Abstract

Studies that quantify the price impact of the information in corporate press releases and news articles mainly focus on quantitative news, such as earnings announcements, dividends, and financial performance-related events, but leave out other corporate news events. Those that do so generally focus on one source of information and do not compare the price impacts from different information sources. Our study aimed to extend previous studies by quantifying and comparing market reactions to corporate press releases and news articles across different news categories. We classified and categorized 100,960 news items, encompassing 26,546 corporate press releases and 74,414 news articles, of 615 firms in the Stock Exchange of Thailand between 1 January 2017 and 31 December 2019. These news items were classified into categories based on the information contained in corporate press releases and news articles. We then studied the market reactions to these news categories. We found that the price impact from corporate releases is sustained for both positive and negative news categories. Our results also show that the positive price impact for news reported by the media tends to reverse, consistent with prior studies. In contrast, the negative price impact from news articles holds; this result differs from previous studies. Our data also show that managers tend to leak and recycle good news while the release of bad news is delayed.

1. Introduction

The relationship between firms’ information disclosure, through corporate releases and news media reporting, and the financial markets has long been a popular area of study for researchers. The continuous developments and tightening of rules and regulations on corporate disclosures have required firms to disclose more information in a timelier manner. Technological advancement has allowed the faster dissemination of information between corporations, news agencies, and the financial markets (Gao and Huang 2020). With access to more information, managers learn that strategic releases of information can trigger significant price reactions to their share prices (Doyle and Magilke 2009). This dynamic relationship between management disclosures, media, and financial markets continues to provide rich ground for research.

Research in this area has mainly focused on financial market reactions to financial news, specifically on earnings (Atiase et al. 2005; Chambers and Penman 1984; Christensen et al. 2004) and dividend announcements (Ghosh and Woolridge 1988; Below and Johnson 1996), mostly leaving out news related to other corporate events. Even studies that look beyond earnings and dividends focus on limited high-level categories of news (Boudoukh et al. 2019; Feuerriegel and Pröllochs 2021). Prior studies have also primarily focused on single types of data, such as corporate press releases (Neuhierl et al. 2013; Tsileponis et al. 2020), Twitter messages (Bing et al. 2014; Nofer and Hinz 2015), news from newspapers (Antweiler and Frank 2006; Boudoukh et al. 2019; Fang and Peress 2009), etc. This has not allowed for a comparison of the impact from various data sources for the same period.

Due to the complexity and the large amount of data associated with this type of research, most studies use textual analysis tools to estimate the tone of the news rather than focusing on the information contained in that news. An example of such a study includes the research by Ahmad et al. (2016), who studied the time-varying nature of the relationship between a media-expressed firm-specific tone and firm-level returns, and Tetlock (2007), who used textual analysis to quantify media pessimism and quantitatively measure the interaction between the media and the stock market. Although the study of news tone allows us to distinguish the likelihood of news being positive or negative, it does not provide the distinction between the type and severity of the news. For example, news about a company winning awards and news about a company reporting strong quarterly earnings are both deemed positive news with likely very positive news tones. However, the market would likely react more strongly to strong quarterly earnings when compared to winning awards (Neuhierl et al. 2013).

Furthermore, studies on the relationship between the media and financial markets have disproportionately been based on more developed financial markets, like the US and Europe. Limited studies have been conducted on this area in developing markets where corporate governance and behavior might differ from developed markets. Our study focuses on Thailand, which is a less developed market. The Thai capital market has a weaker legal enforcement and governance system than developed countries. Based on the 2020 study conducted by the Asian Corporate Governance Association,1 Thailand ranks eighth among the twelve countries in the study, behind markets like Australia, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Malaysia. Similarly, in the Global Competitive Index database collected by the World Economic Forum, under the Financial Markets Efficiency: Corporate Trustworthiness and Confidence for 2017–2018,2 Thailand ranks 63rd while the United States ranks 4th. To our knowledge, studies that quantify and compare the different price impacts of information contained in corporate press releases and news media across multiple news categories have not been conducted.

This paper contributes to the literature on the price impact of corporate press releases and news articles in several ways. From a theoretical perspective, we apply the same quantification methodology across corporate press releases and news articles for the same set of companies over the same period; this allows us to compare and show the price impact differences between corporate press releases and news articles across news categories. This price comparison is carried out during both the immediate and more extended event windows, providing insights into the differences in the price impact in the longer term. Next, our study focuses on Thailand, a less developed market, which could yield different findings from most of the research in this area that focuses on developed markets. Lastly, this paper also provides practical contributions via suggestions to regulatory agencies to increase awareness of the investing public on the impact of news media on market reaction. Our findings point toward a need for regulators to educate and raise the investing public awareness of potential news media report manipulation for the potential benefit of corporations. The results from this study can also serve as a basis for further research related to news and media and the related price impact on share prices.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In the next section, we begin by reviewing the relevant literature. Section 3 provides a description of the Stock Exchange of Thailand and a discussion on the Stock Exchange of Thailand Disclosure Act and the implications of press disclosure in the Stock Exchange of Thailand. Section 4 outlines the data set, and, in Section 5, we discuss the research methodology. Our findings are presented in Section 6, which includes a discussion on the additional analysis of the longer event window, and we conclude in Section 7.

2. Literature Review

Market reactions to information releases through corporate press releases or news articles have received significant attention in finance. These reactions offer insights into how efficient the financial market is at incorporating the information into the share price.

The two main underpinning theories that form the basis of this study are the efficient market hypothesis (EMH) and information asymmetry. The definitive paper on the EMH developed by Eugene Fama (Fama et al. 1969) laid the foundation for research in this area. Fama argued that all available information regarding any asset, once available, is efficiently priced in by the market. As a result, it becomes extremely difficult for any individual or group of investors to gain an unfair advantage by analyzing past data or publicly available information to predict future price movements consistently. Many subsequent works that examined stock price reactions to news releases helped to highlight the importance of the timely release of information (Chan 2003; Huynh and Smith 2017).

Information asymmetry is a fundamental concept in finance and arises when one party has better information than the other in a transaction. This asymmetry in information can lead to inefficiencies (Akerlof 1978), adverse selection (Rothschild and Stiglitz 1978), and even moral hazards (Holmström 1979). Empirical studies have also substantiated the impact of information asymmetry across diverse fields (Leland and Pyle 1977; Diamond 1984). Corporate press releases are a means used by firms to help reduce information asymmetry (Sankaraguruswamy et al. 2013). Similarly, news articles provide better access to information, reducing information asymmetry (OuYang et al. 2017).

Numerous studies have explored the price informativeness of corporate press releases and news media in influencing stock price movements. Corporate press releases are shown to convey timely and relevant information to the market, indicating that they play a critical role in enhancing market efficiency (Easley et al. 1996). Studies have also examined the different effects of voluntary and mandatory press releases on price informativeness, with voluntary disclosure having a significant impact compared to mandatory disclosure (Haggard et al. 2008). Even the tone and readability of the corporate press release can be a factor that affects price informativeness (Tetlock 2007; Du and Yu 2021).

News media, both traditional outlets and new digital platforms, play a significant role in disseminating information to a broader audience. News coverage can amplify the price impact of corporate announcements (Tetlock 2011). The relationship between news media and price informativeness is a complex one. It has been shown that media coverage impacts pricing adjustments and leads to herding behavior and overreactions (Barber and Odean 2008). The content and timing of media reports is also a factor that affects the informativeness of news media (Baker and Wurgler 2007). Finally, how corporate press releases and new media interact can substantially impact price informativeness. It has been shown that corporate press releases can be amplified by news media, enhancing the speed and accuracy of price adjustments (Easley and Kleinberg 2010).

