A Narrative Review of Studies Comparing Efficacy and Safety of Citalopram with Atypical Antipsychotics for Agitation in Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia (BPSD)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Prevalence and Incidence of Dementia around the World

1.2. Phenomenology of Dementia

1.3. Dementia Classification

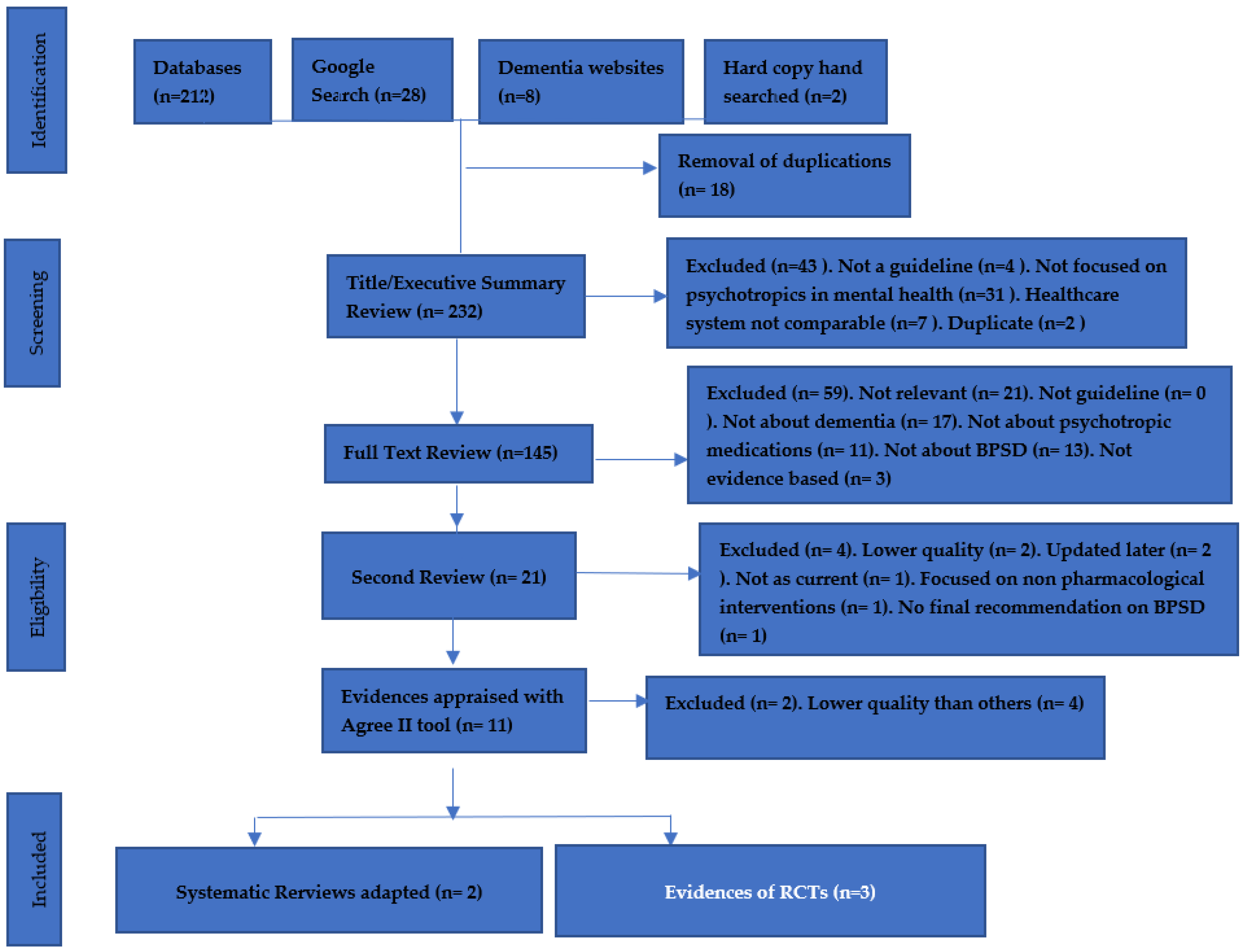

2. Materials and Methods

- Published in the English language;

- Randomized controlled trials RCTs, both experimental and non-experimental studies, non-RCTs, non-randomized (quasi-experimental) studies, observational, retrospective and prospective cohort studies, and analytical and cross-sectional studies;

- Published in peer-reviewed journals;

- Included any type of dementia and any level of severity in any setting;

- Focused on treatment and management of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (included agitation, psychosis, and aggression);

- Included pharmacological interventions, compared different kinds of pharmacological interventions or compared to placebo;

- Included the outcomes of the pharmacological interventions or adverse effects.

