1. Introduction

Recent studies have provided empirical evidence that Chief Executive Officers (CEOs) with superior education and previous experience in the industry outperform industry outsiders in diversifying mergers and acquisitions, and their specific industry skills are most valuable in bargaining better prices with target shareholders and also in negotiating deals, especially if the quality of the target company is harder to assess (

Custódio and Metzger 2013;

Nawaz 2021). Furthermore, studies have found a positive link between CEOs’ acquisition experience and subsequent acquisition success (

Field and Mkrtchyan 2017). CEOs with financial expertise are also found to be more capable in raising external funds, even when credit conditions are tight (

Custódio and Metzger 2014). In the case of IPO firms, executives’ industry and finance expertise were found to have a strong bearing on investors’ investment decisions (

Gounopoulos and Pham 2018).

What about Special Purpose Acquisition Companies (SPACs) or blank check companies, which do not have any operational activities nor anything to sell with their only assets being funds raised from the Initial Public Offerings (IPOs)? Despite high uncertainty and risk, they became the latest hottest product on Wall Street, quickly spreading to financial markets in other parts of the globe, such as Canada, Germany, South Korea, and the UK (

Kim et al. 2020). While SPACs have been around for some time, the number of SPACs has surged substantially in 2020. Despite tough economic conditions when the equity markets around the world were squeezed with the COVID-19 pandemic, SPACs have succeeded in raising funds at substantial rates as well as in attracting more high-profile investors to invest in such an alternative scheme. This suggests that investors’ decision to invest in a SPAC IPO during the socioeconomic malaise may be driven by recognition of the unique managerial capabilities and confidence in the SPAC’s founder to succeed.

2Drawing on a sample of 905 SPAC IPOs (including both liquidated and completed SPACs), floated in the U.S. for the January 2010 and September 2021 periods,

Gahng et al. (

2021) reported that SPAC IPO investors earned annualized average returns of 15.9% through the date of liquidation or merger completion. The study further shows that merging with a SPAC is significantly more expensive for private operating companies relative to a traditional IPO. A more recent study by

Kiesel et al. (

2022) documents an average short-term announcement return of +7.4% and a one-year abnormal return of −14.1% (−18.0% over two years) for public investors beginning from the merger announcement. These results are drawn from an analysis of 236 successfully merged SPAC IPOs completed during the period January 2012 and June 2021. The study further notes a decline in short-term returns when announcements take longer times from IPO.

As the authors explain in section two, the 2020–2022 period has witnessed an unprecedented increase in SPACs, and most of these SPACs are still looking for a potential target for acquisition. Therefore, the available data on the performance of SPAC IPOs is limited, however, with the maturity date approaching, this data will expand to include the recent SPACs for a more comprehensive analysis. The authors recognize this as a potential area for future research.

While previously cited studies are important, they have failed to consider the intangible aspects related to the SPACs’ founders, which may be the main driving force behind the success in raising funds. Hence, the authors address a lacuna in this stream of literature by exploring the significance of founder’s social capital for the success of SPAC IPOs.

The authors adopt the case study

3 approach to explore and interpret this social phenomenon using Pershing Square Holdings Ltd. (PSH) as the case since it succeeded in launching one of the most successful SPAC IPOs (Pershing Square Tontines Holdings Ltd.) in 2020. As a multidisciplinary concept, social capital has a wide range of definitions and inconsistent operationalizations (

Payne et al. 2011). To minimize speculative reasoning, the authors adopt the social capital theory advanced by

Nahapiet and Ghoshal (

1998) to guide the analysis of how social capital is structured and mobilized. Utilizing publicly available documents and various information from the internet, including social media platforms, the authors explore how the structural, relational, and cognitive social capital of the founder and CEO of PSH, PSTH, and Pershing Square Capital Management (PSCM), Bill Ackman, contributed to the PSTH’s success in raising US

$4 billion on 22 July 2020, the biggest SPAC IPO in the market at the time.

Our analysis reveals how the sponsors’s social capital help in gaining high value for the SPAC IPO. Particularly, the sponsor’s cognitive social capital, which, in this case study, is developed through the ‘Harvard brand’, not only provided the SPAC sponsor an academic edge but also helped build their structural and relational capital through connections and accessibility to influential investors from their academic connections, i.e., Harvard and family business networks. Being recognized as one of the most renowned hedge fund managers on Wall Street as well as being the founder and CEO of a successful investment company, Pershing Square Capital Management, which currently has over US$14 billion assets under its management, plays an important part in Bill Ackman (the sponsor) gaining the trust and confidence of potential investors. Equally, the sponsor’s ability to recruit the best talents with strong social capital to add to his own social capital created synergy for the company’s business model of choosing to only invest in target companies that have a formidable barrier to entry, minimal capital market dependency, and an exceptional management team. The authors’ analysis further reveals that regular media presence further ensures sponsor’s continuous engagement with established and potential networks.

