Regulation of Food Supplements and Pharmacists’ Responsibility in Professional Practice: A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

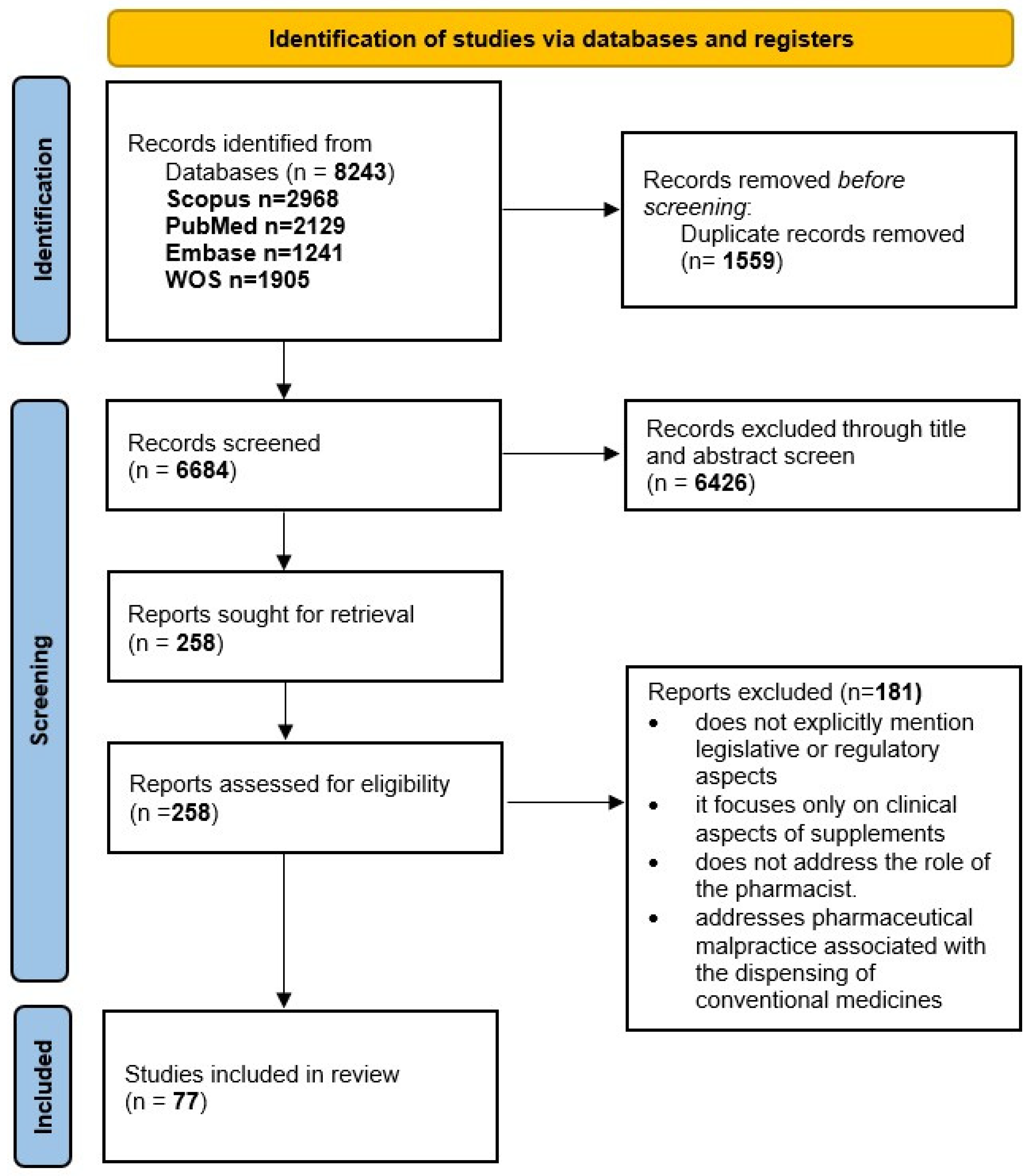

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Pharmacist Responsibility and Malpractice