- Any study focused on non-pharmacological interventions only;

- Studies focused on non-dementia population, such as health professionals or care givers;

- Low level of evidence, such as case reports, study protocols, commentaries, or design interventions;

- Population aged 17 years old or younger;

- Paper of other mental health or psychiatric disorders (not including dementia).

- Were written in English;

- Focused on all types of dementia;

- Focused on the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD);

- Presented recommendations in regard to agitation, psychosis, and aggressive behaviors;

- Were established in developed countries with reputable healthcare systems.

3. Results

3.1. Description of Systematic Reviews

3.2. Description of Randomized Controlled Trials

4. Discussion

4.1. Quality of Evidence

Methodological Quality of the Systematic Reviews

4.2. Methodological Quality of Most Recent Trials

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Exploding captures lower branches including behavioural symptoms/ |

| Two different MeSH terms used |

| NB: One MeSH terms used |

| Three different MeSH terms used |

| Proximity search |

| |

| Will find papers using ANY of those Population MeSH terms/free-text phrases |

| For papers covering all PICO components |

| For papers covering all PICO components |

| For papers covering all PICO components |

| |

| For papers covering all PICO components |

| |

| |

| For papers covering all PICO components |

| Dementia Type | Definition |

|---|---|

| Alzheimer’s disease | The most common type of dementia, making up 60% to 80% of dementia cases. In the early stages, it is often characterized by symptoms including: difficulty remembering recent conversations, names, and events, apathy, and depression. In late stages, symptoms usually progress to: impaired communication, disorientation, confusion, poor judgment, behavioral and psychological changes, difficulty of speech and swallowing, and decline in both fine and gross motor skills, including walking [33]. Alzheimer’s has been linked to genetic mutations found in three genes which can be passed down from parent to child, with one important gene that increases the risk of Alzheimer’s called E4 (APOE). The hallmark pathologies of Alzheimer’s disease are the accumulation of a beta-amyloid fragment protein called plaques outside neurons of the brain and twisted strands called tangles (tau protein) inside neurons. These accumulations and changes cause the death of neurons and damage to brain tissue. Recent large autopsy studies showed that more than half of individuals with Alzheimer’s dementia have associated simultaneous cerebrovascular diseases and Lewy’s body diseases [33]. |

| Vascular dementia | Vascular dementia is so named as it is the result of various combinations of chronic and acute cerebrovascular conditions and incidents that have a cumulative effect on cognition. About 5–10% of individuals with dementia showed evidence of vascular diseases. Cerebrovascular dementia can be denoted when the blood vessels in the brain are damaged and brain tissue is injured from not receiving enough blood, nutrition, and oxygen. Vascular dementia occurs commonly in blood vessel blockage, such as stroke or vascular damage, leading to areas of dead tissue in the brain or bleeding in the brain. The severity and nature of this kind of dementia will depend on the location, number of locations, and severity of each injury. These injuries cause adverse effects to the individual’s thinking and physical functioning, often causing impaired judgment or impaired ability to make decisions and plan, impaired organization skills, and poor memory, which are the major signs of vascular dementia, but it can also progress to changes in cognitive function and difficulty in motor function, especially slow gait and poor balance [19,34]. |

| Lewy body disease | About 5% of individuals with dementia show evidence of only Lewy bodies (DLB), while many pathological autopsy cases reported Lewy bodies combined with Alzheimer’s disease changes. Lewy bodies are alpha-synuclein proteins that create abnormal aggregations (also called clumps) in neurons. Usually, this protein develops in a part of the brain cortex. Lewy bodies are also found in Parkinson’s disease. The symptoms of this kind of dementia are similar to Alzheimer’s, but patients have a higher likelihood for early symptoms of sleep disturbance, visual hallucinations, and visuospatial impairment. These symptoms may occur in the absence of memory impairment. However, memory loss does occur in the progression of the disease [19]. Furthermore, other signs may occur including: uncoordinated movements, slow moving, tremors, and muscular rigidity (parkinsonism). |

