Pharmacists’ Prescribing in Saudi Arabia: Cross-Sectional Study Describing Current Practices and Future Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Sampling

2.2.1. Questionnaire Development

2.2.2. Data Collection

2.2.3. Approach to Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Sample and Response Rate

3.2. Respondents Characteristics

3.3. Perspectives on Pharmacists’ Prescribing

3.4. Perceived Barriers to Pharmacist Prescribing

- (a)

- Legislation—Lack of prescribing legislation for pharmacists and specifically at a national level was a frequently cited barrier that was perceived to prevent pharmacist prescribing in KSA (Box 1).Box 1. Legislation.“There is NO national legislation that supports pharmacists prescribing”“Lack of national legislations to back up and protect pharmacists”“Lack of cooperation between government and institutions to make sure that pharmacists are well oriented to prescribe”

- (b)

- Pharmacists training and competency—participants highlighted the issue of lack of appropriate training that would enable pharmacists to prescribe, both in terms of competency but also as a qualification. There was an emphasis on the need for specified training programs in therapeutic areas along with national certification before granting pharmacists prescriptive authorities (Box 2).Box 2. Pharmacists training and competency.“I think the one important thing to achieve that level is to have qualified pharmacists who have enough experience to minimize the risk of prescribing mistakes”“[…] need specified training, in each specialty…. and need condensed courses and programs to improve pharmacist’s knowledge and practice”“Still need time and more practice”“Need appropriate training and national competency certification”

- (c)

- Physicians’ perceived negativity—most participants believed that there was significant resistance from physicians, which represented a key barrier to implementing any form of pharmacist prescribing practice in KSA (Box 3). This appeared to be related to aspects such as physicians’ lack of awareness of pharmacists and not wanting to work in an inter-disciplinary way.Box 3. Physicians’ perceived negativity.“Lack of physicians’ support and collaboration”“Physicians are not aware of the extent of pharmacists knowledge and abilities”“Doctors don’t like pharmacist to intervene in their job”“This idea is not accepted by multidisciplinary teams”“Physicians resistance only, as patients do trust pharmacists and ask them for advice about their medical conditions”

- (d)

- Healthcare practice culture—many participants believed that there were certain norms within healthcare practice in KSA that represents a barrier to extending pharmacist role to a prescriber. Many respondents referred to how patients are used to seeking medical care only from physicians and that patients view pharmacists only as a dispenser of medications who are not involved in patients’ care (Box 4).Box 4. Healthcare practice culture.“The patient trusts the physician more than pharmacist”“Expectations from patients and other healthcare providers”“For many years prescribing medications was limited to medical doctors”“The nature of how things are processed in the hospital…each person has a specific role”

- (e)

- Limited resources—participants also suggested that there are limitations in resources that could facilitate the adoption of pharmacists’ prescribing in KSA. In this context, participants mentioned that pharmacists do not have enough time to practice as prescribers giving their workload and the demanding nature of their traditional roles as pharmacists. In addition, they mentioned that pharmacists do not have full access to patient’s information to allow them to practice as prescribers (Box 5).Box 5. Limited resources.“No enough time to practice as prescribers”“Pharmacists workload”“The pharmacists are not allowed to get full information about patient case and are not trusted by patients or physicians”