Content provided in corporate press releases, particularly earning announcements, has been a hot area for research. The early study by Ball and Brown showed that earnings announcements could lead to substantial and rapid price adjustments (Ball and Brown 1968). Earnings surprises and the quality of information in corporate press releases can contribute to variations in market reactions (Lang and Lundholm 1993). Jegadeesh and Livnat also showed the importance of guidance in corporate press releases (Jegadeesh and Livnat 2006). The global financial crisis helped highlight the importance of accurate corporate press releases, with corporate press releases and media coverage having an impact on investor confidence and market stability (Akerlof and Shiller 2010).

The impact of content in news articles on market reactions has been extensively studied. Studies show that media can significantly influence the valuation and performance of firms (Tumarkin and Whitelaw 2001; Griffin et al. 2011; Ahern and Sosyura 2014; Rogers et al. 2016). Tetlock investigated the relationship between media sentiment and market outcomes and found that price decline is associated with media pessimism (Tetlock 2007). Similarly, it has been shown that investors allocate more attention to news articles with extreme sentiment (Gentzkow and Shapiro 2010). Heightened media coverage and investor attention can also lead to increased trading activity and stronger price movements in response to news releases (Barber and Odean 2008).

Behavioral biases have also been explored in the context of market reactions, with the results showing that investors tend to overreact to extreme news (Kahneman and Tversky 2013; Kwon and Tang 2020). Investor sentiment and behavioral bias can also contribute to price anomalies and lead to departures from efficient market pricing (Barberis and Thaler 2003). The advent of social media has introduced new dynamics with studies carried out on the price impact of information from Twitter (Bollen et al. 2011; Jung et al. 2018) and Reddit discussions (Zhang et al. 2018), connecting online content and market reactions.

In conclusion, the literature on market reactions to corporate press releases and news articles showcases a multifaceted interplay between the price informativeness of the information contained in the news, how the news is disseminated, investor behavior, and market dynamics. While the market generally exhibits efficiency, its reaction to news content contained in corporate press releases and news articles can be affected by behavioral biases and the development of information sources.

3. The Stock Exchange of Thailand

The Stock Exchange of Thailand (SET) is the primary securities exchange in Thailand, where various financial instruments, including stocks, bonds, mutual funds, and derivatives, are traded. Established on 30 April 1975, the SET plays a crucial role in the development of Thailand’s capital markets, providing a platform for companies to raise funds while offering investment opportunities for individuals and institutions. This has contributed significantly to the growth and modernization of Thailand’s financial sector and economy. Firms listed on the Stock Exchange of Thailand are classified into eight industry groups and twenty-eight business sectors, as presented in Table 1. The details of the criteria for the classification and the structure of the industry groups and business sectors can be found on the SET website (https://www.set.or.th/en/listing/equities/industry-sector-classification, accessed on 17 August 2023).

Table 1.

Provide a list of the sectors and subsectors of firms in our sample total of 615 firms. The SET and MAI classify firms into 8 industry groups, with SET further breaking down the main groups into 28 business sectors.

The SET is regulated by the Securities and Exchange Commission of Thailand (SEC). The SEC ensures that the exchange operates in a fair, transparent, and orderly manner and enforces rules to protect investors’ interests. To be listed on the SET, companies must meet specific eligibility criteria, including financial performance, corporate governance standards, and transparency. The SET has different market tiers for different types of companies, such as the Main Board for large-cap companies and the Market for Alternative Investment (MAI) for smaller or emerging firms. Our study covers firms listed on both the SET and MAI. The SET is open to both domestic and foreign investors. In addition to individual investors, institutional investors, mutual funds, and foreign institutional investors actively participate in the exchange. The SET maintains a robust surveillance system to monitor trading activities and ensure compliance with market rules and regulations.

The regulation that focuses explicitly on the disclosure requirements of listed firms in the Stock Exchange of Thailand (SET) is the “Regulation of the Stock Exchange of Thailand Re: Rules, Conditions, and Procedures Governing the Disclosure of Information and Other Acts of a Listed Company 2017”. This regulation was first introduced in 1995 and has gone through multiple updates and revisions, specifically between the years 2000 and 2010, when five significant revisions were made. The establishment of the Sarbanes–Oxley Act (SOX) of 2002 in the United States, which was aimed at curbing accounting scandals, likely contributed to the acceleration of revisions during that period. With each revision, the requirements became more specific and required the timelier disclosure of information. Broadly, information that must be disclosed immediately includes the following:

- Information that could have a significant impact on a company’s securities and their market price.

- Information that may impact investment decisions regarding the company’s securities.

- Information that may affect the interests of shareholders.

The regulation then goes on to detail twenty-six events that need to be disclosed immediately and eight events that need to be disclosed within three days. An abbreviated disclosure checklist for the listed companies on the SET is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Abbreviated disclosure checklists for companies listed on the Stock Exchange of Thailand based on the “Regulation of the Stock Exchange of Thailand Re: Rules, Conditions and Procedures Governing the Disclosure of Information and Other Acts of a Listed Company 2017”.

In its detailed description of the disclosure requirement, except for the “Litigation or major dispute” category that provides some guidelines, the SEC did not give a clear definition of what could be considered “significant” or “major”. It has no specific threshold or guidelines on how it should be determined or quantified. As such, firms have some discretion on what they deem to have a significant or major impact. For example, as discussed in a later section, the threshold for “major” good news is likely to differ from the threshold for “major” bad news. Our data provide evidence that firms take advantage of this discretion and tend to interpret it to their advantage by releasing a significantly smaller amount of negative news. Even when they did release “negative” news, it was likely delayed. In the current 2017 version of the regulation, all key events are required to be disclosed “immediately”, which by the SET definition is “on the event date or latest by 9 am of the next working day”. The event date is defined as the date the board of directors or shareholders’ meetings have the resolution.

However, the information release timeframe of many events on the list is still at the discretion of management. For example, management still has control over the date on which a merger is completed or when a significant commercial contract is closed. Effectively, a manager can still time the execution of these events (Dellavigna and Pollet 2009; Doyle and Magilke 2009). Their obligation, in terms of regulations, is to disclose this information only after the event has occurred.

The implications of press disclosure in the Stock Exchange of Thailand, as in other markets, are significant for both investors and companies. Disclosures play an important role in disseminating information to investors and shaping market dynamics (Botosan 1997; Chuthanondha 2020). A study by Panyagometh (2020) shows that timely and accurate press disclosure can increase investor confidence and support their decision-making. Effective press disclosure enhances investor confidence, as it provides them with timely and reliable information to make well-informed investment decisions. Investors can assess a company’s performance, financial health, and future prospects based on the information disclosed, leading to a more efficient allocation of capital. Transparent and readily available information helps make markets more efficient. It ensures that stock prices reflect the most recent and relevant data, reducing information asymmetry between investors. Good governance practices are critical to ensuring the accurate and timely release of information (Leuz and Verrecchia 2000). A well-regulated market fosters investor trust and contributes to a healthy investment environment.

4. The Data Set

Our data set comprises corporate press releases and newspaper articles distributed between 1 January 2017 and 31 December 2019, a total of three calendar years. These corporate releases and news articles cover all the listed companies listed in the Stock Exchange of Thailand (SET) and the Market for Alternative Investments (MAI) before 2017. Firms that had their name changed or had trading suspended/delisted during the period are excluded from our sample. With the mentioned filters, a total of 615 firms are included in our sample, with 498 firms from SET and 117 firms from MAI. We obtained the news related to each listed company by searching the news content for the company name in full.