Evidence presented in this study has important implications given the high popularity trends of SPAC IPOs in recent years (

Aliaj and Kasumov 2021;

Gahng et al. 2021) and the new private equity industry’s trend toward deal-by-deal fundraising (

Blankespoor et al. 2022). Thus, insights observed in this study have a strong bearing from investors, especially in the private equity market at the pre-IPO stage and for the market at large, at the time floatation stage. Equally, the authors seek to inform the current SPAC investors on the relevance of the sponsor’s personal traits, not only in raising financial capital at an IPO stage but potentially acquiring a revenue generating business using the raised capital. Furthermore, this analysis adds to the lively debate on which CEO characteristics matter (

Custódio and Metzger 2014). The authors add to this literature stream by recognizing the role of human intellectual capital and social network ties in the success of SPAC IPOs.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. In the next section, the authors present a brief overview on the development and current trend of SPACs. This is followed by a discussion of social capital theory in

Section 3. In

Section 4, the authors present an analysis of the case study. In doing so, the authors also discuss the personal profile of Bill Ackman, CEO of Pershing Square Capital Management and the SPAC sponsor. Finally,

Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Development of SPACs and the Current Trends

Blank check companies or Special Purpose Acquisition Companies (SPACs) were first launched in the 1980s, but they were often associated with fraudulent activities due to their tendency to mislead unsophisticated and inexperienced investors by exaggerating the liquidity and value creation potential of the intended acquisition (

Cumming et al. 2014, p. 199). A new class of SPACs emerged in 2003 following the issuance of “Rule 419 Blank Check Offering Terms” by the U.S. Securities Exchange Commission (SEC), which regulates aspects related to transparency, shareholder protection, and the alignment of interests between shareholders and SPAC sponsors (

Kolb and Tykvova 2016). Rule 419 also makes it obligatory for IPO proceeds to be held in a trust account (

Beatty and Kadiyala 2003).

Kolb and Tykvova (

2016, p. 83) explain the structure and lifecycle of a typical SPAC. According to

Kolb and Tykvova (

2016), he first phase is the formation phase. The “SPAC founder”,

4 also known as the “SPAC sponsor”, pays US

$25,000 as fees for the right to promote a SPAC IPO. They then complete the normal filings associated with going public and since the company has no operational business, the filing process is faster and easier than a typical IPO. The second phase is the promotion phase. Following the private placement, the SPAC sponsor will issue the IPO and then go on a roadshow to find interested investors. Unlike the traditional IPOs, they must bank on their reputation, credibility, and experience in raising the funds necessary for potential acquisition because there are no operations or business activities that allow investors to make any kind of assessment. The proceeds raised from the IPO are deposited into an escrow account where they earn interest until the SPAC sponsor or promoter finds a suitable private company looking to go public through an acquisition, a strategy known as a reverse merger (

Gahng et al. 2021). This is a shortcut process for private firms and start-ups to get listed in the stock market.

The SPAC IPO is usually in the form of public shares, and it is normally equivalent to 20% of the SPAC’s equity (

Cumming et al. 2014). A SPAC sponsor typically offers 3% of the total SPAC funds to obtain warrants that carry the right to buy shares in the company at a predetermined price once the SPAC successfully acquires a target. However, if the SPAC fails to acquire a target company/business within the given timeframe, usually within two years (

Kim et al. 2020), the SPAC funds will be liquidated, and the sponsor will lose the invested funds.

5In the third phase, following the SPAC listing, the SPAC sponsoring manager will start screening for a target, and once an appropriate acquisition target is found, the sponsor performs extensive due diligence, negotiates the structuring of the acquisition, and fulfils all the regulatory requirements to conclude the SPAC acquisition. After a successful acquisition, the SPAC will typically be listed on one of the major stock exchanges. If the SPAC sponsor fails to find a target within the agreed timeframe or if the SPAC shareholders do not approve the suggested target, the SPAC is then liquidated and the proceeds and accrued interest from the trust account will be distributed among the shareholders (

Rodrigues and Stegemoller 2014).

SPACs have grown from being a niche part of the equity market into a popular alternative route for public markets.

Figure 1 presents the trend of SPAC IPOs for the period 2003–2021. There was an upward trend in SPAC IPOs from 2016 onwards, with the biggest surge occurring in 2020. In fact, in 2020 alone, 248 SPACs were floated into the market, fetching record gross proceeds of over US

$83 billion compared to only 59 SPACs, which managed to only raise around US

$13.5 billion in 2019 (

Aliaj and Kasumov 2021). The trend continues in 2021 and as of 31 December 2021, 613 SPACs were floated into the market, fetching record gross proceeds of over

$162.53 billion dollars (

Aliaj and Kasumov 2021). The SPAC market today is dominated by high profile names, such as Bill Ackman, Michael Klein, Chamath Palihapitiya, and Howard Marks, to name a few.