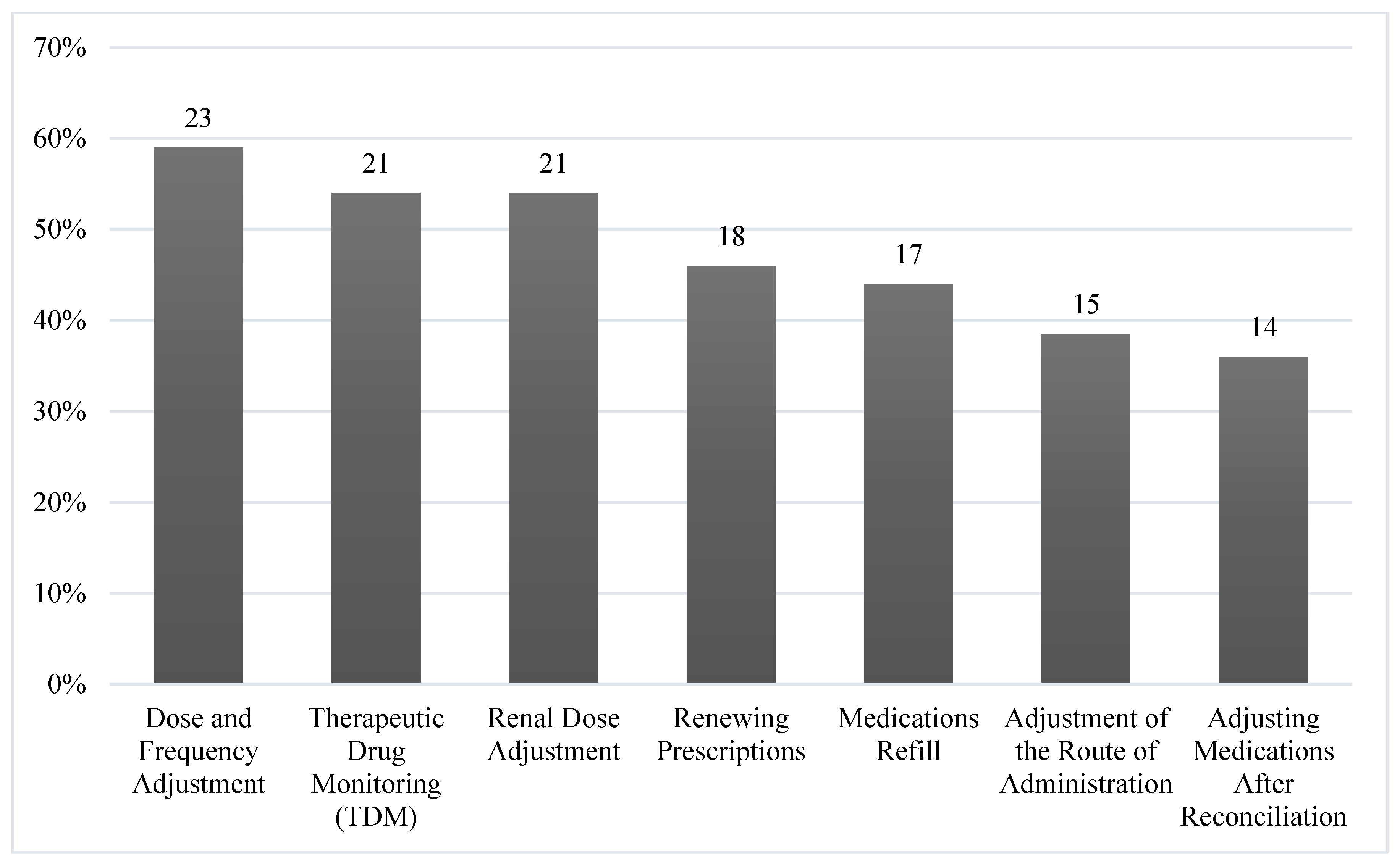

3.5. Pharmacist Prescribing Practice

3.6. Experience of Prescribing Pharmacists

3.7. Comparison between Prescribing and Non-prescribing Pharmacists

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Implications for Policy, Practice and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dunn, S.P.; Birtcher, K.K.; Beavers, C.J.; Baker, W.L.; Brouse, S.D.; Page, R.L., II; Bittner, V.; Walsh, M.N. The role of the clinical pharmacist in the care of patients with cardiovascular disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015, 66, 2129–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvaggi, A.; Nabhani-Gebara, S.; Reeves, S. Expanding pharmacy roles and the interprofessional experience in primary healthcare: A qualitative study. J. Interprof. Care 2017, 31, 110–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schindel, T.J.; Yuksel, N.; Breault, R.; Daniels, J.; Varnhagen, S.; Hughes, C.A. Pharmacists’ learning needs in the era of expanding scopes of practice: Evolving practices and changing needs. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2019, 15, 448–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emmerton, L.; Marriott, J.; Bessell, T.; Nissen, L.; Dean, L. Pharmacists and prescribing rights: Review of international developments. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2005, 2, 217–225. [Google Scholar]

