Protocol for a Pilot Randomized Controlled Mixed Methods Feasibility Trial of a Culturally Adapted Peer Support and Self-Management Intervention for African Americans

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

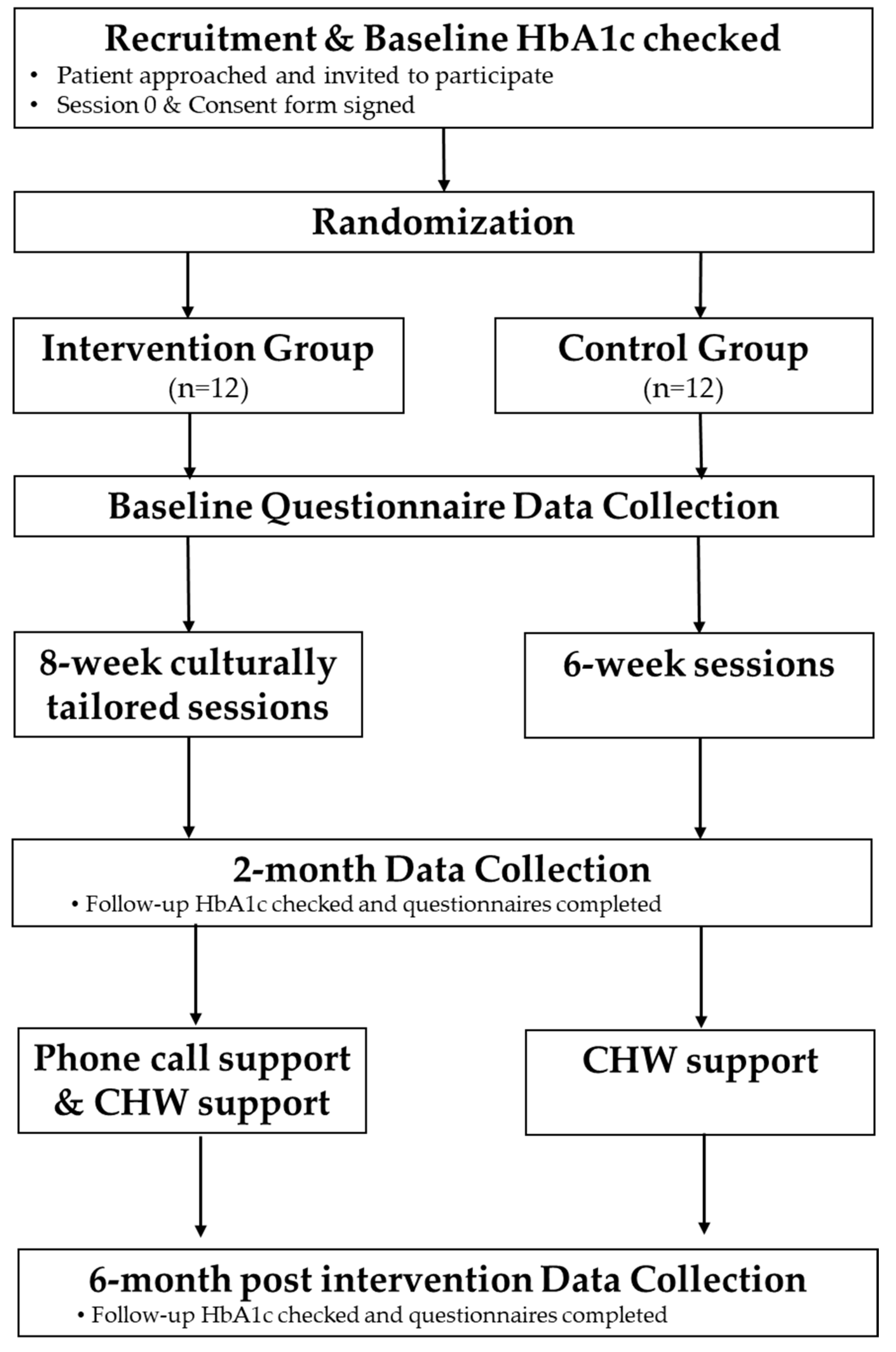

2.1. Study Objectives and Design

- (1)

- Evaluate if the intervention and protocol are feasible and acceptable. We will investigate if Peers EXCEL would be feasible to implement and be acceptable to African Americans with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes. Qualitative and quantitative data from multiple sources will be integrated to allow for meta-inferences about the feasibility of conducting a future large-scale effectiveness RCT.