3.1.1. Pharmacist Responsibility

3.1.2. Statistics at the Jurisdiction Level on Cases of Medical and Pharmaceutical Malpractice

3.2. Food Supplement Regulation

3.3. Consumer Safety

3.3.1. Consumer Safety from the Perspective of Product Quality

3.3.2. Consumer Safety in the Context of Online Marketing

3.4. Health Claims

3.5. Pharmacist Knowledge

4. Discussion

Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HPDT | Health Practitioners Disciplinary Tribunal |

| SAHPRA | South African Health Products Regulatory Authority |

| US | United States |

| EU | European Union |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| FTC | Federal Trade Commission |

| CFSAN | Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition |

| DSHEA | Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act |

| NMPA | National Medical Products Administration |

| NHPs | natural health products |

| GMPs | Good Manufacturing Practices |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| PFs | probiotic foods |

| PDSs | probiotic dietary supplements |

| LBPs | live biotherapeutic products |

| HMPs | herbal medicinal products |

| EC | European Commission |

| EMA | European Medicines Agency |

| EFSA | European Food Safety Authority |

| RDA | recommended daily allowance |

| OTC | over-the-counter medicines |

References

- Enioutina, E.Y.; Job, K.M.; Krepkova, L.V.; Reed, M.D.; Sherwin, C.M. How Can We Improve the Safe Use of Herbal Medicine and Other Natural Products? A Clinical Pharmacologist Mission. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020, 13, 935–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, M.; Khoshkhat, P.; Chamani, M.; Shahsavari, S.; Dorkoosh, F.A.; Rajabi, A.; Maniruzzaman, M.; Nokhodchi, A. In-Depth Multidisciplinary Review of the Usage, Manufacturing, Regulations & Market of Dietary Supplements. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2022, 67, 102985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapik, J.J.; Trone, D.W.; Steelman, R.A.; Farina, E.K.; Lieberman, H.R. Adverse Effects Associated with Multiple Categories of Dietary Supplements: The Military Dietary Supplement Use Study. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2022, 122, 1851–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuentes, J.B.; Amidžić, M.; Banović, J.; Torović, L. Internet Marketing of Dietary Supplements for Improving Memory and Cognitive Abilities. PharmaNutrition 2024, 27, 100379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathmann, A.M.; Seifert, R. Vitamin A-Containing Dietary Supplements from German and US Online Pharmacies: Market and Risk Assessment. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2024, 397, 6803–6820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djaoudene, O.; Romano, A.; Bradai, Y.D.; Zebiri, F.; Ouchene, A.; Yousfi, Y.; Amrane-Abider, M.; Sahraoui-Remini, Y.; Madani, K. A Global Overview of Dietary Supplements: Regulation, Market Trends, Usage during the COVID-19 Pandemic, and Health Effects. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rucklidge, J.J.; Shaw, I.C. Are Over-the-Counter Fish Oil Supplements Safe, Effective and Accurate with Labelling? Analysis of 10 New Zealand Fish Oil Supplements. N. Z. Med. J. 2020, 133, 52–62. [Google Scholar]

- The European Parliament and the Council of the European Union. Directive 2002/46/EC of The European Parliament and of The Council of 10 June 2002 on the Approximation of the Laws of the Member States Relating to Food Supplements. Official Journal of the European Communities. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2002/46/oj/eng (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Thakkar, S.; Anklam, E.; Xu, A.; Ulberth, F.; Li, J.; Li, B.; Hugas, M.; Sarma, N.; Crerar, S.; Swift, S.; et al. Regulatory Landscape of Dietary Supplements and Herbal Medicines from a Global Perspective. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2020, 114, 104647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sfodera, F.; Mattiacci, A.; Nosi, C.; Mingo, I. Social Networks Feed the Food Supplements Shadow Market. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 1531–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The European Parliament and the Council of the European Union. Directive 2011/62/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 8 June 2011. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32011L0062 (accessed on 18 January 2026).

