross-membership leads to more equity-based lending portfolio (musharakah and mudarabah) and more diversified lending portfolio composition of Islamic banks in the GCC Region. Regarding the ownership structure, the findings of the study indicates that family ownership and government ownership have no effect on the lending portfolio composition of Islamic banks in GCC Region, due to the fact that very a limited number of Islamic banks in the GCC Region are completely family-owned or state-owned Islamic banks.

To summarize, based on the above results in relation to the lending portfolio composition of Islamic banks in the GCC Region, it is suggested that regulators and policy makers in the GCC Region consider the ideal characteristics of the board of directors and the optimal attributes of the Shariah supervisory board in Islamic banks in the GCC Region. It is recommended to increase the size of the board of directors and include more board members with a wide range of experience in various economic sectors, as well as increase the number of the independent board members since they provide an exceptional knowledge and experience in a range of industries other than the banking and financial services industry. It is also recommended that they include more Shariah board members with diverse Islamic Fiqih schools of thought as each Shariah board member presents a distinctive understanding and interpretation of Shariah Law. Additionally, more Shariah board members with cross-memberships in other Islamic banks should be included.

To conclude, for future studies, it is advised to examine the role of board of directors, Shariah supervisory board, and ownership structure in Islamic banks in different regions of the world such as the Southeast Asia region and MENA region. However, controlling for year events and time effects might be necessary in other regions of the world. In addition, future studies could consider adding more control variables, such as bank capitalization and bank risk.

Author Contributions

N.Y.A.N.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Investigation, and Writing—Original Draft. N.A.A.R.: Conceptualization, Methodology, and Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from Applied Science University (ASU), Kingdom of Bahrain (Approved by University Council Meeting No.15, Academic Year 2019/2020 on 11 June 2020).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abdallah, Abed Al-Nasser, and Ahmad K. Ismail. 2017. Corporate governance practices, ownership structure, and corporate performance in the GCC countries. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money 46: 98–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelsalam, Omneya, Marwa Elnahass, and Sabur Mollah. 2017. Asset Securitization and Bank Risk: Do Religiosity or Ownership Structure Matter? Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2933118 (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Abdullah, Haslinda, and Benedict Valentine. 2009. Fundamental and ethics theories of corporate governance. Middle Eastern Finance and Economics 4: 88–96. [Google Scholar]

- Abdul Rahman, Nora Azureen, and Anis Farida Rejab. 2015. Ownership structure and bank performance. Journal of Economics, Business and Management 3: 483–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Rahman, Aisyah, Mariani Abdul-Majid, and Nurul Fatihah K. J. 2019. Equity-based financing and liquidity risk: Insights from Malaysia and Indonesia. International Journal of Economics, Management and Accounting 27: 291–313. [Google Scholar]

- Abuzayed, Bana, Nedal Al-Fayoumi, and Phil Molyneux. 2018. Diversification and bank stability in the GCC. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money 57: 17–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, Renée, and Hamid Mehran. 2003. Is corporate governance different for bank holding companies? Economic Policy Review: Federal Reserve Bank of New York 9: 123–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, Renée, and Hamid Mehran. 2009. Corporate performance, board structure and their determinants in the banking industry. Journal of Financial Intermediation. FRB of New York Staff Report No. 330. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1150266 (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Adams, Renée, and Hamid Mehran. 2012. Bank board structure and performance: Evidence for large bank holding companies. Journal of Financial Intermediation 21: 243–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, Ruth, and Rafel Crespi-Cladera. 2016. Global corporate governance: On the relevance of firms’ ownership structure. Journal of World Business 51: 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Habib. 2014. Islamic Banking and Shari’ah Compliance: A Product Development Perspective. Journal of Islamic Finance 3: 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alman, Mahir. 2012. Shari’ah supervisory board composition effects on Islamic banks’ risk-taking behavior. Journal of Banking Regulation 14: 134–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, Ali, and Majdi Anwar Quttainah. 2017. Corporate governance: Evidence from Islamic banks. Social Responsibility Journal 21: 815–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Ronald, Sattar Mansi, and David Reeb. 2004. Board characteristics, accounting report integrity, and the cost of debt. Journal of Accounting and Economics 37: 315–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arouri, Houda, Mohammed Hossain, and Mohammad Badrul Muttakin. 2014. Effects of board and ownership structure on corporate performance: Evidence from GCC countries. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies 4: 117–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asutay, Mehmet. 2012. Conceptualising and locating the social failure of Islamic finance: Aspirations of Islamic moral economy vs. the realities of Islamic finance. Asian and African Area Studies 11: 93–113. [Google Scholar]

