Abstract

Nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease (NTM-PD) results from opportunistic lung infections by mycobacteria other than Mycobacterium tuberculosis or Mycobacterium leprae species. Similar to many other countries, the incidence of NTM-PD in the United Kingdom (UK) is on the rise for reasons that are yet to be determined. Despite guidelines established by the American Thoracic Society (ATS), the Infectious Diseases Society of America, and the British Thoracic Society, NTM-PD diagnosis and management remain a significant clinical challenge. In this review article, we comprehensively discuss key challenges in NTM-PD diagnosis and management, focusing on the UK healthcare setting. We also propose countermeasures to overcome these challenges and improve the detection and treatment of patients with NTM-PD.

1. Introduction

Nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease (NTM-PD) is a group of disorders caused by bacteria belonging to the genus Mycobacterium, excluding the Mycobacterium tuberculosis and M. leprae species. Nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) are found in the environment, and their lipid-rich cell walls render them resistant to unfavourable conditions such as extremes of temperature and pH, as well as to antibacterial agents [1,2]. Although more than 180 species of NTM have been characterised, only a few species cause pulmonary disease. M. avium complex (MAC), M. abscessus, M. kansasii, and M. xenopi are the most common causative agents of NTM-PD in the United Kingdom (UK) [3,4]. NTM are broadly divided into slow-growing mycobacteria (e.g., M. xenopi, M. avium, and M. kansasii) and rapidly growing mycobacteria (e.g., M. abscessus and M. chelonae) [1].

The estimated prevalence of NTM-PD varies substantially within and among countries [5,6]. Variations in NTM case definitions and nonconformance to disease reporting guidelines can complicate estimations of NTM-PD prevalence [3,6,7]. Nevertheless, rates of NTM-PD appear to be highest in East Asia and lower in Europe and the United States [5,6,8]. There has been an increasing trend in NTM infection and NTM-PD reported in many countries, including the UK [5,6,8]. This increase in prevalence is particularly apparent in elderly populations [6,9]. In the UK, reliable local and national NTM-PD epidemiological data are currently lacking [10,11]. However, the positivity rate of NTM cultures in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland increased eight-fold between 1995 and 2012, from 0.9 to 7.6 per 100,000 [10,12,13]. Estimates of NTM-PD prevalence in the UK in 2016 varied from 6.4 to 16 per 100,000 [11,14,15]. The reasons behind the increasing reported prevalence of NTM-PD remain unknown, although greater awareness of the disease, an ageing population, a declining incidence of tuberculosis (TB), and improvements in diagnostic tools may be contributing factors [11].

The most well-established risk factors for NTM-PD include the presence of pre-existing lung diseases (such as bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis [CF], chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], asthma, and interstitial lung disease [ILD]), a previous history of tuberculosis, and comorbidities such as rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular disease, and chronic kidney disease [16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. Treatment with corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive agents, as well as tumour necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors for rheumatoid arthritis, are also risk factors [22]. Other contributions to increased risk include environmental (e.g., atmospheric humidity, exposure to soil) [23,24], immunological (e.g., abnormalities in the interferon-gamma/interleukin-12 pathway) [25,26,27], and genetic (e.g., mutations in CF transmembrane conductance regulator [CFTR]) factors [28,29,30]. Furthermore, patient factors including age, alcohol consumption, smoking, and gender may also affect the occurrence of NTM-PD [31,32]. Therefore, healthcare professionals (HCPs) need to maintain a high index of suspicion for NTM-PD to prompt early investigation in susceptible patient groups in order to prevent delays in diagnosis and reduce the risk of disease progression.

2. Challenges of NTM-PD Diagnosis

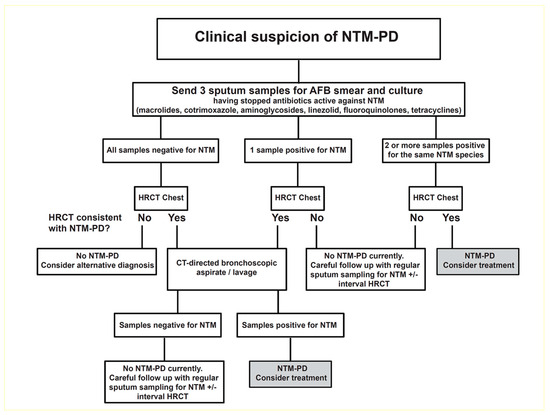

NTM-PD diagnosis is based on clinical, microbiological, and radiological findings as described in the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines originally published in 2007 and in the updated international ATS/European Respiratory Society (ERS)/European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID)/IDSA guidelines published in 2020 [33,34]. These criteria have also been adopted by the British Thoracic Society (BTS), which recommends a combination of acid-fast bacilli culture tests and computed tomography (CT) scans before considering a diagnosis of NTM-PD and the initiation of treatment (Figure 1) [12].

Figure 1.

An algorithm for the investigation of suspected cases of NTM-PD. Reproduced from British Thoracic Society guidelines for the management of nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease (NTM-PD), Charles S Haworth et al., 72; iii1–ii64, 2017 with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd. [12,35]. AFB = acid-fast bacilli; CT = computed tomography; HR = high-resolution; NTM = nontuberculous mycobacterial; PD = pulmonary disease.

2.1. Screening Guidelines and Diagnostic Testing Procedures

The number of confirmed diagnoses of NTM-PD is likely to be underestimated due to nonadherence to NTM-PD screening guidelines [2,36]. For example, both the ERS and BTS bronchiectasis guidelines recommend testing for NTM in patients with bronchiectasis [37,38,39]. However, among patients in the UK enrolled in the EMBARC registry, testing for NTM was only performed in 17.2% of cases [37]. Geographical variations in the microbiological diagnosis of NTM-PD in the UK have also been reported, which may reflect either true differences in prevalence or that microbiological testing varies in different laboratories [10,11].