- The European Commission Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2024/1701 of 11 March 2024. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:L_202401701&qid=1768766113098 (accessed on 18 January 2026).

- The European Council of the European Union. Pharma Package. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/pharma-pack/ (accessed on 18 January 2026).

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. Theory Pract. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bîrsanu, S.E.; Banu, O.G.; Nanu, C.A. Assessing Legal Responsibility in Romanian Pharmaceutical Practice. Farmacia 2022, 70, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patryn, R.; Drozd, M. Professional Responsibility of the Pharmacist in the Polish Legal System. Acta Pol. Pharm.-Drug Res. 2022, 79, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostrowska, M.; Drozd, M.; Patryn, R.; Zagaja, A. Prescriptions as Quality Indicators of Pharmaceutical Services in Polish Community Pharmacies. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bondarenko, O.S.; Reznik, O.; Dumchikov, M.O.; Horobets, N.S. Features of Criminal Liability of a Medical Professional for Failure to Perform or Improper Performance of Their Professional Duties in Ukraine. Wiad. Lek. 2020, 73, 2549–2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berzin, P.; Demchenko, I.; Berzina, A. The Problems of Criminal Liability of Pharmaceutical Employees in the Context of Certain Forms of Collaborative Activities. Wiad. Lek. 2023, 76, 1681–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellack, N.; Maimin, J.; Hoffmann, D.; Kriel, M.; Moodley, S.; Padayachee, N. The Impact of Unprofessional Behaviour on Patient Safety in South Africa: Two Cautionary Tales. S. Afr. Pharm. J. 2024, 91, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schupbach, J.; Kaisler, M.; Moore, G.; Sandefur, B. Physician and Pharmacist Liability: Medicolegal Cases That Are Tough Pills to Swallow. Clin. Pract. Cases Emerg. Med. 2021, 2, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parliament of Romania. Law No. 95/2006 on Healthcare Reform. Available online: https://edirect.e-guvernare.ro/Uploads/Legi/36270/Legea%20nr.%2095_2006%20privind%20reforma%20%C3%AEn%20domeniul%20s%C4%83n%C4%83t%C4%83%C5%A3ii_actualizare%2001.01.2024.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Parliament of Romania. Law No. 266/2008 (Pharmacy Law). Available online: https://www.anm.ro/_/LEGI%20ORDONANTE/LEGEA%20farmaciei%20266%20din%202008%20republicata%20actualizata%20la%2023%20aug%202018.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Ministry of Health. The Rules of Good Pharmaceutical Practice from 03.02.2010 as Approved by Ministry of Health’s Order No. 75/2010. Available online: https://www.colegfarm.ro/userfiles/file/OMS%2075_2010%20_RBPF.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Romanian College of Pharmacists. The Pharmacist’s Code of Conduct. Available online: https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocumentAfis/109599 (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Wang, Y.; Ram, S.; Scahill, S. Risk Identification and Prediction of Complaints and Misconduct against Health Practitioners: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2024, 36, mzad114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foong-Reichert, A.-L.; Fung, A.; Carter, C.A.; Grindrod, K.A.; Houle, S.K.D. Characteristics, Predictors and Reasons for Regulatory Body Disciplinary Action in Health Care: A Scoping Review. J. Med. Regul. 2021, 107, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millbank, J. Serious Misconduct of Health Professionals in Disciplinary Tribunals under the National Law 2010–17. Aust. Health Rev. 2020, 44, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taouk, Y.; Bismark, M.; Hattingh, H.L. Pharmacists Subject to Complaints: A National Study of Pharmacists Reported to Health Regulators in Australia. J. Pharm. Pract. Res. 2020, 50, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surgenor, L.J.; Diesfeld, K.; Kersey, K.; Kelly, O.; Rychert, M. Fifteen Years On: What Patterns Continue to Emerge from New Zealand’s Health Practitioners Disciplinary Tribunal? J. Law Med. 2020, 28, 165–178. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Ram, S.; Scahill, S. Characteristics and Risk Factors of Pharmacist Misconduct in New Zealand: A Retrospective Nationwide Analysis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foong-Reichert, A.-L.; Grindrod, K.A.; Edwards, D.J.; Austin, Z.; Houle, S.K.D. Pharmacist Disciplinary Action: What Do Pharmacists Get in Trouble For? Healthc. Policy 2023, 18, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, C.T. Factors Associated with Severity of Sanctions among Pharmacy Professionals Facing Disciplinary Proceedings. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2021, 17, 638–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, C.T.; Thaci, J.; Saadalla, G.; Mohamed, N.; Ismail, M.M.; Gossel, T.; Attopley, M. Disciplinary Action Against UK Health Professionals for Sexual Misconduct: A Matter of Reputational Damage or Public Safety? J. Med. Regul. 2021, 107, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshatti, F.A.; AlMubarak, S.H. The Prevalence of Medical Violation Claims and Associated Predictors at the Eastern Province in Saudi Arabia: A Logistic Regression Analysis. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2022, 85, 102300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlMubarak, S.H.; Alshatti, F.A. The Government as Plaintiff: An Analysis of Medical Litigation Against Healthcare Providers in the Eastern Province of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. J. Patient Saf. 2023, 19, e31–e37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Food and Drug Administration. Dietary Supplements Guidance Documents & Regulatory Information. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/guidance-documents-regulatory-information-topic-food-and-dietary-supplements/dietary-supplements-guidance-documents-regulatory-information (accessed on 18 January 2026).

- Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress to Amend the Food Safety Law of the People’s Republic of China China’s Food Safety Law. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faolex/results/details/en/c/LEX-FAOC154228 (accessed on 18 January 2026).

- Consumer Affairs Agency Foods with Function Claims Regulation in Japan. Available online: https://www.caa.go.jp/en/law/ (accessed on 18 January 2026).

- Government of Mexico COFEPRIS Mexico. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/cofepris (accessed on 14 January 2026).

- Government of Canada Food and Drug Act. Available online: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/F-27/page-1.html#h-234002 (accessed on 14 January 2026).

- Australian Government. The Therapeutic Goods Act. Available online: https://www.tga.gov.au/resources/legislation/therapeutic-goods-act-1989 (accessed on 18 January 2026).

- MEDSAFE. Dietary Supplements Regulation in New Zealand. Available online: https://www.medsafe.govt.nz/regulatory/dietarysupplements/regulation.asp (accessed on 18 January 2026).

- Tutelyan, V.A.; Sukhanov, B.P.; Kochetkova, A.A.; Sheveleva, S.A.; Smirnova, E.A. Russian Regulations on Nutraceuticals, Functional Foods, and Foods for Special Dietary Uses. In Nutraceutical and Functional Food Regulations in the United States and Around the World; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 399–416. [Google Scholar]

