The Roles and Responsibilities of Community Pharmacists Supporting Older People with Palliative Care Needs: A Rapid Review of the Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Home Care (HC) services—where the person receives care in their home dwelling; or

- Residential Aged Care (RAC) services—where the individual is provided care within a Residential Aged Care Home (RACH).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.2. Data Extraction

2.3. Synthesis of Data

3. Results

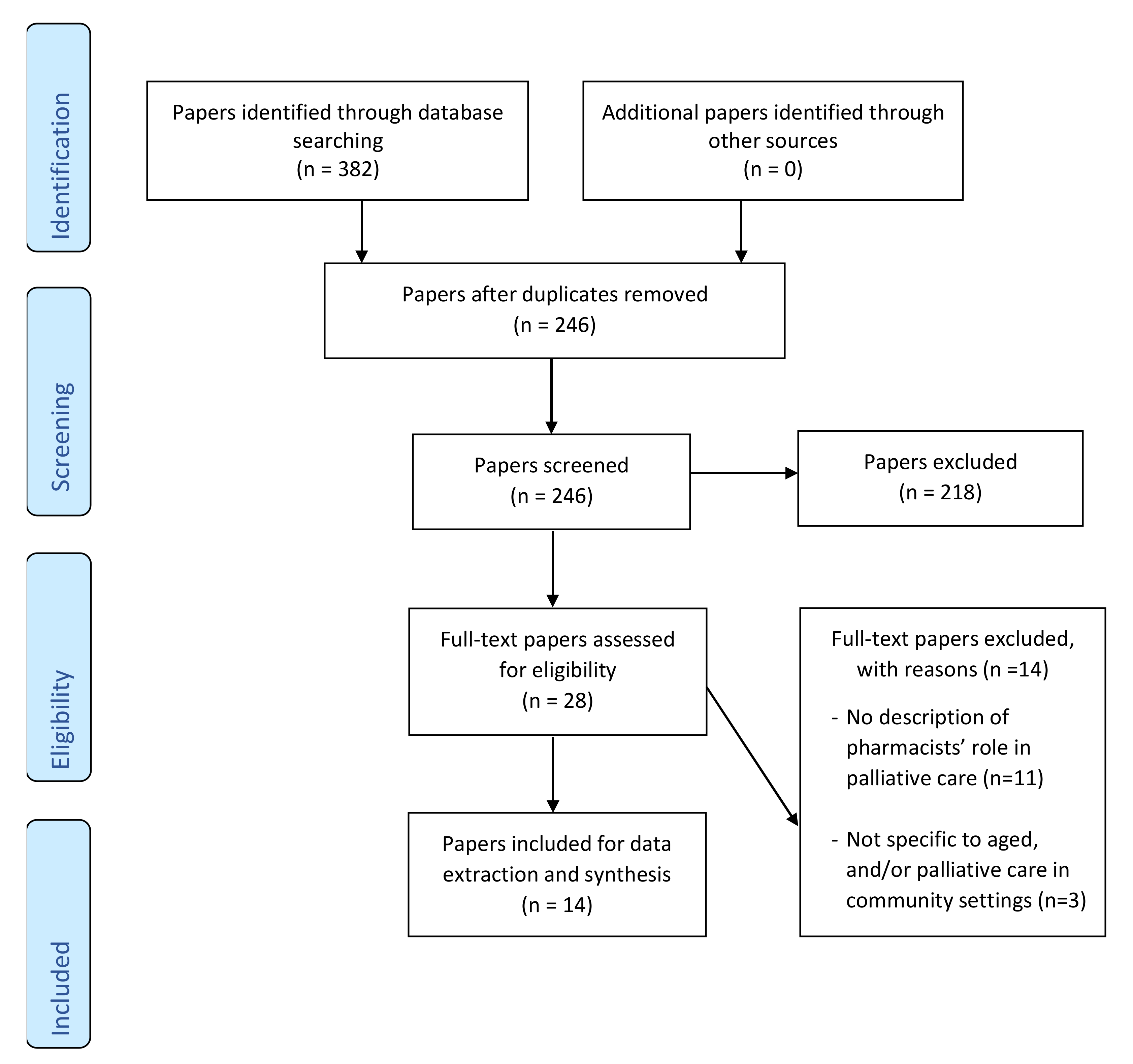

3.1. Literature Search, Screening, and Selection of Papers

3.2. Characteristics of the Selected Papers

3.3. Data Extraction

- (1)

- Type of care delivery;

- (2)

- Work context of the pharmacist; and

- (3)

- Supportive professional and personal characteristics as soft skills.

