Staff and Users’ Experiences of Pharmacy-Based Sexual and Reproductive Health Services: A Qualitative Interview Study from the UK

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Umbrella and Their Pharmacy Services

1.2. Aim of This Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Participants

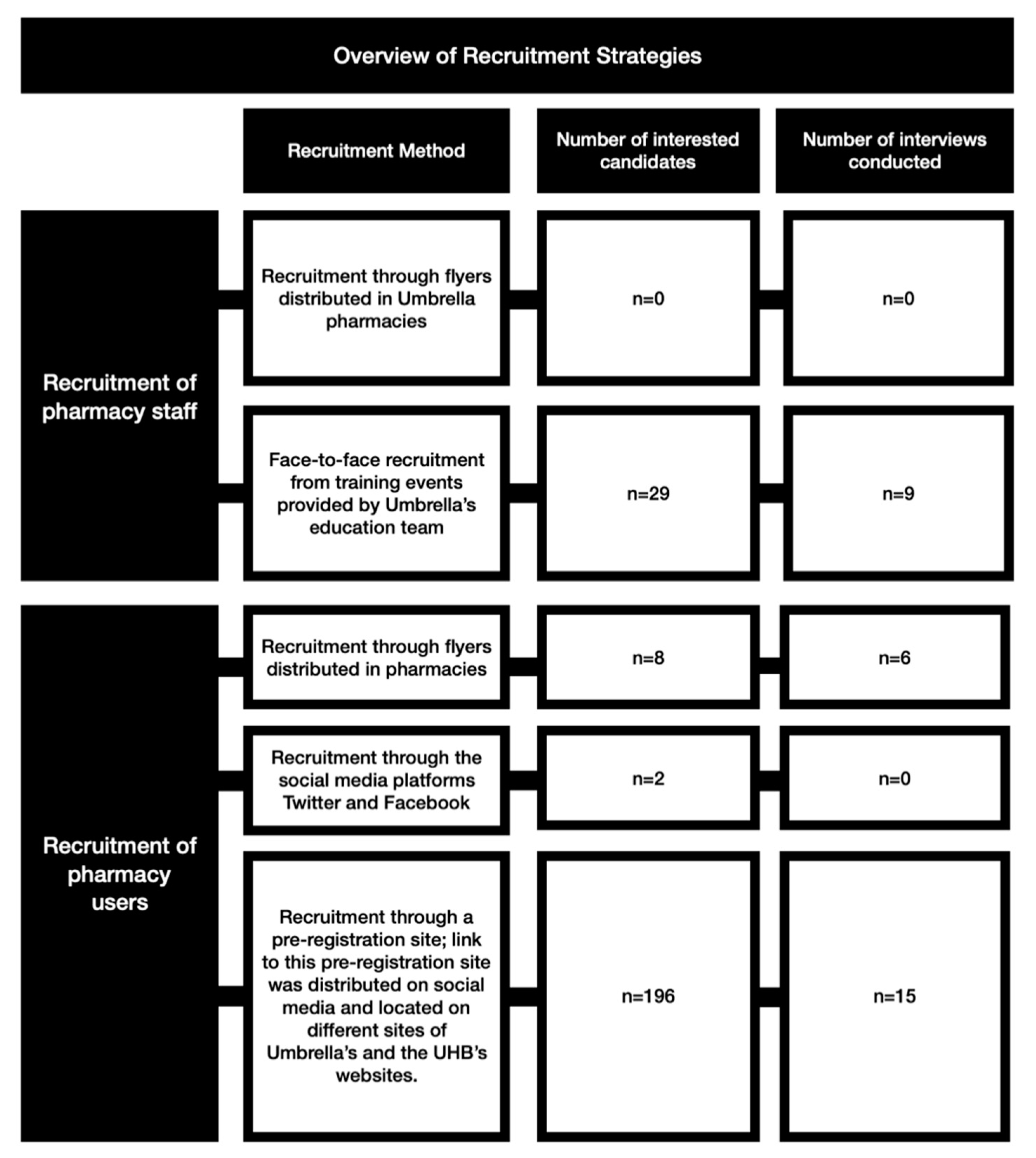

2.2. Recruitment

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

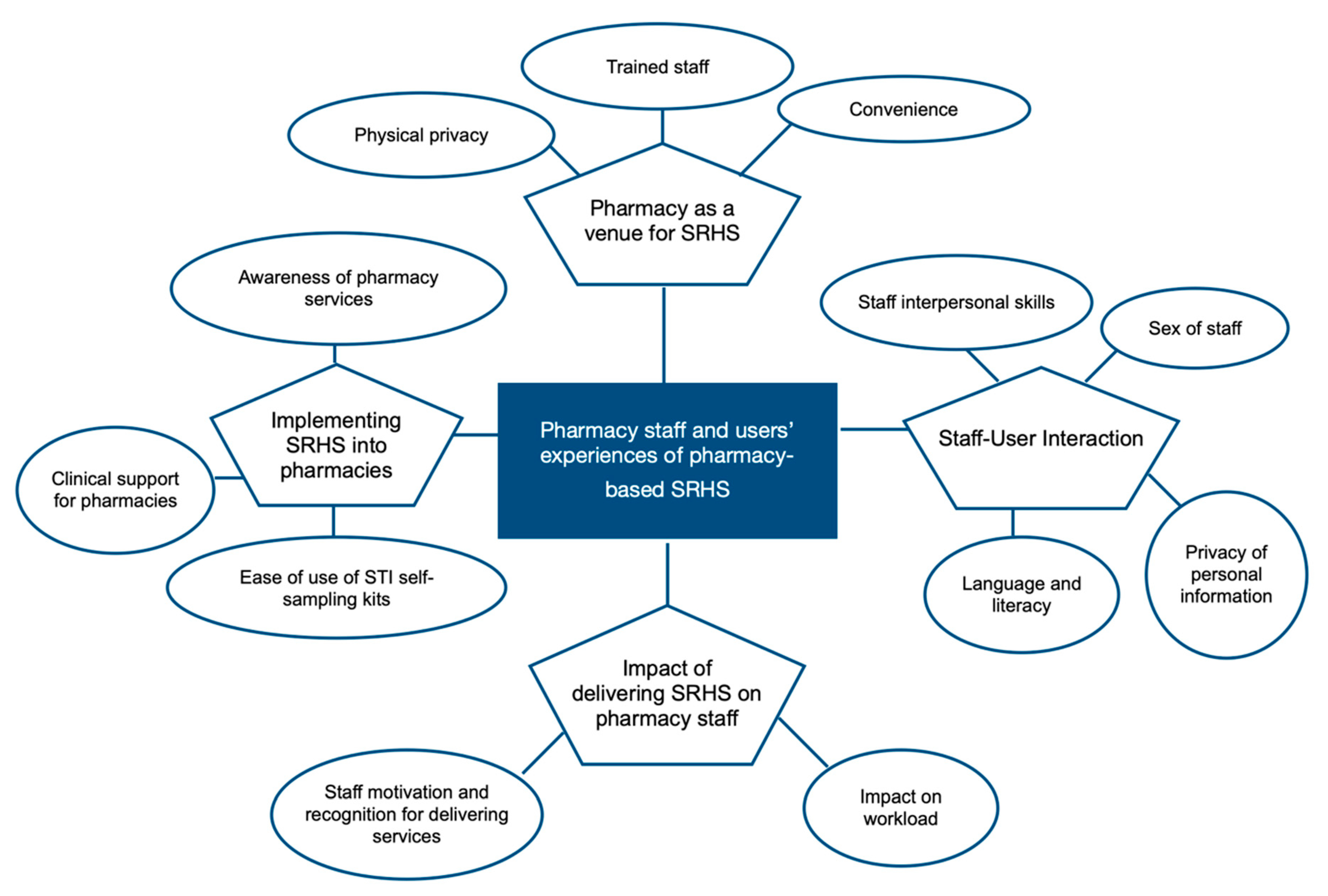

3. Results

3.1. Theme 1: Pharmacy as a Venue for SRHS

3.1.1. Physical Privacy

“There is definitely a feeling of judgement when you’ve got people that are stood behind you in the queue and whatnot and you’re asking for the morning after pill”(pharmacy user, female, age group: 25–29).

“So that’s why I didn’t choose to go in there, because it’s more of a judgement element to be honest, because, because I’m waiting for so long for the coil to, you know, get that appointment ... readily available ... I had to go into that pharmacy three weeks for the same thing (emergency contraception). And that’s not because I’m not, being careless, I’m using things, they’re just not working”(pharmacy user, female, age group: 25–29, ID number: 1082).