- Tallon, M.J.; Kalman, D.S. The Regulatory Challenges of Placing Dietary Ingredients on the European and US Market. J. Diet. Suppl. 2025, 22, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, T.C.; Koturbash, I. DSHEA 1994–Celebrating 30 Years of Dietary Supplement Regulation in the United States. J. Diet. Suppl. 2025, 22, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilia, A.R.; do Céu Costa, M. Medicinal Plants and Their Preparations in the European Market: Why Has the Harmonization Failed? The Cases of St. John’s Wort, Valerian, Ginkgo, Ginseng, and Green Tea. Phytomedicine 2021, 81, 153421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menal-Puey, S.; Marques-Lopes, I. Regulatory Framework of Fortified Foods and Dietary Supplements for Athletes: An Interpretive Approach. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, R.L. Current Regulatory Guidelines and Resources to Support Research of Dietary Supplements in the United States. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abubakar, U.; Tangiisuran, B. Knowledge and Practices of Community Pharmacists towards Non-Prescription Dispensing of Antibiotics in Northern Nigeria. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2020, 42, 756–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, H.; Abraham, E.J.; Mulligan, J.; Zhou, Y.; Montoya, M.; Willig, J.; Chen, B.K.; Wang, C.K.; Wang, L.S.; Dong, A.; et al. Label Compliance for Ingredient Verification: Regulations, Approaches, and Trends for Testing Botanical Products Marketed for “Immune Health” in the United States. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 2441–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez Díaz, L.; Fernández-Ruiz, V.; Cámara, M. The Frontier between Nutrition and Pharma: The International Regulatory Framework of Functional Foods, Food Supplements and Nutraceuticals. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 1738–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashkov, V.M.; Soloviov, O.S.; Khmelnytska, O.A. Legal Regulation of the Circulation of Dietary Food and Dietary Supplements in EU Countries. Exp. Ger. 2025, 77, 2546–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, P.; Jung-Cook, H.; Ruiz-Sánchez, E.; Rojas-Tomé, I.S.; Rojas, C.; López-Ramírez, A.M.; Reséndiz-Albor, A.A. Historical Aspects of Herbal Use and Comparison of Current Regulations of Herbal Products between Mexico, Canada and the United States of America. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zovi, A.; Vitiello, A.; Sabbatucci, M.; Musazzi, U.M.; Sagratini, G.; Cifani, C.; Vittori, S. Food Supplements Marketed Worldwide: A Comparative Analysis Between the European and the U.S. Regulatory Frameworks. J. Diet. Suppl. 2025, 22, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, J.; Saldanha, L.; Bailen, R.; Durazzo, A.; Le Donne, C.; Piccinelli, R.; Andrews, K.; Pehrsson, P.; Gusev, P.; Calvillo, A.; et al. Commentary: An Impossible Dream? Integrating Dietary Supplement Label Databases: Needs, Challenges, next Steps. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2021, 102, 103882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dwyer, D.D.; Vegiraju, S. Navigating the Maze of Dietary Supplements. Top. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 35, 248–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, J.Y.; Luong, M. Evaluation of the Canadian Natural Health Product Regulatory Framework in Academic Research: A Scoping Review. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2020, 37, 101159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, J.Y.; Tahir, U.; Dhaliwal, S. Barriers, Knowledge, and Training Related to Pharmacists’ Counselling on Dietary and Herbal Supplements: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okoya, F.T.; Santoso, M.; Raffoul, A.; Atallah, M.A.; Bryn Austin, S. Weak Regulations Threaten the Safety of Consumers from Harmful Weight-Loss Supplements Globally: Results from a Pilot Global Policy Scan. Public Health Nutr. 2023, 26, 1917–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spacova, I.; Binda, S.; ter Haar, J.A.; Henoud, S.; Legrain-Raspaud, S.; Dekker, J.; Espadaler-Mazo, J.; Langella, P.; Martín, R.; Pane, M.; et al. Comparing Technology and Regulatory Landscape of Probiotics as Food, Dietary Supplements and Live Biotherapeutics. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1272754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, V.; Velumani, D.; Lin, Y.-C.; Haye, A. A Comprehensive Review of Probiotic Claims Regulations: Updates from Asia-Pacific, United States, and Europe. PharmaNutrition 2024, 30, 100423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Simone, C. The Authenticity of Probiotic Foods and Dietary Supplements: Facts and Reflections from a Court Case. CYTA-J. Food 2022, 20, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganson, K.T.; Sinicropi, E.; Nagata, J.M. Assessing Canadian Regulation of Muscle-Building Supplements: Identifying Gaps and Recommendations for Improvement to Protect the Health and Well-Being of Young People. Perform. Enhanc. Health 2023, 11, 100255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozda, R. Regulatory Issues of Voluntary Certification of Food Supplements in Russia. Ther. Innov. Regul. Sci. 2020, 54, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, J.Y.; Kim, M.; Suri, A. Exploration of Facilitators and Barriers to the Regulatory Frameworks of Dietary and Herbal Supplements: A Scoping Review. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2022, 15, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wierzejska, R.E. Dietary Supplements—For Whom? The Current State of Knowledge about the Health Effects of Selected Supplement Use. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charen, E.; Harbord, N. Toxicity of Herbs, Vitamins, and Supplements. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2020, 27, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitz, S.M.; Lopez, H.L.; Mackay, D.; Nguyen, H.; Miller, P.E. Serious Adverse Events Reported with Dietary Supplement Use in the United States: A 2.5 Year Experience. J. Diet. Suppl. 