- (2)

- Pilot test Peers EXCEL to examine its effect in improving A1C and medication adherence. We hypothesize a signal of change in mean hemoglobin A1c that is clinically meaningful (≥0.6 reduction) for participants randomized to Peers EXCEL compared to participants randomized to HLWD at baseline, 2 months, and 6 months. We expect to see an improvement in medication adherence, assessed via self-report in the Peers EXCEL participants compared to the HLWD participants at 6 months.

2.2. Theoretical Framework

2.3. Study Setting

2.4. Participants

2.5. Procedures

2.5.1. Participant Identification and Recruitment

2.5.2. Screening

- Participants Screening: We will implement successful strategies used in our preliminary work and prior studies [22,23,43]. Eligible participants will complete a two-step screening process: (1) preliminary phone screening—A program assistant will ask if the individual meets the eligibility criteria including having a recent A1C value that showed ≥7.5%, and then (2) point-of-care A1C test to confirm that their A1C is ≥7.5%.

- Ambassador Screening for the Peers EXCEL arm: Based on our prior successful pilot study [22,23,43], after a ambassador candidate is known, a program assistant will complete a brief preliminary ambassador candidate screening form, ask the individual if they have had recent A1C values that are ≤7.5% and then, a point of care test to evaluate their A1C will be scheduled for verification. After these screenings are completed, the PI, program assistant, and research team members will meet with the candidate to explore other important characteristics, including their communication skills, and mentoring experiences. These characteristics will help inform the research team in the matching of an ambassador to a participant.

2.5.3. The Control Arm (HLWD)

2.5.4. The Intervention Arm (Peers EXCEL)

Training of Ambassadors

2.6. Data Collection

- Surveys: A ~25 min longitudinal survey will be administered to measure self-reported medication adherence (secondary outcome) and patient-reported psychosocial factors to all participants at baseline, 2 and 6 months. The survey will be administered to each person in-person and orally during the data collection time periods, to account for people having low literacy or cognitive impairment. Surveys including reliable and validated survey questionnaires will be given to participants to assess beliefs about diabetes, self-efficacy, patient activation, and perceived quality of patient-provider communication and A1C tests at baseline, 2 months, and 6 months assessing the feasibility of gathering outcome data.

- Qualitative interview: In-person semi-structured ~25 min interviews will be conducted with all participants immediately after completing either the HLWD or Peers EXCEL group sessions and again at the end of the 6-month intervention to explore their feedback on the programs, the potential impact on changes in medication adherence and other outcomes. Participants’ inclusion and exclusion criteria will be similar to the trial. The qualitative interviews will be on-going until we reach data saturation. Sample interview questions are listed in Table 2.

- Focus groups: All ambassadors will be asked to participate in a focus group lasting 90 min which will be completed at the end the 8-week Peers EXCEL group sessions and again at the end of the intervention. Focus groups allow for a range of responses from participants compared to one-on-one interviews and ambassadors can generate new ideas and feedback for each other, which may not occur in an interview. Questions will focus on feedback about the feasibility outcomes: experiences with the process we used for recruitment, trainings they received, sustaining their participation during the Peers EXCEL intervention, and ideas for how to make the work of an ambassador easier and manageable. Sample focus group topic guide questions are listed in Table 3.

Overall program experience/benefit

|

Feedback about healthcare professional group education sessions (Intervention group only)

|

Feedback about the diabetes self-management topic sessions

|

Feedback about the interactions with Ambassadors (Intervention group only)

|

Overall program experience

|

Feedback about the HLWD sessions

|

Feedback about phone calls with Peers EXCEL participants

|

Feedback about further training and support from the research team

|

2.6.1. Measures

2.6.2. Mixed Methods Integration

2.6.3. Intervention Fidelity

2.7. Data Analysis

- Quantitative. Paired t-tests (or a non-parametric corresponding test such as Wilcoxon rank sum test) will examine pre- vs. post-intervention changes in participant’s A1C, medication adherence, and other psychosocial outcomes across groups to examine a signal of change. We will use descriptive statistics to calculate ambassadors’ feasibility measures, HLWD and Peers EXCEL participants, including ambassador recruitment, ambassador attrition, and extent of ambassador participation in sessions related to their training and intervention. We will consider the recruitment approach as feasible if: there is recruitment of all ambassadors and participants as planned, attrition for both ambassadors and participants is less than or equal to 10%, and the rate for ambassador and participant participation is equal to or higher than 80%.