2.2. Clinical Awareness

Despite the recent improvements in the awareness of NTM-PD in the UK [12,15,40], further advances in the clinical awareness and understanding of NTM are warranted to improve NTM-PD diagnosis and avoid diagnostic delays. Significant efforts are required to raise awareness of NTM-PD more broadly so that HCPs working in primary care and non-respiratory specialists in secondary care consider the diagnosis in high-risk patients and those without a history of pre-existing lung disease who present with a chronic cough and non-specific constitutional symptoms. There is also a need to raise awareness of NTM-PD amongst respiratory specialists so that screening is undertaken in patients before commencing long-term treatment with macrolides (e.g., those with COPD and bronchiectasis) [10,12]. Routine screening for NTM should also be considered in other susceptible patient groups, including patients with severe disease, recurrent exacerbations, those receiving high-dose inhaled corticosteroids or other immunosuppressives, as well as those with bronchiectasis, CF, COPD, or ILD.

2.3. Microbiology

According to UK and international guidelines, at least three respiratory samples should be sent for mycobacterial culture in suspected NTM-PD cases [10,12]. The BTS guidelines recommend sputum induction in individuals with suspected NTM-PD who are unable to spontaneously produce sputum and when CT-directed bronchial washings are not suitable [12]. In primary care, general practitioners need to specifically request that sputum samples from patients presenting with risk factors for NTM-PD be sent for both mycobacterial culture and routine culture.

Currently, automated liquid culture technologies are the gold standard for mycobacterial culture [1,41]. The accurate identification of mycobacterial species in individuals with suspected NTM-PD is critical, as different NTM species often require treatment with different regimens [1,42]. With the rapid decrease in sequencing costs over the last few years, gene sequencing and other molecular techniques have become the method of choice for the identification of mycobacterial species. Recently, Matsumoto et al. [43] developed a novel sequencing-based approach that can identify 175 NTM species based on 7547 genomic profiles, overcoming many of the limitations of previous molecular methods for NTM identification [44]. Moreover, matrix-assisted laser desorption–ionisation–time-of-flight mass spectrometry has emerged as a promising method for NTM identification, complementing molecular analyses [45]. It cannot, however, differentiate between the three subspecies of M. abscessus, which is essential, as each subspecies has a different drug resistance profile [46,47].

2.4. Radiology

According to the BTS guidelines, CT should be performed in all individuals reporting symptoms consistent with NTM-PD, particularly in patients with bronchiectasis [12,39,48]. Ideally, supine inspiratory volumetric contiguous and high-resolution scans with a 1 mm slice thickness should be acquired [12]. Despite the wide range of NTM-PD clinical symptoms, radiological evaluation typically reveals evidence of cavitation and/or nodular–bronchiectatic disease [49,50,51]. Traditionally, the fibrocavitary phenotype of NTM-PD has been observed more commonly in men with COPD, but it is being seen increasingly in women, presumably due to the increasing incidence of COPD in women [3,51]. The cavities can be large and thick-walled, but may also be small and thin-walled, often resembling TB or malignant lesions, making it difficult to differentiate these diseases [3]. In contrast to fibrocavitary NTM-PD, nodular–bronchiectatic NTM-PD is more frequent in patients with pre-existing bronchiectasis or no history of pre-existing lung disease. Typical radiological findings of nodular–bronchiectatic NTM-PD include bronchiectasis, tree-in-bud opacity, nodules, bronchial wall thickening, and mucus plugging. This nodular–bronchiectatic form in particular can be seen in a subgroup of older women with no pre-existing medical conditions. In this cohort, the disease is often confined to the lingula and middle lobe, with MAC usually being the causative organism [3,52]. While radiological evaluation plays a critical role in the diagnosis of NTM-PD, it is also essential for monitoring disease activity in people who are not on treatment and for evaluating the radiological response during and at the end of NTM-PD treatment [53].

3. Challenges of NTM-PD Management

3.1. Decision to Treat

Predictors of NTM-PD severity and mortality may help guide clinical decision making and identify patients who are more likely to benefit from treatment. These predictors include low body mass index (BMI), malnutrition, advanced age, immunosuppression (e.g., immunosuppressive therapy, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, and primary or secondary immunodeficiencies), clinical symptoms (e.g., fever, haemoptysis, respiratory failure, weight loss), the presence of cavitation, comorbidities, and positive sputum culture and/or bronchial washing sample. Biochemical indicators of severe NTM-PD include low serum levels of albumin, low lymphocyte or erythrocyte counts, and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate [54,55,56].

Comorbidities (including respiratory and cardiovascular diseases) present an increased risk for NTM-PD and are associated with worse NTM-PD outcomes; the management of such comorbidities should, therefore, be considered in treatment decisions for NTM-PD [12,22]. Given that many patients with NTM-PD may have comorbid conditions, the risk of drug interactions between the multidrug antibiotic regimens recommended to manage NTM-PD and treatments that patients may already be using for comorbid conditions must be considered. For example, macrolides are known to interact with digoxin and other antiarrhythmic drugs, as well as statins, which are used to treat cardiovascular disease [57,58]. Rifampicin-containing regimens can accelerate the metabolism of a wide variety of drugs, including corticosteroids, anticoagulants, sulphonylureas, and CFTR modulators [12]. With the prevalence of comorbidities and the likelihood of polypharmacy in patients with NTM-PD, treatment decisions can be complex. As noted, the incidence of NTM-PD is increasing most in older age groups [6,9], who are especially likely to have comorbidities requiring pharmacological intervention and are particularly challenging to manage [59]. Collaboration with pharmacists, given their knowledge of drug–drug interactions and adverse effects, can play a key role in the management of patients with NTM-PD [12,59,60]. The effects of the toxicities associated with NTM-PD treatment on any concomitant conditions should also be taken into account [12].