3.3.1. Theme One: Type of Care Delivery

3.3.2. Theme Two: Work Setting of the Pharmacist

- Real time liaison with GPs as part of case conferencing [22];

- Clarification of information relating to the prescription, including changes to the packing of dose administration aids [23]; and

- Anticipating which subcutaneous medicines to stock that are useful in managing symptoms expected in the last days of life [25].

3.3.3. Theme Three: Supportive Professional and Personal Characteristics as Soft Skills

- Writing medication review recommendations as a “medication management plan” to make it more acceptable and relevant for GPs to provide feedback [22];

- Supporting and maintaining trusting relationships with a multidisciplinary team of practitioners [22];

- Demonstrating a positive and helpful attitude to medication prescribers and other clinicians [22];

- Communicating with medication prescribers in a clear and honest manner [22]; and

- Following-up with medication prescribers if no response to medication reviews outcome reports are received [32].

4. Discussion

Implications for Policy and Practice in Aged Care

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Causes of Death, Australia 2018; ABS Cat No. 3303.0; ABS: Canberra, Australia, 2018.

- Barnett, K.; Mercer, S.W.; Norbury, M.; Watt, G.; Wyke, S.; Guthrie, B. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: A cross-sectional study. Lancet 2012, 380, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, A.T.; Falster, M.O.; Litchfield, M.; Pearson, S.-A.; Etherton-Beer, C. Polypharmacy among older Australians, 2006–2017: A population-based study. Med. J. Aust. 2019, 211, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pharmaceutical Society of Australia. Medicines Safety: Take Care; PSA: Canberra, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Weir, N.M.; Newham, R.; Bennie, M. A literature review of human factors and ergonomics within the pharmacy dispensing process. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aitken, M.; Gorokhovich, L. Advancing the Responsible Use of Medicines: Applying Levers for Change. 2012. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2222541 (accessed on 12 May 2020).

- Stowasser, D.A.; Allinson, Y.M.; O’Leary, M. Understanding the medicines management pathway. J. Pharm. Pract. Res. 2004, 34, 293–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sluggett, J.K.; Ilomäki, J.; Seaman, K.L.; Corlis, M.; Bell, J.S. Medication management policy, practice and research in Australian residential aged care: Current and future directions. Pharmacol. Res. 2017, 116, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pharmaceutical Society of Australia. Pharmacist in 2023: For Patients, for Our Profession, for Australia’s Health System; PSA: Canberra, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, D.T.; Joyce, B.; Clayman, M.L.; Dy, S.; Ehrlich-Jones, L.; Emanuel, L.; Hauser, J.; Paice, J.; Shega, J.W. Hospice providers’ key approaches to support informal caregivers in managing medications for patients in private residences. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2012, 43, 1060–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, B.A.; Rosenwax, L.K.; Murray, K.; Currow, D.C. Early admission to community-based palliative care reduces use of emergency departments in the ninety days before death. J. Palliat. Med. 2013, 16, 774–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.F. Pharmacist-led home medicines review and residential medication management review: The Australian model. Drugs Aging 2016, 33, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, P.P.; Molina, J.A.; Cheah, J.; Chan, S.C.; Lim, B.P. The evolving role of the community pharmacist in chronic disease management-a literature review. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 2010, 39, 861–867. [Google Scholar]

- Khangura, S.; Polisena, J.; Clifford, T.J.; Farrah, K.; Kamel, C. Rapid review: An emerging approach to evidence synthesis in health technology assessment. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 2014, 30, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Antony, J.; Zarin, W.; Strifler, L.; Ghassemi, M.; Ivory, J.; Perrier, L.; Hutton, B.; Moher, D.; Straus, S.E. A scoping review of rapid review methods. BMC Med. 2015, 13, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarivate Analytics. EndNote. Available online: https://endnote.com/ (accessed on 24 December 2019).

- Covidence. Better Systematic Review Management. Available online: https://www.covidence.org/home (accessed on 9 December 2019).

- Walden University Library. Evidence-Based Practice Research: Evidence Types. Available online: https://academicguides.waldenu.edu/library/healthevidence/types (accessed on 7 January 2020).

