Abstract

In this review, we examine the impact of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022 on pharmaceutical drugs in the United States, drawing on a diverse range of sources to understand the perceptions of multiple stakeholders and professionals. Findings suggest that the Act, while aiming to control price inflation, has had a multifaceted impact on the pharmaceutical sector. Stakeholders, including pharmaceutical companies, healthcare providers, patient advocacy groups, and policymakers, offered varied perspectives: while some laud the Act for its potential in controlling runaway drug prices and making healthcare more accessible, others raise concerns about possible reductions in drug innovation, disruptions to supply chains, and the sustainability of smaller pharmaceutical companies. The review identified four underlying constructs (themes) in the literature surrounding healthcare stakeholders’ perceptions of the IRA’s impact upon prescription drugs: pricing and/or dictation pricing issues, topics related to patent law and pharmaceuticals, processes surrounding the IRA’s (2022) rules and regulations, and potential threats to the pharmaceutical industry concerning the research and development of future medications. The complex interplay of the Act’s implications underscores the importance of ongoing assessment and potential iterative policy refinements as implementation endures.

1. Introduction

The rising cost of prescription drugs has become a significant concern within the healthcare sector, impacting patients, healthcare providers, insurers, and the United States government. In response to this issue, policy measures aimed at curbing inflation and reducing healthcare expenditures continue. One such policy initiative is the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022, a legislative intervention designed to address escalating costs within the pharmaceutical industry, patient affordability of prescription drugs, and reduce Medicare drug expenditures [1]. An important goal of the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 is to reduce prices for brand-named drugs in the United States. At first glance, the IRA seems to cut the prices of only a few drugs. Ten will be selected for 2026, fifteen more for 2027 and 2028, twenty for 2029, and twenty each year thereafter. Any of those will have been on the market for at least nine years (thirteen for biologicals) and priced during that time at the manufacturers’ discretion. Even after seven years, manufacturers are supposed to have input on price control decisions. Finally, only the drugs used in Medicare are subject to price controls.

This narrative literature review seeks to comprehensively analyze and synthesize the existing body of research and publications regarding the impact of the IRA on prescription drugs in the United States, as perceived by various healthcare industry stakeholders in the recently published literature. Understanding the potential impact and outcomes of the Inflation Reduction Act is essential for shaping future healthcare policies aimed at ensuring affordable and accessible prescription drugs for all. This review aimed to provide a comprehensive understanding of the effectiveness and implications of the IRA in addressing the economic and healthcare challenges associated with escalating prescription drug prices. Due to the recentness of the IRA and its application, limited research has been completed to date.

1.1. Rationale

A burst of articles has already appeared around the effects of the IRA on Medicare costs, on the one hand, and manufacturer profits, on the other. Politicians have long criticized what they perceive as the overpricing of patented drugs, but have always been blocked to affect pricing by the manufacturers—until now. Although the IRA application has recently begun, its impact has been considered a potential paradigm shift by multiple stakeholders with opposing expected outcomes. However, all expect it to open the door for the broader control of drug pricing and industry change. Fearing this will be the case, major drug manufacturers have filed lawsuits to block its implementation [1]. They argue that it violates their constitutional and statutory rights, and they challenge the penalties of more than USD 500 million that can be imposed on a manufacturer for refusing to negotiate price reduction.

1.2. Purpose

Hospitals, providers, and Medicare beneficiaries are waiting to see how the IRA will affect health care. The narrative review was conducted to query current literature focused on the Act’s influence on pharmaceuticals in the U.S., as projected by multiple healthcare industry stakeholder types. Findings will continue to support the understanding and development of ongoing/future U.S. policy and procedures surrounding prescription drugs for the U.S. healthcare system.

2. Methods

2.1. Overview

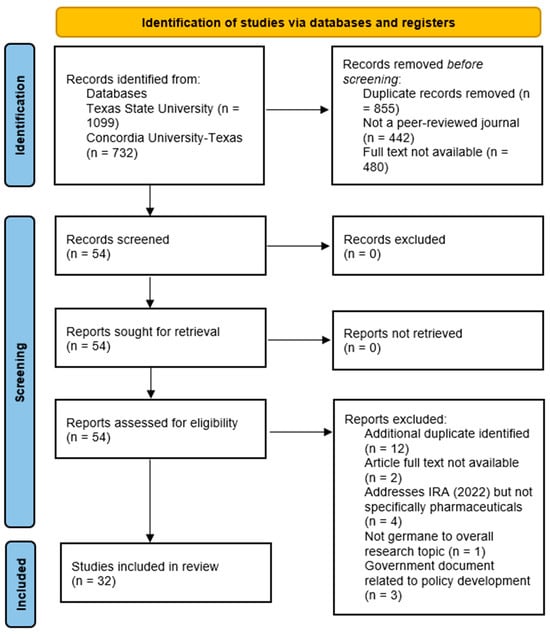

The research team’s initiative was to specifically identify various stakeholder perspectives surrounding the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act policy regarding prescription drugs in the United States as identified in the literature review process. The PRISMA (preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses) review standard guided the research team’s review process.