- Qualitative. Interviews and focus groups will be audio-recorded and transcribed. Research assistants will code transcripts inductively using NVivo v 12 and conduct qualitative content analysis [56]. Qualitative content analysis will be used to organize the themes. All transcribed transcripts will be read initially for data immersion, taking time to read all the data line by line. Then, the codes and themes will be developed and organized with a conceptualization of how the themes are all lined together in the data. We will compare all themes exploring if there are similarities, interconnections, and/or differences across all themes. We will continue all data analysis until we get to theoretical and there are no more new dimensions in the data [57,58,59]. We will establish rigor of the data and explore the trustworthiness of the data analysis process using Lincoln and Guba (1985) four general criteria [60]. These are credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability. For credibility, two research assistants will code the transcripts independently—investigator triangulation (i.e., multiple coders involved in the data analysis), discuss similarities and divergences, and reach agreement by consensus before the final data interpretation. We will member check with participants interested in being part of the process to confirm if our interpretation is salient/credible—to check for resonance with participant experiences. Confirmability, objectivity/potential congruence between researchers. To ensure our findings are based on our participants’ responses and not any personal motivations or personal bias from our research team, after coding, all similarities and divergences will be discussed. Agreement will be reached on codes before results interpretation. Transferability, the scope to which results are applicable to other contexts. We will purposively sample individuals with varied intervention experiences and use detailed descriptions to show how the research study’s findings may be applicable in other contexts, circumstances, and situations. Dependability—the ability to achieve consistent findings if the study is done as described. We will create and report a detailed audit trail of our process throughout the analysis process. Documents and field notes data will also be analyzed using content analysis.

- Mixed. After analyzing the quantitative and qualitative data separately, the mean score differences, statistical effect sizes, and themes will be compared in the context of the feasibility, acceptability, and primary and secondary outcomes. The results from both phases will be interpreted together in a joint display to aid a meta-inference of the merged results.