2020, 17, 227–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piattoly, T.J. Dietary Supplement Safety: Risk vs. Reward for Athletes. Oper. Tech. Sports Med. 2022, 30, 150891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yéléhé-Okouma, M.; Pape, E.; Humbertjean, L.; Evrard, M.; El Osta, R.; Petitpain, N.; Gillet, P.; El Balkhi, S.; Scala-Bertola, J. Drug Adulteration of Sexual Enhancement Supplements: A Worldwide Insidious Public Health Threat. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2021, 35, 792–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensa, M.; Vovk, I.; Glavnik, V. Resveratrol Food Supplement Products and the Challenges of Accurate Label Information to Ensure Food Safety for Consumers. Nutrients 2023, 15, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inthong, C.; Lerkiatbundit, S.; Mekruksavanich, S.; Hanvoravongchai, P. Assessing Dietary Supplement Misinformation on Popular Thai E-Marketplaces: A Cross-Sectional Content Analysis. Thai J. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 48, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutorova, N.O.; Pashkov, V.M.; Soloviov, O.S. Illegal Internet Pharmacies As A Threat To Public Health In Europe. Wiad. Lek. 2021, 74, 2169–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevallier, H.; Herpin, F.; Kergosien, H.; Ventura, G.; Allaert, F.A. A Graded Approach for Evaluating Health Claims about Plant-Based Food Supplements: Application of a Case Study Methodology. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, C.M.; Oliver, S.P.; De La Quintana, A. Dietary Supplements’ Endorsements. A Content Analysis of Claims and Appeals on Spanish Radio. Commun. Soc. 2020, 33, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muela-Molina, C.; Perelló-Oliver, S.; García-Arranz, A. Endorsers’ Presence in Regulation and Endorsements in Dietary Supplements’ Advertising on Spanish Radio. Health Policy 2020, 124, 902–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muela-Molina, C.; Perelló-Oliver, S.; García-Arranz, A. Health-Related Claims in Food Supplements Endorsements: A Content Analysis from the Perspective of EU Regulation. Public Health 2021, 190, 168–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muela-Molina, C.; Perelló-Oliver, S.; García-Arranz, A. False and Misleading Health-Related Claims in Food Supplements on Spanish Radio: An Analysis from a European Regulatory Framework. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 5156–5165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wierzejska, R.E.; Wiosetek-Reske, A.; Siuba-Strzelińska, M.; Wojda, B. Health-Related Content of TV and Radio Advertising of Dietary Supplements—Analysis of Legal Aspects after Introduction of Self-Regulation for Advertising of These Products in Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, S.V.; Granger, B.; Bauer, K.; Roberto, C.A. A Content Analysis of Marketing on the Packages of Dietary Supplements for Weight Loss and Muscle Building. Prev. Med. Rep. 2021, 23, 101504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elvir Lazo, O.L.; White, P.F.; Lee, C.; Cruz Eng, H.; Matin, J.M.; Lin, C.; Del Cid, F.; Yumul, R. Use of Herbal Medication in the Perioperative Period: Potential Adverse Drug Interactions. J. Clin. Anesth. 2024, 95, 111473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman Popattia, A.; La Caze, A. An Ethical Framework for the Responsibilities of Pharmacists When Selling Complementary Medicines. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2021, 17, 850–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.A.; Harnett, J.E.; Ung, C.O.L.; Chaar, B. Impact of Up-Scheduling Medicines on Pharmacy Personnel, Using Codeine as an Example, with Possible Adaption to Complementary Medicines: A Scoping Review. Pharmacy 2020, 8, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altamimi, M.; Hamdan, M.; Badrasawi, M.; Allahham, S. Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices Related to Dietary Supplements among a Group of Palestinian Pharmacists. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 2021, 21, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshahrani, S.M. Assessment of Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practice of Community Pharmacists Regarding Weight Reduction Agents and Supplements in Aseer Region, Saudi Arabia. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2020, 13, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, K.C.; Keshock, M.; Ganesh, R.; Sigmund, A.; Kashiwagi, D.; Devarajan, J.; Grant, P.J.; Urman, R.D.; Mauck, K.F. Preoperative Management of Surgical Patients Using Dietary Supplements. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2021, 96, 1342–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlengwa, N.; Muller, C.J.F.; Basson, A.K.; Bowles, S.; Louw, J.; Awortwe, C. Herbal Supplements Interactions with Oral Oestrogen-based Contraceptive Metabolism and Transport. Phytother. Res. 2020, 34, 1519–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaston, T.E.; Mendrick, D.L.; Paine, M.F.; Roe, A.L.; Yeung, C.K. “Natural” Is Not Synonymous with “Safe”: Toxicity of Natural Products Alone and in Combination with Pharmaceutical Agents. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2020, 113, 104642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huff, R.; Karpinska-Leydier, K.; Maddineni, G.; Begosh-Mayne, D. Rhabdomyolysis Risk: The Dangers of Tribulus Terrestris, an Over-the-Counter Supplement. Am. J. Case Rep. 2024, 25, e943492-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, E.K.; Perez-Sanchez, A.; Katta, R. Risks of Skin, Hair, and Nail Supplements. Dermatol. Pract. Concept. 2020, 10, e2020089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhao, M.; Zhao, L. The Drug Interaction Potential of Berberine Hydrochloride When Co-Administered with Simvastatin, Fenofibrate, Gemfibrozil, Metformin, Glimepiride, Nateglinide, Pioglitazone and Sitagliptin in Beagles. Arab. J. Chem. 2022, 15, 103562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnichsen, M.; Stoklosa, T.; Bowen, D.; Majumdar, A. Safety First, a Harmful Interaction between Rivaroxaban and Berberine. Intern. Med. J. 2022, 52, 887–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country | Name and Classification | Regulatory Agency | Legislation | Pre-Market Approval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| European Union | Food supplement, regulated as Food products | EC, National authorities | Directive 2002/46/EC Member States legislation | Notification required, depending on Member State legislation |

