1. Introduction

Pension funds collect, pool, and invest funds contributed by the sponsors and their members to provide beneficiaries with an appropriate retirement income in the future (

Davis 1995). As such, they are also financial intermediaries that convert household savings into investment. They allow households to smooth their consumption over very long periods (

Barr and Diamond 2006;

Kadarisman and Wahyuni 2010) and provide investment capital to the economy (

Thomas and Spataro 2016;

Bijlsma et al. 2018). The key issue for pension funds is, therefore, how efficiently they perform this intermediation function for both the providers (i.e., the pension funds’ participants) and users of capital. Pension funds’ inefficiency raises the costs of investments capital for firms; moreover, inefficiency in pension funds’ management reduces the retirement benefits of participants, increasing the amount that they need to save to provide for their retirement and, therefore, reducing their consumption.

In this respect, many developing countries have tried to reform their pension funds to increase the efficiency of their pension systems. For example, Indonesia started its reform by passing Act No. 11 of 1992 concerning Pension Funds. After the 2008 financial crisis, the Indonesian government gradually intensified its reform by stipulating the pension fund industry to adopt best and internationally standardized governance practices. Numerous crucial acts and regulations have been amended, including the Financial Services Authority or FSA (OJK—Otoritas Jasa Keuangan) (Act No. 21/2011); National Social Insurance Agency (BPJS—Badan Penyelenggara Jaminan Sosial) (Act No. 24/2011); pension fund administrators’ competence and integrity (FSA Regulation No. 4/2013); information transparency (FSA Regulation No. 7/2013); investment portfolio allocation (FSA Regulation No. 3/2015); and pension funds’ obligation to allocate their investments at least 30% to government securities (SBN—Surat Berharga Negara) (FSA Regulation No. 1/2016).

Despite the ongoing reform, the Indonesian pension fund industry demonstrates an alarming phenomenon.

Table 1 presents the Indonesian pension fund industry’s current situation. In particular, employers freeze their employer pension funds or EPFs (

DPPK—Dana Pensiun Pemberi Kerja), convert their defined benefit plans (

PMP—Program Manfaat Pasti) into defined contribution plans (

PIP—Program Iuran Pasti), and even dissolve their pension funds. Several factors explain these phenomena, including sponsors’ financial difficulties, the presence of mandatory pension fund programs from Employment

BPJS, and more importantly, EPFs’ internal inefficiency and performance stagnation (

Mangkoesoebroto 2017). Hence, it is crucial to empirically investigate the efficiency of Indonesian EPFs and their determinants to increase their efficiency, thereby optimizing their contribution to the economy.

Empirical references on pension funds’ efficiency remain relatively limited. Most prior studies have focused on developed countries, including the Netherlands (

Alserda et al. 2018;

Bikker 2017) and Australia (

Bui et al. 2016;

Galagedera 2017). Studies on developing countries still focus on European or Latin American countries, such as Poland (

Karpio and Zebrowska-Suchodolska 2016), Turkey (

Gokoz and Çandarli 2011), Croatia (

Draženović et al. 2019), or Chile (

Barrientos and Boussofiane 2005;

Guillen 2008). Pension funds’ efficiency in Asia, especially in Indonesia, remains relatively understudied. For example,

Asher and Bali (

2015) conducted general assessments on ASEAN countries’ pension funds but did not focus on Indonesian pension funds’ efficiency. Similarly,

Guerard (

2012) only reviewed the Indonesian pension system reform but did not focus on efficiency in pension funds. Based on the recent phenomena of pension funds’ decreasing performance and prior efficiency research, this study seeks to evaluate and investigate the Indonesian EPFs’ technical efficiency and their determinants.