3. Expected Results

3.1. Limitations

3.2. Implications and Future Research

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Getz, L. African Americans and Diabetes—Educate to Eliminate Disparities Among Minorities. Today’s Dietitian. May 2009, 11, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Perneger, T.V.; Brancati, F.L.; Whelton, P.K.; Klag, M.J. End-stage renal disease attributable to diabetes mellitus. Ann. Intern. Med. 1994, 121, 912–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health. Diabetes and African Americans. 2021. Available online: https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=4&lvlid=18 (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- Chow, E.A.; Foster, H.; Gonzalez, V.; McIver, L. The Disparate Impact of Diabetes on Racial/Ethnic Minority Populations. Clin. Diabetes 2012, 30, 130–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, I.C.; Utz, S.W.; Hinton, I.; Yan, G.; Jones, R.; Reid, K. Enhancing diabetes self-care among rural African Americans with diabetes: Results of a two-year culturally tailored intervention. Diabetes Educ. 2014, 40, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiyanbola, O.O.; Brown, C.M.; Ward, E.C. “I did not want to take that medicine”: African-Americans’ reasons for diabetes medication nonadherence and perceived solutions for enhancing adherence. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2018, 12, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, D.M.; Ponieman, D.; Leventhal, H.; Halm, E.A. Predictors of adherence to diabetes medications: The role of disease and medication beliefs. J. Behav. Med. 2009, 32, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schectman, J.M.; Nadkarni, M.M.; Voss, J.D. The association between diabetes metabolic control and drug adherence in an indigent population. Diabetes Care 2002, 25, 1015–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenolikar, R.A.; Balkrishnan, R.; Camacho, F.T.; Whitmire, J.T.; Anderson, R.T. Race and medication adherence in Medicaid enrollees with type-2 diabetes. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2006, 98, 1071–1077. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, P.M.; Rumsfeld, J.S.; Masoudi, F.A.; McClure, D.L.; Plomondon, M.E.; Steiner, J.F.; Magid, D.J. Effect of medication nonadherence on hospitalization and mortality among patients with diabetes mellitus. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1836–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, D.B.; Ragucci, K.R.; Long, L.B.; Parris, B.S.; Helfer, L.A. Relationship of oral antihyperglycemic (sulfonylurea or metformin) medication adherence and hemoglobin A1c goal attainment for HMO patients enrolled in a diabetes disease management program. J. Manag. Care Pharm. JMCP 2006, 12, 466–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozenfeld, Y.; Hunt, J.S.; Plauschinat, C.; Wong, K.S. Oral antidiabetic medication adherence and glycemic control in managed care. Am. J. Manag. Care 2008, 14, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hill-Briggs, F.; Gary, T.L.; Bone, L.R.; Hill, M.N.; Levine, D.M.; Brancati, F.L. Medication adherence and diabetes control in urban African Americans with type 2 diabetes. Health Psychol. 2005, 24, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krapek, K.; King, K.; Warren, S.S.; George, K.G.; Caputo, D.A.; Mihelich, K.; Holst, E.M.; Nichol, M.B.; Shi, S.G.; Livengood, K.B.; et al. Medication adherence and associated hemoglobin A1c in type 2 diabetes. Ann. Pharmacother. 2004, 38, 1357–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heisler, M. Overview of Peer Support Models to Improve Diabetes Self-Management and Clinical Outcomes. Diabetes Spectr. 2007, 20, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Juarez, D.T.; Yeboah, M.; Castillo, T.P. Interventions to increase medication adherence in African-American and Latino populations: A literature review. Hawai’i J. Med. Public Health 2014, 73, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, I.; Erickson, S.R.; Caldwell, C.H.; Woolford, S.J.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Chang, J.; Balkrishnan, R. Predictors of medication adherence and persistence in Medicaid enrollees with developmental disabilities and type 2 diabetes. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. RSAP 2016, 12, 592–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorig, K.; Ritter, P.L.; Ory, M.G.; Whitelaw, N. Effectiveness of a generic chronic disease self-management program for people with type 2 diabetes: A translation study. Diabetes Educ. 2013, 39, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorig, K.; Ritter, P.L.; Turner, R.M.; English, K.; Laurent, D.D.; Greenberg, J. A Diabetes Self-Management Program: 12-Month Outcome Sustainability From a Nonreinforced Pragmatic Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016, 18, e322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorig, K.; Ritter, P.L.; Villa, F.; Piette, J.D. Spanish diabetes self-management with and without automated telephone reinforcement: Two randomized trials. Diabetes Care 2008, 31, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorig, K.; Ritter, P.L.; Villa, F.J.; Armas, J. Community-based peer-led diabetes self-management: A randomized trial. Diabetes Educ. 2009, 35, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiyanbola, O.O.; Tarfa, A.; Song, A.; Sharp, L.K.; Ward, E. Preliminary Feasibility of a Peer-supported Diabetes Medication Adherence Intervention for African Americans. Health Behav. Policy Rev. 2019, 6, 558–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiyanbola, O.O.; Maurer, M.; Schwerer, L.; Sarkarati, N.; Wen, M.J.; Salihu, E.Y.; Nordin, J.; Xiong, P.; Egbujor, U.M.; Williams, S.D. A Culturally Tailored Diabetes Self-Management Intervention Incorporating Race-Congruent Peer Support to Address Beliefs, Medication Adherence and Diabetes Control in African Americans: A Pilot Feasibility Study. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2022, 2022, 2893–2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiyanbola, O.O.; Ward, E.C.; Brown, C.M. Utilizing the common sense model to explore African Americans’ perception of type 2 diabetes: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0207692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiyanbola, O.O.; Ward, E.; Brown, C. Sociocultural Influences on African Americans’ Representations of Type 2 Diabetes: A Qualitative Study. Ethn. Dis. 2018, 28, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, E.B.; Chou, W.S.; Rising, C.; Gaysynsky, A. The Role and Impact of Health Literacy on Peer-to-Peer Health Communication. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2020, 269, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salud, M.A.; Gallardo, J.I.; Dineros, J.A.; Gammad, A.F.; Basilio, J.; Borja, V.; Iellamo, A.; Worobec, L.; Sobel, H.; Olivé, J.M. People’s initiative to counteract misinformation and marketing practices: The Pembo, Philippines, breastfeeding experience, 2006. J. Hum. Lact. 2009, 25, 341–349; quiz 362–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins-McNeil, J.; Edwards, C.L.; Batch, B.C.; Benbow, D.; McDougald, C.S.; Sharpe, D. A culturally targeted self-management program for African Americans with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Can. J. Nurs. Res. 2012, 44, 126–141. [Google Scholar]