According to

Panton and Adams (

2020), the recent surge in SPACs’ popularity may be attributed to three main factors. The first factor is related to supply and demand. While the number of publicly traded firms has declined dramatically over the past two decades from 8000 to just over 4000, the amount of financial capital flowing into the public markets has simultaneously increased. Since stock exchanges make money by getting firms listed, they have pushed to bring more SPACs into the market.

The second factor is related to the private equity (PE) market, which has witnessed a huge increase in the amount of money invested in the PE ventures (over $2 trillion), as they appeal especially to those actively looking for alternative investment opportunities and see the SPAC model as another attractive investment avenue. The third factor is related to involvement of the SEC in boosting SPACs’ reputation in the investment world by setting a fixed price for each IPO as well as regulating the voting and redemption rights to the benefit of all parties involved.

Similarly, start-ups and private companies would also prefer to go public via SPAC instead of a traditional IPO, not only because of stability in share price and speed of raising funds, but also for the potential strategic partnerships with the sponsors. The following quotation by the CEO of Hims, the Healthcare D2C Start-up that recently announced going public via a SPAC sponsored by Oaktree Capital Management (owned by Howard Marks, who is known for his highly detailed investment memos, which cover everything from cryptocurrency to index investing) expresses the desire for such partnership:

“The authors had always expected and prepped for a traditional IPO, but there are a lot of favorable dynamics in the new group of SPACs. There’s greater speed and certainty of a deal, which helps the team stay focused, and the authors get to partner with an amazing investor like Howard Marks (

https://www.cbinsights.com/research/report/what-is-a-spac/, accessed on 15 October 2021).”

3. Social Capital

Social capital theory, which originates from sociological studies, has now been used in other fields.

Bourdieu (

1986, p. 21), in differentiating social capital from human, economic, and cultural capital, defines it as ‘the aggregate of the actual or potential resources which are linked to possession of a durable network of more or less institutionalized relationships of mutual acquaintance and recognition—or in other words, to membership in a group’. Similarly,

Burt (

1992, p. 9) focuses on social networks and defines social capital as ‘friends, colleagues, and more general contacts through whom you receive opportunities to use your financial and human capital’. Unlike Bordieu and Burt, whose definition of social capital focused on the external perspective,

Coleman (

1988) views social capital from an internal perspective and defines it as a unique kind of resource available to an actor which helps in defining the relationship structure between and among actors.

Nahapiet and Ghoshal (

1998) develop a broader concept of social capital to include both the network and the assets that may be obtained through it, thus covering both the internal and external perspectives. Their definition of social capital entails three dimensions, each encompassing several facets: structural, relational, and cognitive. Their structural social capital dimension refers to the overall pattern of connections between the individuals embedded in social networks whereby they can benefit through their network ties, including getting jobs, acquiring information, and obtaining resources (

Tsai and Ghoshal 1998). Their relational social capital describes the interpersonal relationships developed through individuals’ interactions (

Granovetter 1992) that affect or control individuals’ behaviours when interacting with others. Through such interactions, trust, obligations, norms, and identity are formed and individuals can leverage from such relational embeddedness (

Tsai and Ghoshal 1998). More recent research on relational social capital has extended the facets of this dimension to include reciprocity (

Chiu et al. 2006), commitment (

Wasko and Faraj 2005), and communication (

Requena 2003).

6 Cognitive social capital refers to the resources that provide shared interpretations, representations, and meaning in a group and facilitates a mutual understanding of the common goals and norms in the society (

Tsai and Ghoshal 1998). At the individual level, cognitive social capital affects personal knowledge contributions to the network, while at the organizational level, it contributes to the creation of intellectual capital (

Nahapiet and Ghoshal 1998).

Since SPACs do not have any business activities and their only assets are the funds raised, SPAC sponsors need to exploit their various social capital to receive higher valuation than traditional IPOs. In the following section, the authors critically analyse a SPAC IPO, PSTH, led by one of the seasoned hedge fund managers on Wall Street and billionaire, Bill Ackman, as a case study.

4. The Case Study

Pershing Square Holdings Ltd. is an investment holding company incorporated under the laws of the Bailiwick of Guernsey in 2012. It is structured as a close-ended fund principally engaged in the business of acquiring and holding significant positions in a concentrated number of large capitalization companies with the objective of maximizing the long-term compound annual rate of growth in intrinsic value per share (

Pershing Square Holdings 2021, p. 1). The company’s portfolio is typically allocated from 8 to 12 core holdings comprising liquid, listed, large capitalization North American companies. Public shares of PSH commenced trading in Euronext Amsterdam in 2014 and it commenced trading on the Premium Segment of the Main market of the London Stock Exchange in 2017.

PSH appoints Pershing Square Capital Management (PSCM) as its investment manager, who is responsible for the investment of PSH’s assets and liabilities in accordance to the company’s investment policy and subjected to the overall supervision of its board. PSH regularly holds investor meetings where the investment manager will present updates on the portfolio. The board is comprised of seven members, six of whom are independent. The chair of the board is a female, and another female joined the board in 2022. Looking at the credentials of board members, they are all educated in top business schools and have substantial working experience in the field of finance and investment. The company has an audit and risk committee, nomination and management engagement committee, and remuneration committee.

