Birth Control Use and Access Including Pharmacist-Prescribed Contraception Services during COVID-19

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Survey Development

2.3. Community Pharmacy Recruitment and Survey Distribution

2.4. Electronic Survey Distribution

2.5. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Survey Respondents

3.2. COVID-19 Pandemic Impact

3.2.1. COVID-19 Diagnosis

3.2.2. Substance Use

3.2.3. Employment

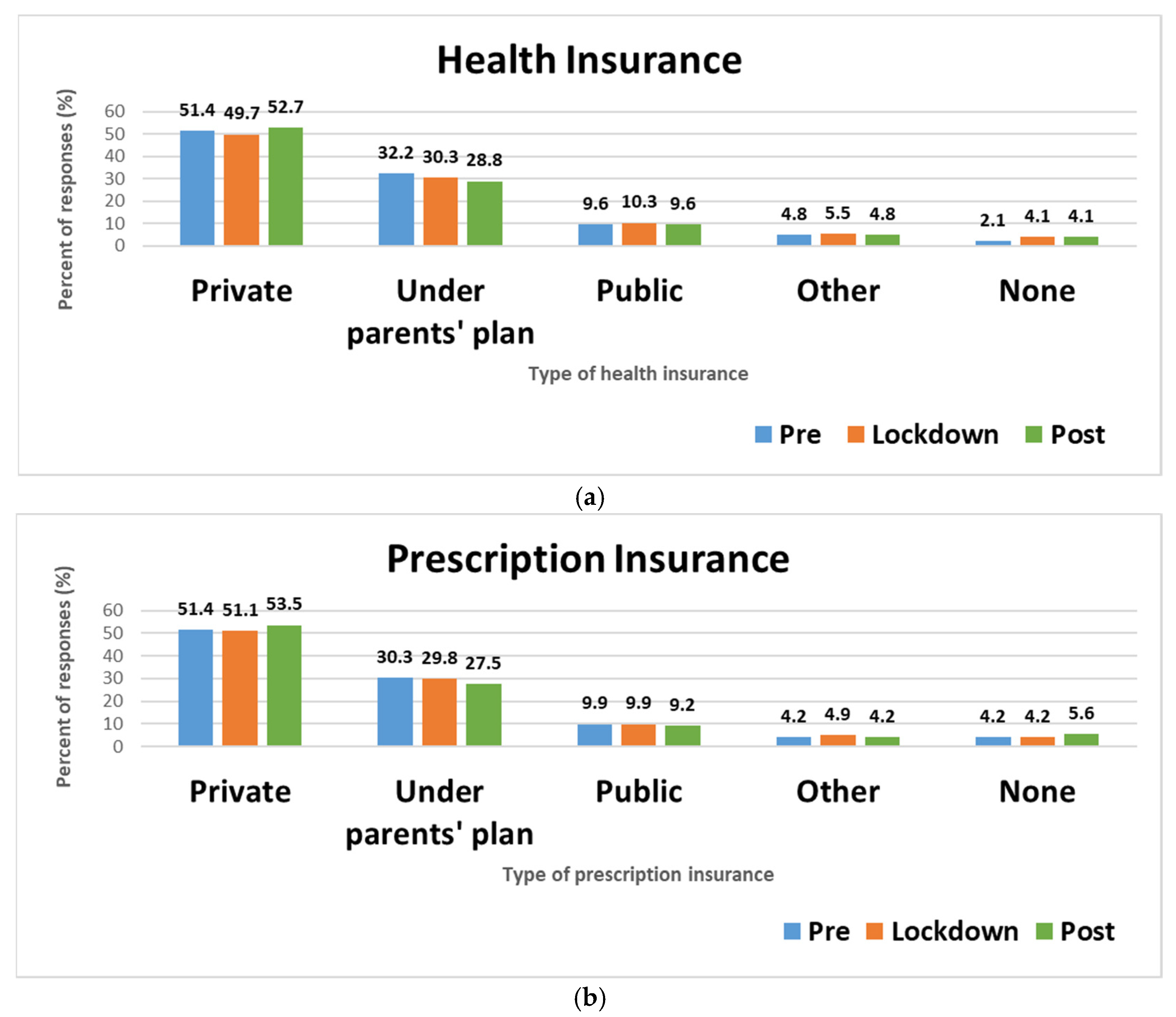

3.2.4. Insurance

3.2.5. Sexual Activity and Pregnancy Worries

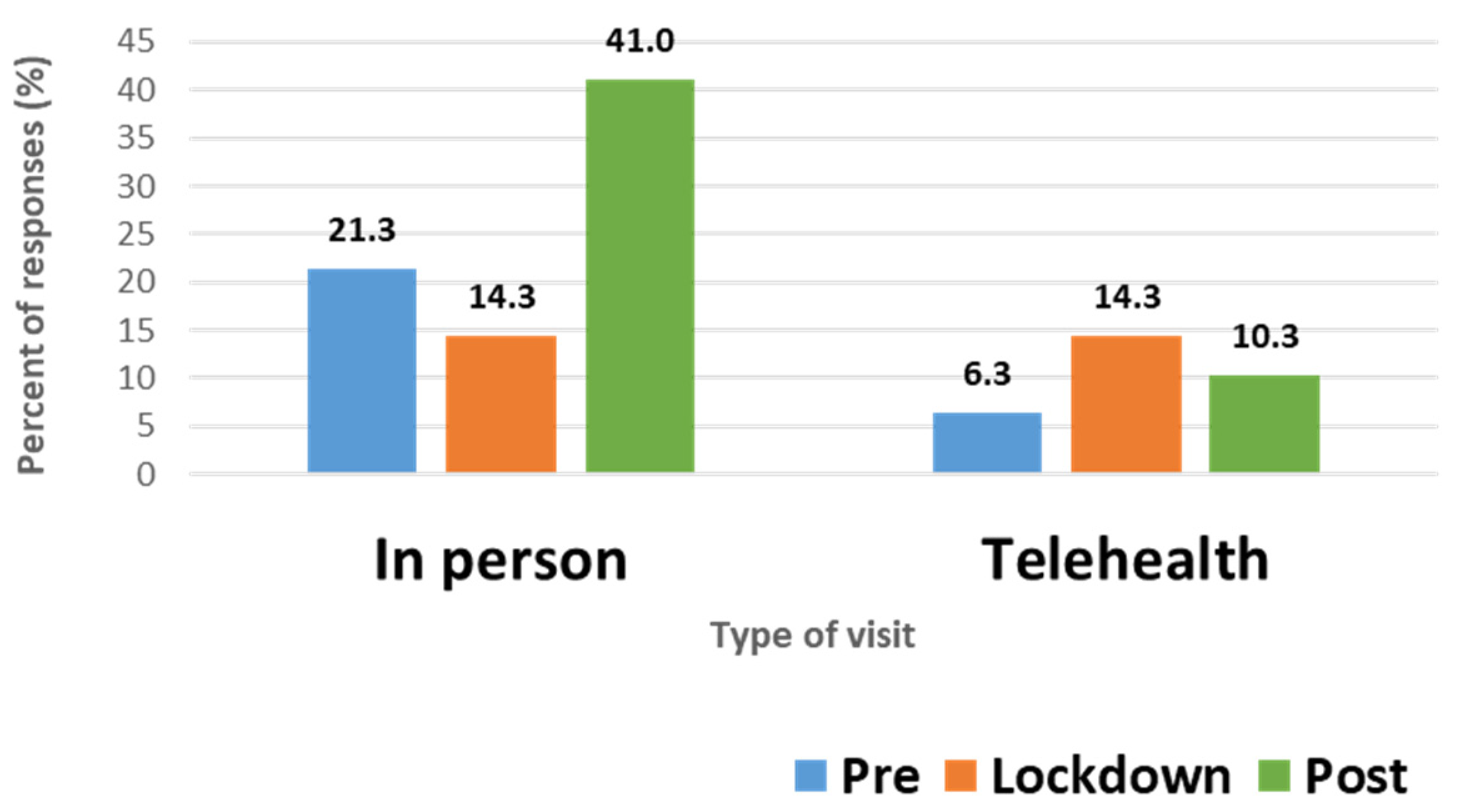

3.2.6. Prescription BC Use and Access

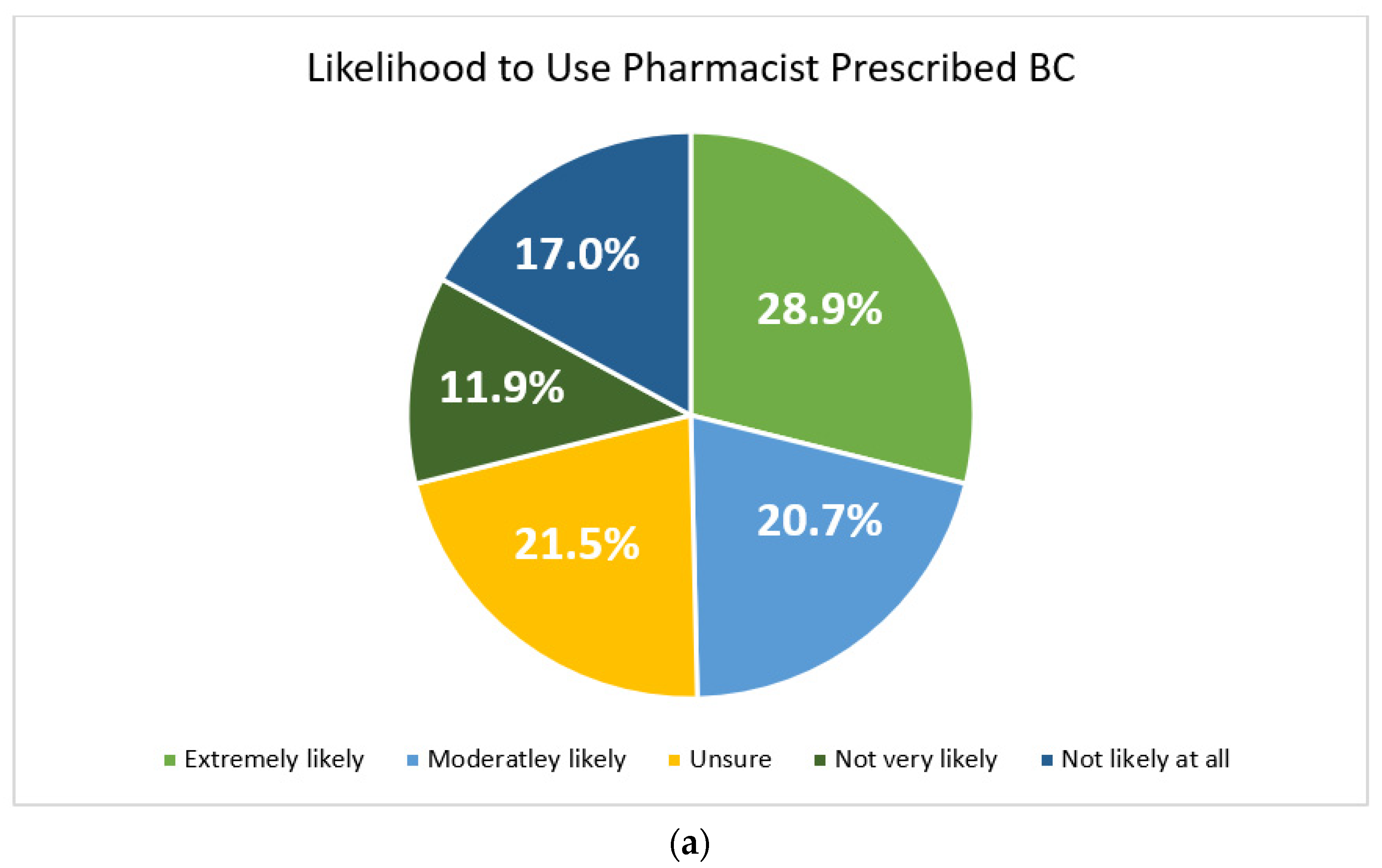