Two separate university library EBSCOhost research platforms were used in the initial review process to identify as many potential articles as possible for the review: Texas State University and Concordia University–Texas. This unique approach was decided on by the research team after identifying the limited information published to date in peer-reviewed journals. The following research databases were identified by both EBSCOhost library interface websites for the review: Academic Search Complete, OmniFile Full Texas Mega (H.W. Wilson), CINAHL Ultimate, Complementary Index, and MEDLINE Complete.

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

Initially, the review team worked at the individual level, and then as a group, to query Google and other public search engines to identify potential search terms and/or phrases to include in the review process. Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), the controlled vocabulary thesaurus utilized for indexing articles for PubMed was also reviewed for applicable terminology, yet none identified with this review. As a result, the research team utilized Google search queries to begin establishing search terminology and related Boolean operators which yielded the highest applicable publication results around the topic. The final string identified by the research team was:

[(inflation reduction act) AND (drug*)]

The research team truncated ‘drug’ in the search string to instruct the database to search for all forms of that word (ex., drug vs. drugs), therefore yielding higher search results on both EBSCOhost platforms. This approach also worked to identify articles referring simply to ‘drugs’, as well as those referencing ‘prescription drugs’.

All articles meeting this inclusion criteria were exported from their respective research databases into a single MS Excel spreadsheet, keeping their original institution’s EBSCOhost origin database coded (Texas State University or Concordia University–Texas) for review process transparency. The spreadsheet was then sorted to identify duplicate articles identified across both searches and a single list of initial included manuscripts was recognized. This initial search string collectively yielded a combined total of 1831 results. As the Inflation Reduction Act was passed by the 117th United States Congress and signed into law by President Biden on 16 August 2022, the research team identified many IRA-related articles published prior to this date, and therefore chose to filter search results to only articles published after 1 January 2022, through 1 March 2023. On the other hand, due to prior U.S. legislation utilizing the terms ‘inflation’ and also ‘reduction’ in their policy names (to include prior Inflation Reduction Acts specifically), the research team identified other articles surrounding prior IRA-related policies prior to 1 January 2022, therefore identifying the 1 January 2022 to-date (1 March 2023) search criteria to best identify articles for this review.

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

Articles were included in the review if they specifically addressed the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 and specifically addressed prescription drugs as potentially underlying themes within any identified article. Publications included in the review analysis had to initially be classified as peer-reviewed journals in the EBSCOhost search engines and meet the publication date range. Our team’s rapid review process objective was to identify any/all initial perceptions by various identified prescription drug stakeholders affected by this recent legislation, such as researchers, developers, manufacturers, insurers, dispensers, and patients. These stakeholders have immediate understanding of the pharmaceutical industry and provide assumptions and related observations from their professional position within the healthcare industry of potential outcomes which have not yet been fully identified or experienced.

Additional search parameters were applied to produce focused, applicable results that met the team’s research objective. The EBSCOhost database platform automatically removed 855 duplicate articles. In addition to filtering for the publication date, the research team excluded any articles that were not available in full-text format (−480 articles) and were not published in peer-reviewed journals (−442 articles). All identified articles in the search were available in English, so no exclusions occurred for language filtering. A final exclusion of geography (United States only) was applied to the review findings, yet this yielded no additional articles to remove from the search. A total of 54 remaining articles were identified for this narrative review. Figure 1 illustrates the research team’s process and applied search criteria, narrowing the final number of manuscripts included in the review process to 32.

Figure 1.

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) figure that demonstrates the study selection process.

A full-text review of the remaining 32 articles was conducted by the review team, with each article being reviewed by two or more members of the research team. Table 1 shows the review assignments for the articles identified. Each article was reviewed (full-text review) by three of the research team members across all article reading assignments.

Table 1.

Reviewer assignment of the initial database search findings (full article review).

3. Results

The identified studies’ quality, as assessed through the use of the JHNEBP study design coding methodology, demonstrated that the majority of the literature (16 articles, 50% of the sample) falls within the level 5 category (opinions of industry experts not based on research evidence). A combined 14 (43%) articles represented JHNEBP levels 3 and 4. The remaining literature in the sample demonstrated a study design interpreted as level 2, a quasiexperimental study, or level 3, a nonexperimental, qualitative, or metasynthesis study. While the strength of evidence regarding this review’s literature sample (primarily consisting of level 4 and 5 study designs) is important to note, the researchers came to the conclusion that this observation was possibly due to the nature and timeliness of this review and ongoing publications surrounding the recent Inflation Reduction Act’s influence upon prescription drugs in the United States.

There may be limitations in carrying out true experimental studies, such as randomized controlled trials (RCTs), to evaluate the implementation of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022 thus far. Consequently, the research team opted for a narrative review approach, focusing on articles that were classified as level 4 and 5 evidence. This was done in an effort to gauge current opinions of various stakeholders on the subject, drawing from the available peer-reviewed literature up to this point (Table 2).

Table 2 also addresses article publication information (author(s) and article title). The table provides summaries of the stakeholder’s themselves, such as job title, place of work, etc., to assist the reader in understanding where their perspective on the IRA’s (2022) influence on prescription drugs is originating. The research team synthesized the material to provide a comprehensive summary of various stakeholder perspectives. Providing the origin of the source material, specifically identifying the stakeholders in Table 2, presents the breadth of potential bias the research team reviewed and distilled. The team identified a consistent bias from the individual groups: manufacturers were concerned with the potential impact on research and development, driven from lower revenue, insurers considered the impact on Medicare Advantage plans and cost apportionment, while dispenser and patients focused on the financial benefits and potential increased adherence to prescribed regimens.