- Malterud, K. Systematic text condensation: A strategy for qualitative analysis. Scand. J. Public Health 2012, 40, 795–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, E.; Nair, S. New horizons in care home medicine. Age Ageing 2014, 43, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crecelius, C.A. Pain Control: No Time to Rest on Our Laurels: Under F309, providers are expected to identify circumstances in which pain can be anticipated. Caring Ages 2006, 7, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Disalvo, D.; Luckett, T.; Bennett, A.; Davidson, P.; Agar, M. Pharmacists’ perspectives on medication reviews for long-term care residents with advanced dementia: A qualitative study. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2019, 41, 950–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliott, R.A.; Lee, C.Y.; Beanland, C.; Vakil, K.; Goeman, D. Medicines Management, Medication Errors and Adverse Medication Events in Older People Referred to a Community Nursing Service: A Retrospective Observational Study. Drugs Real World Outcomes 2016, 3, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, H. Home care of the frail elderly and the terminally ill. Can. Fam. Physician 1984, 30, 665–667. [Google Scholar]

- Kuruvilla, L.; Weeks, G.; Eastman, P.; George, J. Medication management for community palliative care patients and the role of a specialist palliative care pharmacist: A qualitative exploration of consumer and health care professional perspectives. Palliat. Med. 2018, 32, 1369–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaMantia, M.A.; Scheunemann, L.P.; Viera, A.J.; Busby-Whitehead, J.; Hanson, L.C. Interventions to Improve Transitional Care Between Nursing Homes and Hospitals: A Systematic Review. J. Am. Geriat. Soc. 2010, 58, 777–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.M. There’s No Place Like Home: A Pharmacist Fills the Need. Consult. Pharm. 2011, 26, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meade, V. Senior Care Pharmacy Profile: Grace Lawrence. Consult. Pharm. 2006, 21, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noyce, P.R. Intramural and extramural health care in the United Kingdom. Pharm. Weekbl. 1990, 12, 19–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pruskowski, J.; Handler, S.M. The DE-PHARM Project: A Pharmacist-Driven Deprescribing Initiative in a Nursing Facility. Consult. Pharm. 2017, 32, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, B.K.; Bell, C.L.; Inaba, M.; Masaki, K.H. Outcomes of Polypharmacy in Nursing Home Residents. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2012, 28, 217–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tjia, J.; Velten, S.J.; Parsons, C.; Valluri, S.; Briesacher, B.A. Studies to Reduce Unnecessary Medication Use in Frail Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Drugs Aging 2013, 30, 285–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tait, P.; Horwood, C.; Hakendorf, P.; To, T. Improving community access to terminal phase medicines through the implementation of a ‘Core Medicines List’in South Australian community pharmacies. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Health, PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC). Combined Review of Fifth Community Pharmacy Agreement Medication Management Programmes: Final Report; Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2015.

- Australian Government Department of Health. Medication Management Review Data. Available online: https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/Medication-Management-Review-Data (accessed on 3 March 2020).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2016 Census of Population and Housing: General Community Profile. Catalogue Number 2001.0. Available online: https://datapacks.censusdata.abs.gov.au/datapacks/ (accessed on 2 March 2020).

- Pharmacy Programs Administrator (PPA). Program Rules: Home Medicines Review. Available online: https://www.ppaonline.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/HMR-Program-Rules.pdf (accessed on 26 May 2020).

- Pharmacy Programs Administrator (PPA). Program Rules: Residential Medication Management Review. Available online: https://www.ppaonline.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/RMMR-Program-Rules-COVID-19.pdf (accessed on 26 May 2020).

- Australian Government. Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety, Interim Report: Neglect. Available online: https://agedcare.royalcommission.gov.au/publications/Pages/interim-report.aspx (accessed on 22 March 2020).

- Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet. Media Release: Response to Aged Care Royal Commission Interim Report 2019. Available online: https://www.pm.gov.au/media/response-aged-care-royal-commission-interim-report (accessed on 17 December 2019).

- Pharmaceutical Society of Australia. National Competency Standards Framework for Pharmacists in Australia. Available online: https://my.psa.org.au/s/article/2016-Competency-Framework (accessed on 4 August 2020).

- Pousinho, S.; Morgado, M.; Falcão, A.; Alves, G. Pharmacist interventions in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J. Manag. Care Spec. Pharm. 2016, 22, 493–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazen, A.C.; De Bont, A.A.; Boelman, L.; Zwart, D.L.; De Gier, J.J.; De Wit, N.J.; Bouvy, M. The degree of integration of non-dispensing pharmacists in primary care practice and the impact on health outcomes: A systematic review. Pharmacy A 2018, 14, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkle, A. Pharmacist Innovation in South Australia. Available online: https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/pharmacist-innovation-south-australia/ (accessed on 3 March 2020).

- Paola, S. Working Together: Aged Care Pharmacists. Available online: https://ajp.com.au/columns/working-together/working-together-aged-care-pharmacists/ (accessed on 3 March 2020).