- Peña-Purcell, N.C.; Jiang, L.; Ory, M.G.; Hollingsworth, R. Translating an evidence-based diabetes education approach into rural african-american communities: The “wisdom, power, control” program. Diabetes Spectr. 2015, 28, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel-Hodge, C.D.; Keyserling, T.C.; France, R.; Ingram, A.F.; Johnston, L.F.; Pullen Davis, L.; Davis, G.; Cole, A.S. A church-based diabetes self-management education program for African Americans with type 2 diabetes. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2006, 3, A93. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, M.J.; Maurer, M.; Schwerer, L.; Sarkarati, N.; Egbujor, U.M.; Nordin, J.; Williams, S.D.; Liu, Y.; Shiyanbola, O.O. Perspectives on a Novel Culturally Tailored Diabetes Self-Management Program for African Americans: A Qualitative Study of Healthcare Professionals and Organizational Leaders. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Clark, V.L.P. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; Sage publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, D.; Shiyanbola, O.O. Best practices for conducting and writing mixed methods research in social pharmacy. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. RSAP 2022, 18, 2184–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byer, B.; Myers, L.B. Psychological correlates of adherence to medication in asthma. Psychol Health Med. 2000, 5, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horne, R.; Weinman, J. Patients’ beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness. J. Psychosom. Res. 1999, 47, 555–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jörgensen, T.M.; Andersson, K.A.; Mårdby, A.C. Beliefs about medicines among Swedish pharmacy employees. Pharm. World Sci. PWS 2006, 28, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, C.; Battista, D.R.; Bruehlman, R.; Sereika, S.S.; Thase, M.E.; Dunbar-Jacob, J. Beliefs About Antidepressant Medications in Primary Care Patients: Relationship to Self-Reported Adherence. Med. Care 2005, 43, 1203–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horne, R.; Weinman, J. Self-regulation and Self-management in Asthma: Exploring The Role of Illness Perceptions and Treatment Beliefs in Explaining Non-adherence to Preventer Medication. Psychol Health 2002, 17, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.; Walker, A.; MacLeod, M.J. Patient compliance in hypertension: Role of illness perceptions and treatment beliefs. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2004, 18, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misovich, S.J.; Martinez, T.; Fisher, J.D.; Bryan, A.; Catapano, N. Predicting Breast Self-Examination: A Test of the Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills Model1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 33, 775–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, W.A.; Fisher, J.D.; Harman, J. The Information–Motivation–Behavioral skills model as a general model of health behavior change: Theoretical approaches to individual-level change. In Social Psychological Foundations of Health; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 127–153. [Google Scholar]

- Osborn, C.Y. Using the IMB Model of Health Behavior Change to Promote Self-Management Behaviors in Puerto Ricans with Diabetes; University of Connecticut: Storrs, CT, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Shiyanbola, O.O.; Maurer, M.; Ward, E.C.; Sharp, L.; Lee, J.; Tarfa, A. Protocol for partnering with peers intervention to improve medication adherence among African Americans with Type 2 Diabetes. medRxiv, 2020; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, M.A.; Shiyanbola, O.O.; Mott, M.L.; Means, J. Engaging Patient Advisory Boards of African American Community Members with Type 2 Diabetes in Implementing and Refining a Peer-Led Medication Adherence Intervention. Pharmacy 2022, 10, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiyanbola, O.O.; Kaiser, B.L.; Thomas, G.R.; Tarfa, A. Preliminary engagement of a patient advisory board of African American community members with type 2 diabetes in a peer-led medication adherence intervention. Res. Involv. Engagem. 2021, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornelius, T.; Voils, C.I.; Umland, R.C.; Kronish, I.M. Validity Of The Self-Reported Domains Of Subjective Extent Of Nonadherence (DOSE-Nonadherence) Scale In Comparison With Electronically Monitored Adherence To Cardiovascular Medications. Patient Prefer Adherence 2019, 13, 1677–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voils, C.I.; King, H.A.; Thorpe, C.T.; Blalock, D.V.; Kronish, I.M.; Reeve, B.B.; Boatright, C.; Gellad, Z.F. Content Validity and Reliability of a Self-Report Measure of Medication Nonadherence in Hepatitis C Treatment. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2019, 64, 2784–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broadbent, E.; Petrie, K.J.; Main, J.; Weinman, J. The brief illness perception questionnaire. J. Psychosom. Res. 2006, 60, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.M.; Funnell, M.M.; Fitzgerald, J.T.; Marrero, D.G. The Diabetes Empowerment Scale: A measure of psychosocial self-efficacy. Diabetes Care 2000, 23, 739–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Risser, J.; Jacobson, T.A.; Kripalani, S. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Self-efficacy for Appropriate Medication Use Scale (SEAMS) in low-literacy patients with chronic disease. J. Nurs. Meas. 2007, 15, 203–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, L.; Glasgow, R.E.; Mullan, J.T.; Skaff, M.M.; Polonsky, W.H. Development of a brief diabetes distress screening instrument. Ann. Fam. Med. 2008, 6, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerman, C.E.; Brody, D.S.; Caputo, G.C.; Smith, D.G.; Lazaro, C.G.; Wolfson, H.G. Patients’ Perceived Involvement in Care Scale: Relationship to attitudes about illness and medical care. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 1990, 5, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibbard, J.H.; Stockard, J.; Mahoney, E.R.; Tusler, M. Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): Conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv. Res. 2004, 39, 1005–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Innovation Program. Improving Diabetes Self-Management. Available online: https://hip.wisc.edu/hlwd (accessed on 6 November 2022).