Table 2.

Summary of findings (n = 32).

Table 2.

Summary of findings (n = 32).

| Article Number and EBSCOhost Library Indicator († ^) | Article Title and Author Name(s) | Healthcare Stakeholder | Pricing Issue OR Dictating Pricing | Patent Law with Regard to the IRA | Process for Rules and Regulations | Threats to Pharmaceutical R&D | JHNEBP Study Design * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1] | † | Inflation Reduction Act and US drug pricing Sarpatwari, A. (2022) | Academic (Assistant Professor) |

|

|

| 4 | |

| [2] | † | 2022 Inflation Reduction Act: Climate Investments Are Public Health Investments Levy, J. (2022) | Journal Associate Editor |

| n/a | n/a | n/a | 4 |

| [3] | † | Inflation Reduction Act and the Impact on Pharmaceutical Pricing and Investment Decisions Creighton, D. (2022) | Life Sciences Consulting Firm Partner |

|

|

|

| 5 |

| [4] | † | Study: Heart Failure Patients Could Save with Inflation Reduction Act Myshko, D, (2023) | Medical Practitioner |

| 5 | |||

| [5] | † | Inflation Reduction Act Could Have Ripple Effects in Medicare Part D Woody & Lazarou (2023) | Multiple Healthcare Positions, including Researcher and Healthcare Strategist |

|

|

| 5 | |

| [6] | † | Webinar: Inflation Reduction Act Will Be Positive for Medicare Myshko, D. (2022) | Not Provided |

| 5 | |||

| [7] | † | The Potential Impact of the IRA: Interpreting what the Inflation Reduction Act could mean for biopharma Henderson, L. (2023) | Not Provided |

|

|

| 5 | |

| [8] | † ^ | Inflation Reduction Act Celebration Caldwell, S. (2022) | School Nurse |

|

| 5 | ||

| [9] | † | New Legislation Overhauls Medicare Drug Pricing and Benefits: Pharma loses battle to block pricing negotiations, but implementation faces many challenges Wechsler, J. (2022) | Journal Editor |

|

|

|

| 5 |

| [10] | † | Inflation Reduction Act Contains Important Cost-Saving Changes for Many Patient—Maybe for You McAuliff, M. (2022) | Independent Reporter |

|

| 5 | ||

| [11] | † | Pharma versus pricing, again Iskowitz, M. (2023) | Not Provided |

|

|

|

| 5 |

| [12] | † ^ | Impending Relief for Medicare Beneficiaries—The Inflation Reduction Act Dusetzina & Haiden (2022) | Academics from the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine (S.D.) and Harvard Medical School (H.H.) |

|

| 4 | ||

| [13] | † ^ | Simulated Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Under the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 Rome, et al. (2023) | Multiple Medical Providers (Physicians) and other Healthcare Professionals |

|

|

| 3 | |

| [14] | † ^ | What U.S. hospitals and health systems can expect from the 2022 IRA Perez, K. (2022) | VP of Healthcare Policy and Government Affairs at a Private Healthcare Firm |

|

| 5 | ||

| [15] | † ^ | Bringing Transparency and Rigor to Medicare Drug Pricing Gottlieb, S. (2023) | Physician |

|

|

|

| 4 |

| [16] | ^ | Out-of-Pocket Drug Costs for Medicare Beneficiaries with Cardiovascular Risk Factors Under the Inflation Reduction Act Narasimmaraj et al. (2023) | Physicians and other Healthcare Professionals |

| 3 | |||

| [17] | ^ | Pharmaceutical Spending in Fee-for-Service Medicare: Looking Ahead to the Inflation Reduction Act Gellad & Hernandez (2022) | Physician; Pharmacist |

| 4 | |||

| [18] | ^ | The Inflation Reduction Act: A boon for the generic and biosimilar industry Niazi, S. (2022) | Academic (Pharmacy School) |

|

|

| 3 | |

| [19] | ^ | Assessing US Pharmaceutical Policy and Pricing Reform Legislation in Light of European Price and Cost Control Strategies Rodwin, M. (2022) | Academic |

|

|

| 4 | |

| [20] | ^ | Federal Officials Issue Initial Guidance to Rein in Drug Spending Harris, E. (2023) | Not Provided |

|

| 5 | ||

| [21] | ^ | The Inflation Reduction Act: Recasting the Medicare Prescription Drug Plans Adashi, et al. (2023) | Not Provided |

|

|

|

| 5 |

| [22] | ^ | Estimated Medicare Part B Savings from Inflationary Rebates Egilman & Kesselheim (2023) | Academics (Program on Regulation, Therapeutics, and Law) |

|

| 3 | ||

| [23] | ^ | The Inflation Reduction Act Will Change Who Pays for Cardiovascular Drugs under Medicare Part D Kazi et al., 2023 | Medical Providers and Medical School Academics |

|

|

| 3 | |

| [24] | ^ | Projected Impact of the Inflation Reduction Act on Out-Of-Pocket Drug Costs for Medicare Part D Beneficiaries with Cardiovascular Disease Kazi, et al., 2023 | Medical Providers and Medical School Academics |