The corporate news releases were gathered from ThaiPR.net (www.thaipr.net, accessed on 17 August 2023) and the Stock Exchange of Thailand news database (www.set.or.th/en/market/news-and-alert/news, accessed on 17 August 2023). Corporate news releases via the stock exchange are generally designed to comply with the required disclosure and consist of routine earning announcements, corporate event material deemed to be relevant, and mandatory disclosures as required. Since the regulation on disclosure describes the essential nature of news that needs to be disclosed in some detail across important news categories, the SET disclosures by the companies serve as a key element of our official corporate press releases data set.

ThaiPR.net is a prominent newswire service provider in Thailand. Corporate press releases via ThaiPR.net cover a broader range of corporate events and initiatives, such as a company winning awards or the preannouncements of earnings. News releases via ThaiPR.net are then typically distributed to their distribution network, which encompasses newspapers or other media outlets, such as trade magazines, business radio, and television channels. Over the last decade, with newspapers and other traditional media channels establishing an online presence, this news is also made available through their online media. These releases can be picked up by the news media to be featured in their newspapers and interpreted for their readers. Our corporate news releases were gathered from the SET news database, and ThaiPR.net covered all the listed companies in our sample.

The data from newspaper articles related to the listed companies were sourced from NewsCenter. This news database provider compiles news from all major local newspapers in print and online formats. News articles contain commentaries, analyses of corporate events, investigative reports, and paid releases by the firms, among others. Our data comprises news articles from over forty-four major newspapers and covers ninety-eight percent of all listed firms in our sample. The corporate releases and news articles were then classified based on their information content under 11 news categories with 49 subcategories. These categories reflect and encompass the disclosure requirements by the SET. News releases with no expected price impact (e.g., the filing of regulatory forms, guest visits to the company, general marketing news, and the like) were excluded. We also removed categories with less than 30 observations across all categories. This left us with 100,960 news items, 26,546 corporate press releases, and 74,414 news media articles.

Textual analysis tools exist to automate the classification process. However, due to the granularity of our classification coupled with the interpretation complexity of the Thai language, we found that existing textual analysis tools might not provide accurate categorization. This is particularly true in qualitative news categories where slight deviations in wording can result in different interpretations (e.g., new product versus product updates). As a result, we decided to adopt a manual classification. In the future, where more advanced and accurate textual analysis tools for the language are available, our database can also serve as a basis for news classification and research in news information analysis.

For the purpose of our study, quantitative news and qualitative news are classified based on the type of data and information they provide. Quantitative news primarily deals with numerical data, statistics, and measurable information. It focuses on reporting facts and figures that can be quantified. Examples of quantitative news include financial performance, dividend announcements or economic indicators (GDP growth, inflation rates, unemployment rates), and other numerical data. For our research, the Dividend Payments, Financial Performance, and Debt and Equity Offering news categories are broadly classified as quantitative news. Qualitative news, on the other hand, is more subjective and focuses on non-numeric information, descriptions, opinions, and narratives. Examples of qualitative news include articles about company awards, new product launches, management changes, industry trends, and other nonquantifiable aspects that can impact businesses and economies. Qualitative news provides broader implications of events or decisions and accounts for a larger portion of news categories. All other news categories, other than those specified as quantitative news categories above, are classified under qualitative news categories.

Table 3 presents a description and the number of observations for corporate releases and news articles for each of the ten categories. Overall, the financial category that contains mainly quantitative information accounted for the most significant number of news releases across both corporate press releases and news articles, with 12,782 corporate releases (almost fifty percent of the total corporate press releases) and 26,365 news articles (over thirty-five percent of all news articles). Among these, the largest number of news releases was derived from financial result announcements. This illustrates the relative importance of financial results, which can be considered the primary driver of firm value relative to other news categories.

Table 3.

Press release categories: Table 3 provides brief descriptions of the news categories and reports on the total number of press releases and newspaper articles in each news category. The sample period is January 2017–December 2019.

The next largest categories are the strategy and performance categories, which contain more qualitative information about firms’ strategic decisions, profitability trends, and credit-related news. Other categories have a relatively smaller number of news articles due to the lower frequency of occurrence (e.g., M&A and management changes).

Comparing the number of corporate releases across news categories, we can observe the impact of management discretion on what and how much information is released. The lack of specificity on what is considered significant and major, as described by the regulation governing disclosure, could be why firms tend to disclose less negative news and are more active in announcing more positive news in their corporate releases. This can be seen by comparing corporate announcements in categories such as customer loss/win, the preannouncement of negative/positive performance, positive/negative credit news, infrastructure downsizing/expansion, and profitability declining/improving. Of all the mentioned categories, negative news is reported much less than positive news, with only 7 customer loss events reported compared to 933 customer win events. Similarly, only 17 negative preannouncements were observed compared to 626 positive preannouncements. This is consistent with findings from prior research that firms tend to withhold or delay the announcement of negative news (Kothari et al. 2009; Sletten 2012), even when they voluntarily disclose bad news, to preempt the undesirable impact of earning surprises or even deter potential competitors from entering the market (Skinner 1994; Suijs 2005).

Looking at the differences in the number of observations between corporate press releases and news articles, we found that, overall, news articles have an average 2.9 times larger number of observations than corporate releases across all categories. More “positive news” categories have higher than the stated average (2.9 times) number of news articles compared to “negative news”. This is consistent with previous studies that illustrate management attempts at managing media rereporting (Solomon and Soltes 2012). There are a total of twenty-nine subcategories in which news articles have a higher than the average level of coverage by 2.9 times. Out of the twenty-nine subcategories, twenty-one categories are considered generally positive news categories (e.g., news categories related to customer winnings, new partnerships, the preannouncement of strong financial results, new product launch, acquisition intent and the IPO of a subsidiary, or improving profitability and infrastructure expansion) and all have a disproportionately higher level of coverage in newspapers when compared to corporate releases. On the other hand, only eight “negative news” categories, such as customer loss, legal problems, SEC investigation, and product defects, have a high media coverage ratio. The eight negative categories have a much smaller number of corporate releases, with an average of 64 corporate releases per category, compared to positive categories with an average of 303 corporate releases.

Specifically for financial categories, strong financial results announcements have higher news article coverage ratios than weak financial results. However, for preannouncements, despite the much higher number of corporate releases on positive preannouncements (626 positives compared to 17 negatives), the rereporting ratio by the media is significantly higher for negative preannouncements with the rereporting ratio by news articles at over 40 times when compared to 14.9 times for positive preannouncements. Solomon and Soltes (2012) accounts for these differences more to media sensationalism than the information content of this news.

It is also worth noting that the management news category has a news article coverage ratio of only 0.36, which seems to indicate the relative lack of attention by the media in this area.

Table 4 presents descriptive statistics for monthly press release activity across firms. Panels A, B, and C present the statistics for corporate press releases, news articles, and the combined number of news publications between corporate releases and news articles, respectively. The size quintiles are formed every month based on the market capitalization and contain a roughly equal number of stocks (123 stocks).

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics on monthly press release activity: presents descriptive statistics for monthly press release activity across firms. Panels A, B, and C present the statistics for corporate press releases, news articles, and the combined number of news publications between corporate releases and news articles, respectively. The size quintiles are formed every month based on market capitalization and contain a roughly equal number of stocks (123 stocks).

For corporate releases, we see that the first four quintiles have a similar number of releases, ranging from 3793 to 4773. However, the last size quintile, which incorporates the largest 123 companies, has 9490 corporate releases, nearly double the number of corporate releases of the next largest quintile at 4773 releases.