- Nissen, L. Pharmacist prescribing: What are the next steps? Am. J. Health Pharm. 2011, 68, 2357–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cope, L.C.; Abuzour, A.S.; Tully, M.P. Nonmedical prescribing: Where are we now? Ther. Adv. Drug Saf. 2016, 7, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmichael, J.M.; O’Connell, M.B.; Devine, B.; Kelly, H.W.; Ereshefsky, L.; Linn, W.D.; Simmel, G.L. Collaborative drug therapy management by pharmacists. Pharmacotherapy 1997, 17, 1050–1061. [Google Scholar]

- Kay, O.C.; Bajorek, B.V.; Brien, J.A.E. Pharmacist prescribing activities – An electronic survey on the opinions of Australian Pharmacists. J. Pharm. Pract. Res. 2006, 36, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galt, K.A. The key to pharmacist prescribing: Collaboration. Am. J. Health Pharm. 1995, 52, 1696–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebara, T.; Cunningham, S.; MacLure, K.; Awaisu, A.; Pallivalapila, A.; Stewart, D. Stakeholders’ views and experiences of pharmacist prescribing: A systematic review. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018, 84, 1883–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, R.J.; Anderson, C.; Avery, T.; Bisell, P.; Gillaume, L.; Hutchinson, A.; James, V.; Lymn, J.; McIntosh, A.; Murphy, E.; et al. Nurse and pharmacist supplementary prescribing in the UK-A thematic review of the literature. Health Policy 2008, 85, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, J.; Bharmal, M.; Lin, S.W.; Punekar, Y. Survey of pharmacist collaborative drug therapy management in hospitals. Am. J. Health Pharm. 2006, 63, 2489–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, M.; Desborough, J.; Parkinson, A.; Douglas, K.; McDonald, D.; Boom, K. Barriers to pharmacist prescribing: A scoping review comparing the UK, New Zealand, Canadian and Australian experiences. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2019, 27, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isenor, J.E.; Minard, L.V.; Stewart, S.A.; Curran, J.A.; Heidi, D.; Rodrigues, G.; Sketris, I.S. Identification of the relationship between barriers and facilitators of pharmacist prescribing and self-reported prescribing activity using the theoretical domains framework. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2018, 14, 784–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jedai, A.; Qaisi, S.; Al-Meman, A. Pharmacy practice and the health care system in Saudi Arabia. Can. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2016, 69, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhamoudi, A.; Alnattah, A. Pharmacy education in Saudi Arabia: The past, the present, and the future. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2018, 10, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljadhey, H.; Asiri, Y.; Albogami, Y.; Spratto, G.; Alshehri, M. Pharmacy education in Saudi Arabia: A vision of the future. Saudi Pharm. J. 2017, 25, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepler, C.D.; Strand, L.M. Opportunities and responsibilities in pharmaceutical care. Am. J. Health Pharm. 1990, 47, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health. Annual Statistics Book. 2018. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/Statistics/book/Documents/book-Statistics.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2019).

- SSCP, Saudi Society of Clinical Pharmacy. Available online: https://www.sscp.org.sa/ (accessed on 18 March 2020).

- SOS, Saudi Oncology Society. Available online: http://saudioncology.org/main/saudi-oncology-pharmacy-assembly/ (accessed on 4 August 2020).