| Fronto-temporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) | The age incidence of this kind of dementia occurs between 40 to 65 years; 60% of people diagnosed with FTLD are aged 45 to 60 years. FTLD symptoms show marked changes in personality and behaviors and difficulty with producing and comprehending language. Memory is typically spared in the early stages of this disease, but is impacted as part of disease progression. This kind of dementia has features of primary progressive aphasia, Pick’s disease, progressive supranuclear palsy, and corticobasal degeneration. There are well-defined changes that have been recognized in this kind of dementia; changes of nerve cells in the frontal lobe and temporal lobes on the sides of the brain are especially affected. These regions are markedly atrophied, while the upper layers of the cortex become soft, spongy, and have abnormal protein inclusions called tau protein and/or transactive response DNA-binding protein (TDP-43) [19]. |

| Assessment Tool | Definition |

|---|---|

| Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) | Used to quickly assess cognitive function in clinical settings. It tests orientation, attention, calculation, recall, and language, with the cut-off score dependent on the level of education. The score ranges from 0 to 30 with lower score indicating high degree of cognitive dysfunction (19–24 mild, 10–18 moderate, and 0–9 severe) [35]. |

| Neuropsychiatry Inventory (NPI) | This scale is designed to assess behavioral problems and symptoms as well as detecting behavioral changes over time. The score can range from 10 (the least frequent) to 144 (the most frequent) [22] |

| Montreal Cognitive Assessment | A rapid screen instrument for mild cognitive dysfunction, this scale assesses complex attention, concentration, executive function, memory, language, visuoconstructional skills, orientation, calculation, and conceptual thinking. A score >26 means normal, 18–25 is mild cognitive impairment, 10–17 moderate impairment, and <10 is severe cognitive impairment [23]. |

| Alzheimer’s disease Assessment Scale (ADAS) | Designed to evaluate the severity of cognitive dysfunction via 11 items and non-cognitive behaviors via 10 items over time. The score ranges from 0 to 70 for the cognition section and from 0 to 50 for the behavioral section. A higher score indicates a greater level of impairment [24]. |

| Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease | This scale designed to assess behavioral symptoms and measure outcomes in treatment studies. The score rages from 0 to 78. The higher the score, the more significant behaviors were noted in the interview [23]. |

| Clinical Dementia Rating Scale | Used to assess the cognitive and functional impairment in six domains: memory, orientation, problem solving, judgment, community activities, and hobbies, and personal care. The score of each domain forms a composite score ranged from 0 (no impairment) to 3 (severe impairment) [24,25]. |

| Severe Impairment Battery | Used for detecting cognitive function in severe dementia. The score range is from 0 (totally impaired) to 100 (no impairment) [26]. |

| Saint Louis University Mental Status Examination | This scale is used to assess cognitive function quickly in a clinical setting. It is more sensitive than MMSE in detecting mild cognitive impairment. The score ranges from 0 to 30. The lowest score is the highest degree of cognitive impairment. Scores of 27–30 are normal, scores of 21–26 are mild, and scores of 0–25 suggest signs of dementia [27] |

| Functional Assessment Staging Test | Designed to assess the functional impairment of dementia. Its specific purpose is to determine the degree of functional impairment as cognitive function decline. The score ranges from 1 (no impairment) to 7 (severe impairment), with 3 and above indicative of early dementia [28]. |

| Clinician’s Interview-Based Impression of Change | A global assessment measuring clinically significant changes in dementia condition over the time. The score range is from 0 to 7, where 1 is improvement, 4 is no changes, and 7 is deterioration [29]. |

References

- Vieta, E.; Garriga, M.; Cardete, L.; Bernardo, M.; Lombraña, M.; Blanch, J.; Catalán, R.; Vázquez, M.; Soler, V.; Ortuño, N.; et al. Protocol for the management of psychiatric patients with psychomotor agitation. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cummings, J.; Mintzer, J.; Brodaty, H.; Sano, M.; Banerjee, S.; Devanand, D.P.; Gauthier, S.; Howard, R.; Lanctôt, K.; Lyketsos, C.G.; et al. Agitation in cognitive disorders: International Psychogeriatric Association provisional consensus clinical and research definition. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2015, 27, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Landreville, P.; Leblanc, V. Older adult’s acceptability ratings of treatments for verbal agitation in persons with dementia. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Other Demen. 2010, 25, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetzels, R.B.; Zuidema, S.U.; Jonghe, J.F.D.; Verhey, F.R.; Koopmans, R.T. Course of neuropsychiatric symptoms in residents with dementia in nursing homes over 2-year period. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2010, 18, 1054–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viscogliosi, G.; Chiriac, I.M.; Ettorre, E. Efficacy and Safety of Citalopram Compared to Atypical Antipsychotics on Agitation in Nursing Home Residents with Alzheimer Dementia. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2017, 18, 799–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porsteinsson, A.P.; Drye, L.T.; Pollock, B.G.; Devanand, D.P.; Frangakis, C.; Ismail, Z.; Marano, C.; Meinert, C.L.; Mintzer, J.E.; Munro, C.A.; et al. Effect of citalopram on agitation in Alzheimer disease: The CitAD randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014, 311, 682–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pollock, B.G.; Mulsant, B.H.; Rosen, J.; Mazumdar, S.; Blakesley, R.E.; Houck, P.R.; Huber, K.A. A double-blind comparison of citalopram and risperidone for the treatment of behavioral and psychotic symptoms associated with dementia. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2007, 15, 942–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoar, N.S.; Fariba, K.A.; Padhy, R.K. Citalopram. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482222/ (accessed on 14 May 2022).