Methodologically, this study employs the non-parametric data envelopment analysis (DEA) method to measure the performance of pension funds. The DEA method has been widely used in studies on pension funds’ efficiency (

Bui et al. 2016;

Draženović et al. 2019). This method identifies a decision-making unit or DMU’s inefficiency by comparing it with other efficient DMUs (

Coelli et al. 2005). A traditional DEA approach, however, considers the production process a ‘black box’ without sufficient details to identify sources of inefficiency (

Färe and Grosskopf 2000;

Cook et al. 2010). New studies about pension fund performance consider the structure of pension funds as a network (

Galagedera 2017;

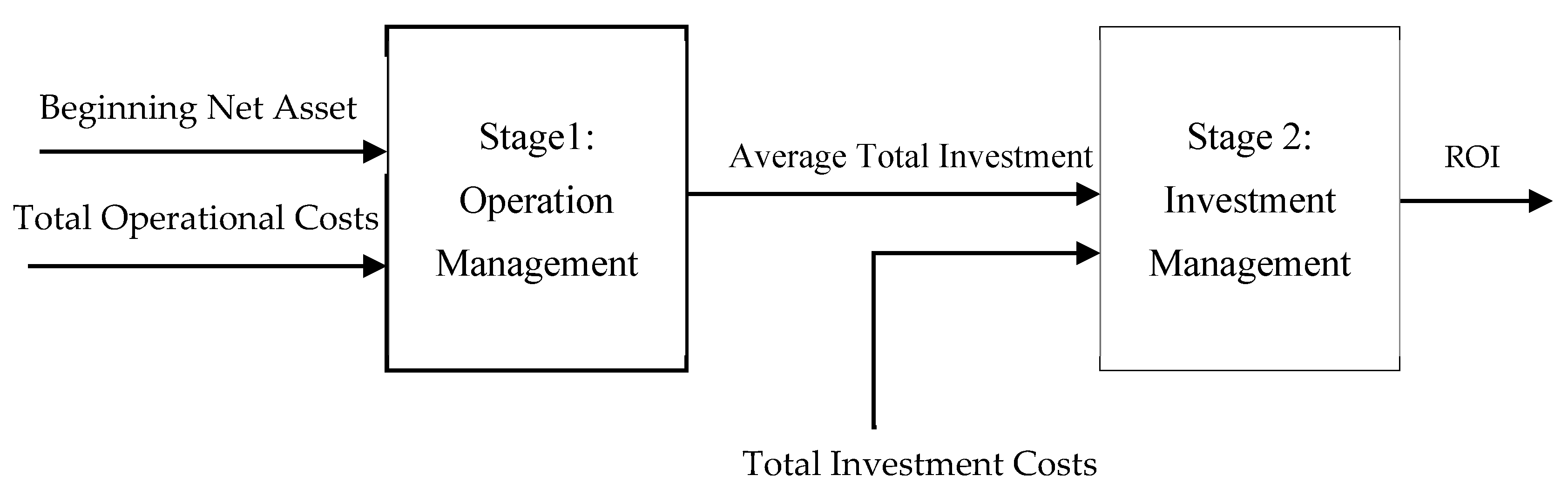

Lin et al. 2021); therefore, we chose to apply the two-stage additive network DEA in our study. In particular, in this research, we conceptualize the management function of employer pension funds (EPFs) as a serially linked dual sub-process, i.e., operational management and investment management (

Galagedera 2017). This approach is beneficial because it allows us to evaluate not only the overall performance of the EPFs, but also the performance of their components, i.e., operation management and investment management.

We combine network DEA with a second stage regression analysis to determine factors explaining EPFs’ efficiency level, by adopting the technique used in

Simar and Wilson (

2007).

Simar and Wilson (

2007) proposed a bootstrap procedure coupled with truncated regression to mitigate the ambiguous data generating process and serial correlation problem in efficiency scores, thereby providing more statistically valid inference results.

This study has some contributions. First, in terms of method, this study is (to the best of our knowledge) the first to apply the two-stage additive network DEA to evaluate the EPFs industry. Previous studies have generally used traditional methods to assess EPFs’ performance, such as the risk-adjusted method (

Hasanudin et al. 2017), ratio analysis (

Sunaryo et al. 2020), or conventional DEA (

Seran et al. 2022). Thus, this study extends the application of the method to EPFs, while at the same time, introducing the method as a useful alternative to the traditional method for measuring EPFs’ performance.