- Marshall, C.; Rossman, G.B. Designing qualitative research. Sixth edition. SAGE 2015, 29, 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Asiri, Y.A. Emerging frontiers of pharmacy education in Saudi Arabia: The metamorphosis in the last fifty years. Saudi Pharm. J. 2011, 19, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haidari, K.M.; Al-Jazairi, A.S. Establishment of a national pharmacy practice residency program in Saudi Arabia. Am. J. Health Pharm. 2010, 67, 1467–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, J.E.; Nappi, J.M.; Bosso, J.A.; Saseen, J.J.; Hemstreet, B.A.; Halloran, M.A.; Spliner, S.A.; Welty, E.R.; Dobesh, P.P.; Chan, L.-N.; et al. American College of Clinical Pharmacy’s vision of the future: Postgraduate pharmacy residency training as a prerequisite for direct patient care practice. Pharmacotherapy 2006, 26, 722–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alomi, Y.; Aldakheel, S.; Bahadig, F. Pharmacist prescribing system: A new initiative in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Pharmacol. Clin. Sci. 2020, 9, 90–93. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, J.D.; Steers, N.; Adler, D.S.; Kuo, G.M.; Morello, C.M.; Lang, M.; Singh, R.F.; Wood, Y.; Kaplan, R.M.; Mangione, C.M. Primary care-based, pharmacist-physician collaborative medication-therapy management of hypertension: A randomized, pragmatic trial. Clin. Ther. 2014, 36, 1244–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pojskic, N.; MacKeigan, L.; Boon, H.; Austin, Z. Initial perceptions of key stakeholders in Ontario regarding independent prescriptive authority for pharmacists. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2014, 10, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, R.; Grines, L.L. Prescribing authority for pharmacists as viewed by organized pharmacy, organized medicine, and the pharmaceutical industry. Drug Intell. Clin. Pharm. 1988, 22, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auta, A.; Strickland-Hodge, B.; Maz, J. Stakeholders’ views on granting prescribing authority to pharmacists in Nigeria: A qualitative study. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2016, 38, 960–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hill, D.R.; Conroy, S.; Brown, R.C.; Burt, G.A.; Campbell, D. Stakeholder views on pharmacist prescribing in addiction services in NHS Lanarkshire. J. Subst. Use 2014, 19, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auta, A.; Strickland-Hodge, B.; Maz, J.; David, S. Pharmacist prescribing: A cross-sectional survey of the views of pharmacists in Nigeria. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2018, 26, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vracar, D.; Bajorek, B.V. Australian general practitioners’ views on pharmacist prescribing. J. Pharm. Pract. Res. 2008, 38, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, T.; Stewart, D. A qualitative study of UK pharmacy pre-registration graduates’ views and reflections on pharmacist prescribing. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2016, 24, 139–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoti, K.; Hughes, J.; Sunderland, B. Expanded prescribing: A comparison of the views of Australian hospital and community pharmacists. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2013, 35, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makowsky, M.J.; Guirguis, L.M.; Hughes, C.A.; Sadowski, C.A.; Yuksel, N. Factors influencing pharmacists’ adoption of prescribing: Qualitative application of the diffusion of innovations theory. Implement. Sci. 2013, 8, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatah, E.; Braund, R.; Duffull, S.; Tordoff, J. General practitioners’ perceptions of pharmacists’ new services in New Zealand. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2012, 34, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Latif, M.M.M. Hospital doctors’ views of, collaborations with and expectations of clinical pharmacists. Eur. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2017, 24, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, D.; Jebara, T.; Cunningham, S.; Awaisu, A.; Pallivalapila, A.; MacLure, K. Future perspectives on nonmedical prescribin. Ther. Adv. Drug Saf. 2017, 8, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, A.J.; Weaver, K.K. The Continuum of Pharmacist Prescriptive Authority. Ann. Pharmacother. 2016, 50, 778–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, R.J.; Lymn, J.; Anderson, C.; Avery, A.; Bissell, P.; Gillaume, L.; Hutchinson, A.; Murphy, E.; Racliffe, J.; Ward, P. Learning to prescribe—Pharmacists’ experiences of supplementary prescribing training in England. BMC Med. Educ. 2018, 8, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonna, A.P.; Stewart, D.; McCaig, D. An international overview of some pharmacist prescribing models. J. Malta Coll. Pharm. Pract. 2008, 14, 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hobson, R.; Sewell, G. Supplementary prescribing by pharmacists in England. Am. J. Health Pharm. 2006, 63, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham-Clarke, E.; Rushton, A.; Noblet, T.; Marriott, J. Facilitators and barriers to non-medical prescribing—A systematic review and thematic synthesis. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adigwe, O. Non-Medical Prescribing in Chronic Non-Malignant Pain. University of Leeds. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Maddox, C.; Halsall, D.; Hall, J.; Tully, M.P. Factors influencing nurse and pharmacist willingness to take or not take responsibility for non-medical prescribing. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2016, 12, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Child, D.; Hirsch, C.; Berry, M. Health care professionals’ views on hospital pharmacist prescribing in the United Kingdom. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 1998, 6, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuksel, N.; Eberhart, G.; Bungard, T.J. Prescribing by pharmacists in Alberta. Am. J. Health Pharm. 2008, 65, 2126–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mcintosh, T.; Munro, K.; Mclay, J.; Stewart, D. A cross sectional survey of the views of newly registered pharmacists in Great Britain on their potential prescribing role: A cautious approach. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2012, 73, 656–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snyder, M.E.; Earl, T.R.; Gilchirst, S.; Greenberg, M.; Heisler, H.; Revels, M.; Matson-Koffman, D. Collaborative drug therapy management: Case studies of three community-based models of care. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2015, 12, E39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Variables | % (n) | |