As a closed-fund investment company, its performance is highly dependent on the investment manager. Having an active and engaged investor working well with the portfolio of companies is important in creating enduring, long-term share value. The investment manager must also possess good strategic thinking in minimizing risk. In short, ability of the investment manager to structure and mobilize their social capital is vital for the success and sustainability of the business. In the following sections, the authors will focus on Bill Ackman, the investment manager for PSH and the CEO of PSCM.

4.1. Bill Ackman—CEO of Pershing Square Capital Management

William (Bill) Albert Ackman was born on 11 May 1966 in New York, to an affluent family. His father, Lawrence Ackman, was the chairman of Ackman Brothers & Singer Inc., a commercial real estate mortgage brokerage in New York. Following in the footsteps of his father, who holds an MBA in finance from Harvard Business School and a BA in Economics from Brown University, Bill Ackman graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree magna cum laude from Harvard College in 1988 and an MBA from Harvard Business School in 1992. The opportunity to study at Harvard and being among the most intelligent and influential group of people from all over the world not only helped in nurturing Ackman’s intellectual acumen but also in his professional life. Hence, growing up in an affluent business family and graduating from Harvard helped in shaping Ackman’s cognitive social capital, especially his personal and social emergence, as well as development of his ‘entrepreneurial identity’ later.

After graduating from Harvard, Ackman and his Harvard classmate, David P. Berkowitz (a seasoned hedge fund manager who currently serves as the Chief Investment Officer at KFO, New York, NY, USA) set up Gotham Partners, an investment company, in 1992, with an initial capital of

$3 million. They managed to quickly grow the fund to

$300 million by attracting high-net-worth individuals and leading Wall Street financial elites, such as Seth Klarman, Michael Steinhardt, and Whitney Tilson, among others (

Richard 2011). Accessibility to those social elites was possible by exploiting the structural and relational social capital that both he and his friend had gained from their Harvard networks, as well as family business networks.

In 2004, Ackman founded Pershing Square Capital Management (PSCM), a hedge fund company with an initial

$54 million assets under its management, which increased to

$14 billion in 2020. The board of directors of PSCM all possess strong personal and professional profiles. Four out of six directors graduated from elite academic institutions such as Cambridge University, Harvard Business School, London School of Economics, and Oxford University. All board members have international working experience and have had exposure to the international markets in Asia, Australia, Europe, and America. Thus, besides bringing diversified knowledge, skills, and industry-specific managerial experience to the firm, they also helped to expand the company’s structural and relational social capital gained while working in various industries and sectors.

7A closer look at PSCM’s governance structure indicates compliance to good governance. The board consists of six board members, including two female independent non-executive directors and four male directors, out of which three are independent non-executive directors, and one is an executive director. The board is led by a female independent non-executive director as chairman and Ackman as the CEO. Thus, having the right people as a check and balance mechanism is vital for the success of the organization, and Ackman managed to address this by using his cognitive social capital to assemble a team of talents working with him. The similarities in their relational social capital allow them to interact and communicate using the same ‘business language’ and share the same understanding, thus creating a high level of synergies between the board and management.