|

| 3 | ||

| [25] | ^ | Medicare Drug Price Negotiation in the United States: Implications and Unanswered Questions Sullivan, S. (2023) | Academic (School of Pharmacy) |

|

| 3 | ||

| [26] | ^ | Medicare Negotiation of Prescription Drug Prices Ubl, S. (2022) | CEO of a Pharmaceutical Trade Group |

|

| 5 | ||

| [27] | ^ | New Reforms to Prescription Drug Pricing in the US: Opportunities and Challenges Hwang, et al. (2022) | Academics (Pharmacy School) |

|

|

| 4 | |

| [28] | ^ | Landmark law to curb Medicare drug prices will start to make an impact in three years Hut, N. (2022) | Journal Editor |

| The negotiated prices under the Act will start in 2026 for 10 Medicare Part D drugs, as selected by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). More drugs will be added in subsequent years, with Part B drug prices becoming eligible for negotiation in 2028. | 5 | ||

| [29] | ^ | Biotech Burnout Eisberg, N. (2022) | Journal Editor |

|

|

|

| 5 |

| [30] | ^ | Congress Extends Enhanced ACA Subsidies Keith, K. (2022) | Academic (Health Law) |

|

| 5 | ||

| [31] | ^ | Estimates of Insulin Out-of-Pocket Cap– Associated Prescription Satisfaction: Adherence, and Affordability Among Medicare Beneficiaries Li, et al. (2023) | Academics (Schools of Pharmacy) |

|

| 2 | ||

| [32] | ^ | The Inflation Reduction Act’s Out-Of-Pocket Prescription Drug Cost Cap Will Benefit over 1 Million Medicare Patients with Cardiovascular Risk Factors or Disease Narasimmaraj, P. et al., 2023 | Cardiology Faculty Fellow; Various Healthcare Professionals and Researchers |

|

| 2 |

† Manuscript was identified via the Concordia University–Texas library EBSCOhost website. ^ Manuscript was identified via the Texas State University library EBSCOhost website. * Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice (JHNEBP) levels of strength of evidence: Level 1, experimental study/randomized control trial (RCT); Level 2, quasiexperimental study; Level 3, nonexperimental, qualitative, or metasynthesis study; Level 4, opinion of nationally recognized experts based on research evidence/consensus panels; Level 5, opinions of industry experts not based on research evidence. Construct Code identification: A: pricing issue or dictating pricing; B: patent law with regard to the IRA; C: process for rules and regulations; D: threats to pharmaceutical R&D.

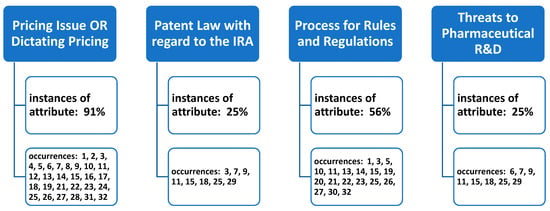

Once the total of thirty-two articles were reviewed by the research team, four underlying constructs (themes) were identified in the review. The research team met via webinar on multiple occasions to address the underlying constructs identified in the article reviews, and agreement was reached on the themes surrounding the stakeholder perspectives on the IRA’s (2022) influence on prescription drugs in the U.S. Article inclusion into thematic categories was not mutually exclusive, with any single article in the review often meeting criteria to be coded and assigned under more than one review theme (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Occurrences of underlying themes (constructs) identified in the literature of stakeholder perspectives of the Inflation Reduction Act’s (2022) impact on prescription drugs.

4. Discussion

4.1. Pricing

The historic IRA provides healthcare policy makers and the federal government new empowerment to deliberate the pricing of pharmaceuticals, approximating drug-cost policies that exist in European nations due to their freedom from patent protection constraints [19]. This new era of cost control allows the leveraging of lower drug costs for Americans on Medicare by complex and myriad forms.

Beginning in 2025, Medicare recipients will secure an out-of-pocket (OOP) pharmaceutical cap of USD 2000 annually, and indexed annually thereafter [33]. Drug costs above the cap will be absorbed by the insurers at 60%, and both Medicare and the manufacturers at 20%. Additional restraint on insurance premiums is also targeted to curtail costs [1,9].

The next inflationary and controversial measure is set for 2026, with the ten highest-spend pharmacy-dispensed drugs establishing a “maximum fair price” (MFP) arbitrated by Medicare and the manufacturers. The continuance of cost saving for patients will extend the MFP to twenty of the highest-spend pharmaceuticals in 2029 [1,3].

Additionally, drug prices that increase over the rate of inflation will be subject the manufacturers to furnish rebates to Medicare, further protecting older Americans from escalating medication costs. Further provisions for saving are waivers for vaccine costs, caps for insulin payments at USD 35 per month, and increasing aid for low-income individuals, thereby facilitating medication availability and compliance [1,6,10,12,16,24,31].

It is the communicated position of patient advocacy and healthcare providers, such as the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), to endorse the changes the IRA will make on the financial and physical well-being of patients, whereby the ability to obtain and maintain drug coverage will be eased, saving consumers millions of dollars [6,12,14]. In a simulated study [13], Medicare benefited by saving millions of dollars with drug-cost negotiation with the manufacturers. However, Medicare will also need to source funding for the 20% of drug costs that rise above a patient’s annual cap and are dually restricted by the reduced premiums for Part D [1,5,9,12].