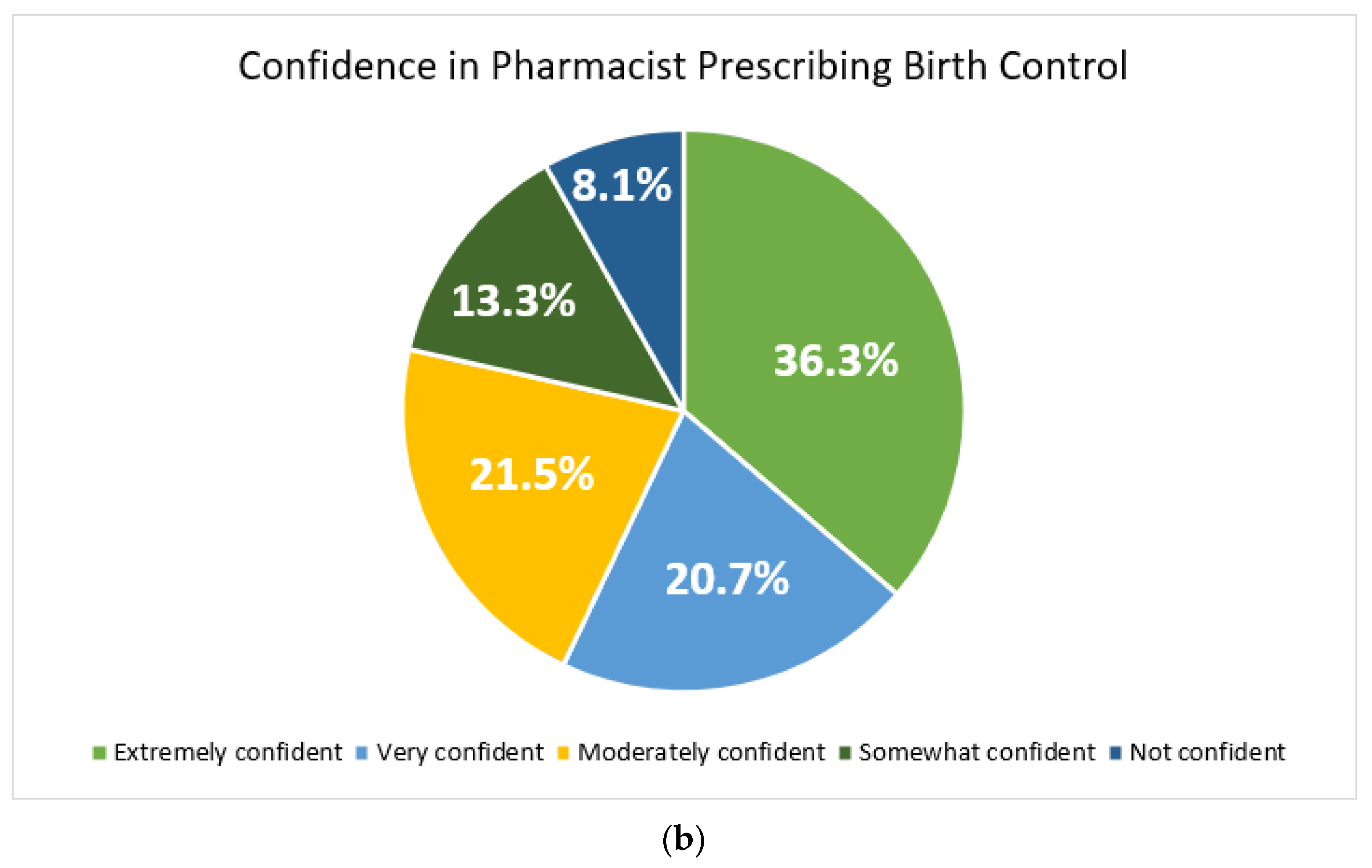

3.3. Perceptions of Pharmacist-Prescribed BC Captured during Pandemic

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schrager, S.; Larson, M.; Carlson, J.; Ledford, K.; Ehrenthal, D.B. Beyond birth control: Noncontraceptive benefits of hormonal methods and their key role in the general medical care of women. J. Women’s Health 2020, 29, 937–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finer, L.; Zolna, M. Declines in unintended pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 843–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gipson, J.; Koenig, M.; Hindin, M. The effects of unintended