The average number of releases for the first four quintiles ranges from 0.86 to 1.08 but jumps to 2.13 for the largest firms in the fifth quintile. The median number of releases ranges from 0 to 1 across all firm sizes. The most significant difference between the median and the average number of releases comes from the largest firms, with a median of 1 and a mean of 2.13. This is consistent with conventional knowledge that larger firms tend to have more corporate activities and comply with the theory that highly visible firms face a greater demand for information transparency and adopt stricter rules of disclosure (Hermalin and Weisbach 2012).

When we look at the news articles panel, the number of news articles gradually increases from the smallest firms in the first quintile at 4450 articles to 7470 articles for firms in the third quintile. But, from there, the level of news coverage almost doubled from the third quintile at 7470 articles to the fourth quintile at 13,431 articles and more than tripled from the fourth to the fifth quintile at 43,078 articles. This indicates a disproportionate coverage ratio for the firms in the largest quintiles. Similarly, the median number of news articles for the largest firms in the fifth quintile jumps to 5 compared to smaller quintiles with medians between 0 and 1. The mean score for newspaper articles also shows a big difference for large firms in the fifth quintile, with a mean score of 9.65, more than three times the amount of news compared to the next largest quintile at 3.03.

The median number of news articles that are significantly lower than the mean indicates that a small subset of larger firms in the sample is responsible for the larger number of corporate releases and news articles. This is no surprise as larger firms are also of more interest to investors. Hence, it is natural that newspapers tend to report more on their corporate activities than on those of smaller firms. This finding is consistent with research by Solomon and Soltes (2012), who found that size significantly increases the probability of newspaper coverage. Comparing the number of news articles to the corporate releases across all the firm size quintiles confirms that smaller firms do not receive similar news coverage despite issuing a similar number of corporate releases. This is most obvious when comparing firms in the first four quintiles to the firms in the fifth quintile.

The data in the combined panel include all corporate releases and newspaper articles and reflect the combined impact of the observations in both the corporate release and newspaper article panels. The mean number of combined corporate releases and news coverage for small firms stands at 1.86 per month, while the mean for large corporates stands at 11.78 per month, almost six times that of smaller firms. The news release number exhibits a disproportional increase as the firm size increases, with the mean of the first four quintiles ranging between 1.86 and 4.11 news releases per month, while total releases and coverage for the firms in the fifth quintiles (large) jump significantly to 11.78.

5. Empirical Tests

In this section, we investigate the impact of news from corporate press releases and news articles on stock prices. We follow the common market model event study methodology to assess the immediate impact of news releases on stock prices. For each firm i, the abnormal return on day t, ARit is specified as

where Rit and E(Rit|Xt) are the actual and expected return, respectively, for day t.

where Rmt is the day t return on the market portfolio, which we proxy with the SET index. The αi and βi are the ordinary least squares estimates for the regression of the firm i’s daily returns on the market returns over the 200 days prior to the event window.

ARit = Rit − E(Rit|Xt),

ARit = Rit − αi − βiRmt,

The event window lasts from 1 day before to 5 days after the date of the news release. We start the window 1 day before the actual announcement day in order to capture the impact in case the news had leaked to the market just before the actual news was released or published. The next trading day will be used if the press release is published after trading hours. We then compute the average daily abnormal return for each firm i news on day t as

The average abnormal return ) is calculated for each news category across observations and tests to evaluate whether the null hypothesis (H0: = 0) is violated. The event window was kept to seven days (−1 to +5 days); we are interested in the immediate impact of corporate releases and news articles on stock prices. We also wanted to minimize the possibility of other news being released or published within the same window. However, we will discuss the longer event window in Section 6. The results of the test are presented in the next section.

6. Event Study Results

6.1. Empirical Results

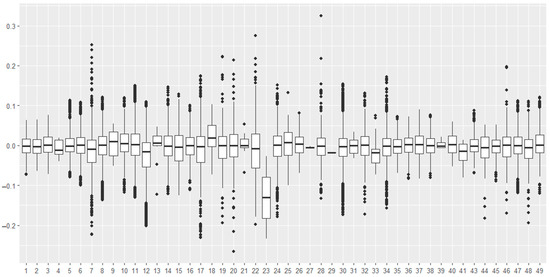

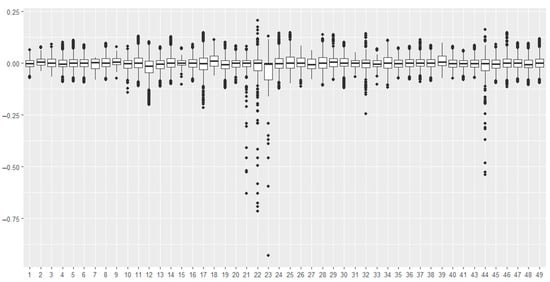

Figure 1 shows the scatter plots of individual CAR observations for each news category for corporate press releases, and Figure 2 shows the scatter plots of individual CAR observations for each news category for news articles. Figure 1 shows a normal distribution across all categories, while Panel B has some categories that are somewhat left skewed, and the explanations are provided in the discussion. Table 5 presents the average CARs and p-values of the tests of H0. For categories containing fewer than 100 observations, the p-values based on nonparametric tests are italicized. The p-values significant at the 10% level for either test are shown in bold. The subcategories with a significant p-value at the 10% level for at least one group are italicized, and the subcategories with significant p-values for both corporate press releases and newspaper articles are shown in bold.

Figure 1.

Scatter plots of individual CAR observations for each news category for corporate press releases.

Figure 2.

Scatter plots of individual CAR observations for each news category for news articles.

Table 5.

Test results for abnormal returns: presents the mean cumulative abnormal return associated with each news category (CAR) for both corporate press releases and newspaper articles computed over the event window [−1, +5] and the p-value for H0: CAR = 0. For categories containing fewer than 100 observations, the p-values based on nonparametric tests are italicized. The p-values significant at the 5% level for either test are in bold. Subcategories with a p-value significant at a 10% level for at least one group are italicized and subcategories with p-values significant for both corporate press releases and newspaper articles are in bold.

Our results in the reported CARs for both corporate press releases and news articles are generally consistent with the findings from previous studies. In our sample, the number of news categories with statistically significant results is substantially larger for news articles (24 subcategories) compared to corporate press releases (11 subcategories). Despite ignoring the four categories where the number of observations for corporate press releases is too small for statistical tests and, as a result, has no comparison, the market reaction to news articles for most qualitative news categories is stronger and more statistically significant when compared to corporate releases. This is most apparent in categories such as awards, compliance, legal, and M&A. This result suggests that news media contributes to price reactions more significantly than corporate press releases for nonfinancial-related news. This finding is in line with the literature on behavioral finance that found news media to contribute to price reactions. A recent study by Guest (2021) examined earnings news coverage by the Wall Street Journal and found that journalists’ editorial content not only increases awareness but also helps investors understand a firm’s earnings. Similar studies by Engelberg and Parsons (2011) found the presence or absence of local media coverage to have a strong relationship to the probability and size of local trading. Dougal et al. (2012) also suggest that financial journalists have the potential to influence investor behavior. Similarly, Fang and Peress (2009) found that the breadth of dissemination (through media) affects stock returns.

On the other hand, the difference in the market reaction to corporate press releases and news articles for financial news categories and profitability-related news under the strategy and performance category shows no significant differences. The CAR from corporate releases on financial results (both weak and strong) and profitability (both declining and improving) are larger in magnitude than that of news articles. This phenomenon is also observed in the releases on season offerings of debt and equity (although debt offering is not significant).