The clinical course of NTM-PD varies widely among patients. Despite the fact that NTM-PD can cause significant morbidity and mortality (3.6-fold increased risk of death), some patients recover without the need for treatment but may be at risk of subsequent relapse [52,61,62,63,64]. However, most patients with NTM-PD, especially those with bronchiectasis or other underlying lung diseases, require prolonged treatment (a minimum of 12 months after culture conversion) with a multidrug antibiotic regimen, which is often associated with significant toxicity [12,33,38,65]. The decision to initiate treatment takes a number of factors into account, including the mycobacterial species causing the disease, the susceptibility profile of the organism, the severity of symptoms and radiological findings, the patient’s fitness, the presence of comorbidities, and the goal of the intervention.

3.2. Drug Resistance

Macrolide antibiotics (e.g., clarithromycin and azithromycin) are included in current standard-of-care regimens in the treatment of M. avium-mediated pulmonary disease. Although relatively infrequent, macrolide resistance has been shown to limit treatment options and outcomes [12,34].

The most significant risk factor associated with the development of acquired macrolide resistance in M. avium is point mutations in rrl, the gene encoding 23S rRNA. Macrolide resistance is also common among NTM-PD patients infected with one of the three M. abscessus subspecies, as two subspecies (subsp. abscessus and subsp. bolletii) carry an inducible macrolide resistance gene (erm41) [1]. Under chronic exposure to rifamycin, M. kansasii may develop resistance to rifampicin-containing regimens; hence, rifamycin susceptibility should be tested in patients infected with M. kansasii [34].

The elimination of treatment-resistant NTM strains remains a major challenge for the treatment of refractory NTM-PD [2]. In patients infected with macrolide-resistant M. avium, macrolide-resistant M. abscessus, or rifamycin-resistant M. kansasii, treatment regimens should be guided by drug sensitivity testing and may include combinations of drugs such as amikacin, clofazimine, imipenem, tigecycline, co-trimoxazole, ciprofloxacin/moxifloxacin, linezolid, doxycycline/minocycline, rifabutin, isoniazid, ethambutol, and azithromycin [34]. Patients with macrolide-resistant or rifampicin-resistant NTM-PD may also benefit from surgery [12,66,67]. Other drug therapies that have been investigated include interferon-gamma and other immunotherapeutic agents, such as mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors, programmed cell death-1 (PD-1)/programmed cell death ligand-1 (PD-L1) inhibitors, and haem oxygenase-1 (HO-1) inhibitors. These have not been recommended for most patients due to the limited evidence of their benefits [12,65,68,69].

Due to the lack of curative therapies, high toxicities of current treatments, and lack of accurate predictors of treatment response, deciding which patients should be treated and which treatment regimens are the most appropriate for each patient remain the most critical challenges for the management of NTM-PD [1,2,3]. These factors highlight the urgent need for more effective and safer therapies, as well as indicators of disease severity and predictors of treatment response. The lack of large-cohort randomised controlled trials is a key factor hindering the development of effective and safe therapies for NTM-PD. Most studies assessing the safety and efficacy of treatments for NTM-PD are case reports, impairing the generalisability of the findings [10]. Although guidelines from the ATS/ERS/ESCMID/IDSA and the BTS provide treatment recommendations for the most common NTM species [12,33], it is only recently that consensus recommendations have been published for the less common NTM bacteria that cause pulmonary disease [70].

4. Consensus on NTM-PD Management

There are national and international management guidelines for NTM-PD, and even though these guidelines are widely adopted in the UK, treatment outcomes remain unsatisfactory and response rates are low. The lack of established referral pathways from primary to secondary care and from secondary care to NTM-PD specialists along with regional variations in diagnostic testing can lead to significant delays in NTM-PD diagnosis, contributing to the poor NTM-PD treatment outcomes. Additionally, regional variations exist in the care provided to patients diagnosed with NTM-PD [10]. Despite recent evidence of person-to-person transmission of NTM in patients with CF [71,72], NTM-PD is widely believed to be a non-transmittable disease. Nevertheless, the route of infection remains unclear, impeding the establishment of effective infection control measure guidelines in this area.

The complexity of NTM-PD diagnosis and management calls for the establishment of specialised regional multidisciplinary NTM-PD centres. Currently, in the best-case scenario, patients with NTM-PD are under the care of HCPs with experience in TB, bronchiectasis, infectious diseases, or respiratory diseases (e.g., COPD). However, there is a lack of education and appropriate training in the diagnosis and management of NTM-PD even among clinicians looking after patients with COPD, evident in the fact that referrals from primary care tend to increase after education sessions. Until specialised NTM-PD multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) are established, constant education and sharing of experience among HCPs is key to minimising regional variations in the management of NTM-PD in the UK [10].

Although no treatment is provided to most NTM-PD patients with mild symptoms, long-term follow-up is still recommended for all patients [12]. The severity of respiratory symptoms, presence and severity of underlying conditions, the extent of lung damage, patient engagement, NTM pathogenicity, and drug resistance profile are all factors that determine whether treatment for NTM-PD should be initiated [10]. The treatment of NTM-PD is complex and varies based on the particular NTM species, making the accurate identification of the NTM species essential [42]. The BTS guideline includes recommendations for treating the most common NTM species causing NTM-PD: MAC, M. kansasii, M. malmoense, M. xenopi, and M. abscessus (Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5). Combinations of at least three antibiotic drugs are usually recommended, with a minimum duration of treatment continuing for at least 12 months after culture conversion [12]. The standard of care for patients infected with MAC, the most common cause of NTM-PD, is the combination of macrolides, rifampicin, and ethambutol given for at least 12 months after culture conversion. However, significant variations exist in the reported efficacy of this regimen. A recent meta-analysis of 16 studies involving 1462 patients with NTM-PD found that this combination provided poor treatment outcomes, with a culture conversion rate of only 60% [73]. Another study showed that almost half of the patients who initially responded to macrolide-containing regimens eventually relapsed [74]. Adult and post-pubescent children without CF, who are refractory to standard guideline-based treatment and remain culture positive for MAC after 6 months of treatment, are eligible to receive additional treatment with nebulised liposomal amikacin. This can be continued for 12 months after sputum culture conversion but should be stopped if culture conversion is not achieved after 6 months [75].

Table 1.

Suggested antibiotic regimens for adults with M. avium complex pulmonary disease [12].