On the other hand, as patients and communities reap the benefits of reduced costs, pharmaceutical companies are threatened by the loss of control and revenue of selected first and subsequent drugs. The forfeited monies due to negotiation, coupled with hovering penalties [1,9], have the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) cautioning that research and development will be adversely affected [7,9,11,25]. Concentration on drug selection, “optimal launch price”, and timelines for negotiation are of foremost importance to the PhRMA [3,6,7,26], and the prospect of legal or legislative repeal or challenge to the IRA by the pharmaceutical companies cannot be wholly dismissed [1,7,21].

Policymakers hold the middle ground, theorizing that competition will advance experimentation and progress will continue in drug innovation despite reduced revenue [9]. Another hope is that, by decreasing drug prices in Medicare, Medicaid and commercial plans may eventually find reprieve from escalating drug costs [1,9,10]. The one perspective most stakeholders agree on is the challenge and importance of drug selection, and that the process be transparent and consistent [3,7,13,15,34].

4.2. Patent Law

While the predominance of the material reviewed focused on the effects of pricing to consumers and the reimbursement the CMS would negotiate, there were conflicting viewpoints from pharmaceutical representatives and industry analysts. Primarily, the impact of the IRA on pharmaceutical the industry will potentially lead to a change in portfolio management, specifically the mechanics of portfolio valuation and strategy regarding the return on investment (ROI), as well as the ownership or foregoing of exclusivity in favor of the early entrance of generics [3,9,18]. Further, and similar to the 1984 Hatch–Waxman Act, which resulted in the introduction of generics and overall cost reduction, the pharmaceutical industry adjusted to the new norms, as shown by 90% of all dispensed drugs being generics while only representing 15% of the reimbursement [18]. While the IRA is presented as a new approach for government-sponsored healthcare programs, in fact, the Veterans Administration has historically negotiated price and, as of 2020, paid 54% less than Medicare Part D programs [25]. The negative impact on drug patents is noted primarily in material from the industry and proxy agencies representing pharmaceuticals, describing either financial or strategic choices that would limit drug research and intellectual property [3,7,9,11,25]. Conversely, academics and practitioners argue the alternatives to limiting the effects on patents [15,18,25]. The opposition regarding the effect on patents and intellectual property strategy addresses the potential financial impact of the IRA.

The Inflation Reduction Act’s impact on the future earnings of the pharmaceutical industry concerns Stephen Ubl, President of the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA), and Ed Schooveld, managing partner of ZS, a value and access practice [7]. What is implied, and not discussed, is the potential financial impact immediately upon the selection and subsequent negotiation under the Act. While patent strategies are discussed, identifying potential drug therapies that may be abandoned midstream or not presented for development, the selection by the CMS does not include future nonmonetized therapies. The reduction in future revenues would trigger an accounting valuation change on the patent value. The potential intangible asset value could result in a reduction or the impairment of the patents, in the case relating to existing portfolios, and potential immediate financial losses, as per the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). FASB rule 350-30-35—14 [1] defines the treatment of both the value of, and the impairment of, intangibles, which includes patents. Through the negotiation of the “maximum fair price”, the future revenue streams connected to the asset potentially could lower the fair value below that of the balance sheet, triggering an impairment and immediate expense [34]. With a 12% success rate of products under development entering the market beyond clinical trials, and the USD 1–2 billion cost to develop a new drug, the additional impact of the impairment on existing and profitable products could have a depressing effect on the return on investment that shareholders are seeking [11].

The Act does provide avenues from which the pharmaceutical companies can avoid the impact of the impairment. The patent exclusivity timeframe is impacted by the passing of the IRA for drugs selected for negotiation, but the foregoing of patent exclusivity in favor of the stimulation of generic products could present an alternative. Under the IRA, drugs which are expected to have a generic entrant to the market within two years are excluded from its scope [18].

4.3. Process for Rules and Regulations

The identified literature in the search clearly demonstrated the IRA (2022) was enacted in response to rising pharmaceutical costs that have burdened American citizens for years. The legislation aimed at making prescription drugs more affordable and accessible, while also ensuring that the quality and innovation in the industry remain uncompromised. A primary theme deduced from the research team’s manuscript review entailed overall stakeholder discussion surrounding the Act’s specific process and rules for regulations and related implementation initiatives. The IRA’s influence on prescription drugs remains widespread, to include the following main process changes to Medicare Part D [3,5,19]:

- Canceling the 5% coinsurance for catastrophic coverage;

- Expanding eligibility for financial support/assistance;

- Limiting premium increases from 2024 to 2029;

- Allowing Medicare to negotiate drug prices on behalf of consumers with pharmaceutical companies.

The review team focused on those identified subconstructs related to this theme as identified only in the review literature (exclusive only to this review’s findings).