- Leonpacher, A.; Peters, M.; Drye, L.; Makino, K.; Newell, J.; Devanand, D.; Frangakis, C.; Munro, C.; Mintzer, J.; Pollock, B.; et al. Effects of Citalopram on Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Alzheimer’s Dementia: Evidence from the CitAD Study. Am. J. Psychiatry 2016, 173, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pollock, B.G.; Mulsant, B.H.; Sweet, R.; Burgio, L.D.; Kirshner, M.A.; Shuster, K.; Rosen, J. An open pilot study of citalopram for behavioral disturbances of dementia. Plasma levels and real-time observations. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 1997, 5, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, B.G.; Mulsant, B.H.; Rosen, J.; Sweet, R.A.; Mazumdar, S.; Bharucha, A.; Marin, R.; Jacob, N.J.; Huber, K.A.; Kastango, K.B.; et al. Comparison of citalopram, perphenazine, and placebo for the acute treatment of psychosis and behavioral disturbances in hospitalized, demented patients. Am. J. Psychiatry 2002, 159, 460–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisberg, B.; Auer, S.; Monteiro, I. Behavioural Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease (BE_HAVE-AD) Rating Scale. Int. Psychogeriatr. 1997, 8, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, Z.; Emeremni, C.A.; Houck, P.R.; Mazumdar, S.; Rosen, J.; Rajji, T.K.; Pollock, B.G.; Mulsant, B.H. A comparison of the E-BEHAVE-AD, NBRS, and NPI in quantifying clinical improvement in the treatment of agitation and psychosis associated with dementia. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2013, 21, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- GBD 2019 Dementia Forecasting Collaborators. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: An analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health 2022, 7, e105–e125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmbom, L.V.; Torisson, L.G.; Strandberg, E.L.; Londos, E. Living with dementia with Lewy bodies: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e024983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, S.; Patel, N.; Baio, G.; Kelly, L.; Lewis-Holmes, E.; Omar, R.Z.; Katona, C.; Cooper, C.; Livingston, G. Monetary costs of agitation in older adults with Alzheimer’s disease in the UK: Prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e007382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaugler, J.; James, B.; Johnson, T.; Reimer, J.; Weuve, J. Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Special Report. More Than Normal Aging: Understanding Mild Cognitive Impairment. Alzheimer’s Assoc. 2022, 18. Available online: https://www.alz.org (accessed on 14 May 2022).

- Reuck, J.D.; Maurage, C.A.; Deramecourt, V.; Pasquier, F.; Cordonnier, C.; Leys, D.; Bordet, R. Aging and cerebrovascular lesions in pure and in mixed neurodegenerative and vascular dementia brains: A neuropathological study. Folia Neuropathol. 2018, 56, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barker, W.W.; Luis, C.A.; Kashuba, A.; Luis, M.; Harwood, D.G.; Loewenstein, D. Relative frequencies of Alzheimer’s disease, Lewy body, vascular and frontotemporal dementia, and hippocampal sclerosis in the State of Florida Brain Bank. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2002, 16, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, D.B.; Jette, N.; Fiest, K.M.; Roberts, J.I.; Pearson, D.; Smith, E. The prevalence and incidence of frontotemporal dementia: A systematic review. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 2016, 43, S96–S109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. Mini-mental state: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J. NPI TEST. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire. Background and Administration. 2000. Available online: www.alz.org/careplanning/ (accessed on 14 May 2022).