Table 2.

Suggested antibiotic regimens for adults with M. kansasii pulmonary disease [12].

Table 3.

Suggested antibiotic regimens for adults with M. malmoense pulmonary disease [12].

Table 4.

Suggested antibiotic regimens for adults with M. xenopi pulmonary disease [12].

Table 5.

Suggested antibiotic regimens for adults with M. abscessus pulmonary disease [12].

The complexity of drug regimens is a significant challenge for many patients due to overlapping drug toxicity profiles and the potential for drug–drug interactions with medications taken for other underlying comorbidities. In situations where first-line drugs cannot be used due to drug resistance, intolerance or drug–drug interactions, alternative options must be identified. A number of emerging treatments have been identified as potential options for NTM-PD including bedaquiline, clofazimine, tetracycline derivatives (e.g., omadacycline), oxazolidinones (e.g., tedizolid), combining β-lactams with β-lactamase inhibitors (e.g., imipenem/cilastatin with relebactam, ceftazidime with avibactam, or meropenem with varborbactam) [76].

Regardless of treatment, patients with NTM-PD should be provided with education on their drug regimens, dosing schedules, advice on the need for adherence and guidance on the management of side effects whilst being closely monitored by NTM-PD specialists. Regular, in-person clinical evaluations are recommended, initially every two to four weeks (depending on the patient’s needs) and extending to intervals of up to 6 months for stable patients, which can be held via telephone consultations. During clinic visits, serial sputum cultures should also be performed. Patients undergoing treatment for NTM-PD should be monitored for renal function, anticipated poor response or delayed response, potential drug interactions, and treatment-related toxicities, such as gastrointestinal disorders, rash, tinnitus, optic neuritis, and hepatotoxicity—regular therapeutic drug monitoring should only be employed in patients showing signs or symptoms of toxicity (or who are at risk of toxicity) [7]. Importantly, patients receiving aminoglycosides should undergo frequent audiograms, as ototoxicity is a frequent and irreversible side effect of macrolides and aminoglycosides, occurring in up to one-third of NTM-PD patients treated with such regimens; if ototoxicity is suspected, treatment should be discontinued [53,65,77]. Some anti-NTM-PD antibiotics can cause serious adverse effects of cardiotoxicity (QTc prolongation) and hepatotoxicity; hence, electrocardiogram and liver function tests should be performed before treatment initiation (baseline), after 2 weeks of treatment and repeated intermittently every 3-6 months [65].

Patients with treatment-refractory disease (defined as failure to culture convert after 12 months of NTM treatment), recurrence of disease (two positive mycobacterial cultures following culture conversion), drug-resistant disease prior to treatment, and those who may benefit from surgery require particularly careful and expert evaluation. The BTS guideline recommends lung resection surgery as an option for patients with NTM-PD with localised areas of severe disease [12].

Given the complexity of NTM-PD, an MDT management approach should be considered to ensure access to all specialities required for holistic NTM-PD management (Table 6) [78]. Specifically, NTM-PD MDTs should include an expert clinician (disease diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring), specialist respiratory nurses (treatment and monitoring, patient wellbeing), a respiratory physiotherapist (airway clearance and exercise), a microbiologist (sputum conversion, treatment monitoring), a radiologist (radiological diagnosis and monitoring), a pharmacist (drug interactions, side effect management, introduction of new treatments, and therapeutic drug monitoring), a dietitian (as weight loss is a risk factor of severe NTM-PD), and a psychologist (psychological support and management of mental health conditions due to chronic illness). The establishment of continuing medical education and training programmes is critical to ensure that NTM-PD MDTs and allied HCPs maintain competence to provide the best care possible. The establishment of a clear referral pathway consensus from primary to secondary care and from secondary care to NTM-PD specialists is also urgently required [10].

Table 6.

Roles of the different MDT stakeholders in NTM-PD diagnosis and management.

The establishment of specialised regional centres that can support local NTM-PD services is particularly crucial for patients with (1) drug-resistant NTM (e.g., M. abscessus) requiring prolonged treatment, (2) cavitary NTM-PD requiring surgical evaluation, (3) persistent or refractory NTM infection, and (4) co-infection with other bacteria, viruses, or fungi. Local and national clinical networks are also required to facilitate direct communication among experts managing diseases associated with NTM (e.g., CF and TB units, bronchiectasis clinics). Regional and national MDT meetings should also take place regularly to share experiences and establish or amend local and national guidelines according to the needs [10]. Many centres lack specialist HCPs such as nurses, pharmacists, dietitians, and physiotherapists to support patients throughout their treatment journey. A survey of the management of NTM-PD in UK-wide clinical practice showed substantial variation in practices throughout the UK. Across sites treating patients with NTM-PD, most of which were TB clinics, 68% had support available from clinical nurse specialists, 47% had support from physiotherapists, and 41% had support from pharmacists [79]. Specialist (clinical) pharmacists with knowledge and experience in NTM-PD are unfortunately not always available in the UK. Efforts are underway within the UK to increase general practice access to clinical pharmacists [80], whose knowledge can positively impact health outcomes, particularly in cases of polypharmacy and long-term conditions [10,81]. However, the availability of such specialists remains low; therefore, such expertise cannot always be made available to patients with NTM-PD. In the authors’ opinion, the formation of both local and national networks could help build awareness of NTM-PD amongst pharmacists in primary and secondary care, mitigating the need for patients to be solely managed by specialist pharmacists, through the use of referral pathways for advice and guidance and harmonising the quality of care for all patients. Additionally, pharmacists taking a role within hospital MDTs can be of great benefit, such as in-home intravenous antibiotics services to prevent unnecessarily long hospital stays, where the pharmacist can advise on appropriate intravenous drug regimens, the administration of drugs, and drug stability. Moreover, the establishment of MDTs for NTM-PD-related services can be informed from the experience gained in the successful establishment of MDTs in other areas of lung disease (e.g., CF and bronchiectasis), supporting patient access to specialist HCPs [10].