4.3.1. Increased Drug Price Transparency

Central to the Act’s changes was a mandate for increased transparency in drug pricing for those medications selected for price negotiation [23]. Pharmaceutical companies are now required to disclose the breakdown of research, development, production, and marketing costs for each drug, allowing consumers and regulators a much clearer view into the factors driving drug prices. Further, and relevant to current/ongoing economic inflation challenges in the United States and beyond, a new provision prevents drug manufacturers from raising prices beyond a specified inflation rate without a justified reason, and establishes even more transparency in drug pricing [12,18]. This move was taken to prevent arbitrary price hikes, which have previously left patients unable to afford their necessary medications.

4.3.2. Drug Patent System Changes

Additional market forces and the CMS review may impact the value and monetization of patents moving forward [19]. This was completed to promote competition and reduce monopolistic practices; the new regulations restrict the duration and extent of exclusivity for certain drug patents, especially for medications that are crucial for public health [11,19,21]. While the IRA does not directly affect drug patents, it may impact the future revenue from new therapies by either reducing or limiting the length of time manufacturers can realize exclusive earnings. These barriers would further ensure that generic versions of essential drugs come into the market faster, providing more affordable options for consumers [19,21].

4.3.3. Pharmaceutical Negotiation Practices

The Act also establishes a body to negotiate drug prices directly with pharmaceutical companies on behalf of government healthcare programs, specifically Medicare [10,11,14,15]. This is expected to leverage the government’s buying power to drive down prices for millions of beneficiaries. The results of these negotiations would also be made public, bolstering the Act’s overarching goal of enhancing transparency and accountability in the pharmaceutical sector [14,15]. The concept of ‘launch pricing’ was also identified by the research team. The change in launch price, or market entry pricing during initial exclusive periods, may assist pharmaceutical companies in subsequent price negotiations with government and other agencies when the drug falls under the scope of price negotiation. By establishing a higher beginning drug price to begin negotiating [6], the starting negotiations benefits the pharmaceutical company, as opposed to beginning negotiations at a lower market launch price [6].

Cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) has potential applications in setting and negotiating launch prices for medications under the Inflation Reduction Act, particularly within the context of Medicare drug-price negotiations. However, a significant challenge in using quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) in economic analyses for these purposes is legislatively restricted. The Act explicitly prohibits the use of evidence from the CEA that would treat extending the life of an elderly, disabled, or terminally ill individual as of lower value than that of someone younger, nondisabled, or not terminally ill. In negotiating the “maximum fair price” for drugs, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) must consider a variety of factors, including manufacturer-specific data, such as research and development costs, production and distribution costs, federal financial support, and market data. Additionally, the CMS evaluates information about therapeutic alternatives, including the comparative effectiveness and how the selected drugs and alternatives meet the needs of specific populations, without employing QALYs.

To establish initial offers for fair prices, the CMS identifies therapeutic alternatives and uses their pricing as a starting point, adjusting based on the clinical benefits and manufacturer-specific data. This process includes a review of a wide range of evidence on clinical benefits relative to therapeutic alternatives and patient-centered outcomes. The integration of these elements in pricing discussions reflects the complex considerations involved in price negotiations that aim to balance cost with therapeutic value.

4.4. Threats to R&D

The IRA has been characterized as an impediment to the development of new therapies reimbursed through Medicare Parts B and D, while the cost of development and regulatory approval remains consistent pre- and post-IRA. The selection of potential therapies will therefore be tailored to meet the new market dynamics. While the Act provides a general description of how the MFP will be conducted, there is also a requirement that a “consistent methodology and process” be utilized [15]. This process has been hard to understand and has led to some uncertainty [15]. The long-term impact in global markets [25], such as the EU seeking similar historical discount rates from the CMS, and of private payors following the CMS methodology [18,25], could lead to long-term research and development distortion [11].

The uncertainty of the negotiated MFP will impact the future decisions made by the pharmaceutical industry, which spent USD 83 billion on R&D in 2019. [25] With a high failure rate and high costs associated with bringing a drug to market [3], the decision to proceed with research will be focused on perceived longer-term profitable projects. The effect of the IRA may influence the decision at which to proceed with early-stage assets [25], leading to higher rigor in supporting research for successful advancement.

Starting in 2026, the ten drugs first selected under the IRA will be subject to “fair market prices” (FMPs). At first, the FMPs will apply to prescription drugs under Medicare Part D, but in 2029, the FMPs will also apply to hospital-administered drugs and infusion settings outside of hospitals under Medicare Part B. These selected drugs must have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or licensed for at least seven years (eleven years for biologicals or large molecules), not compete with a generic or cheaper version, and not qualify as an orphan drug (treating a condition that affects fewer than 200,000 people). It is widely assumed the FMPs will put downward pressure on the prices of drugs outside of the IRA coverage, with prices now largely controlled by private insurers. As the IRA 2022 impacts the revenue of pharmaceutical manufacturers by reducing the FMP to a negotiated level, they will bear the burden of the cost reduction as the passthrough to pharmacies and patients within Part D. To mitigate the reduction in revenue, the pharmaceutical manufacturers would seek to isolate their product lines under the established exclusions.

Pharmaceutical companies believe the negotiations called for in the IRA will result in dictated prices, even though they are supposed to consider a drug’s clinical benefit, the extent it fills an unmet medical need, its impact on people who depend on Medicare, and the research and development costs. Companies have filed lawsuits to make the process of setting FMPs illegal as a form of price-fixing [15]. Several Constitutional issues have been raised. Meanwhile, the process of setting FMPs has already begun, and companies will have to participate in negotiation, or their drugs can be banned from use in the Medicare program.