pregnancy on infant, child, and parental health: A review of the literature. Stud. Fam. Plan. 2008, 39, 18–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women. Available online: http://acog.org/-/media/project/acog/acogorg/clinical/files/committee-opinion/articles/2015/01/access-to-contraception.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2022).

- Guttmacher Institute. Available online: https://www.guttmacher.org/report/public-costs-unintended-pregnancies-and-role-public-insurance-programs-paying-pregnancy (accessed on 5 August 2022).

- Bryant, A.; Speizer, I.; Hodgkinson, J.C.; Swiatlo, A.; Curtis, S.L.; Perreira, K. Contraceptive practices, preferences, and barriers among abortion clients in North Carolina. South. Med. J. 2018, 111, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Center for Young Women’s Health. Available online: https://youngwomenshealth.org/2011/10/18/medical-uses-of-the-birth-control-pill/ (accessed on 5 August 2022).

- Lindberg, L.; Bell, D.; Kantor, L. The sexual and reproductive health of adolescents and young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Perspect. Sex Reprod. Health 2020, 52, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttmacher Institute. Available online: https://www.guttmacher.org/report/early-impacts-covid-19-pandemic-findings-2020-guttmacher-survey-reproductive-health# (accessed on 5 August 2022).

- Kavanaugh, M.L.; Pleasure, Z.H.; Pliskin, E.; Zolna, M.; MacFarlane, K. Financial instability and delays in access to sexual and reproductive health care due to COVID-19. J. Women’s Health 2022, 31, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fyfe, S. US women’s sexual and reproductive health trends. Contemp. OB/GYN 2021, 66, 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Keiser Family Foundation. Available online: https://www.kff.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Webinar-Slides-WHP-4.21.21.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2022).