|---|---|---|

| Females | 52.5 (72) | |

| Age group | 20–29 years | 43.8 (60) |

| 30–39 years | 39.4 (54) | |

| 40–49 years | 13.1 (18) | |

| >50 years | 3.7 (5) | |

| Practice setting | Government hospital | 76.6 (105) |

| Private hospital | 23.4 (32) | |

| Geographical region | Makkah | 57 (78) |

| Riyadh | 19 (26) | |

| Eastern Province | 16.8 (23) | |

| Madinah | 2.9 (4) | |

| Hai’l | 1.5 (2) | |

| Qassim | 0.7 (1) | |

| Tabuk | 0.7 (1) | |

| Jizan | 0.7 (1) | |

| Baha | 0.7 (1) | |

| Pharmacy practice area | Administration | 13.1 (18) |

| Inpatient pharmacy | 16.8 (23) | |

| Outpatient pharmacy | 24 (33) | |

| Clinical pharmacy | 35.9 (49) | |

| Others | 10.2 (14) | |

| Years of practice as a qualified pharmacist | <5 years | 47.5 (65) |

| 6 to 10 years | 24 (33) | |

| 11 to 15 years | 10.2 (14) | |

| 16 to 20 years | 11.7 (16) | |

| 21 to 25 years | 4.4 (6) | |

| >25 years | 2.2 (3) | |

| Highest professional or academic degrees | BSc.Pharm | 19.7 (27) |

| Pharm.D | 40.2 (55) | |

| MPharm | 2.2 (3) | |

| PG Diploma | 4.4 (6) | |

| Master’s degree | 8 (11) | |

| PGY1 | 13.1 (18) | |

| PGY2 | 10.2 (14) | |

| Ph.D | 2.2 (3) | |

| Professional positions | Outpatient pharmacist | 24 (33) |

| Inpatient pharmacist | 19.7 (27) | |

| Pharmacy practice resident | 8 (11) | |

| Clinical pharmacist | 10.2 (14) | |

| Specialized clinical pharmacist | 16.1 (22) | |

| Deputy director | 1.5 (2) | |

| Pharmacy director | 8.8 (12) | |

| Other | 11.7 (16) | |

| Monthly income $ | <SR * 10,000 | 12.4 (17) |

| SR 10,000–SR 20,000 | 66.4 (91) | |

| SR 20,000–SR 30,000 | 9.5 (13) | |

| SR 30,000–SR 40,000 | 5.8 (8) | |

| >SR 40,000 | 2.9 (4) | |

| Statements | Responses* % (n) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly Agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly Disagree | Median Score (IQR) * | |

| There is national legislation that support pharmacists’ prescribing in KSA | 5.8 (8) | 24.8 (34) | 21.9 (30) | 30.7 (42) | 16.8 (23) | 3 (2–4) |

| Legislation to support pharmacist prescribing should be available in KSA | 35.1 (48) | 41.6 (57) | 14.6 (20) | 5.8 (8) | 2.9 (4) | 4 (4–5) |

| Pharmacists should be allowed to prescribe independently of the medical team | 14.6 (20) | 27 (37) | 23.4 (32) | 24 (33) | 11 (15) | 3 (2–4) |

| Pharmacists should only be allowed to prescribe in collaboration with physicians | 28.5 (39) | 40.8 (56) | 19 (26) | 8.8 (12) | 2.9 (4) | 4 (3–5) |

| Prescribing should be limited to competent clinical pharmacists | 32.1 (44) | 32.8 (45) | 16.1 (22) | 11 (15) | 8 (11) | 4 (3–5) |