- Barry, Thierno Amadou, Laetitia Lepetit, and Amine Tarazi. 2011. Ownership structure and risk in publicly held and privately owned banks. Journal of Banking & Finance 35: 1327–40. [Google Scholar]

- Berle, Adolf, and Gardiner Means. 1932. The Modern Corporation and Private Property. New York: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Boubakri, Narjess, Sadok El Ghoul, Omrane Guedhami, and William L. Megginson. 2018. The market value of government ownership. Journal of Corporate Finance 50: 44–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozec, Yves, and Claude Laurin. 2008. Large shareholder entrenchment and performance: Empirical evidence from Canada. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting 35: 25–49. [Google Scholar]

- Bukair, Abdullah Awadh, and Azhar Abdul Rahman. 2015. Bank performance and board of directors attributes by Islamic banks. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management 8: 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunge, Mario. 2012. Scientific Research II: The Search for Truth. Cham: Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Bustaman, Yosman, Irwan Adi Ekaputra, Zaafri A. Husodo, and Ruslan Prijadi. 2017. Impact of interest margin, market power and diversification strategy on banking stability: Evidence from ASEAN-4. Asian Journal of Business and Accounting 10: 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Caprio, Gerard, Luc Laeven, and Ross Levine. 2007. Governance and bank valuation. Journal of Financial Intermediation 16: 584–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebeci, Ismail. 2012. Integrating the social Maslaha into Islamic finance. Accounting Research Journal 25: 166–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Hsiao-Jung, and Kuan-Ting Lin. 2016. How do banks make the trade-offs among risks? The role of corporate governance. Journal of Banking & Finance 72: S39–S69. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury, Masudul Alam, and Mohammad Ziaul Hoque. 2006. Corporate governance in Islamic perspective. Corporate Governance 6: 116–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coakes, Sheridan, and Lyndall Steed. 2009. SPSS: Analysis without Anguish Using SPSS Version 14.0 for Windows. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Coles, Jeffrey, Naveen Daniel, and Lalitha Naveen. 2008. Boards: Does one size fit all? Journal of Financial Economics 87: 329–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Andres, Pablo, and Eleuterio Vallelado. 2008. Corporate governance in banking: The role of the board of directors. Journal of Banking &Finance 32: 2570–80. [Google Scholar]

- De Haan, Jakob, and Razvan Vlahu. 2016. Corporate governance of banks: A survey. Journal of Economic Surveys 30: 228–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Saiying Esther, Elyas Elyasiani, and Connie X. Mao. 2007. Diversification and the cost of debt of bank holding companies. Journal of Banking and Finance 31: 2453–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desender, Kurt A., Ruth V. Aguilera, Rafel Crespi, and Miguel GarcÍa-cestona. 2013. When does ownership matter? Board characteristics and behavior. Strategic Management Journal 34: 823–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeYoung, Robert, and Karin P. Roland. 2001. Product mix and earnings volatility at commercial banks: Evidence from a degree of total leverage model. Journal of Financial Intermediation 10: 54–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsas, Ralf, Andreas Hackethal, and Markus Holzhäuser. 2010. The anatomy of bank diversification. Journal of Banking & Finance 34: 1274–87. [Google Scholar]

- Ernst & Young. 2016. World Islamic Banking Competitiveness Report 2016. London: EYGM Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Faleye, Olubunmi, and Karthik Krishnan. 2017. Risky lending: Does bank corporate governance matter? Journal of Banking & Finance 83: 57–69. [Google Scholar]