From the different price reactions above, our findings suggest that for news categories that are more qualitative and with impacts more difficult to quantify, the news media helps reduce information asymmetry among market participants by assisting investors in the interpretation and deciphering of the value of the information. Next, we will discuss the observed price impact of key news categories.

- (a)

- Dividend and Financial News

The literature on financial-related announcements and their informativeness on firm value has been long established and studied extensively, starting with seminal works by Ball and Brown (1968). A large number of event studies have provided evidence of the speed of market reaction to financial announcements, particularly on earnings and dividend announcements.

For dividend categories, the results are largely in line with previous and recent findings with dividend decrease or suspension announcements accompanied by negative returns and special/interim dividends accompanied by positive returns (Below and Johnson 1996; Lonie et al. 1996; Kumar 2017). The magnitude of the negative returns from dividend decrease/suspension announcements results in the highest price reaction in the dividend categories. The interim or special dividend, on the other hand, results in a significant increase in returns as it signals the strong cash position of the firm. The corporate announcement of generic dividend announcements shows a slight negative but insignificant impact on price. The impact of news articles on generic dividends shows a significantly positive price reaction, consistent with past studies by Asquith and Mullins (1986), among others.

Financial result announcements and associated price reactions show consistent price reaction patterns across corporate announcements and news article reports with weak financial performance accompanied by a significant negative CAR, while strong financial performance is accompanied by a positive CAR. Our findings show that a weak financial performance solicits a much stronger negative price reaction (behind only noncompliance) among all the categories, consistent with the long-established findings of Fama et al. (1969) that negative information can cause strong price fluctuations by the increasing uncertainty of firm prospects.

From our data, we found that firms seem to shy away from actively preannouncing negative performance and are more active in the preannouncement of positive performance. The number of corporate releases on negative preannouncements stands only at 15 observations. However, the number of news articles on negative preannouncements is much larger and is accompanied by a significant negative price impact. This is consistent with the findings by Solomon and Soltes (2012) that newspapers, not newswires, are more likely to cover negative news. Kothari et al. (2009) also found evidence to suggest that managers accumulate and withhold bad news up to a certain threshold but tend to leak and/or immediately reveal the good news to investors. As a result, the magnitude of the negative stock price reaction to bad news disclosure is greater than that of positive news. Other recent studies reconfirm this phenomenon (Bao et al. 2019).

On the other hand, the number of corporate releases on positive preannouncements has a much larger number of observations and is accompanied by a positive price reaction, though not statistically significant. We suspect that since the preannouncement of performance is a voluntary disclosure, the news about stronger performance is already reported through other less formal channels and acknowledged by the market before actual corporate releases/announcements. This is consistent with the findings by Kothari et al. (2009) and is reflected in the much more significant price impact associated with preannouncements from news media. This phenomenon has also been reported in another study by Solomon and Soltes (2012), demonstrating that investment relation firms “spin” their clients’ news and help generate more media coverage of positive corporate releases than negative releases and that this spin increases announcement returns.

For the debt or equity offerings categories, any issuance of these instruments signals to the market that the firm is short on cash. Specifically for equity offering, it also signals to the market that the current firm value is overpriced. As a result, the news of debt and equity issuance is met with adverse price reactions regardless of the information source, be it from corporate releases or news articles. From our sample, on average, debt issuance results in an approximately −0.1% price reaction, and equity issuance results in a much higher and significant price impact of −0.902% from corporate releases and −0.601% from news articles. Our findings on equity issuance are consistent with the results of earlier research. Asquith and Mullins (1986) reported that, for their sample of 128 seasoned equity offerings, the price impact is negative. Similarly, Masulis and Korwar (1986) reported, on average, a negative stock price change from the announcement of underwritten common stock offerings.

Other news categories in the dividend and financial categories confirm previously reported regularities, with restatements and share buybacks accompanied by positive price adjustments. Although corporate releases on share buybacks elicit a strong positive price reaction, the number of announcements is small and the results are insignificant. However, the price reaction from news articles, although smaller, is significant, since companies only declare their share repurchase plans after these are authorized by the board, but are not required to, and typically do not disclose the specific dates on which they will execute trades. As a result, the actual repurchase is only reported after the action has occurred.

- (b)

- Strategy and performance

Although prior research has shown both positive and negative market reactions to credit-related news, corporate press releases and news articles related to credit news in our sample, be it positive or negative credit news, were accompanied by a negative price reaction. Specifically, positive credit news shows a statistically significant value for the negative price reaction from both news sources. This is consistent with studies like that of Howton et al. (1998), which illustrate the relationship between debt issuance and a lack of cash sending a negative signal to the market on the company’s position.

Like financial performance announcements, news releases that relate to improving/declining profitability trends are accompanied by significant corresponding positive/negative price adjustments. This news typically reflects the prospects of the firm due to environmental changes (e.g., reduction in consumer purchasing power or increase in prices of key inputs) or company-specific actions (e.g., improved efficiency). Again, negative news tends to have a more significant price reaction than positive news. Also, corporate releases of declining profitability solicit a larger negative reaction. This is consistent with findings that firms shy away from releasing bad news. When they do, it is due to either the mandatory requirements by the regulators that they must release news that could have a “significant” or “major” impact (Kothari et al. 2009; Skinner 1994) or to preempt negative earnings surprises (Skinner 1994). Both of which signal a negative outlook for the firm.

- (c)

- Other news categories

From our observation, corporate releases regarding company awards had a negative price reaction. This is consistent with many studies that demonstrated a negative abnormal return to awards-related news. A study by Fernández et al. (2011) found no effect with regard to firm awards and prizes on European firms. Similarly, another study by Lyon et al. (2013) finds that the firms winning Green Company Awards in China from 2008 to 2011 resulted on average in an insignificant price impact and, in some cases, even had significant adverse effects on shareholder value. Other studies that found negative market reactions to awards include the research of Tippins and Kunkel (2006), who studied advertising awards, and that of Jacobs et al. (2010), which examined environmental awards and certificates. Another possible explanation for the negative price reaction to company awards news is the strategic reporting of good news after bad news, as suggested by Segal and Segal (2016), who provided evidence of managers strategically managing the timing of voluntary releases and news bundling.

Corporate releases on customer gains or losses are accompanied by price reactions that are in line with conventional wisdom. Customer wins and new partnerships are followed by positive price reactions, while customer loss that can result in reduced revenue is accompanied by a negative price reduction.

Moving on to legal and compliance news, lawsuits have uncertainties and indicate potential penalties for the firm. The negative price reactions to legal problems are, thus, expected. For the conclusion or settlement of legal problems, the negative price reaction from our observations reflects the potential damage resulting from the legal problems. For corporate releases on legal problems and legal problem conclusions, we found negative price reactions to both categories, though statistically insignificant. However, the price reaction from news articles is not only larger but also significant. This again reflects findings from Wu and Lin (2017) that show that the majority of positive or negative media coverage is significantly related to similar signed abnormal returns.

The market reaction to corporate releases relating to compliance and return to compliance is accompanied by substantial price impact but is not statistically significant. This can be expected as news related to compliance and return to compliance are typically preceded by corporate actions that violate the necessary rules or actions that return it to compliance. However, in our case, the significant negative price reaction from returning to compliance is found to be related to a significant violation of regulations due to poor performance, even when those firms return to compliance and their stocks are allowed to be traded again. The stock price reflects the new fair value of the firm because of poor performance. As will be seen in our longer time period analysis, the price impact of a return to compliance continues to drift over the long period of post-corporate release and news report dates.