- Wisconsin Institute for Health Aging. Healthy Living with Diabetes. Available online: https://wihealthyaging.org/programs/live-well-programs/hlwd/ (accessed on 6 November 2022).

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K.; Belgrave, L.L. The SAGE Handbook of Interview Research: The Complexity of the Craft, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pope, C.; Ziebland, S.; Mays, N. Qualitative research in health care. Analysing qualitative data. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed.) 2000, 320, 114–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, L. Handling Qualitative Data: A Practical Guide; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2020; pp. 1–336. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, Y.S.L.E.G.; Guba, E.G.; Publishing, S. Naturalistic Inquiry; SAGE Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

| Intervention Content | Weeks | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 14 | 19 | 24 | |

| Group sessions of beliefs about diabetes, provider mistrust and pharmacist communication | * | * | ||||||||||

| Group sessions of diabetes self-management, healthy eating, problem solving, exercise, communication, medication, cultural experiences, discussing diabetes with family | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||

| # | # | # | # | # | # | |||||||

| Referral to community health worker, if requested | * | * | * | * | ||||||||

| # | # | # | # | |||||||||

| Peer-based phone call support | * | * | * | * | ||||||||

| Construct | Measure | Baseline | 2 Months | 6 Months |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Clinical Outcome | ||||

| Blood glucose | Hemoglobin A1c (A1C) | × | × | × |

| Secondary Study Outcome | ||||

| Medication adherence | DOSE-Nonadherence survey [46,47], extent of nonadherence domain | × | × | × |

| Other Measures | ||||

| Diabetes-health beliefs | Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire [48] | × | × | × |

| Beliefs about diabetes medicines | Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire [35] | × | × | × |

| Diabetes and medication self-efficacy | Diabetes Empowerment Scale—Short Form [49] Self-Efficacy for Adherence to Medication Use Scale [50] | × | × | × |

| Diabetes distress | Diabetes Distress Scale (DDS-2) [51] | |||

| Patient-provider communication | Patient’s Perceived Involvement in Care Scale [52] | × | × | × |

| Patient activation | Patient Activation Measure [53] | × | × | × |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shiyanbola, O.O.; Maurer, M.; Wen, M.-J. Protocol for a Pilot Randomized Controlled Mixed Methods Feasibility Trial of a Culturally Adapted Peer Support and Self-Management Intervention for African Americans. Pharmacy 2023, 11, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy11010002

Shiyanbola OO, Maurer M, Wen M-J. Protocol for a Pilot Randomized Controlled Mixed Methods Feasibility Trial of a Culturally Adapted Peer Support and Self-Management Intervention for African Americans. Pharmacy. 2023; 11(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy11010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleShiyanbola, Olayinka O., Martha Maurer, and Meng-Jung Wen. 2023. "Protocol for a Pilot Randomized Controlled Mixed Methods Feasibility Trial of a Culturally Adapted Peer Support and Self-Management Intervention for African Americans" Pharmacy 11, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy11010002

APA StyleShiyanbola, O. O., Maurer, M., & Wen, M.-J. (2023). Protocol for a Pilot Randomized Controlled Mixed Methods Feasibility Trial of a Culturally Adapted Peer Support and Self-Management Intervention for African Americans. Pharmacy, 11(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy11010002