- Nasreddine, Z. Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). Version 8.3. 2017. Available online: www.mocatest.org (accessed on 14 May 2022).

- Doraiswamy, P.; Bieber, F.; Kaiser, L.; Krishnan, K.; Reuning-Scherer, J.; Gulanski, B. The Alzheimer’s disease assessment scale. Patterns and predictors of baseline cognitive performance in multicentre Alzheimer’s disease trials. Neurology 1997, 48, 1511–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoo, S.A.; Chen, T.Y.; Ang, Y.H.; Yap, P. The impact of neuropsychiatric symptoms on caregiver distress and quality of life in persons with dementia in an Asian tertiary hospital memory clinic. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2013, 25, 1991–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, C.; Lim, W.; Chan, M.; Ho, X.; Anthony, P.; Han, H.; Chong, M. Severe Impairment Rating Scale: A Useful and Brief Cognitive Assessment Tool for Advanced Dementia for Nursing Home Residents. Am. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Other Dement. 2016, 31, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tariq, H.; Tumosa, N.; Chibnall, J.T.; Perry, H.M.; Morley, J.E. The Saint Louis University Mental Status (SLUMS) Examination for detecting mild cognitive impairment and dementia is more sensitive than the Mini Mental Status Examination (MMSE)—A pilot study. Am. J. Geriatr. Psych. 2006, 14, 900–910. Available online: www.slu.edu/medicine/internal-medicine/geriatric-medicine/aging-successfully/pdfs/slums_form.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reisberg, B. Functional Assessment Staging Tests (FAST). Psychopharmacol. Bull. 1988, 24, 653–659. Available online: https://dementiaresearch.org.au (accessed on 14 May 2022). [PubMed]

- Knopman, D.S.; Knapp, M.J.; Gracon, S.I.; Davis, C.S. The Clinician Interview-Based Impression (CIBI): A clinician’s global change rating scale in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 1994, 44, 2315–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kongpakwattana, K.; Sawangjit, R.; Tawankanjanachot, I.; Bell, J.S.; Hilmer, S.N.; Chaiyakunapruk, N. Pharmacological treatments for alleviating agitation in dementia: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018, 84, 1445–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Verhey, F.R.; Verkaaik, M.; Lousberg, R. Olanzapine-Haloperidol in Dementia Study group. Olanzapine versus haloperidol in the treatment of agitation in elderly patients with dementia: Results of a randomized controlled double-blind trial. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2006, 21, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitz, D.P.; Adunuri, N.; Gill, S.S.; Gruneir, A.; Herrmann, N.; Rochon, P. Antidepressants for agitation and psychosis in dementia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011, 16, 1465–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teri, L.; Logsdon, R.G.; Peskind, E.; Raskind, M.; Weiner, M.F.; Tractenberg, R.E.; Foster, N.L.; Schneider, L.S.; Sano, M.; Whitehouse, P.; et al. Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study. Treatment of agitation in AD: A randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Neurology 2000, 55, 1271–1278, Erratum in Neurology 2001, 56, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.M. Dementia Severity Rating Scale (DSRS). Available online: www.alz.org/media/documents/dementia-severity-rating-scale.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2022).

- Perneczky, R.; Wagenpfeil, S.; Komossa, K.; Grimmer, T.; Diehl, J.; Kurz, A. Mapping scores onto stages: Mini-mental State Examination and Clinical Dementia Rating. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatr. 2006, 14, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Citation, Year | Number of Participants | Duration | Active Ingredient | Lost Follow-Up | Difference between Groups | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viscogliosi et al., 2017 [5] | 75 (citalopram n = 25), (olanzapine n = 25), (quetiapine n = 25) | 26 weeks | Citalopram, olanzapine, quetiapine | Short duration of follow-up (no details) | Efficacy against agitation: citalopram vs. quetiapine (OR 1 95% CI = 0.92, 1.7 at p = 0.935), citalopram vs. olanzapine (OR = 0.98, 95% CI = 0.86, 1.2 at p = 0.849). Hospitalization: quetiapine (OR = 0.92, 95% CI = 0.88, 0.95 at p = 0.016), olanzapine (OR = 0.78, 95% CI= 0.64, 0.92 at p = 0.004). Occurrence of falls: olanzapine (OR =0.81, 95% CI = 0.68, 0.97 at p = 0.012). Incidence of orthostatic hypotension: quetiapine (OR = 0.8, 95% CI = 0.66, 0.95 at p = 0.032), olanzapine (OR = 0.75, 95% CI = 0.69, 0.91 at p = 0.02). | Citalopram has similar efficacy to quetiapine and olanzapine. Citalopram showed less all-case hospitalizations than both quetiapine and olanzapine. Citalopram also showed the lowest occurrence of falls compared to olanzapine, but no difference in lowering falls between citalopram and quetiapine. Citalopram showed lower incidence of orthostatic hypotension than quetiapine and olanzapine. |