Patients can benefit from education and support after a diagnosis of NTM-PD [10], but these have been limited in the UK. The NTM Patient Care UK Association [82] was established in 2018 to improve access to information for patients with this disease. NTM Patient Care UK has recently released patient-directed materials to help with patient education [83,84]. Tools to assist patients in communicating with HCPs can also be beneficial.

To address the need for consistent, standardised, high-quality care for patients with NTM-PD, NTM Network UK, in partnership with HCPs, patients, and professional associations, launched the first Standards of Care for NTM-PD in 2024 [85].

5. Concluding Remarks

Further research is required to understand the differences in regional variations in NTM-PD prevalence, management, and referral pathways in the UK, as well as to develop more efficient therapeutic strategies to target different NTM species. There remain significant clinical challenges in the diagnosis and treatment of NTM-PD, and international guidelines are predominantly based on experience and case studies. The lack of effective evidence-based treatments, the development of mutational resistance, poor adherence to guidelines, drug toxicity leading to poor adherence, late diagnosis due to lack of physician awareness, and the lack of regional specialist centres and referral pathways are all factors contributing to the poor NTM-PD treatment outcomes. Mitigating these factors is paramount to improving treatment outcomes in patients with NTM-PD.

Funding

This research was funded by Insmed UK, Ltd.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analysed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing support, which was funded by Insmed UK, Ltd., was provided by Anzar Qurbain, MBBS, BSc (Hons), MBA of MedicalGoGo (UK), and Remedica Communications (UK).

Conflicts of Interest

Toby Capstick received non-financial support from Napp and GSK for his attendance at the European Respiratory Society (ERS) conference. His employer has received payment from AstraZeneca, Chiesi, GSK, Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Orion, and Insmed for his participation in advisory boards and for providing teaching sessions. The other authors have received consultancy fees from Insmed.

References

- Cowman, S.; Ingen, J.; Griffith, D.E.; Loebinger, M.R. Non-tuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease. Eur. Respir. J. 2019, 54, 1900250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, L.O.; Polverino, E.; Hoefsloot, W.; Codecasa, L.R.; Diel, R.; Jenkins, S.G.; Loebinger, M.R. Pulmonary disease by non-tuberculous mycobacteria–clinical management, unmet needs and future perspectives. Expert Rev. Respir. Med. 2017, 11, 977–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musaddaq, B.; Cleverley, J. Diagnosis of non-tuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease (NTM-PD): Modern challenges. Br. J. Radiol. 2020, 93, 20190768. [Google Scholar]