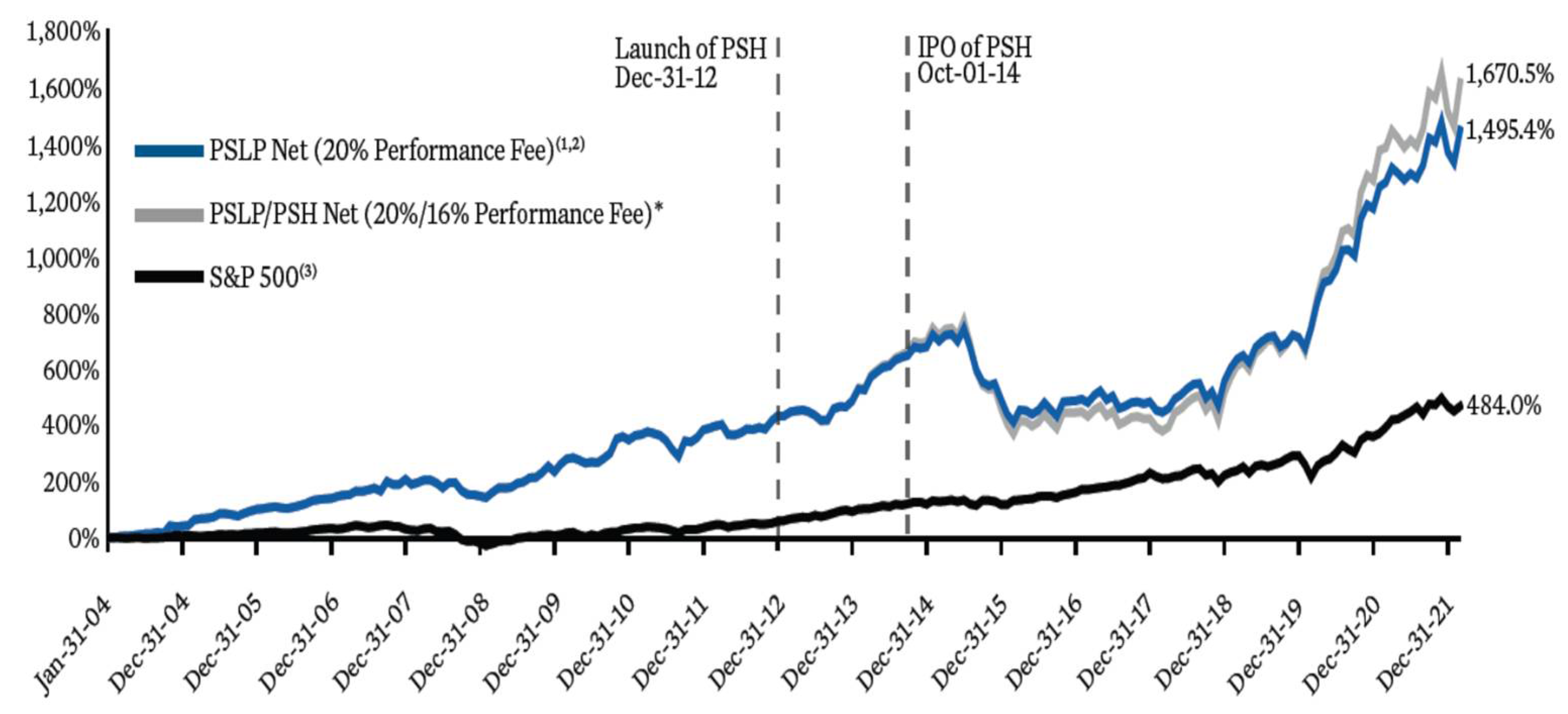

Following the incorporation of PSH in 2012, PSCM has been appointed as the investment manager in managing its assets and liabilities. The annual report of PSH shows Bill Ackman signing the investment manager report. In other words, it is the investment team in PSCM that managed the portfolio and contributed to its impressive investment performance based on Net Asset Value (NAV) as shown in

Table 1.

Figure 2 illustrates the average performance trends in Pershing Square Holdings versus the S&P500. As can be seen, PSH had outperformed the S&P 500 companies in most of the years by offering higher net returns. The 18-year average net return for PSH is 17.1% compared to only a 10.2% net return for S&P 500 companies. In fact, when the markets shrank due the pandemic in 2020, PSH was still able to provide its investors a return of 70.20%, breaking its previous record of 58.10% in 2019.

Such an unprecedented return is largely attributed to Ackman’s sharp investment strategies and understanding of the market that allowed him to bounce back after four years of negative returns (2015–2018). However, its performance plummeted in 2021 to 26.9% but still not too far behind the S&P500’s net return of 28.7%. This was partly attributed to the exit route taken for some of its portfolio due to market volatility, especially a year after the onset of the pandemic.

While Ackman’s achievements are generally impressive, he also had his share of failures that caused him large losses, such as with Valeant Pharmaceuticals International Inc., Laval, QC, Canada (2017) and Herbalife Ltd., Los Angeles, CA, USA (2018). He was derided for his confidence and tenacity by his critics for his all-or-nothing approach that led to some of the greatest busts in the investing world. However, he always managed to bounce back and impressed investors with his unprecedented performance in 2019 and 2020.

According to a Bloomberg report (

Maloney and Parmar 2021), Bill Ackman is, today, amongst the top 10 highest-earning hedge managers in the U.S. The earnings of his hedge fund company, PSCM, reached over

$1.3 billion during the year with fund returning 70%, the second highest return by a hedge fund in 2020.

4.2. Bill Ackman and Media Presence

Media presence, especially social media, provides a powerful tool for socializing social capital and reputation building. Bill Ackman has exploited the use of media to enhance his networks and credibility as a hedge fund manager and entrepreneur from the early stage of his career.

However, he first gained prominence on Wall Street when he warned the market before the financial crisis of 2008 that the

$2.5 trillion bond insurance business was a catastrophe waiting to happen (for a detailed analysis, see (

Gotham Partners Management Co. 2002)). His good knowledge of market instruments, industry experience, and expertise enabled him to sense that the majority of the triple-A rated bonds were not going to sustain the crisis and he bought credit default swaps against those bonds. The smart investment strategy generated

$1 billion more for his investors when the bond insurers kicked off the collapse of the credit markets (for more details, see (

Richard 2011)). This demonstrates Ackman’s ability to use his cognitive social capital to build his reputation and credibility. Regularly expressing his views in the Wall Street Journal and taking strategic actions on what he believes in helped him expand his networks of hedge fund managers, potential investors, and other stakeholders.