“Sometimes when I go into my other pharmacy I do have to wait until people have gone out, ‘cause you don’t necessarily wanna be discussing that in front of other people, do you know what I mean? It’s quite sensitive”(pharmacy user, female, age group 25–29).

3.1.2. Convenience

“’Cause I get, I live down the road to that pharmacy ... so it’s very convenient of me to go up there”(pharmacy user, female, age group: 25–29).

“I went back to the same pharmacy and saw a female pharmacist, because both times it was just, just really straight forward, you didn’t need an appointment, was seen really, really quickly, and the staff were nice, and it was just way more, I suppose convenient”(pharmacy users, female, age group: 18–24).

3.1.3. Trained Staff

“I was like, ‘I’m really sorry, but we haven’t got a pharmacist who can do that service for you’. And she got quite upset. You know, you know, she, she was, like, quite teary. And I’m like, you know, ‘If there was something I could do for you, I would’. But she was ... I think she was like, you know, she just felt she needed it there and then”(pharmacy healthcare assistant, female, age group: 30–39).

“So it just, it’s frustrating we have to turn people away because we haven’t got the right pharmacist in”(pharmacy healthcare assistant, female, age group: 30–39).

3.2. Theme 2: Staff-User Interaction

3.2.1. Sex of Staff

“I dunno, I don’t think I’d be comfortable. If there wasn’t a lady working there I probably wouldn’t go to that place”(pharmacy user, female, age group 25–29).

“There’s a, a lot of Healthcare Assistants there. So they can chaperone with the pharmacist. If they’re happy to go with the pharmacist then they can be chaperoned”(pharmacy healthcare assistant, male, age group, 40–49).

“’Cause I’m not attracted to females, if that makes sense? So it’s like, a bit weird saying it to the sex I’m attracted to, if that makes sense?”(pharmacy user, male, age group, 18–24).

3.2.2. Staff Interpersonal Skills

“I had an infection and then I’d, I’d had intercourse again and then there was a, there was a slip-up with the condom and then I had to go back. And he’s, and then, at the end of him seeing me, he said, ‘I don’t want to see you back here again’. And that, that was a few years ago, but it always has stuck with me ... because that was really upsetting”(pharmacy user, female, age group: 18–24).

“I think we could have done with a little bit more training and probably a bit more roleplaying. And just to, yeah, I think they could have done with a little bit more training, just so that you are more confident in providing every service”(pharmacist, female, age group: <30).

3.2.3. Privacy of Personal Information

“I just felt uncomfortable to be honest ... that’s just me personally. I like to be a private person”(pharmacy user, female, age group: 25–29).

“I’ve actually had patients who won’t go for the Umbrella service, just because of that, and they’d ... prefer to buy it I’ve actually had customers, not many, but there are a few customers that, even after we reassure them that all this information is confidential, just don’t like the idea of giving their names and date of births”(pharmacist, male, age group <30).

“If it was like, the clinic could share the information with the pharmacy it felt like it wouldn’t be necessary, if that makes sense? You know, like, the database you keep all the information on? Like, if the pharmacy had access to that as well, it would just your name, date of birth and address, if that makes sense? It would be less, well, anxious…”(pharmacy user, male, age group: 18–24).

3.2.4. Language and Literacy

“There can sometimes be barriers, for example language barriers, if I cannot understand what somebody’s saying, I cannot actually provide a service…I have had a few incidents of that”(pharmacist, female, age group: <30).

“Cause sometimes when they’re a bit, have a bit of broken English it’s a bit harder, and that’s when I maybe refer them to (name of sexual health clinic), or something like that. But I try and use Google Translate as much as I can”(pharmacist, female, age group 30–39).

3.3. Theme 3: Implementing SRHS into Pharmacies

3.3.1. Awareness of Pharmacy Services

“And so then I, I had to, to pay that charge and then I got the emergency contraception from her. They do, they’ve got the Umbrella service, they’ve even got the ... ‘cause I was, ‘cause I was quite shocked myself ... because it does say, online it does say that it’s free ... and they’ve even got the posters, they’ve even got the sticker and they’re part of Umbrella. And then she said there’s a 20-something pound charge”(pharmacy user, female, age group: 25–29).

“Some of the pharmacies that are listed on the website, it’s quite dated, so I gave a few a call and they said they no longer supply that, the Umbrella services, but those websites are still ... those pharmacies are still on the website”(pharmacy user, female, age group 18–24).