Although patient advocates have won price controls, their success might be short-lived. Commentators have identified several unintended consequences of the IRA:

- The FMPs might discourage generic drug makers from offering knockoffs of the branded drugs, but may also increase the early access granted by the patent holder [15].

- Companies will favor biologics (large molecules) for development over small molecules because they will have longer to earn back the development costs; they will have eleven years rather than the seven years for small molecules [35].

- Companies will have incentive to set higher launch prices to recoup as much development costs as possible before the drug becomes subject to the FMP.

- Some drugs are approved by the FDA at first for use by a small group of patients, such as drugs for rare or late-stage cancers. Approval for a more general use can be delayed for several years. The period for a company to control its own prices before the drug comes under an FMP starts on the date the drug is approved by the FDA for first use. The IRA tends to encourage companies to seek approval for wider use first to maximize return.

- ○

- For example, a pharmaceutical company could postpone the launch of a drug for ovarian cancer in favor of its first approval for prostate cancer because the latter is a much larger market.

- Drug company return on investment is unpredictable, because bringing a drug to market often costs more than a billion dollars. Further billions are spent on drugs which are ultimately found ineffectual. It stands to reason that companies will reduce the overall investment out of concern for reduced income due to price controls. Already, a drug company has abandoned further development of a small-molecule cancer drug, citing the IRA as a reason [36]. The belief that drug companies make much higher profits than other companies is disputed. It depends on whether drug-development costs are treated as investments or expenses [36].

5. Conclusions

This narrative literature review has unveiled several prominent themes that underscore the multifaceted impact of the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 on the landscape of prescription drugs. Analysis of recent literature has highlighted a consistent narrative surrounding the Act’s potential to mitigate rising drug costs by implementing pricing regulations and fostering competition within the pharmaceutical market. Additionally, we identified a theme emphasizing the Act’s potential in improving the affordability and accessibility of prescription drugs for patients, addressing a critical concern in contemporary healthcare. Further examination of the literature revealed nuanced discussions regarding the Act’s role in balancing the interests of various stakeholders, including pharmaceutical companies, healthcare providers, insurers, and patients, while striving for equitable and sustainable healthcare solutions. These identified themes collectively provide crucial insights for policymakers, advocating for informed decision-making and further research to maximize the positive impact of the Inflation Reduction Act and other similar policy interventions in the healthcare sector. Further topics of inquiry and of importance, while not identified in the review, surround the implications and/or challenges with pharmacy benefit managers, the potential spillover effect of negotiated pricing on private insurance plans or hospital purchasing, as well as the potential for insurance companies to exit Medicare Part D due to the limitations on insurance premiums [37]. Future empirical studies may also be analyzed in the future to potentially align identified themes with categories of healthcare stakeholders.

As with any narrative literature review, limitations do exist. As a very current, developing topic, stakeholder perceptions of the IRA’s impact on prescription drugs will continue to change. Continuous review of the literature is required, and future study is required in this regard. Another study limitation is the lack of data-driven, empirical studies included in the review findings. However, the review topic (primarily stakeholder perceptions), industry expert opinion, and healthcare leader views required inclusion of a variety of literature beyond typical research studies.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to this review in accordance with ICMJE standards. C.L. and M.M. contributed to the investigation into the research topic. C.L., M.M., V.A. and R.B. collectively participated in the method, analysis, and original drafting of the manuscript, in addition to the initial screening and manuscript review/construct identification. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sarpatwari, A. Inflation Reduction Act and US drug pricing. Br. Med. J. 2022, 378, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, J.I. 2022 Inflation Reduction Act: Climate Investments Are Public Health Investments. Am. J. Public Health 2022, 112, 1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creighton, D. Inflation Reduction Act and the Impact on Pharmaceutical Pricing and Investment Decisions. Formulary Watch. 2022, p. 1. Available online: https://www.managedhealthcareexecutive.com/view/inflation-reduction-act-and-the-impact-on-pharmaceutical-pricing-and-investment-decisions (accessed on 25 November 2023).

- Myshko, D. Study: Heart Failure Patients Could Save with Inflation Reduction Act. Formulary Watch. 2023, p. 1. Available online: https://www.formularywatch.com/view/study-heart-failure-patients-could-save-with-inflation-reduction-act (accessed on 25 November 2023).

- Woody, N.L.; Lazarou, Y. Inflation Reduction Act Could Have Ripple Effects in Medicare Part D. Formulary Watch, 2023; 1. [Google Scholar]

- Myshko, D. Webinar: Inflation Reduction Act Will Be Positive for Medicare. Formulary Watch. 2022, p. 3. Available online: https://www.formularywatch.com/view/webinar-inflation-reduction-act-will-be-positive-for-medicare (accessed on 25 November 2023).