He again demonstrated his sharp investment strategy that gained him further publicity during the COVID-19 pandemic. At the start of the pandemic, Ackman focused his attention on credit markets, as he believed that the markets would suffer steep losses due to the pandemic (

Fraidin 2021). He spent

$27 million on investment-grade and high-yield bond indices to protect his investors’ interest, but he gained

$2.6 billion in less than one month as the markets crashed (also see

Gara 2020). He acted fast by reinvesting

$1.5 billion in rebuilding a position in Starbucks, and adding companies like Agilent, Berkshire Hathaway, Hilton, Lowe’s, and restaurant brands, as well as the parent company of Burger King and Popeye’s to his portfolio, as he expects these sectors to experience high growth when the economy recovers from the pandemic (

Driebusch 2020;

Fraidin 2021). Ackman received overwhelming media attention and received praises for his investment strategy during the COVID-19 Pandemic.

8Since 2017, PSH began to actively participate in social media, especially on Twitter under two accounts: @BillAckman and @PershingSqFdn. Both accounts have about 435,100 followers. Until April 2022, there were 1200 tweets from Ackman and his company with an average of 20 tweets per month. Through these two accounts, plus the official company website (

https://pershingsquareholdings.com/company-documents/, accessed on 26 March 2021), Ackman and his company managed to structure its social capital through its easy-going approach in connecting with individuals embedded in social networks to convey particular information and obtain feedback on everyday matters. He managed to capitalize on his relational and cognitive social capital through interactive tweeting on various contemporary issues that appeal and are of concern to many, such as the value of the Rouble against the USD, the effect of the war on Russian bond and money markets, U.S. economic growth and inflation, including support for environmental and sustainable businesses and discussion on funding methods for medical research and global healthcare. Such efforts extend Tontines leverage within their business environment. The profile message of Pershing Square reveals their cognitive social capital:

“We support exceptional leaders and innovative organizations that tackle important social issues and deliver scalable and sustainable impact across the globe.”

The Pershing Twitter accounts engage in representing the company’s business mission and offer information to correct misunderstandings on particular investments. They use the platform to highlight their achievement for creating the largest social care network, with over 470k program locations and 1295 vetted listings for people in need in every ZIP code in the U.S. to facilitate a mutual understanding of the common goals and norms among their networks.

Hence, it is not surprising that Ackman managed to garner substantial attention from academic circles and has spoken to audiences at the Saïd and Harvard Business School (

Fraidin 2021). A recent study by Oxford University dubbed Bill Ackman as the activist investor (

Rojas 2017), and earlier academic work recognized his role in criticizing Wall Street (

Richard 2011).

From the preceding discussions in this and the prior section, the authors can infer that Bill Ackman has successfully exploited the various forms of social capital to create a reputation for his company as well as established himself as a respectable hedge-fund manager in creating value for the shareholders. Gaining such credibility status helped him in his next venture as a SPAC sponsor.

4.3. Bill Ackman—Sponsor of SPAC IPO

On 22 June 2020, Bill Ackman filed with The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), as per Form S-1 registration statement under The Securities Act of 1933, to sponsor a SPAC IPO known as Pershing Square Tontine Holdings Ltd. (PSTH).

9 The SPAC went public in July, offering 200 million units at US

$20 a share at floatation, which is double the traditional SPAC-IPO value of US

$10 per share. The vehicle was initially planned to raise US

$3 billion with a listing on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) and close to a US

$500 million green shoe option, which permits for additional shares to be issued if the demand is higher than expected (for further details, see

Aliaj 2020). The IPO was well perceived by the market, resulting in a record US

$4 billion being raised, the most proceeds ever raised via a SPAC IPO at that time. In September 2020, Tontine was listed for trading on the New York Stock Exchange. The share closed at US