Merger and acquisition (M&A) is another major category. A merger is an event where two firms of equal stature merge and result in a new firm. Acquisition is when one firm takes ownership of another, and typically only the acquirer’s name remains after the acquisition. Our corporate release observations found a negative reaction to announcements of acquisition certainty and a positive stock price reaction to the announcements of acquisition intent. The news articles show a positive price reaction to both acquisition certainty and acquisition intent, However, the price impact from both corporate releases and news articles was not statistically significant.

A spin-off is a form of firm divestment of its subsidiaries but is distinct from other divestments, in that it results in the creation of a new independent entity from the parent company. Often, the parent company will continue to hold a significant number of shares in the spin-off entity. News related to spin-offs results in a positive price reaction, be it from corporate releases or news articles. This is consistent with many prior pieces of research on the market reaction to spin-off announcements (e.g., Johnson et al. 1994; Truong 2017). However, the results from our observations are only statistically significant for news articles. Management often openly discusses corporate intent to spin off its subsidiaries. Furthermore, formal disclosure is usually carried out after the deal has been finalized. As such, it is no surprise that the price reaction to news articles has more significant results than corporate releases.

On corporate releases related to management or organizational change, studies have shown that changes in management, depending on the situation and context of the change, could be good, bad, or neutral news for the firm. Huson et al. (2004) found that executive turnover announcements are associated with significantly positive average abnormal stock returns, while Charitou et al. (2010) found positive abnormal returns around the announcement of an outside CEO appointment. On the other hand, Lin et al. (2003) found the average market reaction to directors’ appointment announcements to be indistinguishable from zero. Finally, Charitou et al. (2010) found cumulative abnormal returns to be negative following the CEO’s departure. Our observations indicate, on average, a negative price reaction across all management subcategories, be it appointment, promotion, reorganization, retirement, or termination, for both corporate releases and news articles. Only corporate releases related to management addition, termination, and news articles related to promotion solicited a statistically significant negative price impact.

As our classification across all subcategories does not distinguish between CEO, management, or directors, and the breakdown is beyond the scope of this study, we will refrain from drawing conclusions on specific management positions from our results. However, the majority of negative price reactions across the subcategories seem to suggest that any volatility in management can cause uncertainty and result in negative price reactions.

Finally, under the product category, the price reactions to both corporate releases and news articles in all the news categories are mixed but the results are not significant, except for news articles on product defects that are, as expected, accompanied by a significant negative price reaction.

6.2. Longer Event Window

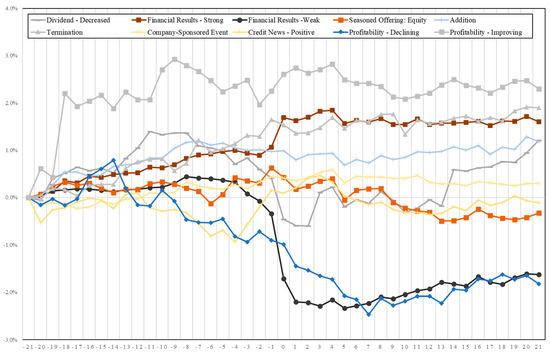

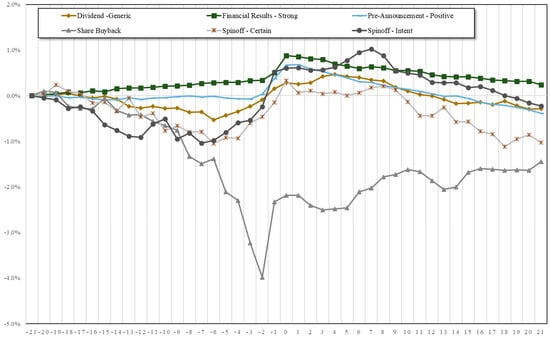

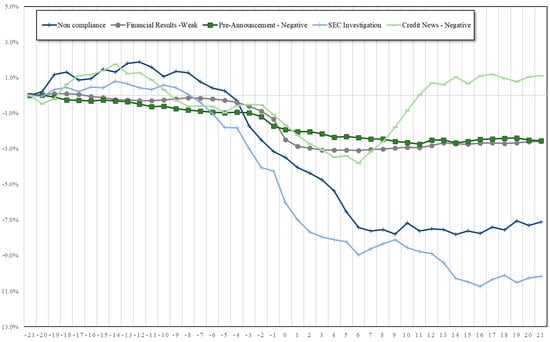

As discussed in the previous section, understanding the immediate impact surrounding announcement day gives us an understanding of how the news might immediately affect the share price in both direction and magnitude. However, it is equally important to understand whether these price impacts are permanent or only temporary. If the news contains new information that reshapes the thinking of investors on the value of the firm, this should result in a permanent or sustained price impact. However, if the news does not contain new information or investors overreact to the news, the price impact should reverse quickly. A longer event window before the announcement date could also give us an indication of whether the news had been “leaked” prior to the announcement. In this case, the price impact would have been realized before the announcement, and the information value on the announcement date would have been diminished. Figure 3 plots the CARs for all statistically significant abnormal returns for corporate releases, while Figure 4 and Figure 5 plot the CARs for the top seven positive/negative and statistically significant abnormal returns for news articles, calculated over the period ranging from 21 trading days before to 21 trading days after news announcements [−21, +21] or approximately one calendar month before and after news announcements.

Figure 3.

Corporate press releases: all statistically significant abnormal returns.

Figure 4.

News articles: top six positive and statistically significant abnormal returns.

Figure 5.

News articles: top five negative and statistically significant abnormal returns.

6.2.1. Corporate Press Releases

Our observations on corporate releases (Figure 3) show that corporate news releases related to financial performance have a more permanent price reaction. We see the highest price reaction on the announcement date for both the strong and weak financial results. However, we observe a gradual price movement for the strong financial result before the announcement date. For weak financial results, we do not see a gradual price movement like that of strong financial results before the announcement. Instead, the biggest movement occurs on the announcement date. Research has shown that firms often leak good news prior to a formal announcement but shy away from leaking bad news until absolutely necessary (Begley and Fischer 1998; Chambers and Penman 1984; Kothari et al. 2009). Kothari et al. (2009) found that managers disclose bad news promptly but good news gradually. This study also found the market reaction to good and bad news to be asymmetric and consistent with management delaying the disclosure of news relative to good news. These findings are further reflected by our observations in the “credit news—positive” category, where the price impact seems to have occurred almost a week before the announcement (4 days preannouncement, to be exact), leaving a minimal price impact on the announcement date.

Other categories that also display an early price movement before the announcement dates are the profitability declining/improving categories. However, this is expected as news on indicators, such as prices of raw materials or labor prices going up/down, that could affect firm profitability would have been reported.

Overall, our observations show that corporate press releases have new information value as the CAR plots fan out in the corresponding direction related to the corporate release on the announcement day. Most of the price movement also appears to be permanent. This is especially true for positive categories like strong financial results and special dividends. For special dividends, although there seems to be some volatility in price over the first few days post-announcement, the price impact is sustained at least a month after the announcement. For weak financial results, the negative price impact is much more acute on the corporate release date and the impact is prolonged.