3.3.2. Clinic Support for Pharmacies

“And, especially on weekends, it can be really, really difficult to get through as well, and especially when you’re not sure what to do in this situation, you need some guidance and the customer’s waiting as well, it can be really, really frustrating”(pharmacist, male, age group: <30).

“So then I’ve gotta go on the computer and try and get them an appointment, and it’s so difficult to ... find them an appointment, to the point where I’ll be weeks away. So that’s another difficulty I face as well, just trying to get them an appointment at one of the Umbrella clinics”(pharmacist, male, age group: <30).

3.3.3. Ease of Use of STI Self-Sampling Kits

“There’s text in it…so with me I confuse which is which, because I don’t understand what I’m doing. And I don’t know which one I’m doing where, and what I’m doing which, though. If they specified that a little bit more better, then I might be able to continue using that service”(pharmacy users, transgender woman, age group: 25–29).

“So I think they don’t want to take that on themselves, they want someone else to do that for them. Which I think a pharmacist is ideally placed to do so”(pharmacist, female, age group: <30).

3.4. Theme 4: Impact of Delivering SRHS on Pharmacy Staff

3.4.1. Impact on Workload

“And so if it could speed up the process of having them pre-registered on the system then that would cut the consultation down in half. And then I could spend longer then actually, like I said, identifying maybe the patient’s unknown needs rather than just the immediate concern”(pharmacist, male, age group: 30–39).

“When the pharmacist was in ... we would just say, ‘Oh’, you know, ‘we’ve done this service. Can we put it on PharmOutcomes?’ The pharmacist would be, ‘Yes’, you know. ‘Yeah, that’s fine. Just go in and put it on’”(pharmacy healthcare assistant, female, age group: 30–39).

“Well I think it would be great to, sort of, have a place where certain bookings were made, maybe, so it could be a more controlled process and it wasn’t just that people are coming up on the day and saying that ‘We need to have this service’”(pharmacist, female, age group: <30).

“But we’re not staffed to a great level. This is why ... somebody’s always asked me, ‘Why aren’t you a Level, Tier 2 pharmacy?’ and I tell them, ‘It’s because I, I couldn’t just, I, I, I can’t, I couldn’t do that service in my pharmacy. It’ll take too much, there’s too much time pressure and staffing pressures on, on my, on my staff that I wouldn’t be able to run a Tier 2 service’”(pharmacist, male, age group: 30–39).

3.4.2. Staff Motivation and Recognition for Delivering Services

“I guess for me, personally, in offering the Umbrella services it does mean that you’ll be more employable. So say if I went, so when I’m an actual pharmacist, if I’m locum-ing at, like, different pharmacies I guess the fact that you offer them services does, kind of, make you more employable to various pharmacies if you are trained in a number of services”(pharmacy healthcare assistant, female, age group: <30).

“I think the best thing about delivering sexual health services is being able to be in the position to help somebody that is not happy about what’s happened or maybe gets in an accident and they, they’re quite worried, they’re quite anxious, they don’t know how to feel”(pharmacist, female, age group: <30).

“Patients and customers don’t see the pharmacy team as professionals, as they would the pharmacist. So they’ll trust more what the pharmacist is saying than the pharmacy advisor”(pharmacy healthcare assistant, female, age group: 30–39).

“Because we’ve never been asked for feedback. I mean, we get mystery shopped. But we don’t really get asked, like, you know, what else could we possibly do to improve the services, or, you know, what do you think. We don’t really get asked that, to be honest”(pharmacy healthcare assistant, female, age group: 30–39).

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Example Questions and Prompts Used in Semi-structured Interviews with Pharmacy Staff and Pharmacy Users |

|---|

| Pharmacy User Interview |

| Can you tell me why you decided to go to the pharmacy to get (NAME OF THE SERVICE)? Prompts:

|

| Can you tell me about your experience of getting an Umbrella service at a pharmacy? Prompts:

|

| Pharmacy Staff Interview |

| Can you tell me about your experience delivering Umbrella’s services? Prompts:

|

| What impact does the delivery of Umbrella’s services have on you? Prompts:

|

References

- Rowley, J.; Hoorn, S.V.; Korenromp, E.; Low, N.; Unemo, M.; Abu-Raddad, L.J.; Chico, R.M.; Smolak, A.; Newman, L.; Gottlieb, S.; et al. Chlamydia, gonorrhoea, trichomoniasis and syphilis: Global prevalence and incidence estimates, 2016. Bull. World Health Organ. 2019, 97, 548–562P. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stulpin, C.; Marrazzo, J.M. WHO: 1 million new urogenital STIs acquired each day worldwide. Infect. Dis. Child. 2019, 32, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Bearak, J.; Popinchalk, A.; Alkema, L.; Sedgh, G. Global, regional, and subregional trends in unintended pregnancy and its outcomes from 1990 to 2014: Estimates from a Bayesian hierarchical model. Lancet Glob. Health 2018, 6, e380–e389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda, K.; Coleman, L.; Sherriff, N.; Cocking, C.; Zeeman, L.; Cunningham, E. Listening for commissioning: A participatory study exploring young people’s experiences, views and preferences of school-based sexual health and school nursing. J. Clin. Nurs. 2017, 27, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Public Health England. Sexually Transmitted Infections and Screening for Chlamydia in England; Health Protection Report Volume 12 Number 20; Public Health England: London, UK, 2018.

- Office of National Statistics. Conceptions in England and Wales. 2018. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/conceptionandfertilityrates/bulletins/conceptionstatistics/2014 (accessed on 26 October 2020).

- Walker, I.; Leigh-Hunt, N.; Lee, A. Redesign and commissioning of sexual health services in England—A qualitative study. Public Health 2016, 139, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashby, J.; Ahmed, N.; Goldmeier, D. Sexual difficulties service provision within sexual health services in the UK: A casualty of postcode lottery and commissioning? Sex. Transm. Infect. 2019, 95, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hind, J. Commissioning Sexual Health Services and Interventions: Best Practice Guidance for Local Authorities; Department of Health: London, UK, 2013.

- NHS Digital. General Pharmaceutical Services in England 2008/09—Key Facts. Available online: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/general-pharmaceutical-services/in-2008-09---2018-19-ns (accessed on 26 October 2020).

- Public Health England. Sexual Health, Reproductive Health and HIV: A Review of Commissioning; Public Health England: London, UK, 2017; pp. 1–117. Available online: www.gov.uk/phe%0Awww.gov.uk/phe%0Awww.gov.uk/phe (accessed on 26 October 2020).

- Jewell, S.; Campbell, K.; Jaffer, K. Umbrella: An innovative integrated sexual health service in Birmingham, UK. J. Fam. Plan. Reprod. Health Care 2017, 43, 229–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gauly, J.; Ross, J.; Hall, I.; Soda, I.; Atherton, H. Pharmacy-based sexual health services: A systematic review of experiences and attitudes of pharmacy users and pharmacy staff. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2019, 95, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, R.M.; Bell, A.; Currie, M.J.; Deeks, L.S.; Cooper, G.; Martin, S.J.; Del Rosario, R.; Hocking, J.S.; Bowden, F.J. ”Catching chlamydia”: Combining cash incentives and community pharmacy access for increased chlamydia screening, the view of young people. Aust. J. Prim. Health 2015, 21, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeks, L.S.; Cooper, G.M.; Currie, M.J.; Martin, S.J.; Parker, R.M.; Del Rosario, R.; Hocking, J.S.; Bowden, F.J. Can pharmacy assistants play a greater role in public health programs in community pharmacies? Lessons from a chlamydia screening study in Canberra, Australia. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2014, 10, 801–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downing, S.G.; Payze, C.; Doyle-Adams, S.; Gorton, C. Emergency contraception over-the-counter: Practices and attitudes of pharmacists and pharmacy assistants in far North Queensland. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2011, 51, 527–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryder, H.; Aspden, T.; Sheridan, J. The Hawke’s Bay Condom Card Scheme: A qualitative study of the views of service providers on increased, discreet access for youth to free condoms. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2015, 2001, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, B.C.; Harris, I.B.; Beckman, T.J.; Reed, D.A.; Cook, D.A. Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patton, M. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. Available online: http://lst-iiep.iiep-unesco.org/cgi-bin/wwwi32.exe/[in=epidoc1.in]/?t2000=018602/(100) (accessed on 26 October 2020).