- Ott, M.; Bernard, C.; Wilkinson, T.; Edmonds, B. Clinician perspectives on ethics and COVID-19: Minding the gap in sexual and reproductive health. Perspect. Sex Reprod. Health 2020, 52, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, S.; Samari, G. COVID-19 and immigrants’ access to sexual and reproductive health services in the United States. Perspect. Sex Reprod. Health 2020, 52, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, I.; Bader, L.R.; Galbraith, K. A global survey on trends in advanced practice and specialization in the pharmacy workforce. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2020, 28, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goode, J.V.; Owen, J.; Page, A.; Gatewood, S. Community-based pharmacy practice innovation and the role of the community-based pharmacist practitioner in the United States. Pharmacy 2019, 7, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, K.E.; Schindel, T.J.; Barsoum, M.E.; Kung, J.Y. COVID the catalyst for evolving professional role identity? A scoping review of global pharmacists’ roles and services as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Pharmacy 2021, 9, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baroy, J.; Chung, D.; Frisch, R.; Apgar, D.; Slack, M.K. The impact of pharmacist immunization programs on adult immunization rates: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2016, 56, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burson, R.C.; Buttenheim, A.M.; Armstrong, A.; Feemster, K.A. Community pharmacies as sites of adult vaccination: A systematic review. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2016, 12, 3146–3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.J.; Todd, A.; O’Malley, C.; Moore, H.J.; Husband, A.K.; Bambra, C.; Kasim, A.; Sniehotta, F.F.; Steed, L.; Smith, S.; et al. Community pharmacy-delivered interventions for public health priorities: A systematic review of interventions for alcohol reduction, smoking cessation and weight management, including meta-analysis for smoking cessation. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e009828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiazor, E.I.; Evans, M.; van Woerden, H.; Oparah, A.C. A systematic review of community pharmacists’ interventions in reducing major risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Value Health Reg. 2015, 7, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, K.; Bach, A.; Won, K.; Seed, S.M. Community pharmacists’ roles during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Pharm. Pract. 2022, 35, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San-Juan-Rodriguez, A.; Newman, T.; Hernandez, I.; Swart, E.C.; Klein-Fedyshin, M.; Shrank, W.H.; Parekh, N. Impact of community pharmacist-provided preventive services on clinical, utilization, and economic outcomes: An umbrella review. Prev. Med. 2018, 115, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agomo, C.O. The role of community pharmacists in public health: A scoping review of the literature. J. Pharm. Health Serv. Res. 2012, 3, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, M.I.; Edelmn, A.B.; Skye, M.; Darney, B.G. Reasons for and experience in obtaining pharmacist-prescribed contraception. Contraception 2020, 102, 259–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, A.N.; Stewart, O.C.; Nguyen, V.Q.; Bzowyckyj, A.S. Public perception of pharmacist-prescribed self-administered non-emergency hormonal contraception: An analysis of online social discourse. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2019, 15, 650–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckhaus, L.M.; Ti, A.J.; Curtis, K.M.; Stewart-Lynch, A.L.; Whiteman, M.K. Patient and pharmacist perspectives on pharmacist-prescribed contraception: A systematic review. Contraception 2021, 103, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Power to Decide. Available online: https://powertodecide.org/what-we-do/information/resource-library/pharmacist-prescribing-hormonal-birth-control (accessed on 5 August 2022).

- Gardner, J.; Downing, D.; Blough, D.; Miller, L.; Le, S.; Shotorbani, S. Pharmacist prescribing of hormonal contraceptives: Results of the direct access study. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2008, 48, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connell, M.B.; Samman, L.; Bailey, T.; King, L.; Wellman, G. Attitudes of Michigan female college students about pharmacists prescribing birth control in a community pharmacy. Pharmacy 2020, 8, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, A.M.; Rafie, S.; Garner-Ford, E.; Arcara, J.; Arteaga, S.; Britter, M.; De La Cruz, M.; Gleaton, S.K.; Gomez-Vidal, C.; Luna, B.; et al. Community perspectives on pharmacist-prescribed hormonal contraception in rural California. Contraception 2022, 22, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafie, S.; Wollum, A.; Grindlay, K. Patient experiences with pharmacist prescribed hormonal contraception in California independent and chain pharmacies. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2022, 62, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, N.; Rafie, S.; Bull, S.T.; Mody, S.K. Access to contraception in pharmacies during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2021, 61, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anusha, A.; Savannah, K.; Futterman, I.D.; Clare, C.A. Access to family planning services following natural disasters and pandemics: A review of the english literature. Cureus 2022, 14, e26926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etikan, I.; Alkassim, R.; Abubakar, S. Comparison of snowball sampling and sequential sampling technique. Biom. Biostat. Int. J. 2015, 3, 00055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manze, M.; Romero, D.; Johnson, G.; Pickering, S. Factors related to delays in obtaining contraception among pregnancy-capable adults in New York state during the COVID-19 pandemic: The CAP study. Sex. Reprod. Healthc. 2022, 31, 100697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenland, M.W.; Geiger, C.K.; Chen, L.; Rokicki, S.; Gourevitch, R.A.; Sinaiko, A.D.; Cohen, J.L. Declines in contraceptive visits in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. Contraception 2021, 104, 593–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.E.; Lai, A.Y.; Gupta, A.; Nguyen, A.M.; Berry, C.A.; Shelley, D.R. Rapid transition to telehealth and the digital divide: Implications for primary care access and equity in a post-COVID era. Milbank Q. 2021, 99, 340–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leon-Larios, F.; Isabel, S.R.; Isabel, L.P.; Quílez Conde, J.C.; Puente Martínez, M.J.; Gutiérrez Ales, J.; Correa Rancel, M. Women’s access to sexual and reproductive health services during confinement due to the COVID-19 pandemic in spain. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berenbrok, L.A.; Gabriel, N.; Coley, K.C.; Hernandez, I. Evaluation of frequency of encounters with primary care physicians vs visits to community pharmacies among Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e209132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- USPharmacist. Available online: https://www.uspharmacist.com/article/pharmacists-prescribing-hormonal-contraceptives-a-status-update (accessed on 12 October 2022).