| Pharmacists should be trained in specific therapeutic areas before they are allowed to prescribe | 61.3 (84) | 29.2 (40) | 5.1 (7) | 2.9 (4) | 1.5 (2) | 5 (4–5) |

| Pharmacist prescribing will allow greater patient access to medications | 40.2 (55) | 42.3 (58) | 14.6 (20) | 2.2 (3) | 0.7 (1) | 4 (4–5) |

| Pharmacist prescribing helps patients avoid physician follow-up | 21.2 (29) | 30.7 (42) | 27.7 (38) | 12.4 (17) | 8 (11) | 4 (3–4) |

| Pharmacists’ prescribing reduces prescribing errors | 33.6 (46) | 29.9 (41) | 28.5 (39) | 5.8 (8) | 2.2 (3) | 4 (3–5) |

| Pharmacists’ prescribing will increase the quality of care for patients | 38.7 (53) | 37.9 (52) | 19.7 (27) | 2.2 (3) | 1.5 (2) | 4 (4–5) |

| Pharmacist prescribing increases pharmacists professional responsibility | 49.6 (68) | 39.4 (54) | 7.3 (10) | 2.2 (3) | 1.5 (2) | 5 (4–5) |

| Prescribing increases pharmacist’s workload | 29.2 (40) | 40.9 (56) | 22.6 (31) | 5.8 (8) | 1.5 (2) | 4 (3–5) |

| Prescribing increases pharmacist’s job satisfaction | 37.9 (52) | 43.1 (59) | 11.7 (16) | 5.1 (7) | 2.2 (3) | 4 (4–5) |

| Pharmacists’ prescribing allow greater utilization of pharmacist’s skills and experience | 46.7 (64) | 37.9 (52) | 11 (15) | 2.9 (4) | 1.5 (2) | 4 (4–5) |

| Questions | % (n) | |

|---|---|---|

| Type of prescribing model practiced by the pharmacist | Independent prescribing | 18 (7) |

| Collaborative prescribing | 48.7 (19) | |

| Both independent and collaborative prescribing | 33.3 (13) | |

| Prescriptive authority was given to the pharmacist by… | The institution he/she work in | 18 (7) |

| A collaborative agreement with the medical team | 30.7 (12) | |

| A collaborative agreement with a medical team that was approved by the administration of the institution | 51.3 (20) | |

| Prescribing training received (other than postgraduate clinical training or qualification) | Yes | 53.8 (21) |

| No | 46.2 (18) | |

| Access to patients’ medical records during prescribing | Yes | 82 (32) |

| No | 18 (7) | |

| As a result of pharmacists’ prescribing, doctors are prescribing … | less | 41 (16) |

| more | 35.9 (14) | |

| The same amount | 23.1 (9) | |

| Time spent (in minutes) to complete a prescription including documentation in patients’ records | 15 (5–20) * | |

| Prescriptions issued by pharmacists per week | 10 (5–35) * | |

| Statements | Responses *, % (n) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly Agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly Disagree | Median Score (IQR) * | |

| I am confident to prescribe the appropriate treatment for patients in my practice area | 51.2 (20) | 38.5 (15) | 5.1 (2) | 2.6 (1) | 2.6 (1) | 5 (4–5) |

| Being a prescriber makes my job more satisfying | 46.2 (18) | 41 (16) | 10.2 (4) | 2.6 (1) | 0 | 4 (4–5) |

| I am aware of my limitations as a prescriber | 53.8 (21) | 38.5 (15) | 7.7 (3) | 0 | 0 | 5 (4–5) |

| Prescribing has increased my workload | 35.9 (14) | 38.5 (15) | 12.8 (5) | 5.1 (2) | 7.7 (3) | 4 (3–5) |

| I am satisfied by the level of training I received before prescribing | 41 (16) | 33.3 (13) | 12.8 (5) | 7.7 (3) | 5.1 (2) | 4 (3–5) |

| The medical team I work with are cooperative and supportive to my prescribing practice | 48.7 (19) | 28.2 (11) | 12.8 (5) | 7.7 (3) | 2.6 (1) | 4 (4–5) |