- Hussainy, S.Y.; Stewart, K.; Chapman, C.B.; Taft, A.J.; Amir, L.H.; Hobbs, M.K.; Shelley, J.M.; Smith, A.M. Provision of the emergency contraceptive pill without prescription: Attitudes and practices of pharmacists in Australia. Contraception 2011, 83, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlow, L.A.V.; Waller, J.; Evans, R.E.C.; Wardle, J. Predictors of interest in HPV vaccination: A study of British adolescents. Vaccine 2009, 27, 2483–2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, R.J.; Bissell, P.; Wingfield, J. Ethical, religious and factual beliefs about the supply of emergency hormonal contraception by UK community pharmacists. J. Fam. Plan. Reprod. Health Care 2008, 34, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Given, L. The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods. 2008. Available online: http://sk.sagepub.com/reference/research (accessed on 26 October 2020).

- Green, J.; Thorogood, N. Qualitative Methods for Health Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Timonen, V.; Foley, G.; Conlon, C. Challenges When Using Grounded Theory. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2018, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Famiyeh, I.-M.; MacKeigan, L.; Thompson, A.; Kuluski, K.; McCarthy, L.M. Exploring pharmacy service users’ support for and willingness to use community pharmacist prescribing services. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2019, 15, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, M.C.; Silver, K.; Watkins, R. How does the public conceptualise the quality of care and its measurement in community pharmacies in the UK: A qualitative interview study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e027198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindi, A.M.K.; Schafheutle, E.I.; Jacobs, S. Patient and public perspectives of community pharmacies in the United Kingdom: A systematic review. Health Expect. 2018, 21, 409–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, P.-P.; Braunack-Mayer, A. Perspectives on privacy in the pharmacy: The views of opioid substitution treatment clients. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2019, 15, 1021–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhital, R.; Whittlesea, C.M.; Norman, I.J.; Milligan, P. Community pharmacy service users’ views and perceptions of alcohol screening and brief intervention. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2010, 29, 596–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NHS England. Advanced Service Specification—NHS Community Pharmacist Consultation Service. 2019. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/advanced-service-specification-nhs-pharmacist-consultation-service.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2020).

- Mooney-Somers, J.; Lau, A.; Bateson, D.J.; Richters, J.; Stewart, M.; Black, K.I.; Nothnagle, M. Enhancing use of emergency contraceptive pills: A systematic review of women’s attitudes, beliefs, knowledge, and experiences in Australia. Health Care Women Int. 2018, 40, 174–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hindi, A.M.K.; Schafheutle, E.I.; Jacobs, S. Applying a whole systems lens to the general practice crisis: Cross-sectional survey looking at usage of community pharmacy services in England by patients with long-term respiratory conditions. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e032310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poria, Y.; Coyle, A.; Desombre, T. Chapter Fourteen Serving all the Community? The Views and Preferences of Lesbian and Gay Consumers of Health Care. Qual. Health Care Strateg. Issues Health Care Manag. 2019, 1998, 1998b. [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw, M.; Tomany-Korman, S.; Flores, G. Language barriers to prescriptions for patients with limited English proficiency: A survey of pharmacies. Pediatrics 2007, 120, e225–e235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fejzic, J.; Barker, M. Pharmacy practitioners’ lived experiences of culture in multicultural Australia: From perceptions to skilled practice. PLoS ONE 2019, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwei, R.J.; Del Pozo, S.; Agger-Gupta, N.; Alvarado-Little, W.; Bagchi, A.; Chen, A.H.; Diamond, L.; Gany, F.; Wong, D.; Jacobs, E.A. Changes in research on language barriers in health care since 2003: A cross-sectional review study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 54, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilverding, A.T.; Mager, N.A.D. Pharmacists’ attitudes regarding provision of sexual and reproductive health services. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2017, 57, 493–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindi, A.M.K.; Jacobs, S.; Schafheutle, E.I. Solidarity or dissonance? A systematic review of pharmacist and GP views on community pharmacy services in the UK. Health Soc Care Community 2019, 27, 565–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Loo, I.H.M.; Dukers-Muijrers, N.H.T.M.; Heuts, R.; van der Sande, M.A.B.; Hoebe, C.J.P.A. Screening for HIV, hepatitis B and syphilis on dried blood spots: A promising method to better reach hidden high-risk populations with self-collected sampling. PLoS ONE 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauly, J.; Atherton, H.; Kimani, P.K.; Ross, J. Utilisation of pharmacy-based sexual and reproductive health services: A quantitative retrospective study. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Umbrella Pharmacy Service | Umbrella’s Pharmacy Services | Eligibility by Age | Eligibility by Sex | Tier |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contraception Services | Emergency Contraceptive Pill | 13–60 | Female | Tier 1 and Tier 2 |