6.2.2. News Articles

For news categories with a positive price impact (Figure 4), in most categories (except for positive preannouncement and share buyback), we see a similar premovement of returns long before the news was reported. Similar to corporate press releases, the price movement for strong financial results shows an upward trend long before the news report date. Other categories exhibit the same behavior only about a week before the news report date. This reconfirms the phenomenon that firms often leak good news prior to a formal announcement, as reported in the corporate release section. However, we see a different trend for positive news articles post-news releases than that for corporate press releases. For corporate press releases, the positive price impact seems to hold and does not show signs of reversing. However, in news articles, our observations show that the positive price effect begins to reverse for almost all top seven positive and statistically significant categories. The reversal went back to nearly the same level before the news report about a month after the news release date. This phenomenon was also observed by Tetlock (2011), who found the market reaction to stale news stories to partially reverse in the next week. With firms more inclined to issue good news over bad news, it is possible that “old” news is being rereported. This also supports the finding that individual investors can overreact to stale information, leading to a temporary movement of asset prices (Birz 2017).

We see a different long-term price impact from news articles for categories with a negative price impact (Figure 5), unlike positive news where, for most categories, the upward price trend is seen as early as 7 to 15 trading days before the news report date. Most news categories with a negative price impact only see a downward trend 1–2 days before the actual news report date. Another difference is that the price impact of this negative news is sustained, which is a similar pattern observed in negative corporate releases. Since managers are unlikely to recycle negative news, this sustained market impact indicates that there is real information value in the negative news articles reported. The only two categories that showed early negative trends are “noncompliance” and “SEC investigation”, which can be expected as the news of noncompliance or investigation would have come after some violation events had been reported.

A finding from our sample that differs from our expectations concerns the “return to compliance” news category. Contrary to the observations in prior studies that found the price reaction to be positive post-return-to-compliance announcements, we see a significant negative price drift post-news articles on return to compliance. Upon further investigation, we found that this is driven by a group of stocks that failed compliance due to performance issues and, when they return to compliance, the market adjusts their valuation to reflect the fundamental value of those firms.

Overall, the longer time period analysis illustrated that there are differences in how corporate press releases and news articles impact price. Corporate releases have a more permanent price impact post-news releases across both positive and negative news, which indicates that there is new information value in the corporate press releases that can cause a change in the view of the market on the fundamental value of the firm. Also, for corporate press releases, news on strong financial results shows a tendency to have been “leaked” well before the announcement date, while news of weak financial results is less likely to be leaked.

News articles show a different longer time period behavioral pattern. Unlike positive corporate news, the price impact from positive news articles shows a reversal in the longer time period. This indicates that firms might issue or recycle positive news that does not have new information value, and the market does react to this stale news in the short term with a price reversal to a fundamental value in the longer term. On the other hand, firms are unlikely to recycle negative news; as such, it is more likely that there is new information value in negative news articles. Hence, we see a sustained price impact for negative news articles that is similar to corporate press releases.

Given this insight, regulators should raise the awareness of the investing public on the possible recycling of good news by the news media for the potential benefit of the corporations. Investors should also be weary and recheck good news published in the news media to ensure it is not a recycling of stale news.

7. Conclusions

This paper expands the existing literature on share price reactions to corporate press releases and news articles published by the news media. We collected a unique set of corporate releases and news articles representing a comprehensive set of news categories. This unique information set allowed us to conduct event studies across corporate press releases and news articles for multiple news categories for the same period. The results allowed us to compare and generate insights into the differences in the market reaction to corporate press releases and news articles. This paper provides theoretical and practical contributions to the limited literature on the market reactions to corporate press releases and news media in less developed markets. First, we expanded on previous studies by providing a direct comparison of the price impact differences between corporate releases and media news reports across news categories for the same time period. Second, we explored the price reaction over longer event windows for corporate releases and news articles and showed that there are differences in market reaction over a longer time period. Third, we investigated whether the regularities of price reaction to news events in prior studies across corporate releases and media news reports for developed markets hold true for a developing capital market, like Thailand. Lastly, this paper also provides practical contributions, particularly on suggestions for regulatory agencies to increase awareness of the investing public on how the news media can impact share prices. Particularly, in regard to the potential recycling of good news by the news media for the benefit of corporations.

We found that news media reports result in more statistically significant price reactions than corporate releases for qualitative news categories, such as awards, compliances, legal, or products. Furthermore, we found evidence that positive news tends to leak while negative news is delayed. We also found that the price impact of corporate releases is sustained in both positive and negative news categories. Our results also reconfirm previous findings that the positive price impact for news reported by the media tends to reverse, which is consistent with prior studies by Tetlock (2011) and Birz (2017). In contrast, the negative price impact of news articles seems to hold, and this result is different from the results of the aforementioned studies. Finally, our results show that market reactions to most news categories in Thailand are consistent in direction with those of studies conducted in developed markets.

Our paper has some limitations. Our data set comprises the corporate press releases and news articles of listed firms in the SET and MAI. As such, the corporate activities reported reflect the activities of Thai corporations. Although all reported news categories are consistent with business activities elsewhere, there are some business activities that are underrepresented or missing in the Thai business environment. For example, the pharmaceutical industry is underrepresented in the Thai Stock Market, with only seven out of over six hundred firms in our sample. As such, we do not have sufficient information to draw insights into news categories that are specific to this industry (e.g., drug patent approval).

Finally, our paper points to some future areas of research. We recognize that corporate press releases and news articles are not the only mechanisms by which a firm communicates with investors. Future research could examine and compare the impacts of other avenues through which firms communicate with investors, such as social media or analyst calls. Our finding that news articles on qualitative news seem to have a more statistically significant price impact when compared to corporate press releases also begs the question as to why this seems to be the case. We hypothesize that this could be because the qualitative nature of the information makes it difficult to quantify and because the news media plays a role in helping to digest and “quantify” this qualitative information for investors. Further research in these areas would help further our understanding of the dynamic relationship between management disclosures, media, and financial markets.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.S. and L.A.; methodology, L.S. and L.A.; validation, L.S.; formal analysis, L.S.; data curation, L.S.; writing—original draft, L.S.; writing—review and editing, L.S. and L.A.; supervision, L.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | CG Watch 2020, published by the Asian Corporate Governance Association. |

| 2 | The Global Competitiveness Report 2017–2018, published by the World Economic Forum. |

References

- Ahern, Kenneth R., and Denis Sosyura. 2014. Who writes the news? Corporate press releases during merger negotiations. The Journal of Finance 69: 241–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Khurshid, JingGuang Han, Elaine Hutson, Colm Kearney, and Sha Liu. 2016. Media-expressed negative tone and firm-level stock returns. Journal of Corporate Finance 37: 152–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akerlof, George A. 1978. The market for “lemons”: Quality uncertainty and the market mechanism. In Uncertainty in Economics. Cambridge: Academic Press, pp. 235–51. [Google Scholar]

- Akerlof, George A., and Robert J. Shiller. 2010. Animal Spirits: How Human Psychology Drives the Economy, and Why It Matters for Global Capitalism. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Antweiler, Werner, and Murray Z. Frank. 2006. Do US Stock Markets Typically Overreact to Corporate News Stories? Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=878091 (accessed on 17 August 2023).