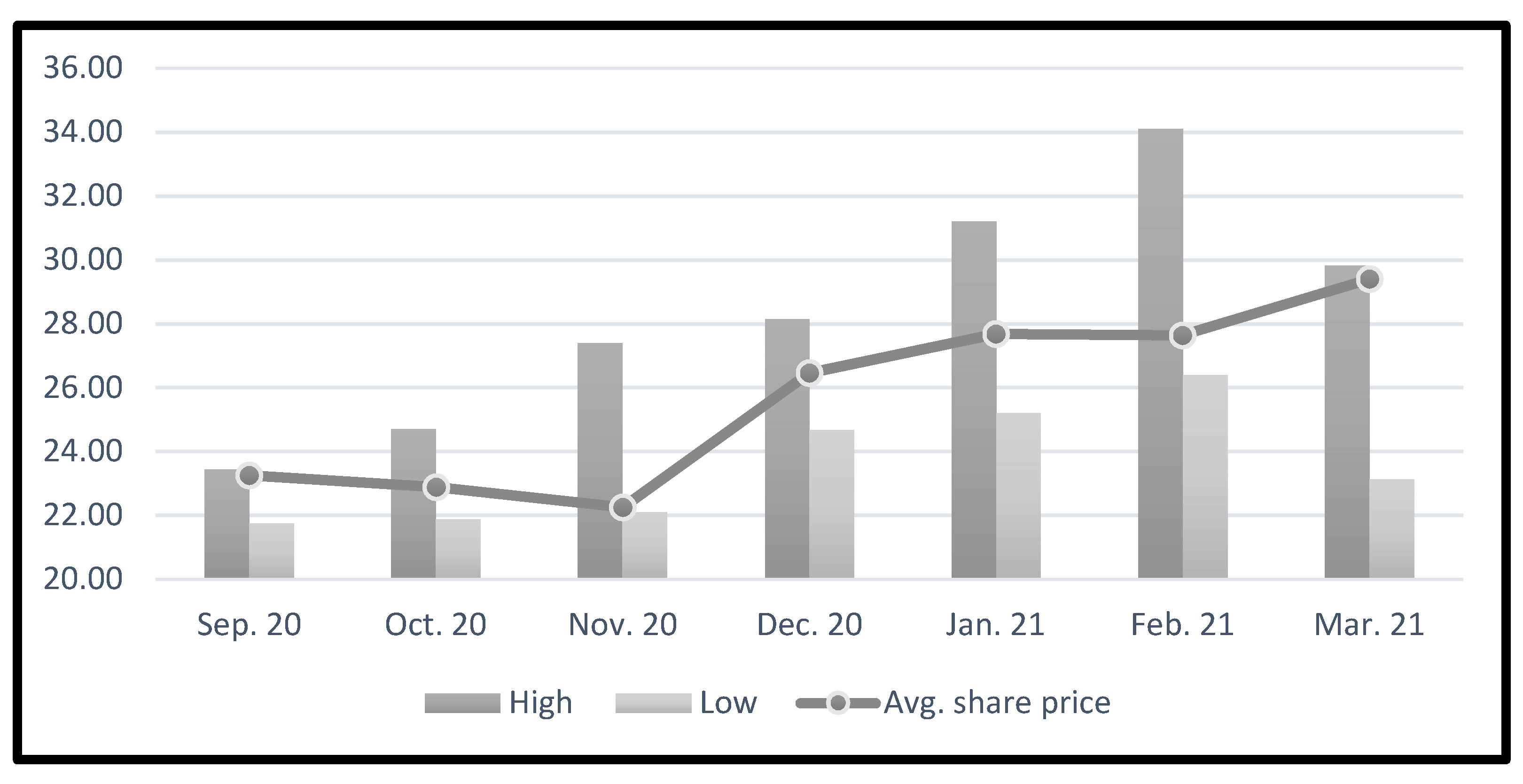

$21.60 on the first trading day and its share value increased almost 50% since being listed.

Figure 3 illustrates the average monthly share price of Tontine along with its lowest and highest prices since its listing. The outstanding performance of Tontine is not surprising as its sponsor, Bill Ackman, offered a product that sets it apart from the typical SPAC in the market and had chosen the right time to launch its IPO. An analysis of Tontine’s prospectus revealed Ackman’s ingenuity when structuring the product by considering the key issues of concerns to potential investors, such as the SPAC-sponsors’ equity share, treatment of warrants, and cash-out opportunities that often lead to adverse selection and moral hazard.

Using his cognitive social capital, Ackman relinquished the traditional 20–25% equity ownership that SPAC founders typically maintain at the pre-IPO price, which is relatively lower than the post-IPO price. By doing so, he sent a strong signal to potential investors that he is unlike his other SPAC sponsor counterparts who focused on pre-IPO equity stake. Since the typical SPAC sponsor retains 25% of the equity, this means only 75% equity is actually available to the market. However, in the case of Tontine, by opting not to retain 25% equity stake at a predetermined price makes it more attractive for the investors as they see full (100%) equity value. Furthermore, to maintain its equity stakes, the Tontine sponsor opted to buy warrants at their fair value, which are not transferrable or exercisable until three years after the SPAC concludes with a deal

10 while warrants by most of the other sponsors are exercisable 30 days after a SPAC deal (

The Economist 2021). In addition, the warrants held by the Tontine sponsor represents just under 6% equity stake and are only exercisable at a 20% premium, which helped to curb the cash-out opportunities often practiced by other SPAC sponsors in the post-IPO phase. By structuring such features in the Tontine SPAC, it boosted the confidence of potential investors, as the sponsor indicates firm commitment to remain involved with their equity intact for three years.