| United States | Dietary supplement, regulated as food products | FDA, FTC | DSHEA (Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act) | Not required, responsibility rests on manufacturer |

| China | Health food, regulated as special foods | NMPA (National Medical Products Administration) | Chinese Food Safety Law | Notification/Registration (health claims) |

| Japan | Foods with function claims, regulated as foods | MHLW (Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare) CAA (Consumer Affairs Agency) for Supplements | Food Sanitation Act | Notification required, responsibility rests on manufacturer |

| Mexico | Food supplement, regulated as foods | Ministry of Health The Federal Commission for Protection against health risks (COFEPRIS) | General Health Law | Not required, responsibility rests on manufacturer |

| Canada | Natural health product, regulated in a separate category | HC (Health Canada), NNHPD (Natural and Non-Prescription Health Products Directorate) | Food and Drugs Act and Regulations Natural Health Products Regulations (NHPR) | Yes, Product License, 8-digit Natural Product Number (NPN) on the label Site License—demonstrate safety and efficacy |

| Australia | Complementary medicines | TGA (Therapeutic Goods Administration), Territorial regulatory authorities | Therapeutic Goods Act | Notification/Registration |

| New Zealand | Dietary supplement, regulated as food products | MEDSAFE (New Zealand Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Authority) | Dietary Supplements Regulations | Not required |

| Russian Federation | Dietary foods/Biologically active food supplements Regulated as food products | Russian Federal Service for Surveillance on Consumer Rights Protection and Human Wellbeing | Russian Federal Law No. 29-FZ on the Quality and Safety of Food | State registration required, responsibility rests on manufacturer |

| Potential Causes | Product Category | Type of Adulteration/Contamination, Mechanism | Safety Concern |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adulteration (pharmaceutical/economic) | Sexual performance enhancement | PDE5-i, hypoglycemic agents | Hepatic, neurological, cardiovascular toxicity |