- Schiff, H.F.; Jones, S.; Achaiah, A.; Pereira, A.; Stait, G.; Green, B. Clinical relevance of non-tuberculous mycobacteria isolated from respiratory specimens: Seven year experience in a UK hospital. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, V.N.; Mølhave, M.; Fløe, A.; van Ingen, J.; Schön, T.; Lillebaek, T.; Andersen, A.B.; Wejse, C. Global trends of pulmonary infections with nontuberculous mycobacteria: A systematic review. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 125, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingen, J.; Obradovic, M.; Hassan, M.; Lesher, B.; Hart, E.; Chatterjee, A.; Daley, C.L. Nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease caused by Mycobacterium avium complex—Disease burden, unmet needs, and advances in treatment developments. Expert Rev. Respir. Med. 2021, 15, 1387–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, D.; Ingen, J.; Laan, R.; Obradovic, M. Non-tuberculous mycobacterial lung disease in patients with bronchiectasis: Perceived risk, severity and guideline adherence in a European physician survey. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2020, 7, e000498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prevots, D.R.; Marras, T.K. Epidemiology of human pulmonary infection with nontuberculous mycobacteria: A review. Clin. Chest Med. 2015, 36, 13–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winthrop, K.L.; McNelley, E.; Kendall, B.; Marshall-Olson, A.; Morris, C.; Cassidy, M.; Saulson, A.; Hedberg, K. Pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial disease prevalence and clinical features: An emerging public health disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2010, 182, 977–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipman, M.; Cleverley, J.; Fardon, T.; Musaddaq, B.; Peckham, D.; Laan, R.; Whitaker, P.; White, J. Current and future management of non-tuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease (NTM-PD) in the UK. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2020, 7, e000591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schildkraut, J.A.; Gallagher, J.; Morimoto, K.; Lange, C.; Haworth, C.; Floto, R.A.; Hoefsloot, W.; Griffith, D.E.; Wagner, D.; Ingen, J. Epidemiology of nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease in Europe and Japan by Delphi estimation. Respir. Med. 2020, 173, 106164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haworth, C.S.; Banks, J.; Capstick, T.; Fisher, A.J.; Gorsuch, T.; Laurenson, I.F.; Leitch, A.; Loebinger, M.R.; Milburn, H.J.; Nightingale, M.; et al. British Thoracic Society guideline for the management of non-tuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease (NTM-PD). BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2017, 4, e000242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, J.E.; Kruijshaar, M.E.; Ormerod, L.P.; Drobniewski, F.; Abubakar, I. Increasing reports of non-tuberculous mycobacteria in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, 1995–2006. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, O.M.; Laan, R.; Obradovic, M.; McMahon, P.; Daniels, F.; Pitcher, A.; Loebinger, M.R. Identification of potentially undiagnosed patients with nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease using machine learning applied to primary care data in the UK. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 56, 2000045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Axson, E.L.; Bloom, C.I.; Quint, J.K. Nontuberculous mycobacterial disease managed within UK primary care, 2006–2016. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2018, 37, 1795–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Tsai, Y.; Wu, H.; Wang, J.; Yu, C.; Lee, L.; Yang, P. Impact of non-tuberculous mycobacteria on pulmonary function decline in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2012, 16, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skolnik, K.; Kirkpatrick, G.; Quon, B.S. Nontuberculous mycobacteria in cystic fibrosis. Curr. Treat. Options Infect. Dis. 2016, 8, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axson, E.L.; Bual, N.; Bloom, C.I.; Quint, J.K. Risk factors and secondary care utilisation in a primary care population with non-tuberculous mycobacterial disease in the UK. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2019, 38, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lande, L.; Peterson, D.D.; Gogoi, R.; Daum, G.; Stampler, K.; Kwait, R.; Yankowski, C.; Hauler, K.; Danley, J.; Sawicki, K.; et al. Association between pulmonary Mycobacterium avium complex infection and lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2012, 7, 1345–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, T.L.; Lin, C.F.; Chen, Y.M.; Liu, H.J.; Chen, D.Y. Risk factors and outcomes of nontuberculous mycobacterial disease among rheumatoid arthritis patients: A case-control study in a TB endemic area. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 29443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, A.; Hebisawa, A.; Kusaka, K.; Hirose, T.; Suzuki, J.; Yamane, A.; Nagai, H.; Fukami, T.; Ohta, K.; Takahashi, F. Relationship between lung cancer and Mycobacterium avium complex isolated using bronchoscopy. Open Respir. Med. J. 2016, 10, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loebinger, M.R.; Quint, J.K.; van der Laan, R.; Obradovic, M.; Chawla, R.; Kishore, A.; van Ingen, J. Risk Factors for Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Pulmonary Disease: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. Chest 2023, 164, 1115–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prevots, D.R.; Adjemian, J.; Fernandez, A.G.; Knowles, M.R.; Olivier, K.N. Environmental risks for nontuberculous mycobacteria: Individual exposures and climatic factors in the cystic fibrosis population. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2014, 11, 1032–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, C.; Reyn, C.F.; Chamblee, S.; Ellerbrock, T.; Johnson, J.W.; Marsh, B.J.; Johnson, L.S.; Trenschel, R.J.; Horsburgh, C.R. Environmental risk factors for infection with Mycobacterium avium complex. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2006, 164, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, C.J.; Olivier, K.N.; Leung, J.M.; Smith, C.C.; Huth, A.G.; Root, H.; Kuhns, D.B.; Logun, C.; Zelazny, A.; Frein, C.A.; et al. Abnormal nasal nitric oxide production, ciliary beat frequency, and toll-like receptor response in pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial disease epithelium. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 187, 1374–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutzky, V.P.; Ratnatunga, C.N.; Smith, D.J.; Kupz, A.; Doolan, D.L.; Reid, D.W.; Thomson, R.M.; Bell, S.C.; Miles, J.J. Anomalies in T cell function are associated with individuals at risk of Mycobacterium abscessus complex infection. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, C.; Wang, J.; Wu, M.; Lai, H.; Chiang, B.; Yu, C. Interleukin 23/interleukin 17 axis activated by Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) is attenuated in patients with MAC-lung disease. Tuberculosis 2018, 110, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, R.D.; Greenberg, D.E.; Ehrmantraut, M.E.; Guide, S.; Ding, L.; Shea, Y.; Brown, M.R.; Chernick, M.; Steagall, W.K.; Glasgow, C.G.; et al. Pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial disease: Prospective study of a distinct preexisting syndrome. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2008, 178, 1066–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Affandi, J.S.; Hendry, S.; Waterer, G.; Thomson, R.; Wallace, H.; Burrows, S.; Price, P. Searching for an immunogenetic factor that will illuminate susceptibility to non-tuberculous mycobacterial disease. Human Immunol. 2013, 74, 1382–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnia, P.; Ghanavi, J.; Saif, S.; Farnia, P.; Velayati, A.A. Association of interferon-1 gene polymorphism with nontuberculous mycobacterial lung infection among Iranian patients with pulmonary disease. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2017, 97, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, C.D.; Claxton, P.; Doig, C.; Seagar, A.; Rayner, A.; Laurenson, I.F. Non-tuberculous mycobacteria: A retrospective review of Scottish isolates from 2000 to 2010. Thorax 2014, 69, 593–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Andréjak, C.; Nielsen, R.; Thomsen, V.Ø.; Duhaut, P.; Sørensen, H.T.; Thomsen, R.W. Chronic respiratory disease, inhaled corticosteroids and risk of non-tuberculous mycobacteriosis. Thorax 2013, 68, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, D.E.; Aksamit, T.; Brown-Elliott, B.A.; Catanzaro, A.; Daley, C.; Gordin, F.; Holland, S.M.; Horsburgh, R.; Huitt, G.; Iademarco, M.F.; et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2007, 175, 367–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daley, C.L.; Iaccarino, J.M.; Lange, C.; Cambau, E.; Wallace, R.J.; Andrejak, C.; Böttger, E.C.; Brozek, J.; Griffith, D.E.; Guglielmetti, L.; et al. Treatment of nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease: An official ATS/ERS/ESCMID/IDSA clinical practice guideline. Clin. Inf. Dis. 2020, 71, e1–e36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floto, R.A.; Olivier, K.N.; Saiman, L.; Daley, C.L.; Herrmann, J.L.; Nick, J.A.; Noone, P.G.; Bilton, D.; Corris, P.; Gibson, R.L.; et al. US Cystic Fibrosis Foundation and European Cystic Fibrosis Society consensus recommendations for the management of non-tuberculous mycobacteria in individuals with cystic fibrosis. Thorax 2016, 71 (Suppl. 1), i1–i22. [Google Scholar]