- Rowley, G. Appreciating diversity at the end of life. In CareSearch Blog: Palliative Perspectives; Care Search, Flinders University Adelaide: Bedford Park, Australia, 2020; Volume 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Productivity Commission. Efficiency in Health: Productivity Commission Research Paper; Productivity Commission: Canberra, Australia, 2015.

- Featherstone, R.M.; Dryden, D.M.; Foisy, M.; Guise, J.-M.; Mitchell, M.D.; Paynter, R.A.; Robinson, K.A.; Umscheid, C.A.; Hartling, L. Advancing knowledge of rapid reviews: An analysis of results, conclusions and recommendations from published review articles examining rapid reviews. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Criterion | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Population of interest | Pharmacists practising predominantly in dispensing or non-dispensing role. |

| 2. | Settings of interest | Community setting comprising dispensing pharmacy, general medical practice, residential aged care facility, Aboriginal health services, and peoples’ own home. |

| 3. | Phenomenon of interest | Roles and responsibilities of community pharmacists supporting older people aged 65 years and over and their carer living in the community with palliative care needs. |

| 4. | Types of studies | Quantitative or qualitative studies, including peer-reviewed journal articles and grey literature documents. Studies were selected if they reported one or more of the inclusion criteria (i.e., 1–3) outlined above. |

| Level Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Level I | Experimental, randomized controlled trial (RCT), systematic review RTCs with or without meta-analysis |

| Level II | Quasi-experimental studies, systematic review of a combination of RCTs and quasi-experimental studies, or quasi-experimental studies only, with or without meta-analysis |

| Level III | Nonexperimental, systematic review of RCTs, quasi-experimental with/without meta-analysis, qualitative, qualitative systematic review with/without meta-synthesis |

| Level IV | Respected authorities’ opinions, nationally recognized expert committee or consensus panel reports based on scientific evidence |

| Level V | Literature reviews, quality improvement, program evaluation, financial evaluation, case reports, nationally recognized expert(s) opinion based on experiential evidence |

| Author, Year | Title | Study Design | Setting | Country | Level of Evidence | Count of Data Elements | Summary Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burns, 2014 [20] | New horizons in care home medicine | Systematic review of experimental, quasi experimental, and non-experimental studies | Residential Aged Care Home (RACH) | UK | Level III | 8 | Reviews role of RACH staff including pharmacists in integrated models of care supporting better outcomes for older people. |

| Crecelius, 2006 [21] | Pain Control: No Time to Rest on Our Laurels | Expert opinion | RACH | USA | Level V | 7 | Provides expert commentary on pain management for older people living in RACH environments |

| Disalvo, 2019 [22] | Pharmacists’ perspectives on medication reviews for long-term care residents with advanced dementia: a qualitative study | Qualitative study using semi-structured interview | RACH | Australia | Level III | 29 | Explores pharmacist perspectives of the Australian Government funded residential medication management review and its role improving the quality and safety of prescribing for people with advanced dementia. |

| Elliott, 2016 [23] | Medicines Management, Medication Errors and Adverse Medication Events in Older People Referred to a Community Nursing Service: A Retrospective Observational Study | Retrospective records audit and telephone interview | Home Care | Australia | Level III | 12 | Explores the characteristics of older people referred for medicines management support, type of support provided, medication errors, and Adverse Drug Reactions. |

| Hays, 1984 [24] | Home Care of the Frail Elderly And the Terminally Ill | Expert opinion | Home Care | UK | Level V | 5 | Discusses general principles of managing elderly and terminally ill patients in a home environment. |

| Kuruvilla, 2018 [25] | Medication management for community palliative care patients and the role of a specialist palliative care pharmacist: A qualitative exploration of consumer and health care professional perspectives | Qualitative study using focus group | Both RACH and Home Care | Australia | Level III | 20 | Explores the gaps in the current model of community palliative care services on medication management and the role of a pharmacist in addressing these. |

| LaMantia, 2010 [26] | Interventions to Improve Transitional Care Between Nursing Homes and Hospitals: A Systematic Review | Systematic review of experimental, quasi experimental, and non-experimental studies | RACH | USA | Level III | 7 | Identifies and evaluates interventions to improve the communication of accurate and appropriate medication lists and advance directives for older people who transition between a RACH and a hospital. |

| Martin, 2011 [27] | There’s No Place Like Home: A Pharmacist Fills the Need | Case report | Home Care | USA | Level V | 14 | Describes the practice of a pharmacist working with older people receiving home care. |

| Meade, 2006 [28] | Innovative Services for Assisted Living, Hospice, and the Community | Case report | Both RACH and Home Care | USA | Level V | 29 | Describes the practice of a pharmacist who provides medication management services to older people living in a RACH or receiving home care. |