| Pollock et al., 2007 [7] | 103 (citalopram n = 53), (risperidone n = 50) | 12 weeks | Citalopram, risperidone | N = 31 lost follow-ups in the risperidone group. N = 38 lost follow-ups in the citalopram group | NBRS agitation score citalopram vs. risperidone (OR 0.11 95% CI = −0.28, 0.50 at p = 0.57); NBRS psychosis score (OR = 0.06, 95% CI = −0.35, 0.46 at p = 0.79); UKU total score (OR = 0.52, 95% CI 0.12, 0.91 at p = 0.01); UKU psychotic subscale score (OR = 0.55, 95% CI 0.15, 0.94 at p = 0.007); UKU neurological subscale score (OR = 0.22, 95% CI = −0.17, 0.61 at p = 0.27). | The result of this trial showed the agitation and psychosis symptoms decreased in both treatment groups. Additionally, the trial stated that there was a significant side effects with risperidone but not with citalopram. |

| Marano et al., 2014 [6] | 186 (citalopram n = 94), (psychotherapy n = 92). | 9 weeks | Citalopram vs. placebo | After the 9-week visit, n = 8 lost follow-ups in the citalopram group and n = 9 lost follow-ups in the psychotherapy group. | The NBRS-A scale after 9 weeks shown OR −0.93 95% CI = −1.80, −0.06 at p = 0.04. The results of mADCS-CGIC showed that 40% in the citalopram group had marked improvements, with OR 2.13 95% CI = 1.23, 3.69 at p = 0.01. QT interval prolongation was seen in the citalopram group and not in the placebo group (18.1 ms; 95% CI = 6.1, 30.1 at p = 0.004). | The results of this trial showed significant improvement in the citalopram group compared to the placebo group. Moreover, CMAI and NPI scales revealed significant improvements for citalopram group participants. However, QT intervals prolongation were seen in the citalopram group |

| AMSTAR 2 TOOL | Seitz et al., 2011 [32] | Chaiyakunapruk et al., 2018 [30] |

|---|---|---|

| Includes PICO components and research questions | YES | YES |

| Comprehensive details about methodology before conducting the review | YES | YES |

| Description of the inclusion criteria | YES | YES |

| Comprehensive details about searching strategies | YES | YES |

| Performs study selection in duplicate | YES | NO |

| Data extraction in duplicate | YES | YES |

| Describes exclusion criteria | NO | YES |

| Describes inclusion studies in detail | YES | YES |

| Satisfactory technique for assessing risk of bias | YES | YES |

| Report the source of funding | NO | NO |

| Uses an appropriate statistical technique for meta-analysis combination of RCT results | YES | YES |

| Assesses the potential impact of RoB on each individual RCT study | NO | YES |

| Accounts RoB in each individual study when discussing the result | YES | YES |

| Satisfactory explanation for RCT results in the review | YES | YES |

| Performs an adequate investigation of potential risk of bias in quantitative studies | YES | YES |

| Reported any potential conflict of interest and funding | YES | YES |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qasim, H.S.; Simpson, M.D. A Narrative Review of Studies Comparing Efficacy and Safety of Citalopram with Atypical Antipsychotics for Agitation in Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia (BPSD). Pharmacy 2022, 10, 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy10030061

Qasim HS, Simpson MD. A Narrative Review of Studies Comparing Efficacy and Safety of Citalopram with Atypical Antipsychotics for Agitation in Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia (BPSD). Pharmacy. 2022; 10(3):61. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy10030061

Chicago/Turabian StyleQasim, Haider Saddam, and Maree Donna Simpson. 2022. "A Narrative Review of Studies Comparing Efficacy and Safety of Citalopram with Atypical Antipsychotics for Agitation in Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia (BPSD)" Pharmacy 10, no. 3: 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy10030061

APA StyleQasim, H. S., & Simpson, M. D. (2022). A Narrative Review of Studies Comparing Efficacy and Safety of Citalopram with Atypical Antipsychotics for Agitation in Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia (BPSD). Pharmacy, 10(3), 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy10030061