| Referral or Appointment for the copper coil at closest sexual health clinic | 13–60 | Female | Tier 1 and Tier 2 | |

| Oral Contraception | 13–60 | Female | Tier 2 | |

| Contraceptive Injection | 13–60 | Female | Tier 2 | |

| Condoms | ≥13 | Female and Male | Tier 1 and Tier 2 | |

| STI Testing Services | Collection of pre-ordered STI self-sampling kits | ≥16 | Female and Male | Tier 1 and Tier 2 |

| STI self-sampling kits provided directly to pharmacy users | ≥16 | Female and Male | Tier 2 | |

| STI self-sampling kit testing for chlamydia and gonorrhoea only | 15–24 | Female | Tier 2 | |

| STI Treatment Service | Chlamydia Treatment | ≥13 | Female and Male | Tier 2 |

| Pharmacy Staff Characteristics | Pharmacists | Pharmacy Healthcare Assistants | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Gender | |||

| Female | Male | Female | Male | |

| Total, n | 4 | 5 | 5 | 1 |

| Age | ||||

| <30 | 3 | 2 | 1 | - |

| 30–39 | 1 | 2 | 2 | - |

| 40–49 | - | 1 | - | 1 |

| ≥50 | - | - | 2 | - |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White/White British | - | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Asian/Asian British | 4 | 2 | 2 | - |

| Black/Black British | - | 2 | - | - |

| Religion | ||||

| Christianity | - | - | 2 | - |

| Islam | 2 | 3 | 1 | - |

| Hinduism | - | 1 | - | - |

| Sikhism | 2 | - | - | - |

| No Religion | - | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Type of Umbrella pharmacy employed at | ||||

| Tier 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | - |

| Tier 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| Tier 1 and Tier 2 | 1 | 1 | - | - |

| Years in profession | ||||

| <5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | - |

| 5–9 | 1 | - | 1 | 1 |

| 10–19 | - | 2 | 2 | - |

| 20–30 | - | 1 | 1 | - |

| Years in current role | ||||

| <5 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 5–9 | - | 2 | 2 | - |

| 10–19 | - | 1 | 1 | - |

| 20–30 | - | - | 1 | - |

| Characteristics of Pharmacy Users | Gender | |

|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | |

| Total number, n | 13 (one of those identified as transgender woman) | 2 |

| 18–24 | 5 | 1 |

| 25–29 | 6 | 1 |

| 30–34 | 2 | - |

| White/White British | 3 | - |

| Asian/Asian British | 3 | 1 |

| Black/Black British | 3 | - |

| Mixed/Multiple Ethnic Group | 4 | 1 |

| Christianity | 3 | - |

| Islam | 2 | - |

| Hinduism | - | 1 |

| Sikhism | - | - |

| No Religion | 7 | 1 |

| Prefer not to say | 1 | - |

| Emergency Contraception | 8 | - |

| Oral Contraception | 2 | - |

| Contraceptive Injection | 1 | - |

| Condoms | 3 | 2 |

| STI Self-Sampling Kits | 4 | |

| Chlamydia Treatment | 3 | 1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gauly, J.; Ross, J.; Parsons, J.; Atherton, H. Staff and Users’ Experiences of Pharmacy-Based Sexual and Reproductive Health Services: A Qualitative Interview Study from the UK. Pharmacy 2020, 8, 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy8040206

Gauly J, Ross J, Parsons J, Atherton H. Staff and Users’ Experiences of Pharmacy-Based Sexual and Reproductive Health Services: A Qualitative Interview Study from the UK. Pharmacy. 2020; 8(4):206. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy8040206

Chicago/Turabian StyleGauly, Julia, Jonathan Ross, Joanne Parsons, and Helen Atherton. 2020. "Staff and Users’ Experiences of Pharmacy-Based Sexual and Reproductive Health Services: A Qualitative Interview Study from the UK" Pharmacy 8, no. 4: 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy8040206

APA StyleGauly, J., Ross, J., Parsons, J., & Atherton, H. (2020). Staff and Users’ Experiences of Pharmacy-Based Sexual and Reproductive Health Services: A Qualitative Interview Study from the UK. Pharmacy, 8(4), 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy8040206