- Ingen, J.; Wagner, D.; Gallagher, J.; Morimoto, K.; Lange, C.; Haworth, C.S.; Floto, R.A.; Adjemian, J.; Prevots, D.R.; Griffith, D.E. Poor adherence to management guidelines in nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary diseases. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 49, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch, S.; Laan, R.; Crichton, M.; Clifton, I.; Gatheral, T.; Walker, P.; Haworth, C.; Hill, A.; Loebinger, M.; Goeminne, P.; et al. M8 Non-tuberculous mycobacteria testing in bronchiectasis in the UK: Data from the EMBARC registry. Thorax 2019, 74, A238–A239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polverino, E.; Goeminne, P.C.; McDonnell, M.J.; Aliberti, S.; Marshall, S.E.; Loebinger, M.R.; Murris, M.; Cantón, R.; Torres, A.; Dimakou, K.; et al. European Respiratory Society guidelines for the management of adult bronchiectasis. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 50, 1700629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, A.T.; Sullivan, A.L.; Chalmers, J.D.; Soyza, A.; Stuart, E.J.; Andres, F.R.; Grillo, L.; Gruffydd-Jones, K.; Harvey, A.; Haworth, C.S.; et al. British Thoracic Society guideline for bronchiectasis in adults. Thorax 2019, 74, 1–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, J.D.; Sethi, S. Raising awareness of bronchiectasis in primary care: Overview of diagnosis and management strategies in adults. NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med. 2017, 27, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingen, J. Microbiological diagnosis of nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease. Clin. Chest Med. 2015, 36, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, J.D.; Aksamit, T.; Carvalho, A.C.; Rendon, A.; Franco, I. Non-tuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary infections. Pulmonology 2018, 24, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, Y.; Kinjo, T.; Motooka, D.; Nabeya, D.; Jung, N.; Uechi, K.; Horii, T.; Iida, T.; Fujita, J.; Nakamura, S. Comprehensive subspecies identification of 175 nontuberculous mycobacteria species based on 7547 genomic profiles. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2019, 8, 1043–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Lee, H.; Lee, M.; Lee, S.; Shim, T.; Lim, S.Y.; Koh, W.; Yim, J.; Munkhtsetseg, B.; Kim, W.; et al. Development and application of multiprobe real-time PCR method targeting the hsp65 gene for differentiation of Mycobacterium species from isolates and sputum specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010, 48, 3073–3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcolea-Medina, A.; Fernandez, M.T.; Montiel, N.; García, M.P.; Sevilla, C.D.; North, N.; Lirola, M.J.; Wilks, M. An improved simple method for the identification of mycobacteria by MALDI-TOF MS (Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption-Ionization mass spectrometry). Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Temporal, D.; Herrera, L.; Alcaide, F.; Domingo, D.; Hery-Arnaud, G.; van Ingen, J.; Van den Bossche, A.; Ingebretsen, A.; Beauruelle, C.; Terschlusen, E.; et al. Identification of mycobacterium abscessus subspecies by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry and machine learning. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2023, 61, e0111022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruedas-López, A.; Tato, M.; Broncano-Lavado, A.; Esteban, J.; Ruiz-Serrano, M.J.; Sánchez-Cueto, M.; Toro, C.; Domingo, D.; Cacho, J.; Barrado, L.; et al. Subspecies distribution and antimicrobial susceptibility testing of mycobacterium abscessus clinical isolates in Madrid, Spain: A retrospective multicenter study. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0504122. [Google Scholar]