- Asquith, Paul, and David W. Mullins Jr. 1986. Signalling with Dividends, Stock Repurchases, and Equity Issues. Financial Management 15: 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atiase, Rowland K., Haidan Li, Somchai Supattarakul, and Senyo Tse. 2005. Market reaction to multiple contemporaneous earnings signals: Earnings announcements and future earnings guidance. Review of Accounting Studies 10: 497–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Malcolm, and Jeffrey Wurgler. 2007. Investor sentiment in the stock market. Journal of Economic Perspectives 21: 129–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, Ray, and Philip Brown. 1968. An Empirical Evaluation of Accounting Income Numbers. Journal of Accounting Research 6: 159–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Dichu, Yongtae Kim, G. Mujtaba Mian, and Lixin Su. 2019. Do managers disclose or withhold bad news? Evidence from short interest. The Accounting Review 94: 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Barber, Brad M., and Terrance Odean. 2008. All that glitters: The effect of attention and news on the buying behavior of individual and institutional investors. The Review of Financial Studies 21: 785–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberis, Nicholas, and Richard Thaler. 2003. A survey of behavioral finance. Handbook of the Economics of Finance 1: 1053–128. [Google Scholar]

- Begley, Joy, and Paul E. Fischer. 1998. Is there information in an earnings announcement delay? Review of Accounting Studies 3: 347–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Below, Scott D., and Keith H. Johnson. 1996. An analysis of shareholder reaction to dividend announcements in bull and bear markets. Journal of Financial and Strategic Decisions 9: 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Bing, Li, Keith C. C. Chan, and Carol Ou. 2014. Public sentiment analysis in twitter data for prediction of a company’s stock price movements. Paper presented at 2014 IEEE 11th International Conference on e-Business Engineering, Guangzhou, China, November 5–7; pp. 232–39. [Google Scholar]

- Birz, Gene. 2017. Stale economic news, media and the stock market. Journal of Economic Psychology 61: 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, Johan, Huina Mao, and Xiaojun Zeng. 2011. Twitter mood predicts the stock market. Journal of Computational Science 2: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botosan, Christine A. 1997. Disclosure level and the cost of equity capital. Accounting Review 72: 323–49. [Google Scholar]

- Boudoukh, Jacob, Ronen Feldman, Shimon Kogan, and Matthew Richardson. 2019. Information, trading, and volatility: Evidence from firm-specific news. Review of Financial Studies 32: 992–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, Anne E., and Stephen H. Penman. 1984. Timeliness of reporting and the stock price reaction to earnings announcements. Journal of Accounting Research 2: 21–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Wesley S. 2003. Stock price reaction to news and no-news: Drift and reversal after headlines. Journal of Financial Economics 70: 223–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charitou, Melita, Andreas Patis, and Adamos Vlittis. 2010. The market reaction to the appointment of an outside CEO: An empirical investigation. Journal of Economics and International Finance 2: 272–77. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, Theodore E., Toni Q. Smith, and Pamela S. Stuerke. 2004. Public pre-disclosure information, firm size, analyst following, and market reactions to earnings announcements. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting 31: 951–84. [Google Scholar]

- Chuthanondha, Siriyos. 2020. Do managements tell us the whole truth and nothing but the truth? Impact of textual sentiment in financial disclosure to future firm performance and market response in Thailand. International Journal of Monetary Economics and Finance 13: 244–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellavigna, Stefano, and Joshua M. Pollet. 2009. Investor inattention and friday earnings announcements. Journal of Finance 64: 709–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, Douglas W. 1984. Financial intermediation and delegated monitoring. The Review of Economic Studies 51: 393–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougal, Casey, Joseph Engelberg, Diego Garcia, and Christopher A. Parsons. 2012. Journalists and the Stock Market. Review of Financial Studies 25: 639–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, Jeffrey T., and Matthew J. Magilke. 2009. The timing of earnings announcements: An examination of the strategic disclosure hypothesis. Accounting Review 84: 157–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Shuili, and Kun Yu. 2021. Do corporate social responsibility reports convey value relevant information? Evidence from report readability and tone. Journal of Business Ethics 172: 253–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easley, David, and Jon Kleinberg. 2010. Networks, Crowds, and Markets: Reasoning about a Highly Connected World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Easley, David, Nicholas M. Kiefer, Maureen O’hara, and Joseph B. Paperman. 1996. Liquidity, information, and infrequently traded stocks. The Journal of Finance 51: 1405–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelberg, Joseph E., and Christopher A. Parsons. 2011. The Causal Impact of Media in Financial Markets. The Journal of Finance 66: 67–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, Eugene F., Lawrence Fisher, Michael C. Jensen, and Richard Roll. 1969. The adjustment of stock prices to new information. International Economic Review 10: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Lily, and Joel Peress. 2009. Media coverage and the cross-section of stock returns. Journal of Finance 64: 2023–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, Beatriz Cuellar, Yolanda Fuertes Callén, and José Antonio Laínez Gadea. 2011. Stock price reaction to non-financial news in European technology companies. European Accounting Review 20: 81–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feuerriegel, Stefan, and Nicolas Pröllochs. 2021. Investor reaction to financial disclosures across topics: An application of latent Dirichlet allocation. Decision Sciences 52: 608–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Meng, and Jiekun Huang. 2020. Informing the market: The effect of modern information technologies on information production. The Review of Financial Studies 33: 1367–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentzkow, Matthew, and Jesse M. Shapiro. 2010. What drives media slant? Evidence from US daily newspapers. Econometrica 78: 35–71. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, Chinmoy, and J. Randall Woolridge. 1988. An analysis of shareholder reaction to dividend cuts and omissions. Journal of Financial Research 11: 281–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, John M., Nicholas H. Hirschey, and Patrick J. Kelly. 2011. How important is the financial media in global markets? The Review of Financial Studies 24: 3941–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, Nicholas M. 2021. The Information Role of the Media in Earnings News. Journal of Accounting Research 59: 1021–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haggard, K. Stephen, Xiumin Martin, and Raynolde Pereira. 2008. Does voluntary disclosure improve stock price informativeness? Financial Management 37: 747–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermalin, Benjamin E., and Michael S. Weisbach. 2012. Information Disclosure and Corporate Governance. The Journal of Finance 67: 195–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmström, Bengt. 1979. Moral hazard and observability. The Bell Journal of Economics 10: 74–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howton, Shawn D., Shelly W. Howton, and Steven B. Perfect. 1998. The market reaction to straight debt issues: The effects of free cash flow. Journal of Financial Research 21: 219–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huson, Mark R., Paul H. Malatesta, and Robert Parrino. 2004. Managerial succession and firm performance. Journal of Financial Economics 74: 237–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, Thanh D., and Daniel R. Smith. 2017. Stock price reaction to news: The joint effect of tone and attention on momentum. Journal of Behavioral Finance 18: 304–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, Brian W., Vinod R. Singhal, and Ravi Subramanian. 2010. An empirical investigation of environmental performance and the market value of the firm. Journal of Operations Management 28: 430–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jegadeesh, Narasimhan, and Joshua Livnat. 2006. Revenue surprises and stock returns. Journal of Accounting and Economics 41: 147–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, George Alfred, Robert M. Brown, and Dana J. Johnson. 1994. The market reaction to voluntary corporate spinoffs: Revisited. Quarterly Journal of Business and Economics 33: 44–59. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Michael J., James P. Naughton, Ahmed Tahoun, and Clare Wang. 2018. Do firms strategically disseminate? Evidence from corporate use of social media. The Accounting Review 93: 225–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, Daniel, and Amos Tversky. 2013. Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. In Handbook of the Fundamentals of Financial Decision Making: Part I. Singapore: World Scientific, pp. 99–127. [Google Scholar]

- Kothari, Sabino P., Susan Shu, and Peter D. Wysocki. 2009. Do managers withhold bad news. Journal of Accounting Research 47: 241–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Satish. 2017. New evidence on stock market reaction to dividend announcements in India. Research in International Business and Finance 39: 327–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Spencer Yongwook, and Johnny Tang. 2020. Extreme Events and Overreaction to News. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3724420 (accessed on 17 August 2023).

- Lang, Mark, and Russell Lundholm. 1993. Cross-sectional determinants of analyst ratings of corporate disclosures. Journal of Accounting Research 31: 246–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]