| Characteristic | No. of Respondents n = 147 | No. of Respondents Likely to Use Pharmacist-Prescribed BC n = 132–135 e,f | p Value g |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) a | 0.564 | ||

| 18–25 | 49 (34.3%) | 26 (57.8%) | |

| 26–31 | 44 (30.8%) | 18 (42.9%) | |

| 32–45 | 50 (35.0%) | 21 (46.7%) | |

| Race | 0.301 | ||

| White | 114 (77.6%) | 53 (50.5%) | |

| More than one race | 15 (10.2%) | 5 (38.5%) | |

| American Indian | 8 (5.4%) | 3 (42.9%) | |

| Black | 7 (4.8%) | 3 (42.9%) | |

| Asian | 3 (2.0%) | 3 (100%) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.148 | ||

| Hispanic/Latinx | 13 (8.8%) | 9 (69.2%) | |

| Arab/Middle Eastern | 4 (2.7%) | 1 (25.0%) | |

| Sexual orientation | 0.235 | ||

| Heterosexual | 119 (81.0%) | 52 (47.7%) | |

| LBTQ+ | 28 (19.0%) | 15 (57.7%) | |

| Michigan location | 0.204 | ||

| Southeastern | 76 (51.7%) | 32 (47.1%) | |

| Midwestern | 35 (23.8%) | 17 (50.0%) | |

| Northern lower peninsula | 18 (12.2%) | 11 (68.8%) | |

| Upper peninsula | 15 (10.2%) | 7 (46.7%) | |

| Southwestern | 3 (2.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Education | 0.479 | ||

| High school or less | 14 (9.5%) | 4 (33.3%) | |

| Some college/Associate degree | 44 (29.9%) | 21 (52.5%) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 54 (36.7%) | 25 (50.0%) | |

| Graduate degree | 35 (23.8%) | 17 (51.5%) | |

| Religion b | 0.975 | ||

| Christianity | 82 (56.1%) | 36 (46.8%) | |

| Agnostic | 23 (15.7%) | 11 (55.0%) | |

| Atheist | 15 (10.3%) | 7 (50.0%) | |

| Other | 26 (17.8%) | 12 (52.2%) | |

| Political party | 0.532 | ||

| Democrat | 68 (46.3%) | 34 (53.1%) | |

| Republican | 32 (21.8%) | 14 (48.3%) | |

| None | 27 (18.4%) | 10 (41.7%) | |

| Independent | 16 (10.9%) | 7 (50.0%) | |

| Prefer not to answer | 4 (2.7%) | 2 (50.0%) | |

| Income | 0.515 | ||

| Less than $20,000 | 40 (27.2%) | 19 (52.8%) | |

| $20,000 to $34,999 | 27 (18.4%) | 12 (48.0%) | |

| $35,000 to $49,999 | 25 (17.0%) | 13 (54.2%) | |

| $50,000 to $74,999 | 24 (16.3%) | 11 (47.8%) | |

| $75,000 to $99,999 | 7 (4.8%) | 2 (28.6%) | |

| Over 100,000 | 24 (16.3%) | 10 (50.0%) | |

| Living situation | 0.237 | ||

| Living with partner/spouse | 79 (53.7%) | 31 (41.9%) | |

| Living with parent/guardian | 29 (19.7%) | 13 (52.0%) | |

| Living on own | 20 (13.6%) | 11 (61.1%) | |

| Living with roommates | 14 (9.5%) | 9 (69.2%) | |

| Other | 5 (3.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Relationship status | 0.185 | ||