While the Tontine SPAC structure ensured firm commitment from the sponsor, it also demand the same commitment from the investors, indicating a mutual long-term commitment towards the potential IPO firm. In a typical SPAC, investors keep all their warrants when they redeem their shares (

Klausner and Ohlrogge 2020) and this may lead to arbitrage opportunities for investors, as they could redeem their shares and recoup their original investment while still holding onto their warrants. In a departure from the traditional SPAC, the Tontine SPAC offered non-detachable warrants. Under this covenant, investors are still afforded the arbitrage opportunities but on a condition that the sale of shares must include two-thirds of the warrants. This makes such transactions relatively less attractive, as they discourage cash-out opportunities. However, such constraints mitigate the financial capital risk that a sponsor may face if too many shareholders opt for cash-out opportunities, leaving the SPAC with lesser financial capital available to acquire a target business or assets (

Henderson and Platt 2020;

Klausner and Ohlrogge 2020).

A comparative analysis revealed huge variations between a traditional SPAC and the Tontine SPAC. The latter structure is deemed less dilutive to investors/shareholders compared to a traditional founder share structure. Hence, it is not surprising that the Tontine SPAC was so appealing to the investors. In fact, in a recent interview, Ackman revealed that the demand for Tontine SPAC already reached

$12 billion on the second day of his roadshow (see

Fraidin 2021). Such an overwhelming response during the roadshow demonstrates investors’ confidence in him. He had built his structural and relational social capital over the years and gained attention not only by making bold statements regarding the financial market but also providing exceptional returns to his investors. His entrance as a SPAC sponsor at a time when the market was squeezed was a smart move because high-net-worth individual investors and major institutional investors were looking for other investment avenues during a disruptive event, such as the pandemic. Since companies care about who their shareholders are, the over-subscription and demand for PSTH’s SPAC IPO provided Ackman with the opportunity to select the most important sovereign wealth funds, community pension plans, state plans, and 50 billionaire family offices from Saudi Arabia, Switzerland, U.S., and all over the world, as the shareholder base for his company.

While Ackman has been successful in raising the funds, he has yet to find the target company in 2021. He attempted to create value by actively looking to buy “mature unicorn” valued at more than USD

$1 billion (

Aliaj 2020). Soon after its IPO in September 2020, Ackman approached Airbnb, but the company spurned to go public via a SPAC merger and instead preferred a traditional IPO. His earlier attempt to acquire a mature unicorn signals his determination to deliver on its promise to the shareholders who are wagering on Ackman’s track record to produce a superior merger choice.

5. Conclusions

This study addressed the significance of social capital for the success of SPAC IPOs. Unlike the typical IPOs where potential investors can make an assessment based on a company’s past performance, SPAC IPOs are more risky and highly speculative, as they heavily rely on the credibility of its sponsor. Furthermore, value creation through a SPAC IPO is typically a long-term process, as it takes time to put all the acquired resources to the best use to create value for the stake(share)holders (

Teece 2010). Hence, a firm commitment from the SPAC sponsor is required to ensure a timely transformation of organizational resources into tangible outcomes (

Liu et al. 2017). Sponsors with specialist industry knowledge have a better ability to plan for long-term value creation by mitigating short-term risks and capitalizing on opportunities that will maximize company value in the longer run (

Vomberg et al. 2015).

Analysis of the case study reveals that the sponsor’s social capital helped in gaining high value for the SPAC IPO. The sponsor’s cognitive social capital is developed through the ‘Harvard brand’, which not only provided him an edge in academia but also in building his structural and relational capital through connections and accessibility to influential investors from his Harvard days and family business networks. Being recognized as one of the most renowned hedge fund managers on Wall Street as well as being the founder and CEO of a successful investment company, Pershing Square Capital Management, which currently has over US$14 billion assets under its management, play an important part in gaining the trust and confidence of potential investors. Equally, the sponsor’s ability to recruit the best talents with strong social capital to add to his own social capital created synergy for the company’s business model of choosing to only invest in target companies that have a formidable barrier to entry, minimal capital market dependency, and an exceptional management team. Regular media presence further ensures continuous engagement with established and potential networks.

This study has its limitations. First, the authors focused on only one case study; hence, future research may consider multiple cases in analysing the success and survival likelihood of SPAC IPOs. Second, the authors used social capital as the theoretical framework in analysing the success of a SPAC IPO and future research may use other theories to study the phenomenon.

While our study makes several contributions to extant knowledge with the realized limitations, like any study, it opens new avenues for research. Future research offers the opportunity to explore the relationship between sponsor’s personal traits (including but not limited to social network ties and personal human capital) and success of SPAC IPOs, in greater depth. The authors particularly encourage future researchers to: (i) replicate our study in analysing the effects of the sponsor’s profile on successful completion of acquisition and the quality of the acquired asset/business as well as the predicted future returns, i.e., value for the investors/shareholders; (ii) consider the overall effects of the governance structure of a SPAC IPO relative to an ordinary IPO in raising capital for a successful income generating asset acquisition; (iii) study the determinants of SPAC IPOs relative to general IPO to tease out the ethical issues such as short-termism, which is inherent in the former; and (iv) perform a comparative analysis considering competing SPAC IPOs to identify (if any) performance differentials that could be attributed to the SPAC sponsors: seasoned mangers, such as Bill Ackman, versus unknown SPAC sponsors.