- Fama, Eugene F. 1980. Agency problems and the theory of the firm. Journal of Political Economy 88: 288–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, Eugene F., and Michael C. Jensen. 1983. Separation of ownership and control. The Journal of Law and Economics 26: 301–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farag, Hisham, Chris Mallin, and Kean Ow-Yong. 2018. Corporate governance in Islamic banks: New insights for dual board structure and agency relationships. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money 54: 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, Mohammad Omar. 2015. Islamic finance and debt culture: Treading the conventional path? International Journal of Social Economics 42: 1168–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Fang, Qian Sun, and Wilson H. S. Tong. 2004. Do government-linked companies underperform? Journal of Banking & Finance 28: 2461–92. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, Saibal. 2016. Political transition and bank performance: How important was the Arab Spring? Journal of Comparative Economics 44: 372–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassa, Rihab. 2016. Corporate governance and credit rating in Islamic banks: Does Shariah governance matters? Journal of Management & Governance 20: 875–906. [Google Scholar]

- Guermazi, Imene. 2020. Investment account holders’ market discipline in GCC countries. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research 11: 1757–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujarati, Damodar, Dawn Porter, and Sangeetha Gunasekar. 2017. Basic Econometrics, 5th ed. New York: Tata McGraw-Hill Education. [Google Scholar]

- Gürbüz, A. Osman, Aslı Aybars, and Özlem Kutlu. 2010. Corporate governance and financial performance with a perspective on institutional ownership: Empirical evidence from Turkey. Journal of Applied Management Accounting Research 8: 21. [Google Scholar]

- Hachicha, Nejib, and Amine Ben Amar. 2015. Does Islamic bank financing contribute to economic growth? The Malaysian case. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management 8: 349–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph F., William C. Black, Barry J. Babin, Rolp E. Anderson, and Ronald L. Tatham. 2018. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed. New Jersey: Cengage. [Google Scholar]

- Hanif, Muhammad. 2016. Economic substance or legal form: An evaluation of Islamic finance practice. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management 9: 277–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haniffa, Rozaini Mohd, and Terence E. Cooke. 2002. Culture, corporate governance and disclosure in Malaysian corporations. Abacus 38: 317–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, Amy J., and Thomas Dalziel. 2003. Boards of directors and firm performance: Integrating agency and resource dependence perspectives. Academy of Management Review 28: 383–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, Amy J., Albert A. Cannella, and Ramona L. Paetzold. 2000. The resource dependence role of corporate directors: Strategic adaptation of board composition in response to environmental change. Journal of Management Studies 37: 235–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, Amy J., Michael C. Withers, and Brian J. Collins. 2009. Resource dependence theory: A review. Journal of Management 35: 1404–27. [Google Scholar]

- IFSB. 2006. Guiding Principles on Corporate Governance Systems for Institutions Offering Islamic Financial Services. Kuala Lumpur: IFSB. [Google Scholar]

- Ismal, Rifki. 2010. Volatility of the returns and expected losses of Islamic bank financing. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management 3: 267–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, Michael C., and William H. Meckling. 1976. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics 3: 305–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, Kose, Sara De Masi, and Andrea Paci. 2016. Corporate governance in banks. Corporate Governance: An International Review 24: 303–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiel, Geoffrey C., and Gavin J. Nicholson. 2003. Board composition and corporate performance: How the Australian experience informs contrasting theories of corporate governance. Corporate Governance: An International Review 11: 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Porta, Rafael, Florencio Lopez-de-Silanes, and Andrei Shleifer. 2002. Government ownership of banks. The Journal of Finance 57: 265–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laeven, Luc, and Ross Levine. 2009. Bank governance, regulation and risk taking. Journal of Financial Economics 93: 259–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Yi, Yuan Li, and Jiaqi Xue. 2011. Ownership, strategic orientation and internationalization in emerging markets. Journal of World Business 46: 381–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowitz, Harry. 1952. Portfolio Selection. The Journal of Finance 7: 77–91. [Google Scholar]