| Noyce, 1990 [29] | Intramural and extramural health care in the United Kingdom | Expert opinion | Both RACH and Home Care | UK | Level V | 8 | Describes the factors that determine whether health care in the United Kingdom is provided in hospital, at home, or through intermediate or shared care arrangements. |

| Prukowski, 2017 [30] | The DE-PHARM Project: A Pharmacist-Driven Deprescribing Initiative in a Nursing Facility | Quality improvement intervention study | RACH | USA | Level V | 10 | Assesses the acceptance of recommendations from the pharmacist to the primary care team regarding the discontinuation of medications used for the management of comorbid diagnoses. |

| Tait, 2017 [33] | Improving community access to terminal phase medicines through the implementation of a “Core Medicines List” in South Australian community pharmacies | Qualitative study using repeat survey | Both RACH and Home Care | Australia | Level III | 14 | Identifies changes in community access to medicines for managing symptoms in the terminal phase following the development of a “Core Medicines List”. |

| Tamura, 2012 [31] | Outcomes of Polypharmacy in Nursing Home Residents | Comprehensive literature review | RACH | USA | Level V | 13 | Reviews the outcomes of polypharmacy in RACHs. |

| Tija, 2013 [32] | Studies to Reduce Unnecessary Medication Use in Frail Older Adults: A Systematic Review | Systematic review of experimental, quasi experimental, and non-experimental studies | Both RACH and Home Care | USA | Level III | 20 | Identifies interventions that reduce the use of unnecessary medications in frail older adults and patients approaching end of life. |

| Theme (n = 3) | % (n) of Data Elements | Definition | Domain (n = 8) | Meaning Unit (n = 37) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of care delivery | 72% (n = 140) | Pharmacists support the medicines management of people living with palliative care needs directly with the patients themselves and indirectly by improving the performance of the organisation. | Clinical review | Reconciling medications; Deprescribing; Guiding the adjustment of medication doses; Identifying medication related problems; Assessing appropriateness and safety of prescribed medications; |

| Supply of medicines | Stocking subcutaneous injections; Dispensing; Returning of unwanted medicines; Delivering Medicines to the home; Supplying medicines to a residential aged care home; Offering a dose administration aid service; Providing medicines information; Counselling and educational intervention | |||

| Clinical governance | Participating on Medicines Advisory Committees in residential aged care home; Educating nursing workforce including carers; Auditing of medications; Developing policies and guidelines | |||

| Work setting of the pharmacist | 20% (n = 40) | Pharmacists collaborate with multidisciplinary workforce to achieve optimal results in patient care. | Community Pharmacy | Clarifying prescriptions with prescribers; Improving access to subcutaneous medicines; Participating in case conferences; Discussing medication review findings |

| Residential Aged Care Homes | Reviewing medicines on admission; Participating in multidisciplinary medication reviews; Participating in case conferences; Understanding patient’s goals of care; Supplying medicines to RACH imprest stock | |||

| General Medical Practice | Offering a clinical resource; Providing medicines information; Improving efficiency of medication reviews | |||

| Supportive professional and personal characteristics as soft skills | 8% (n = 16) | Pharmacists use soft skills in their role to assist and provide support to patients with their medication management. | Soft skills in supporting person-centred care | Advocating; Following-up |

| Soft skills in dealing with clinician prescribers | Framing of recommendations; Building trusting relationships; Developing creative communication approaches; Demonstrating a positive and helpful attitude; Communicating in a clear and honest manner; Facilitating referrals |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tait, P.; Chakraborty, A.; Tieman, J. The Roles and Responsibilities of Community Pharmacists Supporting Older People with Palliative Care Needs: A Rapid Review of the Literature. Pharmacy 2020, 8, 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy8030143

Tait P, Chakraborty A, Tieman J. The Roles and Responsibilities of Community Pharmacists Supporting Older People with Palliative Care Needs: A Rapid Review of the Literature. Pharmacy. 2020; 8(3):143. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy8030143

Chicago/Turabian StyleTait, Paul, Amal Chakraborty, and Jennifer Tieman. 2020. "The Roles and Responsibilities of Community Pharmacists Supporting Older People with Palliative Care Needs: A Rapid Review of the Literature" Pharmacy 8, no. 3: 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy8030143

APA StyleTait, P., Chakraborty, A., & Tieman, J. (2020). The Roles and Responsibilities of Community Pharmacists Supporting Older People with Palliative Care Needs: A Rapid Review of the Literature. Pharmacy, 8(3), 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy8030143