| I faced resistance from physicians or other healthcare professionals during my prescribing practice | 12.8 (5) | 23.1 (9) | 28.2 (11) | 23.1 (9) | 12.8 (5) | 3 (2–4) |

| My institution had been supportive of pharmacist prescribing | 30.8 (12) | 35.9 (14) | 25.6 (10) | 5.1 (2) | 2.6 (1) | 4 (3–5) |

| I prefer to prescribe only within a collaborative agreement with physicians | 38.5 (15) | 38.5 (15) | 15.3 (6) | 7.7 (3) | 0 | 4 (4–5) |

| I prefer to practice as an independent prescriber in my area of expertise | 25.6 (10) | 30.8 (12) | 25.6 (10) | 10.3 (4) | 7.7 (3) | 4 (3–5) |

| Receiving more training in prescribing will benefit me as a prescriber | 69.2 (27) | 23.1 (9) | 7.7 (3) | 0 | 0 | 4 (4–5) |

| Characteristics | Prescribing Pharmacists (n = 39) % (n) | Non-Prescribing Pharmacists (n = 98) % (n) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 46.2 (18) | 48 (47) | 0.849 |

| Female | 53.8 (21) | 52 (51) | |

| Age group | |||

| 20–29 years | 35.9 (14) | 46.9 (46) | 0.583 |

| 30–39 years | 46.2 (18) | 36.7 (36) | |

| 40–49 years | 12.8 (5) | 13.3 (13) | |

| >50 years | 5.1 (2) | 3.1 (3) | |

| Doctor of pharmacy degree | |||

| Yes | 84.6 (33) | 56.1 (55) | 0.003 |

| No | 15.4 (6) | 43.9 (43) | |

| Complete pharmacy residency | |||

| Yes | 59 (23) | 9.3 (9) | 0.001 |

| No | 41 (16) | 90.7 (88) | |

| Healthcare institution | |||

| Governmental | 79.5 (31) | 75.5 (74) | 0.663 |

| Private | 20.5 (8) | 24.5 (24) | |

| Practice setting | |||

| Clinical pharmacy | 61.5 (24) | 25.5 (25) | 0.001 |

| Non-clinical | 38.5 (15) | 74.5 (73) | |

| Years of practice | |||

| <5 years | 41 (16) | 50 (49) | 0.466 |

| 6 to 10 years | 31 (12) | 21.4 (21) | |

| 11 to 15 years | 10 (4) | 10.2 (10) | |

| 16 to 20 years | 8 (3) | 13.3 (13) | |

| 21 to 25 years | 5 (2) | 4.1 (4) | |

| >25 years | 5 (2) | 1 (1) | |

| Monthly income $ | |||

| <SR 10,000 | 15.4 (6) | 11.2 (11) | 0.269 |

| SR 10,000–SR 20,000 | 67 (26) | 66.3 (65) | |

| SR 20,000–SR 30,000 | 5.1 (2) | 11.2 (11) | |

| SR 30,000–SR 40,000 | 3 (1) | 7.1 (7) | |

| >SR 40,000 | 8 (3) | 1 (1) | |

| Average working hours in a typical week | 47.3 (23) * | 44 (6.2) | 0.141 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ajabnoor, A.M.; Cooper, R.J. Pharmacists’ Prescribing in Saudi Arabia: Cross-Sectional Study Describing Current Practices and Future Perspectives. Pharmacy 2020, 8, 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy8030160

Ajabnoor AM, Cooper RJ. Pharmacists’ Prescribing in Saudi Arabia: Cross-Sectional Study Describing Current Practices and Future Perspectives. Pharmacy. 2020; 8(3):160. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy8030160

Chicago/Turabian StyleAjabnoor, Alyaa M., and Richard J. Cooper. 2020. "Pharmacists’ Prescribing in Saudi Arabia: Cross-Sectional Study Describing Current Practices and Future Perspectives" Pharmacy 8, no. 3: 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy8030160

APA StyleAjabnoor, A. M., & Cooper, R. J. (2020). Pharmacists’ Prescribing in Saudi Arabia: Cross-Sectional Study Describing Current Practices and Future Perspectives. Pharmacy, 8(3), 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy8030160