- Micco, Alejandro, Ugo Panizza, and Monica Yanez. 2007. Bank ownership and performance. Does politics matter? Journal of Banking & Finance 31: 219–41. [Google Scholar]

- Mollah, Sabur, and Eva Liljeblom. 2016. Governance and bank characteristics in the credit and sovereign debt crises–the impact of CEO power. Journal of Financial Stability 27: 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollah, Sabur, and Mahbub Zaman. 2015. Shari’ah supervision, corporate governance and performance: Conventional vs. Islamic Banks. Journal of Banking and Finance 58: 418–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, Gavin J., and Geoffrey C. Kiel. 2007. Can directors impact performance? A case-based test of three theories of corporate governance. Corporate Governance: An International Review 15: 585–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomran, Naji Mansour, Razali Haron, and Rusni Hassan. 2018. Shari’ah supervisory board characteristics effects on Islamic banks’ performance. International Journal of Bank Marketing 35: 290–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obaidullah, Mohammed. 2005. Islamic Financial Services. Jeddah: Islamic Economic and Research Center, King Abdul Aziz University. [Google Scholar]

- Pathan, Shams. 2009. Strong boards, CEO power and bank risk-taking. Journal of Banking & Finance 33: 1340–50. [Google Scholar]

- Pathan, Shams, and Robert Faff. 2013. Does board structure in banks really affect their performance? Journal of Banking and Finance 37: 1573–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathan, Shams, and Michael Skully. 2010. Endogenously structured boards of directors in banks. Journal of Banking & Finance 34: 1590–606. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, Afzalur, Anura De Zoysa, Sudhir Lodh, and Kathy Rudkin. 2010. Board composition and firm performance: Evidence from Bangladesh. Australasian Accounting, Business and Finance Journal 4: 76–95. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, Stefania PS, Markus S. Schwaiger, and Gerhard Winkler. 2009. How loan portfolio diversification affects risk, efficiency and capitalization: A managerial behavior model for Austrian banks. Journal of Banking & Finance 33: 2218–26. [Google Scholar]

- Saghi-Zedek, Nadia. 2016. Product diversification and bank performance: Does ownership structure matter? Journal of Banking & Finance 71: 154–67. [Google Scholar]

- Saghi-Zedek, Nadia, and Amine Tarazi. 2016. Excess control rights, financial crisis and bank profitability and risk. Journal of Banking & Finance 55: 361–79. [Google Scholar]

- Sapienza, Paola. 2004. The effects of government ownership on bank lending. Journal of Financial Economics 72: 357–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehata, Nermeen F. 2015. Development of corporate governance codes in the GCC: An overview. Corporate Governance 15: 315–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shleifer, Andrei, and Robert W. Vishny. 1997. A survey of corporate governance. The Journal of Finance 52: 737–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiroh, Kevin J., and Adrienne Rumble. 2006. The dark side of diversification: The case of US financial holding companies. Journal of Banking & Finance 30: 2131–61. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, Yasushi, and S. M. Sohrab Uddin. 2016. Recent trends in Islamic banks’ lending modes in Bangladesh: An evaluation. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research 7: 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, Barbara, and Linda Fidell. 2018. Using Multivariate Statistics, 7th ed. London: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- The Islamic Corporation for the Development of the Private Sector (ICD). 2019. Islamic Finance Development Report 2019: Shifting Dynamics. London: ICD. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, Yin-Hua, Huimin Chung, and Chih-Liang Liu. 2011. Committee independence and financial institution performance during the 2007–08 credit crunch: Evidence from a multi-country study. Corporate Governance: An International Review 19: 437–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeineb, Ghada Ben, and Sami Mensi. 2018. Corporate governance, risk and efficiency: Evidence from GCC Islamic banks. Managerial Finance 44: 551–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouari, Sarra Ben Slama, and Neila Boulila Taktak. 2014. Ownership structure and financial performance in Islamic banks: Does bank ownership matter? International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management 7: 146–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).