- Gruffydd-Jones, K.; Keeley, D.; Knowles, V.; Recabarren, X.; Woodward, A.; Sullivan, A.L.; Loebinger, M.R.; Payne, K.; Harvey, A.; Grillo, L.; et al. Primary care implications of the British Thoracic Society guidelines for bronchiectasis in adults 2019. NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med. 2019, 29, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Song, J.; Chae, E.J.; Lee, H.J.; Lee, C.; Do, K.; Seo, J.B.; Kim, M.; Lee, J.S.; Song, K.; et al. CT findings of pulmonary non-tuberculous mycobacterial infection in non-AIDS immunocompromised patients: A case-controlled comparison with immunocompetent patients. Br. J. Radiol. 2013, 86, 20120209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loebinger, M.R. Mycobacterium avium complex infection: Phenotypes and outcomes. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 50, 1701380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zweijpfenning, S.; Kops, S.; Magis-Escurra, C.; Boeree, M.J.; van Ingen, J.; Hoefsloot, W. Treatment and outcome of non-tuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease in a predominantly fibro-cavitary disease cohort. Respir. Med. 2017, 131, 220–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.A.; Kim, S.; Jo, K.; Shim, T.S. Natural history of mycobacterium avium complex lung disease in untreated patients with stable course. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 49, 1600537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haworth, C.S.; Floto, R.A. Introducing the new BTS guideline: Management of non-tuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease (NTM-PD). Thorax 2017, 72, 969–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; Cheng, M.; Lu, P.; Liu, C.; Chong, I.; Wang, J. Predictors of developing Mycobacterium kansasii pulmonary disease within 1 year among patients with single isolation in multiple sputum samples: A retrospective, longitudinal, multicentre study. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 17826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhun, B.W.; Moon, S.M.; Jeon, K.; Kwon, O.J.; Yoo, H.; Carriere, K.C.; Huh, H.J.; Lee, N.Y.; Shin, S.J.; Daley, C.L.; et al. Prognostic factors associated with long-term mortality in 1445 patients with nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease: A 15-year follow-up study. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 55, 1900798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Lee, M.; Liu, C.; Cheng, M.; Lu, P.; Wang, J.; Chong, I. Predictors of radiographic progression for NTM-pulmonary disease diagnosed by bronchoscopy. Respir. Med. 2020, 161, 105847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mar, P.L.; Horbal, P.; Chung, M.K.; Dukes, J.W.; Ezekowitz, M.; Lakkireddy, D.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Miletello, M.; Noseworthy, P.A.; Reiffel, J.A.; et al. Drug Interactions Affecting Antiarrhythmic Drug Use. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2022, 15, e007955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Mellal, A.; Hussain, N.; Said, A.S. The clinical significance of statins-macrolides interaction: Comprehensive review of in vivo studies, case reports, and population studies. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2019, 15, 921–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiberi, S.; Lipman, M.C.; Floto, A. Case studies to illustrate good practice in the management of non-tuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease. Respir. Med. Case Rep. 2022, 38, 101668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velagapudi, M.; Sanley, M.J.; Ased, S.; Destache, C.; Malesker, M.A. Pharmacotherapy for nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease. Am. J. Health-Syst. Pharm. 2021, 79, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Lee, K.S.; Moon, J.W.; Koh, W.; Jeong, B.; Jeong, Y.J.; Kim, H.J.; Woo, S. Nodular bronchiectatic Mycobacterium avium complex pulmonary disease. Natural course on serial computed tomographic scans. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2013, 10, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipman, M.; Kunst, H.; Loebinger, M.R.; Milburn, H.J.; King, M. Non tuberculous mycobacteria pulmonary disease: Patients and clinicians working together to improve the evidence base for care. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 113, S73–S77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prevots, R.D.; Loddenkemper, R.; Sotgiu, G.; Migliori, G.B. Nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease: An increasing burden with substantial costs. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 49, 1700374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, K.W.; Park, Y.E.; Chong, Y.P.; Shim, T.S. Spontaneous sputum conversion and reversion in Mycobacterium abscessus complex lung disease. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.; Rand, I.A.; Addy, C.; Collyns, T.; Hart, S.; Mitchelmore, P.; Rahman, N.; Saggu, R. British Thoracic Society guideline for the use of long-term macrolides in adults with respiratory disease. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2020, 7, e000489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morimoto, K.; Namkoong, H.; Hasegawa, N.; Nakagawa, T.; Morino, E.; Shiraishi, Y.; Ogawa, K.; Izumi, K.; Takasaki, J.; Yoshiyama, T.; et al. Macrolide-resistant Mycobacterium avium complex lung disease: Analysis of 102 consecutive cases. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2016, 13, 1904–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Jhun, B.W.; Kim, J.; Huh, H.J.; Lee, N.Y. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of surgically resected solitary pulmonary nodules due to nontuberculous mycobacterial infections. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokadiya, S.; Millar, F.R.; Tiberi, S. Non-tuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease: A clinical update. Br. J. Hosp. Med. 2018, 79, C118–C122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crilly, N.P.; Ayeh, S.K.; Karakousis, P.C. The new frontier of host-directed therapies for Mycobacterium avium complex. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 623119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, C.; Böttger, E.C.; Cambau, E.; Griffith, D.E.; Guglielmetti, L.; van Ingen, J.; Knight, S.L.; Marras, T.K.; Olivier, K.N.; Santin, M.; et al. Consensus management recommendations for less common non-tuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary diseases. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, e178–e190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, J.M.; Grogono, D.M.; Greaves, D.; Foweraker, J.; Roddick, I.; Inns, T.; Reacher, M.; Haworth, C.S.; Curran, M.D.; Harris, S.R.; et al. Whole-genome sequencing to identify transmission of Mycobacterium abscessus between patients with cystic fibrosis: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2013, 381, 1551–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, J.M.; Grogono, D.M.; Rodriguez-Rincon, D.; Everall, I.; Brown, K.P.; Moreno, P.; Verma, D.; Hill, E.; Drijkoningen, J.; Gilligan, P.; et al. Emergence and spread of a human-transmissible multidrug-resistant nontuberculous Mycobacterium. Science 2016, 354, 751–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, N.; Park, J.; Kim, E.; Lee, C.; Han, S.K.; Yim, J. Treatment outcomes of Mycobacterium avium complex lung disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Inf. Dis. 2017, 65, 1077–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, R.J.J.; Brown-Elliott, B.A.; McNulty, S.; Philley, J.; Killingley, J.; Wilson, R.W.; York, D.S.; Shepherd, S.; Griffith, D.E. Macrolide/azalide therapy for nodular/bronchiectatic Mycobacterium avium complex lung disease. Chest 2014, 146, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NHS England. Clinical Commissioning Policy. Nebulised Liposomal Amikacin for the Treatment of Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Pulmonary Disease Caused by Mycobacterium Avium Complex Refractory to Current Treatment Options (Adults and Post Pubescent Children) (2111) [221007P]. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/2111-Clinical-commissioning-policy-nebulised-liposomal-amikacin-for-the-treatment-of-non-tuberculous-mycobacte.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Johnson, T.M.; Byrd, T.F.; Drummond, W.K.; Childs-Kean, L.M.; Mahoney, M.V.; Pearson, J.C.; Rivera, C.G. Contemporary pharmacotherapies for nontuberculosis mycobacterial infections: A narrative review. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2023, 12, 343–365. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aznar, M.L.; Marras, T.K.; Elshal, A.S.; Mehrabi, M.; Brode, S.K. Safety and effectiveness of low-dose amikacin in nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease treated in Toronto, Canada. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2019, 20, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, P.; Lee, S.H.; O’Sullivan, M.; Cullen, W.; Kennedy, C.; MacFarlane, A. Assessing the facilitators and barriers of interdisciplinary team working in primary care using normalisation process theory: An integrative review. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, A.; Bryant, S.; King, M.; Kunst, H.; Haworth, C.; Lipman, M. P29 How are we managing non-tuberculous mycobacteria pulmonary disease (NTM-PD)? Results from the first UK-wide survey of clinical practice. Thorax 2021, 76, A81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claire, M.; Claire, A.; Matthew, B. The role of clinical pharmacists in general practice in England: Impact, perspectives, barriers and facilitators. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2022, 18, 3432–3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, A.M.; Mara, K.C.; Rivera, C.G. Clinical pharmacists’ interventions and therapeutic drug monitoring in patients with mycobacterial infections. J. Clin. Tuberc. Other Mycobact. Dis. 2023, 30, 100346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NTM Patient Care UK Website. Available online: https://www.ntmpatientcare.uk/ (accessed on 13 June 2024).

- NTM Patient Care UK FAQ Booklet. Available online: https://www.ntmpatientcare.uk/faqs (accessed on 13 June 2024).

- NTM Patient Care UK Treatment of NTM Tips & Information. Available online: https://www.ntmpatientcare.uk/coping-with-the-medicines (accessed on 13 June 2024).

- NTM Network UK. Standards of Care for People Living with Non-Tuberculous Mycobacterial (ntm) Disease in the UK. Version 1. July 2024. Available online: https://www.ntmnetworkuk.com/standards-of-care (accessed on 7 August 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).