Second, using a two-stage additive network model, we are able to break down the EPFs management process into two stages, i.e., operations management and investment management, and evaluate them accordingly.

Third, this study proposes a projection analysis model that can be used as a practical guideline for EPFs to improve their performance.

Fourth, this study also conducts a regression analysis by adopting the procedure of

Simar and Wilson (

2007) to examine the correlation between pension funds’ efficiency and their specific characteristics (i.e., size, plan type, and ownership), finding that size and ownership are important characteristics that determine the performance of EPFs in Indonesia.

This article is organized as follows.

Section 2 presents an overview of the Indonesian pension funds industry.

Section 3 is the literature review.

Section 4 discusses the methods.

Section 5 presents the results, and

Section 6 is the conclusion.

2. Overview of the Indonesian Pension Industry

The history of the Indonesian pension funds system can be traced back to the Dutch colonial era. Dutch colonial companies provided old age benefits (THT) for their employees based on the so-called Arbeiderfondsen Ordonnantie of 1926. Long after Indonesian independence in 1945, the provision of pensions for employees still referred to the same legal framework. It was only in 1992 that the government passed the Pension Fund Act (UU) (Number 11 of 1992) about Employer Pension Funds (EPFs) and Financial Institution Pension Funds (FIPFs). EPFs and FIPFs are voluntary pension funds. In 2004, Law No. 40 of the National Social Security System (SJSN) was passed, mandating the government to seek a mandatory basic pension for the general public. This was realized in 2011 with the establishment of the Badan Penyelenggara Jaminan Sosial—National Social Insurance Agency (BPJS) (Law Number 24 of 2011) as a government agency tasked with administering and managing the pension benefit program (JP) for the general public. The JP is a fully funded, defined benefit plan and is mandatory for the working population. The JP has been in effect since July 2015. Currently, the JP contribution is 3% of an employee’s monthly salary, of which 2% is borne by the employer and 1% is borne by the employee. In 2017, the number of JP participants was 10.63 million, and its assets amounted to IDR 25.67 trillion.

The presence of JP BPJS complements one of the important pillars in the Indonesian pension system. When viewed based on the “five pillars” model from the World Bank (

Holzmann and Hinz 2005;

Holzmann 2013), Indonesia’s current pension system consists of three pillars. “Pillar Zero”, consists of government subsidies or social assistance to the poor and elderly, according to the SJSN Law No. 40 of 2004. The “second pillar” includes the mandatory JP BPJS program and the pension for civil servants and military/police officers. The “third pillar” covers voluntary pension funds, as stipulated in Pension Law No. 11 of 1992, i.e., EPFs and FIPFs. Based on the World Bank’s “five pillars” model, the first pillar, i.e., a non-contributory mandatory defined benefit plan, is absent from the Indonesian pension system.

This study focuses on EPFs, which belong to the third pillar in the Indonesian pension system. In the context of Indonesian law, only pension funds on the third pillar, i.e., EPF and FIPF, are referred to as “Pension Funds”. EPF and FIPF are legal entities established with the sole objective of providing pensions benefits for their participants. In this respect, the JP from BPJS is not a “pension fund” but simply a pension benefit program administered by BPJS; BPJS is also not a “pension fund” because it administers not only a pension benefit program, but also other social security programs such as a health insurance program and other social security programs.

The EPF is established by an employer, whether in the form of a defined benefit or defined contribution plan. The membership is limited to the employees of the firm or the employees of its founding partners. Meanwhile, FIPF is an open membership, defined contribution plan established by a bank or an insurance company. EPF (also FIPF) is run based on the principles of freedom, funding, separation of wealth, postponed benefits, portability, vesting rights, and government supervision and guidance (

Siswosudarmo 2010).

EPF management is carried out by a board of trustees appointed by the founder of the pension fund. The board members usually consist of senior employees who are competent in pension funds management. Pension benefits are only paid when a participant has reached retirement age. In the case of pension benefits from a defined contribution EPF, the payment of pension benefits is transferred to an insurance company through the purchase of an annuity. Pension benefits are tax protected. A participant can transfer to another pension fund (principle of portability).