| Married to man | 56 (38.1%) | 21 (41.2%) | |

| Single, long-term relationship | 41 (27.9%) | 21 (55.3%) | |

| Single, not dating | 22 (15.0%) | 11 (55.0%) | |

| Single, dating/short term relationship | 19 (12.9%) | 12 (66.7%) | |

| Other | 9 (6.2%) | 2 (25.0%) | |

| Use prescription birth control c | 0.136 | ||

| Yes | 85 (57.8%) | 45 (55.6%) | |

| No | 52 (39.1%) | 22 (42.3%) | |

| BC formulation d | 0.402 | ||

| Oral pill | 65 (76.4%) | 36 (59.0%) | |

| IUD | 15 (17.6%) | 6 (40.0%) | |

| Other | 5 (5.9%) | 3 (50.0%) | |

| Reason for birth control d | |||

| Prevent pregnancy | 72 (83.7%) | 29 (43.9%) | <0.001 |

| Menstrual problems | 42 (48.8%) | 16 (43.2%) | <0.001 |

| Acne | 21 (24.0%) | 7 (38.9%) | <0.001 |

| PCOS | 13 (15.1%) | 8 (66.7%) | 0.046 |

| Lockdown Compared to Pre-Lockdown N = 147 (%) | Post-Lockdown Compared to Lockdown N = 136 (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Decreased a | ||

| Social distancing | 27 (18.4%) | 9 (6.6%) |

| Had COVID-19 | 6 (4.1%) | 4 (2.9%) |

| No privacy | 11 (7.5%) | 7 (5.1%) |

| Other | 15 (10.2%) | 16 (11.8%) |

| Increased a | ||

| More time with same partner | 26 (17.7%) | 23 (16.9%) |

| More time with multiple partners | 7 (4.8%) | 7 (5.1%) |

| Other | 0 (0.0%) | 8 (5.9%) |

| No change | 59 (40.1%) | 63 (46.3%) |

| Advantages | Number Respondents (%); n = 147 | Concerns | Number Respondents n = 147 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| More convenient | 104 (70.7%) | Not receive PAP smears/screenings | 89 (60.5%) |

| Easier access | 102 (69.4%) | Prescribed wrong birth control | 46 (31.3%) |

| Save time | 99 (67.3%) | Encourage sex earlier | 23 (15.6%) |

| Obtain prescription and fill at same time | 96 (65.3%) | Pharmacists lack knowledge | 20 (13.6%) |

| More accessible hours | 88 (59.9%) | Pharmacists lack skills | 15 (10.2%) |

| Less likely to run out of birth control | 81 (55.1%) | ||

| Less costly than provider visit | 80 (54.4%) | ||

| Greater confidentiality | 26 (17.7%) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pelaccio, K.; Bright, D.; Dillaway, H.; O’Connell, M.B. Birth Control Use and Access Including Pharmacist-Prescribed Contraception Services during COVID-19. Pharmacy 2022, 10, 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy10060142

Pelaccio K, Bright D, Dillaway H, O’Connell MB. Birth Control Use and Access Including Pharmacist-Prescribed Contraception Services during COVID-19. Pharmacy. 2022; 10(6):142. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy10060142

Chicago/Turabian StylePelaccio, Karli, David Bright, Heather Dillaway, and Mary Beth O’Connell. 2022. "Birth Control Use and Access Including Pharmacist-Prescribed Contraception Services during COVID-19" Pharmacy 10, no. 6: 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy10060142

APA StylePelaccio, K., Bright, D., Dillaway, H., & O’Connell, M. B. (2022). Birth Control Use and Access Including Pharmacist-Prescribed Contraception Services during COVID-19. Pharmacy, 10(6), 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy10060142