| Weight loss | Sibutramine, laxatives | Cardiovascular, gastrointestinal symptoms | |

| Muscle enhancing | Amphetamines, antidepressants | Hepatic, cardiovascular | |

| VSL#3® probiotic | Economic substitution | Lack of efficacy | |

| Product composition | Fish oil | Discrepancy between claimed health benefits, dosage, and actual efficacy | Lack of efficacy |

| Resveratrol | Composition non-compliance (lower amounts than marketed/exceeding maximum allowable dose) | Potential health risks | |

| Contamination of raw materials/finished product | Contaminated products | dust, pollen and toxic heavy metals (e.g., lead and mercury) | Severe adverse effects, including poisoning |

| Allergic reactions | Products with allergenic ingredients | Presence of allergens in the product | Severe allergic reactions |

| Interactions with conventional medications | - | May affect absorption, metabolism, or pharmacodynamics | Precipitates adverse reactions |

| Excessive consumption | Chinese herbal medicines | aristolochic acid | Nephrotoxicity |

| Soladek | Elevated concentrations of vitamin D | Vitamin D toxicity | |

| Products containing amygdalin | Amygdalin | Fatal cyanide poisoning |

| Study | Country | Context | Main Issue Identified |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chevallier et al., 2021 [75] | EU | Health claims regulations for plant-based food supplements | Currently excluded from the approved list of health claims, pending authorization |

| Molina et al., 2020 [76] | Spain | Radio broadcasts (2017)—Analysis of food supplement endorsements | Heavy reliance on endorsers (most prevalent—anonymous spokespeople, followed by celebrities) Explicit claims are more prevalent than implicit claims |

| Muela-Molina et al., 2020 [77] | Spain | Radio broadcasts (2017)—Analysis of food supplement endorsements | 40% of radio spots feature endorsers prohibited by law |

| Muela-Molina et al., 2021 [78] | Spain | Radio broadcasts (2017)—Analysis of food supplement endorsements | Significant noncompliance with EU regulations |

| Muela-Molina et al., 2021 [79] | Spain | Radio broadcasts (2017)—Analysis of food supplement endorsements | Extensive use of unauthorized health claims, use of illness as a persuasive strategy, promotion of unsubstantiated benefits |

| Wierzejska et al., 2022 [80] | Poland | TV and Radio advertising of food supplements (9–15 march 2020) | Nearly 30% of advertised supplements made unsubstantiated effectiveness claims |

| Hua et al., 2021 [81] | United States | Health claims featured on food supplements promoted for weight loss and muscle building (Boston 2013) | The study identified unsupported health claims |

| Wierzejska et al., 2021 [67] | Poland, worldwide | Health effects, risks of selected food supplements | Unproven efficacy |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Niculaș, C.I.; Blaj, S.B.; Cherecheș, M.C.; Miron, R.; Valea, D.C.; Muntean, D.L. Regulation of Food Supplements and Pharmacists’ Responsibility in Professional Practice: A Review. Pharmacy 2026, 14, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy14010025

Niculaș CI, Blaj SB, Cherecheș MC, Miron R, Valea DC, Muntean DL. Regulation of Food Supplements and Pharmacists’ Responsibility in Professional Practice: A Review. Pharmacy. 2026; 14(1):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy14010025

Chicago/Turabian StyleNiculaș, Cristina Ioana, Sonia Bianca Blaj, Marius Călin Cherecheș, Raul Miron, Daniela Cristina Valea, and Daniela Lucia Muntean. 2026. "Regulation of Food Supplements and Pharmacists’ Responsibility in Professional Practice: A Review" Pharmacy 14, no. 1: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy14010025

APA StyleNiculaș, C. I., Blaj, S. B., Cherecheș, M. C., Miron, R., Valea, D. C., & Muntean, D. L. (2026). Regulation of Food Supplements and Pharmacists’ Responsibility in Professional Practice: A Review. Pharmacy, 14(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy14010025