- Henderson, L. The Potential Impact of the IRA: Interpreting what the Inflation Reduction Act could mean for biopharma. Pharm. Exec. 2023, 43, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell, S. Inflation Reduction Act Celebration. N. J. Nurse 2022, 53, 14–15. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler, J. New Legislation Overhauls Medicare Drug Pricing, Benefits: Pharma loses battle to block price negotiations. Pharm. Exec. 2022, 42, 6. [Google Scholar]

- McAuliff, M. Inflation Reduction Act Contains Important Cost-Saving Changes for Many Patients–Maybe for You. Except. Parent 2022, 52, 8–9. [Google Scholar]

- Iskowitz, M. Pharma versus pricing, again. Med. Mark. Media 2023, 58, 58. [Google Scholar]

- Dusetzina, S.B.; Huskamp, H.A. Impending Relief for Medicare Beneficiaries–The Inflation Reduction Act. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rome, B.N.; Nagar, S.; Egilman, A.C.; Wang, J.; Feldman, W.B.; Kesselheim, A.S. Simulated Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Under the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022. JAMA Health Forum 2023, 4, e225218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, K. What U.S. hospitals and health systems can expect from the 2022 IRA. Healthc. Financ. Manag. 2022, 76, 42. [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb, S. Bringing Transparency and Rigor to Medicare Drug Pricing. JAMA Health Forum 2023, 4, e230639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narasimmaraj, P.R.; Oseran, A.; Tale, A.; Xu, J.; Essien, U.R.; Kazi, D.S.; Yeh, R.W.; Wadhera, R.K. Out-of-Pocket Drug Costs for Medicare Beneficiaries With Cardiovascular Risk Factors Under the Inflation Reduction Act. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2023, 81, 1491–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gellad, W.F.; Hernandez, I. Pharmaceutical Spending in Fee-for-Service Medicare: Looking Ahead to the Inflation Reduction Act. JAMA 2022, 328, 1502–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niazi, S.K. The Inflation Reduction Act: A boon for the generic and biosimilar industry. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2022, 47, 1738–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodwin, M.A. Assessing US Pharmaceutical Policy and Pricing Reform Legislation in Light of European Price and Cost Control Strategies. J. Health Politics Policy Law 2022, 47, 755–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, E. Federal Officials Issue Initial Guidance to Rein in Drug Spending. JAMA 2023, 329, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adashi, E.Y.; O’Mahony, D.P.; Cohen, I.G. The Inflation Reduction Act: Recasting the Medicare Prescription Drug Plans. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2023, 64, 936–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egilman, A.C.; Kesselheim, A.S.; Rome, B.N. Estimated Medicare Part B Savings From Inflationary Rebates. JAMA 2023, 329, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazi, D.; DeJong, C.; Chen, R.; Tseng, C.-W. The Inflation Reduction Act Will Change Who Pays for Cardiovascular Drugs under Medicare Part D. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. (JACC) 2023, 81, 1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazi, D.; Dejong, C.; Wadhera, R.; Chen, R.; Tseng, C.-W. Projected Impact of the Inflation Reduction Act on Out-Of-Pocket Drug Costs for Medicare Part D Beneficiaries with Cardiovascular Disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. (JACC) 2023, 81, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, S.D. Medicare Drug Price Negotiation in the United States: Implications and Unanswered Questions. Value Health 2023, 26, 394–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubl, S. Medicare Negotiation of Prescription Drug Prices. HFMA Magazine, 2022.

- Hwang, T.J.; Kesselheim, A.S.; Rome, B. N New Reforms to Prescription Drug Pricing in the US: Opportunities and Challenges. JAMA 2022, 328, 1041–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hut, N. Landmark law to curb Medicare drug prices will start to make an impact in three years. Healthc. Financ. Manag. 2022, 76, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Eisberg, N. Biotech burnout. Chem. Ind. 2022, 86, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Keith, K. Congress Extends Enhanced ACA Subsidies. Health Aff. (Proj. Hope) 2022, 41, 1542–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Yuan, J.; Lu, K. Estimates of Insulin Out-of-Pocket Cap-Associated Prescription Satisfaction, Adherence, and Affordability Among Medicare Beneficiaries. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2251208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narasimmaraj, P.; Oseran, A.; Tale, A.P.; Xu, J.; Kazi, D.; Yeh, R.W.; Wadhera, R. The Inflation Reduction Act’s Out-Of-Pocket Prescription Drug Cost Cap Will Benefit over 1 Million Medicare Patients with Cardiovascular Risk Factors or Disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. (JACC) 2023, 81, 1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. On the First Anniversary of the Inflation Reduction Act, Millions of Medicare Enrollees See Savings on Health Care Cost. 2023. Available online: https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2023/08/16/first-anniversary-inflation-reduction-act-millions-medicare-enrollees-savings-health-care-costs.html#:~:text=The%20Inflation%20Reduction%20Act's%20redesign,of%2Dpocket%20costs%20under%20the (accessed on 5 December 2023).

- Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). 35 Subsequent Measurement: Determining the Useful Life of an Intangible Asset (350-30-35). 2023. Available online: https://asc.fasb.org/1943274/2147482710 (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Fessl, S. How the IRA will Affect Drug Development. BioSpace. 2023. Available online: https://www.biospace.com/article/how-the-ira-will-affect-drug-development/ (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- A bitter pricing pill. Economist 2023, 448, 57–58.

- Carnevali, D. Reuters News Agency. 2023. Available online: https://www.reutersagency.com/en/reutersbest/article/cigna-explores-shedding-medicare-advantage-business/ (accessed on 25 November 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).