In 2017, the total number of voluntary pension funds (third pillar) was 244, consisting of 220 EPFs and 24 FIPFs. FIPFs are much smaller in number than EPFs, but they have more participants. The total number of voluntary pension participants in 2017 was 4.46 million, of which 3.1 million were FIPFs’ participants, and only 1.4 million were EPFs’ participants. However, in terms of asset value, EPFs are still the largest with a total net asset value of 71.12% (IDR 185.5 trillion), compared to FIPFs, which only have a net asset value of IDR 75.4 trillion or (29%) IDR 260.83 trillion, i.e., the total net assets of all voluntary pension funds (EPFs + FIPFs). When compared to JP BPJS, the asset value of EPFs is greater than that of JP BPJS (IDR 185.5 versus 25.67 trillion), even though the number of JP BPJS participants was greater than EPF (10.63 million versus 1.4 million) participants in 2017. Thus, EPFs are still an important component of the Indonesian pension industry.

6. Conclusions

Pension funds manage funds contributed by members and employers with the aim of providing sufficient benefits for each member upon retirement. In this respect, efficiency is an important issue for EPFs. This study measures and evaluates the performance of Indonesian EPFs within the framework of the two-stage additive network DEA method. Compared to the conventional DEA approach, which treats a firm as a black box so that it can only measure overall performance, the network DEA method enables us to measure the performance of Indonesian EPFs from various aspects of their management function, i.e., operational efficiency and investment efficiency. This is considered the strength of this methodology, namely, being able to measure the performance of pension funds based on the internal structure of the management processes. Thus, it can identify which management functions need to be given greater attention, in order to improve overall performance.

The results of this study can be summarized as follows. First, the average overall efficiency level of EPFs in the 2011–2017 period was 70.9%. When decomposed into operational efficiency and investment efficiency, it was found that EPFs perform better in operational management (81.4%) than in investment management (only 60.4%). Thus, it was identified that investment inefficiency is the main source of the overall inefficiency of EPFs. Therefore, to improve the overall performance of EPFs, greater attention needs to be directed to the efficiency of investment management.

Second, the efficiency of EPFs is certainly also influenced by external factors. The results of the empirical analysis of this study show that differences in size and ownership also determine the performance level of EPFs. In particular, management needs to be reminded that large size EPFs can perform negatively due to diseconomies of scale, or other factors, such as a small domestic capital market or overly tight investment regulations. In addition, this study shows that SOE-sponsored EPFs perform higher in both overall efficiency and investment efficiency. This implies that the privately sponsored EPFs (or other categories) can be modeled on SOE-sponsored EPFs. Specifically, the privately sponsored EPFs may refer to the SOE-sponsored EPFs in terms of technology deployment and improvements in participants’ and governing bodies’ financial and investments knowledge and skills.

Academically, this study broadens the literature on pension fund efficiency both in terms of performance measurement methods and results. In terms of methods, previous efficiency studies within the scope of pension funds have generally used traditional methods, such as the risk-adjusted method (

Hasanudin et al. 2017), ratio analysis (

Sunaryo et al. 2020), or conventional DEA (

Seran et al. 2022). Efficiency studies using the additive network DEA method are still rare. Especially in the Indonesian context—to the best of our knowledge—this is the first study that applies network DEA to measure the performance of the pension funds industry. In terms of results, this study adds to the body of knowledge about the performance of pension funds from the perspective of developing countries such as Indonesia.

This study has some limitations. First, the results of this study indicate diseconomies of scale in EPFs but does not analyze them further to determine the optimal point size. Second, due to data unavailability, our study is less comprehensive in terms of the input and output variables included in the model. By including some considerably important input/output variables, such as the amount of participants’ contribution collected as an input to the first stage, benefits paid to members as a leaving output of the first stage, and total risk as an additional input to the second stage, the present model may give different results. Therefore, future studies can improve the model by including those variables to give a more comprehensive picture of EPFs’ performance.